-

Pepper (Capsicum spp.), a member of the family Solanaceae, is a major vegetable crop recognized for its high nutritional value, particularly its vitamin content, and for its characteristic pungency and aroma[1,2]. It can be used as a vegetable, seasoning, pigment, and medicine[3]. According to the statistics of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in 2023, the world's production of pepper, including both fresh and dry pepper, has reached approximately 44 million tons[4]. Pepper blight, caused by Phytophthora capsici L., is a devastating soil-borne disease in pepper production. It can affect the entire growth cycle of pepper, leading to seedling death, root rot, crown rot, stem rot, leaf spot, and fruit rot, causing severe economic losses to pepper production[5]. Currently, the prevention and control of pepper blight primarily relies on fungicides, including methoxy-acrylate, phenyl amide, and morpholine[6,7]. However, the long-term application of pesticides can easily lead to the development of phytophthora resistance and reduce the control effect. Furthermore, it may cause pesticide residue in pepper fruit and pollute the environment, and even affect human health[8−11].

Biocontrol, using beneficial microorganisms, has been extensively studied as a complementary strategy to reduce pesticide use[12,13]. The microbes present in the rhizosphere and root surface of pepper are primarily bacteria, followed by actinomycetes and fungi[14]. Researchers have identified various antagonistic microorganisms against pepper blight, including Actinomycetes, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Trichoderma, and Penicillium[15−18]. Due to their ability to produce endophytic spores with strong stress resistance and effective control over various plant diseases, Bacillus species have been widely investigated by researchers[19]. The properties of Bacillus, such as enhancing plant growth, inducing resistance against abiotic and biotic stressors, and inhibiting spore germination and mycelial growth of plant pathogens, suggest their potential use in soil fumigation belowground[20,21]. Several Bacillus species, such as B. subtilis, B. amyloliquefaciens, B. thuringiensis, and B. pumilus, have been reported to control fungal diseases, such as pepper blight[22−25]. Bhusal & Mmbaga[26] isolated three Bacillus species that suppressed the growth of P. capsici in vitro and phytophthora-infested soil, indicating their potential as an alternative method for pepper disease management.

In addition, beneficial microbiomes often act as plant regulators, regulating systemic resistance against various pathogens[27]. Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR) represent two major pathways involved in the systemic resistance response of plants[28,29]. Salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) are well-known hormones that play essential roles in regulating plant defense responses. SA is a crucial molecule in the SAR mechanism and induces SA-dependent signaling, whereas JA and ET are involved in the ISR mechanism. The SA, JA, and ET signaling crosstalk involves both synergistic and antagonistic interactions in plant disease responses, working together for plant disease resistance[30]. The induction and accumulation of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins in plants are key components of the defense response, which are involved in SA, JA, and ET signaling pathways[31,32]. Bacillus strains, such as B. amyloliquefaciens SQR9, induce plant resistance by activating signaling pathways and upregulating specific PR-genes[33].

Efficient screening of beneficial microbial strains is a critical prerequisite for conducting research on plant disease prevention and control. Isolating microorganisms with biocontrol potential from the natural environment is crucial for the development of effective disease management strategies. In this study, we aimed to isolate and characterize biocontrol strains with antagonistic effects against pepper blight diseases from the rhizosphere of pepper plants in Hainan province, China. To identify the antagonistic strains, a combination of morphological and molecular biology methods was employed. The selected antagonistic bacteria were then subjected to pot experiments conducted in a growth chamber to evaluate their efficacy against pepper blight diseases, and primarily analyze their lytic effect and regulation function. The identification and characterization of these biocontrol strains provide valuable bacterial resources for the biological control of pepper blight.

-

Phytophthora capsici Leonian strain LT1354 was used as the pathogen. LT1354 was maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates at 28 °C before use. The pathogen zoospores were collected from a 10% V8 juice agar medium, which was incubated at 28 °C until the mycelium were fully growing on the agar plate, and induced sporulation with light at around 5 d.

Plant growth conditions

-

Pepper cultivar HNUCB00081 (Capsicum baccatum), provided by the Pepper Germplasm Resource Bank of Hainan University, was used as plant material. HNUCB00081 seeds were sterilized at 70% ethanol for 1 min, and then in sodium hypochlorite (2%) for 3 min, then rinsed in sterile distilled water (SDW) several times. Sterilized seeds were germinated at 28 °C in the dark for 3−4 d on filter paper moistened with SDW. Germinated seeds were grown in plastic trays (50 wells) that contained a nursery substrate (Shandong Green Pearl Agricultural Technology Development Co., Ltd, Shangdong, China) in a growth chamber maintained at 28 °C under 14 h light and 10 h dark with 14,000 lux.

Isolation of Bacillus

-

To isolate Bacillus strains, soil samples were collected from the rhizosphere of healthy pepper plants from the fields in Haikou city (Hainan University and Yongfa town, 20°02'46" N,110°35'38" E), and Qionghai city (19°25'50" N, 110°46'5" E) of Hainan province, China. After the soil samples were sieved, about 10 g of soil was added to 90 mL SDW and shaken for 15 min at 150 rpm. The resultant soil suspension was heated at 80 °C for 10 min to remove any fungal and other bacterial contamination[34]. The soil suspension was serially diluted, sprayed on nutrient agar (NA) plates, and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. Different colonies were selected and streaked on new NA plates to obtain pure isolates. The purified strains were stored at 80 °C in skimmed milk (DifcoTM Skim Milk, Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) with L-Glutamic Acid Monosodium salt (Solarbio, C8320, pH 6.3) for further study.

