-

Nigeria is currently the top global producer of cassava (st). The crop's capacity to generate revenue for small-scale farmers and associated value chains in Africa is on the rise, with significant potential for advancing the continent's development[1,2]. For hundreds of millions of people in Africa, the edible storage roots of cassava serve as a vital staple food[3]. In Nigeria, where there are six agroecological zones, nutrient deficiency is a significant public health concern that is correlated with cassava consumption[2]. The use of currently available and commonly used fertilizers, (NPK15-15-15 and NPK20-10-10) does not seem to satisfy the requirements for a more balanced crop nutrition[4,5]. Foliar fertilization presents a promising solution to these challenges, offering a more targeted and efficient method for delivering essential nutrients directly to the plant[6]. Foliar application allows for the correction of nutrient deficiencies, particularly micronutrients, during critical growth phases when soil uptake is limited due to water stress, poor soil structure, or nutrient immobilization. The application of foliar fertilizers, such as zinc, boron, and phosphorus, has been shown to enhance nutrient uptake, improve plant health, and increase yields. It can be particularly beneficial in regions where soils are prone to nutrient leaching or high pH levels, which reduce nutrient availability[7]. In the south-south and south-east regions of Nigeria, soil acidity often results in the fixation of phosphorus (P), which limits its bioavailability when applied through granular fertilizers[8,9]. This soil constraint presents a viable opportunity for the foliar application of phosphorus, as it allows for more direct and efficient nutrient uptake by plants, bypassing the limitations associated with soil P availability.

Foliar fertilizer application is essential in crop production, particularly for delivering micronutrients like copper and zinc, which are absorbed by the plant's aerial parts[10]. This method is effective for correcting nutrient deficiencies because the plant quickly utilizes the nutrients, making foliar feeding a reliable solution even after visual symptoms appear[11]. While primary macronutrients (N, P, K) are most efficiently applied through soil, foliar feeding is more suitable for secondary nutrients (calcium, magnesium, sulfur) and micronutrients during critical growth stages[12]. However, foliar fertilizers are applied in small quantities to avoid leaf scorching, and frequent applications of macronutrients can be impractical[11,13]. Despite these limitations, foliar application is highly effective for nutrients that are otherwise immobilized in the soil[7].

Cassava encounters stages of high nutrient demand during intensive shoot growth at early growth stages and during the bulking-up process[14]. These essential growth stages, which influence the yield and quality of the food, could coincide with insufficient soil supply resulting from a variety of circumstances, such as short-term drought or waterlogged conditions, which prevent roots from breathing and operating as they should, uncontrolled weed populations that severely competes with the growing cassava crop[15]. Cassava exhibits complex nutrient requirements that vary across its growth stages and the different agroecological zones in which it is cultivated[16]. Soils in many cassava-growing regions in Nigeria are deficient in essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, as well as micronutrients such as zinc and boron[17]. These deficiencies are exacerbated by soil pH imbalances, which reduce nutrient availability, especially phosphorus. Across the states in Nigeria, nutrient limitation accounts for 55.3% of the total cassava yield gap, while the remaining 44.7% is attributed to water limitation[18]. The typical reliance on soil-based fertilization methods often fails to address these challenges efficiently, particularly in the absence of supplementary micronutrient management[19]. On the other hand, the application of small amounts of secondary and micronutrients to the soil may result in 'dilution' and low concentrations that will hamper the uptake of the nutrients by the plants. Under such conditions, foliar application of nutrients will dramatically increase yields and improve yield quality[15]. Foliar feeding has the major benefit of being able to quickly and effectively satisfy an urgent requirement[11]. As a result, they are particularly effective as preventative and occasionally as curative treatments. Because the nutrients are given to and absorbed by the target organs directly, foliar fertilization of crops has distinct advantages over soil-applied fertilizers[11].

The soil frequently serves as a barrier and a buffering medium due to its diverse chemical, physical, and biological makeup. Foliar feeding is typically meant to supplement rather than replace soil or fertigation applications[20,21]. However, foliar application can be a stand-alone strategy to fully meet crops' needs before deficiencies occur when only small application rates are necessary, such as in the case of supplementary application of phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, sulfur, or trace elements[12,22]. One general consideration for foliar application is its low nutrient recovery efficiency because it is being sprayed[9,13]. On the one hand, it requires the crop to be in an advanced development stage with enough leaves having been unfolded and resulting in a high leaf area index and high soil cover rates for foliar application to be efficient. On the other hand, it requires that it does not rain in first few days after application because of the nutrients being washed off. At the same time foliar application helps to mitigate the effect of drought because uptake from soil is limited during such period[23,24].

