-

Epoxy resin (EP) plays a vital role in human daily life, which has been employed in different areas of adhesives, coatings, insulation materials, and structural composites for its outstanding chemical resistance, adhesion, high mechanical properties, and electrical insulation[1−6]. However, the highly intrinsic flammability and dense smoke of EP during combustion poses some threats to human safety and property[7−11]. The modification of flame retardancy for EP is imperative and indispensable[12−14]. In this regard, many strategies have been developed to improve flame retardancy of EP composites. Incorporation of flame retardants (FRs) into polymeric matrix is generally one of the most efficient and economical ways to pursue excellent flame retardancy for EP[15,16]. Thus, numerous FRs have been designed to hinder fire hazards of polymers in the past decades[17−21]. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of FRs for the EP matrix are originated from non-renewable petrochemical sources, which goes against the principles of global sustainability and environmental biodegradability. On this account, biological flame retardants have been attracting increasing attention for their inherent renewability, abundance, and biodegradability[22−28].

So far, numerous bio-based FRs have been prepared and investigated for imparting flame retardancy to EP, such as lignin[29], cardanol[30,31], eugenol[32], phytic acid[33−35], itaconic acid[36], resveratrol[37] and cyclodextrin[38,39], and so on. Among them, phytic acid (PA) possesses high flame-retardant efficiency because of its high phosphorus content of 28 wt%. PA is a phosphorus-rich organic acid, derived from the seeds and roots of the plant, which could provide an acid source for intumescent FRs[40,41]. Wang et al.[35] prepared a nano-layered hybrid as a kind of intumescent flame retardant for EP by a neutralization reaction of melamine and PA, and the obtained composites showed both good smoke suppression and flame resistance. Fang et al.[33] improved the flame resistance of EP via synthesizing one unique phosphorus compound by the neutralization of phenyl phosphonate and PA, affecting condensed and gas phases. Zhu et al.[34] synthesized a macromolecule ammonium phytic acid via a neutralization reaction of PA and N-aminoethyl piperazine for reducing smoke emissions and enhancing flame retardancy as a curing agent for EP. However, it is noted that the amines chelated with PA reported in the literature were petroleum-based products, which did not achieve all bio-based FRs.

In this work, a fully biological flame retardant (PA-DAD) was designed via a neutralization reaction between 1,10-diaminodecane (DAD) and PA that from renewable castor oil. The resulting PA-DAD exhibited both favourable smoke suppression and flame retardancy due to the generated bi-phase effect from PA-DAD in EP composites. The existing mechanism of flame retardancy for PA-DAD was explored using SEM-EDS, TG-IR, and Py-GC/MS methods. The transferring for heat and oxygen can be declined by the formed compact char, protecting the residual matrix from additional thermal degradation and decreasing emissions of toxic gases. The mechanical performances of EP/PA-DAD composites with a satisfactory toughness were methodically investigated. PA-DAD was demonstrated as a high-efficient green smoke suppressant as well as flame retardant for EP, expecting to contribute to low-carbon programs.

-

Dicyandiamide (DCD, 98%), Anhydrous ethanol (99.5%), and 2-methylimidazole (2-MI, 98%) all originated from Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Phytic acid aqueous solution (PA, 70wt%) was purchased by Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China) supplied the 1,10-Diaminodecane (DAD, 97%). Anhui Shanfu New Material Technology Co., Ltd (Huangshan, China) supplied solid epoxy resin E12. All reagents were applied with no additional dealing.

Prepared method of PA-DAD

-

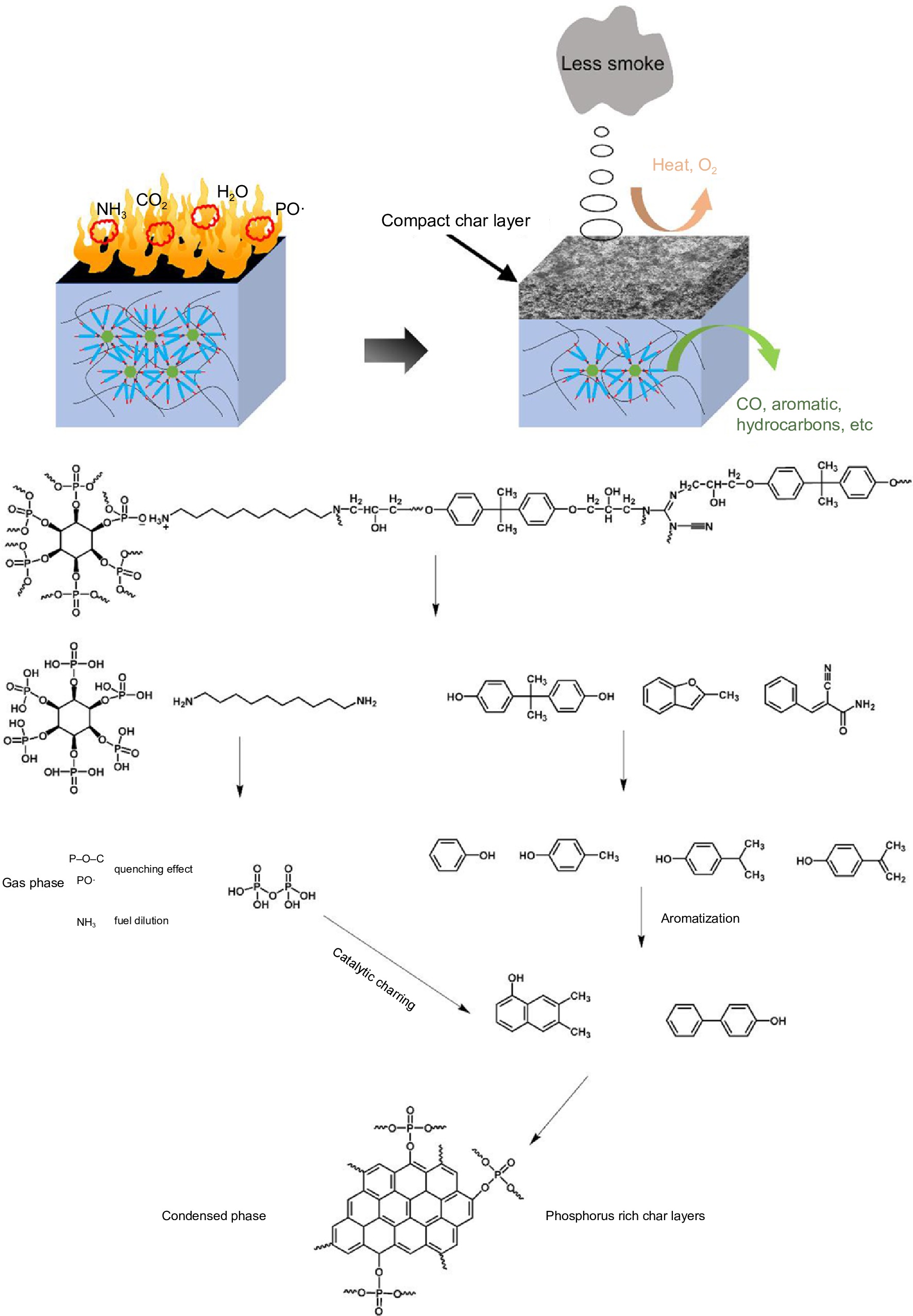

As displayed in Fig. 1a, the PA-DAD was prepared in ethanol-water solution by neutralization reaction. In brief, 18.86 g of PA solution (0.02 mol) and 42.64 g of DAD (0.12 mol) were dissolved into 50 ml of deionized water and 400 ml of anhydrous ethanol, respectively. Then, the PA solution was dropwise added into the stirred DAD solution, yielding in the formation of white precipitate. Subsequently, the final product was acquired by filtration, being washed multiple times by anhydrous ethanol, and dried in a 60 °C vacuum oven for 8 h.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram for the prepared processing of PA-DAD, (b) FTIR spectra of DAD, PA and PA-DAD, (c) 31P NMR curve of PA-DAD and PA, (d) TG curves of PA-DAD.

