-

The increasing prevalence of myopia and high myopia has emerged as a significant public health concern in recent years. By 2050, individuals with myopia and high myopia will comprise approximately 49.8% and 9.8% of the global population, respectively[1]. Notably, east asian and southeast asian countries have experienced a rapid surge in myopia among children and teenagers[2−5]. High and ultra-high myopia are frequently accompanied by severe complications, such as retinal detachment, and myopic maculopathy[6,7]. Currently, three main surgical approaches are utilized to correct high myopia: corneal refractive surgery, posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, and refractive lens exchange. However, the feasibility of corneal refractive surgery is often restricted for most high myopia patients due to corneal thickness[7]. In contrast, posterior chamber IOL implantation offers advantages without involving the ablation of the cornea or removal of the natural lens[8]. Posterior chamber phakic IOL implantation includes several types, such as implantable collamer lens (ICL), Artisan/Artiflex Lens, Eyecryl posterior chamber phakic (IOL), and phakic refractive lens (PRL)[9]. The ICL is widely used in clinical practice, along with another available choice known as the PRL. However, limited studies on PRL show a high incidence of complications, including anterior subcapsular cataract, endothelial cell loss, and even dislocation of the PRL into the vitreous cavity[10−13].

Safer lens materials with fewer complications have become a pressing concern for individuals with ultra-high myopia. In response to this need, the Ejinn® phakic refractive lens (EPRL) was introduced as a posterior chamber IOL. The EPRL is composed of high-purity hydrophobic biological silica gel and features a central optical zone with a 6 mm radius. The EPRL exhibits several advantages. Firstly, its correctable diopter range spans from −10.00 D to −30.00 D, which is wider than the −0.50 D to −18.00 D range of ICL and the −3.00 D to −20.00 D range of PRL (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany). Secondly, the EPRL only requires a minimum anterior chamber depth (ACD) of ≥ 2.5 mm and a minimum white to white (WTW) measurement of ≥ 10.3 mm, making it more suitable for patients with the limitations in corneal thickness, diopter, ACD, or WTW. Hence, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of EPRL implantation, thereby contributing valuable clinical data for lens selection in EPRL implantation. This research holds immense importance for individuals with ultra-high myopia.

-

EPRL (Ejinn, Aijinglun Tech., Hangzhou, China) used in this study received approval from the China Food and Drug Administration in 2014 and is available in two types: the BK108 model (a long diameter of 10.8 mm) and the BK113 model (a long diameter of 11.3 mm). The absence of a central aperture in EPRL necessitates the performance of laser peripheral iridectomy at least one day prior to surgery to enhance the circulation of aqueous humor.

Study population and eligibility criteria

-

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (2023KYPJ336). Inclusion criteria of this study were: (1) Patients who underwent EPRL implantation at Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center between July 2021 and November 2022; (2) EPRL implantation performed by the same surgeon (Prof. Chun Zhang). Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with any other eye diseases that may affect the measurements of anterior segment parameters; (2) Patients with any surgical histories that may affect anterior segment parameters. All patients met the indications for EPRL implantation and had no contraindications for EPRL implantation. EPRL surgical indications: (1) a strong desire to remove glasses and reasonable expectations for surgery; (2) stable refractive power (annual diopter increase does not exceed 0.50 D) ≥ 1 year; (3) ACD ≥ 2.5 mm, corneal endothelial cell ≥ 2,000 mm−2, WTW ≥ 10.3 mm; (4) age ≥ 20 years old. Contraindications of EPRL implantation: (1) no psychological preparation for surgical risk, or psychological and mental diseases; (2) glaucoma, uveitis, untreated peripheral retinopathy, lens opacities, neuro-ophthalmic disorders, or systemic immune disorders; (3) history of previous intraocular surgery; (4) conditions associated with underlying zonular weakening (e.g., ocular trauma with zonular injury, Marfan syndrome, or other systemic disorders affecting cilia).

EPRL implantation

-

Laser peripheral iridectomy was performed at least one day before the EPRL implantation, resulting in two 0.5−1.0 mm incisions at the 11 o'clock and 1 o'clock positions. For EPRL implantation: (1) a 3.0 mm incision was made in the superior cornea, and a moderate viscoelastic surgical agent (1% sodium hyaluronate) was injected into the anterior chamber; (2) EPRL was implanted in the posterior chamber using an injector cartridge and correctly positioned; (3) the viscoelastic agent was completely removed by rinsing with a balanced salt solution.

