HTML

-

Rajasthan is the largest state of India covering 342, 239 square kilometers area with a wide range of ecological and environmental conditions. Most of the state is under arid and semi-arid conditions in the extremely hot Thar Desert of India. The temperature and weather conditions with very little rainfall are such that it is difficult to imagine growth of mushrooms. Yet, many fleshy fungi have been reported (Chouhan et al 2021, Chouhan & Panwar 2021b) and edible gasteromycetes grow luxuriantly after the scanty rains (Sharma et al. 2015).

The word gasteromycete means "stomach fungus" and these fungi produce their spores inside the fruiting body that are enclosed inside an outer covering called peridium. As a group, these fungi may all be referred to as gasteromycetes but close evolutionary relationships do not occur between the members. The diverse origin of the species is reflected in considerable variation in both the morphology and internal structure of the fruiting bodies. Some species have fruiting body with masses of homogenous tissue developing internal spore-producing tissues while others consist of empty cavities with the basidia lining the walls and yet in some species, the fruiting body may consist of basidia and hyphae or a gelatinous matrix enclosing the developing spores. Modern classification of fungi has placed them in Agaricomycetes (Hibbett & Thorn 2001, Hibbett et al. 2014) and many of fungi discussed herein have been placed in Boletales of which Scleroderma and Pisolithus are the typical examples. Despite the fact that the distinction between the Gasteromycetes and Agaricomycetes is no longer recognized as a natural one, the term gasteromycetes has been retained in the present communication because of the convenience in categorizing various forms of fruiting bodies.

Diversity of gasteromycetes have also been discussed in the first part of this paper where mycofloristic surveys reported the appearance of fungi in dry, desiccating environment of sand dunes in Thar desert of Rajasthan, India. Climatic conditions of Rajasthan with an average rainfall below 313 mm in Western Rajasthan, dry hot winds with summer temperature reaching 40 to 45 degrees Celsius, 55.5% average Relative humidity (RH) and extreme summers with desiccating conditions account for rare mushrooms and members of gasteromycetes and polypores fungi. The genera taxonomically described and reported from this region were Podaxis africana, Podaxis beringamensis, Podaxis saharianus, Phellorinia inquinans, Phellorinia herculeana var. strobilina, Montagnea haussknechtii and Tulostoma brumale (Chouhan & Panwar 2021b).

In the present communication, explorations in the South-western part of Rajasthan, particularly Mount Abu, revealed the occurrence of many gasteromycetes quite different from the Western Rajasthan as reported earlier (Chouhan & Panwar 2021b). Mount Abu possesses a characteristic vegetation due to the relatively high altitude coupled with the climatic and edaphic factors. It is considered as the richest spot of floral diversity in the whole of Rajasthan by Rajasthan State Biodiversity Board. According to Rajasthan Biodiversity Strategy & Action Plan, September 2002, the floral Diversity of this place includes sub- tropical evergreen forests with many species of oaks, pines and willows like Pinus roxburghii, Grewellia robusta and Salix spp. and other species like Boswellia serrata, Girardinia eylenica, Jasminum humile, Lannea coromandelica, Mangifera indica, Rosa brunoni, Sterculiz urens, Syzygium cumini etc. with several species of ferns and fern-allies also. The relatively high altitude coupled with the climatic and edaphic factors favours the endemic taxa of species like Bonnaya bracteoides, Dicliptera abuensis, Oldenlandia clausa, Strobilanthes hallbergii and Veronica anagallis var. bracteosa.Mount Abu was least explored for mushroom flora, hence, attempts made to find the diversity of fungi revealed the occurrence of many mushrooms and other fungi. (Chouhan et al. 2010, Chouhan & Panwar 2021a).

The objective of this study is to find out the diversity of gasteromycetes in Mount Abu which lies in South Western Rajasthan, where cool, humid climatic conditions with good average rainfall favouring luxuriant growth of mushrooms are prevalent. Intensive explorations for gasteromycetes were conducted and diverse fungi were collected, of which taxonomic descriptions of Scleroderma citrinum, S. bovista, Pisolithus arrhizus, P. albus, Bovista pusillas and B. limosa has been given herein.

