-

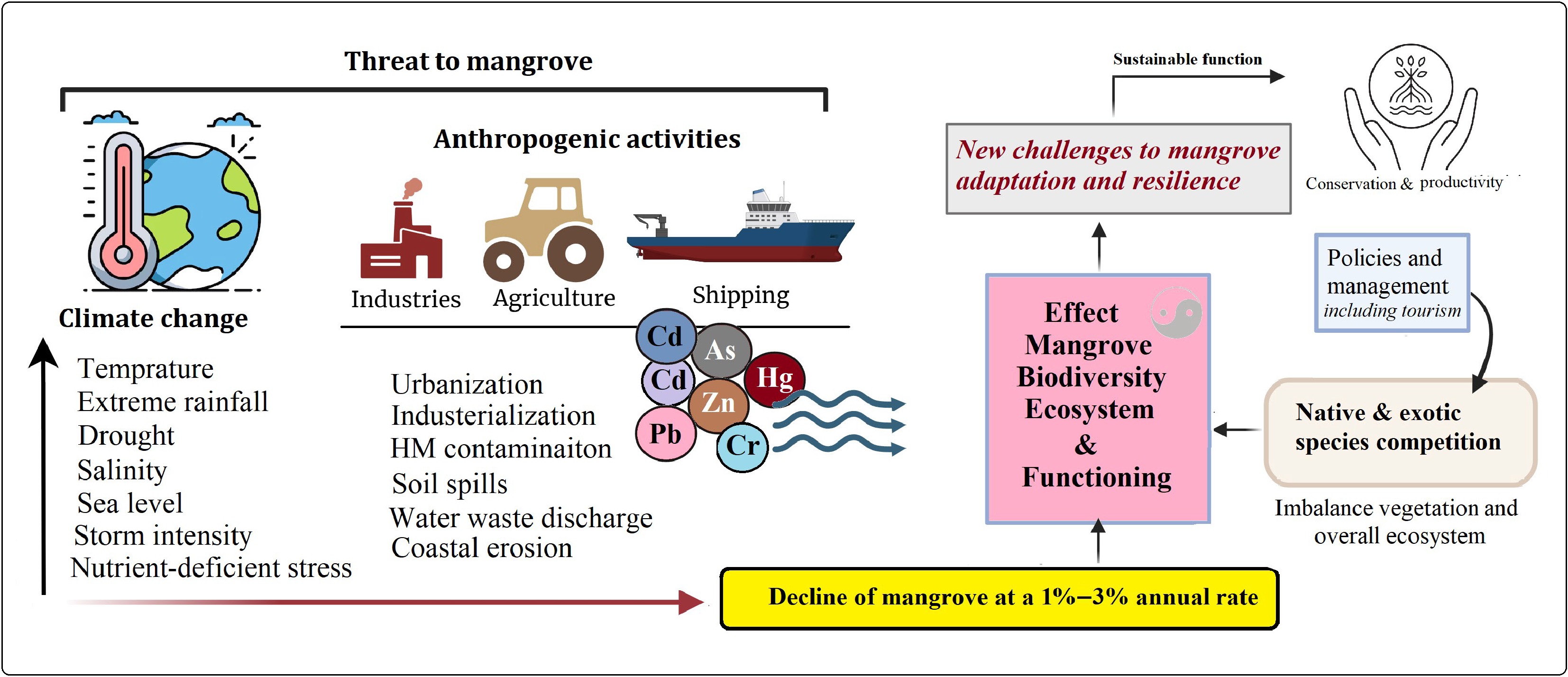

Figure 1.

Increasing climate change and anthropogenic pressures negatively affect mangrove ecosystem functioning by reducing community stability and increasing heavy metals (HMs) toxicity. These impacts are further compounded by outdated management policies that intensify competition for resources between exotic and native species, destabilizing biodiversity and vegetation structure. Consequently, mangroves face major challenges to their resilience and adaptive capacity under changing environmental conditions. Addressing these challenges and enhancing mangrove resilience will improve their functions and help conserve them for the future amidst increasing climate change.

