-

Plants are subjected to a variety of abiotic stresses, including temperature extremes, drought, salinity, and flooding, all of which detrimentally impact their growth and development. Climate change has accelerated the frequency of extreme weather events, exacerbating these stresses and drastically reducing crop yields worldwide[1]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that land surface temperatures from 2011 to 2020 were 1.59 °C higher than those from 1850 to 1900, with an upward trend compared to 2003–2012 averages[2]. This trend is expected to continue in temperate regions, increasing the duration and intensity of heatwaves and heightening plant vulnerability. In addition to daytime temperature increases, rising nighttime temperatures have emerged as a major constraint to plant productivity, as they disrupt photosynthesis, respiration, and amino acid metabolism, ultimately accelerating senescence by altering carbohydrate and nitrogen dynamics[3]. Shifts in global precipitation patterns are also anticipated, with some regions subjected to greater flooding, and others to drought[2]. With unequal distribution of precipitation, supplemental irrigation of land crops with treated wastewater may be necessary in some regions of the world, increasing the risk of salinity stress and heavy metal accumulation in crops and soils[4−7]. Moreover, simultaneous exposure to multiple stresses may lead to cross-stress interactions, intensifying the severity of stress symptoms and complicating crop management.

Perennial grasses play an important role in alleviating environmental stress through their strong root systems, which possess the ability to capture and fix carbon, as well as their adaptability to different climates, and improve the health of ecosystems worldwide[8]. Plants undergo a variety of physiological and metabolic changes in response to abiotic stresses, including alterations in amino acid metabolism. Amino acids play a crucial role in regulating plant growth, development, and adaptation to environmental stresses by serving as the essential precursor of proteins and other metabolites, signaling molecules, and regulating osmotic balance. In response to abiotic stresses, amino acid profiles in plants change, with some going through catabolism to release nitrogen, and others accumulating, offering stress protection for plants to adapt to the adverse conditions[9,10]. This article provides an overview of current literature on the roles and regulatory mechanisms of amino acid metabolism in grass tolerance to abiotic stresses. It will discuss the use of amino acids as biostimulants through exogenous applications to enhance grass stress tolerance.

