-

The adoption of alternative zero-carbon fuels facilitates a significant reduction in CO2 emissions, thereby playing a crucial role in addressing global climate change. Ammonia, as a carbon-free and hydrogen-rich fuel with favorable transport properties, can mitigate challenges associated with its direct combustion in practical combustion systems when co-fired with hydrocarbon fuels[1−3]. During NH3-hydrocarbon co-combustion, C4H6, a key pyrolysis product, undergoes dehydrogenation to generate the C4H5 radical[4]. C4H5 radical engages in addition reactions with HCN[5−7], constituting one primary pathway for pyridine formation and supplying the essential four-carbon backbone for the construction of nitrogen-containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (NPAHs)[8]. Crucially, pyrrole, pyridine, and nitrogen-substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) exhibit higher toxicity than their non-nitrogenated counterparts. The substitution of carbon atoms with nitrogen introduces heterocyclic rings and cyano groups, enhancing molecular lipophilicity. This property facilitates dissolution into organic tissues, elevating carcinogenic risks[9]. Furthermore, atmospheric pyridine and N-PAHs may contaminate water or soil systems, potentially causing DNA replication errors and mutagenic effects in flora and fauna[9]. Consequently, elucidating pyrrole and pyridine formation pathways has emerged as a critical research frontier in NH3-hydrocarbon co-combustion.

Multiple studies were conducted to explore the formation mechanisms of NPAHs, such as pyrrole and pyridine, in the co-combustion of ammonia and hydrocarbons by utilizing advanced experimental detection techniques and simulation analysis. Ao et al.[10] revealed the chemical mechanism by which HCN inhibits the growth of PAHs from the perspective of energy barriers. The high barrier of the nitrogen heterocyclization pathway forces the reaction to generate inert acyl nitriles, thereby blocking the chain growth of HACA. In contrast, pyrrole-pyridine mainly adds to the aromatic radical at the N-terminal or C-terminal of HCN, forming through a low-energy barrier cyclization reaction, and the low-temperature condition is more conducive to the ring-closure pathway. Chen et al.[11] further revealed the pyridine formation pathway through C2H2/CH3CN/N2 and C2H2/C2H3CN/N2 jet-stirred reactor experiments combined with the RRKM-ME theory. The energy barrier for the cyclization of HCN with n-C4H5 radical to form pyridine is 78% higher than the C2H2 + C2H2CN pathway. At high temperatures, the C2H2 + C2H2CN pathway dominates, mainly generating pyridine. Yan et al.[12] performed high-temperature pyrolysis experiments combined with product analysis, and discovered that pyrrole is formed by the polymerization of methylene and ammonia dehydrogenation products with C2H2, while pyridine is formed by the cyclization of acyl groups. The nitrogen atom significantly increases the energy barrier for the dehydrogenation of carbon on the ring, making it difficult for heterocyclic compounds to further grow into PAHs, thereby inhibiting the formation of soot precursor. Tang et al.[13] revealed the difficult of H-atom abstraction through high-precision ab initio calculations (QCISD[T]/CBS//M06-2X method) combined with transition state theory: The average energy barrier for abstracting H atoms from the α-position of alcohols and ethers by NH2 radical (such as α-primary position is 7.80 kcal/mol) is 23%–30% lower than that of alkanes (10.11 kcal/mol), resulting in a significant increase in the rate constant within the temperature range of 500–2,000 K, up to six times, thereby dominating the reaction branching ratio. These studies have clarified the significance of carbon and nitrogen species in the formation of NPAHs. HCN can affect the energy barrier of the growth path of NPAHs, while NH2, as an important product in ammonia hydrocarbon combustion, the reactions involving NH2 will significantly influence the rate coefficients of important reactions in ammonia-blended combustion. However, the roles of HCN and NH2 in the formation and evolution mechanism of NPAHs are still not fully understood.

Several studies have demonstrated the influence of HCN and NH2 on the reactions occurring in the growth pathways of NPAHs. Xu et al.[4] determined HCN as the most abundant C−N product in the ReaxFF MD simulation of the NH3/C2H4/O2 system. This was further verified by quantum chemical calculations, and based on this discovery, a new path for the formation of cyanide-substituted PAHs through the reaction with naphthyl groups was proposed, but the pyridine ring could not be effectively formed. Liu et al.[14] further revealed the formation of NPAHs path through C2H2/HCN/N2 jet-stirred reactor experiments combined with the RRKM-ME theory: the energy barrier for HCN to cyclize with 1-naphthyl radical to form pyridine (43.2 kcal/mol) is 167% higher than the HACA mechanism, resulting in a low yield of the heterocyclic ring (mainly 1-naphthylacetonitrile); in contrast, Wang et al.[8] confirmed that NH3/NH2 directly adds at the armchair site of PAHs (energy barrier 14.3 kcal/mol), forms an amino intermediate such as 2-aminobiphenyl, and efficiently cyclizes to form a pyrrole structure (such as carbazole). It accounted for 58% of the NPACs in the diffusion flame, and XPS detected C-(NH)-C bonds on the soot surface (accounting for 34.6%), while Zhang et al.[15] jointly confirmed with GC-MS and ReaxFF simulation: small molecule C−N species (HCN or NH2) tend to generate edge substituents, with only 7% of N embedded in the core of the soot, highlighting the kinetic advantage of the pyrrole ring and the spatial limitation of the pyridine ring. These studies have revealed the effects of HCN and NH2 on NPAHs, but have overlooked the research on the formation of the ring structure that is important for the growth of NPAHs in these compounds. This directly determines the rate-limiting step of NPAHs. HCN and NH2 can easily form the ring structure that is important for the growth of NPAHs with C4H6. The competitive relationship between HCN and NH2, as well as the C−N interaction, is of great significance for understanding the formation pathways of NPAHs.

Therefore, this study investigates the mechanisms by which HCN and NH2 interact with carbon species to form NPAHs. Based on ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations, ten system configurations were constructed using C4H6, C2H2, NH2, and HCN. This study focuses on elucidating how C−N interactions regulate the formation pathways of NPAHs. The competitive mechanism between nitrogen sources and carbon sources is clarified through the tracking of key intermediates and bond order evolution analysis.

-

The ReaxFF molecular dynamics was proposed and developed by van Duin et al.[16,17]. The ReaxFF force field accounts for both bonding and non-bonding interactions, which together form the system's energy expression, as shown below:

$ {E}_{\mathrm{t}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}}={E}_{\mathrm{b}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{d}}+{E}_{\mathrm{o}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}}+{E}_{\mathrm{u}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}}+{E}_{\mathrm{l}\mathrm{p}}+{E}_{\mathrm{v}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}}+{E}_{\text{tor}}+{E}_{\mathrm{v}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{W}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{s}}+{E}_{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{b}} $ The total energy, Etotal, consists of several contributing terms. The first six terms on the right side of the equation contribute to bonding energy: bond energy, over-coordination penalty, under-coordination stability, lone pair electron energy, valence angle energy, and torsion angle energy. The last two terms, which contribute to non-bonding energy, are the Van der Waals energy and Coulomb energy. ReaxFF MD has been widely applied to various fields, including the combustion of alkanes[18,19], the physicochemical processes in polymer thermal degradation, and the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and soot[20−22].

At temperatures below 2,500 K, the rate of the ammonia decomposition reaction is extremely low, making it difficult to observe the complete reaction pathway within the limited simulation time. On the contrary, when the temperature exceeds 3,500 K, the reaction rate is too fast, making it challenging to capture the intermediate products and intermediate reactions. Therefore, 2,900 K lies within the optimal temperature range determined in this study, effectively balancing the completeness of the reaction and the complexity of the reaction path.

