-

Despite the rapid change in media use, book reading, a relatively traditional media use, is still prevalent and prominent in our modern lives, especially for adolescents. According to a nationwide survey in China in 2021, the book reading rate among adolescents reached over 90% and is the highest among all age groups[1]. Reading books has a life-long impact on people[2]. Therefore, such a high book reading rate among adolescents suggests that research on the influence of book reading on this group is warranted. Studies have shown that book reading is predominantly beneficial for adolescents and young adults at the intrapersonal level, such as developing their vocabulary[3], improving their academic performance[4], and increasing their media literacy[5]. However, the potential influence of book reading on the interpersonal and social aspects of adolescents has not been fully explored.

One of the most prominent concerns in the interpersonal and social development of adolescents is prosocial behavior. Prosocial behavior is an important category of human behavior operated at interpersonal and societal levels, which in general refers to 'behaviors that benefit other people, such as helping, sharing, donating and volunteering[6]. For adolescents, performing prosocial behavior is a hallmark of their social competence[7] and benefits them in various aspects, such as improving their friendship quality[8], well-being[9] and academic performance[10]. Therefore, in past decades, scholars from various fields have explored the different factors stimulating prosocial behavior to better nurture such behavior, among which media use is one of the essential factors[11].

Although research has tested prosocial outcomes induced by the usage of several types of media, including television[12], music[13,14], and video games,[15,16] much less attention has been paid to books, a traditional media yet still prevalent and prominent in our modern lives. In today's digital era, heightened worries about excessive screen time and its potential impact on health and well-being have sparked a keen interest in pursuits such as book reading, which offer a refreshing alternative[17,18]. Furthermore, the significance of reading books holds a pivotal role in the realm of education[19]. Among the limited published literature on book reading and prosocial outcomes, most of them basically followed the traditional research approach adopted by media study scholars, which focuses on readers' exposure to specific prosocial content[20] or specific genre[21,22]. These studies lay down a good foundation for understanding how book reading is associated with prosocial behavior. Nevertheless, specifying the content of the books lacks ecological and external validity because the books that people read in daily life contain various genres of books.

In the current study, we argue that more general book reading that does not specify the type of content could also predict adolescents' prosocial behavior from the perspective of media affordance. The affordance of print media (e.g., books and newspapers) reduce distractions and enable its readers to take more time to browse and think, facilitating the apprehension process[18,23]. Furthermore, unlike other text in other media forms like social media posts, newspapers, or magazines, the content in books is much longer in length and deeper in content[24,25]. Consequently, reading books involves a higher cognitive load and can better enhance cognitive development and literacy than other media types[25,26]. Adolescents are in the stage of rapid cognitive development[27]. As such, the effect of reading books on cognitive abilities could be more prominent in this group.

At the same time, due to the strict gatekeeping in terms of book publication in almost all countries and areas[28], books generally contain more content concerning positive social norms about prosocial behavior compared to other media. This is especially true in China since the Chinese government particularly emphasizes the educational duty of books, aiming at improving people's morality and prosociality via book reading[29]. Moreover, given the augmentation function of cognitive abilities through reading books, readers thereby could be more capable of learning and understanding social norms conveyed in books. Also, social norms can be internalized into personal norms, which is an essential antecedent of prosocial behavior[30]. Taken together, we argue that general book reading can improve adolescents' cognitive abilities that drive the effect of book reading on prosocial behavior via the mediating roles of social norms and personal norms.

Based on these arguments, we conducted two studies with different emphases. Study 1 seeks to identify the association between adolescents' book reading and their prosocial behavior with nationally representative data. Study 2 then collects survey data with more comprehensive measures to further validate the finding of Study 1 and explores the underlying mechanisms. Specifically, we develop a model through the normative influence's perspective, examining social norms and personal norms as two serial mediators in the relationship between adolescents' book reading and prosocial behavior. Theoretically, these two studies go beyond the focus on exposure to specific reading content or genres to explore the impact of general book reading on individuals' prosocial behavior, which enriches the current literature on the prosocial outcomes of media use. Practically, our findings are valuable references for practitioners in the book publishing industry and generate beneficial insights for adolescents' prosocial education.