-

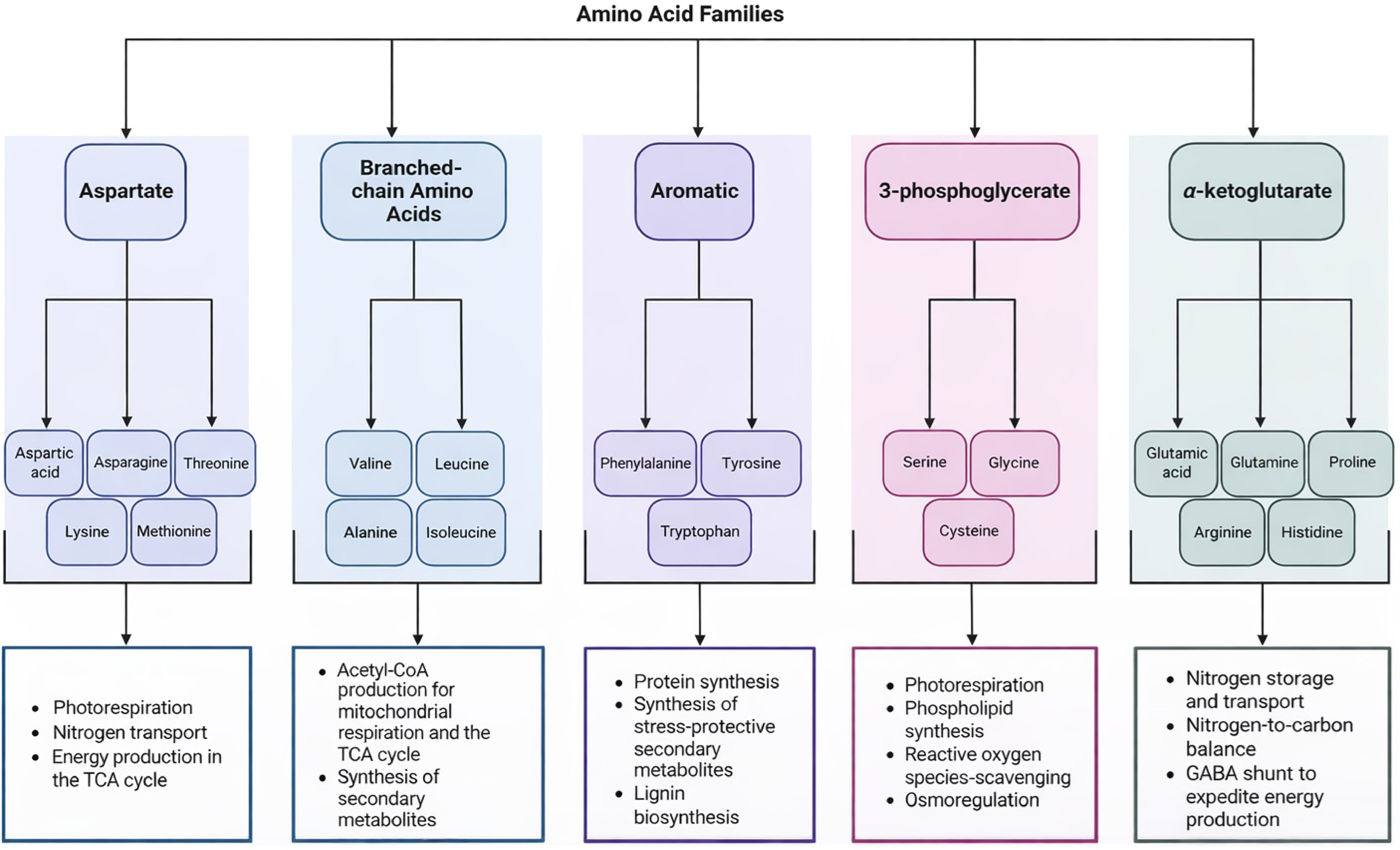

Amino acids are grouped into five distinct families [aspartate, branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), aromatic, 3-phosphoglycerate, and α-ketoglutarate] according to their biosynthetic pathways and metabolic functions (Fig. 1). Aspartate family amino acids, such as aspartic acid, asparagine, threonine, lysine, and methionine, are generated from oxaloacetate, an important intermediate of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for energy production in the respiration process[11]. Threonine, lysine, and methionine are biosynthetic precursors to asparagine, which regulates nitrogen transport[12,13]. All four aspartate families of amino acids were elevated in heat-tolerant bermudagrass hybrids (Cynodon transvaalensis × Cynodon dactylon) subjected to heat stress[14]. Aspartic acid and threonine accumulated in hard fescue (Festuca trachyphylla) exposed to heat stress[15]. In creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) and annual bluegrass (Poa annua) subjected to heat stress, endogenous levels of lysine were significantly upregulated, with a greater fold-change noted in annual bluegrass[16]. Asparagine content increased in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) under drought stress[17].

Figure 1.

Biological functions of amino acids in five families and metabolic pathways: (i) aspartate, (ii) branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), (iii) aromatic, (iv) 3-phosphoglycerate, and (v) α-ketoglutarate.

Branched-chain amino acids, including valine, leucine, alanine, and isoleucine, are derived from pyruvate through glycolysis and are important sources of acetyl-CoA, a critical component of mitochondrial respiration and the TCA cycle for energy generation[18−20]. Four BCAAs increased in response to heat stress in hard fescue, while valine and isoleucine were significantly elevated in thermal bentgrass (Agrostis scabra), likely contributing to improved energy metabolism[15,21]. In annual bluegrass, valine, leucine, and isoleucine were upregulated endogenously under heat stress[16]. Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan are aromatic family amino acids that are responsible for the synthesis of proteins and downstream secondary metabolites having stress-protective properties, such as auxin, salicylic acid, and melatonin[22−25]. All three amino acids were elevated in response to heat stress in hard fescue[15]. Additionally, tryptophan accumulated in maize (Zea mays), wheat (Triticum aestivum), and barley (H. vulgare) exposed to drought stress[26−29]. In creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass, tryptophan content increased, with a greater fold-change in annual bluegrass; however, phenylalanine and tyrosine were downregulated in creeping bentgrass, but upregulated in annual bluegrass[16], suggesting that differences may exist in amino acid metabolism among different species under stress.

Serine, glycine, and cysteine are all members of the 3-phosphoglycerate family. Serine is generated from the breakdown of glycerate, which is derived from 3-phosphoglycerate and functions in photorespiration, synthesizes phospholipids, and is converted into glycine and cysteine[30−34]. Glutathione, an important scavenger of free radicals, is formed from the degradation of glycine and cysteine, offering protection to plants under stress[35,36]. Additionally, glycine can be converted into glycine betaine, an amino acid with osmoregulant and osmotic stress-protective properties[37]. Of the amino acids in the 3-phosphoglycerate family, serine and glycine increased in drought-stressed barley, enhancing the rate of photorespiration to protect plants from reactive oxygen species (ROS) during stress-induced inhibition of photosynthesis[38,39].