Dual-culture in vitro assay

-

Dual-culture in vitro assay was used in this experiment to confirm the antibiosis activity of the isolated strains. The isolated strains were incubated on NA media at 30 °C for 24 h. Then the single colony was transferred to the nutrient broth and cultured at 30 °C at 200 rpm. Bacterial cells were collected from the cultured broth by centrifugation (5,000 rpm, 5 min), and suspended in SDW. The cell suspension was measured for the optical density at 600 nm (OD600 = 1.0). A mycelial plug (7 mm in diameter) of pathogen strain LT1354 was placed in the center of a 9-cm PDA culture plate. Five μL of the isolated bacterial suspension was inoculated equidistantly 2 cm away from the central plug, then the plate was incubated at 28 °C. Five μL of SDW replaced the bacterial suspension in the control treatment. During the time, the morphology of P. capsici hyphae at the edge of the colony was observed on an OLYMPUS CX33 biological microscope (OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan) under 10 ×/0.25 NA objective. The mycelial radius was measured to monitor the inhibition efficiency of the tested strains at the time when the mycelial radius of the control treatment fulled the plate, and calculated using the following formula:

$ \rm Inhibition\;efficiency\;({\text{%}})=(1-R1/R2)\times 100 $ where, R1 and R2 = P. capsici mycelial radial growth on the treatment and control plates, respectively.

Every strain was performed on three plates, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Detection of the lytic effect of the candidate strain

-

The lytic effect of the candidate strains was detected through proteases, cellulases, and iron carriers. In brief, five μL of the candidate bacterial cell strains (collected same as in 2.4) were incubated on protease solid culture medium (6.4 g skimmed milk powder and 6.4 g agar per litre) and Chrom azurol S medium (CAS, Beijing Kulaibo Technology Co., Ltd) to evaluate the ability of proteases and iron carriers, respectively. Five μL of SDW was used as a control treatment to replace the bacterial cell. All the plates were incubated in a growth chamber at 28 °C for 3–5 d, and observed for the formation of a transparent circle.

Cellulases were detected by the Congo Red colorimetric method. Candidate strains were cultured on cellulase solid culture medium (1.0 g sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, 1.0 g peptone, 1.0 g yeast powder, 0.1 g potassium dihydrogen phosphate, 0.5 g sodium chloride, and 1.8 g agar) for 2 d at 28 °C. The plates were then stained with 1 mg/mL Congo Red solution for 1 h, followed by washing with 1 mol/L NaCl for 1 h. The presence of clear decolorization zones around the bacterial colonies indicates cellulase activity. These experiments were repeated three times, with three replicates per assay.

Identification of candidate strains

-

The stored candidate strains were streaked on an NA plate and incubated at 28 °C for 1 d. Then the colony characters were observed after appropriate growth. The morphological properties were examined by light microscopy and TEM. Physiological and biochemical parameters were assessed using EasyID Biochemical Identification Kit for bacteria (Huankai Biology).

Molecular identification of the candidate strains was based on two concatenated housekeeping genes, 16S rRNA and gyrB. The primers and amplification conditions for genea are shown in Supplementary Table S1[35,36]. The DNA of the strains was extracted using FastPure® Microbiome DNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme, China). The PCR conditions were as follows: (1) For the 16S rRNA gene: one cycle of pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 25 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 8 min; (2) For gyrB gene: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles at 94 °C for 60 s, 53 °C for 60 s, and 72 °C for 90 s, and a final extension of 8 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were sent to Nanshan Bio-Company (Haikou city of Hainan Province, China) for sequence analysis. The partial gene sequences were BLASTN at the Gene bank database of NCBI. The phylogenetic trees were constructed with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method using MEGA version 11.0[37].

Control effect of the candidate strains on pepper blight in pot experiments

-

Pepper seedlings at the four to five leaves stage were transplanted to 12 cm × 13 cm pots containing 300 mL of the sterilized nursery substrate (autoclaving 30 min at 121 °C), evenly irrigated with 5 mL of candidate strains' cell suspension at ca. 1–2 × 108 CFU/mL (the culture conditions are the same as the section of dual-culture in vitro assay) around the roots of each pot. The same volume of SDW replaced the candidate strains cell suspension and was used as a control treatment. Three days later, each pot was inoculated with 5 mL of P. capsici spore suspension at 105 spores/mL by injuring the root and drenching root methods. The seedlings were maintained in a greenhouse at 25 °C ± 3 °C day/night. Disease severity was monitored for 21 d using a scale of 0–5, where: 0 = no symptoms, and 5 = complete necrosis[26]. The experiment was conducted in three replicates, with 10 plants for each replicate.

Defended related gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR

-

Root samples were taken to analyze the expression of pathogenesis-related protein 1 (PR1), basic β-1,3-glucanase (PR2), pathogenesis-related protein 4 (PR4), pathogenesis-related protein 10 (PR10), and proteinase inhibitor II (PIN-II) genes[38,39]. The primers used, including a housekeeping gene Actin, are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Pepper seedlings and inoculation methods were the same as pot experiments. After inoculation with P. capsici, around 1.0 g roots of two random plants of each treatment (Control, H12 treatment, and H23 treatment) at 1 d, 3 d, and 5 d were sampled, and then quickly put in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Total RNA extraction was performed using the FastPure Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Nanjing Nuoweizan Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China). Five hundred ng of total RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA, and as templates for qRT-PCR.

A total volume of 10 μL was used for qRT-PCR reaction analysis, including 5 μL of ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Nanjing Nuoweizan Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China), 1 μL of cDNA, 0.5 μL of 10 μM of each primer, and 3 μL RNase-free water. Reactions were run in three-step, denaturation for 30 s at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C, 10 s at 60 °C amplification, and melting 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 15 s at 95 °C by AriaMx Real-time PCR System (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) in triplicate. Relative quantification of the expression of genes was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method[40]. The difference between the treatments was determined by Tukey's test at p = 0.05.

Statistical analysis

-

All the data were statistically analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel 2019. A least significant difference test was performed at a significance level of p < 0.05.