-

During mycofloristic surveys of southern Rajasthan, some interesting gasteromycetes fungi were collected. The survey area mainly includes Mount Abu Wildlife Sanctuary of Sirohi districts Rajasthan in the south western part of Rajasthan This sanctuary comprises oldest Mountain range of Aravalli hills, and is spread over 288 km, located between 24°33' and 24°43' N latitude and 72°38' and 72°53' E longitude. Altitude ranges from 300 m to 1722 m from mean sea level. The climate of Mount Abu varies from the foot hills to high altitudes, being hot and dry at the base while pleasant and moderate at the top for the greater part of the year. The summer temperature of the sanctuary varies between 23 to 35℃ and in winter, between -2 to 25℃ with 150 cm average rainfall (Meena 2013). This region of Rajasthan exhibits great floral and faunal diversity along with a wide range of mushroom flora (Alam et al. 2014, Chouhan et al. 2010).

Mushrooms were collected from various localities of Mount Abu for two consecutive years in the months of July to August after rainfall. Field notes were prepared relating to various morphological characters like size, shape and colour of gasteromycetes fungi, with information on substrate of growth, climatic and soil characteristics. Ethanobotanical information and local uses were also noted along with date and time of collection. Field photography was done for all the mushrooms in their natural habitat (Atri et al. 2005). The fresh specimens were carefully dug out and cleaned gently with the help of a brush to remove any soil particles and litter. The fresh specimens were then placed in small cardboard boxes or paper bags after assigning them a specimen number and a label containing relevant information. Further, macroscopic and microscopic observations were made in the laboratory using identification keys and monographs. (Guzmán et al. 2013, Nouhra et al. 2012, Lebel et al. 2018, Lange 1987, Larsson et al. 2009). Macroscopic characters like size, shape, color and base of fruiting body for the presence and/ or absence of rhizomorphs, presence and/or absence of scales and their arrangement on the exoperidium, thickness of exoperidium and endoperidium, color of gleba and dehiscence of fruitbody were described by observing of fresh and dried material. Specimens were mostly found in large numbers varying from immature fresh specimens to mature, dehisced and dried in natural conditions, sometimes were air dried in indirect sunlight. Microscopic observations were made from sections of peridium and gleba mounted in 5% KOH and in lactophenol on glass slides from fresh samples but dried samples were used for other microscopic characters like spore measurements. Spore size was calculated as length range × width range (excluding ornamentation) based on 20 spores for each fruiting body. Terminology used to describe tissue types is as given by Korf 1973. All the collections have been deposited under JNV/Mycl in the Herbarium of Botany Department, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan (India). During the present investigation, authentic names of the investigated taxa are according to Mycobank (www.mycobank.org). Facesoffungi numbers were registered as per Jayasiri et al. (2015). All photographs are copyright of the author Reenu Chouhan and Charu Panwar.

-

Peridium composed of one prominent layer, sessile or carried at the apex of a pseudostem, dehiscing by irregular fissuring or by weathering of the apex. Gleba pulverulent at maturity, without a capillitium. According to Cunningham (1944), the two genera placed in the family may be separated by the following characteristics:

a. Gleba pulverulent at maturity …………………………………………………Genus Scleroderma

b. Gleba composed of persistent tramal plates enclosing glebal cavities filled with a powdery spore mass ………………………………………………………………………………Genus Pisolithus

Key to the species of Scleroderma

-

Large fruiting body, epigeal, 4–12cm in diameter. Basidiospores size 9–15μm in diameter, found on forest floor, mycorrhizal, temperate, subtropical or tropical species.

a. Exoperidium smooth to finely warty, whitish or yellowish-brown, bruising reddish brown to dark brown with minute dark scales. Spores globose, sometimes subglobose, 9.0–12.0 × 12.5–15.0 µm in diameter and prominently reticulated ………………………………………..Scleroderma bovista

b. Exoperidium thick, coarsely scaly, prominent scales in rosette in the apex or on the sides, yellowish to orange-yellowish. Spores 9.0–12.0 × 10.0–14.0 µm, globose and reticulate …………………………………………………………………………………Scleroderma citrinum

