-

Minimizing postharvest losses and ensuring the safety of fresh produce are critical global challenges. Cherry tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme), prized for their high nutritional value (rich in vitamins C, E, and potassium) and sensory appeal, face significant postharvest deterioration due to their thin epidermis and high moisture content (> 90%)[1−3]. Furthermore, to mitigate pre-harvest pest/disease pressure (e.g., Botrytis cinerea, whiteflies), the intensive application of pesticides (such as chlorpyrifos) is commonplace[4], which inevitably results in concerning residue levels that pose risks to consumer health and compromise marketability[5]. Consequently, developing integrated strategies for simultaneous preservation and residue degradation represents a critical food safety imperative.

Current strategies for pesticide degradation and preservation of fresh fruits include physical[6], chemical[7], and biological approaches[8]. Conventional physicochemical methods rely on energy transfer or oxidative reactions to break pesticide bonds[6,7]. Physical techniques such as ultrasonication, ultra-high pressure, and radiation generate cavitation or mechanical stress to disrupt residues, while chemical methods employ strong oxidants (e.g., ozone, persulfates) to cleave chemical bonds through free radical oxidation. In practice, they are often combined: Ultrasound-oxidative treatments (e.g., coupling with ozone water or hydrogen peroxide, sodium persulfate) enhance free radicals generation (•OH, O•−), improving degradation of common pesticides by 30%−50% compared to solo treatments[9]. For example, ultrasound-activated persulfate systems partially degrade chlorpyrifos by attacking its P-O-C and C-S bonds[10]. However, this combination often suffers from incomplete degradation of stable pesticides, generates toxic by-products (e.g., chlorinated intermediates), and requires complex wastewater treatment[11]. Biological approaches (e.g., microbial/enzymatic degradation) offer specificity but lack broad-spectrum efficacy against pesticide mixtures and face scalability and cost barriers[12].

As a new type of non-thermal technology, dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma generates reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (RONS), UV photons, and electrons that degrade pesticides and inactivate microbes[13]. Its advantages include high efficiency, freedom from chemical residues, and negligible temperature elevation, which is critical for fresh products. DBD plasma has been widely applied in food production, sterilization[14], mycotoxins and pesticides degradation[15,16]. Recent studies have found that DBD plasma can degrade malathion (degradation rate: 53.1%) and chlorpyrifos (degradation rate: 51.4%) on fresh lettuce, while retaining the original quality[17]. The degradation of pesticides by DBD plasma has also been demonstrated on grapes, strawberries, and so on. Despite these advantages, the broader application of DBD plasma on food products is constrained by two inherent limitations: the transient nature of reactive species necessitates repeated treatments to maintain efficacy, significantly increasing operational energy costs; moreover, its limited penetration depth restricts microbial inactivation to superficial layers while failing to degrade pesticides infiltrated into cuticular matrices or stem scars[18].

The use of natural antimicrobial coatings (such as those made from chitosan, sodium alginate, starch, and so on) on fresh food represents an innovative method for preserving fruit quality. These edible barriers maintain high fruit quality by inhibiting pathogen growth and reducing moisture loss and gas exchange. Among these, the low toxicity and mechanical flexibility of sodium alginate have made it an excellent choice for the preparation of new-generation edible coatings in recent years[19]. However, the biopolymer coatings exhibit limited antimicrobial efficacy against resilient pathogens and possess no inherent capacity for pesticide residue degradation, failing to address dual spoilage-safety concerns. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles offer a promising functional enhancement through photocatalytic activity, where UV illumination generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide anions (O2•−) that simultaneously inactivate broad-spectrum microorganisms and mineralize pesticide residues via oxidative bond cleavage[20]. Nevertheless, the practical implementation of TiO2-based coatings confronts two critical constraints: its mandatory dependence on UV wavelengths severely restricts activation under commercial storage conditions, while non-selective ROS generation risks collateral oxidation of nutritional components, posing fundamental questions about how to achieve targeted, energy-efficient photocatalytic functionality without compromising fruit quality.

