-

Adansonia digitata L., (hereafter, A. digitata) commonly known as baobab, is a massive and exceptionally long-lived angiosperm tree whose distribution extends broadly across the African savanna regions[1−4]. It is a crucial component of the continent's tropical biodiversity and culture[5]; and offers an extensive range of resources derived from the tree as a whole or from its various parts[6]. Indeed, baobab is one of the most important Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) provided by African species, of which all the organs are almost useful (barks, fruits, leaves)[7]; and the trees have substantial socio-economic importance in African regions[8−10]. Therefore, it supplies medicinal services[11], nutritious food[12], livestock fodder, essential materials (bark fibers used for cordage), and medicinal services[11], as well as veterinary and spiritual services. For instance, A. digitata leaves possess healing, regulatory, and stimulatory properties[13]. In addition to its medicinal properties, baobab seeds, leaves, pulp, bark, capsules, and flowers are used for several purposes grouped into three main categories: nutrition, art and crafts, and culture[14]. Its young leaves, flowers, and seeds are consumed raw or boiled[15]. Leaves are generally consumed fresh during the rainy season, but in dried form (common practices in arid areas) during the dry season[13]. Fresh leaves are collected, dried, crushed, sieved into powder, and stored during the rainy season when they are abundant for later use during the dry season[13]. As a result, mainly the fresh leaves are available on the market during the rainy season, while only the processed dry leaves are sold during the dry season, despite the consumers' higher preference for fresh leaves.

Global climate change is a widely recognized problem with severe impacts on local environments[16], a phenomenon that is particularly critical in semi-arid systems. Studies have shown that these climatic shifts pose major threats to African biodiversity; for instance, projections indicate that over 5,000 African plant species could lose climatically suitable habitat by 2085[17] and up to 40% of African mammals could become critically endangered by 2080[18]. This stress is driving shifts in the spatial distribution of tropical biodiversity[19−21] and leading to extinction for species unable to migrate. In this context of rapid global warming, populations of several Non-timber Forest Product (NTFP)-providing species, including the baobab, are critically threatened by a dual pressure: the intensification of land use and unsustainable harvesting[22−24], and the direct impacts of climate change[2,25]. An alternative and sustainable solution for the conservation of the species and for the assurance of the leaves' availability year-round is their domestication or the cultivation and production of the leaves through market gardening. This solution will not only increase the harvested fresh leaves of A. digitata, but will also ensure the reliability and quality of the fresh leaves supply[26] and reduce the harvesting pressure on the natural baobab trees. However, few studies have investigated the local factors affecting the growth and functional traits of baobab seedlings under vegetable growing conditions.

Previous investigations have been undertaken on the dependence among harvesting frequency/intensity, growth, and biomass production, using species such as Leucaena leucocephala and Gliricidia sepium[27] and Manihot esculenta[28]. For instance,[28] reported that the leaves harvested only at the time of harvesting the tuberous roots, at 11.5 months after planting, yield 0.71 ton/ha of dry leaves; but this increases to 2.6 ton/ha if the leaves are harvested five times during the same period. However, studies on leaf harvesting of baobab trees have been conducted only on the influence of tree mutilation and on its fruit production[7], and bark harvesting on susceptibility to diseases. Dhillion et al.[7] showed that tree mutilation reduces the number of baobab fruit production, therefore, it can compromise the availability for baobab tree regeneration. Moreover, intensive bark harvesting affects baobab trees and makes them more susceptible to disease. As mentioned above, very few studies have focused on the influence of leaf harvesting on the biomass production of A. digitata and its effects on soil moisture content, especially in vegetable production sites.

The present study aims to fill these gaps by evaluating the interrelationships between leaf harvesting intensity and the growth and functional traits of A. digitata in semi-arid West African systems. It first examines the influence of A. digitata leaf harvesting intensity on soil moisture content at different radial distances from the plant's collar, and at two soil depths (namely, shallow and deep). Then, it analyzes the effect of A. digitata seedlings' leaf harvesting intensity on the tree's growth parameters, including plant height, stem diameter, and number of leaves, and on the fresh and dry biomass yields. Finally, this research relates the various above-presented factors to the growth and yield parameters of A. digitata seedlings. The harvesting intensity was chosen at two levels, namely 50% harvesting (I50) and 75% harvesting (I75), applied from 30th to 90th day after transplanting, with a two-week harvesting frequency. The findings provide knowledge on biomass availability under A. digitata seedlings leaves harvesting stress, and the effects of this latter on soil moisture content for their integration in legume production systems. The use of A. digitata leaves in legume production systems can help to reduce food insecurity and to protect A. digitata crops from climate-related impacts.