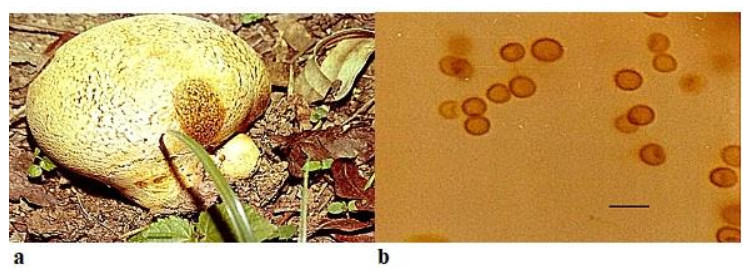

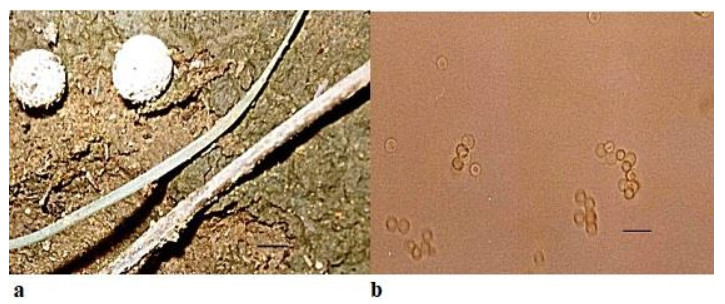

Scleroderma bovista Fr., Syst. Mycol. 3: 48, 1829. Fig. 1

Figure 1. a Fruitbody of Scleroderma Bovista growing on humus rich soil near trees. b Spores. Scale bar: a = 1 cm, b = 20 µm.

Faces of Fungi number: FoF 09754; MycoBank number: MB 186199

Synonyms: Scleroderma verrucosum var. bovista (Fr.) Sebek, Sydowia 7 (1-4): 177 (1953)

Scleroderma verrucosum subsp. bovista (Fr.) Sebek, Sydowia 7 (1-4): 177 (1953) Scleroderma vulgare var. macrorrhizon Fr., Syst. Mycol.3: 47, 1829.

Scleroderma macrorrhizon Wallr., Fl. Crypt. Germ., Nürnberg 2: 404, 1833

Fruitbody up to 6–12 cm in diameter, globose, white to yellowish-brown, scaly, contracting into a short stem-like rooting base which is attached to the substratum by forming rhizomorphs. Peridium smooth, white to pale yellowish-brown, scaly or finely cracked near the top, scales thick, irregular, minute, dark in color in comparison to rest of the surface of peridium, or sometimes entire surface is cracked, rubbery when immature, fragile when dry, bruising reddish brown to dark brown and dehiscing by irregular breaking of the apical portion Peridium has thin- walled hyaline hyphae in the outer layer but inner layer consists of cylindrical, thick-walled, hyphae up to 6 µm diameter. Gleba white at first, later turns to olive, umber or dark reddish-brown and possess yellow filaments. Spores globose, sometimes subglobose, 9.0–12.0 × 12.5–16.0 µm in diameter and uniformly reticulated.

Ecology and Distribution – Scleroderma bovista has been reported to be epigeous or sub-hypogeous in forest litter and organic soil, growing under Pinus radiata, Cedrus sp. and Quercus sp. by Nouhra et al. 2012 from Argentina, Brazil (Gurgel et al. 2008, Montagner et al. 2015) and from Nepal (Guzmán & Ramírez-Guillén 2010). From India, it has been reported by Natrajan & Kannan (1979) from South India and Anand & Chowdhry (2013) from Jammu and Kashmir. In the present study, it has been found widespread on the forest floor growing on humicolous soil amongst leaf litter and ectomyorrhizal with trees of subtropical evergreen type with species of Eucalyptus, Pinus roxburghii and Grewellia robusta. It favors moist soil with calcareous, alkaline nature and a humid weather with temperature ranging from 24-28 degree Celsius.

Specimens examined – JNV/Mycl/116on humus rich soil by Charu Panwar, 24°53'18.17"N72°50'52.58"E Sirohi, elevation: 321 m (1, 053 ft), Mount Abu 72.7083°E 24.5925°N, Arbuda Devi temple 24.60107°N72.71217°E.

Note – Nouhra et al. (2012) describes S. bovista from Argentina with a diameter 2–7 cm, two-layered peridiumof thickness 900–1400 µm which bruises reddish brown, inner layer consisting of cylindrical, thick-walled hyphae up to 6 µm diameter, reticulate spores with spines. This study has been used as the reference for the description of above-mentioned species. The present findings indicate that the material studied herein is similar in all respects to the material examined by Nouhra et al. (2012) except in the size of fruiting body which is 6 – 12cm, although smaller sized fruiting bodies with 4–7 cm diameter were more common in the present surveys.

Scleroderma bovista is related with S. macrorrhizon (Guzmán 1970) in having a long lacunose pseudo stipe. S. vulgare var. macrorrhizon was described as S. bovista with pseudo stipe by Demoulin & Malençon (1970). In Indian sub-continent, S. macrorrhizon has been reported from West Bengal by Pradhan et al. 2011.

