-

Professor Tsukase Susumu (塚瀬進, born 1962) currently teaches in the Faculty of Environment and Tourism at Nagano University in Japan (長野大学, 環境ツーリズム学部). He is interested in understanding the lives of ordinary people. In particular, examining differences between the peoples of China and Japan. He strives to present an 'on-the-ground' view of how the people from these two cultures have perceived and interacted with each other during recent history.

He has so far published four books which examine aspects of this larger topic:

* Research on the Modern Economy of Northeast China『中国近代東北経済史研究』Chūgoku kindai Tōhoku keizaishi kenyū (Tokyo: Tōhō Shoten 東方書店, 1993)

* Manchukuo: The Reality of Ethnic Harmony『満洲国: 民族協和の実像』Manshūkoku: Minzoku kyowa no jistuzō (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan 吉川弘文館, 1998)

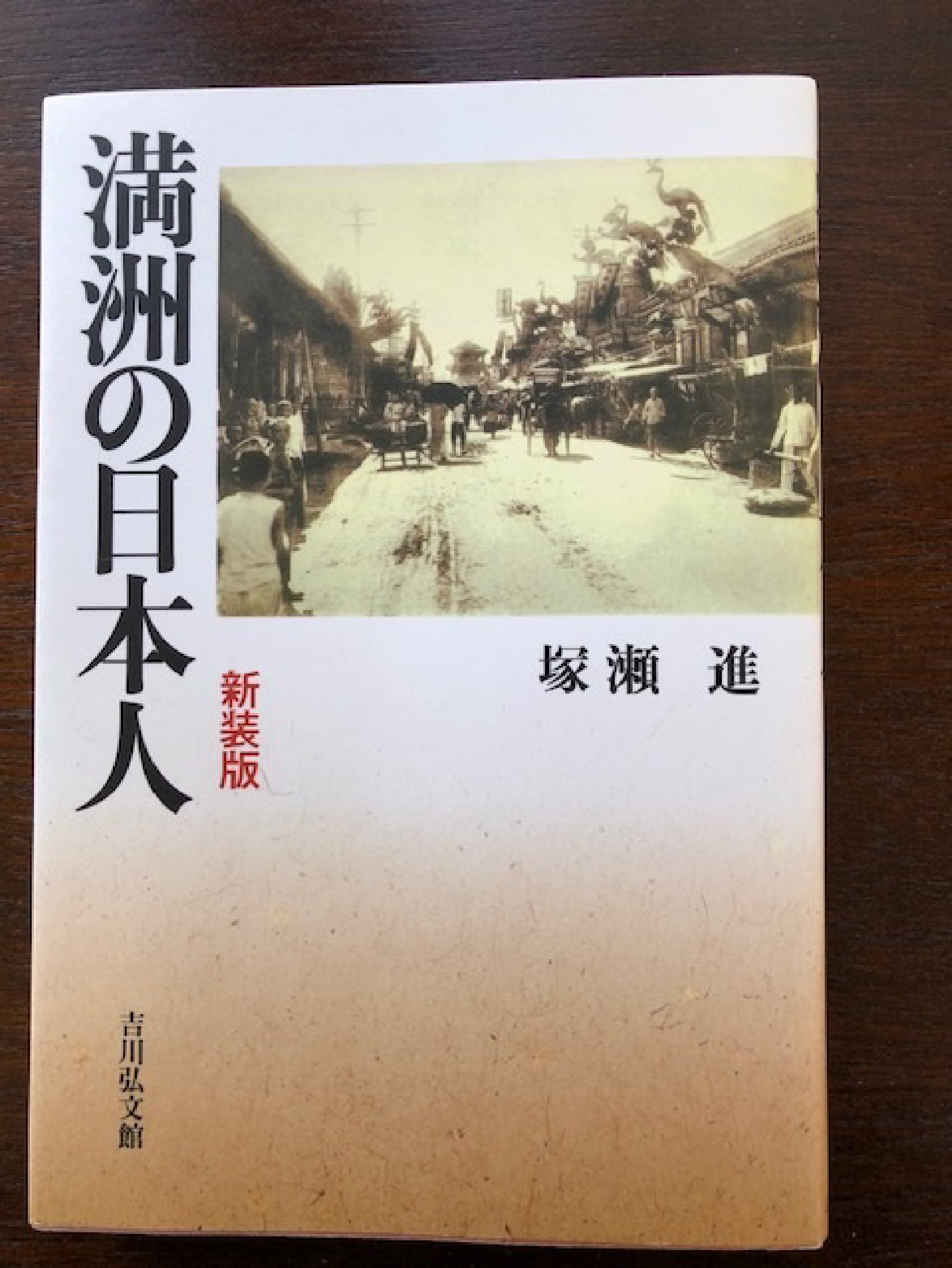

* The Japanese in Manchuria 『満洲の日本人』 Manshū no Nihonjin (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan吉川弘文館, 2004, reissued 2023)

* Research on Manchuria; Manchuria; Six Hundred Years of Change 『マンチュリヤ史研究-満洲: 600年の社会変容』, Manchuriyashi kenkyū – Manshū: roppyakunen no shakai henyō (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan吉川弘文館, 2014)

In 2023 his publisher the Yoshikawa Kōbunkan reissued his 2004 title, The Japanese in Manchuria 『満洲の日本人』 Manshū no Nihonjin (Fig. 1). I wondered why the publisher would decide to re-launch this book 19 years after its initial publication? The book cover announces: New Edition (Shinseiban 新裝版), but actually it seems no new information has been added to the earlier edition. The only new writing is in the seven-page Epilogue (Shinsei fukukan ni atte 新製復刊あたって) added by the author, pp 239−245. In this Epilogue, Tsukase reviews some of the main points he made in the original work and he cites several Japanese language studies published since his 2004 study that accept and reinforce the points he made in his original study.

My conclusion is that one reason his publisher re-issued the book was because books about the Japanese experience with Manchuria is a topic that still sells well in Japan. That experiment with Manchuria began in 1905 when Japan was granted territorial concession rights in the southern-most part of Manchuria. Japan defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904−1905, and the Russian treaty rights in south Manchuria were transferred to Japan. From the Treaty Port city of Dalian, Japan also received the rights to a rail line that stretched 392 miles (631 km) northward to the city of Changchun. Japanese communities sprang up all along that rail line, christened by the Japanese as the South Manchuria Railroad (南滿洲鐵道). In 1931 Japanese troops invaded all of Manchuria, where in 1932 they set up the new country of Manchukuo (滿洲國). In their new country, they began to institute modern city planning, transportation networks, and factories for heavy industry. It was a puppet country, ostensibly independent and only assisted by Japan, but in reality, it was ruled by the Japanese military with an iron fist. That experiment collapsed in 1945 when Japan surrendered, almost 80 years ago.

For a variety of reasons, the Japanese continue to be fascinated with those years of Japanese involvement in Manchuria. When I travel to Tokyo, for example, I usually visit the large Kinokuniya Book Store on the East Side of Shujuku Station (新宿東口の紀伊国屋書店). In the bookstore in the section on Social Sciences dealing with Modern History, there is always a special section devoted to books about Manchuria. In 2023 when I bought my copy of Tsukase's re-issued book, the display space consisted of two cabinets, 6 ft (183 cm) high and 2 ft (61 cm) wide devoted entirely to titles on this topic. Every year Japan publishes a small mountain of books about Manchukuo, including picture books, memoirs, and historical/academic studies such as Tsukase's book. In 2023 the sales of books in Japan came to 619.4 billion yen (319.83 billion USD). Those were not all mass-market books, and the portion of Manchuria-related books was surely smaller, but judging from their visibility in the bookstores, I conclude that books about Manchukuo are placed in the category of 'mass market' publications, and this particular topic is a well-defined sub-category of perpetually popular mass market titles. In presenting the topic of Manchuria to the general public, the Japanese Internet describes, that at one time Manchuria was seriously considered as 'Japan's lifeline' Nihon no 'seimeisen'. 日本の 「生命線」. Tsukase's publisher re-issued the book because they knew it would sell.