The α-ketoglutarate family of amino acids comprises glutamic acid, glutamine, proline, arginine, and histidine. Glutamic acid is the nitrogen precursor of all amino acids through its involvement in the glutamine synthetase-glutamate synthase cycle, which mediates nitrogen to carbon balance in plants[40], and when this amino acid is decarboxylated into γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), energy production can be expedited through the GABA shunt[41−43]. Proline and GABA act together to support this pathway, as proline accumulates in the cytosol to be catabolized into Δ1-pyrroline and subsequently, GABA, allowing carbon to be fed into the GABA shunt to sustain the TCA cycle and energy production[41,43]. Proline was strongly upregulated in creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass subjected to heat stress, and histidine was solely upregulated in annual bluegrass[16]. Cumulatively, these findings underscore the central role of amino acids in stress physiology and highlight their potential as targets for enhancing plant resilience through means such as breeding or exogenous application.

-

Amino acid metabolism can be hindered by abiotic stresses, particularly in stress-sensitive plant species or cultivars, due to stress-mediated inhibition of the acquisition and assimilation of nitrogen into amino acids[44−46]. Amino acids are foundational to the critical biochemical and metabolic pathways in plants and have been widely studied for their beneficial, stress-alleviating effects; therefore, developing strategies for maintaining and enhancing amino acid accumulation in plants suffering from stress damage can be beneficial for strengthening stress defense. The following sections provide an in-depth discussion of the physiological and metabolic effects of exogenously applied amino acids on grasses under heat and drought stress, highlighting potential mechanisms of stress mitigation and symptom alleviation based on a comprehensive review of current literature.

Drought stress

-

Drought stress is attributed to a reduction in rainfall or irrigation, resulting in a decline in soil water availability to a level that is detrimental to the growth and development of plants. Drought stress has deleterious effects on a variety of physiological and metabolic processes, although exogenous application of amino acids has been found to improve drought tolerance by enhancing or allowing for the maintenance of plant water relations, carbohydrate metabolism (photosynthesis and carbohydrate synthesis), amino acid metabolism, and antioxidant metabolism (Table 1).

Table 1. Amino acids that improve grass water relations, photosynthesis, carbohydrate synthesis, amino acid metabolism, and antioxidant metabolism when exogenously applied under drought stress.

Amino acid applied Plant Property altered Ref. I. Water relations and osmotic adjustment Arginine Sugarcane (S. officinarum) Increased: Transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, carboxylation efficiency, CO2 assimilation [80] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: RWC [86] Betaine Barley (H. vulgare) Increased: Transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration [82] GABA Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Osmotic adjustment, RWC [61−66] Perennial ryegrass (L. perenne) Increased: RWC [67]

Glycine betaineMaize (Z. mays) Increased: Transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration [83] Rice (O. sativa) Increased: RWC [55] Sugarcane (S. officinarum) Increased: RWC, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, water use efficiency [53] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, CO2 assimilation, intercellular CO2 concentration, water use efficiency, RWC, osmotic potential, pressure potential, leaf water potential [47−52] Isoleucine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: RWC [69] Leucine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: RWC [69] Methionine Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: CO2 assimilation, intercellular CO2 concentration, stomatal conductance, water use efficiency [71] Proline Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Oleic and linoleic acid contents [78] Rice (O. sativa) Increased: RWC [69] Tryptophan Maize (Z. mays) Increased: RWC [70] Valine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: RWC [69] II. Photosynthesis Arginine Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Photochemical efficiency, photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll content [79] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, carotenoids [72] GABA Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Photochemical efficiency, photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll content [62−66] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Chlorophyll content [77] Glycine betaine Barley (H. vulgare) Increased: Chlorophyll content, photosynthetic rate [82] Carpet grass (A. compressus) Increased: Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, carotenoid content [85] Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Chlorophyll content [84] Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll a, b, total chlorophyll, carotenoids [83] Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Chlorophyll a, total chlorophyll, carotenoids, photosynthetic rate, photochemical efficiency, photon yield of photosystem II [55,76] Sugarcane (S. officinarum) Increased: Photosynthetic rate, carboxylation efficiency, photochemical efficiency, effective quantum yield of photosystem II