Data collection and measurements

-

All patients underwent a comprehensive preoperative ophthalmic examination, including UDVA, CDVA, manifest refraction, intraocular pressure (NCT TX-20, Canon, Japan), WTW (manual), slit lamp examination, and fundoscopy. The corneal curvature of the flattest diameter (K1) and corneal steepest diameter curvature (K2) was obtained using an anterior segment analyzer (Pentacam AXL, Oculus; Wetzlar, Germany). The axial length was measured using a laser-assisted optical biometric instrument (IOL Master 700, Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Germany), the ECD was assessed using a specular microscope (CEM-530, NIDEK; Japan), and ACD was obtained via ASOCT (CASIA2, Tomey, Nagoya, Japan). The determination of EPRL sizes and diopters was carried out by experienced technicians based on the aforementioned parameters.

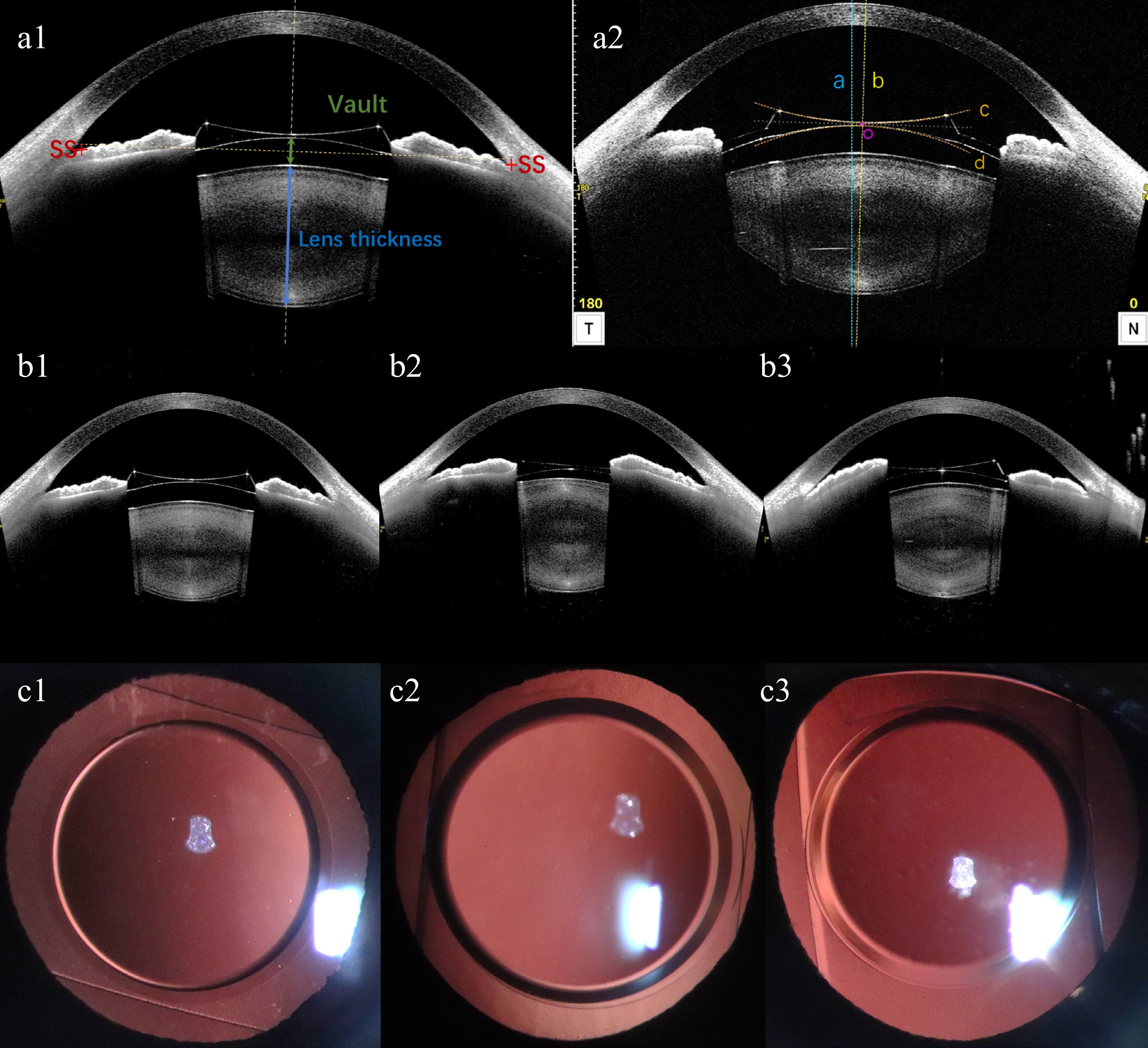

UDVA, CDVA, IOP, and ECD were assessed during the postoperative evaluation. The rotational position of the EPRL and the patency of both peripheral iris incisions were observed using the slit lamp backlighting technique and documented through anterior segment photography. The angle formed between the long axis of the EPRL and the horizontal axis was quantified. Anterior segment parameters including vault (the distance from the back surface of EPRL to the front surface of the natural crystalline lens), postoperative ACD, anterior chamber width (ACW), and lens thickness were measured using ASOCT (Fig. 1a1), and iris morphology was also observed. The horizontal and vertical decentration and tilt of EPRL were obtained using the Lens Analysis mode of CASIA2[14,15]. The front surface line and the back surface line of EPRL were manually adjusted. The central axis of the EPRL was defined as the line passing through the centers of the two circles formed by the front and back surface lines. The center point of the EPRL was identified as the midpoint of the intersections between the central axis and the front and back surfaces. The tilt of the EPRL was quantified by calculating the degree of rotation between the visual axis and the central axis of the EPRL. The decentration of the EPRL is quantified by calculating the vertical distance between the center point of the EPRL and the visual axis (Fig. 1a2).

Figure 1.

(a1), (a2) Schematic diagram of anterior segment parameters from CASIA2. (a1) Vault, postoperative ACD, ACW, and lens thickness measured by CASIA2. SS: scleral spur. ACW: anterior chamber width, the distance between the bilateral scleral spurs. Postoperative ACD: postoperative anterior chamber depth, distance from corneal endothelium to anterior surface of EPRL. Vault: green line with double arrowheads, distance from the back surface of EPRL to the front surface of natural crystalline