-

Herbicides are agrochemicals used worldwide for crop protection against weeds, to increase the yields of cultivated fields[1]. Due to their biomagnification and persistence, extensive and frequent use leads to herbicide residues in the soil environment. The migration and diffusion of herbicides may pollute entire ecosystems directly or indirectly through the media of soil, water, and air, causing serious harm to living organisms[2]. Studies showed that the average residue of atrazine in cropland soil of northeast China was 11 μg·kg−1[3,4]. The residues of imidazolinone herbicides like imazapic and imazapyr in the paddy fields of Malaysia were 0.03−0.58 μg·mL−1 and 0.03−1.96 μg·mL−1[5]. Fomesafen could be detected in cropland soil, and the residues were about 3.34−67.84 μg·kg−1 in soybean fields of Heilongjiang Province, China[6], and 11.20−55.40 μg·kg−1 in cropland soil of Jiangsu Province, China[7]. Herbicides not only cause residue in soil but also affect the water environment. Ten triazine herbicide compounds including atrazine and prometryn were detected from 64 stations in the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea, with concentrations ranging from 0.27−6.61 nmol·L−1[8]. Different concentrations of ametryn, prometon, prometryn, tebuconazole, and atrazine were detected in the aquatic environments of Shandong Province, China, and ranged from 0.11−8.5 μg·L−1[9].

The removal of the contaminated residues of herbicides has become an important aspect of environmental protection. Phytoremediation is a cost-effective and environmentally friendly technique that uses plants to remediate contaminated soil and water[10]. Phytoremediation technology has been widely used in the remediation of herbicide contamination residues due to its advantages of environmental protection, economic efficiency, and low implementation difficulty[11,12].

Plants' abilities to decontaminate polluted environments rely on their capability to overcome the presence of contaminants. The stronger the tolerance of plants to pollutant stress, the less adverse impact of accumulation pollutants in plant tissues. Therefore, screening out plants that are tolerant to pollutants is important. Turfgrass has strong vitality, reproduction, and regeneration capabilities, and excellent stress resistance[13]. In addition, turfgrass does not enter the food chain and threaten human health, and it can be mowed multiple times, which can better deal with environmental pollution than other plants such as crops[14].

L. multiflorum has an extensive root system and a large biomass, with the ability to withstand multiple mowing, making it a good pollutant remediation species[15,16]. L. multiflorum can remove up to 40% of the triazine herbicide terbuthylazine (TBA) in aqueous solutions[15] and can remove 91.5% to 99.5% of sulfonamides (SAs) in piggery wastewater, including sulfadiazine, sulfamethazine, and sulfamethoxazole[16]. L. multiflorum has also been found to effectively absorb the dinitroaniline herbicide trifluralin, which binds and metabolizes in plants[17]. Existing studies focus on degradation abilities, metabolic pathways, and remediation mechanisms of L. multiflorum[18]. However, the evaluation of the tolerance ability of L. multiflorum to herbicides needs further exploration.

In this study, 13 herbicides with long residual time and serious environmental toxicity were selected to apply to L. multiflorum. The tolerance of L. multiflorum to different herbicides was analyzed, and the types of herbicides with relatively strong and weak tolerance of L. multiflorum were obtained. The results not only provide data support and a theoretical basis for using L. multiflorum to remede herbicide residues, but also lay clues for research on the remediation effect of turfgrass on herbicides.

-

The L. multiflorum material used in this experiment was sourced from The Forage Seed Laboratory, China Agricultural University (Beijing, China). The names, purity, and sources of herbicides used in this study are shown in Table 1. The action mechanisms, application places, and target plant categories of different herbicides are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1. Purity and source of tested herbicides.

Herbicide name Standard purity Source Alachlor 98.7% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd Butachlor 98.4% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd Metolachlor 99.3% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd Imazamox 98.3% Shenyang Shenhua Institute Testing Technology Co., Ltd Atrazine 97.1% Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai) Trading Co., Ltd. Prometryn 99.4% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd Fomesafen 99.0% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd Quinclorac 99.0% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd Flumetsulam 98.0% Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai) Trading Co., Ltd. Clomazone 98.4% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd Isoxaflutole 98.6% Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai) Trading Co., Ltd. Pendimethalin 98.2% Shanghai Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 99.1% Shenyang Shenhua Institute Testing Technology Co., Ltd Seed pretreatment and germination experiment

-

The seeds of L. multiflorum were soaked in 10% sodium hypochlorite solution (NaClO) for 15 min. After soaking, the seeds were rinsed with distilled water until the cleaning solution is no longer turbid, and then air dried naturally.

Top of Paper Method (TPM) was chosen for the germination test. The agents were added to the petri dish and the filter paper was wet. The concentration settings were as follows:

Single-agent exposure treatment: 13 herbicides were added separately with concentrations of 0 (CK), 10, 30, 50, 100, 200, 600, 1,200, and 2,400 μg·L−1.

Combined dose exposure treatment: Added 13 herbicides at 1, 5, and 10 μg·L−1 respectively for mixing, for a total of three combined dose concentrations.

The sterilized L. multiflorum seeds were placed evenly in a petri dish with a diameter of 9 cm, 50 seeds in each dish. The amount of herbicide added to the petri dish was 8 mL, and the petri dishes were sealed with sealing film to reduce the evaporation of the agent. Each treatment was four replicates. The petri dishes were placed in an intelligent low-temperature light incubator (DWGZ-500E2, Hefei Youke, Hefei, Anhui Province, China) controlled at 27 mmol·m–2·s–1 photosynthetically active radiation at temperatures of 25/15°C (day/night) with 70%–80% relative humidity in an 8-h photoperiod for germination.

The radicle breakthrough seed coat of 1 mm was used as the seed germination standard[19]. Seed germination parameters were recorded every day until the 7th day.

$ \begin{split} \rm{G}\mathrm{ermination\; rate}\; (\text{%})=\dfrac{\mathrm{\rm{No.}\ of\; germinated\; seeds\; within\; 7\; d}}{\mathrm{Total\; no.\; of\; tested\; seeds\; }}\times 100\text{%}\end{split} $ $ \begin{split} & \rm{Germination\; potential\; (\text{%})}= \\ &\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\;\;\dfrac{\mathrm{No.\; of\; germinated\; seeds\; within\; 3\; d}}{\mathrm{\rm{T}otal\; no.\; of\; tested\; seeds}}\times 100\text{%} \end{split} $ $\rm{Germination\;index}=\textstyle\sum G_{ \mathrm{t}} \mathrm{/D}_{ \mathrm{t}} $ $ \rm{Average\;germination\;speed\;(d)}=\textstyle\sum (G_{ \mathrm{t}} \times {D}_{ \mathrm{t}} )/\textstyle\sum G_{ \mathrm{t}} $ where, Gt is the number of seeds germinated on the day corresponding to Dt; Dt is the number of germination days, d.

Hydroponic exposure treatment

-

The L. multiflorum seeds were sown in a square plastic flowerpot with a bottom area of 10 cm × 10 cm. The culture medium was vermiculite. 1/4 Hoagland nutrient solution was used for cultivation and watered once every 3 d, and the concentration of the nutrient solution was gradually increased until it reached 100%. After the seedlings grew steadily and the tillers were uniform after 30−40 d, the roots were rinsed with water until there was no vermiculite impurities present. The seedlings with consistent growth were selected and transplanted into a hydroponic container. Seedlings were wrapped at the base part of the tillers using a foam cube, inserted in a polystyrene sheet which was placed over the Hoagland's nutrient solution in a container (12.5 cm × 8.5 cm × 12 cm). There were 12 seedlings in each container and three containers each treatment. A total of 129 containers of seedlings were used in this experiment. The hydroponic container after transplanting was transferred to an intelligent artificial climate box (RXZ-430c, Ningbo Jiangnan, Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China). The incubator was set at 750 μmol∙m−2∙s−1 at temperatures of 25/15°C (day/night) and cultured for 7−10 d for adaptation.

The plants to be treated were uniformly cut to a height of 10 cm, and herbicides were added to the hydroponic container according to different concentrations.

Single-agent exposure treatment: 13 herbicides were added separately, and three single-agent concentrations of 0 (CK), 300, 600, and 1,200 μg·L−1 were set.

Combined dose exposure treatment: 13 herbicides were added with 10, 50, and 100 μg·L−1 respectively for mixing, for a total of three combined dose concentrations.

Each treatment was repeated three times. Nutrient solution was added to the hydroponic container every 1 d to the same content as that at day 0. The exposure experiment was treated for 5 d.

Physiological measurements

-

Twenty plants were randomly selected from each treatment, and the length from the upper part of the crown to the tip of the leaf of L. multiflorum was measured with a ruler, and the data were recorded as plant height, and the average values were calculated[20].