Fabricated method of EP/PA-DAD composites

-

The different EP/PA-DAD composites were prepared as depicted in the following. The solid epoxy resin E12, along with the prepared PA-DAD, promoter 2-MI and curing agent DCD, were thoroughly mixed using a disintegrator to keep the distribution of mixture uniform. The neutralization reaction occurred at a temperature of 25 °C. The different mixing conditions are displayed in Supplemental Table S1. The above mixture was put in a mold made by stainless steel, and then cured with a press vulcanizer by hot pressing under a pressure of 10 MPa for 25 min at 145 °C. When the temperature was cooled to room temperature, the EP/PA-DAD composites to be used for different tests were obtained.

Characterizations

-

The characterizations employed in this work mainly include: a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (NMR), Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), Raman spectra, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), Thermogravimetry Analysis (TG), Limiting Oxygen Index (LOI), Pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS), a cone calorimeter, the tensile strength, the impact strength, and the flexural strength and so on. The corresponding details of characterizations are supplied in the Supporting Information.

-

The FTIR curves of DAD, PA and PA-DAD were carried out as depicted in Fig. 1b. Regarding PA, the 2,400 cm−1 peak was identified as arising from the (P=O)-OH chemical bond[34]. In the curve of DAD, the 3,329 cm−1 absorption peak corresponded to the stretching vibration of N-H, while the scope for 2,800−3,000 cm−1 was related to C-H bonds[42]. By contrast, the peak assigned to N-H and (P=O)-OH of PA-DAD disappeared. Instead, the new appeared peak of 1,554 cm−1 and 1,075 cm−1 were ascribed to

$ {\text{NH}^+_3} $ $ {\text{PO}^{2-}_3} $ Additionally, the chemical structure of PA-DAD was demonstrated via 31P NMR,1H NMR, and FTIR. As presented in Supplemental Fig. S1a−S1c and Fig. 1c, the signal peak at 4.8 ppm in all spectra were ascribed to the deuterated water. In the context of PA, two distinct peaks appeared at approximately 4 ppm in the spectrum. Concerning DAD, peaks at 2.5, 1.4, and 1.2 ppm were related to the -CH2- protons in various chemical environments. When it comes to PA-DAD, the two peaks at 2.5 and 1.4 ppm exhibited a noticeable shift towards the left, indicating that a neutralization reaction occurred between DAD and PA. Moreover, in the spectra of 31P NMR, as depicted in Fig. 1b, the signal of phosphorus shifted from −0.32 ppm of PA to 1.47 ppm of PA-DAD.

The thermal-degradation behaviors of PA-DAD are also shown in Fig. 1d and Supplemental Table 2. The process of thermal degradation for PA-DAD involved two primary stages, with the temperatures of maximum weight loss rates recorded at 227 and 399 °C. The initial degradation stage can be attributed to and the dehydration reaction from phytic acid, and the destruction of ionic bonds within PA-DAD[44]. The second degradation stage was associated with the releasing of NH3, H2O, and also the generated poly-/pyro-/ultra-phosphoric acids as PA-DAD further decomposed[40,45].

Curing and thermal properties

-

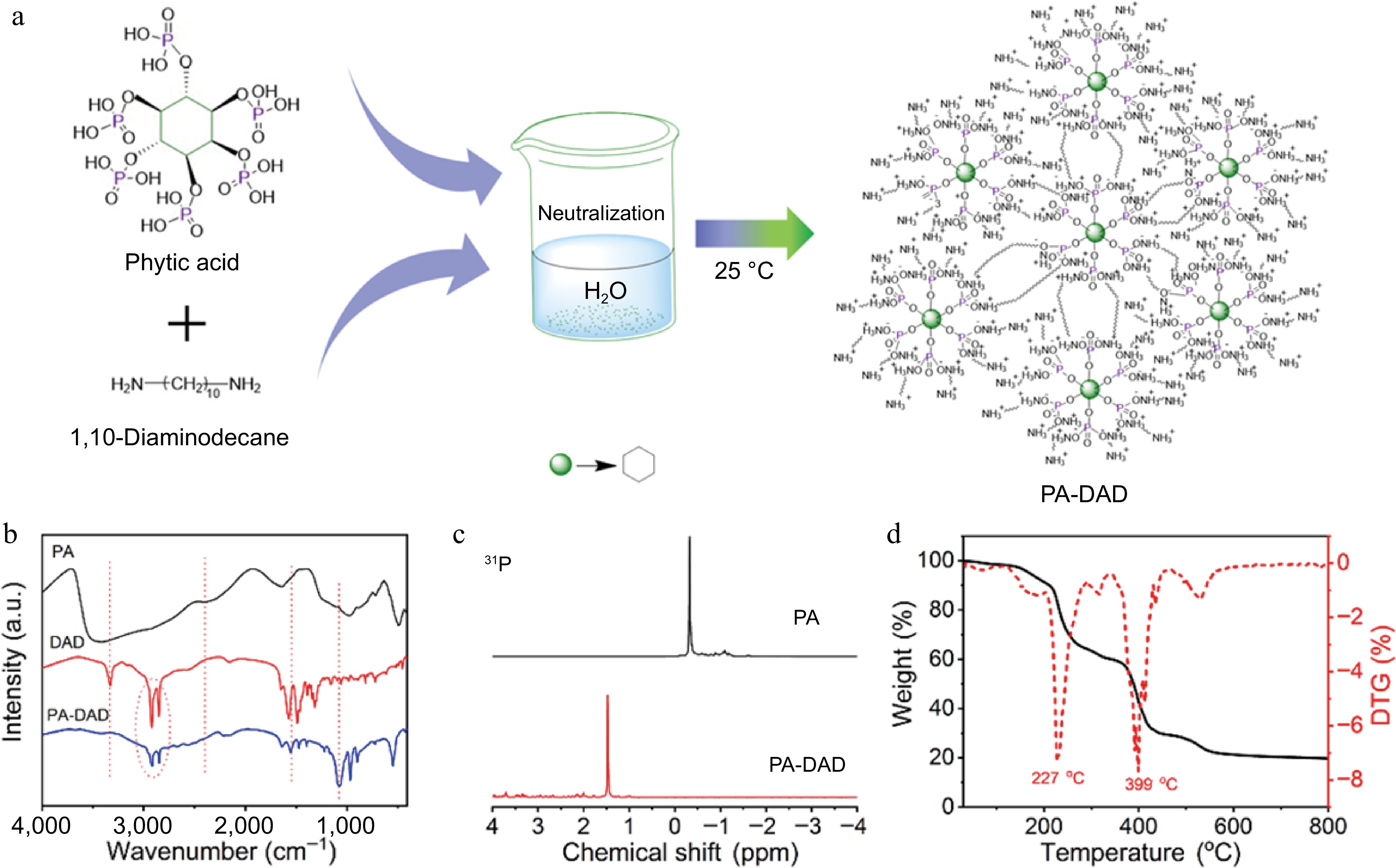

The curing behaviour from effects of PA-DAD on EP for was explored via non isothermal DSC testing. Supplemental Fig. S2a−S2d displayed the DSC curves of EP/PA-DAD composites with different heating rates of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 °C min−1 separately. As the heating rate increased, the temperatures of the initial peaks were elevated, and the range of curing temperature became broader because of the intensified thermal effects per unit time[46]. The reaction activation energy (Ea) had been calculated from Kissinger and Ozawa equation, as shown in Fig. 2a &b and as well summarized in Supplemental Table S3. The Ea increased significantly when the PA-DAD was incorporated into the EP. The increased presence of active sites, stemming from the amino group of PA-DAD, needed higher energy to be input for chemical reactions during the initial stages of curing. Consequently, compared to pure EP, the EP/PA-DAD systems required higher curing temperatures.