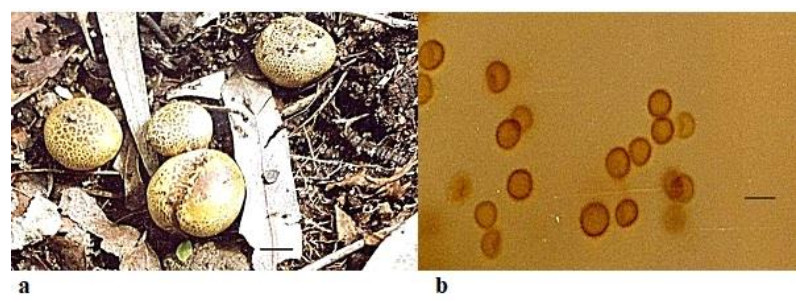

Scleroderma citrinum Pers., Syn. Meth. Fung. 1: 153(1801) Fig. 2

Figure 2. a Fruitbodies of Scleroderma citrinum growing on humus rich soil. b Spores. Scale bar: a = 5 cm, b = 20 µm.

Faces of Fungi number: FoF 09755; MycoBank number: MB 181865

Synonyms: Lycoperdon tessellatum Schumach., Enumeratio Plantarum, in Partibus Sællandiae. Septentrionalis et Orientalis Crescentium 2: 191 (1803). Scleroderma vulgare Hornem. Flora Danica: (1829) Vulgar.

Fruitbody 4–10 cm in diameter, globose or flattened, surface yellowish to yellow-brown covered with prominent, separated scales which are often darker in color and arranged in rosette manner on the upper part of the fruiting body and having a compact mycelia base. Peridium thick 2.0–4.0mm, hard and scaly, yellowish-brown in color and differentiated into endo and exoperidium. Endoperidium whitish to yellowish in color. Gleba thick and white at first, at maturity it becomes purple to purple-black from the center to the periphery, finally it becomes blackish to brownish, compact and later dusty. It consists of thin brown hyphae to thick hyphae of 7.0–8.0 µm from periphery to center and innermost part having comparatively thin -walled hyaline hyphae with 4.0–5.0 µm. Dehiscence takes place through an irregular breaking of the apical portion. Spores9.0–12.0 × 10.0–14.0 µm, globose and reticulate.

Ecology and distribution – Scleroderma citrinum are a common gasteromycete fungus and widespread in North America, Central Europe, Asia, Africa, South America (Guzmán 1970, Sulzbacher et al. 2013) and Brazil (Gurgel et al. 2008, Montagner et al. 2015), Mexico (Guzmán et al. 2013) and Argentina (Nouhra et al. 2012).

Presently, it has been reported from Mount Abu, Sirohi district of Rajasthan and was found growing alone, scattered, or gregarious, widespread after rainfall and is ectomycorrhizal with gymnosperm trees like Pinus roxburghii and Grewellia robusta.

Specimens Examined – JNV/Mycl/ 117/2018, by Reenu Chouhan, 24°53'18.17"N72°50'52.58"E Sirohi, elevation: 321 m (1, 053 ft), Mount Abu 72.7083°E 24.5925°N Toad rock area.

Note – The specimens described here is. S. citrinum. A distinct yellow color and concentric arrangement of scales on the fruiting bodies are the most striking and distinctive characters to recognize the specimens in the wild. Certain characteristics like the prominent spines and reticulum on the spore wall of S. bovista, rhizomorphs aggregated at the base to form a short pseudo stipe, color of peridium and its bruising reddish brown to dark brown, thickness of peridium 900–1400 µm thick(Nouhra et al. 2012) are distinguishing characters which separate S. bovista from S. citrinum which has abundant scales on the fruiting body, a rarely developing pseudostipe, peridium comparatively thinner, measuring 2000–3000 µm (Nouhra et al. 2012) and with less prominent reticulations on the spore wall. Guzmán et al. (2013) reviewed the genus Scleroderma.

Taxonomic description of S. citrinum has been reported for the first time from Rajasthan.