-

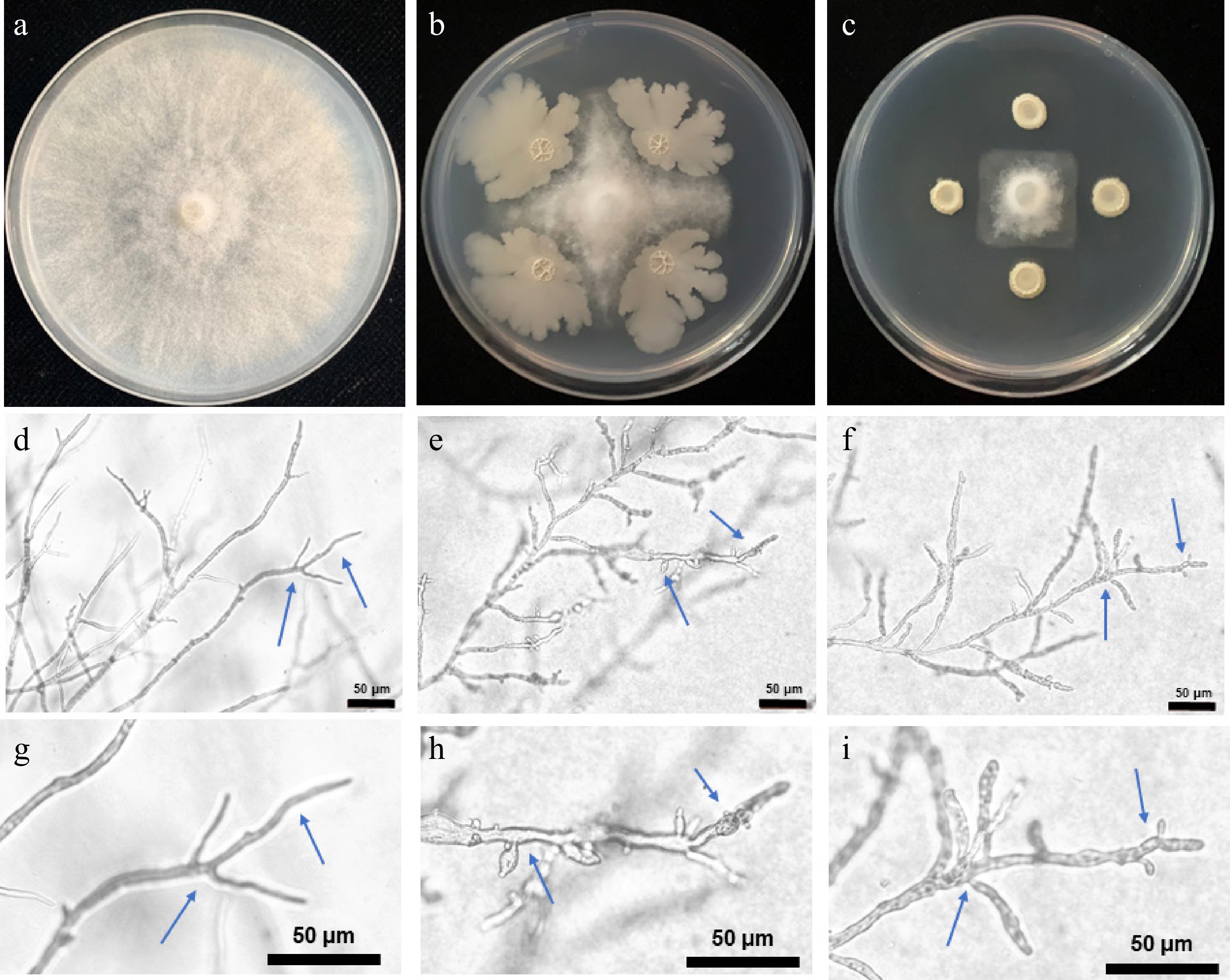

Based on the different colonies on the NA plate, 30 isolates were isolated from soil suspension (Supplementary Table S3). In the dual-culture screening, two isolates, H12 and H23, had obvious inhibition against P. capsici (Fig. 1). Compared to the control treatment (Fig. 1d & g), the hyphae of P. capsica in the H12 and H23 treatments appeared short, swelling, and twisted, and the tip of the hyphae swells to form vesicles or abnormal branching structures, leading to hyphal deformities and cessation of growth (Fig. 1e, f, h & i). When the radial growth of the control treatment reached 7.8 cm, the radial growth of H12 and H23 treatments was 1.9 cm and 1.4 cm, respectively. They showed significant antagonistic activity with 75.6% and 82.1% inhibition, respectively, compared to the control (Table 1). These two strains were selected as the candidate strains for further experiments.

Figure 1.

Inhibition effect of the isolated strains against P. capsici in the dual cultures and the mycelial morphology. (a), (d), and (g): Control (SDW); (b), (e), and (h): H12 treatment; (c): H23 treatment. Pictures were recorded on the day when radial growth of the control treatment was middle (d)–(i), and full (a)–(c) of plate. The blue arrows indicate the different forms of hyphae.

Table 1. Inhibition effect of the isolated strains against Phytophthora capsici.

Strain number Radial growth (cm)δ Inhibition efficiency (%)ε Control 7.8 ± 0.1aφ − H12 1.9 ± 0.3b 75.6% H23 1.4 ± 0.2b 82.1% δ The mean values of three independent measurements of radial growth (± standard deviation) of P. capsici, which were recorded on the day when radial growth of the control treatment was a full plate. ε Inhibition efficiency (%) = (1 – R1/R2) × 100, where, R1 and R2 = P. capsici mycelial radial growth on treatment and control plates, respectively. φ Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differences between the different strains at the 0.05 level. Characterization/identification of the candidate strains

