-

Anthocyanins are a group of naturally occurring water-soluble pigments that are widely distributed in nature, primarily in colorful fruits, flowers, vegetables, leaves, and grains. They belong to the flavonoid family, a subclass of (poly)phenols. These pigments give a variety of foods their vibrant red, purple, blue, and black hues. Their specific coloration is pH-dependent: under acidic conditions (pH < 3), they appear red; in near-neutral environments (pH 4–6), they appear purple; and in alkaline conditions (pH > 7), blue-green [1,2].

In plants, anthocyanins play crucial roles, including attracting pollinators and seed dispersers through their bright colors, protecting plant tissues from ultraviolet (UV) light-induced damage and oxidative stress by neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS)[3], and acting as defensive compounds against herbivores and pathogens. From a dietary perspective, anthocyanins are widely present in many commonly consumed fruits and vegetables, particularly berries, grapes, red cabbage, eggplant, and purple carrots. Foods derived from these plants, such as red wine, fruit juices, and certain herbal teas, also contain anthocyanins in varying amounts[4−6] (Table 1).

Table 1. Food sources of anthocyanins, typical anthocyanin concentrations in the foods, and effects on host and gut microbiota associated with anthocyanins.

Category Food source Total AC content (mg/100 g FW) Major anthocyanidin aglycone(s) Anthropometrics and

clinical parametersGut health Gut microbiota Genes Metabolism and enzymatic activity Ref. 1. Berries Blueberry (Vaccinium sect. Cyanococcus) 57–503 Delphinidin, malvidin, cyanidin ↓Body weight gain;

↓fat accumulation; Improved liver damage, inflammation, glucose, and lipid metabolism; suppressed oxidative stress↓Gut permeability; ↓gut inflammation ↑Bacteroidota, Prevotella, and Oscillospira; ↓Actinobacterium, Allobaculum, and Bifidobacterium, Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio Restoration of SCFA [106−109] Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) 350–525 Cyanidin, delphinidin ↑Intestinal barrier function ↑Akkermansia, Aspergillus, Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, and Clostridia; ↓Verrucomicrobia and Euryarchaeota ↓AOX1, ↓CYP2E1, ↓TXNIP, ↓JAM-A, ↓VEGFR2, ↑CRB3, ↑CLDN14, ↑CDH4 ↓Digestive enzyme activity [110−113] Blackberry

(Rubus spp.)177–313 Cyanidin, delphinidin ↓Body weight gain;

↓fat accumulation; Improved liver damage, inflammation, glucose, and lipid metabolism↑Bacteroidota, Prevotella, and Oscillospira; ↓Actinobacterium, Allobaculum, and Bifidobacterium Restoration of SCFA; ↑Kynurenic acid [43,106,114] Black raspberry (Rubus occidentalis) 687 Cyanidin ↑Akkermansia, Desulfovibrio, Bacteroidetes, Barnessiella, and butyrate-producing bacteria; ↓Bacillota and Clostridium Regulation of short-chain and medium-chain fatty acids, polar metabolites, and phenolic metabolism [43,115−117] Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) 112–169 Peonidin, cyanidin Alleviated IBD symptoms Alleviated colonic ferroptosis and inflammation ↓Lactobacillus, Proteobacteria, and Escherichia-Shigella Modulated ferroptosis-associated genes (↑GPX4, ↑SLC7A11, and ↑HO-1) ↑SCFA; Restored glutathione (GSH) levels [43,118] Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) 18–42 Pelargonidin ↑Bifidobacterium; ↓Verrucomicrobia [43,119] Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) 1375 Cyanidin ↓Blood pressure; ↓Glycemia; Immune system stimulation No activation of Nrf2 ↑Activity of antioxidant enzymes in plasma; ↑Glutathione;

↓Uric acid[43,120,121] Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) 402–675 Delphinidin, cyanidin Restored TEER loss; ↓FITC-dextran transport induced by TNF-α [122,123] Chokeberry

(Aronia spp.)357–1,480 Cyanidin ↑Flow-mediated dilation ↑Anaerostipes, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Blautia, Faecalibaterium, Prevotella, Akkermansia; ↓Escherichia-Shigella, Megamonas, Prevotella, Bacillota:Bacteroidota ratio ↑FXR, TGR5 ↓Total bile acids [41,43,124,

125]Blackcurrant

(Ribes nigrum)476–591 Delphinidin, cyanidin ↑Bacteroidetes; ↓Verrucomicrobia and Bacillota:Bacteroidota ratio [126] Açaí

(Euterpe oleracea)97–410 Cyanidin ↓Body weight, hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance ↑Akkermansia; ↓Bacteroides/Prevotella, Hathewaya ↑SCFA [127−130] Black goji berry, black wolfberry (Lycium ruthenicum) 470–530 Petunidin ↓Body weight gain ↑Intestinal barrier function ↑Akkermansia, Alistipes, Allisonella, Bacteroides, Barnesiella, Bifidobacterium, Coprobacter, Eisenbergiella, Muribaculaceae, Odoribacter, Ruminococcaceae; ↓Bacillota:Bacteroidota ratio ↑mRNA IL-10, ZO-1, OCLN, CLDN-1 and MUC1; ↓mRNA TLR4, NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, TGF-β1, GPR5, iNOS, COX-2, and IFN-γ ↑SCFA; ↓lipopolysaccharides [131−135] 2. Other fruits Cherry

(Prunus avium)101–143 Cyanidin, peonidin ↑Antioxidant capacity ↓the release of IL-6 and IL-8 production in intestinal cells and glutathione peroxidase activity stimulated by cytokine [43,90,136] Grape (Vitis spp.) 16–120 Malvidin, delphinidin, peonidin ↑Bacteroidota, Prevotellaceae, and Erysipelotrichaceae; ↓Desulfovibrionaceae and Spreptoccaceae ↑mRNA Lyz1 [43,137] Plum

(Prunus domestica)15–146 Cyanidin ↓Blood pressure; ↓Fasting plasma insulin, glucose, leptin, inflammatory cytokines [43,138,139] Pomegranate (Punica granatum) 17–39 Delphinidin, cyanidin ↓body weight gain; ↓Steatosis scores; ↓Insulin resistance index ↑Bacteroidota, Akkermansia, Parabacteroides, Anaerotruncus, and Lachnoclostridium;

