-

Tree crops such as shea, coconut, coffee, cashew, baobab, and many more, play a significant role in sustaining livelihoods globally, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. They provide food, income, and ecosystem services that support rural economies[1−3]. Adansonia digitata L., commonly known as baobab, is a multi-purpose tree species[4,5], largely distributed throughout the savanna and desert regions of Africa[5−7]. Baobabs constitute important components of tropical biodiversity and culture; and its species not only contribute highly to tropical biodiversity and culture[8], but also have edible parts (fruits, leaves, and seeds) that help to ensure food security[9,10], resilience for populations during the lean season[11], and human health[12,13]. The tree provides nutritious food[14], livestock fodder, material for hunting and fishing, medicine, shade, veterinary, and spiritual services for local people in Africa[15]. Its leaves contain nutritional components and antioxidant properties[16], and are traditionally included in the diet to positively support nutritional status[13]. Moreover, A. digitata seeds and fruit have significant potential as antioxidants and antimicrobial agents, as well as antidiabetic and hepatoprotective agents[17,18]. However, the species currently face a growing interest from population, NGOs, and enterprises[4] while also being threatened by the impact of climate change[19,20]. In fact, its phenology, mainly the loss of leaves during the dry season, and the high harvest intensity of the trees with leaves can negatively affect its populations. Projections also predicted a large reduction in the distribution range of baobab under future climatic conditions[19]. Urgent measures must be taken for its conservation and domestication[21]. An alternative and sustainable solution for the conservation of the species, and for the assurance of the leaves' availability year-round is its domestication or cultivation and production of the leaves through market gardening. This approach will not only increase the harvested biomass of A. digitata leaves but will also ensure the reliability and quality of supply[22].

Previous studies have focused on the influence of drought on A. digitata root growth[23], seedlings water use strategies[24], and functional responses[5]. There are also studies on the influence of abiotic factors such as precipitation, soil gradient, and climatic zones on baobab root distribution[23], seedling morphological characteristics (e.g., number of leaves, length)[25,26], and morphometric diversity[27]. Other research has also investigated the effect of ecological factors on its flowers' and leaves' nutritional composition; as well as its diversity, seed germination, and early growth[26−28], fruit morphological diversity, and productivity[29]. The contribution of A. digitata to food security through its consumption, and income from trading has also been explored[30,31]. For instance, De Smedt et al.[5] reported a reduction, morphology alteration of A. digitata leaf, and biomass allocation to the root system under drought stress, despite the ability of baobab seedlings to maintain a high-water status during drought events to prevent xylem cavitation, and to survive dry periods. Moreover, the seedlings are affected by environmental water status, with smaller seedlings in dry environments, with fewer leaves, and higher taproot water content[25]. Egbadzor[28] also found a slow growth in baobab plants, while Assogbadjc et al.[32] reported an improvement in its productivity under clayey and silty soils. Consequently, significant morphological variations exist among African provenances of A. digitata[30], and different morphological characteristics may arise according to the seed's provenance (drier or wetter condition). To our knowledge, few research studies have investigated the influence of biochar on both soil moisture, and seedling growth and yield parameters. Efforts should be geared toward the domestication of baobabs to ensure the sustainability of the tree species that will enhance its uses[23,29]. Domestication and cultivation of the plant will improve biodiversity, which can drive many livelihoods and important strategies in solving food and nutrition insecurity, poverty, export, and sometimes environmental degradation[33]. This work aims to fill this gap by introducing new ideas regarding the domestication of baobab through garden cropping under the use of biochar for soil water control.

Biochar is a multifunctional porous material from organic material, characterized by high porosity, surface area, pH, and low particle density compared to soil. It has attracted attention because of its great potential, including the improvement of soil physicochemical properties[34−37], and its effects on climate systems[38]. These qualities have led to its high adoption in agriculture to enhance crop productivity, sequester C in soil, and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions[39−41]. Biochar has also been used in various soil management practices to improve the soil water and nutrient availability for crop growth[42−44]. It delays the time required for the soil moisture content to drop to field capacity, and increases the upward transport of water from the deeper soil layers at night[45]. Therefore, the use of biochar could offer a viable option to improve moisture storage, and water use efficiency for soils poor in organic carbon in arid and semiarid zones[29]. However, the response of crops to biochar application can vary widely, ranging from negative to positive depending on the biochar characteristics, method of application, and the background soil conditions[43,46]. For example, biochar improves crop yield for nutrient-poor or degraded soils, whereas effects were marginalized under healthy soils[47,48].

This study evaluates the effect of biochar application on soil moisture content, and on growth and biomass production of A. digitata. It first examines the influence of biochar on soil moisture content and the growth parameters of A. digitata including, height, stem diameter, and number of leaves, along with fresh and dry biomass yields. Then, it evaluates the relationship among the above-presented factors with the growth and yield parameters of A. digitata seedlings. Three levels of biochar were applied, namely 0, 20, and 35 g (B0, B20, and B35, respectively), from the 1st to the 90th day after transplanting, with two weeks harvesting frequency. The findings provide insights into A. digitata seedlings biomass availability under different doses of biochar, and its effects on soil moisture content for their integration in legume production systems. The use of A. digitata leaves in legume production systems can help to reduce unsafe food, and to mitigate the effect of climate change on A. digitata trees.

-

As the regional capital of Northern Benin, the commune of Parakou is located in the center of the Republic of Benin, at 407 km from Cotonou, and 318 km south of the commune of Malanville. It is situated at 9°21' N, 2°36' E, at an average altitude of 350 m, and has a fairly modest topography (City Hall of Parakou, 2004). The commune of Parakou is bordered in the north by the commune of N'Dali, and in the south, west, and east by the commune of Tchaourou. The experiment was carried out at the Laboratory of Hydraulics and Environmental Modeling (HydroModE-Lab) experimental site (09°20.153' N and 002°38.883' E) within the University of Parakou (Benin).

Climate and soil of the study area

-

The climate of Parakou is humid tropical (Sudanese climate) and characterized by an alternation of a rainy season (May to October), and a dry season (November to April). The annual mean precipitation is about 1,200 mm per year, and is particularly higher in July, August, and September. The lowest temperatures are recorded from December to January. The annual average temperature is 26.8 °C. The Parakou region is characterized by tropical ferruginous soils of light texture with significant thickness due to low erosion. However, low erosion usually occurs in Parakou soils, leading to significant deep leaching.

