-

Unplanned wildland fires have the potential to inflict major, long-lasting effects on highway transportation infrastructure systems. As a result, it is crucial to identify and assess the risks and possible damage posed by these wildfires. A significant change in the global character of wildland fire in recent decades is the increase in high-intensity wildfires described as 'megafires'. The rise of megafires – categorized as more than 100,000 acres (> 40,000 ha) on public lands in the American West and other regions have signaled an epidemic of conflagrations that is being caused by changes in climate, land use, and human fire habits[1]. A recent study[2] notes that exceptionally large megafires are now known as gigafires (> 100,000 ha) and terafires (> 1,000,000 ha).

Megafires are sometimes viewed as natural events exacerbated by human mishandlings such as a botched operational reaction, or the result of some kind of bureaucratic mismanagement, but specific causes are often unclear[3]. Megafires can occasionally consist of a collection or 'complex' of interconnected wildfires spanning a huge geographic area[2]. The extent and quantity of available fuel, weather extremes, and the depth of the drought can extend and prolong the expenses, losses, and damage that accompanies them[3]. Three kinds of megafires are recognized: a) short-term (one-two days), b) long-term (several days or even weeks), and c) hybrid (short-term that reaches long-term in one-two days), with each having different supporting fire conditions based on daily fire progression when studied across the plains in Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, and New Mexico in the USA[1].

Data on historical fire activity, fuel availability, climatic and meteorological trends, and other factors can be used to estimate the likelihood of a given area experiencing a wildfire and its given intensity, even though the location and timing of wildfires cannot be predicted.[4]. It is imperative to apply the insights gained from previous experiences, along with increased comprehension of landscape vulnerability and fire consequences, to enhance the assessment of wildfire risks, encourage proactive fire management, and eventually prevent megafires[5].

The area where dwellings meet wildland vegetation is known as the wildland-urban interface (WUI). Human life and property near the WUI are most at risk from wildfires, including megafires, because of the close proximity of flammable vegetation[6]. One study[7] noted that up to 14 million acres of non-industrial forests were converted to urban usage between 1952 and 1997 in the USA By 2050, the percentage of urban land is anticipated to rise from 3.1% to 8.1% in the USA[8], potentially affecting an area of about 392,400 km2 or 96,964,152 acres[7]. When assessing management and policy actions, it is critical to understand how and why the WUI is growing. Fuel treatments and the promotion of fire-adapted communities in the WUI are prioritized under federal wildfire control policy in the USA[9]. The amount of literature on wildfires in the WUI globally suggests an increasing interest in this hazard. Evaluation methodologies have been assessed using key ideas concerning intrinsic characteristics and wildfires in the WUI, while analyzing several risk prevention and reduction programs created in the WUI affected by forest fires in various parts of the world[10].

The Labor Day Fires of 2020

-

The 2020 Labor Day wildfires that occurred in the US states of Washington (WA), Oregon (OR), and California (CA) burned nearly 3.5 million acres (1.4 million ha)[7,8,9] over 15 d, 117 d, and 112 d respectively, resulting in huge expenses for reopening vital roadway infrastructure and losses from reduced commerce and tourism. Several factors, including fuel dryness, lack of precipitation, unusually warm weather, low relative humidity, unusually brisk northerly or easterly winds, and most notably, extreme droughts of recent decades, contributed to the fires' start and growth[10]. The occurrence of a quick, intense drying period and an east-wind, regional event that coincided with several ignitions was the primary distinction between the 2020 flames and earlier modern fires[11]. An interesting sequence of weather conditions played a large part in maintaining their ferocity[7].

Serious health consequences from both short-term and long-term exposure to poor air quality are negative outcomes of large wildfires, including those of Labor Day 2020. Although investigations on the health impacts of wildfire particulate matter (PM) has increased recently, data availability continues to be a significant limitation of these studies. Since it can be challenging to distinguish PM from other sources from PM coming from wildfire smoke, quantifying exposure levels is arduous when performing epidemiological analyses of health impacts related to wildfire smoke[12]. A study of the 2020 fire season suggests agricultural laborers in CA who worked outdoors most of the time may have been exposed to dangerously high amounts of PM2.5 smoke pollution, particularly in the Central Coast and Central Valley[13]. Old wood smoke carried from the 2020 Labor Day wildfires in OR and CA, as well as the ongoing wildfires in WA were used to calculate relative spatial distribution and amount of the health effects on the populace of elevated PM2.5 concentrations caused by the wildfires[14].

In part because of the health effects, the wildfire Economic Recovery Council was assembled in OR, with responsibilities including: a) evaluating the effects of the fires on the community and economy and determining the need for assistance; b) organizing community needs and removing obstacles in collaboration with council agencies; c) directing concerns to the Governor's disaster cabinet; d) determining the budgetary and policy requirements for wildfire economic recovery for the 2021 legislative session; e) collaborating with regional solutions teams to organize state agency resources to mitigate the effects of the fires and support public safety, economic stability, and natural resource recovery (in collaboration with local and federal partners); and f) notifying the Governor of any additional requirements[15].

Problem statement

-

Although current research on the relationship between wildfire behavior and various factors, such as topography, climate and weather, land use, and cover, socioeconomics and demographics, fuel treatment, other wildland/WUI management interventions, law enforcement, and locational characteristics, is fairly extensive[16], it ignores how vulnerable transportation infrastructure is to wildfires. A database that monitors the effect of wildfires on infrastructure, such as electrical lines, roads, and pipelines, is also lacking[17], despite an estimated US

${\$} $ The research approach is to: a) ascertain why highway infrastructure damage from megafires is increasing by examining the history of megafires in three western coastal states in the US and the relationship to highway damage caused by them, and b) evaluate the damage to the highway infrastructure of WA, OR, and CA resulting from the 2020 Labor Day wildfires. The objective is to support local, state, and federal governments in developing emergency and budgetary planning for wildfire damage.

Each state's history of megafires was captured along with the various characteristics associated with each wildfire (Supplemental Table S2−S7). This data collection is followed by a summary of the 2020 Labor Day megafires and the subsequent highway damage that each state recorded (Supplemental Table S8). This analysis facilitates the assessment of damage to roadways based on wildfire size and the length (km) of the impacted roadway.

WA, OR, and CA were selected because of their consistent vulnerability to wildfire threats. The WA analysis includes two of the four regions for the regional vulnerability assessment of the WA Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan[28]. The OR analysis covers five of the eight OR Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan[29] risk assessment regions, and the 23 CA counties included comprise the risk assessment zones of the CA Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan[30]. Each roadway impacted by wildfires in these regions was assessed regionally and classified based on an analysis of the effects on the roads in relevant regions/counties within the three states' Hazard Mitigation Plans.

