-

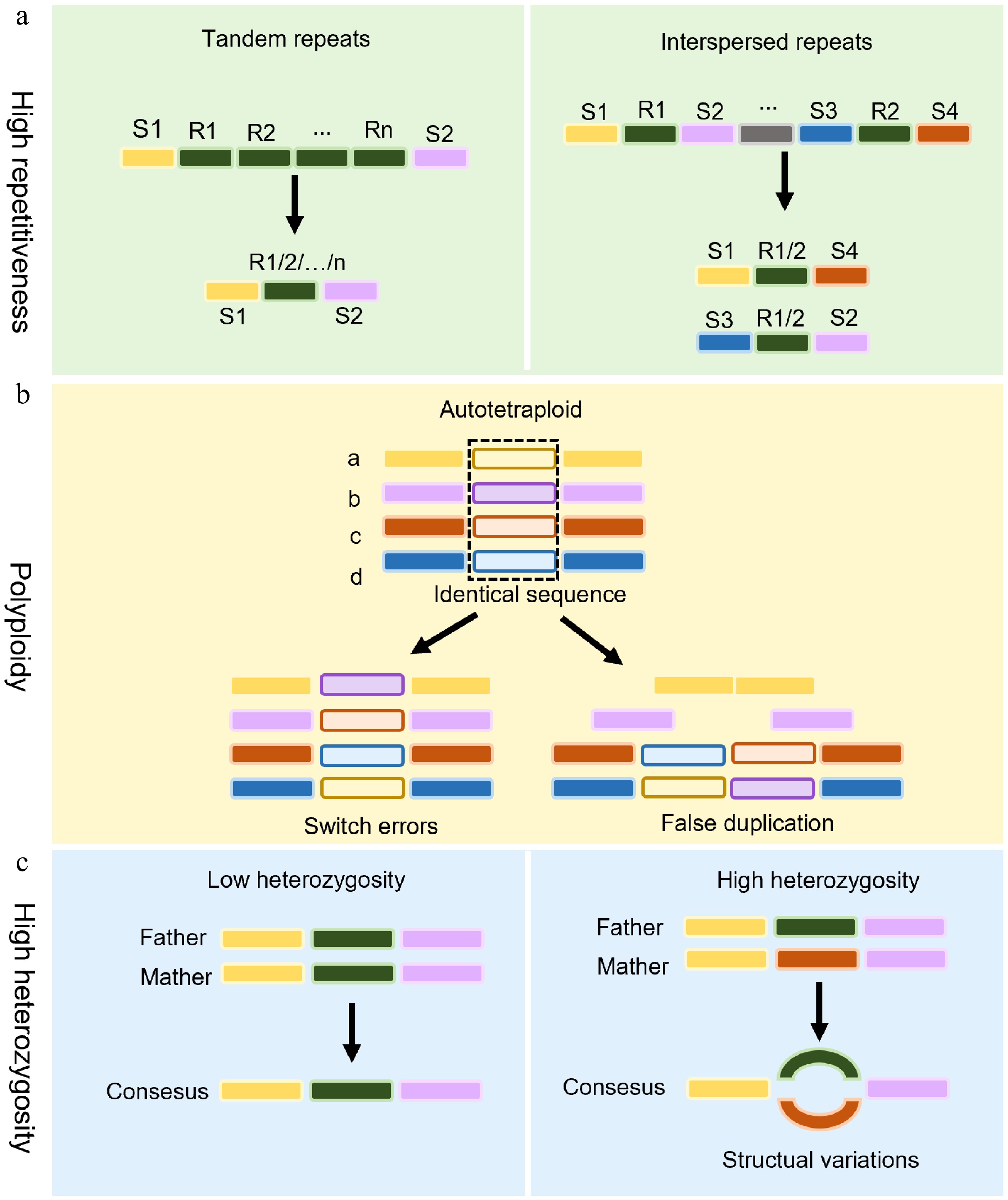

Figure 1.