↓Bacillota and ProteobacteriaImproved gene expression profiles involved in glucose and lipid metabolism (↑Cpt1b; ↑Hepatic lipase; ↑Insig1; ↑Insig2; ↑Irs2; ↓Pepck; ↓G6pc) ↓Pancreatic lipase [140,141] Blood orange (Citrus × sinensis) 1–17 Cyanidin; malonated anthocyanins Improved blood pressure and plasma VCAM-1; ↓Fasting glucose; ↓Insulin; ↓HOMA.IR Significant associations between Bacteroidota, Prevotella 9, and cardiometabolic biomarkers [142,143] 3. Vegetables Red cabbage (Brassica oleracea) 281–363 Cyanidin ↓IL-1β; ↓IL-6 ↑Butyrate-producing bacteria Promoted MAPK signaling pathway [43,144] Purple carrot (Daucus carota ssp. sativus) 40–50 Cyanidin, pelargonidin ↓body weight gain; ↓Triglycerides; Improved high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio ↓Cecal pH ↑α- and β-Glucosidase; α- and β-Galactosidade; β-glucuronidase; ↑Total cecal SCFA [145−147] Eggplant (Solanum melongena) 86 Delphinidin (e.g., nasunin) Inhibitory activity against lipoxygenase (LOX), lipase, and α-amylase [43,148] Purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) 52–175 Peonidin, cyanidin ↓body weight gain; ↓Triglycerides; ↓total cholesterol ↑Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus ↓TLR-4; ↓NF-κB; ↓interleukin 6; ↓tumor necrosis factor α; Preserved Nrf2 gene expression ↑serum activities of glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, catalase; ↑SCFAs; ↓malondialdehyde; ↓lipopolysaccharides [149−151] Purple cauliflower (Brassica oleracea) 71–77 Anthocyanins ↑Neurotransmitters ↑tyrosine receptor kinase B; ↑brain-derive neurotrophic factor (BDNF); ↑phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2 and CREB [152,153] Red onion

(Allium cepa)49 Cyanidin Prevented lipid ester hydrolysis; Conferred protective effect against phospholipase Inhibited pancreatic lipase [43,154] 4. Grains and legumes Black rice

(Oryza sativa)5–168 Cyanidin, peonidin ↓body weight gain; ↓serum triglycerides; ↓total cholesterol ; ↓non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Improved blood glucose, insulin resistance, serum oxidative stress state, lipid metabolism and inflammatory cytokines levels, and alleviated liver damage. ↑Villus height (ileum and caecum); ↑Goblet cell number per villus of the colon; Positive effect on TEER and FITC-dextran permeability ↑Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, Phascolarctobacterium, Bacteroides, and Coprococcus; ↓Bacillota:Bacteroidota ratio ↑mRNA of JAM-A, occludin and Muc-2; ↑Genes involved in cholesterol uptake and efflux; Regulated AMPKα; Preserved CYP7A1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 5/8 mRNA expression ↑Cecal SCFA; ↑fecal sterols excretion [76,123,

155,156]Purple maize

(Zea mays)93–1640 Cyanidin, pelargonidin, peonidin ↑antioxidant potential; ↑Fatty acid oxidation; ↓body weight gain; ↓serum triglycerides; ↓total cholesterol ; ↓Epididymal fat mass ↓PPARγ; ↓C/EBPα; ↓SREBP-1c; ↑PPARα; ↑PGC1α,; ↑PRDM16; ↑FGF21; Promoted Hepatic AMPK activity Improved rumen volatile fatty acids [157−159] Black bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) 213 Cyanidin Improved blood glucose, insulin resistance, serum oxidative stress state, lipid metabolism and inflammatory cytokines levels, and alleviated liver damage. ↑Akkermansia, Phascolarctobacterium, Bacteroides, and Coprococcus Activated AMPK, PI3K, and AKT; Inhibited HMGCR, G6pase and PEPCK expression [155,160] 5. Beverages and processed foods Red wine 6–12 Malvidin, delphinidin, peonidin ↓BMI ↑α-diversity, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Eggerthella lenta [161−163] Hibiscus tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa) 35–66 Delphinidin, cyanidin ↓serum triglycerides; ↑Antioxidant capacity; ↑IL10 Superoxide dismutase; ↑Malondialdehyde; ↑Lysozymes [164,165] In humans, anthocyanins are known for their wide range of potential health-promoting properties. Among their most researched health benefits are their antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory effects, which may further help reduce the risk of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders[7], although the evidence for the antioxidant properties in human health is considered insufficient[8]. They also exhibit beneficial anti-diabetic properties for both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes; they help regulate glucose metabolism, enhance insulin secretion, reduce insulin resistance, improve glucose uptake, and lower post-meal blood sugar levels by modulating glucose transporters and signaling pathways[9]. Additionally, among the health benefits of anthocyanins, their role in supporting and protecting the gut microbiota is an important aspect, as gut health is crucial for overall well-being[10−12].

Anthocyanins are relatively unstable compounds, prone to degradation when exposed to light, heat, or oxygen. Despite limited bioavailability, their stability can be improved through glycosylation, the presence of acyl groups, and their metabolism in the digestive system. Additionally, interactions with the gut microbiota enhance their bioavailability[3,13].

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles less than 5 mm in diameter and have become a significant environmental concern due to their pervasive presence in ecosystems worldwide[14,15]. This pollution is considered one of the most pressing environmental challenges of the 21st century[16]. Microplastics originate from a variety of sources, including the breakdown of larger plastic debris and the release of micro-sized plastics from everyday products. The widespread use of plastics over the past few decades has resulted in significant environmental contamination, leading to concerns about the long-term impacts on wildlife, human health, and the planet's ecological balance[14−16].

Microplastics can be categorized in several ways. They are broadly divided into two types based on their origin: primary and secondary. Primary microplastics are directly manufactured in small sizes and are used in consumer products, such as (1) microbeads—tiny plastic particles found in personal care products, such as exfoliating facial scrubs, toothpaste, and body washes[17,18], (2) microfibers—synthetic fibers from fabrics (e.g., polyester, nylon) released during washing of clothes[19], (3) pre-production plastic industrial pellets—used in manufacturing processes and often lost to the environment during transport or handling[20]. Secondary microplastics result from the fragmentation of larger plastic debris due to weathering, UV radiation, and mechanical forces. Common sources include: (1) plastic waste—such as plastic bags, bottles, and packaging—that degrades over time[21], (2) marine debris—fishing nets, ropes, and other plastic items that deteriorate in the ocean[22], (3) tire wear particles—resulting from the abrasion of vehicle tires on roads, which release microplastic particles into the air and water[23]. Microplastics are categorized into five types based on their physical forms: fragments, fibers, foam, pellets, and films[24]. Moreover, they can be grouped into six major categories based on the chemical structure of the polymer backbone: polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS), polypropylene (PP), polyurethane (PU), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET)[25]. Polystyrene is one of the most widely studied microplastics due to its negative influence on the gut microbiota and its role in causing metabolic disorders[26].

The presence of microplastics in the environment has raised concerns about their potential impact on human health[27]. Given their small size and persistence, microplastics can be ingested or inhaled, leading to concerns about their bioaccumulation and toxicity in humans. Nanoplastics, a subtype of microplastics less than 1 µm in size, can even penetrate important biological barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier, placental barrier, and gut barrier[28]. Some research has suggested that prolonged exposure to microplastics may increase the risk of metabolic disorders, such as obesity and diabetes, by influencing gut bacteria or promoting chronic inflammation[29−31]. While data on long-term health effects are limited, animal studies have shown that microplastic exposure can lead to tissue damage, inflammation, oxidative stress, and disruption of cellular processes. Potential toxicological impacts of microplastics are also related to their chemical composition. Many plastics contain toxic additives, such as phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), and heavy metals, which can leach out and exert endocrine-disrupting or carcinogenic effects[32]. Additionally, microplastics can act as vectors for environmental pollutants, such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which may further amplify health risks upon entry into the body[33].

