-

Climate change is intensifying droughts worldwide, threatening crop yields, food security, and rural livelihoods. According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the past two decades have seen some of the most widespread and destructive droughts on record, driven by rising temperatures, persistent land degradation, and water stress[1,2]. Recent events since 2023 rank among the most severe, with major impacts on food security, water availability, and ecosystems worldwide[1,2]. These increasingly severe droughts are causing unprecedented impacts on agricultural productivity[1,2]. Between 2005 and 2015, droughts cost the agricultural sector USD 29 billion—83% of all drought-related losses (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)[3,4]. In countries such as China, where agriculture underpins rural livelihoods, only 51% of farmland was effectively irrigated by the end of 2022, despite total irrigated areas reaching 103.7 million hectares[5]. Similarly, in France, modern irrigation systems cover only 47% of the irrigated area. In response, research and policy efforts have increasingly focused on developing drought-tolerant crop varieties as a cornerstone of climate adaptation[6−10]. Drought tolerance has become an emblem of biotechnology's promise in agriculture, with billions invested globally to breed or engineer traits conferring resilience.

Yet a fundamental question is often overlooked: can genetically enhanced drought tolerance alone ensure yields without water? Despite decades of breeding efforts, severe droughts continue to devastate harvests[11]. While drought tolerance is undoubtedly valuable[12], this perspective argues that without prioritizing water management, genetic solutions alone will remain insufficient under intensifying climatic extremes.

-

Drought-tolerant crops employ several physiological mechanisms to cope with water stress. These include osmotic adjustment to maintain cell turgor, deeper or more proliferative roots to access subsurface moisture, and conservative stomatal regulation to reduce transpiration[13,14]. For example, deeper rooting in maize enhances water uptake under mild drought conditions, while osmoprotectant accumulation helps rice sustain photosynthesis in drying soils[15]. However, these adaptations come with trade-offs. Conservative water use often reduces photosynthesis and growth rates, limiting yield potential even under moderate stress[16,17]. For instance, a meta-analysis showed that even mild drought (20%–35% water reduction) can reduce vegetable yields by 12%–20%, while severe drought (> 50% reduction) causes catastrophic losses across crops[18].

Field evidence confirms these physiological limits. Across major agricultural regions, severe droughts have caused devastating yield losses despite the adoption of drought-tolerant varieties. For example, in the United States, the 2012 drought reduced corn and sorghum yields by ~27% despite widespread adoption of drought-tolerant hybrids[19]. In Argentina, during the 2022/2023 drought, precipitation fell 55% below baseline levels, leading to a 43% reduction in peanut and soybean yields compared to the previous growing season[20]. Similarly, Zambia's 2024 drought resulted in a 28%−67% decline in national harvests of grains (e.g., wheat, corn, sorghum, rice, and millet) despite the promotion of drought-tolerant cultivars[21,22]. In China, the 2022 Yangtze Basin drought damaged over six million hectares of crops, affecting 52 million people despite widespread use of advanced agricultural technologies[23]. Even in parts of Western Europe, severe drought in 2022 caused up to 45% yield losses in wheat and rice[24,25].

