-

Medicinal plants with abundant specialized metabolites have long served as essential resources in traditional medicine, cosmetics, food additives, and various other industries world widely[1]. With growing evidence supporting their pharmacological benefits, these plants are receiving widespread global attention[2]. Nevertheless, their broader applications are blocked by several challenges, including low metabolite content, difficulties in species authentication, and the lack of elite germplasm resources.

Advancements in high-throughput sequencing and genome assembly technologies, driven in part by rapidly declining costs, have greatly expanded the availability of genomic resources across diverse plant taxa[3]. As a result, medicinal plants are increasingly included in functional genomics studies. High-quality reference genomes with accurate structural annotations and functional annotations are now foundational for elucidating biosynthetic pathways of specialized metabolites, dissecting adaptive traits, and enabling both molecular breeding and synthetic biology applications[4].

To fully decode the genetic mechanisms underlying the biosynthesis of metabolites, integrated multi-omic approaches combining genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics have become indispensable[5]. Among these, co-expression analysis plays a pivotal role by identifying biosynthetic gene candidates on the basis of shared expression patterns[6]. Linking gene expression data with metabolite profiles allows for more precise functional gene discovery[7].

The growing availability of multi-omic datasets not only accelerates the elucidation of biosynthetic pathways but also deepens our understanding of the evolutionary mechanisms and chemical diversity in medicinal plants. While previous reviews have primarily focused on genome assembly technologies and sequencing milestones[8], comprehensive discussions on the integration of multi-omics and functional genomic applications remain limited. This review aims to bridge that gap by summarizing recent progress in these areas, highlighting key challenges, and outlining future directions for molecular breeding. Ultimately, we seek to provide a framework that encourages broader participation in medicinal plant genome research and supports the sustainable development and utilization of their valuable resources.

-

Plant genomes act as intricate blueprints, bridging foundational genetic knowledge with practical applications in fields such as ecology, evolutionary biology, and biotechnology. While genome sequencing offers valuable insights for molecular breeding and species conservation, it consistently grapples with the universal challenges posed by plant genomes, from resolving tangled genomic repeats to deciphering noncoding regions. Within this broader context of widespread complexity, medicinal plant genomes exhibit structural and functional traits, rooted in their unique metabolic pathways and adaptive evolution, that situate them within the spectrum of challenges encountered in plant genome assembly and analysis. Here, we summarize four key characteristics of medicinal plant genomes and their associated challenges, framed within the broader complexity inherent to all plant genomic systems.

High repetitiveness

-

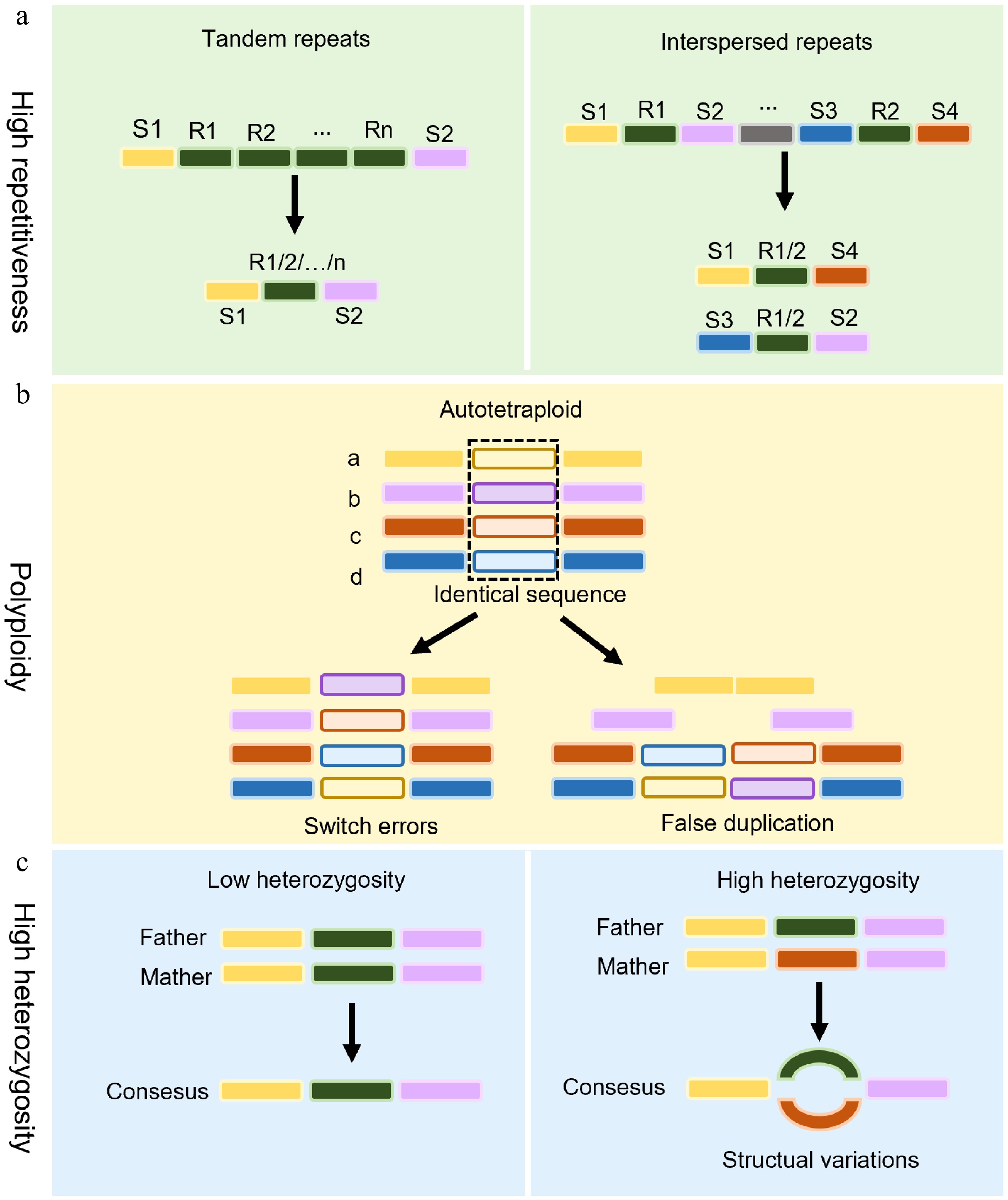

A hallmark of plant genomes is the presence of extensive repetitive DNA, which can occupy anywhere from 10% to 85% of the total genome size[9]. These repeated sequences can be categorized as either tandem duplications or interspersed repeats, depending on their arrangement within the plant genomes (Fig. 1a). Tandem duplications consist of contiguous repeat units arranged head-to-tail and are predominantly found in pericentromeric, inter-arm, or sub-telomeric regions of chromosomes. While some short tandem duplications are uniformly arranged throughout the genome, encompassing satellite DNA, ribosomal DNA, etc., in contrast, the interspersed repeats are scattered throughout the genome and largely consist of mobile elements like retrotransposons and DNA transposons, which are especially prevalent in polyploid species.