Challenges in the assembly of medicinal plant genomes. (a) The assembly of highly repetitive sequences. Highly repetitive sequences (e.g., tandem repeats or interspersed transposons) pose significant hurdles in genome assembly. Unique sequences (S1–S4) are interspersed with identical repeats (R1–Rn), which confuse assembly algorithms and lead to fragmentation or misalignment. (b) Challenges facing polyploid genome assembly in medicinal plants. Polyploidy in medicinal plants introduces assembly errors. Switch errors: Misalignment between homologous chromosomes leads to incorrect sequence joins. False duplications: Assembly tools may misinterpret identical gene copies as novel duplicates, inflating gene count estimates. (c) The impact of high heterozygosity on genome assembly. Left panel: A low-heterozygosity genome assembles into a linear consensus sequence through colinear alignment of homologous chromosomes. Right panel: Elevated heterozygosity induces divergent haplotype branching, manifesting as bubble structures in assembly graphs due to persistent haplotype ambiguity at polymorphic loci.

-

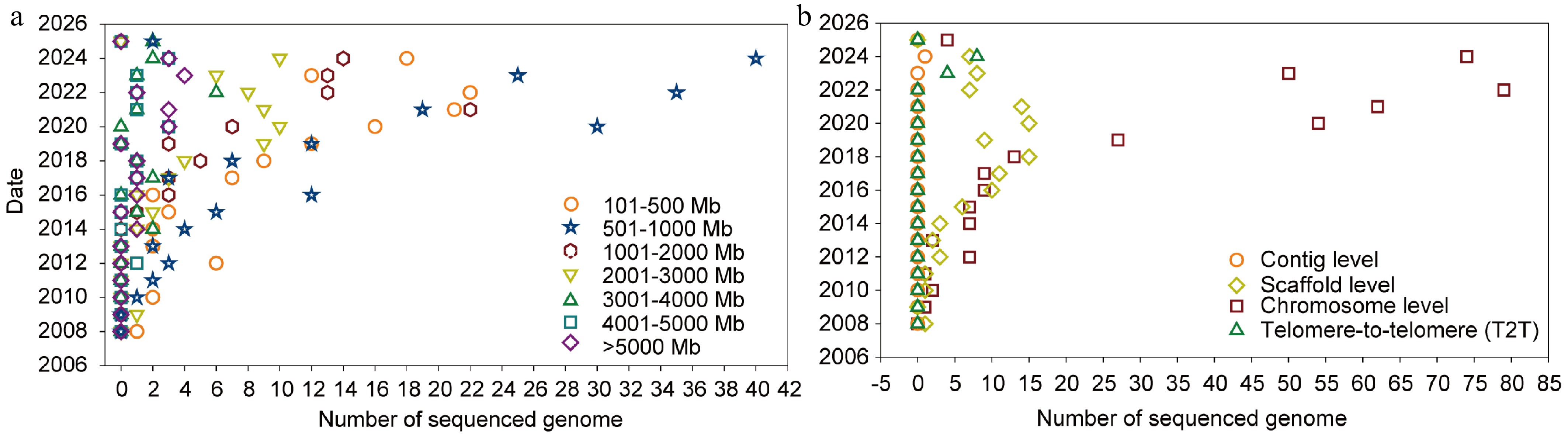

Figure 2.

Sequenced genomes of medicinal plant species. (a) Genome size range of sequenced medicinal plant species. Dots of different shapes represent distinct genome size ranges (circle = 101–500 Mb, triangle = 500 Mb–1 Gb, hexagon = 1–2 Gb, inverted triangle = 2–3 Gb, triangle = 3–4 Gb, square = 4–5 Gb, rhombus = > 5 Gb). The plot highlights the wide variation in genome size among medicinal species. (b) Assembly level of sequenced medicinal plant species. Different dot shapes represent different assembly levels: Circles represent the contig level, rhombuses represent the scaffold level, squares represent the chromosome level, and triangles represent the telomere-to-telomere level.