-

Historical megafire data, including the year, hectares burned, the reported cause, the description/location of the fires, and the various highways impacted were compiled for the 17 megafires that were reported in WA between 1902 and 2020, the 36 megafires that were recorded in OR between 1845 and 2022, and the 21 megafires that were recorded in CA between 1889 and 2021 (Supplemental Table S2−S7). Summarized breakdowns from the 2020 Labor Day wildfires were generated from the Detailed Damage Inspection Reports (DDIRs) from the WA State Department of Transportation (WSDOT; Supplemental Table S9−S11) and the OR Department of Transportation (ODOT; Supplemental Table S12−S15), and from the Damage Assessment Reports (DARs) from the CA Department of Transportation (Caltrans; Supplemental Table S16 & S17), including physical and financial roadway damage. All sources were missing statistical data in one form or another, which made the comparative analysis challenging. Each cost impact was itemized, with additional detailed on-site location as well as a description of the damage. The data received were in standard units and preserved as such in the supplemental tables but were later converted to metric units.

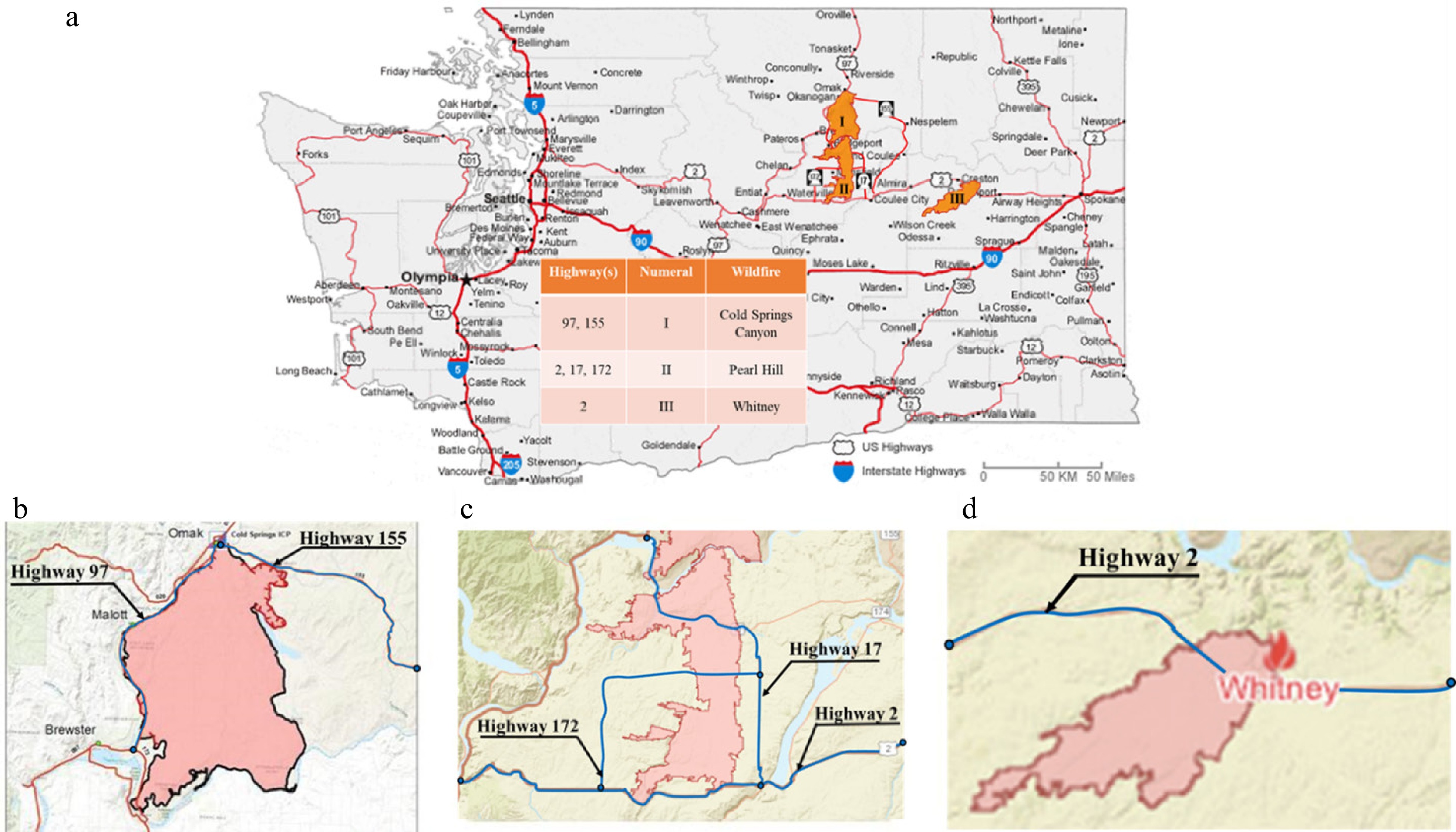

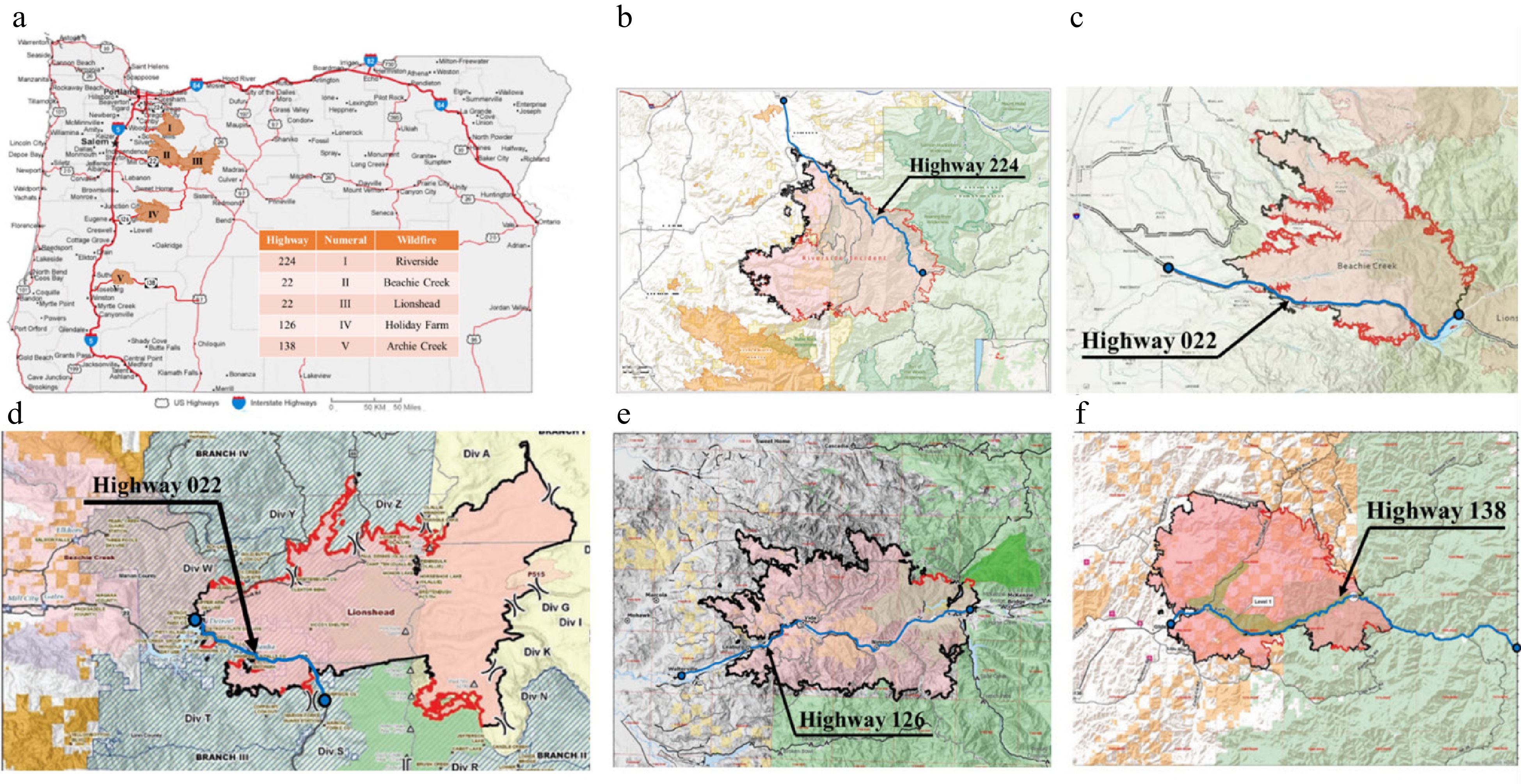

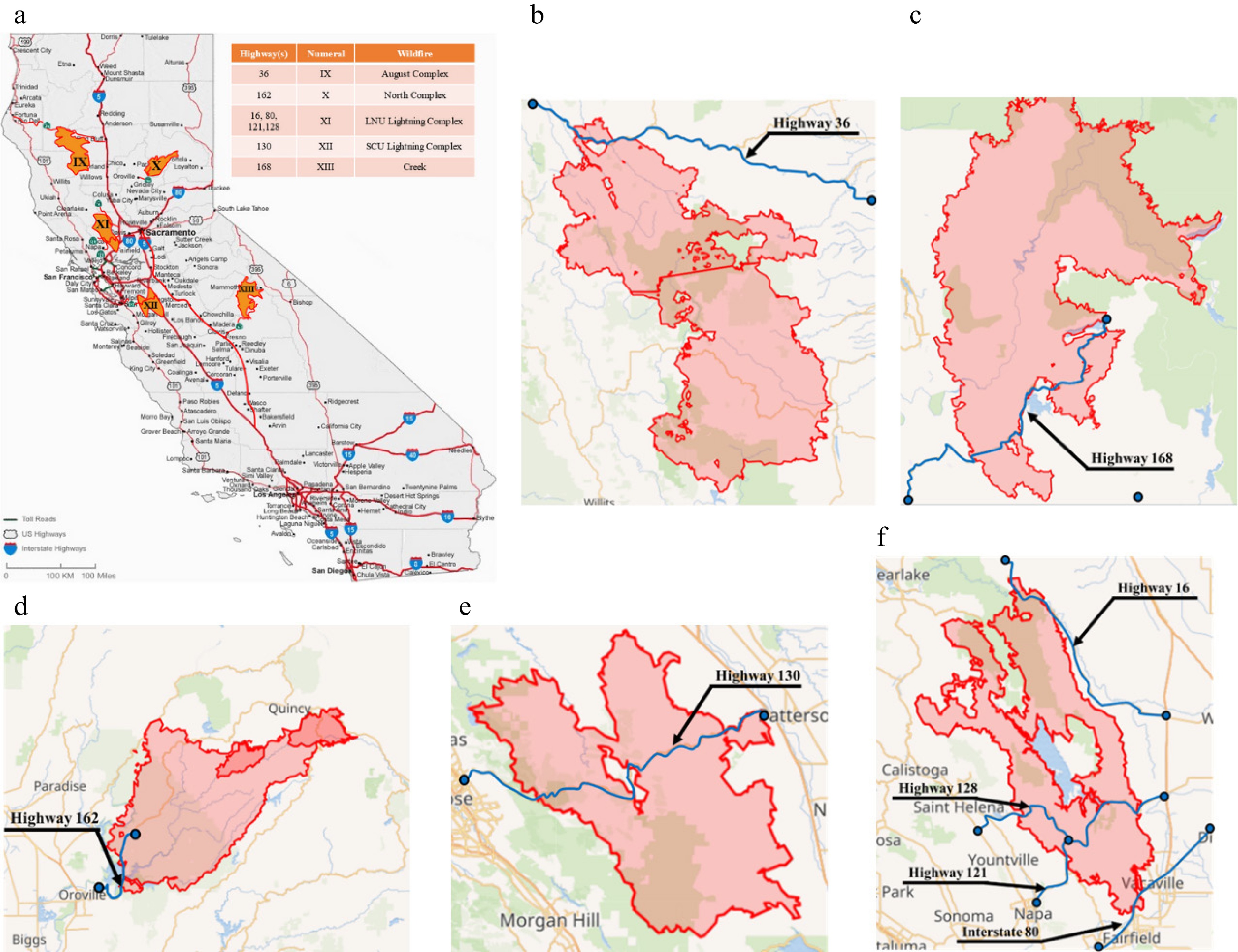

The highways in each state that were investigated along with the wildfires that affected them are shown in Figs 1−3, and Supplemental Table S18 summarizes the routes and wildfires. To reveal more about the completeness and accuracy of the information in the DDIRs and DARs, local emergency managers across all three states were contacted to clarify the tools, processes, and approaches used in the compilation of the reports. These contacts resulted in several referrals, strings of email correspondence with local emergency managers, and further questions by telephone.

Figure 2.