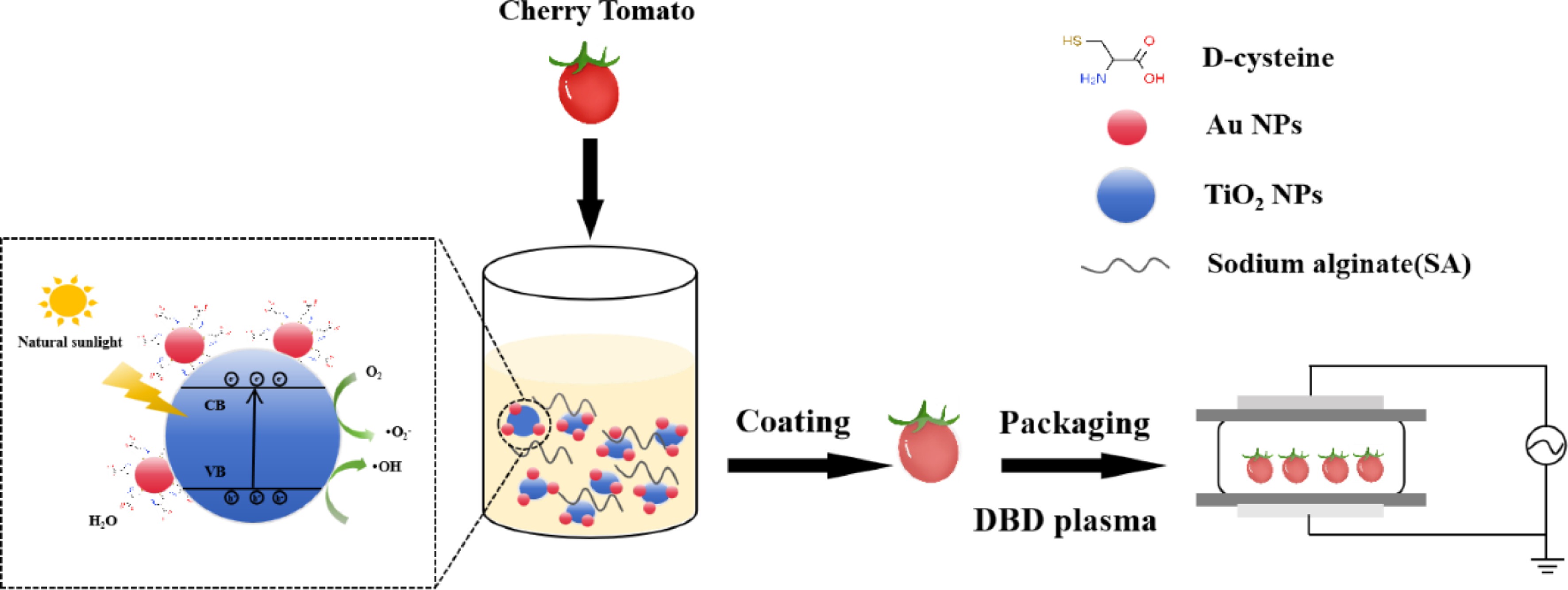

To overcome these limitations, this study introduces an innovative physical–chemical synergistic system. As illustrated in Fig. 1, an integrated approach was developed combining a chiral D-cys/Au NPs-modified TiO2 (DAT) nanoparticles-embedded sodium alginate (SA) coating matrix with dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma treatment for simultaneous preservation and pesticide degradation of cherry tomatoes. The DAT/SA composite film provides sustained, visible-light-responsive photocatalytic activity at the fruit surface, enabling targeted generation of ROS for efficient pesticide degradation while minimizing nutrient loss. Concurrently, the DBD plasma treatment delivers a potent burst of RONS and physical agents for immediate surface microbial inactivation and initiates pesticide breakdown. This synergistic interplay effectively addresses the core challenges of deep pesticide residue penetration, sustained antimicrobial action, and energy–efficient, quality–preserving operation.

-

Acetonitrile (HPLC grade) was acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Formic acid (HPLC grade) was purchased from CNW Technologies Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Purified water was obtained from Quchenshi Group Co., Ltd. Other reagents used were of analytical grade.

Preparation of DAT/SA composite films

-

The DAT (D-cys/Au NPs-modified TiO2) nanoparticles were synthesized via a two-step process according to the previous reports[21]. First, D-Au NPs were prepared by the citrate reduction of HAuCl4, followed by functionalization with SH-PEG and D-cysteine. Subsequently, these D-Au NPs (0.3 μg/mL) were deposited onto TiO2 nanoparticles through ultraviolet light-assisted photodeposition. The resulting composites were collected via centrifugation, washed, and dried.

The preparation of DAT/sodium alginate composite films: Sodium alginate (SA, 2 g) and glycerol (1 mL, 1% v/v) were dissolved in 100 mL of ultrapure water under constant stirring at 50 °C. Specified amounts of the synthesized DAT nanoparticles were then incorporated to achieve final loadings of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 wt% relative to SA. The resulting mixtures were designated as 0.1-, 0.2-, 0.3-, and 0.4-DAT/SA, respectively. Each solution was sonicated (100 W, 40 min) to remove air bubbles. Aliquots (10 mL) of the SA control and the DAT/SA dispersions were cast into 90 mm-diameter Petri dishes and dried at 60 °C for 6 h to form free-standing films.