-

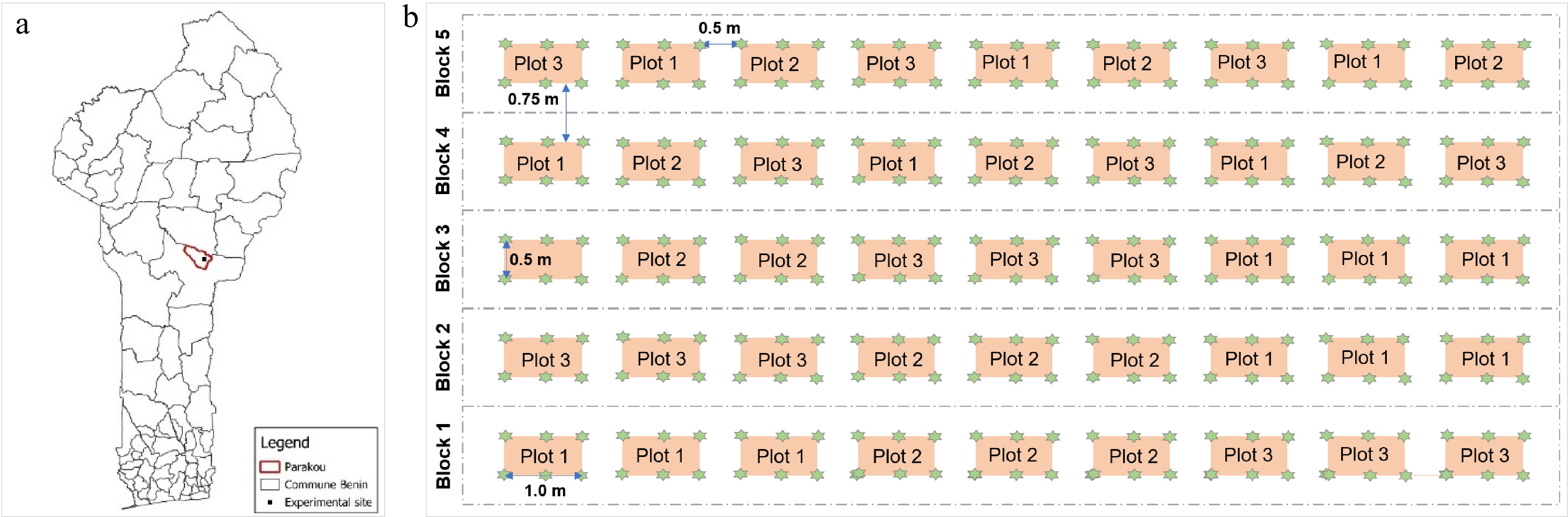

As the regional capital of Northern Benin, the commune of Parakou is located in the center of the Republic of Benin, 407 km from Cotonou and 318 km south of the commune of Malanville. It is situated at 9°21' N, 2°36' E at an average altitude of 350 m, and has a fairly modest relief[29]. The commune of Parakou is bordered to the north by the commune of N'Dali, and to the south, west, and east by the commune of Tchaourou. The experiment was carried out at the Laboratory of Hydraulics and Environmental Modeling (HydroModE-Lab) experimental site (09°20.153' N and 002°38.883' E) within the University of Parakou (Benin).

Climate and soil of the study area

-

The climate of Parakou is humid tropical (Sudanese climate) and characterized by an alternation of a rainy season (May to October) and a dry season (November to April). The annual mean precipitation is about 1,200 mm per year and is particularly higher in July, August, and September. The lowest temperatures are recorded from December to January, in Parakou. The annual average temperature is 26.8 °C. The Parakou region is characterized by tropical ferruginous soils of light texture with significant thickness due to low erosion. However, low erosion usually occurs in Parakou soils, leading to significant deep leaching.

Study design

-

This study used A. digitata as biological material, provided by the nursery of the HydroModE-Lab experimental site. The trial began on 09/06/2022 in the commune of Parakou and more specifically at the experimental site of HydroModE-Lab (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the study site, and (b) study design in the commune of Parakou, Benin. Green stars are Adansonia digitata seedlings. In each plot, 50% of leaves were harvested on two random trees (I50), 75% on the other two random trees (I50), and the remaining two trees were not harvested. Three plots were considered as a subblock that was replicated three times.

The experimental setup consisted of five blocks spaced 0.75 m apart, with a total length of 13.5 m, and a width of 0.5 m (Fig. 1b). The blocks consisted of nine plots, each 1 m long and 0.5 m wide. In each block, three plots were considered as a subblock that was replicated three times. The seedlings were transplanted with 0.5 m × 0.5 m spacing on each plot, leading to six plants per plot (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, leaf harvesting of A. digitata seedlings was applied at two levels for each plot in all blocks. For each plot, two seedlings were harvested at 50% of the total number of leaves they possessed at the sampling time, and two other seedlings at 75%. The remaining two seedlings served as a control and were not harvested.

Data collection and analysis

Growth parameters

-

The assessed growth parameters were the height of the plants, the stem diameter at the collar (10 and 20 cm from the ground), and the number of leaves per plant. The height (cm) of the plants was determined using a tape measure by measuring the vertical distance from the ground to the terminal bud. It was taken on four plants from each plot, three times a month (every 10 d). The diameter measurement was performed using a digital vernier caliper once a month on the four plants used for determining the height, at 10 and 20 cm from the ground. Finally, the number of leaves per plant was determined by counting the leaves on each plant in the plots before each harvest. Then, harvested leaves were counted and weighed using a scale to obtain the fresh biomass.

Productivity of A. digitata

-

After each harvesting, the leaves were weighed for each plant to determine the fresh biomass yield. The leaves were then dried in an oven for 72 h at a temperature of 70 °C. Once dry, the leaves were weighed again to determine the dry biomass yield produced by the plants. Both yields were determined by dividing the amount of fresh or dry matter by the area occupied by each seedling.

Soil water content and rainfall

-

Radial soil water content was assessed at 0, 10, and 20 cm from the plant collar using a moisture meter. To minimize diurnal variation effects, all measurements were taken at 7 a.m. Rainfall data were collected from a rain gauge installed at the HydroModE-Lab experimental site, with precipitation amounts recorded immediately after each rainfall event.

Statistical analysis

-

The collected raw data were first recorded into an Excel spreadsheet, and statistical tests were performed using R software, version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of each response variable, including tree height, stem diameter, soil water content, and biomass yields; non-normal data were log transformed. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) and t-tests were used to evaluate the effect of factors on the response variables (tree height, stem diameter, soil water content, and biomass yields), and to compare the response variables between factor levels concerning harvesting intensity (50% and 75%), soil depth (shallow and deep), and days after transplanting. Correlation analyses were performed for the quantitative variables, followed by a principal component analysis (PCA) to obtain the dependent relationships among the variables. Finally, a Structural Equation Model (SEM) was computed to evaluate the dependency between exogenous and endogenous variables. PCA was performed using the factoextra package[30], and SEM using the lavaan 0.6-19 package[31] for R.