This publisher has been re-issuing many of their titles dealing with Manchuria, underscoring their confidence in sales of books in this category. Japanese people have been publishing books about their experiences living in their former Japanese communities in China since the 1950s after the end of the war in 1945. The volume of these memoirs increased in the late 1960s through the 1970s. One example, giving details about the Japanese community in Fengtian, is by Fukuda Minoru (福田實), A History of the Japanese in Fengtian (滿洲奉天日本人史, Manchuria Manshū Hōten nihonjin shi; Tokyo: 謙光社, 1975). He gives details about the mood of the Japanese civilians between 1906 and 1945. An example from the 1980s would be Ikeuchi Hajime (池内はじめ), Warming Stone: The Setting Sun on Dairen Anjyaku: (温石: 大連の落日), Dairen no rakujitsu (Osaka: Dasō shobo大湊書房, 1980). The author discusses how frightened Japanese citizens reacted to Chinese people at the very end of the war. In Japan, one or two dozen books covering this topic are published every year.

The process of reconsidering and reflecting on the Japanese communities in Manchukuo has continued into the new millennium. One of the accounts of Japanese agricultural communities in Manchukuo is covered in the research titled Shimoina in Manchuria (下伊那のなかの満洲), Shimoina no naka no Manshū, (Iida飯田: Iida Institute of Historical Research Iidashi rekishi kenkyujō 飯田市歴史研究所), see especially Vol 5, 2007, pp 159−204. I can also point to my research on these topics in 'Salvaging Memories: Former Japanese Colonists in Manchuria and the Shimoina Project, 2001-12', Chapter 8 in Norman Smith, Ed., Empire and Environment in the Making of Manchuria, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 2017. Still, another example of these trends is Ueda Takako (上田貴子), Fengtian in the Modern Era (奉天の近代), Hōten no Kindai, (Tokyo University Press 東京大學出版會 Tōkyōdaigaku shuppankai, 2018). This covers the entire range of the Japanese in Fengtian including the commercial, industrial, and social services sectors.

There is another reason, I think, why the publisher decided to re-issue this title. It is because the story in the book reflects fairly accurately what the majority of Japanese (the mass market) think about the Japanese experiment in Manchuria. Tsukase himself grew up in the years of Japan's bubble economy (the 1970s−1980s) when the wartime memories were being replaced by the self-confidence and newer thinking of the truly post-war generation. He had not been immersed in the wartime militaristic education and he was seeing that a new Japan had emerged from the war.

If my assumption is correct, then we need to know what sort of story the book presents that reflect the current attitude of the Japanese public toward Japan's history in the twentieth century. So I made a brief overview of the book The Japanese in Manchuria (『満洲の日本人』 Manshū no Nihonjin) to allow us to see the tenor of Tsukase's remarks and the topics he selected to present in some detail.

-

In the twentieth century between 1906 and 1945, many Japanese civilians moved to Manchuria. The increase in their numbers rose in parallel with the strength of the Japanese economic and military influence in the region at that time. There was always a great disparity, Tsukase points out, between the controlling Japanese colonial authorities and the majority Chinese in Manchuria. The book examines the Japanese civilian communities that existed in Manchuria under Japanese colonialism.

Tsukase introduces the topic to the reader by making some observations on the nature of the Japanese movement into Manchuria. In the earliest days of their post-1905 treaty rights in south Manchuria, the Japanese authorities decided that they did not want to have unemployed or working-class people from the home islands moving to Manchuria. There were thousands of Chinese peasants and coolies who could be hired for low wages to carry out semi-skilled manual labor; there was no need to have Chinese and Japanese workers competing with each other for jobs. Instead, Japanese skilled workers (managers, chefs, shop owners) and educated professionals (university graduates, accountants, medical people) were welcome to move to the Japanese-controlled concession areas in Manchuria. Under the Japanese, the Chinese at all rungs on the economic ladder were always paid less than the Japanese citizens.

The Japanese at that time used the gold standard, while the Chinese economy stayed with the silver standard. Both systems of finance were being tried out by the various Western nations at the time. The Chinese especially, because they had a disorganized currency and banking system, suffered from the continuous fluctuation of exchange rates, which before 1932 could be different on the same day in different parts of the Three Eastern Provinces (Dongsansheng 東三省) of Manchuria. The Chinese tried valiantly to emphasize the stability of their currencies, and the Japanese worked doggedly to undermine confidence in Chinese money. When Manchukuo was established in 1932, finances were unified by the issuance of a new currency and banking structure, bringing relief to the day-to-day economies and the business communities of both the Japanese and the Chinese.