-

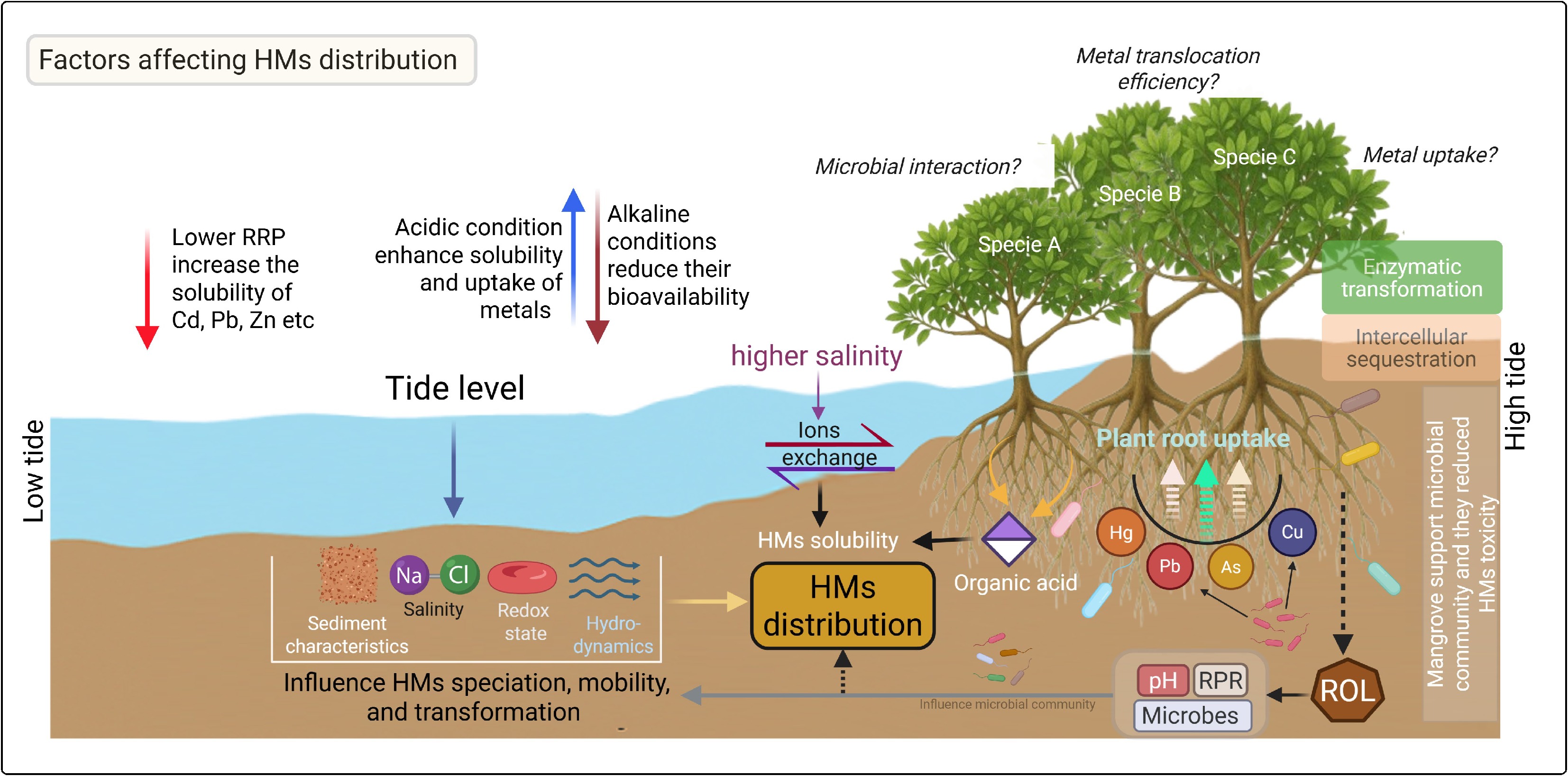

Figure 2.

