-

Native to the Americas, the yellow pitaya (Selenicereus megalanthus [K. Schum. ex Vaupel] Moran) with spiny peel and white pulp is a non-climacteric exotic fruit. Also known as 'Colombian Yellow' pitaya, it belongs to the Cactaceae family and is highly valued for its sweet flavor and smooth texture[1]. The ripe fruits are ovoid with a peel covered by bracts and spines, which are easily removable[2]. The flowering period of S. megalanthus is longer than that of other species, such as Selenicereus undatus. Similarly, anthesis occurs at night, with flowers closing in the early morning, and the species is not self-pollinating[3]. Major producers of the 'Colombian Yellow' pitaya include Israel, Taiwan (China), and Colombia[4]. The phenological stages and production cycle of pitayas vary depending on the variety, cultivation practices, and edaphoclimatic conditions. Despite its attributes, S. megalanthus is less widely cultivated than the 'Israeli yellow Golden' pitaya or red-skinned pitayas.

Despite its high market value and consumer appeal, the commercial production of Selenicereus megalanthus faces several challenges. Cultivation requires specific climatic conditions and is vulnerable to pests, diseases, and postharvest losses due to the presence of spines and the need for careful handling. International demand for yellow pitaya is rising, fueled by its exotic flavor and health benefits, but production remains concentrated in a few countries[1]. In contrast to red and white-fleshed pitayas (e.g., Hylocereus polyrhizus, S. undatus), there is a clear gap in the scientific literature regarding the biochemical dynamics and physiological processes of S. megalanthus fruit development. Most available studies focus on morphometric and postharvest traits, while the integration of morphological and biochemical analyses remains limited[4]. This study addresses that gap by combining both approaches to better understand fruit quality in S. megalanthus.

During fruit development, organic matter accumulates and transforms, driven by physiological and biochemical changes that influence its sensory, nutritional, and functional appeal. Photosynthates, transported via the phloem, alter osmotic potential, causing water absorption and fruit expansion until harvest. Firmness is associated with metabolic processes and modifications in cellular components, such as membranes, pectic substances, fibrous materials, and water content, which maintain turgidity[5]. Texture is directly linked to cell wall integrity and composition, influenced by enzymes like pectinase, cellulase, and hemicellulase, which degrade structural components, such as pectin and cellulose, resulting in softening during ripening. These enzymatic processes modulate fruit firmness and are influenced by environmental factors, light exposure, water availability, cultivation practices, and developmental stages, which also affect the formation of bioactive compounds like flavonoids, betalains, and vitamin C[6]. These antioxidants contribute to cell protection against free radicals, reducing chronic disease risk. The interplay between texture and bioactive compounds is complex, as cell wall degradation enhances the release and bioavailability of these compounds, improving their accessibility to the body. Thus, both texture and antioxidant activity are shaped by enzyme-environment interactions, directly impacting the fruit's sensory and nutritional quality.

Adequate nutrient availability during development is crucial for pitaya production and quality. For instance, nitrogen is essential for initial growth, potassium aids in carbohydrate translocation and stomatal regulation[7], and phosphorus is vital for fruit formation, providing energy through ATP. These physiological processes are coordinated by cellular signaling pathways that regulate gene expression, cell differentiation, and tissue expansion, with nucleic acid synthesis playing a central role in supporting the transcriptional and replicative mechanisms required for fruit growth and development[8].

Studies have helped elucidate the metabolic mechanisms in fruits like pitaya, advancing storage and conservation techniques while paving the way for genetic improvements. Consequently, these advancements minimize quality loss, extend shelf life, and support the expansion of the international market. In this context, this unprecedented study aimed to understand the physiological and biochemical processes influencing the quality of S. megalanthus across five distinct developmental stages, analyzing physicochemical parameters, mineral composition, antioxidant activity, and cell wall-degrading enzyme action.

-

The experimental design used was a Completely Randomized Design (CRD). The experiment included three replicates for each fruit fraction (peel and pulp), with a total of ten fruits per replicate for each developmental stage, amounting to 150 fruits throughout the study.

Plant material

-

Fruits of Selenicereus megalanthus 'Colombian Yellow' were randomly harvested from a two-hectare commercial production area conducted in open field conditions at Serra da Soca farm, located in the municipality of Ingaí, Minas Gerais state, southeastern Brazil (latitude: 21°24'24'' S, longitude: 44°56'30'' W). The developmental stages were selected to represent the most distinct phases of fruit maturation based on visible external differences and quality-related patterns. At each stage, independent fruit samples were used as biological replicates to ensure data reliability. The five-year-old plants were trained on individual trellises using eucalyptus posts, with one plant per post spaced 3 m × 3 m apart.