In this study, the combustion systems were constructed using Materials Studio software[23]. System densities were modified to maintain uniform cube dimensions by setting identical molecular number densities[24]. This model scale is sufficient for investigating pyrolysis product formation mechanisms, conversion pathways, and temporal evolution, effectively simulating intramolecular bond formation and cleavage during pyrolysis. Similar models with comparable atomic numbers have been used in studies of the pyrolysis/combustion of many gaseous substances. ReaxFF MD simulations were performed using the REAXC package in the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulation (LAMMPS)[25]. The C/H/O/N-2019 force field, developed by Malgorzata Kowalik et al.[26], was used. Validation of this force field encompasses multiple domains, notably the oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as well as hydrocarbon fuel pyrolysis and combustion[27,28]. Prior to production runs, each system undergoes a 600 ps energy minimization and equilibration phase at 298 K to remove artifacts and minimize energy. All subsequent production MD simulations were uniformly extended to 600 ps. Simulations were performed in the canonical ensemble (NVT) employing the Nosé-Hoover thermostat with a damping constant of 0.1 ps. These studies demonstrate that a time step of 0.1–0.5 fs effectively captures characteristic parameters of the reaction process. More detailed simulation information is presented in the appendix.

Molecular dynamics simulation system

-

The system settings mainly take into account the influence of free radical concentration changes, the competition between NH2 and HCN, and the C−N interaction in the system. The detailed parameter settings are shown in Table 1. Ten independent simulations were conducted in this study, among which the pathway leading to pyridine formation via HCN addition occurred seven times, while the pathways producing other compounds were observed three times. This study selected the trajectory that appeared most frequently in the repeated simulations. This trajectory represents the most commonly observed (i.e., with the highest probability) dynamic evolution path under the given reaction conditions. This is an effective and commonly used method to visually display the most likely behavioral pattern of the system when approaching an equilibrium state.

Table 1. Parameters of the molecular dynamics simulation system.

System number Molecule number C4H6 C2H2 NH2 HCN S1 100 250 0 0 S2 100 500 0 0 S3 100 250 250 0 S4 100 0 250 0 S5 100 0 500 0 S6 100 0 0 250 S7 100 0 0 500 S8 100 250 0 250 S9 100 0 250 250 S10 100 250 250 250 The concentration of NH2 ranges from 250 in S4 to 500 in S5, and that of HCN ranges from 250 in S6 to 500 in S7. This allows for a comparison of the effect of nitrogen source concentration on the reaction rate or yield. The system settings analyze the competition between NH2 and HCN by combining nitrogen and carbon sources. For example, S9 (C4H6 + NH2 + HCN) directly compares the behavior when two nitrogen sources coexist; S10 includes all components to simulate the real environment and assess the mutual influence of NH2 and HCN when multiple reactants coexist, and compare S3 (C4H6 + C2H2 + NH2), S8 (C4H6 + C2H2 + HCN), and S9, which can reveal the interference between nitrogen sources. The C−N interaction and the formation of C−N bonds are key steps in the formation of pyrroles and pyridines, involving the interaction between carbon source (C4H6 or C2H2) and nitrogen source (NH2 or HCN). The system highlights the effects of different C−N combinations by fixing C4H6 and varying other components. To study the competitive effects of HCN, NH2, and carbon sources, four groups, S1, S2, S8, and S10, were set up for comparison.

-

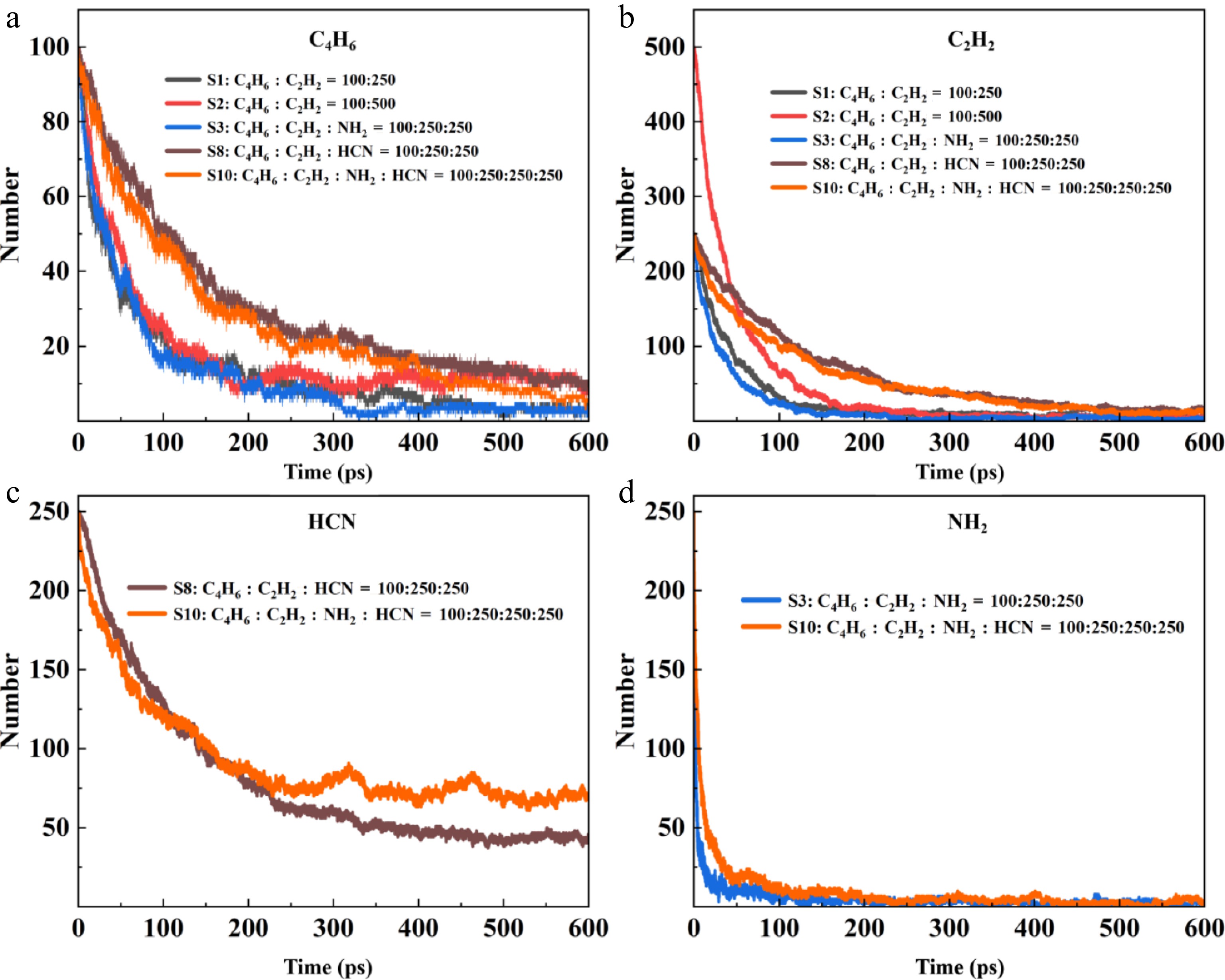

Figure 1 reveals the competitive mechanism of HCN, NH2, and C2H2 for the key carbon source C4H6 by comparing the consumption of reactants.

