-

Figure 1.

Classification of A-to-I recoding sites and their evolutionary dynamics. (a) Recoding sites can be classified as A-preferring, G-preferring, and A/I-preferring based on the fitness effects of the edited and unedited variants. Editing at A-preferring sites is neutral or slightly deleterious, becoming fixed in the genome primarily through genetic drift. A/I-preferring sites are positively selected for their ability to enhance protein diversity and flexibility. In contrast, G-preferring sites may be fixed through positive selection due to their compensatory or transitional roles, or through genetic drift if they are harm-permitted by editing. These sites can also be categorized into restorative or diversifying editing based on the amino acid changes relative to ancestral states. Restorative editing includes compensatory editing, which corrects pre-existing harmful genomic G-to-A mutations, and harm-permitting editing, which corrects genomic G-to-A mutations that it itself promotes. Both G-preferring and A/I-preferring compensatory editing are adaptive, while only A/I-preferring harm-permitting editing can be adaptive. (b) The expected A-to-G substitution rate at the three types of recoding sites is shown relative to synonymous editing sites (neutral rate) and nonsynonymous uneditable sites.

-

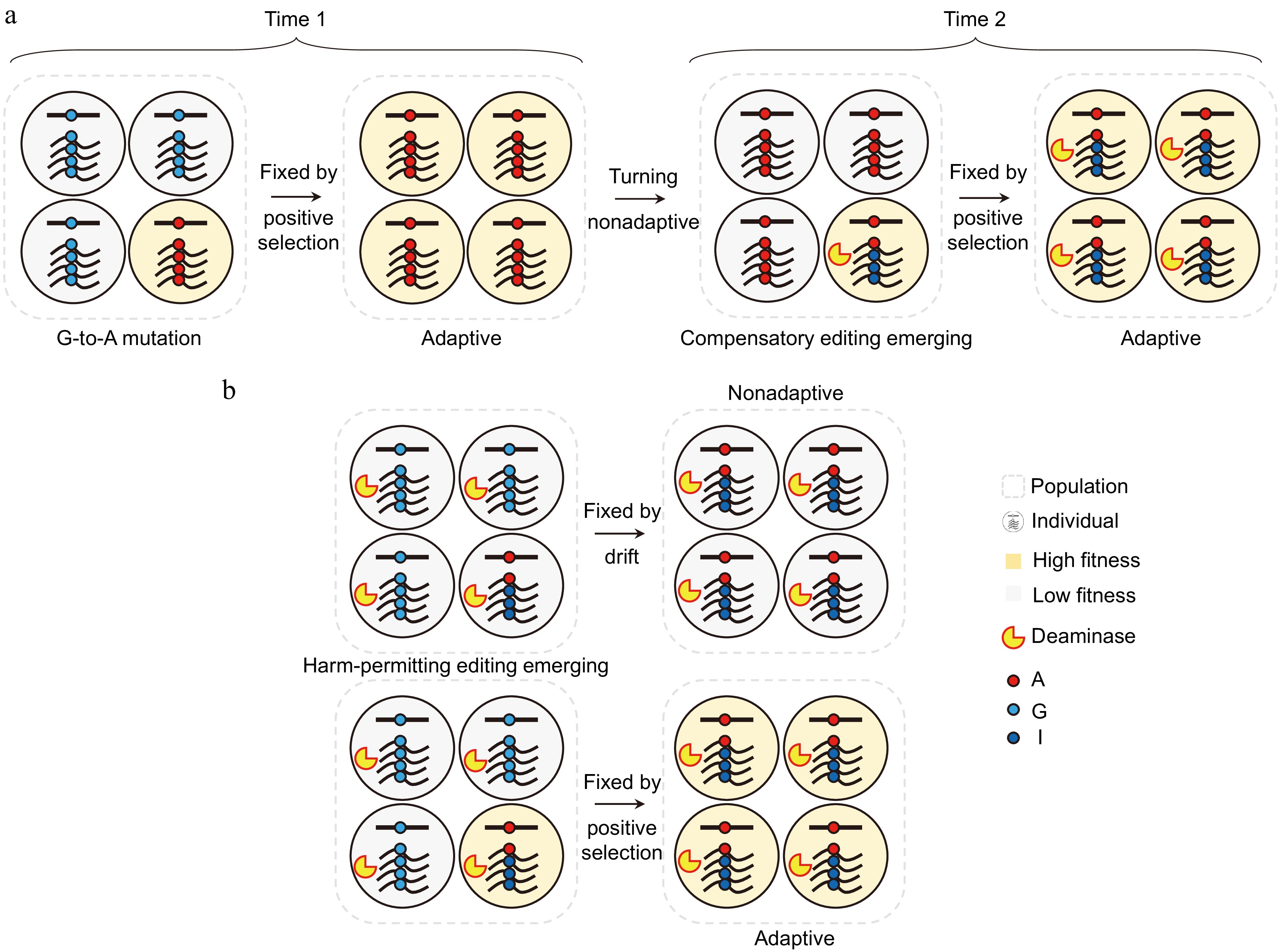

Figure 2.