-

To explore whether general book reading has an impact on prosocial behavior among adolescents, we resorted to China Education Panel Survey (CEPS), a nationally representative panel data in China. Because the data is publicly available, the ethical review was exempted by the Institutional Review Board of the corresponding author's institute. In the 2013−2014 academic year, CEPS surveyed 19,487 students (10,279 seventh-grade students and 9,208 ninth-grade students) from 112 schools in 28 county-level areas in China. This study used the data of seventh-grade students, among which 9,449 completed the follow-up survey during 2014−2015 academic year. CEPS not only included the survey of students themselves, but their important others such as parents. Among all the participants, 47.02% were females, and 52.80% were males. The age range of the participants was 11 to 18 (M = 12.967, SD = 0.894).

Measurements

-

The dependent variable is prosocial behavior. The measurement of this variable was from the follow-up survey by asking the students the frequency of three prosocial behaviors during the past year. The three prosocial behaviors were (1) helping the elders, (2) being kind and friendly to others, and (3) following rules and not cutting in lines (1 = never, 5 = always; M = 3.789, SD = 0.771, Cronbach's α = 0.680). Our selection of the three behaviors was primarily guided by the prosocial scale for Chinese adolescents formulated by Yang et al. taking into consideration the cultural nuances of prosocial behavior[31]. It is important to acknowledge that, given the secondary analysis nature of Study 1, the three items stood as our sole available options. To check the robustness of the results, the parental report of prosocial behavior in the follow-up survey was chosen as an alternative measure. The parents were asked to rate the frequency of the same three prosocial behaviors of their children in the past year (1 = never, 5 = always; M = 3.694, SD = 0.786, Cronbach's α = 0.717).

The independent variable in this study is book reading. It was measured by the average hours the student spent last week reading books (M = 35.097, SD = 37.557). Control variables included two other media use variables (i.e., television and video games), demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, rural hukou, migration, residence in school, parents' education, ethnicity, and single child), cognitive ability variables (i.e., ranking in class, cognitive ability test by CEPS, math test scores, Chinese test scores, and English test scores), family relationship variables (i.e., educational expectations of parents, relationship quality between father and mother, relationship quality with mother, and relationship quality with father), teacher-related variables (i.e., teachers' criticism, teachers' responsibility, teachers' patience, the likability of the student advisor, the likability of other teachers), and peers' relationship variables (i.e., friendliness of classmates, closeness with others in school, and likability of classmates). Class fixed effects were also controlled.

To further validate the results of Model 1 and 2, we used self-reported and parental reported antisocial behaviors measured in the follow-up survey as dependent variables to examine their relationship with book reading. Such a comparison enables us to check the robustness of the impact of book reading on adolescents' prosocial development. Antisocial behavior was indicated by averaging the frequency of the student's five antisocial behaviors in the past year. The five behaviors were (1) insulting others and talking dirty, (2) quarreling, (3) fighting, (4) bullying classmates, and (5) cheating on homework and exams (1 = never, 5 = always; self-reported: M = 1.609, SD = 0.565, Cronbach's α = 0.762; parental reported: M = 1.366, SD = 0.439, Cronbach's α = 0.747).

Results

-

We used Stata 17 to estimate the OLS models. Table 1 presents the detailed results of the four regression models. Book reading was found to be positively related to both self-reported and parent-reported prosocial behavior (self-reported: B = 0.011, p <0.001; parental reported: B = 0.006, p = 0.009). Therefore, the relationship between book reading and adolescents' prosocial behavior is supported. The relationship is consistent across the combinations of different measures, suggesting such a relationship is not sensitive to measurement. Moreover, the results of Models 3 and 4 revealed that book reading negatively predicts antisocial behavior (self-reported: B = −0.007, p < 0.001; parental reported: B = −0.004, p = 0.002).

Table 1. Regression results of study 1.

