-

Anthocyanins are a class of natural polyphenolic compounds widely found in foods such as citrus fruits, blueberries, tea, onions, peppers, apples, and others[1]. These compounds exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties[2] and support cardiovascular health, aiding in overall health maintenance and chronic disease prevention[3]. However, common anthocyanin exhibits poor stability, and prolonged exposure to light and high temperatures accelerates their degradation and inactivation[4]. Therefore, improving anthocyanin stability is one of the important views in the food industry due to its beneficial effects and commercial values.

Copigmentation reactions occur naturally in fruits, vegetables (especially berries), flowers, and derived food products of wine and jams[5]. During these reactions, anthocyanins could form complexes with other pigments or small molecules (such as polyphenols, organic acids, and metal ions), increasing their stability and resulting in bathochromic and hyperchromic effects[4-6]. Among the reported pigments, polyphenols are the primary compounds involved in color enhancement with anthocyanins. Their copigmentation efficacy surpasses that of organic acids and other molecules, primarily driven by π-π stacking interactions. The π-conjugation of flavonoids (e.g., quercetin, kaempferol, and rutin) extends throughout the tricyclic core structure (A-, B-, and C-ring), and thus they appear to be the most potent copigment (i.e., the ones with the strongest bathochromic and hyperchromic effects) and have the highest Gibbs binding energy[7]. Moreover, related theoretical research indicated that the anthocyanin-polyphenol copigmentation complex is primitively formed with a 1:1 molecular ratio. The π-π stacking and intermolecular hydrogen bonding between molecules can protect anthocyanins from nucleophilic attack by water molecules, thereby increasing their stability and solution absorbance[8,9]. Additionally, the dominant structure of anthocyanins varies with pH, which influences the absorbance of the solution. In highly acidic conditions (pH < 2), anthocyanins primarily exist in the cationic form[7]. As the pH increases to mildly acidic levels (3 < pH < 6), anthocyanins undergo hydration at the pyran ring, transitioning into the hemiketal form as the predominant conformation[10]. All the above research indicates that copigmentation reactions can maintain and even increase the color of food products during processing or storage[8].

High-pressure processing (HPP) is a non-thermal food preservation technique that modifies food composition and properties by eliminating microorganisms, inhibiting enzymatic activity, and maintaining color, texture, and nutritional quality[11]. During HPP, shortened molecular distances and increased collision frequency could reduce activation energy, enhance the ease of chemical reactions, and accelerate the reaction rates. Numerous studies focusing on copigmentation interaction under HPP have shown that anthocyanins can form complexes with different small molecules and exhibit varied color and stability properties[7]. Previous research also revealed that HPP could increase the interaction rates of pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin by measuring solution absorbance and analysing the copigmentation complex structure using molecular dynamics simulation[12]. However, the gap between HPP effects on copigmentation complex structure distribution, structure characteristics, and corresponding stability has not yet been filled.

HPP can change the Boltzmann distribution of molecular structure and affect the copigmentation complex structure and corresponding properties by increasing the system energy. Due to the complexity of molecular distribution within the system[13], current research cannot fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying HPP effects on copigment complex stability at the molecular level but instead primarily describes and analyzes system properties from a macroscopic perspective. In response to these challenges, this study systematically evaluates the thermodynamic and light stability of copigment complexes obtained under different treatments (including pH, molar ratio, pressure, and processing time) by calculating the relative absorbance change percentage. Then, a series of computational methods (including cluster search, molecular dynamics simulation, and structure optimization with DFT) was applied to establish the molecular cluster distribution and representative structures. The copigmentation complex free energy, excited states, and weak interactions were obtained and used to explain the relationship between thermodynamic/light stability and different copigmentation complex structure distribution. This study aims to provide insights into the fundamental principles of copigmentation complex formation and stability characteristics, offering essential theoretical support and experimental guidance for the application of HPP in the food industry.

-

Pelargonidin-3-glucoside (Pg-3-Glc, CAS: 18466-51-8) was extracted from strawberry fruits, purified using high-speed counter-current chromatography (HSCCC), and identified with HPLC-MS following the previous study[9]. Catechin (CAS: 154-23-4) was purchased from Solarbio Co., Ltd (Beijing, China), and potassium phosphate dibasic, along with other chemicals, were of analytical grade and obtained from Tianjin Chemical Factory (Tianjin, China). Ultrapure water, with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ, was prepared using an ultrapure water system.

High-pressure processing and heat, light treatment

-

Pg-3-Glc (10−3 M) and catechin (10−2 M) were prepared in a 0.2 M potassium phosphate-citrate buffer at pH 1.5 and 3.6. Then, 20 μL of Pg-3-Glc solution was transferred into polyethylene bags (3 cm × 5 cm), and different volumes of catechin were added to achieve final catechin/Pg-3-Glc ratios of 1:1 and 10:1. Buffer of the same pH was added to bring the final solution volume to 2 mL, ensuring a final Pg-3-Glc concentration of 1.0 × 10−4 M to avoid self-copigmentation[14]. The prepared solutions were then processed using a 2.0 L high-pressure processing (HPP) unit (G7100 Food Lab, Stansted, UK) with a pressure-transmitting medium of isopropanol: water (3:7, v/v). Samples were subjected to pressures of 0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa and processing time of 5 and 30 min, respectively.