A key principle for effective nutrient management is to ensure nutrients are provided at the right time to meet plant demand, emphasizing four key elements: choosing the right product, applying the correct amount, timing the application, and placing the fertilizer effectively[25,26]. Foliar fertilizers offer advantages in timing and precise application, crucial for cassava growth. However, their use in cassava fields is limited and underexplored in both practical and scientific contexts, particularly in Nigeria and other major cassava-producing countries. This paper reviews available data, addressing the nutrients required for cassava at different growth stages and examining the edaphic and climatic factors that constrain cassava production. We provided answers to the question of where, when, and what type of foliar fertilizers will be most beneficial for cassava. In the end, we summarized in this paper the various considerations for foliar fertilization of cassava in Nigeria and this is applicable in other agroecologies where cassava is grown.

Agroecological considerations for foliar fertilization of cassava

-

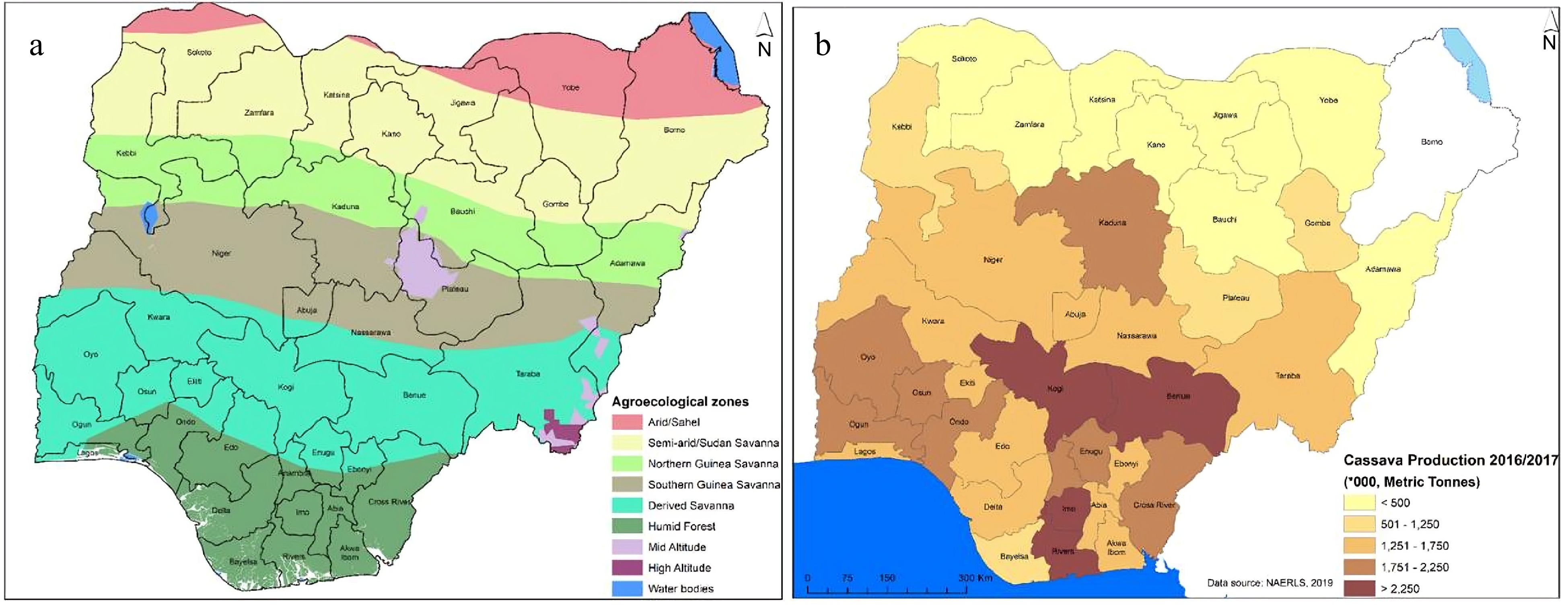

Nigeria contains seven distinct agroecological zones that move from the humid forests in the south to the arid Sahel Savanna in the north (Fig. 1a). These zones differ significantly in terms of soil fertility, rainfall patterns, and temperature, all of which affect the nutrient dynamics and fertilization strategies for cassava cultivation. These zones include the Humid Forest, Derived Savanna, South and North Guinea Savannas, High and Mid Altitude Savannas, Sudan Savannas, and Sahel Savannas humid forest zone. The Sahel Savanna zone experiences annual rainfall as low as 500 mm, whereas the Humid Forest zone experiences annual rainfall of roughly 3,000 mm. A total of 33 million hectares of the nation's 84 million hectares of arable land are now being farmed[27].