An overview of heavy metals (HMs) distribution and the key factors influencing HM dynamics and interactions within the mangrove ecosystem. Tidal level affects sediment characteristics, salinity, redox state, and overall hydrodynamics, which in turn regulate HM mobility and speciation, thereby controlling their distribution across tidal zones. Elevated salinity promotes ion exchange processes that alter HM solubility and accumulation in sediments. Additionally, organic acids released by mangrove roots enhance HM solubility, further influencing their spatial distribution. Microbial activity in the rhizosphere plays a crucial role in HM transformation, interacting with root-mediated radial oxygen loss (ROL) and root redox potential (RRP), which collectively influence sediment pH and HM bioavailability. The uptake, translocation (root-to-shoot ratio), and detoxification capacity of mangrove species further determine overall HM distribution. These processes depend on species-specific traits, including enzymatic transformation efficiency and intracellular sequestration mechanisms.

-

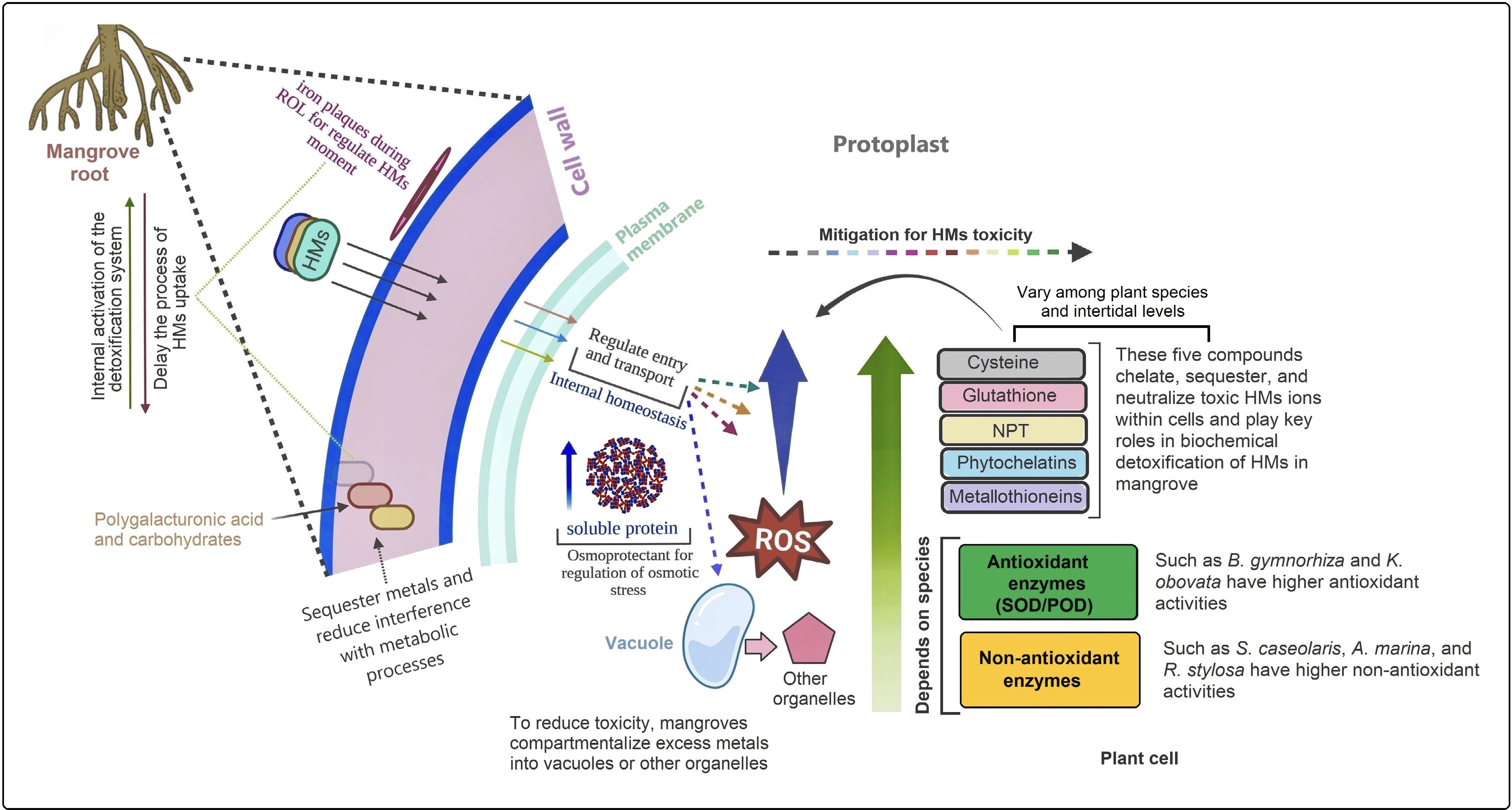

Figure 3.

