-

Tea plants, perennial woody leaf-bearing species, occupy a pivotal position as one of China's key economic crops. Their leaves serve as the fundamental raw material for a diverse range of tea beverages. The prosperous development of the tea industry is intrinsically linked to the livelihoods of millions of tea farmers and contributes significantly to national economic growth[1]. However, during tea plant cultivation, a spectrum of diseases poses substantial threats to both tea leaf yield and quality. Among these diseases, tea gray blight disease ranks as a particularly severe foliar disorder. Tea gray blight disease, widely prevalent in major tea-growing regions including China, India, and Japan, typically causes a 10% to 20% yield reduction in tea plantations when occurring globally[2,3]. It predominantly targets mature leaves, old leaves, and tender shoots of tea plants. In extreme cases, extensive areas of tea plantations experience defoliation, and in some instances, entire tea plants may perish[4]. This disease not only diminishes tea yield but also exerts a profound impact on the sensory quality and biochemical composition of tea leaves due to the damage inflicted on leaf tissues. As a result, it incurs substantial economic losses for the tea industry. The pathogen of tea gray blight disease mainly overwinters in diseased leaves, either in the form of mycelium or conidia, serving as the primary source of infection in subsequent years[5,6]. Under favorable environmental conditions, overwintering pathogens disperse via wind, rain, insects, and other vectors, infecting new tea leaves and precipitating a new cycle of disease. During winter, tea plants enter a dormant phase. To minimize the overwintering population of pests and diseases and facilitate tea plant growth and nutrient accumulation, closed garden management is commonly implemented[6]. Nevertheless, before garden closure, diseased leaves remaining between tea rows after pruning pose a significant risk of triggering tea gray blight disease outbreaks in the following year. Currently, the application of chemical agents such as lime sulfur and Bordeaux mixture represents the most prevalent disease control strategy in tea gardens. However, this approach is beset with issues, including inconsistent control efficacy, pesticide residues, and environmental pollution[7,8].

In recent years, numerous researchers have focused on isolating and screening microorganisms from the tea plantation ecosystem that exhibit antagonistic activities against tea plant pathogens. The tea garden ecosystem harbors a taxonomically and functionally diverse microbial community, which can be broadly categorized into four major guilds based on ecological niches: rhizosphere microorganisms, non-rhizosphere soil microbiota, litter-decomposing microbiomes, and phyllosphere microbiota[9,10]. This microbial assemblage encompasses bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes, along with minor components of archaea and viruses[11]. In contrast to the other three microbial guilds, rhizosphere microorganisms of tea plants establish direct interactions with root systems, forming a specialized microenvironment that profoundly facilitates plant growth and development, underpinned by the extensive soil penetration of tea plant roots[12]. Zhu et al.[13] successfully isolated an antagonistic bacterial strain from the rhizosphere soil of tea plants, which demonstrated an inhibition rate of up to 81% against tea anthracnose. Lu et al.[14] identified seven Trichoderma strains with remarkable inhibitory effects on tea zonate leaf spot. The fermentation broth of one of these strains also effectively inhibited the disease. Li[15] isolated an endophytic strain from tea plant leaves, achieving an 87% inhibition rate against tea zonate leaf spot. These studies underscore the rich diversity of microbial resources within the tea plantation ecosystem, highlighting their substantial potential for development into biocontrol agents. Notably, certain antagonistic strains possess a dual functionality. They not only directly inhibit pathogen growth but also achieve a combined effect of disease prevention and growth promotion through the secretion of plant hormones (such as IAA), production of siderophores, and ACC deaminase activity[16,17]. In recent years, bio-organic fertilizers have mostly focused on using microorganisms with functions such as nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and potassium solubilization as microbial agents[18−20]. It is an innovative and practical method that suits local conditions to use antagonistic bacteria in the soil to suppress a large number of pruned leaves containing gray blight disease pathogens. Ma et al.[21] indicates that the application of specific plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria can enhance both tea plant yield and quality while improving the soil micro-ecological environment. This integrated management approach paves the way for the green control of tea plant diseases.

In the initial phase of this study, we observed a large-scale outbreak of tea gray blight disease in tea plantations. Pathogenic fungi were isolated and purified using the tissue separation method. Through a combination of morphological examination, pathogenicity assessment, and molecular biology techniques, we confirmed that the local leaf disease was caused by the pathogen responsible for tea gray blight disease. At present, the application of biocontrol agents is constrained by several limiting factors, including environmental adaptability, colonization capacity of strains, and stress tolerance[22]. To address these challenges, we initially isolated and screened highly efficient antagonistic strains from the rhizosphere soil of tea plants severely affected by tea brown blight, subsequently evaluating their inhibitory efficacy against the pathogenic bacteria. Moreover, we investigated the growth-promoting traits and stress tolerance of the selected antagonistic strains. This research provides a selection basis, theoretical basis, and valuable microbial resources for the development of multifunctional biocontrol agents tailored for winter tea garden management and microbial agents of bio-organic fertilizers used for applying base fertilizers in autumn.

-

From May to June 2023, diseased leaf samples were collected from tea gardens in Xixiang County, Hanzhong City, Shaanxi Province, China, where tea gray blight disease was highly prevalent. After collection, surface impurities on the samples were carefully removed, and the samples were then placed in sample bags and stored properly for future use. Meanwhile, the Z-shaped sampling method was employed to collect rhizosphere soil of tea plants within the 0−20 cm soil layer in the tea gardens. At each sampling point, 20 g of rhizosphere soil was precisely collected and stored in sampling bags for subsequent experiments.

In this experiment, two-year-old Camellia sinensis 'Shaancha 1' cuttings provided by the Ankang Hanshuiyun Tea Industry Co., Ltd (Shaanxi, China) were used. These cuttings were cultivated in an artificial climate chamber. The environmental parameters in the chamber were set as a day/night temperature of 28/22 °C, a relative humidity maintained at 65%, and a daily light duration of 14 h. The cultivation substrate was a mixture of yellow soil and humus at a ratio of 1:1. Before inoculating pathogens, the third to fourth mature leaves counted from the top of the plants were selected. The leaf surfaces were strictly disinfected with 0.1% carbendazim solution.

The formulations of various media used in this study are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. PDA medium, tryptone, yeast extract, soytone, and agar powder were all purchased from Beijing Solabio Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Other chemical reagents were domestic analytical-grade reagents to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the experiments.

Isolation and purification of pathogenic fungi

-

The collected diseased leaves were brought back to the laboratory, and the tissue isolation method was used to isolate the pathogenic fungi on tea leaves[23]. First, the leaves were gently rinsed with clear water to thoroughly remove attached soil and stones. Then, the leaves were immersed in alcohol for 30 s for surface disinfection. Subsequently, using a sterilized scalpel, 1 mm × 1 mm tissue pieces were precisely cut from the boundary between diseased and healthy tissues and spread evenly on the surface of PDA medium. After that, the medium was placed in an environment at 28 °C, cultured in the dark in an inverted manner for 2−3 d.