Cassava is a vital crop grown in the humid regions of Nigeria. Currently, Nigeria is the top producer of cassava globally, yielding about 34 million tonnes of tuberous roots annually. Cassava is widely used in various processed forms in Nigeria. The leading cassava-producing states in Nigeria are Rivers, Imo, Kogi, and Benue, each producing over 2,250,000 metric tonnes of cassava per year (Fig. 1b). Ogun, Oyo, Osun, Ondo, Kaduna, and Cross River among others are the second highest cassava producing states. Kano, Adamawa, and Bauchi among others are the least cassava producing states with an annual turnover of less than 500,000 metric tonnes each. The average yield per hectare is 10.6 tonnes.

Soil fertility considerations for foliar fertilization of cassava

-

Soil condition and water availability, if managed successfully, will assist enhance agricultural output and address the nation's food problem[28,29]. Nigeria offers a diverse range of soil types with varying levels of fertility and ecological conditions. The various soils are determined by the area's prevalent meteorological conditions, vegetation cover, and terrain, among other factors. The potential for agricultural use and management of soil types varies. Most soils in Nigeria are formed from the basement rock complex and sandstones which are inherently very poor in nutrients[30,31]. The Delta areas are made up of nutrient-enriched soils induced by the high degree of debris deposition. Nutrient limitations therefore exist on the different types of soil across the agroecological zones of Nigeria. Highlighted below are the major limiting nutrients and major soil properties or characteristics that may cause nutrient limitation in soils.

