-

Retinal degenerative diseases, such as retinitis pigmentosa[1−4] and age-related macular degeneration[5], mainly manifest as retinal dysfunction, resulting in the loss of photoreceptor cells and retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE). This gradual loss of cells can eventually lead to vision loss and blindness.

Retinal degenerative diseases currently lack an effective treatment. The current clinical management of retinal degenerative diseases involves the use of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, which target neurotrophic and anti-inflammatory pathways[6,7]. They can provide only symptomatic relief, but cannot alter the cause of diseases. New treatment options, such as gene therapy[8], cell therapy, and novel small-molecule drugs[9,10], have shown promising results in preclinical and clinical research. However, these treatments are still in the exploratory stages. Gene therapy holds the potential to treat retinitis pigmentosa, a genetically complex and mutagenic disease; however, it can only target specific mutated genes and cannot restore damaged RPE and photoreceptor cells. As a result, effective treatment for retinal degenerative diseases remains an unmet need in the field.

Stem cell-based transplantation represents another potential novel treatment for retinal degenerative diseases that is based on cell replacement or nutrition strategies[11]. In recent years, stem cell therapy has garnered widespread attention and is broadly divided into two categories, depending on the source of the stem cells. The first category comprises stem cells derived from exogenous sources such as human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), mesenchymal stem cells, neural stem cells, and embryonic stem cells. The second category includes cells differentiated from native retinal stem cells or stem cells derived from Müller glial cells and retinal pigment epithelium stem cells. Recent research has shown that photoreceptor-like cells derived from hiPSCs can reverse vision loss in a mouse model, demonstrating their therapeutic potential[12]. However, there are several hurdles to overcome before these cells can be applied clinically, including the use of immunosuppressants, and the time-consuming and quantity-limited process for generating photoreceptor-like cells.

Both acute and chronic retinal damage exists, while transplantation of retina was unrealized in a clinical setting. Without timely treatment, photoreceptor loss will initiate a deteriorative chain of events, such as vessel displacement, axonal transport alteration, and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death[13]. Therefore, faced with large groups in the clinics of photoreceptor loss, quickly induced reprogramming of iPSCs and producing transplantable photoreceptors are necessary for translational medicine.

This study aimed to contribute to translational medicine by developing a two-step method for differentiating CiPCs from hiPSCs within three weeks using chemical reprogramming of fibroblasts as an intermediate stage. Our method was efficient in generating a large quantity of CiPCs and, crucially, restored photosensitivity in photoreceptor degenerated mice without being affected by the mouse immune system as indicated by no co-administered immunosuppressants. As a result, CiPCs show potential as a treatment option for etiologically treating retinal degenerative diseases and restoring lost vision in the clinic with lower, or no use of immunosuppressants in the future.

-

FLCs were differentiated from hiPSCs. The reagents used in procedures were obtained from Guangdong Procapzoom Biosciences (Guangdong, China) with its PC-Diff kit, or purchased from other manufacturers as described below. The human iPSCs used in this study were commercially purchased from Biobw (Bio-51699, Biobw, China) and were cultured in the mTeSR™ Plus Basal Medium (100-0276, StemCell, USA). Once the cells reached 70%−80% confluence, the medium was changed to alpha MEM (C12571500BT, Gibico, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% MEM NEAA (11140-050, Gibico, USA) to induce the differentiation process. Cell culture was performed at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator, the fresh medium was supplemented daily during the first four days and then all the medium was replaced every two days from day 6 to 12. Cells were detached with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA, stopped by alpha MEM containing 10% FBS, and plated onto a vitronectin protein (92549ES10, Yeasen, China) coated 6-well plate at a density of 1 × 106 per well. After cells reached confluence (usually five days) on the vitronectin protein-coated plates, they were detached and seeded onto 0.1% Matrigel-coated six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 per well.

FLCs are differentiated into CiPCs

-

The FLCs were cultured with cocktail medium A, which consisted of 10% alpha MEM, 80% DMEM-F12, 10% KOSR (10828010, Gibco, USA), and small molecules, including B27 Supplement, gremlin-1 (2 μg/ml), and Recombinant Human EGF Protein (100 μg/mL) in a 12-well plate until they reached 95-100% confluence. On day 1, the medium was replaced with cocktail medium A and small molecules, including 3μM Vorinostat, 1 μM AZD2858, 10 μM SB-431542, 10 mM SQ22536. On day 2, the cells were treated with cocktail medium A and small molecules (3 μM Vorinostat, 1 μM AZD2858, 10 μM SB-431542, 10 mM SQ22536, and 5 μM iCRT3). On day 3, cocktail medium A was used, adding extra small molecules, including 3 μM Vorinostat, 1 μM AZD2858, 10 μM SB-431542, 10 mM SQ22536, 10 μM iCRT3). On day 5, cocktail medium A with eight small molecules (3 μM Vorinostat, 1 μM AZD2858, 10 μM SB-431542, 10 mM SQ22536, 10 μM iCRT3, 2 μM Sonic hedgehog, 10 mM Taurine, and 100 nM BMS493). On day 6, the photoreceptor-like cells were observed, collected, and cultured in cocktail medium C, which consisted of DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% B27 Supplement, 0.1% N2, 2 μg/ml gremlin-1, and 100 μg/mL Recombinant Human EGF Protein, 10 μM iCRT3, and 100 μg/mL bFGF. Quality control was handled throughout the cell culture and differentiation and detailed information is listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Flow cytometry

