-

Rhizomes of bermudagrasses (Cynodon spp.) serve as storage organs for meristems and resources that allow them to regrow after disturbances[1,2] and can survive in bushfires or flooding conditions for several weeks, whilst other reproductive organs such as seeds and aboveground stolons are vulnerable[2]. An extensive rhizome system also promotes drought resistance and post-harvest regrowth rate[3,4], even in mild temperate conditions[5]. The extensive rhizome system is often considered as the most desirable trait in the breeding of bermudagrass for pastures and turfgrass[1,4].

Rhizomes can become dormant for seven months in prolonged drought and still have the capacity to rapidly produce roots and stolons under the least favourable watered conditions[2,6,7]. The growth of an extensive rhizome system of bermudagrass seems to be an adaptive trait to cope with arid climates[8,9]. An increase in carbon supply to rhizomes in a short growth period due to a short rainy season in arid regions may be associated with shoot traits that have evolved as an adaptive divergence[10,11].

A large variation in rhizome growth among approximately 1,000 naturalised bermudagrass ecotypes collected from diverse environments have been identified in Australia[12,13]. Existing phylogenetic analyses in previous research confirmed that these grass populations derived from multiple historical introductions[13], which provides evidence of the essential genetic diversity of evolutionary timelines for local adaption in Australia. Therefore, these genotypes may have evolved to adapt to the diverse habitats that feature large variations in aridity indices[14], and annual rainfall[15] in Australia. A previous study using bermudagrasses collected in Australia reported that ecotypes with a larger rhizome production during establishment had a higher fraction of biomass allocated from the shoots[4]. Variation in shoot traits among grass ecotypes originating from varied environments are strongly associated with species functional trade-offs for the growth of plant organs[16−18]. For example, the delayed development of leaf clusters along spreading stolons is associated with the length of internodes and the growth of stolons[19]. These characteristics may adversely affect the biomass allocation for the growth of rhizomes during establishment.

Growth responses of plant ecotypes originating from varying environments can be assessed under identical environmental conditions[11,20,21]. Previous field experiments on bermudagrass ecotypes revealed a consistent ranking of rhizome growth between the subtropical and Mediterranean environments[3], indicating that environmental plasticity in rhizome size is low. In addition, plasticity in the rhizome and belowground growth is low regardless of factors such as nutrient variations[22] or seasonal variations in temperatures and sunlight[23]. These findings suggest that screening bermudagrass ecotypes according to rhizomes may not be affected by experimental conditions.

The objectives of this study were to analyse variation in rhizome growth of bermudagrass ecotypes collected from areas with various aridity indices, to examine relationships between rhizome growth and the environmental conditions of their native habitats, and to characterise other traits correlated with rhizome growth. This study hypothesised that during establishment, rhizome growth of bermudagrass ecotypes from arid environments would be more rapid than ecotypes from non-arid environments.