Nitrogen

-

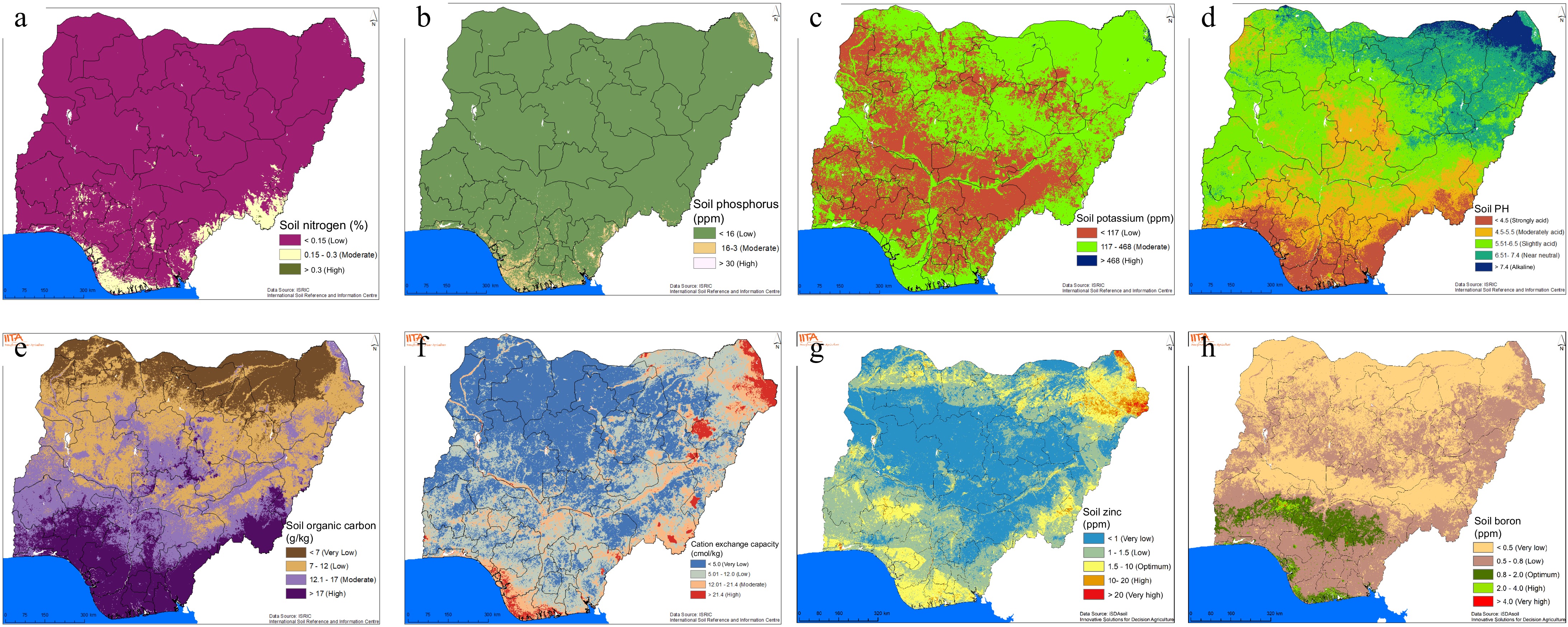

Nitrogen (N) is the primary limiting nutrient for sustaining crop yields and quality[32]. Consequently, large quantities of nitrogen fertilizer are usually applied to increase crop production. Figure 2a shows a wide spread of soils with low levels of nitrogen across Nigeria. This indicates that most of Nigeria' s soils are of low nitrogen content. There are a few spots of moderate level of nitrogen around the extreme borders of south-south and south-east. Soils high in soil total nitrogen are rare in Nigeria. In the meantime, amino acids, which serve as the building blocks of plant proteins and enzymes, depend heavily on nitrogen, a macronutrient that is crucial for plant metabolism. Nitrogen plays a crucial role in the chlorophyll molecule, enabling plants to utilize photosynthesis for the absorption of sunlight energy. This process is essential for promoting plant growth and maximizing crop output. Furthermore, nitrogen is indispensable for regulating energy distribution within the plant, ensuring optimal yield. Owing to the large quantity of nitrogen needed by crops, the application of nitrogen cannot be done solely by foliar but has to be soil-based and may be supplemented by foliar application[33]. Visible signs of N deficiency may easily be corrected through foliar application of nitrogen.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of some major soil properties in Nigeria (these soil maps were produced using iSDA soil data at 30 m resolution).

Phosphorus

-

Phosphorus is an essential part of soil organic matter. It is created through the natural breakdown of minerals in the earth's crust in terrestrial ecosystems[34]. It is the second most limiting nutrient for crop yield after nitrogen. Soil available phosphorus has been found limiting in Nigeria soils. About 90% of the country's agricultural soil is low in phosphorus (Fig. 2b). There are however few spots across the country with moderate and high phosphorus levels. While inorganic chemical processes can regulate the cycling of P, in many systems the turnover of organic P regulates the availability of P to plants through the breakdown of organic matter or the release of P from microbial biomass. The principal mechanism for preserving extremely low P concentrations in soil solutions, especially in mineral soils, is phosphate sorption by diverse soil constituents. The availability of phosphate in the soil solution depends on the forms of phosphorus and the pH of the soil, i.e., whether it is acidic or alkaline. Phosphorus fixation by ions in the soil is dependent on pH[35]. The supply of phosphorus to plants is directly affected by the rate at which adsorbed phosphorus is released[36], which is important for long-term crop planning. Foliar fertilizer, therefore, holds promise in this regard by providing the phosphorus needed by plants at critical stages regardless of soil limiting factors.

Potassium

-

Potassium is another essential mineral for enhancing crop output and soil enrichment[37]. It is the third most essential nutrient found in mineral fertilizers[38]. It improves the resistance of plants to diseases and plays a critical role in enhancing crop yields and productivity. Among the three primary essential nutrients, potassium is the most abundant in Nigeria. The soils have moderate levels of potassium concentration in soils predominately in the northeast region (Fig. 2c). Soils of low potassium content are concentrated around areas from the central part of the country towards the southwest and southern parts of the country. In all, the proportion of soils with moderate levels is higher than those with low levels of potassium.

Soil pH

-

The pH level of soil has a significant impact on the availability of nutrients for plant uptake. Soil with very low or very high pH levels can result in nutrient limitations, as the nutrients become inaccessible for plants. The Delta area is predominantly covered with soils of low pH (Fig. 2d). That is, the soils are strongly acidic, in which case cassava is not able to survive without liming. This is because with low pH, nutrients are fixed and become unavailable for plant uptake[39]. This type of nutrient limitation induced by soil pH could be obliterated by foliar fertilizer application. Alkaline soils dominate the northeast region while the other areas vary from moderately acid to near neutral, and these are considered suitable for the crops of interest.