Morphological observation and pathogenicity identification of pathogenic fungi

-

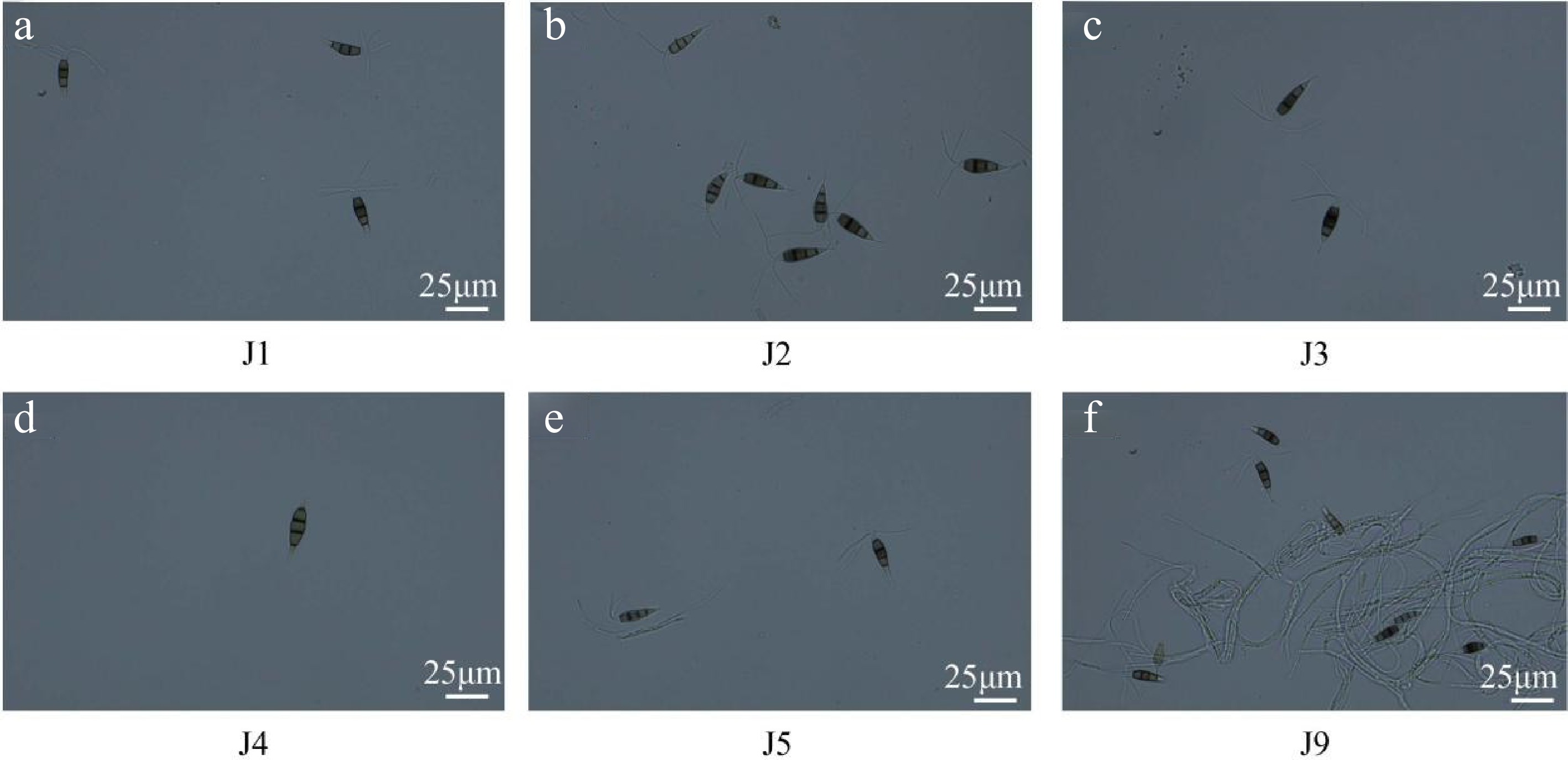

Purified strains were selected and inoculated onto PDA medium for activation. During the cultivation process, the growth trend, morphological characteristics, hyphal richness, and pigment secretion characteristics of the colonies were closely observed. Meanwhile, the activated colonies were placed under light conditions to induce sporulation, and the sporulation characteristics of the strains were observed and recorded in detail. Pathogens J1−J5 and J9 were cultured on PDA medium at 28 °C in the dark. After 5 d, the colonies covered 90 mm Petri dishes. Subsequently, they were exposed to light for 4 d, during which black, oily droplets appeared on the surface of the white, cotton-like colonies. These droplets were collected, diluted with ddH2O, and examined under a microscope. The morphology of conidia was observed and recorded using an Olympus microscope (Olympus, BX51)[24]. The ten successfully isolated pathogenic fungi were named J1−J10 in sequence. Based on Koch's postulates, an indoor detached leaf reinoculation test was carried out on the isolated pathogenic fungi. Using a 6 mm hole puncher, fungal discs were made from the pathogenic colonies, and three fungal discs were evenly inoculated onto each detached tea leaf. Blank agar discs were set as controls[25].

Molecular biological identification of pathogenic fungi

-

DNA of pathogenic fungi was extracted strictly according to the operation instructions of the Omega Fungal Genomic DNA Extraction Kit. The extracted DNA was amplified using primers ITS1 (5'-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3') and ITS4 (5'-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3'). The amplified products were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis. The qualified products were then sent to Beijing TsingKe Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for sequencing. The sequences obtained through comparison and analysis in the GenBank database were used to infer the evolutionary history with MEGA X software. Employing the Neighbor-Joining method, it was based on 20 nucleotide sequences. The evolutionary distances were calculated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method. Bootstrap analysis was carried out using the p-distance. After 1,000 bootstrap replicates, the phylogenetic tree was drawn to scale to clarify the classification of pathogenic fungi.

Isolation and screening of antagonistic bacteria

-

Ten grams of soil samples were accurately weighed and added to a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 90 mL of sterile water, and an appropriate amount of glass beads. The Erlenmeyer flask was placed on a shaker and shaken for 10 min to disperse the soil thoroughly, and then left to stand. After the soil particles settled, 1 mL of the supernatant was taken and serially diluted by a factor of 10, obtaining soil suspensions with concentrations of 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, and 10−6. Referring to the methods of Liao et al.[26] and Yang et al.[16], 0.1 mL of the above suspensions was taken and evenly spread on PDA plates using the streak plate method. Three replicate plates were set for each concentration. The plates were placed in a 28 °C constant temperature incubator, cultured in an inverted manner, and the cultivation situation was observed regularly. When colonies appeared on the plates, colonies with different morphologies were selected for isolation and purification and stored properly for subsequent research. The standard for screening antagonistic bacteria is that they can inhibit any one or more than two of the five pathogens (J1−J5) causing tea gray blight.

Molecular biological identification of antagonistic bacteria

-

The plate confrontation method was used to detect the inhibitory effects of the screened strains on pathogenic fungi, and strains with significant inhibitory effects were determined. The pathogenic fungus causing tea gray blight was inoculated in the center of a PDA plate, and antagonistic bacteria were inoculated equidistantly around the edge. The plates were then incubated in a constant-temperature incubator at 28 °C. When the colonies in the control group had grown nearly to the edge of the Petri dish, the diameters of the colonies were measured to calculate the inhibition rate using the formula: Inhibition rate = [(Colony diameter of the pathogenic fungus in the control group − Colony diameter in the treatment group)/Colony diameter of the pathogenic fungus in the control group] × 100%. When conducting molecular identification of these strains, 16S rDNA sequence analysis technology was adopted. The specific operation was as follows: Using an inoculating loop, colonies growing well on PDA medium (cultured at 28 °C for 5 d) were scraped off and transferred to a 1.5 mL EP tube. After adding an appropriate amount of TE buffer, the colonies were thoroughly mixed by vortexing. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in TE buffer. Bacterial DNA was extracted according to the operation process of the Omega Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit. Based on the sequence characteristics of the conserved regions of 16S rDNA, universal primers were designed. The forward primer 27F was (5'-CAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCT-3'), and the reverse primer 1492R was (5'-AGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA-3')[27]. The primers were synthesized by TsingKe Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The sequences obtained through comparison and analysis in the GenBank database were used to infer the evolutionary history with MEGA X software. Employing the Neighbor-Joining method, it was based on 38 nucleotide sequences. The evolutionary distances were calculated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method. Bootstrap analysis was carried out using the p-distance. After 1,000 bootstrap replicates, the phylogenetic tree was drawn to scale to clarify the classification of antagonistic bacteria.