The potential evolutionary processes of two types of restorative editing: compensatory editing and harm-permitting editing. (a) When G-to-A mutations that were once advantageous at Time 1 become harmful at Time 2, compensatory A-to-I editing can be established through positive selection due to its role in compensating for these mutations or enhancing protein diversity and flexibility. (b) Pre-existing editing activity can relax functional constraints at the genomic level, allowing G-to-A mutations to create new edited A sites, resulting in harm-permitting editing. This process underscores the intricate relationship between A-to-I editing and G-to-A mutations, as the formation of edited A sites relies on A-to-I editing. Consequently, no intermediate individuals can possess the corresponding editable A sites without the associated editing events. If harm-permitting editing only serves a restorative function, it should be nonadaptive and fixed by genetic drift, as it does not confer a fitness advantage over the original genomic G. However, it can be adaptive and fixed by positive selection when the protein diversity and flexibility provided by harm-permitting editing confer a competitive advantage.

-

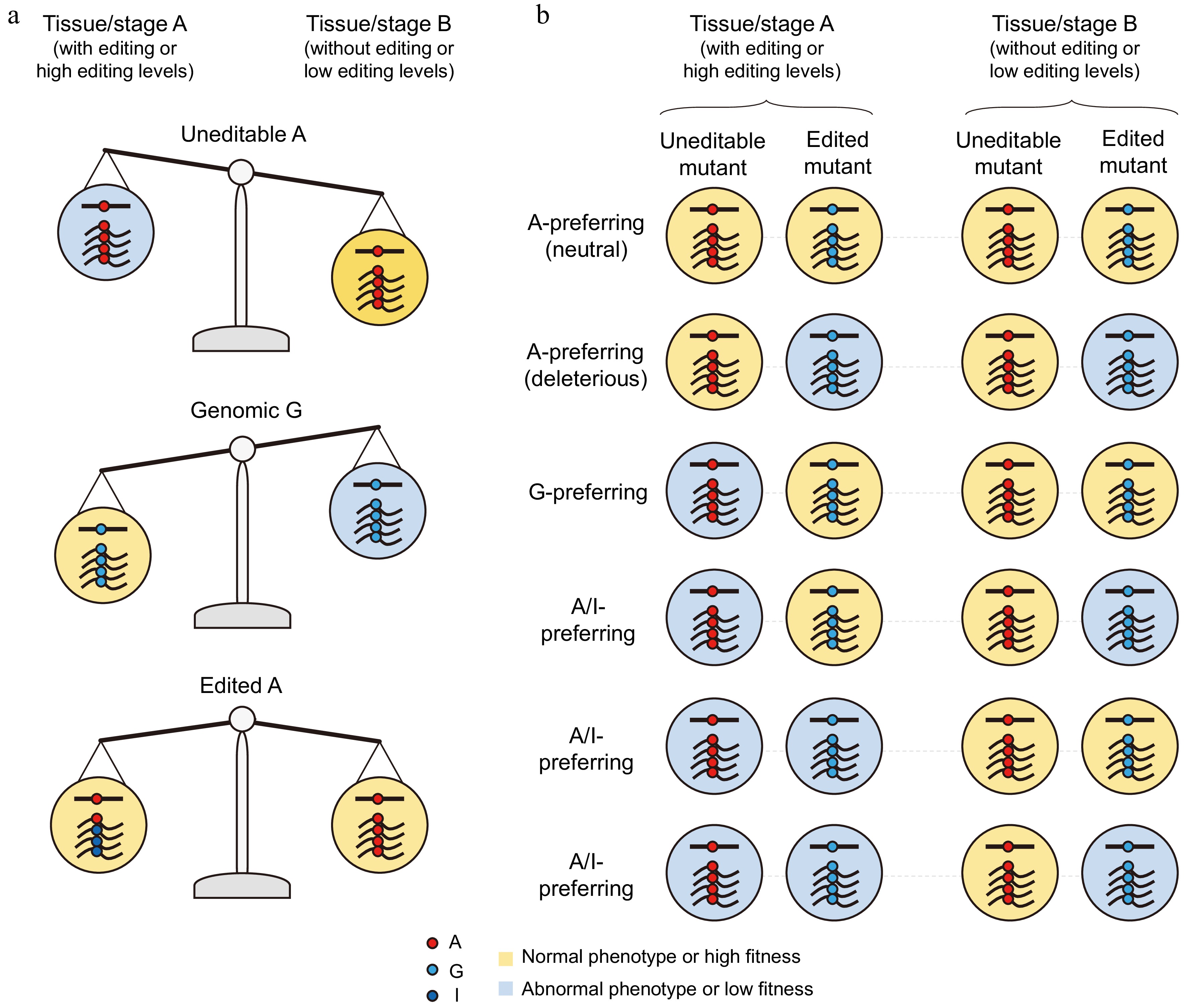

Figure 3.

The advantages of A-to-I RNA editing in navigating trade-offs arising from antagonistic pleiotropy and the anticipated phenotypes or fitness of uneditable and edited mutants. (a) The A variant is detrimental in tissue/stage A but beneficial in tissue/stage B, and/or the G variant is beneficial in tissue/stage A but detrimental in tissue/stage B. Tissue/stage A-specific RNA editing can alleviate the trade-offs resulting from the antagonistic pleiotropy of these two variants across both tissues/stages. (b) The anticipated developmental or physiological phenotypes and fitness of uneditable mutants (expressing only the A variant) and edited mutants (expressing only the G variant) for each type of recoding sites, as determined through genetic studies.

-

Taxon Target protein Recoding site1

(editing level)Uneditable mutant Edited mutant Ref. Fungi F. graminearum PSC58 *323W (53%) Defective in ascogenous hypha formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC69 *318W (16%) Defective in ascogenous hypha formation Sensitive to stress during vegetative growth [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC27 *494W (87%) Defective in ascus formation, and