Figure 1.

Challenges in the assembly of medicinal plant genomes. (a) The assembly of highly repetitive sequences. Highly repetitive sequences (e.g., tandem repeats or interspersed transposons) pose significant hurdles in genome assembly. Unique sequences (S1–S4) are interspersed with identical repeats (R1–Rn), which confuse assembly algorithms and lead to fragmentation or misalignment. (b) Challenges facing polyploid genome assembly in medicinal plants. Polyploidy in medicinal plants introduces assembly errors. Switch errors: Misalignment between homologous chromosomes leads to incorrect sequence joins. False duplications: Assembly tools may misinterpret identical gene copies as novel duplicates, inflating gene count estimates. (c) The impact of high heterozygosity on genome assembly. Left panel: A low-heterozygosity genome assembles into a linear consensus sequence through colinear alignment of homologous chromosomes. Right panel: Elevated heterozygosity induces divergent haplotype branching, manifesting as bubble structures in assembly graphs due to persistent haplotype ambiguity at polymorphic loci.

Accurate assembly of tandem repeat-rich regions, including telomeres, centromeres, sub-telomeres, and nucleolar organizing regions (NORs), remains highly challenging[10]. These homogeneous regions are not only structural components but also influence the genome's architecture, recombination, and genome size variation. Their lengths can range from a few bps to several Mbps, as observed in species like maize[11]. Despite improvements in long-read technologies, assembling such regions remains problematic because of their uniformity and size, which often exceed current read lengths[10,12].

Polyploidy complexity

-

Many medicinal plants are polyploid, possessing multiple sets of homologous chromosomes, which greatly increases the difficulty of accurate genome assembly (Fig. 1b). Polyploid genomes, particularly those containing multiple closely related sub-genomes, make it challenging to resolve homoeologous regions because of sequence redundancy. Misassembly and fragmentation frequently occur when closely related genomic regions are misaligned. Because of high similarity between homologous chromosomes, the genome assembly of autopolyploid organisms has significantly more challenges than allopolyploid genomes[13]. Moreover, the expansion of repetitive elements in polyploids further complicates the challenge[12].

A common approach to overcome these issues is to first sequence the diploid ancestors of polyploid species, which helps to differentiate and map homoeologous sequences[14]. This strategy has been employed successfully in the genome projects of crops like wheat[15] and peanut[16]. However, for polyploid species with unknown progenitors, innovative assembly techniques and high-fidelity sequencing are essential to resolve the complexity of the genome's polyploidy[17].

High heterozygosity

-

Medicinal plant genomes always exhibit high heterozygosity as a result of outcrossing, hybridization, or self-incompatibility (Fig. 1c). It is beneficial for ecological adaptability, but makes genome assembly very difficult. Heterozygosity often results in the separation of allelic regions into distinct contigs, causing artificial genome inflation and misrepresentation of haplotypes[18]. In addition, distinguishing between highly similar alleles at the same locus can lead to improperly aligned assemblies.

To solve these problems, redundancy removal strategies are commonly used to retain a single representative haplotype[19]. The advent of tools such as Hifiasm has enabled haplotype-resolved assembly, generating phased diploid genomes[20]. Despite these advances, producing gap-free, fully resolved haplotypes in highly heterozygous genomes remains a major technical hurdle.

Extreme genome size

-

Repeated sequences and polyploidy have led to ultra-large genomes in medicinal plants. The genome size among sequenced plants varies from tens of Mb to tens of Gb across different species[21]. For example, the assembly of the tree peony genome is up to 12.28 Gb[22]. Handling such massive datasets present dual challenges in terms of both sequencing data throughput and computational resource demands. Traditional assembly algorithms often struggle with performance and scalability when dealing with ultra-large genomes. Moreover, storing and processing these enormous datasets require substantial memory, storage, and computing power. Therefore, novel algorithms and cloud-based pipelines are urgently needed to be developed to meet the growing needs for large-scale plant genome analyses.

-

Plant genome research has advanced rapidly, driven by sequencing technology progress. First-generation methods (e.g., Sanger) dominated early on, offering high base-level accuracy (used for gene sequencing and clone validation) but were limited by low throughput, high cost, and time consumption, restricting their scalability for large genomes. Second-generation (next-generation sequencing [NGS]) revolutionized the field with high throughput and cost-effectiveness, though constrained by short read lengths, GC-content bias, and difficulty in resolving complex repeats. Third-generation technologies (SMRT from Pacific Biosciences, ONT from Oxford Nanopore) ushered in a new era for complex plant genome analysis. SMRT provides long continuous reads (CLRs) of > 30 kb, with a higher error rate and high-accuracy high-fidelity (HiFi) reads (~99.9%, shorter length). ONT offers theoretically unlimited read lengths (routinely > 100–200 kb) and excels at complex/repetitive regions. Combined, HiFi and ONT enable telomere-to-telomere (T2T) assemblies[23]. Post-sequencing, raw/clean reads are assembled into contigs via de novo tools; scaffolding, notably high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C), generates chromosome-level assemblies. Hi-C uses three-dimensional (3D) chromatin interaction data to improve the assembly's contiguity, and it works well for heterozygous diploid and polyploid genomes with complex structures.

As sequencing technologies have advanced, assembly algorithms and software have evolved accordingly. To date, the overlap–layout consensus (OLC) and de Bruijn graph (DBG) strategies dominate the assembly landscape[24]. Initially, assemblers designed for first-generation sequencing data, such as Arachne, CAP3, Celera, and Newbler, predominantly employed the OLC algorithm[25]. However, because of its lower complexity and higher computational efficiency when dealing with vast numbers of NGS reads, the DBG method has become widespread in genome assembly tools, including Velvet, ABySS, AllPath-LG, and SOAPdenovo[25].

The advent of third-generation sequencing has renewed interest in the OLC strategy, which is favored for its capacity to handle long reads effectively. Assemblers, such as Canu[26], MECAT[27], and FALCON[28] are predominantly based on OLC frameworks. Meanwhile, tools like wtdbg2[29] and Flye[30] have introduced novel data frames, namely the fuzzy Bruijn graph (FBG) and repeat graph, to accommodate the high error rates of long-read sequencing. Despite these advances, both wtdbg2 and Flye face limitations when applied to complex plant genomes, particularly those with high heterozygosity or polyploidy.

The development of HiFi long reads has facilitated haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using tools such as Hifiasm[20] and HiCanu[31]. Hifiasm provides superior haplotype-resolved assemblies with high resolution, outperforming many existing assemblers in terms of phasing accuracy[32]. On the other hand, HiCanu leverages HiFi reads for genome assembly, effectively tackling complex repetitive sequences and centromeres, and enhancing genome continuity, accuracy, and haplotype detection[33]. Collectively, these advances have markedly increased the production of chromosome-level assemblies, supporting the reconstruction of genomes with greater size and structural complexity.

