-

Skeletal muscles are vital for musculature control, locomotion, body heat regulation, physical strength, and body metabolism. Muscle loss is a feature of skeletal muscular atrophy brought on by an imbalance in the synthesis and breakdown of proteins[1]. In addition to the skeletal muscle atrophy associated with aging (sarcopenia) and cancer (cachexia), gradual skeletal muscle mass decline is a significant, often overlooked, comorbidity observed in various metabolic and chronic disorders such as obesity and diabetes[2]. Currently, two of the most common non-communicable diseases harming people's health worldwide are diabetes and obesity. By 2030, the number of diabetic and obese adults is projected to be 643 and 573 million, respectively. The widespread prevalence of diabetes and obesity globally increases the likelihood of skeletal muscle atrophy. The Korean Sarcopenic Obesity Study examined a large number of people suffering from metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes, indicating that most of the patients with decreased muscle mass were overweight or obese[3]. Skeletal muscle atrophy caused by glucolipid metabolic disorders decreases the life quality of patients and the ability to move around, adding to the financial strain on the healthcare system and raising rates of morbidity and mortality.

Exercise is a crucial non-pharmacological intervention for increasing muscle mass and enhancing muscular function[4]. However, for the elderly and other populations experiencing muscle function decline, engaging in physical exercise may be challenging or even infeasible. The pharmacological therapeutic approaches for skeletal muscle atrophy include improving appetite, encouraging anabolism in muscular tissue (androgen or androgen receptor modulator, ghrelin and its receptor agonist, β2-adrenoceptor agonists, and enzyme inhibitors), and inhibiting cytokine signaling pathways linked to the development of muscular atrophy[5]. Emerging therapeutics show potential in enhancing muscle mass among patients, however, the discernible impact on muscle function is limited, and the accompanying toxicities associated with these medications serve to constrain their clinical utility even further[6]. It is noteworthy that there are few clinical trials focusing on medications targeting skeletal muscle atrophy resulting from glucolipid metabolic disorders. Consequently, to counteract the skeletal muscle atrophy caused by glucolipid metabolic disorders, it is imperative to clarify the relevant mechanisms and identify novel targets and medications.

Phytochemicals, derived from edible and medicinal plants, are commonly used for treating glucolipid metabolic disorders and other diseases due to their minimal adverse impact on humans[7]. Research suggests that eugenol, the primary aromatic compound in clove oil, can ameliorate gut dysbiosis and inhibit obesity in mice exposed to a high-fat diet (HFD)[8]. Some phytochemicals, such as polyphenols (curcumin, eugenol, and resveratrol), flavonoids (apigenin, puerarin, and quercetin), and terpenoids and alkaloids (α-cedrene and α-ionone), as well as plant extracts, have been shown to alleviate glucolipid metabolic disorder-induced skeletal muscle atrophy[9]. Therefore, supplementing with phytochemicals appears to be a promising new treatment for the muscular atrophy brought on by glucolipid metabolic diseases.

The research progress on the beneficial effects and mechanisms of phytochemicals in treating or preventing skeletal muscle atrophy brought on by glucolipid metabolic disorders is summarized in this review. The complex mechanism of skeletal muscle atrophy, the poor bioavailability, the structure-activity relationship, and the potential toxicity of phytochemicals are discussed, along with their current and future implications. The ultimate goal of this work is to provide fresh perspectives on possible therapeutic or preventive strategies (dietary phytochemical intervention) for clinically managing skeletal muscle atrophy.

-

Research papers and patents that addressed the effects and mechanisms of phytochemical intervention on skeletal muscle wasting were collected using search engines, such as Wiley, Springer, Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed with no language and published year limits applied. These searches were conducted using keywords including skeletal muscle atrophy, muscle mass, protein synthesis/degradation, muscle strength, diabetes, obesity, glucolipid metabolic disorders, phytochemicals, plant extracts, nutraceutical, nutrient, molecular mechanisms, oxidative stress, inflammation, and microbiota. The identified articles were examined, and the pertinent citations within them were also reviewed. The clinical trials on the beneficial effects of phytochemicals on skeletal muscle health were collected from ClinicalTrials.gov with no time frame limits.

-

Skeletal muscles serve as the protein storage system of the body and are vital for maintaining lipid and glucose balance. An increase or decrease in muscle mass can impact overall metabolism, movement, eating, and breathing. Contrarily, diseases that cause breakdown, such as organ failure, obesity, diabetes, infections, and cancer, or a lack of activity or use, encourage an overall loss of organelles, proteins, and cytoplasm, which lowers the volume of cells and results in atrophy. The alteration of signaling pathways, which ultimately leads to organelle and protein turnover, is influenced by growth factors and cytokines, as well as mechanical, oxidative, nutritional, and energy stressors. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) is a powerful anabolic factor that sustains the growth of muscles and organisms. It binds to the IGF1 receptor, activating a phosphorylation event cascade that promotes protein synthesis via positive PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway modulation[10]. Myostatin is widely recognized as the most prominent member of this superfamily within the muscle domain, mostly attributed to the hypermuscularity observed in mice lacking myostatin. Myostatin activates the Smad2/3 and transcription factors FoxOs to ultimately inhibit muscle growth[11]. Ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome represent major cellular degradation systems. Atrogin-1/MAFbx and MuRF1, the first ubiquitin ligases linked to muscle loss, are regarded as key muscle atrophy regulators. Likewise, many proteins linked to autophagy, such as BNIP3l/Nix, BNIP3, Parkin, PINK1, Optineurin, NBR1, p62, Gabarap, and LC3, become trapped in the autophagosome during the formation of vesicles and are consequently eliminated in the fusion of the autophagosome and lysosome. The pro-inflammatory cytokine impact, including IL6 and TNF-α, on muscle atrophy is mediated by the transcription factor NF-κB, primarily responsible for inflammation and immunity regulation. Inflammation can also indirectly trigger skeletal muscle atrophy by altering the metabolic state of distal tissues[12]. Oxidative stress is facilitated by an imbalance between the natural production of free radicals in the body and its capacity for scavenging them. Studies have shown that elevated oxidative stress may activate muscle atrophy-related signaling pathways, triggering cellular skeletal muscle degeneration mechanisms in various diseases[13]. Many catabolic conditions cause dysregulation in the mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins and quality control, ultimately leading to muscle atrophy by increasing oxidative stress, apoptosis, or cell death. In addition, novel strategies for controlling and orchestrating complex skeletal muscle atrophy networks are continuously emerging. A comprehensive understanding of the gut-muscle axis can help elucidate the fundamental interplay among the gut microbial metabolites, gut microbiota, and skeletal muscle mass, along with the association between these entities[14].