-

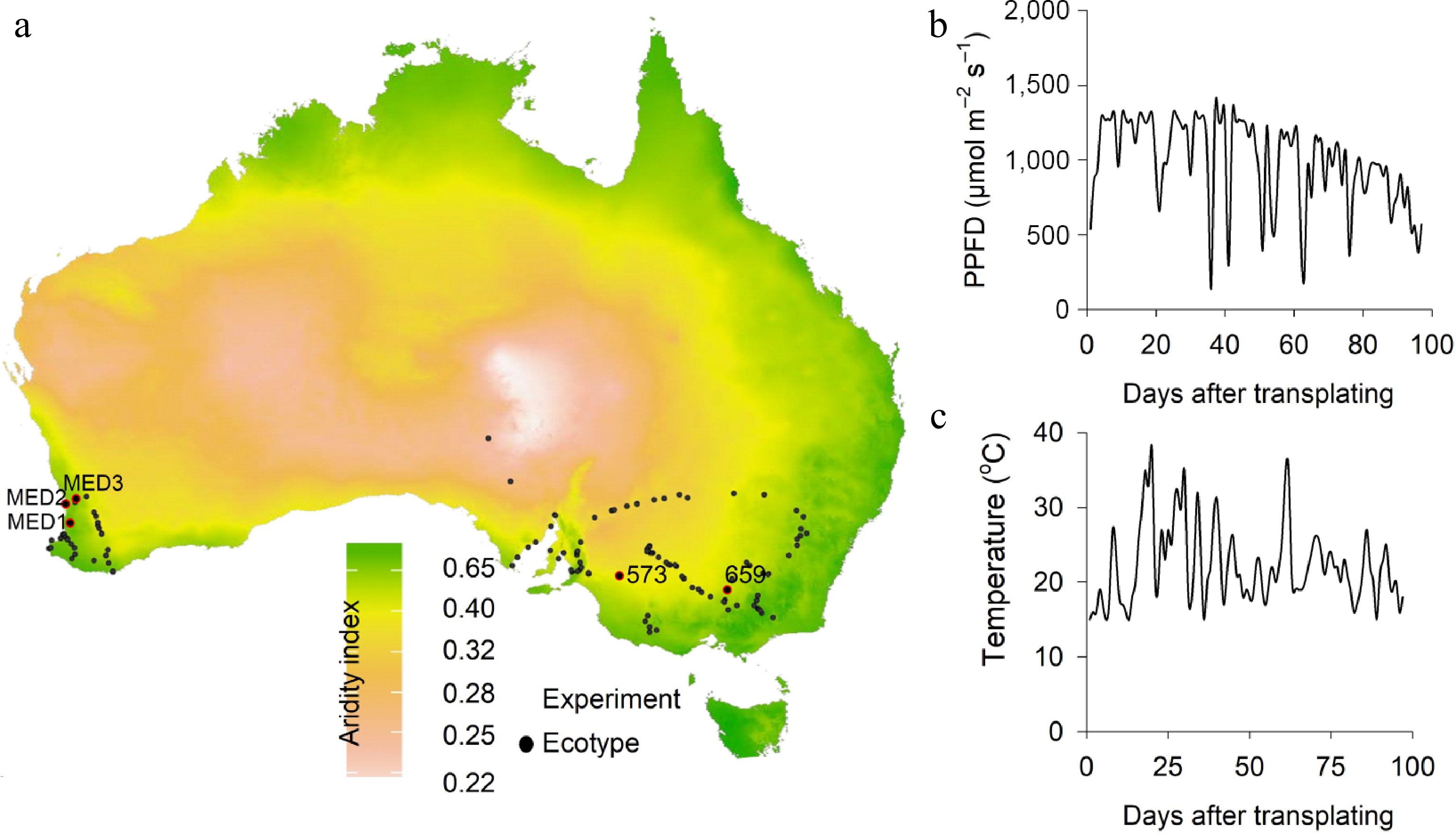

A total of 142 naturalised bermudagrass ecotypes, collected from temperate regions of Australia between latitudes 29° S and 37° S (Fig. 1a), were studied. These regions experience predominantly winter rainfall, with considerable variation in total precipitation[15]. Additionally, the aridity index varies significantly across these regions (Fig. 1a)[14], with recorded values ranging from 0.10 to 2.50. An aridity index of 0.10 indicates a hyper-arid climate where annual rainfall is only 10% of evapotranspiration, whereas an aridity index of 2.50 indicates a humid climate with annual rainfall 2.5 times greater than the potential water evapotranspiration. The ecotypes were collected from environments characterised by annual mean temperatures of 20 to 25 °C, annual rainfall between 100 and 1,500 mm, and reference evapotranspiration ranging from 590 to 1,340 mm year−1.

Figure 1.

(a) Geographical distribution of bermudagrass ecotypes. Environmental conditions during the experiment: (b) sunlight measured as photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), and (c) daily temperature. The aridity index map was adapted from Casadebaig et al.[14]. Climatic data were obtained from the Roseworthy SA station[15].

Among these, five ecotypes: MED1, MED2, MED3, 573, and 659, were used as reference materials as they possess documented drought resistance mechanisms. More specifically, these genotypes previously exhibited high rhizome dry weight production during establishment, a key trait contributing to drought resistance in mature plants[3,4]. Given their documented drought resistance mechanisms, these ecotypes were included as reference materials in the present study. To ensure the reliability of the present findings, despite the absence of site-level replication, all ecotypes were clonally propagated from stolon cuttings under standardized conditions, thereby minimizing environmental variability associated with their original collection sites[24,25].