Cellular detoxification mechanisms of heavy metals (HMs) in mangroves. Mangroves absorb HMs through their cell walls and initially reduce toxicity by forming iron plaques during radial oxygen loss (ROL). This process helps maintain internal and external equilibrium between HM uptake and detoxification, facilitated by carbohydrates and polygalacturonic acids in the cell wall. The plasma membrane further regulates HM transport to preserve cellular homeostasis. To mitigate toxicity, mangroves enhance the synthesis of cysteine, glutathione, non-protein thiols (NPTs), phytochelatins, metallothioneins, and antioxidants, which scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neutralize HM ions. Additionally, osmo-protectants and soluble proteins are upregulated to alleviate osmotic stress. Under high HM exposure, cells compartmentalize metals into vacuoles and other organelles to limit cytoplasmic toxicity. Through these integrated physiological and biochemical processes, mangroves detoxify and tolerate HMs. However, the efficiency and specific mechanisms vary among species, reflecting differences in adaptive strategies to HM stress under contrasting tidal conditions.

-

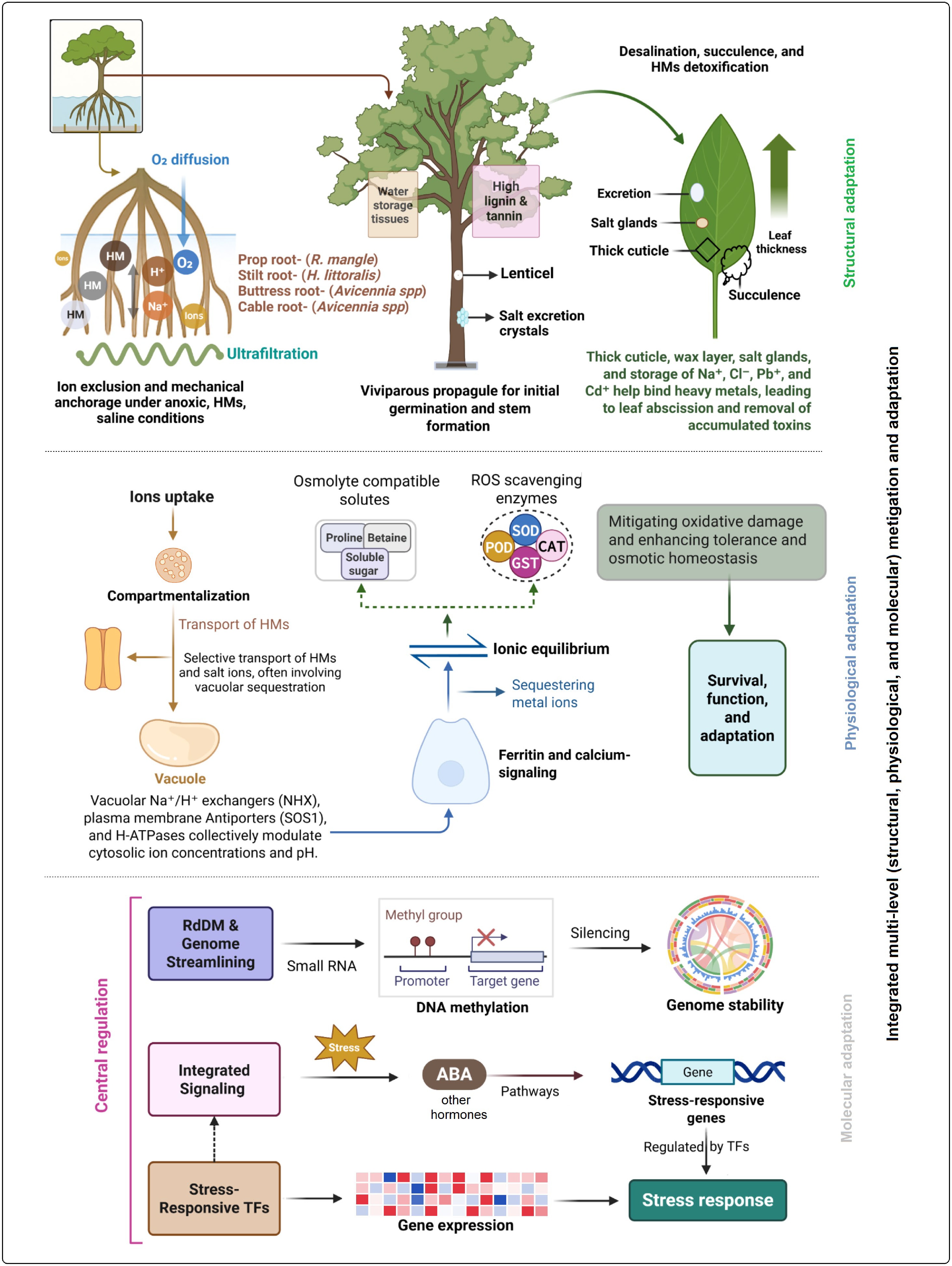

Figure 4.

Integration of morphological, physiological, and molecular adaptations of mangrove plants to heavy metals (HMs). Distinct root structures and types function in filtration, viviparous propagule development during germination, and gas exchange through lenticels, while salt excretion from stems, thick leaf structures, leaf-based excretion, waxy layers, and thick cuticles contribute to HM transformation and exclusion. In parallel, coordinated mechanisms of redox balance, ion transport, and osmotic adjustment mitigate HM toxicity. At the molecular level, genome streamlining, integrated signaling pathways, and the regulation of stress-related genes collectively enhance stress tolerance. Together, these mechanisms enable mangrove plants to survive, adapt to, and transform heavy metals within their environment. SOD, superoxide dismutase; POD, peroxidase; CAT, catalase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RdDM, RNA-directed DNA methylation; ABA, abscisic acid; GST, glutathione S-transferase; TFs, transcription factors.