Given the increasing concern about the impact of microplastics on human health, particularly their ability to disrupt gut microbiota composition and function, identifying potential protective strategies is essential[34−36]. Microplastic ingestion has been associated with alterations in microbial diversity, intestinal inflammation, and compromised gut barrier integrity, which may contribute to broader metabolic and immunological consequences[37,38]. In this context, anthocyanins, with their well-documented antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and prebiotic properties, may offer a promising dietary approach to counteract these adverse effects[39]. By modulating gut microbiota composition, promoting beneficial bacteria, and reinforcing gut barrier function, anthocyanins may serve as a natural intervention to mitigate the harmful effects of microplastic exposure.

The novelty of this review lies in its exploration of anthocyanins as a natural protective strategy against microplastic-induced gut microbiota disruption—a connection that has not been extensively discussed in the existing literature. While previous studies have separately examined the harmful effects of microplastics on gut health and the beneficial properties of anthocyanins, this review integrates these perspectives to explore the interplay between microplastics, gut microbiota, and anthocyanins, shedding light on the potential role of anthocyanins in preserving gut health in the context of environmental pollutants.

-

Anthocyanins are widespread in nearly all groups of flowering plants (Angiospermae) and are, therefore, present in varying amounts in most edible plants. One exception is the order Caryophyllales—including amaranths, beets, and cacti—the members of which produce betalain pigments instead of anthocyanins[40]. Among plant foods, the highest concentrations of anthocyanins are found in fruits that are commonly consumed as berries, particularly in species belonging to Aronia, Empetrum, Ribes, Rubus, and Vaccinium. Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum L.) and chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa Michx.) have some of the highest known concentrations of anthocyanins among edible plants, about 500 mg/100 g fresh weight (FW) and 360 mg/100 g FW, respectively[41]; however, they are not commonly eaten as such (fresh with peels) due to their less favorable sensory properties, such as astringency, compared to more widely consumed berries. For instance, bilberry peel has an anthocyanin content of 2,026 mg/100 g, whereas the fruit pulp has a considerably lower concentration (104 mg/100 g)[42]. Therefore, anthocyanin-rich fruits and berries typically consumed unprocessed with their peels often become the richest sources of anthocyanins in the diet; in the United States, raw (unprocessed) blueberry have been estimated as the largest contributor (27%) to dietary anthocyanin intake[43]. The same study by Wu et al. found negligible or zero amounts of anthocyanins in processed foods containing anthocyanin-rich ingredients, which can be attributed to either a low content of the anthocyanin-rich ingredient in the product or the destruction of these unstable molecules during food processing[43]. Table 1 lists common sources of anthocyanins and their typical concentrations in the foods.