Study design

-

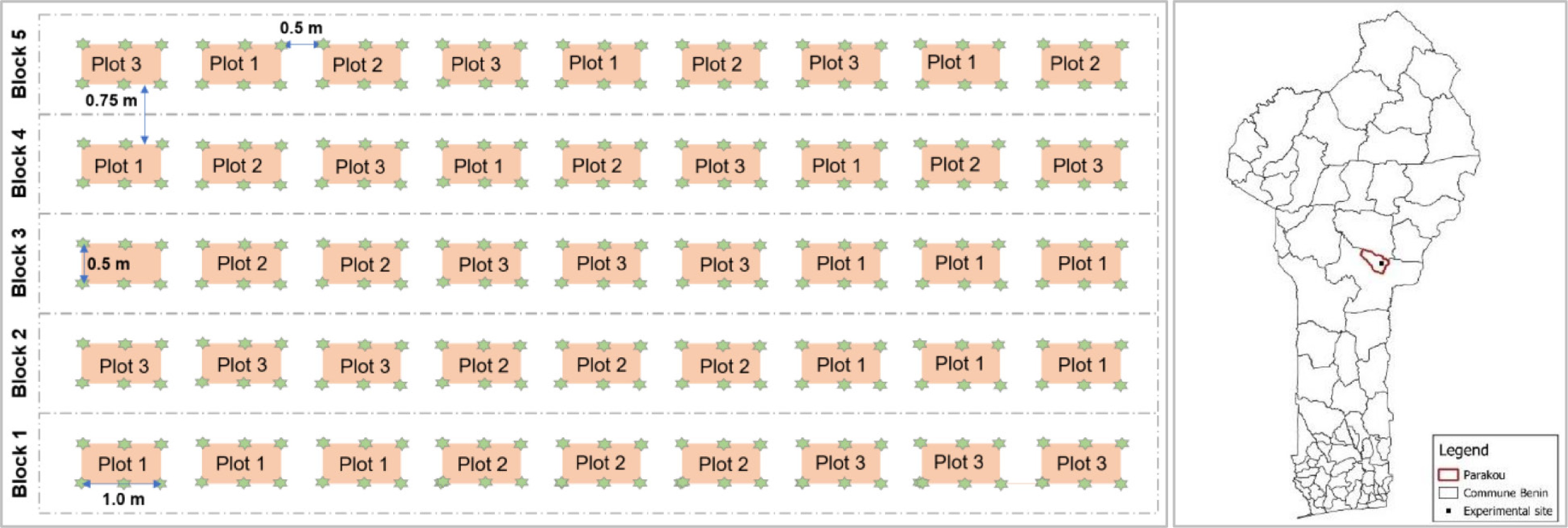

This study used A. digitata as biological material, provided by the nursery of the HydroModE-Lab experimental site. The trial lasted three months, and was conducted at the experimental site of the Laboratory of Hydraulics and Environmental Modeling (HydroModE-Lab), located in the commune of Parakou (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(left) Study design, and (right) location of the study site in the commune of Parakou (dark thick line), Benin Republic. Green stars are Adansonia digitata trees. Three plots were considered as a subblock that was replicated three times.

The experimental setup consisted of five blocks spaced 0.75 m apart; with a total length of 13.5 m, and a width of 0.5 m (Fig. 1b). The blocks consisted of nine plots, each 1 m long and 0.5 m wide. In each block, three plots were considered as a subblock that was replicated three times. The seedlings were transplanted with 0.5 m × 0.5 m spacing on each plot, leading to six plants per plot (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, three doses of biochar, including 0, 20, and 35 g (B0, B20, and B35, respectively), were applied across each block according to the method of Sousa & Figueiredo[49]. For each plot, each seedling received one dose of biochar at the beginning of the experiment, a week after transplanting. Each biochar dose was therefore repeated three times in each block.

Data collection and analysis

Growth parameters

-

Growth parameters, including the seedling height, the stem diameter at two heights (10 and 20 cm from the ground), and the number of seedling leaves were investigated. The height was measured using a tape, by measuring the vertical distance from the ground to the terminal bud. It was taken on four seedlings from each plot, three times a month (every 10 d). The diameter was measured at 10 and 20 cm from the ground using a digital vernier caliper, once a month on the four plants used for the height determination. Finally, the number of leaves per plant was determined by monthly counting of the leaves on each plant within the plots, prior to each harvest. Then, harvested leaves after counting were weighed using a scale to obtain the fresh biomass.

Productivity of A. digitata

-

Per Zakari et al. (data not published), after each harvesting, the leaves were weighed for each plant to determine the fresh biomass yield. Then, the leaves were dried in the oven for 72 h, at a temperature of 70 °C. Once dry, the leaves were weighed again to determine the dry biomass yield produced by the plants. Both yields were determined by dividing the amount of fresh or dry matter by the area occupied by each seedling.

Soil water content and rainfall

-

The radial soil water content was taken at three levels, namely at 0, 10, and 20 cm from the collar using a moisture meter. To minimize diurnal variation effects, all measurements were taken at 7 a.m. Soil moisture was measured every two days. Daily rainfall data was obtained from the rain gauge installed in the HydroModE-Lab application site. Thus, after each rainfall, the amount of water was directly taken from the rain gauge.

Statistical analysis

-

The collected raw data was first recorded into an Excel spreadsheet, and statistical tests were performed using R software, version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024). The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to assess the normality of the different response variables, including fresh and dry biomass, and non-normal data were log transformed. Analysis of variances (ANOVA), and t-tests were used to evaluate the effect of factors on response variables (tree height, stem diameter, soil water content, and biomass yields), and to compare the response variables between factor levels concerning biochar rates (10, 20, and 35 g per plant), soil depth (shallow cm and deep), and days after transplanting (DAT) (see results in Supplementary Tables S1−S6). Correlation analyses were computed for the quantitative variables, followed by a principal component analysis (PCA) to obtain the dependent relationships among the variables. Finally, Structural Equation Model (SEM) analysis was computed to evaluate the dependency between exogenous and endogenous variables. PCA was performed using the 'factoextra' package[50], and SEM using the 'Lavaan 0.6-19' package[51] for R.