An experiment was conducted using pots during summer from 1 December 2019 to 16 March 2020 (photosynthetic photon flux density and daily temperature in Fig. 1b & c). Multiple cuttings of each genotype were transplanted into each pot (10 cm width × 10 cm length × 14 cm depth) to ensure successful rooting; then, rooted cuttings were reduced to two plants pot−1 (three pots genotype−1), at 2 weeks after transplanting. Pots were arranged outdoors on benches (0.8 m height), and filled to 1.47 kg L−1 density with the University of California at Davis mix (UC mix), produced by the South Australian Research and Development Institute at Waite. One cubic meter of UC mix consisted of 0.56 m3 Waikerie sand, 0.44 m3 Canadian peat moss, 0.80 kg hydrated lime, 1.33 kg agricultural lime, 3.00 kg Osmocote Exact Mini (6 N + 3.5 P + 9.1 K + TE) (from Fernland, Yandina, QLD 4561 Australia). The UC mix contained 0.48 g L−1 N, 0.19 g L−1 P, and 0.61 g L−1 K[26], and 25.1 v/v % volumetric water content at field capacity[27]. No additional fertilizers were applied during the experiment beyond the slow-release Osmocote Exact Mini included in the initial UC mix. During the experiment, grasses were irrigated to saturation twice per day. This high irrigation frequency was essential to prevent drought stress, given the small pot volume, outdoor bench placement, and high summer temperatures during the experiment (Fig. 1c). Grass ecotypes were cut at 1 cm above the ground at six weeks after transplanting to measure first shoot dry weight. The two longest stolons of cut shoots from the outdoor experiments were selected to measure stolon length, length of the first two internodes, leaf length, and leaf width of the first leaves from the first and second nodes. After the analyses, shoot samples were oven-dried for shoot dry weight. A destructive harvest was conducted on 16 March 2020 to measure the dry weight of rhizomes, roots, and shoots (second shoot dry weight).

Rainfall, reference evapotranspiration, and temperatures at the origin for each ecotype were obtained from analysing data of 20-to-50 year records by weather stations nearest to their collection sites (Fig. 1a)[15]. The aridity index was calculated as the ratio of rainfall over reference evapotranspiration. Habitats with aridity indices less than 0.65 were classified as arid, based on the FAO aridity index and Köppen–Geiger classification[28]. Accordingly, 96 ecotypes of bermudagrasses were categorised as being from arid environments, and 46 ecotypes were from non-arid environments (Fig. 1a).

Rhizome dry weight was analyzed for significant differences among ecotypes using GenStat 20th Edition (VSN International, Hemel Hempstead, UK, 2019). Mean comparisons were conducted using Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) test at p < 0.05. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed to examine relationships between rhizome dry weight, plant traits, and bioclimatic variables, including aridity index, annual rainfall, and reference evapotranspiration. Additionally, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted using Sigmaplot 14.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA, 2017) to differentiate bermudagrass ecotypes from arid and non-arid regions. Correlation analysis and PCA were employed to examine relationships between rhizome traits and bioclimatic variables, reducing the necessity for direct comparisons between collection sites.