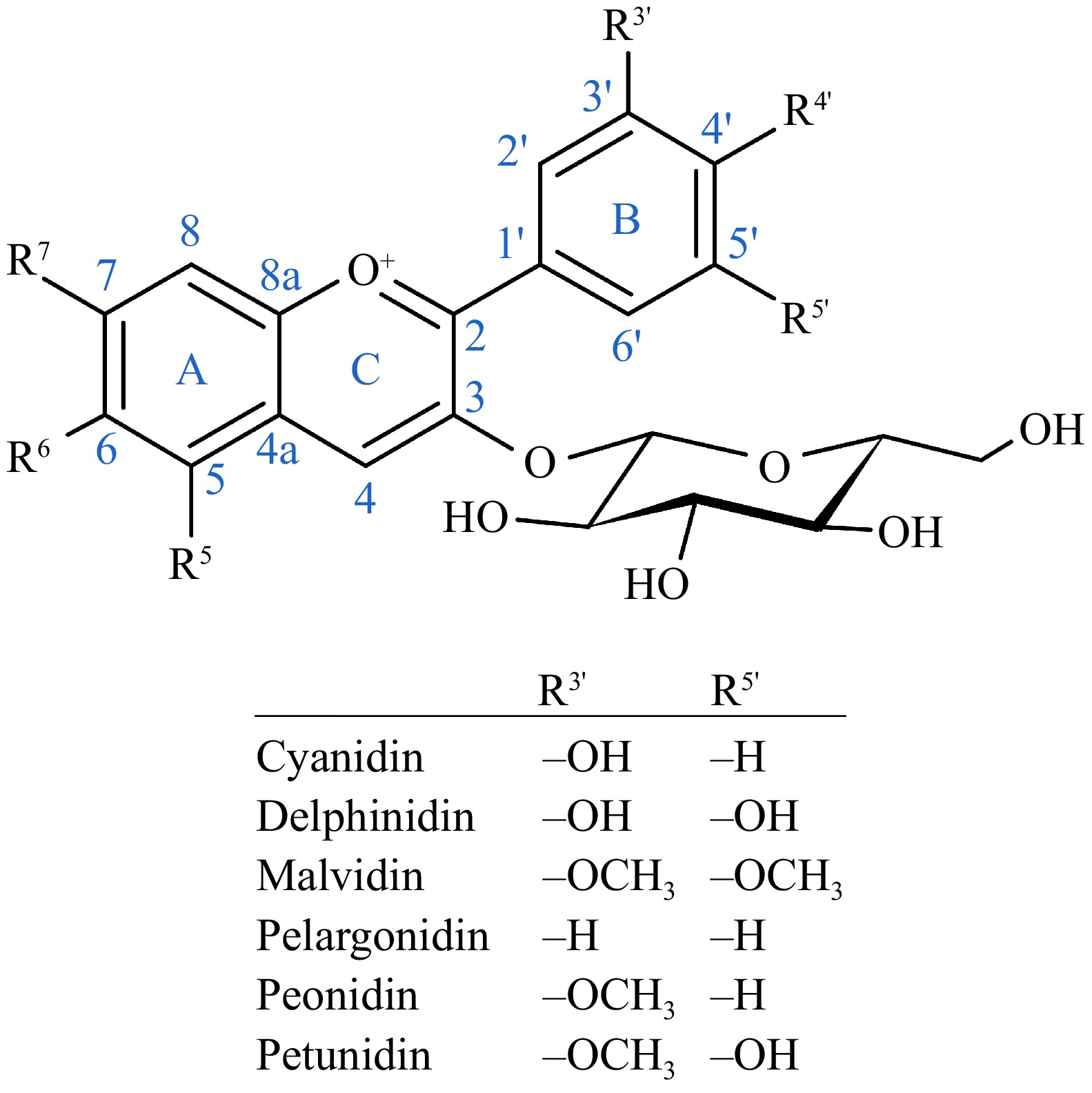

Structural diversity of anthocyanins

-

Anthocyanins are glycosylated forms of anthocyanidins, consisting of an aglycone core (anthocyanidin) bound to one or more sugar moieties, which influence their stability, solubility, and color expression[4]. They should not be confused with proanthocyanidins, another group of flavonoids with similar biological properties, which are polymers of flavan-3-ol structural units[44]. The six most common anthocyanidin aglycones—cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and petunidin—differ in their substituents located at the 3′ and 5′ positions of the C6-C3-C6 flavonoid backbone, which is composed of two aromatic benzene rings (A and B) connected by a three-carbon bridge that forms a heterocyclic C-ring (Fig. 1). Anthocyanins are typically glycosylated at the 3-position of the C-ring, but glycosylation can also occur at the 5-, 7-, and 4′ positions. Common sugars attaching to the core structure include glucose, rhamnose, galactose, xylose, and arabinose. These sugars can further form acylated anthocyanins by attaching phenolic acyl groups, such as p-coumaric, ferulic, and caffeic acids. The specific sugar moieties and their attachments influence anthocyanin stability, solubility, and color expression; for example, glycosylation at the 3-position improves the thermal stability of the compounds[4].

Figure 1.

General structure of an anthocyanin with a glycosyl group at position 3[45], and the functional groups of the six most common anthoyanidins at positions 3′ and 5′.

Bioavailability and interaction of anthocyanins with gut microbiota

-

Food processing significantly influences the bioavailability of anthocyanins[46]. Processing methods can either degrade or enhance the ability of anthocyanins to reach the colon intact, impacting their subsequent interaction with the gut microbiota. Various factors, including temperature, pH, and interactions with other food components - such as fats, proteins, and alcohol - can affect their structural integrity and absorption[47]. Acylation can enhance anthocyanin stability but may reduce its bioavailability[48], increasing the likelihood of intact anthocyanins reaching the colon. The structural variation of anthocyanins also affects their absorption, with pelargonidin-based anthocyanins being more efficiently absorbed than those containing additional substituents on the B-ring[49]. Thermal processing, a common practice in food preparation, often leads to a reduction in anthocyanin content. However, it can also enhance bio-accessibility by breaking down plant cell walls, thereby increasing the availability of anthocyanins for absorption[50]. Furthermore, anthocyanins interact with various food constituents that can either promote or hinder their bioavailability by influencing their solubility, stability, or binding capacity[50].

To exert bioactivity in the colon where the majority of the human gut microbiota resides, a sufficient proportion of the dietary anthocyanins must avoid absorption or destruction during earlier phases of digestion. Up to 50% of anthocyanins are metabolized and partially degraded already in the oral cavity by oral microbiota[13]. Anthocyanins are stable at low pH and, therefore survive the gastric phase with a very high recovery rate, although 8% to 25% of anthocyanin glycosides are absorbed in the stomach[11]. They have a relatively low absorption rate from the small intestine, with a wide range of estimates from as low as 0.005% to 22%[13]. In the colon, the remaining anthocyanins are rapidly converted into more bioavailable metabolites by microbiota, either through breakdown into aldehydes or phenolic acids or by conjugation with methyl, hydroxyl, sulfuric, or glycosidic groups[11]. Thus, these microbial metabolites of anthocyanins need to be considered when assessing the bioavailability and the bioactivity of anthocyanins.

It is generally considered that when anthocyanins are entrapped within a complex food matrix, they have a better chance of surviving until the small intestine and colon compared to purified compounds, although the evidence remains inconclusive[46−50]. The bioavailability of anthocyanins is generally low, at approximately 1%, although cyanidin-3-O-glucoside has been reported to have a bioavailability of 12%[51]. This emphasizes their potential role within the gut lumen in exerting health benefits.

Individual differences in gut microbiota also play a crucial role in anthocyanin metabolism and bioactivity. Since a significant portion of anthocyanins reaches the colon intact, where they are metabolized by gut microbes, their ultimate bioactivity depends on microbial composition and enzymatic capacity. Microbes capable of metabolizing anthocyanins in the gut include species in genera Bacteroides, Clostridium, Enterococcus, and Eubacterium[11]. These bacteria use hydrolyzing enzymes, such as α-galactosidase, α-rhamnosidase, and β-glucosidase, for cleaving the sugar linkages, resulting in the hydrolyzation of all anthocyanins in as little as 20 min in vitro[52]. The anthocyanidin aglycones released in the enzymatic process are unstable and are further metabolized by the microbes into phenolic aldehydes and phenolic acids; this conversion process reaches its peak at 60–120 min after inoculation during in vitro human colonic fermentation[53]. The exact metabolites produced from the anthocyanins depend on the functional groups at the 3′ and 5′ positions of the anthocyanidin aglycone (Fig. 1) and the possible acyl groups[11]. Cyanidin-derived anthocyanins are first metabolized into phloroglucinol aldehyde (2,4,6-trihydroxybenzaldehyde), protocatechuic acid (PCA; 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid), and p-coumaric acid (4-hydroxycinnamic acid). Protocatechuic acid is considered the main gut microbial metabolite of anthocyanins. Delphinidin-derived anthocyanins produce gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid), syringic acid (4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid), and phloroglucinol aldehyde. Malvidin-derived anthocyanins produce syringic acid, pelargonidin-derived anthocyanins, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid; peonidin-derived anthocyanins, vanillic acid (3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid); and petunidin-derived anthocyanins 3-O-methylgallic acid (3,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxybenzoic acid). At the same time, the acylated phenolic groups are released as phenolic acids. These metabolites are further transformed by the bacteria; for example, vanillic acid is demethylated into protocatechuic acid, which can be hydroxylated into gallic acid.

Anthocyanins and their metabolites also impact the composition of gut microbiota. One of the main effects of anthocyanin intake on microbiota is the reduced ratio of Bacillota:Bacteroidota (the former previously named Firmicutes and the latter Bacteroidetes), two major bacterial phyla present in a typical gut microbiome[11]. A high Bacillota:Bacteroidota ratio has been linked with obesity. Anthocyanins isolated from foods also generally increase the abundance of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria, including Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Prevotella, and decrease the abundance of Clostridium, Escherichia-Shigella, Hathewaya, and the Bacteroides : Prevotella ratio (Table 1). However, some studies on anthocyanin-rich foods have reported a decrease in Bifidobacterium and Prevotella. The β-glucosidase activity of anthocyanin-metabolizing bacteria allows them to release the sugar units from anthocyanins to be used as their energy source thus promoting their growth[12]. The microbial metabolites produced from the anthocyanidin aglycones also play a role in modulating the gut microbial composition; for example, gallic acid inhibits the growth of Hathewaya histolytica (formerly Clostridium histolyticum) and promotes Atopobium[54]. The following chapters examine the processes by which microplastics disrupt gut microbiota and how the interaction between microbes and anthocyanins described in this chapter—as well as other anthocyanin properties—could alleviate the disruption.