-

CiPCs were obtained by the differentiation method as described above, they were then collected for flow cytometry assay. Before the flow cytometry assay, the CiPCs were detached by 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA for 3-5 min until the cells became spheroidal, then stopped with DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS and transferred into a 50 ml tube. After being washed twice with PBS, the cells were incubated with anti-Cone-Arrestin (AP5331, Abcepta, China), anti-rhodopsin (ab221664, Abcam, USA), or anti-recoverin antibody (ZRB1107, Millipore, USA) at 1:1000 diluted with PBS for 2 h at room temperature. Next, the cells were washed and incubated with the 550 (33108ES60, BOSTER, USA) or 488 (BA1126, BOSTER, USA) secondary antibodies diluted at 1:1000 in PBS, according to anti-Cone-Arrestin, anti-rhodopsin, or anti-recoverin primary antibodies, for 1 h at room temperature, respectively. The cells were then washed with PBS and examined using an A1 flow cytometer (FACSymphony, BD, USA). For hiPSCs analysis, the negative controls used PBS replacing the primary antibodies for incubating the cells. In the analysis of CiPCs, the undifferentiated hiPSCs being incubated with primary and secondary antibodies were used as negative controls. For the CiPCs enrichment, the antibodies of anti-Cone-Arrestin, anti-rhodopsin, and anti-recoverin were used for flow cytometry sorting. The cell sorting was performed with the flow cytometer (FACSAria III, BD, USA).

Ca2+ imaging

-

The dissociated CiPCs were plated on cover glasses in a 24-well plate and incubated at 37 °C with CO2 for 24 h without light. The next day, the culture medium was exchanged with Ringer's buffer containing 4 μM Fluo-4 AM (Yeason, China) with incubation for 45-60 min. One cover glass containing CiPCs was then relocated to a chamber in the object stage of an FN-S2N Nikon microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) The chamber was filled with the Ringer's buffer containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 2.5 NaHCO3, and 10 Glucose (pH = 7.4, with NaOH). Intracellular calcium signal of CiPCs was induced by perfusion of a high K+ buffer containing (in mM): 68 NaCl, 60 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 2.5 NaHCO3, and 10 Glucose (pH = 7.4, with KOH). A 40× objective lens (NA0.8) was used to identify CiPCs loaded with 4 μM Fluo-4 AM, and then Ca2+ imaging was captured with a CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) installed in the microscope. The baseline was captured at a 20-s intervals in the first minute, then Ca2+ imaging was induced with the high K+ buffer and captured at 1 Hz frequency. Data were presented as F/F0 (F referred to the fluorescence signal at different time points, and F0 was the average of the baseline) and analyzed with GraphPad Prism (version 8.0, GraphPad, USA).

Electrophysiologic recording

-

The dissociated CiPCs were plated on cover glasses in a 24-well plate and incubated at 37 °C with CO2 for 24 h without light. The next day, one cover glass containing CiPCs was then relocated to a chamber filled with the desired extracellular solution under the electrophysiology microscope (ECLIPSE FN1, Nikon, Japan) for patch clamp recording. Pipettes (Sutter, USA) were pulled with a pipette puller (P-97, US) with a resistance of 3−4 MΩ when filled with an internal solution. The action potential, Na+ current, K+ current, and Ca2+ current, were recorded with an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA, DE) in a whole-cell patch-clamp mode. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8.0. Na+ currents were recorded when a cell was held at –90 mV with voltage steps ranging from –100 to 50 mV at a 10-mV incremental and 100 mS interval. The extracellular solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 0.05 CdCl2, and 10 HEPEs (pH = 7.4, with NaOH). The intracellular solution contained (in mM) 140 CsF, 1 EGTA, 10 NaCl, and 10 HEPES (pH = 7.2, with CsOH). K+ currents were recorded when the cell was held at –70 mV and voltage steps ranging from –100 to 50 mV at a 10-mV incremental and 1000 mS interval. The extracellular solution contained (in mM) 132 NaCl, 4 KCl, 10 HEPES, 11 glucose, 3 CaCl2, and 0.5 MgCl2 (pH = 7.35, with NaOH). The intracellular solution contained (in mM) 60 KF, 70 KCl, 5 HEPES, and 5 EGTA (pH = 7.2, with KOH). Action potentials were recorded when CiPCs were injected with current ranging from 0 pA to 100 pA at a 10-pA incremental and 1,000 mS interval. The extracellular solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 D-Glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH = 7.4, with NaOH). The intracellular solution contained (in mM) 145 KCL, 5 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 4 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH = 7.2, with KOH).

Animals

-

Male wild-type C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks old) were used in this study. All mice were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Guangdong Province, China. The mice were maintained in the SPF laboratory (with a room temperature of 18−23 °C, 40%−65% humidity, 12/12 h dark/light cycle, and free access to regular food and water conditions) of the animal facility at Jinan University (China).

MNU model and CiPC treatment

-

MNU (MACKLIN, China) was kept at 4−8 °C in the dark. 1% MNU was dissolved in physiologic saline and then injected into the mice intraperitoneal space at 60 mg/kg body weight to induce photoreceptor degeneration in the retina. As MNU at 60 mg/kg induced a serious degeneration of photoreceptors within a week[14], we examined the light response of MNU-injured mice 1 week later to ensure a major loss of photoreceptors. Any animals that showed remaining ERG responses were excluded from further studies. Then 1 week after the model verification, mice were injected with CiPCs into the subretinal space of both eyes (20,000 cells in 1 μL/eye). The control mice were injected with the physiologic saline. All mice were examined with ERG every 2 weeks after the subretinal injection until 6 weeks.