-

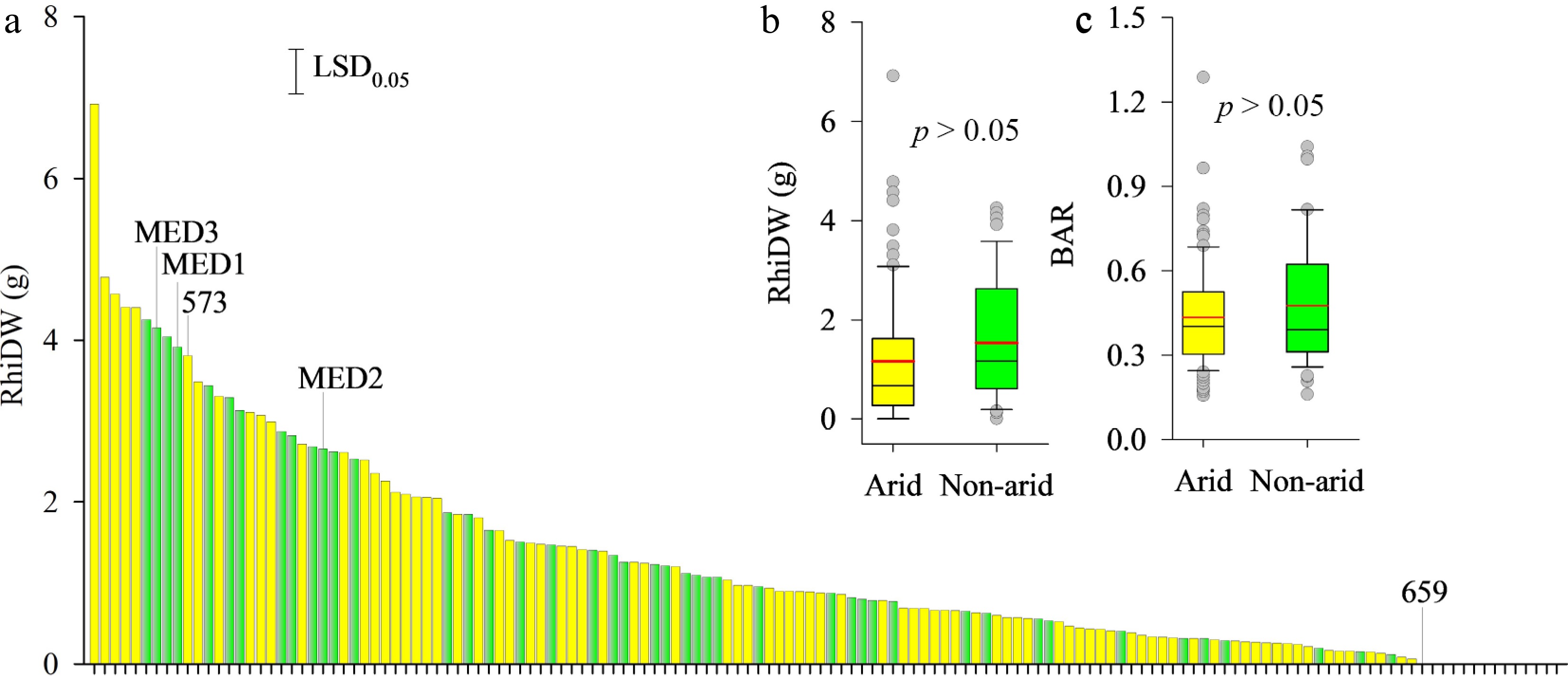

Rhizome dry weight varied significantly among 142 bermudagrass ecotypes (p < 0.001, Fig. 2a), with substantial variation both between ecotypes and within those from arid regions. Ecotypes with the highest rhizome dry weight originated from arid regions. At harvest, 87.5% of ecotypes from arid regions and 95.7% from non-arid regions developed rhizomes. However, rhizome dry weight and belowground-to-aboveground dry weight ratios did not differ significantly between arid and non-arid regions (p > 0.05, Fig. 2b & c).

Figure 2.

(a) Variation in rhizome dry weight (RhiDW) of 142 bermudagrass ecotypes, and the comparison of bermudagrass ecotypes collected from arid (yellow) and non-arid (green) regions for (b) RhiDW, and (c) belowground-to-aboveground biomass ratio (BAR).