lens. Lens thickness: blue line with double arrowheads, natural crystalline lens thickness. (a2) A representative image showing the location of EPRL in the eye from the manually corrected Lens Analysis mode of CASIA2. The horizontal and vertical decentration and tilt were the values on the 0- and the 90- degree-images. The blue dashed line (line a) represents the visual axis passing through the corneal vertex. The yellow dashed line (line b) represents the central axis of EPRL, which passing through the centers of the two circles formed by the manually corrected front surface line (line c) and back surface line (line d) of EPRL. The midpoint of the intersections between the central axis and the front and back surfaces of EPRL is the center point of EPRL (point o). The decentration of the EPRL is quantified by calculating the vertical distance between point o and the visual axis. The tilt of the EPRL were quantified by calculating the rotation degree between line a and b. (b1)−(b3) EPRL and iris morphology observed by CASIA2. (b1) EPRL is relatively centered, with bilateral iris symmetry. (b2) EPRL decenters to the right, with a higher position of the iris on the right side compared to the left. (b3) EPRL decenters to the left, with the iris on the left side positioned higher than the right. (c1)−(c3) Anterior segment photography with the slit lamp backlighting method was used to capture the position of EPRL rotation.

Statistical analysis

-

Variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. After confirming that the paired differences were normally distributed by the Shapiro–Wilk test with p-values exceeding 0.05, paired t-tests were used to compare SE, UDVA, CDVA, IOP, ACD, ECD, and AL before and after surgery. Using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach to account for inter-eye correlation, multiple linear regression analysis was performed using age, gender, EPRL model, EPRL diopter, lens thickness, postoperative ACD, and ACW as independent variables to evaluate the correlations with vault, decentration, and tilt of the EPRL, respectively. To account for multiple testing, two-sided p values were adjusted according to the method of Benjamini/Hochberg (B/H) to control the false discovery rate (FDR). In addition, the efficacy index (postoperative UDVA/preoperative CDVA) and safety index (postoperative CDVA/preoperative CDVA) were also analyzed. The statistical analysis was performed by SPSS version 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

-

Fifty-one eyes of 26 patients (male, 5; female, 21) were included in this study. Their mean age was 30.27 ± 7.76 years. The mean preoperative spherical equivalent was -19.09 ± 6.17 D. The average follow-up time was 9 months (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics of 26 patients with EPRL.