The consumption of C2H2 is highly synchronized with that of C4H6. C4H6 and C2H2 are more capable of forming the precursors of benzene rings. The consumption rate of C4H6 is closely related to the content of nitrogenous substances such as HCN. CN is a strong electrophilic radical[29], while the conjugated double bond structure of C4H6 is rich in electrons, and the reaction barriers are extremely low. Compared to the first three systems, HCN in the S8 and S10 systems inhibits the consumption of C4H6, and the HCN decomposition product, CN radical, inserts into C4H6 to form cyanobutadiene. HCN diverts the carbon flow that could have been used as the precursor of the benzene ring. At the same time, HCN captures the H atom in the system through HCN + H = CN + H2, inhibiting the dehydrogenation activation of C4H6. This significantly slows down the entire carbon utilization process. The comparison between the S8 and S10 systems in Fig. 1c, d shows that NH2, in addition to not being affected by HCN, also reduces the total consumption of HCN. NH2 also reacts with CN or other active intermediates derived from HCN, converting them into other nitrogen-containing products, thereby preventing CN from attacking C4H6 or reducing its concentration. This also indirectly reduces the consumption of C4H6 and the net consumption rate of HCN. The rate-limiting of HCN for C4H6 and C2H2, as well as the rate-limiting of NH2 for HCN, jointly construct a carbon source competition mechanism dominated by nitrogen-containing species. The inhibition and dynamic consumption between HCN and NH2 are the core reasons determining the carbon source utilization efficiency.

C2H2 undergoes a cyclization reaction to form C6H6, which is the carbon-hydrogen compound that consumes the most C4H6. C2H2 and C4H6 directly form the precursor of the benzene ring through a cooperative cyclization reaction. The reaction barrier is low (about 25–40 kJ/mol), and no free radicals are required[30], resulting in a fast rate and high selectivity. This is an efficient and low-barrier path in the carbon-hydrogen system. However, in the nitrogen-containing system, the reaction of HCN and NH2 with C4H6 is significantly more intense than that of C2H2. The essence is that nitrogen-containing species react with C4H6 through a low-barrier free radical pathway, while destroying the hydrogen radical environment required for the formation of the benzene ring by C2H2-C4H6. Eventually, the carbon source is shifted from aromatic hydrocarbons to nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds.

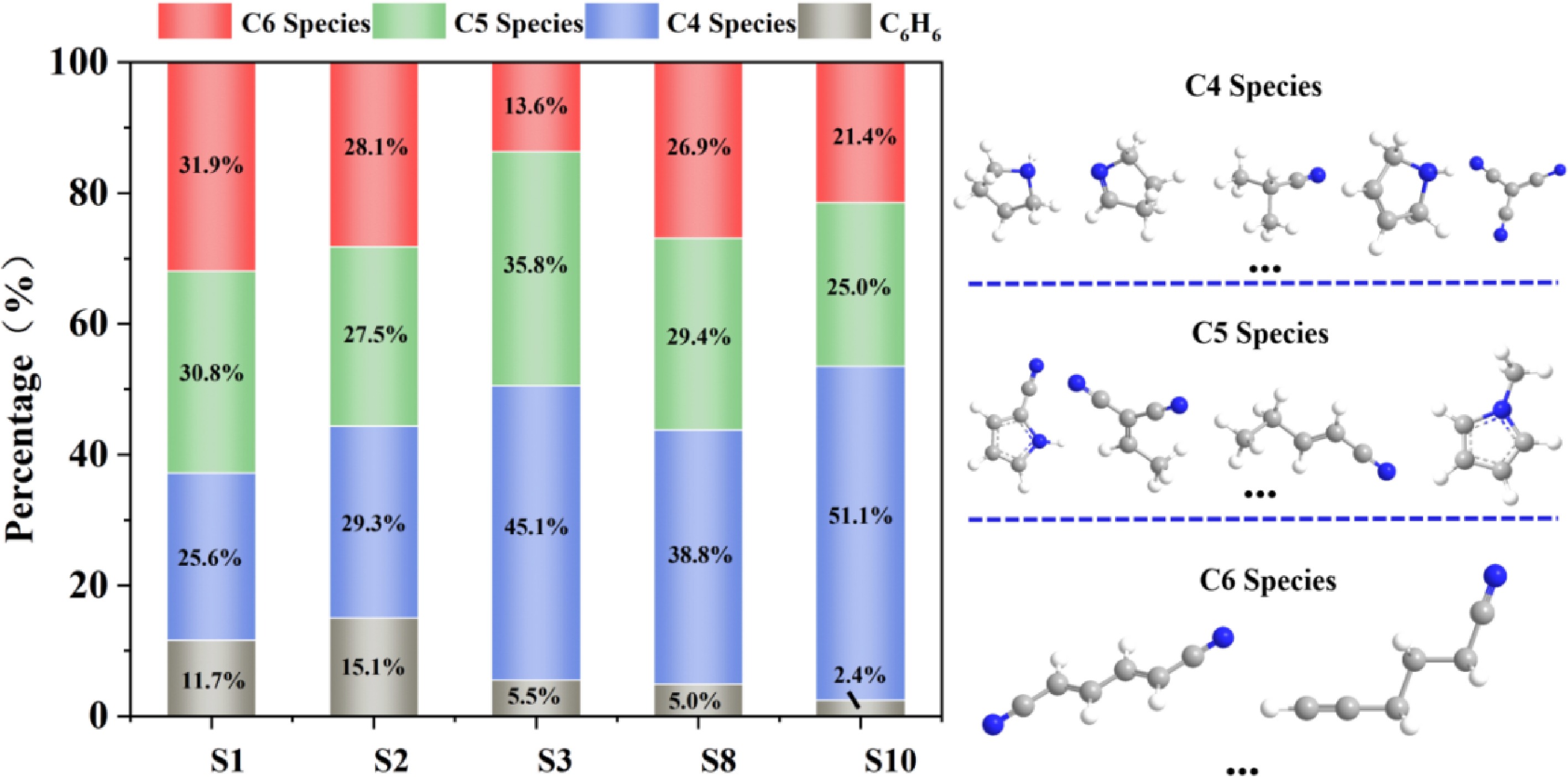

As shown in Fig. 2, compared with S1 and S2, the C6H6 formation in the S3, S8, and S10 systems containing HCN and NH2 is significantly reduced. HCN possesses the characteristics of high selectivity, high reaction rate, low-energy barrier, and efficient utilization of nitrogen atoms. This makes it the main intermediate product that consumes C4H6 as a carbon source. HCN can consume a large amount of C4H6 that could be used to form the benzene ring in a short time. At the same time, NH2, as an extremely active free radical, also consumes a large amount of C4H6. This also confirms the main regulatory role of NH2 and HCN in C4H6 in Fig. 1. Meanwhile, in the nitrogen-containing system, the C4 species increase, which provides favorable conditions for the formation of pyrrolo-pyridine.

Figure 2.

Proportions of typical cyclic structures (NPAHs, cycloalkanes) in S1, S2, S3, S8, and S10.