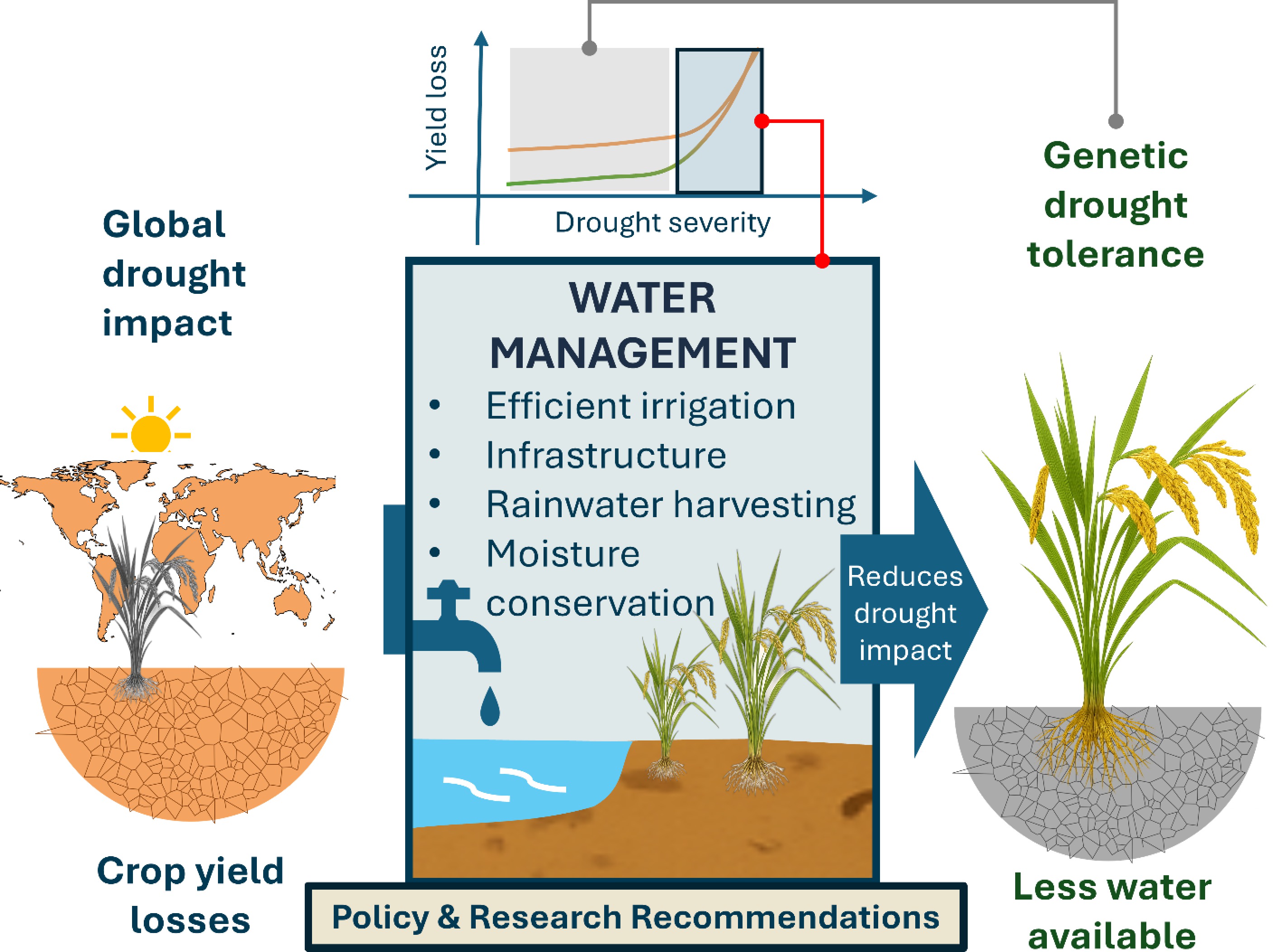

These cases highlight that under extreme drought—when soil moisture approaches the permanent wilting point (approximately −1.5 MPa soil water potential)—no genetic mechanism can maintain growth or reproduction. Physiologically, plants require minimum water to maintain cell turgor and metabolic activity; when this threshold is exceeded, photosynthetic machinery and reproductive organs fail regardless of tolerance traits[14]. Consequently, the utility of drought tolerance traits is predominantly confined to mild water deficits (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating why effective water management outweighs genetic drought tolerance in reducing agricultural drought impacts. The left panel shows global drought-induced crop yield losses, emphasizing that under extreme water scarcity, even drought-tolerant crops cannot maintain productivity without water interventions. The central panel outlines key water management strategies—including efficient irrigation, infrastructure development, rainwater harvesting, and soil moisture conservation—that directly reduce drought impacts and create conditions where genetic improvements can be effective. The right panel depicts drought-tolerant crops benefiting from improved water availability. The top graph shows the relationship between drought severity and yield loss, highlighting that while genetic drought tolerance can reduce losses (e.g., by 7.5 g·m−2·year−1 for maize) under mild to moderate drought conditions[12], effective water management is necessary to sustain yields under severe drought.