-

The gut microbiota is closely linked to host health and various disorders. These microorganisms play a crucial role in the interactions between the intestines and the host. Any environmental disruption in the composition of intestinal bacteria can have a negative impact on the host balance and its essential functions[55]. Research has documented the effects and toxicities of microplastics, such as disruptions in gut microbiota, damage to intestinal function, and metabolic problems[37,38].

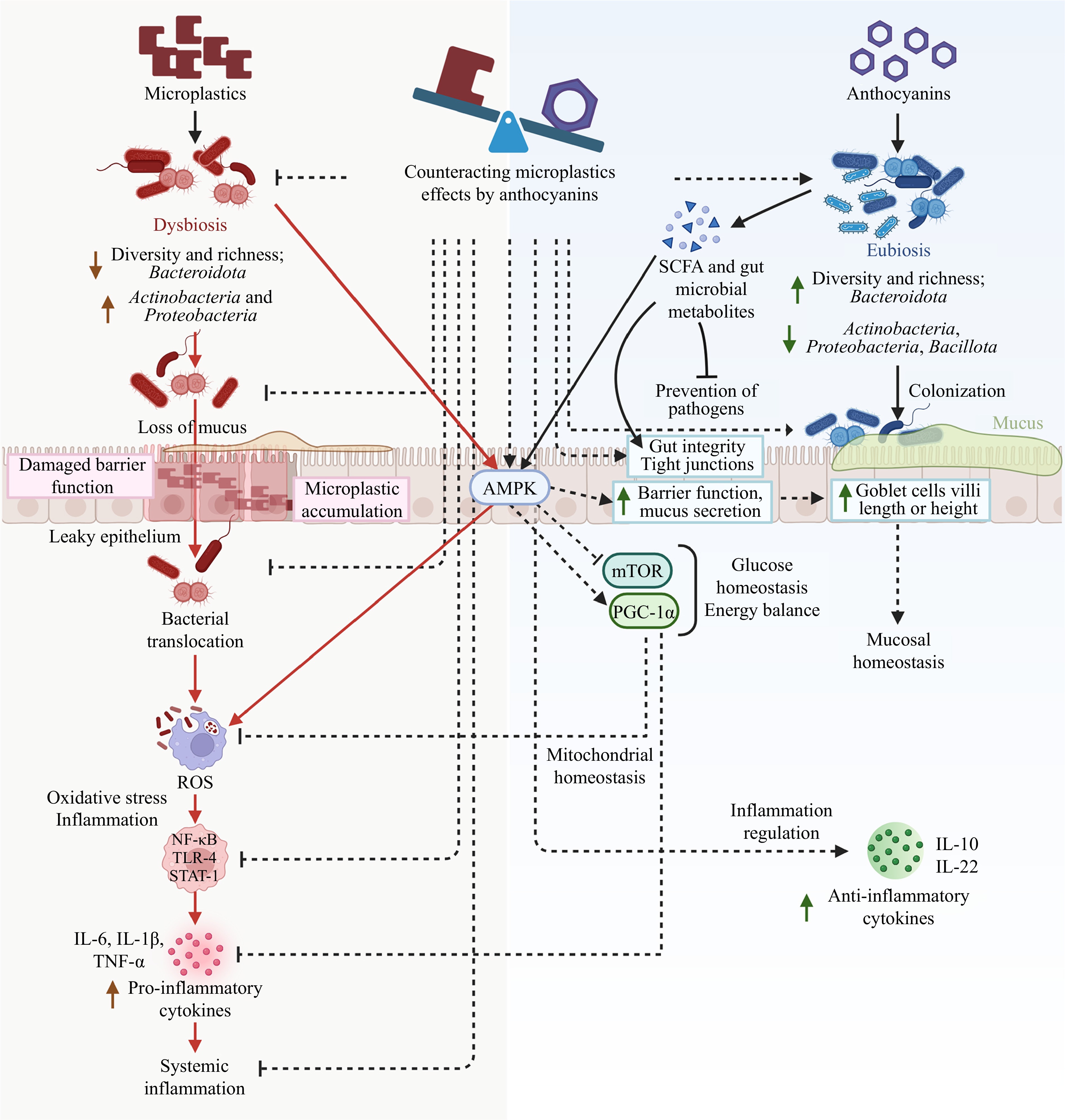

Microplastics, once ingested, can interfere with the normal functioning of gut microbiota, leading to dysbiosis (Fig. 2). Notably, exposure to microplastics consistently reduces the relative abundance of the Bacteroidota phylum, which is known for its anti-inflammatory effects on the gut[56,57]. Additionally, microplastic exposure decreases species richness and diversity within the gut microbiome, thereby altering the expression of various genes and metabolites involved in lipid, nucleic acid, and hormone metabolism, as well as in protein secretion, neurotoxicity, inflammation, aging, metabolic diseases, and cancer[57−60]. As an example, exposure to microplastics has been shown to upregulate genes involved in the immune function, including H2-DMb2, H2-Eb, and Gm8909, as well as genes encoding defensins and antioxidant enzymes such CAT, SOD, and GstD1[61]. The levels of MDA, a marker of oxidative stress, also increased[61]. Furthermore, TLR2, TLR4, Ap-1, and IRF5 increased, suggesting an enhanced immune and inflammatory response in the intestine. At the metabolic level, microplastic exposure suppressed pathways involved in lipid metabolism, hormonal regulation, cellular repair and replication, and xenobiotic detoxification. Conversely, genes related to the metabolism of carbohydrates, nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorus were upregulated, along with genes linked to cellular stress responses (cspB, desK, pspA, lpr, groEL, hshX, catalase, oxyR, soxR, narJ)[61].

Figure 2.

Impact of microplastics on gut microbiota and the known and proposed (dashed lines) mechanisms of action of anthocyanins in counteracting dysbiosis.

Increased intestinal permeability is another significant functional change linked to microbial dysbiosis caused by microplastic exposure[57]. Previous studies have demonstrated that microplastic exposure significantly reduces mucus secretion by goblet cells, which play a crucial role in protecting the intestinal lining[62]. This weakened mucus barrier increases the susceptibility of the intestinal epithelium to pathogenic bacterial infiltration. Additionally, microplastics have been shown to compromise intestinal morphology by reducing villus height, disrupting villus integrity, decreasing villus surface area, increasing crypt depth, and altering crypt structure[62]. These structural changes, coupled with a reduction in small intestinal epithelial cells and impaired cell maturation, further diminish the synthesis and secretion of digestive enzymes, ultimately weakening the capacity for nutrient absorption.

Furthermore, microplastics disrupt intestinal structure, impair absorption efficiency, and weaken defense mechanisms, leading to digestive dysfunction and compromised barrier integrity in mouse small intestines. Gene expression analysis has revealed a significant downregulation of claudin family genes in both the duodenum and jejunum, which are essential for maintaining intestinal permeability and structural integrity[62,63]. This disruption destabilizes the tight junction protein network, reducing intestinal barrier tightness and triggering immune imbalances and inflammatory responses[62,63]. The resulting intestinal damage further exacerbates gut dysfunction.