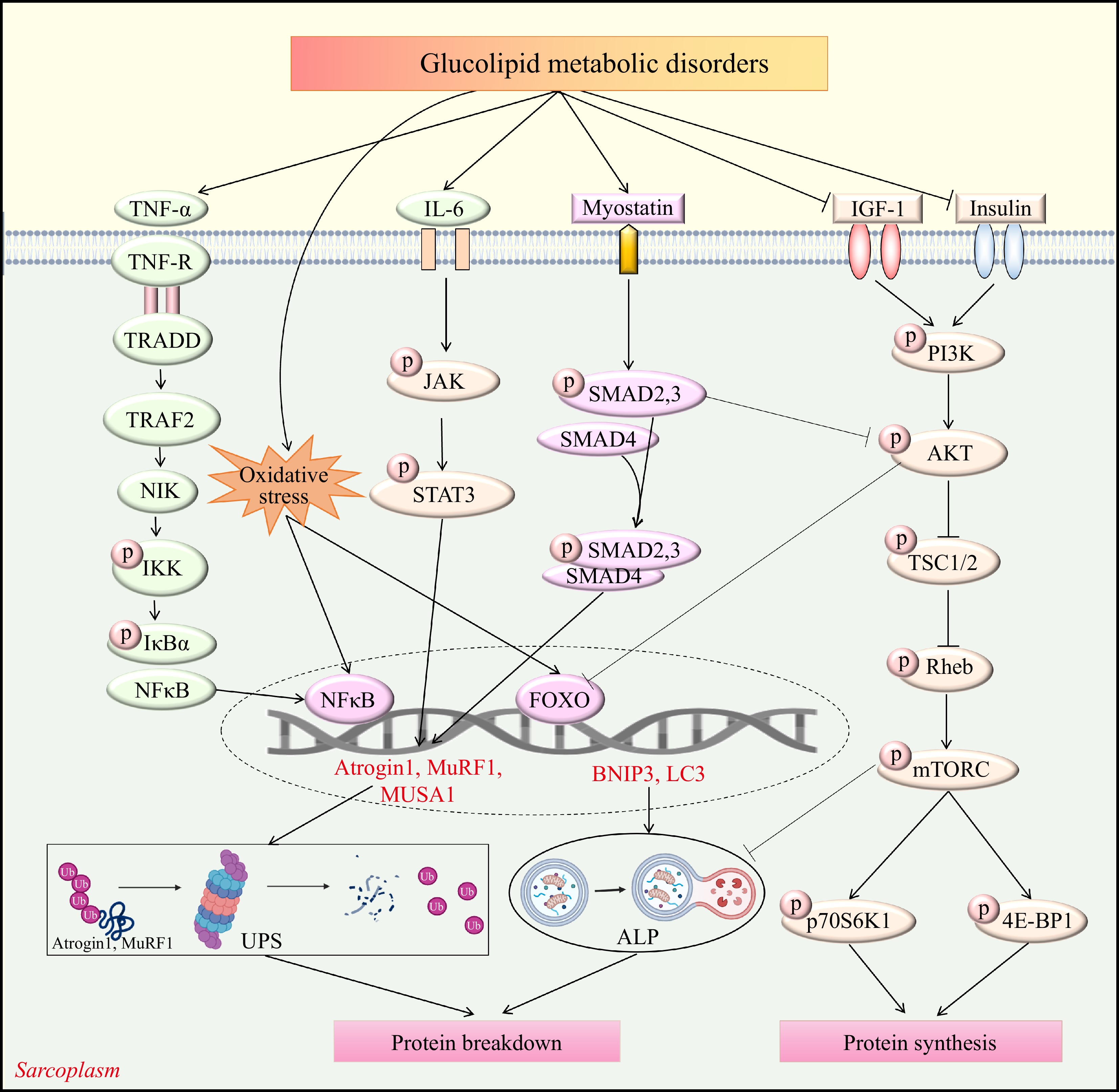

Among other factors, dietary, environmental, psychological, and genetic factors can result in glucose metabolism disorders, which can lead to fatty liver, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia. Due to the crucial role of glucolipid metabolism in the quality and function of skeletal muscles, disruption can result in muscle atrophy, posing a serious risk to human health and significantly increasing global health and medical costs. The molecular mechanisms underlying diabetic and obese muscle atrophy are highly complex (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the signaling pathways associated with glucolipid metabolic disorders-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Akt, Protein kinase B; ALP, Autophagy-lysosome pathway; Atrogin-1, Muscle Atrophy F-box protein 1; BNIP3, BCL2 interacting protein 3; FOXO, Forkhead box O; JAK, Janus kinase; IGF-1, Insulin-like growth factor 1; IKK, IkappaB Kinase; IL-6, Interleukin-6; IκB-α, Nuclear factor kappa-B inhibitor α; LC3, microtubule-associated proteins light chain 3; mTORC, Mammalian target of rapamycin complex; MuRF1, Muscle RING-finger protein-1; MUSA1, muscle ubiquitin ligase of the SCF complex in atrophy-1; NFκB, Nuclear factor kappa-B; NIK, Nuclear factor kappa-B-inducing kinase; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; p70S6K, Ribosomal protein S6 kinase; Rheb, Guanosine triphosphate Phosphohydrolase ras homolog enriched in brain; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TNF-R, Tumor necrosis factor-receptor; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-α; TRADD, Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 -associated death domain protein; TRAF2, Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2; TSC1/2, Tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2; UPS, Ubiquitin proteasome system; 4E-BP1, Rapamycin complex and 4E binding protein-1.

Diabetes is a persistent metabolic condition distinguished by heightened levels of blood glucose as a result of either insufficient insulin production or resistance, often leading to secondary complications in organs, such as the brain, heart, kidneys, eyes, and skeletal muscle[15]. The diabetic effect on skeletal muscle primarily manifests as muscle-fiber phenotype alterations from slow to fast twitches, energy metabolism disorders, and muscle weakness, known as diabetic muscular atrophy, severely affecting the life quality of patients. The inhibition of protein synthesis via the suppression of the IGF-1-PI3K-AKT/PKB-mTOR pathway, as well as the inactivation of the autophagy-lysosome pathway and ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) through the IGF-1-AKT-FoxO signaling pathway, represent mechanisms by which insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) promotes muscle atrophy[16]. Muscle atrophy brought on by type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is facilitated by the protein degradation pathway governed by FoxO[17]. Furthermore, muscle wasting can be induced in diabetic patients by gut dysbiosis, inflammatory response, and oxidative stress. A diabetic mouse model induced by streptozotocin (STZ) confirmed that hyperglycemia promoted skeletal muscle wasting via an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 1/Krüppel-like factor 15 pathway containing a WW domain[18].

Obesity is a complex disease involving unbalanced energy intake that leads to abnormal or excessive fat accumulation[8]. It is a separate risk factor for the onset of neurological, respiratory, gastrointestinal, reproductive, and psychosocial complications, as well as chronic diseases like diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases. Obesity development is also closely related to the onset of skeletal muscle atrophy. Research showed that HFD-induced obese mice developed typical muscle atrophy features, including weakness, lower muscle mass, and reduced fiber diameters[19]. The regulation of gut dysbiosis and the actions of leptin, testosterone, estrogen, Ca2+, vitamin D, Insulin/IGF, IL-6, exogenous GC, myostatin, AGEs, Ang II, and TNF-α represent some of the mechanisms underlying the skeletal muscle atrophy caused by obesity[20]. In addition, HFD muscle atrophy models indicated that ectopic adipose deposition (intermuscular and intramuscular lipids) could cause biological skeletal muscle dysfunction, including insulin resistance, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses[21]. In particular, mice injected intramuscularly with glycerol displayed a significant deficit in peak tetanic tension, which was strongly associated with intramuscular adipose tissue quantity, indicating that intramuscular adipose tissue infiltration independently impacted muscle contraction[22].

Glucolipid metabolic disorder-related muscle atrophy currently lacks effective intervention strategies. Preclinical investigations showed that suppressing muscle atrophy pathway components effectively prevented and, in certain instances, reversed muscle wasting in mouse models. However, this did not result in the successful implementation of muscle weakness treatment in clinical studies.

