-

Coffee is a popular beverage globally because of its pleasant flavour. Of these, Coffea arabica L. or Arabica coffee is one of the major cultivars[1]. Processing efficiency enhances the quality of coffee during production including the roasting practice[2]. Coffee demand is prominent and increasing annually. Brazil is the prime global coffee producer (39%), followed by Vietnam (16%), and Colombia (8%), respectively[3]. Production of this crop is widely promoted worldwide[4] including Thailand[5,6], which is ranked number 20 in global coffee production[3].

In Thailand, 16,623 tons of coffee beans were produced in 2024 from a total cultivation area of 196,026 Rai or 31,364.16 hectares. The northern part of Thailand is the major cultivation area (67.89%) and Arabica is noted as the major cultivar (64.31%) of the country, and Chiang Rai province has the largest plantation area[7]. Which, Doi Chang, Chiang Rai, is the major Arabica plantation region[5,6]. The crop has been promoted in this area since 1983 by the Royal Project Foundation of Thailand as a sustainable crop that promotes the quality of life of hill tribes and improves land and climate qualities. The Catimor varietal, namely CIFC 7963-13-28, has been developed for disease resistance. Leaf rust disease caused by Hemileia vastatrix B.&Br. is the main problem destroying coffee plantations in northern Thailand[8]. In addition, the quality of Arabica coffee of Doi Chang has been achieved and was Geographical Indication (GI) certified by the Thai government in 2007 and later in 2015 by the European Union (EU). Thus, coffee is a promising candidate for allied industries that abide by its conventional supply for food uses.

The quality of coffee is generally indicated by a cup score. The cup score is a method of the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) that is globally accredited to assess the quality of coffee based on sensory metrics, i.e., fragrance/aroma, acidity, body, flavour, sweetness, clean cup, balance, aftertaste, uniformity, and overall impression evaluated by certified Q-graders[9]. Although Doi Chang coffee is considered a unique coffee[10], with a cup score of more than 80 (specialty coffee), the quality in terms of its phytochemical profiles has not been unrevealed. Moreover, an emerging demand of consumers for quality coffee, in addition to cup score, is increasing as the third wave of coffee[11].

Sustainability is a high priority among consumers and is widely regarded as the sustainable development goal (SDG). Fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) are obvious key products that achieve SDGs, particularly in the personal care product sector, including nutraceuticals, cosmetics, and personal care products. Global growth continues to increase year on year. Accordingly, sustainable and biobased ingredients are a hotspot of consumer[12] surplus of their preferences for the edible, natural version of products[13,14].

To level sustainable applications of coffee in accordance with the conventional supplies in the food industry, its phytochemical divergences were quality profiled. Thai Arabica coffee beans originating from Chiang Rai with different degrees of roasting, i.e., light (L), medium (M), and dark (D), were comparatively assessed for total phenolic, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and fatty acid content, as well as volatile profiles. In addition, correlations of the physicochemical characteristics of coffee, especially lightness or luminosity, were exhibited as indications of coffee phytochemical profiles. Which, is feasible for use as measures of the quality control practices for coffee.

-

The reagents and chemicals used were of analytical grades unless specifically stated otherwise.

Coffee samples

-

Arabica coffee beans cultivated, harvested, and processed by a local farm allocated in Doi Chang, Chiang Rai, Thailand (Latitude: 19°49'3" N; Longitude: 99°33'28" E; Elevation: 1,074 m) were studied. The beans were roasted for 15−20 min at different temperatures to give light (180 °C), medium (200−220 °C), and dark (230 °C) roasts. Bean colour was recorded in terms of color parameters (CIELAB), which are L*, a*, and b* by a colorimetric spectrophotometer (UltraScan Vis, HunterLab, USA)[15].

Total phenolic content (TPC)

-

Coffee beans of different roasted levels were ground separately. The ground coffee (8 g) was extracted with water (24 mL) under ambient conditions with shaking (150 rpm) for 30 min, filtrated, and lyophilized. The total phenolic content of each extract was examined in comparison with gallic acid using the Folin-Ciocalteu method. In short, samples were mixed with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS No. 12111-13-6), with an addition of 7.5% Na2CO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS No. 497-19-8) and water, incubated for 1 h. The mixture was determined at 750 nm by the microplate reader (ASYS, UVM340, UK). The results were reported in mg gallic acid equivalent/g extract (mg GAE/g extract). The assessment was repeated in triplicate[16].

Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) analysis

-

The extracts were further quantified in chlorogenic acid for caffeic acid content using UPLC. UPLC analysis was carried out on an ACQUITY H-Class system equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC PDA eλ detector using a BEH C18 1.7 μm column (2.1 mm × 100 mm). The standards and solvents used in this analysis were of HPLC grade. Chlorogenic and caffeic acids (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS No. 327-97-9 and 331-39-5) at various concentrations in AcCN (LabScan, CAS No. 75-05-8) were used to prepare calibration curves. The samples were UPLC analyzed by a gradient mobile phase consisting of A: AcCN and B: 3% aq. AcOH (Merck, CAS No. 64-19-7). The eluent was programmed as follows: 0 min 100% B, 1.5 min 95% B, 3 min 85% B, 5 min 80% B, and 8 min 70% B at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The analysis was performed in three cycles[17].