Soil organic matter

-

Soil organic matter plays a significant role in determining the fertility of tropical soils[40]. The amount of organic matter in the soil is influenced by inputs such as residues, roots, and litter decomposition. Factors affecting organic matter in the soil include the soil's physical and chemical characteristics, moisture content, temperature, aeration, bioturbation (soil macrofauna mixing the soil), water leaching, and humus stabilization (organo-mineral complexes and aggregates)[41]. Additionally, land use and management practices impact organic matter in the soil[42]. Soil organic matter serves as a nutrient storehouse for crops. It also helps aggregate the soil, promote nutrient exchange, maintain moisture, reduce compaction, and surface crusting, and facilitate water infiltration into the soil. Nutrient exchanges between organic matter, water, and soil are critical to soil fertility and must be preserved for long-term production[43]. Soil organic carbon is a measurable component of soil organic matter. In Nigeria, there are widespread soils which are either low or very low in organic carbon (Fig. 2e). Specifically, soil organic carbon is very low and high in soils of extreme northern and extreme southern Nigeria, respectively while other areas are either characterized with low or moderate level of soil organic carbon (Fig. 2e).

Cation exchange capacity

-

Cation exchange capacity (CEC) is a soil's ability to retain nutrients, influenced by soil type, pH, and organic matter. Soils with high CEC can hold more nutrients, while those with low CEC quickly become deficient[44]. This is important for soil fertility[45,46]. Soils of very low CEC are widespread in Nigeria with few and dispersed spots of high CEC soils in the country (Fig. 2f). The very low CEC soils are more concentrated around the central to the northwestern part of Nigeria, while the low and moderate CEC soils are spots within the very low CEC soils and are predominantly around the south-west, south-south, east and north-eastern Nigeria (Fig. 2f). More often than soils with high CEC, low CEC soils become acidic quickly[47]. The ability of these soils to hold nutrients (through granular fertilizer application) is also low, thus foliar application become advantageous in this case. The high CEC areas are found around the border with Lake Chad, few spots with northeast and extreme south border to the Altantic Ocean around Port-Harcourt (Fig. 2f) which are more areas of debris deposition. Clay soils, for example, have a high CEC and a high water-holding capacity, whereas soils with a low CEC have a low water-holding capacity. Low CEC may result in low nutrient recovery efficiency for granular fertilizer application and therefore provide an argument for using foliar fertilizer.

Soil micronutrients

-

Micronutrients play a crucial role in plant growth as they are required in small quantities. A deficiency of micronutrients can significantly reduce crop yield as they are essential for important physiological processes[48]. Studies have shown that applying micronutrients to the leaves is 6 to 20 times more effective than applying them to the soil, resulting in improved plant nutrition[49]. For example, boron is essential for flowering, pollen development, and pollination[48]. Most of the boron in maize is accumulated just before pollination to support reproductive growth in tassels and ears. Cassava requires a continuous supply of boron throughout the season as the nutrient is not mobile in the plant.

Boron deficiency is likely to occur when the boron value is less than 0.5 ppm in soils and 20 ppm in plant tissue, while symptoms of boron toxicity appear when there is more than 5 ppm of available boron in the soil and above 200 ppm in the tissue[50]. In Nigeria, most soils have very low (in the northern part) or low (in the southern part) boron levels. Adequate boron levels are only found in the middle belt of Nigeria, stretching from the centre towards the southwest (Fig. 2). Under aerobic conditions, soil acidification converts borate into boric acid, which can be effectively washed away through leaching in regions with abundant rainfall and highly percolating sandy soils – conditions commonly found in Nigeria. This creates a good opportunity for the development and use of foliar fertilizers enriched with boron. Zinc is another important micronutrient for crop production. In Nigeria, there are widespread occurrences of soils with low or very low zinc concentrations, particularly in the central zone of the country, while areas around the country borders tend to have optimum zinc levels (Fig. 2). Zinc deficiency significantly reduces maize and rice yields. Research indicates that foliar zinc application leads to significant improvements in growth, yield attributes, and overall yield of rice. Similarly, studies have demonstrated that foliar spray of 2% ZnSO4•7H2O can increase cassava biomass yield by 30.6% to 75.7% compared to soil fertilizer application[51], while maize grain yield has also been shown to increase with the application of 5 kg/ha of zinc.

