-

The rapid advancement of global industrialization and urbanization has led to the release of diverse chemical pollutants, profoundly impacting the environment. With the progress in sampling and analytical techniques, an increasing number of emerging pollutants, such as pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), microplastics, and antibiotic resistance genes, have been detected in aquatic environments[1−4]. These substances raise environmental and health concerns due to their ecotoxicity, bioaccumulation potential, environmental persistence, and possible risks to human health, which have attracted increasing attention[5−9]. Recent studies emphasize the need for enhanced monitoring, risk assessment, and regulatory control of emerging pollutants to support sustainable water resource management and ecosystem protection in a changing world[10,11].

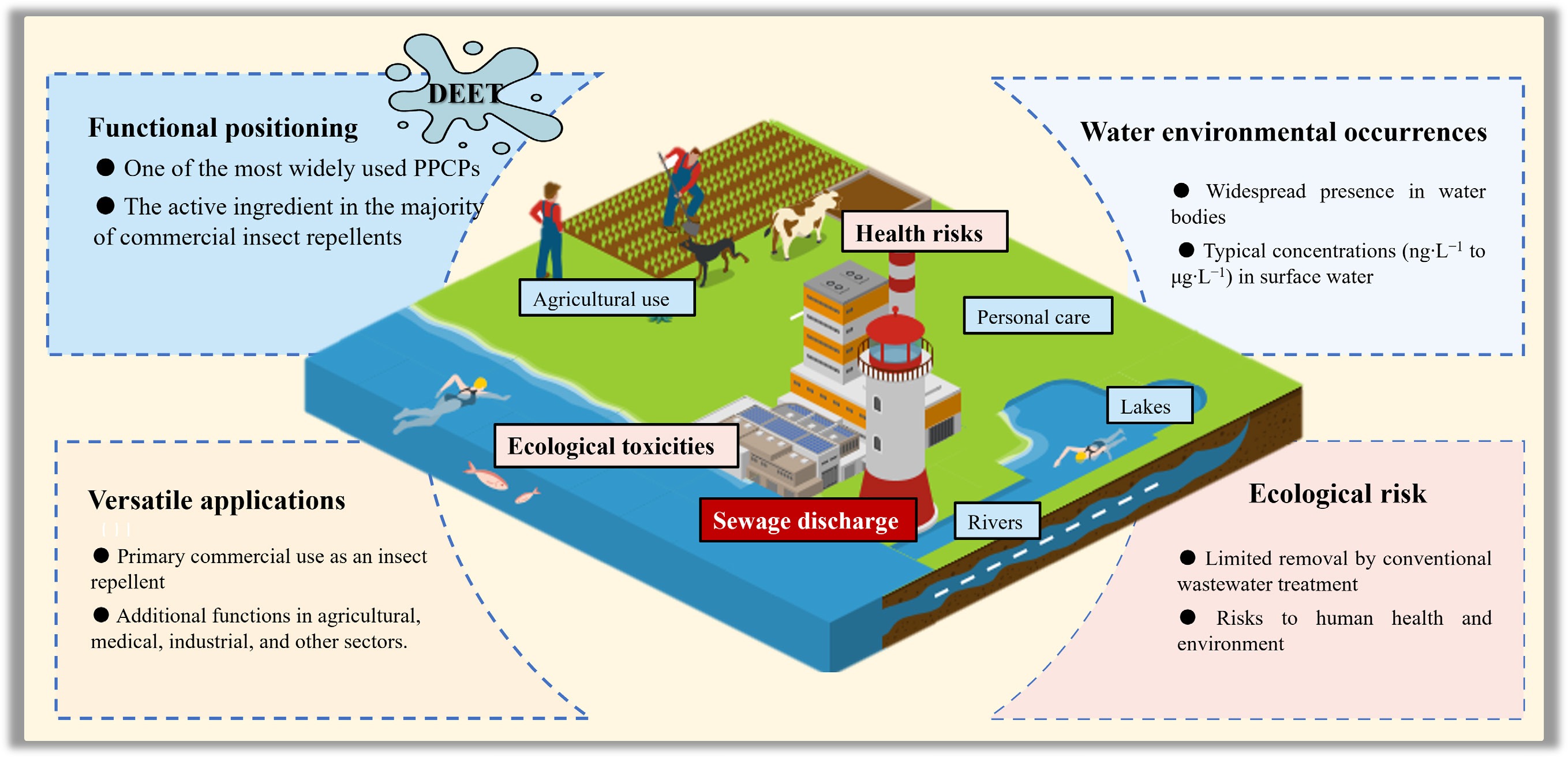

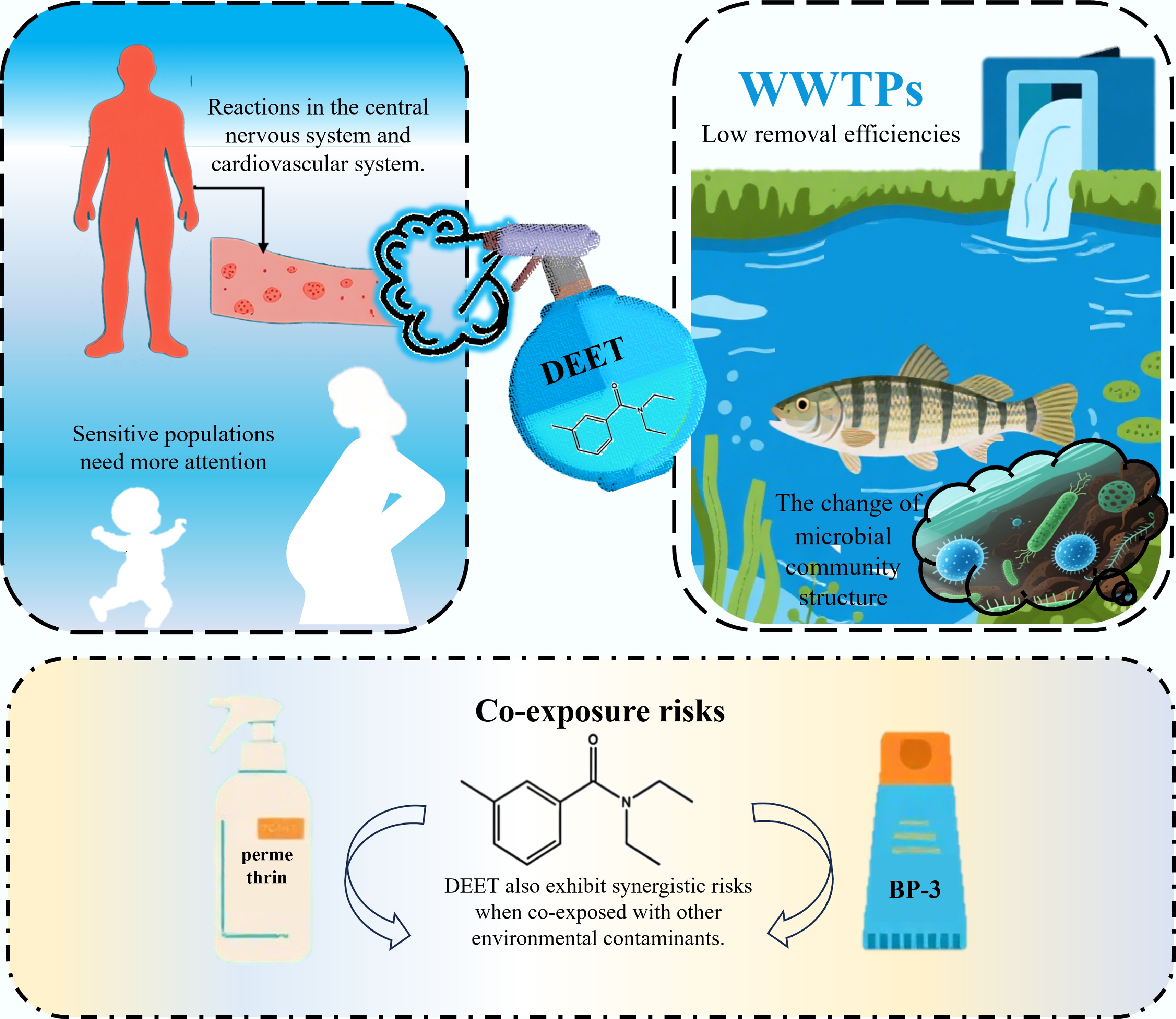

Among the emerging pollutants commonly monitored in aquatic environments, the insect repellent N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET), a widely used PPCP, has been increasingly detected worldwide. DEET was first reported in freshwater ecosystems in North America and Europe during the 1990s[12,13]. Gradually, the measured concentration range of DEET has increased above the levels reported in previous studies[14,15]. Moreover, DEET has been detected in finished drinking water, albeit at low concentrations as reported by Padhye et al.[16]. Such pervasive occurrence of DEET in water environments, and its detection in drinking water have raised concerns regarding public health and the efficacy of water treatment. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) serve as major convergence points for domestic and industrial wastewater, and play a crucial role in the removal of micropollutants. However, conventional wastewater treatment processes have shown limited and variable removal efficiency for PPCPs such as DEET, ranging from 30% to 90%[17]. As a result, a considerable fraction of these compounds can persist through treatment, entering surface water, groundwater, and marine ecosystems via effluent discharge[18,19].

