-

Seaweed is macroscopic, multicellular algae that are typically found in marine environments. Their lack of true roots, stems, or leaves sets them apart from higher plants. They range in size from tiny, thread-like filaments to enormous, complex thalli. Seaweeds are classified into three primary groups: Rhodophyta, Phaeophyta, and Chlorophyta[1,2]. In coastal ecosystems, seaweed is the primary producer. The most frequently found seaweeds in Sri Lankan waters are Fucus, Laminaria, Padina, Sargassum, Tubinaria, and Ulva[3].

Endophytes are an endosymbiotic group of microorganisms that reside in the healthy tissues of plants and certain microbes asymptomatically. They are primarily fungi or bacteria[4]. These endophytes form mutualistic relationships with their hosts, providing benefits like increased nutrient absorption, defense against pathogens and herbivores, and stress tolerance[5]. In addition, fungal endophytes have proven to be prolific sources of bioactive natural products with antifungal, antibacterial, anticancer, antiplasmodial, and antioxidant properties[6]. The exploration of fungal endophytes, which inhabit terrestrial plants, has provided numerous biocontrol agents and pharmaceutical agents, stimulating interest in their marine counterparts[5].

Seaweeds provide habitats for a wide variety of endophytic fungi, which produce a range of naturally occurring bioactive compounds[5]. Seaweeds, from different geographical locations, exhibit variation in associated endophytes as well as secondary metabolites produced by them[7]. For example, Aspergillus terreus which inhabits marine red algae Laurencia ceylanica, found on the east coast of Sri Lanka produces β-Glucuronidase inhibiting Butyrolactone[8]. Even though nearly 100 seaweed species have been investigated for endophytic fungi inhabiting them, 75% of them have been investigated from just six locations including the Baltic Sea, Canada, China, India, the North Sea, and the United Kingdom (Table 1). Red algae accounted for the highest number of seaweed species investigated (41), followed by 32 species of brown algae and 19 species of green algae[9]. According to a rarefaction curve plotted by Flewelling et al.[10] based on the results of a study carried out in the Shetland Islands, UK, green algae had the highest diversity of endophytes, whereas brown algae possessed the lowest species diversity. The rarefaction curve extrapolation shows that increased fungal isolate sampling would produce more distinct fungal species from green algae[10]. However, the rarefaction curves reported by Suryanarayanan et al.[11], based on a study carried out on the Tamil Nadu coast, Southern India, contrasted with those obtained for the Shetland Island isolates. According to this study, green algae collected from the Tamil Nadu coast yielded the lowest diversity of endophytic fungal species while brown algae yielded the highest[11]. The observed variations in the quantity, diversity, and identity of the fungal species derived from green algae may be attributed to variations in the algal species collected, the isolation techniques used, or the seasonal, climatic, and geographic differences between the collection sites in Southern India and the UK (Shetland Islands). More research on endophyte diversity within algae from various climatic and geographic settings would aid in further understanding of this trend[11].

Table 1. Summary of seaweed-associated fungal endophytes reported worldwide.

Locality Seaweed species Fungal endophytes Ref. India Sargassum ilicifolium Aspergillus terreus [11] Sargassum wightii Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus terreus, Cladosporium sp., Nigrospora sp., Penicillium sp, [11] Ulva lactuca Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus terreus, Chaetomium sp., Cladosporium sp., Nigrospora sp., Penicillium sp. [11] Ulva fasciata Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus terreus, Chaetomium sp., Curvularia lunata, Paecilomyces sp. [11] Padina tetrastromatica Acremoniella sp., Ascotricha sp., Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus terreus, Chaetomium sp., Monodictys sp., Paecilomyces sp., Penicillium sp., Phialophora sp. [11] Canada Ulva lactuca Penicillium chrysogenum [48] Ulva intestinalis Aspergillus sp. [48] Chondrus crispus Aspergillus sp., Penicillium crustosum [48] Saccharina latissima Aspergillus sp., Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium soppii [48] United Kingdom Ulva intestinalis Bionectria ochroleuca Cordyceps sp., Leptosphaeria sp., Penicillium sp. [10] Ulva lactuca Eurotium sp., Leotiomyceta sp., Penicillium sp., Pseudeurotium bakeri, Stilbella fimetaria [10] Fucus serratus Aspergillus fumigatus Coniothyrium sp., Penicillium sp. 10] Ascophyllum nodosum Aspergillus fumigatus, Cladosporium sp., Dendryphiella salina, Lichtheimia corymbifera [10] Fucus spiralis Penicillium sp. [10] Fucus vesiculosus Alternaria sp., Aspergillus fumigatus, Chalara sp., Coniothyrium sp., Penicillium sp. [10] Ascophyllum nodosum Mycosphaerella ascophylli [10] Chondrus crispus Lautitia danica [10] China Sargassum fusiforme Aspergillus wentii [49] Sargassum horneri Pestalotiopsis sp. [50] Sargassum kjellmanianum Aspergillus ochraceus [42] Sargassum thunbergii Aspergillus versicolor, Eurotium cristatum [51] Ulva pertusa Chaetomium globosum [43,52] Egypt Ulva sp. Penicillium sp. [53] North sea Ulva lactuca Ascochyta salicorniae [54] Even though information is available on fungal endophytes associated with seaweeds in countries like India, Canada, UK, China, and France through extensive research, the existing knowledge about fungal endophytes residing inside seaweeds found in Sri Lanka is very limited. This research is the very first study performed to discover unrevealed fungal endophytes associated with seaweeds found in the southern coastal waters of Sri Lanka. The southern province of Sri Lanka, which is well-known for its rich marine biodiversity and breathtaking coastal landscapes, presents a perfect setting for investigating the biocontrol potential of fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds.

Penicillium species can adjust their metabolism to survive in various environments and are ubiquitous in nature. These are mostly found in food, indoor air, and soil[12]. Penicillium strains have also been isolated as endophytes in a variety of plant species, including Vitis vinifera, Scurrula atropurpurea, Garcinia multiflora, Syzygium zeylanicum, and Stephania kwangsiensis[13]. Endophytic Penicillium has been shown to colonize ecological niches and defend their host plant from a variety of stresses by demonstrating varied biological functions that can be exploited for a broad range of applications, including agricultural, biotechnological, and pharmaceutical applications[14]. Some endophytic Penicillium species have also proven to act as biocatalysts, plant growth promoters, phytoremediators, and enzyme makers[14]. Some endophytic Penicillium strains have shown to be capable of biodegrading a wide range of organic contaminants (phenols, azo dyes, hydrocarbons, medicinal compounds, and so on), as well as having a high potential for wastewater treatment[12]. Aspergillus species can survive in extremely harsh environmental circumstances and are found in a variety of natural habitats such as plants, soil, air, water sediments, and marine invertebrates[15]. Endophytic Aspergillus strains have been shown to be colonizing plants, mosses, ferns, liverworts, and hornworts[16]. Endophytic Aspergillus strains have a rich chemical diversity that includes alkaloids, butenolides, cytochalasins, diphenyl ether, phenalenones, sterols, pyrones, terpenoids, and xanthones, which exhibit a variety of bioactivities such as antibacterial, antifungal, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic activities[17]. Many studies have reported endophytes belonging to the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium as the most commonly isolated fungal endophytes from marine macroalgae[5,11,18−20].