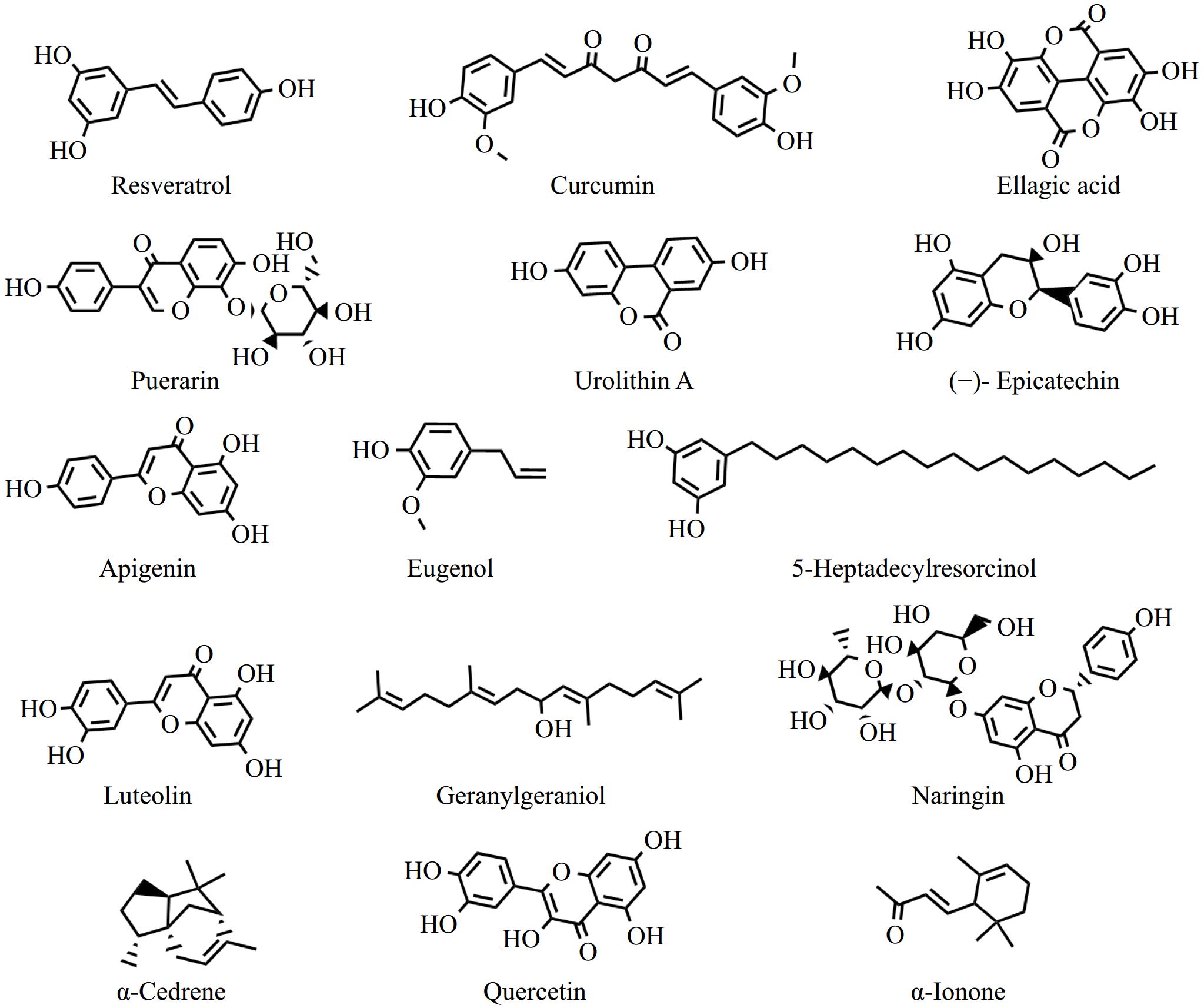

-

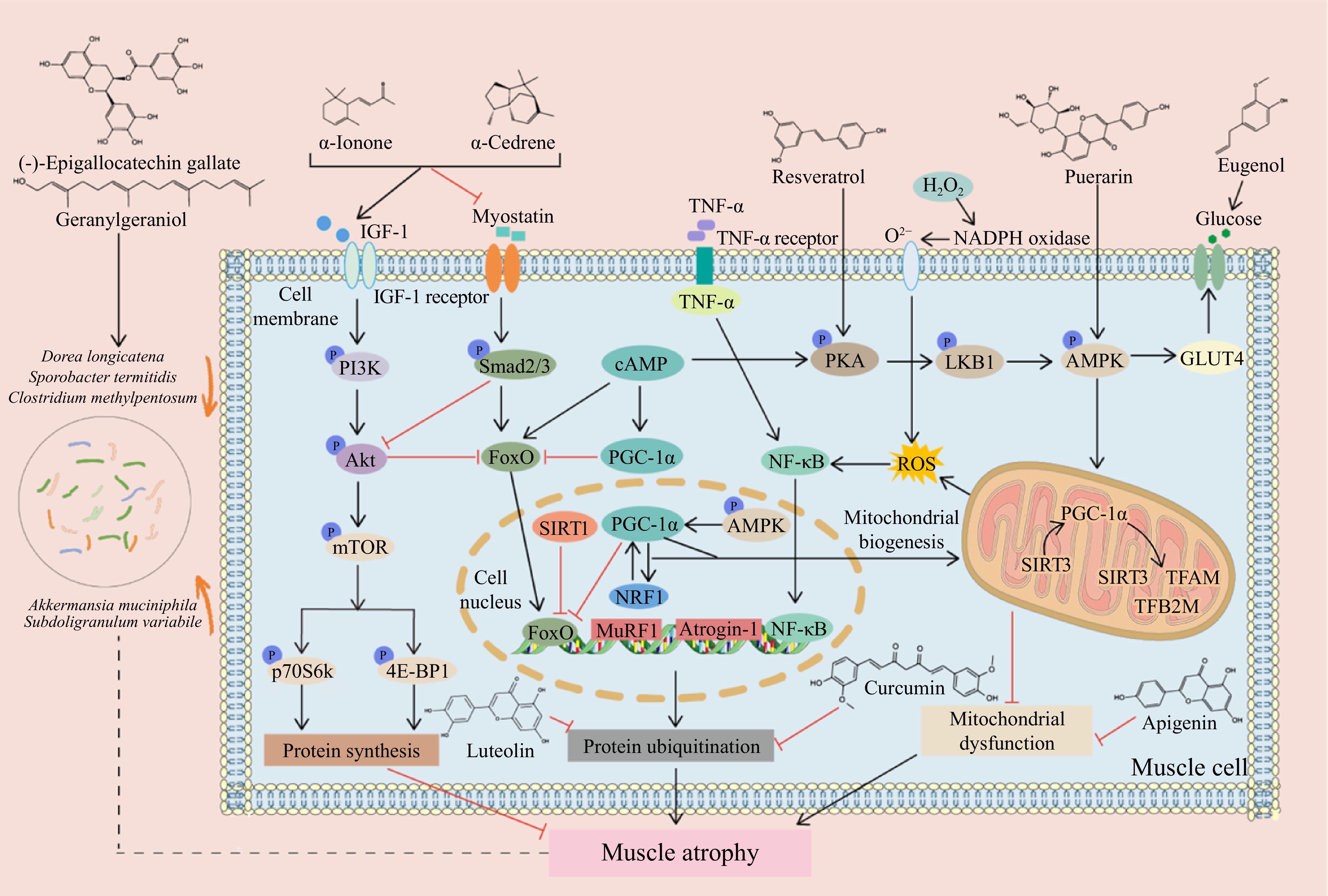

Plants produce phytochemicals to help them combat fungal, bacterial, and viral infections, and resist ingestion by animals and insects. Phytochemicals are classified into polyphenols, isoprenoids, phytosterols, saponins, dietary fibers, and specific polysaccharides[23]. According to recent research, many phytochemicals can improve muscle quality and function, boost myoblast differentiation, enhance mitochondrial biogenesis, and lower skeletal muscle inflammation to reduce the atrophy of muscle caused by glucolipid metabolic disorders[4,24]. This section elucidates the mechanism behind the protective effect of phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and plant extracts, on muscle atrophy in glucolipid metabolic disorders. A thorough summary of recent developments in vivo on the anti-muscle atrophy characteristics of phytochemicals and plant extracts is provided in Tables 1 and 2. The chemical structures of the representative compounds are shown in Fig. 2. The general mechanisms underlying the anti-muscle atrophy effect of phytochemicals are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Table 1. The effects and mechanisms of phytochemicals on muscle atrophy induced by glucolipid metabolic disorders.

Phytochemicals Main source Models & inducers Dose & duration Main effects Mechanisms Ref. Phenols Resveratrol 3,4',5-Trihydroxy-trans-stilbene Peanuts, pines, grape skin C57BL/6 mice; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (200 mg/kg BW) 100 mg/kg/d; 8 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA, myofiber size distribution, running distance ↑Mitochondrial biogenesis

↓Mitophagy, mitochondrial fission and fusion[25] SD rats; HFD for 20 weeks 2.0%; 10, 20 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial function

↓Oxidative stress[26] C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 8 weeks 0.4%; 8 weeks ↑Tibialis anterior muscle mass ↑Mitochondrial biogenesis [27] Curcumin 1,7-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,6-diene-3,5-dione Turmeric (Curcuma longa) C57BL/6J mice; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (200 mg/kg) 1500 mg/kg/d;

2 weeks↑Muscle mass, myofiber CSA ↓Protein ubiquitination [28] Tocotrienols 2-Methyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltrideca-3,7,11-trien-1-yl)chroman-6-ol Annatto, palm oil, rice bran oil, barley C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 14 weeks 400 mg tocotrienols/kg diet; 14 weeks ↑Relative muscle mass, myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial enzyme activity

↑Oxidative stress[29] Oligonol / Lychee fruit, green tea db/db mice 20, 200 mg/kg; 10 weeks ↑Myofiber CSA, myofiber size distribution ↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation [30] 5-heptadecylresorcinol 5-heptadec-1-enylbenzene-1,3-diol Rye, wheat C57 BL/6J mice; HFD for 16 weeks 30, 150 mg/kg; 16 weeks ↑Running time, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial biogenesis [31] Green tea polyphenols / Green tea C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 14 weeks 0.5% (w/v) green tea polyphenols in drinking water; 14 weeks ↑Relative muscle mass, myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial enzyme activity

↑Oxidative stress[29] C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 14 weeks 0.5% w/v green tea polyphenols in water; 14 weeks ↑Relative muscle mass, myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial enzyme activity

↑Oxidative stress Alteration of gut microbiota composition[32] Tannin Ellagic acid 2,3,7,8-Tetrahydroxychromeno[5,4,3-cde]chromene-5,10-dione Pomegranate ICR mice; STZ (not reported) 100 mg/kg/d; 8 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial function

↓Protein ubiquitination, endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis[33] Urolithin A 3,8-dihydroxy-6H-benzo[c]chromen-6-one Pomegranate fruit C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 34 weeks 50 mg/kg/d; 34 weeks ↑Grip strength, running distance ↑Mitochondrial function [34] (−)- Epicatechin (2R,3R)-2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)chroman-3,5,7-triol Cacao C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 15 weeks 2 mg/kg BW; 5 weeks ↑Physical performance ↓Protein ubiquitination [35] Phenylpropanoids Eugenol 2-Methoxy-4-allylphenol Clove, cinnamon C57BL/6N mice; 8 weeks HFD with STZ (35 mg/kg BW) twice 10, 20 mg/kg/d; 8 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber length ↑Muscle glucose uptake

↓Inflammation[36] Sinapic acid 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid Mustard seeds, rapeseed, wheat ICR mice; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (200 mg/kg) 40 mg/kg/d; 8 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial function

↓Endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis[37] Sesamin 5,5'-(1S,3aR,4S,6aR)-tetrahydro-1H,3H-furo(3,4-c)furan-1,4-diylbis(1,3-benzodioxole) Sesame seeds C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 8 weeks 0.2%; 8 weeks ↑Exercise capacity ↓Oxidative stress [38] Magnesium lithospermate B magnesium;(2R)-2-[(E)-3-[(2S,3S)-3-[(1R)-1-carboxylato-2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)ethoxy] carbonyl-2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-7-hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-1-benzofuran-4-yl]prop-2-enoyl]oxy-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)propanoate Danshen C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 17 weeks 100 mg/kg BW/d; 17 weeks ↑Relative muscle mass, myofiber CSA ↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation, PI3K/Akt/FoxO signaling [39] Flavonoids Puerarin 7-hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-8-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]chromen-4-one Pueraria lobate SD rats; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (65 mg/kg) 100 mg/kg; 8 weeks ↑Muscle strength, muscle tissue index, muscle mass, myofiber CSA, distribution ↑Transformation from slow-twitch muscle to fast-twitch muscle

↓Protein ubiquitination[40] Bavachin 7-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-6-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)chroman-4-one Psoralea corylifolia L. seed db/db mice 10 mg/kg; 40 d ↑Grip strength, myofiber CSA, myofiber size distribution ↑Mitochondrial function, mitophagy

↓Inflammation[41] Corylifol A 3'-Geranyl-4',7-dihydroxyisoflavone Psoralea corylifolia L. seed db/db mice 10 mg/kg; 40 d ↑Grip strength, myofiber CSA, myofiber size distribution ↑Mitochondrial function, mitophagy

↓Inflammation[41] Apigenin 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one Parsley, chamomile, celery C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 9 weeks 0.1%; 8 weeks ↑Myofiber CSA, running distance ↑Mitochondrial biogenesis

↓Mitochondrial dysfunction[42] Quercetin 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one Apples, buckwheat, onions, citrus fruits C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 9 weeks 0.05%, 0.1%; 9 weeks ↑Muscle mass, myofiber diameter ↓Inflammation, protein ubiquitination [43] Luteolin 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one Parsley, peppermint, celery seeds C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 20 weeks 0.01%; 20 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA, muscle cell count ↓Inflammation, protein ubiquitination [44] Naringin 4',5,7-Trihydroxyflavanone-7-rhamnoglucoside Pomelo,

grapefruitsSD rats; HFD for 8 weeks 50, 100 mg/kg BW; 8 weeks ↑Muscle mass, myofiber CSA, myofiber diameter ↑Insulin resistance