(a) Location of 2020 Labor Day wildfires in OR[34]. (b) Location of Highway 224 within the 2020 Riverside wildfire[35]. (c) Location of Highway 22 within the 2020 Beachie Creek wild.fire[36]. (d) Location of Highway 22 within the 2020 Lionshead wildfire[37]. (e) Location of Highway 126 within the 2020 Holiday Farm wildfire[38]. (f) Location of Highway 138, within the 2020 Archie Creek wildfire[39].

Figure 3.

(a) Location of 2020 Labor Day wildfires in CA[40]. (b) Location of Highway 36 within the 2020 August Complex wildfire[41]. (c) Location of Highway 168 within the 2020 Creek wildfire[42]. (d) Location of Highway 162 within the 2020 North Complex wildfire[43]. (e) Location of Highway 130 within the 2020 SCU Lightning Complex wildfire[44]. (f) Location of Highways 16, 80, 121 and 128, within the 2020 LNU Lightning Complex wildfire[44].

Data analysis

-

Characterization of historical highway damage from megafires in WA, OR, and CA over the last 100+ years were first analyzed to determine whether any relationships exist between size, causes, or locations of the wildfires vs damage to highway infrastructure. Scarcity of historical categorization of roadway damage made comparisons to the 2020 Labor Day wildfires impracticable, with WA only identifying one previous megafire in 2014 – the Carlton Complex being recorded for federal reimbursement, but without any infrastructure damage specifically called out or recorded. OR only identified two previous megafires in 2015 – the Canyon Creek Complex and the Cornet-Windy Ridge, which only recorded hazard tree damage, while CA is so familiar with wildfires, that they weren't sure when they began keeping records of highway damage due to wildfires – which is believed to be sometime in the 21st century. Roadway impacts to the highways due to the 2020 Labor Day wildfires include the costs of hazard tree removal; slope/scaling damage from rocks, dirt, and debris that slid onto the road; traffic control required; and structural damage that required repair along the highways. Evaluation of the overall damage to highways in these states during the 2020 Labor Day wildfires included considering the area burned, causes of the wildfires, and any discernible pattern in relation to highway damage and the subsequent cost impacts.