In the S3 system with NH2 added, the C6 species decrease, and the C5 species are generated instead. In the S8 and S10 systems containing HCN, more C4 species are formed. This is because the NH2 radical reaction is rapid and direct, while the HCN molecule requires a higher activation energy. The essence of NH2 is to release high-activity nitrogen radicals (NH or N) instantly, converting C4H6 directly into a C4N radical intermediate, and then rapidly constructing C5 species through efficient single-carbon addition or cyclization. However, the reaction rate of HCN is not as fast as NH2. Therefore, C4 species are predominant in the system. Even though HCN has a lag, the CN free radicals produced by HCN can consume a large amount of C4H6 that could be used to form the benzene ring in a short time. NH2 radicals are also highly reactive, but they are both free radicals and nucleophiles. This leads to the diversity of their reaction pathways. NH2 can also add to C4H6 to form an amino butadiene radical. This is a main reaction similar to the CN pathway and an important step in constructing NPAHs. NH2 is more likely to seize the hydrogen atom from other molecules in the system (such as H2, H2O, CH4, even C4H6 itself) (NH2 + RH = NH3 + R). This is a reaction with a generally lower energy barrier and a faster rate[31−34]. NH2 can undergo a self-combination reaction to form dinitrogen (N2H4) or disintegrate to generate NH3 and N2H2, and the nitrogen atoms of these species are basically unable to effectively enter the carbon chain to form heterocycles. Due to numerous low-barrier side reaction channels, the proportion of NH2 used for addition to C4H6 in the system is significantly lower than that of CN used for addition to C4H6. A large amount of NH2 is used to generate ammonia or other non-target products.

In the competition for the key carbon source C4H6, HCN can consume C4H6 more quickly, more abundantly, and with higher selectivity than NH2 through its efficient CN free radical pathway. Meanwhile, due to its numerous side reactions (especially the hydrogenation process to form NH3), the nitrogen atom utilization rate of NH2 is low[35,36]. More investment is required to achieve a similar consumption effect. Therefore, NH2 is significantly less competitive than HCN in terms of carbon source. Additionally, the side reactions of NH2 more severely disrupt the hydrogen radical environment necessary for the formation of the benzene ring. These two factors make the regulatory effect of HCN on C4H6 in nitrogen-containing systems more significant than that of NH2. Thus, it transfers the carbon flow from aromatic hydrocarbons to NPAHs.

The difference between HCN and NH2 in the formation ofpyridine and pyrrole

-

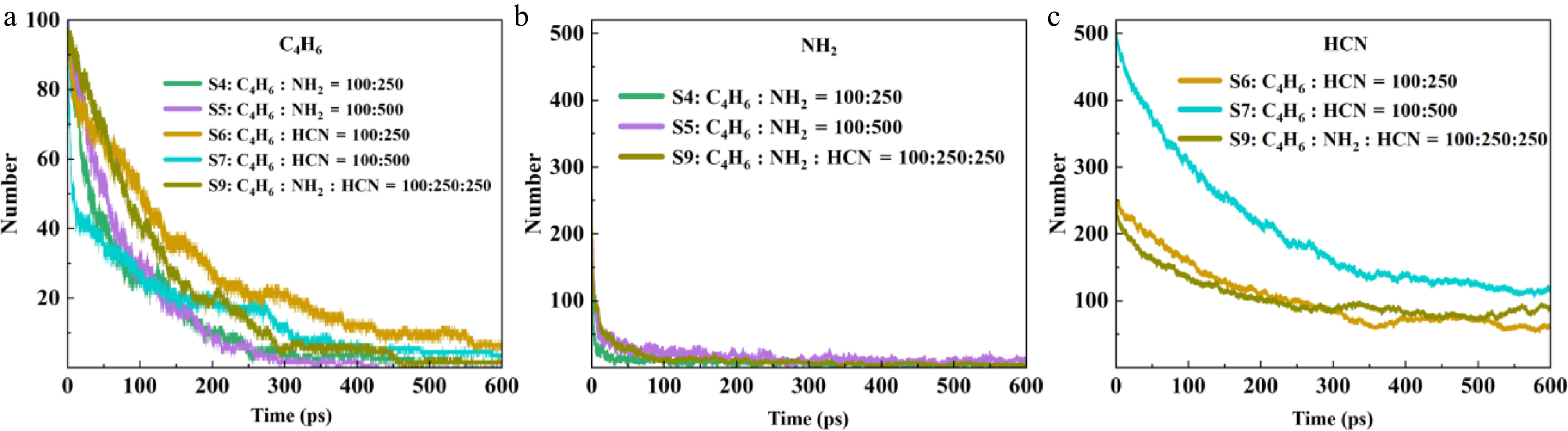

HCN and NH2 mainly generate pyrrole and pyridine through competition with C2H2. Figure 3 shows the consumption of reactants during this process.

In a system without competition from C2H2, an increase in HCN concentration directly accelerates the consumption of C4H6, while changes in NH2 concentration have almost no effect on the consumption of the carbon source. HCN stably combines with C4H6 through a concentration-dependent addition pathway, and this addition reaction preferentially forms stable NPAHs precursors such as cyanobutadiene. These intermediates are highly resistant to decomposition because the cyano group has a stabilizing effect. They can also undergo subsequent efficient intramolecular cyclization reactions to form pyridine, and they exhibit high selectivity. Therefore, the reaction efficiency of HCN naturally and significantly increases with the increase in its concentration. The reaction characteristics of NH2 are different from the stable molecular structure of HCN. In the initial stage of the reaction, NH2 will rapidly undergo ultrafast decomposition and be completely consumed to generate highly active nitrogen atom groups (NH and N). However, in an initially free radical-poor environment, there are insufficient H atoms, other free radicals, or stable molecules, and these highly reactive nitrogen radicals cannot react. They recombine into N2, H2N-NH2, etc[11,35,36]. This results in the inability of nitrogen atoms to effectively insert into the C4H6 skeleton, leading to extremely low nitrogen source utilization. Even if the NH2 concentration is significantly increased, its consumption of C4H6 is almost unaffected. Even though certain nitrogen-hydrogen compounds can add C4H6 to form substances such as C4H6NH, these substances are usually very unstable and prone to reactions such as dehydrogenation and cyclization. This results in the formation of C4-type substances, making it difficult for them to effectively accumulate and form pyrrole rings[37,38]. This makes the generation path of pyrrole itself very fragile and inefficient.

In a system where HCN and NH2 coexist, the reactive nitrogen radicals generated by the decomposition of NH2 participate in the reaction of HCN through N + HCN = CN + NH, indirectly promoting the generation of CN radicals. At this time, NH2 essentially promotes the pyridine generation path of HCN, and the generation of pyrrole formed by NH2 is further inhibited.

There are essential path differences when HCN and NH2 react with C4H6 to form NPAHs compounds: HCN forms stable intermediates through CN addition and undergoes efficient stabilization and directional generation of pyridine through ring formation. It has a highly concentration-dependent process and high efficiency. Although NH2 tends to form pyrrole, the reactive nitrogen radicals generated by its ultra-fast decomposition are difficult to effectively insert into the carbon chain in an unfavorable free radical environment. The formed pyrrole precursors (C4H6NH, etc.) are extremely unstable, and when coexisting with HCN, their path is strongly inhibited, and even their decomposition products can be utilized by the HCN path.

