-

Salinization of soil poses a major threat to crop growth, development, and productivity, affecting approximately one billion square kilometers of land globally[1,2]. Due to global climate change, land clearance, and overfertilization, the extent of salt-affected land continues to grow[3]. Furthermore, the excessive use of irrigation and fertilizer in crop production has led to secondary soil salinization, which is an escalating threat to worldwide sustainable agriculture[4−6]. High salinity in soil generally leads to an over-accumulation of Na+ ions, which in turn disrupts vital metabolic and physiological processes in plants[7]. Salt stress also stimulates the overproduction and buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in oxidative damage and membrane lipid peroxidation[8]. To cope with the high salinity environment, the crops developed diverse strategies to maintain a balance between plant growth and stress adaptation, such as regulating osmotic pressure, ion exclusion and compartmentalization, activating ROS scavenging pathways, and metabolic reprogramming[9,10]. Several ion transport-related genes such as Salt Overly Sensitive 1 (SOS1), SOS2, high-affinity K+ transporter 1 (HKT1), high-affinity K+ transporter 5 (HAK5), and Na+/H+ antiporter 1 (NHX1) are responsible for maintaining the balance between Na+ and K+ ions[11−15]. The antioxidant system is triggered to reduce ROS buildup, engaging both non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidants in redox processes[16].

Carbon and nitrogen are the most fundamental elements, constituting nearly all substances within plants. Carbon and nitrogen metabolism serves as the primary route for the synthesis of carbohydrates and proteins and plays a crucial role in plant responses to salt stress[17]. Nitrogen is an essential component of chlorophylls and plant hormones, and thus, it acts as a critical factor in determining crop productivity[18]. Plants absorb inorganic nitrogen from the soil through their roots, mainly as nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+), via nitrate transporters (NRTs) and ammonium transporters (AMTs), respectively[19,20]. Under the catalysis of nitrate reductase (NR) and nitrite reductase (NiR), NO3− is converted to NH4+, which is then transformed into glutamine by the glutamine synthetase (GS)-glutamine-2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT) cycle, along with NH4+ directly absorbed from the soil. Glutamate can serve as a substrate for GS to synthesize glutamine, and it can also be used for synthesizing nitrogen-containing compounds such as proteins and nucleic acids[21]. Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) is also an ammonium assimilation enzyme in plants, which can catalyze biosynthesis of glutamic acid and oxidized glutamic acid from NH4+ and α-ketoglutarate to release ammonium[22]. Carbohydrates are the primary energy source for plants, ensuring their normal growth and metabolism. Sugar is one of the most important carbon metabolites, and it can be divided into monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides. The sugars are transported among different cells and organelles through transporters, that is called carbon partitioning[23]. Sucrose, the main transported form of sugar, and starch, the major energy storage substance of plants, continuously supply carbon and energy for plant development and also contribute to response to various environmental stresses[24]. Sucrose synthase (SS) enzyme and sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) enzyme are crucial for sucrose metabolism[25]. Previous researchers found that plants respond to salt stress by altering the levels of substances and enzyme activities associated with carbon and nitrogen metabolism[26]. For example, salt stress inhibits the uptake of NO3− and NH4+ in maize leaves and the activities of NR, GS, and GOGAT in cucumber[27]. After 6 h of salt stress treatment, the genes related to carbon and amino acid metabolism are upregulated in rice leaves[28]. In Chinese cabbage, the soluble sugar content is increased to sustain intracellular osmotic pressure by activating the expression of genes involved in starch and sucrose biosynthesis and degradation under salt stress[29].

S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) is a biosynthetic precursor of polyamines (PA) and ethylene[30]. SAMS serves as a key enzyme in both animal and plant cells that catalyzes the synthesis of SAM from methionine and ATP[31]. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of SAMS genes in response to diverse environmental stresses. Ectopic expression of Medicago falcalta MfSAMS1 in tobacco stimulates the biosynthesis and oxidation of PAs, which subsequently boosted the antioxidant defense triggered by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) signaling, thereby increasing plant tolerance to low-temperature stress[32]. In soybean, SAMS participates in response to flooding and drought stresses by affecting ethylene biosynthesis[33]. Ectopic expression of Andropogon virginicus AvSAMS1 in Arabidopsis leads to changed methylation status of DNA and histone H3, thus enhancing aluminum tolerance[34]. Furthermore, four SlSAMS members have been identified in tomato, and they exhibit various expression patterns under different stress and hormone treatments[35]. SlSAMS1 is localized in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and plasma membrane[36]; overexpression of SlSAMS1 improves tomato tolerance to alkali stress, drought stress, and salt stress by regulating PA, cGMP, H2O2, and ABA signaling[36,37].

Tomato is an important vegetable that plays a significant role in both agricultural production and trade. But salinization of soil significantly restricts tomato plant growth. Therefore, in-depth investigation of salt stress response and regulation mechanisms is critical for improving plant resistance, yield, and quality in tomato. Previous studies showed that both SlSAMS1 gene and carbon and nitrogen metabolism can respond to salt stress, but their regulatory relationship under salt stress is not yet established. Different plant tissues, such as roots, upper leaves, lower leaves, and fruits, display diverse metabolic capacity[38]. Here, we analyzed substance contents and enzyme activities related to carbon and nitrogen metabolism in different tissues of WT (wild-type) and SlSAMS1 overexpressing (SlSAMS1-OE) lines at both seedling and adult-plant stages under normal and salt stress conditions. Crucially, we found that SlSAMS1 overexpression can increase carbon and nitrogen metabolism to improve tomato salt tolerance.

-

Tomato inbred line 895 and SlSAMS1 overexpression lines (T2 plants) reported in our previous study[39] were used in the current study. The seedlings used for salt treatment were cultivated in a growth chamber using hydroponics with Hoagland's nutrient solution as described previously[36]. The nutrient solution containing 75 mM NaCl or not were replaced at 3-d intervals. After 15 d of salt treatment, the samples were collected.

The adult plants of WT and SlSAMS1-OE lines were also subjected to salt treatment. The seedlings were grown in a growth chamber using substrate cultivation, at the four-true-leaf stage, they were transplanted into the buckets filled with grass charcoal-vermiculite mix (3:1, v/v). Salt treatment was applied during the initial flowering stage. The treatment group tomato plants were provided with Hoagland's nutrient solution containing 85 mM NaCl per plant weekly, while the plants of control group were supplied with an equivalent amount of Hoagland's nutrient solution. The upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits were collected after seven weeks.

Measurement of nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+) content

-

NO3− level was determined following the method outlined by Du et al.[40]. Briefly, 2 g tomato tissue samples (leaves and roots in seedlings, and upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits in adult plants, the same as below) were combined with 10 mL deionized water in a boiling water bath, after 30 min, the extract was mixed with 5% salicylic acid-H2SO4 solution and reacted for 20 min, finally 8% NaOH was introduced to stop the reaction and the absorbance was recorded at 410 nm.

The NH4+ level in tomato tissues was assayed as previously described[41]. 0.1 g tomato sample was extracted with 100 mM HCl, followed by the addition of chloroform. The mixture was then shaken and centrifuged at 4 °C. The aqueous layer was mixed with activated carbon and filtered. The solution was diluted 1:1 (v/v) with 100 mM HCl, incubated with 1% (w/v) phenol-0.005% (w/v) sodium nitroprusside solution, and 1% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite-0.5% (w/v) sodium hydroxide solution, then measured the absorbance at 620 nm.

Nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities analysis

-

The NR activity was determined based on the method reported by Golldack et al.[42] with the adoption of slight modifications. 0.5 g tomato tissues were homogenized using an extraction buffer on ice. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 4 °C, followed by collection of the supernatant. The enzyme extract solution was incubated with 100 mM KNO3 phosphate buffer and 0.2% NADH. Afterward, the reaction was terminated by adding 1% (w/v) sulfanilic acid and 0.2% α-naphthylamine. The absorbance was then recorded at 540 nm.

To assay GS, GDH, and GOGAT activities, 1 g tomato tissues were ground into homogenate in 5 mL 100 mM Tris HCl buffer under an ice bath. The supernatant, enzyme extract solution, was collected after centrifuging. GS activity was determined at 540 nm based on Dong et al.[43]. The enzyme extract solution and GS reaction mixture were mixed well and incubated at 30 °C for 15 min, 1 mL acidic FeCl3 terminated the reaction. GDH activity was assayed at 340 nm after adding the GDH reaction mixture (1 M NH4Cl, 3 mM NADH, 100 mM α-oxoglutarate, and 100 mM Tris HCl)[43]. The decrease in NADH at 340 nm indicated GOGAT activity[44].

Determination of sugar content

-

Sugar extraction and detection were carried out as previously described with some modifications[45]. Eight mL 80% ethanol was added to 0.2 g tomato tissue dry samples, extracted at 85 °C for 30 min, and centrifuged. The supernatants collected three times were mixed and the volume was adjusted to 50 mL for the determination of sucrose and total sugar contents. The starch content was analyzed in the precipitate after drying.

Carbon metabolism-related enzyme activities assay

-

For the determination of SS and SPS activities, enzyme extraction was performed according to Lang et al.[46] with minor adjustments. 0.5 g tomato tissues were homogenized in 4 mL 200 mM Tris HCl buffer under an ice bath, then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min. After crude enzyme solution extraction, the SS reaction mixture was added, a 30 °C water bath for 10 min, and 2 M NaOH terminated the reaction. Next, concentrated hydrochloric acid and 0.1% resorcinol were added, and the mixture was placed in a water bath at 80 °C for 10 min. After cooling, SS activity was assayed at 480 nm. The determination of SPS activity was identical to SS activity, with the exception that 100 mM fructose was replaced with 100 mM fructose 6-phosphate in the reaction mixture.

-

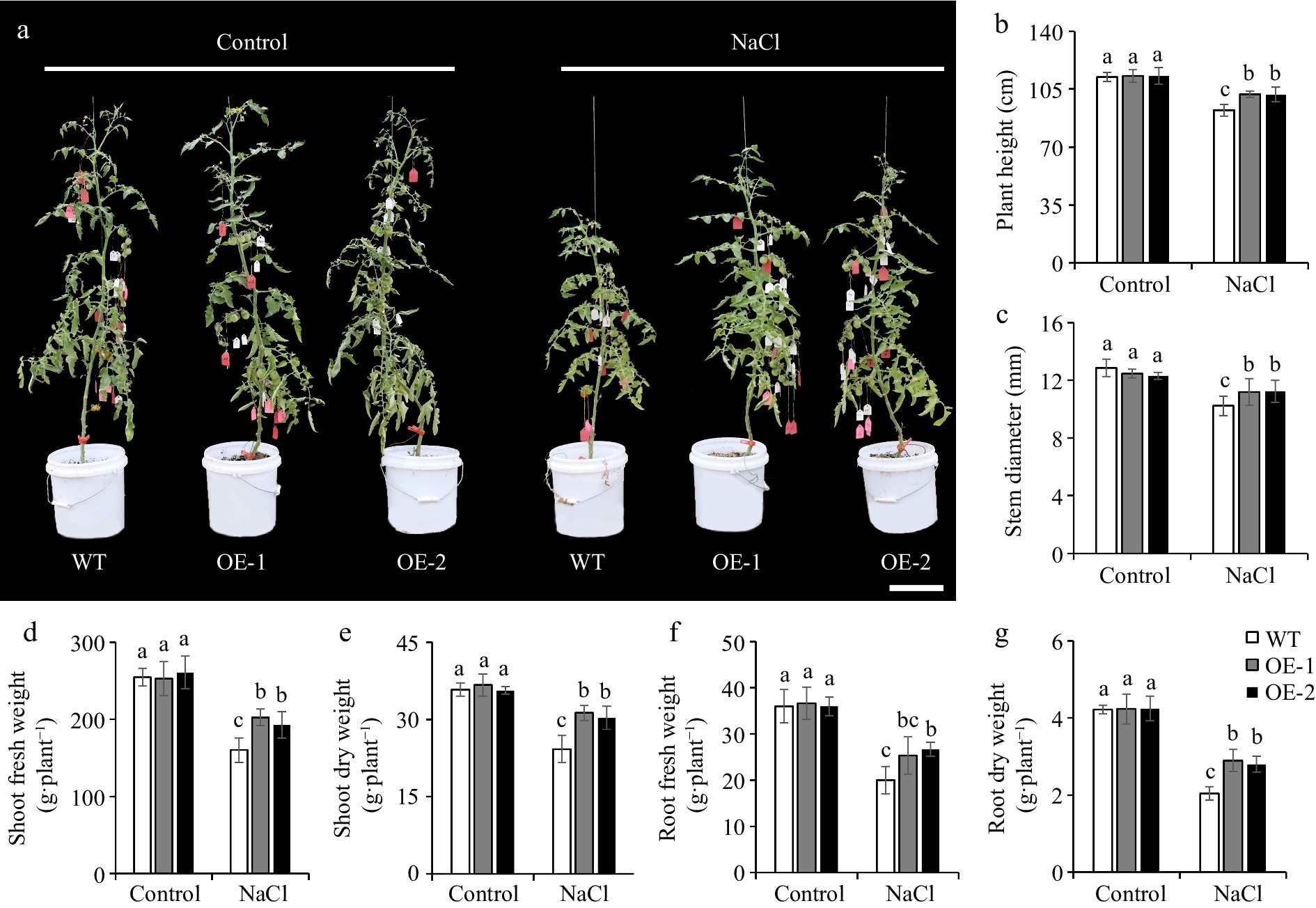

The effect of SlSAMS1 overexpression on improving salt tolerance in tomato seedlings has been demonstrated in our previous work[36], but its effects on adult plants under salt stress remained unknown. Therefore, we performed salt treatment during the initial flowering stage of tomato plants. Phenotype observation showed that overexpression of SlSAMS1 had no impact on the growth of adult tomato plants under normal conditions. Under salt treatment, plant growth was inhibited, but the SlSAMS1-OE lines showed remarkable increases in plant height, stem diameter, and biomass compared with the WT plants (Fig. 1), suggesting that the salt tolerance of adult plants is also improved conferred by SlSAMS1 overexpression in tomato.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of SlSAMS1 improves salt tolerance in adult tomato plants. (a) The growth phenotype of wild-type (WT) and SlSAMS1 overexpressing (OE) lines under control and NaCl treatment. Bar = 20 cm. (b) Plant height, (c) stem diameter, (d) fresh aboveground weight, (e) dry aboveground weight, (f) fresh underground weight, and (g) dry underground weight of WT and OE lines under control and NaCl treatment. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and four plants are included in each replicate. The letters indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p < 0.05).