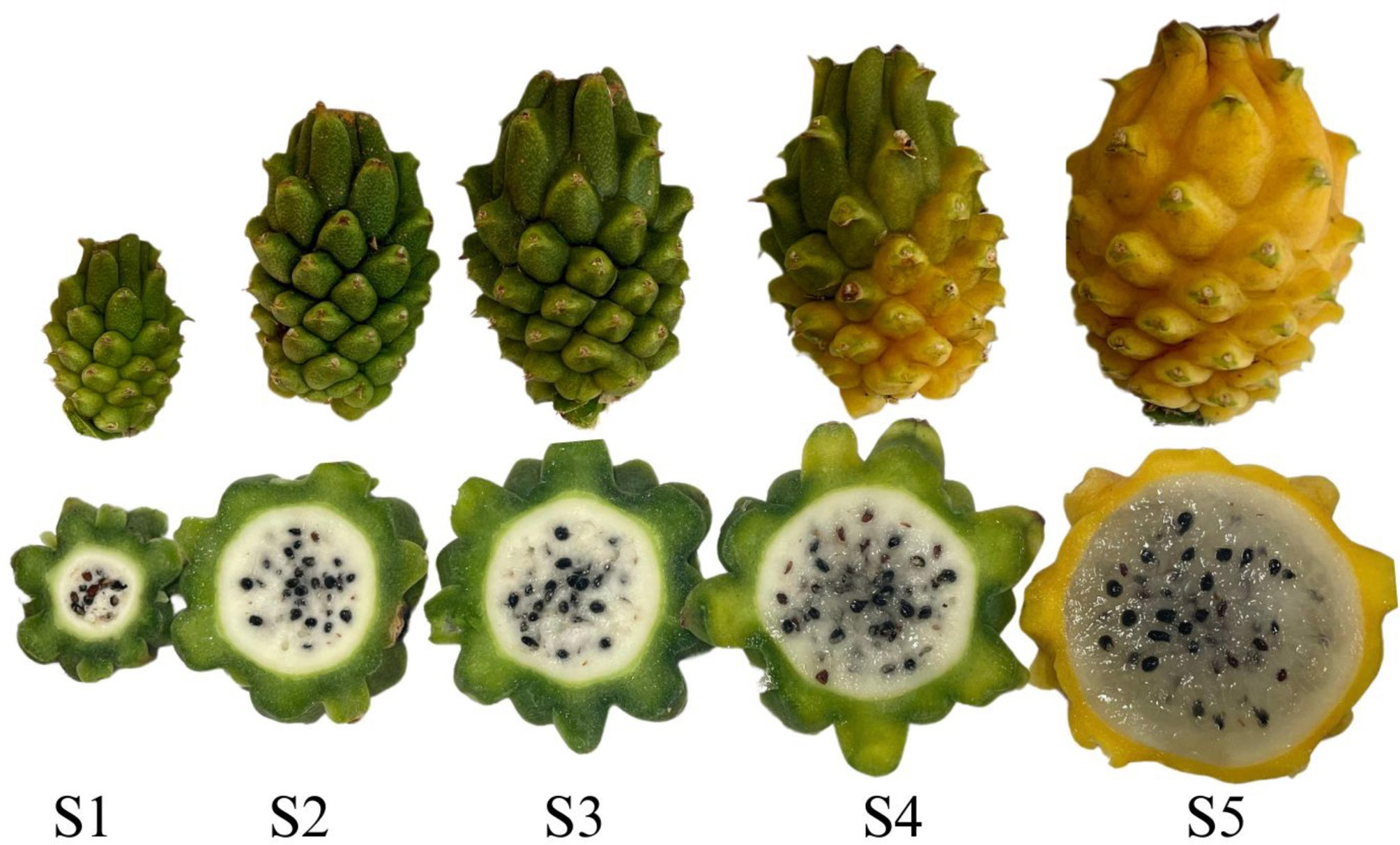

Spines were carefully removed using a brush to avoid fruit injuries. It is worth noting that spines are easily removed from ripe fruits. After harvest, the fruits were selected based on their external appearance, discarding those with signs of pathogens, parasites, or defects. The fruits were washed under running water and immersed in a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution (75 mL sodium hypochlorite in 5 L of water) for 2 min, then rinsed with distilled water to remove sanitizing residues and minimize interference in subsequent analyses. The pitayas were then air-dried and classified according to exocarp hue, measured in the equatorial region with a colorimeter (Konica Minolta CR-400, Tokyo, Japan) in the CIE color space; titratable acidity (TA,%), determined by titration with 0.1 N NaOH and phenolphthalein as indicator according to AOAC[9]; soluble solids content (SS, %), was measured in fresh, undiluted pulp using a digital refractometer (ATAGO PR-100, Tokyo, Japan) as described by AOAC[9]; dimensions (longitudinal diameter [LD] and transverse diameter [TD], in cm), obtained digitally from 1 cm scale images using ImageJ software[10]. Developmental stages (Table 1) were defined as follows: S1 – Immature 1; S2 – Immature 2; S3 – Mature green; S4 – Early ripening; S5 – Ripe (Fig. 1). For each stage, at least ten fruits were sampled. The peel fractions (mesocarp and exocarp) and pulp (endocarp) were separated using stainless steel spoons sanitized with 70% alcohol, homogenized using a domestic blender, placed in low-density polyethylene bags, and stored in an ultra-freezer at –80 °C for further analysis.

Table 1. Physicochemical characteristics of S. megalanthus fruit at five stages of development.

Code Stage Description of maturity stage* S1 Immature 1 Hue = 84.48; AT = 0.83; SS = 6.34; DL = 9.36, and

DT = 4.73S2 Immature 2 Hue = 113.72; AT = 0.64; SS = 10.3; DL = 10.53, and DT = 6.48 S3 Mature green Hue = 115.44; AT = 0.51; SS = 13.29; DL = 12.40, and DT = 7.86 S4 Early ripening Hue = 112.49; AT = 0.41; SS = 16.4; DL = 13.95, and DT = 8.61 S5 Ripe Hue = 112.31; AT = 0.28; SS = 20.4; DL = 14.15, and DT = 8.73 * Peel tone (hue), titratable acidity – TA (%), soluble solids SS (%), and fruit dimensions [longitudinal [DL] and transverse [DT]) in cm.

Figure 1.

Developmental stages of S. megalanthus pitaya. S1 – Immature 1; S2 – Immature 2; S3 – Mature green; S4 – Early ripening; S5 – Ripe.