Electroretinogram

-

To measure the retinal light responses, the electroretinogram (ERG) test was carried out as previously described[15]. Briefly, after 6 h dark-adaption, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg 1.25% tribromoethanol under dim red light, and the pupils were dilated by tropicamide phenylephrine eye drops (Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan). Mice were next placed on a heated platform, and ERGs were recorded by the RETI scan system (Roland Consult, Wiesbaden, Germany) using gold-plated wire ring electrodes that touched the surface of the moist cornea as the active electrodes. Stainless steel was inserted into the skin of the eyes and tail of the mice as the reference and ground electrodes respectively. For the scotopic ERGs, the scotopic response to the green flash of 0.01, 0.1, and 3 cd/m2 was recorded. For the photopic ERGs, the mice were light-adapted for 5 min with a 25 cd/m2 green background, then the photopic response to the green flash of 3, and 10 cd/m2 was recorded. The ERG data were collected by the amplifier of the RETI-scan system with a 2 kHz sampling frequency, and then the a-wave and b-wave amplitude were analyzed with the RETI-scan software after a 50 Hz low-pass filter. For each animal, data were obtained from the most responsive eye. Animals with b-wave amplitude smaller than 5 μV at scotopic 0.1 cd/m2 were considered non-responsive and those with larger amplitudes were considered light-responsive.

Tissue processing, immunofluorescence, and image processing

-

To examine the transplanted CiPCs, at 2 and 4 weeks after CiPCs injection, animals were sacrificed by overdose of anesthesia, and the eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min at room temperature. The eyecups with lens were then washed with PBS and cryo-protected overnight at 4 °C in 0.01 M PBS containing 30% sucrose, and ultimately embedded in the optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT; Tissue Tek, Torrance, CA, USA). Retinas were cryo-sectioned on a microtome (Leica Microsystems, Buenos Aires, Argentina) through the optic disk (OD) longitudinally at a thickness of 16 μm. Thereafter, retinal sections were incubated with DAPI (1:1,000, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) for 5 min at room temperature prior to mounting on the coverslip and sealed.

Fluorescent images were captured with either a fluorescence microscope or a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). To look for the DiR (#125964, Perkinelmer, US., absorption: 748 nm, emission: 780 nm) labeled CiPCs, the filter set was adjusted as 710 excitation/760 emission on the confocal microscope to capture the fluorescent signals. Then the whole c-cup of the retinal section with DAPI staining was captured by the fluorescent microscope.

Statistical analysis

-

For the data with statistical analysis, One-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA in Prism GraphPad (Version 8.0, GraphPad Software Inc, USA) were used to compare means among different groups for single variate or multiple variables, respectively. p < 0.05 was considered as statistically different.