↓Oxidative stress, protein ubiquitination[45] Terpenoids Geranylgeraniol (2E,6E,10E)-3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadeca-2,6,10,14-tetraen-1-ol Palm, ginger, certain essential oils SD rats; HFD for 8 weeks with single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (35 mg/kg BW) 800 mg/kg; 8 weeks ↑Myofiber CSA ↑Mitochondrial

quality[46] C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 14 weeks 400 mg geranylgeraniol/kg diet; 14 weeks ↑Relative muscle mass, myofiber CSA Alteration of gut microbiota composition [32] α-Cedrene (1S,2R,5S,7S)-2,6,6,8-tetramethyltricyclo[5.3.1.0(1,5)]undec-8-ene Cupressus, Juniperus species C57BL/6N mice; HFD for 10 weeks 200 mg/kg BW; 10 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling [47] α-Ionone 4-(2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-2-en-1-yl)but-3-en-2-one Violets, blackberries, plums C57BL/6N mice; HFD for 9 weeks 0.1% α-ionone; 10 weeks ↑Muscle strength, muscle mass, myofiber diameter ↑cAMP signaling

↓Protein ubiquitination[48] Alkaloids Boldine 2,9-Dihydroxy-1,10-dimethoxyaporphine Boldo SD rats; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (45 mg/kg) 50 mg/kg/d; 3 weeks ↑Myofiber CSA / [49] Magnoflorine (6aS)-1,11-dihydroxy-2,10-dimethoxy-6,6-dimethyl-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo(de,g)quinolinium Tinospora cordifolia Wister rats; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (70 mg/kg BW) 2 mg/kg/d; 3 weeks ↑Muscle mass, myofiber CSA, myofibrils integrity ↑Akt/FoxO signaling

↓Oxidative stress, protein ubiquitination, autophagy[50] Saponin Compound K 20-O-beta-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol Ginsenoside C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 8 weeks 1 mg/kg/d; 8 weeks ↑Myotube diameter ↓Endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy [51] Akt, Protein kinase B; BW, Body weight; CSA, Cross-sectional area; CREB, cAMP Response Element-Binding protein; FoxO, Forkhead box O; HFD, High fat diet; ICR, Institute of Cancer Research; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKA, Protein kinase A; SD, Sprague Dawley; STZ, Streptozotocin; ↑, Increase or promote; ↓, Decrease or inhibit. Table 2. The effects and mechanisms of plant extracts on muscle atrophy induced by glucolipid metabolic disorders.

Plant extract Models & inducers Dose & duration Main effects Mechanisms Ref. Aged black garlic, aged black elephant garlic C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 10 weeks 100 mg/kg/d; 10 weeks ↑Relative muscle mass ↓Protein ubiquitination [72] Artemisia dracunculus L.ethanolic extract KK-Ay mice 1% w/w; 12 weeks / ↓Protein ubiquitination [73] Black ginseng extract ICR mice; STZ (60 mg/kg BW) twice 300, 900 mg/kg/d;

5 weeks↑Myofiber size

↓Muscle fibrosis↑mTOR signaling [69] Brazilian green propolis db/db mice 2%; 8 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength ↑Mitochondrial function

↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation

Alteration of gut microbiota composition[74] Chrysanthemi zawadskii var. latilobum C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 9 weeks 125, 250 mg/kg; 8 weeks ↑Grip strength, myofiber size ↑Mitochondrial function

↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation[64] Codonopsis lanceolata C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 9 weeks CL50, 100, 200 mg/kg;

6 weeks↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑PI3K/Akt signaling, lipid metabolism

↓Protein ubiquitination[68] Ecklonia stolonifera extract C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 6 weeks 150 mg/kg/d; 6 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA, myofiber diameter ↑Insulin signaling, mitochondrial biogenesis [56] Chinese raspberry (Rubus chingii Hu) fruit extract C57BL/6 mice; STZ (50 mg/kg BW) consecutively for 5 d 30 mg/kg BW; 18 d ↑myofiber CSA ↑Akt signaling

↓Protein ubiquitination[58] Fuzhuan brick tea C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 12 weeks 100, 200 mg/kg;

12 weeks↑Muscle mass, myofiber CSA, grip strength, running capacity ↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation

↑Lipid metabolism, mitochondrial functions[59] Gintonin- rich fraction ICR mice; HFD for 6 weeks 50, 150 mg/kg/d;

6 weeks↑Grip strength, muscle mass, myofiber size ↑Mitochondrial biogenesis

↓Protein ubiquitination[75] Green tea extracts SAMP8 mice; HFD for 4 months 0.5%; 4 months ↑Muscle mass ↑Insulin signaling [55] Juzentaihoto hot water extract ICR mice; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (150 mg/kg) 4.0% w/w; 35 days ↑Rotarod tolerance time ↓Oxidative stress [76] Juzentaihoto KK-Ay mice 4.0% w/w; 56 d ↑Muscle mass, myofiber CSA, rotarod tolerance time ↓Insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, protein ubiquitination [77] Lespedeza bicolor extract C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 9 weeks with STZ (30 mg/kg BW) twice 100, 250 mg/kg BW;

12 weeks↑Muscle mass, myofiber CSA ↑Energy metabolism

↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation[78] Licorice flavonoid oil KK-Ay mice 1, 1.5 g/kg BW; 2 weeks ↑Muscle mass ↑mTOR/S6K signaling

↓Protein ubiquitination[65] Liuwei dihuang water extract C57BL/6 mice; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (150 mg/kg) 7.5, 15, 30 mg/kg/d;

1 week↑Muscle mass, grip strength / [79] Lonicera caerulea extract C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 8 weeks 100, 200, 400 mg/kg;

8 weeks↑Muscle volume, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↓Protein ubiquitination [67] Lithospermum erythrorhizon extract C57BL/6N; HFD for 8 weeks 0.25%; 10 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, exercise endurance capacity, myofiber CSA ↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation

↑Mitochondrial Biogenesis[71] Morinda officinalis root extract C57BL/6N mice; HFD for 8 weeks with single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (120 mg/kg BW) 100, 200 mg/kg BW;

4 weeks↑Myofiber CSA ↑Myogenetic proteins, biogenetic proteins

↓Protein ubiquitination[80] Non-extractable fractions of dried persimmon Wistar rats; single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (50 mg/kg BW) 5%; 9 weeks ↑Myofiber CSA ↓Oxidative stress [60] Omiza extract C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 9 weeks 0.25%; 8 weeks ↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑Akt/mTOR signaling

↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation[61] Panax ginseng berry extract C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 9 weeks 50, 100, 200 mg/kg;

4 weeks↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↑PI3K/Akt Signaling

↓Protein ubiquitination[70] Radix Pueraria lobata C57BL/6 mice; HFD for 16 weeks 100,300 mg/kg; 16w eeks ↑Relative muscle mass, myofiber diameter ↑Mitochondrial biogenesis, energy metabolism [63] Saikokeishikankyoto extract KK-Ay mice 2%, 4% mixed feed;

56 d↑Muscle wet mass, muscle fiber content, myofiber CSA ↓Protein ubiquitination, inflammation [53] Schisandrae chinensis fructus extract C57BL/6 mice;single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (150 mg/kg) 250, 500 mg/kg BW;

6 weeks↑Muscle mass, grip strength, myofiber CSA ↓Protein ubiquitination, CREB/KLF15, autophagy-lysosomal [62] Tocotrienol-rich fraction C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 12 weeks with STZ (100 mg/kg) twice 100, 300 mg/kg BW;

12 weeks↑Myofiber size ↑AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling

↓Inflammation, apoptosis[54] Zhimu-Huangbai herb-pair C57BL/6J mice; HFD for 9 weeks with single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (100 mg/kg BW) 2.6 g/kg BW; 6 weeks ↑Muscle strength, coordination, muscle mass, myofiber CSA ↑IGF-1 signaling [81] Akt, Protein kinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; BW, Body weight; CSA, Cross-sectional area; CREB, HFD, High fat diet; ICR, Institute of Cancer Research; IGF-1, Insulin-like growth factor 1; KLF15, Krüppel-like factor 15; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin; PGC-1α, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; SIRT1, Sirtuin 1; STZ, Streptozotocin; ↑, Increase or promote; ↓, Decrease or inhibit.

Figure 2.

The chemical structures of representative phytochemicals with anti-skeletal muscle atrophy activity.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of phytochemicals to combat muscle atrophy in glucolipid metabolic disorders. Phytochemicals promote or inhibit signaling pathways, mitigating muscle atrophy induced by glucolipid metabolic disorders. Akt, Protein kinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; Atrogin-1, Muscle Atrophy F-box protein 1; FoxO, Forkhead box O; GLUT4, Glucose transporter 4; IGF-1, Insulin-like growth factor 1; LKB1, Liver kinase B1; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin; MuRF1, Muscle RING-finger protein-1; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa-B; NRF1, Nuclear respiratory factor 1; PGC-1α, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKA, Protein kinase A; p70S6K, Ribosomal protein S6 kinase; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; SIRT1, Sirtuin 1; SIRT3, Sirtuin 3; TFAM, Mitochondrial transcription factor A; TFB2M, Mitochondrial transcription factor B2; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-α; 4E-BP1, Rapamycin complex and 4E binding protein-1.

Phenols

-

A number of in vivo investigations demonstrated the inhibitory effect of resveratrol, an antioxidant naturally present in red wine, grape skins, pines, and peanuts, on protein degradation, alleviating skeletal muscle atrophy. It elevated gastrocnemius muscle weight and reduced plasma branched-chain amino acid levels in STZ-induced diabetic Sprague-Dawley rats by downregulating the NF-κB activity[52]. In a diabetic mouse model, resveratrol treatment mitigated the decline in grip strength, running distance, muscle fiber size, and skeletal muscle weight. These positive outcomes are attributed to enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial autophagic activation inhibition in skeletal muscle, and excessive mitochondrial fusion and fission suppression[25]. In addition to diabetes-related muscle atrophy, resveratrol also improved muscle function in HFD-fed obese and aged rats, including increasing muscle weight, grip strength, and myofiber cross-sectional area (CSA) which was partially mediated via oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction reversal and protein kinase A/PKA/liver kinase B1/AMPK pathway modulation[26]. It is pointed out that 0.4% (w/w) resveratrol supplementation for eight weeks increased the tibialis anterior muscle weight in obese mice[27]. Of note, in another study, 0.4% (w/w) resveratrol was even used as a positive control to evaluate the preventative effects of plant extracts on diabetes-induced skeletal muscle atrophya[53]. These results highlighted the promising application of dietary supplementation of resveratrol as a therapy against skeletal muscle atrophy caused by diabetes or obesity.