SlSAMS1 overexpression increases nitrogen contents under salt stress

-

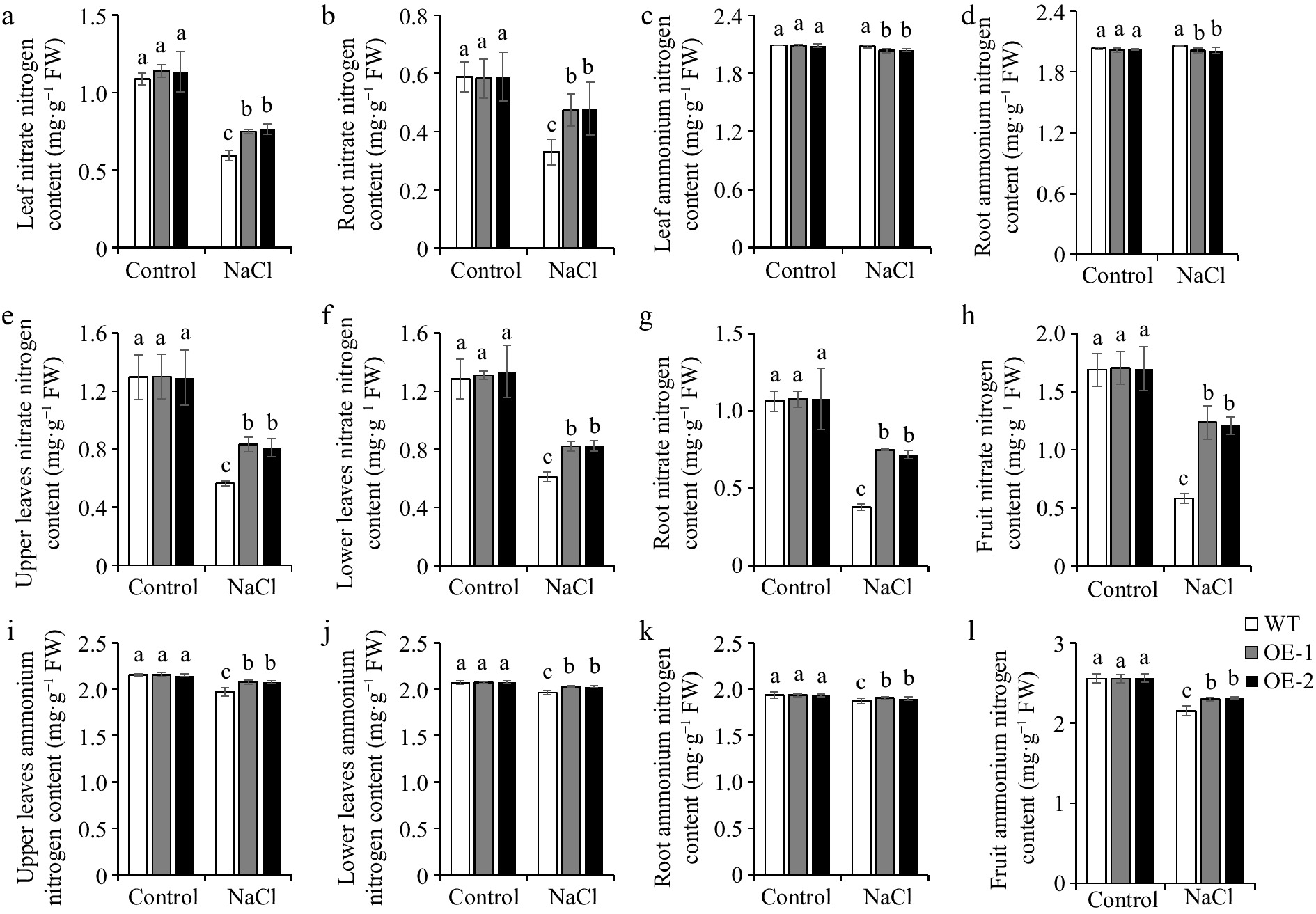

Nitrogen is primarily absorbed and utilized by plants from soil in two forms: NO3− and NH4+[20]. Thus, we measured NO3− and NH4+ contents in tomato plants. With normal conditions, no obvious changes were discovered in NO3− and NH4+ contents of various tissues between OE lines and WT (Fig. 2). The NO3− content decreased under salt treatment, but the NH4+ content remained relatively unchanged in leaves and roots of tomato seedlings. However, NO3− level in OE lines was higher than that in the WT, while NH4+ level was lower in OE lines (Fig. 2a−d). NO3− and NH4+ contents significantly decreased under salt treatment in upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits of tomato adult plants, but NO3− and NH4+ contents were increased in OE lines compared with the WT (Fig. 2e−l). This suggested that overexpression of SlSAMS1 adjusts the nitrogen content in tomato plants under salt stress.

Figure 2.

The effect of overexpression of SlSAMS1 on nitrogen content in tomato seedling leaves and roots, adult plants upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits under salt stress. (a), (b), (e)−(h) The nitrate nitrogen content and the (c), (d), (i)−(l) ammonium nitrogen content of WT and OE lines under control and NaCl treatment. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and four plants are included in each replicate. The letters indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p < 0.05).

Overexpression of SlSAMS1 increases the enzyme activities related to nitrogen metabolism in response to salt stress