Overview of genome-sequenced medicinal plant species in various pharmacopoeias

-

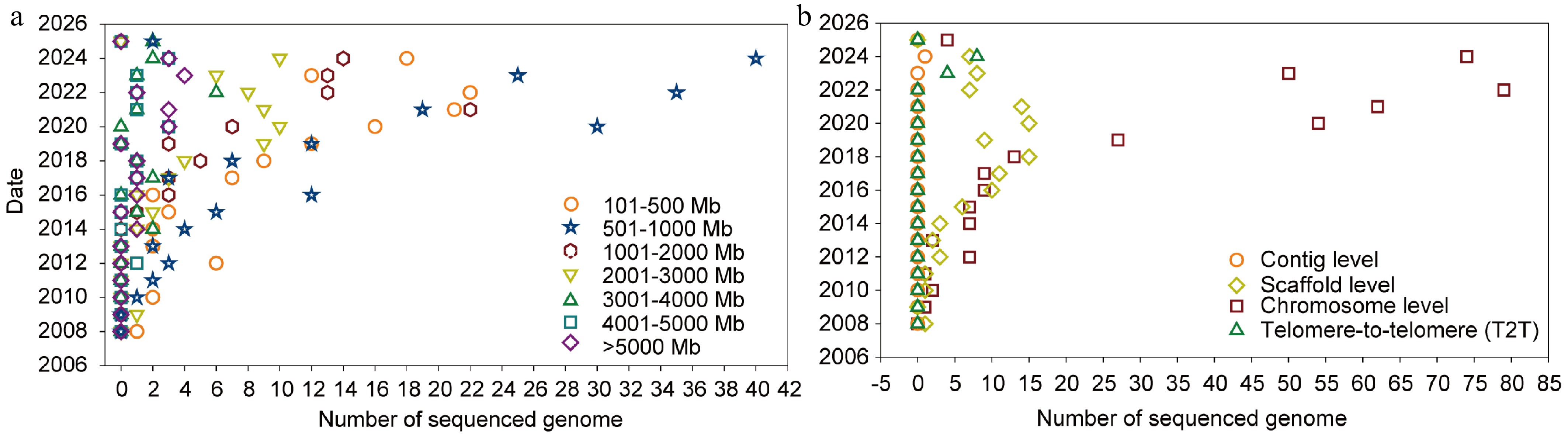

A high-quality reference genome assembly is the cornerstone of genetic research on plant domestication and improvement. The first published medicinal plant genome, Carica papaya, paved the way for integrating modern life sciences with traditional medicinal plant research[34]. According to the medicinal plants recorded in the Brazilian, Egyptian, European, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and US Pharmacopoeias, 270 of 532 medicinal plant species have been sequenced as of February 2025 (Supplementary Table S1). The genome size of sequenced species ranges from 138 (Spirodela polyrhiza)[35] to 19,050 Mb (Torreya grandis)[36], with the largest number in 501–1,000 Mb (Fig. 2a). With the advancement of sequencing technology, large and complex medicinal plant genomes have been sequenced (Fig. 2a). Statistical analysis of published medicinal plant genomes revealed that 76.13% were assembled to chromosome-level completeness, whereas 20.86% were assembled at the scaffold level (Fig. 2b). This demonstrates that medicinal plant genomes can achieve high-quality assembly, furnishing critical genetic resources for further research.

Figure 2.

Sequenced genomes of medicinal plant species. (a) Genome size range of sequenced medicinal plant species. Dots of different shapes represent distinct genome size ranges (circle = 101–500 Mb, triangle = 500 Mb–1 Gb, hexagon = 1–2 Gb, inverted triangle = 2–3 Gb, triangle = 3–4 Gb, square = 4–5 Gb, rhombus = > 5 Gb). The plot highlights the wide variation in genome size among medicinal species. (b) Assembly level of sequenced medicinal plant species. Different dot shapes represent different assembly levels: Circles represent the contig level, rhombuses represent the scaffold level, squares represent the chromosome level, and triangles represent the telomere-to-telomere level.