Characteristics Value Case (eyes) 51 Age (yrs) 30.27 ± 7.76 (range, 20−53) Gender Male 5 (10 eyes) Female 21 (41 eyes) Follow-up period (mos) 9.75 ± 6.88 (range, 0.25−20.00) EPRL diopter (D) −19.33 ± 5.08 (range, −28.00 to −10.00) EPRL model BK108 9 (18 eyes) BK113 17 (33 eyes) EPRL = Ejinn phakic refractive lens. Efficacy and safety

-

Comparison of preoperative and postoperative SE, UDVA, and CDVA showed significant statistical differences (p < 0.05). There were no significant statistical differences in postoperative IOP, ACD, and ECD compared with preoperative ones (p > 0.05) (Table 2). The endothelial cell density was 2976.82 ± 306.38 pre-operation, and 2854.43 ± 335.693 post-operation. The rate of endothelial cell loss was approximately 3.98% (p = 0.057). The efficacy index was 1.00 ± 0.51 and the safety index was 1.44 ± 0.45. The horizontal decentration of EPRL and the corresponding morphological changes in the iris were depicted (Fig. 1b1: EPRL is relatively centered, with bilateral iris symmetry. Fig. 1b2: EPRL decenters to the right, with a higher position of the iris on the right side compared to the left. Fig. 1b3: EPRL decenters to the left, with the iris on the left side positioned higher than the right). All implanted EPRLs exhibited vertical rotation (Fig. 1c1−c3), with 75% of them rotating more than 45°. Additionally, both peripheral iris incisions were not obstructed by the EPRL.

Table 2. Changes of preoperative and postoperative variables.

Preoperative variables (range) Postoperative variables (range) p-value SE (D) −19.09 ± 6.17

(−29.00 to −7.87)−1.00 ± 1.19

(−4.50 to 1.00)< 0.001* UDVA (logMAR) 0.04 ± 0.03; (0.01−0.12) 0.50 ± 0.23; (0.10−1.00) < 0.001* CDVA (logMAR) 0.55 ± 0.29; (0.15−1.00) 0.70 ± 0.26; (0.30−1.00) 0.006* IOP (mmHg) 15.28 ± 2.70; (9.7−20.1) 15.30 ± 2.59; (10.2−20.8) 0.964 ACD (mm) 2.81 ± 0.27; (2.45−3.40) 2.73 ± 0.26; (2.36−3.27) 0.096 ECD (cells/mm²) 2,976.82 ± 306.38; (2,301−3,642) 2,854.43 ± 335.693; (2,069−3,458) 0.057 AL (mm) 31.10 ± 3.09; (25.34−36.05) 31.20 ± 3.03; (25.94−36.19) 0.869 SE = spherical equivalent; UDVA = uncorrected distance visual acuity; CDVA = corrected distance visual acuity; IOP = intraocular pressure; ACD = anterior chamber depth; ECD = endothelial cell density; AL = axial length. The mean vault was 313.75 ± 217.29 μm. The findings of the multiple regression analysis, as presented in Table 3, indicated that a higher vault was associated with gender (male, β = 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16 to 0.84; p = 0.014), a larger diameter RPL model (BK113, β = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.87; p = 0.014), a lower RPL diopter (β = 0.39, 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.71; p = 0.032) and a thinner crystalline lens thickness (β = −0.40, 95% CI, −0.72 to −0.08; p = 0.023).

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis of postoperative vault.