Data processing

-

In addition to investigating the historical megafire data, highway damage data for highways affected by the 13 megafires that occurred during the 2020 Labor Day wildfires were analyzed to generate baseline information related to the damaging impact to the roadways. The locations of the highways within the wildfires within each state were also reviewed and discussed in relation to the amount of damage incurred.

-

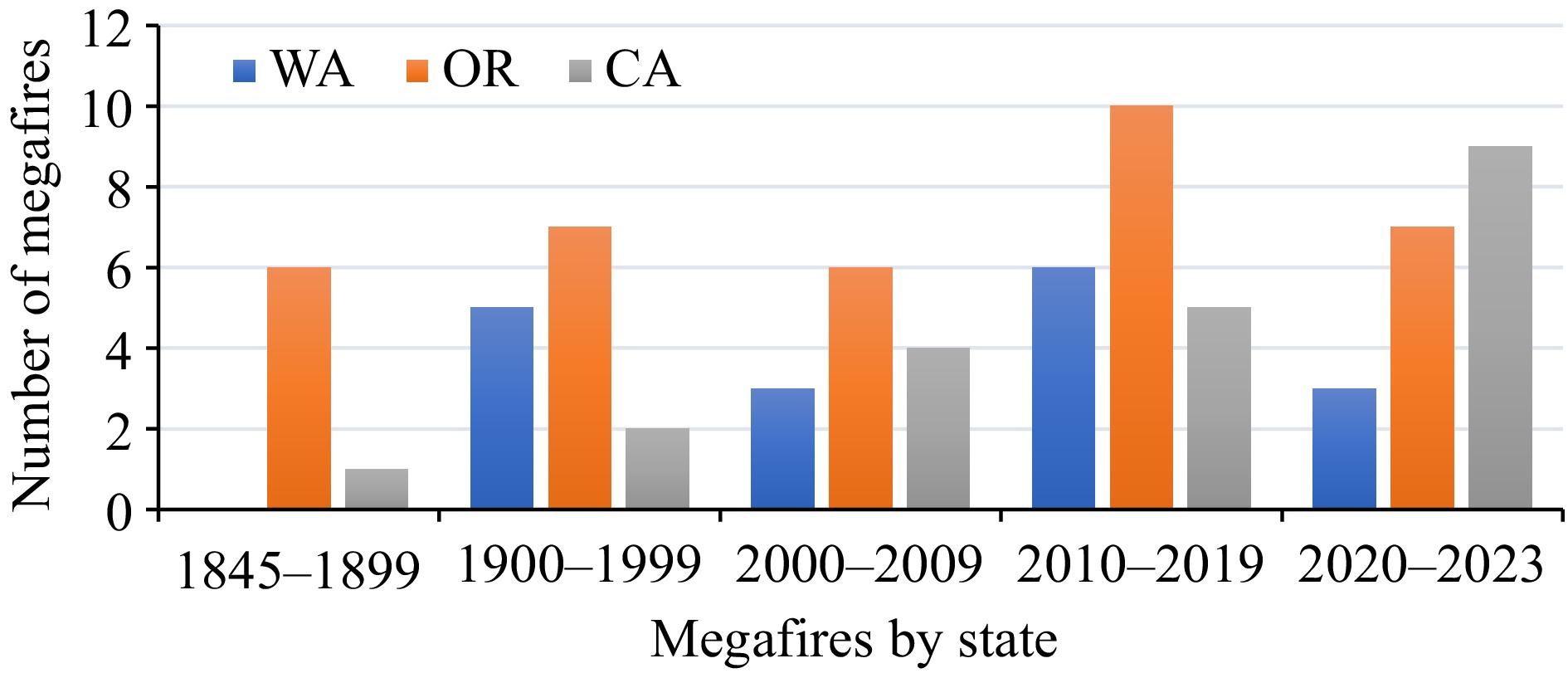

The number of megafires recorded in each state for the past 100 plus years is shown in Fig. 4. The first decade of the 21st century had nearly as many megafires as the entire 20th century. WA experienced 71% of its megafires in the first three decades of the 21st century, with OR enduring 64% and CA experiencing 86% (Supplemental Table S2−S7). Cumulatively the three states experienced 72% of their megafires during the 21st century – through 2023.