-

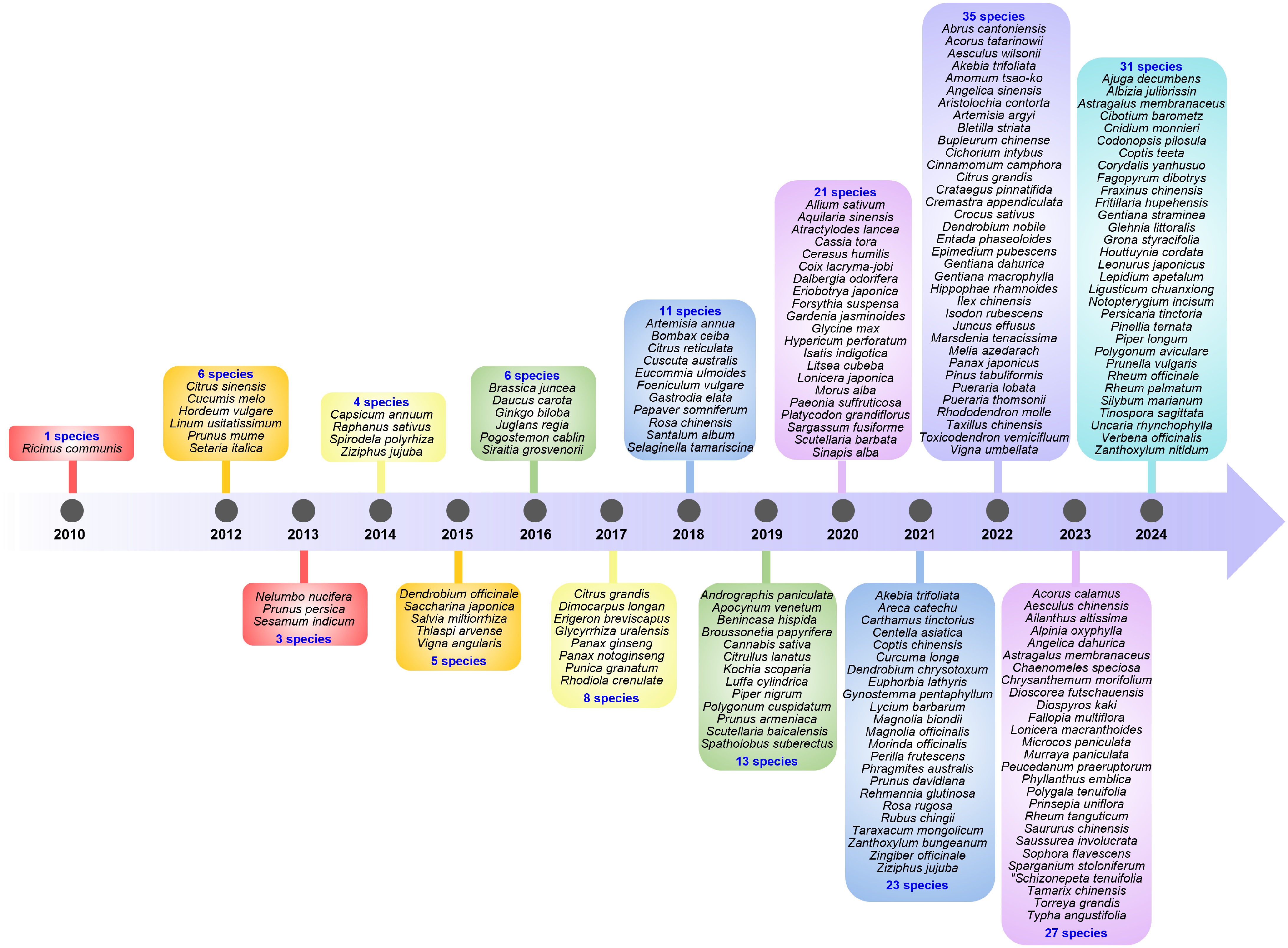

Figure 3.

Chronology of the first published genomes of medicinal plant species listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. The first sequenced medicinal plant species was Ricinus communis, with its genome assembled in 2010. With the improvement in sequencing technology and the decrease in sequencing costs, the number of completed genomes has multiplied. In particular, after 2020, more than 20 species with unpublished genomes have had their genomes sequenced for the first time every year.