Decreased: Photoinhibition, relative excess energy in photosystem II[53] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Leaf area, chlorophyll content, photosynthetic rate [47,51] Methionine Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Chlorophyll and carotenoid content [71] Phenylalanine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Chlorophyll content [81] Proline Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Chlorophyll content [77] Tryptophan Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Chlorophyll content [70] III. Carbohydrate synthesis Arginine Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Soluble sugars [72] GABA Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Soluble carbohydrates, proteins involved in carbohydrate transport [62,64] Carpet grass (A. compressus) Increased: Soluble sugars [85] Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Soluble sugars [75] Rice (O. sativa) Increased: α-amylase activity, total soluble sugars [55,74] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Soluble sugars, endogenous proline [51] Methionine Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Total soluble proteins [71] Proline Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Sugar content (seed) [78] IV. Amino acid metabolism Alanine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Total endogenous amino acids [69] Arginine Sugarcane (S. officinarum) Increased: Endogenous arginine and glutamate content [80] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Free amino acids, endogenous proline [72] GABA Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Endogenous GABA content [65,66] Glycine betaine Carpet grass (A. compressus) Increased: Endogenous proline content [85] Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Endogenous proline content, soluble proline, endogenous glycine betaine content [54,75] Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Endogenous glycine betaine and proline content [55,74,76] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Endogenous proline content [49] Isoleucine, leucine, proline, valine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Total endogenous amino acids [69] V. Antioxidant metabolism Arginine Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT, GST, GR, APX)

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2, O2•−)[79] Sugarcane (S. officinarum) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT) [80] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (CAT, glutathione S-transferase, GPX); Non-enzymatic antioxidants (ascorbate, glutathione) (increased) [86] GABA Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT, GR, MDAR, DHAR)

Decreased: Electrolyte leakage, oxidative species (H2O2, O2•−)[62,63,65,66] Perennial ryegrass (L. perenne) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (POD

Decreased: MDA content, electrolyte leakage[67] Triticale (x Triticosecale) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT)

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2, O2•−)[87] Glycine betaine Barley (H. vulgare) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT, APX) [82] Carpet grass (A. compressus) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT, APX), membrane stability index

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2), electrolyte leakage[85] Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT)

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (O2•−)[84] Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT, APX)

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2)[55] Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT), membrane stability index

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2), electrolyte leakage[47,51] Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidant (POD) [54] Methionine Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT)

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2)[71] Phenylalanine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD) [81] Proline Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidant (DPPH)

Non-enzymatic antioxidants (carotenoids, flavonoids, tocopherols)[78] Tryptophan Maize (Z. mays) Increased: Membrane stability index [70] Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD) [81] Tyrosine Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD) [81] Water relations and osmotic adjustment: Exogenous application of amino acids plays a vital role in improving plant water relations and osmotic adjustment under drought stress by enhancing relative water content (RWC), regulating osmolyte accumulation, and stabilizing cellular structures. Treatments with amino acids such as arginine, glycine betaine, proline, methionine, and GABA have been shown to increase leaf RWC and water potential, reduce cell membrane damage, and improve water-use efficiency in several Poaceae species, including wheat, maize, rice (Oryza sativa), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), creeping bentgrass, and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne).

Among these, glycine betaine is one of the most widely studied amino acid treatments for grasses subjected to drought stress. In drought-stressed wheat, exogenous glycine betaine elevated RWC, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, water potential, CO2 assimilation rate, and intercellular CO2[47−52]. Similar responses were observed in sugarcane foliar-treated with glycine betaine, which maintained higher RWC, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, and water use efficiency than untreated controls under drought[53]. In maize, foliar application of glycine betaine promoted endogenous proline and soluble sugar accumulation and enhanced enzymatic antioxidant defense, thereby improving RWC and osmotic balance[54]. In drought-subjected rice, glycine betaine improved RWC, osmotic potential, and pressure potential[55].

Under drought stress, plants sequester ions in the vacuole to avoid cytosolic enzyme inhibition and instead accumulate compatible solutes, such as glycine betaine, GABA, and proline, in the cytoplasm to equilibrate cellular osmotic balance[56]. GABA is known to accumulate under drought stress and restricts transpirational water loss through its signaling cascade on aluminum-activated malate transporters, which regulate stomatal aperture[57,58]. Additionally, GABA is known for its stress-mitigating effects on grass species when applied exogenously[59]. Under osmotic stress, proline improves water status by protecting the structure of proteins, enzymes, and membranes through activation of antioxidant metabolism[60]. Accordingly, treating grasses with compatible solutes is effective for enhancing drought tolerance. Exogenous treatment of creeping bentgrass with proline or GABA improved osmotic regulation, contributing to higher RWC under drought stress[61−66], while perennial ryegrass treated with GABA also maintained higher RWC than untreated controls[67]. Additionally, foliar application of glutamate to creeping bentgrass enhances the endogenous synthesis of this amino acid into downstream amino acids, such as proline and GABA, which may facilitate osmotic regulation and drought tolerance[68].