-

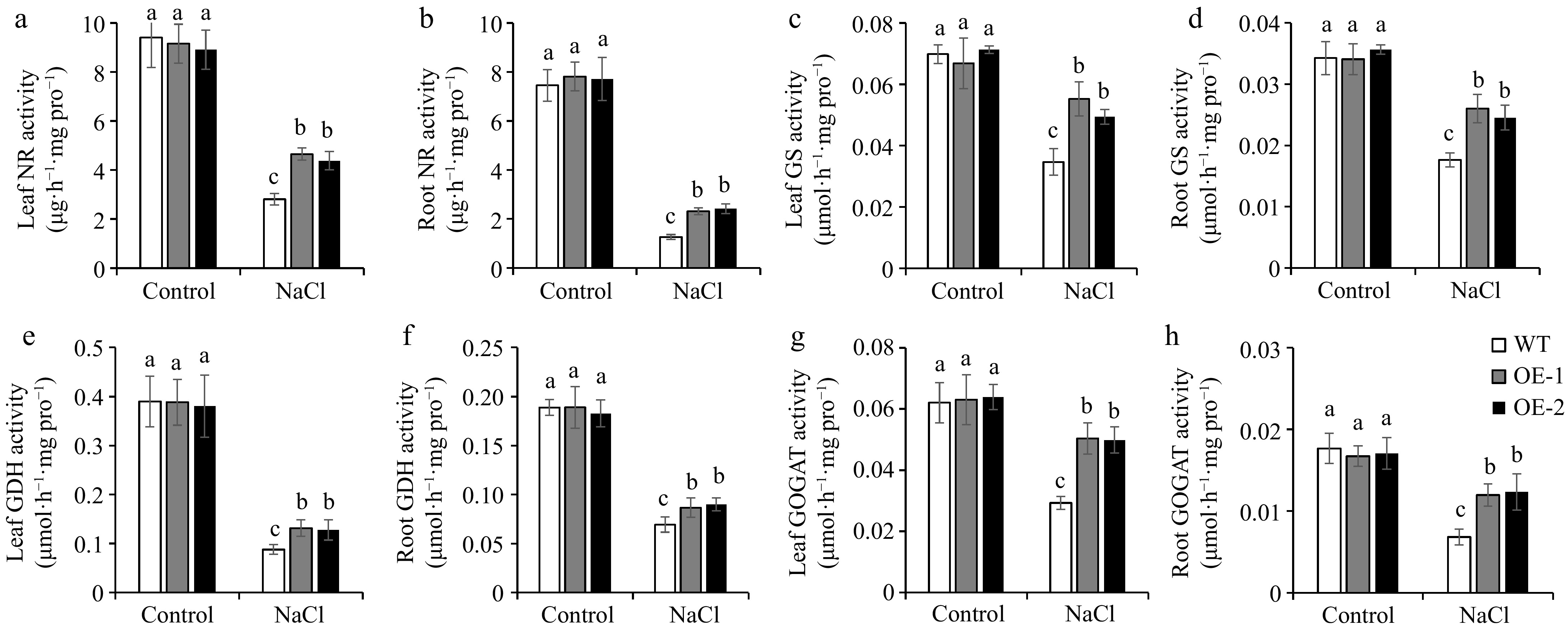

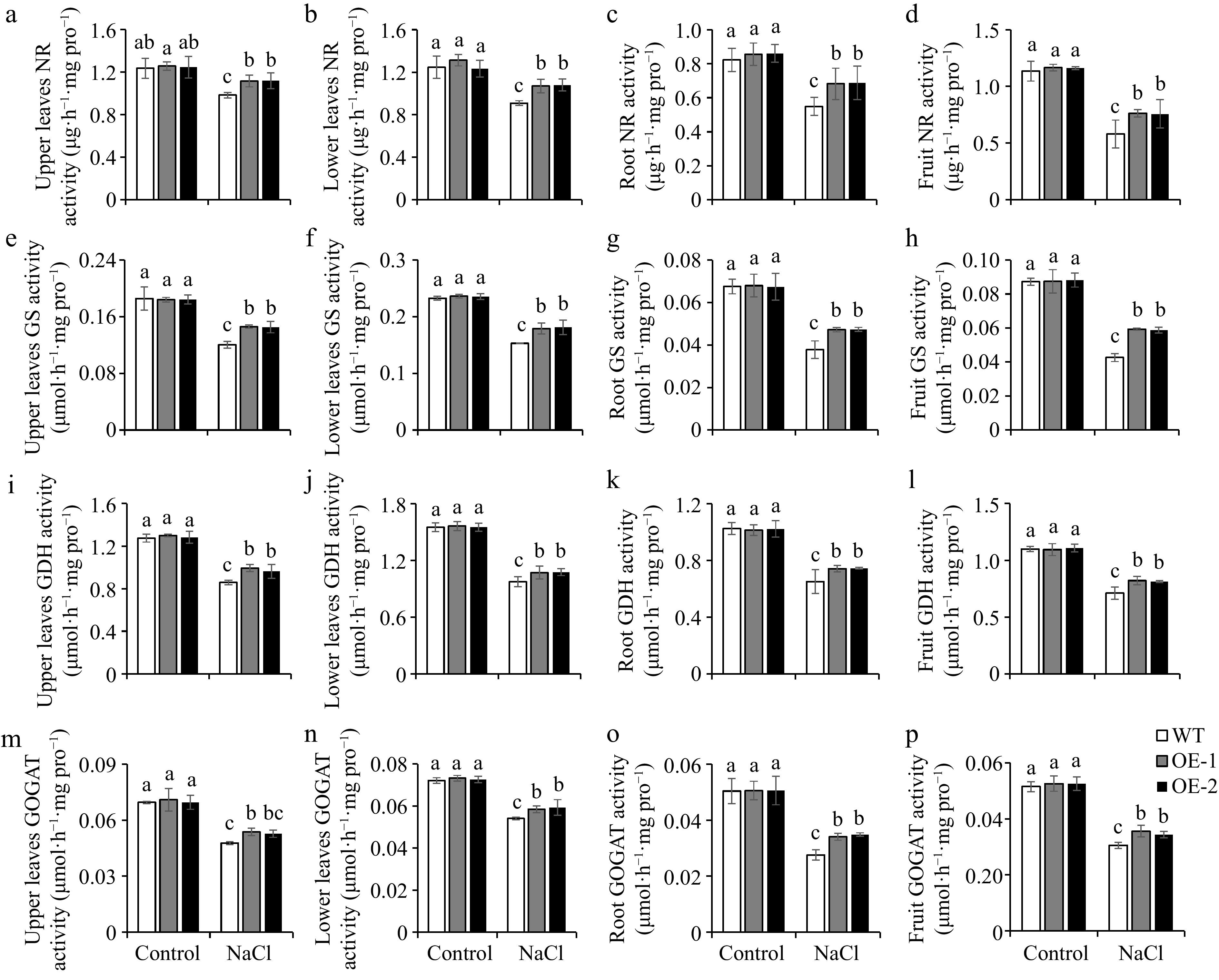

The concentrations of nitrogen in plant tissue are related to nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities. The nitrogen forms that plants can directly absorb primarily exist in the form of NO3−, which must be reduced by NR before it can be further utilized[21]. Our data indicated that NR activity was comparable between the WT and OE lines in tomato plants under normal conditions. NR activity was reduced significantly under salt conditions, but the OE lines exhibited higher NR activity than WT in both leaves and roots of seedlings, and upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits of adult plants (Fig. 3a & b; Fig. 4a−d). GS-GOGAT cycle is responsible for the further assimilation of ammonium[21]. Therefore, we determined the activities of GS, GDH, and GOGAT. The results showed that the trend of changes in GS, GDH and, GOGAT activities was similar to NR activity (Fig. 3c−h; Fig. 4e−p). This indicated that overexpression of SlSAMS1 can enhance nitrogen metabolism to adapt to salt stress by increasing the activities of nitrogen metabolism-related enzymes in tomato.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of SlSAMS1 regulates nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities in tomato seedling leaves and roots under salt stress. (a), (b) Nitrate reductase (NR), (c), (d) glutamine synthetase (GS) activity, (e), (f) glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) activity, and (g), (h) glutamine-2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT) activity of WT lines and OE lines under control and NaCl treatment. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and four plants are included in each replicate. The letters indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of SlSAMS1 regulates nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities in the upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits of adult tomato plants under salt stress. (a)−(d) Nitrate reductase (NR) activity, (e)−(h) glutamine synthetase (GS) activity, (i)−(l) glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) activity, and (m)−(p) glutamine-2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT) activity of WT and OE lines under control and NaCl treatment. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and four plants are included in each replicate. The letters indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p < 0.05).