-

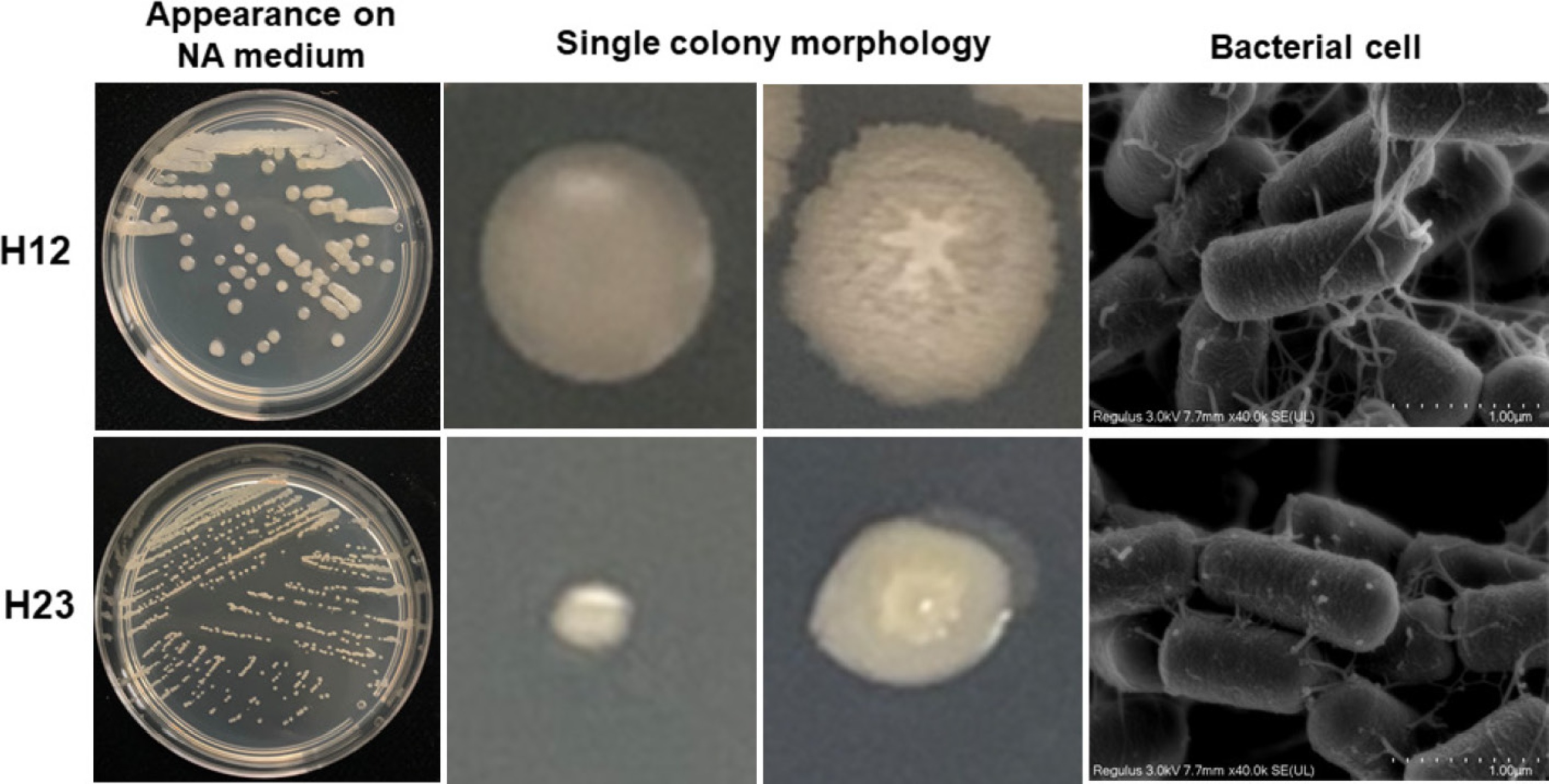

H12 and H23 strains were streak cultured on NA medium for 24 h, and their morphological characteristics are shown in Fig. 2. The colony of H12 on the NA plate was 3–4 mm in appearance, showing milky white, opaque shape, convex and smooth, near round, irregularly serrated edges. The colony of H23 on the NA plate was 0.5–1.5 mm in appearance, showing a pale yellow, convex surface, oval, and irregular serrated edges. Bacterial cells of strains H12 and H23 were both rod-shaped. The physiological and biochemical identification results of strains H12 and H23 are shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Figure 2.

Colony morphological characteristics of H12 and H23. From left to right are appearance on NA medium at 18 h. Single colony morphology at 18 and 24 h, scanning electron micrographs of bacterial cells.