The aluminum box was placed in the oven at 100-105 °C for 2 h to a constant weight, then weighed (m0). Ten plants were randomly selected from each treatment, washed with deionized water, cut into pieces, and weighed in an aluminum box (m1). The aluminum box containing the plant was placed in the oven at 50−60 °C for 3−4 h (ventilation), 100−105 °C oven for 3−4 h (no ventilation), repeated three times, and weighed after cooling (m2). Then the leaf dry matter content (LDMC) was calculated according to the equation:

$ \rm{L}DMC=\dfrac{m_2-m_0}{m_1-m_0}\times100\text{%} $ Leaf chlorophyll was extracted by soaking fresh leaf tissues in 9 mL 95% ethanol. After full extraction, the absorbance of the leaf extract was measured at 665, 649, and 470 nm using a UH5300 UV spectrophotometer (HITACHI, Japan). The content of chlorophyll was calculated using the following equations[21]:

$\rm {C}_{ {a}}\;{(mg\cdot L}^{ {-1}} )=13.95A_{ {665}}- {6.88A}_{ {649}} $ $\rm {Chlorophyll\;a\;content\;(mg\cdot g}^{ {-1}} )=C_{ {a}} \times{ V/W} $ $\rm {C}_{ {b}} \;{(mg\cdot L}^{ {-1}} )=24.96A_{ {649}}- {7.32A}_{ {665}} $ $ \rm{Chlorophyll\;b\;content\;(mg\cdot g}^{{-1}} )=C_{ \mathrm{b}} \times {V/W} $ $\rm {C}_{ {chlorophyll}}\; {(mg \cdot L}^{ {-1}} )=C_{ {a}} +{C}_{ {b}} ={6.63A}_{ {665}}+ {18.08A}_{ {649}} $ $\rm {Chlorophyll\;content\;(mg\cdot g}^{ {-1}} )=C_{ {chlorophyll}} \times{V/W} $ $\rm {C}_{ {carotenoid}}\; {(mg\cdot L}^{ {-1}} )=(1,000A_{ {470}} -{2.05C}_{ {a}}- {114.8C}_{ {b}} )/245 $ $ \rm{Carotenoid\; content\; (mg\cdot g}^{-1})=C_{carotenoid}\times V/W $ where, Ca: chlorophyll a concentration; Cb: chlorophyll b concentration; Cchlorophyll: chlorophyll concentration; Ccarotenoid: carotenoid concentration; V: extraction liquid volume (L); W: weighed sample mass (g).

The minimum fluorescence intensity (Fo), the maximum fluorescence intensity (Fm), the potential photochemical activity (Fv/Fo) and the actual photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) of PS II were determined to estimate leaf photochemical efficiency using a OS30p + handheld chlorophyll fluorometer (OPTI-SCIENCES, USA). Leaf clips were used to adapt leaves in darkness for 30 min prior to the measurement with the fluorescence meter.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured by the nitroblue tetrazolium method (NBT)[21]. The amount of enzyme that inhibited 50% of the NBT photoreduction within a unit time was taken as 1 enzyme activity unit (U). Peroxidase (POD) activity was measured using the guaiacol method[21]. Taking a change of A470 by 0.01 per minute as 1 enzyme activity unit (U). Catalase (CAT) activity was measured by ultraviolet spectrophotometry[21]. The absorbance change of 0.001 per minute per gram of fresh weight (FW) sample was taken as one CAT activity unit (U). Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was measured using the method of Chen[22]: 0.5 g of the material was added to the pre-cooled extract (50 mmol·L−1 K2HPO4-KH2PO4 buffer, pH 7.0 containing 2 mmol·L−1 AsA and 0.1 mmol·L−1 EDTA-Na2) at a ratio of 1:5. After grinding, the extract was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was the crude enzyme extract. PBK (pH 7.0) 1.8 mL, AsA 100 μL, extract 100 μL, and H2O2 1 mL were added to form a reaction system. The change in OD value within 90 s was measured at 290 nm immediately, and the enzyme activity was calculated.

Statistical analysis

-

SPSS 27 (IBM, USA) and Excel 2019 (Microsoft, USA) were used for statistical analyses. ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range tests were used to analyze significant differences at a probability level of 0.05.

-

The seed germination index can reflect the germination ability and germination rate comprehensively. Except for the most treatment concentrations of butachlor, quinclorac, and flumetsulam, which had no significant effect on the germination index of L. multiflorum seeds, many single-agent treatments of herbicides showed a promoting effect at low concentrations (10, 30, 50 μg·L−1) and medium concentrations (100, 200 μg·L−1), and an inhibitory effect at high concentrations (600, 1,200, and 2,400 μg·L−1) as shown in Table 2. The highest germination index reached 65.57 (10 μg·L−1, 2,4-D), which was 20.24% higher than the control. The lowest was only 9.08 (2,400 μg·L−1, alachlor), which was 83.35% lower than the control. Overall, the germination index of L. multiflorum seeds was more sensitive to alachlor and metolachlor, but better tolerance to quinclorac. The mixed agent treatment of three concentrations all had a positive effect on the seed germination index compared to the control with average seed germination index of 65.9, 67.2, and 60.2 at the mixed agent levels of 1, 5, and 10 μg·L−1, separately.

Table 2. Effects of different herbicides on germination index of L. multiflorum.

Herbicide Concentration (μg·L−1) 0 10 30 50 100 200 600 1,200 2,400 Alachlor 54.53 ± 0.96a 60.03 ± 1.19aB 60.82 ± 2.09aB 58.27 ± 2.03aBC 57.66 ± 4.22aABC 57.36 ± 4.42aAB 30.07 ± 9.88bD 12.51 ± 4.52cE 9.08 ± 1.21cE Butachlor 54.53 ± 0.96b 58.91 ± 1.13aCD 54.26 ± 2.96bCD 53.51 ± 1.73bC 56.04 ± 5.10abC 51.17 ± 2.75bcB 58.53 ± 3.73abB 52.05 ± 4.17bAB 43.03 ± 4.31cBCD Metolachlor 54.53 ± 0.96ab 57.28 ± 1.85aD 58.85 ± 1.35aC 58.23 ± 1.27aBC 55.72 ± 3.87aABC 51.37 ± 1.04bB 51.30 ± 4.07bBC 27.25 ± 2.14cD 17.72 ± 4.93dE Imazamox 54.53 ± 0.96ab 56.87 ± 2.11abD 56.86 ± 2.26abCD 58.88 ± 2.87aAB 57.76 ± 3.48abABC 50.40 ± 0.94bcB 55.66 ± 5.23abBC 53.49 ± 10.60abABC 43.66 ± 7.11cBCD Atrazine 54.53 ± 0.96cd 60.90 ± 2.49abB 64.65 ± 0.80aA 58.11 ± 1.73bcBC 57.41 ± 0.69bcABC 56.68 ± 1.69bcAB 52.08 ± 5.00dBC 51.80 ± 4.85dAB 41.46 ± 4.00eCD Prometryn 54.53 ± 0.96cd 64.11 ± 2.33aAB 63.18 ± 2.11aAB 61.09 ± 2.27abAB 60.30 ± 4.22abAB 59.86 ± 3.06abA 56.65 ± 3.80bcB 50.40 ± 2.13dB 41.95 ± 5.57eBCD Fomesafen 54.53 ± 0.96c 63.12 ± 1.66aABC 58.45 ± 2.13bcCD 62.72 ± 2.27aAB 60.03 ± 2.37abABC 55.64 ± 1.43cAB 49.12 ± 3.83dC 45.94 ± 3.23dC 39.84 ± 4.47eCD Quinclorac 54.53 ± 0.96b 57.92 ± 0.72bD 58.27 ± 1.89bCD 57.85 ± 5.26bBC 55.70 ± 2.50bABC 56.73 ± 1.67bAB 62.57 ± 3.65aA 57.96 ± 2.78bA 57.24 ± 3.66bA Flumetsulam 54.53 ± 0.96b 59.05 ± 3.03bB 58.97 ± 1.51bC 63.90 ± 1.23aA 58.88 ± 4.21bABC 58.36 ± 3.48bAB 56.46 ± 3.89bB 56.20 ± 2.47bA 48.13 ± 4.20cB Clomazone 54.53 ± 0.96b 59.06 ± 8.76abAB 63.22 ± 2.07aAB 56.57 ± 4.36abBC 61.05 ± 3.93aA 53.75 ± 3.96bB 47.38 ± 1.39cC 43.38 ± 2.90cdC 36.97 ± 3.15dCD Isoxaflutole 54.53 ± 0.96b 56.89 ± 1.30abD 55.82 ± 0.86bD 60.35 ± 2.51aB 60.76 ± 6.40aABC 53.24 ± 1.60bcB 49.42 ± 1.78cC 43.44 ± 1.52dC 36.15 ± 4.15eD Pendimethalin 54.53 ± 0.96ab 58.40 ± 3.44aCD 56.21 ± 1.83abD 58.02 ± 1.32aBC 56.03 ± 2.60abABC 54.76 ± 2.10abAB 51.55 ± 5.90bcBC 48.60 ± 7.90cABC 42.53 ± 3.09dBC 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 54.53 ± 0.96e 65.57 ± 1.97aA 58.74 ± 0.67cdCD 61.89 ± 3.12bAB 60.01 ± 2.60bcABC 56.61 ± 1.71deAB 49.06 ± 2.55fC 43.92 ± 1.89gC 44.07 ± 1.29gB Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration. Germination ability refers to the percentage of normally germinated seeds in the total number of tested seeds in the initial stage of the germination test, which can measure the level of seed vigor. The single-agent herbicide treatments showed an overall inhibitory affect on the germination ability of L. multiflorum as shown in Table 3. The higher the concentration, the more obvious the inhibitory effect. The highest germination energy reached 95.00% (50 μg·L−1, pendimethalin), which was 3.83% higher than the control. The lowest was only 3.5% (2,400 μg·L−1, alachlor), which is 96.17% lower than the control. At the same time, it was also significantly lower than other concentration treatments and other herbicide treatments. In addition, high concentrations of alachlor, metolachlor, clomazone, and isoxaflutole significantly inhibited effects on germination, and the mixed agent treatment of three concentrations had an inhibitory effect on seed germination ability compared to the control with average seed germination ability of 89.00, 85.50, and 78.00 at the mixed agent levels of 1, 5, and 10 μg·L−1, separately.