In the first stage, immature 1 (S1), the fruit was near its initial development phase of forming fruitlets. At this stage, the endocarp, mesocarp, and exocarp formation were noticeable, with mucilage. In the second stage, called immature 2 (S2), the endocarp was more developed in size and shape, with less mucilage and seed dispersion. In the third stage, referred to as green-mature (S3), the endocarp showed an increase in overall size and volume. The exocarp coloration of the fruit became evident in the early ripening stage (S4), though still dull and lacking a uniform yellow hue on the peel, with smaller dimensions compared to the ripe stage. However, this stage was distinguished by a significant production of seeds and the characteristic more gelatinous endocarp. The peel of the fruit during the first four stages exhibited pronounced firmness and high mucilage content, which decreased throughout the developmental stages. In the final stage, referred to as ripe (S5), the peel displayed lower density, uniform yellow coloration, and a gelatinous endocarp characteristic of ripe fruit suitable for consumption (Fig. 1).

Analyses

Physical and physicochemical analyses

-

The pH of the pulp was measured using a TECNAL® pH meter, R-TEC-7-MP (Piracicaba-SP, Brazil). Fruit mass was determined using an analytical balance (Marte D330, Minas Gerais, Brazil), with results expressed in grams (g). Pulp yield was calculated as the ratio of pulp mass to total fruit mass, expressed as a percentage (%).

The color of the peel and pulp of each cultivar was assessed in the equatorial region using a Konica Minolta CR-400 colorimeter in the Commission Internationale de l'Éclairage (CIE) color space, employing the L*, a*, b* scale and chroma (C*). Firmness was measured using a Stable Micro System texture analyzer (TA.XT2i) with a 2 mm diameter probe at a test speed of 1 mm·s−1 and a penetration distance of 3 mm, with an HDP/90 platform as the base. Results are expressed in Newtons (N).

Mineral profile

-

Minerals, including phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulfur, boron, copper, manganese, zinc, and iron, were determined according to Malavolta et al.[11]. Macronutrient results were expressed in g·kg−1 fresh mass, and micronutrient results in mg·kg−1 fresh mass. Daily values based on a 2,000 kcal diet (8,400 kJ) were calculated according to IN 75/2020 (% DV).

Antioxidant activity and total phenolic compounds

-

For bioactive compound extraction, 2 g of samples were homogenized with 20 mL of 50% methanol and subjected to an ultrasonic bath (Dubdmoff Orbital Bath, NT 230, Brazil) for 30 min. The homogenate was then centrifuged (Hettich Rotina 380R, Germany) for 15 min and filtered through quantitative filter paper (12.5 cm diameter, 0.025 mm porosity). A second extraction was performed using 20 mL of 50% acetone on the filter residue, following the same procedure. Both extracts were combined for analysis.

Antioxidant activity was determined using two methods: the β-carotene/linoleic acid system (% protection)[12] and the phosphomolybdenum complex (mg ascorbic acid g−1 sample)[13]. Total phenolics (TPC) were determined using the Fast Blue method[14], with results expressed in mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 100 g of fresh sample. Measurements were performed spectrophotometrically using a microplate reader (EZ Read 2000, Biochrom®).

Cell wall enzyme activity

-

For enzyme extract preparation, 10 g of frozen tissue was homogenized with 10 mL of 50 mmol·L−1 Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) and centrifuged at 12,000 × g relative centrifugal force at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant (crude extract) was stored at 4 °C until analysis. Protein content in the enzyme extract, used to calculate enzymatic activities, was determined according to the Bradford method[15].

Pectin methylesterase (PME) activity was measured following Verma et al.[16], with modifications by Wang et al.[17]. Results were expressed as one unit of enzymatic activity (U), defined as the amount of enzyme needed to release 1 μmol of carboxylic groups per hour per gram of protein (U·g−1 protein). Activities of β-galactosidase (β-gal), cellulase (Cx), and polygalacturonase (PG) were determined following Wang et al.[17], with adaptations by Carvalho do Lago et al.[18].

For β-gal, 75 μL of acetate buffer (pH 5.5) with 0.5% p-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside was added to 75 μL of enzyme extract, incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and stopped with 150 μL of 0.2 mol·L−1 Na2CO3 solution. Absorbance was read at 400 nm. Cx and PG activities followed similar protocols, using carboxymethylcellulose and polygalacturonic acid as substrates, with appropriate standard curves (glucose and galacturonic acid).

Ultrastructural analysis

-

For cell wall morphological analysis, exocarp sections were removed with a scalpel and placed in microtubes containing modified Karnovsky's fixative. Samples were fractured in liquid nitrogen, dehydrated in an acetone gradient, dried using a critical point dryer (Bal-Tec), gold-coated with a sputter coater (Bal-Tec), and observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; LEO EVO 40 XVP).

Statistical analysis

-

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with means compared by Tukey's test at a 5% significance level, using Sisvar software version 5.6. Correlation analysis with hierarchical clustering and heatmap visualization of correlation coefficients was performed using JMP 10 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., USA).

-

The results presented in Table 2 indicate significant changes (p < 0.05) in the morphological, respiratory activity, physical, and physicochemical characteristics of S. megalanthus fruits throughout their development.

Table 2. Morphological and physicochemical characteristics: pH, L, C, °hue; mass (g); fruit yield (%); L, C, °hue; firmness (N); longitudinal and transverse diameters; and exocarp thickness (cm) of S. megalanthus fruits.