In addition to the osmolytes mentioned, other amino acids contribute to water relations under drought stress. Shim et al.[69] determined that applying BCAAs, such as leucine, isoleucine, and valine, alleviated drought stress by enhancing RWC in rice seedlings. In maize, tryptophan improved RWC under drought stress[70], while in wheat, methionine increased CO2 assimilation, intercellular CO2 concentration, stomatal conductance, and water use efficiency[71]. Collectively, these findings suggest that exogenous amino acids mitigate drought-induced dehydration, primarily by facilitating osmotic adjustment and protecting membrane integrity, thereby sustaining hydration and promoting growth under water-limited conditions.

Amino acid metabolism: When applied exogenously, certain amino acids confer drought tolerance by stimulating endogenous amino acid metabolism and expanding free amino acid pools essential for stress adaptation. Exogenous proline enhances its own endogenous levels, as well as GABA, under drought stress, both of which are directly involved in amino acid biosynthesis[61]. Similarly, GABA treatment induces its own endogenous production during drought, promoting tolerance[65,66]. Proline and GABA act cohesively to sustain the TCA cycle, as proline is gradually converted into Δ1-pyrroline and then degraded into GABA, which accelerates TCA cycle activity through the GABA shunt[41,43]. Through this pathway, proline can also be converted into glutamate, a key precursor of other amino acids; therefore, exogenous application of proline may elevate overall free amino acid content by driving the GABA shunt under drought stress. Arginine, another α-ketoglutarate family member, was used as a priming agent in maize, which exhibited higher levels of free amino acids and endogenous proline under drought[72].

Betaine is a methyl group donor in the methionine-homocysteine cycle, which converts homocysteine into methionine, an amino acid critical for protein synthesis[73]. Exogenous glycine betaine application has been shown to alleviate drought stress in wheat, rice, and carpet grass (Axonopus compressus) by increasing endogenous proline and soluble sugar content[51,74,75]. Foliar-applied glycine betaine improves drought tolerance in multiple Poaceae species, including rice, wheat, and maize, mainly by increasing endogenous proline content[49,55,74−76]. Additionally, glycine betaine treatment increases its own accumulation in drought-stressed rice and maize[55,75].

Beyond the well-established roles of the α-ketoglutarate family and glycine betaine, other amino acids have been implicated in the drought tolerance of grass species. Treating rice seedlings with BCAAs (leucine, isoleucine, valine, and alanine) increased total endogenous amino acid content under drought stress, suggesting their role in nitrogen homeostasis[69]. Exogenous methionine application increased total soluble protein content in wheat under drought stress, consistent with its function in protein synthesis[71]. Together with the α-ketoglutarate amino acids, these findings highlight that exogenous application of amino acids from diverse families may support drought tolerance by stimulating key biosynthetic pathways involved in nitrogen homeostasis, such as the GABA shunt, methionine-homocysteine cycle, and secondary metabolite production, thus increasing the pool of free amino acids critical for stress adaptation, protein synthesis, and cellular homeostasis.

Photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism: Exogenous application of amino acids can enable plants to maintain carbon metabolism under drought stress and promote drought tolerance by regulating the processes associated with photosynthesis and respiration. Treating drought-stressed wheat with GABA or proline promoted drought tolerance by allowing plants to maintain higher chlorophyll content[77]. Similarly, in creeping bentgrass, exogenous GABA enhanced photosynthetic rate, photochemical efficiency, and chlorophyll content, while up-regulating soluble carbohydrates and proteins involved in carbohydrate transport[62−66]. In drought-stressed maize, proline application increased seed sugar content, while tryptophan enhanced chlorophyll content[70,78]. Priming grains of maize with arginine improved the content of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids and elevated endogenous soluble sugars under drought stress[72]. Similarly, Sun et al.[79] determined that applying arginine to drought-stressed maize increased chlorophyll content, which promoted photosynthetic rate and photochemical efficiency. Arginine application increased endogenous arginine and glutamate levels in drought-stressed sugarcane[80], and phenylalanine elevated chlorophyll content in drought-stressed rice[81]. Treating wheat with methionine promoted chlorophyll and carotenoid content under drought stress[71].