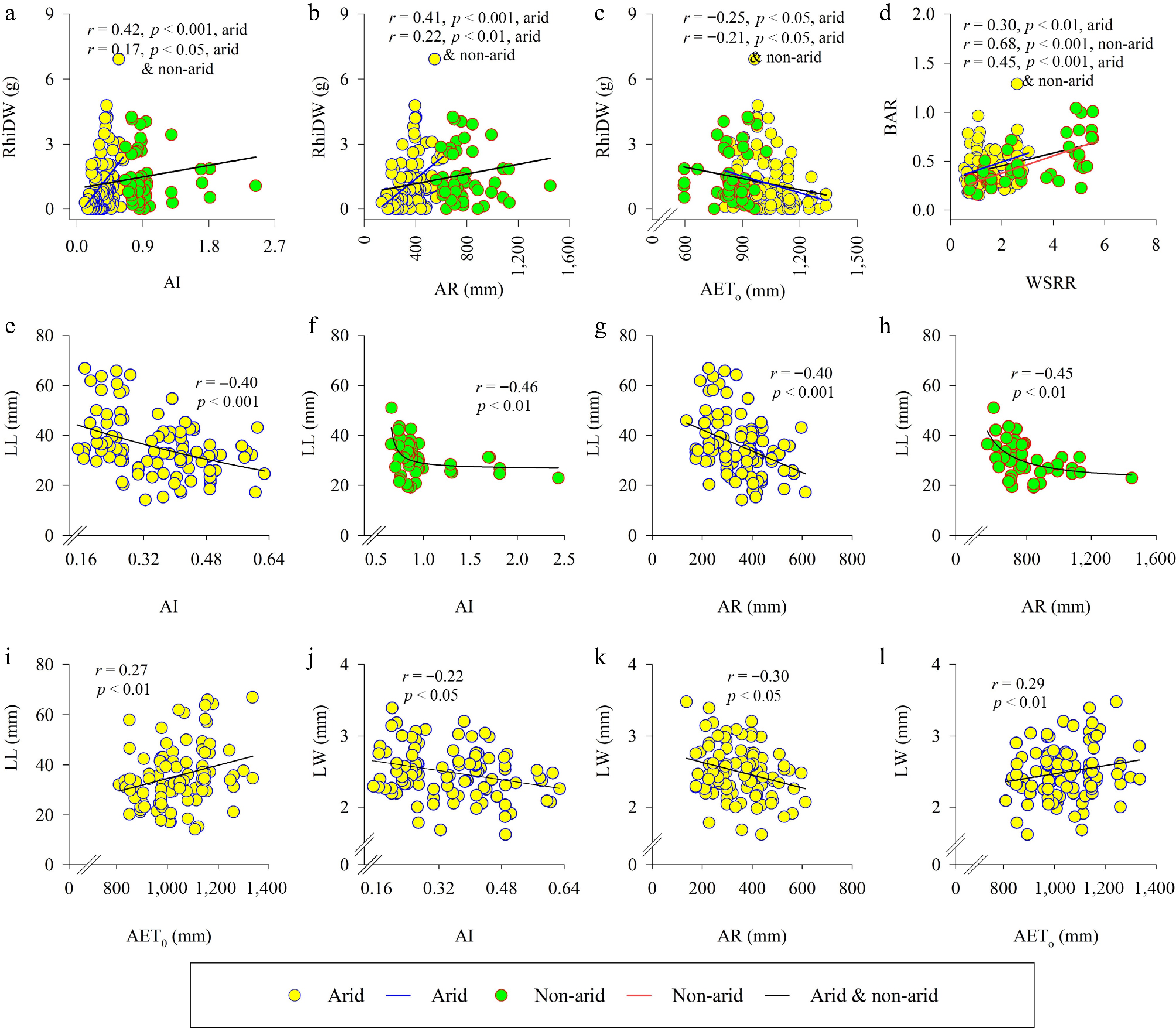

Correlation analyses revealed distinct responses of rhizome dry weight, leaf length, and leaf width to the environmental conditions of their native habitats for bermudagrass ecotypes from arid and non-arid regions, respectively. In arid ecotypes, rhizome dry weight was positively correlated with the aridity index (r = 0.42, p < 0.001) and annual rainfall (r = 0.41, p < 0.001) but negatively correlated with annual reference evapotranspiration (r = −0.25, p < 0.05). When considering both arid and non-arid ecotypes, these correlations remained significant but weaker (aridity index: r = 0.17, p < 0.05; annual rainfall: r = 0.22, p = 0.01; evapotranspiration: r = −0.21, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3a–c). However, these relationships were not observed in ecotypes from non-arid environments (Supplementary Table S1 and S2). A consistent trend across all ecotypes was a positive correlation between the belowground-to-aboveground dry weight ratio and the winter-to-summer rainfall ratio (arid: r = 0.30, p < 0.01; non-arid: r = 0.68, p < 0.001; combined: r = 0.45, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Rhizome growth and leaf dimensions of bermudagrass ecotypes in arid and non-arid regions in response to the climatic conditions of their native habitats: relationships between (a) rhizome dry weight (RhiDW) and aridity index (AI), (b) annual rainfall (AR), (c) annual reference evapotranspiration (AETo), and (d) belowground-to-aboveground biomass ratio (BAR) and winter to summer rainfall ratio (WSRR); relationships between leaf length (LL) and (e), (f) AI, (g), (h) AR, and (i) AETo; relationships between leaf width (LW), and (j) AI, (k) AR, and (l) AETo. Leaf dimensions in (e)–(l) were measured in the first leaf at the first node.

The relationships between leaf length and width, and bioclimatic variables of the native habitats differed between bermudagrass ecotypes from arid and non-arid environments (Fig. 3e–l). A common trend across both regions was that leaf length was negatively correlated with the aridity index (arid: r = −0.40, p < 0.001; non-arid: r = −0.46, p < 0.01), and annual rainfall (arid: r = −0.40, p < 0.001; non-arid: r = −0.45, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3e–h). However, in arid ecotypes only, leaf length was positively correlated with annual evapotranspiration (r = 0.27, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3i), while leaf width was negatively correlated with annual reference evapotranspiration (r = −0.22, p < 0.05) and the aridity index (r = −0.30, p < 0.05) but positively correlated with annual rainfall (r = 0.29, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3j–l).