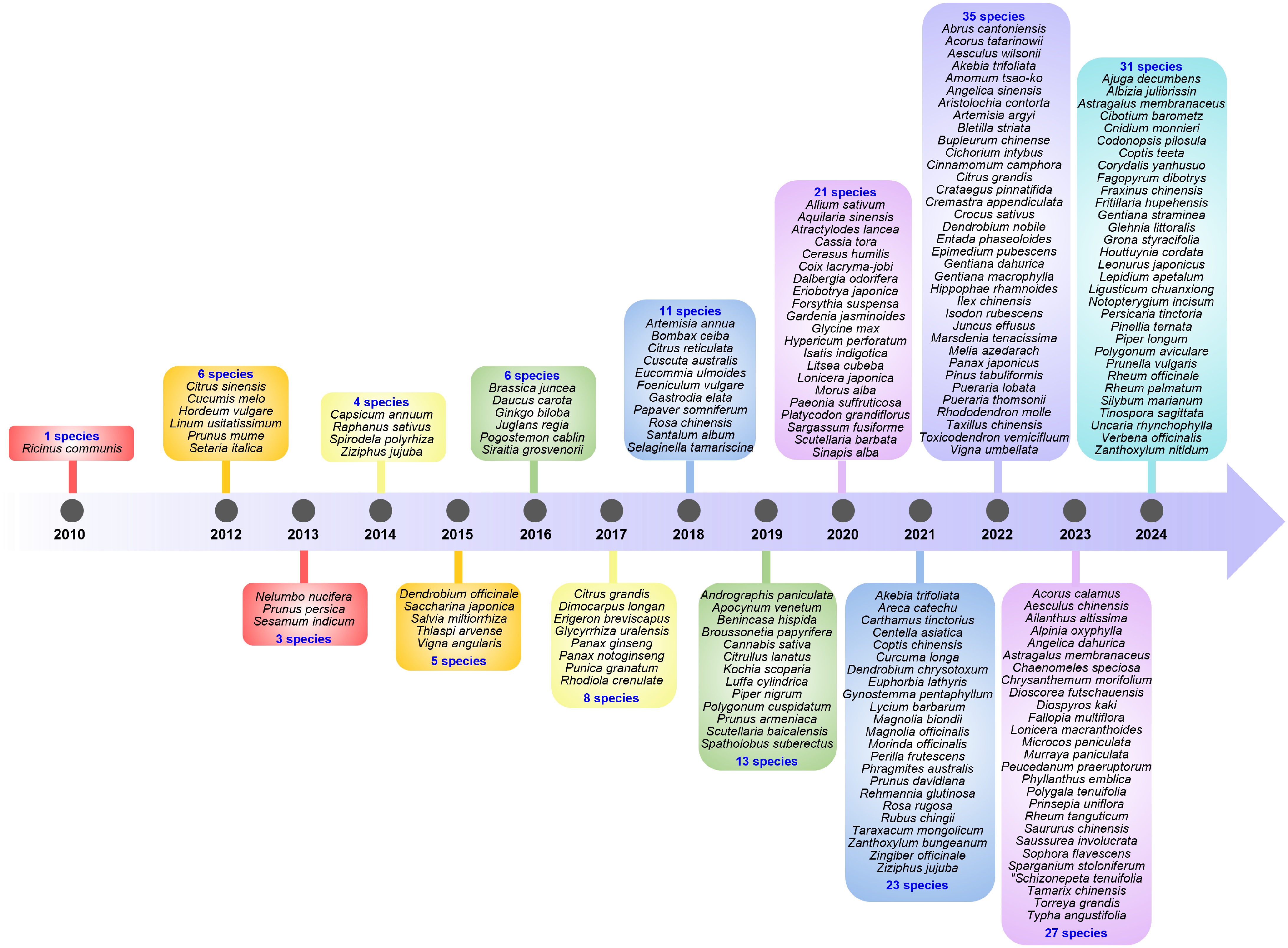

Among the medicinal plants listed in the Chinese Pharmacopie, Ricinus communis became the first species with a published genome in 2010[37]. Since then, many genomes with a small size have been sequenced. With the improvement in sequencing technologies and the declining costs, the number of completed genomes has multiplied. In particular, after 2020, more than 20 species with unpublished genomes have had their genomes sequenced for the first time every year (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Chronology of the first published genomes of medicinal plant species listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. The first sequenced medicinal plant species was Ricinus communis, with its genome assembled in 2010. With the improvement in sequencing technology and the decrease in sequencing costs, the number of completed genomes has multiplied. In particular, after 2020, more than 20 species with unpublished genomes have had their genomes sequenced for the first time every year.

Although breakthroughs have been achieved in the whole-genome sequencing of medicinal plants, our analysis reveals an alarming geographical imbalance in sequencing efforts. Specifically, our results indicate that 76.67% of sequenced medicinal plant species originate from East Asia (Supplementary Table S1), whereas genomic data for medicinal plants in regions such as Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia remain severely lacking. This imbalance likely stems from multiple factors: The uneven geographical distribution of research fundings, disparities in regional research infrastructure and technical capabilities, challenges in the areas of sample collection and cross-border cooperation, and the complexities of conservation and access to biodiversity hotspots in certain regions. Such regional bias not only impedes the development of innovative drugs from the rich, unique medicinal plant resources in these underrepresented regions but also elevates the risk of unsustainable exploitation of these resources.

Development of medicinal plant pangenomes

-

The increasing availability of multiple reference genomes has exposed the limitations of single reference genomes in representing intraspecific genetic diversity, often overlooking critical inter-species variation. The pangenome concept, referring to the collective set of all genomic information of a species, originates from microbiology and has gradually been applied to various organisms[38,39]. To date, plant pangenome research has been conducted on more than 30 species, including soybean, rice, and wheat[40,41]. These efforts have revolutionized studies of plant evolution and trait-gene discoveries. In medicinal plants, a landmark study constructed the pangenome of Cannabis sativa using 193 genomes from 156 accessions, substantially expanding its gene pool[42]. The development of plant pangenomics contributes to revealing rich genetic variations, discovering new functional genes, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying chemotype diversity, and deepening our knowledge of species' genetic diversity.