-

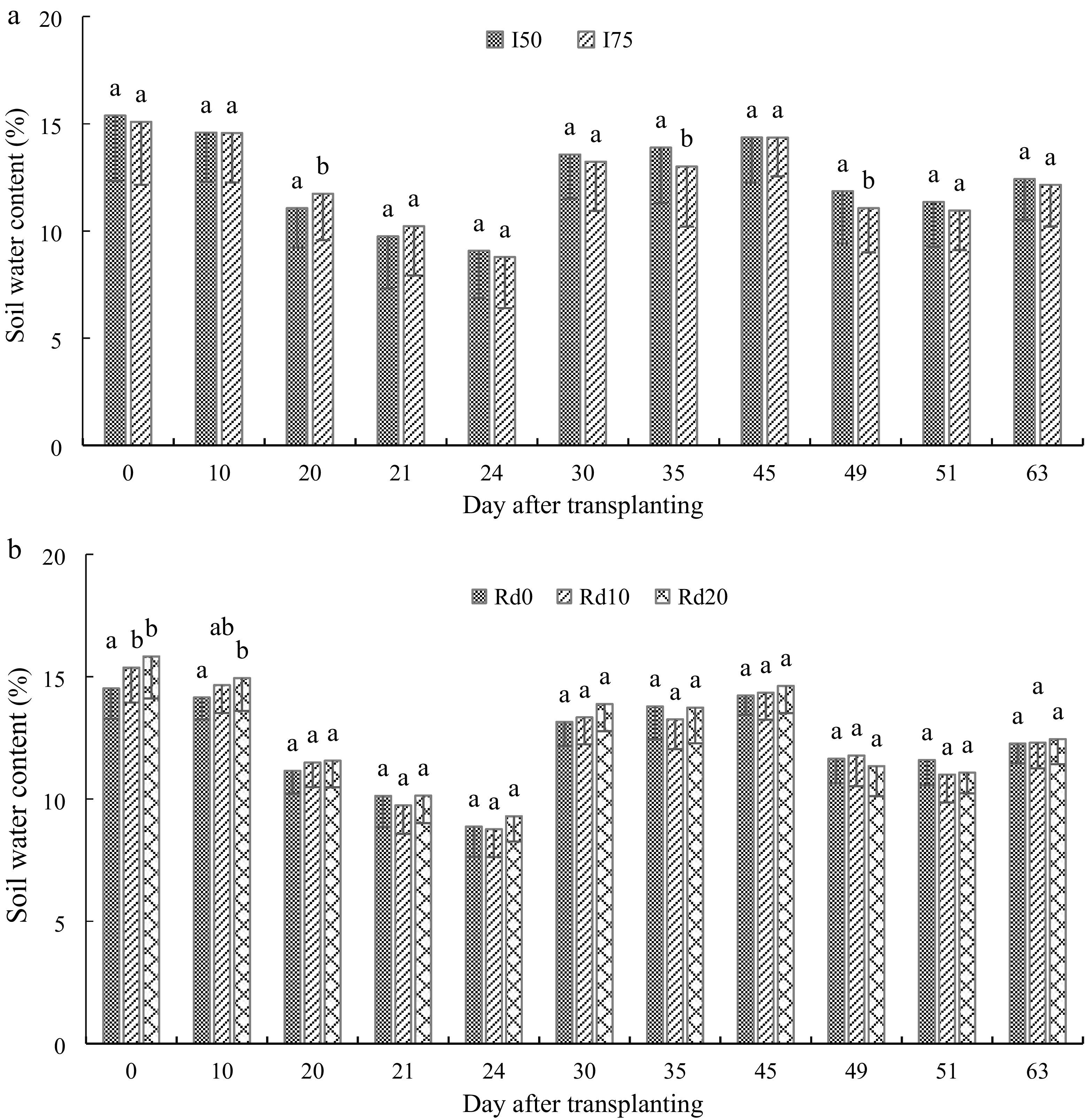

The difference in soil water content was significant between seedling leaf harvesting intensities (p = 0.010), among DAT (p = 0.001), among radial distances (p < 0.001), and for the interactions I × DAT (p = 0.025) and Rd × DAT (p = 0.008). Especially, the soil water content was significantly different between harvesting intensities at 20, 35, and 49 DAT, and among radial distances at 0 and 10 DAT. Overall, the soil water content was only 0.52% lower under I50 compared to I75 (Fig. 2a) and ranged in the order Rd20 > Rd10 > Rd0. Thus, high leaf harvesting would raise the soil water content. The soil water content varied according to DAT, with lower values at 20, 21, 24, 49, and 51 DAT (Fig. 2a). The highest soil moisture content occurred under I75, especially closer to the plant (0 and 10 cm), compared to I50 (Fig. 2b). The radial distances affected the soil water content at the beginning of the experiment (0 and 10 DAT), with significant differences found between Rd0 and Rd10 at 0 DAT, and between Rd0 and Rd20 at 10 DAT.

Figure 2.

Variation of day after transplanting soil water content under (a) A. digitata leaves harvesting intensity, and (b) soil radial distance from plant. I50 is 50% leaves harvesting, and I75 is 75% harvesting intensity. Rd0, Rd10, and Rd20 represent 0, 10, and 20 cm radial distance from the seedling stem, respectively.