Glycine betaine has also been reported to enhance photosynthetic performance under drought stress in several Poaceae species. Applying glycine betaine to barley (Hordeum vulgare) exposed to drought stress promoted drought tolerance by elevating chlorophyll content, photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, and transpiration[82]. In maize, it elevated chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, carotenoids, photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, and soluble sugar content[75,83]. In creeping bentgrass, glycine betaine increased chlorophyll content[84], while in carpet grass, it promoted chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoid accumulation[85]. In wheat, glycine betaine enhanced leaf area, chlorophyll content, and photosynthetic rate, while in rice, it increased chlorophyll a, total chlorophyll, carotenoids, photosynthetic rate, photochemical efficiency, and photon yield of photosystem II[47,51,55,76]. Additionally, glycine betaine enhanced α-amylase activity and soluble sugar content in rice[55]. In sugarcane, glycine betaine treatment improved photosynthetic rate, carboxylation efficiency, photochemical efficiency, effective quantum yield of photosystem II, and reduced photoinhibition and relative excess energy in photosystem II during drought[53]. These studies suggest that many amino acids improve drought tolerance in grass species by enhancing chlorophyll content, photosynthetic capacity, and carbohydrate metabolism, and contribute strongly to the maintenance of photosynthesis and carbohydrate accumulation during drought stress.

Antioxidant metabolism: Various studies have exhibited that applying individual amino acids improves drought tolerance by inducing enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant metabolism to reduce oxidative stress and support membrane stability. In wheat, arginine treatment promoted the activity of ascorbate, glutathione, catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) under drought stress[86]. Application of proline to drought-stressed maize increased the activity of diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) as well as the content of carotenoid, flavonoid, and tocopherol, contributing to enhanced antioxidant defense[78]. Arginine also improved drought tolerance in maize by enhancing the activity of SOD, peroxidase (POD), CAT, GST, glutathione reductase (GR), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), while decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide anion (O2•−), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)[79].

Applying GABA to triticale (x Triticosecale) under drought stress enhanced SOD and CAT activity and reduced O2•−, H2O2, and MDA[87]. Similarly, GABA-treated creeping bentgrass exhibited increased activity of SOD, POD, CAT, GR, monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDAR), and dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), along with decreased electrolyte leakage and lower levels of ROS, indicating improved membrane stability[62,63,65,66]. In perennial ryegrass, GABA promoted POD activity, while electrolyte leakage and MDA content were suppressed[67].

Glycine betaine has been shown to enhance antioxidant defense in multiple Poaceae species under drought stress. In creeping bentgrass, glycine betaine elevated SOD, POD, and CAT activity, which reduced membrane damage by lowering MDA and O2•− content under drought[84]. In carpet grass, which exhibited elevated SOD, CAT, POD, and APX activity, as well as reduced MDA and H2O2 content[85]. Lipid peroxidation was ameliorated in wheat and rice exposed to drought stress following glycine betaine treatment, which suppressed MDA and H2O2 content[48,49,51,55]. As a seed-priming or foliar treatment, glycine betaine reduced electrolyte leakage and increased membrane stability index in drought-stressed wheat, while simultaneously increasing the activity of SOD, POD, and CAT[48,49]. In rice, glycine betaine also enhanced the activity of SOD, CAT, and APX under drought stress[55]. Treating drought-stressed barley with glycine betaine elevated the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), CAT, and APX[82].

Methionine application in wheat increased the activity of enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, and CAT) under drought, while reducing MDA and H2O2 content[71]. Aromatic amino acids, such as tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine, are involved in protein synthesis to produce secondary metabolites important for stress defense[25]. In rice, these amino acids increased SOD activity during drought stress[81], and tryptophan treatment in maize enhanced the membrane stability index[70]. Together, these studies demonstrate that exogenous amino acids, especially glycine betaine, as well as those in the α-ketoglutarate (arginine, proline, and GABA), aspartate (methionine), and aromatic (tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine) families, strengthen drought tolerance in Poaceae species by enhancing enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems, reducing ROS and lipid peroxidation, and maintaining membrane integrity under drought conditions.

Heat stress

-

Heat stress restricts plant growth and development by interrupting various physiological and metabolic processes, including photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism, and amino acid and protein metabolism, as well as the induction of oxidative stress[88−90]. It has been determined that treating various plants with amino acids may encourage heat tolerance by enhancing photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism, improving osmotic adjustment, promoting amino acid metabolism and the retention of proteins, and elevating antioxidant response and preventing lipid peroxidation (Table 2).