Beyond structural and functional impairments, microplastic exposure has also been linked to gastric injury and inflammation[64]. The inflammatory response may be triggered through cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8), released by activated immune cells like macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells. Alternatively, microplastics may induce phagocytosis, leading to ROS production and subsequent apoptosis[65].

The exact mechanisms by which microplastics disrupt the gut microbiota are poorly understood. One possibility is that the ingestion of microplastics may cause mechanical damage to the gastrointestinal tract, potentially leading to abrasions, perforations, or obstructions[66]. These physical injuries could impair nutrient absorption, resulting in reduced body size, weight loss, and compromised growth and reproductive fitness[66]. Additionally, microplastics may fragment and translocate across biological barriers. The physical presence of microplastics in the gut may directly interact with the gut microbiota, influencing microbial growth, survival, and metabolic functions[67]. They can provoke immune and inflammatory responses and restructure gut epithelial villi[68]. In particular, microplastic ingestion has been known to increase the phagocytic activity of immune cells, suggesting an immune-driven inflammatory response often associated with dysbiosis. This dysbiosis may be driven by the oxidative state induced by inflammation, which may favor the proliferation of bacterial taxa such as Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria that thrive in such hostile conditions[66,69]. Alternatively, the chemical composition of microplastics, including environmental pollutants or endocrine disruptors adsorbed onto their surfaces—such as bisphenol A and plasticizers—could also exert direct or indirect effects on the gut microbiota[67]. Additionally, microplastics have been shown to act as carriers for additional pollutants or pathogens, thereby adding complexity to their impact on gut microbial communities[67]. Microplastics can harbor foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella enterica, which, when bound to microplastics, may exhibit increased resistance to environmental stressors and persist longer in the gut[70]. Bacteria readily adhere to microplastics surfaces, leading to biofilm formation. Within these biofilms, bacteria are embedded in a self-secreted exopolymeric substance (EPS), which provides structural support and enhances bacterial survival. For example, in Salmonella enterica, cellulose and O-antigens within the EPS are critical for initial attachment and biofilm persistence, particularly on plastic surfaces[70]. This ability of microplastics to promote biofilm formation and shield pathogens from host immune defenses can exacerbate gut dysbiosis, trigger inflammatory responses, and may increase the risk of gastrointestinal infections. Microplastics may even function as vectors for pathogens to infiltrate the digestive system, further compounding the ecological risks posed by these contaminants[66].

-

As discussed in the previous chapter, microplastics can disrupt gut microbiota in various ways, including adverse changes in the relative abundance of certain bacteria taxa, decreased microbial richness and diversity, increased immune and inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, increased intestinal permeability, and other adverse morphological changes, as well as direct interaction with microbes, such as serving as a growth surface for pathogenic bacteria. Anthocyanins may play a significant role in protecting gut microbiota from microplastics-induced disruption, as they possess several properties that can counteract many of these adverse effects. Figure 2 provides an overview of the confirmed and potential mechanisms of these counteractions.

Despite the well-documented antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and gut microbiota-modulating properties of anthocyanins, studies examining their protective effects against microplastic-induced toxicity remain limited. Existing research suggests that, in particular, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G), an extensively studied anthocyanin, can mitigate polystyrene-induced toxicity by activating autophagy, promoting fecal discharge and alleviating oxidative stress and inflammation[71,72]. Additionally, anthocyanins may offer protective effects against reproductive toxicity induced by microplastics and nanoplastics, potentially through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, modulation of steroid receptors, and restoration of hormonal balance[73]. However, comprehensive studies on the effects of anthocyanins on microplastic toxicity are still lacking, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

It is currently hypothesized that anthocyanins and their colonic metabolites can act as modifiers to change the composition of the gut microbiota. These compounds mainly exert their effects by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria and inhibiting or suppressing the proliferation of harmful bacteria[74]. Numerous studies conducted in laboratory, animal, and even human models have shown that anthocyanins and their metabolites can improve the balance of intestinal microbiota and thus improve intestinal health and related functions. Previous studies have demonstrated that anthocyanin supplementation offers significant benefits to intestinal health, including improvements in the gut microbiota population, enhanced production of SCFAs, increased goblet cell numbers, and better tight junction protein expression and villi structure[12]. Specifically, dietary intake of anthocyanins has been linked to an increased abundance of Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes[12]. Anthocyanins influence gut microbiota by promoting SCFA-producing bacteria, which lower intestinal pH, thereby inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria. SCFAs, such as butyrate, serve as an energy source for epithelial cells, strengthening the intestinal barrier and preventing the translocation of pathogens and antigens[75]. These potential effects in addressing chronic diseases associated with changes in gut microbiota—including chronic inflammation, obesity, and type 2 diabetes—have also been noted by researchers[76].

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties

-

Oxidative stress plays a significant role in the damage caused by microplastics[77,78]. When microplastics are absorbed, they compromise cell membrane integrity, alter the lipid bilayer, create pores, and increase intracellular reactive oxygen species production. This ROS generation leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and cellular damage[79]. Furthermore, elevated levels of ROS have been demonstrated to induce gut microbiota dysbiosis by altering microbial composition, impairing epithelial barrier function, and interfering with metabolic pathways[80]. Moreover, microplastics can stimulate chronic inflammation by activating markers such as NF-κB, MyD88, and NLRP3, leading to oxidative stress and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β[81]. The persistent activation of these pathways can result in harmful inflammatory responses and reduced cellular metabolic activity[81].

Anthocyanins are known for their strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which are critical in protecting gut health. These properties help mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation induced by microplastics, thereby preserving the integrity of the gut microbiota and the gut barrier. Studies indicate that anthocyanins play a crucial role in reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, as well as lowering the risk of chronic diseases[39]. For instance, blueberry anthocyanins have been shown to significantly inhibit ROS accumulation in endothelial cells exposed to high glucose while preserving the activity of antioxidant enzymes[82]. Studies by Rehman et al. and Ma et al. have further confirmed anthocyanins' ability to significantly reduce ROS production in vitro and in vivo[83,84]. In particular, anthocyanin-rich berry extracts have been found to attenuate H2O2-induced ROS generation and suppress lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced nitric oxide production in BV-2 microglia[83]. Additionally, research by Ryo Furuuchi et al., using a diet-induced obesity mouse model, demonstrated that supplementation with borsenberry polyphenols and anthocyanins can inhibit ROS production in the aorta[85].