-

Although drought-resistant crops demonstrate significant potential to mitigate yield losses under mild drought conditions, contemporary agricultural systems increasingly face flash droughts characterized by rapid intensification. These abrupt-onset events cause precipitous depletion of surface soil moisture, leading to substantial reductions in crop yields[26,27]. Regions most prone to agricultural flash droughts include croplands in southern China, central and eastern Europe, southern Russia, India, southeastern South America, and the central and eastern United States[27]. This is becoming an increasingly common reality under current and future climate conditions[26,27]. Under either scenario, physiological regulation alone proves inadequate once soil moisture falls below critical thresholds, making supplemental irrigation the only reliable safeguard for crop productivity (Fig. 1).

Therefore, despite the appeal of genetic solutions, water remains the primary limiting factor for plant life. In China, for example, irrigation contributes to over 30% of the increase in grain production. Effective water management, including irrigation infrastructure, rainwater harvesting, and soil moisture conservation, has underpinned resilient agriculture for millennia. Historical civilizations from Mesopotamia to the Yangtze Delta (the earliest water management engineering in China, 5,100 years ago) and the Indus Valley flourished by developing water management systems before crop domestication advanced significant drought tolerance traits[28,29].

Modern examples abound. In Israel, integration of drip irrigation with deficit irrigation strategies has maximized water use efficiency while sustaining yields under arid conditions[4]. The American West's irrigation networks transformed desert landscapes into productive farmland, enabling stable maize and vegetable yields even during multi-year droughts. In sub-Saharan Africa, simple rainwater harvesting combined with in situ soil water conservation (e.g., zai pits and tied ridges) has doubled yields in drought-prone regions without requiring new crop varieties[30]. For instance, in Burkina Faso, rather than relying on drought-resistant crop varieties, farmers have achieved substantial yield increases from around 400 to over 1,000 kg·ha−1 by implementing simple water management interventions such as contour stone bunds and planting pits, which improve rainfall infiltration and retention[31]. Moreover, soil management practices such as mulching, conservation tillage, and organic matter addition improve soil structure and water holding capacity, enhancing plant-available water during dry spells. For instance, conservation tillage (covered with crop residues, ~3 t·ha−1) with drought-tolerant maize can produce yields that are 0.7 t·ha−1 higher than those under conventional ridge tillage[32]. In India, incorporating crop residues into soils increased water retention and stabilized wheat yields under rainfall variability[33]. These approaches address the root cause of water scarcity directly, rather than solely improving plant coping capacity.

-

This is not to discount the value of drought-tolerant varieties. Rather, their benefits are maximized when combined with effective water management. Under moderate drought stress, tolerant varieties can maintain physiological processes longer, translating limited water into greater yields. For example, integrating drought-tolerant maize with deficit irrigation in India increased yields by ~20% compared to non-tolerant varieties under similar water regimes[15].

However, without baseline water availability, even the most engineered crops will fail to thrive. A conceptual framing (Fig. 1) illustrates this synergy: while genetic traits reduce yield loss under partial stress, and water management mitigates scarcity impacts, their combination offers the greatest resilience. Conversely, in extreme drought without water interventions, yield collapse is inevitable regardless of genetic traits.

-

Recent agricultural research disproportionately prioritizes genetic breeding and biotechnological innovation. However, fundamental, low-cost field engineering interventions often deliver more substantial and rapid benefits for smallholder farmers. These practical approaches remain underreported and underprioritized in scientific discourse. The Burkina Faso example, where simple water management doubled yields without drought-tolerant cultivars[31], exemplifies how practical, scalable solutions frequently outperform high-tech fixes when water is the limiting factor.

Moreover, prioritizing water management brings important environmental co-benefits. For instance, rice paddies account for approximately 10%–15% of global methane emissions[34]. While genetic breeding and certain soil amendments can moderately reduce methane emissions from rice fields[34], their effects are marginal compared to widely adopted practices like alternate wetting and drying[35]. Unfortunately, a lack of infrastructure for effective water control in many regions remains a major bottleneck, hampering progress toward climate-neutral rice production.