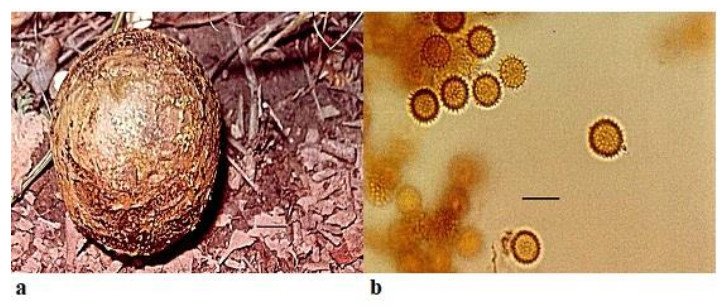

Pisolithus arrhizus (Scop.) Rauschert Zeitschrift für Pilzkunde 25 (2): 50 (1959) Fig. 3

Figure 3. a Fruitbody of Pisolithus arrhizus growing on humus rich soil. b Spores. Scale bar: a = 1 cm, b = 20 µm.

Faces of Fungi number: FoF 09756; MycoBank number: MB 303705

Synonyms: Lycoperdon arhizum Scop. Delic. Fl. Faun. Insubr.: 40 (1786) Lycoperdon arhizon Scop. (1786) Scleroderma arrhizum (Scop.) Pers., Synopsis methodica fungorum: 152 (1801) Scleroderma arhizum (Scop.) Pers., Synopsis methodica fungorum: 152 (1801). Pisocarpium arhizum (Scop.) Link, Mag. der. Ges. Natur. Freun.Berlin 8: 44 (1816). Lycoperdodes arrhizon (Scop.) Kuntze, Revisio generum plantarum 3 (2) (1891). Lycoperdon capitatum J.F. Gmel., Systema Naturae 2 (2): 1463 (1792)

Fruitbody is variable in shape and size, pyriform to ovoid or sub-globose, from 3– 18 cm × 10–12 cm diameter and usually with a stout rooting base. Peridium is smooth at first, shining, pallid white or ochraceous, with umber to fuscous black markings in a snake-skin effect, later becomes brown or black and finally breaking away irregularly from the apex to expose the mature spores. Gleba is divided into polygonal or lenticular peridioles, which are larger above and peripherally, unequal in size and shape, firm but brittle, separated by thick, carbonous, persistent tramal plates. Young peridioles are composed of a network of septate, branched, hyaline to yellowish brown hyphae 3.8–4.5 µm. Peridioles are occupied by the pulverulent spore mass which are ochraceous to umber and sometimes purple. Spores7.1–11.0 × 9.0–12.0 µmin diameter, globose and with densely packed spines. Basidia and cystidia were not observed.

Ecology and Distribution – Pisolithus arrhizus has been reported to be epigeous and widespread in forest litter and organic soil, growing under Pinus radiata, P. elliottii, Cedrus sp., Quercus sp. and Betula sp., widely distributed globally and forming ectomycorrhizal associations with a broad range of woody plants in Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia (Leonard et al. 2013, Martin et al. 2002, Moyersoen et al. 2003). Lebel et al. (2018) reported Pisolithus species from unusual habitats like in geothermally active areas and in a broad range of habitats in association with Eucalyptus or Acacia species from Australasia. In the present study, Pisolithusarrhizusis occurring as a widespread genus in forest litter and ectomycorrhizal with Eucalyptus trees in the areas under survey.

Specimens examined – JNV/Mycl/115 by Reenu Chouhan, 24°53'18.17"N72°50'52.58"E Sirohi, elevation: 321 m (1, 053 ft). Mount Abu72.7083°E 24.5925°N, Sunset Point, 24.5995° N 72.6978° E elevation: 1108mGurushikhar area 24.6653° N, 72.7819° E, elevation: 1722 m.

Note – The specimens described here is Pisolithus arrhizus. The fruiting bodies of P. arrhizus examined during the present investigation vary widely in size, shape and general appearance but bear close resemblance to P. tinctorius (= P. arrhizus) with respect to morphological characters as described by Bottomley (1948), Vander Westhuizen & Eicker (1989). According to Natrajan et al. (1988), P. arrhizus (= P. tinctorius) reported from Tamil Nadu is widespread in India. It has also been reported from West Bengal, India by Pradhan et al. (2011).

The taxonomic position of Pisolithus has been debated upon by many researchers and epithet "tinctorius" has been widely used. Many different species are being placed in synonymy. Taxa within the genus Pisolithus have been regarded as conspecific and grouped as P. tinctorius by Chambers & Cairney (1999). Basidiome morphology has been important in Pisolithus taxonomy as discussed by Watling et al. (1995), Diez et al. (2001), Kanchanaprayudh et al. (2003) and Thomas et al. (2003). A new taxonomic arrangement for the genus based on Australian specimens was proposed by Anderson et al. (2001). Many species including P. albus, wrongly attributed to P. arrhizus, have now been separated.