-

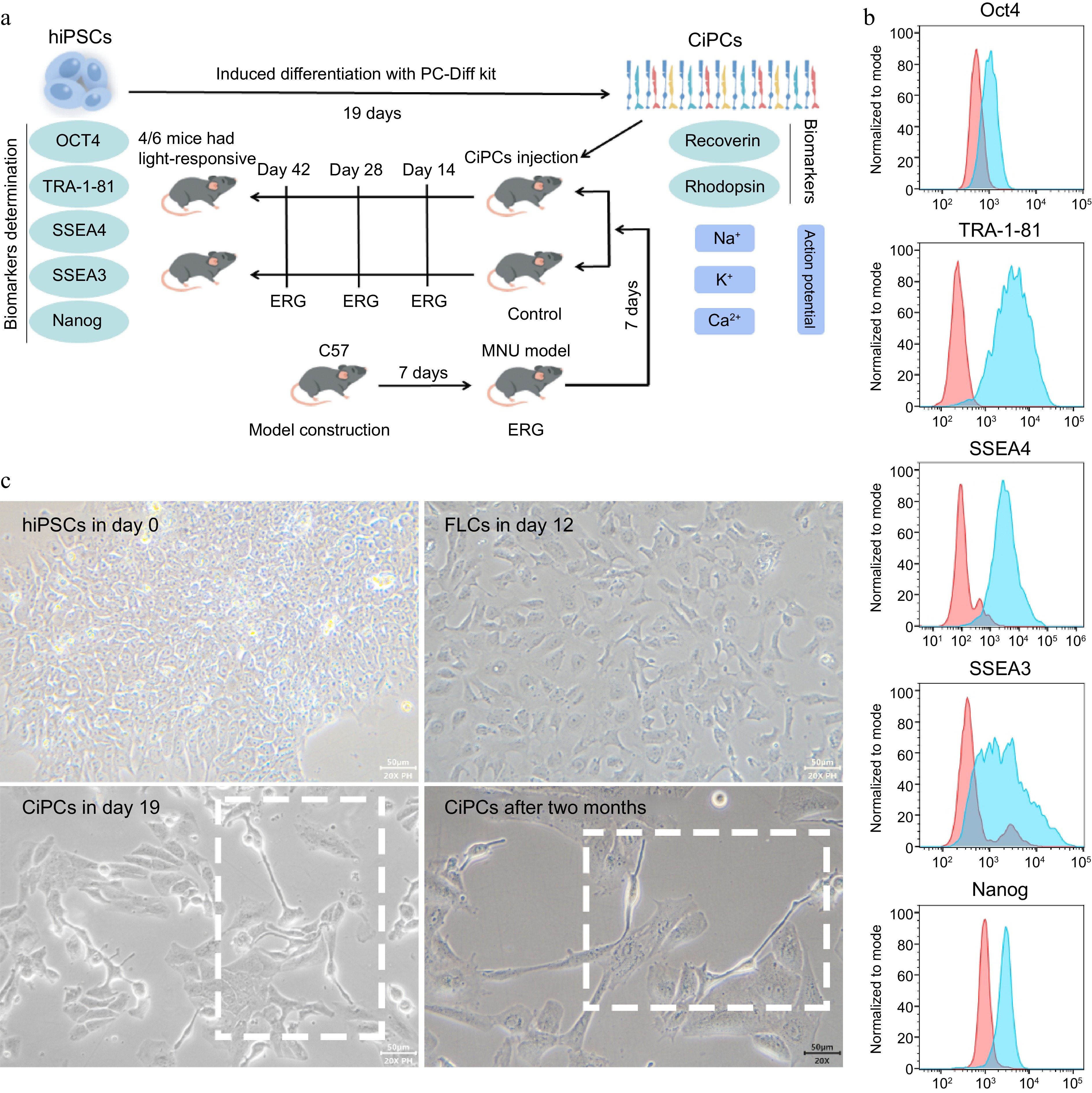

The differentiation of CiPCs was carried out following the schematic and procedure illustrated in Fig. 1a. First, we confirmed the expression of pluripotency biomarkers Oct 4, TRA-1-81, SSEA4, SSEA3, and Nanog in the hiPSCs used (Fig. 1b). Then, during the initial differentiation stage, we observed the hiPSCs transitioning from a round and compact morphology to a spindle-like shape, ultimately giving rise to FLCs (Fig. 1c, upper panels). By continuously applying reprogramming molecules, the cell morphology underwent further changes and relevant biomarkers were expressed (Supplementary Fig. S1). At this stage, the cells were identified as CiPCs and had been passaged for extended periods of time without any noticeable changes in morphology or cell number (Fig. 1c, bottom panels).

Figure 1.

The character determination and induced differentiation of hiPSCs. (a) Schematic of CiPC generation and the experiment. (b) The biomarkers of hiPSCs used in the study. The positive signals of hiPSCs were presented as blue peaks and the negative controls were as red peaks. (c) The differentiation from hiPSCs to CiPCs which maintained morphology for at least two months.