Fungal infections in crops result in significant losses in agricultural production by lowering crop quality and yield[21−23]. The standard approaches for controlling the adverse effects of these fungal infections have traditionally included the use of synthetic fungicides and physical treatments[24]. However, the urgent need to decrease the use of hazardous chemicals has prompted research into eco-friendly, sustainable, and long-lasting preventive strategies. Many fungal endophytes can produce bioactive substances with antifungal properties[25−28]. Therefore, these fungal endophytes have drawn a lot of attention in the search for sustainable biocontrol agents against phytopathogenic fungi[29−31].

In recent times, studies of endophytic fungi on plant hosts and their potential secondary metabolites have received a lot of attention. However, the endophytic fungi and their potential metabolites on seaweed hosts are still delimited, especially in Sri Lanka. Hence this study aims to discover endophytic fungi residing inside seaweed hosts found in the southern coastal waters of Sri Lanka and to investigate their potential antifungal activity against selected phytopathogens.

-

Seaweeds: Ulva lactuca, Sargassum ilicifolium, and Padina antillarum were collected from three different locations in the southern province (Madiha Beach, Thalpe Beach, and Koggala Beach) of Sri Lanka during the northeast-monsoon season of 2023 and 2024. The collected samples were gently transferred into a polythene zip-lock sample cover containing seawater. The collected samples were taken to the laboratory, and then seaweed was gently washed in sterile seawater for two to three minutes to remove dust or other contaminants on the surface. Then, the samples were gently pressed with sterile tissue paper to remove wetness and moisture from the samples. All endophyte isolates were obtained following a modified isolation method[4,32]. Seaweed samples were cut into fragments (1 cm × 1 cm) using a sterilized scalpel and were washed three times with sterile seawater before proceeding to surface sterilization. Then, these pieces were treated in 70% ethanol (v/v) for one minute, 2% sodium hypochlorite (v/v) for five minutes, and again in 70% ethanol for 30–35 s. Then, they were rinsed in sterile distilled water three times (three minutes each). Eventually, surface sterilized pieces of seaweed were blotted dry on sterilized filter papers.

Surface-sterilized seaweed samples were placed carefully on the surface of Petri plates containing potato dextrose agar (PDA) (four pieces per petri plate) using sterilized forceps. Six replicates were prepared for each species (Ulva lactuca, Sargassum ilicifolium, and Padina antillarum) collected from each location. The plates were incubated at room temperature (28 °C) in an inverted position until the hyphal growth of fungi was observed. Pure cultures were maintained following a series of subcultures of isolated species using the fungal tip isolation method. Growth rates and colony characteristics such as colony colour, growth pattern, texture, and elevation were determined after two weeks. Isolated strains were initially assigned to mycelial morphotypes and further subjected to molecular characterization. Fungal isolates were deposited in the Culture Collection of the Genetics and Molecular Biology Unit (GBMUCC), University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka.

DNA extraction, PCR, and ITS-rDNA sequencing

-

The genomic DNA of each fungal strain was extracted following the modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method described by Thambugala et al.[33]. PCR amplification was performed with a total volume of 25 μL of PCR mixtures, containing 8.5–9.5 μL ddH2O, 12.5 μL 2 × PCR Master Mix, 1–2 μL of DNA template, 1 μL of forward primer, and 1 μL of reverse primer. The internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) was amplified using ITS4 and ITS5 primer pairs and the conditions are specified in Thambugala et al.[33]. After PCR amplification, 1% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide was performed. Successful PCR products were taken to 'Genelabs Medical' , Sri Lanka for purification and ITS sequencing. Sequence results were analyzed with the GenBank NCBI database using the BLASTn search to preliminarily identify each fungal endophyte to generic level. Based on the closest and most reliable matches resulting from the BLASTn search, the identity of the fungal isolates was determined. Newly produced sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table 2).

Table 2. Preliminary identification of endophytic fungi isolated from seaweeds based on ITS nucleotide BLAST searches in GenBank.

BLAST search results Culture collection code GenBank accession no. of the closest match Closest match Identity (%) Query coverage (%) GenBank accession no. GMBUCC 24–006 NR_171584 Aspergillus urmiensis 98.1 98 PP818902 GMBUCC 24–007 NR_121481 Aspergillus fumigatus 99.3 97 PP818903 GMBUCC 24–008 NR_121481 Aspergillus fumigatus 98.8 97 PP818904 GMBUCC 24–009 NR_121481 Aspergillus fumigatus 99.5 97 PP818905 GMBUCC 24–010 NR_158822 Penicillium cataractarum 99.1 94 PP818906 GMBUCC 24–011 NR_158822 Penicillium cataractarum 98.7 94 PP818907 GMBUCC 24–012 NR_121481 Aspergillus fumigatus 99.8 98 PP818908 GMBUCC 24–013 NR_173418 Aspergillus heldtiae 98.1 97 PP818909 Testing for in-vitro antifungal activity of isolated fungal endophytes

-

Phytopathogenic fungi: Colletotrichum siamense (UKCC 24–012) and Neopestalotiopsis cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) were obtained from the culture collection of the University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka (UKBC) and the Culture Collection of the Genetics and Molecular Biology Unit (GBMUCC), University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka respectively (Asfa et al. in prep., Wijayarathna et al. in prep.). Endophytic fungal strains isolated from P. antillarum, S. ilicifolium, and U. lactuca were tested for their antifungal activity against C. siamense (UKCC 24–012) and N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) using the dual culture technique.