Although DEET is typically detected at low concentrations in environmental media, rare but severe health incidents, including fatalities, have been reported, primarily associated with accidental ingestion or dermal misuse resulting from failure to adhere to product label warnings[20]. Toxicological studies have indicated that DEET can induce dermal hypersensitivity and neurological toxicity. In aquatic ecosystems, DEET exposure has been shown to reduce cytochrome concentrations and inflict irreversible damage to algal cells[21,22]. Furthermore, embryonic zebrafish exposed to DEET exhibited multifactorial toxicity affecting cardiac function, immune response, and neural development[23]. Even at environmentally relevant concentrations, DEET can alter the composition and function of riverine microbial communities[24]. In light of its persistence and ecological impacts, DEET has been identified as a priority organic micropollutant in some studies[25,26]. These findings stress the importance of enhanced monitoring and targeted management of DEET within wastewater treatment systems and broader environmental oversight frameworks.

This review aims to: (1) systematically examine the commercial and other reported applications of DEET; (2) identify the sources of its occurrence in aquatic environments; (3) summarize its detected concentration levels based on a comprehensive review of recent literature; and (4) perform a preliminary environmental risk assessment. This study should enhance the understanding of DEET's occurrence and risks, highlighting the importance of monitoring and regulating this emerging contaminant.

-

Originally developed to protect military personnel in insect-infested regions, DEET has become a globally authorized commercial repellent and is recognized as one of the most effective and widely used products against mosquitoes on the market[27,28]. Beyond its primary application, DEET exhibits a broad spectrum of utility across various fields. In agriculture, it acts as a feeding deterrent for pests such as fruit flies, which are sensitive to DEET via gustatory responses, indicating its potential for crop protection[29,30]. In pharmaceuticals, DEET finds application as a dermal penetration enhancer for transdermal drug delivery systems[31,32]. In materials science, DEET can plasticize poly(L-lactic acid) by significantly reducing the glass transition temperature and altering crystallization kinetics[33], and it can serve as a safer alternative to toxic amide solvents in the synthesis of metal-organic frameworks[34]. Furthermore, DEET has been explored for potential applications, including as a dye aid, flame retardant carrier, and leveling agent[35].