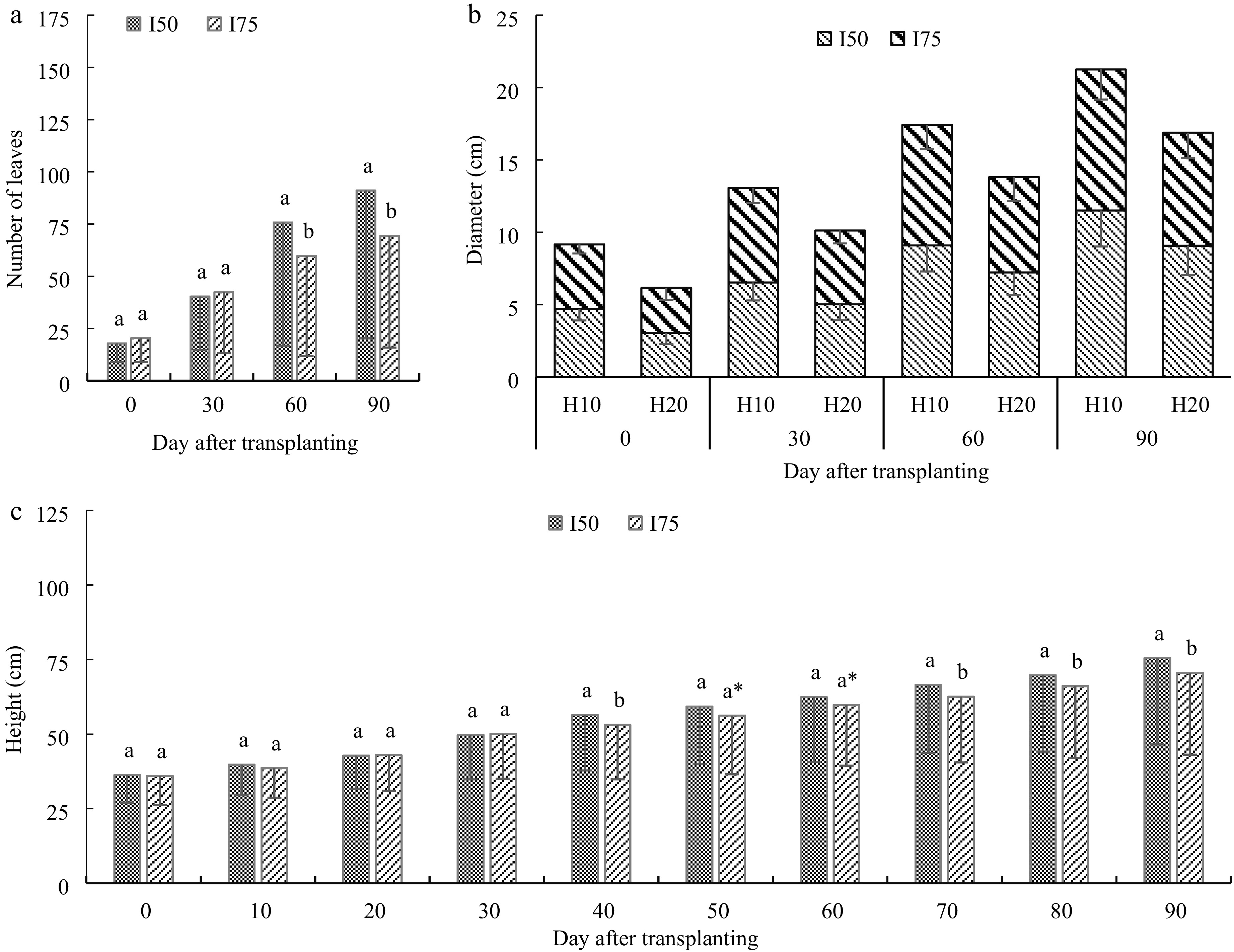

Response of day after transplanting A. digitata seedlings number of leaves, stem diameter and height to harvesting intensity

-

The number of leaves increased with raising DAT, with a higher average growth rate under I50 (62.1% higher) compared to I75 (Fig. 3a). The average growth rates were 1.28, 0.88 and 0.25 leaves/day under I50 between 0–30, 30–60 and 60–90 DAT, respectively; and 1.08, 0.41 and 0.16 leaves/day under (Fig. 3a). The number of leaves was not significantly different between I50 and I75 at 0 and 30 DAT (p > 0.05), but a significant difference was found at 60 and 90 DAT (p < 0.05) with a higher number of leaves under I50 compared to I75 for each DAT.

Figure 3.

Variation of day after transplanting (a) number of A. digitata seedlings leaves, (b) stem diameter at two heights, and (c) seedlings height under leaves harvesting intensity. I50 is 50% leaves harvesting, and I75 is 75% harvesting intensity.

A. Digitata seedling stem diameter progressively and significantly increased (p < 0.05) from 30 to 90 DAT, with higher rate under I50 (40% at 60 DAT and 76% at 90 DAT) compared to I75 (29% at 60 DAT and 53% at 90 DAT) (Fig. 3b). The stem diameter was different between diameter sampling height (p = 0.001), with higher stem diameter at 10 cm height for 60 and 90 DAT (8.71 and 10.63 cm, respectively) compared to 20 cm height (6.90 and 8.44 cm, respectively) (Fig. 3b).

The height of the plants gradually increased from the 30th to the 90th day after transplanting. The height increased at rates between 0.040 and 0.174 cm/day under I50, and 0.046 and 0.167 cm/day under I75 (Fig. 3c). The average height was 50.28 ± 13.97 cm at 30 DAT, 63.14 ± 20.81 cm at 60 DAT, and 78.04 ± 25.66 cm at 90 DAT under I50 (mean ± SE), and 50.14 ± 15.07, 59.76 ± 20.31, and 70.56 ± 27.41 cm at 30, 60, and 90 DAT, respectively (Fig. 3c). Overall, the average height was 2.56% higher under I50 compared to I75 (Fig. 3c). Similar to the number of leaves, plant height was not significantly different between I50 and I75 from 0 to 30 DAT (p > 0.05), but a significant difference occurred from 40 to 90 DAT (p < 0.05) with higher height under I50 compared to I75 at each DAT (Fig. 3c).

Influence of A. digitata seedlings leaves harvesting intensity on leaves fresh and dry biomass