Figure 2.

The calculated results of (a) Kissinger, and (b) Ozawa methods for neat EP and its different composites, (c) TG and (d) DTG curves for EP composites.

The behaviors of thermal degradation from EP/PA-DAD composites were inspected via TG with a nitrogen atmosphere in Fig. 2c & d, and related data were summarized in Supplemental Table S2. The residual mass for EP composites was improved after imparting the PA-DAD. The yields of char for neat EP, EP/10% PA-DAD, EP/20% PA-DAD, and EP/25% PA-DAD composites increased from 11.1% (for neat EP) to 13.6%, 17.1%, and 17.2% at 800 °C, respectively. A higher residual mass indicated an optimistic impact on high flame resistance of composites. Compared with neat EP, the Tonset (the temperature at 5 wt% mass loss) and Tmax (the maximum degradation temperature) of EP/PA-DAD decreased continuously as the increased addition amount of PA-DAD. The initial thermal decomposition of EP/PA-DAD primarily resulted from the premature breakdown of PA-DAD. Consequently, PA-DAD can be decomposed as poly-/pyro-/ultra-phosphoric acids at lower temperatures, accelerating the decomposition of EP matrix. The generated poly-/pyro-/ultra-phosphoric acids facilitated crosslinking reactions and catalyzed the carbonization of EP molecules. The process could lead to the formatting for a protective and stable char layer during high-temperature stages. The protective layer significantly enhanced the fire retardancy for EP composites during combustion, providing a safeguard for the underlying matrix[47,48].

Flame retardancy for EP composites

-

Both LOI values as well as the UL-94 rating were initially employed to assess the flame retardancy for EP composites, and corresponding data and results are summarized in Table 1. Neat EP, which is inherently flammable, exhibited a quite low LOI value of 20.4% and did not meet V-0 rating in the test of UL-94. Upon adding PA-DAD into EP, there were significant increases in LOI values of EP composites. When the content of PA-DAD reached 25 wt%, a notably high LOI value with 28.0% for the EP/25% PA-DAD composite was achieved and successfully satisfied V-0 rating in the test of UL-94 (as indicated in Supplemental Fig. S3). The above findings demonstrated that PA-DAD served as an efficient biological flame retardant for EP, enhancing fire resistance of composites.

Table 1. Detailed results corresponding to UL-94 and LOI for EP composites.