The first sizable Japanese civilian community in Manchuria was Dalian (大連). It was the largest ice-free port controlled by Japan to experience impressive economic growth, especially during the years of World War I. Soybeans (daizu大豆) were widely grown by Chinese farmers in the region (1914-1918). Soybeans were useful for fertilizer, animal fodder, and lubricating oil. Harvested soybeans were packed and transported through the South Manchuria Railway south to Dailan port for export. A large-scale transportation plan for vehicles within the city featured numerous traffic rotaries luxuriously planted with shrubbery and acacia trees giving the city a sense of being green and cozy. The traffic plan had come from Europe and few cities even in Japan could boast of this amenity. The Japanese in Dalian opened department stores, bookshops, medical clinics, schools for their kids, and trolley lines. It was an example of orderly urban living equal to the best of cosmopolitan life anywhere in the world at that time.

As Tsukase relates, Japanese enclaves of civilian communities expanded throughout Manchuria. Many of them adhered to the lines of the South Manchuria Railway and its major stations. They were in the commercial cities all along the route, and of course in the major cities of Dalian, Fengtian (奉天, in Japanese called Hōten), and Changchun (長春, in 1932 renamed Shinkyō 新京, the capital of Manchukuo). It was only in the city of Harbin (哈爾濱) that the Japanese did not form strongly identifiable neighborhoods. Instead, they lived among the Russian communities that dominated parts of Harbin in the Daoli (道裏區), and Nangang (南崗區) wards. In some ways, it seemed the Japanese identified with the international and expatriate sense that many Harbin Russians had.

The Japanese civilians appreciated their communities composed of neat lanes free of garbage or refuse, their homes of brick construction, and their like-minded fellow Japanese neighbors. Tsukase makes a point of saying that the Japanese had only fleeting contact with the Chinese who lived around them, and they usually felt little need to develop friendships with the Chinse. Japanese rarely learned to speak Chinese, though there was a 'pigeon-Chinese' (called pokoben ぽこべン) spoken. He gives some examples in the book. It seems to have consisted of a few Chinese phrases interspersed in a Japanese language sentence.

Tsukase says the Japanese communities, giving the example of Fengtian, had their own telephone systems, so they could not even call the Chinese shops in the area, since the Chinese communities used a different telephone exchange. The Japanese did not like to eat Chinese food, which they felt was smelly and dirty, and they preferred goods imported from the home islands whenever possible. They felt the nearby Chinese businesses had nothing they wanted. In practice, they kept interactions with the Chinese to a minimum.

To illustrate the gap between the majority Chinese and the Japanese expatriates, Tsukase reports on a survey published on 19 February 1924 in the Japanese language Manshū Nichinichi Shimbun 満洲日日新聞 (Manchuria Daily News). It was conducted in Dalian among Japanese schoolchildren, asking for their views. The article was titled 'Mujaki na Kodomo no Mita Chūgokujin' 無邪気な子供の見た中国人 (How Innocent Children See the Chinese). Their answers were ranked. First question: What do Japanese kids think of Chinese kids? (1) Dirty, unclean (Fuketsu 不潔), unsanitary (Fueisei 不衛生). (2) They steal things (Nusumu ga aru 盗むがある). (3) They are not properly polite (Reigi tashika naku 礼儀正しか なく), (i.e., they don't offer their seats to others (Zasseki o yuzuranai 座席を譲らない); they peek into the homes of other people (Tajin no uchi o nozoku 他人の家をのぞく)). (4) They are not honest (Shōjiki de nai 正直でない). (5) They are very greedy (Yoku ga fukai 欲が深い). They only think of themselves (Jibun no riika shika kangaienai 自分の利益しか考えない). They have no shame (Haji shirazu 恥じ知らず).

The second question asked what images came to mind when the kids thought about Chinese people? (1) The Queue (pigtail) (Benpatsu 弁髪), Foot binding (Densoku 纏足). (2) Their clothing (Ifuku 衣服): (which was) Midashinami身だしなみ Not neat, disorderly, disheveled. (3) Fireworks (Bakuchiku 爆竹). (4) Funerals (Sōshiki 葬式): Crying women (Namaki onna泣き女 ), Earth burial (as opposed to cremation, Dōso 土葬). (5) Foods (Shokuji 食事): Garlic (Ninniku にんにく), Very plain, Corse food (Shoshoku 粗食); They drop grains of rice on their beds (Zanhan o toko ni suteru 残飯を床に捨てる). The children's responses to these questions reflected the world from a child's point of view, and they equally reflected the opinions of most of the Japanese adults around them. Chinese and Japanese children sometimes played together, but it was not a common practice.