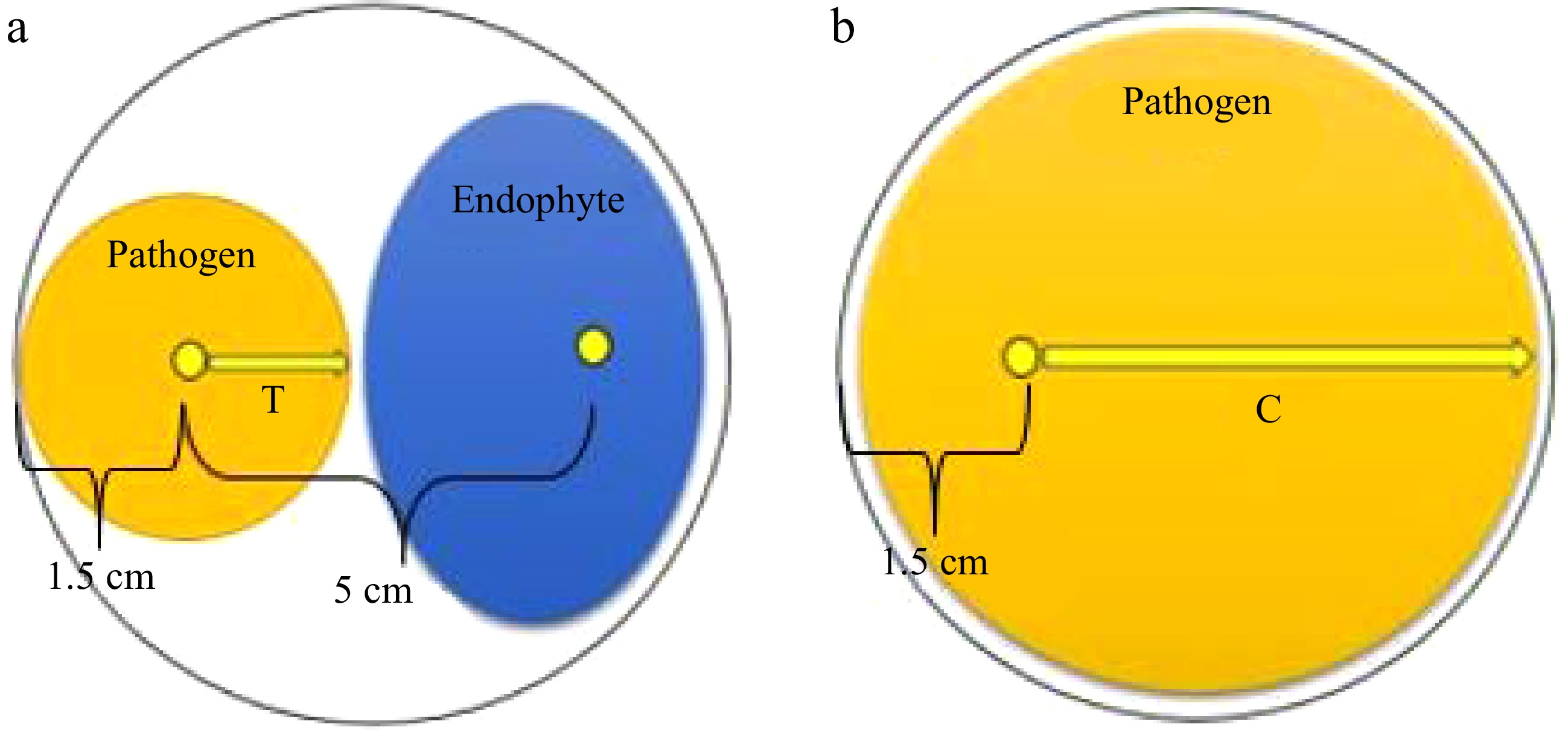

Petri plates with a diameter of 9 cm were used to prepare the dual culture assays. A mycelial agar plug (5 mm diameter) of the selected fungal phytopathogen was placed 1.5 cm from the edge of a Petri dish containing PDA (Fig. 1a). Then, a 5 mm diameter mycelial agar plug of the filamentous fungal isolate was positioned (50 ± 5 mm) away from the phytopathogen inoculum to establish a dual culture (Fig. 1a). Dual culture plates were prepared for each fungal endophyte against each pathogen, with triplicates included for each pathogen-antagonist combination. Triplicate plates inoculated solely with fungal phytopathogens served as control groups (Fig. 1b). The cultures were incubated at 28 °C for 10 d. Endophytic fungi that formed an inhibition zone against fungal phytopathogens in the dual cultures were classified as antagonistic fungi[34].

Figure 1.

Dual culture technique for testing the biocontrol potential of endophytic fungi against fungal phytopathogens. (a) Dual culture plate. (b) Control plate.

The biocontrol efficiency of different endophytic fungal isolates was compared by calculating the percentage of linear growth inhibition by fungal endophytes against Colletotrichum siamense (UKCC 24–012) and Neopestalotiopsis cubana (GMBUCC 24–001).

The percentage of linear growth inhibition (PI) was calculated as follows:

$ \rm{PI}\text{%}=\dfrac{\left(\rm{C}-\rm{T}\right)\times100}{\rm{C}} $ where, PI% = Percent of linear growth inhibition; C = Mean distance of the pathogen growth from the point of inoculation to the margins in the control dish; T = Mean distance of the pathogen growth from the point of inoculation to the colony margins in treated dishes toward the antagonist (fungal endophyte isolate)[34].

Statistical analysis

-

Mean mycelial growth of pathogens was analyzed using R version 4.3.3 for Windows. Obtained data were analyzed by the one-way ANOVA with LSD and Duncan tests at the significant level p < 0.05. All values were given as means of three replicates + standard deviation. Visual bar charts were also created using R.