-

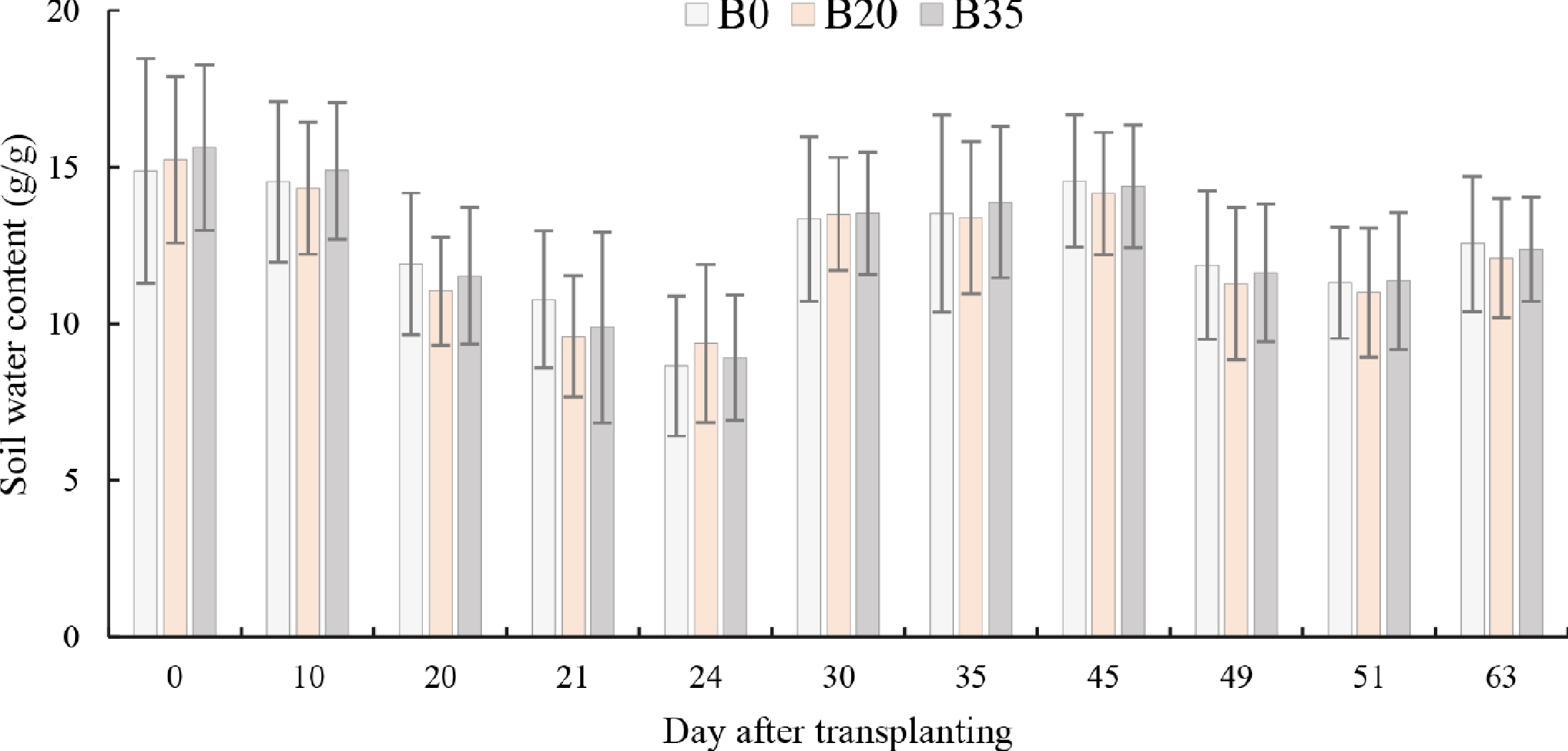

The average soil water content was significantly different between DAT (p < 0.001), and biochar levels (p = 0.001). Specifically, the average soil water content was 2.4% lower under B20 compared to B0, while there was no significant difference between B0 and B35 across all DAT (Fig. 2). Regarding the DAT, soil water content was highest at 0, 10, and 45, and lowest at 21, 24, and 51 DAT. Biochar had a significant effect on soil water content only at 20 and 21 DAT, with a 7.4% and 3.3% reduction under B20 and B35, compared to B0 at 20 DAT, respectively, and a 10.9% and 8.3% reduction at 21 DAT.

Figure 2.

Variation of day after transplanting soil water content under biochar application. B0, B20, and B35 are 0, 20, and 35 g biochar application, respectively.

Response of the number of leaves, stem diameter, and height of A. digitata seedlings to biochar application