Overexpression of SlSAMS1 increases sugar contents under salt stress

-

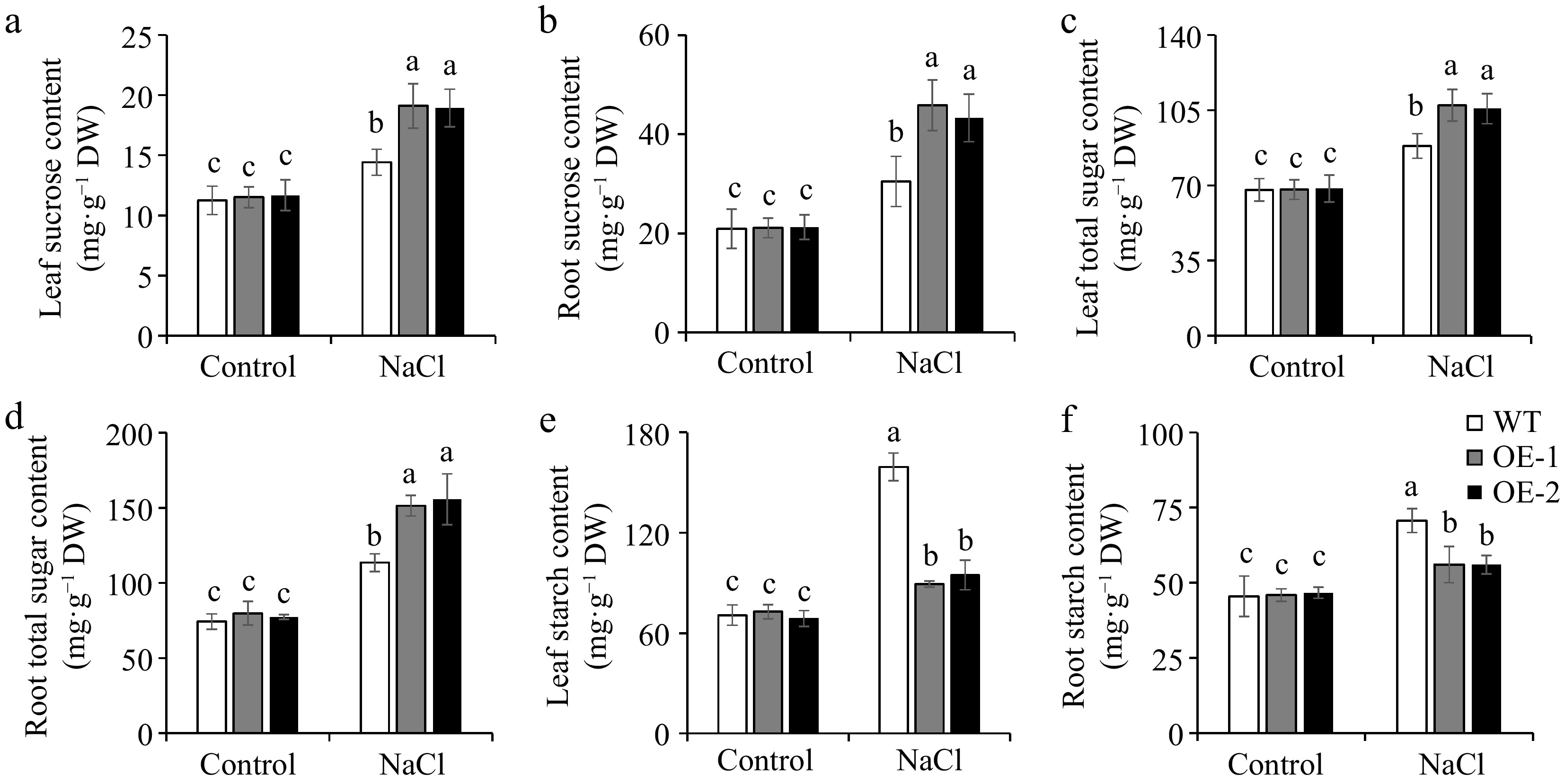

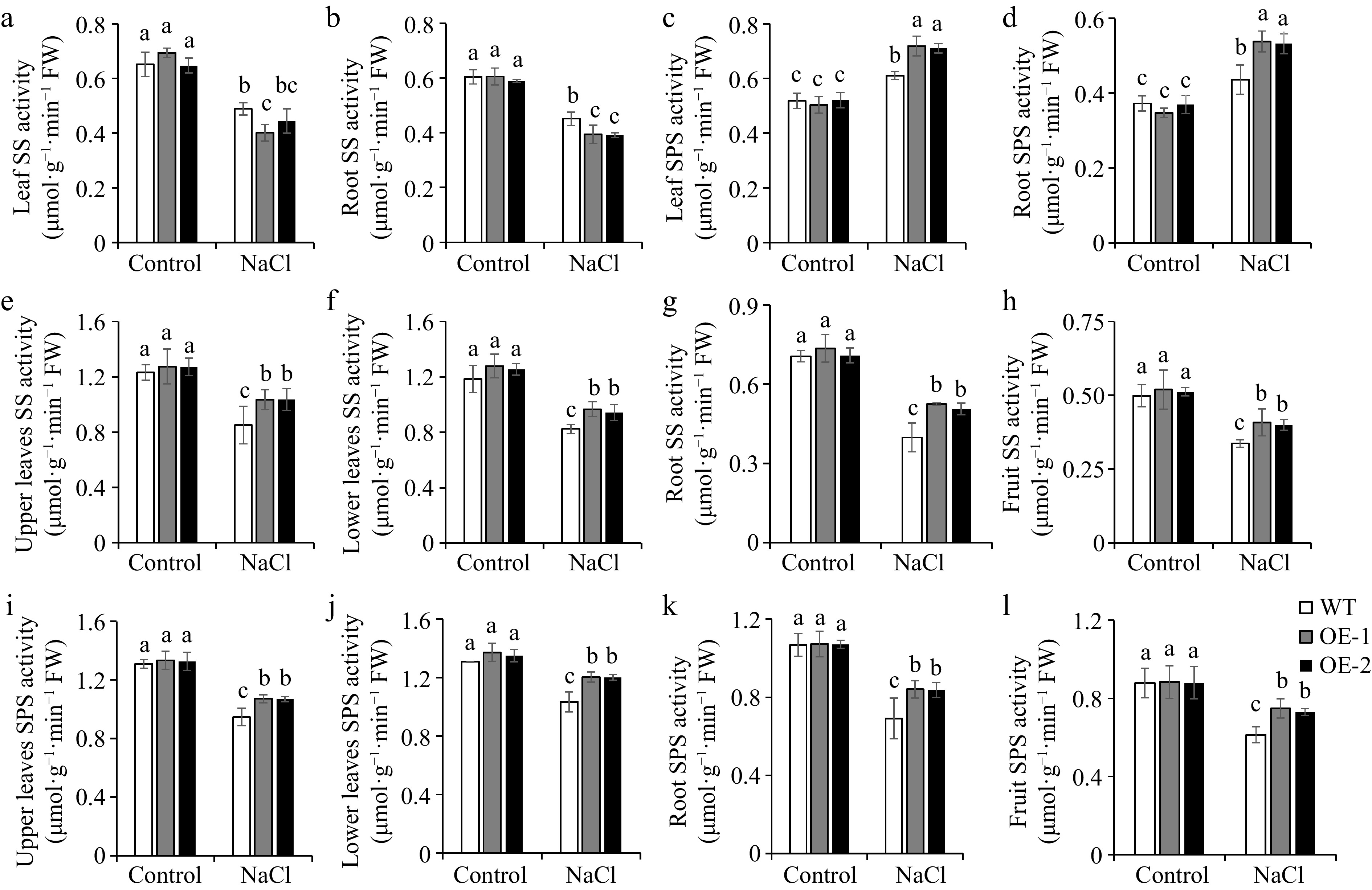

Studies have demonstrated that many plants actively accumulate sugars as a strategy to cope with abiotic stress[47]. In our study, under normal conditions, no differences were observed in sucrose, total sugar, and starch contents between WT and OE lines. Salt stress induced significant increases in sucrose and total sugar levels of tomato leaves and roots. The OE lines carried higher sucrose and total sugar contents in the leaves and roots of tomato seedlings, as well as in the upper leaves, lower leaves, and roots of adult tomato plants, as compared to the WT plants (Fig. 5a−d; Fig. 6a−c, e−g), revealing that the increased sugar contents may contribute to the improvement of salt tolerance in SlSAMS1 overexpression plants. However, the sucrose and total sugar contents decreased under salt stress in tomato fruits, but the sugar contents of OE lines remained higher than those of WT (Fig. 6d & h). The starch contents in both tomato seedlings and adult plants (excluding fruits) were also induced by salt treatment but were almost unaffected in tomato fruits. However, unlike sugar contents, starch levels in the leaves and roots of seedlings, as well as in the upper and lower leaves, and roots of adult plants, were lower in OE lines compared with the WT under salt stress (Fig. 5e & f; Fig. 6i−k), meaning that overexpression of SlSAMS1 can respond to salt stress by converting more starch into sugar.

Figure 5.