The solutions from different HPP treatments were processed using heat and light to evaluate the copigmentation complex stability. The thermal treatment was conducted by equilibrating the solutions in a water bath at 80 °C in the dark, based on previous research[9]. For light treatment, solutions were exposed to a 400 W high-pressure sodium lamp (80 lm/w), with a distance of 20 cm between the lamp and the samples. All treatments were conducted for durations of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min.

All solution absorbance was measured at 520 nm, and the stability of the copigmentation complexes after light or heat treatment was assessed by the absorbance ratio.

$ \mathrm{A}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}\;\mathrm{r}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}=\dfrac{\mathrm{S}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\;\mathrm{a}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}\;\mathrm{a}\mathrm{f}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\;\mathrm{h}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\;\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\;\mathrm{l}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}\;\mathrm{t}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{t}}{\mathrm{S}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\;\mathrm{a}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}\;\mathrm{w}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{t}\;\mathrm{t}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{t}} $ Copigmentation structure cluster search

-

The copigmentation complex structure search is important to explain the high-pressure processing effects, and thermal and light stability and could be an essential approach in this paper. To systematically search the molecular cluster structure and corresponding distribution under different HPP conditions, a series of computation methods were applied, as illustrated below. The Pg-3-Glc and catechin complex structure was identified using the molecular cluster search software of Molclus[15], and the default RMSD and binding energy values were used to cluster and identify the dominant structure distribution according to the Boltzmann distribution. Structures with a proportion larger than 10% were selected and used as the initial structure for molecular dynamic simulations of 0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa (Long-time molecular dynamic simulation could effectively cover the complex conformation space, while the methods of common quantum chemistry cannot process the pressure conditions). Structures from every frame were extracted, clustered and optimized using MOPAC[16]. The enthalpy was used to calculate the Boltzmann distribution, and refined structures with a proportion greater than 10% were selected and re-optimized using the quantum chemistry methods in Gaussian software.

Cluster search

-

The structures of Pg-3-Glc (flavylium form at pH 1.5 and neutral quinoidal bases at pH 3.6) and catechin were drawn. Random clusters of the complexes with a ratio of 1:1 (the dominant copigmentation complex ratio proved in the former literature) were generated using the Molclus software with default parameters, then pre-optimized with the MOPAC 2016 software at the PM6-DH+ level and the COSMO model with eps of 78.4[16]. The refined structures were then clustered with default energy criteria and structure RMSD of 0.5; their corresponding Boltzmann distribution percentage, was also calculated with the built-in function. All the clusters with percentages larger than 10% were selected as the initial structures for molecular dynamic simulation.

Molecular dynamic simulation assay

-

The selected cluster structures were processed with classical molecular dynamics simulations to search all possible conformations. The topological files of Pg-3-Glc and catechin were downloaded from the ATB website[17], and Amber99SB-ILDN force field was employed for molecular dynamics simulations (MDs) using GROMACS 2018.8[18,19]. The Pg-3-Glc and catechin cluster were placed into a cubic box with explicit solvent, and the system underwent energy minimization using the conjugate gradient method. Periodic boundary conditions were applied, and a 10 ns NPT simulation was performed. The time step was set to 1 fs, with an interaction cutoff of 10 Å. The temperature was maintained at 298.15 K, and the pressures were 0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa. Structures in 1,000 frames, evenly distributed in simulation time, were extracted for copigmentation conformation searching. These structures were then processed to obtain the target structures at different pressures using the same method in the cluster searching section.

Quantum chemistry calculation

-

The processed copigmentation clusters were further optimized using Gaussian 16 software with the Density Functional Theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-311G(d, p) level[20−22]. The IEF-PCM continuum solvation model was employed to account for solvent effects. The system energy was used to calculate the corresponding Boltzmann distribution, and the optimized structures were used to calculate the excited states and the weak interaction characteristics between Pg-3-Glc and catechin.

Excited energy analysis

-

Excited-state energy of the above copigmentation complex cluster was calculated with the TD method at the B3LYP/6-311G(d, p) level, and the IEF-PCM continuum solvation model was employed to account for solvent effects. The excited-state energy was calculated by adding excitation strength to the total energy.

Weak interaction analysis

-

The wave functions of copigmentation complex clusters produced by Gaussian software were imported to Multiwfn software[23] for analysis. The non-covalent interactions between Pg-3-Glc and catechin in different copigmentation complexes were depicted using the Independent Gradient Model based on the Hirshfeld partition of molecular density (IGMH), which typically provides improved graphical clarity. The IGMH function in Multiwfn 3.8 was used to characterize the weak interactions, which were mainly divided into strong electrostatic interactions (depicted as blue), van der Waals interactions (depicted as green), and strong repulsion (depicted as the steric effect, red). The IGMH interaction regions and color-mapped iso-surface graphs were rendered using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD 1.9.3) software[24].

Statistical analysis

-

All data were analyzed using Origin 2018 software (Origin Lab Corporation, Massachusetts, USA). The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. General linear model (GLM) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted for significance analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

-

Due to its simple structure and pronounced activity, catechin is often chosen as a representative model in studies on the copigmentation effects of polyphenols on anthocyanins. It is commonly found in various natural products, such as red wine, fruit juices, and flowers[25−27], making it an important reference for understanding anthocyanin stability and color modulation. Previous research found that variations in anthocyanin types, catechins, and dominant cationic forms at specific pH levels can influence copigmentation reactions, leading to color changes under high-pressure processing[9]. To systematically evaluate the HPP conditions on copigmentation complex thermal stability, the absorbance of copigmentation solutions from different pH levels, catechin/Pg-3-Glc ratios, and HPP treatments under different heating times was measured. Since HPP can accelerate copigmentation reaction rates, the initial solution absorbance varied under different conditions, making it difficult to differentiate the level of absorbance change. Therefore, the absorbance ratio was used for better data illustration and comparison results analysis.