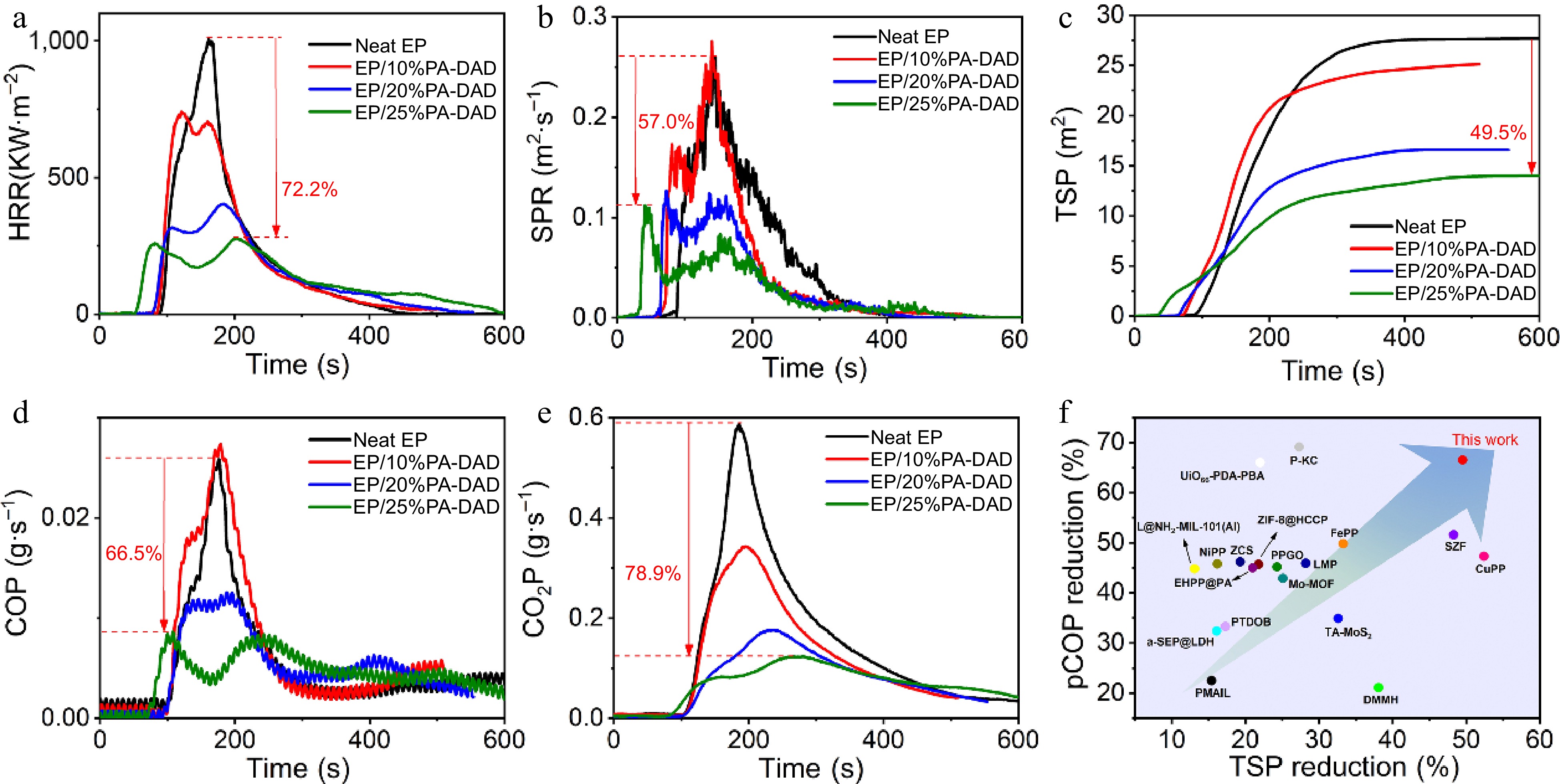

Sample UL-94 LOI (%) Rating Dripping t1/t2(s) Neat EP NR YES > 30 20.4 EP/10%PA-DAD NR NO > 30 23.6 EP/20%PA-DAD V-1 NO 8.0/2.4 25.3 EP/25%PA-DAD V-0 NO 1.1/0.9 28.0 Cone calorimetry tests were performed to assess the actual fire performance for EP composites, and the associated results are reviewed in Table 2. EP/PA-DAD composites' time to ignition (TTI) was found to be shorter than that for pure EP. Because an earlier decomposition for PA-DAD would form a stable, and protective char layer, keeping the EP matrix from further thermal degradation. As depicted in Fig. 3a, the highly flammable EP would burn out rapidly after ignition, and its peak heat release rate (pHRR) was 1,007 kW/m2. Reversely, after introducing 25 wt% PA-DAD to EP, the pHRR of the composites has been reduced to 280 kW/m2, decreasing by 72.2% than that of neat EP. Moreover, as shown in Supplemental Fig. S4, the total heat release (THR) reduced significantly from 99.2 MJ/m2 of pure EP to 71.2 MJ/m2 of EP/25% PA-DAD, which had decreased by 28.3%. Besides, the rate of fire growth (FIGRA) was the ratio between pHRR and TpHRR (time to pHRR) according to the HRR curves to evaluate the actual fire hazard for material qualitatively[49,50]. The FIGRA value (1.38 kW/m2·s) of EP/25% PA-DAD was 77.8% lower than that of neat EP with 6.21 kW/m2·s, underscoring the superior fire safety enhancement achieved by PA-DAD in the EP composites. Additionally, the smoke released during combustion was generally recognized as another critical factor in evaluating the fire retardancy of the material. In Fig. 3b & c, the total smoke product (TSP) and peak of smoke product rate (pSPR) values of EP/PA-DAD composites were inhibited significantly. The values of THR and pHRR for the EP/25% PA-DAD composite experienced noteworthy reductions of 49.5% and 57.0%, respectively, in contrast with neat EP. In detail, as presented in Fig. 3d & e, the peak of CO production named pCOP, and the peak of CO2 production named pCO2P for EP/25% PA-DAD decreased by 66.5%, and 78.9%, respectively. In the event of a fire, fatalities can occur due to suffocation when the concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), and carbon monoxide (CO) in the surrounding air reach critical levels. Thus, the introduced PA-DAD to EP dramatically improved the fire safety and provided more escaped time for people. Moreover, lower production of CO and CO2 disclosed the more carbon fixed char residue during combustion, contributing to exert condensed phase effect for flame-retardant mechanism. To underscore the superior attributes of the newly formulated PA-DAD, the TSP reduction, pCOP reduction of PA-DAD and previously reported flame retardant for EP are displayed in Fig. 3f. The detailed fire performances are also summarized as in Supplemental Table S4. The biological PA-DAD in this work showed a significant reduction of TSP and pCOP than those of previous reported FRs.

Table 2. Data from Cone calorimeter for EP and its composites.

Samples TTI

(s)TPHRR

(s)pHRR

(kW/m2)THR

(MJ/m2)pSPR

(m2/s)TSP

(m2)pCOP

(g/s)pCO2P

(g/s)FIGRA

(kW/m2·s)Neat EP 86 ± 3 162 ± 5 1007 ± 32 99.2 ± 1.9 0.26 ± 0.010 27.7 ± 2.1 0.0258 ± 0.0007 0.586 ± 0.013 6.21 EP/10% PA-DAD 71 ± 2 121 ± 4 740 ± 26 96.1 ± 2.1 0.28 ± 0.012 25.1 ± 1.7 0.0274 ± 0.0006 0.343 ± 0.009 6.12 EP/20% PA-DAD 63 ± 2 184 ± 4 403 ± 24 71.9 ± 0.7 0.12 ± 0.006 16.6 ± 0.9 0.0125 ± 0.0005 0.176 ± 0.007 2.19 EP/25% PA-DAD 34 ± 1 203 ± 3 280 ± 19 71.2 ± 0.9 0.11 ± 0.007 14.0 ± 1.1 0.0086 ± 0.0003 0.124 ± 0.008 1.38

Figure 3.

(a) HRR, (b) SPR, (c) TSP, (d) COP, (e) CO2P curves vs time for EP composites under a flux with 35 kW/m2, and (f) the TSP reduction vs pCOP reduction of PA-DAD compared with other works.

Flame-retardant mechanism

-

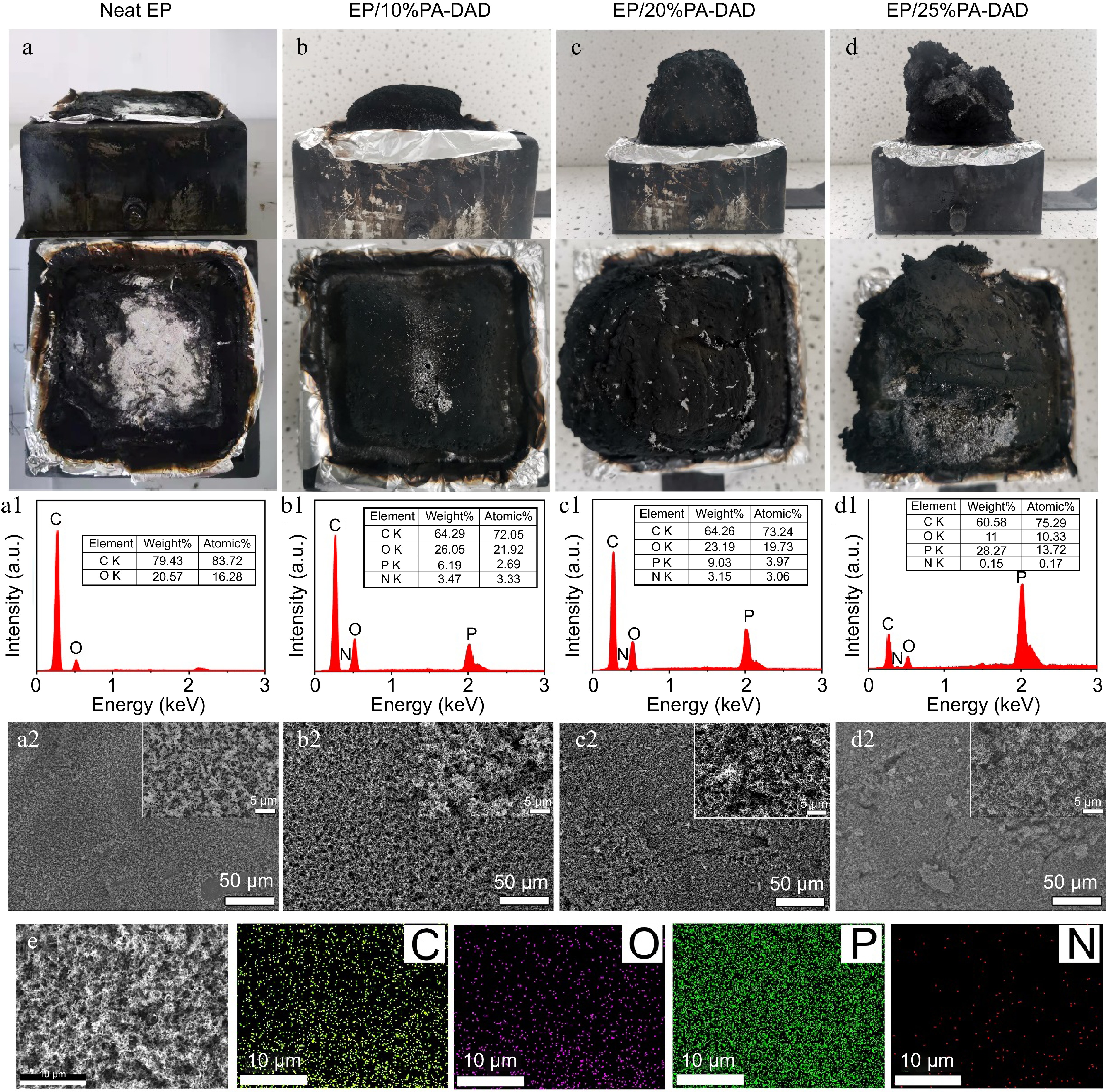

To disclose the mechanisms from flame retardants within EP matrix, the char residues of EP composites from cone calorimetry were further studied. As displayed in Fig. 4, the digital photos indicated that EP/PA-DAD composites had a dense and intumescent carbon layer. With an increasing loading of PA-DAD, the volumes of residues increased as well expanded gradually. The dense and intumescent carbon layer provided a desired shield to reduce the heat and mass transferring between condensed and gas phases. SEM-EDS was applied to evaluate the quality of char residues. As depicted in Fig. 4a1−d1 & 4e, there were four elements including C, O, N and P in the char residues of EP/PA-DAD composites. And P content of the char layer was increased gradually with the increased loading of PA-DAD. The element P was introduced by PA-DAD, accelerating the catalysis and carbonization for EP to produce a good char layer in dense, continuous, and phosphorous-containing. Thus, the char layers of EP/PA-DAD composites in Fig. 4a2−d2 were relatively compact compared with neat EP, enhancing the flame retardancy via condensed phase.