-

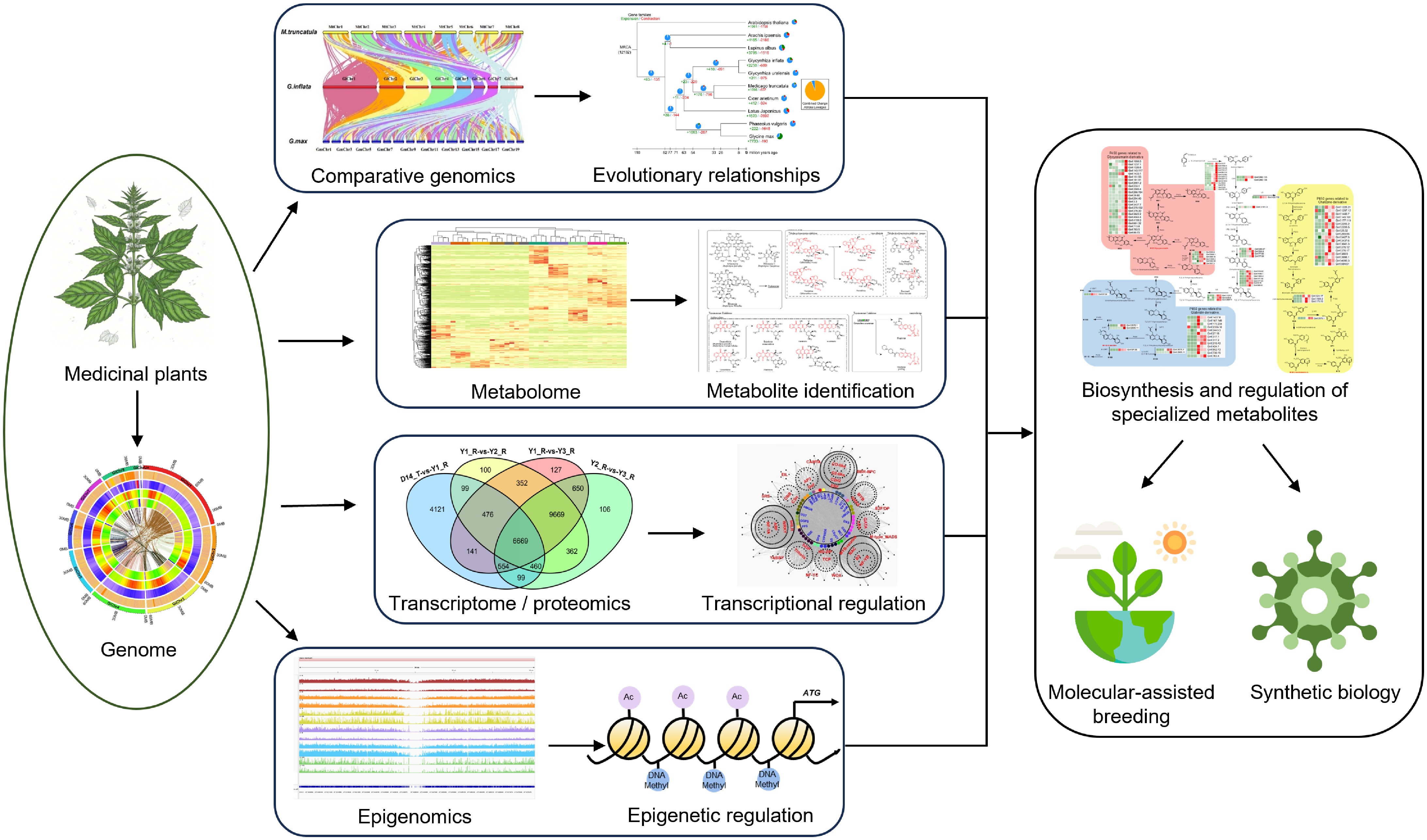

The biological processes often exhibit complexity and integrality, and the regulation of their gene expression is intricate, leading to incomplete conclusions in single omic studies. Multi-omic integration synergizes datasets from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics through cross-layer statistical analyses (normalization, comparative modeling, correlation networks) at different molecular levels and involves functional validation, bridging computational predictions with experimental evidence. This approach not only resolves complex biological networks but also accelerates the biotechnological applications of medicinal plants (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Utilization of functional genomics for medicinal plant research. The illustration shows the systematic workflow used for identifying and utilizing key genes regulating secondary metabolite biosynthesis in medicinal plants through advanced functional genomic approaches. The multi-omic strategy combines genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data. Comparative genomics enables the identification of orthologous genes among species and taxa within biosynthetic pathways and the prediction of evolutionary histories. By integrating metabolic profiling with genetic analysis, the specific metabolites can be identified. Thousands of candidate loci or genes are pinpointed by metabolite genome-wide association studies (mGWAS). Functional genes involved in the same metabolites are usually co-expressed, so transcriptomics is a powerful tool for the identification of genes encoding particular enzymes and/or regulatory factors involved in secondary biosynthesis pathways via co-expression analysis. Genomic and epigenomic analyses locate gene clusters and regulatory elements. The verified candidate genes are then used for molecular-assisted breeding or synthetic biology of medicinal plants.

Comparative genomics

-

Comparative genomics, a significant subfield within genomics, investigates the similarities and differences among various species or individuals by comparing their genomic sequences. It aids in uncovering evolutionary relationships among species, gene functions, biological adaptations, and potential disease mechanisms. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing have revolutionized comparative genomic applications in medicinal plants.

Comparative genomics can be categorized into interspecific and intraspecific analyses on the basis of their genetic relatedness[43]. The rapidly increasing availability of genomic data now allows for comprehensive comparative and phylogenetic analyses. This enables the identification of orthologous genes across species within biosynthetic pathways and allows researchers to reconstruct the evolutionary histories[44,45]. For instance, a genomic comparison between Scutellaria baicalensis and S. barbata demonstrated that the long terminal repeat sequences drive chromosomal rearrangement, while tandem duplication events diversify flavonoid biosynthesis gene families. This result provides a critical framework for investigating chemical evolution in Lamiaceae[46]. The comparative study on Lonicera macranthoides and L. japonica further illuminates their genomes' evolution and the molecular basis of hederagenin saponins[47]. A comparison of the genomes of two Artemisia annua species with different artemisinin contents identified a correlation between artemisinin content and the copy number of amorpha-4,11-diene synthase genes[4], providing new insights into the biosynthesis and regulation of artemisinin. On the basis of chromosome-level genome comparisons of Leonurus japonicus (with a high leonurine content) and Leonurus sibiricus (with a low leonurine content), the leonurine biosynthetic pathway was constructed and the key enzymes (arginine decarboxylase [ADC], uridine diphosphate glucosyltransferase [UGT], and serine carboxypeptidase-like [SCPL] acyltransferase) were identified; it was revealed that the UGT–SCPL gene cluster evolved via gene duplication in the ancestor of the genus Leonurus, with neofunctionalization of SCPL occurring in L. japonicus, thereby contributing to its specific leonurine accumulation[48]. Collectively, these analyses highlight how cross-species and within-species genomic comparisons serve as robust strategies for elucidating the evolutionary foundations of specialized metabolic pathways.

Metabolite genome-wide association studies

-

The convergence of high-throughput sequencing and metabolomics has revolutionized genetic mapping through metabolite genome-wide association studies (mGWAS) and metabolite quantitative trait loci (mQTL) analysis. By integrating metabolic profiling with genetic analysis, these approaches have identified many candidate loci or genes underlying plants' specialized metabolism[5,49]. For example, subspecies-specific diterpene biosynthetic gene clusters were identified by conducting an mGWAS using single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) derived from population sequencing[50]. Furthermore, numerous reports in other species have linked metabolic diversity to genetic architecture, showcasing similar findings[51].

In addition to SNP-genome-wide associaton studies (GWAS), structural variation GWAS (SV-GWAS) also offers insights into the natural diversity sites and evolutionary pathways of metabolites in certain species. SV-GWAS is a crucial complement to SNP-GWAS. Various studies have demonstrated SV-GWAS's ability to identify key structural variations that were not detected by SNP-GWAS, encompassing structural variations linked to different traits such as yield, flowering and seed development, and stress resilience in crops like tomato, and Brassica napus[52]. However, to date, there have been limited instances of integrating metabolomic data into these analyses, hinting at a promising direction for future research expansion in this field.

Integration of genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics

-

Transcriptome sequencing has become a cornerstone technique for transcript discovery and gene expression quantification in medicinal plants. The past decade has witnessed a transformative leap in medicinal plant transcriptomics, driven by the proliferation of high-quality genome assemblies. Structural or regulatory genes involved in the same metabolites are usually co-expressed, so transcriptomics has given a quick and affordable alternative path toward the identification of genes encoding particular enzymes and/or regulatory factors involved in secondary biosynthesis pathways through co-expression analysis[48]. At present, a large number of medicinal plant transcriptomes have been published, such as Glycyrrhiza inflata[7], Saposhnikovia divaricata[53], Artemisia annua[4], and Salvia miltiorrhiza[54]. These transcriptomic data have been used to identify structural or regulatory genes in the synthesis pathway of licochalcone A, coumarins, phenylpropanoid glucosides, and tanshinone, respectively. Chromosome-level genome assemblies now enable high-resolution transcriptomic profiling of medicinal plants, markedly accelerating the discovery of genes governing the biosynthesis of specialized metabolites[55].

Plant metabolomics—an advanced platform for metabolic profiling—has accelerated gene discovery and elucidated key natural product biosynthetic routes. A novel liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based targeted metabolomic pipeline now enables the precise quantification of both metabolites' abundance and their compositional diversity[5]. Integrating transcriptomic and metabolomic data enables dual-dimensional interrogation of biological systems, deciphering causal gene regulatory networks while simultaneously capturing resultant metabolic phenotypes. This synergistic approach not only cross-validates the findings of multi-omics but also distills key genetic determinants, metabolite signatures, and pathway hierarchies from complex datasets, thereby illuminating the molecular architecture of specialized metabolism. The convergence of high-throughput technologies now empowers unprecedented resolution in tackling fundamental biological challenges in medicinal plant research[5]. These integrative analyses span multiple biological dimensions, encompassing specialized metabolite accumulation, developmental regulation, and adaptive responses to environmental stress. For example, Xu et al. applied chromosome-level genome assembly, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), and biochemical validation to identify six critical enzymatic steps in the biosynthesis of berberine from Phellodendron amurense, encompassing methylation, hydroxylation, and berberine bridge formation. These findings provide compelling evidence for convergent evolution shaping specialized metabolic pathways in plants[56]. Two chromosome-level genome data of Rhodiola provide important insights into the evolutionary trajectory of the biosynthesis of salidroside[57]. Moreover, Lv et al. integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic profiling of Glycyrrhiza uralensis under alkaline salt stress, demonstrating that flavonoids serve as critical chemical mediators of stress resilience, and they identified the candidate genes involved in regulating flavonoid accumulation[58].