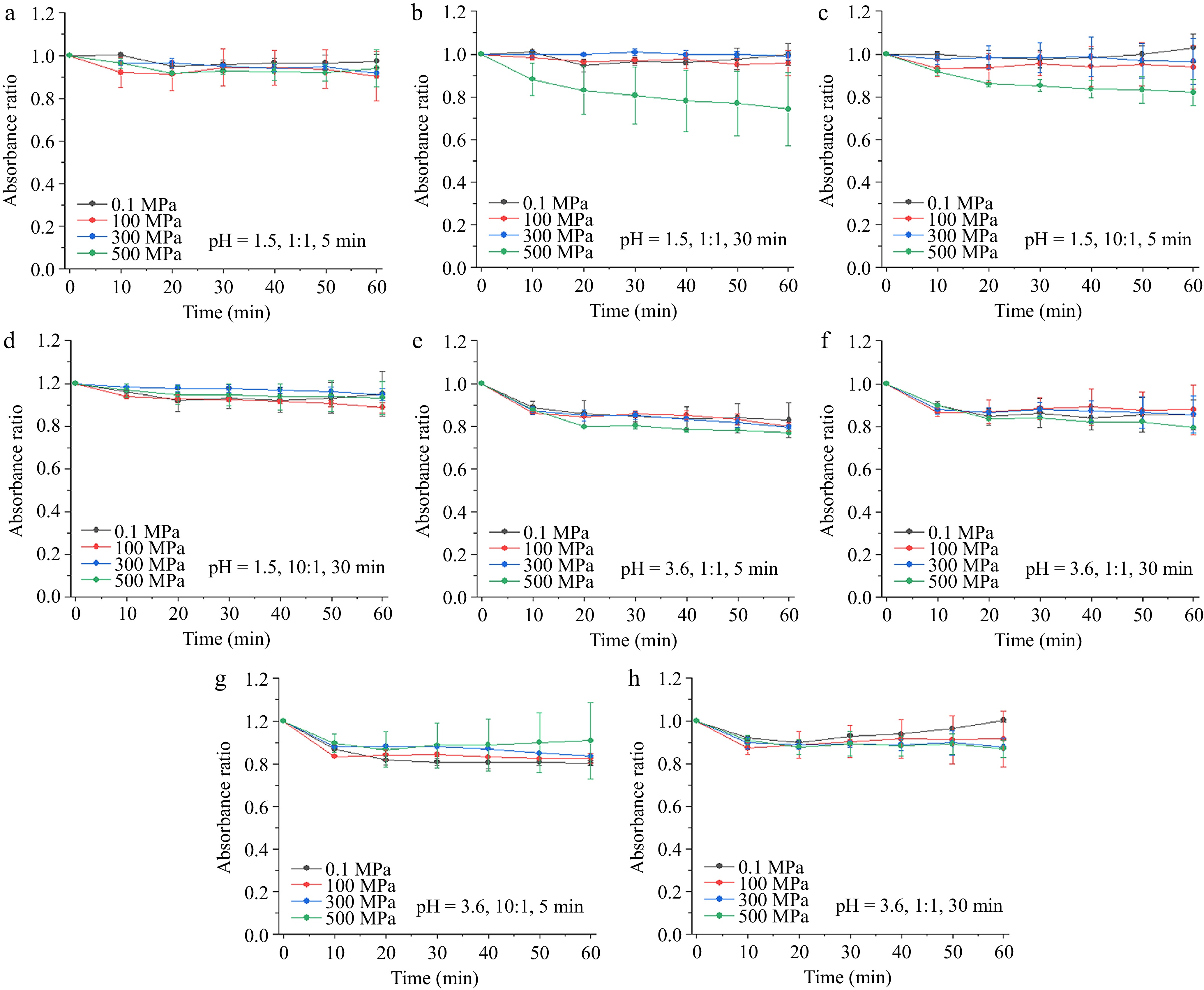

As shown in Fig. 1, the absorbance of copigmentation solutions at pH 1.5 and pressures of 0.1, 100, and 300 MPa remained stable and showed no significant trend across different pressures during all the treatment times. In contrast, copigmentation solutions at 500 MPa, with a molar ratio of 1:1 and a high-pressure processing time of 30 min, as well as those with a molar ratio of 10:1 and a high-pressure processing time of 5 min, showed comparatively lower stability. At 500 MPa with a molar ratio of 1:1, extending the high-pressure processing time significantly reduced the stability of the copigmentation complex. This may be due to the impact of high pressure on the weak interactions between pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin[28]. In addition, the general linear model analysis results indicated that the absorbance change tendency at 500 MPa had a significant difference with other processing conditions. Other processing conditions, except the high-pressure processing time (with the p-value of 0.593, data was not shown), had significant effects on the copigmentation complex stability. When the solution pH rose to 3.6, the absorbance decreased due to the partial conversion of red flavonoid cations into colorless hemiketals in the weak acid solution[29]. The absorbance change tendency at 500 MPa had a significant difference with other processing conditions, although the difference was less pronounced compared with those at pH 1.5, and the high-pressure processing time had no effects on the thermal stability of copigmentation complex. Furthermore, all the solution absorbance of the copigmentation solution changed flatly, indicating that moderate heat may not significantly affect the system stability.