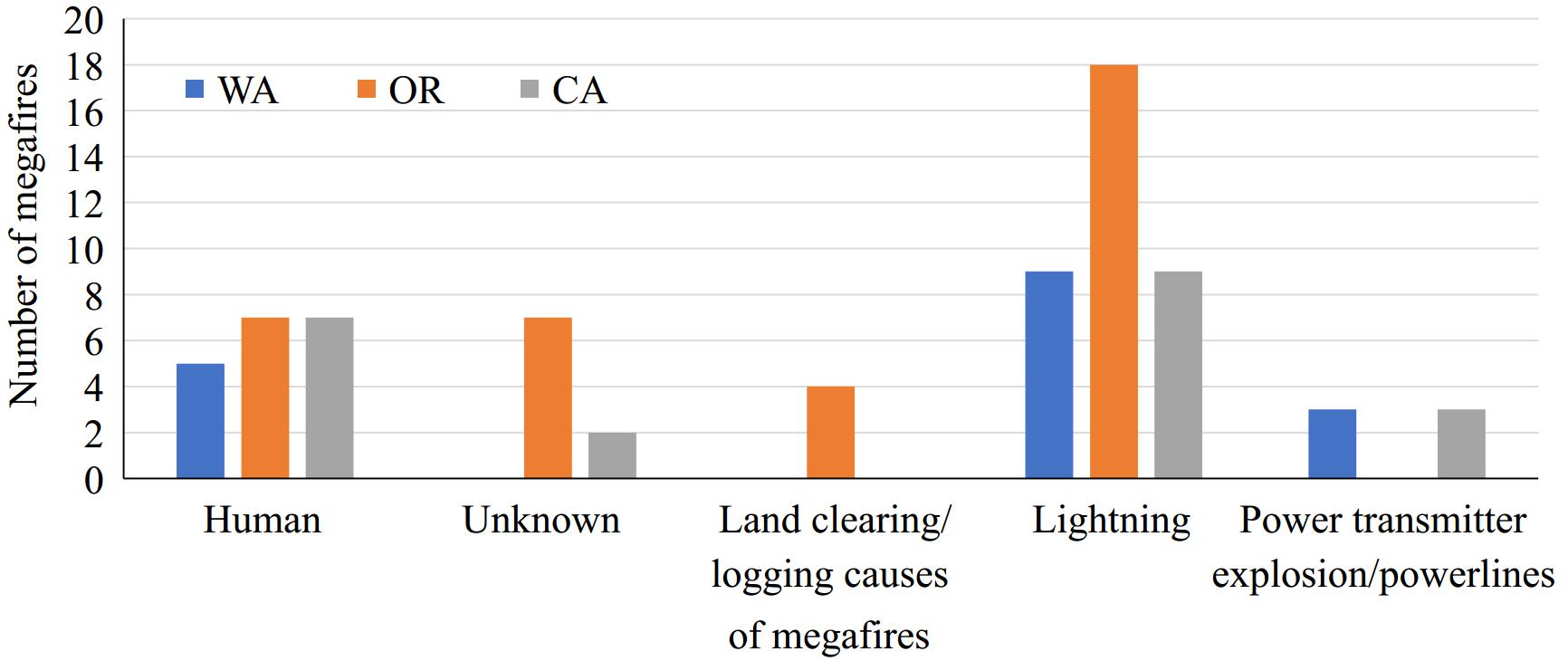

Not surprisingly, lightning is the leading cause of the historical megafires in WA, OR, and CA (Fig. 5; Supplemental Table S19). Of the 74 megafires recorded over the three states' history, 49% were caused by lightning, with 26% caused by humans, 12% by unknowns, 8% by power transmitter explosion/powerlines, and 5% by land clearing/logging (Supplemental Table S19). Of these, the causes of the wildfires in the 19th century were either human or unknown and only occurred in OR and CA, with no roadway damage noted. In the 20th century, 1,069,527 ha (2,642,859 acres) burned, with lightning, unknowns, logging/land clearing, and humans being the causes of the wildfires, without roadway damage being recorded (Supplemental Table S20). Only since the start of the 21st century have power transmitter explosions/powerlines come into play as a cause of the megafires in these states.

Only by the second decade of the 21st century were the megafires reported to have caused significant damage to highways. megafires burned 2,958,600 hectares (7,310,860 acres) (Supplemental Table S2, S3, & S7) in the 19th and 20th century without any roadway damage being recorded. A total of 5,434,331 ha (13,428,524 acres) burned since the start of the 21st century (Supplemental Table S2, S4−S7), with roadway damage only being reported on a few of the megafires in each state.

Due to the overall lack of documented historical infrastructure damage from megafires, to determine which types of megafires cost the most amount of damage to highway infrastructure we evaluated the megafire data and the financial damage to highway infrastructure reported from each state from the 2020 Labor Day wildfire event. wildfires started by lightning (49%) appear to have caused the most damage to highway infrastructure (Supplemental Table S2, S5−S7) followed by those caused by humans (30%), unknown (19%), and finally power transmitter explosion/powerlines (2%; Supplemental Table S9−S17). The locations of the megafires within each state seem to have little relationship to the amount of damage sustained on each roadway impacted.

The 2020 Labor Day wildfires along the Pacific coast

-

The three Labor Day megafires in WA, five in OR, and five in CA collectively burned 1,559,351 ha (3,853,240 acres; Supplemental Table S8) with roadway damage being documented. These wildfires impacted an unprecedented 18 different highways throughout the three states simultaneously. Lightning was the leading cause of the fires, followed by powerlines, power transmitter explosions, and humans (Supplemental Table S8). The WA megafires were all caused by powerlines and power transmitter explosions. The causes of megafire in OR were a combination of lightning, unknowns, and humans. Four of the CA megafires were the result of lightning, with one being caused by unknowns. CA megafires burned nearly twice as many hectares – 1,008,202 (2,491,321 acres) – as WA and OR combined – 551,149 ha (1,361,919 acres) though the CA land area (42,397,069 ha) is almost the same as that of OR and WA (25,381,883 and 17,207,233.00 ha) combined. Just under 5% of all three states' land area was on fire during the 2020 Labor Day holiday. The number of hectares burned by cause in the 2020 Labor Day wildfires is shown in Supplemental Table S21.

Four of the six roads were in the middle of two of the WA megafires, while the remaining two were on the outskirts of the third megafire (Fig. 1). All four of the highways were in the middle of the five OR megafires (Fig. 2). Figure 3 indicates that three of the eight highways were situated on the edges of two of the megafires in CA, while five of the eight routes were in the center of four of the megafires.

Cost impacts to highways from 2020 Labor Day wildfire event

-

To analyze each impact comparatively by state, consideration must be given to the fact that some damage may have gone unreported. For example, hazard tree removal costs were unreported in WA, while an estimated 15,214,000 and 15,214,000 and 9,030,310 in estimated hazard tree removal costs were reported in OR and CA, respectively (Supplemental Tables S12 & S16). Slope-rock scaling estimated costs went unreported in CA but totaled 17,508,161 and 17,508,161 and 26,940 in OR and WA, respectively (Supplemental Table S9, S13). The CA Labor Day fires incurred the highest cost for structure repairs at 34,427,936, followed by OR at 34,427,936, followed by OR at 7,264,340 and WA at 1,309,364 (Supplemental Table S11, S14, & S17). Estimated traffic control costs were unreported in CA, but estimated costs in OR were 1,309,364 (Supplemental Table S11, S14, & S17). Estimated traffic control costs were unreported in CA, but estimated costs in OR were 3,172,310 and those in WA were only US