Partial regression coefficient (B) Partial regression coefficient (β) (95% CI) p-value† Vault (μm) (R2 = 0.791, Adjust R2 = 0.739) Gender, Male 203.45 (64.76, 342.15) 0.51 (0.16, 0.84) 0.014* EPRL, BK113 193.02 (66.69, 342.15) 0.56 (0.18, 0.87) 0.014* EPRL diopter (D) 12.42 (1.18, 23.66) 0.39 (0.04, 0.71) 0.032* Lens thickness (mm) −220.34 (−359.14, −41.54) −0.40 (−0.72, −0.08) 0.023* Constant 779.460 EPRL = Ejinn phakic refractive lens; R2 = coefficient of determination; † False discovery rate adjusted p value. Risk factors for decentration and tilt of EPRL

-

The mean horizontal and vertical decentration of EPRL was 0.23 ± 0.17, and 0.19 ± 0.14, respectively. The mean horizontal and vertical tilt was 2.23 ± 1.59, and 1.81 ± 1.14, respectively. Among all eyes, 78.6% exhibited a horizontal tilt within 3.0°, while 89.3% displayed a vertical tilt within the same range. Furthermore, all eyes demonstrated tilts within 5.0° in both directions. In terms of horizontal decentration, 71.4% fell within 0.3 mm, 89.3% within 0.5 mm, and the maximum value was less than 0.7 mm. As for vertical decentration, 85.7% were within 0.3 mm, and the maximum value was less than 0.5 mm. The findings from the multiple regression analysis of the horizontal and vertical decentration and tilt of EPRL are presented in Table 4. The results indicated that a larger horizontal decentration of EPRL was associated with gender (male, β = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.72; p = 0.036), a smaller diameter RPL model (BK108, β = −0.35; 95% CI, −0.61 to −0.09; p = 0.036), a smaller postoperative ACD (β = −0.79; 95% CI, −1.41 to −0.17; p = 0.039), and a larger ACW (β = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.89; p = 0.036). No statistically significant linear correlations were observed between age, natural crystal thickness, and horizontal decentration. Similarly, no significant linear correlations were found between other factors and vertical decentration (p > 0.05). Furthermore, no significant linear correlations were identified between any factor and tilt (p > 0.05).

Table 4. Risk factors for EPRL tilt and decentration postoperatively.

Variables Horizontal Vertical Decentration (mm) Tilt (°) Decentration (mm) Tilt (°) β (95% CI) p-value† β (95% CI) p-value† β (95% CI) p-value β (95% CI) p-value† Age (year) 0.02 (−0.00, 0.03) 0.101 −0.07 (−0.25, 0.11) 0.560 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) 0.563 0.04 (−0.08, 0.16) 0.660 Gender, male 0.42 (0.12, 0.72) 0.036* 0.01 (−3.34, 3.36) 0.996 −0.21 (−0.44, 0.02) 0.297 −0.47 (−2.74, 1.80) 0.690 EPRL, BK108 −0.35 (−0.61, −0.09) 0.036* −2.07 (−4.93, 0.80) 0.560 −0.04 (−0.23, 0.16) 0.705 1.08 (−0.86, 3.02) 0.438 Postoperative ACD (mm) −0.79 (−1.41, −0.17) 0.039* 2.87 (−4.05, 9.79) 0.560 −0.11 (−0.58, 0.37) 0.705 −3.28 (−7.96, 1.41) 0.438 Lens thickness (mm) −0.36 (−0.81, 0.09) 0.138 2.00 (−3.02, 7.02) 0.560 −0.16 (−0.50, 0.18) 0.563 −2.99 (−6.39, 0.41) 0.438 ACW (mm) 0.52 (0.16, 0.89) 0.036* −1.56 (−5.63, 2.51) 0.560 0.32 (0.04, 0.59) 0.258 1.58 (−1.18, 4.33) 0.438 EPRL = Ejinn phakic refractive lens; ACD = anterior chamber depth; ACW = anterior chamber width; † False discovery rate adjusted p value. -

The rising prevalence of high myopia and advancements in science and technology have led to a growing demand for personalized surgical interventions. Previous research has indicated that PRL is an effective method for correcting high myopia and enhancing visual quality[13,16]. The unique material composition and hydrodynamic design of EPRL have significantly reduced the occurrence of surgical complications. This study provided evidence that EPRL implantation yielded favorable efficacy and safety outcomes with satisfactory biocompatibility. No significant complications, such as corneal endothelial decompensation, secondary cataract, and glaucoma, were observed in this short-term study. Nevertheless, the long-term impact of EPRL implantation requires further investigation.