Anthocyanins have a high antioxidant capacity due to their phenolic structure and work by inhibiting or neutralizing free radicals through the donation or transfer of electrons from hydrogen atoms[86]. Additionally, anthocyanins have the potential to reduce the risk of diseases due to their anti-estrogenic, anti-inflammatory, and cell proliferation-inhibition effects. They help counteract inflammation caused by microplastics through the modulation of key inflammatory pathways. Anthocyanins can inhibit the NF-κB pathway by blocking the translocation of the p65 subunit to the nucleus, thereby reducing cytokine expression[87]. For instance, strawberry anthocyanins significantly inhibited the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway[88], while anthocyanins from blueberry reduced serum levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ, increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-22 in colon patients[89]. Moreover, sour cherry anthocyanins have also been shown to prevent the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 in human Caco-2 cells[90]. Additionally, anthocyanins suppress the MAPK signaling pathway, reducing the inflammatory response. For example, anthocyanins extracted from Lycium ruthenicum was capable of attenuating inflammation by suppressing the activation of MLK3 and its downstream JNK and p38MAPK signaling cascades[91]. Moreover, anthocyanins modulate Toll-like receptor (TLR) activity, as evidenced by Myrica rubra anthocyanins, which reduced TLR4 and TNF-α expression in a cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury model in mice[92].

More recently, it has been discovered that these compounds can decrease the accumulation of lipids during the differentiation process of fat cells, highlighting their role in preventing obesity and related problems[93]. The findings of Chen et al.[72] indicated that cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G) supplementation significantly decreased tissue accumulation and enhanced fecal PS excretion, resulting in the mitigation of PS-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Simultaneously, C3G influenced PS-related alterations in the gut microbiota and modified functional bacteria involved in inflammation, including Desulfovibrio, Helicobacter, Oscillospiraceae, and Lachnoclostridium. C3G treatment prompted modifications in functional pathways in response to xenobiotic PS and decreased bacterial functional genes associated with inflammation and human diseases. They revealed that these findings may provide support for the protective function of C3G in mitigating PS-induced toxicity and gut dysbiosis[72]. Another study evaluated the protective effect of delphinidin (25 mg/kg) to prevent renal dysfunction caused by polystyrene microplastics (PSMP). The findings demonstrated that PSMP exposure increased the expression of Keap1 and decreased the expression of Nrf-2 and antioxidant genes. Upon PSMP exposure, levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as IL-1β, TNF-α, NF-κB, IL-6, and COX-2 activity were elevated. Nonetheless, the renal deficits caused by PSMP were significantly improved with delphinidin therapy[94].

Chen et al. found that C3G effectively reversed the increased mRNA expression (Il-6, Il-1β, and TNF-α) and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) caused by PS exposure[95]. C3G substantially reduced the decrease in levels (IL-22, IL-10, and IL-4) and the downregulation of mRNA expression (Il-22, Il-10, and Il-4) of anti-inflammatory. Furthermore, C3G suppressed the PS-induced phosphorylation of the transcription factor NF-κB in the nucleus, along with the elevated protein expression levels of iNOS and COX-2 in the colon. The metabolic activities of gut bacteria involving tryptophan and bile acids are significantly associated with the control of inflammatory responses. The gut microbiota results revealed that PS treatment markedly elevated the prevalence of pro-inflammatory bacteria (Desulfovibrio, unclassified bacteria in the family Oscillospiraceae, Helicobacter, and Lachnoclostridium) while reducing the prevalence of anti-inflammatory bacteria (Dubosiella, Akkermansia, and Alistipes). Intriguingly, C3G intervention reversed these pro-inflammatory alterations in bacterial abundances and boosted the enrichment of bacterial genes implicated in tryptophan and bile acid metabolism pathways[95].

Prebiotic effects of anthocyanins

-

Anthocyanins have prebiotic effects and can increase the amount of probiotics in the digestive system. These compounds can boost the production of SCFA and lactic acid in the intestines and create favorable conditions for the growth of probiotics. Additionally, anthocyanins can serve as a carbon source for probiotics and stimulate the production of bacteriocins, which enhances the ability of probiotics to compete against harmful bacteria in the gut[96].

The mechanisms of inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria by anthocyanins are as follows: (1) Preventing the expression of genes of harmful bacteria: Anthocyanins prevent the expression of certain genes in harmful bacteria. As a result, these bacteria cannot naturally produce toxins and thus lose the ability to harm humans[97]. (2) Destroying the cell structure of bacteria: Anthocyanins destroy the cell structure of harmful bacteria. This destruction causes the leakage of internal contents such as sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), protein, and nucleic acid from the cell, and finally, the bacteria are destroyed[98]. (3) Interference with the synthesis of vital enzymes: Anthocyanins interfere with the synthesis of enzymes that are necessary for the growth of harmful bacteria. Since many of the vital reactions of bacteria are catalyzed by these enzymes, the failure of these enzymes causes the death of the bacteria[99]. (4) Interfering with the energy production of bacteria: Energy is essential for life and the normal functioning of bacteria. By disrupting the energy production process in harmful bacteria, anthocyanins make these bacteria unable to grow normally and eventually die. These mechanisms together make anthocyanins play an important role in preventing the growth of harmful bacteria[100].

Lacombe et al. studied changes in the gut microflora in rat-fed blueberry anthocyanins[100]. The results showed that an anthocyanin-rich diet significantly increased the abundance of bifidobacterium and Coriobacteriae in the colon of rats. In another experiment, co-cultivation of malic glycoside with human feces showed that the number of bacteria, especially bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, increased significantly within 24 h. These findings indicate that anthocyanins can have positive effects on the population of beneficial intestinal bacteria. Sun et al. reported that peonidin-based anthocyanin monomers from the Chinese purple sweet potato cultivar (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. increased the abundance of Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Bifidobacterium infantis, and Lactobacillus acidophilus. These compounds also inhibited the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella typhimurium in culture medium[101]. They illustrated that anthocyanin could potentially have a prebiotic-like activity to modulate gut microbiota. In an in vitro experiment, it was observed that malvidin-3-glucoside in the presence of fecal slurry increased the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. but did not affect the growth of Bacteroides spp. Interestingly, when malvidin-3-glucoside was combined with other anthocyanins, the combination was able to synergistically stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria. Gallic acid, one of the metabolites of anthocyanins, has also been shown to reduce the growth of harmful bacteria such as Hathewaya histolytica without negatively affecting beneficial bacteria. In addition, gallic acid significantly reduced the abundance of Bacteroides while increasing the total bacterial count and the abundance of Atopobium species[54]. The potential of anthocyanins to increase beneficial bacteria in the gut can also play a role in reducing environmental hazards. Chen et al. showed that following the consumption of PS and C3G, differences in the shape of gut bacteria and enrichment of functional pathways were observed[102]. Metabolomic analysis showed that the levels of PS in the colon and feces were highly connected with important metabolites generated from the microbiota. These compounds are linked to the control of enzymes and transporters that are involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics. These findings could provide new perspectives on the functions of gut bacterial metabolites and the protective benefits of C3G against exposure to xenobiotic PS[102].