Characterization of composite films

Water solubility

-

The prepared DAT/SA composite films were cut into 3 × 3 cm squares, and a '+' mark was inscribed at the center. Samples were submerged in 100 mL ultrapure water under magnetic stirring (300 rpm) at 25 °C. The time required for complete dissolution (disappearance of the '+' mark) was recorded. Shorter dissolution times indicate higher water solubility.

Water vapor permeability (WVP)

-

Films were sealed over weighing bottles (25 × 25 mm) containing 5 g anhydrous calcium chloride. Initial weights were recorded, and bottles were placed in a climate chamber (25 °C, 70% RH). Weight changes were measured at 24-h intervals until equilibrium. The water vapor permeability (WVP, g·mm/(h·m2·kPa)) was calculated according to the Eq. (1):

$ \mathrm{WVP}=\dfrac{{\Delta }{\mathrm{m}}\times {\mathrm{d}}}{{\Delta }{\mathrm{t}}\times {\mathrm{A}}\times {\Delta }\text{P}} $ (1) where, Δm represents the mass difference between the sample before and after stabilization, in grams (g); d denotes the thickness of the films, in millimeters (mm); Δt is the measurement interval time, in hours (h); A stands for the effective water vapor permeation area of the films, in square meters (m2); ΔP indicates the pressure difference between the inner and outer sides of the film, in kilopascals (kPa).

Treatment of cherry tomatoes

-

According to GB 2763-2021 and the EU's maximum residue limits for pesticides in food, the maximum residue limit of chlorpyrifos in cherry tomatoes is 0.5 mg/kg. An initial concentration of 0.7 mg/kg was selected to simulate a realistic scenario where pesticide residues may exceed the maximum residue limit (MRL of 0.5 mg/kg for chlorpyrifos on tomatoes) and to provide a sufficiently high challenge to effectively evaluate the degradation performance of the DAT/SA-DBD plasma system. Chlorpyrifos emulsion (48%) was diluted to 2 μg/mL with distilled water and uniformly sprayed onto cherry tomatoes to ensure a homogeneous distribution on the surface. The treated cherry tomatoes were dried in the dark for 12 h.

Undamaged cherry tomatoes of uniform size were divided into six groups, with the control group receiving no treatment. Cherry tomatoes in the treatment group were soaked in film-forming solution (SA and DAT/SA) for 10 s, air-dried (25 °C), and then exposed to DBD plasma ( 140 kV, 50 Hz, 3 min). All samples were packaged in perforated boxes (100.0 g per box) and stored at 15 °C under light for 11 d. Quality parameters and chlorpyrifos degradation efficiency were monitored throughout storage.

Basic quality analysis of treated cherry tomatoes

Weight loss and decay rate

-

The weight loss rate of cherry tomatoes during storage was determined by weighing, calculated using the Eq. (2) as follows:

$ \text{Weight loss rate}=[({\mathrm{m}}_{0}- \mathrm{m}_{\mathrm{t}} )/\mathrm{m}_{0} ]\times 100{\text{%}} $ (2) where, m0 is the initial weight of cherry tomotoes, and mt is the weight after storage time t.

Decay was assessed by directly counting rotten fruits during storage. Fruits were considered rotten if they exhibited mold (mold spot diameter ≥ 2 mm), cracking, or juice leakage. The decay rate was calculated as the ratio of rotten fruits to the total number of fruits in each group.

Hardness and soluble solid content

-

Fruit hardness (peel and flesh) was measured using a TA.XT Plus texture analyzer. For each group, randomly selected cherry tomatoes were tested at the equatorial region with the following parameters: 5 mm diameter probe, 50 N puncture force, 0.3 N initial force, 200 mm/s detection speed, and 5 mm puncture depth.

Soluble solid content was determined using a Pal-EX/ACID handheld sugar-acid analyzer. Samples were randomly selected from each box, ground, squeezed, and the filtrate was analyzed.

Microbiological analysis

-

Accurately weighed cherry tomatoes (10 g) were homogenized with sterile saline (90 mL) in a sterile bag for 1 min. Total bacterial counts, molds, and yeasts were determined according to GB 4789.2-2016 and GB 4789.15-2016 standards.