Fatty acid profiles

-

The ground coffee beans were macerated in n-hexane, filtrated, and concentrated to dryness. Fatty acids in the form of fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) of each roast level were analyzed. Briefly, the extracts were esterified, individually, into FAMEs. The n-hexane extracts of each roast were mixed with toluene (Merck, CAS No. 108-88-3), and 8% HCl (Merck, CAS No. 7647-01-0), and incubated at 45 °C for 24 h. The resulting reacted solutions were partitioned with n-hexane, separately. The collected FAMEs solutions were injected (220 °C) in the splitless mode into a gas chromatograph (Agilent, 6890N, USA) equipped with a HP-5ms capillary column (Aligent 19091S433, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The temperature program was started at 50 °C (5 min), increased to 65 °C at a rate of 2 °C/min, and then 200 °C (5 °C/min, 5 min), and 250 °C (10 ºC/min) and held for 10 min, in which the carrier gas was helium (1.0 mL/min). Mass spectrophotometer (Agilent, 5973N) and the reference mass spectrum (MS-Willey7n.1database) were analyzed[18].

Volatile profiles

-

SPME fiber (Supelco, USA); divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane/divinyl benzene (DVB/CAR/PDMS) 50/30 μm fiber was conditioned according to the manufacturers recommendations before use. The freshly ground coffee samples (2 g) of different roasting levels were separately placed in sealed vials. The SPME needle was then inserted into the vial, and the fiber was exposed to the headspace (HS) above for 30 min at 50 °C. After sampling, the fiber was thermally desorbed in the GC injection port for 3 min at 250 °C[19]. The volatiles were separated using GC (Agilent 6890N) equipped with a HP-5ms column. The oven program started at 40 °C, rising to 265 °C at a rate of 7 °C/min. Helium was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Reference mass spectra were obtained from the MS-Wiley 7n.1 database. Content was reported based on the peak area of the identified compounds[20].

Statistical analysis

-

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Mean values were analyzed for significant difference at p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics software version 16.0.

-

Coffee is one of the most popular and widely consumed beverages worldwide due to its health benefits as well as its unique taste and aroma divergence with roasting levels and blends. Arabica coffee grows well on hilly, well-watered, and drained slopes[21]. Doi Chang, Chiang Rai with an altitude of 1,000 to 1,700 metres above sea level, is indicated as the major cultivation and processing area of Arabica coffee in Thailand. Arabica coffee of Doi Chang is globally qualified and GI-certified by the Thai government and the EU[5−8,10]. Nonetheless, despite the high cup score of this coffee, research on the phytochemical profiles is scarce.

The third wave of coffee is an emerging trend from a pure commodity to a specialty product, i.e., a cup score > 80[11], with increasing demand for higher quality coffee among consumers. Accordingly, the phytochemical profiles of Doi Chang Arabica coffee are crucial to ensure its quality to meet the third-wave trend demand. Considering the SDG among cosmetic consumers, the phytochemical divergence levels of coffee and its application in different sectors of FMCGs have raised concern.

Doi Chang Arabica coffee supplied from a local farmer who was awarded the Thai Coffee Excellence award in 2021[10], was investigated. The coffee was honey-processed and achieved a cup score of more than 80. Honey processing is a combined method of wet and dry processing. Coffee pulp was removed with the retention of mucilage before drying to retain a certain level of sweetness and cleanness[22].