Variables Prosocial behavior Antisocial behavior Self-reported Parental reported Self-reported Parental reported Book reading 0.011*** 0.006** −0.007*** −0.004** (0.002) (0.002) (0.002) (0.001) Media use variables Watching TV −0.008*** −0.007** 0.005*** 0.004*** (0.002) (0.002) (0.001) (0.001) Playing games −0.005** −0.004ϯ 0.014*** 0.006*** (0.002) (0.002) (0.001) (0.001) Demographic variables Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled Cognitive ability Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled Family relationship variables Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled Teachers related variables Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled Peers' relationship variables Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled Class fixed effect Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled Constant 2.668*** 2.309*** 1.955*** 1.726*** (0.224) (0.236) (0.162) (0.128) Observations 7,487 7,349 7,491 7,361 R2 0.188 0.163 0.212 0.192 Adj. R2 0.160 0.134 0.185 0.164 F 20.61 17.61 25.96 21.50 Standard errors in parentheses. ϯ p < 0.1, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. For the clarity of the table, the coefficients of each type of control variable were not listed in detail. More interestingly, the results showed that watching TV is negatively related to prosocial behavior while positively related to antisocial behavior (self-reported prosocial behavior: B = −0.008, p < 0.001; parental reported prosocial behavior: B = −0.007, p = 0.001; self-reported antisocial behavior: B = 0.005, p < 0.001; parental reported antisocial behavior: B = 0.004, p < 0.001). In addition, playing games is negatively related to prosocial behavior (self-reported: B = −0.0005, p < 0.001; parental reported: B = −0.004, p < 0.01) and positively associated with antisocial behavior (self-reported: B = 0.014, p < 0.001; parental reported: B = 0.006, p < 0.001).

Discussion

-

Based on the analysis of a nationally representative data set, this study confirmed that book reading positively predicted adolescents' prosocial behavior and supported the robustness of such a relationship. The negative relationship between book reading and antisocial behaviors provided additional evidence that book reading is beneficial for adolescents' prosocial development. However, due to the constraints of secondary analysis, this study failed to explore the potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between book reading and adolescents' prosocial behavior. Therefore, we designed a new survey attempting to address this question.

-

This study is based on a survey conducted in an East China city in 2021. The corresponding author's Institutional Review Board (No. H2021177I) approved the protocol. We adapted established scales to develop the questionnaire, which was evaluated by three experienced secondary school teachers for the understandability of adolescents. We then performed a pretest with a convenience sample of 103 adolescents to test all the instruments' reliability and validity. We also modified the questionnaire based on the feedback of the pretest, such as deletion of some items and improvement of the wording.

We conducted the formal paper-based survey in one junior secondary school and one senior secondary school. Participants were randomly selected from each grade at each school to ensure the distribution of our participants covered all six grades. The number of participants from each grade was approximately one hundred. The initial sample size is 647. We then dropped participants whose responses were over 50% empty or straight-line (i.e., participants who responded to all the 5-point Likert scale with almost the same answer). One participant who indicated age as 100 years old was also removed. Finally, 631 participants were kept (49.18% females and 50.82% males, aged from 12 to 19; Mage = 15.211, SDage = 1.600) and we imput the missing data with the expectation-maximization algorithm for data analysis.

Measurements

Book reading

-

Book reading was measured by book reading habits in this study. This measurement is adapted from the measures of social media use by Ellison et al.[32]. Participants were asked to rate their agreement (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree) on the following four statements: (1) 'I often read books in my free time,' (2) 'Reading books in free time is my habit,' (3) 'I've been reading books for years,' (4) 'I feel bad if I don't read books,' and a reading frequency question 'Generally speaking, how frequently do you read books?' (1 = never, 5 = always). The five items were all measured with 5-point Likert scales, and they were averaged for data analysis (M = 3.115, SD = 0.920, Cronbach's α = 0.859).

Social norms

-

The social norms measure contained three items, which were adapted from the work of Ajzen[33] and Smith & McSweeney[34]. Respondents rated the extent to which they agree or disagree on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) with the following statements: 'The majority of people today still have basic moral values,' 'The majority of people will not hesitate to lend a helping hand to people in need,' and 'The majority of people believe that they should treat others the way they would like to be treated.' The scale had a acceptable reliability of α = 0.742 (M = 3.636, SD = 0.855).

Personal norms

-

To measure personal norms, we used the scale modified from scales developed by Smith & McSweeney[34]. Respondents were asked to rate on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) the extent to which they agree with three items (M = 3.454, SD = 0.920, Cronbach's α = 0.899). The items included: 'I feel morally obliged to help people in need,' 'I feel guilty when I do not help people in need,' and 'It is my duty to help people in need.'