-

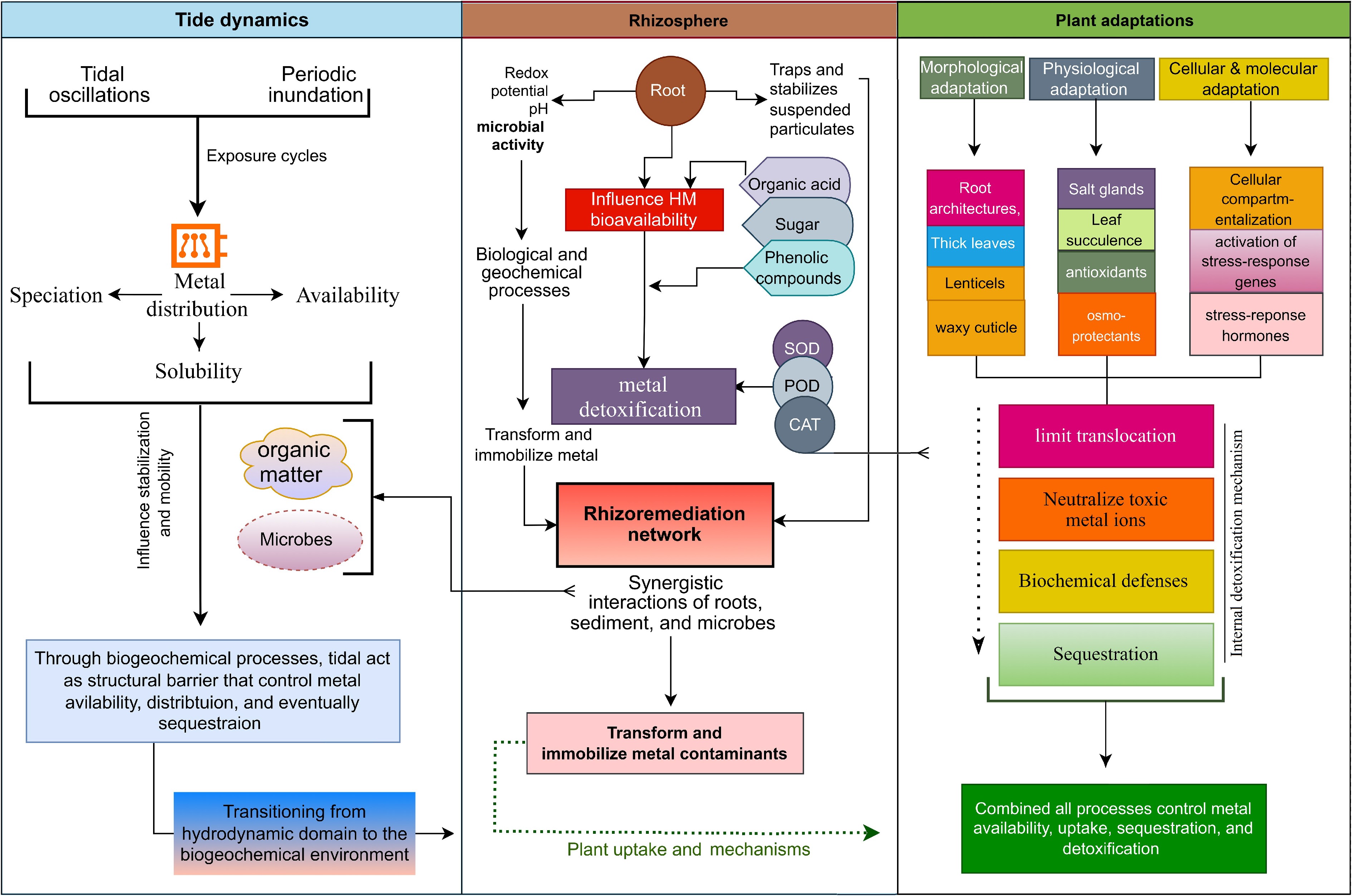

Figure 5.

Integrated tide–rhizosphere–plant dynamics in heavy metals (HMs) transformation. Tidal oscillations and periodic inundation regulate HM distribution by influencing metal speciation, solubility, and bioavailability. Tide levels serve as structural barriers, while the organic acids released by mangrove roots and rhizospheric microbial activity further influence HM toxicity and transformation. Biochemical processes involving sugars, phenolic compounds, and antioxidants (SOD, superoxide dismutase; POD, peroxidase; CAT, catalase) contribute to HM immobilization and transformation through rhizoremediation pathways. The synergistic interactions among sediments, roots, and microbes facilitate HM immobilization, uptake, and detoxification via cellular, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms, including ion translocation and intracellular sequestration. Collectively, these interconnected processes control HM transformations from sediments through tide–root–plant interactions within the mangrove ecosystem.

-

Heavy metal Concentration (mg·kg−1) Location/country Major sources Ref. As 14.0 Xiamen Bay, China Industrial wastes, shipping activities [49] 3.6−18.3 Bay of Bengal, India Tidal waters, fresh water rivers, and storm water runoff [50] 0.52–35 Sydney, Australia Urbanization and population growth [51] Pb 20.07 Zhanjiang Bay, China