Figure 1.

Thermal processing on the absorbance changes of pelargonidin-3-glucoside/catechin complex. (a)−(d) Copigmentation conditions: pressures of 0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa, processing time of 5 and 30 min, solution pH of 1.5 and catechin/pelargonidin-3-glucoside ratios of 1:1 and 10:1. (e)−(h) Copigmentation conditions: pressures of 0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa, processing time of 5 and 30 min, solution pH of 3.6 and catechin/pelargonidin-3-glucoside ratios of 1:1 and 10:1.

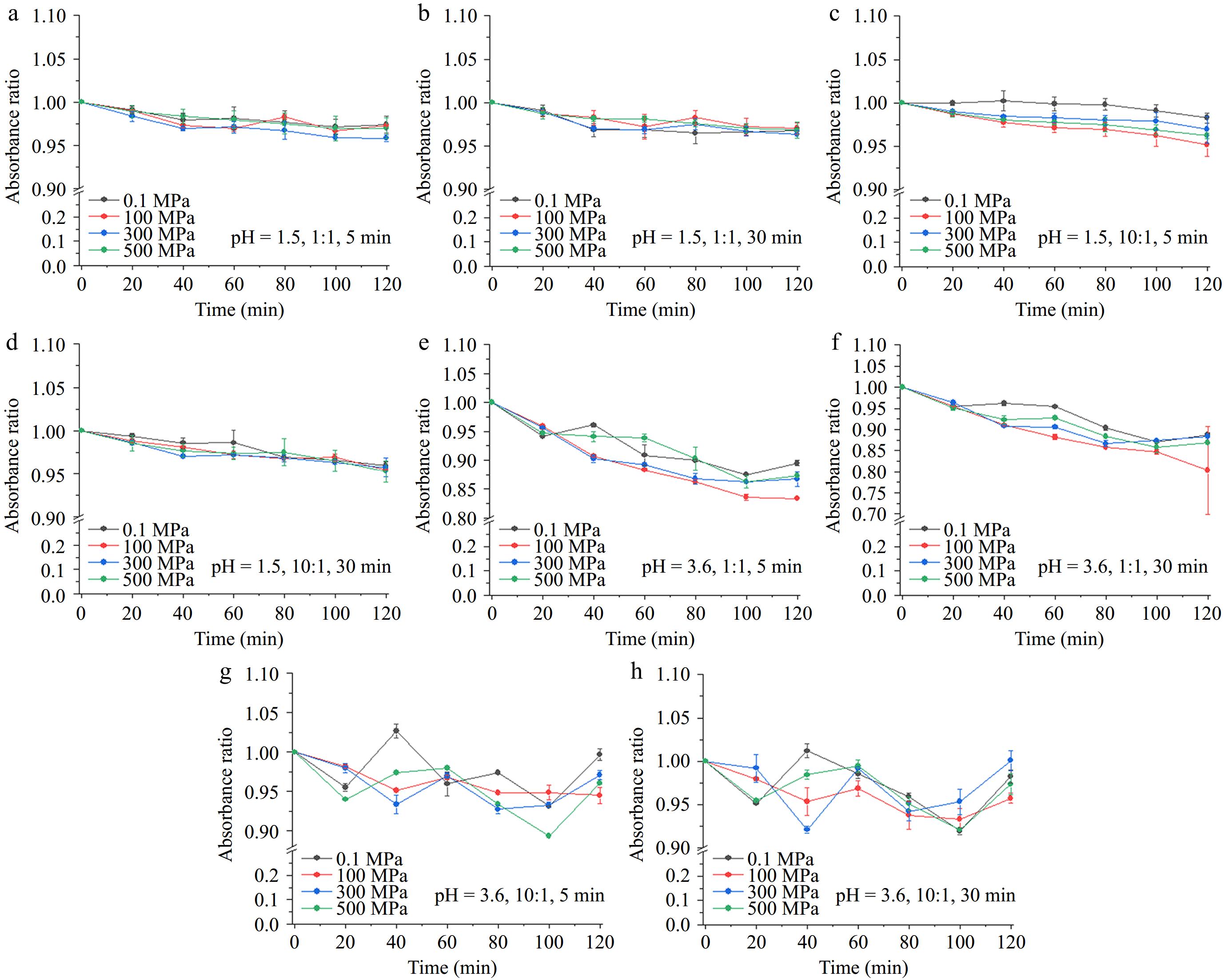

As shown in Fig. 2, at pH 1.5, the absorbance of copigmentation solutions slightly decreased with a longer processing time. In contrast, at pH 3.6, the light stability of the copigmentation complex exhibited different trends: a significant decrease in absorbance at a 1:1 molecular ratio, while a 10:1 ratio resulted in fluctuating absorbance changes. The general linear model analysis results indicated that only the condition of light processing time had no significant effects on the solution absorbance when in a solution pH of 1.5. While absorbance decreased markedly with a molecular ratio of 1:1 and solution pH of 3.6, a higher molecular ratio caused a more complex situation. Light processing might increase the solution absorbance at first and then decrease, and the solution absorbance peak time varied among different high pressures. Short-term light exposure may enhance the intermolecular interactions of the copigmentation complex or free anthocyanins (such as hydrogen bonding or π-π interactions), promoting the extension of the conjugated system and leading to an increase in absorbance. Prolonged exposure to sunlight affects the stability of anthocyanins, resulting in degradation and a decrease in absorbance values[30]. To be more specific, the processing time of 500 MPa has significant effects with other pressures, but the pressure of 0.1 and 300 MPa have the same effects on the solution absorbance. Previous studies have suggested that HPP may not affect the stability of anthocyanins themselves or the copigmentation effects of polyphenols such as epicatechin and gallic acid on anthocyanins[31,32]. However, Chen et al. found that 300 MPa HPP treatment reduced the stability of copigmented Vitis amurensis anthocyanins[33]. Due to the influence of hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic bonding, HPP may lead to different stability outcomes for various polyphenol-anthocyanin complexes.