-

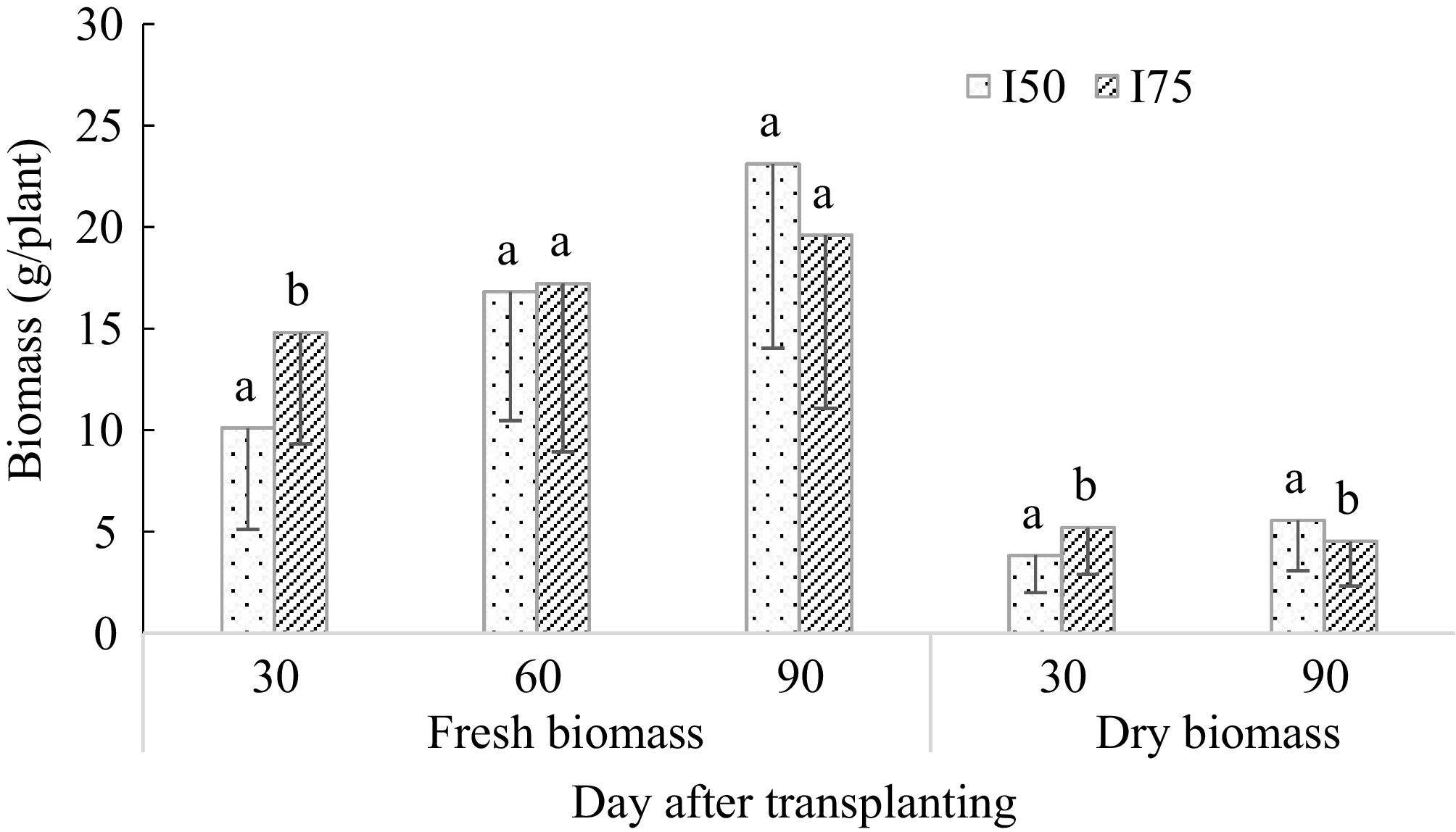

The fresh biomass yield was significantly different among DAT (p < 0.05), but the dry biomass was not. The average fresh biomass and dry biomass were 3.90% and 3.83% lower under I50 compared to I75, respectively (Fig. 4). However, the fresh biomass was significantly different between the two treatments at 30, 60, and 90 DAT, and the dry biomass only at 60 and 90 DAT (Fig. 4). The fresh biomass increased with increasing DAT both under I50 and I75, but the dry biomass increased only under I50 (Fig. 4). The fresh biomass yield was significantly higher under I75 only at 30 DAT, but the dry biomass yield was significantly different both at 30 and 90 DAT (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in the day after transplanting A. digitata seedling leaves, fresh and dry biomass yields under leaf harvesting intensity. I50 is 50% leaves harvesting, and I75 is 75% harvesting intensity.

Relationships and influence of factors on soil water content, A. digitata growth parameters and biomass yields