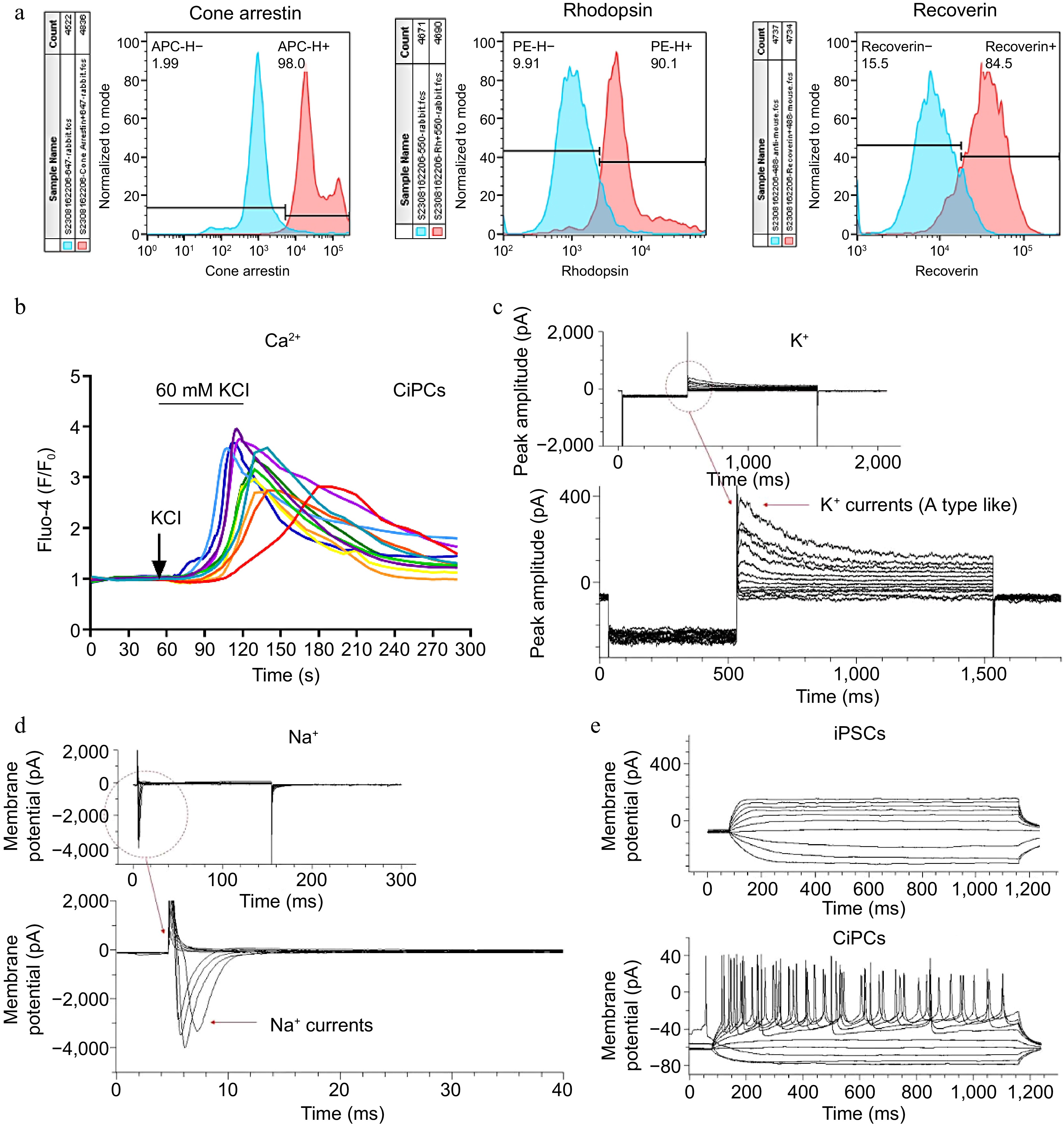

To further characterize the CiPCs, we examined the expression of photoreceptor markers recoverin and rhodopsin, as well as functional ion channels. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the majority of CiPCs expressed Cone-Arrestin, Rhodopsin, and Recoverin (Fig. 2a). Additionally, Western blotting data and Flow cytometry data showed that during the differentiation period, the iPSCs specific markers, TRA-1-60 and Oct4 were unexpressed in the FLCs. While the CD44, which is expressed in both fibroblast cells and stem cells could be still detected in FLCs but disappeared in CiPCs (Supplementary Fig. S2a & c). Then the photoreceptor markers, Recoverin, Rhodopsin, and Cone-Arrestin were only observed in CiPCs (Supplementary Fig. S2b). For the functional determination, calcium imaging showed a significant increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels upon stimulation with a high K+ solution, indicating the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum in CiPCs. The fluorescence signal decreased as intracellular Ca2+ was transported back to the ER, with each round of stimulation triggering a repeated Ca2+ wave (Fig. 2b). Whole-cell recordings from CiPCs revealed the presence of an A-type-like K+ current that displayed a large outward current with a peak of around 400 pA upon membrane depolarization (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, a huge inward current of ~3,500 pA of Na+ was observed with hyperpolarization (Fig. 2d). Most importantly, by injecting a current of 30 pA into the CiPCs, we successfully induced action potentials (Fig. 2e). These results demonstrate the functional maturation of CiPCs towards a photoreceptor-like phenotype.

Figure 2.

The biomarker and function detection of CiPCs. (a) The expression of Cone-Arrestin, Rhodopsin, and Recoverin on CiPCs. The positive signals of CiPCs were presented as red peaks and the undifferentiated hiPSCs were used for negative controls as blue peaks. (b) The Ca2+-relevant fluorescence changes on CiPCs when it was perfused with the high K+ buffer. With continued stimulation, the signal intensity gradually decreased from the initial purple trace to the final red trace. (c) K+ currents on CiPCs. (d) Na+ currents on CiPCs. (e) Action potential of CiPCs.