Figure 2.

Light processing on the absorbance changes of pelargonidin-3-glucoside/catechin complex. (a)−(d) Copigmentation conditions: pressures of 0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa, processing time of 5 and 30 min, solution pH of 1.5 and catechin/pelargonidin-3-glucoside ratios of 1:1 and 10:1. (e)−(h) Copigmentation conditions: pressures of 0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa, processing time of 5 and 30 min, solution pH of 3.6 and catechin/pelargonidin-3-glucoside ratios of 1:1 and 10:1.

Taking all the above results into consideration, both thermal and light processing could decrease the solution absorbance of copigmentation complex, and flavonoid cations (pH 1.5) in complex structure showed comparatively higher thermal and light stability than the form of colorless hemiketals (pH 3.6). All the processing conditions (high pressure, solution pH, processing time, and molecular ratio) of copigmentation complex formation have significant effects on the solution absorbance, and the pressure of 500 MPa has different effects compared to the other pressures of 0.1, 100, and 300 MPa. In order to bridge the copigmentation complex structure and stability characteristics, the theoretical models were built, and their corresponding binding energy, weak interactions, and excited energy were calculated.

Theoretical models construction

-

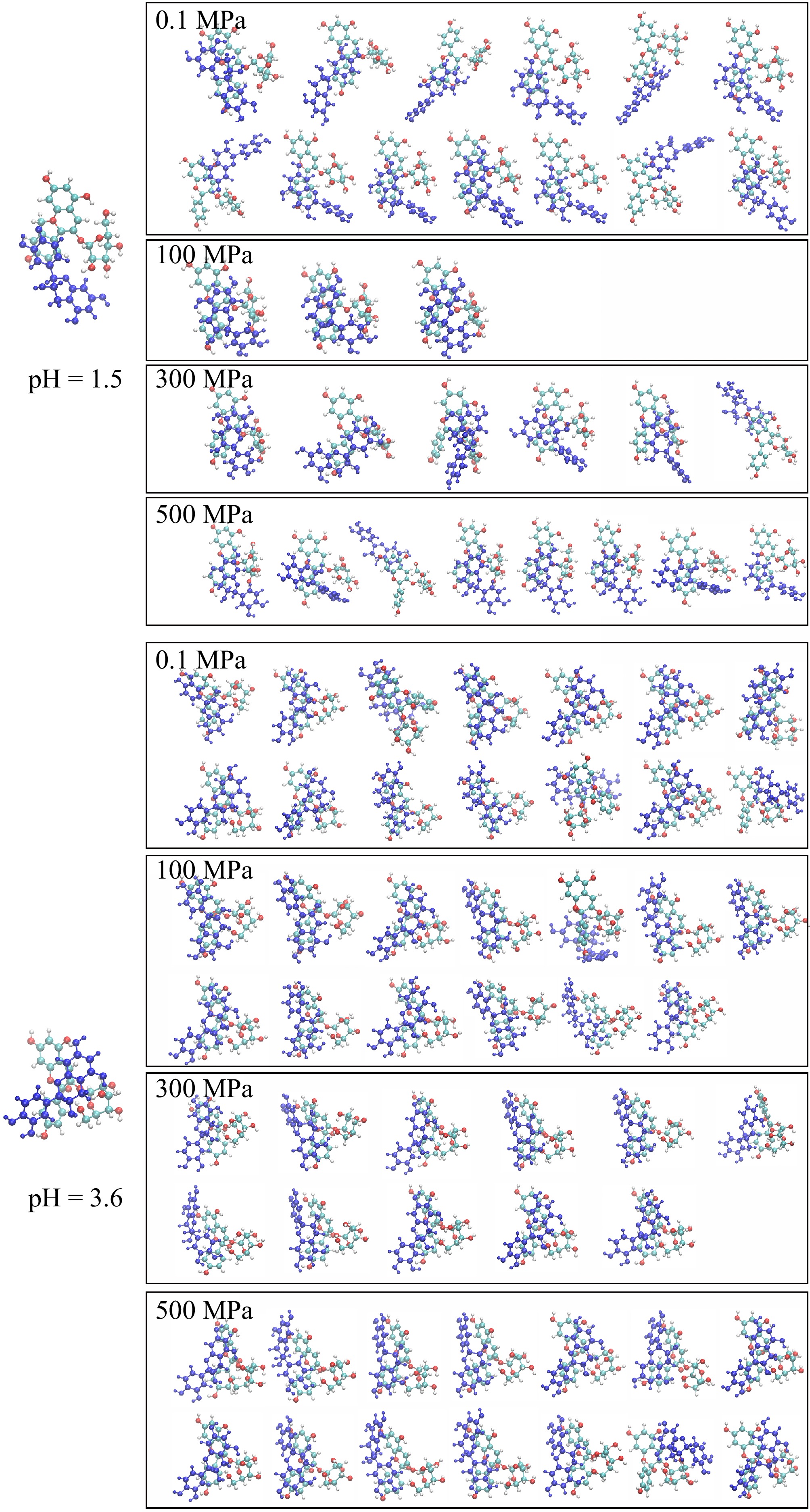

Conformation search is one of the effective methods to systematically study molecular structures and interactions; the initial conformation structures were generated and clustered with RMSD and energy, then the refined structures were simulated with molecular dynamic simulation, and the trajectories were extracted and processed with the same methods.