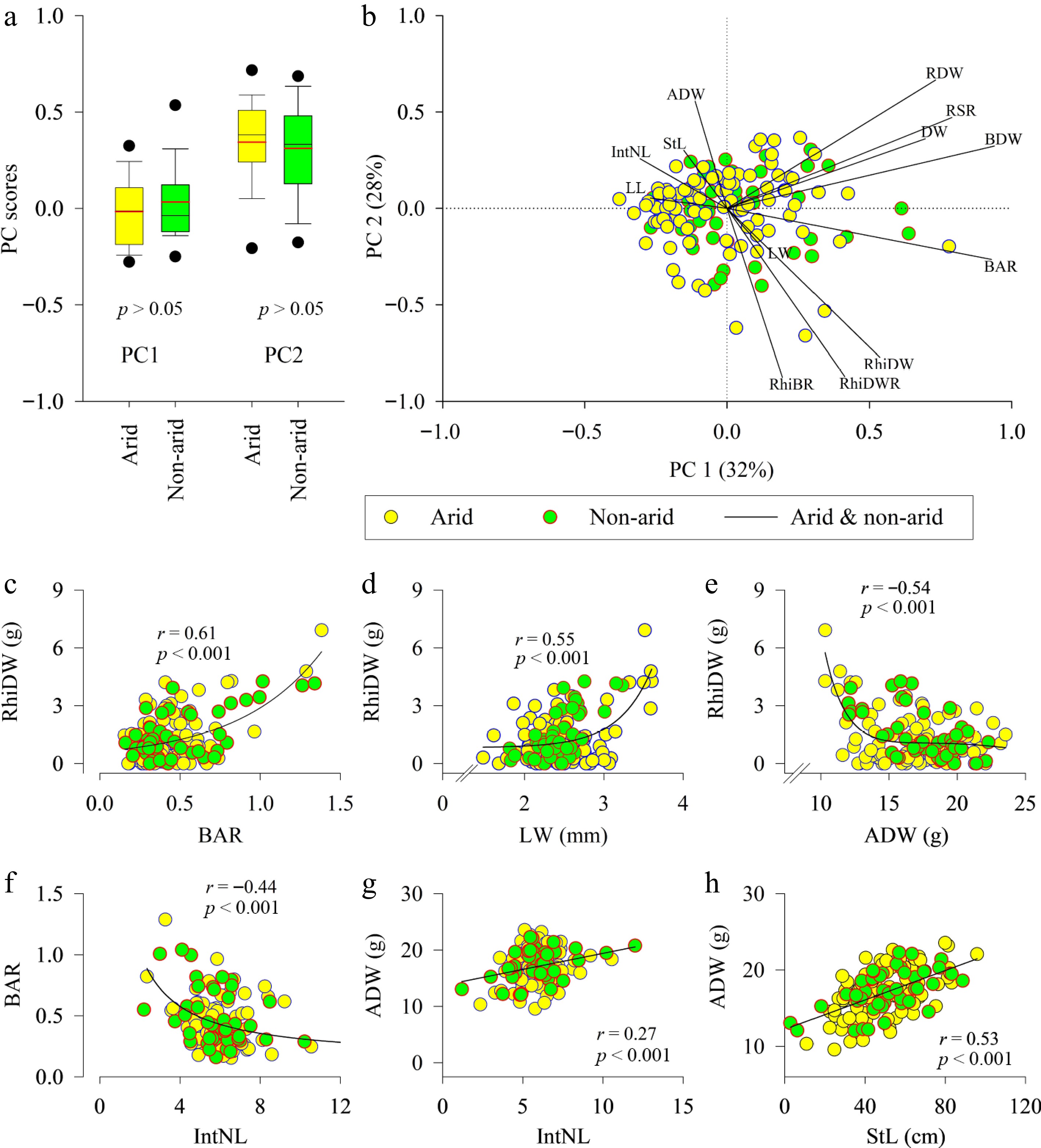

PCA analysis revealed no significant differences between PC scores of grasses from arid and non-arid regions (p > 0.05, Fig. 4a). Some bermudagrass ecotypes from both environments had high PC scores values in PC 1 (32%) that captured positive loadings on rhizome dry weight, belowground to aboveground dry weight ratio, root to shoot dry weight ratio, and belowground dry weight (Fig. 4b). Similarly, PC scores of some ecotypes had large values of aboveground dry weight, stolon length, and internode length in positive loading of PC2 (28%).

Figure 4.

Correlations of the measured traits among bermudagrass ecotypes. PCA analysis was conducted using the traits of stolon length (StL), internode length (IntNL), leaf width (LW), leaf length (LL), belowground to aboveground dry weight (ADW), belowground dry weight (BDW), rhizome dry weight (RhiDW), root dry weight (RDW), total dry weight (DW), belowground-to-aboveground biomass ratio (BAR), root to shoot ratio (RSR), rhizome to belowground ratio (RhiBR), and rhizome to total dry weight ratio (RhiDWR). Relationships between rhizome dry weight (RhiDW) and belowground to aboveground dry weight ratio (BAR). (a) the PC scores comparison and (b) PCA biplot of grasses from arid region (aridity indices less than 0.65) and non-arid region. The regression of RhiDW vs (c) BAR, vs (d) LW, and vs (e) ADW, (f) BAR vs IntNL, and (g) ADW vs IntNL and vs (h) StL.

In both groups, rhizome dry weight significantly increased with a higher ratio of belowground to aboveground dry weight (r = 0.61, p < 0.001), leaf width (r = 0.55, p < 0.001), but significantly decreased with increasing aboveground dry weight (r = −0.54, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4c–e). Moreover, the ratio of belowground to aboveground dry weight significantly decreased with greater internode length (r = −0.44, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4f). Aboveground dry weight significantly increased with increased internode length (r = 0.27, p < 0.01) and increased stolon length (r = 0.53, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4g & h).