ascus and ascospore maturationNo obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC10 *64W (96%) Defective in ascus formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC20 *263W (91%) Defective in ascus formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC24 *172W (80%) Defective in ascus formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC07 *87W (95%) Defective in ascus formation and discharge No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum Puk1/PSC03 *576W (86%);

*577W (98%)Defective in ascospore formation

and dischargeNo obvious defects [5,29] Fungi F. graminearum Amd1/PSC04 *221W (97%) Defective in ascus maturation No obvious defects [29,45] Fungi F. graminearum PSC37 *816W (85%) Defective in ascospore formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC17 *34W (89%) Defective in ascospore formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC30 *63W (75%) Defective in ascospore formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC52 *693W (73%) Defective in ascospore formation No obvious defects [29] Fungi F. graminearum PSC64 *419W (63%) Defective in ascus formation, and

ascus and ascospore maturationSensitive to stress during vegetative growth [29] Fungi F. graminearum FgAma1/PSC33 *387W (67%) Defective in ascospore morphogenesis No obvious defects [29,44] Fungi F. graminearum Cme5 R986G (71%) Defective in ascus and ascospore formation No obvious defects [42] Fungi F. graminearum Cme11 T304A (50%) Defective in ascospore formation Defective in ascospore formation [42] Fungi F. graminearum Tub1 N347D (41%) No obvious defects Defective in ascospore formation [84] Fungi F. verticillioides SKC1 *71W (84%) Defective in spore killing — [46] Fungi N. crassa Stk-21 *508W (94%) Defective in ascospore maturation

and germination— [8] Fungi N. crassa NCU10184 *220W (88%) Defective in ascospore formation — [8] Bacteria E. coli HokB Y29C (28%−93%) Mild toxicity, similar to wild type Elevated toxicity [9] Bacteria X. oryzae FliC S128P (0−25%) Reduced tolerance to oxidative stress Increased motility and improved tolerance to oxidative stress [48] Bacteria X. oryzae XfeA T408A (21%−78%) Grew at a slower rate than wild type under iron deficiency Enhanced ion uptake activity and grew more rapidly under iron deficiency [49] Bacteria K. pneumoniae BadR Y99C (4%−10%) — Reduced autoinducer-2 activity, decreased cell growth during the stationary phase, and decreased virulence [11] 1 The asterisk (*) marks the premature-stop codon UAG. Table 1.

Functionally important A-to-I recoding sites identified in fungi and bacteria through genetic studies.