-

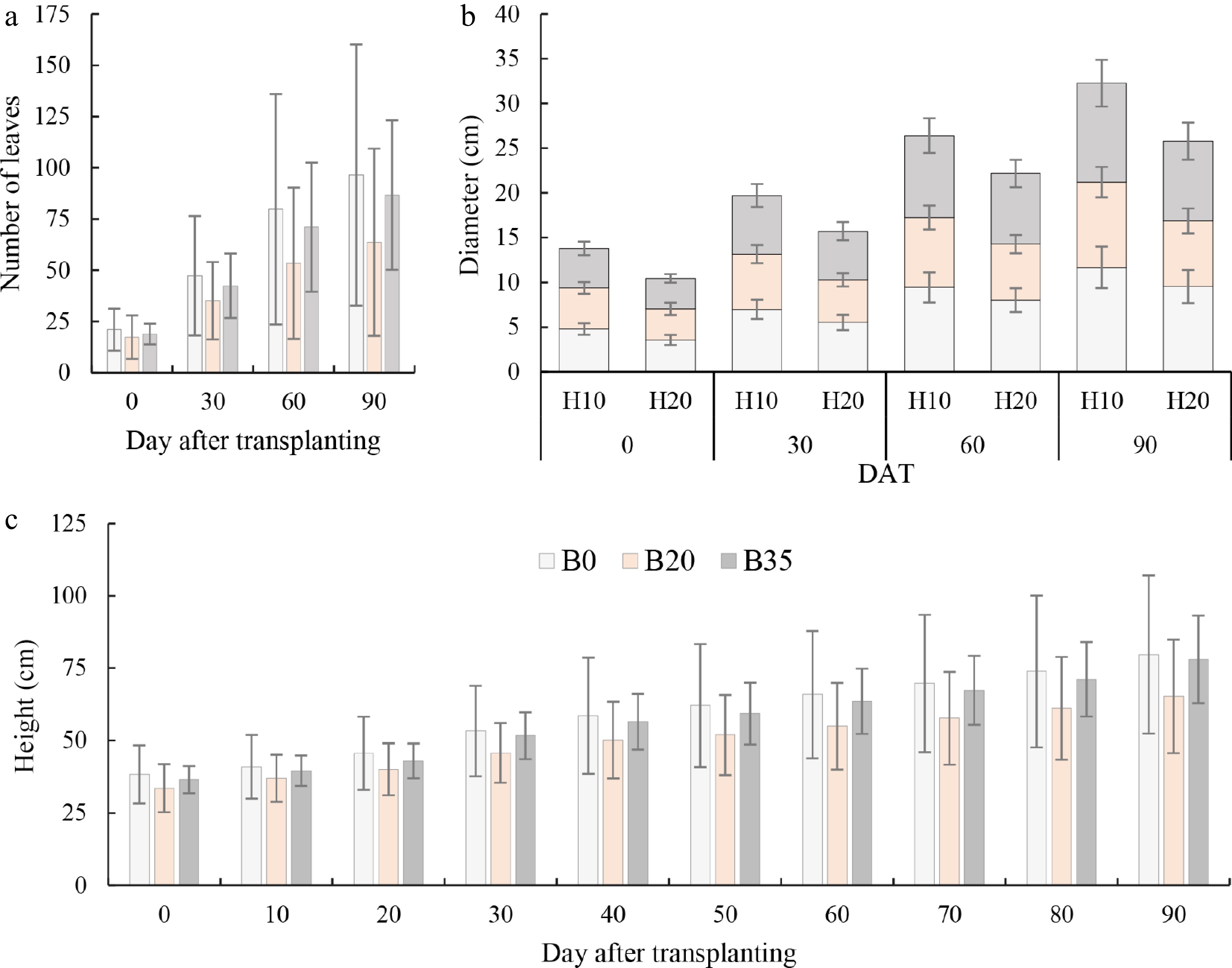

A. digitata seedlings leaf number consistently increased with DAT, with an overall average growth rate of 0.8, 0.9, and 0.5 leaves/day between 0−30, 30−60, and 60−90 DAT (Fig. 3). Under biochar treatments, the average growth rates were 32%, 44%, and 39% lower under B20 than B0 between 0−30, 30−60, and 60−90 DAT; and 10%, 12%, and 6% lower under B35 than B0. The number of leaves was statistically different (p < 0.01) among biochar rates at all DAT, with a consistent B0 > B20 > B35 trend (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Variation of (a) day after transplanting number of A. digitata seedlings leaves, (b) stem diameter at two heights, and (c) seedling height under biochar application. B0, B20, and B35 are 0, 20, and 35 g biomass application, respectively. H10 and H20 are 10 and 20 cm height for diameter measurement.

The stem diameter significantly increased with DAT, with an average growth rate of 5.9, 8.1, and 9.6 cm/day between 0−30, 30−60, and 60−90 DAT (Fig. 3b). Under biochar treatments, the average stem growth rates were 31%, 37%, and 27% lower under B20 than B0 between 0−30, 30−60, and 60−90 DAT; and 2%, 3%, and 22% lower under B35 than B0. A. digitata seedlings stem diameter differed significantly between sampling height at all DAT, with a consistent H10 > H20 trend. Regarding H10 (10 cm sampling height), the stem diameter was 5%, 12%, 17%, and 18% lower under B20 than B0 at 0, 30, 60, and 90 DAT; and 7%, 6%, 3%, and 5% lower under B35 than B0. The trend under H20 was similar to that of H10 (Fig. 3b).

The plant height consistently increased with DAT, with an overall average growth rate of 0.47, 0.35, and 0.43 cm/day between 0−30, 30−60, and 60−90 DAT (Fig. 3c). Under biochar treatments, the average height growth rates were 19%, 27%, and 25% lower under B20 than B0 between 0−30, 30−60, and 60−90 DAT; and 2%, 6%, and 5% lower under B35 than B0. The height of plants was statistically different (p < 0.01) among biochar rates at all DAT, with a consistent B0 = B35 > B20 trend (Fig. 3c).

Influence of biochar application on A. digitata seedlings leaves fresh and dry biomass