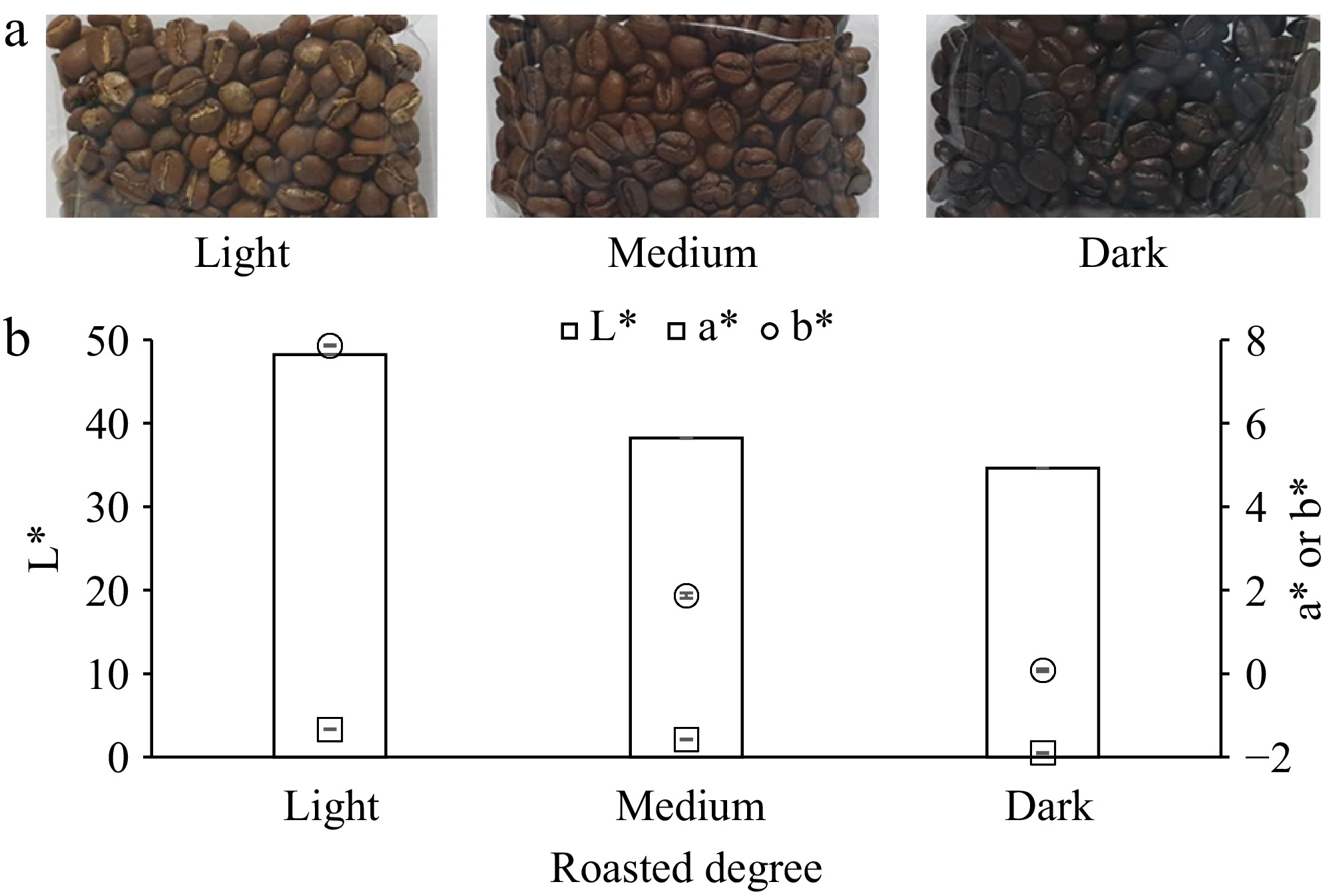

Beans with different degrees of roasting were visually differentiated (Fig. 1a) in accordance with the examined colour parameters (Fig. 1b) in terms of L*, a*, and b*. L* indicates lightness ranging from white (100) to black (0), a* indicates green (−) and red (+) colour, and b* indicates the hue of blue (−) and yellow (+).

Coffee beans with a low level of roasting therefore had significantly (p < 0.01) higher L* values with a darker colour in terms of a* and b*. Processing and roasting coffee beans positively impact the quality of coffee, and colour is an important quality parameter[21,22]. A high level of roasting darkens the coffee beans' colour[21] with a reduction in luminosity (L*) due to Millard reactions, Strecker degradation, and sugar caramelization[21,23]. Thus, L* is a prominent colour parameter used for the quality control of coffee bean processing. Additionally, nonvolatile compounds, i.e., phenolics and fatty acids, in the coffee were examined.