Plant uptake mechanisms of foliar fertilizers

-

The structure and function of green leaves enables them to perform vital processes such as collecting sunlight, photosynthesizing, transporting sugars, and transpiring water vapour and gases. Recent research by Goldbach[52] indicates that both inorganic and organic substances can be absorbed through leaf surfaces. The cuticle, which covers leaf cell walls and is absent in the root structure, may lead to differences in the nutrient absorption mechanism between leaves and roots[12]. Factors like charge type, adsorbability, and ion radius are critical for nutrient uptake in plant tissues. Energy for active absorption can come from photosynthesis in green leaves or respiratory metabolism. Additionally, the quality and intensity of light significantly speed up ion absorption by leaves.

Leaves undergo three stages of ion uptake. During the first stage, chemicals applied to the leaf surface can permeate the cuticle and cellulose wall through limited or free diffusion. In the second stage, these compounds are adsorbed to the surface of the plasma membrane through some form of binding[53]. Finally, in the third stage, the absorbed substances are taken up into the cytoplasm, a process that requires energy from metabolism. The journey of nutrients applied to leaves involves passage through the membrane, cuticle, cell wall, and cuticular wax[12,53]. Notably, the voids between these layers, characteristic of inorganic ions, may allow the nutrient to pass through them or, alternatively, through the layers themselves. Recent studies have also demonstrated ion absorption by leaf stomata, with foliar absorption being simpler when the stomata are open[54].

Nutrient remobilization is crucial during plant development. However, if a nutrient cannot be transferred from the sprayed tissues to those growing following the spray treatment, signs of a deficit will manifest in the emerging shoots[54]. It is observed that macronutrient mobility in plant tissue, except for Ca and S, is satisfactory, whereas most micronutrients have poor mobility in plant tissues. For instance, Mn is poorly absorbed and exhibits low mobility in the phloem, necessitating multiple foliar applications during the soybean's growth season[55]. Fe, on the other hand, is static in some plants but mobile in others[56]. The differences in nutrient remobilization in plant tissues suggest significant variations between nutrients and plant species.

Source and sink limitations on cassava yield

-

The growth rate of organs such as roots, shoot apices, and storage organs can be constrained by the availability of photosynthates from source tissues (source restriction) or by the capacity of the sink to utilize these photosynthates (sink limitation). Sink constraints in storage organs can be caused by inefficient phloem unloading and poor conversion of photosynthates to storage compounds, as well as by a deficiency of storage cells per sink organ or sink organs per plant or area of land[57]. These limitations can lead to the inhibition of photosynthesis. The interplay between genetics and environment significantly influences sink-source constraints. In crop species where yield is determined by storage organs like tubers or roots, nutrient supply can impact yield response curves, reflecting sink limitations due to nutrient deficiency or excess supply of nutrients during crucial stages of plant development. Crop yield is influenced by the duration of the storage phase, which can be affected by factors such as drought stress, high temperatures, and nutrient deficit, leading to variations in the weight but not the number of sink organs[58]. Foliar fertilizer application during critical periods may help enhance yield[59]. Actual yield is not only determined by the fixed potential sink capacity during critical times but also by the assimilated supply after flowering. Environmental conditions during the critical phase and the post-anthesis period determine whether yield is limited by source or sink. Root yield is frequently sink-limited in the absence of stressors[60]. Providing sufficient amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus during this critical phase may effectively increase tuberization in cassava.

Visible signs of nutrient deficiency in cassava

-

Nitrogen is a mobile nutrient in plants, and its deficiency typically begins in the older, lower leaves before progressing upward if the deficiency persists. Symptoms include a characteristic v-shaped yellowing that starts at the leaf tip and moves toward the base along the midrib (Fig. 3). This yellowing is a clear indication of insufficient nitrogen availability in the plant's system[61]. Phosphorus deficiency is commonly observed in young cassava plants. It moves around the plant and mobilizes easily. Affected plants exhibit dark green foliage with older leaves developing reddish-purple margins and tips (Fig. 4). Newly formed leaves may appear pale or lack pigmentation altogether. Plants suffering from phosphorus deficiency typically grow more slowly and are smaller compared to healthy plants. Notably, as the plants grow taller, reaching approximately three feet or more, these symptoms tend to disappear, suggesting a reduction in deficiency impact over time. Severe potassium deficiency in cassava is evident in older leaves, which display chlorosis (yellowing) and necrosis (death of tissue) along the edges. In contrast, younger leaves located at the top of the plant often remain green and unaffected (Fig. 5). This contrasting symptom distribution highlights potassium's role in maintaining overall plant health, particularly in older tissues

Figure 3.