Curcumin is a natural phenolic antioxidant extracted from the rhizome of turmeric, zedoary, mustard, curry, and turcuma. Owing to its myriad of health-promoting properties, curcumin has garnered global recognition. Curcumin effectively mitigated the decrease in skeletal muscle weight, body weight, and cellular CSAs of the skeletal muscle in mice with T1DM induced by STZ[28]. This was achieved by the inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, and protein ubiquination.

Tocotrienols are vitamin E compounds mainly present in barley, coconut oil, rice bran, palm oil, and annatto, with potential health-protective properties. Dietary supplementation of tocotrienol extracted from annatto for fourteen weeks increased muscle fiber CSA, presenting a therapeutic strategy for preventing the muscle atrophy frequently observed in obese mice displaying high blood glucose levels and insulin resistance. High key rate-limiting mitochondrial enzyme levels and partial oxidative stress attenuation may contribute to this phenotypic improvement, albeit via different mechanisms[29]. Moreover, tocotrienol-rich fractions have the potential to increase the weight of skeletal muscle and the size of muscle fibers in diabetic mice, consequently reducing the skeletal muscle damage caused by high blood glucose levels. The molecular mechanisms for these changes were partially revealed by the reduction of skeletal muscle proteins linked to apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress[54].

Oligonol is a mixture of low molecular-weight polyphenols derived from lychees. Dietary oligonol supplementation for ten weeks substantially elevated the average CSA and prevented a shift in fiber size distribution towards smaller fibers by inhibiting Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 expression in db/db mice[30].

Alkylresorcinols, natural compounds mainly found in the bran portion of rye and wheat, serve as biomarkers of whole grain consumption. Studies showed that 16 weeks of dietary supplementation with 5-heptadecylresorcinol — displaying the highest anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-obesity activity among the identified alkylresorcinol homologs — increased running time and grip strength in HFD-fed mice by enhancing PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis, contributing to muscle atrophy prevention[31].

As a nonfermented tea, green tea has gained popularity due to the significant health benefits of its polyphenol content. In HFD-fed senescence-accelerated mouse-prone-8 mice, supplementation with 0.5% (w/w) green tea extract significantly counteracted the reduction in muscle mass and insulin sensitivity[55]. It has been reported that green tea polyphenols could improve the skeletal muscle metabolism of obese mice[29]. This was achieved by decreasing lipid peroxidation, enhancing glucose homeostasis, and improving the activity of enzymes that regulate the rate of oxidative phosphorylation. Recent reports also highlighted the positive impact of dietary green tea polyphenol supplementation on muscle health in HFD-fed mice, increasing the relative soleus muscle weight and CSA of gastrocnemius muscles by promoting mitochondrial enzyme activity and inhibiting oxidative stress of skeletal muscle. Furthermore, the mitigatory effect of green tea polyphenols on skeletal muscle wasting is linked to the reshaping of the composition of gut microbiota[32].

Ecklonia stolonifera, a perennial brown marine alga from the Laminariaceae family, is known for its polyphenol-rich composition and exhibits many bioactivities. It has been demonstrated that Ecklonia stolonifera extract administration notably improved the gastrocnemius muscle diameters, CSAs, gastrocnemius muscle mass/body mass ratio, and grip strength of obese mice[56]. Additionally, an upregulation was also evident in myogenic protein production after Ecklonia stolonifera extract intervention.

Tannin

Hydrolyzable tannins

-

Ellagitannins and ellagic acid are hydrolyzable tannins widely found in pomegranates, blackberries, raspberries, strawberries, walnuts, and almonds. Under physiological conditions in the body, ellagitannins undergo hydrolysis into ellagic acid which is subsequently metabolized by intestinal microbiota, yielding various types of urolithins[57]. Numerous findings suggest that the consumption of foods rich in ellagitannins, ellagic acid, and urolithins plays a crucial role in preserving skeletal muscle health.

Chinese raspberry, the fruit of Rubus chingii Hu, is an edible berry that can be consumed directly or processed into jam and juice and is abundant in ellagitannins. Treatment with 30 mg/kg Chinese raspberry extract for 18 d overturned the STZ-induced inhibition of Akt signaling and activation of protein ubiquitination, leading to the prevention of diabetes-associated muscle wasting in diabetic mice[58].

Recent studies suggested that eight-week dietary supplementation with 100 mg/kg ellagic acid enhanced the mass and myocyte CSA of gastrocnemius weight, as well as promoted grip strength to relieve muscle lesions in STZ-induced diabetic mice by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis[33].

In addition, urolithin A, a gut bacterial fermented ellagic acid product, significantly improved muscle function, yielding a 9% grip strength and 57% spontaneous locomotion increase in HFD-fed mice after 34 weeks of supplementation. These beneficial effects are related to improved mitochondrial function, as evidenced by a higher microtubule-related protein 1A/1B light-chain 3B isoform II to isoform ratio, a lower sequestosome 1 level, elevated mitochondrial autophagy transcription expression, and the induction of AMPK phosphorylation in muscle tissue[34].

Condensed tannins

-

Catechin belongs to the condensed tannin with epicatechin and epigallocatechin being the major catechin compound types, which is vital in skeletal muscle atrophy intervention as a dietary supplementation.

(−)-Epicatechin is easily obtained through the diet because of its wide distribution in tea and other foods including cocoa, vegetables, fruits, and cereals. By feeding 49-week-old naturally aging mice an HFD for 15 weeks, an obesity-related sarcopenia model was established[35]. Evaluation via hang-wire, inverted-screen, weightlifting, and forelimb strength tests indicated that (−)-epicatechin administration for five weeks improved physical performance. (−)-Epicatechin also impacted the expression of molecular growth differentiation modulators, such as myocyte enhancer factor 2A, while reducing FoxO1A and MuRF1 marker expression in the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway of the skeletal muscle. These findings prompted additional investigation into the possible medical use of (−)-epicatechin in obese- and age-related muscle loss conditions.

Epigallocatechin is a pivotal bioactive compound found in Fuzhuan brick tea, a post-fermented tea processed through fermentation by the fungus Eurotium cristatum. Following a 12-week intervention, 100 or 200 mg/kg Fuzhuan brick tea extract resulted in significantly increased myofiber CSA and skeletal muscle weights of HFD-induced obese mice, and improved grip strength and running capacity. These effects were attributed to the ability of tea extract to mitigate inflammation and downregulate atrophy-related gene expression, modulate lipid metabolism, and enhance mitochondrial function[59].

Persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) belongs to the Ebenaceae family and is notably endowed with soluble condensed tannin. It has been confirmed that the non-extractable fractions of dried persimmon also contained condensed tannin which was the same as the tannin derived from persimmon in composition by using HPLC[60]. In STZ-induced T1DM rats, dietary supplementation with 5% (w/w) non-extractable dried persimmon fractions reduces the CSA of soleus and extensor digitorum longus via oxidative stress inhibition.

Phenylpropanoids

-

Eugenol, the main component in cloves, is also found in soybeans, beans, coffee, cinnamon, basil, bananas, and bay laurel. Our recent research showed that dietary eugenol supplementation prevented HFD-induced obesity and gut dysbiosis[8]. Furthermore, oral eugenol prevented HFD/STZ-induced muscle weakness and atrophy, as shown by increased grip strength, gastrocnemius mass, and muscle fiber length, which could be attributed to its mediatory effect on glucose absorption and inflammatory response in the muscle[36].

Cereal grains contain large amounts of sinapic acid, utilized as a traditional Chinese remedy for a variety of illnesses. By increasing grip strength, gastrocnemius muscle weight, and myofiber size, sinapic acid administration prevented muscle wasting in mice with STZ-induced diabetes. Its potential ameliorative mechanism is related to the reduction of mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis[37].

Sesamin, a lignan in sesame oil and seeds, exhibits significant biological function diversity. The administration of 0.2% (w/w) sesamin derived from refined sesame seed oil mitigated the decreased exercise capacity in mice with HFD-induced diabetes[38]. This intervention reduced oxidative stress as well as promoted fat oxidation and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle.

Lithospermic acid B, also known as salvianolic acid B, is a phenolic acid compound formed by the condensation of three molecules of salvianic acid A and one molecule of caffeic acid, characterized by abundant phenolic hydroxyl groups. Magnesium lithospermate B is frequently found in the form of magnesium salt due to its inherent instability. According to reports, magnesium lithospermate B, which is the main hydrophilic constituent of Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza), effectively prevents the skeletal muscle wasting associated with obesity. This is likely achieved by preventing the muscular degradation mediated by MAFbx/MuRF-1 in obese mice exposed to an HFD diet. The potential to prevent muscle atrophy of magnesium lithospermate B may be linked to the activation of the PI3K-Akt-FoxO1 pathway and the suppression of the TNF-α/TNFRI/NF-κB pathway[39].

Schisandrin B is a major bioactive constituent of Schisandrae chinensis fructus. In obese mice fed HFD, supplementation with schisandrin B-enriched Schisandrae chinensis fructus extract resulted in increased skeletal muscle weight, enhanced skeletal muscle CSA, and improved physical performance in treadmill running and grip strength tests. The underlying mechanisms were associated with modulation of the AKT/mTOR pathway, inflammatory response, and myostatin/Smad/FOXO signaling[61]. Schisandrae chinensis fructus ethanolic extract increased grip strength, CSAs, and weight of the gastrocnemius muscle in mice with STZ-induced diabetes. This was achieved by reducing the activity of the p62/SQSTM1-mediated autophagy-lysosomal pathway and the CREB-KLF15-mediated UPS system[62].