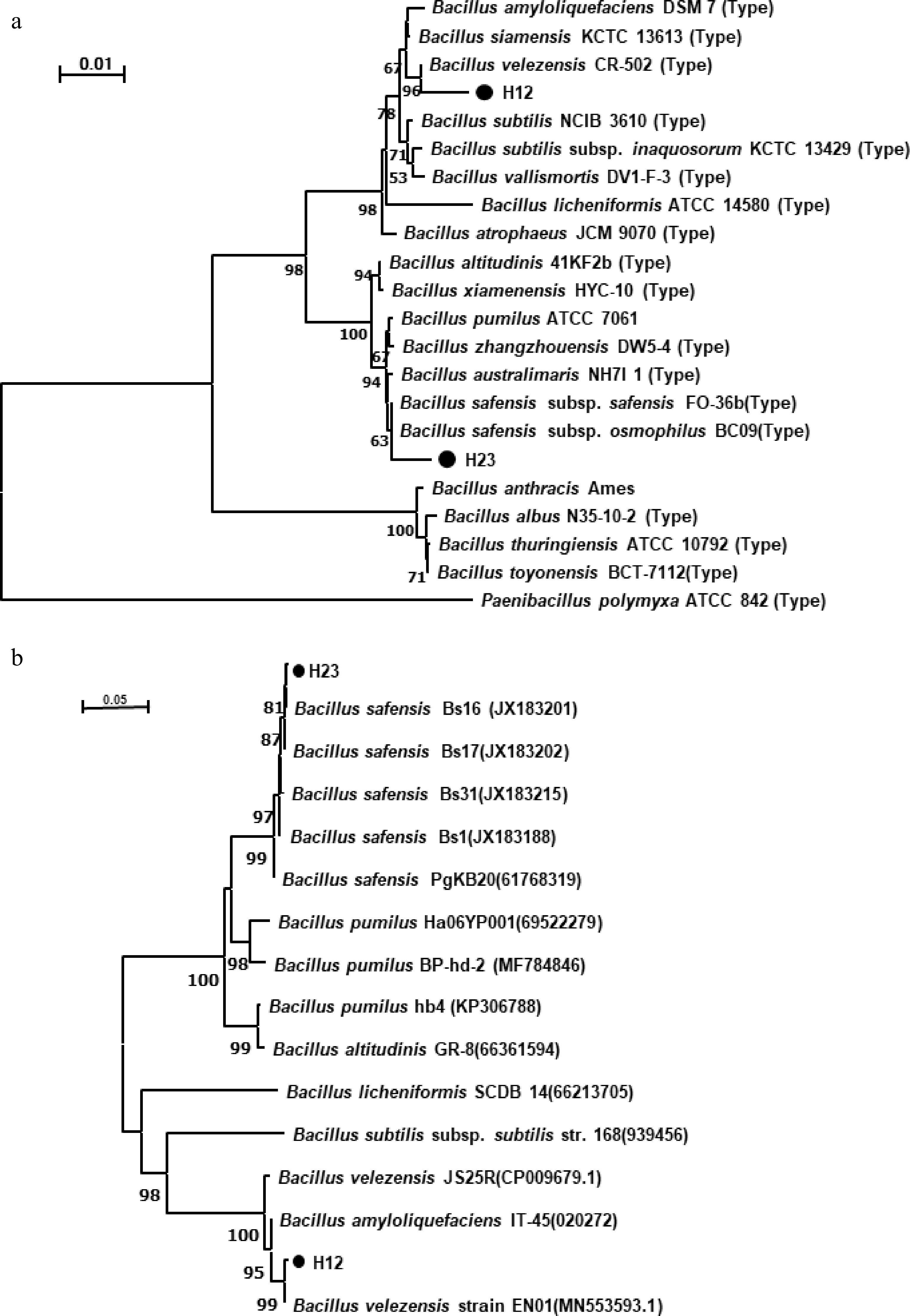

The 16S rRNA gene fragments were amplified from the total DNA isolates of H12 and H23 and sequenced, yielding sequences of 1,452 bp for both isolates. Based on BLAST analysis against the NCBI database, both H12 and H23 were found to be phylogenetically affiliated with members of the genus Bacillus. Strain H12 shared 99.79% and 99.93% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity with B. amyloliquefaciens and B. velezensis, respectively. Strain H23 was identical (100%) to B. safensis and shared 99.93% identity with B. pumilus. The NJ phylogenetic tree showed that strain H12 formed a cluster closely related to B. velezensis, and H23 formed a cluster closely related to B. safensis (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic trees based on (a) 16S rRNA, and (b) gyrB genes sequences of strains H12 and H23. Numbers in parentheses represent the sequences accession number in GenBank. The number at each branch point is the percentage supported by bootstrap (values expressed as percentages of 1,000 replicates). Bar 0.5% sequence divergence. Type indicates the type strain.

To further classify the strains, their gyrB gene was analyzed and sequenced. BLAST was used to query this sequence against an NCBI database and an NJ phylogenetic tree constructed. Results showed that strain H12 clustered closely with B. velezensis, whereas strain H23 exhibited a close relationship with B. safensi (Fig. 3b). Therefore, based on morphological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics, and 16S rRNA and gyrB gene sequence source analysis, H12 was identified as B. velezensis, named B. velezensis strain H12 (NCBI Accession No. PQ443883), and H23 was identified as B. safensis, named B. safensis strain H23 (NCBI Accession No. PQ443884).

Biocontrol effect of strains H12 and H23 against P. capsici in the greenhouse

-

To evaluate the biocontrol effect of the candidate strains, a pot experiment under greenhouse conditions was conducted. Results showed that (Fig. 4), the symptoms of P. capsici appeared in the control plants at 3 d post-pathogen inoculation (dpi), while the H12 and H23 treatment plants showed symptoms from 5 and 8 dpi, respectively. The disease severity was significantly reduced by H12 and H23 treatment compared with the control at 14 dpi. At 21 dpi, the control plants were wilted and showed disease symptoms caused by P. capsici, with a disease severity of 90%. Disease severity of plants inoculated with strains H12 and H23 was 51.3% and 18.0%, showing a significant decrease of 43.0% and 80.0%, respectively. This indicates that strains H12 and H23 have potential resistance against P. capsici disease.

Figure 4.

Biocontrol effect of H12 and H23 on pepper blight under greenhouse conditions. (a) Disease severity of pepper blight under H12 and H23 treatments. (b) Pictures of Control, H12, and H23 treatments that were taken at 21 d post P. capsici inoculation. Disease severity (%) = ∑ (Number of diseased plants at each level × Disease grade value)/Total number of surveyed plants × Highest disease grade value × 100. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of three biological replicates per treatment. Different letters indicate significant difference between treatment and control according to Tukey's t-test at p < 0.05.