The influence of overexpression of SlSAMS1 on sugar contents in tomato seedling leaves and roots under salt stress. (a), (b) Sucrose content, (c), (d) total sugar content, and (e), (f) starch content of WT and OE lines under control and NaCl treatment. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and four plants are included in each replicate. The letters indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The influences of overexpression of SlSAMS1 on sugar contents in the upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits of tomato adult plants under salt stress. (a)−(d) Sucrose content, (e)−(h) total sugar content, and (i)−(l) starch content of WT lines and OE under control and NaCl treatment. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and four plants are included in each replicate. The letters indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p < 0.05).

Overexpression of SlSAMS1 regulates the activities of carbon metabolism-related enzymes to adapt to salt stress

-

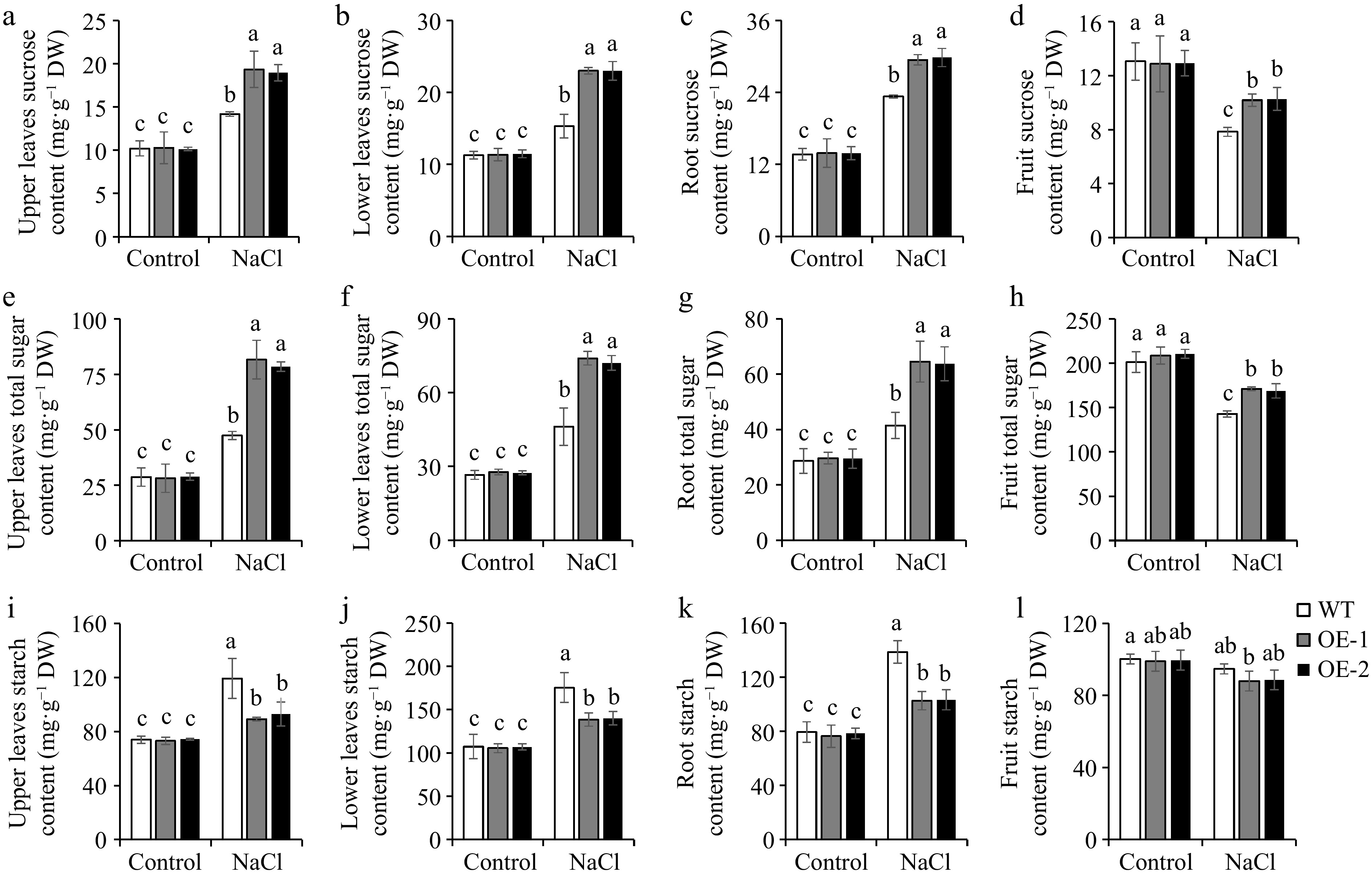

In plant cells, sucrose synthesis is primarily regulated by SS and SPS[25]. Our results showed that the SS and SPS activities were similar between WT and OE lines in leaves and roots of tomato seedlings and upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits of tomato adult plants under normal conditions (Fig. 7). Under salt conditions, SS activity decreased, with OE lines significantly lower than WT, while SPS activity increased, with OE line significantly higher than WT in leaves and roots of seedlings (Fig. 7a−d). However, in upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits of adult tomato plants, both SS and SPS enzyme activities decreased under salt conditions, and the OE lines still exhibited higher activities as compared to WT (Fig. 7e−l), implying that overexpression of SlSAMS1 can improve the activities of carbon metabolism-related enzymes in tomato plants to adapt to salt stress.