As shown in Fig. 3 (pH 1.5), the 13 structures were obtained at 0.1 MPa, and these conformation structures decreased to three typical structures at 100 MPa, six typical structures at 300 MPa, and eight typical structures at 500 MPa. Compared to 0.1 MPa, 500 MPa treatment reduced the number of complex structures and altered the dominant conformation, with the most stable π-π stacking conformation no longer present. It seems that high-pressure processing could decrease the conformation structure number and cause diversity structures. In most selected conformations, the A and C rings of catechin (blue) were positioned near the A and B rings of Pg-3-Glc, with minimal overlap at 0.1 MPa. But at 100 MPa, catechin exhibited greater overlap in three conformations, with nearly complete alignment of the A, B, and C rings. When in 300 MPa, predominantly in non-overlapping states with the A/C rings of catechin close to Pg-3-Glc were observed, and no overlapping conformations (the A/C rings of catechin close to the A/B rings of the anthocyanin) were observed at 500 MPa.

Figure 3.

Theoretic conformation structures of copigmentation complex at different pH (pH 1.5 and 3.6) and pressures (0.1, 100, 300, and 500 MPa).

Unlike the flavonoid cations form of anthocyanin (pH 1.5), the hemiketals form (pH 3.6) could generate more conformation of eleven to fourteen under different pressure conditions. All these structure characteristics showed the A/B/C rings of catechin almost all participated in overlapping with the main rings of the Pg-3-Glc, which may be related to the planar nature of the Pg-3-Glc. The two small molecules mainly exhibited overlapping conformations. At 0.1 MPa, the A, B, and C rings were individually matched. Under higher pressure, conformations were observed where catechin's A/B/C rings overlapped with the anthocyanin's A/B/C or B/A/C rings. Additionally, at 500 MPa, specific conformations of catechin positioned close to the glycosidic group of anthocyanin were also noted.

Binding energy analysis

-

Dealing with multiple conformational structures simultaneously remains a challenging task. Since the PM6 level was insufficient for accurate Boltzmann distribution calculations, all structures obtained from theoretical models were re-optimized using a higher computational level. Typical structures were then selected based on a proportion greater than 10%.

As shown in Table 1, all the conformation proportions greater than 10% were summarized. In the flavonoid cation form of anthocyanins (pH = 1.5), as pressure increased from 0.1 to 300 MPa, the cluster with the highest binding energy accounted for 41.99% to 88.92%, with a binding energy of −1,629,155.89 kcal/mol. At 500 MPa, the top three clusters comprised approximately 20%, and no dominant cluster structure was observed at the highest energy level. It seems that high pressure could increase conformation diversity and decrease the dominant structure proportion, which might be related to the comparative lower thermal stability (the most stable structure proportion was the lowest compared to other pressures). For hemiketals form in the copigmentation complex, a similar tendency was observed. High-pressure processing increased conformation diversity (more copigmentation complexes were identified at 500 MPa) and decreased the dominant structure proportion (distribution proportion decreased from 26.48%−34.56% to 15.53%). In addition, the binding energies of the higher proportion complexes at 0.1, 100, and 300 MPa were −1,676,753.25, −1,676,754.137, and −1,676,752.857 Kcal/mol, respectively, with 500 MPa showing the lowest binding energy of −1,676,755.904 Kcal/mol, and all these binding energies under different pressure conditions were lower than those of pH 1.5, this may be in correlated with the lower thermal stability of hemiketals form (pH 3.6).

Table 1. Binding energy and proportion of catechin and pelargonidin-3-glucoside copigmentation complex analysis.

Anthocyanin form Pressure Binding energy (ΔE (Kcal/mol)) /

Boltzmann distribution proportion (%)Flavonoid cations (pH 1.5) 0.1 0/41.99% + 1.62/19.74% 100 0/62.24% + 2.39/24.62% + 2.45/10.72% 300 0/88.92% 500 0/22.56% + 1.39/20.25% + 2.15/18.54% Hemiketals (pH 3.6) 0.1 0/34.56% + 2.65/12.30% 100 0/26.48% + 0.40/20.57% 300 0/29.64% + 0.39/24.86% 500 0/15.53% + 1.01/12.62% + 2.00/12.05% The values for each cluster's binding energy are given as differences from the energy of the first cluster. Weak interactions analysis