Stadium* S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 VC (%) pH 3.05e** 3.49d 3.70c 4.04b 4.67a 2.01 L* (peel) 49.80a 36.82b 27.29c 29.34c 35.26b 11.09 C* (peel) 44.87a 26.11b 21.57bc 18.61cd 16.43d 13.42 L* (pulp) 70.97a 69.42a 68.75a 62.95ab 53.46b 11.61 C* (pulp) 11.34a 11.25ab 11.18ab 11.09ab 8.56a 18.67 Hue (pulp) 94.00ab 92.18b 93.01ab 95.37a 91.87b 2.98 Mass (g) 106.82e 227.13d 303.14c 387.87b 401.57a 1.24 Fruit yield (%) 31.16d 45.32c 47.42bc 50.17b 72.43a 3.08 Dimension length (cm) (pulp) 2.46d 3.42c 4.54b 4.33b 5.69a 8.01 Dimension width (cm) (pulp) 2.30c 3.44b 3.97b 4.31b 5.70a 8.70 Diameter of the exocarp (cm) 1.16a 0.99a 0.96a 0.89a 0.68a 28.62 Firmness (N) (peel) 89,41a 88,03a 80,11b 78.09b 54.45c 7.79 Firmness (N) (pulp) 4.75a 4.66a 2.88b 2.54b 2.23b 14.54 * Stadium: S1 - Immature 1; S2 – Immature 2; S3 - Mature green; S4 - Early ripening; S5 - Ripe. ** Means followed by the same letters on the same line do not differ from each other according to Tukey's test (p > 0.05), respectively. VC (%): Variance coefficient. As demonstrated in this study, there was a significant increase (p < 0.05) in the pH of S. megalanthus throughout its development. This phenomenon is commonly attributed to the reduction or increase in the concentration of hydrogen ions derived from organic acids, which are consumed during respiratory processes[19]. Similar results were reported for Hylocereus polyrhizus, with pH variations between 3.63 and 4.48 during development[20].

The acidity decreased from 0.83 (S1) to 0.28 (S5), and the soluble solids content ranged from 6% to 20%. Wanitchang et al.[21] observed that red-fleshed pitayas in Malaysia reached acidity levels below 1% and a maximum soluble solids content of 15.3% at the ripening stage occurring 28–30 d after anthesis. Cedeño et al.[22] evaluated the postharvest quality of S. undatus (Haw.). Britton & Rose[23], at three developmental stages after pollination and at full maturity, reported an acidity value of 0.60% expressed as malic acid. The acidity of S. megalanthus is directly related to its phenological characteristics and plays a crucial role in the fruit's flavor. According to Arivalagan et al.[24], titratable acidity below 1% enhances the perception of sweetness in the fruit, as lower acidity allows the sugar concentration in the pulp to stand out, contributing to a more balanced and milder flavor.

The sugar/acid ratio (also known as Brix/acid ratio) increased markedly throughout fruit development, rising from 7.6 in S1 to 72.9 in S5. This pronounced increase reflects the decrease in acidity combined with the accumulation of soluble sugars during maturation. The high sugar/acid ratio at the ripe stage is associated with enhanced sweetness and a more balanced flavor, contributing to greater consumer acceptance of S. megalanthus fruits at full maturity. The interaction between acidity and soluble solids is key to fruit acceptance, as sweetness becomes more pronounced in fruits with lower acidity. An increase in soluble solids during ripening indicates the degradation of polysaccharides into soluble sugars. Xie et al.[4] highlighted that during the development of S. megalanthus and 'Golden Israeli' pitayas, starch accumulated mainly in the early stages and converted to soluble sugars at S5, identifying six sugar components (glucose, sucrose, fructose, galactose, inositol, and sorbitol). Variations in soluble solids content depend on the ripening stage and the edaphoclimatic conditions of cultivation. Compared to ripe red-fleshed pitayas (10.21%–13.3%), yellow pitaya shows greater soluble solids variation, with S. megalanthus considered sweeter than H. polyrhizus[4].

The progressive reduction in fruit firmness observed from S1 to S5 (Table 2) was accompanied by a significant increase in soluble solids (SS), suggesting a physiological relationship between sugar accumulation and cell wall disassembly. Throughout fruit development, the hydrolysis of structural polysaccharides and starch mobilization contributes to the release of soluble sugars, which not only enhance osmotic potential and fruit expansion but also influence textural changes. These processes are closely associated with the activity of enzymes such as polygalacturonase and cellulase, which promote cell wall loosening. The marked increase in SS from 6.34% (S1) to 20.4% (S5) indicates active carbohydrate metabolism during ripening. This behavior is consistent with the progressive conversion of starch into glucose, sucrose, and fructose during pitaya development, as described by Xie et al.[4]. Additionally, fruit softening is linked to transcriptional regulators such as ethylene response factors (ERFs), which modulate genes involved in both sugar metabolism and cell wall degradation[8]. Therefore, the interplay between sugar biosynthesis and enzymatic degradation of the cell wall plays a key role in fruit softening and sensory quality in S. megalanthus.

Higher lightness (L*) was evident in the initial stage of the peel, followed by a gradual decrease until the early ripening stage (S4), a process common in many fruits. For instance, peel lightness tends to increase in yellow passion fruit, while it decreases in bananas, papayas, and pears, as also described under different ripening conditions[25]. Despite phenotypic characteristics, the color may darken during ripening due to pigment accumulation, such as betaxanthins in 'Colombian Yellow' and 'Golden Israeli' pitayas[26].

This study also revealed a decrease in fruit color intensity throughout development, with average values decreasing from 44.87 (S1) to 16.43 (S5) for the peel and from 11.34 (S1) to 8.56 (S5) for the pulp. This reduction may be related to cultivar characteristics and the proliferation of fertilized ovules, which increase seed formation enveloped in mucilage[2]. In the peel, genetic variety and environmental conditions influence this reduction[27,28].