Prosocial behavior

-

Based on the study of Carlo & Randall[35], Yang et al.[31] developed the Chinese version of the prosocial behavior scale incorporating features of Chinese adolescents. It has been validated and extensively used in measuring adolescents' prosocial behavior in China. The scale contains 15 items. Each item describes a kind of prosocial behavior. Sample items included 'I voluntarily give seats to those in need, such as the elderly, the weak, the sick, the disabled, and the pregnant,' and 'When a classmate is sick, I take him to see the school nurse.' Participants were asked to rate the extent to which the item is in line with their condition (1 = Not at all, 5 = Completely; M = 3.647, SD = 0.785, Cronbach's α = 0.909).

Results

-

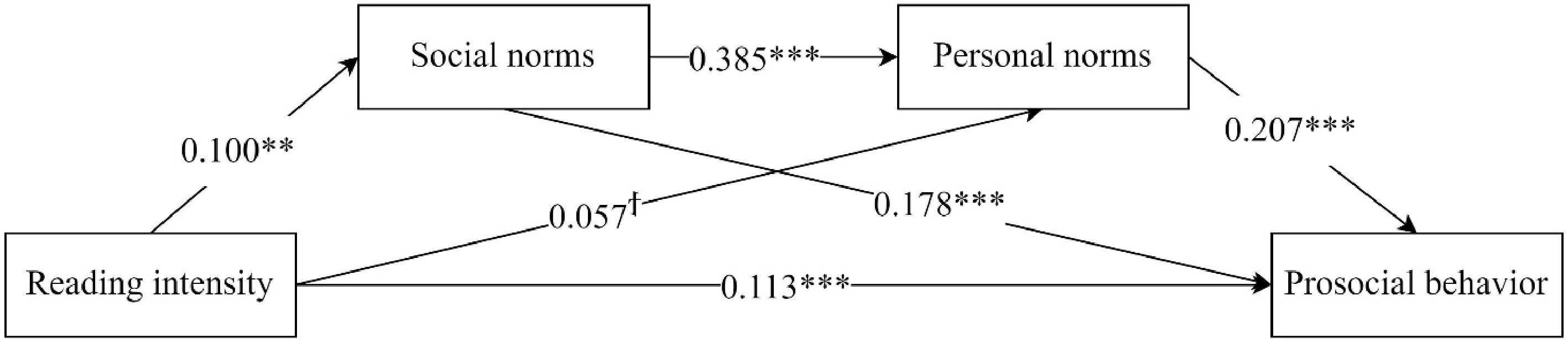

Table 2 presents the correlation metrics of variables included in the model. To explore whether social norms and personal norms function as potential mediators linking book reading and adolescents' prosocial behavior, we conducted a serial mediation analysis with PROCESS Model 6 for SPSS[36], in which book reading was entered as the independent variable, prosocial behavior as the dependent variable, social norms as the stage-one mediator, and personal norms as the stage-two mediator. Meanwhile, five variables (e.g., gender, age, parent's education, income, and empathy) were entered into the model as covariates. Table 3 presents the regression results. where social norms, personal norms, and prosocial behaviors were examined as dependent variables, respectively. We examined the indirect effects with biased-corrected confidence interval recommended by Preacher & Hayes[37] (See Table 4). If a confidence interval for the indirect effect does not straddle zero, this can statistically support that M mediates the effect of X on Y[38].

Table 2. The correlation metrics of variables.

M SD PB SN PN RI PB 3.647 0.785 1.000 SN 3.636 0.855 0.500 1.000 PN 3.454 0.899 0.587 0.545 1.000 RI 3.115 0.920 0.260 0.167 0.184 1.000 Note: The p values of all the correlation coefficients < 0.001. PB = prosocial behavior, SN = social norms, PN = personal norms, RI = reading intensity. Table 3. Regression results of study 2.