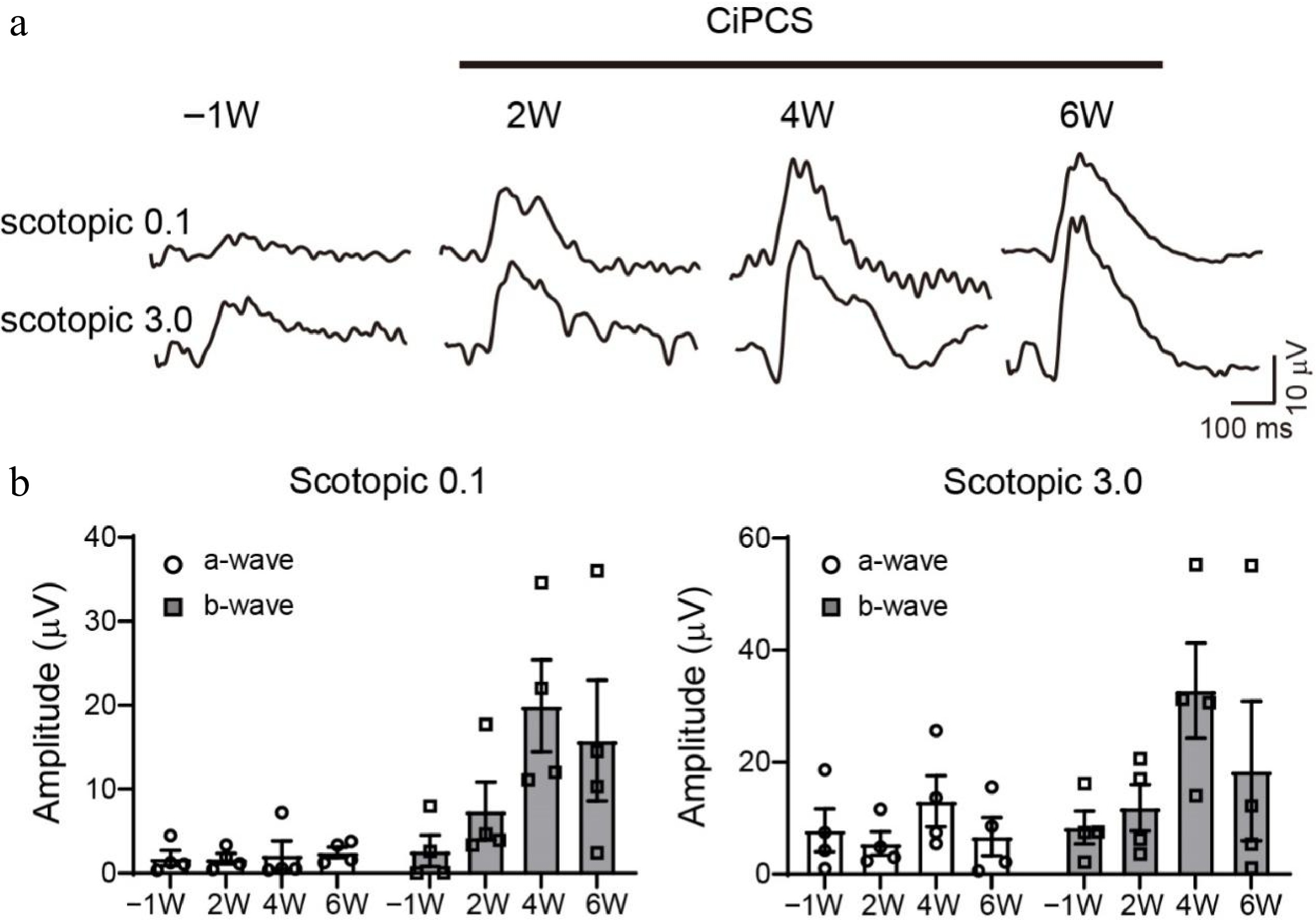

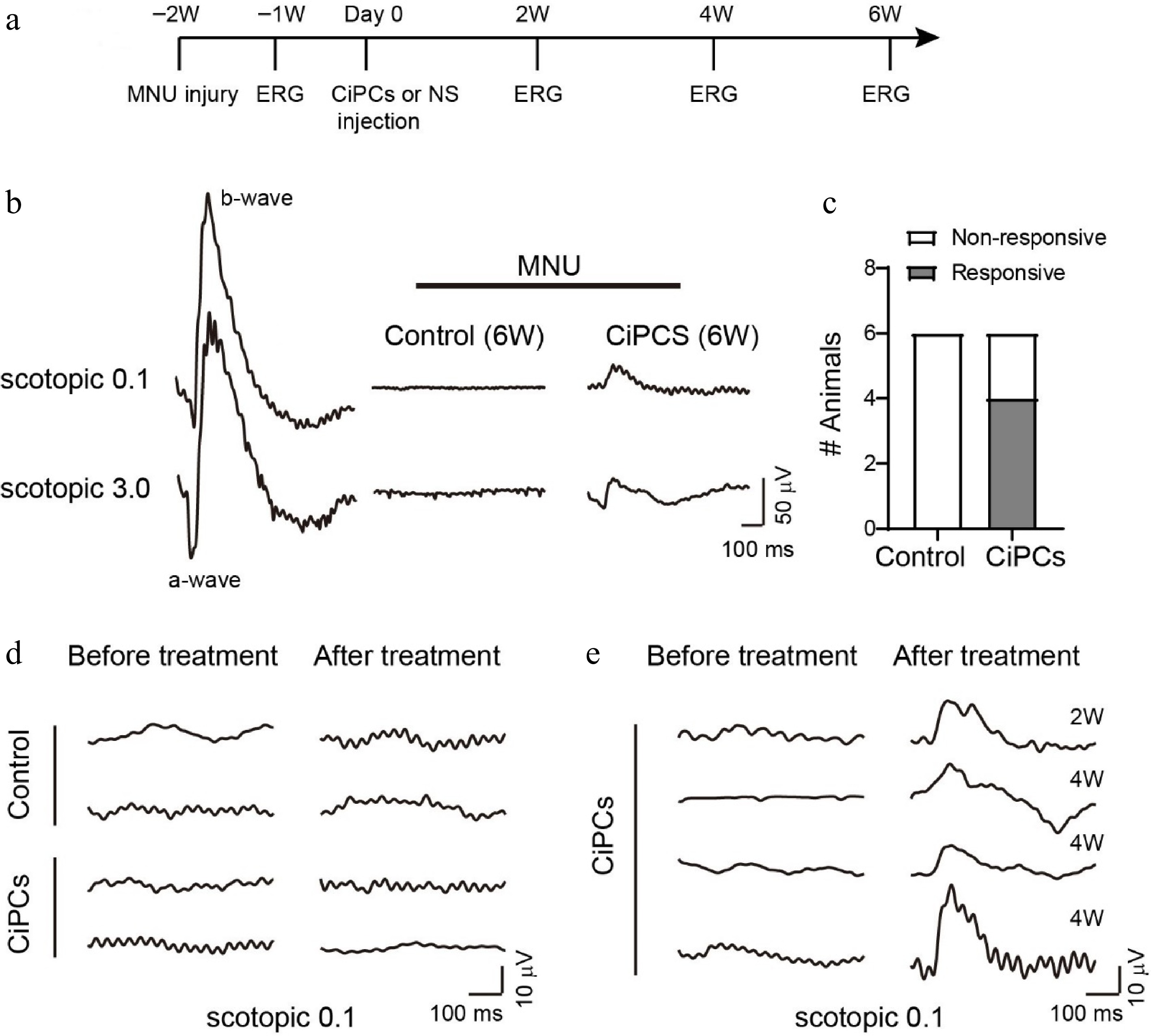

Once the characterization of CiPCs was completed, we proceeded to inject these cells into mice with MNU-induced photoreceptor loss to evaluate their capacity to restore vision. No immunosuppressants were co-administered with the cells during the experiment. To this end, we performed ERG recordings at different time points (Fig. 3a). Before MNU-treatment, all mice displayed large scotopic a-waves (group light responses of photoreceptors), and b-waves (group responses of bipolar cells), which were easily recorded (Fig. 3b, left panel). However, after MNU injection, both a-wave and b-wave responses were absent in the injured mice, which confirmed the complete loss of photoreceptor cells. Thereafter, mice with confirmed vision loss were subretinally injected with 20,000 CiPCs per eye, and ERG recordings were conducted every two weeks to evaluate the restoration of photosensitivity.

Figure 3.

CiPCs restored retinal light response in MNU-injured mice. (a) Experimental schedule. (b) Examples of ERG traces from a normal mouse and MNU-injured mice after 6 weeks of CiPCs injection or control solution. (c) The number of animals tested with light-responsive and non-responsive in the control and CiPCs treatment group. (d) Example ERG traces of control (top) or CiPCs (bottom) treated animals showing no light response before (left) and at 6 weeks after treatment (right). (e) ERG traces of four CiPCs treated animals that partially restored light responses at 2 weeks or 4 weeks after treatment.

Following the administration of MNU, none of the control group (n = 6) and two CiPC-treated mice, displayed any light responses throughout the entire 6-week experimental duration (Fig. 3b middle & d top). However, in the remaining four CiPC-treated mice, clear b-wave responses were observed at 2−4 weeks after the injection of CiPCs (Fig. 3b right & e). Notably, the ratio of responsive animals in the CiPC-treated group was significantly higher when compared to that of the control group (4/6 vs 0/6, Fig. 3c).