Agricultural production activities [52] 7.38 Meghna River Estuary, Bangladesh Anthropogenic sources, particularly near shipbreaking [53] 105 Shenzhen, China Rapid urbanization and industrialization [54] 0.7–13.37 São Paulo State, Brazil Fishing and waste disposal [55] 42.27 Sanya-Hainan, China Wastewater's discharge [56] Cu 18.24 Zhanjiang Bay, China Rapid urbanization and industrialization [52] 35.74 Meghna River Estuary, Bangladesh industrialization [53] 400 Shenzhen, China Anthropogenic sources, particularly near shipbreaking [54] 12.44 Sanya-Hainan, China Wastewater's discharge [56] 0.74–9.42 São Paulo, Brazil Fishing and waste disposal [55] 256.0–356.6 Farasan Island, Saudi Arabia Sewage runoff, farming practices, and industrial discharge [20] Cd 0.09 Sanya-Hainan, China Home and industrial waste waters discharge [72] 1.04 Farasan Island, Saudi Arabia Sewage runoff and industrial discharge [27] 0.25−0.42 São Paulo State, Brazil Fishing and waste disposal [71] Zn 52.76 Sanya-Hainan, China Discharge of waste and home usage discharge [72] 352 Shenzhen, China Rapid urbanization and industrialization [36] 62.32 Meghna River Estuary, Bangladesh Anthropogenic sources, particularly near shipbreaking [70] 29.5–36.8 Farasan Island, Saudi Arabia Sewage runoff, farming practices, and industrial discharge [27] 4.49−49.51 São Paulo, Brazil Anthropogenic activities, such as fishing and waste disposal [71] Table 1.