Dependent variable Social norms Personal norms Prosocial behavior B SE 95% CI B SE 95% CI B SE 95% CI Book reading 0.100** 0.035 [0.031, 0.170] 0.059ϯ 0.031 [−0.002, 0.120] 0.113*** 0.023 [0.067, 0.159] Social norms 0.385*** 0.035 [0.316, 0.453] 0.178*** 0.029 [0.122, 0.234] Personal norms 0.207*** 0.030 [0.148, 0.266] Female 0.150* 0.064 [0.025, 0.275] −0.010 0.056 [−0.119, 0.100] −0.010 0.042 [−0.092, 0.072] Age −0.072*** 0.019 [−0.11, −0.034] −0.057** 0.017 [−0.091, −0.024] −0.013 0.013 [−0.039, 0.012] Parents' education −0.016 0.032 [−0.078, 0.047] −0.009 0.028 [−0.064, 0.045] 0.025 0.021 [−0.016, 0.065] Income −0.068 0.053 [−0.173, 0.036] −0.064 0.047 [−0.155, 0.028] −0.018 0.035 [−0.086, 0.051] Empathy 0.451*** 0.045 [0.363, 0.539] 0.516*** 0.042 [0.434, 0.599] 0.374*** 0.035 [0.305, 0.442] constant 2.909*** 0.387 [2.149, 3.669] 1.037* 0.352 [0.345, 1.730] 0.675* 0.266 [1.197, 0.152] R2 0.200 0.452 0.530 F 25.966*** 73.264*** 87.834*** ϯ p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Table 4. Direct and indirect effects.

B SE 95% CI Total effect 0.151 0.025 [0.101, 0.201] Direct effect 0.113 0.023 [0.067, 0.159] Indirect effects Total indirect effect 0.038 0.012 [0.015, 0.064] Book reading → SN → PB 0.018 0.007 [0.005, 0.033] Book reading → PN → PB 0.012 0.007 [0.000, 0.027] Book reading → SN → PN → PB 0.008 0.003 [0.002, 0.015] Note: The standard error (SE) and 95% CI of indirect effects are based on bias-corrected bootstrap samples. SN = social norms, PN = personal norms, PB = prosocial behavior. As for the specific indirect effect through social norms, results showed that book reading was significantly associated with social norms (B = 0.100, p = 0.004, 95% CI = [0.031, 0.170]), which in turn significantly predicted prosocial behavior (B = 0.178, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.122, 0.234]). A 95% bias-corrected confidence interval based on 5,000 bootstrap samples indicated that the indirect effect through social norms was entirely above zero (B = 0.018, 95% CI = [0.005, 0.033]). With regard to the indirect effect via personal norms, we found that book reading did not predict personal norms (B = 0.059, p = 0.006, 95% CI = [−0.002, 0.120]), whereas personal norms were significantly and positively associated with prosocial behavior (B = 0.207, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.148, 0.266]). A 95% bias-corrected confidence interval based on 5,000 bootstrap samples indicated that there was not an indirect effect through personal norms since it straddled zero (B = 0.012, 95% CI = [0.000, 0.027]). In short, the specific indirect effect of social norms alone existed, whereas that of personal norms alone did not.

In terms of the indirect effect through social norms and personal norms in serials, book reading significantly predicted social norms (B = 0.100, p = 0.004, 95% CI = [0.031, 0.170]), social norms significantly predicted personal norms (B = 0.385, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.316, 0.453]), and personal norms were significantly associated with prosocial behavior (B = 0.207, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.148, 0.266]). A 95% bias-corrected confidence interval based on 5,000 bootstrap samples indicated that the indirect effect via social norms and personal norms in serials existed (B = 0.008, 95% CI = [0.002, 0.015]). That is, the sequential mediating effect of social norms and personal norms was found to link book reading and prosocial behavior among adolescents (Fig. 1).

Discussion

-

Based on the analysis of a self-collected data set. Study 2 explores the relationship between book reading, social norms, personal norms, and prosocial behavior. Through the examination of a serial-mediated model, the study found that the relationship between book reading and prosocial behavior can be mediated by social norms and personal norms. The indirect effect of social norms and the serial mediation of social norms and personal norms are both found to be significant. Such a finding supports the argument that reading books can regulate adolescents' prosocial behavior through social influence. Following, we will discuss the potential reasons for the results, as well as the theoretical and practical contributions, by synthesizing the findings of study 1 and study 2.

-

Through two empirical studies, this research explores the relationship between adolescents' book reading and their prosocial behavior. The first study supports the positive association between book reading and prosocial behavior in adolescents. The second study examines the sequential serial model of social norms and personal norms and finds book reading can predict adolescents' prosocial behavior through the mediation of social norms and personal norms.