-

Taxon Target protein Recoding site

(editing level)Uneditable mutant Edited mutant Ref. Mice GluA2/ GluRB Q586R (~99%) Exhibiting severe dendritic deficits and early death No significant deficiencies in brain development, health, appearance, and lifespan, yet exhibiting increased hippocampal spine density [54,56,57,85] Mice FLNA Q2341R (87.8% + 3.7%) Normal life expectancy with no apparent abnormalities, yet increased vascular contraction leads to elevated blood pressure and cardiac remodeling Cell lines exhibiting increased stiffness and adhesion, yet impaired migration [62,63] Mice 5-HT2CR I156V/M (4%−100%); N158S/D/G (10%−84%); I160V (22%−96%) Developed normally Severe weight loss, increased sympathetic activity, and higher energy expenditure [60,86] Mice GluK2/ GluR6 Q621R (~76%) Normal behavior but increased susceptibility to seizures from kainic acid − [59] Mice CaV1.3 I/M (45%); Y/C (29%) Enhanced learning ability and long-term memory in mice due to increased Ca2+ influx in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons − [61] Mice CAPS1 E1250G (15%−70%) − Enhanced short-term depression at inhibitory synapses and lean phenotype from increased energy expenditure due to physical hyperactivity [64,87] Mice GluK1/GluR5 Q636R (~50%) − Normal development and behavior [65] Drosophila Adar S458G (~50%) Abnormal behavior Abnormal behavior [67] Drosophila GluClα I27V (80%−94%) Impaired olfactory responses and pheromone-dependent interactions, decreased female receptivity, yet intact motor activity and extended lifespan − [69] Table 2.

Functions of genetically characterized A-to-I recoding sites in animals.

-

Taxon Target protein Recoding site Impact on protein function Ref. Mice GluA2/GluRB Q586R Reduced Ca2+ permeability and channel conductance [71] Mice GluK1/GluR5 Q636R Reduced Ca2+ permeability and channel conductance [65] Mice GluK2/GluR6 Q621R Reduced Ca2+ permeability and channel conductance [72] Mice 5-HT2CR I156V+N158S+I160V Decreased interaction with G proteins and agonist potency [88,89] Mice CaV1.3 I/M+Q/R+Y/C Reduced CaM binding and calcium-dependent inactivation (CDI) [90,91] Rat GluA2/GluRB R764G Enhanced recovery rate from desensitization [92] Rat GluA3 R769G Enhanced recovery rate from desensitization [92] Rat GluA4 R765G Enhanced recovery rate from desensitization [92] Human GABAA (α3) I314M Probably destabilized the stability of the open ion state [80] Human Kv1.1 I400V Destabilized the fast inactivated state and reduced whole-cell

current by decreasing surface membrane trafficking[73,93] Human NEIL1 K242R Reduced activity in removing oxidized pyrimidines [94,95] Human SLC22A3 N72D Reduced direct binding to ACTN4 [96] Human COPA I164V Reduced protein stability and altered conformation [97] Human GLI1 R701G Reduced transcriptional activity and less susceptible to

inhibition by the negative regulator[98] Human AZIN1 S367G Increased protein stability and caused AZIN1 translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus [99] Human RhoQ N136S Enhanced RhoQ activity [100] Human IGFBP7 K95R Increased IGFBP7 protein stability [101] Octopus synaptotagmin-1 I248V Decreased the binding affinity for Ca2+ and altered the protein's conformation [82] Octopus kinesin-1 K282R Reduced transport velocity and run length [82] Octopus Kv1.1 I321V Destabilized the channel's open state [75] Squid Kv1.1 R87G Destabilized the tetramer [76] Squid Na+/K+ ATPase (α1) I877V Destabilized the Na+-bound state [77] Squid Kv2 Y576C; I597V Affected the rate of channel closure and slow inactivation [81] Squid kinesin S75G + Y77C + N117D + K368R + K483R; K67R + Y77C + N117D + K368R + K479R + K483G + E515G Enhanced kinesin motility in cold conditions [83] Drosophila Eag K467R + Y548C + N567D + K699R Decreased activation kinetics and minimal inactivation [79] Drosophila Shaker (Kv1.1) T489A Reduced the inactivation rate of the channel [78] Drosophila Shab (Kv2) I681V Probably destabilized the open state [74] Drosophila Adar S458G Decreased catalytic activity and altered Adar nuclear localization [67] Table 3.

Impact of A-to-I recoding on protein function in animals.

Figures

(3)

Tables

(3)