-

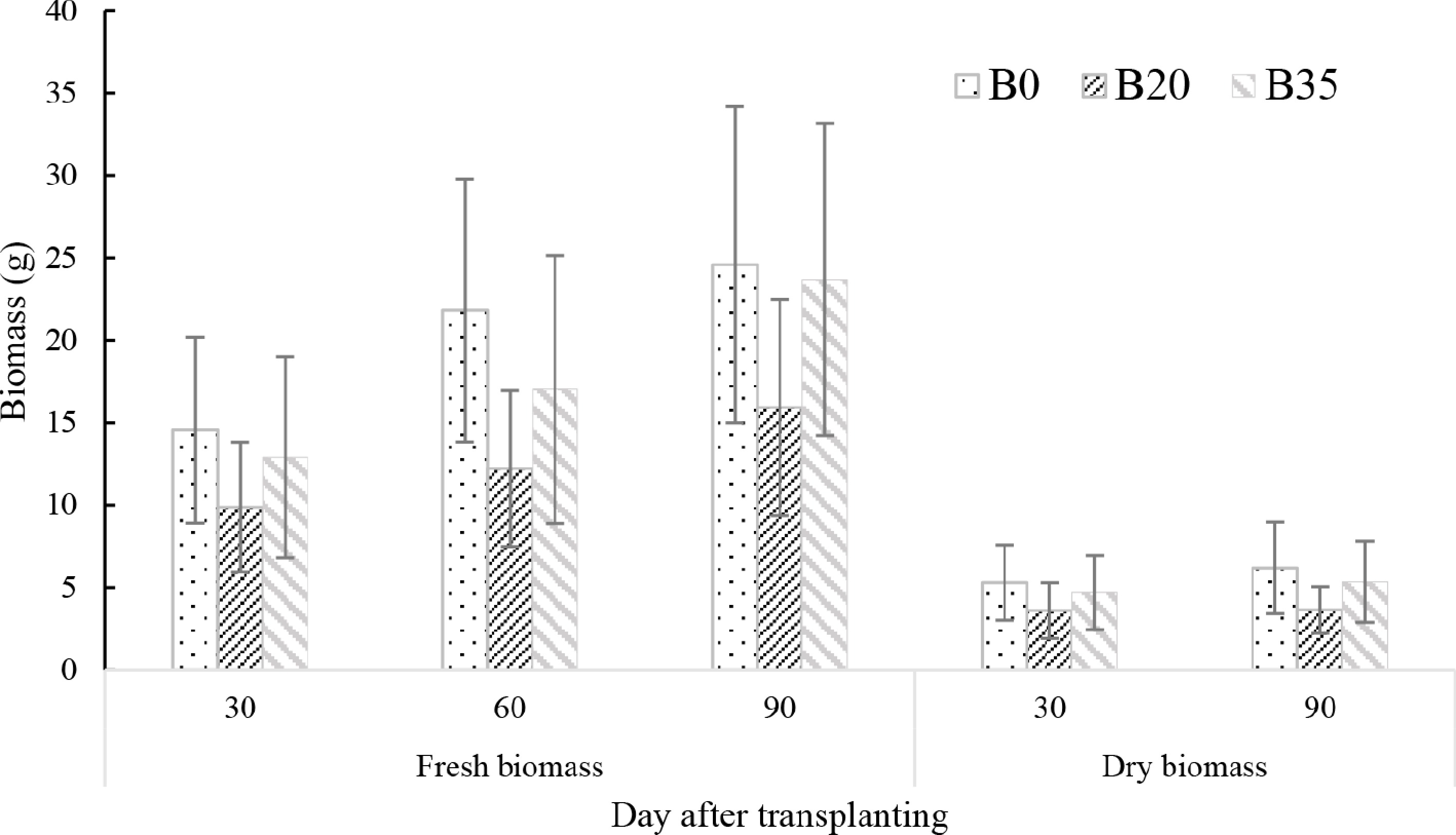

Fresh biomass yield differed significantly between DAT (p < 0.001), with a linear increase (30 < 60 < 90 DAT), while there was no difference in dry biomass between DAT (Fig. 4). Average fresh biomass was 38% and 12% lower under B20 and B35, respectively, compared to B0; while dry biomass was 35% and 13% lower. At each DAT, fresh biomass consistently followed the B0 > B35 > B20, except for 90 DAT, where B0 = B35 > B20. Similarly, dry biomass was consistently highest under B0, and lowest under B20 at 30 and 90 DAT (B0 > B35 > B20) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in day after transplanting A. digitata seedlings leaves fresh and dry biomass yields under biochar application. B0, B20, and B35 are 0, 20, and 35 g biomass application, respectively.

Relationships and effect of applied factors on soil water content, A. digitata growth parameters and biomass yields

-

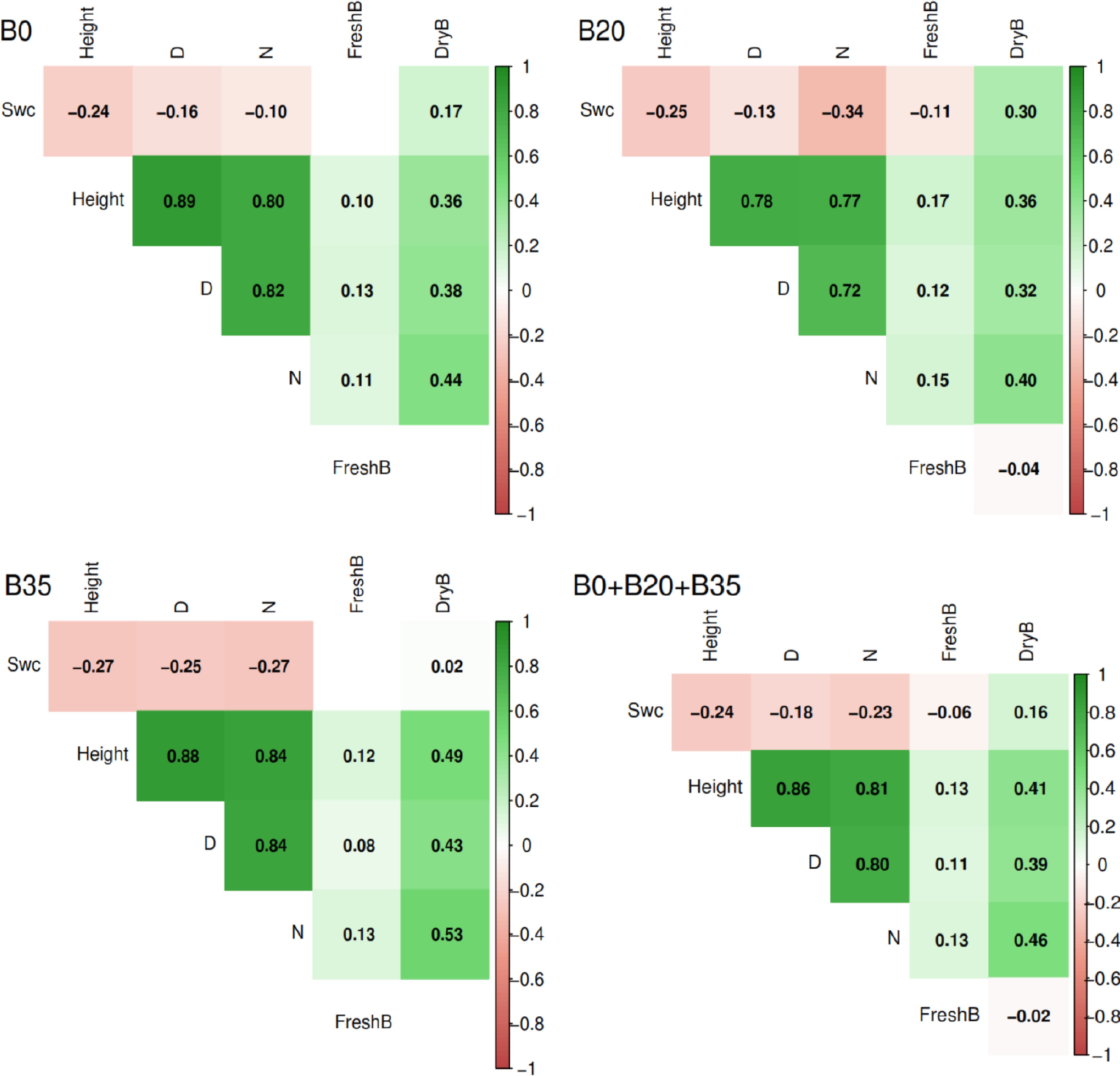

Generally, the soil water content was positively correlated with dry biomass (r = 0.16), but negatively correlated with plant height, diameter, leaf number, and fresh biomass (r = −0.24 to −0.06) in the overall dataset (B0 + B20 + B35) (Fig. 5). The plant height, diameter, and leaf number were all positively correlated with fresh and dry biomass (r = 0.11 to 0.86); however, fresh biomass was negatively correlated with dry biomass (r = −0.02). Overall, the correlation between soil water, plant growth, and biomass yields under B0, B20, and B35, followed the same trend as observed for B0 + B20 + B35 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis among soil water content, and A. digitata growth parameters and biomass yields using B0, B20, B355, and global data (B0 + B20 + B35). B0, B20, and B35 are 0, 20, and 35 g of biochar application, respectively.