Figure 7.

Overexpression of SlSAMS1 adjusts carbon metabolism-related enzyme activities in the leaves and roots of tomato seedlings, and upper leaves, lower leaves, roots, and fruits of adult plants under salt stress. (a), (b), (e)−(h) Sucrose synthase (SS) and (c), (d), (i)−(l) sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) activity of WT and OE lines under control and NaCl treatment. Values are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates, and four plants are included in each replicate. The letters indicate significant differences (Tukey's test, p < 0.05).

-

Salt stress impacts various stages of the crop life cycle, such as seed germination, seedling development, and reproductive processes, causing considerable reductions in yield and quality[48]. SAMS plays essential roles in plant responses to salt stress. For instance, ectopic expression of sugar beet BvM14-SAMS2 in Arabidopsis improves salt tolerance by strengthening the antioxidant defense mechanism and PA metabolism[49]. In cucumber, CsSAMS1 and CsSAMS2 contribute to stress adaptation, with a well-regulated increase in CsSAMS1 expression in plants appearing to enhance their salt tolerance[50]. Our earlier work has reported that tomato SlSAMS1 overexpression imparts salt tolerance to the seedlings[36]. Consistent a previous study, we found that overexpression of SlSAMS1 also increased plant height, stem diameter, and biomass of adult tomato plants (Fig. 1), indicating the roles of SlSAMS1 in improving tomato salt tolerance throughout the entire growth cycle. In agreement with this, a grafting experiment revealed that the rootstocks from SlSAMS1-overexpressing plants developed a more robust root system, accumulated higher levels of PA, and absorbed more essential nutrients under alkaline stress, and consequently improved fruit yield[39].

Nitrogen is an indispensable nutrient essential to crop growth and yield. NO3− and NH4+ are the primary forms of nitrogen which can be absorbed by plants[51]. Through the catalysis of NR and NiR, the main organic nitrogen compounds, glutamine, and glutamate, are produced, which then distribute the nitrogen to other macromolecules and nitrogen-containing compounds[19]. In line with the common hypothesis that salt stress suppresses the uptake of nitrogen in plants[27], our results showed that NO3− content reduced under salt treatment. However, SlSAMS1 overexpressing lines showed higher NO3− level than the WT under salt stress (Fig. 2a & b, Fig. 2e−h). On the other hand, NH4+ content in tomato seedlings and adult plants exhibited opposite trends with overexpression of SlSAMS1. Briefly, NH4+ content decreased in the seedling stage and increased in the adult stage under salt stress (Fig. 2c, d, i−l). It could be because under prolonged salt treatment, SlSAMS1-OE lines maintain higher levels of NO3− and NH4+ to sustain nitrate reduction and ammonium assimilation. In addition, the tissues containing high to low NO3− and NH4+ levels in adult plants were in the following order: fruit > upper leaves > lower leaves > roots. In tomato seedlings, the leaves displayed a higher nitrogen level than the roots (Fig. 2). It is plausible that after absorbing nitrogen from the roots, tomato plants transport more nitrogen to the metabolically active tissues such as fruits and upper leaves, in accordance with the results of Mahmud et al.[52] on deciduous oaks. It indicated that overexpression of SlSAMS1 maintains nitrogen distribution under salt stress to maintain plant growth. The nitrogen content is directly related to the activity of nitrogen-metabolizing enzymes. After absorption in plants, NO3− is sequentially reduced to NH4+ by NR[53]. Analysis of NR activity showed that NR activity decreased in tomato plants under salt treatment, but OE lines had higher NR activity than WT (Fig. 3a & b, Fig. 4a−d). This was in agreement with previous studies that high salinity inhibited NR activity[27]. Some studies also indicated that NR is an enzyme whose activity can be induced, and its activity and NR transcript levels are directly proportional to NO3− concentrations[54]. Our results also confirmed that overexpression of SlSAMS1 simultaneously increased NO3− level and NR activity under salt stress (Fig. 2a, b, e−h; Fig. 3a & b; Fig. 4a−d). GS-GOGAT cycle is responsible for the assimilation of ammonium. In Luffa Mill, the activities of GDH, GS, and GOGAT decreased under salt stress[55]. Our study yielded similar results, showing that GDH, GS, and GOGAT activities decreased with salt treatment, but overexpression of SlSAMS1 increased it (Fig. 3c−h, Fig. 4e−p). Under the action of various nitrogen assimilation enzymes, the nitrogen content of tomato underwent corresponding changes, providing a material basis for plants to resist stress (Figs 2−4). Thus, overexpression of SlSAMS1 promoted the absorption and utilization of NO3− and the assimilation of NH4+, reduced the toxic effects of NH4+ accumulation, and responded to salt stress in tomato plants.