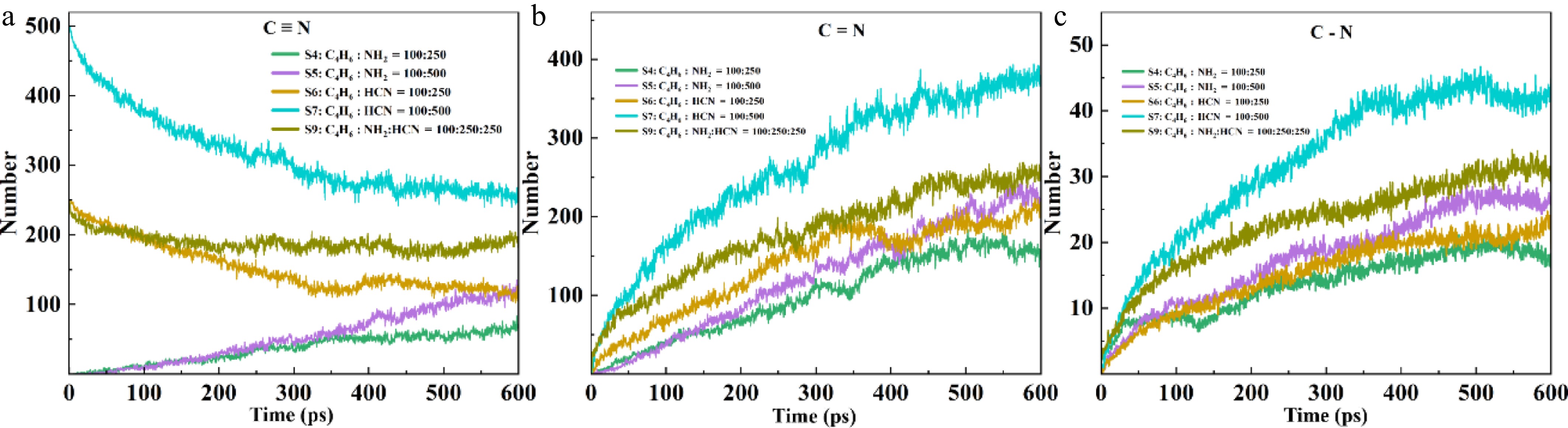

The carbon-nitrogen triple bond is an important source of carbon-nitrogen double bonds and single bonds. The number of C−N bonds in the important system is presented in Fig. 4.

CH2CHCHCHCN, as an intermediate in the formation of pyrrole and pyridine, can illustrate the tendency of HCN and NH2 in the formation of pyrrole and pyridine. CH2CHCHCHCN contains a C−N single bond (pyrrole ring cornerstone) and a C=C double bond, and can efficiently generate pyrrole through intramolecular cyclization; HCN can also rapidly construct pyridine rings through direct cyclization, dehydration of imine (C=N) intermediates, as its C≡N bond can synchronously drive the formation of C=N double bonds, with a short pathway and no redundant steps. On the contrary, as a primary intermediate, the decomposition of NH2 radicals mainly produces NH/N radicals and active H atoms. The active H of NH2 decomposition efficiently acts on the HCN to pyrrole pathway, forming a chain amplification effect; And its other product, NH, although beneficial for pyridine formation, is almost impossible to independently construct pyridine rings due to the significant consumption of side reactions.

Figure 4 shows that HCN has a significant advantage in driving the formation of nitrogen heterocycles such as pyrrole and pyridine. The core mechanism lies in the efficient directional conversion of the carbon-nitrogen triple bond (C≡N): the consumption trend of the C≡N bond in HCN is strictly synchronized with the formation of C−N single bonds and C=N double bonds in the system. Because this bond can be attacked by free radicals and split into highly active CN radicals, directly forming cyanobutadiene with C4H6, this intermediate serves as the direct precursor of pyrrole. This conversion realizes the directional conversion of bond levels from triple bonds to single bonds, with a clear, direct, and efficient conversion path and minimal loss[39].

In contrast, NH2 undergoes more side reactions due to its ultra-fast decomposition, generating NH and N radicals. For example, it generates NH3, which cannot effectively form C−N bonds. Its small amount of imine intermediates (C=N) still needs to undergo multiple steps of dehydration and dehydrogenation to be converted into pyridine, with an efficiency much lower than the direct insertion path of CN by HCN. HCN, with its directional conversion ability of the C≡N bond and chain amplification effect, becomes the core nitrogen source for the construction of nitrogen heterocycles and dominates the efficient generation of pyridine; while NH2 is limited by the dispersed pathways and inefficient bond level transfer, and only contributes to the pyridine pathway indirectly through HCN, unable to independently compete for carbon sources. The C−N single bond is the foundation of the pyrrole ring and an important driving force in the formation of the pyridine ring. It is also a key intermediate carrier connecting the triple-bonded nitrogen source and stabilizing the NPAHs. The single bond is the dynamic precursor of the double bond. Its efficient generation and directional transformation directly determine the synthesis efficiency of pyrrole and pyridine. The consistency in the trend between the C−N single bond and the double bond is essentially a direct manifestation of the directional and coordinated transformation of the C≡N triple bond into low-bond-level products, reflecting the intrinsic correlation of bond-level evolution in the formation of NPAHs. After adding NH2 to HCN, the number of C−N single bonds in the system significantly increases. NH2 generates active H through cleavage, significantly promoting the cleavage of HCN into CN, thereby amplifying the generation path centered on the C−N single bond in a chain-like manner, ultimately leading to a significant increase in the number of C−N single bonds in the system. This confirms that although NH2 is not an efficient independent nitrogen source, it can indirectly strengthen the construction of pyrrole/pyridine precursors by assisting in the catalytic cycle of the bond-level transformation of HCN. As shown in the figure, the consumption of the C≡N triple bond simultaneously drives the formation of C−N single bonds and C=N double bonds in the system. The core of the HCN pathway is the efficient directional transformation of the C≡N triple bond. When the CN radical inserts into C4H6 to form cyanobutadiene (CH2CHCHCH2 + C≡N = CH2CHCHCH2C≡N = CH2CHCHCHC≡N + H), this intermediate contains both the C=C double bond (from butadiene) and the C−N single bond formed by the transformation of C≡N. During subsequent cyclization to form pyrrole, this C−N single bond will further participate in ring formation. As direct or indirect products of the triple bond transformation, the generation rates of single bonds and double bonds are driven by the source of C≡N consumption, thus showing a trend consistency in kinetics[40].