Flavonoids

-

Puerarin, an isoflavone compound derived from Pueraria lobata, is a primary bioactive component in traditional Chinese medicine. Supplementation with 100 mg/kg puerarin for eight weeks improved the muscle strength, weight, and skeletal muscle CSAs in STZ-induced T1DM rats. The mitigatory effect of puerarin on skeletal muscle wasting is closely related to muscle atrophy marker gene regulation (Atrogin-1 and Murf-1), Akt/mTOR activation, and autophagic inhibition[40]. Of note, the 16-week administration of 300 mg/kg puerarin-enriched Radix Pueraria lobata extracts protected against the muscle wasting caused by obesity, including ameliorating the reduction in gastrocnemius muscle mass to body weight ratios and CSAs of gastrocnemius muscle fibers in HFD-fed mice. The mechanism responsible for these effects was considered as the modulation of expression of key players in the regulation of energy metabolism, PGC-1α and AMPK, in skeletal muscle[63].

Bavachin and corylifol A are phytochemical components derived from Psoralea corylifolia L. seed. The db/db mice were used to evaluate the beneficial effect of dietary bavachin and corylifol A supplementation on diabetes-induced muscle atrophy. The findings showed that corylifol A and bavachin significantly improved muscle function by increasing grip strength, myofiber CSA, and fiber size. The observed positive outcomes are strongly associated with augmented protein synthesis via the mitigation of inflammation, the enhancement of mitochondrial function and integrity, the activation of AMPKα–PGC-1α signaling pathway, and the decrease in oxidative stress[41].

Apigenin, an abundant natural plant flavone in parsley, celery, onions, oranges, chamomile, and maize, substantially increased the CSA distribution, skeletal muscle weight, and running distance of mice receiving an HFD, improving obesity-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. In addition, the administration of apigenin decreased the expression of atrophic genes, such as Atrogin-1 and MuRF1, while simultaneously enhancing mitochondrial functionality and biogenesis, as well as exercise ability[42].

Quercetin is found abundantly in onions, broccoli, apples, and berries. Studies showed that quercetin prevented a decline in the relative weights of the soleus, gastrocnemius, and quadriceps muscles, as well as the mean gastrocnemius muscle fiber diameters in HFD-induced obese mice. Furthermore, quercetin decreased the inflammatory cytokine levels and the MuRF1 and Atrogin-1 expression in the skeletal muscle[43]. These findings indicate that quercetin may protect against metabolic dysregulation and muscle atrophy caused by obesity.

The representative flavone, luteolin, is mostly found in fruits, vegetables, and medicinal plants like celery seeds, parsley, and peppermint. In mice with obesity-induced sarcopenia, luteolin intervention restored muscle weight, grip strength, and the average area and number of muscle fibers. Additionally, it suppressed the influx of lipids into the muscle and reduced the activity of p38 and the expression of inflammatory factors. It has been shown that luteolin effectively suppresses muscle inflammation by inhibiting the expression of MuRF, atrogin, FoxO, and myostatin[44]. This indicates that luteolin enhances muscle weight and function by limiting protein breakdown and reducing lipid buildup and inflammation in the muscle tissue. Interestingly, the dietary intervention of 250 mg/kg extracts of Chrysanthemi zawadskii var. latilobum, a perennial herb from the Asteraceae family that has a high content of luteolin, ameliorated obesity-induced triglyceride accumulation in quadriceps muscle tissue. The reduction of exercise performance (time to exhaustion, running distance, and grip strength) and muscle fiber size induced by HFD feeding were restored after Chrysanthemi zawadskii var. latilobum treatment. The molecular mechanisms were related to the decrease of inflammatory mediators levels, improvement of mitochondrial dysfunction, and regulation of muscle atrophy-related gene and protein expression[64].

Naringin is a major flavonoid in citrus fruits, such as pomelos and grapefruit. Dietary naringin supplementation significantly increased the soleus, gastrocnemius, and quadriceps muscle weight and improved the quadricep muscle fiber diameters and CSA in HFD-induced obese rats. The molecular mechanisms of these beneficial effects are associated with reduced muscle lipid accumulation and oxidative stress levels, upregulated mTOR and PGC-1α mRNA expression, and downregulated Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 atrophic factor mRNA expression in the quadriceps muscle tissues[45].

Glabridin, a prominent flavonoid derived from licorice root, exhibits diverse pharmacological properties, particularly in its ability to mitigate hyperglycemia. Licorice flavonoid oil, an ethanol extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. root, is notably rich in glabridin. Following a two-week supplementation of licorice flavonoid oil, significant enhancements were observed in skeletal muscle mass, alongside protein ubiquitination inhibition, p70 S6K, and mTOR pathway activation, and FoxO3a phosphorylation regulation in KK-Ay diabetic mice[65].

Anthocyanins, a class of water-soluble flavonoid pigments, are present in diverse plant tissues, contributing to the red, blue, and purple hues observed in these organisms. Blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) is an increasingly recognized commercial fruit globally, renowned for its abundance of anthocyanins in the berries[66]. Lonicera caerulea extract exhibited anti-sarcopenic obesity effects, as manifested by the increased muscle strength, skeletal muscle weight and CSA, as well as regulated muscle atrophy and muscle growth-related gene levels[67].

Terpenoids

-

Geranylgeraniol is a natural isoprenoid found in fruits, vegetables, and grains, including rice. Supplementation with 800 mg/kg geranylgeraniol for eight weeks prevented mitochondrial fragmentation and potentially decreased the demand for mitochondrial fusion in HFD/STZ-induced diabetic SD rats. Improved mitochondrial quality can rescue muscle CSA in diabetic rats after geranylgeraniol supplementation[46]. The investigation demonstrated that after 14 weeks of diet intervention, 400 mg/kg geranylgeraniol increased the soleus mass and CSA of the gastrocnemius muscle, as well as altered gut microbiome composition in HFD-induced muscle atrophy mice[32]. At the species level, the geranylgeraniol and green tea polyphenols diet decreased the relative abundance of Dorea longicatena, Sporobacter termitidis, and Clostridium methylpentosum, while increasing the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila and Subdoligranulum variabile. These results suggest that the addition of geranylgeraniol and green tea polyphenols to HFD helps alleviate skeletal muscle atrophy, potentially through associated changes in the gut microbiome composition.

The aromatic chemical, α-Ionone, has been identified in a range of plant species, such as plums, blackberries, and violets. The administration of 100 mg/kg α-ionone for ten weeks attenuated the muscle strength, myofiber diameter, muscle protein level, and skeletal muscle weight in mice receiving an HFD. This effect was attributed to an elevation in the cAMP concentration and the subsequent improvement of its downstream PKA-CREB signaling pathway in the gastrocnemius muscle[48].

α-Cedrene is a notable sesquiterpene component found in cedarwood oil obtained from Juniperus and Cupressus species in the Cupressaceae family. Furthermore, it serves as a naturally occurring ligand of mouse olfactory receptor 23 that plays a crucial role in protecting skeletal muscle health in hyperlipidemic conditions. α-Cedrene effectively counteracted the effects of an HFD on body weight gain, skeletal muscle weight, and grip strength[47]. This was achieved by stimulating the expression of MOR23 and improving its downstream cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling in the skeletal muscles of mice receiving chow or HFD.

Alkaloids

-

The natural alkaloid, boldine, is typically present in Peumus boldus bark and leaves. In STZ-induced diabetic rats, boldine extracted from the endemic Chilean tree prevented CSA reduction and muscle fiber permeabilization. Moreover, culturing murine myofibers for 24 h in a high glucose environment drastically increased the sarcolemma permeability and NLRP3 level, a response that was prevented by boldine treatment[49].

Supplementation with magnoflorine, a quaternary alkaloid isolated from Magnolia or Aristolochia, significantly prevented the loss of myotube diameter and skeletal muscle weight in STZ-induced T2DM rats. Several mechanisms were proposed for the alleviation of diabetes-related muscle atrophy by magnoflorine, which included decreasing ubiquitin-proteasomal E3-ligase, autophagic, and caspase-associated gene expression, calpain activity, inflammation, and oxidative stress in the muscles of T2DM rats while activating the Akt signaling pathway[50].

Saponin

-

Tangshenoside I was identified as the primary compound in Codonopsis lanceolata. After 200 mg/kg Codonopsis lanceolata administration for six weeks in HFD-fed mice, the grip strength, skeletal muscle tissue weight (soleus, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius), and distribution graph of the muscle fiber CSA were all remarkably augmented, skeletal muscle lipid aggregation was considerably reduced. These outcomes stemmed from the restoration of both the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle[68].

Ginsenosides are a kind of important bioactive component in ginseng (Panax ginseng). It is reported that black ginseng exhibits higher bioactivity compared to white ginseng, primarily attributed to its abundant presence of unique ginsenosides Rg5, Rk1, and Rh4, which are absent in white ginseng. Supplementation with 900 mg/kg black ginseng extract for five weeks augmented muscle fiber size and reduced muscle fibrosis by activating the mTOR pathway and enhancing skeletal muscle protein synthesis in diabetic mice[69].

It is widely believed that ginseng berry extract exhibits elevated levels of ginsenosides and unique ginsenoside profiles compared to ginseng extract. The nine-week oral administration of Panax ginseng berry extract at a dosage of 200 mg/kg substantially improved the myofiber CSA, skeletal muscle weight, and grip strength of mice with sarcopenic obesity caused by HFD. The ectopic lipid deposition caused by superfluous HFD feeding inhibits the PI3K/Akt pathway, which is responsible for regulating protein synthesis and breakdown. The administration of Panax ginseng berry extract prompted the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and elevated the phosphorylation levels of FoxO3a, 4E-BP1, S6K1, and mTOR[70]. Consequently, there was a reduction in the expression of muscle atrophy-related protein, potentially accounting for the observed amelioration of skeletal muscle wasting.