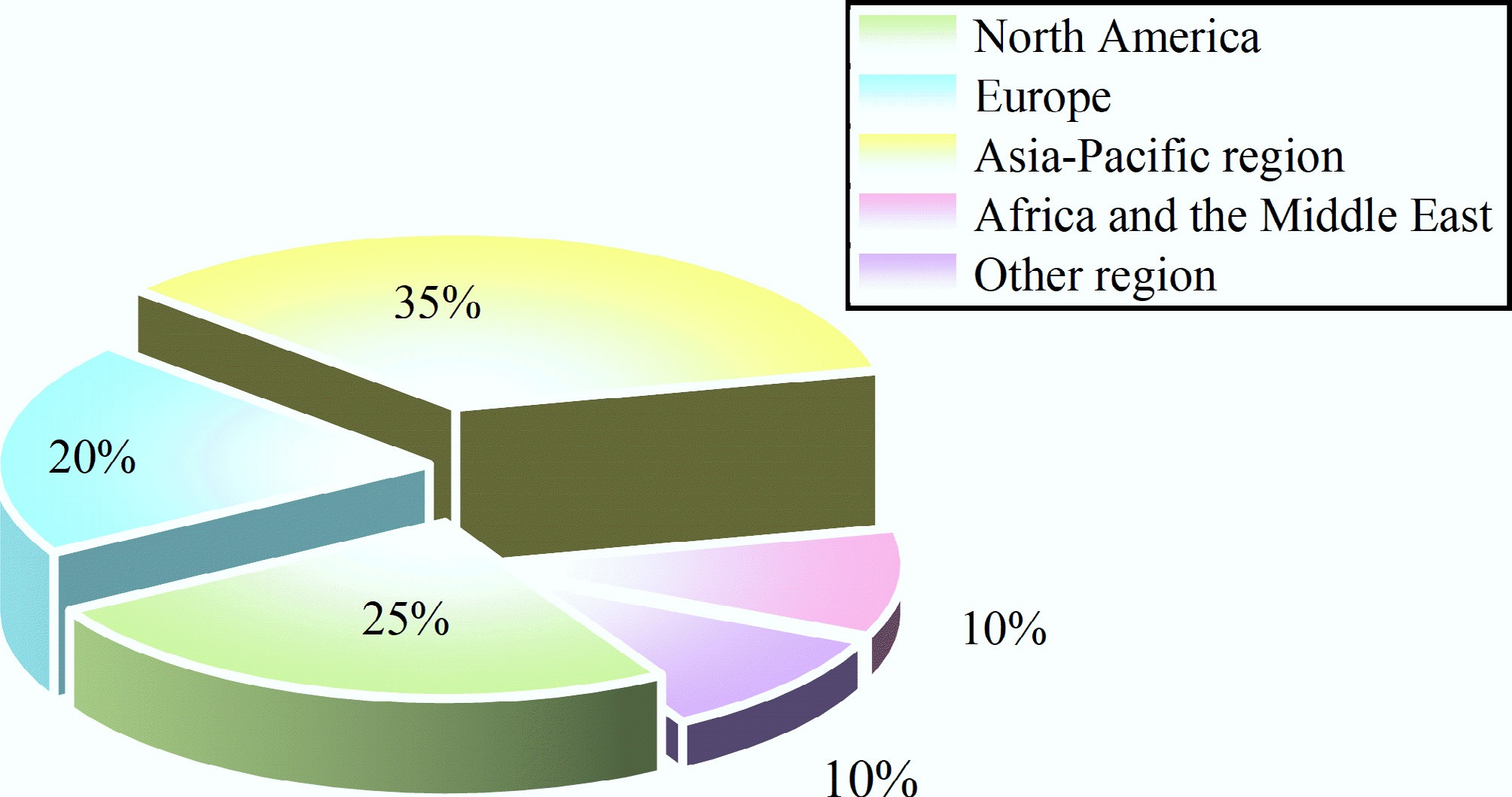

The global insect repellent market is substantial and expanding, with an estimated value of USD