-

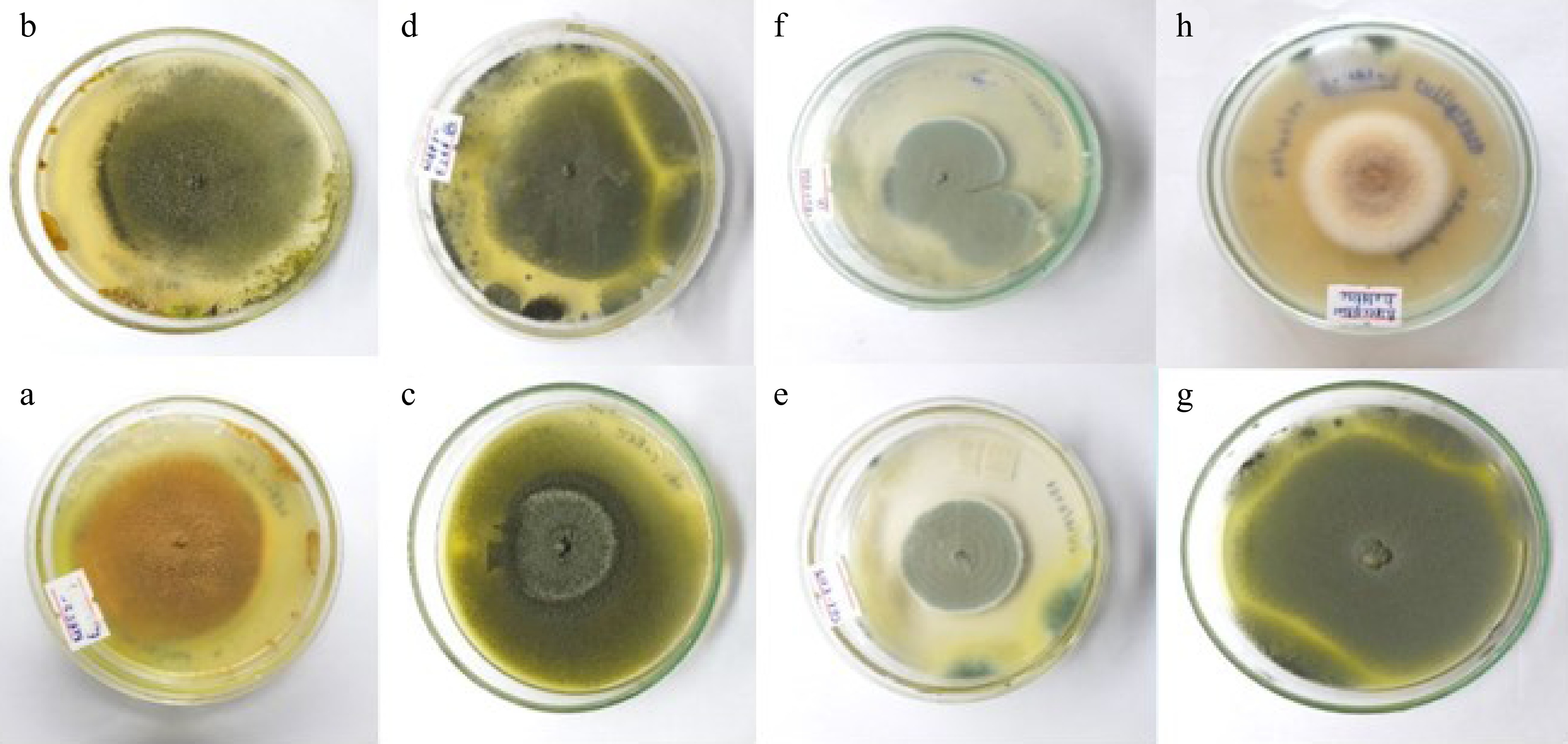

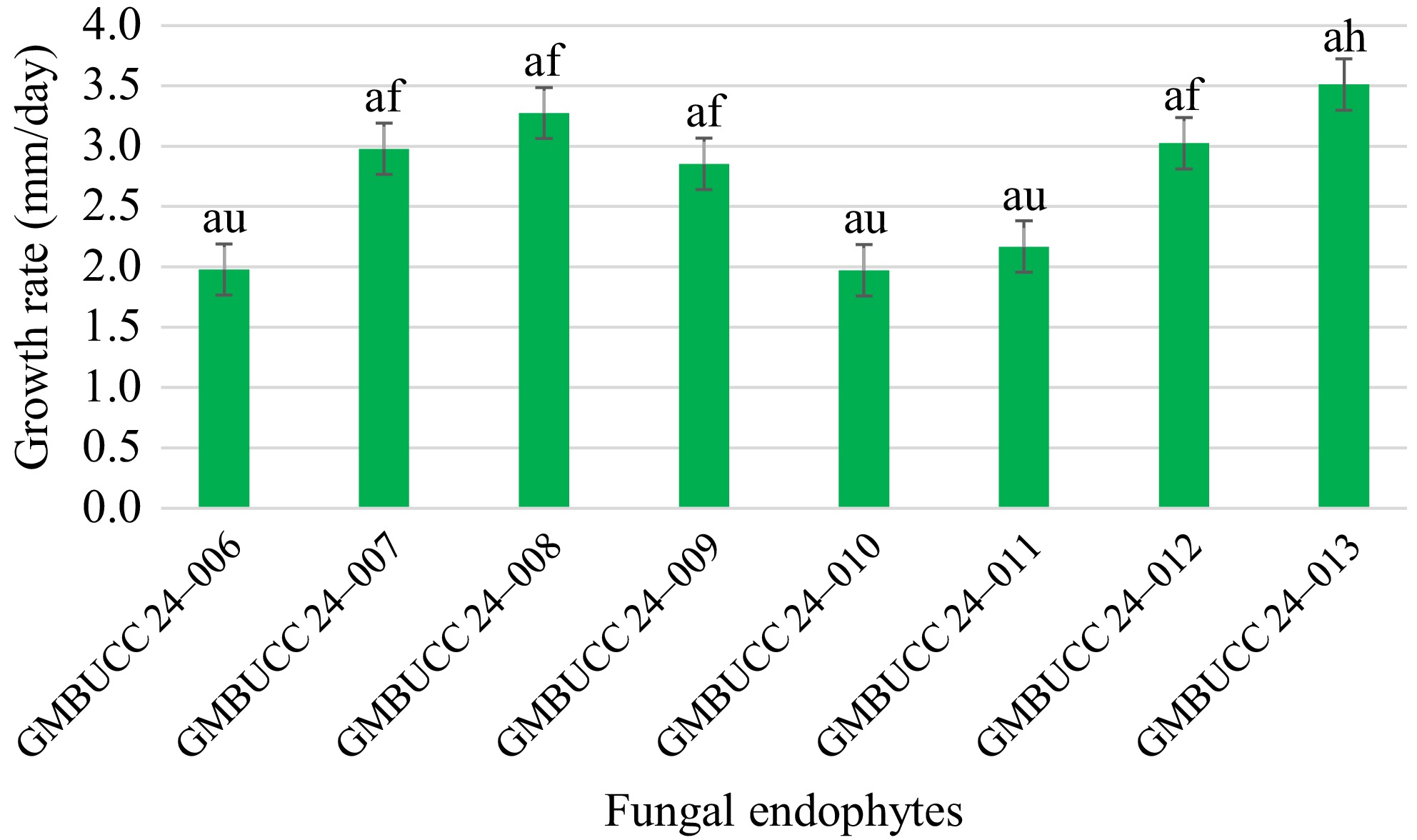

A total of eight fungal endophytes were isolated from Ulva lactuca, Sargassum ilicifolium, and Padina antillarum collected from three different locations in the Southern province (Madiha, Thalpe, and Koggala beaches) of Sri Lanka (Table 3). Colony characteristics of isolated fungal endophytes were observed for morphological characterization of fungal endophytes (Fig. 2, Table 4). The strain GMBUCC 24–013 had the highest radial growth rate among all the fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds when cultured on PDA at 28 ºC for 14 d. The strains GMBUCC 24–008 and GMBUCC 24–012 also showed high radial growth rates while GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–011 exhibited moderate radial growth rates. GMBUCC 24–006 and GMBUCC 24–010 showed comparably lower growth rates (Fig. 3).

Table 3. Endophytic fungal strains isolated from seaweeds found in the southern coastal waters.

Strain no. Collection site Host GMBUCC 24–006 Thalpe beach Padina antillarum GMBUCC 24–007 Madiha beach Sargassum ilicifolium GMBUCC 24–008 Madiha beach Sargassum ilicifolium GMBUCC 24–009 Madiha beach Padina antillarum GMBUCC 24–010 Thalpe beach Ulva lactuca GMBUCC 24–011 Thalpe beach Ulva lactuca GMBUCC 24–012 Koggala beach Ulva lactuca GMBUCC 24–013 Koggala beach Ulva lactuca

Figure 2.

Culture characteristics of isolated endophytes on PDA at 28 °C. (a) Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). (b) Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–007). (c) Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–008). (d) Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–009). (e) Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010). (f) Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–011). (g) Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–012). (h) Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013).

Table 4. Colony characteristic of fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds.

Strain no. Genus Radial growth rate (mm/day) at 28 ºC

on PDAColony colour GMBUCC 24–006 Aspergillus 1.978 Gamboge GMBUCC 24–007 Aspergillus 2.978 Greenish grey GMBUCC 24–008 Aspergillus 3.275 Greenish grey GMBUCC 24–009 Aspergillus 2.854 Greenish grey GMBUCC 24–010 Penicillium 1.972 Dove grey with a

white peripheryGMBUCC 24–011 Penicillium 2.167 Dove grey with a

white peripheryGMBUCC 24–012 Aspergillus 3.024 Greenish grey GMBUCC 24–013 Aspergillus 3.511 Orange with a

white periphery

Figure 3.

Growth rates of isolated fungal endophytes on PDA at 28 ºC. The bars denoted by the same letters are not significantly different from each other.

Preliminary identification of fungal endophytes based on ITS-rDNA sequence

-

The identification of fungal endophytes was carried out using amplified ITS sequences from the genomic DNA, which were approximately 700 bp in length. The nucleotide BLAST search results for the isolated fungal endophytes are summarized in Table 2. Only published, reliable closest matches were considered to accurately identify the fungal endophytes. Eight endophytic fungal strains isolated from Padina antillarum, Sargassum ilicifolium, and Ulva lactuca belong to the phylum Ascomycota, and six out of eight isolates belong to the genus Aspergillus. Four distinct endophytic fungal isolates belonging to the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium were preliminarily identified (Table 2).