The hue angle, associated with tonal changes, increased from 84.48 to 115.44 between the immature (S1) and ripe (S5) stages. S. megalanthus has a high betaxanthin content, which is responsible for its yellow and orange hues. During ripening, chromoplasts and their thylakoid membranes disintegrate, leading to chlorophyll degradation and the loss of green color[29]. This transition from green to yellow at S4 highlights a crucial stage for pigment changes due to chlorophyll degradation and intensified betaxanthin production, including vulgaxanthin I and II, miraxanthin I and II, portulacaxanthin, indicaxanthin, tyrosine-betaxanthin, and glutamine-betaxanthin[30,31].

A rapid increase in fruit dimensions was observed between stages S1 and S3, indicating intense growth activity during the early developmental stages. Regarding the spines, no natural detachment was observed during maturation; however, greater ease of manual removal was noted as the fruits reached more advanced stages, especially at stage S5. Variables such as fruit mass, longitudinal and transverse diameter, and fruit yield increased progressively from immature (S1) to ripe (S5) stages, with significant differences (p < 0.05): 106.2 to 401.57 g; 2.46 to 5.70 N; 2.31 to 5.71 N; and 31.11% to 72.44%, respectively. In S. megalanthus, tissue softening occurs as cell wall components like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin convert to water-soluble forms, coupled with water loss[24].

A rapid increase in fruit dimensions was observed between stages S1 and S3, indicating intense growth activity during the early developmental phases. Variables such as fruit mass, longitudinal and transverse diameter, and fruit yield increased progressively from the immature (S1) to ripe (S5) stages, with significant differences (p < 0.05): from 106.2 to 401.57 g; 2.46 to 5.70 cm; 2.31 to 5.71 cm; and 31.11% to 72.44%, respectively. In S. megalanthus, tissue softening occurs as cell wall components such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin are converted to water-soluble forms in parallel with water loss[24]. Regarding the spines, no natural detachment was observed during maturation; however, greater ease of manual removal was noted as the fruits reached more advanced stages, especially at stage S5.

Minerals confer distinctive flavor characteristics on fruits. S. megalanthus exhibited increasing concentrations of six macro minerals (P, Ca, K, Mg, S) and five microminerals (B, Cu, Mn, Zn, Fe) from S1 to S5. Potassium was most abundant in the peel (32.87–36.78 g·kg−1), followed by calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and sulfur. The pulp similarly contained higher potassium levels (5.69–8.12 g·kg−1), followed by magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, and sulfur. Potassium also plays a critical role in osmotic regulation, carbohydrate translocation, and stomatal opening and closure[7]. Calcium is essential for the formation of plant cell walls and the maintenance of fruit structural integrity[32].

Micronutrients like iron (57.72–76.98 mg·kg−1), manganese, zinc, copper, and boron also increased significantly (p < 0.05), benefiting metabolic pathways, including chlorophyll synthesis and oxidative stress protection. Although naturally found in small quantities, the set of mineral salts provides important characteristics for the flavor perception of vegetables. As noted by Serafim[33], pitaya has a considerable mineral content, including potassium, calcium, and iron, which play fundamental roles in proper bodily function[34]. In this context, increases were observed in the concentrations of six macro minerals (P, Ca, K, Mg, and S) and five microminerals (B, Cu, Mn, Zn, and Fe) during the development of S. megalanthus (S1 to S5). Potassium was the most abundant mineral in the fruit peel (32.87–36.78 g·kg−1), followed by calcium (7.23–16.29 g·kg−1), magnesium (3.61–5.21 g·kg−1), phosphorus (1.63–3.18 g·kg−1), and sulfur (1.14–2.36 g·kg−1). Similarly, higher potassium levels were found in the pulp (5.69–8.12 g·kg−1), followed by magnesium (1.74–3.02 g·kg−1), calcium (1.49–3.28 g·kg−1), phosphorus (1.40–1.97 g·kg−1), and sulfur (1.02–1.45 g·kg−1).

Micromineral content also increased significantly (p < 0.05) throughout development, with iron showing the highest concentration (57.72–76.98 mg·kg−1) in the peel of ripe fruit, followed by manganese (16.73–36.90 mg·kg−1), zinc (13.12–19.03 mg·kg−1), copper (2.16–13.43 mg·kg−1), and boron (3.20–4.69 mg·kg−1). In the pulp, iron was also the most abundant mineral (37.38–50.81 mg·kg−1), followed by zinc (17.12–45.94 mg·kg−1), manganese (2.20–7.86 mg·kg−1), and copper (0.17–2.52 mg·kg−1). Thus, in both peel and pulp fractions, the most abundant micronutrients were iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and manganese (Mn), which are crucial for various metabolic pathways.

Based on the daily values for a 2,000 kcal diet, consuming 100 g of 'Colombian Yellow' pitaya can provide approximately 28% of P, 15% of K, 13% of Ca, 35% of Mg, 2% of Cu, 26% of Mn, 11% of Zn, and 4% of Fe, according to Normative Instruction IN 75/2020 (Brazil, 2020). This rich composition offers various health benefits to consumers due to the specific functions of each mineral. Phosphorus contributes to cell growth and modification, as well as maintenance and repair[35]. Sulfur helps reduce oxidative stress, copper reduces the risk of Menkes disease[36], and manganese supports carbohydrate catabolism and vital organ maintenance[37]. Zinc aids in wound healing, protein synthesis, and immune function[38]. Therefore, consuming this fruit can be a valuable source of minerals that promote consumer health and well-being.

Table 3 presents total phenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant activity determined by the phosphomolybdenum complex (PC) and β-carotene/linoleic acid system (β-car/LA) methods for S. megalanthus, comparing peel and pulp fractions during development.

Table 3. Total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of dragon fruit S. megalanthus throughout its development.