${\$} $

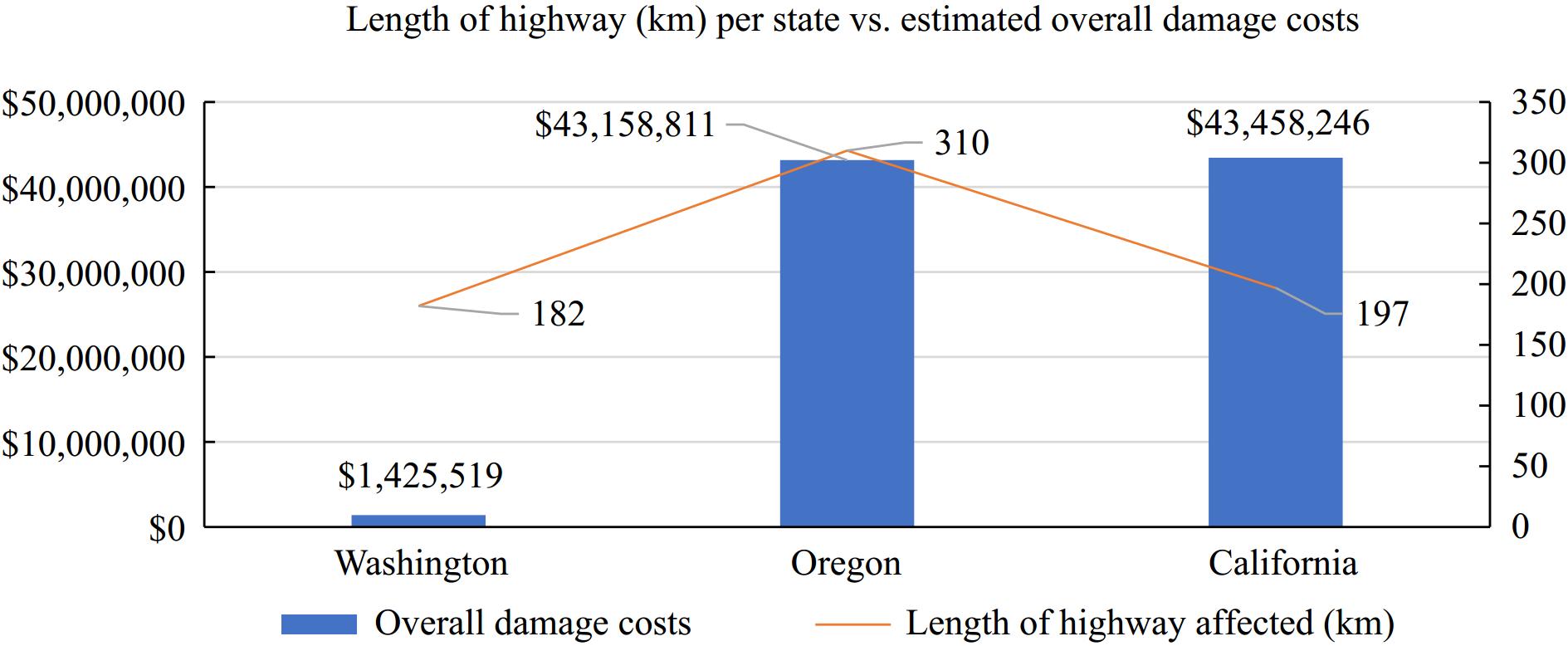

Figure 6.

Length of highway (km) per state vs estimated overall damage costs due to the 2020 Labor Day wildfires.

One noteworthy finding is that overall damage costs in CA substantially exceeds those in WA (Supplemental Table S22) even though similar lengths (within 15 km or 8%) of highway were affected. Supplemental Table S8 identifies some potential reasons for this significant expense difference including a) the number of megafires in each state (5 in CA vs 3 in WA), b) average duration (number of days) of each state's megafires (80.6 in CA vs 12.7 in WA), c) number of highways affected (8 in CA vs 6 in WA), and d) the average number of hectares burned in each state (201,640 in CA vs 72,989 in WA). Expenses were likely higher in CA despite a similar number of highway miles affected because there were more megafires on more roadways over more days, and notably more hectares burned.

Another important finding is that the total cost impacts are almost identical for CA and OR, at over 43 million each, while cost in WA totaled slightly over 1.4 million. The different lengths of highway affected between OR (310 km) vs that in WA (182 km) and CA (197 km; Supplemental Table S22) complicates the comparison of cost vs length of highway affected. Using Supplemental Table S8 again, we associate some possible explanations for these substantial expense differences that include a) the number of megafires in each state (5 in CA and OR vs 3 in WA), b) average duration (number of days) of megafires (80.4 in OR and 80.6 in CA vs 12.7 in WA), c) number of highways affected 4 in OR and 8 in CA vs 6 in WA), and d) average number of hectares burned (66,436 in OR and 201,640 in CA vs 72,989 in WA). Thus, WA experienced much shorter and fewer megafires. However, no direct relationship is apparent in this very small sample size between the length or location of the highway impacted and the overall estimated damage costs.

-

Along the West Coast, destructive megafires are becoming more common, with similarly disastrous effects on highways. Labor Day, September 7, 2020 – began with scorching, dry, hurricane-force easterly winds that fueled flames in WA, OR, and CA, igniting megafires that broke previous wildfire records. The current study represents the first empirical effort to assess the impact of megafires and their subsequent destruction of highways that can advance theoretical and practical knowledge of meg afires and their destructive capacity to highway infrastructure.

To determine why highway infrastructure damage from megafires is increasing we looked at the history of megafires in the three western coastal states in the US and the relationship to highway damage caused by them. megafires were documented in OR and CA during the 19th century and not surprisingly without any highway damage being noted, probably because few highways had been established by that time. The reasoning behind this lack of documentation during the 20th century includes a) the roadway networks were only beginning to be built, b) each state's Department of Transportation (DOT) was just beginning to be established (WA in 1905, OR in 1913, and CA in 1910), and c) federal government agencies were established only by the second half of the 20th century: the US Department of Commerce was established in 1903, but only became the Government's principal transportation agency in 1950, while the Federal Highway Administration (FHA) was established in 1967 and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) debuted in 1979. Before the 2020 Labor Day wildfires, WSDOT had only submitted one request to the FHA for financial reimbursement due to highway damage from wildfires in 2014, while ODOT had only submitted two requests to the FHA for financial reimbursement due to highway damage in 2015. Caltrans representatives expressed uncertainty regarding when the office started requesting financial reimbursement from FHA but indicated that they started keeping track sometime in the 21st century. While Caltrans has not specifically captured roadway damage directly as it relates to wildfires, a recent research project developed by UC Davis was created to assist Caltrans in its efforts to do a wildfire susceptibility risk assessment for fuel reduction in their right-of-way alongside their highways. Their findings support the evaluation of infrastructure risk, which can be utilized to rank places for treatment, provide a method for monitoring regions that have been treated and have had their risk reduced over time, and involve local governments and wildfire fighting units in the coordination of landscape fire risk reductions[45].

Plausible factors that influence roadway damage from megafires are the result of a century of fire exclusion policies, increased fuel loading, the lengthening of the 'fire' season—the annual period during which vegetation fuels are susceptible to combustion—increased tree mortality and shifting topography/terrain. While these large-scale wildfires are associated with dry, easterly winds and concurrent drought, the regionally distinct patterns of wind, fuel, fire size, and drought in the 2020 event point to a more complex mechanism than the mere coincidence of wind and drought[11]. A more complex 'recipe' for major westside flames than just wind and drought happening at the same time includes the presence of mountainous areas and valley margins that appear to have affected fire growth and spread. The variation in fire size appears to be partially explained by geographic patterns of wind speed and drought[11]. The general public generally agrees that the main reason for this rise in megafire incidents is climate change, which involves increased human activity and affects drought and extreme heat events.

In addition to the statistical data gathered and examined (Supplemental Table M) to assess the damage to the highway infrastructure of WA, OR, and CA resulting from the 2020 Labor Day wildfires, multiple interviews were held with personnel from each state to enhance the understanding of the impacts of the megafire to their highway systems.

Interviews with WSDOT emergency personnel indicated a focus on the post-fire activities associated with debris flows (slides) and plugged ditches (flooding), which are both attributed to continuous proper maintenance throughout the year. Structural damage seems to be their biggest expense (Supplemental Table S11), but they work with the WA State Department of Natural Resources as well to identify and predict post-fire slide areas along roadways. Replacement of wooden guardrail posts with metal posts is likely to increase resiliency but is expensive and time-consuming to implement. Another resiliency task related to maintaining the highways is removing more hazard trees from around the roads before a megafire. Such actions are currently taking place in the medians of many highways in OR. WA does not maintain a disaster budget and therefore must deal with natural disasters like megafires with the state's funds until they initially assess and provide FHA with the characterizations of the damage and the estimated costs. Once the financial threshold limit has been met for funding, FEMA can then be engaged, and additional financial resources can be requested as well. Another item that stood out during the interviews is that planning too often fails to provide conclusive answers, with success dependent on the extent of the disaster as well as the topography, weather, and elevations of the disasters.