-

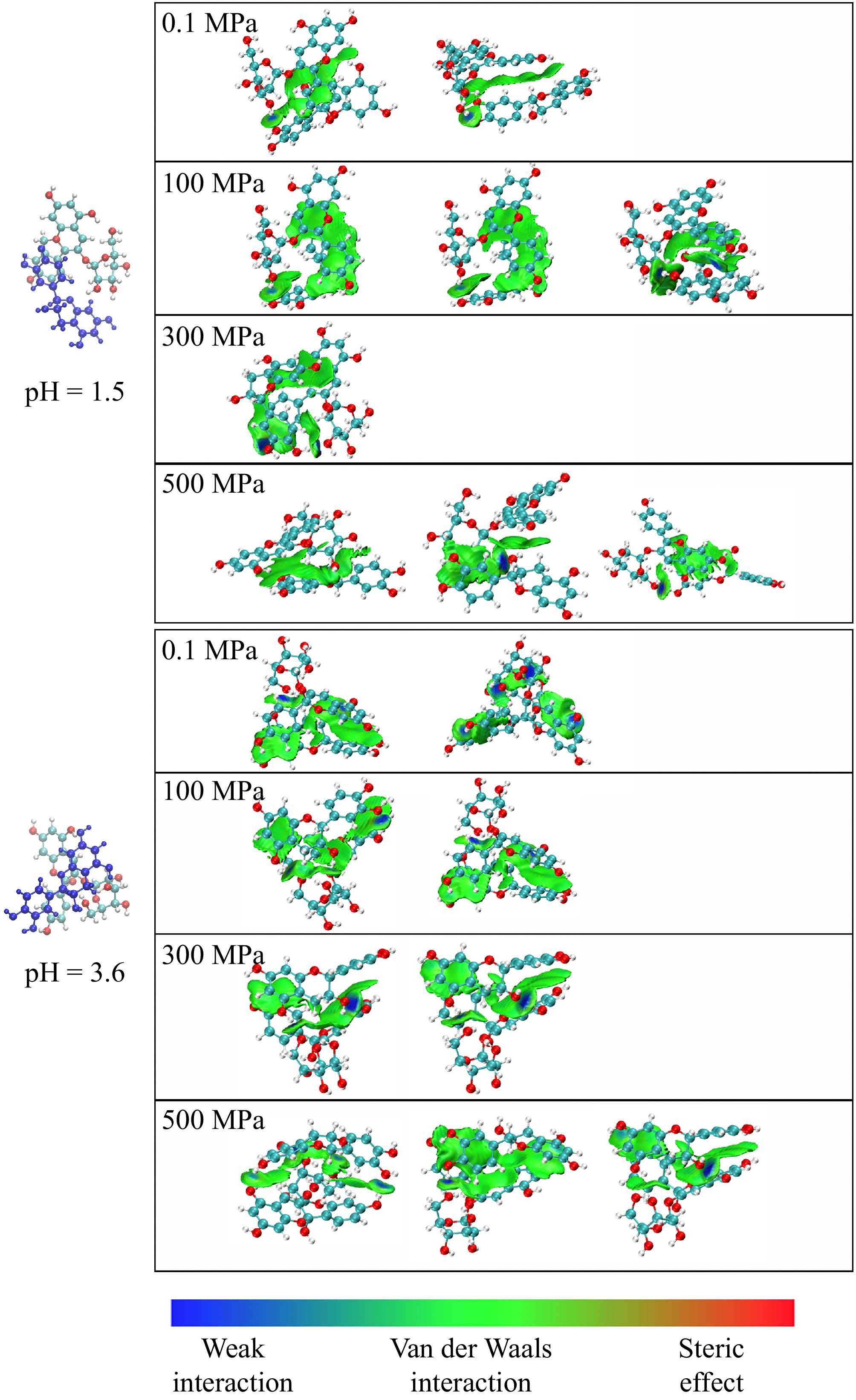

Former studies focusing on the copigmentation interactions have proved that flavonoids could form π-conjugated systems with anthocyanins, with their similar tricyclic structure (rings A, B, and C) and functional groups (aromatic rings, hydroxyl/methoxy groups as electron donors, and ketone/C=C double bonds as electron acceptors). The non-covalent interactions, including π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and charge-transfer interactions, can protect anthocyanins from nucleophilic attack by water and enhance copigmentation[8,34].

As shown in Fig. 4, the Independent Gradient Model based on Hirshfeld Partition (IGMH) analysis using Multiwfn was conveyed to study the weak interactions between catechin and Pg-3-Glc. The analysis revealed that van der Waals interactions (green regions) predominantly govern the interactions between the rings of catechin and Pg-3-Glc. Weak interactions, such as hydrogen bonds (blue regions), occur between some hydroxyl and other polar groups, with fewer interactions observed on the glycosidic chain. The analysis of the copigmentation complex (flavonoid cations, pH 1.5) showed that ring stacking interactions were primarily dominated, while another conformation shows lower stacking but maintains hydroxyl interactions at 0.1 MPa. At pressures of 100 and 300 MPa, van der Waals interactions dominate the intermolecular interactions, and weak interactions of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups were observed in 500 MPa. At pH 1.5, the 500 MPa treatment altered the dominant conformation of the copigmentation complex, with the most stable π-π stacking conformation no longer present and primarily existing in a non-overlapping configuration. This increased the distance between the aromatic rings of pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin, reducing van der Waals interactions such as π-π stacking. Meanwhile, as high-pressure treatment compresses intermolecular distances, more hydrogen bonds are formed[28,35]. For hemiketals copigmentation complex analysis, the stacking conformations were mainly governed by van der Waals interactions, with a broader interaction area and generating more mutual attraction forces under all pressure conditions[36]. Additionally, the frequent occurrence of blue regions in lower-pressure conditions suggested that hydrogen bonding may enhance non-covalent interactions, thereby increasing the stability of the anthocyanin complex[36].

Figure 4.

IGMH analysis of the copigmentation complexes. Blue for prominent attractive weak interactions (i.e., hydrogen bond interactions), green for van der Waals interactions, and red for prominent repulsion interactions.