Table 3. Effects of different herbicides on germination ability of L. multiflorum.

Herbicide Concentration (μg·L−1) 0 10 30 50 100 200 600 1,200 2,400 Alachlor 91.50 ± 3.42a 88.00 ± 3.65aABC 94.00 ± 2.83aA 90.50 ± 5.00aAB 90.50 ± 7.72aAB 92.00 ± 5.89aA 30.00 ± 12.00bE 9.50 ± 9.57cD 3.50 ± 4.44cE Butachlor 91.50 ± 3.42a 90.50 ± 1.92abBC 89.00 ± 7.39abcAB 87.00 ± 4.16abB 84.50 ± 5.26bcABC 80.00 ± 2.83cdBC 77.50 ± 12.48bcdAB 76.50 ± 4.12cdA 60.00 ± 11.89eB Metolachlor 91.50 ± 3.42ab 94.50 ± 1.00aA 93.00 ± 2.58aAB 91.50 ± 4.12abAB 90.00 ± 8.00abAB 81.00 ± 5.29BcABC 72.00 ± 15.92cABC 4.00 ± 2.31eD 15.00 ± 8.41dE Imazamox 91.50 ± 3.42a 87.50 ± 3.42abBC 80.00 ± 5.89bcC 78.00 ± 3.27bcD 79.00 ± 5.29bcC 71.00 ± 5.03cD 76.50 ± 7.72cB 74.00 ± 4.32cA 58.50 ± 12.79dB Atrazine 91.50 ± 3.42a 86.50 ± 4.44aC 86.50 ± 3.00aBC 87.00 ± 3.83aAB 87.00 ± 3.83aABC 87.50 ± 3.79aA 69.50 ± 7.72bBC 72.50 ± 5.75bA 48.00 ± 7.12cBC Prometryn 91.50 ± 3.42a 87.00 ± 5.77abC 86.00 ± 4.32abBC 78.50 ± 3.42abD 88.50 ± 3.42aAB 78.50 ± 7.72abBC 84.00 ± 10.95abA 72.50 ± 7.72bA 54.00 ± 20.46cB Fomesafen 91.50 ± 3.42a 87.50 ± 5.51abABC 90.50 ± 4.73aAB 90.00 ± 1.63aAB 81.00 ± 4.76abBC 76.50 ± 2.52bC 47.50 ± 17.69cCDE 38.00 ± 7.12cdC 33.50 ± 7.00dD Quinclorac 91.50 ± 3.42a 84.00 ± 5.42abBC 89.00 ± 2.58aAB 86.00 ± 8.17abABC 85.00 ± 5.77abABC 84.50 ± 4.44abAB 90.50 ± 3.42aA 85.00 ± 11.83abA 77.00 ± 6.22bA Flumetsulam 91.50 ± 3.42a 89.50 ± 8.06aABC 88.50 ± 2.52abB 90.00 ± 3.27aAB 86.00 ± 5.42abABC 84.50 ± 7.19abABC 80.00 ± 12.11abA 76.00 ± 8.49bA 59.00 ± 13.52cB Clomazone 91.50 ± 3.42a 80.50 ± 11.36bAB 87.50 ± 6.61abB 83.00 ± 5.77abD 88.50 ± 5.75abABC 82.00 ± 5.42abABC 45.00 ± 7.75cDE 28.00 ± 1.63dC 15.00 ± 4.76eE Isoxaflutole 91.50 ± 3.42a 90.50 ± 1.92aBC 87.50 ± 3.42aBC 91.50 ± 4.12aAB 86.00 ± 8.17aABC 85.50 ± 4.73aAB 54.00 ± 2.83bCD 26.00 ± 8.17cC 12.00 ± 2.83dE Pendimethalin 91.50 ± 3.42a 89.50 ± 1.92aABC 90.00 ± 5.89aAB 95.00 ± 2.58aA 90.00 ± 5.89aAB 87.00 ± 2.58aA 67.00 ± 20.69bABC 54.00 ± 32.54bB 38.00 ± 6.53cCD 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 91.50 ± 3.42a 92.00 ± 3.65aAB 87.50 ± 5.26aBC 87.50 ± 4.44aABC 85.00 ± 3.83aABC 83.00 ± 5.29aABC 50.50 ± 9.15bDE 35.50 ± 5.75cC 30.50 ± 9.85cD Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration. The average germination speed is a negative indicator of seed tolerance during the germination period. The higher the average germination speed, the worse the seed germination condition. Overall, low and medium concentration herbicide treatments shortened the average germination speed of L. multiflorum, and high concentration herbicide treatments prolonged its average germination speed, while imazamox had no significant effect (Table 4). The results showed that lowest average germination speed was 4.74 (10 μg·L−1, 2,4-D), which was 4.82% lower than the control. The highest reached 5.50 (1,200 μg·L−1, metolachlor), which was 10.45% higher than the control. The seed germination speed after being treated with high concentrations of alachlor, metolachlor, clomazone, and isoxaflutole was significantly higher than other concentration treatments and other herbicide treatments. The mixed agent treatment of three concentrations all had an inhibitory effect on the seed germination speed compared to the control with average seed germination speed of 4.72, 4.69, and 4.75 at the mixed agent levels of 1, 5, and 10 μg·L−1, separately.

Table 4. Effects of different herbicides on mean germination speed of L. multiflorum.

Herbicide Concentration (μg·L−1) 0 10 30 50 100 200 600 1,200 2,400 Alachlor 4.98 ± 0.03b 4.83 ± 0.02bBC 4.85 ± 0.05bC 4.87 ± 0.06bAB 4.90 ± 0.07bAB 4.91 ± 0.10bBCD 5.33 ± 0.19aA 5.35 ± 0.23aABC 5.40 ± 0.31aAB Butachlor 4.98 ± 0.03ab 4.88 ± 0.02dAB 4.97 ± 0.03bcA 4.96 ± 0.06bcA 4.90 ± 0.11bcdAB 5.04 ± 0.06abA 4.84 ± 0.08dCD 4.94 ± 0.07bcdDE 5.12 ± 0.09aBCD Metolachlor 4.98 ± 0.03b 4.91 ± 0.03bAB 4.88 ± 0.05bB 4.89 ± 0.03bAB 4.93 ± 0.08bABC 5.05 ± 0.02bAB 4.95 ± 0.11bBCD 5.50 ± 0.02aA 5.46 ± 0.26aA Imazamox 4.98 ± 0.03a 4.87 ± 0.04aAB 4.88 ± 0.05aB 4.83 ± 0.07aABC 4.89 ± 0.10aABC 4.97 ± 0.08aAB 4.84 ± 0.11aCD 4.86 ± 0.23aCDE 4.95 ± 0.05aDE Atrazine 4.98 ± 0.03b 4.81 ± 0.07dBC 4.75 ± 0.02dD 4.89 ± 0.06cAB 4.90 ± 0.03bcABC 4.91 ± 0.03bcBC 4.95 ± 0.10bcBC 4.92 ± 0.04bcDE 5.16 ± 0.04aBC Prometryn 4.98 ± 0.03bc 4.77 ± 0.09eBCD 4.76 ± 0.04eD 4.80 ± 0.05deBC 4.81 ± 0.07deCD 4.83 ± 0.07deD 4.91 ± 0.08cdCD 5.04 ± 0.06bD 5.17 ± 0.15aBCD Fomesafen 4.98 ± 0.03c 4.76 ± 0.08eBCD 4.86 ± 0.05dBC 4.77 ± 0.03eCD 4.84 ± 0.03deCD 4.91 ± 0.04cdBCD 5.08 ± 0.10bAB 5.17 ± 0.07aBC 5.26 ± 0.09aBC Quinclorac 4.98 ± 0.03a 4.85 ± 0.07bcAB 4.86 ± 0.04bcBC 4.86 ± 0.04bcB 4.92 ± 0.03abAB 4.91 ± 0.07abBCD 4.80 ± 0.07cD 4.87 ± 0.07bcDE 4.91 ± 0.08abE Flumetsulam 4.98 ± 0.03ab 4.87 ± 0.06cAB 4.87 ± 0.04cB 4.76 ± 0.05dCD 4.84 ± 0.06cdCD 4.88 ± 0.10cCD 4.91 ± 0.06bcCD 4.84 ± 0.03cdE 5.04 ± 0.11aCD Clomazone 4.98 ± 0.03d 4.74 ± 0.06gCD 4.78 ± 0.07fgD 4.86 ± 0.03efB 4.83 ± 0.06fBC 4.94 ± 0.05deBC 5.16 ± 0.04cAB 5.27 ± 0.06bB 5.41 ± 0.06aAB Isoxaflutole 4.98 ± 0.03d 4.93 ± 0.03dA 4.93 ± 0.03dAB 4.82 ± 0.07eBC 4.82 ± 0.11eBC 5.01 ± 0.05dABC 5.11 ± 0.04cAB 5.28 ± 0.05bB 5.46 ± 0.07aA Pendimethalin 4.98 ± 0.03bc 4.89 ± 0.08cAB 4.94 ± 0.03bcA 4.92 ± 0.03cAB 4.95 ± 0.06bcAB 4.98 ± 0.05bcAB 5.02 ± 0.17bcABC 5.10 ± 0.20abBCDE 5.20 ± 0.05aBC 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 4.98 ± 0.03c 4.74 ± 0.03fD 4.87 ± 0.04deB 4.82 ± 0.07eABC 4.82 ± 0.06eBC 4.92 ± 0.04cdBCD 5.10 ± 0.04bAB 5.24 ± 0.04aB 5.24 ± 0.03aBCD Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration. The seed germination rate refers to the percentage of the number of germinated seeds in the total number of tested seeds, which characterizes the final germination condition of the seeds. Except that quinclorac, clomazone, and 2,4-D had no significant inhibitory effect on the germination rate, the other herbicides generally showed an inhibitory effect on the germination rate of L. multiflorum, and as the concentration increases, the inhibitory effect was significantly enhanced as shown in Table 5. The highest seed germination rate reached 100.00% (50 μg·L−1, pendimethalin), and the lowest was only 23.00 (2,400 μg·L−1, alachlor), which was 76.88% lower than the control value, it was also significantly lower than other concentration treatments and other herbicide treatments. High concentrations of alachlor and metolachlor had an obvious inhibitory effect on the germination rate of L. multiflorum seeds, and the mixed agent treatment of three concentrations inhibited the seed germination rate compared to the control with average seed germination rate of 98.00, 98.00, and 91.50 at the mixed agent levels of 1, 5, and 10 μg·L−1, separately.

