-

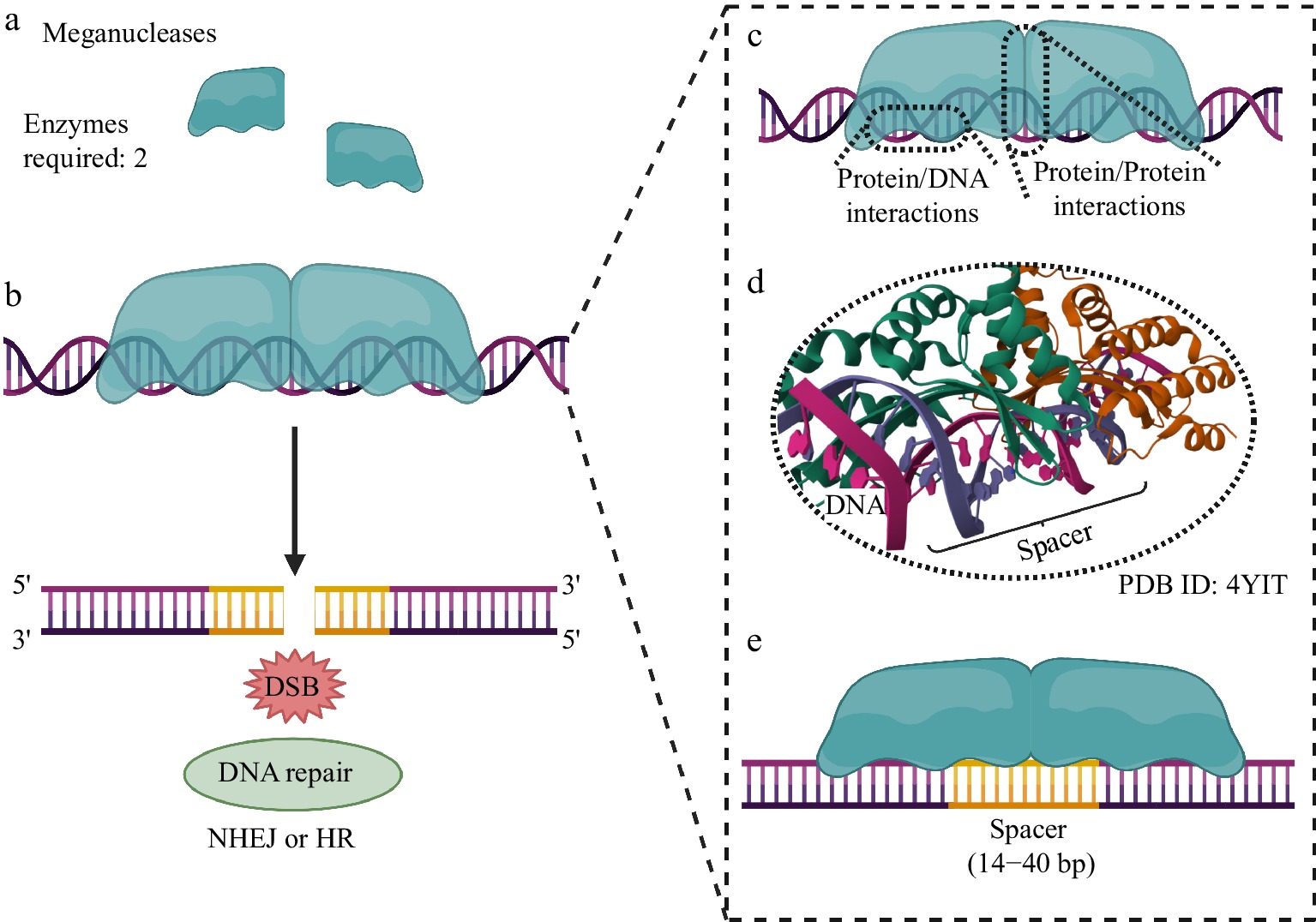

Figure 1.