Nitrogen deficiency in Cassava[37].

Figure 4.

Phosphorus deficiency in Cassava[16].

Figure 5.

Potassium deficiency in cassava[67].

Nutrient diagnostic tools

-

Soil testing in agriculture typically involves analyzing a soil sample to assess its nutrient levels, composition, and properties such as acidity or pH. Through soil testing, it is possible to ascertain the soil's fertility, including identifying nutrient deficiencies, potential toxicities resulting from excessive fertility, and any inhibitions caused by the presence of non-essential trace minerals. The experiment simulates how roots ingest minerals. Right, and proper fertilizer recommendation is essentially based on the results of soil testing. There are several approaches to this. A common approach is based on a product function of the specific crop, yield target, soil fertility class (low, medium, adequate, and high), and the crop nutrient requirement. Another approach is based on the nutrient recovery rate of the crop and the yield target. These different approaches provide recommendations for granular or soil-based fertilizers. Foliar fertilizers are often recommended for supplemental application usually for micronutrient application.

Plant analysis is a valuable tool for verifying nutrient deficiencies, toxicities, and imbalances. It can also help identify 'hidden hunger', assess fertilizer programs, study nutrient interactions, and determine the availability of elements for which reliable soil tests are not yet available[61]. Farmers rely on visual symptoms, plant tissue examination, and soil study to identify nutrient shortages[62]. Soil testing and plant analysis are both important for understanding nutrient absorption by plants and nutrient availability in the soil. One must consider potential sources of the impacts seen after evaluating the status of each nutrient individually. Accordingly, the final diagnosis must take into account the cropping history, sampling methods, results of soil tests, and knowledge of nutrient concentrations[63]. Plant analysis can help to direct investments in fertilizer toward more effective uses if done correctly.

However, plant analysis through standard lab tests is often expensive and could take quite a long time to deliver results. In agriculture, time is a crucial factor because farms are exposed to heavy rainfalls, heat waves, or other variables that change the nutrient prevalence in plants within the shortest timeframe. Thus, the use of diagnostic tools such as handheld scanners becomes imperative. This type of tool provides an instant determination of plant nutrients at any growth stage though the results are usually less accurate compared to standard analytical methods. They are however accurate enough to provide an indication of nutrient limitation in plant leaves for corrective fertilizer applications. It is important to point out that plant diagnostic tools are not common in Nigeria both in demand and supply.

Opportunities for foliar fertilization of cassava

-

The major nutrient that cassava consumes per ton is potassium (7 kg K2O per ton), and it also needs a lot of nitrogen (5 kg N per ton) and phosphorous (2 kg P2O5 per ton). Cassava produces a lot of carbohydrates, so it needs a lot of K (75 K2O per ha), which plays a crucial role in the synthesis and transport of carbohydrates. The fundamental steps of photosynthesis are favoured by an abundant K supply. Additionally, it controls the ratio of assimilation to respiration in a way that enhances net assimilation. This is necessary for healthy growth, and the development of reserve assimilates. During the initial 8-week growth phase after planting, the cassava plant develops stems, leaves, and root systems. To promote tuberous root development, foliar fertilizer should be applied during this phase and possibly after the dry season to kick-start growth at the beginning of the next rainy season. However, no experiments have been done with the application of foliar fertilizer to cassava, and therefore, there is no information on the effectiveness of this practice. Little is known about foliar application of P to cassava[64]. The uptake requirements for cassava are considerable if we consider the uptake requirement of 2 kg P per ton of tuber harvested. Using the same arguments of the limited available P in the soil, and possible P-fixation in the soil in those regions where cassava is grown, there seems to be an opportunity for foliar application of P to cassava that should be further investigated.