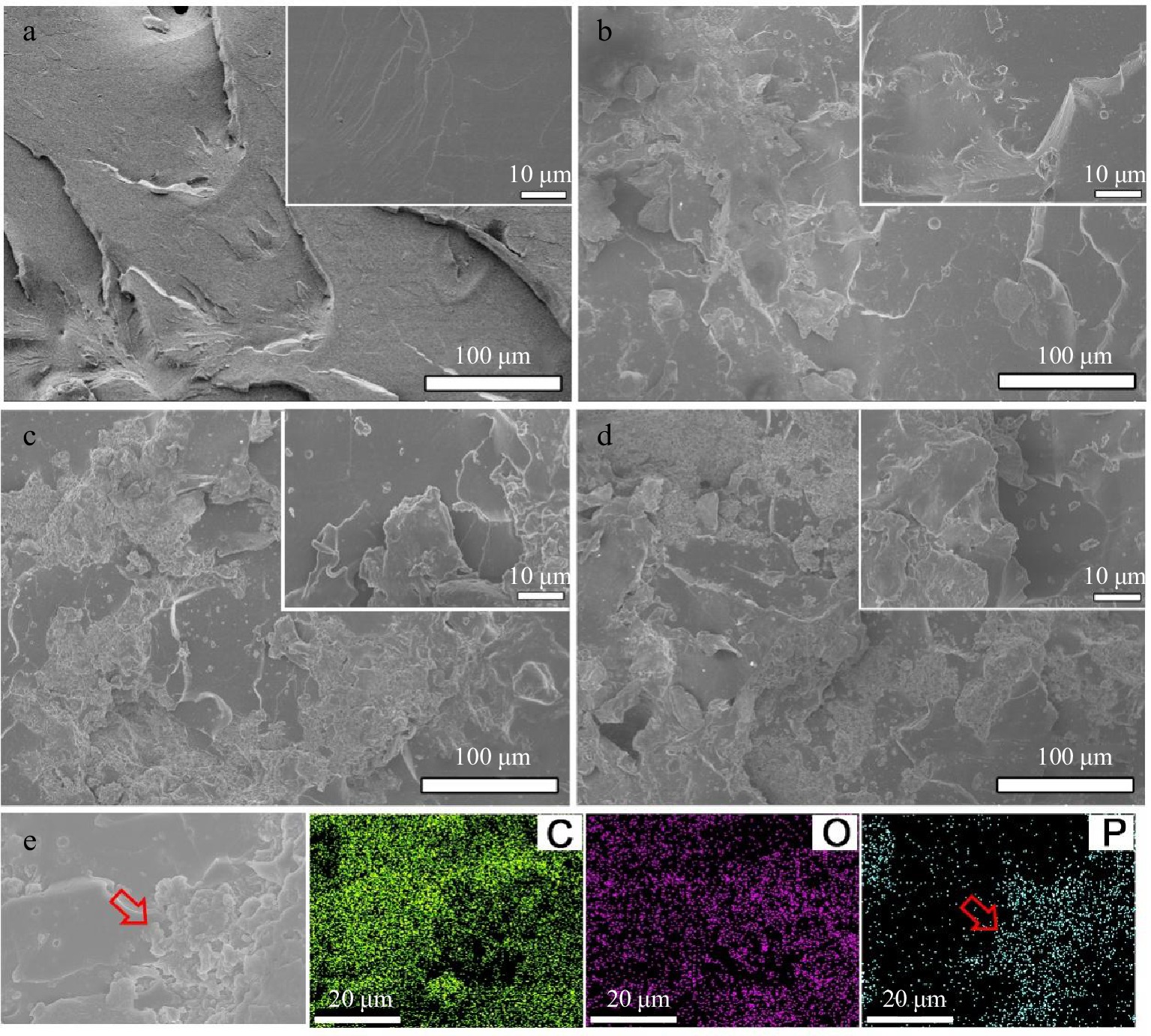

Figure 4.

Digital photos of residual chars from cone calorimetry for (a) neat EP, (b) EP/10% PA-DAD, (c) EP/20% PA-DAD, (d) EP/25% PA-DAD. (a1)−(d1) EDS results and (a2)−(d2) SEM photos for corresponding residue char. (e) The images of elemental mapping for residue chars of EP/25% PA-DAD.

The compositions of char residues were also analyzed by FTIR methods. In Supplemental Fig. S5a, the absorption peaks at around 1,618, and 2,852−2,958 cm−1 were related to C=C, and C-H' stretching vibration from CH2 group, respectively[33,43]. For EP/25% PA-DAD, a new 1,160 cm−1 absorption peak indicated the presence of P-O bonds in compound. Two typical peaks of G band at 1,580 cm−1 and D band at 1,350 cm−1 were presented in Raman spectra of char residues for EP and EP/25% PA-DAD composite, which corresponded to graphite char and the disordered char, respectively (see Supplemental Fig. S5b)[51]. The value of ID/IG for EP/25% PA-DAD char was 1.11, higher than that of char from neat EP (0.89), suggesting a smaller microstructure size that enhances fire resistance[52]. As displayed in Supplemental Fig. S5c, the composition of elements from the surface of EP/25% PA-DAD char was analyzed by XPS. The elements including C, N, O, and P existed in the chemical structure of EP/25% PA-DAD char, which was consistent with the results of EDS characterization. The high-solution of elements was shown in Supplemental Fig. S6a−S6d. Three peaks of C-C in aliphatic and aromatic species at 284.5 eV, C=O at 288.5 eV, and C-O in ether and/or hydroxyl group at 286.0 eV were deconvoluted from C1s spectra. In the high-solution O1s, three kinds of oxygen configurations appear at 535.1, 532.1 and 530.4 eV, corresponding to -COOH, -O- of C-O-C or C-O-P and =O from phosphate or carbonyl groups, respectively. The N1s spectra could be divided into two peaks of 400.2 and 399.2 eV, assigning to nitrogen functionality in the pyrrolic group and oxidized nitrogen compounds[53,54]. The only 133.5 eV peak from P2p spectra was ascribed to pyrophosphate and polyphosphate. The results of XPS demonstrated that poly-/pyro-/ultra-phosphoric acids were generated while the combustion occurred, forming a strong char layer via dehydration and esterification of EP.