Phenolics and fatty acids profiles

-

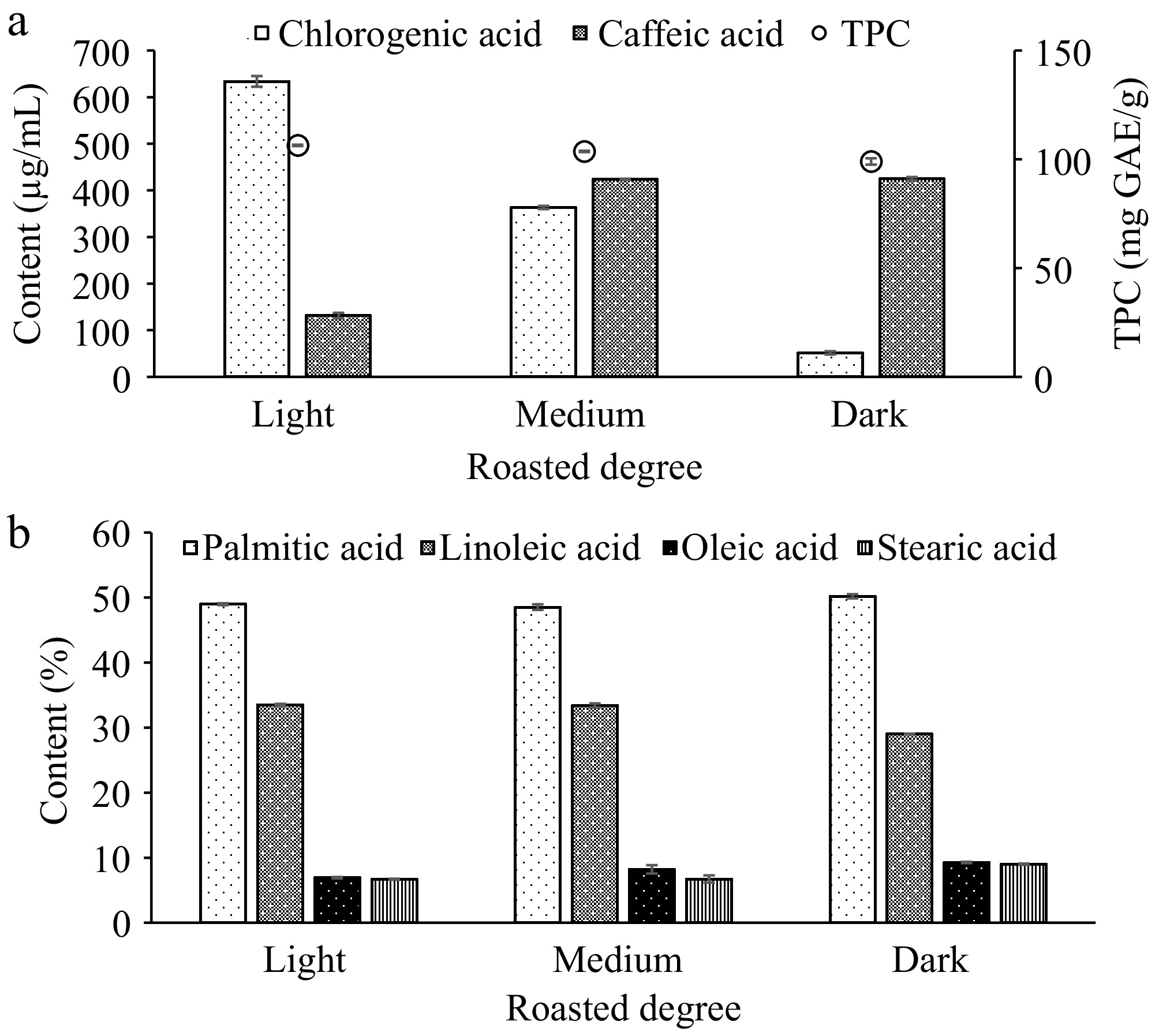

Coffee powder of different roast levels was separately extracted with water with a long shot ratio (1:3, w/v) for espresso[24]. The degree of roasting was inversely proportional to the extractive yields. That of the light roasted samples was greatest, followed by medium, and dark-roasted samples (9.50 ± 0.22, 9.38 ± 0.57, and 9.24 ± 0.37%, respectively). Roasting impacted the phytochemical profiles that correlated with the physical properties[21,23], including colour and extractive yield. Interestingly, different roasting levels insignificantly change the caffeine concentration, but phenolics[25]. The coffee's active principle content in terms of total phenolic content (TPC) of each roast was compared accordingly in addition to colour and extractive yield. High roasting level decreased the TPC (Fig. 2a), which was significantly (p < 0.01) lower in dark-roasted coffee than in medium and light-roasted coffee. The level of roast that impacted the TPC conformed with previous findings[26]. Correlations between L* and TPC were further evaluated. Notably, the colour of the roasted bean was correlated with TPC; that is, the greater the luminosity, the greater the TPC (Table 1).

Table 1. Correlation between luminosity, phenolic, and fatty acid profiles.

Correlation (r) TPC Chlorogenic acid Caffeic acid Palmitic acid Linoleic acid Oleic acid Stearic acid L* +0.8434 +0.9101 −0.9360 −0.7515 +0.5159 −0.9568 −0.5133 TPC +0.9896 −0.6216 −0.9868 +0.8742 −0.9615 −0.8724 Chlorogenic acid −0.7177 −0.9535 +0.7989 −0.991 −0.7968 Caffeic acid +0.5078 −0.2693 +0.7989 +0.267 Different roasting processes are crucial for the quality of coffee, and chlorogenic acid is regarded as a biomarker of coffee[4,24,27] in addition to its volatile profiles[28]. Accordingly, the key phenolic of coffee, chlorogenic acid, was subjectively examined, including its degradation compound, i.e., caffeic acid.

Chlorogenic acid is regarded as an important bioactive constituent of coffee that is beneficial for health. Its therapeutic properties include antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, anticancer, and anti-obesity activities, enabling several formats of health-promoting products[29]. In addition, phenolics are used for hypertension treatment[30] due to their neuroprotective ability[31]. Caffeic acid is a phenolic degradation product of chlorogenic acid with prominent radical scavenging[32] and antimicrobial activities[33]. Its pharmacological properties are aligned with those of chlorogenic acid[30,31], and it protects against metastatic colorectal cancer[34]. The chlorogenic acid content decreased with roasting, while in turn, the content of its degradation product, caffeic acid, was increased (Fig. 2a). The occurrence of chlorogenic acid was reported to be higher in green coffee than in roasted coffee[26]. Correlations between TPC and chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid content were monitored. TPC and the chlorogenic acid content were positively correlated, while TPC and the caffeic acid content were inversely correlated (Table 1). In addition, the L* value was correlated with chlorogenic and caffeic acid content. The L* value increased with increasing chlorogenic acid content but decreased with increasing caffeic acid content. Accordingly, L* was a notable indicator of the quality of coffee in terms of TPC and chlorogenic and caffeic acid content, and is feasible for quality control applications during bean processing.