-

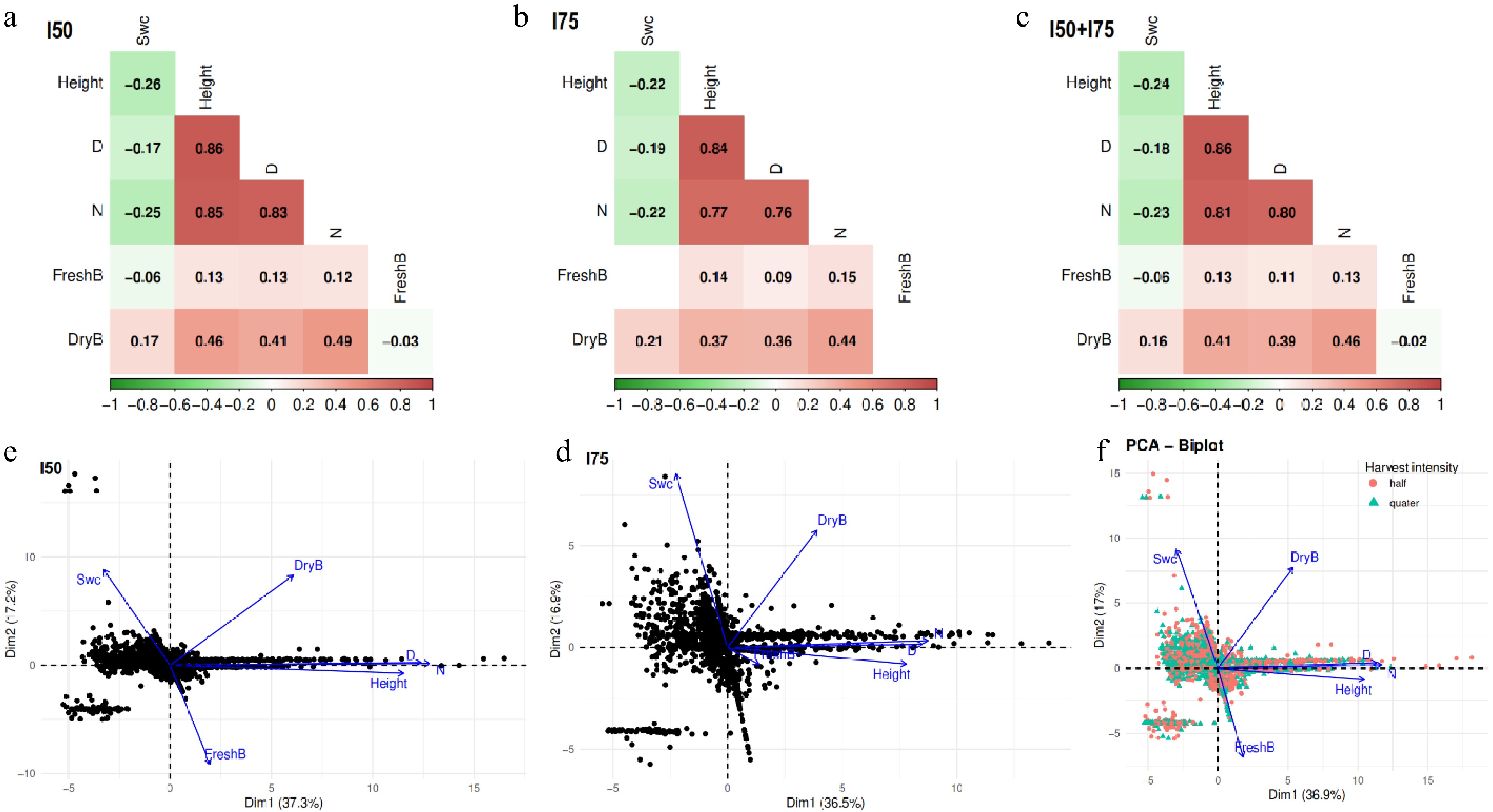

The soil water content was negatively correlated with growth variables (height, stem diameter, and number of leaves) and fresh biomass under I50 (r = –0.26 to –0.06) but was positively correlated with dry biomass (r = 0.17) (Fig. 5a). The fresh and dry biomass were positively correlated with growth variables, with correlation coefficients ranging between 0.12 and 0.49. Generally, the correlations between variables under I75 and I50+I75 followed the same trend as I50 (Fig. 5b, c).

Figure 5.

(a)–(c) Correlation, and (d)–(f) principal components analysis among soil water content, and A. digitata growth parameters and biomass yields using fI50, I75, and global data (I50 + I75). I50 and I75 are 50% and 75% leaf harvesting intensities, respectively. Swc: Soil water content; D: Stem diameter; N: number of leaves; FreshB: Fresh biomass; and DryB: Dry biomass. Axis 1 of the PCA separates growth-related variables from soil moisture.

The principal component analysis shows that the first two axes explained 37.3% and 17.2% of the total variance under I50 (Fig. 5d). Fresh biomass, dry biomass, and growth variables were positively associated and followed the first axis, but were negatively associated with soil water content (Fig. 5d). On the second axis, however, the soil water content and dry biomass were positively associated and followed the same direction, and the two variables were negatively associated with fresh biomass and growth variables (Fig. 5d). Overall, the PCA of I75 and I50 + I75 followed the same trend as that of I50 (Fig. 5e, f).

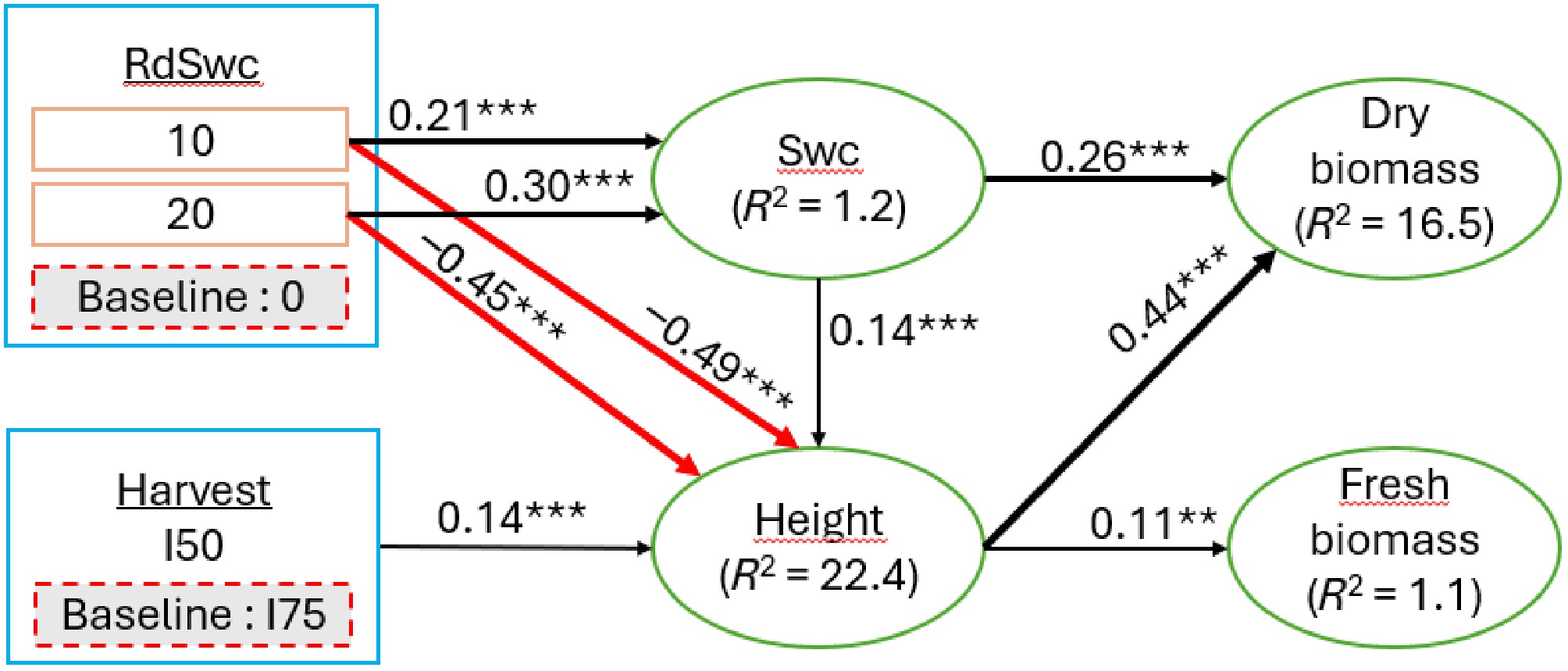

The structural equation model reveals that the radial distance (RdSwc) indirectly influenced dry biomass through a direct positive effect on soil water content (λ = 0.21 and 0.30 for levels 10 and 20, respectively, compared to level zero) and a direct negative effect on height (λ = –0.49 and –0.45 for levels 10 and 20, respectively, compared to level zero) (Fig. 6). Similarly, the harvest intensity indirectly influenced dry and fresh biomass through a direct positive influence on height (λ = 0.14 for I50 compared to I75). The soil water content positively influenced height (λ = 0.14) and dry biomass (λ = 0.26), while height positively influenced dry biomass (λ = 0.44) and fresh biomass (λ = 0.11). Overall, the structural equation model explained 1.2, 22.4, 16.5, and 1.1% of variation in soil water content, height, dry biomass, and fresh biomass, respectively (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Structural equation model showing the underlying mechanism of soil water content, and A. digitata growth parameters and biomass yields under harvesting intensity. The thickness of the path equates to the strength of the path coefficient. Black and red arrows indicate positive and negative paths, respectively. Green color ellipse are response variables; blue color boxes represent the factor, and below each factor is shown its level and the baseline of comparison. The proportion of variation explained by the model (R2) is shown next to each endogenous variable. I50 and I75 are 50% and 75% leaves harvesting intensities, respectively. Asterisks associated to values are the level of significance of the p-value (*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; and * p < 0.05). Chi square = 4.84, p-value = 0.564, degree of freedom (DF) = 6, RMSEA = 0.014, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 1.000. Swc: Soil water content; RdSwc: Radial soil water content.