Genome editing using MNs. (a) Two MNs are required to generate the DSB at the target genomic site. (b) After DNA cleavage, repair systems based on NHEJ or HR are activated, allowing subsequent modification of the genomic locus for the biotechnological purpose of the experiment. (c) Protein/DNA interactions are established between the MN (through its specific DNA recognition/binding domain and endonuclease domain, for specific DNA cleavage) and the genomic locus to be edited. (d) The endonuclease domain must interact with the genomic spacer region to allow DNA cleavage. (e) Both MNs recognize a long cleavage spacer region, typically 14 to 40 base pairs (bp) long. Created with BioRender.com.

-

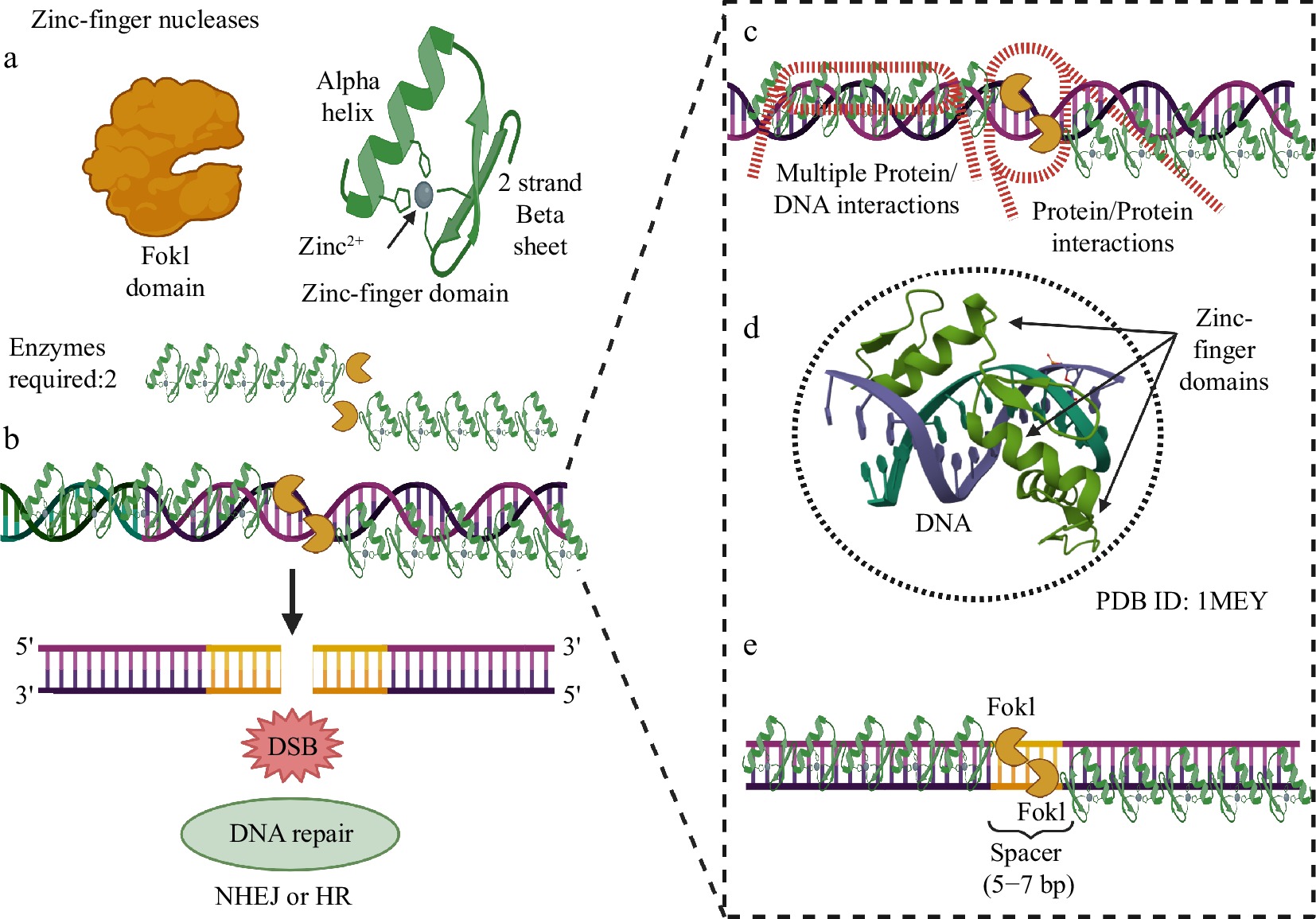

Figure 2.

Main aspects of genome editing with ZFNs. (a) Functional domains of ZFNs: the FokI cleavage domain and the DNA-specific recognition and binding domain; Zinc-finger domain (containing an alpha-helix and a beta-sheet with two antiparallel beta-strands, in addition to a Zn2+ cation. (b) Two ZFNs are required for the cleavage of the genomic locus, with simultaneous double activation of the FokI domains, which need to interact after touching each other. The provoked DSB activates DNA repair systems (NHEJ or HR). (c) Multiple DNA/protein interactions and between FokI domains allow two compatible ZFNs to catalyze two phosphodiester bond cleavage reactions within the spacer region. (d) Tandem Zinc-finger domains are essential for the specificity of recognition and binding to DNA at the genomic editing locus. (e) The spacer region capable of presenting an editable site for the FokI domains is short, between 5 and 7 bp. Created with BioRender.com.