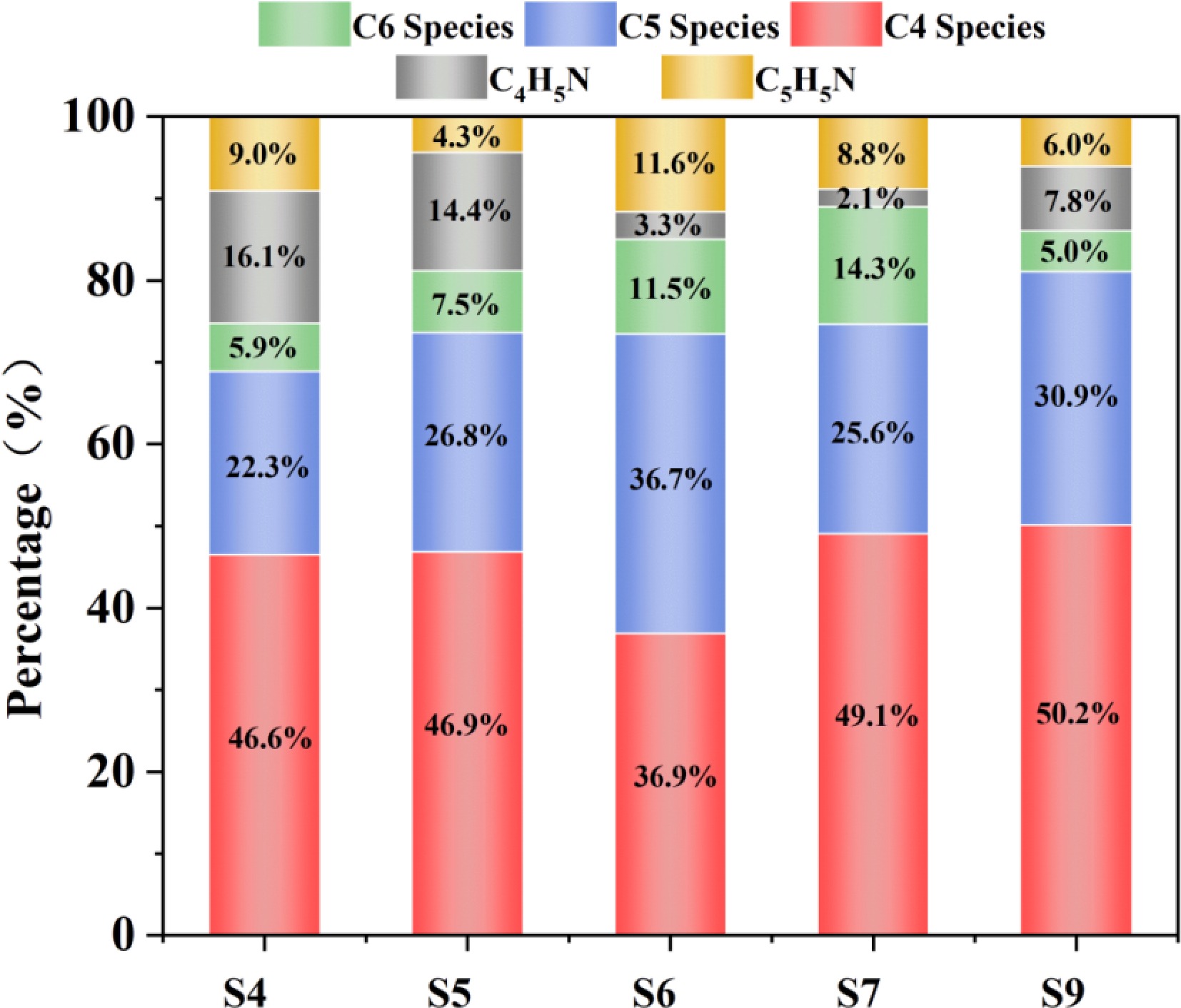

Based on the product distribution analysis of the S4–S9 system in Fig. 5, HCN plays an absolutely dominant role in the formation of pyridine, while NH2 can directly generate pyrrole but with low efficiency. Moreover, HCN significantly inhibits the cyclization path of NH2[41]. The competitive essence lies in the fundamental difference between the nitrogen atom insertion mechanism and the stability of the intermediate: in the pure NH2 system (S4 or S5), the synchronous accumulation of C4H5N and C4 species occurs because the imine intermediate (C4H6NH) formed by the attack of NH radicals on C4H6 is extremely unstable, and some directly undergo dehydrogenation to form pyrrole, and more decompose into C4 species. This is the core evidence for the inefficiency of this path. The C4 species are derivatives, such as unreacted C4H6, dehydrogenated C4H5 radicals, or other C4 molecules generated by cracking/recombination (such as butyne, vinylacetylene). Their accumulation directly proves the fragility and decomposition tendency of the intermediate C4H6NH.

In the HCN-dominated system (S6 or S7), the significant advantage of C5H5N and C5 species is due to the stability and reactivity of the cyanobutadiene formed by CN radicals and C4H6. The cyanide group can be converted into a C=N double bond, combined with CH3 and other single-carbon units to cyclize and form pyridine. Although the cyanide group is stable, under suitable conditions (such as encountering H atoms, other radicals, or high-temperature isomerization), it can relatively easily undergo isomerization or reduction to an imine group. This step converts the stable cyanide group into a reactive C=N double bond, creating the necessary reaction sites for the closure of the ring. The increase in HCN concentration promotes C4 species, which is actually the accumulation of the intermediate cyanobutadiene before the closure; in the coexisting system (S9), the total amount of pyrrole and pyridine is lower than that of the pure NH2 system. The core lies in the fact that HCN competes to consume key radicals, capturing H to generate CN, depriving the decomposition products NH of the ability to complete the conversion from imine to pyridine. The cyanobutadiene occupies the C4H6 reaction site, blocking the NH insertion path;

DFT calculations revealed that the initial energy barrier for the combination of NH2 and C4H6 (0.25 kcal/mol) was lower than the addition energy barrier of HCN (19.6 kcal/mol), indicating that NH2 has stronger initial reactivity. There is also a difference in the energy barrier for the formation of pyrrole and pyridine. The essential reason why HCN is more prone to form pyridine while NH2 tends to form pyrrole is the difference in activation energy of the critical pathway: HCN is directionally converted into an imine intermediate through its C≡N triple bond, and further undergoes low-energy barrier (≤ 30 kcal/mol) cyclization dehydration with the conjugated diene to directly construct the pyridine ring. This pathway has a smooth energy barrier and does not require redundant steps. On the contrary, the NH radicals generated by the decomposition of NH2 can form imines, but the rate-determining step energy barrier for subsequent multi-step dehydration/dehydrogenation to form pyridine is as high as ≥ 50 kcal/mol, which is extremely unfavorable kinetically, making it almost impossible to generate pyridine. For the pyrrole pathway, the active H generated by the decomposition of NH2 can significantly catalyze the cleavage of HCN (reducing the energy barrier from 78 to 32 kcal/mol), efficiently generating CN radicals and combining with butadiene to form cyanobutadiene (energy barrier 20–25 kcal/mol). This low-energy barrier chain amplification mechanism forces NH2 to almost only generate pyrrole[42].