Together, these typical case studies illustrate the utility of integrated multi-omics analysis to discover metabolite-related biosynthetic pathways in medicinal plants, and these successes depend on the correlation of biosynthetic genes in plants with their respective natural products. A critical limitation emerges when metabolites undergo biosynthesis–storage uncoupling, where synthesis occurs in tissues distinct from the accumulation sites, or when the intermediates are actively transported across cellular compartments. These spatial and temporal disconnections can obscure the causal relationships between gene expression and metabolic phenotypes, undermining the predictive power of standard multi-omics integration.

Integration of genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics

-

Proteomics systematically analyzes the entire protein landscape of cells, tissues, or organisms, encompassing protein expression dynamics, post-translational modifications, and interaction networks. By integrating these multi-dimensional protein characteristics, proteomics offers a comprehensive perspective on biological processes including growth, development, and metabolic regulation[59]. The transcriptome serves as a bridge between the genome and the proteome. Compared with the transcriptome, the proteome is closer to the functional state of the organism, as proteins are the molecules that carry out the vast majority of biological functions in living organisms[60]. Transcriptomics captures the instantaneous state of genes, while proteomics showcases the final expression of genes.

At present, integrated proteomic and metabolomic analysis can explain whether alterations in metabolites stem from changes in the proteins. Additionally, it aims to swiftly pinpoint crucial proteins and uncover the associated target molecules on the basis of the protein dynamics and concomitant metabolic shifts within certain biological processes. Multi-omics integration has yielded breakthrough insights in medicinal plant research through synergistic proteomic and metabolomic analyses. For example, Jiang et al. demonstrated this approach by examining Ganoderma lucidum under methyl jasmonate treatment, where coordinated changes in protein and metabolite abundance revealed regulatory networks spanning secondary metabolism, energy pathways, and transcriptional control[61]. Similarly, the camptothecin-related biosynthetic and regulatory mechanisms of Camptotheca acuminata were revealed[62]. The power of combined metabolomics and proteomics extends to stress biology. A recent study indicated that a multi-hormone signaling network regulated flavonoid and alkaloid production to counteract ultraviolet (UV)-B and dark-induced oxidative stress in Mahonia bealei[63].

The combined analysis of transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data can be performed to further explore the relationships among genes, proteins, and metabolites, and to discover biomarkers and analyze the internal mechanism of biological and physiological processes. For instance, integrated multi-omics analyses encompassing transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have unveiled the intricate regulatory mechanisms governing tiller production in low-tillering wheat cultivars[64], flower development[65], tetracycline stress response[66], and Cd resistance and accumulation[67]. In the future, the multi-omics analysis approach will be utilized to address biological questions in medicinal plants.

Integration of genomics and epigenomics

-

Epigenomics investigates how gene expression and phenotypic diversity are modulated by epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, post-translational histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling, without changing the underlying DNA sequence[68]. DNA methylation regulates growth and development, the stress response, and secondary metabolism by altering the DNA methylation level in various medicinal plants. Moderate water stress notably reduced genome-wide DNA methylation, particularly at the promoters of EsFPS, EsSS, and EsSE in Eleutherococcus senticosus. This promoted the biosynthesis and accumulation of saponins. The elevated saponins function as antioxidants, boosting the plant's resilience to drought stress[69]. In Salvia miltiorrhiza, heightened DNA methylation levels correlate with upregulated expression of numerous genes implicated in the biosynthesis of tanshinone and salvianolic acid, indicating the pivotal role of DNA methylation in orchestrating the accumulation of these bioactive compounds[70]. Histone acetylation affects the developmental process and metabolism by selectively regulating a specific set of genes. Several reports have suggested that plants' development and abiotic stress responses are modulated by histone acetylation levels[71]. Using Petunia hybrida flowers, Patrick et al. confirmed that chromatin-level regulatory mechanisms are crucial for activating both primary and secondary metabolic pathways, thereby governing the synthesis of volatile organic compounds[72].

Advancements in genomics and epigenomics have significantly accelerated our comprehension of plant biology. Nonetheless, traditional bulk analysis, which merely offers averaged data, dilutes cell-specific information, thus hindering the precision of genomic and functional genomic research. Recent breakthroughs in single-cell sequencing technology for genomics and epigenomics have paved the way for exploring cellular heterogeneity across various biological processes. The recent application of these technologies to plants has yielded fascinating insights into a wide range of biological inquiries. For example, the single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high throughput sequencing (scATAC-seq) approach enables the deciphering of chromatin accessibility at a single-cell resolution, inference of gene regulatory networks (GRNs), capture of cell-type-specific cis-regulatory elements (CREs), identification of rare and new cell types, and delineation of cellular developmental trajectories[73]. Currently, scATAC-seq has been applied to the research of Arabidopsis thaliana[74], maize[75], and rice[76]. Liu et al. combined scATAC-seq with scRNA-seq to reconstruct the cell-specific transcriptional regulatory networks (TRNs) controlling root tip development under osmotic stress. They identified candidate stress-related gene-linked cis-regulatory elements (gl-cCREs) and their potential target genes[77]. The application of scATAC-seq in medicinal plant research can identify key epigenetic regulatory elements governing the biosynthesis of medicinal components, reveal how epigenetic regulation mediates adaptive responses under stress conditions, and provide critical technical support for elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of secondary metabolism and genetic improvement in medicinal plants.

Computational tools and pipelines for integrated multi-omics analyses

-

So far, various software tools have been developed for the integrated analysis of multi-omics data. These tools aim to utilize biochemical pathways, biochemical ontologies, biological networks, and empirical correlation analyses to integrate genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data, revealing potential biological relationships. According to the standards of previous studies[78], multi-omics analysis methods can be classified into two major types, namely data-driven analysis and knowledge-based analysis.