Determination of IAA secreted by antagonistic bacteria

-

Colonies of antagonistic bacteria with good growth conditions were picked by the streak method and inoculated into 600 μL of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. The medium was shaken and cultured at 28 °C for 12 h to obtain sufficient bacterial liquid. Subsequently, 50 μL of the bacterial liquid was added to LB media containing 20, 60, and 100 μg/mL tryptophan, respectively. The cultures were continuously shaken and cultured within the temperature range of 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h. After cultivation, 5 mL of the bacterial liquid was centrifuged at 9,000 g for 15 min. Two milliliters of the supernatant was taken and added to 2 mL of Salkowsky reagent (prepared by dissolving 2% 0.5 M FeCl3 in 35% perchloric acid). The mixture was incubated in the dark for 30 min[28]. Standard curves were drawn using different concentrations of IAA standards (25, 50, 75, 100, 150 μg/mL). The concentration of IAA in the bacterial liquid was calculated based on the standard curves. Each sample was measured three times to ensure the accuracy of the data.

Determination of siderophore content in antagonistic bacteria

-

Referencing Wang's method[17], inoculate antagonistic bacteria into MKB medium, shake cultivate at 30 °C, 150 rpm for 2 d. Centrifuge 4 mL of culture liquid at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, take 2 mL of supernatant, add 2 mL CAS detection solution, invert and mix evenly, then let it stand for 1 h, measure the absorbance at OD630, denoted as As. Repeat each treatment three times, measure the absorbance of the un-inoculated MKB medium as a control, denoted as Ar. Determine the relative content of siderophores by As/Ar. The smaller the ratio, the greater the siderophore production. Generally, the reference standard is: As/Ar < 0.2, +++++; 0.2 ≤ As/Ar < 0.4, ++++; 0.4 ≤ As/Ar < 0.6, +++; 0.6 ≤ As/Ar <0.8, ++; 0.8 ≤ As/Ar <1.0, +.

Determination of ACC deaminase activity in antagonistic bacteria

-

Referring to the method of Wang & Han[29], antagonistic bacterial strains were inoculated into 60 mL of TSB medium and cultured at 30 °C for 24 h. After cultivation, the culture was centrifuged at 8,000 r/min for 10 min. The bacterial pellet was washed twice with DF medium and then resuspended in 24 mL of ADF medium for further cultivation for 24 h. The bacteria were collected by centrifugation, washed with 0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6), and resuspended in 600 mL of 0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5). Thirty milliliters of toluene was added to the resuspended solution and shaken for 30 s to break the cells. Subsequently, the protein concentration and ACC deaminase activity of the crude enzyme solution were determined. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method, and a standard curve was drawn using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Study on the salt tolerance of antagonistic bacteria

-

Referring to and optimizing the experimental method of Wang[17], the activated antagonistic bacterial liquid was transferred to LB media with different final NaCl concentrations (0%, 1%, 2%, 5%, 7%, and 10%). The media were placed on a shaker and shaken, and cultured at 30 °C and 150 rpm. The absorbance values at OD600 of the bacterial liquid were measured at 2, 4, 8, 12, 20, and 28 h to characterize the growth of the bacteria. Three replicates were set for each treatment.

Study on the drought tolerance of antagonistic bacteria

-

The water potential of the medium was adjusted by adding PEG6000 to simulate a drought environment. The concentrations of PEG6000 were set at 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%, with corresponding water potentials of 0, −0.185, −0.559, and −1.122 MPa, respectively. The activated bacterial liquid was transferred to LB media containing the above four different concentrations of PEG6000, shaken and cultured at 30 °C and 150 rpm. The absorbance values at OD600 of the bacterial liquid were measured at 2, 4, 8, 12, 20, and 28 h to characterize the growth of the bacteria under different drought conditions. Three replicates were set for each treatment.

-

During May to June 2023, large-scale red spotted tea leaves emerged in the tea plantation. Red leaf spots were predominantly concentrated on older leaves, spreading inward from the leaf tips. They featured concentric ring patterns, irregular shapes and edges, and a shriveled, reddish brown appearance. Diseased parts were dried, brittle, and hard, with a distinct pale yellow boundary at the diseased healthy interface (Fig. 1a). Pathogens were isolated from diseased leaves using the tissue separation method. Ten pathogenic strains, designated as J1−J10, were obtained (Fig. 1b). All ten strains exhibited obvious concentric rings, yet with varying ring spacings. J1, J2, J3, and J9 had wider ring spacings; J6, J7, and J10 had intermediate spacings; J8 had the densest rings; and J4 and J5 showed no distinct ring distribution. Colonies of J1−J9 were white, cotton-like on the front with uneven edges, while J10's colony was green, cotton-like on the front. The backsides of J3 and J8 colonies were light pink; the center backside of J10's colony was brown green; and the remaining seven strains had light yellow backside colonies. Pathogenicity tests on detached tea leaves revealed that J1−J5 and J9 successfully re-infected, while tea leaves inoculated with J6, J7, J8, and J10 were indistinguishable from the blank control (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Morphological characteristics of pathogens. (a) Typical symptoms on naturally infected leaves. (b) Colony morphology (front and reverse) of isolated strains. (c) Disease development on detached leaves after inoculation (CK: control).

Observation of conidia morphology of tea gray blight pathogens

-

At 40× magnification, the conidia were spindle to rod-shaped, with some slightly curved (e.g., J2 spores). They measured 25−30 μm in length and 6−9 μm in width. The conidia consisted of five cells: the middle septum was black, the terminal cells were transparent, and the middle three cells were brown, with the color fading from the head to the tail. Except for J4, strains J1−J3, J5, and J9 had 2–3 transparent appendages (5–8 μm in length) at the apex and one appendage (3–5 μm in length) at the base. J4 spores lacked appendages but had thickened cell walls at both ends (Fig. 2d). Based on colony and conidial morphology, the strains were preliminarily identified as belonging to the genus Pestalotiopsis.

Identification of tea gray blight disease pathogens

-

To clarify the taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships of tea garden pathogens, molecular biological identification and analysis were performed on the isolated strains. Genomic DNA was extracted from the target pathogenic strains and amplified using ITS-specific sequences. Effective amplification bands were detected in strains J1−J5, while no bands were observed in J9. After purification and sequencing, the products were subjected to BLAST searches in the NCBI GenBank database. Molecular identification results indicated (Supplementary Table S2): Strain J1 was identified as Neopestalotiopsis piceana with 100% sequence homology to accession OQ165191.1; J2 as Pestalotiopsis microspora (99.81% homology to KT459350.1); J3 as Pseudopestalotiopsis theae (100% homology to PP727534.1); J4 as Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis (99.82% homology to OQ165168.1); and J5 as Pseudopestalotiopsis chinensis (100% homology to MT322063.1), preliminarily confirming their taxonomic affiliations. The specific sequences obtained from BLAST were in Supplementary File 1. A phylogenetic tree was constructed to visualize the genetic relationships among the strains (Fig. 3a): J1 clustered with Neopestalotiopsis piceana (OQ165191.1) with bootstrap support values reflecting branch reliability; J2 grouped with Pestalotiopsis microspora (KT459350.1) and showed a closer phylogenetic relationship to J3; J4 and J5 clustered with multiple known sequences of the Pseudopestalotiopsis genus (e.g., PP727534.1), demonstrating their phylogenetic association. Colony morphology observations revealed similarities between J2 and J3 in colony characteristics, as well as between J4 and J5, which aligned with the clustering patterns in the phylogenetic tree, further corroborating the genetic relationships among the strains (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

The phylogenetic and phenotypic characterization of pathogen strains causing tea gray blight disease. (a) Phylogenetic tree of pathogen strains and reference strains. Tree scale = 0.050 represents genetic distance. (b) Colony morphology observation of pathogen strains.