Analysis of chlorpyrifos

Extraction procedure

-

Chlorpyrifos was extracted from cherry tomatoes using the QuEChERS method. Briefly, homogenized tomato samples (5.0 ± 0.01 g) were mixed with acetonitrile (10 mL), anhydrous MgSO4 (4 g), sodium citrate (1 g), disodium hydrogen citrate (0.5 g), and a ceramic homogenizer in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. These tubes were vortexed (1 min) and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min. Then, the supernatant (5 mL) was transferred to a 10 mL centrifuge tube containing 150 mg PSA, 45 mg GCB, and 855 mg anhydrous MgSO4. The mixture was vortexed again for 30 s and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min. The final extract was filtered (0.22 μm) for UPLC-MS analysis.

HPLC-MS analysis

-

Pesticide concentrations before and after photocatalytic degradation were quantified using an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS, AB SCIEX 5500). Chromatography separation was performed on a Phenomenex Kinetex F5 column (2.1 × 100 nm, 2.6 μm). The mobile phase comprised of 0.1% formic acid in purified water (A) and methanol (B) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C to improve resolution. The gradient program was as follows: 0−2 min 90%−0% A, 2−4 min 0% A, 4.1−6 min 90% A. Each sample was injected in triplicate to verify reproducibility. The degradation percentage (η%) was calculated using Eq. (3) as follows:

$ \eta {\text{%}} =[({\mathrm{C}}_{ {0}} -{{\mathrm{C}}}_{{{\mathrm{t}}}} )/{\mathrm{C}}_{ {0}} ]\times 100{\text{%}} . $ (3) where, C0 is the initial concentration of chlorpyrifos, and Ct is the concentration of chlorpyrifos after storage time t.

Spiked recovery test and relative standard deviation (RSD)

-

Chlorpyrifos was spiked into samples at concentrations of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 mg/kg. Three replicate solutions were prepared for each concentration, added to pre-homogenized samples, and thoroughly mixed. The average recovery rate and RSD were calculated following the extraction procedure described in 2.5.1 and the quantification method in 2.5.2 to validate the accuracy of the extraction and determination methods. Each group was analyzed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS Statistics 26. p < 0.05 (Duncan's multiple-range test) was considered statistically significant.