Knowledge-based integration relies on validated or anticipated information, with molecular interactions and relationships typically derived from publicly accessible resources[78]. Currently, several tools are employed for knowledge-based integration, including the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), MetaboAnalyst, the integrative Pathway Enrichment Analysis Platform (iPEAP), and PaintOmics, etc. As foundational bioinformatics resources, KEGG and GO serve to interpret biological data, particularly in genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, by standardizing the vocabulary for describing biological pathways or gene/protein functions across species[79]. MetaboAnalyst is a web-based platform for metabolomic data analysis, enabling integration with other omics datasets and facilitating comprehensive analyses of metabolite data from diverse biological samples[80]. iPEAP, a graphical tool, integrates transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic datasets, and GWAS data for pathway enrichment analysis. It features the ability to synthesize enrichment results from distinct high-throughput experiments and quantitatively evaluate various sequencing outcomes[81]. Additionally, PaintOmics offers a robust framework for exploring interactive information within multi-omics datasets[82].

Data-driven integration performs statistical integration of multi-omics datasets via diverse metrics, with pairwise associations readily visualized as networks to uncover the inherent relationships. Available tools include WGCNA, multi-omics factor analysis (MOFA), and network-based models, etc. WGCNA is a computational method for analyzing gene co-expression patterns; it constructs weighted co-expression networks to identify co-expression modules and can link these modules to phenotypic traits or clinical features[83]. MOFA is a computational method for disentangling axes of heterogeneity; it infers hidden factors to capture biological and technical variability and can be shared across multiple modalities[84]. Network-based models are computational methods for investigating systemic interactions in biological systems; they construct networks with nodes (genes or proteins) and edges (representing interactions) to characterize relational patterns and can reveal the topological properties (hub nodes), modular structures, and underlying mechanisms of biological processes or diseases[78].

-

The genetic foundation of high-quality medicinal plants is complex and involves numerous genetic factors and interactions, such as the biosynthetic mechanism of active pharmaceutical ingredients, growth regulation, and the response to abiotic/biotic stress. Whole-genome sequences help us to analyze the unique genome structure, the mechanisms of response to drought stress or the formation of medicinal plants' quality. Herbal genomic studies have established a robust molecular genetic framework to support the cultivation and production of high-quality medicinal plants.

Authentication of traditional Chinese medicine

-

The authenticity of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is one of the important problems facing the TCM market. Numerous techniques such as origin identification, and microscopic and physicochemical identification are commonly employed for classical identification. Origin identification is the basis of TCM identification. It mainly uses the knowledge of morphology and taxonomy to identify the source or raw material of TCM[85]. However, it has disadvantages such as strong subjectivity, hard labor, and unwarrantable accuracy. Microscopic identification is a method used to analyze and identify TCM by means of microscopy and microchemical methods, which is particularly important for identifying some medicinal materials with a similar morphology but different microscopic structures[86]. The micro-identification method has the defects of high equipment requirements, complex operation, and professional personnel. The physicochemical identification method is based on the chemical and physical properties of the species-specific bioactive components in TCM through the means of instrumental analysis to identify its authenticity, purity, and internal quality, and the presence of harmful substances[87]. The weaknesses of this method include the high costs and long time, and that it is ineffective for some herbal preparations without a specific chemical composition. Chen et al. applied multi-omics technology to the identification of TCM[88], thereby enhancing the precision of identifying materials that share similar morphologies and chemical structures.

The emergence of new techniques in recent years, such as whole-genome sequencing and analysis technology, has promoted the rapid development of TCM identification methods based on DNA barcoding[89]. Barcodes with both single loci and multiple loci have been extensively employed, offering adequate resolution for identifying the majority of herbs. Among them, internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) has emerged as the most widely utilized single-locus barcode for the identification of TCM[90,91]. The DNA barcoding system based on ITS2_psbA_trnH has expedited the standardization of molecular identification in herbal medicine[92]. However, as a result of low sequence divergence and complex speciation processes, such as hybridizations, the discriminatory power of DNA barcoding among species remains relatively limited.

Genome-based identification was introduced in 2008 and has demonstrated superior discriminatory power for closely related species[93]. Since its inception, numerous studies have validated its effectiveness and feasibility at lower taxonomic levels[94]. Despite growing recognition, super-barcoding faces significant challenges, such as high costs and variability in the quality of genome sequences in databases. Consequently, if a single-locus barcode suffices for identification purposes, super-barcoding may not always be the preferred choice[94]. However, its advantages are evident in cases where traditional DNA barcodes struggle to differentiate species at lower taxonomic levels.

Molecular-assisted breeding of medicinal plants

-

In the past few decades, the cultivation of medicinal plants has undergone systematic development, resulting in the introduction of numerous high-yielding varieties. The majority of these varieties either have their origins in wild habitats or necessitate extensive breeding periods to be achieved. A primary hurdle for breeders lies in enhancing the efficiency and speed of selection processes, thereby accelerating breeding advancements to align with the demands of pharmaceutical production.

Medicinal plant cultivation has advanced systematically, with many high-yield varieties developed from wild sources or requiring long breeding cycles. A key challenge for breeders is enhancing selection efficiency to accelerate breeding and meet pharmaceutical demands.

Key functional genes in medicinal plants are often associated with important genetic traits. Through the use of genomic annotation data, we can find the dominant genes and use genetic engineering technology to cultivate new germplasm with excellent agronomic traits and high levels of bioactive ingredients, thus laying a foundation for the large-scale extraction and wide application of high-value compounds. By integrating transcriptome and resequencing analyses within or across species, many molecular markers can be identified quickly and accurately, thus speeding the development of high-yield and high-quality varieties.

Molecular marker-assisted breeding provides a powerful approach for breeding medicinal plant cultivars, complementing conventional methods. Furthermore, de novo domestication, which uses modern biotechnologies like genome editing and genetic transformation, has emerged as an innovative strategy. To achieve new breeding goals, domestication-related traits must be rapidly introduced into elite wild germplasm using integrated genetic and breeding tools, creating cultivars with beneficial traits.

Synthetic biology for bioactive compound production

-

The bioactive components of medicinal plants, characterized by their complex and diverse structures, serve as the material basis for their therapeutic effects and are also a crucial source for new drug discovery. However, the development and utilization of many medicinal plant materials are often hindered by several challenges, including slow growth and the low content of the active ingredients, and the complex structure of these bioactive compounds makes them difficult to synthesize chemically. Thus, traditional methods of natural extraction or artificial chemical synthesis are insufficient to meet market demands. Synthetic biology emerges as a promising solution to these problems.

The foundation of synthetic biology lies in elucidating the biosynthetic pathways and identifying key genes. Whole-genome sequencing has enhanced our knowledge of the biosynthesis and regulation of active compounds. Multi-omics analyses facilitate the screening and identification of enzyme-coding genes involved in specific biosynthetic pathways from a vast array of medicinal plant species. A prime example is the anticancer drug paclitaxel (Taxol). Based on the Taxus genome, key genes for synthesizing the precursor, Baccatin III, were characterized and heterologously expressed, paving the way for engineered production[95,96]. Further advances leveraging single-nucleus RNA sequencing and multiplexed perturbation identified additional pathway genes, such as FoTO1. Reconstituting this extended pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana achieved Baccatin III yields similar to Taxus (yew) trees[97]. Similar successes in elucidating complex pathways for other valuable plant compounds demonstrate the potential for synthetic biology to produce a wide range of small molecules from medicinal plants.