In addition to the key phenolics of coffee indicating the quality of coffee with different levels of roasting, fatty acids were determined. Fatty acids are the most important factor affecting flavour formation during roasting. Coffee fatty acids are varied with different geographical origins. Arabica coffee is noted to have lower fatty acid contents than Robusta coffee. Palmitic (> 43%) and linoleic (> 30%) acids are the main fatty acids in coffee, while oleic, and stearic acids are present in lower proportions. The linoleic acid content was reported to decrease with the increasing roasting temperature[21]. Doi Chang Arabica coffee mainly contained palmitic and linoleic acids, followed by oleic and stearic acids (Fig. 2b). The quality of the studied coffee beans in terms of fatty acid profiles was therefore in agreement with a previous report. The palmitic acid content increased with increasing roasting level, while the linoleic acid content decreased[21]. Natural extracts with fatty acids are beneficial for health promotion and cosmetics. Linoleic and oleic acids are important unsaturated fatty acids for cosmetics applicable for acne, hair loss, and skin ageing treatments[20,35−38]. Palmitic and stearic acids are capable of promoting melanogenesis[39]. Correlations between fatty acids and L* value, TPC, and the phenolic contents were thereafter assessed. It should be noted that in light roasted beans, the TPC was low, as was the oleic acid content, but the linoleic acid content was relatively high. In addition, coffee with a high content of chlorogenic acid also had a high linoleic acid content. Colour is therefore an important physicochemical property that indicates the chemical profile of coffee beans.

Volatile profiles

-

The quality of coffee is defined by its volatile profiles, which significantly influences perception. Of the 800 to 1,000 volatiles in coffee, there are 23 different aroma compounds that impact pleasure and enjoyment before and during consumption. Sweet and musty aromas were frequently attributed to dark roast coffee, while acidic and fruity aromas were noted in light roast coffee[40]. Doi Chang Arabica coffee of different roast levels were comparatively examined based on their aromas (Table 2).

Table 2. Volatile profiles of different roasted coffee.