We further monitored the restoration of ERG responses in the light-responsive mice over time. An example of a light-responsive animal is presented in Fig. 4a, where the a- and b-wave amplitudes gradually increased 2 weeks after CiPCs injection, peaking around 4−6 weeks. The light responses of all four light-responsive mice over time are depicted in Fig. 4b. To determine whether the human CiPCs were fixed on the mice retina, we performed Western blot experiments. The results demonstrated that anti-human antibody, Cone-Arrestin had been detected only in CiPCs transplanted mice retina, while the anti-human/mouse antibody, Recoverin, and Rhodopsin, were detected in the retina of untreated mice and CiPCs transplanted mice (Supplementary Fig. S3).

-

The use of embryonic stem cells or hiPSCs for stem cell therapy is a promising approach to restoring vision by replacing lost retinal cells. However, the current protocols employed to generate replacement cells, including photoreceptor cells, ganglion cells, and RPE are time-consuming, limiting their potential clinical use[16−18]. To address this problem, we developed a rapid and reliable two-stage procedure using chemical reprogramming of fibroblasts as the intermediate stage to generate CiPCs from hiPSCs. This two-stage approach enables the production of a large number of CiPCs with a photoreceptor-like morphology and functional characteristics, offering a new perspective in stem cell-based therapies for vision loss.

During the differentiation process, cells changed morphology with time and different reprogramming molecules until a final, stable stage and became CiPCs with photoreceptor-relevant biomarker expression. At this time point, CiPCs were stable and able to be cultured for months.

We further characterized the CiPCs to confirm their properties as photoreceptor cells. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the majority of CiPCs expressed Cone-Arrestin, a major protein in the vision system, recoverin, a photoreceptor-specific calcium-binding protein[19], and rhodopsin, a rod-specific marker[20], indicating their photoreceptor-like characteristics and photosensitivity. Furthermore, CiPCs were found to express Ca2+, K+, and Na+ channels and exhibit the ability to fire action potentials, as evidenced by Ca2+ imaging, and electrophysiological recordings. These findings demonstrate that the hiPSC-derived CiPCs possess the capacity for excitation, which is a critical requirement for vision. Indeed, the ratio of differentiation from hiPSCs to FLCs is very high, almost 100%, while the low ratio of differentiation existed in the stage of FLCs turning to CiPCs, only about 10%. However, the subsequent sorting by flow cytometer had offset the shortage and increased the proportion of available CiPCs to around 90%. The quantification data are supplied in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Since our CiPCs were differentiated from human-source iPSCs, as the restrict comparison, the positive control should use human-source photoreceptors to detect the electric signal with electrophysiology methods. Unfortunately, the human photoreceptor was too rare to obtain. Therefore, we analyzed the electrical signal of CiPCs without negative controls in advance, to confirm that the photoreaction exists in the mature CiPCs. We plan to further investigate the similarity of the photoreaction between CiPCs and human photoreceptors in our future work.

To evaluate the vision-restoring potential of CiPCs, we used a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa induced by i.p. injection of MNU, which is known to cause rapid and specific degeneration of photoreceptors in different animal species including rats, mice, rabbits, and non-human primates. This MNU-induced injury model has been established as a pharmacological model of retinal degeneration[21].

To facilitate translational medicine of CiPC application in human eyes, we attempted CiPCs transplantation without any immunosuppressant. The ocular system was a relatively isolated system from the whole body system. The injected drugs or cells with cytokines had to slowly enter the systemic circulation because of the blood-ocular barrier[22,23]. Without pathogen infection on the ocular surface during the intravitreal injection, the immunogenicity of CiPCs to the eye was not high. We first prepared CiPCs with strict control on quality and transferred them without immunosuppressant if the transplant rejection was not severe. Fortunately, we didn't find any symptoms of rejection or inflammation on the ocular surface throughout the transplantation experiments. Furthermore, we detected the IL-1β and IFN-γ in mice peripheral blood after CiPCs were injected by intravitreal or the tail intravenous method. The results showed that IL-1β and IFN-γ were increased more mildly in the intravitreal injection group, compared to the tail intravenous injection group (Supplementary Fig. S5a). We also detected the microglial response in the retina. Based on the results, microglia were un-activated in healthy retina, but they had been activated in the retina of the MNU-injured model. Therefore, the detection of microglia activation in the CiPCs transplanted model would be inaccurate. Yet, we still found that the microglia did present some more activation, but not a dramatic overreaction in the CiPCs transplanted retina, compared to the MNU-injured retina (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Thus, we had confidence that the CiPCs used in patients should be safer in the future. Before the CiPC-treatment, the MNU-injured mice exhibited minimal light responses in the retina. All control animals did not display any light response throughout the experimental period, while four out of six CiPC-treated animals gradually restored their scotopic light responses over time, indicating a significant rescue of vision loss caused by degenerated retina, without any interference from the mouse immune system. The reason that CiPCs did not work on all animals requires further investigation. One possible explanation was the varying degrees of MNU-induced injury among animals.

ERG recording is a non-invasive method to measure the combined light responses of retinal cells, making it an appropriate tool to monitor the changes in retinal light responses from the same animal over time. In the CiPC-treated mice that restored light sensitivity, the ERG waves gradually increased over time after CiPC injection, reaching a peak approximately 4 weeks after treatment. The response then appeared to plateau, which suggested that the integration of CiPCs into the retina takes a certain amount of time and that the quantity of CiPCs was possibly insufficient to further improve the light responses beyond this point. We also performed Western blotting experiments and confirmed that human sourced photoreceptor marker (Cone-Arrestin) was detected on the mice retina (Supplementary Fig. S3). Combining with the ERG data of mice, we have confidence in obtaining IHC or IF histologic data in our future work.

We do however understand that ERG recording had its limitation that it does not directly equate to vision restoration. Therefore, some functional vision studies, such as optometric response measurement and visual water tasks are necessary for our further investigation.