Table 5. Effects of different herbicides on germination rate of L. multiflorum.

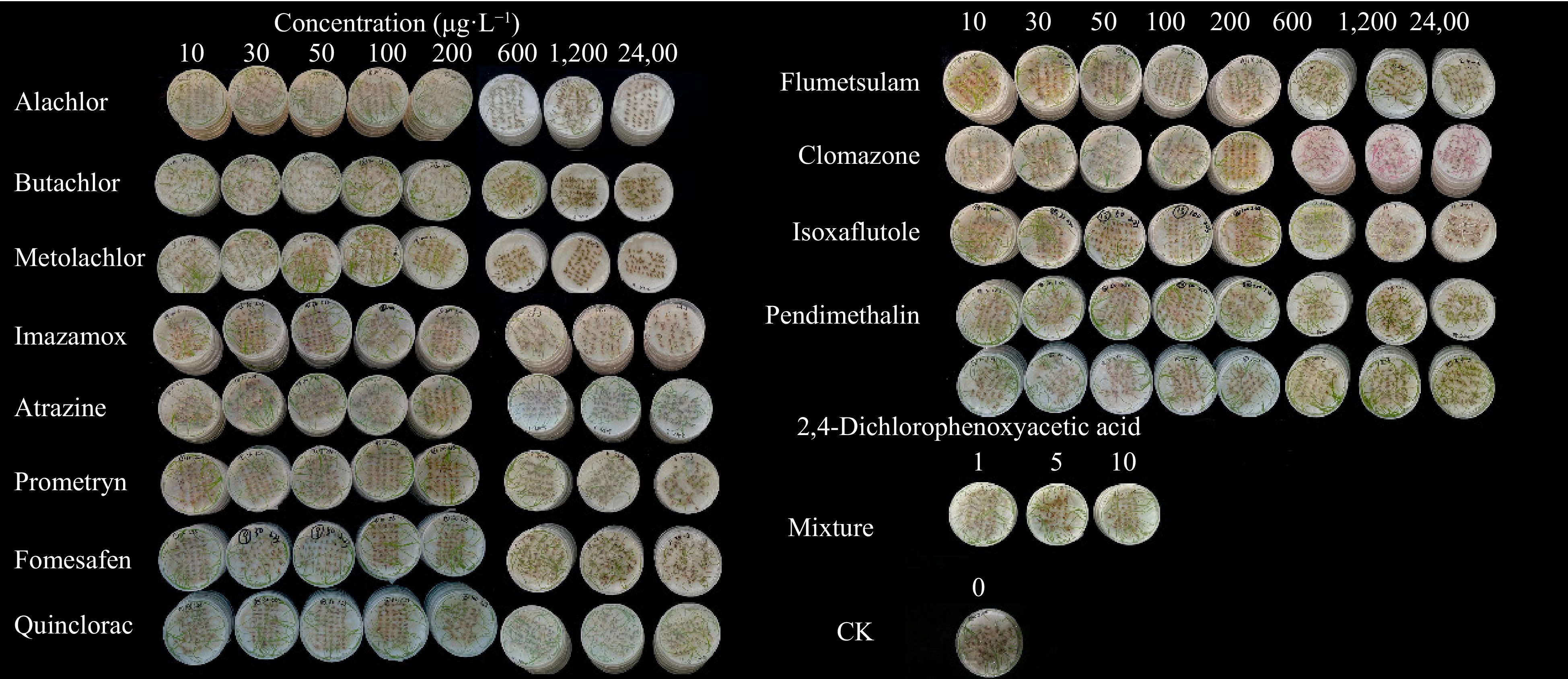

Herbicide Concentration (μg·L−1) 0 10 30 50 100 200 600 1,200 2,400 Alachlor 99.50 ± 1.00a 97.00 ± 1.16aAB 99.50 ± 1.00aAB 97.00 ± 3.46aABC 98.00 ± 2.31aA 98.50 ± 1.00aAB 70.00 ± 5.89bE 30.50 ± 5.51cE 23.00 ± 5.29dF Butachlor 99.50 ± 1.00aA 98.50 ± 1.92aA 97.50 ± 3.79aAB 95.50 ± 2.52abBC 95.50 ± 1.92abAB 97.00 ± 2.00aAB 96.00 ± 0.00aB 92.00 ± 3.27bBC 88.00 ± 3.65cCD Metolachlor 99.50 ± 1.00aA 98.50 ± 1.92aAB 98.50 ± 1.92aAB 98.00 ± 0.00aABC 96.50 ± 1.00abA 98.50 ± 1.92aAB 92.00 ± 5.89bD 74.00 ± 6.33cD 47.00 ± 6.00dE Imazamox 99.50 ± 1.00aA 95.00 ± 1.16aB 95.50 ± 1.92aB 95.50 ± 1.92abC 97.00 ± 1.16abA 92.00 ± 5.89abAB 91.00 ± 1.16bD 87.50 ± 3.42bC 80.00 ± 5.89cD Atrazine 99.50 ± 1.00aA 97.00 ± 2.58abAB 98.50 ± 1.92aAB 98.50 ± 1.92aAB 98.00 ± 1.63aA 97.00 ± 2.00abAB 93.50 ± 5.26abCD 92.00 ± 6.33bcBC 87.50 ± 5.51cCD Prometryn 99.50 ± 1.00aA 98.50 ± 3.00aAB 97.00 ± 2.58aAB 96.50 ± 1.92aBC 96.00 ± 3.27aA 97.00 ± 2.00aAB 97.50 ± 1.92aAB 97.00 ± 2.00aAB 89.00 ± 3.83bCD Fomesafen 99.50 ± 1.00aA 96.50 ± 4.73aAB 97.00 ± 2.00aAB 96.50 ± 1.92aBC 97.50 ± 2.52aA 95.50 ± 1.92aB 95.00 ± 1.16aBC 96.00 ± 1.63aAB 89.50 ± 5.26bBC Quinclorac 99.50 ± 1.00aA 95.00 ± 4.16aAB 96.50 ± 1.92aB 96.00 ± 6.73aABC 96.00 ± 4.32aA 97.00 ± 3.46aAB 98.50 ± 1.00aA 96.50 ± 1.00aAB 98.00 ± 1.63aA Flumetsulam 99.50 ± 1.00aA 98.50 ± 1.00aA 98.50 ± 1.00aAB 97.50 ± 3.79aABC 96.00 ± 4.32aA 97.00 ± 3.46aAB 96.50 ± 3.00aAB 91.50 ± 2.52bBC 91.50 ± 1.00bABC Clomazone 99.50 ± 1.00aA 90.00 ± 8.64bAB 98.50 ± 1.92aAB 93.50 ± 8.06abABC 98.50 ± 1.92aA 94.00 ± 4.32abAB 98.50 ± 1.92aA 97.00 ± 2.00abAB 92.00 ± 6.73abABC Isoxaflutole 99.50 ± 1.00aA 99.00 ± 1.16abA 97.50 ± 1.00abAB 97.00 ± 2.58abBC 97.00 ± 4.76abA 98.50 ± 1.00abAB 99.00 ± 1.16abA 98.00 ± 0.00abA 94.50 ± 5.75bABC Pendimethalin 99.50 ± 1.00aA 98.50 ± 1.00abA 99.50 ± 1.00aA 100.00 ± 0.00aA 99.50 ± 1.00aA 99.50 ± 1.00aA 95.50 ± 2.52bcBC 95.00 ± 2.58cAB 90.50 ± 4.73dABCD 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 99.50 ± 1.00aA 99.00 ± 1.16aA 98.00 ± 2.83aAB 99.00 ± 1.16aABC 96.50 ± 1.92aA 97.50 ± 1.92aAB 97.00 ± 2.58aAB 96.50 ± 1.92aAB 96.50 ± 1.00aAB Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration. With the exception that the seedling morphology under quinclorac and 2,4-D treatments were not changed significantly, the other herbicides all had varying degrees of impact on seed germination and seedling growth of L. multiflorum (Fig. 1). In general, herbicides severely inhibited the growth of L. multiflorum seedlings and caused curling, deformity, and chlorosis. The higher the concentration, the more significant the inhibitory effect. Under the treatment of high-concentrations of alachlor (2,400 μg·L−1) and metolachlor (1,200, 2,400 μg·L−1), the grass seeds did not germinate. In addition, the seedlings of L. multiflorum treated with high-concentration clomazone (above 600 μg·L−1) showed purple symptoms from the stem to the tip of the leaf, the seedlings were curled, the root system was weak, and the growth was severely inhibited, and some seeds had died. The seedlings of L. multiflorum treated with high-concentration isoxaflutole (above 600 μg·L−1) were albino, and a small number of seedlings were purple, the roots became thinner and slightly purple, the seed growth was inhibited, and some seeds died. Under the treatment of high-concentration pendimethalin (above 600 μg·L−1), the root system was partially purple, there were few fibrous roots, and some root tips were rod-shaped.