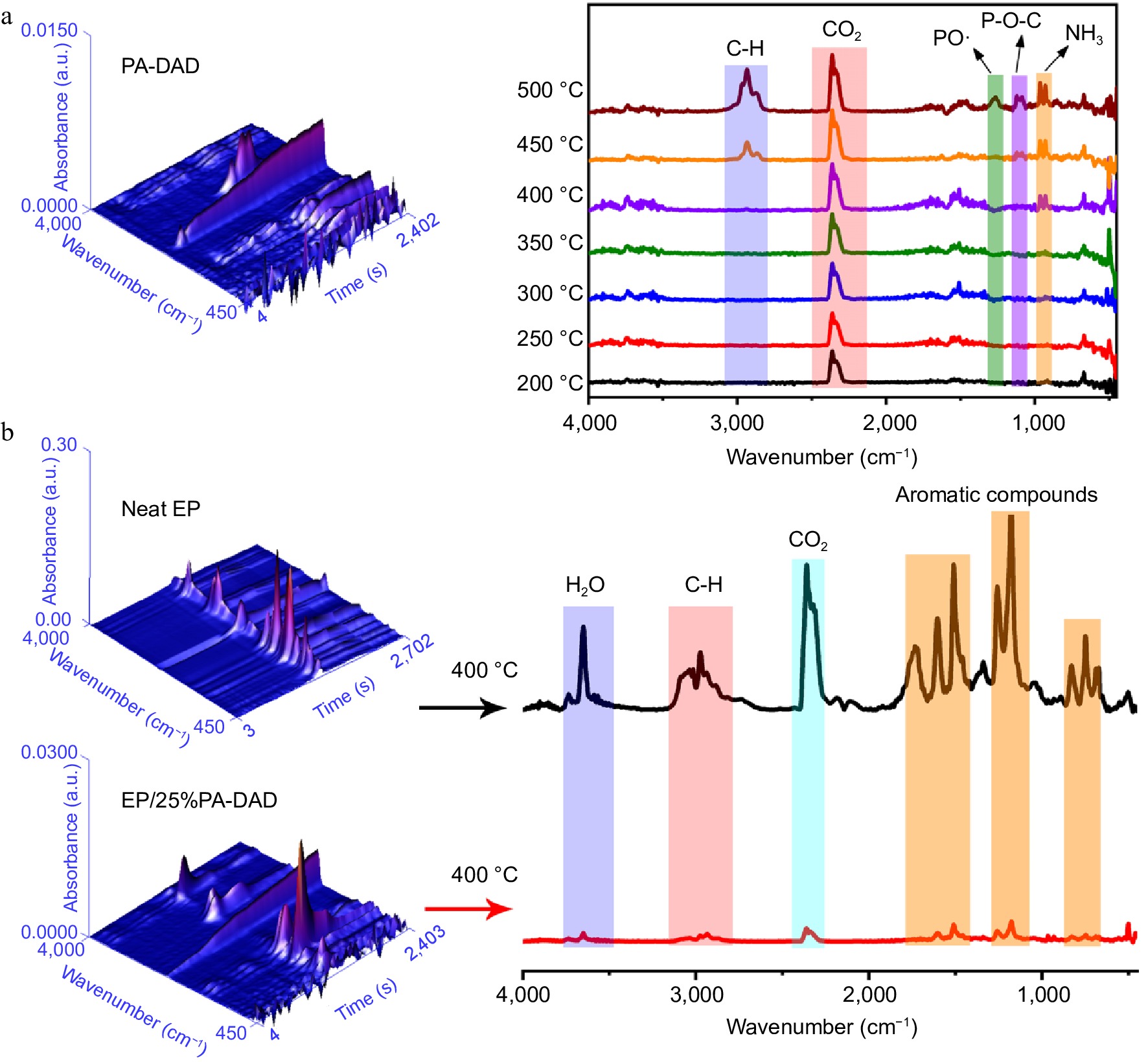

The TG-IR was carried out to explore the pyrolysis products of PA-DAD, pure EP and EP/25%PA-DAD composite under a heating rate with 20 °C/min and N2 atmosphere. Figure 5a showed the FTIR 3D and 2D for decomposed fragments from PA-DAD at 200−500 °C when thermal degradation. The primary gaseous products of PA-DAD were hydrocarbons at 2970 cm−1, CO2 at 2360 cm−1, PO· at 1258 cm−1, P-O-C at 1097 cm−1 and NH3 at both 965 and 930 cm−1. The fragments with P-O-C and PO· were demonstrated by a strong signal at 450−500 °C, being cable of quenching active radicals with OH· and H· during burning, thereby suppressing the combustion. The absorption peak for NH3 was displayed between 400−500 °C, which contributed to the dilution of flue gases and a reduction in the rate of burning. In Fig. 5b, both neat EP and EP/25% PA-DAD displayed the analogous characteristic peaks from gaseous products when degradation, such as aromatic compounds at 1,605, 1,510, 834 and 689 cm−1, hydrocarbons at 2,800−3,000 cm−1, CO2 at 2,360 cm−1, H2O at 3,600−4,000 cm−1.

Figure 5.

(a) FTIR 3D and 2D spectra from pyrolysis products for PA-DAD. (b) FTIR 3D and 2D spectra from the pyrolysis products for pure EP and EP/25% PA-DAD with the maximum rate of decomposition.

Nevertheless, the EP/25% PA-DAD showed the weaker peak intensities compared with pure EP, indicating the incorporation for PA-DAD could obstacle some productions of volatiles effectively during burning. In addition, the curves of total volatile gas intensity versus temperatures, and the Gram-Schmidt (GS) curves for pure EP and EP/25% PA-DAD composite are depicted in Supplemental Fig. S7. The EP/25% PA-DAD composite' intensities of pyrolytic products were lower than that of neat EP consistently. Some reasons for the dramatical reduction of volatile pyrolysis products from EP/25% PA-DAD are as follows. At the beginning of combustion, the earlier thermal decomposition for PA-DAD could lead to the carbonization layers with nano-scale, acting as a block to inhibit the transferring of heat and mass. When combustion continues, the PA-DAD generated poly-/pyro-/ultra-phosphoric acids for catalyzing the degradation of EP, forming intumescent and compact char for protecting the matrix from further thermal degradation.