-

Rhizome weight at the end of the 14-week experiment was similar for the ecotypes collected from arid and non-arid environments. This result suggests that the arid environment of the native habitats alone may not facilitate the adaptive divergence of Cynodon spp. toward increased rhizome development. Instead, significant genotypic variability in rhizome growth among all ecotypes was observed, and associated with preferential belowground growth to aboveground growth during the establishment, as indicated in Fig. 4c. Bermudagrass ecotypes with more rapid aboveground growth tend to delay rhizome growth as reported in a previous study using 920 bermudagrass ecotypes collected in Australia[29], and another study using commercial bermudagrass cultivars[30].

The delay of rhizome growth might suggest a different adaptive mechanism suited to varied environments in Australia. In contrast, bermudagrass ecotypes with the rapid rhizome growth during the establishment exhibited preferential belowground allocation, as indicated in Fig. 4c. This variation in establishment strategy differs from mature growth patterns, as rhizome growth typically accelerates as these grasses mature in the second year of establishment[30−32].

In previous studies that included the same reference ecotypes as this study, 573 bermudagrass ecotypes originating from arid environments with sandy profiles allocated a greater proportion of assimilates to rhizomes than shoots[3,4]. In the present study, bermudagrass ecotypes with the largest rhizome dry weights originated from arid environments. The rapid rhizome development observed in these ecotypes may be an adaptive trait that enhances survival under extreme climatic conditions, as suggested by previous research on bermudagrass ecotypes in Australia[4,8,13].

Rhizome growth in arid regions significantly decreased as the evapotranspiration in these habitats increased. However, the positive responses of rhizome growth to increasing aridity index and rainfall indicated that bermudagrass ecotypes from arid and non-arid regions may have had a long-term adaptation to their local ecosystems. This study also found that neither aridity index nor annual rainfall was correlated with root dry weight (p > 0.05, Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, the positive responses of rhizome growth to wetter climate conditions (specifically higher annual rainfall and a higher aridity index) in arid environments can be a mechanism of adaptive evolution. Rhizome growth during the wet season is the most reliable survival strategy of bermudagrass ecotypes to adapt to the arid environment with a large rainfall variation and high evapotranspiration[7,8,13]. The rainfall in the regions where the ecotypes were collected ranges between 50 and 150 mm during the winter, dropping to below 10 mm for the rest of the year[15], which could explain why the winter to summer rainfall ratio was positively correlated with belowground to aboveground dry weight ratio.

Through long-term adaptive evolution, bermudagrass ecotypes in the arid region may have enlarged leaves to optimise net photosynthesis for rhizome growth during the rainy season, with higher water availability promoting growth and carbohydrate accumulation, indicated by the positive relationship between leaf width and rhizome growth. Enlargement of leaves can increase net photosynthesis that promotes the growth of asexual and sexual reproductive organs, such as rhizomes in bermudagrasses in this study or seeds of other crop species originating from arid regions[10,11,20,33]. Negative relations between belowground-to-aboveground biomass ratio and internode length/stolon length were also found in the present study. Stolon expansion requires a large amount of fixed carbon to construct internodes, nodes, and tillers to establish leaf clusters[19,34]. Accordingly, an increase in internode length and shoot growth leads to reduced biomass allocation to belowground growth in bermudagrass in this research and other stoloniferous grass species in previous research[19,30,32,34,35]. Bermudagrass varieties from dry landscapes might have developed larger leaves as an evolutionary adaptation to promote better underground stem development[29,36,37].

Rhizome growth, which is closely linked to genetic diversity and adaptation to arid environments, can be strongly influenced by the wide polyploidy range observed in Cynodon spp. (diploid to hexaploid)[38]. The underlying variation in ploidy likely contributed to the substantial genotypic variability observed in this study and may have obscured potential differences between the arid and non-arid ecotype groups. The absence of ploidy determination represents a key limitation of our work. Future studies incorporating ploidy analysis will be essential to elucidate the role of chromosome number in driving variation in rhizome development among bermudagrass ecotypes.

-

This study revealed that rhizome growth was not significantly different between bermudagrass ecotypes from arid and non-arid regions, despite substantial genetic variation in rhizome growth among the ecotypes. Only rhizome growth of bermudagrass ecotypes from arid regions showed positive responses to more humid climate conditions, in which precipitation predominantly falls during the winter. The enlargement of leaf dimensions was likely a mechanism to optimise rhizome growth during the rainy season in arid regions. While one ecotype exhibiting the highest rhizome dry weight originated from an arid environment, increased rhizome growth was observed amongst ecotypes from both arid and non-arid environments. Those high-performing ecotypes can be valuable genetic resources for plant breeding, forage options, and recreational use.