-

It was found that different harvesting intensities significantly affected the soil water content (p = 0.010), with lower values recorded on the 20th, 21st, 24th, 49th, and 51st DAT. These differences suggest that leaf harvesting can indirectly influence soil water dynamics, possibly through changes in canopy cover and evapotranspiration rates. Although leaf harvesting may not directly alter soil physical properties, it could affect the microclimatic conditions around the plant, thereby modulating evaporation and water retention. Interestingly, these findings contrast with those of Johnstone et al.[32], who reported that soil moisture often remains resilient to variations in disturbance intensity, particularly over short timeframes or under specific ecological conditions. However, in semi-arid environments characterized by high rainfall variability, such resilience may be compromised. The timing of sampling relative to rainfall events appears to be a critical factor, as highlighted by Johnstone et al.[32], and may even outweigh the direct effects of harvesting intensity. In this study, the observed drops in soil moisture likely coincide with inter-rainfall periods, reinforcing the idea that temporal and climatic variables play a dominant role in shaping soil water availability.

Influence of A. digitata leaves harvesting intensity on its growth and biomass yields parameters

-

Plant height increased progressively with no significant difference between the harvesting intensities at any DAT. This finding corroborates the results of Husseini et al.[33], where harvesting regimes did not significantly affect plant height. Similarly, Amagla et al.[34] reported that average plant height increases over time under cutting stress. However, baobab growth rate was higher under I50 than I75, suggesting moderate harvesting intensity promotes better vertical growth. A high remaining leaf area under I50 maintains photosynthetic activity to ensure a steady energy supply for plant growth[35,36]. In fact, greater energy investment in leaf production is required under I75 to the detriment of height and stem diameter growth. I75 likely induces stress from excessive defoliation, reducing carbon assimilation[10,37] and diverting resources toward recovery and defense mechanisms rather than growth[38]. Furthermore, Wahab et al.[39] reported that excessive leaf harvesting can disrupt hormonal signals such as cytokinins and auxins from young leaves, which may reduce cell division, nutrient uptake, root development, and floral organ formation. Bationo et al.[40] also found that harvesting leaves while sparing terminal buds allows the plant to grow in height and promotes vigorous plant development.

Unlike the height, the study found significant differences in stem diameter and leaf number between the two treatments.[33] showed that leaf harvesting at 4 weeks after planting significantly influences stem girth and positively affects mean leaf count. In this study, baobab stem diameter increased progressively and significantly (p < 0.05), as did leaf number (p < 0.001) from the 30th to the 91st DAT, with higher growth rates under I50 than I75. The greater stem diameter and leaf number under I50 reflected the species' ability to sustain both woody tissue production and leaf initiation when defoliation remains moderate. Retaining 50% of the baobab leaf instead of 25% therefore, maintains sufficient photosynthetic activity to support secondary stem growth[41,42]. Additionally, moderate canopy reduction under I50 may improve light penetration and reduce intra-canopy shading compared to I75, thereby favoring leaf initiation and expansion[43]. Conversely, higher harvesting stress under I75 may have forced the plant to allocate most assimilates toward emergency leaf replacement, leaving fewer resources for stem thickening or vice versa[44]. Moreover, the reduced leaf number under I75 limits transpiration-driven nutrient flow, which can further restrict stem diameter growth and leaf production[45]. These findings also align with Amaglo et al.[34], who reported that leaf number and stem diameter in Moringa oleifera increase over time. Husseini et al.[33] also observed that harvesting every 3 weeks results in greater stem girth compared to harvesting every 2 weeks.

The average values of fresh and dry biomass were statistically different on the 30th and 90th DAT for both treatments. These results contradict those of Husseini et al.[33], who reported that harvesting regimes had no interactive effect on baobab leaf yield. This discrepancy may be attributed to the experimental conditions used by Husseini et al.[33] where baobab was grown in pots in a greenhouse and supplemented with various organic and mineral fertilizers. Such a controlled environment and nutrient-rich soil likely dampened the disturbance caused by repeated defoliation, thereby reducing the impact of harvesting intensity. In contrast, the present study was conducted under field conditions, where plants were more exposed to resource limitations and environmental variability. On the 30th DAT, fresh and dry biomass were significantly higher under I75 than I50 (p < 0.01), suggesting that a higher leaf harvesting intensity initially stimulated compensatory growth. This response may have involved the mobilization of plant resources from stem and root tissues for the replacement of removed leaves, resulting in a short-term increase in biomass accumulation[44]. However, this overcompensation was only temporary, as evidenced by the similar fresh and dry biomass values under I50 and I75 at 60 DAT, and the higher biomass under I50 at 90 DAT. This indicates that baobab plants likely depleted their reserves after 60 DAT under continuous high defoliation intensity, thereby reducing the assimilate supply needed for sustained growth. These findings are consistent with those of Hounsou-Dindin[46], who evaluated different harvesting frequencies (12, 22, and 30 d after sowing) on baobab.[33] also reported that the first harvest resulted in a much higher leaf yield than subsequent harvests, indicating that plants produce a large number of leaves during early growth stages.