The role of C−N interaction reactions in the formation of pyrrole and pyridine

-

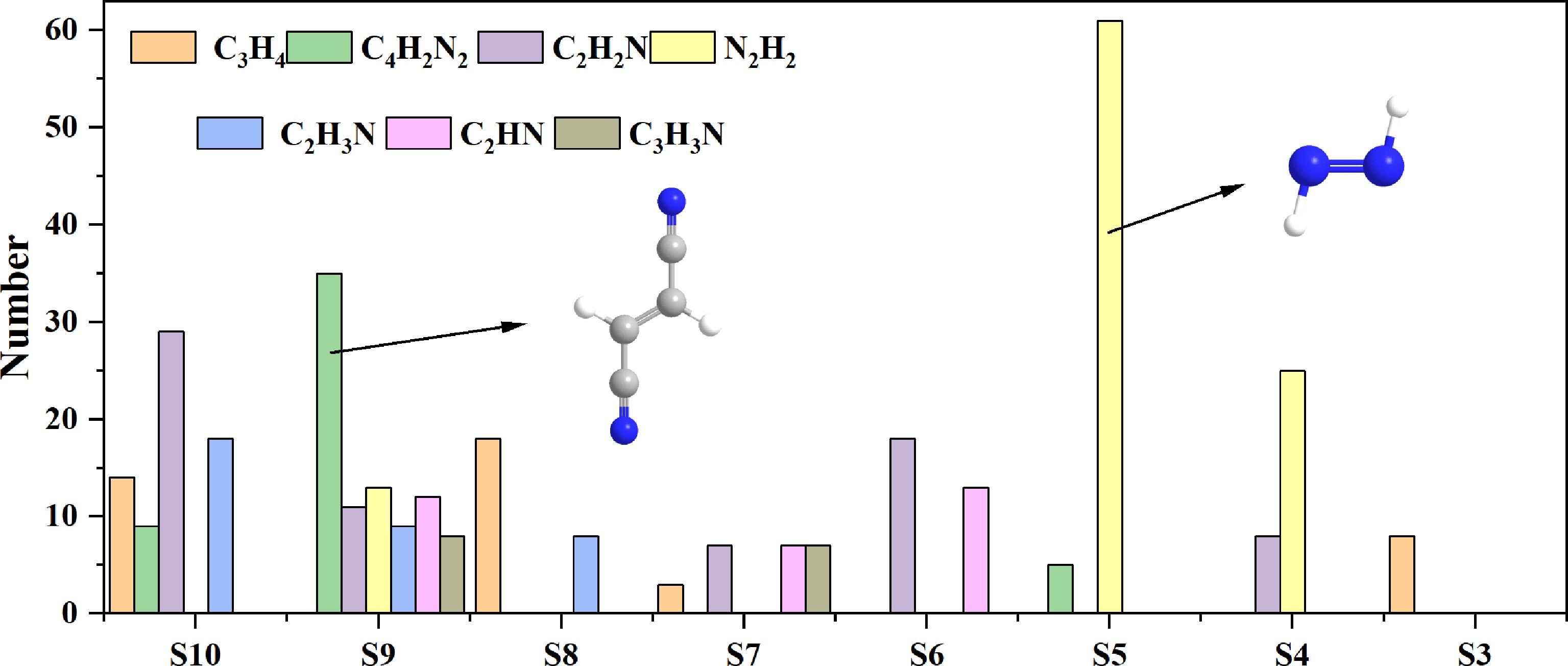

During the formation of pyrrole from pyridine, the key intermediate of C−N interaction determines the generation ability of the products through the efficiency of nitrogen atom transfer and the selectivity of the pathways. By comparing different systems, this study extracted and highlighted the seven substances with the highest content during the most active stage of pyrrole and pyridine formation, and presented them in Fig. 6.

These include some important carbon-nitrogen compounds, such as C4H2N2, C2H2N, and C2H3N. They exist in the widely verified mechanisms such as the Glarborg mechanism[43] and the Okafor mechanism[44]. Additionally, some new C−N species were observed in this paper, including C2HN and C3H3N. These C−N species are worthy of further experimental study and analysis to provide valuable support for further improving the chemical reaction mechanism and adding elementary reactions to describe C−N interactions. The abundance and activity of C4H2N2 and C2H2N are directly related to the formation efficiency of the pyridine ring. C2H2N, as the key radical (CN) derived from HCN, efficiently combines with the acrylonitrile radical C3H3 (CN + C3H3 = C4H3N and its isomers/precursors) and is the initial step of the pyridine pathway. The subsequent formation of C4H2N2 and its ring cyclization rearrangement are the core steps of closing the ring. C2H2N forms cyanobutadiene (NC-CH=CH-CH=CH2 and its isomers) by inserting into C4H6, which is also an important pathway for constructing the precursor of the nitrogen-containing six-membered ring. The efficiency of this path is highly dependent on the availability of HCN and C3 species (especially the C3H3 radical) and the rate of C−N bond formation.

C2H3N and its dehydrogenation product CH2CN are the key driving forces for the formation of pyrrole rings. The source of C2H3N is usually related to the dehydrogenation of nitrogen-containing precursors (such as NH3, amines) or the reaction with C2 species (such as ethylene). The high reactivity of CH2CN enables it to effectively attack unsaturated hydrocarbons, initiating the integration of the carbon skeleton and nitrogen atoms necessary for the formation of the pyrrole pentacyclic ring. The efficiency of this pathway is controlled by the generation rate of nitrogen-containing radicals (especially CH2CN) and their collision and binding efficiency with appropriate hydrocarbon radicals[11,38,45].