The extracellular enzymatic activity of strains H12 and H23

-

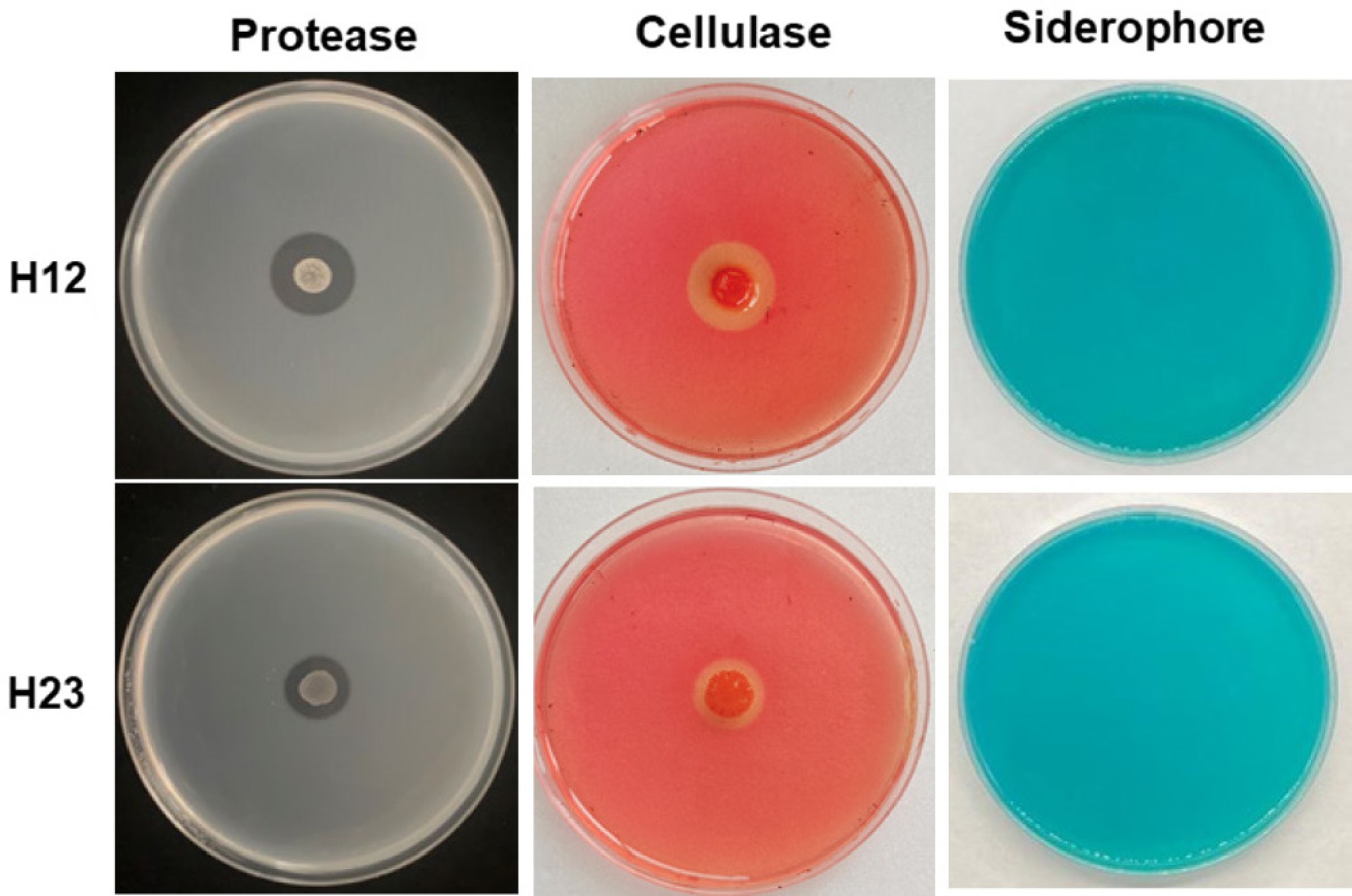

Proteases, cellulases, and iron carriers were detected by the culture medium detection method. As shown in Fig. 5, both strain H12 and H23 produced significantly transparent circles on the proteases and cellulases solid culture medium compared to the control. However, in the Chromazurol S medium plate, there were no transparent circles under either H12 or H23 treatment. Results indicated that strains H12 and H23 have the potential to degrade proteins and cellulose, which are associated with antagonistic activity against P. capsici.

Figure 5.

The extracellular enzymatic activity of strains H12 and H23, where there were proteases, cellulases, and iron carriers from left to right.