-

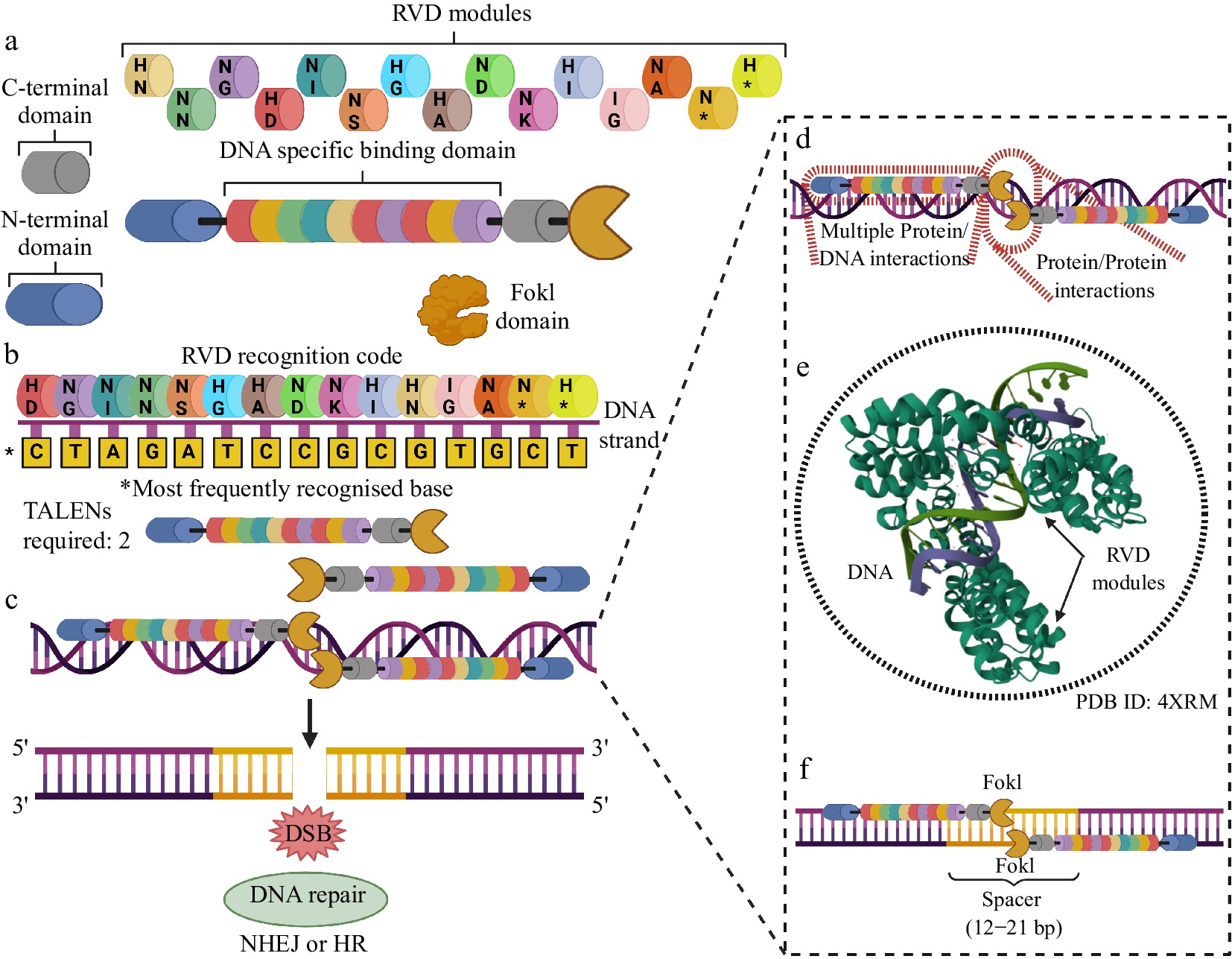

Figure 3.

Most important aspects of using TALENS for genome editing. (a) TALENS have components varying in length and structural complexity. Each TALEN has two stabilization domains (N- and C-terminal), a FokI cleavage domain, and an extensive DNA-specific recognition and binding domain, made up of RVD modules with pairs of amino acid residues organized in tandem. Each combination of residues in an RVD pair can recognize and specifically bind to a base along a DNA strand. (b) The RVD DNA recognition code indicates which pair of amino acid residues are most likely to recognize and bind to a given DNA base. The same pair can bind to more than one base but with different probabilities. The figure shows the pairs with their respective most frequent bases. (c) Two TALENs with opposite orientations are needed to produce a DSB. (d) TALEN/DNA interactions are extensive, which allows for a higher level of editing precision of this technology when compared to MNs and ZFNs. (e) The RVD modules present sequential binding cooperation to the genomic editing locus, which increases the specificity of DNA recognition. (f) A spacer of 12 to 21 bp is required for the mutual activation of the FokI domains and the precise cleavage of the DNA. Created with BioRender.com.