Overall, the seeds of L. multiflorum still had relatively normal germination conditions under the exposure to many of the tested herbicides. Among them, quinclorac, 2,4-D, atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, flumetsulam, and pendimethalin had little effect on the seed germination of L. multiflorum. Among them, quinclorac had the least effect on the seed germination of L. multiflorum, while the seeds treated with alachlor, metolachlor, clomazone, or isoxaflutole had poor germination conditions.

Effect of herbicides on growth characteristics of L. multiflorum

-

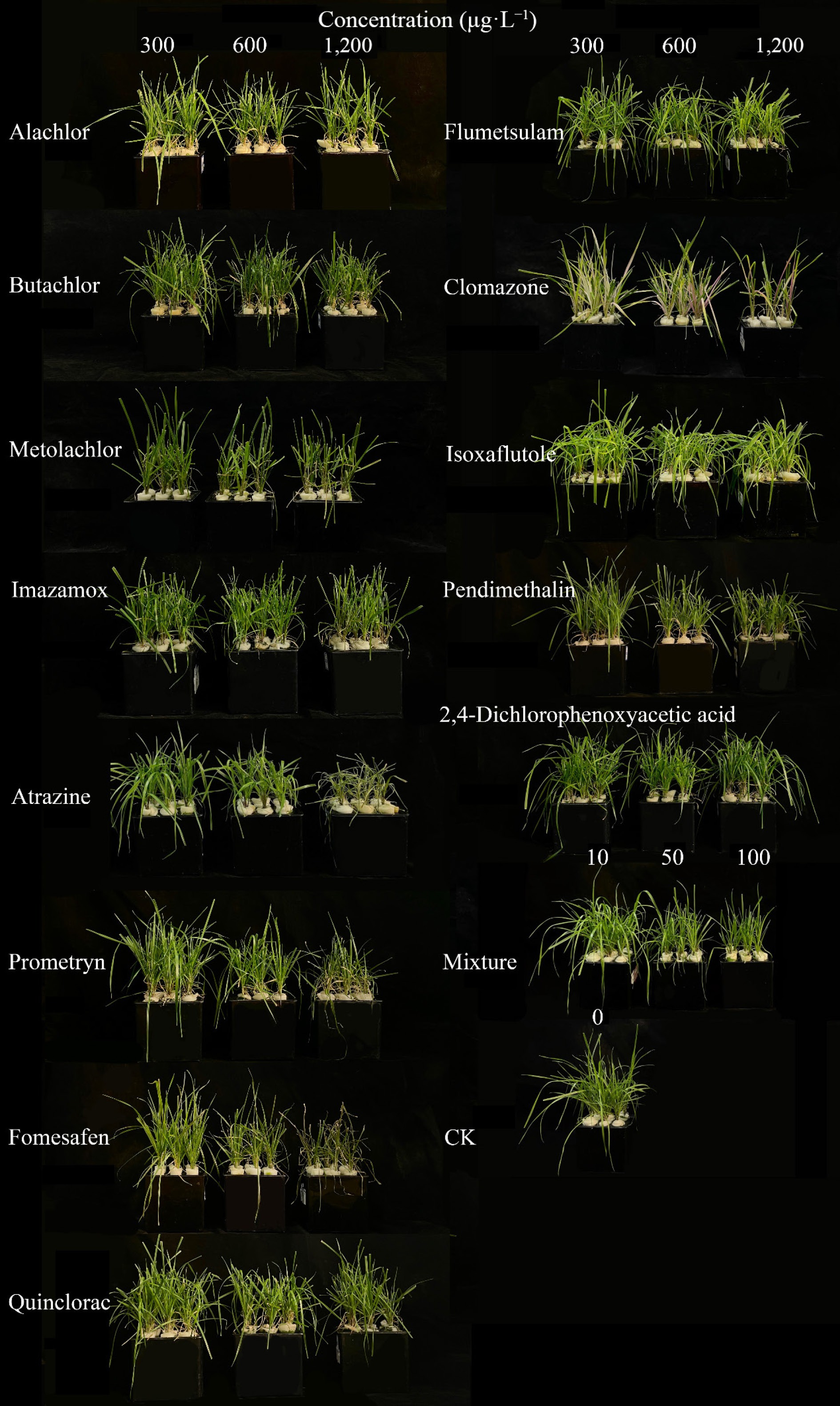

The impact of these 13 herbicides varied on the growth performance of L. multiflorum (Fig. 2). In general, they can all cause different degrees of growth retardation and dwarfing of L. multiflorum, and also cause deformity, curling, and twisting of leaves. High concentrations of atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, and pendimethalin obviously led to dwarfing of plants. Metolachlor and clomazone can cause an obvious reduction in tillering and sparse plants. High concentrations of atrazine, prometryn, and fomesafen caused obvious curling and shrinking of L. multiflorum leaves. High concentrations of atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, quinclorac, clomazone, and pendimethalin caused obvious yellowing of L. multiflorum leaves. High concentrations of clomazone and isoxaflutole caused severe whitening of L. multiflorum leaves. The herbicides which had a greater impact on the performance of L. multiflorum include atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, and clomazone.

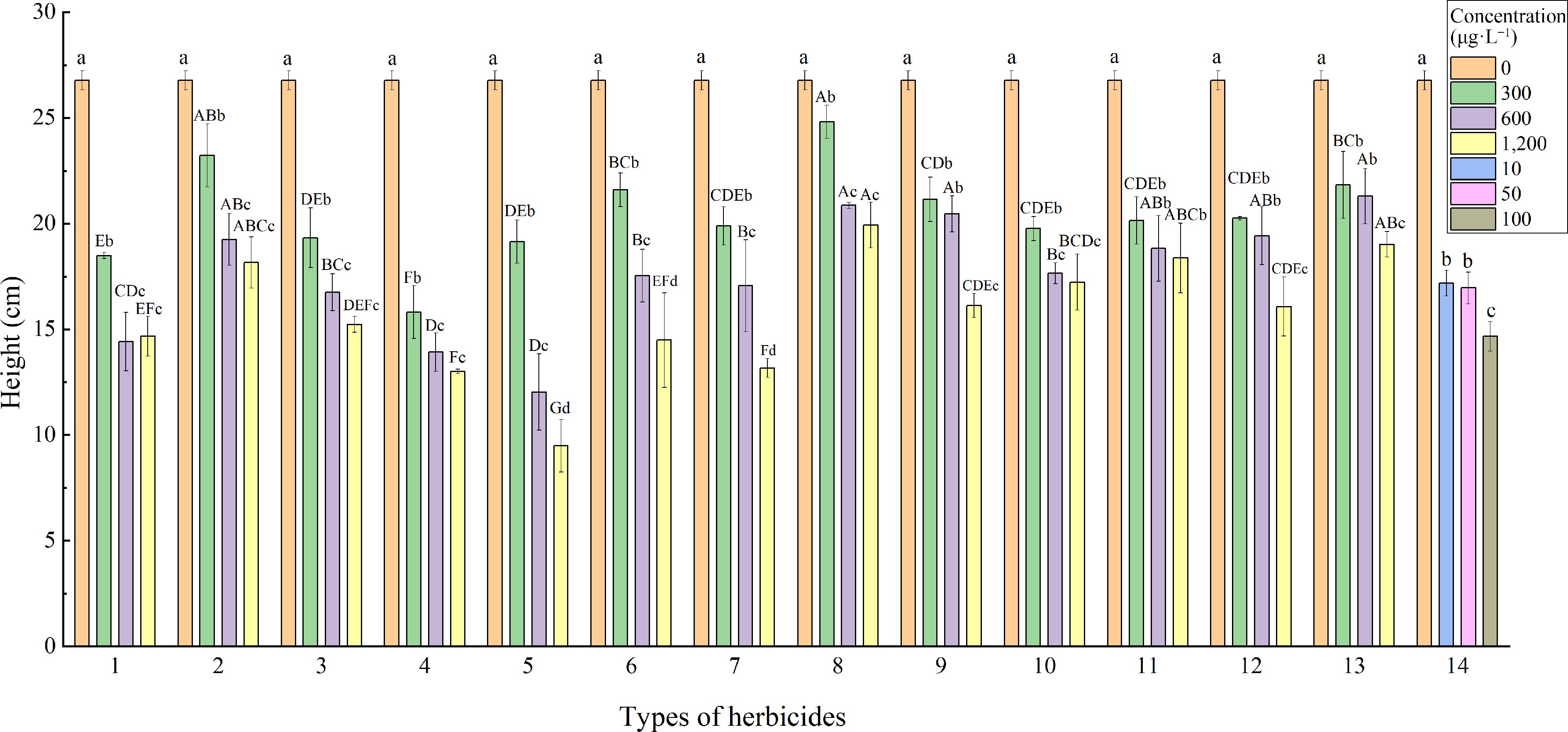

As the concentration of herbicides added increases, the height of L. multiflorum generally showed a downward trend (Fig. 3). The height of CK (26.78 cm) was significantly higher than that of the 13 herbicides and the mixed agent treatment (p < 0.05). Except for clomazone, the plant heights of the other 12 herbicides treated with 300 μg·L−1 were significantly higher than those treated with 1,200 μg·L−1. The treatment with the highest plant height was quinclorac at 300 μg·L−1 (24.82 cm), followed by butachlor at 300 μg·L−1 (23.23 cm), and there was no significant difference between the two treatments (p > 0.05), and the two herbicides had weak inhibitory effects on L. multiflorum. The herbicide with the lowest plant height under 300 μg·L−1 treatment was imazamox (15.81 cm), and the lowest plant height under 1,200 μg·L−1 treatment was atrazine (9.49 cm), which was also the lowest plant height among all treatments. The results showed that atrazine was a herbicide with strong inhibitory effect on the plant height of L. multiflorum.