Pisolithus albus (Cooke & Massee) Priest, Fungi of Southern Australia: 122(1998) Fig. 4

Figure 4. a Fruitbodies of Pisolithus albus growing on humus rich soil near trees. b Spores. Scale bar: a = 1 cm, b = 20 µm.

Faces of Fungi number: FoF 09757; MycoBank number: MB 296564

Synonyms: Polysaccum album Cooke & Massee, Grevillea 20: 36 (1891). Pisolithus albus (Cooke & Massee) Priest, Phytotaxa 348 (3): 167 (2018)

Fruitbody is dull-white, irregular in shape, lobed, subglobose, pyriform, 5–21 cm in diameter, with deep rooted base. Stipe concolorous, up to 25 mm wide, solid. Peridium moderately thick to thin, smooth, dry, white to cream in mature fruiting bodies. Gleba developing within distinct peridioles is 1.0–3.5 mm long, periodioles are covered by thin dry, ochraceous membrane, possessing dark brown or black mass. The peridioles are smaller and compact towards the base. Later, gleba transforms into a powdery mass. Spores bright yellowish brown, 9.0–10.0 × 9.5–10.0 µm, globose, densely verrucose, spiny with erect or slightly curved spines of 1 µm.

Ecology and Distribution – Pisolithus albus has worldwide distribution and has been reported from Italy (Gargano et al. 2018), Tunisia (Jaouani et al. 2015) and Australasia by Lebel et al. 2018. They form an ectomycorrhizal association with a variety of angiosperms and gymnosperms. P. albus is reported as an ectomycorrhizal fungus with Eucalyptus camaldulensis by Ducousso et al. 2012, with Acacia auriculiformis by Dutta & Acharya (2014) and have also been used in forestry inoculation programs where increased growth was reported for species of Eucalyptus, Pinus and Acacia (Marx et al. 1977, Garbaye et al. 1988, Duponnois & Ba 1999).

Singla et al. (2004) surveyed various States of India including Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Orissa, Haryana, Punjab, Uttaranchal, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir but has not included Rajasthan in the research. During the present study, P. albus is found occurring as a widespread fungus in the survey areas of Rajasthan.

Specimens examined – JNV/Mycl/114by Reenu Chouhan, 24°53'18.17"N72°50'52.58"E Sirohi, elevation: 321 m (1, 053 ft), Mount Abu 72.7083°E 24.5925°N, Sunset Point, 24.5995° N 72.6978° E elevation: 1108m.

Note – In Indian scenario, studies on genetic variability of Pisolithus by Singla et al. (2004) undoubtedly provide a better understanding of Indian specimens but reports all Indian specimens as P. albus which contradicts reports of Natrajan et al. (1988) who reported P. arrhizus (= P. tinctorius) as widespread genera in India. The study of Singla et al. (2004) is limited to south western and Northern parts of India but explorations have not been conducted in Western India including Rajasthan which possess innumerable species owing their genetic variability to the arid and semi-arid conditions. The region under study shares the flora of western arid and semiarid zones and eastern zone which is geographically a humid belt of Rajasthan.

Taxonomic description provided for P. albus in the present communication agrees in all respect viz. dimensions of fruiting body, stipe and basidiospores to that of material found in Italy (Gargano et al. 2018) but slightly smaller than reported from Tunisia (Jaouani et al. 2015). Mycofloristic explorations conducted herein revealed that species of Pisolithus found in Rajasthan belong to two different taxa. Therefore, in complete agreement with Natrajan et al. (1988) and Anderson (2001), the specimens currently studied and found in the Rajasthan, India are two separate taxa, P. arrhizus and P. albus.

Notable, P. arrhizus (= P. tinctorius) and P. albus found in Rajasthan, India are new reports to the area as well.

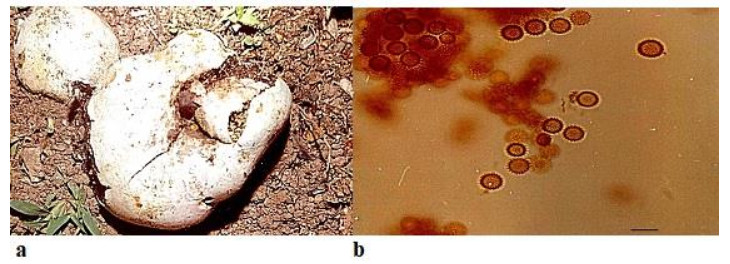

Bovista pusilla (Batsch) Pers., Synopsis methodica fungorum 138 (1801) Fig. 5

Figure 5. a Fruitbodies of Bovista pusilla growing on humus rich soil near trees. b Spores. Scale bar: a = 10 cm, b = 25 µm.