-

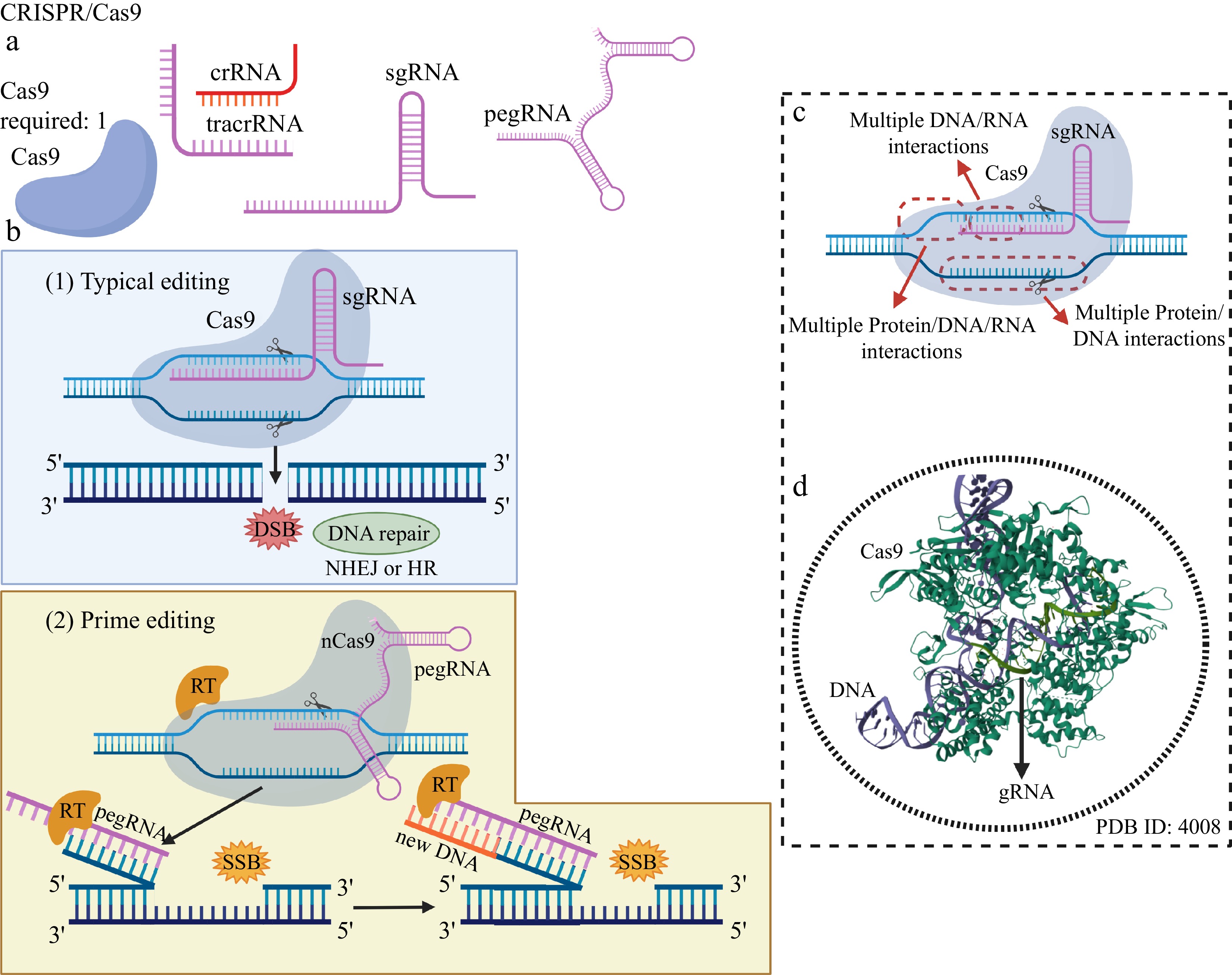

Figure 4.

Genome editing using the classic CRISPR/Cas9 system and Prime editing. (a) Editing elements typically present in the CRISPR/Cas9 system: the DNA cleavage enzyme Cas9, the recognition RNAs of the genomic editing locus: crRNA, tracrRNA, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) – in the case of Prime editing. (b) In typical editing, a sgRNA internal to Cas9, containing a sequence of bases that are complementary and homologous to the bases of a DNA strand at the genomic editing locus, is used to access the editing region, which is doubly cleaved by a single Cas9 with both internal endonuclease domains, resulting in a DSB and activation of DNA repair systems. In the Prime editing system, a modified Cas9 (nCas9), linked to a reverse transcriptase (RT) and carrying only one active DNA cleavage domain, is guided by a peg RNA to the genomic editing locus. After pairing the bases of an extensive region of the pegRNA with one of the DNA strands of the editing locus, nCas9 catalyzes the production of a single-strand break (SSB) by a single nick in the DNA. RT reads the editing sequence present in a region of the pegRNA and synthesizes a DNA strand containing the editing, which is attached to the end of the nicked DNA. (c) Multiple and extensive interactions between Cas9, sgRNA and these with both DNA strands at the genomic editing locus confer a high level of specificity, precision and editing accuracy. (d) The main cause of the high specificity of DNA editing provided by the CRISPR system is the multiple interactions between nucleic acids (sgRNA and DNA), governed by complementarity and homology, which are not observed in MNs, ZFNs, and TALENs. Created with BioRender.com.