Figure 3.

Effects of different herbicides on plant height of L. multiflorum. Types of herbicides - 1: Alachlor; 2: Butachlor; 3: Metolachlor; 4: Imazamox; 5: Atrazine; 6: Prometryn; 7: Flumetsulam; 8: Fomesafen; 9: Quinclorac; 10: Clomazone; 11: Isoxaflutole; 12: Pendimethalin; 13: 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; 14: Mixture (the above 13 mixed). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration.

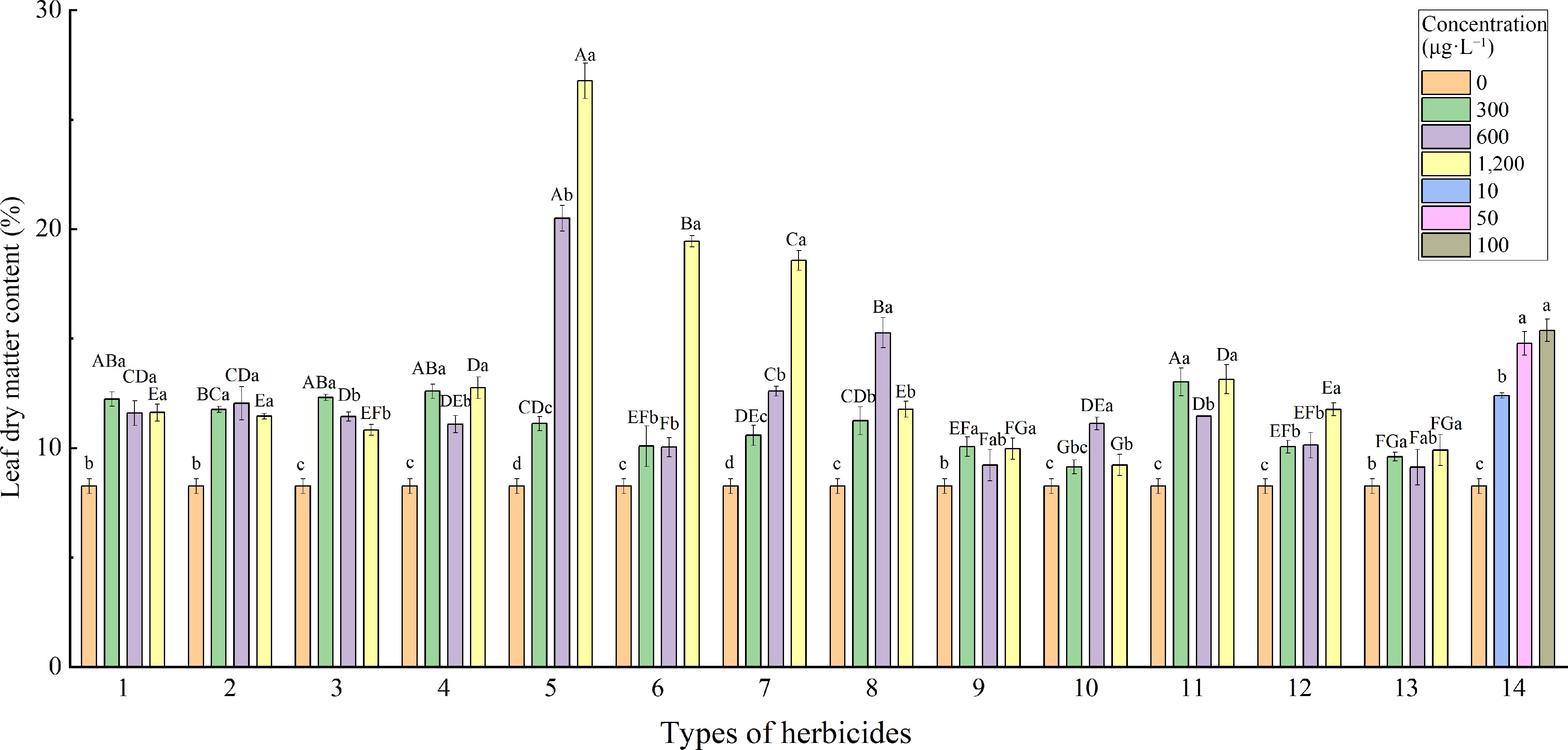

The LDMC of CK (8.26%) was significantly lower than that treated with 13 single-agent herbicides and mixed agents (Fig. 4). With the increase in concentration, the dry matter content showed an obvious gradient effect in three herbicides: atrazine, prometryn, and fomesafen. Among all treatments, the highest leaf dry matter content was treated with 1,200 μg·L−1 atrazine (26.77%). Treatment with 1,200 μg·L−1 prometryn and fomesafen also significantly increased the leaf dry matter content of L. multiflorum, which reached 19.44% and 18.57% respectively. Under three different concentrations, 2,4-D, flumetsulam and clomazone treatment had little effect on the LDMC of L. multiflorum leaves.

Figure 4.

Effects of different herbicides on leaf dry matter content of L. multiflorum. Types of herbicides - 1: Alachlor; 2: Butachlor; 3: Metolachlor; 4: Imazamox; 5: Atrazine; 6: Prometryn; 7: Flumetsulam; 8: Fomesafen; 9: Quinclorac; 10: Clomazone; 11: Isoxaflutole; 12: Pendimethalin; 13: 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; 14: Mixture (the above 13 mixed). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration.

Effect of herbicides on physiological characteristics of L. multiflorum

-

The treatments of metolachlor, atrazine, fomesafen, and flumetsulam showed a trend of decreasing total Chl and Car contents with increasing concentration (Fig. 5). This might because the higher the herbicide concentration, the stronger the inhibitory effect on photosynthesis. Due to the damage of herbicide treatment to the leaves of L. multiflorum, the establishment of the protection mechanism of L. multiflorum was promoted. With the increase in treatment concentration, alachlor treatment leads to an increase of total Chl and Car contents with increasing concentration.

Figure 5.

Effects of different herbicides on photosynthetic pigment content of L. multiflorum. Types of herbicides - 1: Alachlor; 2: Butachlor; 3: Metolachlor; 4: Imazamox; 5: Atrazine; 6: Prometryn; 7: Flumetsulam; 8: Fomesafen; 9: Quinclorac; 10: Clomazone; 11: Isoxaflutole; 12: Pendimethalin; 13: 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; 14: Mixture (the above 13 mixed). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration.

Imazamox, atrazine, and the mixture of 50 and 100 μg·L−1 all caused extremely significant decreases in Chl and Car contents. Overall, Chla, Chlb, total Chl, and Car showed a similar trend. Alachlor had little effect on the photosynthetic pigment content of L. multiflorum, while imazamox, atrazine, clomazone, and isoxaflutole have a greater effect.

The Fv/Fo and Fv/Fm of L. multiflorum treated with three concentrations of atrazine, prometryn, clomazone, and isoxaflutole were significantly lower than those of CK (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6). Among them, atrazine, prometryn, and clomazone had more obvious inhibitory effects on the fluorescence values, and the inhibitory effects of atrazine on Fv/Fo and Fv/Fm showed an obvious gradient effect of 1,200 μg·L−1 > 600 μg·L−1 > 300 μg·L−1.

Figure 6.

Effects of different herbicides on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of L. multiflorum. Types of herbicides − 1: Alachlor; 2: Butachlor; 3: Metolachlor; 4: Imazamox; 5: Atrazine; 6: Prometryn; 7: Flumetsulam; 8: Fomesafen; 9: Quinclorac; 10: Clomazone; 11: Isoxaflutole; 12: Pendimethalin; 13: 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; 14: Mixture (the above 13 mixed). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration.