-

Climate adaptation strategies must acknowledge these biophysical realities. Investments in drought-tolerant crop breeding should be accompanied by equal or greater investments in the following (Fig. 1).

Irrigation modernization

-

Urgent modernization of irrigation infrastructure, particularly efficient and affordable technologies for smallholder farmers, is critical. Currently, only about 5% of cropland in sub-Saharan Africa benefits from irrigation, contrasting sharply with approximately 40% in Asia[36]; both regions face pressing needs to upgrade and improve their irrigation systems.

Rainwater harvesting expansion

-

Scaling up rainwater harvesting and storage systems by leveraging landscape hydrology mitigates rainfall variability. Small reservoirs, ponds, and roofwater harvesting remain underutilized across the Global South[37,38].

Soil health restoration

-

Enhancing soil organic matter directly improves water retention capacity. Empirical studies confirm that increasing soil organic carbon by 1% can raise water holding capacity by ~2 mm per 100 mm soil depth, substantially benefiting crops during dry spells[39].

Water governance reinforcement

-

Strengthening allocation policies through tiered pricing, enforceable quotas, and transparent mechanisms prioritizes essential agricultural and domestic needs. Empirical evidence from countries such as Israel and Australia shows that coupling irrigation expansion with robust governance, including water markets, metering, and reuse incentives, can enhance efficiency while preventing inequality and environmental degradation[40].

Furthermore, agricultural research should prioritize holistic on-farm trials that combine improved varieties with soil and water management practices to quantify integrated benefits under real-world constraints. Such trials better capture farmer decision-making, resource limitations, and socio-economic trade-offs critical for adoption.

-

In the race to adapt agriculture to a hotter, drier future, drought-tolerant crops are frequently portrayed as silver bullets. However, crop productivity is physiologically impossible without water. Effective water management constitutes the foundation upon which genetic solutions can achieve their full potential. As droughts grow increasingly frequent and severe, prioritizing water interventions is not merely complementary to genetic advances but a prerequisite. Ensuring food security in a warming world requires recognizing this reality. Irrigation infrastructure, rainwater harvesting systems, and soil moisture conservation practices will continue to underpin agricultural resilience, enabling drought-tolerant crops to express their potential rather than succumb to moisture deficits.

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft preparation, project administration: Zhang S; visualization: Zhang S, Guo Y; validation, writing – review & editing: Guo Y. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC3709100), and Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB0750400).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Global droughts are intensifying, threatening food security worldwide.

Recent extreme droughts reveal that genetic solutions alone are insufficient.

Water management underpins agricultural resilience under climate change.

Prioritizing irrigation and rainwater harvesting ensures adaptation success.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang S, Guo Y. 2025. Water first: why effective water management outweighs genetic drought tolerance in agricultural adaptation. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e004 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0002

Water first: why effective water management outweighs genetic drought tolerance in agricultural adaptation

- Received: 12 July 2025

- Revised: 08 August 2025

- Accepted: 17 August 2025

- Published online: 17 September 2025

Abstract: Climate change intensifies droughts globally, threatening crop yields and food security. Although breeding drought-tolerant crops is widely promoted as an adaptation strategy, their effectiveness is limited under severe water scarcity. This perspective argues that effective water management, including irrigation, rainwater harvesting, and soil moisture conservation, not only surpasses genetic improvements in sustaining productivity but must be prioritized as an urgent response to real-world drought risks. Plants require a minimum water supply for growth and reproduction; no genetic trait can compensate for absolute water deficits below the permanent wilting point. Recent extreme droughts have caused widespread crop failures despite the use of drought-tolerant cultivars, whereas integrated water management has consistently stabilized or improved yields. Thus, prioritizing water interventions is essential, not merely complementary. Food security in a hotter, drier world hinges on a fundamental biological principle: crop productivity is physiologically impossible without water.

-

Key words:

- Water management /

- Heatwave /

- Drought tolerance /

- Climate adaptation /

- Irrigation /

- Agricultural resilience /

- Food security