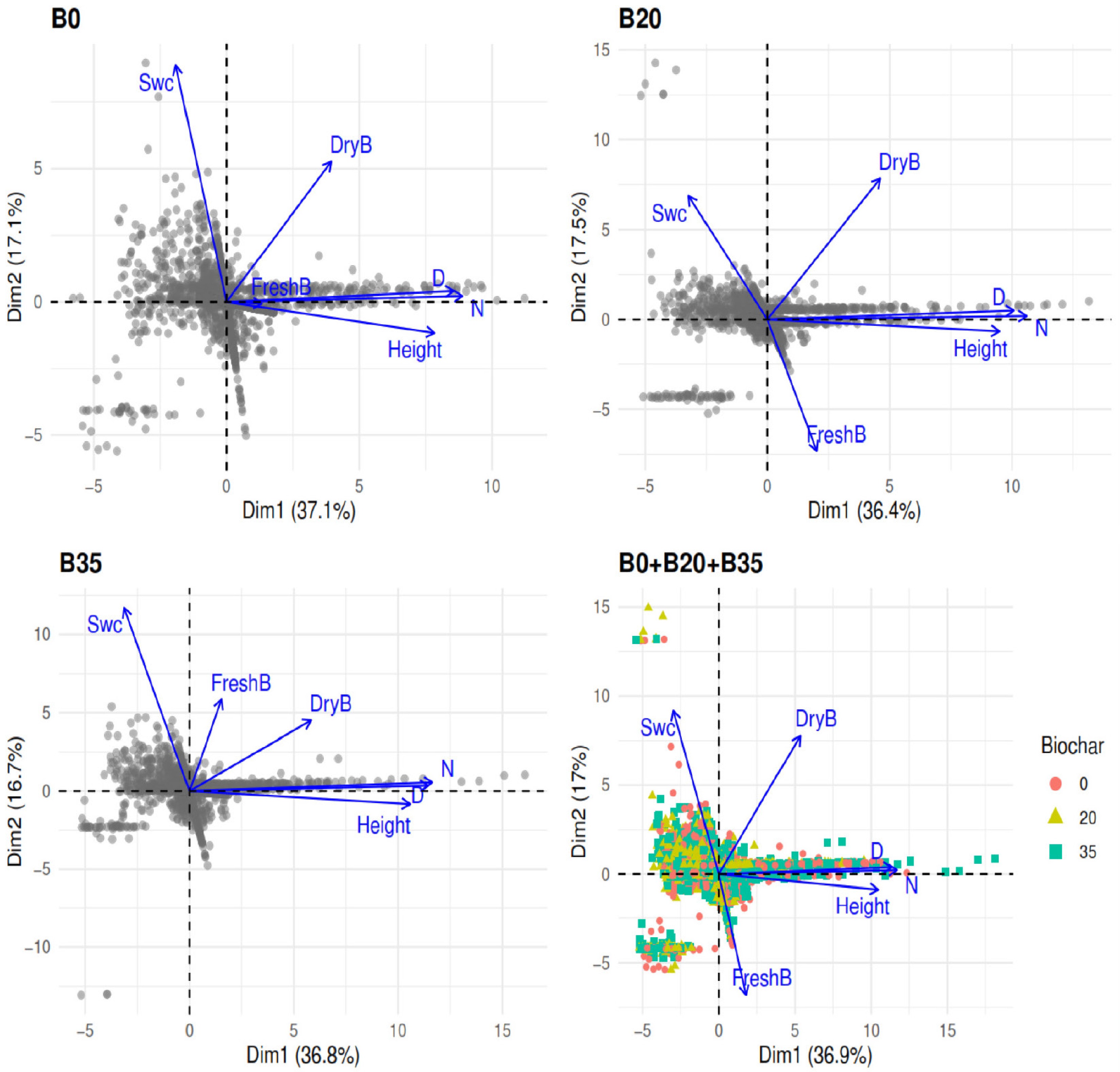

The first and second axis of the principal component analysis successfully explained 36.9% and 17% of the total variation under B0 + B20 + B35 (Fig. 6). On the first axis, soil water content was negatively associated with growth plant height, diameter, leaf number, fresh, and dry biomass. On the second axis, soil water content was positively associated with dry biomass, plant diameter, and leaf number, but negatively associated with fresh biomass and plant height. Generally, the PCA of variables under B0, B20, and B35 followed the same trend as for B0 + B20 + 35 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Principal components analysis among soil water content, and A. digitata growth parameters and biomass yields using B0, B20, B355, and global data (B0 + B20 + B35). B0, B20, and B35 are 0, 20, and 35 g of biochar application, respectively.