-

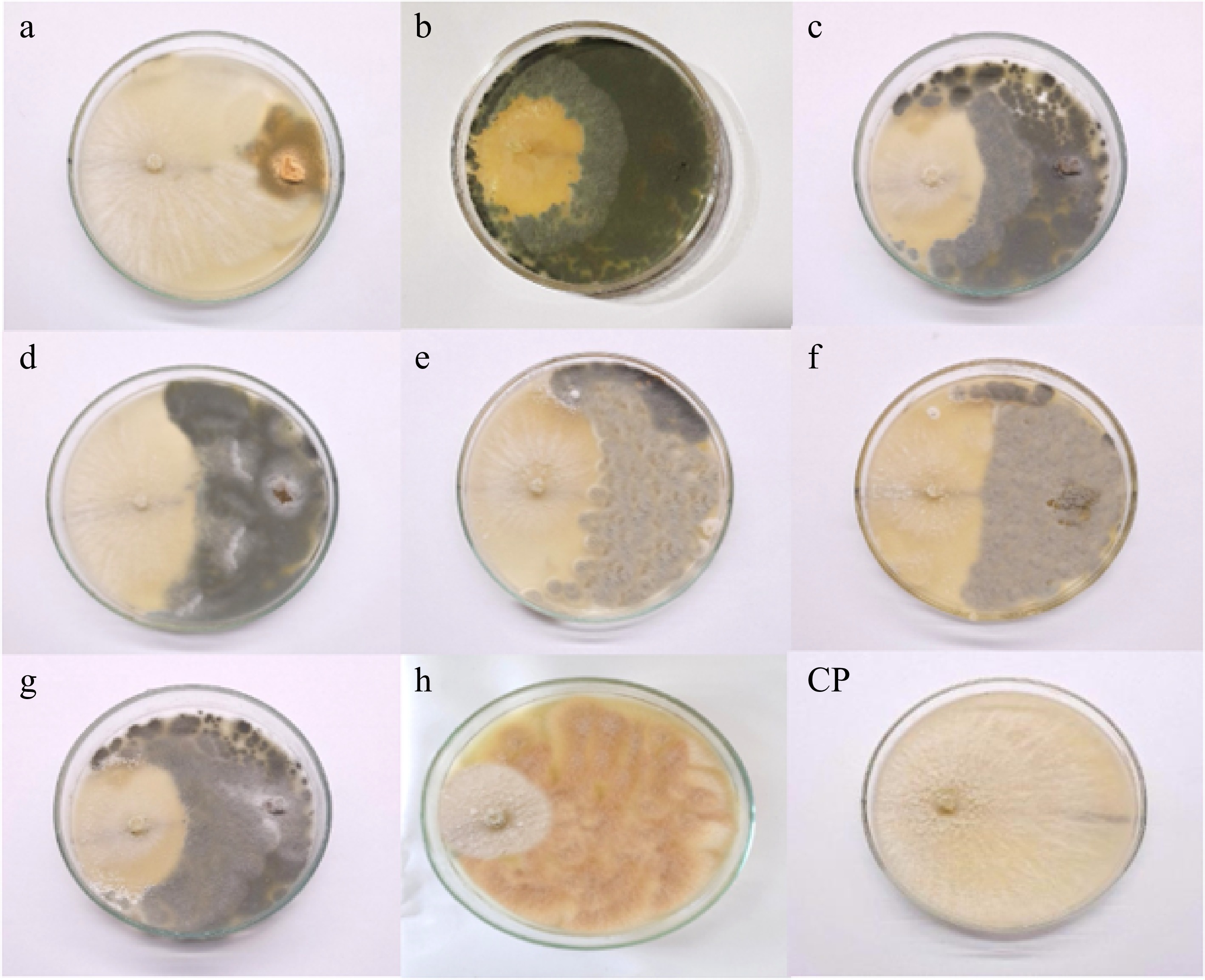

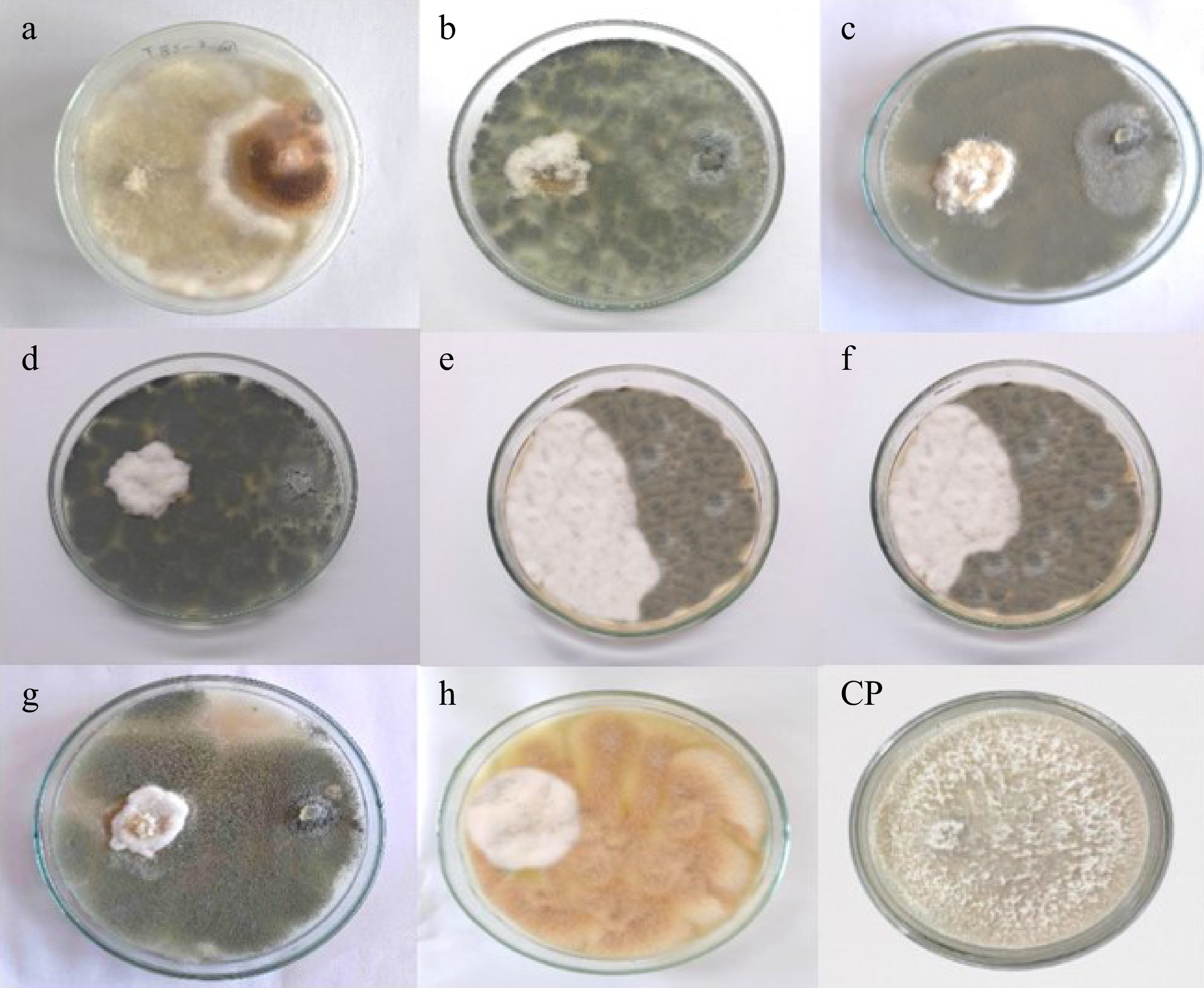

Antagonism between isolated fungal endophytes and Neopestalotiopsis cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) was observed in prepared dual culture plates (Fig. 4). The first apparent physical contact between the phytopathogen N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) and fungal endophytes occurred within 2–3 d after inoculation, followed by growth inhibition of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001). It took seven days for N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) in the control plate to completely cover the PDA medium. There was a significant difference between treatments (endophytes) on the mycelial growth of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 4.