To prevent contact with the natural crystalline lens, the optimal positioning of PRL haptics is floating above the zonular. Gonvers et al. have recommended that the vault of the posterior chamber IOL should surpass 90 μm[17]. The vault of 250~750 μm is considered as the long-term risks for secondary cataracts and corneal endothelial damage[16,18]. The mean vault in this study measured 313.75 ± 217.29 μm, with 54.9% of cases falling within the recommended range of 250~750 μm. The analysis of factors influencing vault changes suggests that the anterior surface of a thicker natural crystalline lens may be positioned more anteriorly, resulting in a smaller vault. The model and the diopter of PRL that are related to the vault are influenced by the dimensions of the PRL, the positioning of the PRL haptics, the curvature design of the PRL, and the contraction force of the ciliary muscle[13,19−21]. Schmidinger et al. have indicated that the vault decreases over 10 years after ICL implantation, but additional observations are required to determine if there is a sustained reduction in PRL vault[22]. Further research is necessary to accurately predict long-term outcomes and mitigate associated risk factors.

Our findings revealed that 54.9% of the eyes displayed bilateral iris asymmetry in the horizontal axis of the ASOCT image, with 92.9% exhibiting a greater temporal side of EPRL. This asymmetry could potentially be attributed to the temporal decentration of EPRL. It has been reported that the muscle strength of the bilateral ciliary body in primates is unequal, with a more pronounced contractile response on the temporal side during changes in lighting conditions and accommodation[23,24]. Niu et al. have demonstrated that 88.7% of ICLs exhibit a tilt towards the inferotemporal quadrant when subjected to intermediate lighting conditions[25]. In our study, a multivariate regression analysis revealed that a greater horizontal decentration was associated with males, a smaller diameter EPRL model (BK108, EPRL), a smaller postoperative ACD, and a larger ACW. Previous research on optimizing ICL implant size have consistently highlighted the significance of anterior chamber parameters, including ACD, ACW, and natural lens vault[25,26]. A study on healthy Chinese people shows that the ACW and anterior chamber area in female eyes is smaller than those in male eyes, potentially elucidating the influence of gender on the decentration of EPRL[27]. Furthermore, our study identified a negative correlation between postoperative ACD and decentration of EPRL. This finding could be attributed to the selection of diopter for varying axial lengths and the design of EPRL’s anterior surface curvature[28]. However, a comprehensive investigation into the precise mechanics governing the interaction between the EPRL surface and iris is further necessitated. The analysis of big data reveals that the mean diameter of the vertical sulcus-to-sulcus is greater than that of the horizontal counterparts, and the vertical ACW is larger than the horizontal ACW[29,30]. It is possible that asymmetrical iris compression force in the vertical direction occurs during pupillary constriction under certain conditions[25]. These factors may contribute to the observed vertical rotation and decentration of the EPRL in this study. Han et al. demonstrate that the vertical direction exhibits higher sensitivity and stronger correlation with ACD, suggesting the need for multidimensional evaluation of vault and lens position in future assessments[31]. Further investigation is necessary to establish a thorough understanding of the correlation between visual quality and lens position[32]. Additionally, our observations have revealed a minor occurrence of pigment deposition on some EPRLs, potentially resulting from the friction between the EPRL and the posterior surface of the iris during rotation and decentration[33,34]. The potential consequences of long-term friction, such as pigment deposition in the trabecular meshwork and subsequent development of secondary glaucoma, remain uncertain[34,35]. Given that young adults represent the main patient population for PRL implantation, it is essential to focus on selecting PRLs that offer greater long-term safety and stability through personalized assessment.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the retrospective design and small sample size necessitate the validation of our findings through a large longitudinal cohort study. Secondly, caution must be exercised when generalizing the conclusions of our study, as it solely involved patients from a single ophthalmic hospital in China. To enhance the broader applicability of the results, further exploration is warranted through a multicenter or multiethnic study.

-

In conclusion, this retrospective study demonstrated that the implantation of EPRL emerged as a viable and secure approach for correcting ultra-high myopia, with no significant short-term complications observed in this cohort. Moreover, the position of the postoperative EPRL was found to be significantly associated with gender, EPRL model, and anterior chamber parameters, suggesting the importance of individualized lens selection and careful preoperative evaluation of anterior segment anatomy in clinical practice. Our findings highlight the need for precise patient assessment to minimize postoperative decentration and tilt of EPRL, which could potentially impact long-term visual outcomes. Therefore, to optimize surgical efficacy and reduce complications, it is essential to strictly adhere to the selection criteria of patients and the EPRL model. However, to ascertain the long-term safety of EPRL implantation, explore the correlation between postoperative EPRL position and anterior chamber parameters, and develop more robust evaluation techniques, prospective studies with larger sample sizes and long-term follow-up periods are warranted.