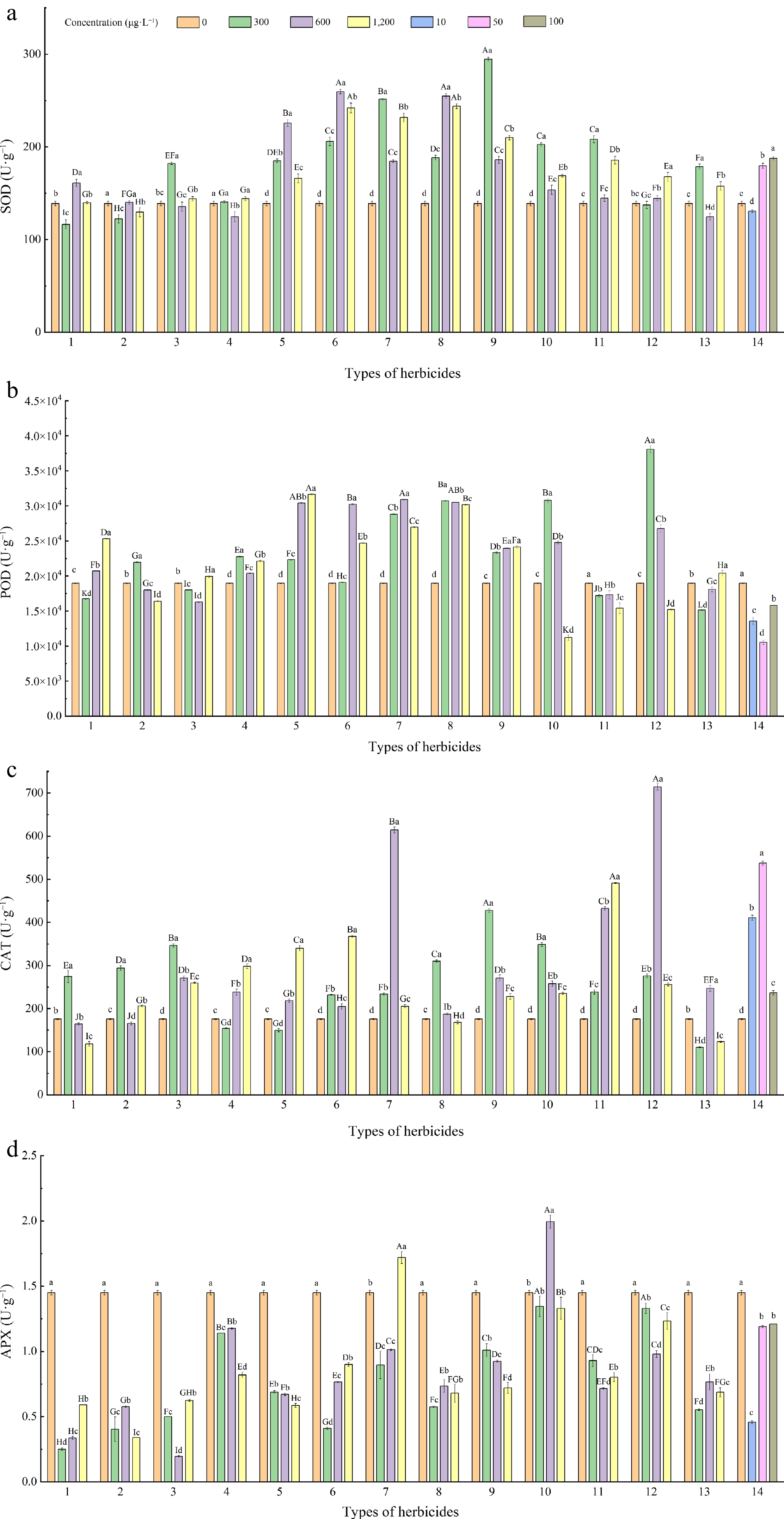

The results showed that different concentrations of atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, quinclorac, flumetsulam, and clomazone significantly increase the SOD activity of L. multiflorum leaves (Fig. 7). Among them, L. multiflorum treated with 300 μg·L−1 flumetsulam had the highest SOD activity (294.73 U·g−1). The mixed agent treatment of 50 μg·L−1 and 100 μg·L−1 were also increased the SOD activity of L. multiflorum leaves. The activity of SOD increased with the increase treatment concentration of pendimethalin and the mixture.

Figure 7.

Effects of different herbicides on leaf antioxidant enzymes of L. multiflorum. Types of herbicides - 1: Alachlor; 2: Butachlor; 3: Metolachlor; 4: Imazamox; 5: Atrazine; 6: Prometryn; 7: Flumetsulam; 8: Fomesafen; 9: Quinclorac; 10: Clomazone; 11: Isoxaflutole; 12: Pendimethalin; 13: 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; 14: Mixture (the above 13 mixed). Different lower-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different concentrations of the same herbicide, different upper-case letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments of different herbicides at the same concentration.

Different concentrations of atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, quinclorac, and flumetsulam significantly increased the POD activity of L. multiflorum leaves (Fig. 7). L. multiflorum treated with 300 μg·L−1 pendimethalin had the highest POD activity (3.81 × 104 U·g−1), while the treatment of 1,200 μg·L−1 pendimethalin had an inhibitory effect (1.52 × 104 U·g−1). The activity of POD increased with the increased treatment concentration of alachlor, atrazine, and 2,4-D, while it decreased with the increased treatment concentration of butachlor, clomazone, isoxaflutole, and pendimethalin.

Different concentrations of atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, quinclorac, flumetsulam, clomazone, isoxaflutole, and pendimethalin significantly increase the CAT activity of L. multiflorum leaves (Fig. 7). Among them, the highest CAT activity of L. multiflorum was treated with 600 μg·L−1 pendimethalin (914.34 U·g−1). The mixed agent treatment at different concentrations will also increase the CAT activity. The activity of CAT was increased with the increased treatment concentration of imazamox, atrazine, and isoxaflutole, while it was decreased with the increased treatment concentration of alachlor, metolachlor, quinclorac, flumetsulam, and clomazone.

The results showed that different concentrations of herbicide treatments significantly reduced the activity of APX except 1,200 μg·L−1 fomesafen (1.72 U·g−1), and 600 μg·L−1 clomazone (2.00 U·g−1) (Fig. 7). Metolachlor at 600 μg·L−1 had the strongest inhibitory effect on APX activity (0.20 U·g−1), followed by alachlor at 300 μg·L−1 (0.25 U·g−1). The activity of APX increased with the increased treatment concentration of alachlor, prometryn, flumetsulam, fomesafen, and the mixture, while it decreased with the increase of treatment concentrations of atrazine.

Correlation between variables

-

Based on the above experimental results, the membership function value method was used to comprehensively evaluate the four germination indexes and 13 growth and physiological indexes of L. multiflorum, so as to evaluate the tolerance of L. multiflorum to different herbicides and their different concentrations.

The average value method of membership function was used to standardize the indicators. The calculation equations are as follows:

$ \mu(Xi)=\dfrac{Xi - Xmin}{ Xmax - Xmin} $ $ \mu(Xj)=\left( 1-\dfrac{ Xi - Xmin }{Xmax - Xmin}\right),\;\; j=1,2,3\cdots n\;{}$ In the above two equations, Xi is the measured value of the indicator; Xmin, Xmax are respectively the minimum and maximum values of a certain indicator of all tested materials. The first equation indicates that the indicator is positively correlated with tolerance ability, and the second indicates that the indicator is negatively correlated with tolerance ability.

According to the ranking of membership function values of germination indicators of L. multiflorum seeds under different herbicide treatments (Supplementary Table S2), it was concluded that the top five herbicides in descending order for the tolerance of L. multiflorum seeds to single herbicides were: 10 μg·L−1 2,4-D, 50 μg·L−1 flumetsulam, 30 μg·L−1 atrazine, 10 μg·L−1 prometryn, and 50 μg·L−1 fomesafen. Overall, L. multiflorum seeds had strong tolerance to atrazine, prometryn, quinclorac, and flumetsulam, but not tolerant to butachlor, metolachlor, imazamox, clomazone, and isoxaflutole. The tolerance to concentration in descending order was low concentration > medium concentration > high concentration.

According to the ranking of membership function values of growth and physiological indicators of L. multiflorum plants under different herbicide treatments (Supplementary Table S3), we concluded that the top five herbicides in descending order of tolerance of L. multiflorum plants to single herbicides were: 300 μg·L−1 flumetsulam, 1,200 μg·L−1 alachlor, 300 μg·L−1 quinclorac, 300 μg·L−1 fomesafen, and 1,200 μg·L−1 quinclorac. Overall, L. multiflorum plants had strong tolerance to quinclorac and weak tolerance to imazamox, atrazine, clomazone and isoxaflutole. The tolerance to concentration was in descending order of low concentration > medium concentration > high concentration.

-

The germination rate of seeds reflects the overall germination ability of seeds, and the germination index, germination ability, and average germination speed reflect the germination speed, uniformity, and germination quality of seeds[23]. The herbicides have different degrees of impact on the seed germination process. Zhou found that when the concentration of pendimethalin is 330 mg·L−1, it had a promoting effect on the germination rate, germination ability, and germination index of seeds of five crops including wheat, corn, soybean, mung bean, and peanut and there was an inhibitory effect when exceeded this concentration[24]. Han & Zhang found that 2,4-D at a concentration of 72 mg·L−1 can promote the germination of wheat seeds, and exceeded this concentration range, it showed an inhibitory effect[25]. In this study, pendimethalin and 2,4-D had little effect on the seed germination of L. multiflorum and low concentrations (10, 30, 50, 100) of 2,4-D can promote the germination index. In general, the herbicides that had a greater impact on the germination ability of L. multiflorum seeds included alachlor, metolachlor, imazamox, clomazone, and isoxaflutole, and a lot of herbicides showed promotion at low concentrations and inhibited at high concentrations.

It was found that under the treatment of high-concentration herbicides, the seedlings produced corresponding damage symptoms. Among them, the effect of amide herbicides alachlor, butachlor, metolachlor, and the organic heterocyclic clomazone and isoxaflutole were more obvious. Studies have shown that amide herbicides can cause damage to plant root tip cells, inhibit mitosis of root tip cells and root growth, resulting in short and soft roots[26]. In the study on wheat, it was found that amide herbicides mainly inhibited the growth of roots and young buds, causing dwarfing and deformity of seedlings and young buds and leaves cannot be fully unfolded[27]. Chloracetamide herbicide varieties usually inhibited seed germination and the growth of young buds, causing severe dwarfing of young buds and death[28]. The amide herbicide metolachlor is absorbed by young buds and then conducts upward, inhibiting seed protein synthesis, affecting the infiltration of choline into phospholipids and interfering with the formation of lecithin, and ultimately destroying the growth of young buds and roots[29]. In addition, some studies have found that clomazone inhibited the biosynthesis of chlorophyll and carotenoids in sensitive plants by inhibited deoxy-D-xylulose phosphate synthase (DXS), resulting in plant whitening, yellowing, or chlorosis[30]. In addition, isoxaflutole is a hydroxyphenyl pyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD) inhibitor, by inhibiting HPPD activity leads to a decrease in plastid quinones which is a necessary synergistic factor for phytoene desaturase to complete its normal function. This indirectly inhibits the biosynthesis of carotenoids[31]. Therefore, this explains the corresponding changes of L. multiflorum under the treatment of clomazone and isoxaflutole.