Stadium* S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 VC (%) TPC (peel)

(mg GAE 100 g−1)139.33e** 179.39d 211.39c 304.79b 334.80a 5.43 TPC (pulp)

(mg GAE 100 g−1)101.07e 139.74d 178.88c 302.43b 347.63a 4.66 PC (peel)

(mg AA 100 g−1)568.87cb 459.68c 584.07cb 590.54b 1108.41a 14.52 PC (pulp)

(mg AA 100 g−1)345.39b 281.10c 290.83c 311.49ab 421.84a 8.41 β-car/LA (peel)

(% protection)74.08b 77.39ab 77.20ab 80.64ab 83.15a 7.33 β-car/AL (pulp)

(% protection)48.40d 71.92c 78.77cb 80.79ba 87.05a 7.97 * Stadium: S1 - Immature 1; S2 – Immature 2; S3 - Mature green; S4 - Early ripening; S5 - Ripe. ** Means followed by the same letters on the same line do not differ from each other according to Tukey's test (p > 0.05), respectively. VC (%): Variance coefficient. After the fruit forms from the ovary of the pitaya flower, the biosynthesis of various secondary metabolites occurs, including the synthesis and accumulation of phenolic compounds (PC), which are essential for the development of key derivatives involved in fruit growth[39]. PC encompasses a wide range of metabolites from the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway and performs critical roles, such as protection against oxidation, serving as natural barriers that reduce fruit vulnerability to fungal and bacterial infections, and determining fruit quality due to their anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and chronic disease risk-reducing properties[6,40].

The PC content directly impacts antioxidant characteristics and protection against biotic and abiotic stress. During S. megalanthus development, total phenolic content varied from 139.33 (S1) to 334.80 (S5) mg GAE 100 g−1 in the peel and from 101.07 (S1) to 347.63 (S5) mg GAE g−1 in the pulp. Throughout development, a possible association with tannin polymerization and a subsequent reduction in astringency in some fruits was observed[39,40].

Table 3 highlights a progressive increase in phenolic compounds in S. megalanthus peel and pulp fractions during development, indicating the accumulation of phenolic compounds, presenting a complex metabolic response possibly associated with environmental adaptations or fruit-specific developmental demands[19,40,41]. The values found in this study are lower than those reported by Zitha et al.[6] for the pulp of red pitaya (H. polyrhizus), which ranged from 377.59 to 434.26 mg GAE g−1 during 42 d post-anthesis. However, those authors also reported increased antioxidant activity and total phenolics using different methods. PC composition can vary due to analytical validation, cultivars, and cultivation practices.

Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content (TPC) varied significantly (p < 0.05) due to the interaction between fruit fraction and developmental stage (Fig. 2). Results showed protection ranging from 74.08% (S1) to 83.15% (S5) in the peel fraction and from 48.40% (S1) to 87.05% (S5) in the pulp fraction, concerning free radical inhibition during linoleic acid peroxidation, as detected by the β-carotene/linoleic acid method. Antioxidant activity measured by the phosphomolybdenum complex method also increased significantly (p < 0.05) during S. megalanthus development, from 568.87 mg·100 g−1 (S1) to 1,108.41 mg·100 g−1 (S5) in the peel and from 345.39 mg·100 g−1 (S1) to 421.84 mg·100 g−1 (S5) in the pulp.