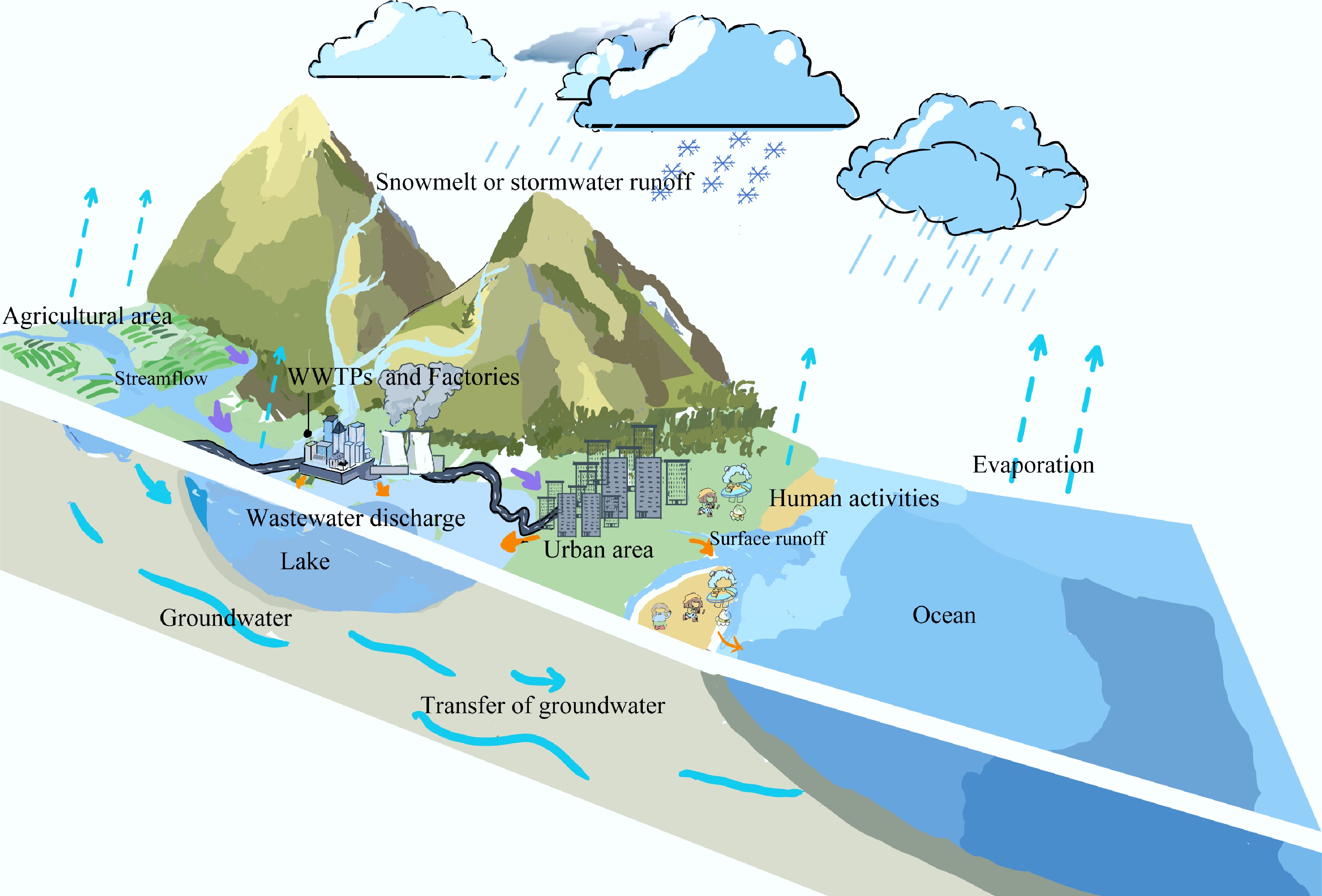

${\$} $ ${\$} $ DEET enters water environments through multiple pathways, as shown in Fig. 2, with consumer product use being the primary source. The direct application of DEET-containing repellents to skin or clothing, as well as subsequent swimming or other water activities, can lead to direct wash-off into surface waters[38,39], while a smaller fraction may enter the air via evaporation[40]. Subsequent activities, such as laundering treated textiles and bathing, introduce DEET into sewage systems[41]. Furthermore, a portion of the dose absorbed through the skin is excreted and enters domestic wastewater[42,43]. As conventional wastewater treatment often fails to completely degrade DEET, it is subsequently discharged into water bodies[44,45]. Beyond domestic pathways, agricultural use of DEET can lead to its entry into surface water and soil via irrigation and stormwater runoff, which transports pollutants from the land surface[46]. Landfill leachate generated from the decomposition of discarded products and precipitation also serves as a pathway, facilitating the migration of DEET into groundwater and surface water[47]. Consequently, due to its extensive use and persistent discharge, DEET is now frequently detected in aquatic environments worldwide, with its detection frequency on the rise[48,49].

-

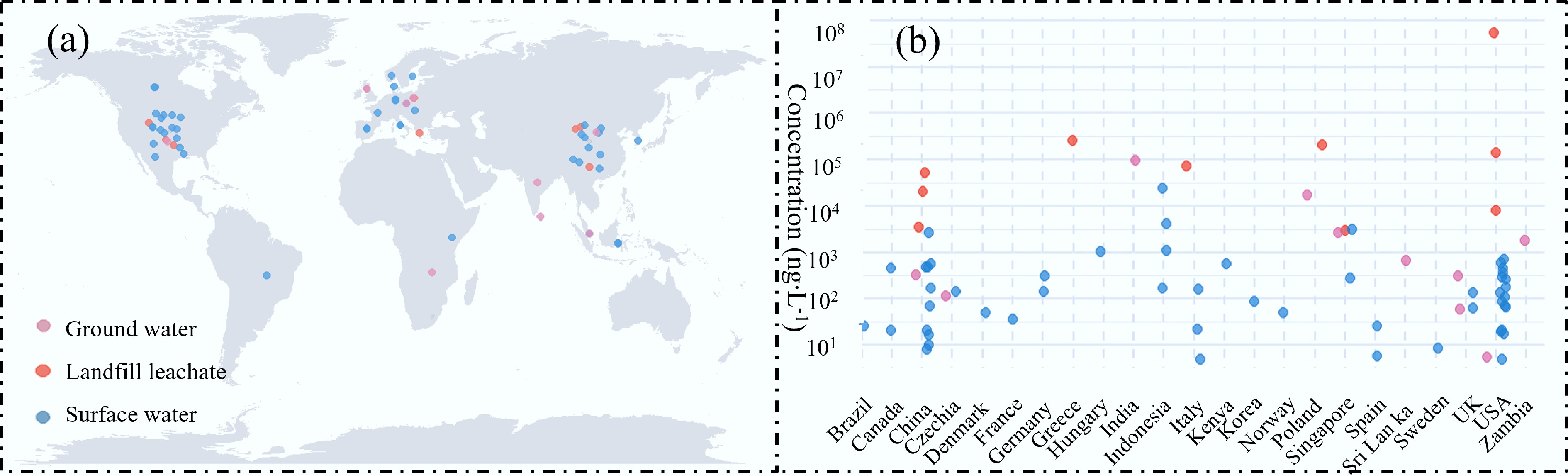

Surface water is a critical environmental medium for sustaining the health and stability of aquatic ecosystems. As summarized in Fig. 3a, DEET has been detected in surface waters across multiple global regions with concentrations ranging from nanograms per liter (ng·L−1) to micrograms per liter (μg·L−1), with elevated levels typically occurring in densely populated and tourism-intensive regions. In North America, DEET was found in 73% of US streams surveyed, especially those affected by wastewater effluent, urban runoff, and livestock operations, with concentrations exceeding 0.02 μg·L−1[50]. Similar detection patterns have been reported in Europe. In Asia, rapid industrialization and urbanization in countries such as China and India have led to notable increases in DEET concentrations in surface waters. For instance, an average level of 0.14 μg·L−1 was reported in Chinese surface waters[51].

Figure 3.

Overview of DEET (a) reported globally, and (b) maximum concentrations of DEET in different counties.

Tourist activities contribute to elevated DEET levels in coastal waters. In seawater samples from the Banyuls-sur-Mer and Collioure bathing areas on the Northwestern Mediterranean coast, concentrations reached 0.0354 and 0.0322 μg·L−1[52], exceeding those previously reported in the Western Mediterranean (0.506–1.21 ng·L−1)[53], and the northern Adriatic Sea (5.0 ng·L−1)[54], likely due to widespread use of repellents by beachgoers. Agricultural areas also serve as important sources of DEET in surface waters. In the River Cam (UK), which drains extensive farmland, a maximum concentration of 132.0 ± 4.3 ng·L−1 was recorded[55], comparable to levels in Lake Balaton, Hungary[56] but higher than those in other UK rivers such as the Test and Itchen[57]. These spatial patterns highlight the role of agricultural runoff in introducing DEET into aquatic systems.