Screening of antagonistic bacteria against tea gray blight disease

-

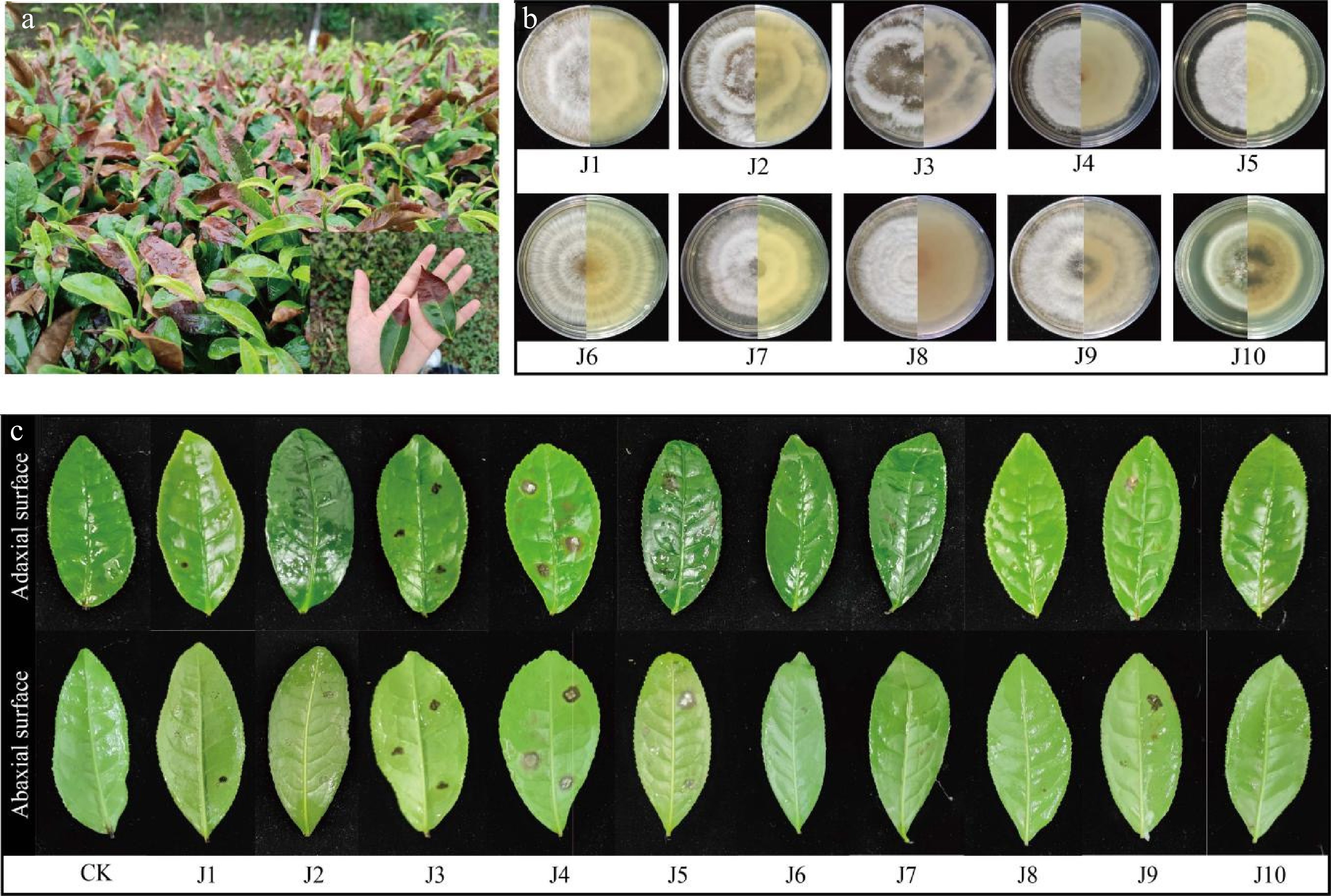

Tea rhizosphere soils were collected from severely diseased tea plantations. Eight strains with significant antagonistic effects against pathogens, namely X2, X6, X8, X10, X11, X14, X17-B, and X21, were screened out. Plate confrontation assays showed that these eight strains inhibited the growth of J1−J5 to varying degrees. The growth rates of inhibited pathogens were significantly lower than those of the control group (Fig. 4a). Statistical analysis of plate confrontation experiments revealed that these eight strains inhibited J1, J2, and J4. X21 promoted the growth of J3 and J5; X2 and X6 promoted the growth of J5. X10, X11, X14, and X17-B exhibited remarkable inhibitory effects on J1−J5 (Fig. 4b). The inhibition rates of X10 against J1−J5 were 35.57%, 37.42%, 33.86%, 22.19%, and 18.12%, respectively; those of X11 were 30.43%, 34.84%, 31.50%, 24.38%, and 28.99%; those of X14 were 23.48%, 23.87%, 29.92%, 14.88%, and 22.46%; and those of X17-B were 28.19%, 33.55%, 36.22%, 13.92%, and 37.68% (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 4.

Antagonistic effect of biocontrol strain with pathogen of gray blight disease. (a) Dual culture test on antagonistic bacteria against the tea gray blight disease pathogen. CK: Five pathogen normal culture on 6 mm PDA medium were used as controls. Scale bar = 1 cm. (b) Width change of pathogens under conditions of antagonistic culture. The data represent the average ± SD of biological repeats, different letters indicate significantly differences between means as determined according to ANOVA followed by Duncan's tests (p < 0.05)