Antagonism between isolated fungal endophytes and Neopestalotiopsis cubana GMBUCC 24–001 (Dual culture plates - a to h) (N. cubana GMBUCC 24–001on the left and fungal endophytes on the right side). (Fungal endophytes in plate; (a) GMBUCC 24–006. (b) GMBUCC 24–007. (c) GMBUCC 24–008. (d) GMBUCC 24–009. (e) GMBUCC 24–010. (f) GMBUCC 24–011. (g) GMBUCC 24–012. (h) GMBUCC 24–013. (CP) Control Plate (N. cubana GMBUCC 24–001).

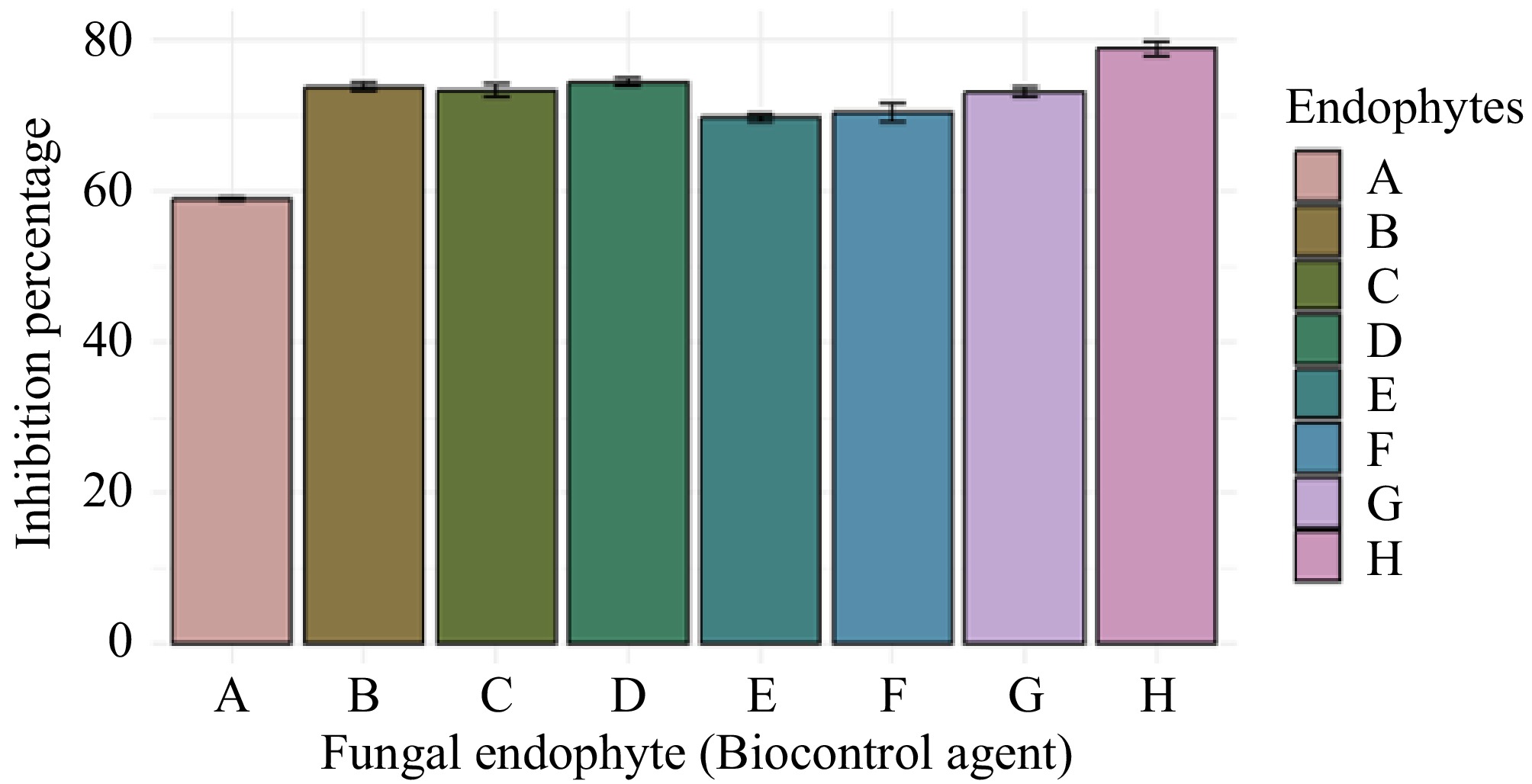

It was observed that Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) significantly inhibited the growth of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) compared to all the other fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds. There was no significant difference between the inhibition caused by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–008, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–012). However, the inhibition caused by these endophytes was significantly different from that of Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). The lowest inhibition of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) among isolated fungal endophytes was shown by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006 and GMBUCC 24–013) showed the highest difference between their effects on the mycelial growth of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001). Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011) showed approximately similar inhibition of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001). However, there was a significant difference between inhibition caused by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013), and inhibition caused by Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011) (Supplementary Table S1).

Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) exhibited the highest growth inhibition percentage against the phytopathogen N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001), while Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006) demonstrated the lowest inhibition percentage. The inhibition by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) was 20.62% higher than that observed with Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). Aspergillus sp. strains GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–008, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–012 exhibited almost similar growth inhibition percentages against N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001), ranking just below the inhibition achieved by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013). Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011) also showed similar inhibition percentages (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Inhibition percentage of N. cubana strain no. GMBUCC 24–001 by different fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds on PDA medium at 28 °C. (a) GMBUCC 24–006. (b) GMBUCC 24–007. (c) GMBUCC 24–008. (d) GMBUCC 24–009. (e) GMBUCC 24–010. (f) GMBUCC 24–011. (g) GMBUCC 24–012. (h) GMBUCC 24–013.

Effect of seaweed endophytes on the growth of Colletotrichum siamense strain no. UKCC 24–012

-

Antagonism between isolated fungal endophytes and C. siamense (UKCC 24–012) was observed in prepared dual culture plates (Fig. 6). The first physical contact between fungal endophytes and phytopathogen, Colletotrichum siamense (UKCC 24–012) cultured on PDA medium, was observed within 2–3 d after inoculation. Pure Colletotrichum culture in the control plate took 10 d to cover the PDA medium completely. There was a significant difference between treatments (endophytes) on the mycelial growth of C. siamense (UKCC 24–012) (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 6.

Antagonism between isolated fungal endophytes and Colletotrichum siamense UKCC 24–012 (Dual culture plates - a to h) (Colletotrichum siamense UKCC 24–012 on the left and fungal endophytes on the right side). (Fungal endophytes in plate; (a) GMBUCC 24–006. (b) GMBUCC 24–007. (c) GMBUCC 24–008. (d) GMBUCC 24–009. (e) GMBUCC 24–010. (f) GMBUCC 24–011. (g) GMBUCC 24–012. (h). GMBUCC 24–013. (CP) Control plate (C. siamense UKCC 24–012).