Dependance among factors and soil water content, A. digitata growth and biomass yields parameters

-

The results from this study also reveal a contrasting dynamic between soil water content and baobab growth parameters. High soil moisture was negatively correlated with plant height, stem diameter, leaf number, and fresh biomass, as confirmed by both correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA); where these growth variables clustered along the first axis in opposition to soil water content. This pattern suggests that excessive moisture does not promote rapid vegetative development in baobab, a species naturally adapted to semi-arid environments[47]. High water availability may have reduced soil oxygen levels, thereby limiting root respiration and nutrient uptake, ultimately hindering stem elongation, leaf expansion, and fresh biomass accumulation[48−50]. Interestingly, while soil water content was negatively associated with fresh biomass, it showed a positive correlation with dry biomass, indicating a physiological shift toward the production of structural components such as cell wall materials and stem fibers rather than soft, turgid tissues[51,52]. This result is further supported by the second PCA axis, where dry biomass and soil moisture aligned together, contrasting with fresh biomass and growth traits. These findings suggest that under higher soil moisture, baobab may prioritize structural biomass accumulation over immediate vegetative expansion, reflecting an adaptive strategy for long-term resilience.

Previous studies have demonstrated that drought-tolerant species such as baobab adopt strategic resource allocation mechanisms to cope with fluctuating water availability in semi-arid environments[53−55]. In the present study, the structural equation model (SEM) reveals that baobab plant height exerted a strong positive influence on dry biomass and a weak effect on fresh biomass, suggesting that vertical growth primarily supports the accumulation of structural tissues. This pattern implies that stem elongation facilitates the development of conductive and supportive tissues essential for water and nutrient transport to expanding foliage and storage organs[56,57]. Additionally, increased plant height likely enhances light interception, thereby boosting carbon assimilation and its subsequent allocation to structural biomass[58,59]. Despite the robustness of the SEM results, it explains only 1.1% of the variation in fresh biomass, compared to 16.5% for dry biomass. This discrepancy underscored the high variability and unpredictability of fresh biomass, which appeared more sensitive to transient environmental conditions and less reliably linked to soil water content or growth traits. In contrast, dry biomass emerges as a more stable and integrative indicator of baobab's resource allocation strategy under variable water regimes and leaf harvesting pressure.

-

This study reveals a differentiated response of Adansonia digitata depending on leaf harvesting intensity, distinguishing the moderate (I50) from the severe (I75) treatment. Growth indicators (number of leaves, stem diameter, and plant height) were significantly higher under I50 between 60 and 90 d after transplanting (DAT). This trend was confirmed for both fresh and dry biomass yields, which were also greater under I50, particularly at 90 DAT. Soil water content showed a negative association with immediate growth and fresh biomass but a positive association with dry biomass, suggesting that water availability moderates the balance between rapid growth and structural development. Dry biomass thus emerged as a more stable and reliable indicator of resource allocation under fluctuating conditions, and harvesting intensity directly shapes the balance between growth, water use, and biomass yield. A major shortcoming of this research lies in the lack of data from an unharvested control group. This absence of an external reference point has forced the interpretation of differences between I50 and I75 to be strictly comparative, and prevents the assessment of the net and absolute impact of defoliation on the plants' maximum growth potential.

Despite the above-mentioned limitation, the conclusions have significant practical and policy implications. For farmers, moderate harvesting is the recommended approach to optimize productivity and resilience, favoring the sustainable integration of baobab into local vegetable systems to enhance food security. For policymakers, these findings support the development of agroforestry programs promoting controlled harvesting and highlight the need to invest in soil and water management. Finally, for researchers, it is recommended that future studies explore the long-term effects of repeated harvesting and the potential role of soil nutrient enrichment in modifying the defoliation response, in order to design sustainable management practices that reconcile harvesting benefits with conservation goals.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zakari S, Tovihoudji PG; formal analysis, data curation, draft manuscript preparation: Boukari SA, Yessoufou MWA, Zakari S; writing − review and editing: Tovihoudji PG, Dossa GGO, Akponikpè PBI; supervision: Zakari S, Akponikpè PBI; funding acquisition: Zakari S, Dossa GGO. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data will be made available upon a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

-

We acknowledge the Alliance of National and International Science Organizations for Belt and Road Regions (ANSO) for providing desk and facilities that helped to validate the data used in this paper through data analysis and manuscript writing, funded by CAS-ANSO Fellowship (Grant No. CAS-ANSO-FS-2025-47).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Sissou Zakari, Sékaro Amamath Boukari

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zakari S, Boukari SA, Tovihoudji PG, Yessoufou MWIA, Dossa GGO, et al. 2026. Leaf harvesting intensity alters growth and functional traits of baobab (Adansonia digitata) in semi-arid West African systems. Circular Agricultural Systems 6: e001 doi: 10.48130/cas-0026-0002

Leaf harvesting intensity alters growth and functional traits of baobab (Adansonia digitata) in semi-arid West African systems

- Received: 31 August 2025

- Revised: 06 December 2025

- Accepted: 11 December 2025

- Published online: 19 January 2026

Abstract: Baobab (Adansonia digitata) is a major species used against malnutrition and food insecurity in Africa. However, its population's sustainability is threatened by low natural regeneration and intensive exploitation of its parts for subsistence and commercial purposes. This study used a randomized complete block design to assess whether the intensity of leaf harvesting from baobab seedlings alters the growth and functional traits of baobab in semi-arid systems. Leaf harvest stress was applied with two levels: I50 (50%) and I75 (75%) from 30 to 90 d after transplanting (DAT). The results show that soil water content (SWC) significantly varied between harvesting intensities, among DAT, among radial distances (Rd), and for the interactions I × DAT and Rd × DAT (p < 0.001). The SWC was 0.52% lower under I50 compared to I75. Baobab growth parameters and biomass increased with rising DAT, with the highest average rate under I50. The leaf count and height significantly differed among DAT (p < 0.05), with a higher average growth rate of leaf count under I50 (62.1%). The average fresh biomass was 3.90% lower under I50 than under I75, and the dry biomass was 3.83% lower. Under I50, the soil water content correlated negatively with height, stem diameter, number of leaves, and fresh biomass, but positively with dry biomass. Given that 75% defoliation at 30-d intervals yielded optimal fresh leaf production, this harvesting regime is recommended for commercial baobab leaf production systems. However, long-term studies are required to assess the sustainability of this practice and its effects on plant resilience under fluctuating environmental conditions.

-

Key words:

- Soil moisture /

- Leaves biomass /

- Legume production /

- Food security /

- Baobab seedlings