Identification of antagonistic bacteria against tea gray blight disease

-

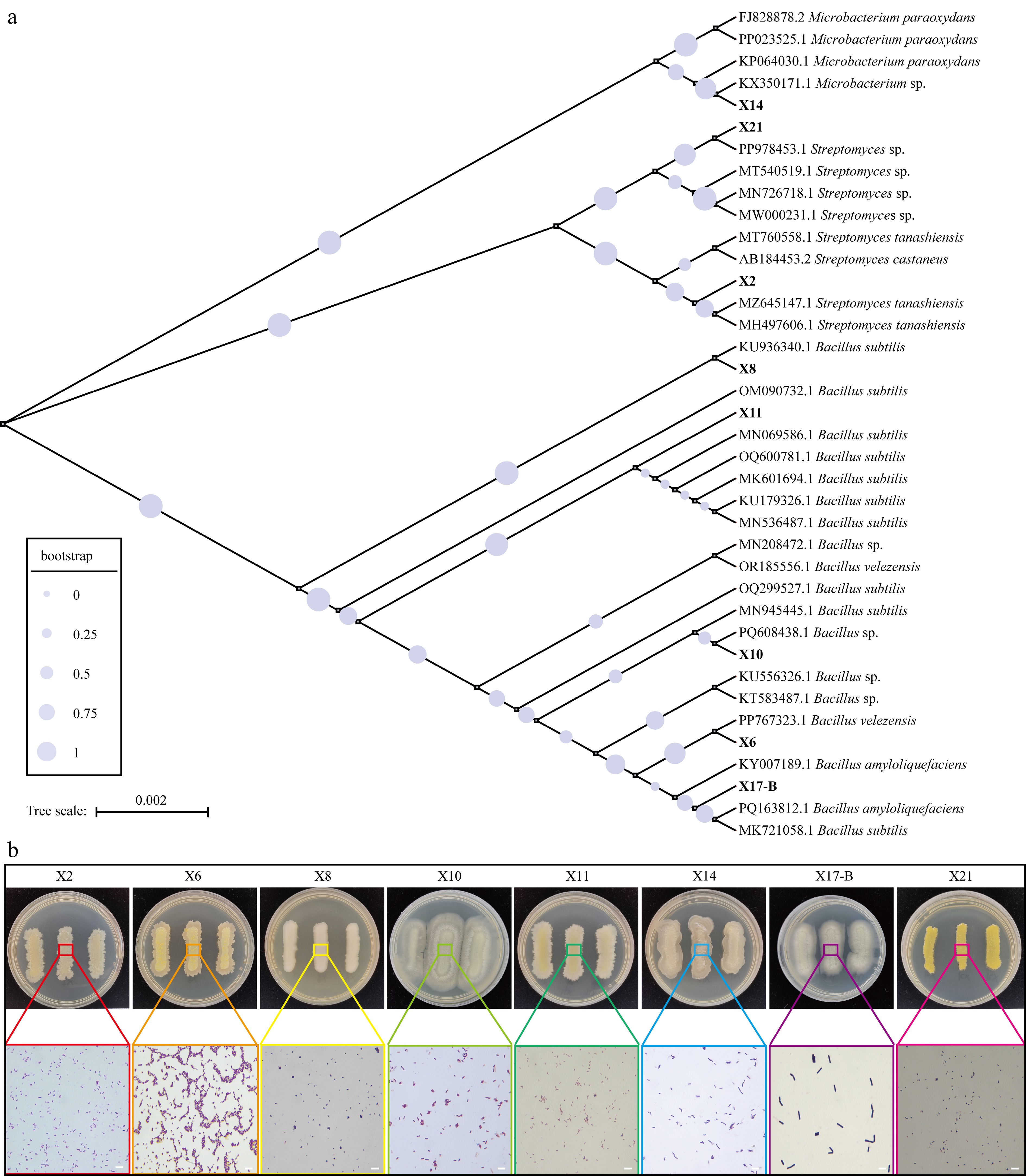

The antagonistic bacteria X2, X6, X8, X10, X11, X14, X17-B, and X21 were cultured on PDA medium. Colonies of X2 were small, compact, dry, and non-transparent, with a smooth surface when young, an irregular edge, and a light yellow color. As they developed, the surface became wrinkled and powdery, and Gram-staining results were positive. X6 colonies were smooth, sticky, and goose yellow when young, gradually coalescing into patches with irregular edges and turning pale pink as they developed, with positive Gram-staining results. X8 colonies had a smooth, non-transparent, sticky surface, appearing dirty white, with positive Gram-staining results. X10 colonies had a rough, non-transparent surface, were dirty white when young, and became powdery as they developed, with positive Gram-staining results. X11 colonies had a rough, non-transparent surface, were light yellow, and became powdery as they developed, with positive Gram-staining results. X14 colonies were moist, transparent, light yellow, turning white, shriveled, with irregular edges, and had positive Gram-staining results. X17-B colonies had a rough, non-transparent surface and appeared milky white, with positive Gram-staining results. X21 colonies were small, compact, moist, non-transparent, golden yellow, and had positive Gram-staining results (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

The phylogenetic and phenotypic analysis of biocontrol strains. (a) Phylogenetic tree of biocontrol strains and reference strains. The size of circles at nodes represents bootstrap values (0–1, with larger values indicating higher branch reliability, see the bootstrap legend). Tree scale = 0.002 represents genetic distance. (b) Colony morphology and Gram staining microscopic observation of biocontrol strains. The upper part shows the colony phenotypes of the strains on PDA medium (the numbers of the Petri dishes correspond to the strains: X2, X6, X8, X10, X11, X14, X17-B, X21), and the colored boxes mark the local areas of the colonies; the lower part shows the Gram staining microscopic images of the corresponding areas (magnification: 100 ×, scale = 1 μm), demonstrating the bacterial cell morphology and staining characteristics.

Through primer amplification, 16S rDNA sequences of the eight strains were obtained and subjected to BLAST homology comparison (Supplementary Table S4). Strain X2 showed highest identity with Streptomyces castaneus (accession number AB184453.2), X6 with Bacillus velezensis (accession number PP767323.1), X8 with B. subtilis (accession number KU936340.1), X10 with B. subtilis (accession number MN945445.1), X11 with B. subtilis (accession number MN069586.1), X14 with Microbacterium sp. (accession number KX350171.1), X17-B with B. amyloliquefaciens (accession number PQ163812.1), and X21 with Streptomyces sp. (accession number PP978453.1) (Fig. 5).

Analysis of growth-promoting characteristics of antagonistic bacteria

-

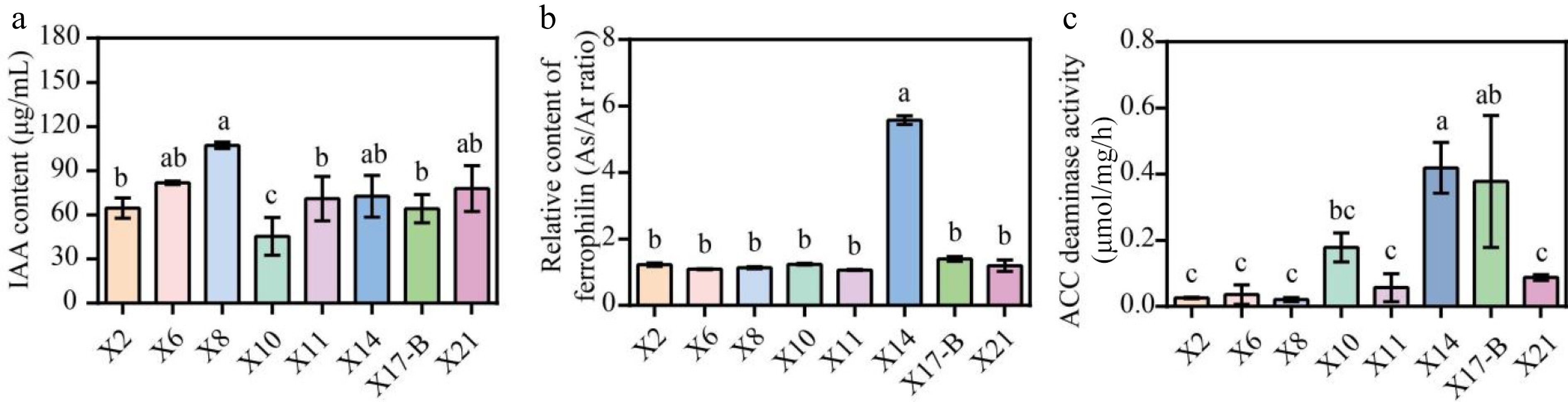

All eight strains demonstrated the ability to produce IAA. Strain X8 had the highest IAA production, reaching 107.2 μg/mL. X6, X14, and X21 had secondary IAA yields of 81.9 μg/mL, 72.6 μg/mL, and 77.8 μg/mL, respectively. X2, X10, X11, and X17-B had relatively lower IAA yields of 64.6 μg/mL, 45.4 μg/mL, 71.0 μg/mL, and 64.1 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 6a). In the siderophore secretion experiment, all eight strains had As/Ar values greater than 1, indicating no siderophore secretion ability (Fig. 6b). All strains possessed ACC deaminase activity. X14 exhibited the highest ACC deaminase activity, reaching 0.42 μmol/mg/h, followed by X17-B and X10 (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6.

Growth-promoting characteristics of biocontrol strains. (a) IAA produced by the isolated antagonistic strains. (b) Siderophores production by the antagonistic strain isolates. (c) Determination of ACC deaminase activity of antagonistic strains. The data represent the average ± SD of biological repeats. Different letters indicate significantly differences between means as determined according to ANOVA followed by Duncan's tests (p < 0.05)

Study on the growth characteristics of antagonistic bacteria under adverse conditions