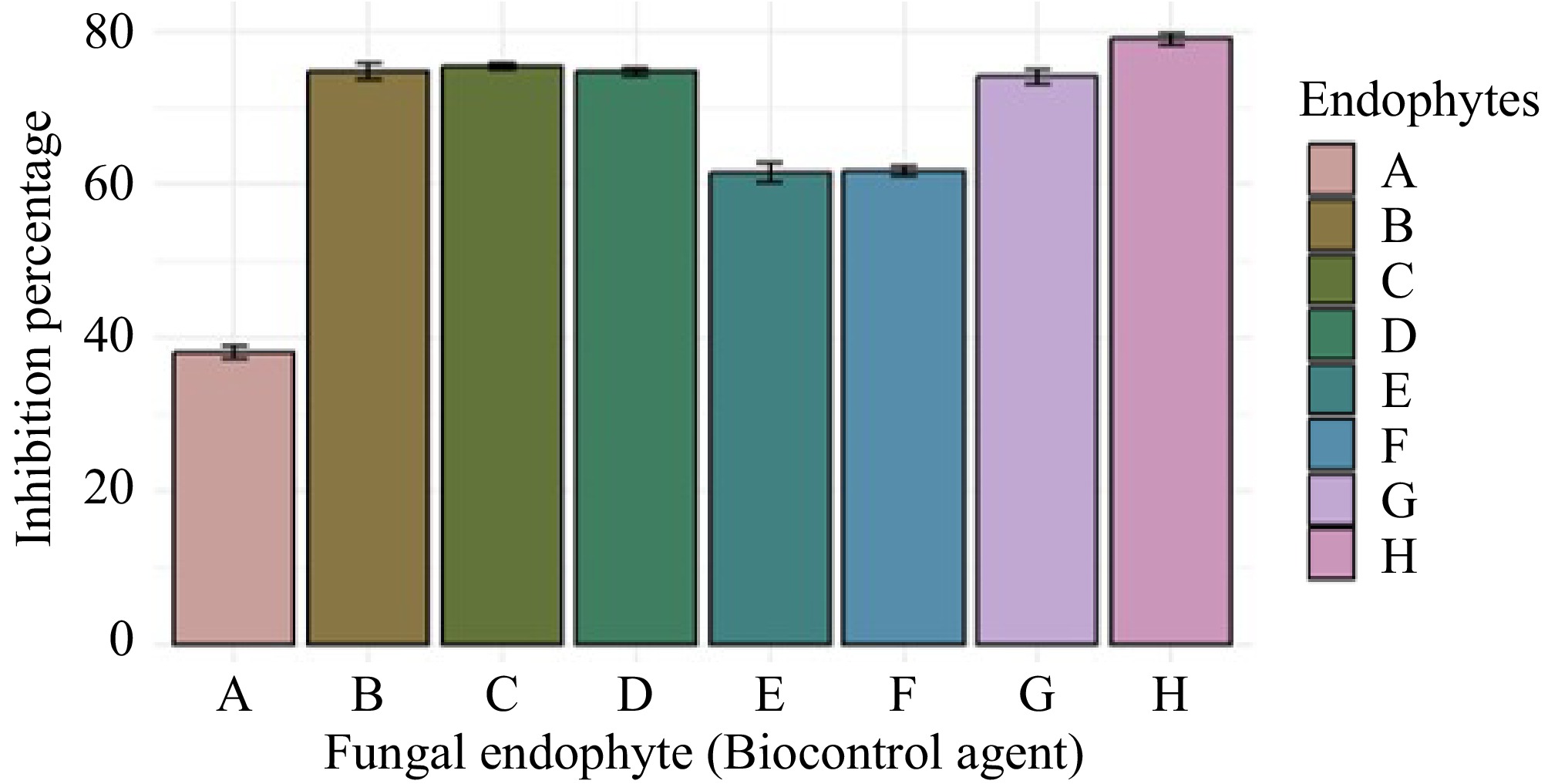

Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) significantly inhibited the growth of C. siamense (UKCC 24–012) compared to all the other fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds. Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006) showed the least inhibition of C. siamense (UKCC 24–012) among all the other isolated fungal endophytes. Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011 showed approximately similar inhibition of C. siamense (UKCC 24–012). However, there was a significant difference between inhibition caused by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006) and inhibition caused by Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011). A significant difference in inhibition of C. siamense was also observed between Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) and Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011). Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–008, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–012) have shown approximately similar levels of inhibition of C. siamense. However, the inhibition caused by these endophytes was significantly different from that of other endophytic isolates (Supplementary Table S2).

Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) exhibited the highest growth inhibition percentage against C. siamense, while Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006) showed the lowest inhibition percentage. The inhibition achieved by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) was nearly double that of Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011) demonstrated similar inhibition percentages, 20.92% higher than those observed for Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006) and 20.12% lower than those observed for Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013). Comparable inhibition percentages were observed with Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–008, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–012) which showed effective inhibition, ranking just below the inhibition percentage of Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Inhibition percentage of Colletotrichum siamense (UKCC 24–012) by different fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds on PDA medium at 28 °C. (a) GMBUCC 24–006. (b) GMBUCC 24–007. (c) GMBUCC 24–008. (d) GMBUCC 24–009. (e) GMBUCC 24–010. (f) GMBUCC 24–011. (g) GMBUCC 24–012. (h) GMBUCC 24–013.

-

In the present study, eight fungal endophytes were isolated from Padina antillarum, Sargassum ilicifolium, and Ulva lactuca collected from three different locations in the southern coastal line (Madiha Beach, Thalpe Beach, and Koggala Beach), Sri Lanka. They were preliminarily identified as four distinct endophytic fungal species belonging to the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium through ITS-rDNA sequence analyses. All the endophytic fungi isolated belong to the phylum Ascomycota. This study represents the first documentation of endophytic fungal species from the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium inhabiting seaweeds collected from Sri Lanka.

Many studies have reported endophytes belonging to the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium as the most frequently isolated fungal endophytes from marine macroalgae[5,11,18−20]. This study further proves this as 75% of the fungal endophytes isolated belong to the genus Aspergillus and the other 25% belong to the genus Penicillium. The predominance of Aspergillus species as endophytes and the absence of commonly dominant, generalist endophytes of terrestrial plants, such as Phyllosticta spp., and Colletotrichum spp., in marine algae suggest that Aspergillus species are specifically adapted to survive as endophytes in marine algae and may have coevolved with their algal hosts[11]. The widespread presence of A. fumigatus across different seaweed species suggests a loose host affiliation[10]. This finding is consistent with the study by Flewelling et al.[10], where A. fumigatus was also isolated from the seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum, Fucus vesiculosus, and Fucus serratus. Only a very limited number of studies have been done on A. heldtiae. It has been found to inhabit millet seed found in South Africa[35]. Penicilllium cataractarum has been identified as an endophyte inhabiting terrestrial plants such as Ginkgo biloba and Ocimum gratissimum and seaweeds such as Ulva lactuca[36,37]. Many researchers who have done studies on seaweed-associated fungal endophytes have only followed traditional identification methods based only on morphology, and they have failed to identify some fungal isolates up to the species level. In most studies, macroalgal hosts were also reported only to the genus level. This has created difficulties in comparing algal hosts and the endophytes inhabiting them. Morphological descriptions alone do not provide 100% accurate identification of endophytic fungi or comprehensive documentation of the fungal biodiversity within marine macroalgae. Therefore, there is a need to enhance molecular identification procedures for endophytic fungi. However, relying solely on ITS-rDNA sequence data for species identification may also yield results that are not entirely accurate due to the presence of cryptic species. To accurately resolve species boundaries, multi-gene analyses are required[4].

In this study, species identification was based on ITS-rDNA sequence data, but these identifications could be refined with future multi-locus phylogenetic analyses. In addition, the nomenclature, and classification of many fungal species have been subjected to change during the past few decades due to modern taxonomic approaches and concepts. Hence, corrections to those changes are mandatory to avoid misinterpretations.