-

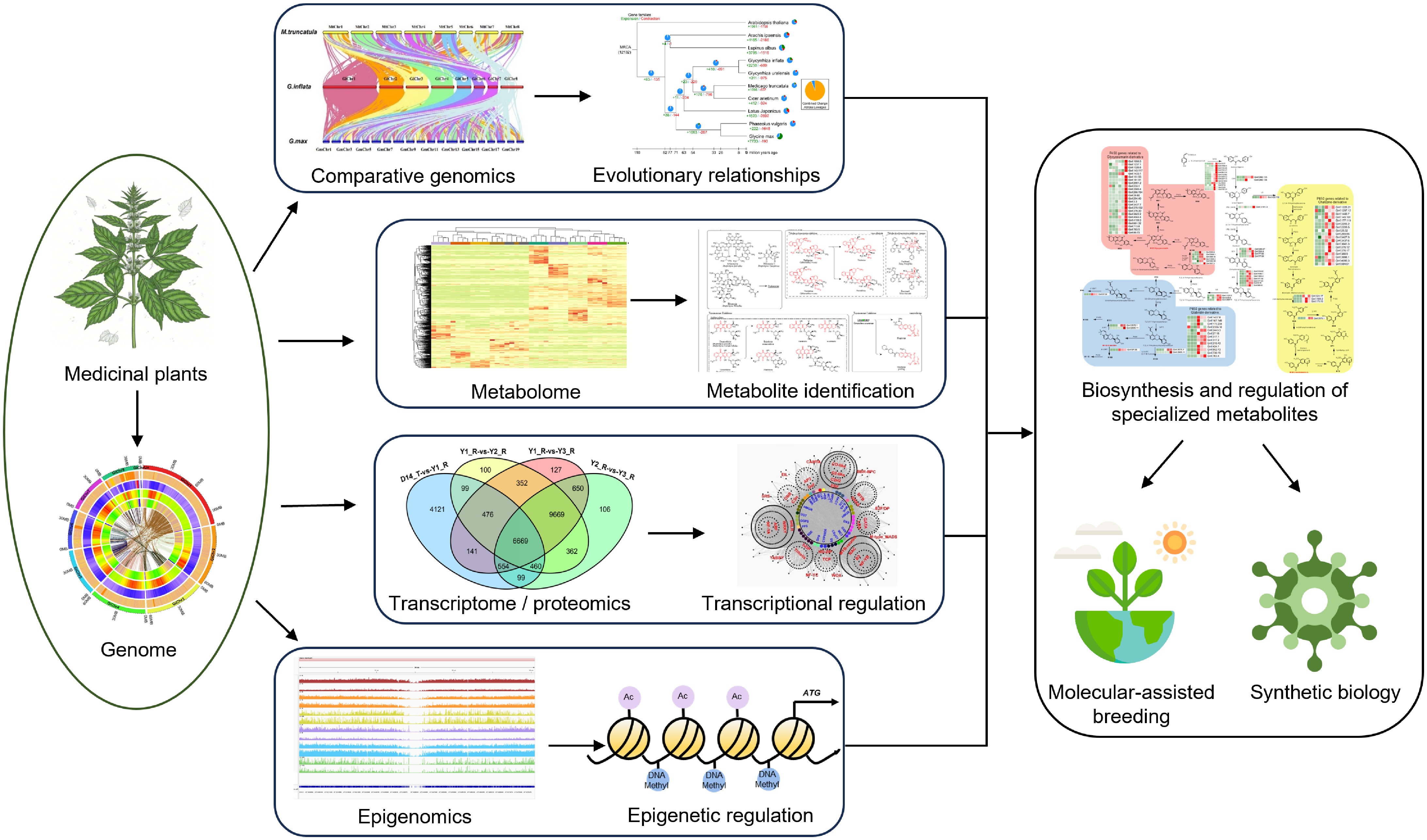

Figure 4.

Utilization of functional genomics for medicinal plant research. The illustration shows the systematic workflow used for identifying and utilizing key genes regulating secondary metabolite biosynthesis in medicinal plants through advanced functional genomic approaches. The multi-omic strategy combines genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data. Comparative genomics enables the identification of orthologous genes among species and taxa within biosynthetic pathways and the prediction of evolutionary histories. By integrating metabolic profiling with genetic analysis, the specific metabolites can be identified. Thousands of candidate loci or genes are pinpointed by metabolite genome-wide association studies (mGWAS). Functional genes involved in the same metabolites are usually co-expressed, so transcriptomics is a powerful tool for the identification of genes encoding particular enzymes and/or regulatory factors involved in secondary biosynthesis pathways via co-expression analysis. Genomic and epigenomic analyses locate gene clusters and regulatory elements. The verified candidate genes are then used for molecular-assisted breeding or synthetic biology of medicinal plants.

Figures

(4)

Tables

(0)