-

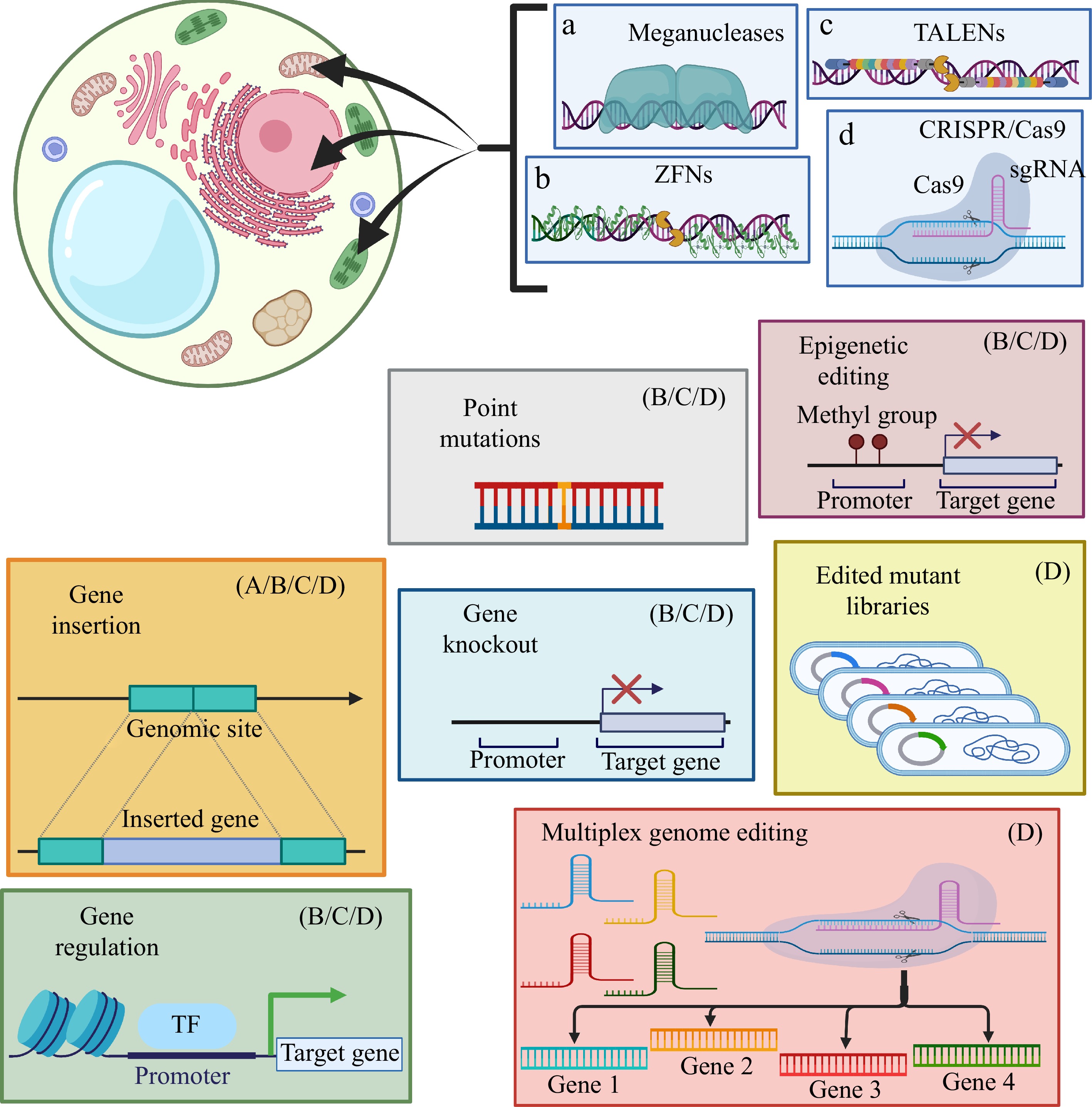

Figure 5.