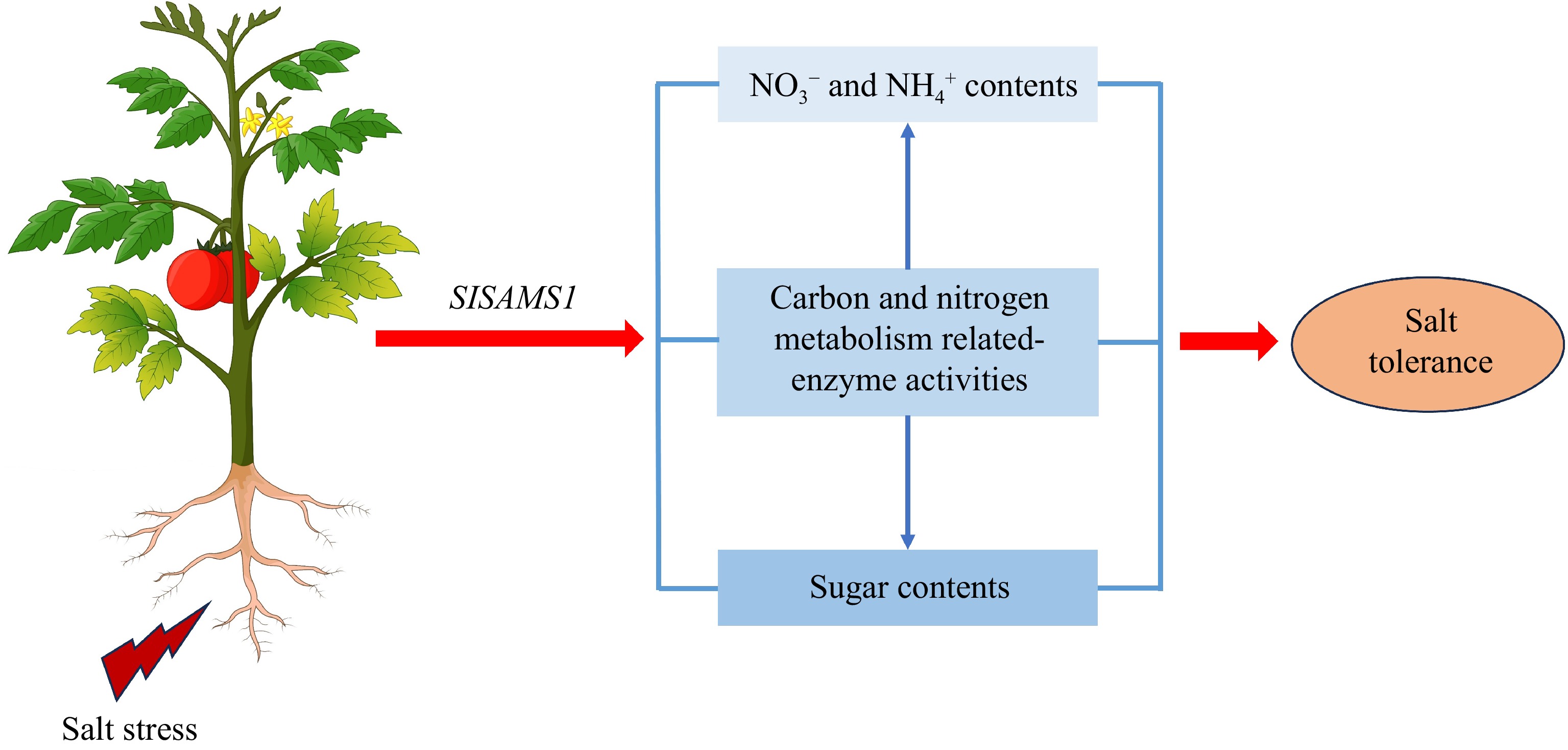

Carbon metabolism processes include the assimilation of carbon through photosynthesis, sucrose and starch metabolism, and transport and utilization of carbohydrates[46]. Carbon is fixed in leaves (carbon source) through photosynthesis, followed by transport to other tissue (sink) in the form of sugars, fructan, or starch. Afterward, sugar is resynthesized and transported from the leaves during the dark period[56]. Consistent with the fact that plants actively accumulate sugars to resist environmental stress[29], our current study showed that the concentrations of sucrose and total sugar significantly increased in tomato with salt treatment, while sugar contents in OE lines were higher than those in WT (Fig. 5a−d; Fig. 6a−c & e−g), indicating that overexpression of SlSAMS1 can respond to salt stress by increasing sugar content. However, the sucrose and total sugar levels of fruits decreased under salt stress, but the sugar contents of OE fruits were still higher than those of WT fruits, implying that overexpression of SlSAMS1 might enhance tomato fruit quality (Fig. 6d & h). Meanwhile, starch content also increased in tomato leaves and roots with salt treatment (Fig. 5e & f; Fig. 6i−k), which aligned with the results of Shen et al.[45] in cucumber. Nevertheless, excessive accumulation of starch has adverse effects on plant growth under stress conditions[57]. Herein, OE lines had lower starch contents than WT (Fig. 5e & f; Fig. 6i−k), suggesting that overexpression of SlSAMS1 can convert more starch into sugars during salt stress. Besides, carbohydrates are the main energy substances in plants, supporting normal growth and metabolic processes. Sugar, as the main storage and mobile form of photosynthetic products in higher plants, continuously provides carbon and energy sources for plant growth and development from source to sink[58]. In this study, the adult tomato plants carried the highest total sugar contents in fruits, followed by upper and lower leaves (Fig. 6e−h), indicating that sugar synthesized in the leaves through photosynthesis is transported more to the fruits to provide energy for their development. However, in the lower leaves, the decrease in photosynthetic capacity due to aging resulted in lower sugar content compared to the upper leaves, while starch content was higher (Fig. 6e, f, i & j). Carbon-metabolizing enzymes in plants are SS and SPS. SPS is involved in sucrose synthesis, whereas SS participates in sucrose breakdown[25]. In tomato seedlings, SPS activity increased and SS activity decreased under salt conditions, while OE lines had higher SPS activity and lower SS activity than WT, thereby accumulating more sucrose to improve salt tolerance (Fig. 5a & b; Fig. 7a−d). However, in adult plants, both SPS and SS activities decreased under salt conditions, but they were still higher in OE plants than those in WT (Fig. 7e−l). This may be due to long-term salt stress exacerbating the inhibition of SS and SPS activities. Based on the above findings, we proposed a model showing the regulatory pathway of SlSAMS1 in response to salt stress. Salt stress induces the expression of SlSAMS1. Overexpression of SlSAMS1 increases the contents of NO3−, NH4+, and sugar, and activities of carbon and nitrogen metabolism-related enzymes, thus improving tomato salt tolerance. In this pathway, the altered carbon and nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities also contribute to the changes in NO3−, NH4+, and sugar levels (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed model showing that SlSAMS1 overexpression enhances tomato salt tolerance by regulating carbon and nitrogen metabolism. Under salt stress, the SlSAMS1 expression is activated; overexpression of SlSAMS1 maintains high levels of energy metabolism, as evidenced by increased NO3−, NH4+, and sugar content, and carbon and nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities, thus enhancing tomato salt tolerance. In this pathway, the altered enzyme activities are also responsible for the changes of nitrogen and sugar levels.

-

Carbon and nitrogen metabolism are intricately connected to plant growth and stress responses. Therefore, strict control of carbon and nitrogen fluxes in cellular metabolism and throughout the life cycle of a plant is crucial to ensure their survival and reproduction under environmental constraints. Overexpression of SlSAMS1 enhances activities of carbon and nitrogen metabolism-related enzymes, reduces starch content, and increases sugar and nitrogen content, thereby sustaining high carbon and nitrogen metabolism and ensuring normal tomato plant growth under salt stress. SlSAMS1 can enhance salt tolerance by improving carbon and nitrogen metabolism.

This work was supported by the Central Guiding Local Science and Technology Development Funds of Shandong Province (YDZX2023071), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372798), Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (2022TZXD0025), and Shandong Vegetable Research System (SDAIT-05).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: experiments design and oversee: Zhang Y; experiments conducting, experimental results and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript: Liu Y, Xin X; manuscript revision: Zhang Y, Shi Q; assisting in the experiments and data analyses: Zheng J, Ge L, Li X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yue Liu, Xianchao Xin

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Y, Xin X, Zheng J, Ge L, Li X, et al. 2025. SlSAMS1 improves carbon and nitrogen metabolism in tomato under salt stress. Vegetable Research 5: e021 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0009

SlSAMS1 improves carbon and nitrogen metabolism in tomato under salt stress

- Received: 28 November 2024

- Revised: 13 February 2025

- Accepted: 18 February 2025

- Published online: 24 June 2025

Abstract: Salt stress limits plant growth and development of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). S-adenosyl methionine synthetase (SAMS) plays a pivotal role in response to salt stress in plants, however, its mechanism for regulating carbon and nitrogen metabolism in this process is not fully understood. Herein, we found that SlSAMS1, a SAMS homologous gene in tomato, enhances salt tolerance throughout the entire lifecycle of tomato plants. Salt stress inhibits carbon and nitrogen metabolism in tomato plants, while overexpression of the SlSAMS1 gene maintains high levels of energy metabolism, as evidenced by increased nitrogen contents, sugar contents, and enzyme activities related to carbon and nitrogen metabolism during salt stress, thus ensuring better growth and development under salt stress in tomato.

-

Key words:

- Tomato /

- SlSAMS1 /

- Carbon and nitrogen metabolism /

- Salt stress