Expression of defense-related genes in pepper under strain H12 and H23 treatment

-

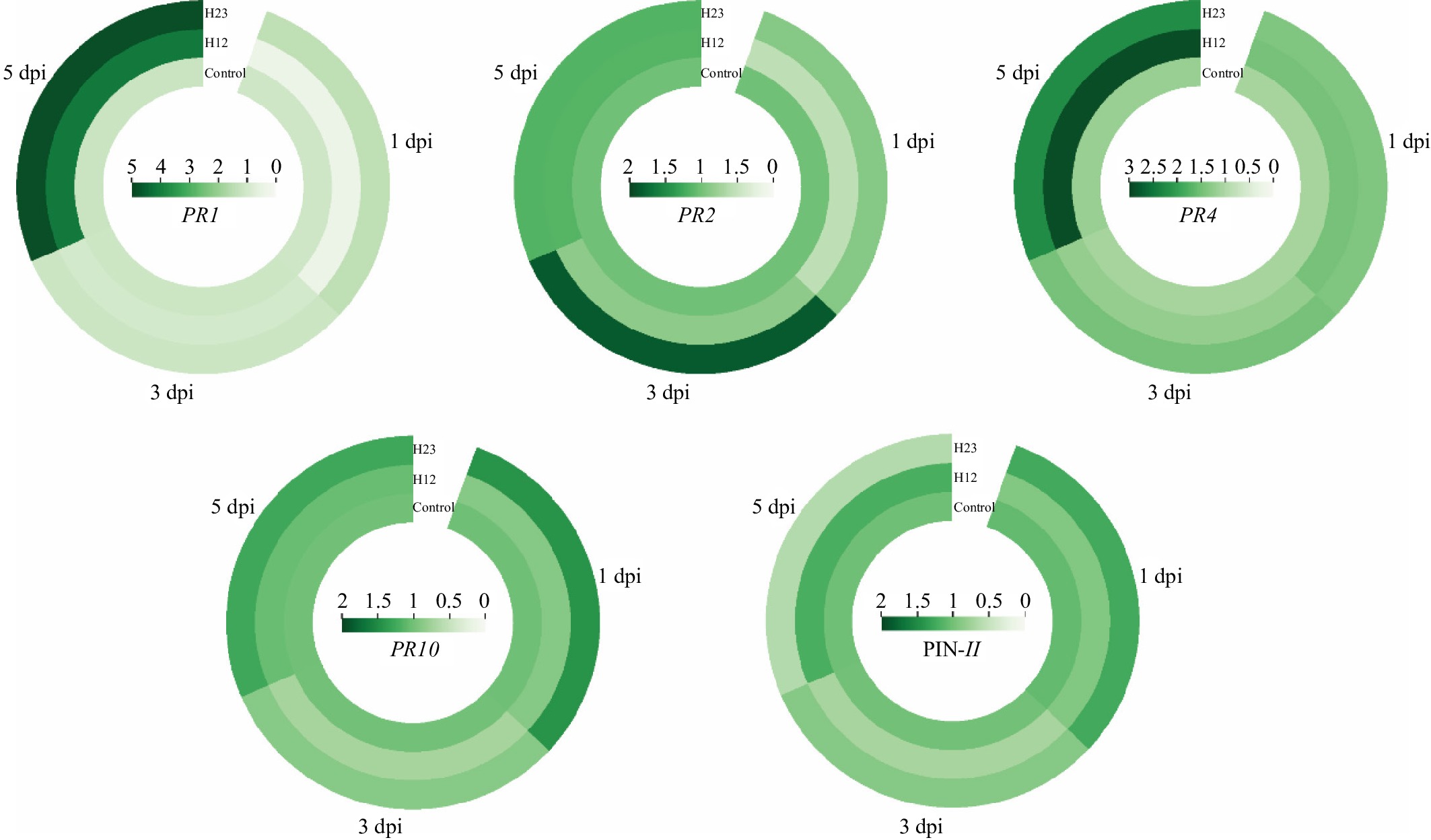

To confirm defense inducing resistance, the expression of five PR genes, including PR1, PR2, PR4, PR10, and PIN-II were analyzed at 1, 3, and 5 d post P. capsici inoculation following by pre-treatment with H12 and H23 (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. S1). Plants treated with H12 had higher gene expression of PR1 and PR4 at 5 dpi, with a 4.1 and 2.9 times expression higher than that of control, respectively. There was no observed difference in PR2 and PR10 expression. While the expression of the PIN-II gene showed a significant reduction under H12 treatment. Furthermore, plants treated with H23 showed a higher expression of PR1 and PR4 genes compared to the control treatment at 5 dpi. In addition, H23 significantly induced the expression of PR10 at 1 dpi, and had a higher expression of PR2 at 3 dpi. There was no obvious expression of PIN-II under H23 treatment. These results indicated that plants treated with H12 and H23 have similar defense reactions, which are related to the SA/JA signaling pathway at 5 d post P. capsici inoculation.

Figure 6.

Expression of PR1, PR2, PR4, PR10, and PIN-II in pepper at 1 d, 3 d, and 5 d after inoculation with P. capsici under H12 and H23 pre-treatment. The circular cluster plot of different colors based on the data range (displayed in the middle of each circle) showed the variations in each treatment.

-

Biological control is regarded as a promising alternative to the use of pesticides and the enhancement of plant resistance, playing a pivotal role in the management of plant diseases within the framework of sustainable and environmentally friendly agricultural development[41]. Antagonistic effects are one of the main approaches for screening biocontrol agents[42]. Hamanoka et al.[43], Asaturova et al.[44], and Chen et al.[45] have screened antimicrobial Bacillus strains against various fungal diseases. Shen et al.[46] revealed that B. velezensis SH-1471 had broad-spectrum antagonistic activity against a variety of plant pathogenic fungi. In our study, strains H12 and H23 showed a strong antagonistic effect against P. capsici in vivo (Fig. 1, Table 1), indicating their potential as promising biological control agents in the future.

The identification of bacterial strains is generally based on 16S rRNA, which makes it difficult to distinguish closely related species. More researchers are constructing phylogenetic trees using conserved genes such as GyrA, GyrB, and RpoB to further determine the taxonomic status of Bacillus species[47−49]. In the present study, the results of 16S rRNA gene analysis revealed that the H12 strain had similarity with B. velezensis, and strain H23 had similarity with two subsp. of B. safensis (Fig. 3a). gyrB gene analysis was conducted to identify both strains, which ensured the result of 16S rRNA gene analysis (Fig. 3b), and thus identified them as B. velezensis H12, and B. safensis H23.

B. velezensis and B. safensis sp. nov. have been recently identified, and have a broad range of disease resistance effects[50−53]. Sun et al.[54] identified a B. velezensis strain BVE7, exhibiting broad-spectrum activity against various pathogens causing soybean root rot. Wei et al.[55] inferred that B. velezensis YW17 inhibited F. oxysporum by secreting antifungal lipopeptides, proteins, and volatile substances, thereby indirectly protecting ginseng from pathogenic fungal infections. Shen et al.[46] provided evidence for B. velezensis SH-1471 as a beneficial rhizosphere bacterium in plants by whole genome sequencing. The results of Rong et al.[56] showed that B. safensis strain B21showed bioactivity against Magnaporthe oryzae in vitro and in vivo, and biocontrol efficiency on rice blast in the field. The present study showed that B. velezensis H12 and B. safensis H23 enhanced resistance against pepper blight disease with high efficacy under greenhouse conditions (Fig. 4). These results indicate that B. velezensis H12 and B. safensis H23 have potential applications in pepper blight. Further study is needed to optimize the application of these biocontrol agents and assess their performance under field conditions.

Antagonistic Bacillus can target the plant and activate defense signaling. Results of qRT-PCR analysis displayed that treatment with H12 and H23 enhanced PR1 and PR4 gene expression in pepper (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. S1). PR1 and PR4 genes have been shown to rely on the SA and JA signaling pathway[31], indicating that H12 and H23 enhanced resistance in pepper against P. capsici by activating the SA/JA defense response signaling. The gene expression in the plants involving H12 and H23 treatments was higher than control at 5 dpi, but not at 1 or 3 dpi (Fig. 6). However, the significant disease suppression was seen from 3 dpi (Fig. 4), indicating that the control effect of H12 may mainly rely on the antagonist effect at the early infection stage, and then induce SA/JA signaling pathways later. The results demonstrated that beneficial bacteria showed an antagonist effect and stimulated a defense response against plant disease. Wu et al.[39] identified a Bacillus subtilis SL-44 that controls Rhizoctonia solani via induction of the defense mechanism and antimicrobial effect. Bai et al.[57] screened a strain of B. velezensis which showed an antagonistic effect on Alternaria solani and induced the resistance of potato seedlings to early blight by triggering JA/ET pathways. Moreover, strain H23 also induced PR10 gene expression, which enhanced HR-like cell death and activated defense signaling. The present results showed similarity to the results of Li et al.[38], which identified a rhizobacteria B. pumilus S2-3-2 also enhanced the PR1, PR4, and PR10 genes expression, causing systemic resistance (ISR) in tobacco.