Some recurring biotechnological approaches to genome editing in plants. Diagram shows the different methodological applications of the main plant genome editing tools, as well as their limitations of use. Created with BioRender.com.

-

Parameter ZFNs TALENS CRISPR/Cas9 system Design complexity ++ ++ + Versatility in editing + ++ +++ Simultaneous editing in multiple sites + + +++ Large-scale library delivery + + +++ Specificity + ++ ++++ Efficiency ++ ++ +++ Cost + +++ + Homologous recombination frequency + + + Mutation frequency after non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) + + ++ Use as epigenetic modifiers ++ +++ ++++ Use as gene-knockout in model organisms − − +++ − absent, + low, ++ moderate, +++ high, ++++ very high. Modified from Khan[11]. Table 1.

Technical, biotechnological aspects, and possibilities of using ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9 system for the genomic manipulation of plants.

-

Standard Cas nucleases Class Type Signature

Cas proteinMain features Ref. 2 II Cas9 Most popular Cas for editing the

plant genome recognizes PAM NGG

Requires a crRNA-tracrRNA duplex

or a single-guide RNA for target recognition[48,49] V Cas12a More specific than wild-type SpCas9 Requires a crRNA for target recognition, but the crRNA is

short (~42 nt) Targets T-rich regions generates a DSB distal from the PAM site, with staggered ends[50−57] Cas12j

(CasΦ)Recognizes PAM at the 3' end of target sequences and initiate staggered cleravages on both target and non-target DNA strands Is smaller than other Cas proteins, with 700 to 800 residues [58,59] Based on Zhang et al.[3] Table 2.

Some examples of classes/types and signature/standard proteins of CRISPR/cas systems for editing the plant genome.

-

Type Name Modification PAM Ref. Engineered Cas9 variants Cas9 nickase (nCas9) Point mutations D10A in the RuvC domain or H840A in the HNH domain

only cleaves the targeting or non-targeting strand, respectivelyNGG [61] Dead Cas9 (dCas9) Simultaneously promotes point mutations D10A in the RuvC domain or

H840A in the HNH domain nuclease activity is abolishedNGG, NGN, NNG, and NNN [62] SpCas9 VQR Point mutations 1135V/R1335Q/T1337R NGA [63] SpCas9 EQR Point mutations D1135E, R1335Q, and T1337R NGAG [63] SpCas9 VRER Point mutations D1135V, G1218R, R1335E, and T1337R NGCG [63] xCas9 Point mutations A262T/R324L/S409I/E480K/E543D/M694I/E1219V NG, GAA and GAT [64] SpCas9-NG Point mutations R1335V/L1111R/D1135V/G1218R/E1219F/A1322R/T1337R NG, GAA and GAT [65] SpRY Point mutations A61R/L1111R/N1317R/A1322R/R1333P NGN [66] iSpyMacCas9 Point mutations R221K and N394K NAAR [67] Cas9 orthologs Staphylococcus aureus

Cas9 (SaCas9 KKH)Point mutations E782K/N968K/R1015H NNGRRT [68] Streptococcus thermophilus Cas9 (St1Cas9) − NNAGAA [69] Brevibacillus laterosporus Cas9 (BlatCas9) − NNNNCND [70] Streptococcus macacae Cas9 (SmacCas9) − NAA [71] Lactobacillus rhamnosus Cas9 (LrCas9) − NGAAA [72] Faecalibaculum rodentium Cas9 (FrCas9) Point mutations E796A, H1010A, and D1013A NNTA [73] Cas12 orthologs AsCas12a − TTTV [74] AsCas12a RR Point mutations S542R/K607R TYCV and CCCC [75] AsCas12a RVR Point mutations S542R/K548V/N552R TATV [75] enAsCas12a Point mutations E174R/S542R/K548R VTTV, TTTT, TTCN, and TATV [76] LbCas12a − TTTV [74] LbCas12a RR Point mutations G532R/K595R TYCV and CCCC LbCas12a RVR Point mutations G532R/K538V/Y542R TATV [75] FnCas12a − TTV, TTTV, and KYTV [77] FnCas12a RR Point mutations N607R/K671R TYCV and TCTV [77] FnCas12a RVR Point mutations N607R/K613V/N617R TWTV [77] N can be any purine or pyrimidine base (A, G, C, or T). Based on Zhang et al.[3] Table 3.