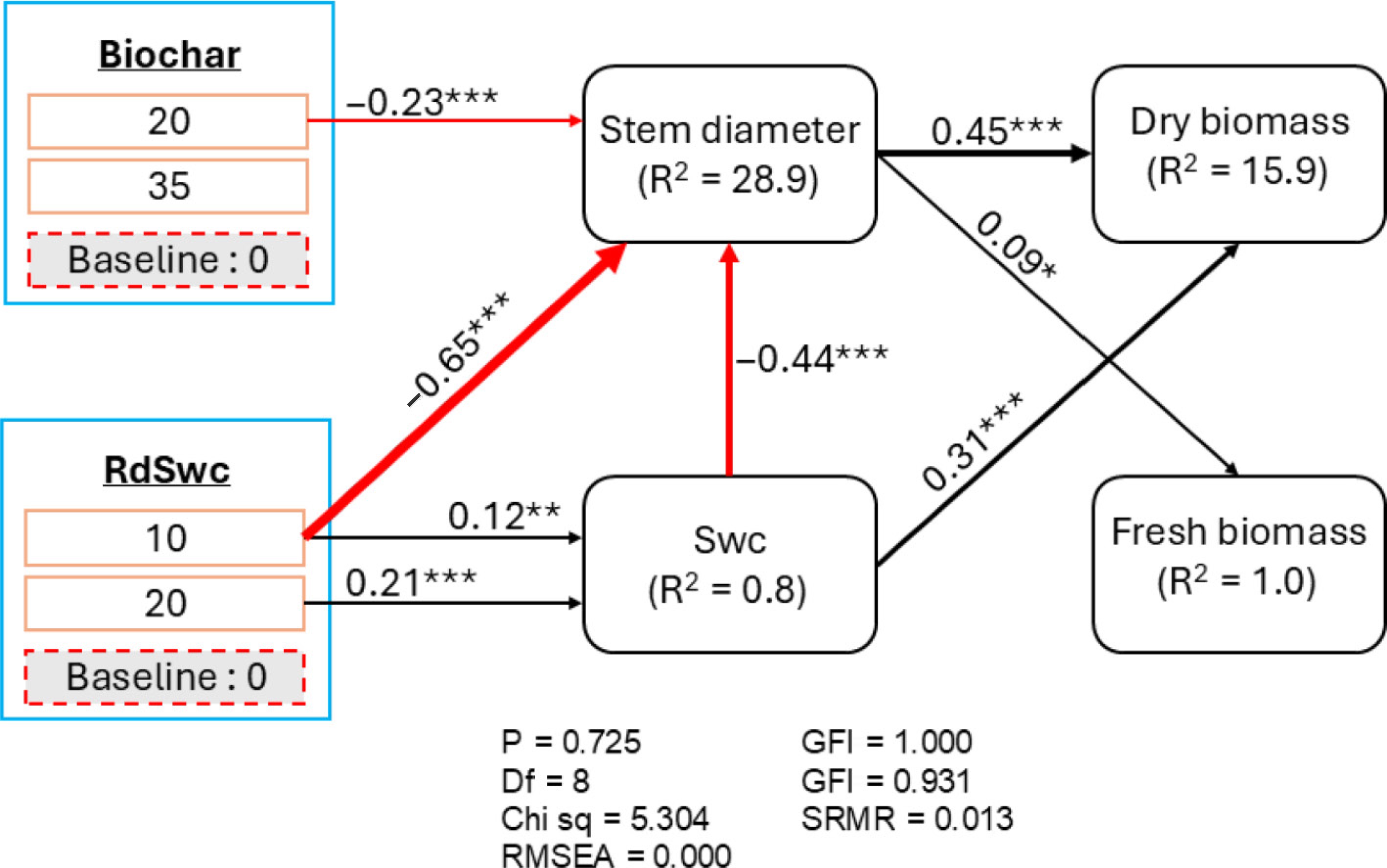

The fitted SEM indicated that biochar indirectly influenced fresh and dry biomass through a direct negative effect on stem diameter (λ = −0.23 for B20 compared to B0) (Fig. 7). The radial distances had a direct negative influence on stem diameter (λ = −0.65 for 10 cm compared to 0 cm) and positive influence on soil water content (λ = 0.12 and 0.21 for 10 and 20 cm, respectively, compared to 0 cm). The soil water content had a negative influence on stem diameter (λ = −0.44), but positive influence on dry biomass (λ = 0.31). Generally, the SEM explained 28.9%, 0.85, 15.9%, and 1.0% of variation in stem diameter, soil water content, dry biomass, and fresh biomass, respectively (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Structural equation model showing the underlying mechanism of soil water content, and A. digitata growth parameters and biomass yields under harvesting intensity. The thickness of the path equates to the strength of the path coefficient. Black and red arrows indicate positive and negative paths respectively. Green color ellipse are response variables; bule color boxes represent the factor, and below each factor is shown its level and the baseline of comparison. The proportion of variation explained by the model (R2) are shown next to each endogenous variable. B0, B20, and B35 are 0, 20, and 35 g of biochar applications, respectively. Asterisks associated to values are the level of significancy of the p-value (*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; and * p < 0.05). Chi square = 5.304, p-value = 0.725, degree of freedom (DF) = 8, RMSEA = 0.001, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 1.000.

-

It was found that biochar levels significantly affected the soil water content (p < 0.01). The sensitivity of soil water content to biochar could be explained by increased microbial activity and respiration following biochar addition[52], which temporarily raised soil evaporation demand[53]. Additionally, the high porosity of the applied biochar may have enhanced rapid water drainage[54]. Furthermore, the short-term rainfall and temperature fluctuations at 20 and 21 DAT, and the possible hydrophobic behavior of fresh biochar surfaces, probably contributed to the temporary reductions in soil water content observed under B20 and B35. This result contradicts most studies, which typically report that the addition of biochar increases water retention in soil[55,56]. However, Edeh et al.[57] highlighted that the ability of biochar to improve soil hydraulic properties in the favor of plants is highly dependent on the soil texture, along with the physical properties of the applied biochar. In the present study, baobab was cultivated on a light-textured soil, thereby decreasing the ability of biochar to improve soil water retention. Razzaghi et al.[58] reported that biochar improved the plant available water content mainly in coarse-texture soils, while this improvement was lesser with increasing soil fineness.

Response of number of leaves, stem diameter, and height of A. digitata seedlings to biochar application

-

The reduced growth of A. digitata seedlings observed under B20 and B35 may be linked to altered soil water dynamics, as reflected by the lower soil water content observed under this biochar rate (Fig. 2), which may have limited water availability for leaf production, stem elongation, and height increase[59,60]. In addition, nutrient immobilization and changes in soil structure caused by biochar incorporation could have further constrained root development and nutrient uptake[61,62], thereby contributing to the slower growth observed. Generally, biochar in this study reduced baobab growth, but this reduction was lower with an increase in the dose (i.e., B35 was better than B20, although all less than B0). This could imply that the rate applied in this study may not be sufficient for baobab to specifically benefit from it. Similarly, Asai et al.[63] reported a reduction in plant growth as indicated by lower leaf chlorophyl level under low biochar rates (4 and 8 t/ha), while increasing the rate of biochar to 16 t/ha increased the leaf chlorophyl level, although not higher than the control without biochar addition. The same authors attributed this reduction to a diminution in available soil N under treatment with low biochar rate, indicating that biochar should be combined with mineral N supply in soils with low indigenous N content[63].

Influence of biochar application on A. digitata seedlings leaves, fresh, and dry biomass

-

Biochar application reduced both fresh and dry biomass of A. digitata seedlings, with B20 causing the largest reductions, and B35 showing intermediate effects. However, fresh biomass increased over time, while dry biomass remained relatively stable. This could be explained by the naturally slow growth and nutrient uptake of A. digitata seedlings, making them more sensitive to temporary nutrient imbalances[28,33] induced by biochar. Additionally, in tree crops such as A. digitata, higher carbon allocation to roots, delayed leaf expansion, and potential disruptions to microbial activity likely limited aboveground biomass accumulation under biochar application[64]. In fact, Cárate Tandalla et al.[65] reported that tropical tree seedlings exhibit species-specific biomass allocation responses to soil nutrient changes, with conservative strategies often prioritizing root investment rather than shoot growth under resource-limited conditions. In the present study, a higher dose of biochar (B35) reduced the yield penalty observed in B20. Similarly, Murtaza et al.[61] reported that biochar applied at lower rates could initially suppress seedling biomass due to nutrient immobilization and altered rhizosphere conditions, while higher application rates led to partial recovery in growth, though still below that of unamended soils. Khan et al.[66] also highlighted that biomass responses often follow a dose-dependent pattern, with moderate to high rates improving soil structure and nutrient availability compared to low rates, but plant biomass typically remains lower than in control soils without biochar.