Faces of Fungi number: FoF 09758; MycoBank number: MB 209390

Basionym: Lycoperdon pusillum Batsch, Elenchus fungorum. Continuatio secunda: 123, t. 41:228 (1789)

Synonyms: Bovistella pusilla (Batsch) Lloyd, Mycological Writings 3 (34): 457 (1910)

Pseudolycoperdon pusillum (Batsch) Velen., Novitates mycologicae novissimae: 93 (1947)

Lycoperdon polymorphum var. pusillum (Batsch) F. Smarda, Studia Botanica Čechoslovaca 12: 238 (1951)

Globaria pusilla (Batsch) Quél., Mémoires de la Société d'Émulation de Montbéliard 5: 371 (1873)

Fruitbody small white or brownish fruitbody attached to the surface by mycelial threads found solitary or in scattered troops in grasslands. Sub- spherical opening by a raised conical apical pore wrinkled below and attached by greyish- brown mycelial cords. Peridium differentiated into exoperidium and endoperidium. Exoperidium white becoming tan brown, at first smooth soon coarsely flaking and splitting into distinct patches falling away into flakes at maturity to reveal greyish-brown papery endoperidium. Septate, consists of thin-walled hyphae of diameter 2.0–3.5 µm. Gleba at first white and firm, soon becoming olivaceous brown, powdery. Capillitium threads in the center of gleba lack septa. Spores brown, minutely warty, spherical, 2.0–2.1×3.0–3.1 µm. Basidiafour spored, cystidia absent.

Ecology and Distribution – This species has been reported from open grasslandsthe cold desert of Ladakh, India by Dorjey 2019, from Greenland by Lange (1987), Wales by Pegler et al. (1995) and Italy by Sarasini (2005). In the present communication, it has been reported to be growing on humus rich soil near trees.

Specimens examined – JNV/Mycl/113by Reenu Chouhan, 24°53'18.17"N72°50'52.58"E Sirohi, elevation: 321 m (1, 053 ft), Mount Abu72.7083°E 24.5925°N, Sunset Point, 24.5995° N 72.6978° E elevation: 1108m.

Note – Bovista pusilla is characterized by apical stoma which is lobed with recurving edges, and is not surrounded by a delimited peristome. Mature gleba is dark brown and absence of delimited peristome or a peristomial depression but instead, having slightly irregular stoma demarcates this species from B. limosa as is supported by studies of Larsson et al. 2009.

Bovista limosa Rostr., Meddelelser om Grønland 18: 52 (1894)Facesoffungi number: FoF 05268Fig. 6

Figure 6. a Fruitbodies of Bovista limosa growing on calcareous soil. b Spores. Scale bar: a = 10 cm, b = 25µm.

Faces of Fungi number: FoF 09759; MycoBank number: MB 212654

Synonyms: Lycoperdon limosum (Rostr.) Rauschert, Zeitschrift für Pilzkunde 25 (2): 52 (1959)

Fruitbody very small in comparison to Bovista pusilla, 3.0–5.0 length × 6.0–10.0mm breadth, small, white or brownish, sub-spherical with isolated warts on surface, attached to the surface by mycelial threads found solitary or in scattered troops on soil. Peridium differentiated into exoperidium and endoperidium. Exoperidium possessing whitish-yellowish flocculae. Gleba at first white and firm, soon becoming olivaceous brown, powdery. Capillitium is heteromorphic with long hyphae less frequent septa in the outer portion but in the inner portion hyphae are up to 9 µm in diameter with septa in the capillitium threads. Spores light brown, ornamented, spherical, 1.5– 2.0×2.1–2.5µm. Basidia four spored, cystidia absent. Presence of a fimbriate peristome for the dehiscence of spores.

Ecology and Distribution – Bovista limosa has been reported from Greenland by Lange (1987), Wales by Pegler et al. (1995), Italy by Sarasini (2005) and Germany by Runge & Gröger (1990). It has been found growing on soil amongst grasses and amongst litter. In the present communication, it has been found to be growing on calcareous soil.

Specimens examined – JNV/Mycl/118by Charu Panwar, 24°53'18.17"N72°50' 52.58"E Sirohi, elevation: 321 m (1, 053 ft), Mount Abu72.7083°E 24.5925°N, Sunset Point, 24.5995° N 72.6978° E elevation: 1108m.