Table 2. Exogenous amino acids that improve grass photosynthesis, carbohydrate metabolism, osmotic adjustment, amino acid metabolism and protein retention, and antioxidant metabolism under heat stress.

Amino acid applied Plant Property altered Ref. I. Photosynthesis Aspartic acid Perennial ryegrass (L. perenne) Increased: Chlorophyll content [96] GABA Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Chlorophyll content, photochemical efficiency [92] Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Photochemical efficiency, photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll content [62,63,93−95] Proline Barley (H. vulgare) Increased: Photochemical efficiency [91] II. Carbohydrate metabolism Aspartic acid Perennial ryegrass (L. perenne) Increased: Sugars (Glucose-6-phosphate, glucose, UDP-glucose, glucuronic acid, sucrose, sorbitol); organic acids (pyruvate, oxaloacetate, citrate, malate, α-ketoglutarate, succinate, shikimate) [96] GABA Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Sugars (trehalose) [92] Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Soluble carbohydrates, organic acids (aconitate, malate, succinate, oxalic acid, threonic acid); soluble sugars (sucrose, fructose, glucose, galactose, maltose) [62,95] III. Osmotic adjustment GABA Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Stomatal conductance, RWC [92] Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Osmotic adjustment, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, RWC, water use efficiency [62,63,93−95] IV. Amino acid metabolism and protein retention Aspartic acid Perennial ryegrass (L. perenne) Increased: Amino acid content [96] Arginine Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Amino acid content, protein synthesis [97,98] GABA Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Endogenous GABA content, endogenous proline content [62,63,94] Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Amino acid content [95] V. Antioxidant metabolism Aspartic acid Perennial ryegrass (L. perenne) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT, POD, APX)

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2, O2•−), electrolyte leakage[96] Arginine Wheat (T. aestivum) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT)

Decreased: MDA content[98] GABA Rice (O. sativa) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT, APX, GR); Non-enzymatic antioxidants (Ascorbate, glutathione)

Decreased: MDA content, oxidative species (H2O2)[92] Creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera) Increased: Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, POD, CAT, APX, DHAR, GR); Non-enzymatic antioxidants (ascorbate, DHA, glutathione, oxidized glutathione)

Decreased: Electrolyte leakage, MDA content, carbonyl content, oxidative species (H2O2, O2•−)[62,63,93−95] Photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism: Exogenous proline applied to barley under heat stress enhanced photochemical efficiency[91]. In rice treated with GABA, chlorophyll content and photochemical efficiency were both elevated under heat stress, while the content of trehalose also increased[92]. Furthermore, stomatal conductance and RWC were elevated. Similarly, in creeping bentgrass, GABA application enhanced photosynthetic rate, photochemical efficiency, chlorophyll content, and osmotic adjustment, while also elevating RWC and water use efficiency compared with untreated plants[62,63,93,94]. GABA also stimulated the accumulation of soluble sugars (sucrose, fructose, glucose, galactose, maltose) and organic acids (aconitate, malate, succinate, oxalic acid, threonic acid), supporting energy metabolism under heat stress[62,63,93–95]. Additionally, GABA-treated creeping bentgrass exhibited higher transpiration rate and stomatal conductance, suggesting a role in leaf cooling under heat stress[94,95]. Perennial ryegrass treated with aspartic acid had significantly higher leaf chlorophyll content, sugars (glucose-6-phosphate, glucose, UDP-glucose, glucuronic acid, sucrose, sorbitol), and organic acids (pyruvate, oxaloacetate, citrate, malate, alpha-ketoglutarate, succinate, shikimate) under heat stress, suggesting protection of light-harvesting organs and energy production[96].

Amino acid and protein metabolism: Protein degradation is one important aspect occurring during leaf senescence that is accelerated by heat stress, and control of this process alleviates the loss of critical stress-protective proteins and increases amino acid reserves. Wheat treated with arginine under heat stress exhibited enhanced amino acid content and protein synthesis, suggesting greater retention of proteins[97,98]. In creeping bentgrass, GABA has been determined to enhance endogenous levels of proline and GABA and promote free amino acid accumulation under heat stress[62,93−95]. Similarly, aspartic acid treatment elevated endogenous amino acid levels in perennial ryegrass[96]. Together, these findings suggest that amino acids facilitate heat tolerance by mitigating protein degradation.