Based on an assessment of interviews among the three states, OR appears to have had the most challenges with dealing with the megafire disasters, simply because they had never encountered the magnitude of facing five megafires simultaneously throughout the state and the amount of destruction that they caused so quickly. In addition, there were already numerous smaller wildfires occurring throughout the state that firefighters and emergency personnel were already battling when the Labor Day wildfires hit. While interviewing ODOT personnel, who participated in the emergency recovery and response effort throughout the state, it was evident that OR was unprepared for such a natural disaster or the amount of devastation it caused. Since OR officials were inexperienced with a wildfire catastrophe of this scale, they chose ODOT to handle the overall recovery operation whether it was related to roads and highways or not, to utilize their experience with handling the response and recovery effort similar to their capital improvement plan (CIP) contractual process. ODOT did reach out to Caltrans for ideas and assistance since they were more acquainted with this type of natural disaster and how to approach the response and recovery operations the most efficiently. The delivery and operations division within ODOT led the work during the response and recovery operations during the megafires throughout the state. The state of OR does maintain a bi-annual contingency budget at the statewide level and each of the five ODOT regions maintain a small budget for emergencies as well, but none were even remotely adequate to address a natural disaster of this magnitude. The emergency operations group within ODOT undertook the challenge of clearing and cleaning up debris from the highways as well as assisting FHA and FEMA in recovering financially from the wildfire disasters. This included ODOT staff first going out to the roads that were being affected and determining how fast they could either get the roads back open and/or what it would take to get the roads opened safely. This was only the first step in the process and the unbudgeted costs incurred here were borne by the state initially. The second step involved completing the DDIRs for FHA. The third step was requesting funds from FEMA, which required additional documentation related to the damage and much more detailed cost data information. Long-term impacts from these wildfires on the highways that ODOT is continually upgrading include a) pavement damage, which involves early cracking from additional heavy equipment on the roads; b) unstable slopes, drainage issues, clearing ditches, and c) removing hazard trees before they become another problem.

Impressions of the interviews indicated that CA officials seem to have the best handle on how to deal with natural disasters, not only because the state maintains a disaster budget, but also because during the interviews it was apparent that they are so accustomed to fires that the 2020 Labor Day event seemed rather unextraordinary. The state of CA maintains an annual reserve set aside for natural disasters, which includes wildfires consisting of hundreds of millions of dollars, which the CA Transportation Commission (CTC) can increase if they deem necessary. Six response/recovery branches within the Office of Emergency Management Division of Maintenance throughout the state collaborates with a specific wildfire task force that continuously works on wildfire preparedness, and they also work with the Office of Vegetation and wildfire Management extensively. On the day when a wildfire starts, Caltrans completes a preliminary major damage assessment (PMDA) form, which then goes through the CA Governor's Office of Emergency Services (Cal-OES) and then onto the federal government. The two avenues of revenue include: a) FHA, with funding initiated by the Governor's state of emergency declaration; and b) FEMA, with funding initiated by a Presidential state of emergency declaration. Caltrans typically only seek reimbursement from the federal government when it makes sense, as disaster funding is built into their annual budget. Caltrans described the same scenario as the WA officials – specifically, that planning cannot anticipate where a disaster will strike or how extensive it will be.

Given the increasing frequency of destructive megafires in the three states and the ensuing destruction and financial effects on highways, the data produced by this work enables the identification of specific highway damage areas and provides a quick and efficient way to estimate the overall financial damage ramifications for local, state, and federal agencies, particularly FEMA and FHA. Some of the challenges encountered in this study included obtaining the research data in the first place, identifying, and decomposing the data into distinct features, and realizing that a large portion of the financial and physical damage data provided for each wildfire was consistently lacking.

As with any research, caution should be exercised in the interpretation of results because of several limitations in the research. Most prominently, data availability continues to be a significant limitation. Although the three states' historical megafire data was examined, and plausible explanations for the 21st century's spike in wildfire activity were assessed, focusing just on megafires may have overlooked additional state-wide highway damage caused by lesser wildfires.

Future research must address these limitations despite the practical benefits of these results. Analysis of additional routes impacted by wildfires that may be smaller in size than megafires within a given geographic area should be part of future research. The positioning of the highways with respect to the size (in hectares burned) of the wildfires constituted another constraint. It could be helpful to conduct additional research to ascertain the extent of financial harm that roadways sustain based on their placement in relation to the wildfire center.

While each state recorded the highway damages and estimated costs, some interpretation was required to align the various damages and their corresponding costs. Data from the DDIRs and DARs were absent for each of the distinctive features examined in the study (hazard trees, slope-rock scaling, structures, and traffic control impacts). Further data in each of these categories would be beneficial for future research.

To prepare for and manage wildfire catastrophes, transportation authorities must understand both the financial and physical components of the damage to the transportation network. Studies of the economic repercussions of catastrophic wildfires must be comprehensive and cover all economic components to have a good knowledge of the true impact of large wildfires, which often exceeds the usual impact indicators. Our work aims to give emergency planners, regardless of their background in transportation, at agencies like WSDOT, ODOT, Caltrans, and other governance emergency management organizations – FHA and FEMA – a clear and concise set of information regarding not only the obvious increase in megafires, but more specifically the physical and financial devastation caused by megafires during the 2020 Labor Day wildfires along the US Pacific coast. The findings will help identify and assess highway damage as well as guide future infrastructure expenditures.

These findings point to the notion that the construction of a standardized, centralized, nationwide database tracking system for reporting the damage from wildfires seems to be sorely needed. Such a database would be similar to that used by the LAHM online portal for recording data on flood-mitigated buildings in Louisiana[46].

-

To analyze the history of megafires and their impact on the financial and material harm to highways during the 2020 Labor Day wildfires in WA, OR, and CA, this research compiled and examined all the available data. There is sufficient evidence to back up the evaluations and predictions made by practitioners regarding the devastating consequences of megafires on roadways, even though the results indicate a weak or nonexistent association between the amount of the wildfire's damage and the highway's damage expenses. The challenge of correlating the amount of wildfire and highway damage includes a) incomplete damage data, b) sheer lack of damage data, and c) deficient literature concerning analysis and methodologies related to highway damage from wildfires. While the analysis pinpointed the highways position within the various megafires, the topography and terrain surrounding each one wasn't specifically ascertained, while rural vs urban areas should also be investigated further to identify potential similarities between locations of damage. Another avenue of examination to be researched further would be to become involved in the damage assessment endeavors in real-time with the emergency and maintenance personnel who are actively evaluating the wildfire damage to the highways. Overall, none of the megafire-affected roadways obviously stand out as having the most damage per kilometer of roadway, nor do they show a pattern suggesting that certain routes will sustain more damage or have more traffic consequences depending on where they are located within the wildfire or in the state.

The consequences of highway damage from megafires in WA, OR, and CA can be significant. The following conclusions are derived from the analysis in this paper:

• megafires are becoming increasingly prevalent, specifically in the 21st century, and are causing substantial damage to highway infrastructure. While the causes are varied, lightning still appears to be the leading cause of ignition.