Compound K, an active metabolite derived from ginsenoside Rb1, has demonstrated therapeutic potential in a spectrum of diseases. Recent research indicated that compound K potentially mitigated the in vivo and in vitro apoptosis of skeletal muscle in hyperlipidemic conditions, offering a possible solution to address the muscle atrophy associated with obesity. Compound K may stimulate myogenesis to prevent a myotube diameter decline. Consistent with these changes, the in vivo results demonstrated that compound K addition for eight weeks reversed myofiber diameter reduction in HFD-fed mice, while higher levels of myostatin, MuRF1, and atrogin-1 expression were evident in the skeletal muscles[51].

Quinone

-

Shikonin, a prominent naphthalene compound, represents the primary bioactive constituent derived from the roots of Lithospermum erythrorhizon, commonly referred to as 'Zicao' in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Dietary supplementation with 0.25% (w/w) Lithospermum erythrorhizon extracts over ten weeks exhibited therapeutic effects against obesity-induced reductions in skeletal muscle mass, grip strength, time to exhaustion, and the average CSA of the gastrocnemius muscle. The observed improvement of skeletal muscle wasting in mice fed an HFD with Lithospermum erythrorhizon extracts treatment was associated with enhanced activation of protein synthesis pathways, reduction of atrophy markers, and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis[71].

Other plant extracts

-

Except for the natural products mentioned above, other plant extracts can also ameliorate skeletal muscle atrophy in glucolipid metabolic disorders. The animal and cell studies of these bioactive plant extracts and their action mechanisms have been comprehensively reviewed in Table 2.

Propolis, commonly referred to as 'bee glue', is a resinous material gathered by bees from a variety of botanical sources. Brazilian green propolis reportedly improves the sarcopenic obesity caused by overeating in classic diabetic mice model-db/db mice, as manifested by increased skeletal muscle mass and grip strength and decreased gene expression associated with muscle atrophy and inflammation. Brazilian green propolis supplementation improved the gut dysbiosis of db/db mice, and the fecal microbiota transplantation indicated that gut microbiota is crucial for the anti-muscle atrophy effects of Brazilian green propolis[74].

Artemisia dracunculus L., a member of the Asteraceae family, holds a significant history in traditional Asian medicinal practices. Dietary supplementation with 1% (w/w) Artemisia dracunculus L. ethanolic extract changes the gene expression of enzymes associated with the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which plays pivotal roles in regulating skeletal muscle mass in KK-Ay obese diabetic mice fed a low-fat diet[73].

Juzentaihoto represents a hot-water-extracted formulation composed of ten raw medicinal ingredients, which are subsequently dried and pulverized. The 4% (w/w) juzentaihoto administration for eight weeks in KK-Ay mice suppressed skeletal muscle atrophy and regulated muscle atrophy-related mRNA levels by improving insulin resistance, inhibiting inflammation, and reducing oxidative stress[77]. Furthermore, significant enhancements in antioxidant activity, skeletal muscle weight, and motor function were found after prophylactic juzentaihoto hot water extract administration to ICR mice exhibiting diabetic oxidative stress due to STZ injection[76].

Multiple studies have suggested that a variety of compounds induce an increase in Sirtuin1 expression, leading to an inhibitory impact on muscle atrophy. Saikokeishikankyoto extract was identified as the Sirtuin1 promoter in vitro by luciferase assay. Further animal experiments indicated that Saikokeishikankyoto hot water extract intervention increased the gastrocnemius muscle fiber CSA and skeletal muscle mass, while enhancing the rotarod tolerance time in KK-Ay mice by mitigating inflammation and downregulating ubiquitin gene expression in muscle tissue[53].

The traditional Chinese herbal formula, Liuwei dihuang, comprises six distinct medicinal herbs. Treatment with Liuwei dihuang water extract mitigated methylglyoxal-induced atrophy of C2C12 myotubes through mechanisms involving enhanced mitochondrial function, activation of IGF-1/Akt/mTOR signaling, reduction of oxidative stress levels, and inhibition of protein ubiquitination. The anti-skeletal muscle atrophy effect of Liuwei dihuang water extract was further confirmed in STZ-treated mice, as evidenced by the improvements in muscle mass and grip strength[79].

Lespedeza bicolor contains various natural compounds, such as flavonoids like quercetin, genistein, and naringenin, which possess potential antidiabetic and antioxidative properties both in vivo and in vitro. Supplementation with Lespedeza bicolor extract normalized skeletal muscle weight, expanded the CSA, and downregulated the levels of protein related to skeletal muscle degradation in mice with HFD/STZ-induced T2DM[78].

Morinda officinalis, a renowned botanical resource with medicinal and culinary significance, finds extensive cultivation across the Lingnan region in southern China. The administration of Morinda officinalis root extract at a dosage of 200 mg/kg in HFD/STZ-induced diabetic mice markedly enhanced both the myogenic protein expression and myofiber size of gastrocnemius tissues. Analogous effects on myogenic protein levels were observed in C2C12 myoblasts upon treatment with 2 mg/mL of Morinda officinalis root extract[80].

The herbal composition of the herb pair known as Zhimu-Huangbai is widely recognized and comprises Cortex Phellodendri and Rhizoma Anemarrhena. The oral administration of Zhimu-Huangbai for six weeks notably enhanced the CSA, muscle strength, and skeletal muscle mass[81]. These improvements were attributed to Akt/mTOR/FoxO3 signaling pathway activation in mice with HFD/STZ-induced diabetes.

Aged black elephant garlic and aged black garlic could mitigate HFD-induced obesity, increase the relative gastrocnemius muscle tissue weight, and regulate muscle atrophy-related gene and protein expression. In addition, L-proline and S-Methyl-L-cysteine represent candidate bioactive compounds of aged black elephant garlic and aged black garlic, respectively, and they have been shown to promote the differentiation of C2C12 cells and the expression of myogenesis-related proteins in vitro[72].

Gintonin, a constituent of Panax ginseng, is a non-saponins component and comprises a class of glycolipoproteins rich in lysophosphatidic acid, carbohydrates, and hydrophobic amino acids. Mice receiving an HFD and treated with gintonin-rich fractions displayed elevated muscle mass and strength, reduced expression of skeletal muscle atrophic genes, and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle[75].

These results indicate that the administration of various plant extracts beneficially affects skeletal health in glucolipid metabolic disorders. However, further investigation is necessary to identify the primary phytochemicals responsible for these effects and delineate the precise action mechanisms. This finding holds considerable significance for the advancement of pharmaceutical agents and dietary supplements through research and development. Since the efficacy of plant extracts against skeletal muscle atrophy has been examined in relatively short-term interventions, the impact of long-term intake remains unclear. Safety concerns should be considered when determining the precise dosages of these phytochemicals, particularly those derived from herbal sources. Additionally, the absorption, metabolism, bioactivity, and bioavailability of phytochemicals should be addressed in future studies.

While Tables 1 and 2 predominantly present data from animal models, it is important to note that research in this area is currently focused on preclinical studies, and human clinical trials are still scarce. The gap in human data reflects the complexity of translating findings from animal models to human populations. We hope that future clinical studies will provide more insight into the potential benefits of phytochemicals in managing metabolic dysfunction in humans.

-

Research involving animal cell lines and models has shown the excellent bioactivities of phytochemicals and plant extracts for controlling skeletal muscle atrophy under glucolipid metabolic disorders. Importantly, phytochemicals have been applied for clinical skeletal muscle wasting treatment, especially as a result of aging or cancer[82]. Recent reports indicated that the natural alkaloid, trigonelline, present in plants and animals, exhibits reduced levels in the serum of individuals with sarcopenia and is associated with skeletal muscle mitochondria and NAD+ metabolism, revealing trigonelline as a potential novel metabolite related to muscle function[83]. Some efforts have been made to evaluate the impact of phytochemicals and plant extracts on compromised skeletal muscle functionality in diabetic or obese patients.

The potential effects of resveratrol intervention in mitigating skeletal muscle atrophy induced by glucolipid metabolic disorders, as discussed in the preceding sections of this review, have been corroborated in numerous preclinical studies. In clinical trials, administration of resveratrol for approximately one month in obese individuals enhances muscle mitochondrial respiration and citrate synthase activity, mimicking the physiological effects akin to calorie restriction[84].

Genistein, an isoflavone that was first isolated from Genista tinctoria L., is widely distributed within the Fabaceae family. In obese individuals, the intake of 50 mg/day of genistein for two months led to diminished insulin resistance and metabolic endotoxemia in skeletal muscle. Additionally, it increased the gene expression involved in regulating fatty acid oxidation and AMPK signaling pathways in skeletal muscle[85].

Carotenoids, renowned bioactive compounds derived from plants, demonstrate significant antioxidant properties and the ability to retard senescence. A randomized controlled intervention study elucidated that a carotene-rich diet helps preserve skeletal muscle function and mitigates the onset of sarcopenia in elderly obese individuals[86].

T2DM and heart failure are conditions linked to impairments in skeletal muscle mitochondrial structure and function. Intriguingly, individuals adhering to a diet abundant in epicatechin exhibit enhanced skeletal muscle strength. For example, the dietary supplementation of epicatechin-rich cocoa in individuals with coronary failure and T2DM could reduce skeletal muscle oxidative stress[87]. It has been found that epicatechin-rich cocoa treatment improved the protein complex levels associated with dystrophin, as well as the indicators of skeletal muscle growth/differentiation in T2DM and heart failure patients[88]. Furthermore, individuals diagnosed with both T2DM and heart failure, who underwent a three-month supplementation regimen of 100 mg/day of epicatechin-rich cocoa, demonstrated augmented mitochondrial biogenesis and decreased mitochondrial damage within skeletal muscle[89].