Bacillus spp. produce a variety of hydrolytic enzymes such as chitinases, cellulases, xylanases, and glucanases that contribute to the control of fungal pathogens, and proteases[58,59]. Bacillus subtilis RH5 possesses hydrolytic enzymes involved in defense in rice plants against R. solani[60]. Results from the present study showed that both H12 and H23 could produce cellulase and protease (Fig. 5), which may contribute to the resistance of pepper blight. Among the different species of Bacillus, siderophores are known to be produced by B. anthracis, B. thuringiensis, B. cereus, B. velezensis, B. atrophaeus, B. mojavensis, B. licheniformis, B. pumilus, B. halodenitrificans, and B. subtilis[61]. Yuan et al.[62] have isolated B. velezensis SQR-7, SQR-101, and SQR-29, which can produce siderophores and protect tobacco plants from infection by Ralstonia solanacearum. However, there was no siderophore production by the H12 strain of B. velezensis (Figs 3, 5) in this study. Further experiments, such as whole genome sequencing, are needed for deeper analysis of the control mechanism of H12 and H23 strains against P. capsici.

-

In conclusion, two Bacillus strains showing a significant antagonist effect against P. capsici were identified as B. velezensis H12, and B. safensis H23. Both strains demonstrated strong control efficacy on pepper blight disease in greenhouse conditions. They exhibited bacteriolytic activity through the production of proteases and cellulases and induced the expression of PR1 and PR4 genes, which are associated with SA/JA signaling pathways. This study highlights the potential of these two strains as biocontrol agents and provides a valuable reference for their application in managing P. capsici-induced disease in pepper cultivation. Additionally, their eco-friendly nature aligns with the growing demand for sustainable and residue-free crop protection solutions.

This research was funded by Innovational Fund for Scientific and Technological Personnel of Hainan Province (Grant No. KJRC2023D08); The Start-up Scientific Research Foundation from Hainan University (Grant No. KYQD(ZR)-22124); and Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of School of Breeding and Multiplication, Hainan University (Grant No. NFCX2024-10). We are grateful to Prof. Qinghe Chen (School of Breeding and Multiplication (Sanya Institute of Breeding and Multiplication), Hainan University) who provided the Phytophthora capsici Leonian strain LT1354 pathogen. We thank Prof. Norvienyeku Justice (Plant Protection Department of School of Tropical Agriculture and Forestry, Hainan University) for his suggestions during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, funding acquisition: Fu H; methodology: Fu H, Gao L, Zeng C; software: Mushtaq N, Wang Z; validation, investigation, project administration, writing—original draft preparation: Fu H, Gao L; formal analysis: Fu H, Shu H; resources: Wang Z, Yu W; data curation: Gao L, Lu X; writing—review and editing: Fu H, Mushtaq N, Yu W, Cheng S; visualization: Zeng C, Gao L; supervision: Fu H, Lu X, Cheng S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The 16S rRNA sequencing data of H12 and H23 have been deposited in the NCBI cultured Prokaryotic 16S rRNA under Accession No. PQ443883–PQ443884.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

accompanies this paper at (https://www.maxapress.com/article/doi/10.48130/tp-0025-0030)

-

Received 1 July 2025; Accepted 3 October 2025; Published online 13 November 2025

-

Two bacterial isolates, H12 and H23, were identified as Bacillus velezensis and Bacillus safensis, respectively.

Both strains exhibit significant antagonistic activity against Phytophthora capsici.

Both strains significantly enhanced pepper blight disease resistance.

Both strains upregulated the expression of defense-related genes PR1 and PR4.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Huizhen Fu, Lianbao Gao

- Supplementary Table S1 The primers of 16S rRNA and gyrB genes using in this experiment.

- Supplementary Table S2 Primers of defense-related genes.

- Supplementary Table S3 Isolated strains from different pepper growth areas in Hainan province.

- Supplementary Table S4 Physical and Biochemical characteristics of strain H12 and H23.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Expression of PR1, PR2, PR4, PR10, and PIN-II in pepper at 1, 3, and 5 d after inoculation with Phytophthora capsici under H12 and H23 pre-treatment. Bars represent mean± standard error with three replications per treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test (p < 0.05).

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fu H, Gao L, Zeng C, Mushtaq N, Shu H, et al. 2025. Identification and biocontrol potential of two antagonistic Bacillus strains against Phytophthora capsici. Tropical Plants 4: e038 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0030

Identification and biocontrol potential of two antagonistic Bacillus strains against Phytophthora capsici

- Received: 01 July 2025

- Revised: 20 September 2025

- Accepted: 03 October 2025

- Published online: 13 November 2025

Abstract: Pepper blight caused by Phytophthora capsici L. is a devastating soil-borne disease in the pepper crop. Screening efficient antagonistic strains is one of the prerequisites for conducting research on the biological control of plant diseases. This study aimed to isolate Bacillus species against P. capsici. A total of 30 strains were isolated from three pepper-growing areas of Hainan province. Two strains, H12 and H23, exhibited significant antagonistic effects against P. capsici in the dual-culture assay with inhibition efficiency of 75.8% and 81.2%, respectively, and were selected as candidate biocontrol agents. Identification based on physiology and biochemistry charateristics, as well as 16S rRNA and gyrB genes, indicated that strain H12 belonged to Bacillus velezensis and was named Bacillus velezensis strain H12, whereas H23 was identified as Bacillus safensis, and named Bacillus safensis strain H23. Pot experiments showed that H12 and H23 provide potential resistance to pepper blight disease, reducing disease severity by 43.0% and 80.0%, respectively. Furthermore, strains H12 and H23 exhibited high hydrolytic cellulase and protease activities, which are associated with antagonistic activity against P. capsici. In addition, strains H12 and H23 induced PR1 and PR4 genes of pepper at 5 d post P. capsici inoculation, which is related to the salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway. In conclusion, Bacillus velezensis strain H12, and Bacillus safensis strain H23 may serve as potential biocontrol agents and provide a theoretical basis for preventing and controlling pepper diseases.

-

Key words:

- Pepper /

- Phytophthora capsici /

- Antagonistic effect /

- Bacillus /

- Identification