Some examples of Cas9 engineered/orthologs and other Cas mutated for new possibilities for editing plant genomes.

-

Modification Approach Main features knock-in HDR after SSN

actionGene activation enhanced by

long ssDNA donorsknock-out NHEJ or HDR after

the action of SSNsLower in polyploid than diploids

plant speciesPoint mutations Base editing Depends on CBEs and ABEs Epigenome editing CRISPR-directed methyltransferases

and demethylasesEditing epigenetic marks for

transcription regulationGene replacement NHEJ or HDR

(preferred) after

the action of SSNsHomology-dependency among

DSB flanks and donor template

flanksMultiplexed

genome

editingCRISPR array Long transcripts with multiplexed

sgRNAs for multiple

simultaneous editings

Expression or delivery of sgRNAs

through ribonucleoproteins

(RNPs) or particle bombardmentGene

transcriptional

regulationCRISPR array Cas9 fusion with various

transcription effectors can be

used to repress or activate

transcription.Chromosomal

rearrangementCRISPR array Target highly endogenous

retrotransposons and LINEsTable 4.

Main approaches available for editing the plant genome and the types of alterations brought about by them.

-

Application Main features Purposes Limitations Edited plants Ref. Thermal sensitivity of CRISPR/Cas9 and Cas12a Optimal editing efficiency under higher temperatures Increased efficiency of CRISPR/

Cas9 and Cas12a by thermal

sensitivityFew plants tested Arabidopsis (29 °C) and maize (28 °C) [131] Generation of transgene-free edited plants Elimination of CRISPR transgenes

by segregation associated with screening with selection marker

genes/reporter genes

Editing of plant genomes without

the integration of exogenous DNA,

by the transient expression of the CRISPR/Cas machineryMinimize regulatory issues,

enhance public acceptance

and improve biosafetyNot feasible for vegetatively propagated plants, trees, polyploids and self-incompatible plants Arabidopsis, wild tobacco lettuce. rice, apple, grape, Petunia, hybrid, and soybean [120] Editing of polyploid

plantsMultiallelic genome editing in polyploid plants Introduction of valuable

traits in polyploid plantsLow efficiency, labor

and time-consumingAutopolyploid lines of Arabidopsis, Tragopogon (Asteraceae), potato (Solanum tuberosum) and Rape (Brassica napus) [132] Generation of germline-edited plants Genome editing using CRISPR delivered by Agrobacterium before embryogenic cell division To improve downstream genetic

and trait analysisLow editing efficiency

in germlinesArabidopsis [133] Off-target minimization Use wild-type Cas9 and Cas12a,

nCas9s and high-fidelity versions of SpCas9 design of low-mismatch sgRNAs to limit the exposure of the genome to CRISPR componentsTechnical improvement of

editing systems

Minimize the major concern of

CRISPR technologyMany high-fidelity SpCas9s show intrinsically lower nuclease activities

in plantsrice [134,135] Improve plant breeding To express plant growth-stimulating genes use of haploid induction-edit and haploid-inducer mediated genome editing (IMGE) To enhance genome editing by

CRISPR in recalcitrant plant

species and varieties

To increase stable inheritable of desirable traits through many generationsInevitable segregation

in seed productionSorghum (Sorghum bicolor), sugarcane, and indica rice [136,137] Table 5.

Recent applications of CRISPR/Cas for genomic manipulation in plants and their main challenges.

Figures

(5)

Tables

(5)