DEET is partially introduced into groundwater through the discharge of wastewater effluent. In Vellore, India, DEET was detected in 96% of groundwater samples, primarily in densely populated southern and central zones, averaging 30 μg·L−1 and reaching a maximum of 92 μg·L−1[58]. This contamination has been attributed to sewage leakage, pesticide application, and inadequate sanitation infrastructure, highlighting the environmental challenges in densely populated regions with insufficient waste management. A pan-European survey on polar organic persistent pollutants in groundwater identified DEET as one of the most frequently detected compounds, with an occurrence rate of 84% and a maximum concentration of 454 ng·L−1[59]. Its recurrent detection stresses its persistent environmental presence and suggests a potential long-term contamination risk.

As a widely used insect repellent, DEET exhibits seasonal variation in use, peaking in summer, and accumulates in municipal solid waste and landfill leachates. Outdoor application also facilitates its transport to landfill sites via surface runoff. Among emerging contaminants detected in landfill leachate, DEET is one of the most frequently identified, with concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 103 μg·L−1[60]. The presence of DEET in leachate poses a risk of groundwater contamination, particularly given its moderate hydrophobicity and limited water solubility. Andrews et al. found DEET in leachate from Oklahoma's (> 25-year) landfills (up to 52.6 μg·L−1) and in groundwater 90 m from a closed landfill[61], indicating its environmental persistence and migration capacity. Similar findings were reported in Poland, where DEET was found in groundwater samples surrounding landfills (0.019–16.901 μg·L−1)[62].

Notably, in the Hranice karst region, Oppeltová et al. hypothesized that deep-circulation thermal karst waters would be free from recent anthropogenic contaminants, yet emerging substances, including DEET, were detected in surface water (141 ng·L−1), groundwater (114 ng·L−1), and thermal karst water (132 ng·L−1)[63]. Furthermore, studies have suggested that DEET can be detected in drinking water, albeit generally at low concentrations[16,64]. It might pose health risks to humans via drinking water and biological accumulation. Special attention should be paid to sensitive populations, such as children and pregnant women.

While existing research primarily focuses on DEET's widespread occurrence in water bodies, emerging evidence indicates that it also accumulates in sediments. It has been detected in both marine sediments[65], and lake sediments[66]. Teysseire et al. analyzed 193 surface sediment samples (0–2 cm) from Canadian lakes, and detected 44 trace organic compounds associated with anthropogenic activities. Among these, DEET emerged as one of the most common pollutants, found in 93% of the samples at a median concentration of 339 ng·g−1. Its concentrations spanned several orders of magnitude (12.6−23,700 ng·g−1)[67]. However, it's low to moderate sorption capacity to sediments (logKoc = 2.9) suggests that only a small fraction of DEET tends to adsorb to sediments, favoring its mobility and distribution in the water column.