Despite the ongoing clinical trials in this area, many studies are still in the early phases or lack conclusive results. These trials primarily focus on the effects of phytochemicals such as resveratrol, genistein, carotenoids, and epicatechin on muscle function and atrophy in conditions like obesity, T2DM. While the results of these trials are promising, further research is essential to validate these findings and fully explore the therapeutic potential of phytochemicals in treating muscle atrophy associated with glucolipid metabolic disorders.

-

The patents and the related data were obtained from the website of Google Patents and were searched using the term 'muscle' and the vernacular names of phytochemicals. As shown in Table 3, in the last couple of decades, a large number of patents have been granted for anti-muscle atrophy or skeletal muscle function-promoting phytochemicals or the combination of these phytochemicals with other components, including curcumin, urolithin A, (-)-epicatechin, epigallocatechin, quercetin, naringin, and tangshenoside I. The abundant filing of patents suggests the promising commercial application of these phytochemicals as a dietary intervention strategy for skeletal muscle atrophy.

Table 3. An excerpt of patents of phytochemicals in muscle health.

Phytochemicals Patent number Date of grant Patent title Key claims Ref. Phenols Curcumin CA3221915A1 2022.12.22 Compositions comprising curcuminoids for use in the treatment of muscle soreness A composition comprising curcuminoids for improving functional performance and/or relieving muscle soreness during and/or after exercise. [90] EP2859896B1 2018.01.31 Pharmaceutical compositions for the treatment of muscular disorders A pharmaceutical or nutritional composition comprising baicalin, curcumin, green tea catechins, vitamin E, vitamin C, coenzyme Q10, Acetyl-L-carnitine, docosahexaenoic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid for treating and preventing muscular disorders, with specific ingredient amounts specified for each component. [91] Tannin Urolithin A EP2866804B1 2023.09.13 Enhancing autophagy or increasing longevity by administration of urolithins or precursors thereof The use of urolithin A, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, for treating or preventing aging-related health conditions such as osteoarthritis, muscular atrophy, cardiac deterioration, or endothelial cell dysfunction. [92] EP3278800B1 2019.04.10 Compositions and methods for improving mitochondrial function and treating muscle-related pathological conditions Use of urolithin for the treatment or prevention of muscle diseases, myopathies, muscular dystrophies, musculoskeletal disorders, or neuromuscular diseases, including conditions such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy and muscle atrophy, and for improving or maintaining muscle performance, reducing fatigue, and enhancing sports performance in healthy subjects. [93] KR101955001B1 2019.03.07 Compositions and methods for improving mitochondrial function and treating neurogenerative diseases and cognitive disorders A pharmaceutical composition comprising urolithin for treating muscle skeletal disorders such as cachexia or muscle atrophy, wherein the composition increases, maintains, or improves muscle mass and function, and a functional food comprising urolithin for increasing or maintaining muscle performance or alleviating muscle skeletal disorders. [93] (−)- Epicatechin WO2014099904A1 2014.06.26 Methods for enhancing motor function, enhancing functional status and mitigating muscle weakness in a subject A method for enhancing motor function in a subject by providing a nutritional composition containing protein and applying a vibrational stimulus, resulting in enhanced motor function. [94] WO2014021413A1 2014.02.06 Polyacetal resin composition and slide member produced by molding it A muscle fatigue inhibitor comprising catechins as active ingredients, formulated as food/beverage products, and containing specific components to enhance muscle strength and exercise effects. [95] Epigallocatechin US9980997B1 2018.05.29 High flavanol cocoa powder composition for improving athletic performance A composition and method for improving overall athletic performance in mammals by administering a preparation containing cocoa powder, protein, carbohydrate, and fat, wherein the cocoa powder contains at least 7.5% of its weight in flavonoids. [96] Flavonoids Quercetin JP6942165B2 2021.09.29 Muscle atrophy inhibitor containing quercetin glycoside A muscle atrophy inhibitor containing quercetin glycoside as an active ingredient, for suppressing muscle atrophy by inhibiting the expression of Mstn, excluding disuse muscular atrophy. [97] Naringin AU2017204579B2 2018.09.20 Methods of inhibiting muscle atrophy A method of lowering blood glucose in an animal by administering at least 25 mg of ursolic acid and at least 10 mg of naringenin, or their derivatives, solvates, or pharmaceutically acceptable salts. [98] Saponin Tangshenoside I CN104069339A 2014.10.01 Traditional Chinese medicine composition for treating myasthenia gravis and preparation method thereof A Chinese medicine composition for treating myasthenia gravis, comprising specific proportions of various Chinese medicinal herbs, with or without a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier, and prepared in oral dosage form, such as decoction or oral liquid. [99] -

This review highlights the promising potential of phytochemicals, including polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids, in mitigating skeletal muscle atrophy caused by glucolipid metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity. Phytochemicals have demonstrated beneficial effects on muscle quality and function through mechanisms such as activation of the insulin-like growth factor 1/protein kinase B signaling pathway, inhibition of protein ubiquitination, enhancement of mitochondrial function, reduction of oxidative stress, and modulation of gut microbiota. Despite these promising findings from animal studies, clinical evidence remains limited, and human trials are urgently needed to translate these preclinical results into effective treatments for muscle atrophy.

While most phytochemicals are derived from natural food sources, their safety, bioavailability, and potential toxicity must be carefully considered. Some phytochemicals, like those from garlic and eggplant, may cause adverse effects at higher doses or with prolonged use, underlining the importance of pharmacovigilance and appropriate clinical monitoring. Moreover, despite the low bioavailability of many phytochemicals, innovative delivery systems, such as liposomes and nanoparticles, have shown promise in improving their solubility, stability, and therapeutic efficacy.

The bioactivity of phytochemicals is intricately linked to their chemical structure, which influences their biological activity. However, variations in the structure-activity relationship and differences in extraction methods complicate their consistent application. Therefore, further research is necessary to establish systematic, high-efficiency preparation methods for deconstruction to enhance the possibility of clinic translation. Additionally, while some phytochemicals show varying effects depending on the disease model, these discrepancies may provide insights into different mechanisms of muscle atrophy and highlight the need for more rigorous and standardized experimental designs.

Given the multifactorial nature of muscle atrophy, further exploration of phytochemicals' potential in combination with existing therapies is warranted. Preliminary studies suggest that phytochemicals may work synergistically with approved drugs, offering enhanced therapeutic effects, as seen in the combination of Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharide and metformin. Furthermore, the emerging role of gut microbiota in modulating muscle atrophy opens new avenues for research, as phytochemicals may influence microbial communities to alleviate muscle wasting.

Although significant advances have been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying muscle atrophy, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, much remains to be understood. Novel molecular targets, such as growth differentiation factor 15 and ectodysplasin A2, offer hope for future therapies. Given that muscle atrophy is a complex, multifactorial process, combination therapies targeting multiple pathways may offer the most effective approach.

The findings presented in this review not only deepen understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying muscle atrophy but also identify promising phytochemical candidates for new therapeutic strategies. This review serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and clinicians aiming to develop effective dietary-based interventions for managing muscle atrophy, providing valuable insights into the potential of phytochemicals in treating metabolic diseases. Integrating these findings into clinical practice could significantly enhance the prevention and treatment of skeletal muscle atrophy, addressing a major challenge in managing glucolipid metabolic disorders.

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Project of Xizang Autonomous Region (Grant no. XZ202401ZY0092) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant no. 7222249).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Li M, Qin Y, Geng R, Fang J, Kang SG, Huang K, Tong T; investigation: Li M, Qin Y; methodology: Li M, Qin Y, Kang SG, Huang K, Tong T; visualization, writing - original draft: Li M, Qin Y; writing - review & editing: Li M, Qin Y, Tong T; funding acquisition: Huang K, Tong T; project administration, supervision: Tong T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Mengjie Li, Yige Qin

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li M, Qin Y, Geng R, Fang J, Kang SG, et al. 2025. Effects and mechanisms of phytochemicals on skeletal muscle atrophy in glucolipid metabolic disorders: current evidence and future perspectives. Food Innovation and Advances 4(1): 83−98 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0009

Effects and mechanisms of phytochemicals on skeletal muscle atrophy in glucolipid metabolic disorders: current evidence and future perspectives

- Received: 28 October 2024

- Revised: 05 December 2024

- Accepted: 13 January 2025

- Published online: 04 March 2025

Abstract: Skeletal muscle atrophy resulting from glucolipid metabolic disorders poses a serious challenge to human health with the rapidly increasing prevalence of diabetes and obesity. Clinical trials investigating treatment interventions against skeletal muscle atrophy yielded limited success. This article addressed novel phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and plant extracts, that modulated muscle atrophy and suggested avenues for future treatment. Several studies demonstrated an inverse relationship between dietary phytochemical supplementation and the onset of skeletal muscle atrophy caused by glucolipid metabolic disorders, as evidenced by improved muscle quality and function. Insulin-like growth factor 1/protein kinase B signaling pathway activation, protein ubiquitination inhibition, enhancement of mitochondrial function and inflammatory response, reduction of oxidative stress, and regulation of gut microbiota represent the mechanisms underlying the anti-skeletal muscle atrophy effect of phytochemicals. The manuscript also contains the clinical trials and filed patents regarding the beneficial effects of phytochemicals on skeletal muscle health. This review provided fresh perspectives on potentially effective therapeutic or preventive measures (dietary phytochemical intervention) for clinically managing skeletal muscle atrophy associated with diabetes or obesity.

-

Key words:

- Phytochemicals /

- Skeletal muscle atrophy /

- Diabetes /

- Obesity /

- Mechanisms