-

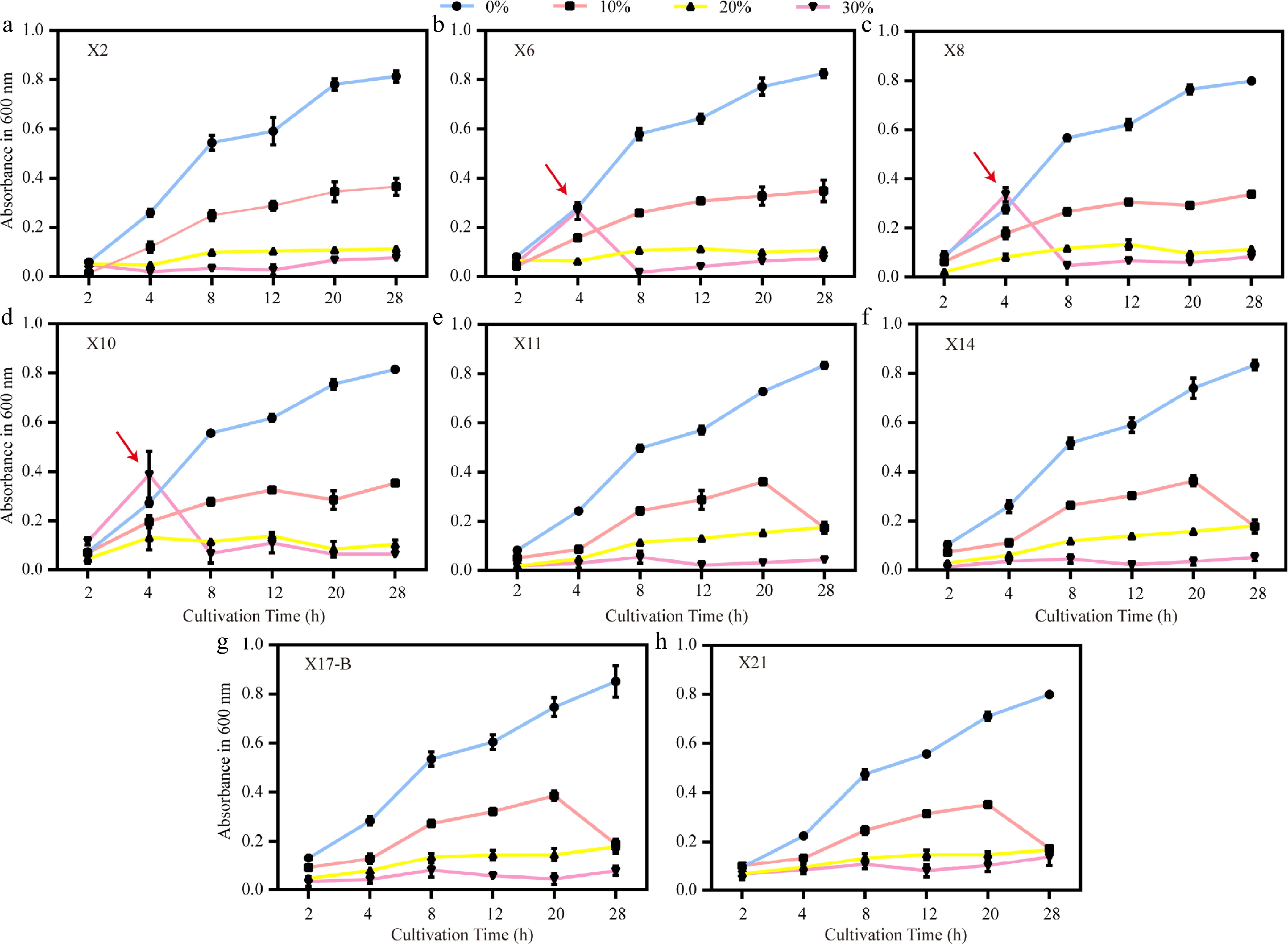

To investigate the adaptability of antagonistic bacteria under drought stress, PEG6000 was used to simulate artificial drought conditions. Under the same cultivation time, the growth rate of strains generally decreased with the increase in PEG6000 concentration. At 0% concentration, all strains exhibited the highest growth rate, which continuously increased over time. The OD600 value reached 0.7987−0.8514 at 28 h, with X17-B showing the best performance. At 10% concentration, the growth rate was lower than that in the 0% group. Most strains increased steadily over time, while the growth rates of X11, X14, X17-B, and X21 dropped sharply after 20 h. The inhibitory effect was more significant at 20% concentration, resulting in an overall low growth rate, among which X11 and X14 showed relatively stable and slightly higher growth performance. At 30% concentration, the growth index was the lowest. However, X21 maintained a relatively high growth rate (OD600 = 0.14 ± 0.04) even at 30% PEG, outperforming other strains. Notably, at 30% PEG6000, X6, X8, and X10 showed a brief growth acceleration between 2 and 4 h (up to a 40% increase), potentially related to stress response mechanisms. Under the same concentration, there were significant differences in the growth rates among different strains, and the growth of most strains was limited under stress concentrations, with some strains showing a decrease in activity in the later stage due to long-term stress (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Growth trends of biocontrol strains under different PEG6000 concentrations. (a)–(h) Growth curves (OD600) of strains X2, X6, X8, X10, X11, X14, X17-B, and X21 under drought stress simulated by 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% PEG6000. Red arrows indicate abrupt growth rate changes of X6, X8, and X10 at 4 h under 30% PEG. Error bars represent standard deviations of triplicates (n = 3).