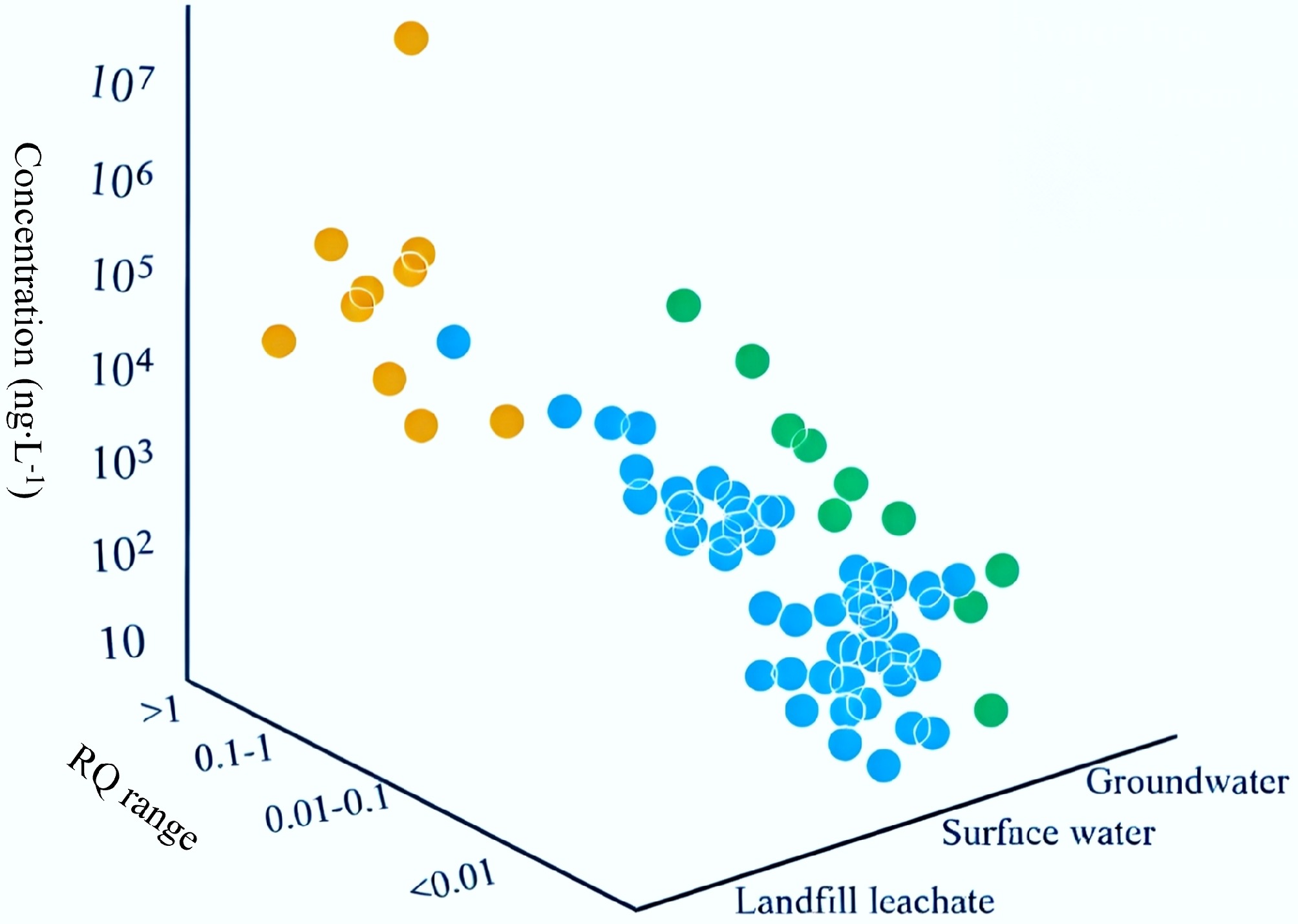

Overall, landfill leachate represents the most heavily contaminated water matrix, with pollutant concentrations often spanning from μg·L−1 levels and even reaching mg·L−1 ranges (Fig. 3; Supplementary Tables S1a, S1b, S1c)[24,47,52−55,58,61−63,68−120]. WWTPs could mitigate this contamination by removing certain pollutants, and the treated effluent underwent further dilution when discharged into surface water or groundwater, resulting in significantly lower concentrations at the ng·L−1 level[121,122]. Drinking water showed the lowest levels of DEET contamination, which could be attributed to both advanced purification processes in water treatment facilities and the generally better quality of source waters[19,123]. It is also noteworthy that current research on DEET distribution reflects a significant geographical bias, with data still lacking for many countries, highlighting an important gap for future monitoring efforts. Current surface water monitoring sites were predominantly located in regions with intensive human activities, whereas groundwater in remote areas might be a primary exposure source due to agricultural or chemical industry leaks. Concurrently, the majority of studies focused on surface water, probably resulting in an insufficient representation of other aquatic environments.

It is also noteworthy that dengue fever and other mosquito-borne diseases are primarily prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions, including the Americas, Southeast Asia, the Western Pacific, Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean[124−126]. In some developing countries, favorable climatic conditions and limited healthcare resources lead to the widespread transmission of these diseases. As an effective mosquito repellent, DEET is widely used in these areas, but environmental monitoring data on DEET in these regions are often lacking.

-

As a broad-spectrum insect repellent highly effective against various species of mosquitoes, ticks, flies, and other pests[127−130], the EPA approved and recommended the use of DEET due to its low risk to human health[131]. However, increasing evidence indicates potential adverse effects on both human and environmental health.

Figure 4 summarizes the potential risks of DEET to human health, aquatic ecosystems, and microbial communities. In humans, DEET exposure has been associated with adverse effects primarily involving the central nervous and cardiovascular systems, along with dermatological reactions such as urticaria and hemorrhagic vesiculobullous erosions, particularly following the use of products containing ≥ 50% DEET[132]. High-level exposure can lead to more severe outcomes, including seizures and neurological abnormalities[133,134]. Prolonged or improper use may intensify these health risks, especially in susceptible populations.

DEET's adverse effects on sensitive populations extend to endocrine disruption and bone development. Zhang et al. demonstrated that DEET induced multifactorial toxicity in zebrafish embryos, impairing cardiac, immune, and nervous system functions during early development[23]. Zhu et al. reported that DEET might interfere with sex hormone levels, posing unfavorable risks to bone health in children and adolescents, particularly those under 12 years old and non-overweight individuals[135]. These findings indicate DEET's developmental toxicity, reinforcing the need for caution in its use by pregnant women and infants. Another study linked certain pesticides/insecticides to decreased muscle strength in people with diabetes[136].

From a genotoxicity perspective, in vitro experiments have indicated that DEET might increase the micronucleus frequency in human lymphocytes and impact the retinoblastoma gene expression[137]. Moreover, DEET exhibited synergistic risks when co-exposed with other environmental contaminants. Picinini-Zambelli et al. found that even at environmentally relevant concentrations, DEET (3.0 ng·L−1), and caffeine (2.5 ng·L−1) induced DNA damage in eukaryotic cells[138]. When DEET was used concurrently with Benzophenone-3 (BP-3), an ingredient commonly found in sunscreens, a positive correlation in their percutaneous absorption was observed. This might lead to an augmented uptake of both substances, thereby heightening potential health risks[139]. Similarly, co-exposure to DEET and permethrin was shown to exert synergistic cytotoxic effects on sinus epithelial cells, potentially contributing to the pathogenesis of chronic sinusitis[140]. Additional studies suggested that DEET might possess carcinogenic potential and adversely affect human nasal mucosal cells[141].

The environmental impact of DEET on aquatic ecosystems has received growing scientific attention. At high concentrations, DEET has been shown to significantly reduce cytochrome content and induce irreversible damage in algal cells, thereby inhibiting their growth[21,22]. This impairment subsequently weakens photosynthetic activity and compromises energy transfer efficiency, offering insights into the ecotoxicological implications of DEET at lower trophic levels in aquatic food webs. In addition, studies have indicated that DEET can inhibit growth in certain fish species and disrupt neurotransmitter function[142]. Although DEET is not generally considered highly bioaccumulative, it has been detected in mussel tissues from the US Great Lakes region, as well as in bees and honey from Colima, Mexico[143,144]. These findings suggest that DEET may undergo trophic transfer and accumulate in higher trophic-level organisms, posing potential risks of biomagnification. While the ecological impacts of DEET are generally less severe than those of heavy metals or antibiotics, its extensive use, environmental persistence, and adverse effects even at low concentrations have raised increasing concern regarding its long-term environmental significance.

Microbial communities play a pivotal role in ecosystem functioning due to their high ecological relevance and sensitivity to environmental changes, making them critical indicators for assessing pollutant impacts[145,146]. Lawrence et al. exposed riverine microbial communities to DEET at environmentally relevant concentrations (0.1–1 mg·L−1), and observed structural shifts in community composition, along with minor alterations in metabolic activity and extracellular polymeric substance profiles[24]. Lopez et al. found that DEET interfered with the nitrogen cycle by disrupting nitrifying bacterial communities, exhibiting moderate nitrification inhibition rates (38.7%) at 10 mg·L−1[147], though such an effect is likely limited under typical environmental conditions where concentrations are far lower. Additionally, DEET exhibited antimicrobial properties, with Kalaycı et al. documenting dose-dependent inhibitory effects, particularly against yeast and fungi[148]. These findings collectively highlight the potential of DEET to alter microbial community structure and function, with possible implications for ecosystem-level processes.

A significant knowledge gap remains regarding the ecotoxicity of DEET, particularly the health implications for sensitive populations such as children and pregnant women under long-term, low-dose exposure scenarios. In addition, the real-world impact of DEET remains poorly understood, partly due to its generally low detected concentrations and insufficient toxicity data. Studies on microbial responses are also limited, with a particular lack of investigation into complex community-level exposures under environmentally relevant conditions. Such long-term exposure could potentially promote microbial adaptation and resistance development, ultimately disrupting ecological balance. Notably, no direct evidence is currently available on whether DEET influences the proliferation or transmission of antibiotic resistance genes.