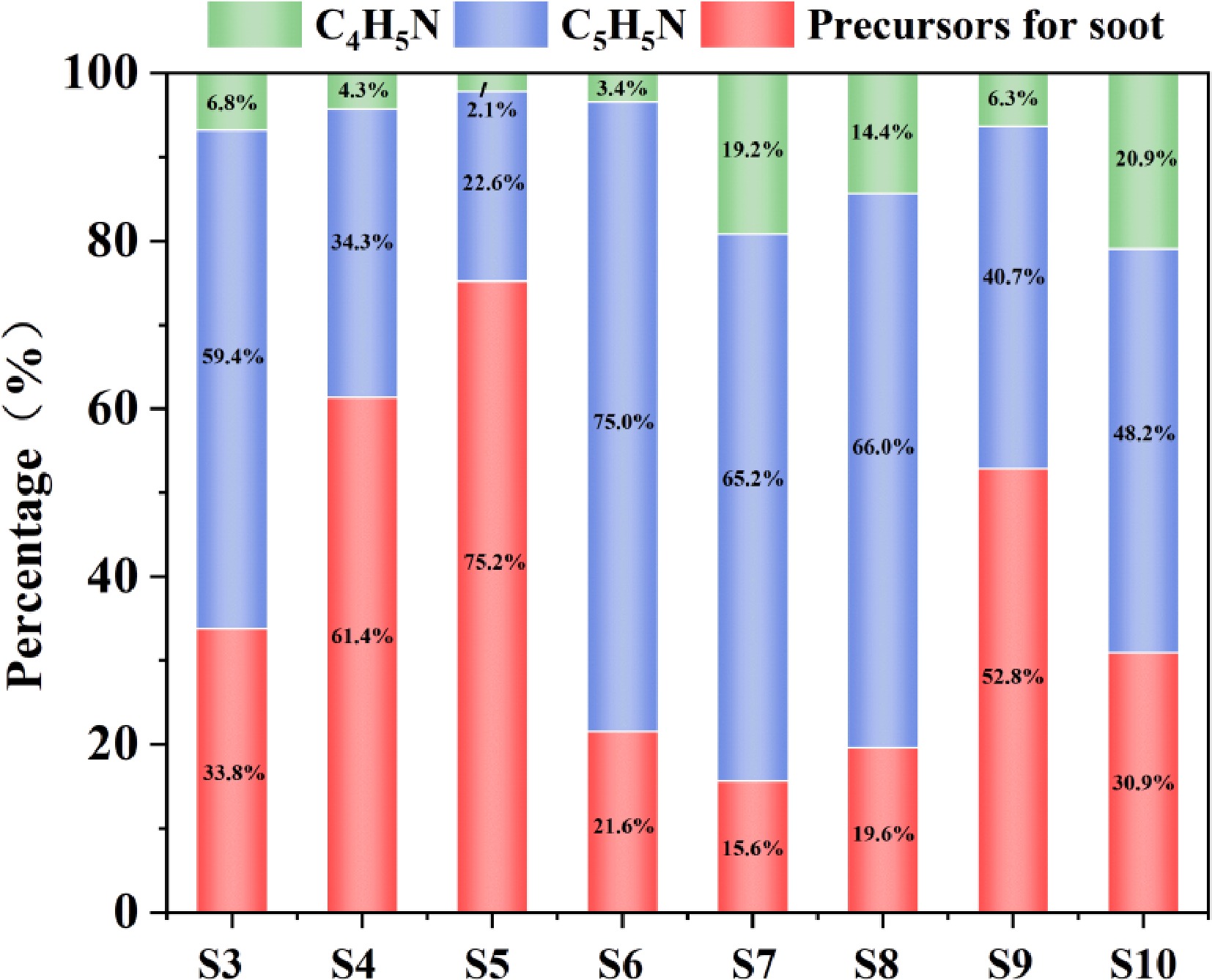

The C−N interaction not only contributes to the formation of pyrrole and pyridine through important intermediate products, but also competes with soot. Figure 7 shows the product situation generated according to the path described in the appendix (except for pyrrole and pyridine). This path produces more ash precursors, indicating that the ash precursors compete with pyrrole and pyridine for nitrogen sources. Comparing typical soot precursors in different systems (C12H8, C14H10, C16H10, C18H10), it was discovered that these precursors also compete for nitrogen sources with pyrrole and pyridine. Compared to other systems, the soot precursors in the NH2 system disperse more nitrogen sources, and more precursors are generated as the concentration of NH2 increases[46−48]. The soot precursors increase with the increase of NH2 concentration, and they are captured by PAH through free radical addition reactions. This process consumes the nitrogen radicals that could be used for the formation of pyrrole and pyridine, resulting in the flow of nitrogen atoms to soot rather than NPAHs. In the HCN systems S6 and S7, there are fewer soot precursors, and CN efficiently generates pyridine in a directionally controlled manner, with high nitrogen atom utilization. The soot precursors are very rare in the HCN system. The nitrogen sources are mainly used to form pyrrolo-pyridine, and CN in the HCN path directly inserts C4H6 to form cyanobutadiene, with a low barrier for closing the ring (85 kJ/mol), and the nitrogen atoms are quickly locked in the pyridine path, reducing the chance of free CN being captured by PAH.

Comparing S4 and S9, it was found that when NH2 and HCN coexist, HCN takes the dominant position, significantly reducing the competitive effect of soot precursors on pyrrolo-pyridine. The soot precursors in S9 are less than those in S4, indicating that in the coexisting system, HCN consumes the NH generated from the decomposition of NH2, blocking its path to soot. Comparing S3 and S4 also shows this phenomenon, indicating that C2H2 in the system containing NH2 will intensify the competitive effect of soot precursors on pyrrolo-pyridine, but by comparing S6 and S8, even after adding C2H2 to the HCN system, the soot precursors do not show a significant decrease. In the NH2 system (S3/S4), C2H2 provides a large number of free radicals (H or CH3), but it exacerbates the dispersion of nitrogen atoms. This is because the imine intermediate (C4H6NH) derived from C2H2 has poor stability, and the radicals derived from C2H2 accelerate its decomposition, releasing NH that is more easily captured by PAH. In the HCN system (S6/S8), the soot precursors do not decrease after adding C2H2, because the CN in the HCN path is protected by the cyanobutadiene intermediate, and it does not react with PAH; the H consumed by C2H2 can be replenished by the decomposition of NH2, but the HCN path itself does not rely on external free radicals. The S6 condition is the one that generates the most pyridine, again confirming the conclusion in Fig. 7 that HCN is beneficial for the formation of pyridine. According to the previous conclusion, NH2 is relatively important in the formation of pyrrole, but the pyrrole formed by NH2 is easily affected by the competitive effect of precursors.

The core advantage of HCN lies in its ability to confine nitrogen atoms within an efficient ring formation pathway through a low-energy barrier closed path. The generated stable intermediates inhibit the escape of NH, reducing the supply of nitrogen sources from the source to the soot precursors. According to the path analysis, C2HN, as a by-product of the NH2 path (NH + C2H2), consumes 25% of the nitrogen atoms and flows to soot, exacerbating nitrogen loss. C3H3N (acrylonitrile) in the HCN path combines with C2H4 through CN to form pyridine precursors.

-

This study aims to investigate the effects of HCN and NH2 on the NPAHs formation in the ammonia-hydrocarbon blended combustion. The competitive mechanisms between nitrogen and carbon sources were explored, and the role of C−N interaction in regulating the formation pathways of NPAHs was elucidated by tracking key intermediates and bond sequence evolution. Based on the ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations, ten system structures were constructed using C4H6, C2H2, NH2, and HCN. The main findings are summarized as follows:

(1) HCN is more prone to seizing carbon sources than NH2. HCN rapidly reacts with C4H6 through the easily generated CN radical to form cyanobutadiene, consuming most of the C4H6. In contrast, NH2 participates in numerous side reactions and readily undergoes hydrogen abstraction reactions with species such as H2 and CH4, which diminishes its capacity to form pyrrole and pyridine.

(2) HCN is easier to form pyridine, while NH2 tends to generate pyrrole. The CN radical derived from HCN decomposition combines with C4H6 to form the stable intermediate cyanobutadiene, which undergoes efficient cyclization to produce pyridine. Although NH2 can directly participate in pyrrole formation, the intermediate C4H6NH is highly unstable and tends to decompose into C4 species. Furthermore, in the presence of HCN, competitive consumption of C4H6 occurs, thereby reducing the available reaction substrate for NH2 and inhibiting pyrrole formation.

(3) C−N species and C−N interactions promote the formation of soot precursors, ultimately leading to a decrease in the yield of pyrrole and pyridine. C2HN and C3H3N are important C−N species in the optimal pathways for pyrrole and pyridine formation. In these pathways, NH2 radicals generated from NH2 decomposition are easily captured by PAHs, leading to the formation of soot precursors while depleting the nitrogen atoms that would otherwise contribute to nitrogen heterocycles formation. HCN blocks the side reactions of NH2 by consuming H. Consequently, HCN suppresses the formation of soot precursors and enhances the yield of nitrogen-containing heterocycles.

This work was supported by Yunnan Fundamental Research Project (Grant No. 202301BE070001-043), and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2023QE215).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Gao Y; formal analysis: Gao Y, Wang S; investigation: Gao Y, Wang S, Zhao H; writing original draft preparation: Gao Y; writing, review & editing: Li Y, Duan Y, Jiang H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Gao Y, Wang S, Duan Y, Zhao H, Jiang H, et al. 2025. Effects of HCN and NH2 on the formation of nitrogen-containing PAHs during ammonia-hydrocarbon blended combustion: a ReaxFF molecular dynamics study. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e024 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0022

Effects of HCN and NH2 on the formation of nitrogen-containing PAHs during ammonia-hydrocarbon blended combustion: a ReaxFF molecular dynamics study

- Received: 29 June 2025

- Revised: 22 August 2025

- Accepted: 16 September 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: During ammonia-hydrocarbon blended combustion, nitrogen-containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (NPAHs) such as pyrrole and pyridine emerge as critical pollutants due to their high toxicity and potent carcinogenicity. C4H6, an important pyrolysis intermediate in the co-combustion of ammonia and hydrocarbons, readily participates in reactions with HCN and NH2 to form NPAHs. However, the mechanisms through which HCN and NH2 interact with C4H6 to form the incipient nitrogen-containing aromatic rings, as well as the effects of carbon-nitrogen (C–N) interactions on the selectivity of reaction pathways, remain poorly understood. The current limitations in understanding the formation mechanisms of NPAHs hinder the advancement of clean ammonia combustion technologies. In this study, ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations were employed to investigate the competitive roles of HCN and NH2 in NPAH formation. Systems with varying concentrations of HCN and NH2, and mixtures containing both species, were systematically examined. The results indicate that HCN is more favorable for the formation of NPAHs compared to NH2 and exhibits a strong tendency to form pyridine. In contrast, NH2 preferentially participates in side reactions that generate abundant other substances, thereby limiting its contribution to pyrrole formation. Carbon-nitrogen interactions play a crucial role not only in the formation of NPAHs but also in the generation of soot precursors. These insights provide theoretical guidance for the targeted reduction of nitrogen content in ammonia-blended fuels.

-

Key words:

- Ammonia blending combustion /

- NPAHs /

- ReaxFF MD simulation /

- Pyrrole /

- Pyridine