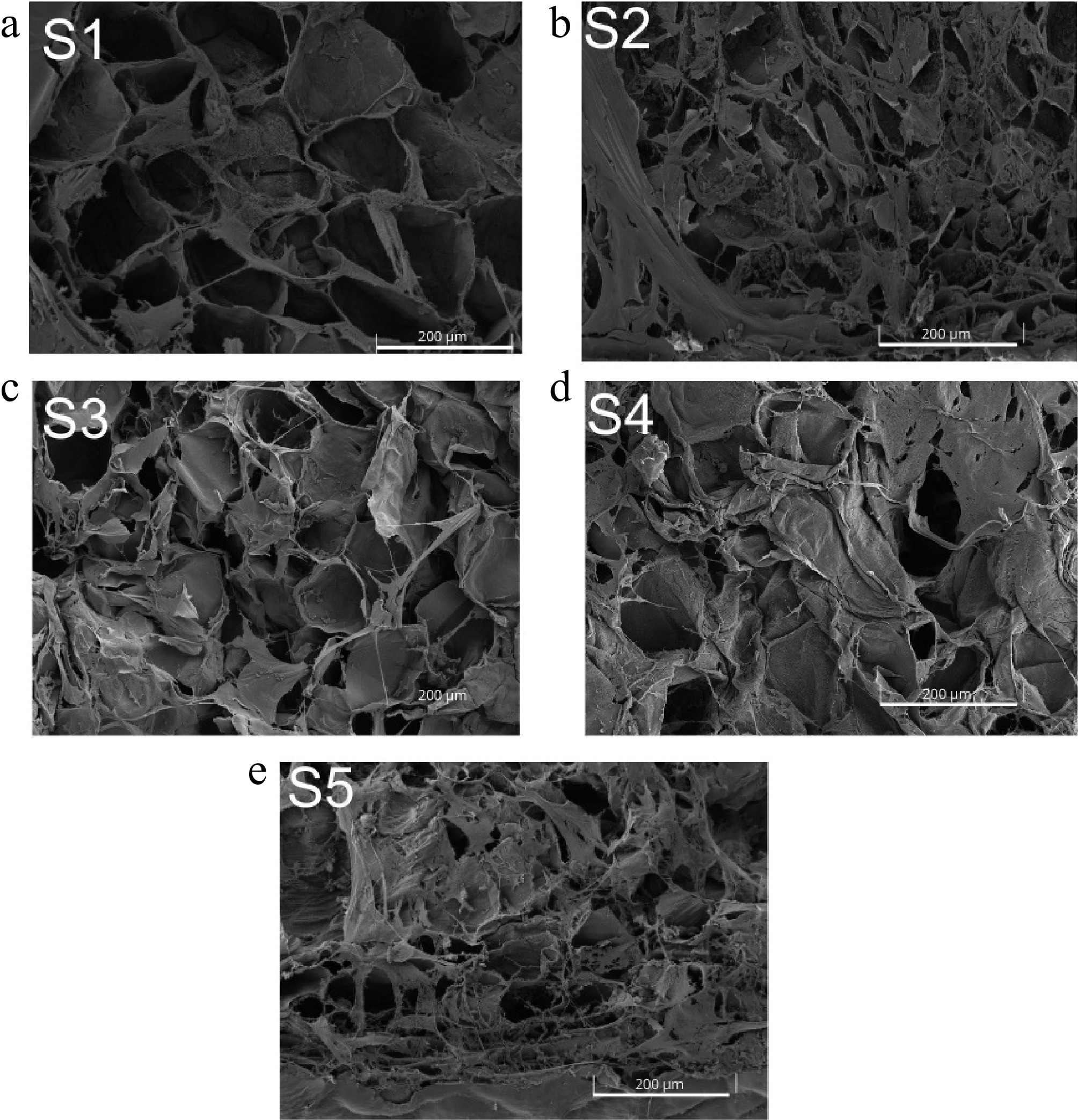

Figure 2.

Micrographs of the cell wall of S. megalanthus peel at different pitaya developmental stages. Stages: S1 - Immature 1; S2 - Immature 2; S3 - Mature green; S4 - Early ripening; S5 - Ripe.

This study reveals that S. megalanthus can be considered a fruit with high antioxidant activity using the β-carotene/linoleic acid method, as it exhibits a protective capacity above 70%[12,42]. Additionally, using the phosphomolybdenum complex method, based on molybdenum ion reduction to its oxidation state[43], the fruit demonstrates high antioxidant activity. The higher antioxidant activity in the peel observed with both methods can be attributed in part to the synthesis of betaxanthins, which, besides imparting the characteristic yellow color of pitayas, have antioxidant properties[4].

The micrographs obtained through Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provide visual insights into the structural modifications of the plant cell wall resulting from enzymatic degradation of the polymeric polysaccharide networks.

Enzymes such as β-gal, Cx, PME, and PG play central roles in degrading cell wall components[17], all of which showed activity throughout the development of S. megalanthus (Table 4). β-gal plays a critical role in cell wall biochemistry as a glycosidase, specifically hydrolyzing sugars linked to galactose residues in polysaccharides, hemicelluloses, and pectin[40].

Table 4. Activity of cell wall-modifying enzymes in S. megalanthus fruit during development.

Stadium S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 VC (%) β-gal (U·g−1 protein) 0.0015a 0.0008a 0.0011a 0.00142a 0.00085a 12.35 Cx (U·g−1 protein) 0.0100b 0.0047b 0.0068b 0.0606ab 0.0923a 13.09 PME (U·g−1 protein) 0.0046b 0.0096b 0.7466a 0.0300ab 0.0110b 11.46 PG (U·g−1 protein) 0.0294c 0.0784b 0.0876b 0.1551a 0.1393a 15.92 * Stadium: S1 - Immature 1; S2 – Immature 2; S3 - Ripe green; S4 - Beginning of ripening; S5 - Ripe. ** Means followed by the same letters on the same line do not differ from each other according to Tukey's test (p > 0.05), respectively. VC (%): Variance coefficient. Cx contributes to tissue softening by breaking cellulose fibers, enhancing fruit texture flexibility[42]. Cx activity ranged from 0.01 to 0.068 U·g−1 protein (p < 0.05), resulting in juicier and less fibrous pitayas. The PME activity increased significantly throughout fruit development, ranging from 0.0046 U·g−1 protein (S1) to 0.0743 U·g−1 protein (S3).

PG exhibited the highest enzymatic activity among the analyzed enzymes, increasing from 0.0294 U·g−1 protein (S1) to 0.1551 U·g−1 protein (S4), then decreasing slightly in ripe fruit (0.1393 U·g−1 protein, S5). The S1 stage (Fig. 2a) showed well-defined and regular cell wall structures with a higher degree of integrity preservation compared to later stages. As development progressed, irregularity in cell shape and vacuole rupture intensified, culminating in significant deformation and wrinkling in S5.

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between the physical, physicochemical, and biochemical variables of S. megalanthus throughout its development (Supplementary Tables S1–S3). Consistent with previous studies on red (Hylocereus polyrhizus) and white-fleshed (Selenicereus undatus) dragon fruit[6,20,43], the results of this study reinforce the potential use of external color as an indicator of fruit maturity and quality. A strong correlation was observed between peel lightness (L*) and chroma (C*), confirming that darker fruits exhibit more intense coloration. Similarly, the transition to a ripe peel color (yellow) was associated with an increase in soluble solids, pH, and yield, supporting the reliability of external color parameters in assessing fruit ripeness. Unlike Magalhães et al.[43], who found no significant correlations between chroma in the scales and physicochemical properties, this study identified a positive correlation between peel and pulp chroma, emphasizing the close link between external and internal color attributes during fruit development.