Ecological risk assessment

-

The Risk Quotient (RQ) is a commonly used method to assess the potential environmental risk by comparing its measured environmental concentration (MEC) to the predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC). The formula for calculating the RQ is:

$ \mathrm{R}\mathrm{Q}=\dfrac{\mathrm{M}\mathrm{E}\mathrm{C}}{\mathrm{P}\mathrm{N}\mathrm{E}\mathrm{C}} $ The spatial distribution of micropollutants and their associated risk levels often varies considerably across regions. To better assess environmental risk on a broader spatial scale, and prevent some extreme local cases from being inappropriately generalized to represent global environmental risk, Yang et al. introduced the definition of four rank classes, their corresponding RQ ranges, and assigned weighting indexes (Wx) (Table 1), incorporating both the intensity and frequency of risks to calculate the Weighted Average Risk Quotient (WARQ)[49]. The weighted average of DEET concentration was calculated, and then the WARQ and a preliminary risk assessment was obtained in different water environments. The formula is as follows:

$ WARQ=\dfrac{\sum_{X=1}^4RQ(x,water\; type)\ \times\mathrm{\ W}x}{f(x,total)} $ where, RQ(x,water type) is the number calculated by its MEC in different water environments and PNEC, and f(x,total) is the total counting number of RQ in one kind of water environment.

Table 1. Definition of the four rank classes, their corresponding RQ ranges, and assigned weighting indexes

Rank class (x) RQ range Weight index (Wx) 1 > 1 1 2 0.1–1 0.5 3 0.01–0.1 0.25 4 < 0.01 0 Different studies reported significant variations in the PNEC of DEET for the aquatic environment. The most conservative PNEC for DEET in aquatic ecosystems was 10.4 mg·L−1, as derived from the chronic no-observed-effect concentration (NOEC) for algae divided by a 50-fold assessment factor, in accordance with the 2003 EU Technical Guidance Document[149]. Sun et al. tested the acute toxic effects of DEET on Chlorella vulgaris, Daphnia magna, and Brachydanio rerio, and evaluated the ecotoxicological risks[150], yielding the PNEC of 0.407 mg·L−1. Ricky et al. employed acute EC50 data (96-h EC50 for Chlorella of 17.4 mg·L−1) with a more stringent 1,000-fold assessment factor, further reducing the PNEC to 0.017 mg·L−1[22].

The assessment factor, and type of toxicity data significantly influenced the results. Gao et al. identified the sensitivity order of algae > crustaceans > amphibians > fish > worms > insects > annelids using the species sensitivity distribution (SSD) method, which yielded a notably lower PNEC of 0.20 mg·L−1[51]. This discrepancy could be attributed to several factors: (1) Species sensitivity and geographical differences; (2) Data representativeness, as the selected species focused on algae, fish, and water fleas, neglecting other key sensitive groups in freshwater communities; (3) Bias in the selection of toxicity endpoints, since chronic NOEC data, generally more conservative than acute EC50 values, were not prioritized. A single high PNEC value may overlook the ecological risks of DEET to sensitive species such as algae. To establish scientifically sound environmental standards for DEET, it is essential to integrate the following factors: region-specific species sensitivity data, chronic toxicity effects from long-term exposure, and the selection of ecologically representative species based on community structure. Adopting such a comprehensive strategy enables a more balanced and protective approach to environmental risk assessment.

Merel & Snyder emphasized the challenges in assessing DEET pollution levels due to variations in reported concentration metrics (median, average, or extreme values), with the maximum concentration being the only metric unaffected by the scale of sampling activities (i.e., the number of samples and temporal scope)[151]. Therefore, this study adopted the maximum reported MEC from each investigation to reflect the worst-case pollution scenario or exposure level, and a PNEC of 0.017 mg·L–1 was used to ensure the conservatism and scientific integrity of the assessment. Based on the calculated RQ for DEET in global aquatic environments, the WARQ values were determined as 0.02 for surface water, 0.85 for leachate, and 0.3 for groundwater. These results indicate a moderate ecological risk posed by DEET, with the highest risk observed in landfill leachate. The elevated WARQ in leachate, coupled with its characteristically high DEET concentrations (Fig. 5), highlights the need for targeted management and mitigation strategies in these high-risk settings.

The removal of DEET

-

The widespread presence of DEET in the environment was partly linked to wastewater discharge. Conventional wastewater treatment processes exhibit limited and variable removal efficiency for DEET, typically ranging from 10% to 90%, allowing a substantial portion to persist in effluent and enter natural water bodies[151,152]. For example, Peng et al. reported that DEET was one of the emerging organic contaminants with relatively low removal (31.9%) in subsurface wastewater infiltration systems[153]. Similarly, biological greywater treatment processes have been shown to be insufficient for complete DEET elimination, leading to its potential accumulation with water reuse[154].

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are widely applied for degrading organic pollutants such as DEET by generating highly reactive free radicals (e.g., hydroxyl radicals •OH, sulfate radicals SO4•−). Xu et al. reported that •OH and SO4•− exhibited comparable effectiveness in degrading DEET[155]. The O3/Mn oxidation process was also shown to enhance •OH generation, resulting in a DEET removal efficiency approximately four times greater than that of ozonation alone[156]. Additionally, hybrid systems such as ultraviolet-activated peracetic acid have proven effective in removing residual micropollutants like DEET from reverse osmosis or nanofiltration concentrates[157]. However, some combined processes may introduce unintended consequences. For example, a system coupling UV-LEDs with FeCl3 coagulation was found to promote the formation of disinfection by-products such as trichloromethane and haloacetic acids, highlighting the need for careful environmental risk assessment when implementing such techniques[158].

Microbial communities can adapt to environmental conditions through natural selection, developing specialized structural and functional traits that facilitate the degradation of trace organic contaminants[159]. Microbial removal of such pollutants often relies on the synergistic action of cometabolic and metabolic pathways[160]. Li et al. investigated seven emerging contaminants and reported that biofilm systems achieved notable removal efficiencies for DEET and sulfamethoxazole (> 50%), with further enhancement under external carbon supplementation. Carbamazepine removal was also significantly improved, highlighting the role of cometabolic processes in biodegradation[161]. During treatment, specific degraders may undergo selective enrichment, strengthening community-level degradation capacity for trace organics. Although several studies have reported DEET biodegradation in aerobic systems[162−164], the number of identified DEET-degrading strains remains limited (Table 2).