-

Anthocyanins have been used as food colorants for decades, such as purple corn and red rice in China[103]. The demand for natural alternatives to artificial colorants has underlined the potential of anthocyanins in providing red, purple, and blue pigments in food. The increasing evidence on the benefits of anthocyanins for gut microbiota and the lack of toxicity provides yet another reason for using these compounds as anthocyanin-rich food ingredients or extracts in foods and supplements. Scientific research has been conducted on using black sorghum bran and colored wheat as potential ingredients for functional foods, but applications in the food market are scarce[51]. Anthocyanin extracts prepared from bilberry and blackcurrant with a purity of approximately 25% and powdered anthocyanin-rich berries are being sold as supplements in several markets globally. Despite promising results on the benefits of anthocyanin supplementation in the gut and overall health, the scientific evidence has not been considered sufficient for establishing a health claim on blackcurrant anthocyanins in the EU[8], in contrast with cocoa flavanols and olive oil polyphenols, which may have discouraged the food industry from developing anthocyanin-enriched functional foods thus far.

The use of anthocyanins in foods is limited by their instability in high pH and sensitivity to light and heat[103]. However, glycosylated and acylated anthocyanins have better stability in typical food pH, and their content is high in certain vegetables, such as the red or purple varieties of cabbage, carrot, potato, and radish. Anthocyanins that are more sensitive to high pH can be suitable in acidic products such as soft drinks[51]. Regulatory policies may also limit the use of anthocyanins in foods in different countries. For example, anthocyanins extracted from natural sources are classified as a food additive (E 163) in the EU[104], and their use in food is permitted in quantum satis for all foods except those listed in Commission Regulation No. 1333/2008. Some anthocyanin-rich plant foods prepared without selective extraction of anthocyanins, such as black carrot juice, can be used as ingredients (termed coloring foods) as long as they are officially recognized as foods or novel foods. In the US, extracted anthocyanins are not recognized as permitted food additives, but individual anthocyanin-rich extracts, such as grape color and grape skin extract, are approved as color additives[105], excluding a list of over 300 foods for which the use of any color additives is prohibited.

As discussed in Section "Structural diversity of anthocyanins", food processing plays a critical role in the stability and bioavailability of anthocyanins, influencing their efficacy in functional food applications. The structural sensitivity of these compounds to heat, light, and pH presents a major formulation challenge. While structural modifications such as glycosylation and acylation can improve their stability, this often occurs at the cost of reduced absorption efficiency. Developing protective strategies, such as encapsulation, selecting appropriate food matrices, or using anthocyanins in acidic products, such as those fermented with lactic acid bacteria, is essential to ensure that functional benefits are retained in commercial products.

In general, while anthocyanins hold substantial promise for both visual appeal and potential health benefits, their integration into functional food products requires a careful balance of chemical stability, processing conditions, and compliance with national food regulations. Stronger evidence from well-designed clinical trials may also be necessary to support future health claims.

-

This review highlights the central role of anthocyanins in protecting gut microbiota from environmental pollutants such as microplastics. The protective effects of these compounds, including their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and prebiotic properties, position them as powerful tools for maintaining gut health. The findings of this review suggest that incorporating anthocyanin-rich foods into the diet could be a valuable strategy for mitigating the health impacts of environmental pollutants. Public health initiatives and policies that promote the consumption of such foods, along with efforts to reduce microplastic pollution could have far-reaching benefits for population health. As environmental challenges continue to grow, natural compounds like anthocyanins offer promising avenues for protecting human health, while other measures are still required to tackle the underlying causes of microplastic pollution.

Addressing microplastic pollution, however, requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach beyond dietary strategies. Policy reforms aimed at reducing plastic production and promoting circular economy models, technological innovations such as biodegradable materials and filtration systems, and improved waste management infrastructures are all critical components. Furthermore, raising public awareness and encouraging consumer-driven action, such as reducing single-use plastics and avoiding products with microbeads, can play a pivotal role in mitigating environmental exposure. These upstream solutions, when combined with dietary interventions like anthocyanin-rich foods, offer a synergistic path toward improved health outcomes in the face of rising environmental threats[34−36].

Despite the promising health benefits of anthocyanins, several research gaps remain. The precise mechanisms by which anthocyanins exert their protective effects on gut microbiota require further elucidation, particularly in understanding the microbial species and molecular pathways involved. Additionally, challenges related to anthocyanin bioavailability must be addressed, as their absorption, metabolism, and bioactivity are influenced by structural variations, the food matrix, and individual differences in gut microbiota composition. More research is warranted for investigating the contribution of various factors, such as differences between anthocyanin molecular species, the importance of food matrix effect vs purified supplements, and potential synergy between other phytochemicals; studying poorly utilised anthocyanin-rich materials as potential and sustainable sources of anthocyanins; and extending the most promising results into animal models and clinical studies, focusing on key indicators such as gut microbiota composition, inflammatory responses, and anthocyanin metabolism. Experimental designs should account for factors including dosage, bioavailability, and individual variability in gut microbiota to ensure the translational relevance of findings. The long-term impact of anthocyanin consumption on gut microbiota and overall host health also remains an open question, necessitating longitudinal studies to evaluate sustained dietary intake and potential cumulative benefits. Continued research and innovation in these areas will be crucial for developing effective strategies to combat the health effects of pollutants and support overall well-being.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland through Seed Funding for the Finland-China Food and Health Network (FCFH) 2023, University of Eastern Finland. Koistinen VM was supported by the Lantmännen Research Foundation (Grant No. 2022H045). Babu AF received a working grant from the Finnish Cultural Foundation (Grant No. 00210224).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation: Koistinen VM, Babu AF, Shad E, Zarei I; table and figures preparation: Koistinen VM, Babu AF. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Ville M Koistinen, Ambrin Farizah Babu

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Koistinen VM, Babu AF, Shad E, Zarei I. 2025. Anthocyanins as protectors of gut microbiota: mitigating the adverse effects of microplastic-induced disruption. Food Innovation and Advances 4(2): 238−252 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0022

Anthocyanins as protectors of gut microbiota: mitigating the adverse effects of microplastic-induced disruption

- Received: 13 December 2024

- Revised: 28 April 2025

- Accepted: 20 May 2025

- Published online: 26 June 2025

Abstract: Anthocyanins, potent bioactive compounds found abundantly in berries, as well as in many other pigmented edible plants, have garnered significant attention for their health-promoting properties, particularly in relation to gut microbiota. This review focuses on the protective role of anthocyanins against gut microbiota disruption caused by microplastics, environmental pollutants that have triggered increased concerns in recent years for their impact on ecosystems and human health. By synthesizing current research, the mechanisms through which anthocyanins may exert their beneficial effects are explored, mitigating the negative health effects of microplastic ingestion. The paper also discusses the potential application of anthocyanin-rich functional foods and supplements as a strategy to preserve gut health in the face of rising environmental challenges.

-

Key words:

- Microbiota /

- Microplastics /

- Anthocyanins