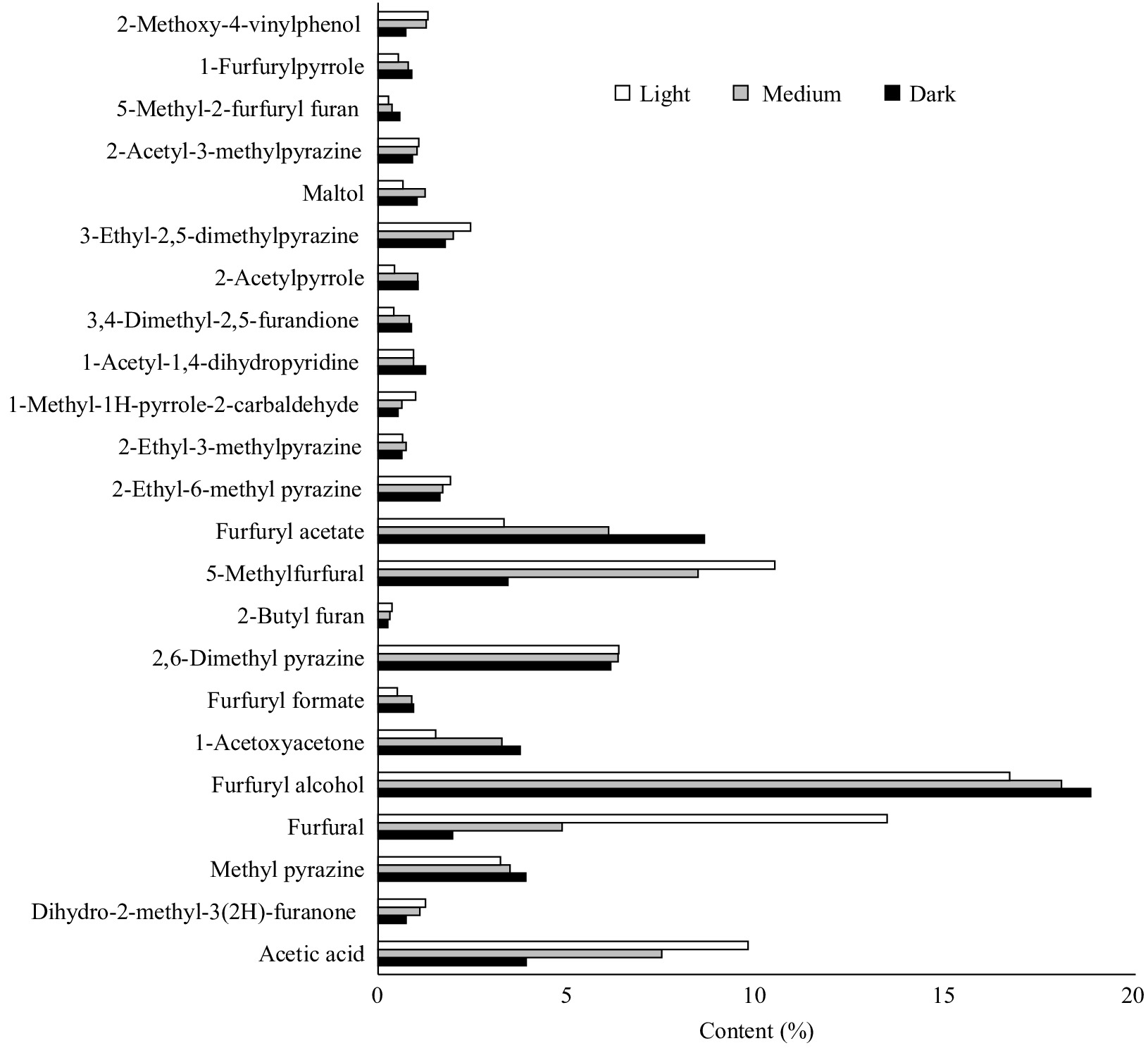

No. Retention time (min) Compound D M L 1 2.856 Acetic acid 3.91 7.49 9.77 2 3.321 1-Hydroxy-2-propanone − − 2.69 3 4.316 Pyrazine 0.43 − − 4 4.518 Pyridine 7.01 2.73 − 5 5.415 1-Methyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine 0.56 − − 6 5.825 Dihydro-2-methyl-3(2H)-furanone 0.74 1.11 1.25 7 6.192 Methyl pyrazine 3.90 3.48 3.23 8 6.473 Furfural 1.97 4.86 13.44 9 6.94 3-Methylbutanoic acid − 0.48 1.71 10 7.124 2-Furanmethanol 18.82 18.05 16.68 11 7.413 1-Acetoxyacetone 3.75 3.27 1.52 12 8.445 Furfuryl formate 0.94 0.89 0.51 13 8.577 2,6-Dimethyl pyrazine 6.14 6.34 6.36 14 8.67 2-Ethylpyrazine 2.55 1.36 − 15 8.782 2,3-Dimethyl pyrazine 0.70 0.56 − 16 9.856 2-Butyl furan 0.26 0.31 0.37 17 9.904 3-Ethyl pyridine 0.58 − − 18 10.147 5-Methylfurfural 3.43 8.45 10.48 19 10.761 Phenol 0.32 − − 20 11.094 Furfuryl acetate 8.62 6.09 3.33 21 11.145 2-Ethyl-6-methyl pyrazine 1.63 1.71 1.91 22 11.229 2-Ethyl-5-methylpyrazine − − 2.52 23 11.335 2-Ethyl-3-methylpyrazine 0.63 0.74 0.65 24 11.398 1-Methyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde 0.53 0.63 0.99 25 11.838 1-Acetyl-1,4-dihydropyridine 1.25 0.94 0.94 26 12.033 3-Methylcyclopentane-1,2-dione 0.61 0.53 - 27 12.024 2-Hydroxy-3-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-one − − 0.38 28 12.436 3,4-Dimethyl-2,5-furandione 0.88 0.82 0.42 29 12.574 Benzeneacetaldehyde − − 0.37 30 12.958 2,5-Dimethylfuran-3,4(2H,5H)-dione − − 0.92 31 13.113 2-Acetylpyrrole 1.06 1.05 0.43 32 13.163 3-Pyridinol − − 0.34 33 13.492 2-Acetyl-1-methylpyrrole 0.89 0.56 − 34 13.604 3-Ethyl-2,5-dimethylpyrazine 1.77 1.99 2.44 35 13.78 2-Furfurylfuran 1.44 0.94 − 36 13.486 Furfuryl propionate 1.01 0.85 − 37 13.958 2-Methoxyphenol 1.36 0.74 − 38 14.042 3-Ethyl-2-hydroxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one − − 0.42 39 14.608 Maltol 1.24 1.03 0.66 40 14.812 2-Acetyl-3-methylpyrazine 0.91 1.03 1.08 41 15.527 3,5-Dihydroxy-6-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyran-4-one − − 0.56 42 15.83 4-Hydroxymandelic acid − − 0.31 43 15.951 3,5-Diethyl-2-methylpyrazine 0.71 0.67 − 44 16.635 5-Methyl-2-furfuryl furan 0.57 0.28 0.24 45 16.71 1-Furfurylpyrrole 0.89 0.80 0.54 46 16.767 2-Acetyl-5-methylfuran − 0.52 0.63 47 16.923 3-Methoxybenzenethiol − 0.38 0.65 48 16.928 4-Methoxybenzenethiol 0.42 − − 49 19.428 4-Ethyl-2-methoxyphenol 0.64 0.33 − 50 20.029 Furfuryl ether 0.36 0.25 − 51 20.384 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol 0.73 1.27 1.32 52 20.642 Mercaptoethanol − − 0.32 53 35.005 Hexadecanoic acid − − 1.08 The aromas of the roasted beans were collected by HS-SPME and GC/MS analysis. HS-SPME is the most studied method for aroma profiles of coffee[21], in which DVB/CAR/PDMS 50/30 μm is a suitable SPME fibre for flavour compound (volatiles and semi-volatiles, C3−C20) sampling, including coffee aromas[19]. Aroma profiles of the coffee that were olfactory detectable[40−42] were detected under all roasting conditions (Fig. 3). The main notes were sweet, roast, musty, and nutty. Furans and pyrazines are the main volatiles of coffee[21,23,40−42], contributing to the coffee's main notes. Furans were determined to be the key abundant aromas in all roast levels, followed by pyrazines. In addition, pyrroles and a variety of aromas were detected in all roasts (Fig. 3 & Table 3).