-

We should keep in mind that Tsukase's book does not report on the Japanese military personnel in Manchuria, or on the rural farmers from Japan from the late 1930s who were sent to the countryside to farm, or on the para-military Manchuria Youth Corps (ManMō Seishōnen Giyūgun 滿蒙青少年義勇軍), farm boys from Japan sent to help guard the borders against potential Soviet incursion. Instead, Tsukase focuses on the Japanese civilians who sought higher incomes and better living conditions by moving to Manchuria. He has given us a very insightful view of the community environment by recording examples of the children's survey responses as mentioned above, along with lists of the top officials of the South Manchuria Railway, who were graduates of Japan's most prestigious universities and were thus members of the Japanese elite. In other words, Japan imported its elite old-boy network into Manchukuo.

Scholars are still evaluating the extent to which Japan's approach to the evolving world from the 1870s on, following the Meiji Restoration (Meiji Ishin 明治維新) of 1868, influenced its East Asian neighbors. Among these influences, the Japanese language, we know, brought many new concepts and words into the vocabularies of the Chinese and Korean peoples. The highly structured educational system of the Japanese brought the discipline of European schooling into the Asian mainland. The style of police and bureaucratic administration introduced new ideas in how to control populations.

During the twentieth century, Japan was forcibly occupying several 'colonies' in the East Asian cultural sphere. One of the legacies they left in Taiwan, for example, was an overall acceptance of Japanese linguistic and cultural norms. In their other colonial adventures, the Japanese displayed an arrogance that remains distasteful to the formerly occupied peoples. The legacy of the Japanese occupation of Korea is a strong sense of enmity and sub-surface anger.

In the case of Japan's occupation of Manchuria, the context in which Tsukase's study is set, the cultural and linguistic values fostered within the Japanese civilian communities did not spread outward to influence the lives of the Chinese or Korean populations within the region. Of the topics covered in this book, one of the overriding Japanese influences that did alter the values and practices of the surrounding population in Manchuria, and in fact in Korea and China as well, was the physical infrastructure left by Japan. This consisted of roads, bridges, and rail lines; sturdily built public buildings, and the housing units constructed within each Japanese enclave. This infrastructure can still be widely seen in the areas once governed by Japan, including throughout Northeast China today. Many of the Japanese-era buildings are still in daily use.

To the extent that Tsukase's book reflects current attitudes of the Japanese public today, it appears the Japanese have gained a sense of psychological distance from those past days of aggressive nationalism and are thinking about the daily lives of their earlier compatriots with greater sense of perspective, and can accept the positive and less positive aspects of Japanese involvement in Manchuria.

Tsukase's work concentrates on the attitudes and practices of the Japanese living within their semi-isolating communities in Manchuria. He shows that the Japanese civilians were convinced of the superiority of their community lifestyle, but they were not proselytizing it to the neighboring Chinese communities. Many years have passed since the original members of these communities rapidly dispersed in 1945, but this book has again brought to life these once-active islands of Japanese society transported to Northeast China.

-

The author confirms sole responsibility for all aspects in this study.

-

Data derived from public domain resources. The data that support the findings of this study are available on the world wide web.

-

I am grateful for the help of Dr. Jonghyun Lee in preparing this article for publication.

-

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Suleski R. 2025. Perspective: thoughts on a Japanese language book Manchukuo and the Japanese people, based on the book Manshū no Nihonjin 満洲の日本人 (The Japanese in Manchuria). Publishing Research 4: e001 doi: 10.48130/pr-2024-0003

Perspective: thoughts on a Japanese language book Manchukuo and the Japanese people, based on the book Manshū no Nihonjin 満洲の日本人 (The Japanese in Manchuria)

- Received: 26 September 2024

- Revised: 03 December 2024

- Accepted: 16 December 2024

- Published online: 10 January 2025

-

Key words:

- Tsukase Susumu /

- Japanese-Chinese relations /

- Manchuria