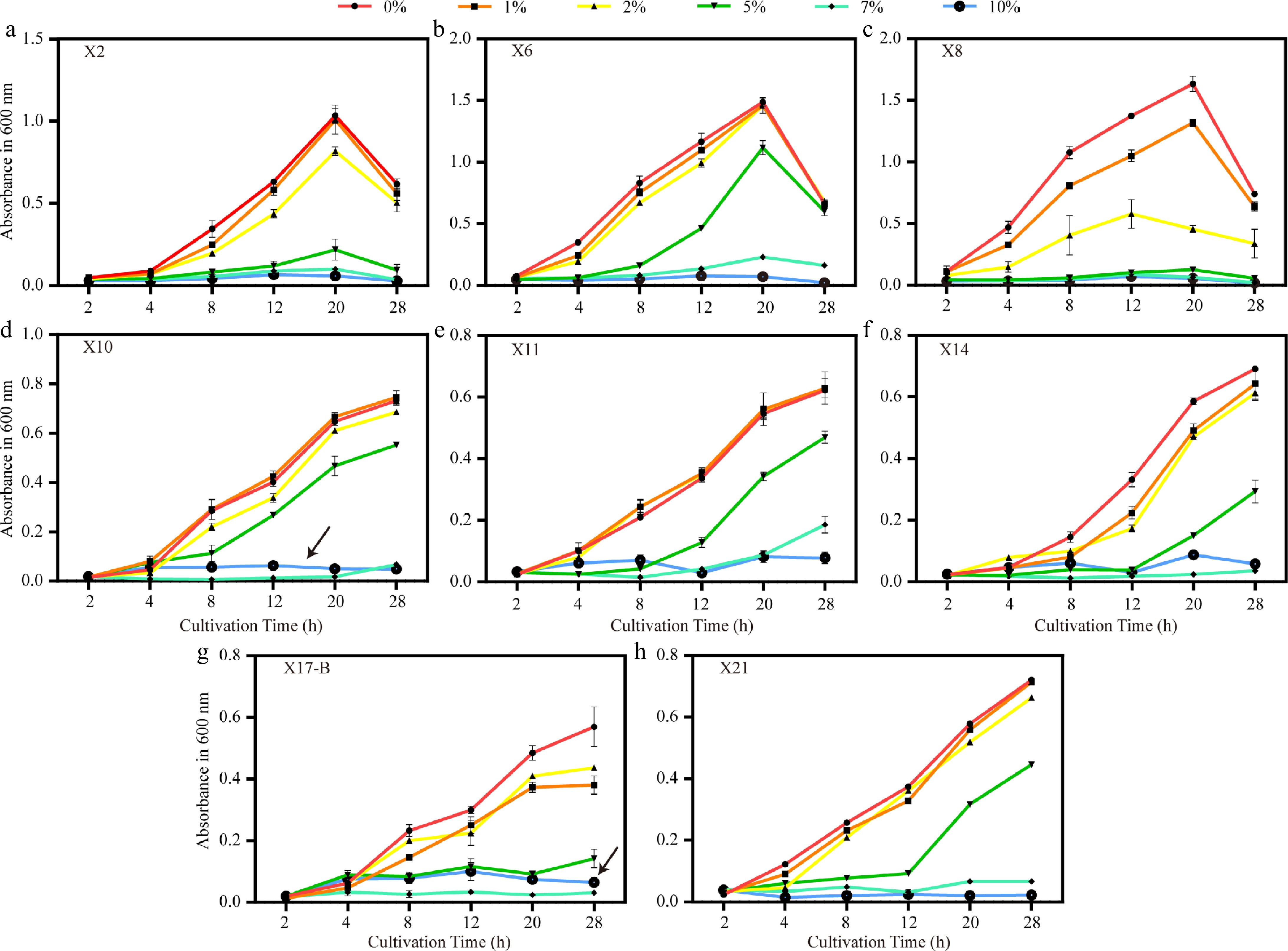

To evaluate the adaptability of antagonistic bacteria to salt stress, an experiment was conducted by adding NaCl at concentrations of 0%, 1%, 2%, 5%, 7%, and 10% to LB medium to simulate salt stress environments. The results showed that within the same cultivation time, the growth rate of most strains gradually decreased as the NaCl concentration increased, and the inhibitory effect was enhanced with the increase of concentration. Under the 1% and 2% NaCl treatments, the growth trends of the remaining six strains were not significantly different from that of the control, except for X8 and X17-B. However, when the concentration was ≥ 5%, the growth of X2 and X8 was severely inhibited, while X10 and X17-B showed excellent salt tolerance. Their growth under the 10% NaCl treatment was even better than that under the 7% treatment, which might be attributed to the differential expression of osmotic adjustment genes. The inhibitory effect of 10% NaCl was the most significant; at most time points, the growth rates of all strains at this concentration remained extremely low, mostly below 0.08. In contrast, 0% NaCl had a relatively strong promoting effect on the growth of all strains.

In terms of temporal dynamics, the growth rate of most strains peaked at around 20 h and then generally decreased at around 28 h. This downward trend was more obvious under high salt concentrations (such as 7% and 10%), which is speculated to be related to the decrease in bacterial activity caused by long-term high-salt stress. There were significant differences in the salt tolerance of different strains: X8 showed a significant growth advantage under low salt concentrations (0% and 1%). At 20 h under 0% NaCl treatment, its growth rate was 1.63, which was the highest among all strains and all time points. However, with the increase of salt concentration, its growth decreased sharply and was severely inhibited at concentrations of 5% and above. X6 and X10 had good adaptability to medium-high salt concentrations (2%–5%). The growth rate of X6 at 20 h under 2% NaCl treatment was 1.46, which was comparable to that under 1% treatment. The growth rate of X10 at 20 h under 5% NaCl treatment was 0.47, and it reached 0.73 at 28 h under 0% NaCl treatment, making it the fastest-growing strain at that time. The growth of X2 gradually decreased with the increase in salt concentration. X11 maintained relatively stable growth under 0%, 1%, and 2% NaCl treatments, and even at 28 h, it still maintained a certain level. The growth of X14 decreased significantly with the increase of salt concentration. X17-B grew moderately under low salt concentrations but was severely inhibited under high salt concentrations. The growth rate of X21 was relatively stable at all concentrations, but the overall level was low, and it was significantly inhibited under high salt concentrations.

In conclusion, both NaCl concentration and cultivation time had significant effects on the growth rates of the eight strains, and there were significant differences in the adaptability of different strains to salt stress (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Growth trends of biocontrol strains under different NaCl concentrations. (a)–(h) Growth curves (OD600) of strains X2, X6, X8, X10, X11, X14, X17-B, and X21 under salt stress with 0%, 1%, 2%, 5%, 7%, and 10% NaCl. Black arrows indicate the atypical growth recovery of X10 and X17-B at 10% NaCl. Error bars represent standard deviations of triplicates (n = 3).

-

Tea gray blight, a severe foliar disease of tea plants, is predominantly caused by infection with fungi belonging to the Pestalotiopsis genus. Five pathogenic strains (J1−J5) were isolated from diseased leaves in a tea plantation in Xixiang County, Shaanxi Province, China, using the tissue separation method. Through morphological observations and molecular biological identification, these strains were determined to belong to the genera Pestalotiopsis, Neopestalotiopsis, and Pseudopestalotiopsis. Notably, the conidial characteristics of strain J4 deviate from those of typical Pseudopestalotiopsis theae. J4 features thickened cell walls at both ends and lacks appendages (Fig. 2d), indicating possible regional adaptive variation. This differs from the Pseudopestalotiopsis theae identified in Hunan (China) by Yang et al.[16], which possess prominent apical appendages. The divergence can likely be ascribed to a combination of two influential factors. The Shaanxi tea growing region features unique climatic conditions, marked by a relatively low annual average temperature and substantial diurnal temperature variations. These conditions prompt morphological adaptation in pathogens. Additionally, long-term chemical pesticide usage has exerted selective pressure on the pathogen population. Pathogenicity tests demonstrated that J4 and J5 are highly pathogenic, with a lesion expansion rate of 1.5 mm/d. This finding aligns with the pathogenic traits of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora previously reported by Chen et al.[30]. Notably, in this study, the lesions generated by J3 on detached tea leaves present distinct concentric ring patterns (Fig. 1c). This discovery provides novel morphological criteria for the early diagnosis of tea leaf blight, enhancing our understanding of the disease and potentially improving diagnostic accuracy in the field.

In the tea garden ecosystem, microorganisms function as decomposers, mediating the breakdown of senescent tea leaves infected with leaf spot pathogens. This study employed a soil sampling depth of 0–20 cm for two key rationales: first, to broaden the screening spectrum for antagonistic bacteria against tea gray blight pathogens and ensure the capture of rhizosphere microorganisms directly engaged in root-microbe interactions; second, this depth interval adheres to the standardized protocols for rhizosphere research across most plant species, enabling horizontal comparability with findings from other taxa[31]. Notably, the 0–10 cm humus layer-being the principal locus of litter decomposition-may obfuscate the community signatures of rhizosphere antagonistic bacteria, potentially resulting in the misclassification of saprophytic fungi as rhizosphere-functional microbes. During the screening of antagonistic bacteria, X10 (B. subtilis) and X17-B (B. amyloliquefaciens) demonstrated remarkable inhibitory effects, with inhibition rates exceeding 33.86% against J1−J3. Their inhibitory mechanisms likely vary. Previous research has shown that Bacillus sp. secretes proteases, amylases, lipases, and lipopeptide antibiotics, which can directly disrupt the fungal cell membrane and impede fungal growth[32,33]. Thus, X10 may inhibit the growth of Pestalotiopsis fungi through the secretion of these substances. Chitin, a major component of the Pestalotiopsis fungal cell wall, accounting for approximately 15%−30% of its dry weight, can be degraded by chitinase[34,35]. Previous studies have purified chitinase from Streptomyces sp. and found that it can degrade the fungal cell wall, thereby inhibiting fungal growth[36,37]. Therefore, it is hypothesized that X2 may secrete chitinase to degrade the fungal cell wall, though further research is needed for confirmation. Notably, X14 (Microbacterium sp.) exhibited moderate direct inhibitory effects, with inhibition rates ranging from 14.88% to 29.92%. However, its ACC dehydrogenase activity, measured at 0.42 μmol/(mg·h), is significantly higher than that reported by Ma et al.[21] for similar strains. This suggests that X14 may enhance systemic resistance in tea plants by regulating ethylene synthesis. The 'direct inhibition and induced resistance' synergistic effect is particularly pronounced in X8 (B. subtilis). X8 simultaneously exhibits high IAA production (107.2 μg/mL) and substantial inhibition rates against certain pathogens (e.g., 23.7% against J2 and 24.41% against J3), in line with Wei's[38] theory of 'growth-promoting biocontrol dual-function bacteria'. Conversely, X2, X6, and X21 (Streptomyces sp.) promoted the growth of some pathogens (e.g., J5), contradicting the findings of Zhu et al.[13]. This may be due to growth hormones secreted by these strains altering the metabolic pathways of pathogens, a hypothesis that requires validation through transcriptome analysis. Notably, validation of siderophore biosynthesis capacity in eight selected biocontrol strains via Chrome Azurol S assays revealed As/Ar ratios > 1 for all isolates, indicative of absent siderophore production. The southern Shaanxi tea region, situated south of the Qinling Mountains and north of the Daba Mountains, exhibits a warm-humid climate[39]. Tea gardens in Hanzhong City are predominantly characterized by iron-rich yellow-brown soils. Given the high metabolic costs associated with siderophore synthesis-requiring substantial energy and precursor molecules, strains may employ metabolic trade-off strategies in iron-sufficient or low-competition environments to prioritize expression of alternative biocontrol determinants, such as antimicrobial peptides and cell wall-degrading enzymes, over sustaining siderophore biosynthesis pathways[40]. Experimental validation of this hypothesis through multi-omics approaches is warranted to establish mechanistic clarity. This study revealed significant variations in the responses of different antagonistic bacteria to environmental stresses (Figs 7 & 8). In terms of drought resistance, X21 (Streptomyces sp.) could sustain growth under simulated drought conditions with 30% PEG6000 (OD600 = 0.14 ± 0.04). Previous research has indicated that Streptomycetes exhibit high drought resistance, potentially related to their ability to promote intracellular trehalose accumulation and biofilm formation under drought stress. This makes them well suited for drought-prone tea growing regions such as Shaanxi[41−43]. In the salt resistance test, the unusual growth patterns of X10 and X17-B under 10% NaCl conditions are particularly notable (Fig. 8d, g). Both strains grew poorly at 7% NaCl (OD600 = 0.018 and 0.033), but recovered at 10% NaCl (OD600 = 0.063 and 0.10). It is hypothesized that these two strains may activate K+ absorption systems and secrete compatible solutes (e.g., proline) to maintain osmotic balance under high salt stress[44,45]. This finding provides new evidence for Wang's 'stress adaptation biphasic response' theory[17]. However, translating laboratory findings into field applications remains challenging, given factors such as changes in strain performance under combined stresses and rejection by the soil microbial community in tea plantations. In typical tea gardens, soil salinity generally rarely exceeds 0.5%. Nevertheless, this study still employs extreme salt concentration testing. Its core value lies in deciphering the mechanisms of action under extreme conditions to provide scientific support for risk prevention and control as well as sustainable management in normal production. Especially against the backdrop of climate change, such research holds significant strategic importance for safeguarding the ecological security of tea gardens and the stability of the tea industry.