Excited state analysis

-

Table 2. Excitation energies and f values of catechin and pelargonidin-3-glucoside copigmentation complex analysis.

Anthocyanin form Pressure Excitation energy (kcal/mol) / f value Flavonoid cations

(pH 1.5)0.1 −1,629,053.23/0.0124; −1,629,055.289/0.0145 100 −1,629,051.52/0.0167; −1,629,051.02/0.0163; −1,629,054.80/0.0206 300 −1,629,053.84/0.0205 500 −1,629,050.78/0.0108; −1,629,058.72/0.0205; −169,058.75/0.0159 Hemiketals (pH 3.6) 0.1 −1,676,566.20/0.2953; −1,676,555.15/0.4919 100 −1,676,558.15/0.3658; −1,676,566.23/0.2882 300 −1,676,565.66/0.3675; −1,676,566.22/0.2954 500 −1,676,555.15/0.4918; −1,676,565.75/0.3438; −1,676,561.94/0.3165 The values for each cluster's excitation energy are given as differences from the energy of the first cluster. The light stability of anthocyanins is in relationship with the calculated excitation energy; higher excitation energy indicates the complex might have higher light stability. For the flavonoid cations (pH 1.5) analysis (Table 2), the excitation energy of the dominant complex was −1,629,053.23 kcal/mol, while the number increased to −162,9051.52 kcal/mol when in pressure of 100 MPa, and almost all these selected complex exhibit lower excitation energies, which might reflect the comparatively high stability. When in 300 MPa, the excitation energy was similar to those at 0.1 MPa, and the 500 MPa condition lost the dominant structural ratio, reducing the complex stability for elevating the excitation energy (−1,629,050.78 kcal/mol). For hemiketals form (pH 3.6) analysis, the excitation energy of the dominant complex at 0.1 MPa was −1,676,566.20 kcal/mol, and the excitation energies ranged from −1,676,555.15 to −1,676,566.23 kcal/mol at higher pressures (100 MPa and above). The excitation energies of almost all the select complexes at 100 MPa were lower than those at 0.1 MPa (−1,676,558.15 kcal/mol), and these complexes showed comparatively higher values at 300 and 500 MPa; all these excited energies were lower than the flavonoid cations form. All these results indicated that high-pressure processing causes diversity structures with different percentages, with overall lower excitation energy compared to the ones at the atmosphere level, which might be related to the comparatively lower light stability.

-

High-pressure processing increases the copigmentation reaction rates between pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin and leads to more copigmentation complex formation by intramolecular structural rearrangements (such as the reformation or breaking of hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and charge-transfer interactions). The anthocyanin form (pH), molecular ratio, high pressure, and treatment time have significant effects on the complex thermal and light stability. Flavonoid cations/catechin complexes have higher light and thermal stability than the hemiketals/catechin complex; a higher molecular ratio sometimes leads to more copigmentation formation, but these formed copigmentation complexes might show less stability. It is obvious that high-pressure processing increased the copigmentation complex diversity and decreased the dominant complex proportion with the lowest binding energy (no dominant complex exists in 500 MPa). In addition, van der Waals interactions dominate the intermolecular interactions, and high-pressure processing changes the overlapping areas, affecting the weak interactions and binding energy, as well as the excited characteristics, which were in relationship with the light stability and affected by the copigmentation structure. To summarize, copigmentation complexes formed under HPP contain more dominant structures, and these higher-energy complexes exhibit lower thermal and light stability.

This work was supported by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-IVFCAAS, IVF-JCKJ202514).

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhang W, Chen Y; methodology: Zhang W; data curation: You F, Gao L; writing − original draft: Zhang W; writing − review and editing: Zou H, Chen Y; supervision: Zou H, Chen Y; funding acquisition: Zou H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Wenyuan Zhang, Fei You

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang W, You F, Gao L, Zou H, Chen Y. 2025. Thermal and light stability of pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin copigmentation complex from high-pressure processing: effects of high-pressure processing conditions on complex conformation and structure characteristics. Food Innovation and Advances 4(2): 266−273 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0025

Thermal and light stability of pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin copigmentation complex from high-pressure processing: effects of high-pressure processing conditions on complex conformation and structure characteristics

- Received: 28 December 2024

- Revised: 06 March 2025

- Accepted: 07 March 2025

- Published online: 26 June 2025

Abstract: Former research has shown that high-pressure processing (HPP) accelerates copigmentation reaction rates between pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin, increasing solution absorbance. However, the structural characteristics of these complexes and HPP's effects on their conformations remain unclear. This study prepared pelargonidin-3-glucoside and catechin complexes under varying pH, molar ratios, and high pressures, followed by separate light and heat treatments. Solution absorbance was measured, and molecular cluster structures and corresponding characteristics were analyzed to explain stability under HPP conditions. The results indicated that HPP-induced copigmentation complexes show reduced thermal and light stability, along with increased conformational diversity and a decreased proportion of dominant structures (from 41.99%−88.92% to 22.56% at pH 1.5, and from 26.48%−34.56% to 15.53% at pH 3.6). The primary interaction between catechin and Pg-3-Glc was van der Waals forces unaffected by HPP. Additionally, HPP lowered excitation energies in flavonoid cations (pH 1.5) and increased energies in hemiketals (pH 3.6).

-

Key words:

- High pressure processing /

- Pelargonidin-3-glucoside /

- Catechin /

- Copigmentation /

- Thermal stability /

- Light stability