Fungal phytopathogen Colletotrichum spp. is the cause of the severe crop disease anthracnose that can be seen in a range of ornamental, fruit, and vegetable species. Fungal infections caused by Colletotrichum spp. can occur both in the field and at the post-harvest stage, causing leaf spots, and severe lesions on fruits and vegetables leading to significant crop losses[27,38,39]. Another common phytopathogen, N. cubana, can cause a broad range of diseases, including leaf spots, grey blight, severe chlorosis, and various postharvest diseases in various economically important crops[40]. Due to the ability to produce bioactive compounds with potential antifungal properties, fungal endophytes, which inhabit seaweeds, have gained significant attention in the search for sustainable biocontrol agents against phytopathogenic fungi like N. cubana and C. siamense. The present study has also demonstrated the biocontrol potential of several fungal endophytes belonging to the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium, isolated from seaweeds found in the southern coastal waters of Sri Lanka, against phytopathogenic fungi; N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) and C. siamense (UKCC 24–012).

Novel bioactive compound production by endophytic fungi is a result of their adaptation to the marine environment[41]. A wide variety of bioactivity, such as anticancer, antimicrobial, anti-infective, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and insecticidal activity, has been reported by Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. obtained from different hosts in different locations[11,42−46]. The results of the dual culture assay involving N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) and isolated fungal endophytes revealed the maximum growth inhibition of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) with Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) and the lowest growth inhibition of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001) with Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). The inhibition percentage of Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) was 20.62% higher than that of Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–008, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–012) also showed significant inhibition of N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001), becoming only second to the inhibition shown by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013). Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010 and GMBUCC 24–011) exhibited a higher inhibition percentage than Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006) and a lower inhibition percentage than Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013). According to the results, Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) can be considered the most suitable candidate (among the fungi isolated in the present study) for use as a biocontrol agent against N. cubana (GMBUCC 24–001), followed by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–009).

In this study, the highest growth inhibition of C. siamense (UKCC 24–012) was shown by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013), and the lowest growth inhibition of C. siamense (UKCC 24–012) was shown by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). The inhibition percentage shown by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) was almost double that of Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006). Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–008, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–012) also exhibited a significant inhibition of C. siamense (UKCC 24–012), becoming only second to the inhibition shown by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013). Penicillium sp. (GMBUCC 24–010, and GMBUCC 24–011) showed a higher inhibition percentage than Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–006) and a lower inhibition percentage than Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013). According to the results, Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–013) can be considered the most effective biocontrol agent (among the fungi isolated in the present study) against C. siamense (UKCC 24–012), closely followed by Aspergillus sp. (GMBUCC 24–008). This does not align with the results of a study done by Haider et al.[47]. In that study, a few Aspergillus species, like A. flavus, A. fumigatus, and A. niger, were isolated from the twigs and fruits of guava plants and tested for their antifungal activity against C. siamense causing anthracnose in guava[47]. Unlike the results obtained in the present study, A. fumigatus exhibited a relatively low percentage of inhibition of C. siamense[47]. Many previously conducted studies have suggested a difference in metabolic profile between natural compounds isolated from marine-derived endophytes and endophytes associated with terrestrial plants[5]. Also, the active metabolite profile of the same species of endophytes isolated from different algal hosts differs, indicating genetic variation among the endophytes[5]. So, this may explain the contrasting results between the present study and the study carried out by Haider et al.[47], and it is clear that even though A. fumigatus isolated from seaweeds can be used as an effective biocontrol agent against C. siamense, the same endophyte species isolated from guava plants cannot be used for the same purpose. But several Aspergillus species, like A. flavus and A. niger, which inhabit terrestrial plants, have proven to be effective in controlling the growth of C. siamense[47]. In a study carried out by Eshboev et al.[36], P. cataractarum isolated from the plant Ginkgo biloba has been found to produce bioactive compounds with antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. However, studies showing the antifungal activity of P. cataractarum were not found.

This study could also help to determine whether there are individual fungal endophyte species differences among the groups of macroalgae. Furthermore, it also contributes to the research that has been performed to see whether global geographic, seasonal, or climatic changes may account for endophytic fungal diversity in seaweed obtained from different geographic locations. Studying fungal endophytes residing inside seaweeds found in the southern coastal waters of Sri Lanka also enhances our understanding of the fungal diversity present in the country's marine ecosystems. Coastal ecosystems encounter increasing pressure from anthropogenic activities such as habitat degradation, increasing pollution, and climate change. Therefore, understanding the ecological roles of marine microorganisms, such as fungal endophytes, becomes imperative for ecosystem resilience and sustainability.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: collection of seaweed species, isolation of fungal endophytes, and manuscript writing: Abeygunawardane S; fungal identification, manuscript revision: Thambugala KM, Kumara K, Daranigama D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

All the data generated and analyzed during this study are available in the article. DNA sequence data are available in the GenBank database, and the accession numbers are provided in Table 3.

-

The author would like to acknowledge the facilities and chemicals provided by the research laboratories of the Faculty of Agriculture at the University of Ruhuna and the Genetics and Molecular Biology unit of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Mean mycelial growth of Neopestalotiopsis cubana against different fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds on PDA medium at 28 °C.

- Supplementary Table S2 Mean mycelial growth of Colletotrichum sp. against different fungal endophytes isolated from seaweeds on PDA medium at 28 °C.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Abeygunawardane S, Thambugala KM, Kumara W, Daranagama D. 2025. Seaweed-associated fungal endophytes from southern Sri Lanka and their biocontrol potential against selected fungal phytopathogens. Studies in Fungi 10: e002 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0002

Seaweed-associated fungal endophytes from southern Sri Lanka and their biocontrol potential against selected fungal phytopathogens

- Received: 10 December 2024

- Revised: 14 February 2025

- Accepted: 16 February 2025

- Published online: 27 February 2025

Abstract: Fungal endophytes are an endosymbiotic group of fungi that live asymptomatically in healthy tissues of plants and macroalgae. Due to their ability to produce bioactive compounds with potential antifungal properties, fungal endophytes that inhabit seaweed have gained significant attention in the search for sustainable biocontrol agents against phytopathogenic fungi and bacteria. The present study is aimed at identifying fungal endophytes that reside inside seaweeds found in the coastal waters of Southern Province, Sri Lanka, and investigating their biocontrol potential against two fungal phytopathogens; Neopestalotiopsis cubana (Sporocadaceae, Amphisphaeriales) and Colletotrichum siamense (Glomerellaceae, Glomerellales). This is the first study to discover fungal endophytes associated with seaweeds found in the waters of Sri Lanka. Eight fungal endophytic strains were isolated from seaweeds; Padina antillarum (Dictyotaceae), Sargassum ilicifolium (Sargassacea), and Ulva lactuca (Ulvophyceae), found in Thalpe, Madiha, and Koggala beaches. Based on ITS-rDNA sequence analyses, they were preliminarily identified as four distinct endophytic fungal species belonging to the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium. Isolated fungal endophytes were tested for their biocontrol potential against two selected fungal pathogens using a dual culture assay. Percent growth inhibition (PI) of the test pathogens was calculated. Among the isolated fungal endophytes, Aspergillus sp. GMBUCC 24–013 showed the strongest antagonistic activity against both C. siamense UKCC 24-012 and N. cubana GMBUCC 24–001 closely followed by Aspergillus sp. GMBUCC 24–007, GMBUCC 24–008, GMBUCC 24–009, and GMBUCC 24–012. Aspergillus sp. GMBUCC 24–006 exhibited the least biocontrol potential against both phytopathogens, while Penicillium sp. GMBUCC 24–010, and GMBUCC 24–011 showed moderate activity.

-

Key words:

- Aspergillus /

- Biocontrol agents /

- Fungal phytopathogens /

- ITS-rDNA /

- Macroalgae /

- Penicillium