Table 3. Aroma attributes of different roasted coffee.

No. Compound FEMA no. Aroma attribute 1 Furans Dihydro-2-methyl-3(2H)-furanone 3373 Coffee furanone 2 Furfural 2489 Sweet, almond, bready 3 Furfuryl alcohol 2491 Burnt, caramelized, creamy, sugary 4 Furfuryl formate 4542 Coffee 5 2-Butyl furan 4081 Fruity, sweet 6 5-Methylfurfural 2702 Caramelized, sweet, bready 7 Furfuryl acetate 2490 Fruity, roast, sweet 8 3,4-Dimethyl-2,5-furandione − Burnt, sweet, smoky 9 5-Methyl-2-furfuryl furan Almond, caramelized, burnt sugar 10 Pyrazines Methyl pyrazine 3309 Nutty, roasted, chocolate, coffee 11 2,6-Dimethyl pyrazine 3273 Nutty, roast, cocoa, coffee, musty 12 2-Ethyl-6-methyl pyrazine 3919 Roast, hazelnut 13 2-Ethyl-3-methylpyrazine 3155 Roast, nutty 14 3-Ethyl-2,5-dimethylpyrazine 3149 Hazelnut, fatty, coffee, chocolate 15 2-Acetyl-3-methylpyrazine 3964 Roast, nutty, vegetable 16 Misc. 1-Methyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde 4332 Burnt 17 2-Acetylpyrrole 3202 Walnut, roast 18 1-Furfurylpyrrole 3284 Waxy, fruity, coffee, vegetable 19 Acetic acid 2006 Sharp vinegar 20 1-Acetoxyacetone − Fruity, buttery, nutty 21 1-Acetyl-1,4-dihydropyridine − Caramelized, creamy 22 Maltol − Sweet, caramelized, candy, bready 23 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol 2675 Smoky, balsamic, vanilla Furfuryl alcohol and furfural were exhibited as the key aromas of Doi Chang Arabica coffee. The level of roasting directly impacted the furfural alcohol content (Table 4) in harmony with a relatively burnt or roasted odour perceived as a bitter taste with a more caramelized aroma observed due to the Maillard reaction achieved with roasting.

Table 4. Correlation between luminosity and volatile profiles.

No. Compound Correlation (r) 1 Furans Dihydro-2-methyl-3(2H)-furanone 0.9322 2 Furfural 0.9998 3 Furfuryl alcohol −0.9894 4 Furfuryl formate −0.9766 5 2-Butyl furan 0.9561 6 5-Methylfurfural 0.7671 7 Furfuryl acetate −0.9442 8 3,4-Dimethyl-2,5-furandione −0.9806 9 5-Methyl-2-furfuryl furan −0.7875 10 Pyrazines Methyl pyrazine −0.8419 11 2,6-Dimethyl pyrazine 0.5803 12 2-Ethyl-6-methyl pyrazine 0.9996 13 2-Ethyl-3-methylpyrazine 0.0084 14 3-Ethyl-2,5-dimethylpyrazine 0.9954 15 2-Acetyl-3-methylpyrazine 0.7728 16 Misc. 1-Methyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde 0.9973 17 2-Acetylpyrrole −0.9406 18 1-Furfurylpyrrole −0.9999 19 Acetic acid 0.8548 20 1-Acetoxyacetone −0.9971 21 1-Acetyl-1,4-dihydropyridine −0.4983 22 Maltol −0.9889 23 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol 0.8582 In contrast, a higher level of roasting led to a low furfural content, the compound responsible for sweet aroma. Furfuryl alcohol was prone to dehydration at high temperatures, resulting in furfural formation[18,20]. In addition, roasting promoted esterification between furfuryl alcohol and acetic acid, yielding furfuryl acetate, with fruity, roasted, and sweet odours. Accordingly, the content of acetic acid, which has a sharp vinegar aroma crucial for fruity notes, was reduced with the increasing roasting.