Table 2. Microbial resources for DEET degradation

Name Type Mechanism Intermediate product Ref. Cunninghamella elegans ATCC 9245 Fungus Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase N-deethylation (DEET → N-ethyl-m-toluidine); N-oxidation (DEET and N-ethyl-m-toluidine are oxidized to their respective nitrogen oxides) [165] Mucor ramannianus

R-56Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase N-deethylation (DEET → N-ethyl-m-toluidine);

Partial N-oxidation (only DEET oxidized to N,N-diethyl-m-toluidine-N-oxide)Pseudomonas putida

DTBBacterium DEET hydrolase

(encoded by the gene dthA)Catalyzing the hydrolysis of the amide bond in DEET into

3-methylbenzoate and diethylamine.[166,167] Pseudomonas putida DTB, for instance, could use DEET as a sole carbon and energy source under aerobic conditions. The initial and key step was hydrolysis of the amide bond, catalyzed by DEET hydrolase (encoded by dthA), yielding 3-methylbenzoate and diethylamine. The former was further metabolized via 3-methylcatechol through the meta-cleavage pathway, while diethylamine was hydrolyzed to acetaldehyde and assimilated into central metabolism[167,168]. However, Helbling et al. observed that DEET was not fully mineralized in activated sludge systems. It was transformed into more hydrophilic intermediates through N-deethylation and aromatic methyl group oxidation. The N-deethylation product degraded rapidly, whereas the oxidation product was more persistent[169]. Enzymatic degradation has also emerged as a promising approach for removing emerging contaminants[170−173]. For example, van Brenk et al. demonstrated that a spent mushroom substrate (Agaricus bisporus), rich in laccase and peroxidase, degraded 90% of DEET within 7 d via enzymatic oxidation[174].

Future research should prioritize several key directions to advance the mitigation of DEET contamination. Firstly, optimization of AOPs is essential, including refining operational parameters, developing more efficient radical generation systems, and integrating toxicity evaluation tools to achieve complete mineralization and environmentally benign treatment of DEET. Secondly, in-depth investigation into the microbial degradation mechanisms of DEET, particularly the metabolic pathways and key enzyme systems, should be pursued to enhance biodegradation efficiency. Thirdly, hybrid treatment strategies that combine physical, chemical, and biological processes should be optimized to leverage their synergistic effects, improving removal performance while reducing operational costs. Beyond DEET removal, greater attention should be directed toward assessing the long-term ecological impacts of DEET and its transformation products on aquatic ecosystems. Finally, the development and application of novel analytical methods are critical to improving the understanding of the environmental fate and behavior of DEET and its metabolites.

-

This review summarizes the widespread occurrence and contamination status of DEET in global aquatic environments. In addition to its primary use as an insect repellent, DEET has been reported to serve functions in agricultural, medical, industrial, and other sectors. Driven by these diverse applications, DEET has been detected in a variety of aquatic systems, with its distribution influenced by factors such as consumer usage patterns, anthropogenic activities, agricultural practices, and environmental conditions. Globally, DEET is found in surface waters at concentrations in the ng·L−1 range, generally representing low risk levels, whereas landfill leachate is the most contaminated aquatic matrix, with concentrations ranging from μg·L−1 to mg·L−1. Although DEET exhibits low persistence and bioaccumulation potential, it may still pose ecological risks, particularly in sensitive habitats and regions with limited wastewater treatment infrastructure. The regulation of emerging contaminants such as DEET faces several challenges, including insufficient global monitoring data, incomplete ecological risk assessment, and limitations in detection and removal technologies. Addressing these issues will require establishing a dynamic monitoring–assessment–regulation framework, enhancing international data and methodology sharing, and promoting risk-based prioritization and adaptive management strategies.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/aee-0025-0009.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Zhao Y; resources, methodology: Cui S; data curation: Zhao Y, Jia Q; visualization: Jia H; investigation: Wei J; funding acquisition: Wang J, Cui S; formal analysis, writing-original draft: Zhao Y, Wei J; writing-review & editing: Zhao Y, Wang J, Jia Q, Ma Q, Jia Q; supervision: Ma Q, Cui S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42007222), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 3132025170).

-

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

-

DEET is widely detected in aquatic environments, with detection frequencies increasing.

Landfill leachate is the most contaminated water matrix.

Advanced water treatment technologies are more effective in removing DEET.

A moderate ecological risk level for DEET is indicated by weighted average risk quotients.

Significant data gaps in global monitoring and ecotoxicity hinder a comprehensive risk assessment.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao Y, Wang J, Jia Q, Ma Q, Jia HL, et al. 2025. The impact of N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide in aquatic environments: occurrence, fate, and ecological risk. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e009 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0009

The impact of N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide in aquatic environments: occurrence, fate, and ecological risk

- Received: 29 August 2025

- Revised: 28 October 2025

- Accepted: 10 November 2025

- Published online: 28 November 2025

Abstract: Among the numerous emerging contaminants detected in aquatic environments, the insect repellent N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) is one of the most frequently identified worldwide. Its presence stems mainly from the use of consumer products, with subsequent release into the environment via wastewater discharge and other pathways. DEET has been detected in water bodies at concentrations ranging from ng·L−1 to mg·L−1, and has been shown to elicit ecological toxicity in sensitive species. Conventional water treatment often fails to remove DEET effectively, enabling its persistence in aquatic systems and highlighting the need for cost-effective advanced treatment technologies. A preliminary risk assessment based on compiled monitoring data suggests that DEET poses ecological risks, supporting the case for strengthened regulatory oversight and targeted management. However, comprehensive risk characterization remains hindered by significant data gaps, particularly in global monitoring coverage and ecotoxicological studies. This review summarizes recent advances in understanding the applications, environmental occurrence, and ecological effects of DEET, and provides a preliminary risk evaluation, thereby helping to address knowledge gaps and promote regulatory awareness of this emerging contaminant.