The principal author, Chanthy Huot, is very grateful to the Australia Awards John Allwright Fellowship and Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research project SMCN/2012/075 for providing a PhD scholarship. Dr Yi Zhou and Dr Ruey Toh provided bermudagrass ecotypes for the experiment. Dr Judith Rathjen and Dr Ruey Toh assisted with logistical arrangements during the experiments and sample analyses. Mr Nasir Iqbal and Mr Allen Ho assisted with data collection. Mr Sothy Khiev produced the geographic map of plant distribution (Fig. 1a).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Huot C, Philp JNM, Zhou Y, Denton MD; data collection: Huot C, Zhou Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Huot C, Philp JNM, Zhou Y, Denton MD; draft manuscript preparation: Huot C, Philp JNM, Zhou Y, Denton MD. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) of studied bermudagrasses that included 11 reference cultivars and 137 genotypes. Plant variables include stolon length (StL), first internode length (INL1), second internode length (INL2), first leaf width (LW1), first leaf length (LL1), second leaf width (LW2), second leaf length (LL2), aboveground dry weight (SDW), belowground dry weight (RDW), rhizome dry weight (RhiDW), root dry weight (RDW), total dry weight (DW), belowground to aboveground dry weight (BAR), root to shoot ratio (RSR), rhizome dry weight to belowground dry weight ratio (RhiBR) and rhizome dry weight tot total dry weight ratio (RhiDWR). Climatic variables include annual rainfall (AR), annual mean temperature (AT), Winter rainfall (WR), winter to summer rainfall ratio (WSRR), annual evapotranspiration (AET), aridity index (AI). Symbols indicate *, significant at p < 0.05, **, significant at p < 0.01, ***, significant at p < 0.001, and ns, not significant.

- Supplementary Table S2 Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) of studied bermudagrasses that included 11 reference cultivars and 137 genotypes. Plant variables include stolon length (StL), first internode length (INL1), second internode length (INL2), first leaf width (LW1), first leaf length (LL1), second leaf width (LW2), second leaf length (LL2), aboveground dry weight (SDW), belowground dry weight (RDW), rhizome dry weight (RhiDW), total dry weight (DW), belowground to aboveground dry weight (BAR), root to shoot ratio (RSR), rhizome dry weight to belowground dry weight ratio (RhiBR) and rhizome dry weight tot total dry weight ratio (RhiDWR). Symbols indicate *, significant at p < 0.05, **, significant at p < 0.01, ***, significant at p < 0.001, and ns, not significant.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Huot C, Philp JNM, Zhou Y, Denton MD. 2025. Development of rhizomes in bermudagrass ecotypes is associated with environmental conditions of their native habitats. Grass Research 5: e031 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0027

Development of rhizomes in bermudagrass ecotypes is associated with environmental conditions of their native habitats

- Received: 07 April 2025

- Revised: 23 September 2025

- Accepted: 14 October 2025

- Published online: 17 December 2025

Abstract: The development of large rhizomes in bermudagrass ecotypes significantly contributes to drought tolerance and rapid recovery from severe drought. This study investigated the relationship between rhizome growth in bermudagrass (Cynodon spp.) ecotypes and the environmental conditions of their original collection sites. A total of 142 naturalised bermudagrass ecotypes were collected from the Australian continent, where the environments at their origins show minimal differences in average temperature but significant variation in rainfall. A 14-week pot experiment was carried out over the summer to assess rhizome dry weight (RhiDW), and the morphological characteristics of the shoots. There was no difference in rhizome dry weight (RhiDW) among ecotypes sourced from arid and non-arid areas, with the ecotype exhibiting the highest RhiDW originating from an arid region. Substantial rhizome development was linked to a higher annual rainfall in their native environments (r = 0.22), and this trend was enhanced for the ecotypes collected from arid zones (r = 0.41). Rhizome growth was positively associated with the belowground-to-aboveground biomass ratio (BAR, r = 0.61) and leaf width (r = 0.55), while BAR displayed a negative correlation with internode length (r = −0.44). These results imply that the drier environment of the native habitats did not drive the evolution of bermudagrass toward larger rhizome development. Broader leaves enhance rhizome growth and may serve as a key characteristic for breeding bermudagrass varieties with improved drought tolerance.

-

Key words:

- Arid ecosystems /

- Adaptive evolution /

- Drought resistance /

- Bermudagrass