The growth and physiology of L. multiflorum plants in response to herbicides

-

After 5 d of hydroponic exposure treatment, typical symptoms of herbicide poisoning appeared in L. multiflorum. The symptoms under the treatment of atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, clomazone, and isoxaflutole were more obvious. Imazamox, atrazine, clomazone, and isoxaflutole significantly inhibited the production of Chla, Chlb, Chl, and Car in L. multiflorum. In conclusion, there are different mechanisms and damage symptoms with different types of herbicides.

Imazamox is a biosynthesis inhibitor that can inhibit the first reaction in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids required to catalyze plant growth and development by acetolactate synthase (ALS), causing plant metabolic disorders, leading to a decrease in the photosynthetic capacity of L. multiflorum, affecting the synthesis of chlorophyll, and a decrease in Chla, Chlb, and Chl, which make plants turn yellow and grow slowly[32]. Existing studies have proven that gramineous plants have a low tolerance to ALS inhibitor herbicides[33], which explains the high sensitivity of L. multiflorum to imazamox.

Atrazine, prometryn, and fomesafen are all photosynthesis inhibitors. Dang & Gao[34] found that atrazine did not affect the germination of Secale cereale seeds but affected the development after emergence, and it was similar to the results of this study. Therefore, it was supposed that the early development phenomenon of L. multiflorum seedlings and the growth status of plants may be related to atrazine affecting the photosynthesis of seedlings. Yang et al.[35] found that atrazine had a significant inhibitory effect on the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of four vegetables, and the Fv/Fm decreased by 10%, which was similar to the results of this study. The toxic reaction of plants to atrazine is closely related to its absorption and accumulation[36]. Sánche et al.[37] evaluated the ability of tall fescue, barley, ryegrass, and corn to degrade atrazine in soil, the results showed that the four plants could absorb and detoxify atrazine to a certain extent, but when the initial dose of atrazine exceeds 2 mg·kg−1, plant toxicity occurred, biomass decreases, and chlorosis, stunted growth, and even leaf death occurred under the treatment of a concentration of 10 mg·kg−1, which is consistent with the results of this study. Therefore, it was supposed that the effect of atrazine on L. multiflorum is related to its large accumulation in tissues.

Clomazone is a plant growth inhibitor. The roots and young buds of plants can effectively absorb clomazone. It is transported upward from the roots through the stem with transpiration and reaches the leaves through the xylem by diffusing, inhibiting the synthesis of chlorophyll and carotene in plants[38,39]. L. multiflorum is a clomazone-sensitive plant, after absorbing clomazone, the plant conductivity deteriorates sharply, because photosynthesis is blocked, leaves cannot synthesize chlorophyll and carotene. In this study, the synthesis of Chlb in L. multiflorum was severely inhibited when treated with clomazone for 5 d, and the Chl content was significantly reduced. Therefore, L. multiflorum turns albino in a short time, chlorosis with purple color and then dies.

Isoxaflutole is an HPPD inhibitor. HPPD is an important enzyme in the tyrosine metabolism process in organisms. Tyrosine generates 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid under the action of tyrosine aminotransferase, and then HPPD catalyzes the conversion of p-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid into homogentisic acid under the participation of O2, which is converted into plastid quinones and tocopherol in plants[40]. When the activity of HPPD is inhibited, the normal metabolism of tyrosine in plants will be blocked, resulting in the lack of carotenoids and the weakening of chlorophyll photooxidation, affecting photosynthesis, and thus causing yellowing and slight albinism of L. multiflorum plants.

Leaf dry matter content (LDMC) is a functional trait of plants and reflects the ability of plants to obtain and maintain resources such as light, water, and nutrients[41]. Plant leaves with lower LDMC have a stronger production capacity and the greater the LDMC content, the stronger the resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses[42]. In this study, after treatment with different herbicides, the LDMC of L. multiflorum was increased, indicating that L. multiflorum responded to heterogeneous environments by increasing LDMC[43]. As LDMC increases, the tolerance of plants to herbicide stress increases. The promoting effect of different herbicides on LDMC is different, which is related to the mechanism and molecular target of herbicides. In this study, the herbicides with strong promoting effects on LDMC were atrazine, fomesafen, and quinclorac, indicating that the leaves of L. multiflorum treated with atrazine, fomesafen, and quinclorac had obvious resistance to herbicide stress, which improved the plant tolerance.

Antioxidant enzymes have an affinity for various types of xenobiotics, which enables them to participate in many detoxification processes[44]. In this study, after treatment with different concentrations of herbicides, the activities of SOD, CAT, and POD in L. multiflorum increased overall, indicating that the ROS scavenging system was stimulated after herbicides entered L. multiflorum and increased activities of SOD, CAT, and POD enzymes to protect plants from herbicides. Liu et al.[45] found that abiotic stress can induce an increase in the contents of SOD, POD, and CAT in perennial ryegrass, and reduce the oxidative damage to the plant, which is consistent with this study. In this study, the activity of APX decreased, and only increased under the treatment of clomazone. Tan et al.[46] also found that under the stress of herbicides such as acetochlor, fluoroglycofen-ethyl, and paraquat, the activity of APX was significantly reduced in grape leaves. This may be because the antioxidant mechanism of APX is different from that of SOD, CAT, and POD, it mainly catalyzes ascorbic acid and H2O2 and promotes the metabolism and conversion of H2O2 in plants, and it is a key enzyme to clear H2O2 in chloroplasts.

In addition, some studies have found that the SOD activity of plant leaves is positively correlated with plant dwarfing. The higher the activity, the more dwarfed the tree. This is similar to the results of this study in that the plant heights of L. multiflorum treated with atrazine, prometryn, and fomesafen were all inhibited, and the SOD activity was relatively high. It was supposed that the reason was that the high-activity SOD and CAT in L. multiflorum eliminates a large amount of reactive oxygen species, resulting in blocked cell wall elongation and thus dwarfing of plants. In addition, SOD activity also increased with the increase of dwarfing degree. Therefore, this is an adaptive regulatory mechanism of L. multiflorum in response to the increase of O2−, H2O2, etc. and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in plants under herbicide stress conditions, so as to reduce cell damage caused by the increase of O2−[47].

-

A lot of the research on the relationships between plants and herbicides focuses on tolerance mechanisms and other aspects, while there are relatively few studies on the tolerance of plants to herbicides. In terms of turfgrass, there are relatively few studies on the tolerance and tolerance mechanism of turfgrass to herbicides. This study investigated the effects of 13 different herbicides on the seed germination ability, seedling growth, and physiological metabolism of L. multiflorum. The research results showed that L. multiflorum had strong tolerance to quinclorac and 2,4-D, and weak tolerance to imazamox, atrazine, clomazone, and isoxaflutole. This study provides data support and a theoretical basis for the remediation of herbicide residues in the environment by L. multiflorum, and provides a reference for research on the remediation effect of turfgrass on herbicides.

This research was funded by the Turf Producers China of Chinese Turfgrass Society.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sun Y, Jia F; data collection: Chen J, Li Y, Ma C; analysis and interpretation of results: Chen J, Wang Y, Ma C; draft manuscript preparation: Hu Q, Ma C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Overview of herbicides.

- Supplementary Table S2 Comprehensive evaluation results of germination tolerance of L. multiflorum seeds under different herbicide treatments.

- Supplementary Table S3 Comprehensive evaluation results of growth and physiological tolerance of L. multiflorum plants under different herbicide treatments.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ma C, Chen J, Wang Y, Jia F, Li Y, et al. 2024. The evaluation of herbicide tolerance on Lolium multiflorum. Grass Research 4: e028 doi: 10.48130/grares-0024-0026

The evaluation of herbicide tolerance on Lolium multiflorum

- Received: 03 November 2024

- Revised: 29 November 2024

- Accepted: 11 December 2024

- Published online: 26 December 2024

Abstract: Lolium multiflorum is widely used to remediate pollutant residues in the environment. The tolerance of plants to pollutants is a key factor affecting the phytoremediation effect and limiting plant application. In this study, 13 herbicides including alachlor, butachlor, metolachlor, imazamox, atrazine, prometryn, fomesafen, quinclorac, flumetsulam, clomazone, isoxaflutole, pendimethalin, and 2,4-D with long residual time and serious environmental toxicity were used for evaluation of the tolerance ability of L. multiflorum. The seed germination and plant growth, as well as physiological characteristics of L. multiflorum after exposure to different herbicides concentrations were explored. The membership function value method was used to analyze the tolerance of L. multiflorum to different herbicides. Results revealed that low-concentration herbicides promoted the seed germination and plant growth of L. multiflorum, while high-concentration herbicides performed an inhibitory effect. The antioxidant enzyme activities in plants were increased under herbicide treatment. L. multiflorum had strong tolerance to quinclorac and weak tolerance to imazamox, atrazine, clomazone, and isoxaflutole.

-

Key words:

- Lolium multiflorum /

- Phytoremediation /

- Herbicide /

- Tolerance /

- Seed germination /

- Growth characteristic