-

The Ethics Committees of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (2023KYPJ336) approved this study. The research adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants reviewed and signed written informed consent forms.

We gratefully acknowledge all the patients for their participation, and staff from the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University for their contribution to this study. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81770971).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wu Y, Yi Y, Luo Y, Zhang C; data collection: Yi Y, Wu Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Wu Y, Yi Y, Wang A; draft manuscript preparation: Wu Y, Yi Y, Tao M, Zhou J, Qi T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Yue Wu, Yuhuan Yi

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published byMaximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This articleis an open access article distributed under Creative CommonsAttribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wu Y, Yi Y, Wang A, Tao M, Zhou J, et al. 2025. Efficacy and safety of posterior chamber Ejinn phakic refractive lens for ultra-high myopia. Visual Neuroscience 42: e007 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0006

Efficacy and safety of posterior chamber Ejinn phakic refractive lens for ultra-high myopia

- Received: 01 January 2025

- Revised: 12 April 2025

- Accepted: 15 April 2025

- Published online: 29 May 2025

Abstract: The aim of the present study was to investigate the efficacy and safety of posterior chamber Ejinn Phakic Refractive Lens (EPRL) for patients with ultra-high myopia. A total of 51 eyes from 26 patients with ultra-high myopia underwent EPRL implantation at Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (Guangzhou, China) between July 2021 and November 2022, were enrolled in this retrospective study. Uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA), corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA), refractive errors, anterior chamber depth (ACD), and corneal endothelial cell density were measured before and after surgery. The efficacy index (postoperative UDVA/ preoperative CDVA), safety index (postoperative CDVA/preoperative CDVA), and factors influencing postoperative vault, and EPRL position through anterior segment optical coherence tomography were analyzed. Inter-eye correlation was addressed using generalized estimating equation (GEE) models. Multiple linear regression analysis adjusted for age, gender, EPRL model, EPRL diopter, lens thickness, postoperative ACD, and anterior chamber width was used to evaluate factors associated with postoperative vault, decentration, and tilt of EPRL. The mean age of these 26 patients (five male and 21 female) who underwent EPRL implantation was 30.27 ± 7.76 years. The mean preoperative and postoperative UDVA was 0.04 ± 0.03 (0.01−0.12), and 0.50 ± 0.23 (0.10−1.00). The mean preoperative and postoperative CDVA was 0.55 ± 0.29 (0.15−1.00), and 0.70 ± 0.26 (0.30−1.00). UDVA and CDVA were higher than those before surgery (p < 0.05). The efficacy index was 1.00 ± 0.51 and the safety index was 1.44 ± 0.45. The endothelial cell density was 2976.82 ± 306.38 preoperationly, and 2854.43 ± 335.693 postoperationly. The rate of endothelial cell loss was 3.98% (p = 0.057). The mean vault was 313.75 ± 217.29 μm. Vault was related to gender (male, β = 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16 to 0.84; p = 0.014), larger diameter EPRL model (BK113, β = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.87; p = 0.014), and EPRL diopter (β = 0.39, 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.71; p = 0.032), and lens thickness (β = −0.40, 95% CI, −0.72 to −0.08; p = 0.023). EPRL horizontal decentration was related to gender (male, β = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.72; p = 0.036), smaller diameter EPRL model (BK108, β = −0.35; 95% CI, −0.61 to −0.09; p = 0.036), anterior chamber width (β = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.89; p = 0.036), and postoperative ACD (β = −0.79; 95% CI, −1.41 to −0.17; p = 0.039). Severe complications were not detected at a mean follow-up period of 9.75 ± 6.88 months. EPRL demonstrated effective correction of ultra-high myopia with relative safety in the short term. The postoperative position of EPRL exhibited a significant correlation with gender, EPRL model, and anterior chamber parameters.

-

Key words:

- Posterior chamber /

- Phakic refractive lens /

- Ultra-high myopia /

- Vault /

- Decentration