In conclusion, this study not only enriches the resource library of pathogenic bacteria of tea plant diseases, but also screens out multiple strains of antagonistic bacteria with both biocontrol and growth-promoting functions. Their special stress resistance characteristics lay a foundation for the development of microbial agents suitable for tea gardens under adverse conditions. However, there are still challenges in translating laboratory results into field applications. The performance of strains may change under combined stresses (such as drought + high salinity), and the soil microbial community in tea gardens may reject the introduced bacteria. Subsequent research should focus on solving the problem of connecting laboratory research with field applications, and promote the practical application of biocontrol technology in the safe production of tea. In the future, it is planned to analyze the specific antibacterial components of X10 and X17-B through LC-MS metabolomics analysis, and conduct pot experiments under simulated low-temperature conditions in winter to evaluate the effects of antagonistic bacteria as biocontrol agents for closing tea gardens, as well as their growth-promoting and antibacterial effects as microbial agents of bio-organic fertilizers.

-

This study focuses on the large-scale outbreak of tea gray blight disease in tea plantations in Xixiang County, Hanzhong City, Shaanxi Province, China. Through tissue isolation, pathogenic fungi were successfully isolated and identified from diseased tea leaves. During the experiment, a total of 10 potential pathogenic strains (J1–J10) were obtained. By means of morphological observation, pathogenicity testing, and molecular biological analysis, the major pathogenic fungi were determined to belong to the genera Pestalotiopsis, Neopestalotiopsis, and Pseudopestalotiopsis. Simultaneously, researchers screened out eight bacteria with significant antagonistic effects from the rhizosphere soil of severely infected tea plants. Through 16S rDNA sequence analysis, these bacteria were identified as Streptomyces, Bacillus, etc. Among them, X10, X11, X14, and X17-B exhibited particularly prominent inhibitory effects against five pathogenic strains. Notably, all antagonistic bacteria possess the ability to produce IAA. The IAA production of strain X8 reached as high as 107.2 μg/mL. The study also delved deeply into the growth characteristics of antagonistic bacteria under salt stress and drought conditions. The results demonstrated that X10 and X17-B possess high salt tolerance. Even under high-concentration PEG6000 simulated drought conditions, X21 could still maintain a certain growth capacity. This study provides a solid theoretical basis for the closed season management of tea plantations in winter and enriches the microbial resource library. The research reveals that antagonistic bacteria can not only inhibit pathogenic bacteria but also have the potential to promote plant growth, laying the foundation for the development of multifunctional biocontrol agents. The application of antagonistic bacteria for biocontrol can not only effectively reduce the use of chemical pesticides and improve the soil micro-ecological environment, but also contribute to the popularization of green prevention and control technologies in tea plantations. The research findings further indicate that biocontrol using antagonistic bacteria represents one of the effective approaches in controlling tea gray blight disease.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.32172635) and the Key Research and Development Project of the Tibetan Autonomous Region Department of Science and Technology (XZ202401ZY0019).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gong C, Zhang Q, Li J, Tang L, Ren J; experiments performed: Zhang Q, Shi R, Shi Y, Zhan Q, Wang J, Hu H; data analysis: Zhang Q; draft manuscript preparation: Zhang Q, Gong C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Due to administrative requirements, the original data of the experiments during the research period of the project are not available to the public, but available from the corresponding author, or the first author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Reagent used in this experiment.

- Supplementary Table S2 Molecular biological identification of pathogen.

- Supplementary Table S3 Antagonistic effect of biocontrol strain with pathogen of gray blight disease.

- Supplementary Table S4 Molecular biological identification of biocontrol strain.

- Supplementary File 1 Sequences obtained from BLAST.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Q, Shi Y, Zhan Q, Shi R, Li J, et al. 2025. Identification and evaluation of antagonistic bacteria for biocontrol of tea gray blight. Beverage Plant Research 5: e040 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0029

Identification and evaluation of antagonistic bacteria for biocontrol of tea gray blight

- Received: 05 April 2025

- Revised: 10 June 2025

- Accepted: 07 July 2025

- Published online: 04 December 2025

Abstract: Tea gray blight is a prevalent fungal leaf disease affecting tea plants. It primarily targets tea leaves, and in severe cases, significantly impairs tea yield and quality. In this study, leaf samples displaying tea gray blight symptoms were collected from the tea plantation base in Xixiang County, Shaanxi Province, China. Pathogenic fungi were isolated using the tissue isolation method and identified through a combination of morphological, pathogenicity, and molecular biological analyses. The main pathogenic fungi were identified as belonging to the genera Pestalotiopsis, Neopestalotiopsis, and Pseudopestalotiopsis. Concurrently, eight bacterial strains with remarkable antagonistic effects against the pathogenic fungi were isolated from the rhizosphere soil of severely infected tea plants. Through 16S rDNA sequence analysis, these antagonistic bacteria were identified as Streptomyces castaneus, Bacillus velezensis, three strains of B. subtilis, Microbacterium sp., B. amyloliquefaciens, and Streptomyces sp., respectively. All eight antagonistic bacteria demonstrated the capacity to produce indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), among them, strain X8 exhibited the highest IAA production, reaching 107.2 μg/mL. Further research found that four strains of antagonistic bacteria named X10, X11, X14, and X17-B showed particularly significant inhibitory effects on the five strains of pathogenic bacteria. Additionally, the antagonistic bacteria in the soil exhibit a certain level of resistance to adverse conditions. Among them, both X10 and X17-B showed high salt tolerance, while X21 showed better drought tolerance. This study provides a selection basis for the development of biocontrol agents suitable for the winter closing garden management of tea plants and microbial agents of bio-organic fertilizers used for applying base fertilizers in autumn.

-

Key words:

- Tea gray blight disease /

- Pestalotiopsis /

- Antagonistic bacteria /

- Bacillus /

- Biocontrol agent