Pyrolysis behaviors

-

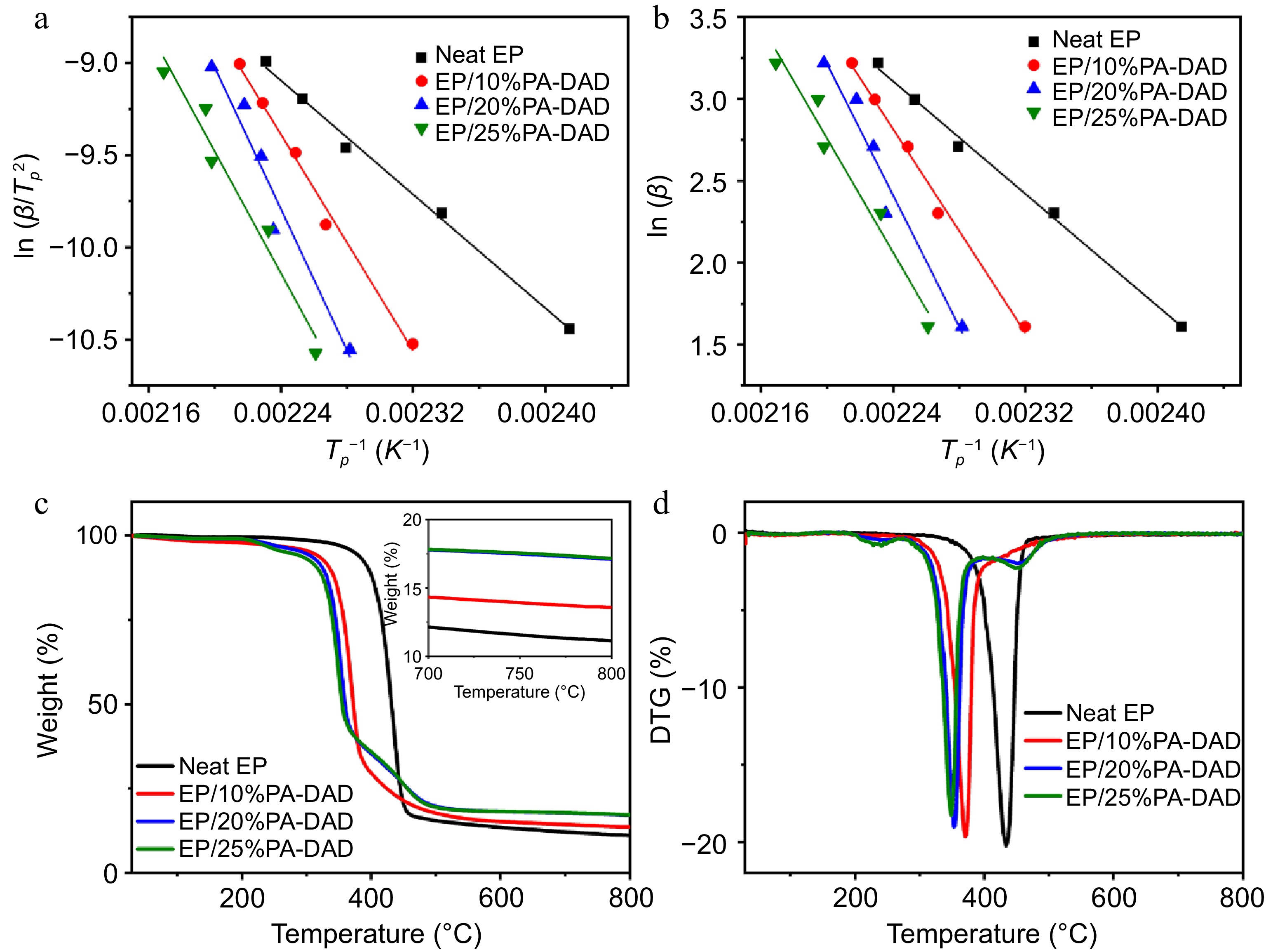

The pyrolysis products obtained from EP/PA-DAD composites were investigated by the method of Py-GC/MS further. The main pyrolysis products from the pyrogram (in Supplemental Fig. S8) for EP/25% PA-DAD, were also listed in Supplemental Table S5. The 2, 3, 5, 6, and 10 peaks in the pyrogram were attributed to phenol, p-Cresol, 4-isopropyl phenol, 4-isopropenylphenol, and 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) propane. The aforementioned substances stemmed from the reactions involving the opening of aromatic rings and the subsequent rearrangement reactions of the bisphenol A chains. The nitrogen-containing compounds of (E)-Alpha-cyanocinnamamide at peak 8, have the capacity to decompose into non-flammable, small-molecule gas NH3. Above decomposition process effectively reduced the concentration of the flammable gases[55]. The detailed pyrolysis routes and speculative flame-retardant mechanism for EP/25% PA-DAD are shown in Fig. 6. During the burning process, the decomposition of PA-DAD can yield products with P-O-C, PO·, and NH3, thereby capturing the active radicals of H·, OH· and decreasing the flammable gases. When combustion continues, the residual phosphorus from condensed generated the poly-/pyro-/ultra-phosphoric acids, catalyzing the degradation of EP for promoting the producing of the intumescent and compact chars. Herein, the formation of intumescent and compact chars reduced the oxygen, and toxic gas emissions to prevent the matrix from continuously degrading. Thus, the above results about incorporated PA-DAD further demonstrate the excellent flame retardancy and enhanced residual char of composites.

Mechanical properties

-

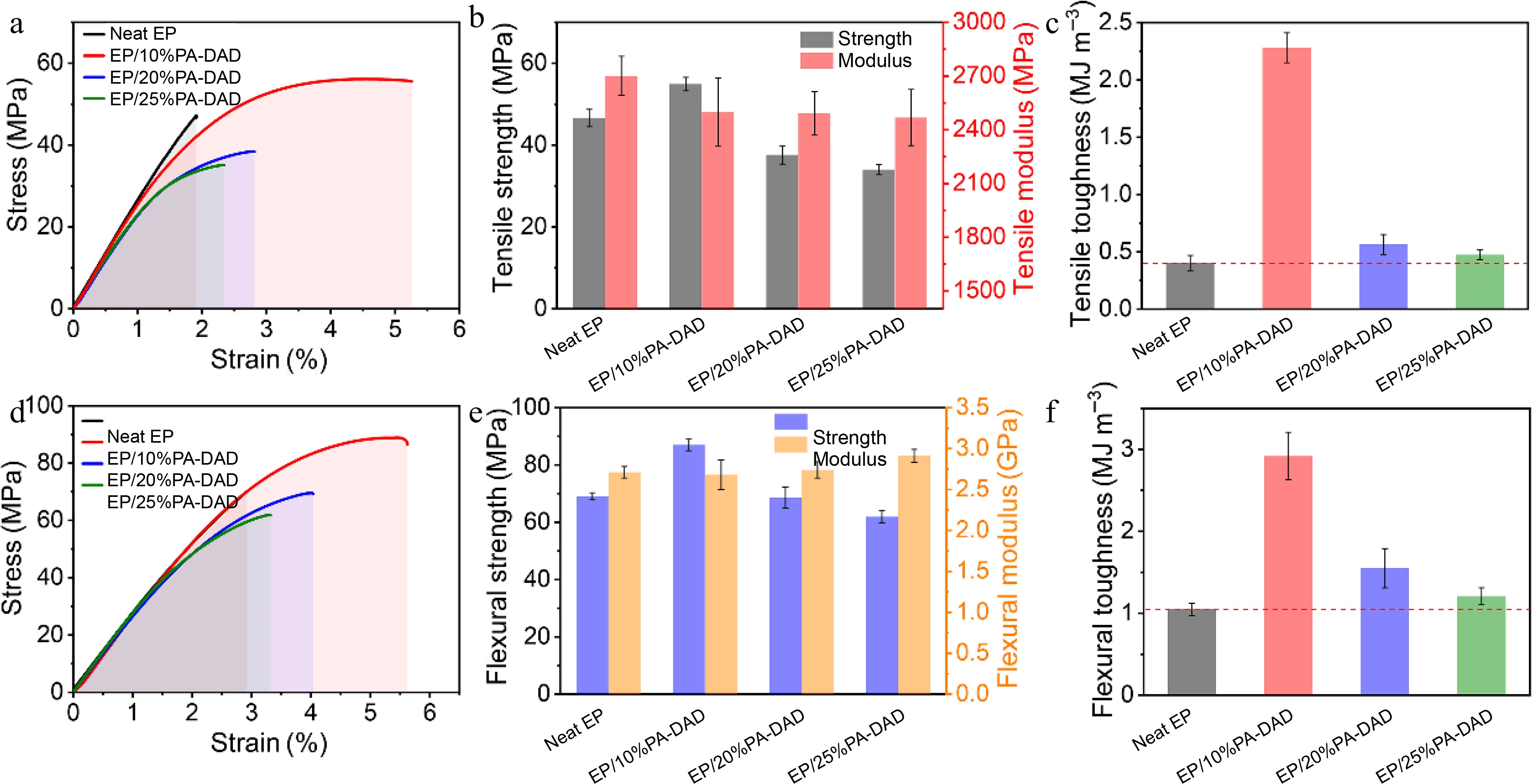

Mechanical performances including the tensile, flexural and impact strength for neat EP as well EP/PA-DAD composites are displayed in Figs. 7 & 8. The above relatively detailed data are reviewed in Supplemental Table S6. In Fig. 7a & d, the typical strain-stress for neat EP and its corresponding composites are presented. As demonstrated in Fig. 7c & f, the toughness values of pure EP and its corresponding composites were calculated by the integration values from stress-strain curves[56,57]. Obviously, the tensile, flexural strength and toughness were firstly increased and then decreased with the increasing contents of PA-DAD. Partial increased modulus can be attributed to the capacity of PA-DAD to enhance crosslink density. The increased toughness was assigned to the ion bonds formed by PA-DAD, which have the effect on dissipating energy[12,58]. The partial agglomeration of PA-DAD will be caused after the added amount reaches a certain level, leading to a noticeable decline in mechanical properties of EP composites[44].