-

In summary, we have developed a rapid and efficient procedure for differentiating hiPSCs into CiPCs with a desired quantity. To meet the requirement of quantity and quality in a clinical setting, we developed a two-step method for differentiating CiPCs from hiPSCs within 3 weeks using FLCs as an intermediate stage and performed a comprehensive quality control to ensure the purity of CiPCs. The key procedure of quick turnover is using a cocktail medium with multiple small molecules continuously stimulating cells during the culture period. The CiPCs produced using our method expressed recoverin and rhodopsin, as well as functional Ca2+, K+, and Na+ channels, which demonstrated their properties as photoreceptor-like cells. Moreover, our CiPCs were viable in mouse retina without any immunosuppressant and were able to restore photosensitivity in MNU-injury mice, whose photoreceptor cells had been destroyed by MNU treatment. These findings suggest that our hiPSC-derived CiPCs had potential therapeutic applications in the etiological treatment of retinal degenerative diseases and in restoring lost vision.

-

All the feeding and experiment protocols of using animals followed the ARVO Statements for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the animal ethics committee of Jinan University (Approval No. IACUC-20210722-03).

This study involved the use of established human cell lines hiPSCs. The cell lines used in this research were obtained from Codex Biosolution, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and were used in accordance with institutional and national ethical standards. The cell lines have been previously published[24] and no new human tissues were used in this study.

The work was partially supported by Guangdong Grant 'Key Technologies for Treatment of Brain Disorders', China (Grant No. 2018B030332001) (to YX); Guangzhou Key Projects of Brain Science and Brain-Like Intelligence Technology (Grant No. 20200730009) (to YX); Ganzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 2023990085), and Jiangxi Province 'Double Thousand Plan' Innovation Leading Talent Long-term Project (Grant No. S2021CQKJ2297) (to ZX); Guangzhou Huangpu International Science and Technology Collaboration Project (Grant No. 2021GH08) (to HZ).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, experiment supervision, writing - manuscript revision: Xu Y, Zeng H; experiment performed , data collection and analysis, writing - draft manuscript preparation: Xu Z, Liang Y, Zhang S; differentiation of hiPSCs to CiPCs performed: Liu Y, Liu S, Liang S; immunofluorescence results provided for supplementary data: Li Z; animal experiment: Liu Y, Liu S, Liang S, Yang C, Guan T; statistical analysis: Yang C, Guan T, Xu Y, Zeng H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The materials and data used and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. There were no identified potential manufacturers or transaction behaviors observed in the data presented in the article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Zhe Xu, Yuan Liang, Sensen Zhang

- Supplementary Table S1 Quality control checklist of hiPSCs culturing and relevant experiments.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Immunofluorescence images of Recoverin, Rhodopsin, and Cone-Arrestin expression of CiPCs. The undifferentiated hiPSCs were presented as negative controls.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Western blotting (a and c) and Flow cytometry (b) data of subsequent changes of markers, including TRA-1-60, Oct4, CD44, Recoverin, Rhodopsin, and Cone-Arrestin, during the differentiating period.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Western blotting data of Recoverin (anti-human/mouse), Rhodopsin (antihuman/mouse), and Cone-Arrestin (anti-human) expression in mice retina. C: Control group without treatment. M: MNU-induced group. T: Transplanted with CiPCs after MNU-inducing group.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Quantification image of available CiPCs after differentiation and sorting. hiPSCs without any treatment served as the negative control without positive expression of Recoverin, Rhodopsin, and Cone-Arrestin (upper panel). The FLCs determining (mid panel) and CiPCs determining (bottom panel) with the three biomarkers were following the Gating strategy of that used to the negative control.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 ELISA detection of IL-1β and IFN-γ in mice peripheral blood after CiPCs Supplementary Table S1. quality control checklist of hiPSCs culturing and relevant experiments. injected by intravitreal or tail intravenous method (a). WB detection of microglial response (iNOS) in the retina of mice models in different groups (b).

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xu Z, Liang Y, Zhang S, Liu Y, Liu SN, et al. 2025. Immunosuppressant-free photosensitivity rescue of mnu-injured mice using human photoreceptor-like cells induced by rapid chemical reprogramming of fibroblasts as an intermediate stage. Visual Neuroscience 42: e005 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0003

Immunosuppressant-free photosensitivity rescue of mnu-injured mice using human photoreceptor-like cells induced by rapid chemical reprogramming of fibroblasts as an intermediate stage

- Received: 03 November 2024

- Revised: 17 March 2025

- Accepted: 27 March 2025

- Published online: 23 April 2025

Abstract: Recent studies have revealed that photoreceptor-like cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem-cells (hiPSCs) were a potential approach for reversing lost vision. To make the hiPSC application in a clinical setting more accessible and efficient, we have developed a two-step method to differentiate an adequate number of chemically-induced photoreceptor-like cells (CiPCs) cells from hiPSCs in a shorter period (three weeks) through chemical reprogramming. The CiPCs were verified through cell morphology and flow cytometry methods for the expression of photoreceptor markers. The electrical signal detection of calcium, potassium, and sodium channels was performed with an in vitro model to determine the function of CiPCs. ERG recording was utilized for the in vivo evaluation. Photoreceptor markers, including recoverin and rhodopsin, were expressed in the CiPCs. Calcium, potassium, and sodium signals were detected in CiPCs. Clear ERG responses were observed in the retina of four out of six CiPCs transplanted mice (MNU-injured model), while none was observed in the control group. Moreover, classic symptoms of immune rejection were unobserved in the eyes of mice. Consequently, our hiPSC-derived photoreceptor-like cells successfully restored photosensitivity in photoreceptor-degenerated mice, indicating a potential clinical application for etiologically treating retinal degenerative diseases and restoring lost vision with less, or even no need for immunosuppressants.

-

Key words:

- Photoreceptor-like /

- Immunosuppressant /

- Mice /

- Human induced pluripotent stem cells