Relationships and effect of applied factors on soil water content, A. digitata growth parameters, and biomass yields

-

The correlation and PCA revealed that soil water content was negatively associated with plant height, stem diameter, leaf number, and fresh biomass, but positively associated with dry biomass. The contrasting patterns indicate that fresh biomass and growth variables respond to short-term water availability[67], and in drought-tolerant crops like baobab seedlings, moderate water stress may actually promote faster vegetative growth[5,68]. In contrast, structural tissue accumulation as indicated by dry biomass, benefits from sustained soil moisture, allowing steady deposition of cell walls and fibers even under higher water conditions[69]. Furthermore, the SEM indicated that biochar indirectly influenced fresh and dry biomass through a negative effect on stem diameter, and stem diameter itself was negatively affected by soil water content. This pattern may be explained by shifts in carbon allocation, as biochar can alter nutrient availability, stimulating the plant to direct more carbon toward roots or protective structures to cope with reduced soil water, rather than investing in stem growth[5,64].

The growth and biomass responses observed in A. digitata seedlings in this study suggest that the use of biochar as a soil amendment must be carefully tailored to local soil conditions. Baobab is a slow-growing, drought-tolerant species, often reported for its role in supporting community resilience under changing climates[28,70]. The finding that low doses of biochar can suppress early growth, implies that indiscriminate application may undermine seedling establishment, which is an important phase for long-term survival in regions of sub-Sahara Africa. However, the partial growth and biomass recovery seen at higher doses, although still below the control (without biochar), indicate that biochar may interact with soil nutrients and microbial processes in ways that require site-specific management. Future studies should investigate the response of baobab under higher doses of biochar, as well as the economic implications, to identify sustainable biochar-based soil management that will provide ecological and economic returns in the region. Furthermore, this study was limited to early seedling growth and biomass accumulation. Additional research is needed over longer time frames to evaluate the sustainable impact of biochar application, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of its ecological consequences on baobab growth and foliar yield.

-

The present research evaluates the influence of biochar application on soil moisture, growth parameters, and biomass yield of Adansonia digitata seedlings in tropical rainfall conditions. It also examines the interrelationship among these variables for better baobab seedling leaf biomass production. In short, the soil water content has a direct effect on seedling dry biomass, but not on the fresh biomass. The findings highlight that biochar application improves the soil water content for its resilience to water stress during dry patches. But the different doses of biochar exhibited lower soil water content, compared to the control. Generally, they still do not outperform control conditions. However, biochar application may not improve Baobab seedlings' growth and biomass parameters. Moreover, local rainfall distribution should be considered to create a managed condition for better soil water under baobab seedling growth. Future research should examine the processes and factors (soil and climate) underlying biomass decrease under high biochar application. This would help in proposing sustainable management practices that combine water conservation benefits with tree conservation.

We acknowledge the Alliance of National and International Science Organizations for Belt and Road Regions (ANSO) for providing desk and facilities that helped to validate the data used in this paper through data analysis and manuscript writing, Funded by CAS-ANSO Fellowship. (Grant No.: CAS-ANSO-FS-2025-47).

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Zakari S, Tovihoudji PG; writing original draft: Boukari SA, Orou Yorou N, Yessoufou MWIA, Zakari S; formal analysis: Sékaro Amamath Boukari, Mouiz Wal-Ikram Aremou Yessoufou, Sissou Zakari; data curation: Boukari SA, Yessoufou MWIA, Zakari S; writing, review, and editing: Zakari S, Tovihoudji PG, Akponikpè PBI; supervising: Zakari S, Akponikpè PBI; funding acquisition: Zakari S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Tables S1 Statistical analysis results of the effect of biochar application on A. digitata seedlings leaves fresh and dry biomass as a function of days after transplanting (DAT).

- Supplementary Table S2 Effect of biochar application on growth parameters (plant height, number of leaves, and stem diameter) of Adansonia digitata as a function of days after transplanting (DAT).

- Supplementary Table S3 Statistical analysis results of the effect of biochar application and days after transplanting (DAT) on soil water content.

- Supplementary Table S4 Statistical analysis results of the effect of biochar application on soil water content as a function of days after transplanting (DAT).

- Supplementary Table S5 Statistical analysis results of the effect of height on Adansonia digitata seedlings diameter as a function of days after transplanting (DAT).

- Supplementary Table S6 Statistical analysis results of the effect of days after transplanting (DAT) on Adansonia digitata seedlings leaves fresh and dry biomasses.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zakari S, Tovihoudji PG, Yessoufou MWIA, Boukari SA, Orou Yorou N, et al. 2026. Response of soil moisture, growth and biomass yield of Adansonia digitata under biochar application in Benin, West Africa. Circular Agricultural Systems 6: e002 doi: 10.48130/cas-0026-0001

Response of soil moisture, growth and biomass yield of Adansonia digitata under biochar application in Benin, West Africa

- Received: 14 October 2025

- Revised: 26 November 2025

- Accepted: 05 December 2025

- Published online: 20 January 2026

Abstract: Adansonia digitata L. (hereafter, A. digitata or Baobab) is widely distributed across the African continent, but its survival is threatened by low natural regeneration, and the effects of climate change. This study investigates the effect of biochar on soil moisture, growth parameters, and biomass yield of baobab seedlings. Three doses of biochar were applied, including B0: 0 g/plant, B20: 20 g/plant, and B35: 35 g/plant at the beginning of the experiment (0 day after transplanting, DAT). Soil moisture was measured at three radial distances from the seedling stems. The results show that the average soil moisture was 2.4% lower under B20 than B0, but no significant difference was observed between B0 and B35. Moreover, the soil water content varied with the local rainfall events, showing the highest soil moisture content at 0, 10, and 45 DAT, and the lowest at 21, 24, and 51 DAT. As expected, the leaf number, stem diameter, and height of seedlings increased with time. The leaf number growth rate was overall 0.8, 0.9, and 0.5 leaves/day between 0–30, 30–60, and 60–90 DAT, respectively; but was 32%, 44%, and 39% lower under B20 than B0, and 10%, 12%, and 6% lower under B35 than B0. The soil moisture was positively correlated with dry biomass, but negatively with growth parameters, and fresh biomass. It emerges from this study that the application of biochar did not consistently improve soil water retention or baobab seedling growth, highlighting the importance of adapting application rates to local pedoclimatic conditions.

-

Key words:

- Soil moisture /

- Leaves biomass /

- Legume production /

- Food security /

- Baobab seedlings.