• The 2020 Labor Day wildfires were unprecedented in their intensity and destruction and showed how vulnerable transportation infrastructure can be to megafires.

• The total estimated cost impacts for WA, OR, and CA from the 2020 Labor Day wildfires were US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ • As wildfires continue to overwhelm the transportation system, new methods for evaluating threats to highways utilizing historical data, and new technologies that can help agencies quickly grasp quantity and damage predictions will become crucial. Interviews and email correspondence with emergency workers from all three states confirmed they do not currently use fire behavior models to forecast the physical and monetary damage to highways.

The problem of estimating future roadway damage losses from wildfires, which seems impossible presently, should be investigated in future studies. Since there is a dearth of prior data on wildfire-related roadway damage, applying it to other states or locations may produce better outcomes. This could include researching additional US states that regularly experience megafires and the highway damage they experience and record, as well as wildfires that are smaller and not classified as megafires but still cause substantial highway infrastructure damage. While performing this future research, it would be worthwhile to establish the minimum size of wildfire to review against highway damage to capture similar settings and categories of damage. As more data is accumulated, the results can become stronger and validated in additional forms to determine relationships and develop potential future highway damage modeling parameters and associated risks.

Without question, obtaining the limited data for this research has consistently been the biggest difficulty to address. Initial requests for highway damage resulting from the megafires from the various states were very problematic from the start. The first issue to overcome was simply determining what kind of highway damage data to ask for because there was no state, regional, or federal database to start with. Once the damage types were determined, we still had to locate where each state kept its highway damage information from the megafires. We started in OR, where we initially received a few DDIRs through ODOT's public information office, but then had to subsequently ask for additional information through each state's public records information system. Along with the public information records requests, additional clarification – through phone calls, emails, and examples of a completed DDIR were required for each of the states to receive the appropriate damage information – mainly because no one had ever asked for this kind of data before. While investigating Highway 22 in OR, which was impacted by two megafires, the Beachie Creek and Lionshead, we realized that when the highway damage was evaluated by ODOT maintenance personnel, they didn't differentiate the damage along the highway separately by wildfire, but by mileposts, which makes sense, but subsequently we had to determine where one wildfire ended and the other one started and correlate the location to mileposts along the highway and breakout the damages according to the wildfire they were within.

Another challenge arising from this work is the need to continue characterizing the wildfire damage risk to highways in more detail. The research has the advantage of addressing a real-world issue that has not received enough attention up to this point: wildfires and the damage they cause to the roadway infrastructure. This is a practical problem that we contend with regularly on an annual basis. In addition to examining the damage to the roads, this research can be utilized to understand how this subject affects the average daily traffic (ADT) on the highways and the extra expenses related to it. Future work should involve gathering information from public records domains, including upfront initial costs and subsequent reimbursement costs from the federal government, as well as surveys and interviews with emergency personnel in various states or areas, and assembling such data in a standardized database. In any case, the impending foundation analysis and highway damage assessment enhancements will strengthen our capacity to predict and reduce the danger of wildfire damage to roads.

Potential new work should also include the use of validation methods like k-fold cross-validation to estimate performance and guard against bias during the investigation. The findings could help engineers, first responders, and maintenance staff in their efforts to improve financial planning and emergency readiness to make roadway infrastructure more resilient to the many risks posed by wildfires.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Christiansen KC, Mostafiz RM, Al Assi AA; Data collection: Christiansen KC; analysis and interpretation of results: Christiansen KC, Mostafiz RM, Al Assi AA; draft manuscript preparation: Christiansen KC, Mostafiz RM, Al Assi AA, Rohli RV. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article.

-

Thanks to every participant in this research, the reviewers and editors for their comments and suggestions and thanks to each person who provided help in publishing this article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplemental Table S1 Economic Burden of Wildfire used to assess the Return on Investment into Wildfire Interventions.

- Supplemental Table S2 Washington Historical Megafires.

- Supplemental Table S3 Oregon Historical Megafires – 19th and 20th Century.

- Supplemental Table S4 Oregon Historical Megafires – 1st decade of 21st Century.

- Supplemental Table S5 Oregon Historical Megafires – 2nd decade of 21st Century.

- Supplemental Table S6 Oregon Historical Megafires – 3rd decade of 21st Century.

- Supplemental Table S7 California Historical Megafires.

- Supplemental Table S8 Highway Megafire Study Area Summary 2020.

- Supplemental Table S9 Costs of Slope/rock Scaling Damage from the 2020 Washington Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S10 Costs of Traffic Control from the 2020 Washington Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S11 Costs of Structure Damage from the 2020 Washington Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S12 Costs of Hazard Tree Removal from the 2020 Oregon Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S13 Costs of Slope/rock Scaling Damage from the 2020 Oregon Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S14 Costs of Structure Damage from the 2020 Oregon Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S15 Costs of Traffic Control from the 2020 Oregon Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S16 Costs of Hazard Tree Removal from the 2020 California Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S17 Costs of Structure Damage from the 2020 California Labor Day Wildfires.

- Supplemental Table S18 Summary of Major Characteristics of the Labor Day 2020 Megafires and Highways Affected.

- Supplemental Table S19 Historical Causes of Megafires by State, 1845 through 2023.

- Supplemental Table S20 Historical Hectares Burned by Cause from Megafires by State, 1845 through 2023.

- Supplemental Table S21 Hectares Burned per State in the 2020 Labor Day Megafires.

- Supplemental Table S22 Length of Highway (km) per state vs. Estimated Overall Damage Costs due to the 2020 Labor Day Wildfires.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Christiansen K, Al Assi A, Mostafiz RB, Rohli RV. 2024. Charting the scorched trails: a comparative analysis of roadway damage from historical megafires to the unprecedented 2020 Labor Day wildfires on the USA West Coast. Emergency Management Science and Technology 4: e015 doi: 10.48130/emst-0024-0016

Charting the scorched trails: a comparative analysis of roadway damage from historical megafires to the unprecedented 2020 Labor Day wildfires on the USA West Coast

- Received: 06 April 2024

- Revised: 09 June 2024

- Accepted: 25 June 2024

- Published online: 07 August 2024

Abstract: Roadways in the US states of Washington (WA), Oregon (OR), and California (CA) incurred extraordinary damage during the 2020 Labor Day wildfires. However, the cost and risk of these fires have not been placed in a historical perspective. This study examines the damage to roadways affected by the 2020 Labor Day wildfires in relation to the history of megafires in WA (1902–2023), OR (1845– 2023), and CA (1889–2023) using carefully selected data sets gathered from the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), and California Department of Transportation (Caltrans). A method for classifying road damage from the 2020 wildfires is also presented, with classes labeled for traffic control, slope-rock scaling, hazard trees, and structures. Total anticipated costs incurred from the 2020 megafires for both temporary and permanent repairs included over US${\$} $24 million for hazard trees, US${\$} $17.5 million for slope-rock scaling, US${\$} $43 million for structural damage, and over US${\$} $3 million for traffic control. The total average cost of both temporary and permanent repairs per km of impacted route due to the 2020 Labor Day wildfires was about US${\$} $127,783. These financial impacts can be used to better understand and manage risk attributable to this widespread and increasing hazard.