Antioxidant metabolism: There is a plethora of evidence showing that amino acids alleviate heat stress by improving antioxidant metabolism when exogenously applied. Application of arginine to wheat subjected to heat stress increased the activity of SOD and CAT, while decreasing lipid peroxidation, as indicated by reduced MDA content[98]. Treating rice with GABA increased activities of the enzymatic antioxidants, SOD, CAT, APX, and GR, in addition to the non-enzymatic antioxidants, ascorbate and glutathione, while simultaneously reducing MDA and H2O2 content[92]. Similar effects were observed in creeping bentgrass, where GABA enhanced the activities of SOD, POD, CAT, APX, DHAR, and GR, as well as the non-enzymatic antioxidants ascorbate, dehydroascorbic acid, glutathione, and oxidized glutathione. This was accompanied by reductions in electrolyte leakage, MDA, protein carbonyls, and oxidative species, including H2O2 and O2•−[63,93−95]. In perennial ryegrass, aspartic acid also enhanced the activity of enzymatic antioxidants, such as SOD, CAT, POD, and APX, and reduced electrolyte leakage and membrane peroxidation, as indicated by lower levels of MDA and oxidative species (H2O2, O2•−)[96]. The results of these studies together suggest that exogenously applying amino acids to grass alleviates oxidative stress and prevents cellular damage under heat stress.

-

Important advancements have been made toward comprehending how exogenously applied amino acids contribute to plant stress tolerance, particularly drought and heat. While it has long been understood that the endogenous accumulation of various amino acids confers stress tolerance, recent efforts have elucidated that supplying plants with these nitrogen-rich molecules externally can alter their physiological and metabolic responses to stress. The insight provided by this literature suggests that exogenous treatment of grass species with amino acids, primarily with proline, GABA, and glycine betaine, can improve drought or heat tolerance through several mechanisms: (1) enhancing water relations and osmotic adjustment, (2) sustaining photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism, (3) stimulating amino acid and protein metabolism, and (4) activating antioxidant defense systems to mitigate oxidative damage. Across studies, interspecific variation in amino acid responses to drought and heat stress is relatively common; however, the mechanisms underlying these differences remain largely unexplained and will require future work integrating physiological and molecular approaches across species. Additionally, the molecular and genomic pathways for amino acid-mediated regulation of abiotic stresses have not been as widely studied as some of the metabolic mechanisms. Therefore, this review may offer the informed context necessary for pursuing such research avenues. In the future, it will be necessary to study how other amino acids in a variety of pathways might ameliorate abiotic stresses, as well as how amino acids can be implemented into grass management as preventative and remedial treatments. Furthermore, efforts in the future should explicitly evaluate post-stress recovery in amino acid-treated grasses by monitoring parameters such as regrowth, tillering, root recovery, and changes in metabolites. Such work may allow for the development and optimization of novel amino acid-based health products aimed at promoting rehabilitation following abiotic stress-induced damage and could improve stress tolerance in grasses under increasingly variable climates.

No external funding was received for the preparation of this review. The authors have no acknowledgements to declare.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Rossi S, Huang B; literature collection: Rossi S, Huang B; draft manuscript preparation: Rossi S; manuscript revision: Huang B; supervision: Huang B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing does not apply to this review article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Rossi S, Huang B. 2025. Regulatory mechanisms of amino acids for improving plant tolerance to drought and heat stress – a review. Grass Research 5: e033 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0035

Regulatory mechanisms of amino acids for improving plant tolerance to drought and heat stress – a review

- Received: 26 August 2025

- Revised: 25 November 2025

- Accepted: 28 November 2025

- Published online: 24 December 2025

Abstract: Plants are increasingly facing the ecological impacts of climate change, including drought and heat stress, which pose significant threats to plant growth and productivity. Amino acid metabolism plays a crucial role in plant tolerance to these stresses. This review highlights the regulatory functions of amino acids in enhancing stress tolerance when applied externally, focusing on drought and heat stress in grass species used as annual crops, forage, or turfgrass. It identifies specific amino acids that are most effective in enhancing drought and heat stress tolerance and discusses the key physiological responses of plants under each stress condition, along with the specific mechanisms by which amino acids influence stress signaling, metabolism, and protective pathways. The findings presented in this review may contribute to the future development of stress-tolerant grass varieties, as well as innovative biostimulants with amino acids as ingredients to mitigate the damage caused by heat and drought stress. Although this review primarily focuses on the metabolic mechanisms regulating these stresses in grasses, the current insights may provide a conceptual framework to guide future molecular and genomic research aiming to improve heat and drought tolerance in grasses. Additionally, understanding how amino acids can be incorporated into grass management practices is important. Future research focused on how amino acid-treated plants recover from prolonged or severe heat and drought stress could lead to the development of novel products aimed at promoting rehabilitation after stress-induced damage.