The source material for the phosphate in liquid formulation may consist of ortho and polyphosphates that are soluble in water, and orthophosphates are immediately available to the plant for uptake[35]. Low solution pH reduces the ionization of the orthophosphate molecule and herewith increases the capacity to penetrate the leaf and, herewith, the uptake potential[65]. There are formulations of solid water-soluble fertilizers with high percentages of P2O5 (up to 45%). Application rates need to be modest to prevent the scorching of leaves. There is also the limited uptake capacity which means that application rates of above 4 kg/ha do not contribute to further increased uptake and higher yield. During the second development phase (8−72 weeks), the cassava plant experiences rapid growth in its stems and leaves, alongside the enlargement of the tuber that was formed in the previous phase. Cassava recovers 57% of applied nitrogen (N), 23% of phosphorus (P), and 51% of potassium (K) nutrients[66].There could be several foliar products if a product is developed for each of the nutrients needed for cassava. It would allow for precise determination of the application rate for each of the nutrients, but at the same time very impractical. In order to reduce the range of these products, composite formulation is advisable where possible. What comes to mind as the most practical combination is that which contains P, S and micronutrients. The possible consequences in connection with the optimum time of application for each of the nutrients need to be investigated. There are also considerations in connection with possible interactions between the chemical compounds that may result in nutrients being immobilized (due to crystallization or compounds becoming insoluble). This may be the case with P and Zn, Fe and Zn and others. However, Ca, Mg, and S could be easily combined into one product. Putting too many macronutrients (N, P, and K) in one formulation will raise the question about meeting the required application rates for all of them. In the context of Nigeria, emphasis should be on P and S, with N and K that can easily be applied through readily available compound fertilizers and urea. The source of the materials for the formulation is also important. For instance, the use of potassium chloride is not always advisable because of the detrimental impact of the chloride ions on crop and on the soil[65].

-

To achieve optimal cassava growth, understanding its varying nutrient requirements at different growth stages and across agroecological zones is essential. Utilizing specialized foliar fertilizers tailored to meet these specific needs provides cassava with precise nutrients, promoting robust crop health and higher yields. We have shown that nutrient recovery efficiencies for foliar fertilizers vary depending on the nutrient, formulation, and application method. For example, boron may show low recovery rates, while zinc can exhibit up to 20% efficiency, highlighting the need to optimize formulation, concentration, timing, and frequency of application for maximum nutrient uptake. Given cassava's phosphorus requirement of 2 kg per ton of tuber, coupled with phosphorus fixation in the soil, foliar application of phosphorus presents a promising solution that warrants further investigation. Additionally, sulphur, required in smaller amounts, is most effective when combined with multi-nutrient fertilizers. In the Nigerian context, combining sulphur with foliar phosphate fertilizers may offer optimal results for cassava production. Further research would be needed to validate the potential of foliar fertilization for specific cassava growth stages in different agroecological zones on farmers fields. Future studies could also investigate the economic feasibility of foliar fertilizers for smallholder farmers and explore the development of multi-nutrient foliar formulations tailored to cassava's unique requirements.

The study was funded by Saro-Agrosciences Ltd.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: both Mesele SA and Huising EJ conceptualized the work and jointly wrote the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Mesele SA, Huising EJ. 2025. Enhancing cassava productivity in Nigeria: the role of foliar fertilization in addressing nutrient deficiencies and agroecological challenges. Circular Agricultural Systems 5: e006 doi: 10.48130/cas-0025-0003

Enhancing cassava productivity in Nigeria: the role of foliar fertilization in addressing nutrient deficiencies and agroecological challenges

- Received: 24 October 2023

- Revised: 19 December 2024

- Accepted: 14 January 2025

- Published online: 30 April 2025

Abstract: Fertilizer recommendations in Nigeria typically follow a one-size-fits-all approach, which fails to address the diverse agroecological and soil-related constraints. Foliar fertilizers are seldom used, and when used, they are often limited to applying micronutrients such as zinc, boron, or copper. Micronutrient application in cassava cultivation has not received adequate attention, despite widespread deficiencies leading to significant yield losses. Studies have shown that nutrient limitations account for approximately 55.3% of the total cassava yield gap in Nigeria. Given Nigeria's diverse soil and climatic conditions, there is substantial potential for utilizing foliar fertilizers to enhance nutrient management and improve cassava productivity. A major limitation in providing a well-balanced nutrient supply for cassava is the possibility of nutrient interactions that may cause nutrient precipitation or insolubility. We identify where, when, and what type of foliar fertilizers will be most beneficial, focusing on the technical and management aspects of foliar fertilizer use. Considering several factors we conclude that among the different aspects of integrated nutrient management, foliar fertilization in the context of supplementary nutrient application holds the highest potential in Nigeria.

-

Key words:

- Cassava /

- Fertilizer use /

- Foliar fertilizer /

- Nutrient requirement /

- Soil health