First, this study confirms that reading books positively predicts prosocial behavior among adolescents. Despite the substantial research on the different forms of media use, such as watching TV/films and playing video games, on prosocial behavior (e.g., De Leeuw et al.[12], Greitemeyer[13], Ruth[14], Greitemeyer & Mügge[15]), there are few published findings on the association between book reading as a traditional media use and prosocial behavior. Our research adds to the media effect and prosocial behavior scholarships by focusing on book reading as an often-neglected media use. Besides, prior research often focused on the impact of reading specific book genres or content in books on prosocial behavior[20,39]. Yet, little is known about the effect of book reading in general. This research verifies such a positive effect among adolescents. Therefore, this study and its findings add to the body of knowledge on the prosocial effect of book reading. Practically, knowing the potential positive impacts of reading books on adolescents' prosocial behavior would be valuable in adolescents' moral education. For example, schools and parents can encourage adolescents to read more, which can not only cultivate their reading habits but also help to promote their prosocial development.

Second, this study shows that the relationship between book reading and prosocial behavior is mediated by social norms alone, as well as social norms and personal norms in serial. On the one hand, the indirect effect through social norms confirmed our argument that adolescents' engagement in book reading leads to their cognitive benefits that drive the prosocial outcome of book reading via the mediation of social norms. Since the previous studies on the prosocial outcomes of media use (including book reading) mostly focus on exposure to specific prosocial contents, intrinsic regulations variables (e.g., moral identity)[20], or social cognitive ability variables (e.g., empathy and prosocial thoughts)[13,16,40,41], and are widely examined. Unlike these more intrinsic variables, the improved perception of social norms, an outcome induced by more frequency of book reading and the increased level of cognitive abilities, involves individuals' perceptions of others' approval and disapproval of media use, which is more extrinsic-oriented. On the other hand, besides the specific indirect effect through social norms alone, there also exists the sequential mediating effect of social norms and personal norms in serial. These results demonstrate the function of social norms in linking book reading and personal norms and confirms the idea of internalizing social norms into personal norms[30].

Practically speaking, the empirical finding that reading books reinforces prosocial behavior through social and personal norms holds practical implications for educators and parents. Schools can develop curricula with reading books exemplifying positive values, fostering insightful classroom discussions and contributing to the development of empathetic individuals. Simultaneously, parents can establish a nurturing reading environment at home by offering a diverse range of books and encouraging discussions on characters' choices. Collaborative endeavors could include book clubs and experiential activities like role-playing. By integrating these strategies, schools and parents can jointly nurture well-rounded individuals who excel academically and exhibit empathy, compassion, and social responsibility in their interactions with others and society at large.

Finally, several limitations should be noted regarding this study. First, the two studies are based on surveys, which are limited in inferring causal relationships. Future studies can adopt experiments to establish the causal relationships between book reading and prosocial behaviors. Second, although the first study is based on nationally representative data, the data of the second study is collected in one province of China. Thus, the generalizability of the second study is relatively limited. Future studies could seek to collect more representative data and do cross-country or cultural studies to increase the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, we want to recognize that there exist other potential factors that might influence the relationships, such as certain personality traits and the genres of books. Although these aspects are not the central focus of our present research, they could serve as valuable directions for future investigations. Finally, we found that only reading books can positively predict prosocial behavior, while watching television and playing video games cannot exert a similar effect. Future studies can focus on the potential different effects of various media types on adolescents' prosocial behavior.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ai P, Li W. 2023. Does reading increase prosociality? Linking book reading with adolescents' prosocial behavior. Publishing Research 2:5 doi: 10.48130/PR-2023-0005

Does reading increase prosociality? Linking book reading with adolescents' prosocial behavior

- Received: 01 June 2023

- Accepted: 23 August 2023

- Published online: 07 October 2023

Abstract: Previous research on the influence of media on prosocial behavior often focuses on the effects of watching TV/films, playing video games, and listening to music. Yet, less attention is paid to book reading, a traditional media use that continues to be prevalent, especially in adolescents' daily lives. Going beyond the specific content reading, this study explores the relationship between general book reading and the prosocial behavior of adolescents. Based on nationally representative data, Study 1 identified the positive impact of adolescents' book reading on their prosocial behavior. From a normative influence perspective, Study 2 validated the finding of Study 1 and investigated the underlying mechanism. Theoretically, these two studies extend the literature on the effects of media use on adolescents' prosocial behavior and highlight the role of normative influence in understanding this relationship. Practically, our findings are valuable references for practitioners in the book publishing industry and generate beneficial insights for adolescents' prosocial education.

-

Key words:

- Book reading /

- Prosocial behavior /

- Social norms