Note – Bovista pusilla and B. limosa are of common occurrence on humus rich soil and calcareous soil respectively after good monsoon rains. These minute gasteromycetes fungi are lesser known. There is a slight difference in the average dimensions viz. size of the fruiting bodies of the two species and B.limosa is the smaller than B. pusilla. The spore morphology of both the species is more or less similar with respect to size and ornamentation. B. limosa was confused with the South American species B. echinella (syn. Bovistella echinella) for several years but Larsson & Jeppson (2008) resolved it to present species on the basis of molecular studies. Later, Larsson et al. (2009) described the taxonomy, ecology and phylogenetic relationships of the species from North Europe while discriminating the morphological characters between Bovista limosa and B. pusilla on the basis of size of fruiting bodies, nature of exoperidium, fimbriate or non- fimbriate peristome, spore pedicel and capillitium. The above-mentioned differences, specially the size of spores, fimbriate peristome opening and heteromorphic capillitium were also noted in the specimens of B. limosa distinguishing it from B. pusilla, in the present study.

Ethanobotanical studies

-

During the present surveys, the information collected for Scleroderma spp. and Pisolithus spp. revealed that they are used as wound healers by local tribals namely Garasia tribe of Mount Abu and Sirohi from India, as also reported from Mexico by Guzmán et al. (2013). P. arrhizus has been reported to give relief from burning, itching and for healing minor skin infections when used with coconut oil (Dutta & Acharya 2014). S. citrinum has been reported to be edible (Joshi & Joshi 1999) and good source of vitamins, proteins and carbohydrates (Joshi et al. 1996) but according to Coccia et al. 1990, S. citrinum is poisonous.

Taxonomic study

Family Sclerodermataceae

-

Gasteromycetes fungi found in Rajasthan are greatly diverse species, adapted to tolerate extreme conditions as well as humid, are successful colonizers of the desert ecosystems through attainment of maximum reproductive potential (Chouhan & Panwar 2021b), ectomycorrhizal, yet very diversified from the mycoflora of the rest of the country. Diversity of habitats, substrates of growth and ectomycorrhizal associations have led to a plethora of distinctive fungal lifestyles in the region under study. None of the gasteromycetes adapted to and thriving in the desert of Western Rajasthan like Podaxis africana, Podaxis beringamensis, Podaxis saharianus, Phellorinia inquinans, Phellorinia herculeana var. strobilina, Montagnea haussknechtii and Tulostoma brumale (Chouhan & Panwar 2021b) were found in the Mount Abu, region which is located in south western part of Rajasthan. This clearly indicates diversity and distribution of these species in relation to their climatic and topographical variations. Despite the diversity in lifestyle patterns, a general conclusion can be discerned that the gasteromycetes fungi found in Rajasthan share the mycoflora of western arid and semi-arid regions of the world with southern region particularly Mount Abu of Sirohi district, which is comparatively a humid belt of Rajasthan possessing some different species from its arid Western part.

Mushrooms exhibit a wide range of morphological variability (Halbwachs et al. 2016). Changes in climate and environmental conditions of a place markedly influence their morphological and anatomical characteristics leading to variations which are sufficient to report them as new genera and species. Attempts have been made to study the diverse mycoflora of the Mount Abu of Sirohi district in South-western Part of Rajasthan, India. This communication reveals new insights into the six species of gasteromycetes found here, of which Scleroderma citrinum, S. bovista, Pisolithus arrhizus, P. albus, Bovista pusilla and B. limosa have been described herein.

Studies on these gasteromycetes support this statement and reports new findings. Scleroderma citrinum is widespread but S. bovista has been reported from the first time from this region (Doshi & Sharma 1997). Bovista pusilla and B. limosa have also been described taxonomically and have been reported for the first time from this region. Taxonomic studies based on morphological characterization of Pisolithus provides a better understanding of this fact that the species, P. arrhizus reported synonymous to P. albus (Singla et al. 2004), are actually two different species, as also reported by Natrajan et al. (1988) and forms the significant outcome of this research.

-

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

- The authors thank Dr. Swarnjeet Kaur for her consistent guidance and support.

- Copyright: © 2021 by the author(s). This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| R Chouhan, C Panwar. 2021. Diversity of Gasteromycetes in Rajasthan, India-Ⅱ. Studies in Fungi 6(1):352−364 doi: 10.5943/sif/6/1/26 |