Beyond external color relationships, fruit mass showed a highly significant correlation with longitudinal and transverse diameters, suggesting proportional growth throughout development. The strong correlation between fruit length, dimensions, and exocarp diameter is consistent with previous findings in red-fleshed dragon fruit[44], where fruit length growth initially outpaced diameter expansion, resulting in an oblong shape early in development before transitioning to a more rounded form at full maturity. Additionally, a strong negative correlation between soluble solids and titratable acidity highlighted the sugar-acid balance during ripening, reinforcing its role as a key quality parameter. Both longitudinal and transverse diameters exhibited positive correlations with soluble solids, suggesting that fruit enlargement is accompanied by increased sugar accumulation, a finding that aligns with previous reports on dragon fruit maturity indices.

This study extends previous research by integrating mineral composition and enzymatic activity, revealing novel correlations that help explain fruit development at a biochemical level. Positive correlations between minerals such as calcium and magnesium and enzymatic activities involved in cell wall modification suggest a coordinated physiological process that influences both fruit structure and biochemical composition. In particular, polygalacturonase (PG) activity showed a strong correlation with fruit size, indicating its key role in cell wall remodeling and fruit expansion. Similarly, cellulase activity correlated with potassium and copper, suggesting that nutrient availability plays a role in textural modifications. These physiological interactions were also reflected in the firmness measurements performed for both pulp and peel fractions. These findings highlight that fruit softening is not solely governed by sugar-acid dynamics but also by enzymatic regulation and mineral interactions.

Additionally, it was found that total phenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant activity were strongly correlated with fruit mass, suggesting that larger fruits contain higher concentrations of bioactive compounds. This is a significant finding, as it links fruit size not only to yield potential but also to its functional and nutritional value, an aspect not extensively discussed in previous studies. The observed correlations between titratable acidity and fruit dimensions further reinforce the idea that fruit maturation involves a well-regulated interplay of physicochemical changes, supporting the use of external parameters as reliable indicators of internal quality. Taken together, these findings expand the understanding of S. megalanthus fruit development by providing a multidisciplinary perspective that integrates physical, chemical, and biochemical processes. In addition to its edible pulp, non-conventional parts of the fruit have also shown potential for use in food products, supporting sustainability and nutritional enhancement[45].

It is important to note that environmental factors such as temperature and humidity were not strictly controlled during fruit development, as the study was conducted under field conditions. In addition, seasonal variations may influence fruit composition and quality traits. Therefore, the results presented here should be interpreted within the context of these potential environmental influences.

-

In summary, the biochemical and morphological changes observed throughout the development of S. megalanthus fruits provide valuable information for optimizing harvest and postharvest handling. Harvesting at the ripe stage (S5), characterized by uniform yellow peel, high soluble solids, and reduced firmness, is recommended to maximize sweetness and consumer acceptance for fresh consumption. These findings can guide growers in selecting the optimal harvest point and add value to yellow pitaya as an exotic fruit. Future research should include sensory evaluation to directly link fruit development to consumer preferences, as well as transcriptomic studies to better understand the relationship between biochemical changes and gene expression during ripening.

The authors would like to thank the Electron Microscopy and Ultrastructural Analysis Laboratory of the Federal University of Lavras for technical support for experiments. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: da Silva LGM, Carvalho EEN, de Barros Vilas Boas EV; data collection: da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR; analysis and interpretation of results: da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR, de Souza LR, Santos IA, Lacerda VR, Carvalho EEN; draft manuscript preparation: da Silva LGM, de Abreu DJM, Pio LAS, Carvalho EEN. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Pearson correlation matrix based on the physical and physicochemical variables of S. megalanthus dragon fruit throughout its development.

- Supplementary Table S2 Pearson correlation matrix based on minerals, total phenolics, antioxidant activity, cell wall-modifying enzymes, firmness, and peel thickness, and the dimensions and mass of S. megalanthus dragon fruit throughout its development.

- Supplementary Table S3 Pearson correlation matrix based on the physical and physicochemical variables, minerals, total phenolics, and antioxidant activity of the pulp of S. megalanthus dragon fruit throughout its development.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR, de Souza LR, Santos IA, Lacerda VR, et al. 2025. Morphological and biochemical changes during fruit development in Selenicereus megalanthus. Technology in Horticulture 5: e030 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0026

Morphological and biochemical changes during fruit development in Selenicereus megalanthus

- Received: 10 March 2025

- Revised: 07 May 2025

- Accepted: 04 June 2025

- Published online: 08 August 2025

Abstract: The 'Colombian Yellow' pitaya (Selenicereus megalanthus) is a crop of growing commercial interest due to its high nutritional value. However, its cultivation faces challenges related to climatic and specific growing conditions that can affect fruit development. This study evaluated the morphological, biochemical, and structural changes in the peel and pulp of yellow pitaya throughout five development stages (S1–S5). Analyses included physical and physicochemical parameters, antioxidant activity (β-carotene/linoleic acid system and the phosphomolybdenum complex), phenolics (Fast Blue method), total minerals, and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Results showed significant growth in fruit dimensions and mass from S1 to S5, with longitudinal and transverse diameters increasing from 9.36 to 14.15 cm and 4.73 to 8.73 cm, respectively, and mass rising from 106.2 to 401.57 g. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant levels also increased. Phosphorus (P) was the most abundant macro mineral, followed by potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and sulfur (S). Iron (Fe) was the most prevalent micromineral, followed by zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), and boron (B). Enzymatic activities related to cell wall modification, such as pectinmethylesterase, polygalacturonase, and cellulase, peaked at different stages, contributing to fruit softening and cavity flaccidity. The fruit's versatility and nutritional properties position it as a valuable option in the exotic fruit market, offering functional and health benefits. This study provides insights into the developmental changes that influence its quality and potential market value.

-

Key words:

- Selenicereus megalanthus /

- Fruit development /

- Morphological changes /

- Biochemical composition /

- Pitaya