However, translating synthetic biology from lab to industrial scale faces significant challenges. These include achieving commercially viable yields, optimizing the carrying capacity and metabolic burden on the chassis organisms (microbial or plant), overcoming metabolic bottlenecks, ensuring the pathway's stability in heterologous systems, and addressing scalability and potential regulatory hurdles. Genomic and multi-omics strategies remain crucial here, enabling the discovery of more efficient enzyme variants, regulatory genes for pathway enhancement, and chassis engineering. Artificial intelligence, empowered by massive omics data, is emerging as a key tool to address these challenges.

-

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provides a comprehensive, high-resolution view of an organism's entire DNA, detecting diverse genetic variations from single nucleotides to large structural changes. This enables precise gene mapping, functional analysis, and evolutionary studies, while also supporting marker-assisted breeding in agriculture. However, there are still some drawbacks in WGS that need to be further optimized. Firstly, most of the genome consists of noncoding regions with poorly understood functions, hindering direct phenotype–genotype associations. Repetitive sequences are difficult to assemble, leading to incomplete genome maps[13]. Secondly, large structural variations (SVs) require long-read sequencing, which is costly and technically challenging[98]. And the assembly of complex genomes need high-performance computing for data storage and analysis (Supplementary Table S2).

Transcriptomics dynamically reflects gene expression levels and reveals spatiotemporal specific expression in medicinal plants. However, transcript abundance often correlates poorly with protein levels because of post-transcriptional regulation. In addition, the expression level of genes is greatly affected by the sample collection time and processing conditions, which further reduced the correlation between gene expression levels and protein functions[99] (Supplementary Table S2). Metabolomics is of great significance for the analysis of active components in medicinal plants. However, it is difficult to annotate metabolites with positional structures, and the accurate differentiation of isomers still poses challenges[5]. In addition, the content of different metabolites in the same sample varies greatly, and mass spectrometry is difficult to simultaneously achieve high and low detection of these metabolites (Supplementary Table S2).

Moreover, co-expression analysis, a common approach to associate gene expression with metabolite accumulation, has intrinsic constraints in tissues where metabolite localization poorly correlates with gene expression patterns. In such scenarios, the inferred gene-metabolite relationships may not mirror real biological interactions, as the spatial separation of metabolites (e.g., in specialized cells or subcellular compartments) can disconnect their accumulation from bulk tissue gene expression profiles. Additionally, metabolite-based genome-wide association studies (mGWAS) encounter specific challenges. In species with low genetic diversity, insufficient allelic variation impairs the ability to detect significant associations. In species with complex population structures, confounding factors such as population stratification may induce spurious associations, making the identification of causal loci more difficult.

Epigenetic regulation is a key factor influencing the accumulation of metabolites. However, there are still many limitations in the study of epigenetic regulation, such as the high cost of epigenomic sequencing, high requirements for experimental techniques, and complex data analysis (e.g., WGBS, scATAC-seq)[76] (Supplementary Table S2).

Furthermore, technical constraints still hinder the functional verification and genetic manipulation of most medicinal plants. Genome editing and transformation are impeded by factors including low regeneration efficiency, poor responsiveness to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, and a lack of stable genetic transformation systems—issues that are especially common in nonmodel medicinal plants with complex genomes or long generation times. These limitations severely restrict the functional characterization of candidate genes and the practical application of genetic improvement strategies.

Future perspectives of multi-omics technology in medicinal plants

-

Despite the long-standing history and extensive applications of medicinal plants, current research has largely emphasized the identification of bioactive compounds and the evaluation of pharmacological effects, although our understanding of their genetic foundations remains limited. This imbalance constrains the full exploration and utilization of medicinal plant resources. To overcome this gap, future research must harness cutting-edge advances in genomics and systems biology. Comprehensive studies integrating structural and functional genomics with multi-omics layers, including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, epigenomics, metagenomics, and bioinformatics, are essential for uncovering the molecular basis of metabolite biosynthesis and regulation.

(1) Construction of AI-driven multi-omics data integration platforms: We need to develop algorithms that are specific to medicinal plants based on the Transformer architecture and build cloud-based analysis platforms. These platforms would standardize and preprocess heterogeneous data; apply AI models like deep learning, graph neural networks, and multi-view learning for feature extraction and network inference; and offer interactive tools for predicting the genes involved in the synthesis and regulation of metabolites, the active sites of key enzymes that catalyze metabolites, etc. It will increase the identification accuracy of unknown metabolites and shorten the cycles of multi-omics data analysis.

(2) Targeted construction of synthetic biology component libraries: This would involve screening for highly active components in medicinal plants and construct standardized expression vectors in E. coli, yeast, or tobacco. Synthetic biology, combined with high-quality genomic resources, would also provide a platform for reconstructing complex biosynthetic pathways in model systems or chassis organisms.

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515012007, 2025A1515012679), Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (2024A04J4663), Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program (2024FY100700). We thank the editors and reviewers for the careful reading and valuable comments.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yang X, Wang Y, Li Y; data collection: Li Y, Zhang X; data analysis and interpretation of results: Li Y, Zhang XH; writing − original draft: Li Y, Yang X, Zhang X; writing − review and editing: Li Y, Yang X, Wang Y, Zhang X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Detailed information of sequenced medicinal plants.

- Supplementary Table S2 Applications, advantages, and limitations of multi-omics technologies in medicinal plants.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Yang X. 2025. Functional genomics in medicinal plants: achievements and future challenges. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e033 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0031

Functional genomics in medicinal plants: achievements and future challenges

- Received: 21 May 2025

- Revised: 31 July 2025

- Accepted: 04 August 2025

- Published online: 23 October 2025

Abstract: Medicinal plants synthesize abundant specialized metabolites that adapt to environmental stress, and these compounds are important for human health, from traditional medicine to industrial uses. Rapid advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies and declining costs have accelerated the generation of high-quality reference genomes for medicinal plants. Integrated multi-omics analysis, particularly transcriptomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, are now essential for deciphering the genes, pathways, and regulatory networks underlying the biosynthesis of metabolites. While published research has explored hundreds of medicinal plant genomics, a comprehensive knowledge of secondary metabolism integrated via multi-omics strategies remains lacking. In this review, we bridge this gap by summarizing the distinctive features of medicinal plants' genomes and highlighting how integrated omics facilitate the discovery of biosynthetic mechanisms. We also explore some applications in molecular breeding and synthetic biology, demonstrating how genomic insights can drive the sustainable development and innovative utilization of medicinal plant resources.

-

Key words:

- Medicinal plants /

- Genomics /

- Multi-omics /

- Molecular-assisted breeding /

- Synthetic biology