Figure 7.

(a) Tensile stress-strain curves, (b) tensile strength and modulus, (c) tensile toughness, (d) flexural stress-strain curves (e) flexural strength, (f) flexural toughness for EP and its corresponding composites.

Figure 8.

SEM images from the fractured surfaces of tensile samples for (a) neat EP, (b) EP/10% PA-DAD, (c) EP/20% PA-DAD, and (d) EP/25% PA-DAD. (e) EDS mapping photograph of tensile fractured surfaces for EP/25% PA-DAD.

The PA-DAD were agglomerated in the EP matrix as seen in the tensile fracture when the addition reached 25 wt% (see Fig. 8). The mapping photograph also proved the phosphorus agglomeration in the fracture. When the PA-DAD loading was 10 wt%, the tensile, and flexural strength of composites owned higher values compared with neat EP, which were 17.8% and 26.0% respectively. In particular, the tensile, and flexural toughness were greatly enhanced by 466% and 178% compared with neat EP. When PA-DAD loading reached 20 wt% and 25 wt%, although the tensile, and flexural strength of EP/PA-DAD composites exhibited lower values, the tensile, and flexural toughness still higher than those of neat EP. Some agglomerations caused by the relatively high filler contents led to the tensile and flexural strength decreased, but the ion bonds formed by PA-DAD have the function of dissipating energy for increasing tensile and flexural toughness. In comparison with neat EP, the impact strength (Supplemental Table S6) of EP/10% PA-DAD, EP/20% PA-DAD, and EP/25% PA-DAD were enhanced to 14.61, 13.00 and 8.53 KJ·m−2, and were also enhanced by 99.0%, 77.1%, and 16.2%, respectively.

-

In conclusion, a fully biological flame retardant named PA-DAD has been successfully prepared through a straightforward neutralization reaction of DAD and PA. When the content of PA-DAD achieved 25 wt%, LOI value for EP/25% PA-DAD composite reached up to 28.0%, and also satisfied a V-0 rating of the UL-94 test. In comparison with neat EP, the EP/25% PA-DAD displayed dramatic reductions in pHRR (72.2%), pSPR (57.0%), THR (28.3%), TSP (49.5%) and FIGRA (77.8%). The imparting of PA-DAD can also inhibit the production of volatiles sufficiently. The synergy between condensed and gas phase contributed to the outstanding flame retardancy from EP/ PA-DAD composites, beneficial to proposed flame retardant mechanisms. For the condensed phases, PA-DAD generated poly-/pyro-/ultra-phosphoric acids and facilitated the production of a protective char shield to insulate the transferring of heat and mass. While in the gas phases, the PA-DAD released the PO·, P-O-C, and NH3 and then quenched the active radicals of H· and OH·. The mechanical performances for EP composites have been enhanced to certain degrees after adding the flame retardant of PA-DAD. Our work supplied a friendly and facile approach for preparing biological flame retardant and smoke suppressant materials for high fire-safety required EP composites.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lin Z, Zhang W, Dai J; data collection: Lin Z, Zhang W, Lou G, Bai Z; analysis and interpretation of results: Lou G, Bai Z, Xu J, Li H, Zong Y, Chen F, Song P, Liu L, Dai J; draft manuscript preparation: Lin Z, Lou G, Chen F, Dai J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LY21E030001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51903222), National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of China (No. 202210341055), the 'Leading geese' projects of Zhejiang Provincial Department of Science and Technology (No. 2022C03128), and the College Student Science and Technology Innovation Activity Plan of Zhejiang Province (No. 2023R412019).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

These authors contributed equally: Zhiqian Lin, Wangbin Zhang

- Supplemental Table S1 The Various Proportions of the Epoxy Resin Systems.

- Supplemental Table S2 TGA data of PA-DAD and EP composites.

- Supplemental Table S3 Kinetic parameters of the curing reaction.

- Supplemental Table S4 The fire performances of PA-DAD.

- Supplemental Table S5 Structural assignments for the main fragments observed in the Py-GC/MS of EP/25 %PA-DAD.

- Supplemental Table S6 Mechanical properties of neat EP and EP composites.

- Supplemental Fig. S1 1H NMR spectra of (a) PA, (b) DAD, and (c) PA-DAD.

- Supplemental Fig. S2 The DSC curves of (a) neat EP, (b) EP/10% PA-DAD, (c) EP/20% PA-DAD, (d) EP/25% PA-DAD at different heating rates and the fitting curves based on Kissinger, and Ozawa methods for neat EP and EP composites.

- Supplemental Fig. S3 The UL-94 test for neat EP and EP composites.

- Supplemental Fig. S4 The THR curves vs time for EP composites at a flux of 35 kW/m2.

- Supplemental Fig. S5 (a) FTIR spectrogram of the composition of residual char; (b) Raman spectrogram of the composition of residual char; (c)XPS spectrogram of the composition of residual char.

- Supplemental Fig. S6 (a)The C1s spectra of the composition of residual char; (b) The O1s spectra of the composition of residual char; (c) The N1s spectra of the composition of residual char; (d) The P2p spectra of the composition of residual char.

- Supplemental Fig. S7 (a) The Gram-Schmidt curves of neat EP and EP/25% PA-DAD; (b) The intensity of hydrocarbons versus the temperature curves of neat EP and EP/25% PA-DAD; (c) The intensity of CO2 versus the temperature curves of neat EP and EP/25% PA-DAD; (d) The intensity of CO versus the temperature curves of neat EP and EP/25% PA-DAD; (e) The intensity of carbonyl compounds versus the temperature curves of neat EP and EP/25% PA-DAD; (f) The intensity of aromatic compounds versus the temperature curves of neat EP and EP/25% PA-DAD.

- Supplemental Fig. S8 Py-GC/MS spectra of EP/25% PA-DAD.

- Supporting Information Details of characterizations.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lin Z, Zhang W, Lou G, Bai Z, Xu J, et al. 2023. A bio-based hyperbranched flame retardant towards the fire-safety and smoke-suppression epoxy composite. Emergency Management Science and Technology 3:21 doi: 10.48130/EMST-2023-0021

A bio-based hyperbranched flame retardant towards the fire-safety and smoke-suppression epoxy composite

- Received: 17 October 2023

- Accepted: 12 December 2023

- Published online: 26 December 2023

Abstract: The design of fully biological flame retardants is vital for environment-friendly and sustainability development. Herein, a fully biological hyperbranched flame retardant named PA-DAD was synthesized successfully through a simple neutralization reaction between 1,10-Diaminodecane (DAD) and phytic acid (PA). PA-DAD as a kind of reactive flame retardant was subsequently employed to composite with epoxy resin (EP). The obtained EP composite, comprising 25 wt% PA-DAD, exhibited excellent flame resistance with an appreciative limiting oxygen index (LOI) of 28.0%, and a desired V-0 rating of UL-94. The favorable attributes stem from the evident flame-retardant characteristics of PA-DAD, manifesting particularly within the gaseous and condensed phases of combustion. Benefitting from the PA-DAD with the synergetic effect of smoke suppression and flame resistance, the EP/25% PA-DAD composite displayed highlighted reductions both in smoke production and heat release rate. In contrast with neat EP, total smoke production (TSP), peak smoke production release (pSPR), the peak heat release rate (pHRR), and the rate of fire growth (FIGRA) of the EP/25% PA-DAD composite were decreased by 49.5%, 57.0%, 72.2% and 77.8%, respectively. Moreover, the EP/25% PA-DAD composite resulted in well-preserved mechanical properties, especially enhanced toughness, compared with the neat EP. The strategies in our work provided a facile, green, and highly efficient way for fabricating high fire-retardant EP composites.