2,6-Dimethyl pyrazine (nutty, roast, cocoa, coffee, and musty odours) was the most abundant pyrazine, followed by methyl pyrazine (nutty, roast, chocolate, and coffee odours). Light roast coffee was high in all of the detected pyrazines except methyl pyrazine. The proportion of methyl pyrazine was relatively high with a high level of roasting because of Strecker degradation of the homologue pyrazines[21,23].

The Millard reaction was escalated with increasing level of roasting. Maltol, with a sweet, caramelized odour, was highest in the dark roast, followed by the medium and light roasts. Acetic acid content was sharply decreased with increasing roasting levels, as was 1-methyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde (sweet, burnt notes), while the contents of 1-acetoxyacetone (fruity, buttery, nutty odours), 2-acetyl pyrrole (walnut, roast odours), and 1-furfuryl pyrrole (waxy, fruity, coffee odours) increased.

-

Arabica coffee cultivated in Thailand is qualified in terms of its phytochemical divergences in addition to its uniqueness accredited by cup scoring. The colour parameter, L* or luminosity, was indicated as the physicochemical character that best correlated with the chemical profiles, i.e., the total phenolic content, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and fatty acid contents. The total phenolic and chlorogenic acid contents were notably high with high L*. A higher level of roasting and a reduction in L* increased the caffeic acid content, the degradation compound of chlorogenic acid. In addition to the nonvolatile compounds exhibiting the coffee's quality, coffee olfactory detectable aroma profiles were specified and changed based on roast level. Furans and pyrazines were determined to be the main volatiles attributed to the coffee's main notes of sweet, roasted, musty, and nutty, followed by additional volatiles co-contributing to fruity and caramelized odours. This present study therefore fills a knowledge gap regarding the chemical profiles of Thai Arabica coffee. This study has a direct significance to the applicability of coffee as a bio-based material with functional properties for innovative nutraceutical products based on the coffee's phytochemical profiles in addition to its conventional supply in the food industry. The economic importance of coffee is dependent on coffee quality. The present data are in alignment with an emerging demand from consumers for high-quality coffee in addition to the cup score.

This research was supported in part by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (Fundamental Fund; Basic Research Fund) for fiscal year 2023 with the grant no. of 662A02043. The reviewers are acknowledged on their valuable suggestions that make the article more comprehensive.

-

Plant access and collection practices complied with national guidelines and legislation, i.e., the Plant variety protection Act (1999) of Thailand, with the correct permits and following good academic practice. Permission for collection was given by the farm owner; Mr. Varis Mantawalee, with consent to harvest and collect the plant samples with the voucher specimens of NLCADCDec22_D, NLCADCDec22_M, and NLCADCDec22_L. The aforementioned voucher specimens were deposited for further reference at the Phytocosmetics and cosmeceuticals research group, Mae Fah Luang University, where access is public and available.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, funding acquisition, investigation, writing-reviewing and editing: Lourith N; investigation, formal analysis, data curation: Kanlayavattanakul M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lourith N, Kanlayavattanakul M. 2025. Quality characteristics of Coffea arabica cultivated in Thailand in response to roasting levels profiling its functional material applications. Beverage Plant Research 5: e022 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0008

Quality characteristics of Coffea arabica cultivated in Thailand in response to roasting levels profiling its functional material applications

- Received: 29 November 2024

- Revised: 11 February 2025

- Accepted: 08 March 2025

- Published online: 04 August 2025

Abstract: Arabica coffee has been cultivated in the northern part of Thailand and is processed for specialty coffee. It is qualified on the basis of sensory metrics. Coffee quality, which indicates its application status for nutraceuticals that are increasing in demand as natural, sustainable, and bioproducts is unclear. Arabica coffee cultivated, harvested, and processed by a local farm was examined. Phytochemical divergences of light, medium, and dark roasts were exhibited. L* (luminosity), indicated that the physicochemical characteristics were in alignment with the chemical profiles. The total phenolic and chlorogenic acid contents were notably high and correlated with L*. A higher roasting level reduced the L* value but increased the caffeic acid content. Coffee olfactory detectable aroma profiles were specified and attributed differently based on roast level. Furans and pyrazines were indicated as the main volatiles attributing the coffee's main notes for sweet, roasted, musty, and nutty, followed by additional volatiles co-contributing to fruity and caramelized odours. This study has direct significance to coffee and its applicability for innovative nutraceutical products based on the coffee phytochemical profiles in addition to its conventional supply in the food industry. The economic importance of the coffee will be achieved. This is seen with the emerging consumer demand for high-quality coffee in addition to a high cup score. Furthermore, the sustainability of coffee cultivated in this area meets the sustainability trend of the current consumer lifestyles.

-

Key words:

- Coffee /

- Quality /

- Volatiles /

- Functional material