Concentrations of HMs in mangrove sediments worldwide and their primary sources. Concentrations correspond to total HMs in mangrove surface sediments.

-

Mangrove species Main metals accumulation Accumulation capacity Tolerance mechanisms Ref. A. marina Pb, Cu, and As Higher roots accumulate high levels of Pb

and Cu; strong tolerance to As.Root Fe-plaque formation, secretion of low-molecular-weight organic acids, antioxidant enzyme activation, restricted metal translocation to shoots [18,74−77] K. obovata Pb and Cu Higher Cu enrichment ~70%; strong Pb tolerance Phytochelatin (PC-SH) synthesis, root sequestration, and cell wall binding [74,76,78] K. candel Cu Higher enrichment exceeds approximately 96% of its accumulated Cu By increasing antioxidant activities, including SOD, POD, and CAT activities [79] B. gymnorhiza Cu and Pb Moderate accumulation without sustained tolerance at high exposure Phytochelatin synthesis, antioxidant response, and limited ROL under Cu stress [80,81] R. stylosa Pb and Cu Moderate tolerates Cu up to 400 mg·kg−1 Restricted Cu translocation, decreased root permeability, root elongation, and ROL [47,81] R. apiculata Pb Moderate lower Pb accumulation Root sequestration and exclusion [82] A. corniculatum As High As tolerance but low overall HM accumulation Root immobilization and exclusion, limited translocation [51,83] A. alba Pb Moderate to high leaf accumulation Higher Pb accumulation and translocation of HMs to leaves [84] A. ilicifolius Pb Moderate to higher accumulation [71] S. hainanensis Cu Lower Cu accumulation Lower tolerance mechanism against Cu [85] Table 2.

Comparative heavy metal accumulation, capacity, tolerance, and their detoxification mechanisms of the dominant mangrove species.

-

Mechanism type Key processes/interactions Representative agents

(roots/microbes/compounds)Effects on HMs Ref. Physical trapping Sediment retention by complex root structures (prop roots, pneumatophores) Rhizophora, Avicennia, Ceriops, and Sonneratia roots Immobilization and reduced HM mobility [155,156] Chemical transformation Redox alterations, pH modification, precipitation of metal oxides/hydroxides Root oxygen leakage (ROL), organic acids, phenolics Adsorption and precipitation of metals, and altered speciation [153,157,

158]Biological absorption and biosorption Root and microbial uptake of metals Mangrove roots with Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Aspergillus, and Penicillium Bioaccumulation and detoxification [159,160] Microbial enzymatic transformation Redox reactions catalyzed by dehydrogenases, hydrolases, and oxygenases Rhizospheric bacteria and fungi Conversion to less toxic forms [149,161] Root exudate–microbe synergy Release of amino acids, sugars, and

organic acids promotes microbial metabolismRoot exudates; enzyme-producing microbes Enhanced degradation of organic pollutants; improved HM tolerance [148,149] Mutualistic plant–microbe associations Microbial assistance in nutrient cycling, stress tolerance, and HM detoxification S. apetala rhizospheric consortia Improved plant resilience and remediation efficiency [162,163] Table 3.

Rhizosphere-mediated mechanisms contributing to heavy metal (HM) detoxification in mangrove ecosystems.

Figures

(5)

Tables

(3)