-

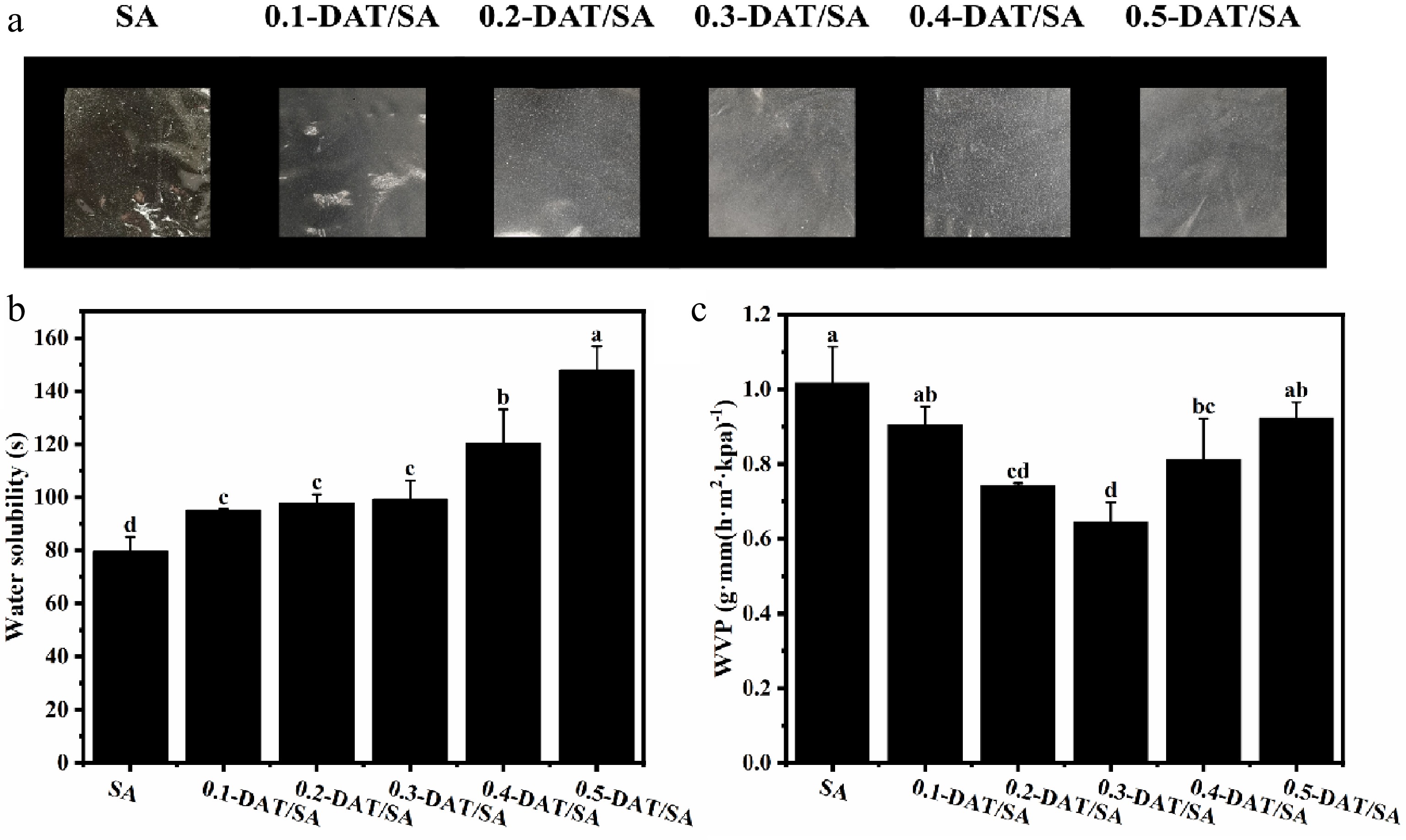

The concentration of DAT incorporated into the sodium alginate (SA) solution significantly influenced the physicochemical properties of the resulting composite films. Accordingly, mechanical properties, including transparency, water solubility, and water vapor permeability (WVP), were evaluated for DAT/SA film containing DAT in the range of 0.1% to 0.5%. As shown in Fig. 2a, higher DAT loading was expected to enhance the antibacterial properties of the film; however, it also resulted in poorer dispersion within the SA matrix, leading to increased surface roughness and reduced brightness. Since an effective edible coating must achieve preservation functionality without compromising the visual appearance of the fresh produce, balancing these properties is essential.

Figure 2.

(a) Appearance, (b) water solubility, and (c) water vapor permeability rate of DAT/SA composite film.

Water solubility is another crucial factor for practical application, as it affects the ease of film removal during washing and helps minimize residual material on the fruit surface. Figure 2b shows the water solubility of the DAT/SA composite films. Compared to the pure SA film (79.67 s), the dissolution time of the composite films increased with DAT content, rising from 79.67 to 147.92 s. This indicates that higher DAT loading reduces the water solubility of the film. Highly soluble films are more susceptible to softening under high relative humidity, allowing moisture penetration[22]. Thus, they are less suitable for coating high-moisture produce or items stored under high-humidity conditions. Nevertheless, a certain degree of water solubility is necessary to ensure the film can be removed without leaving residues, thereby maintaining safety and cleanliness after washing.

Water vapor permeability (WVP) reflects the barrier performance of the composite film against environmental moisture. A lower WVP value indicates better barrier properties, making it more difficult for external water vapor to penetrate the film and reach the coated food. This inhibits microbial growth and helps regulate respiration, thereby improving preservation efficacy[23]. As shown in Fig. 2c, the incorporation of DAT enhanced the water vapor barrier of the SA film. This improvement is attributed to the ability of nanoscale DAT to increase film density, thus hindering water vapor infiltration[24]. However, the WVP of DAT/SA composite films showed a non-linear trend: it initially decreased, then increased with higher DAT content. Excessive DAT led to aggregation and poor dispersion, forming larger pores within the film structure and facilitating water vapor transmission[25].

Considering the insolubility and dispersibility of DAT, the coating performance of various DAT/SA films on cherry tomatoes is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. As DAT content increased to 0.4%, the composite film coated on the surface of cherry tomatoes exhibited noticeable particles and a rougher texture; however, the impact on the brightness of the fruit remained negligible. Based on the above results, the 0.3% DAT/SA composite film was selected for subsequent shelf-life studies.

Synergistic effects of DAT/SA coating and DBD plasma treatment on cherry tomatoes

-

Dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma has emerged as a promising non-thermal method for microbial decontamination in fresh produce. However, its standalone application often exhibits short-lived antimicrobial efficacy and may require high-intensity treatment that risks compromising product quality. In this study, a novel combination of DBD plasma pretreatment and a composite coating consisting of sodium alginate (SA) and chiral cysteine-modified TiO2 (DAT) was applied to enhance the postharvest preservation and safety of cherry tomatoes.

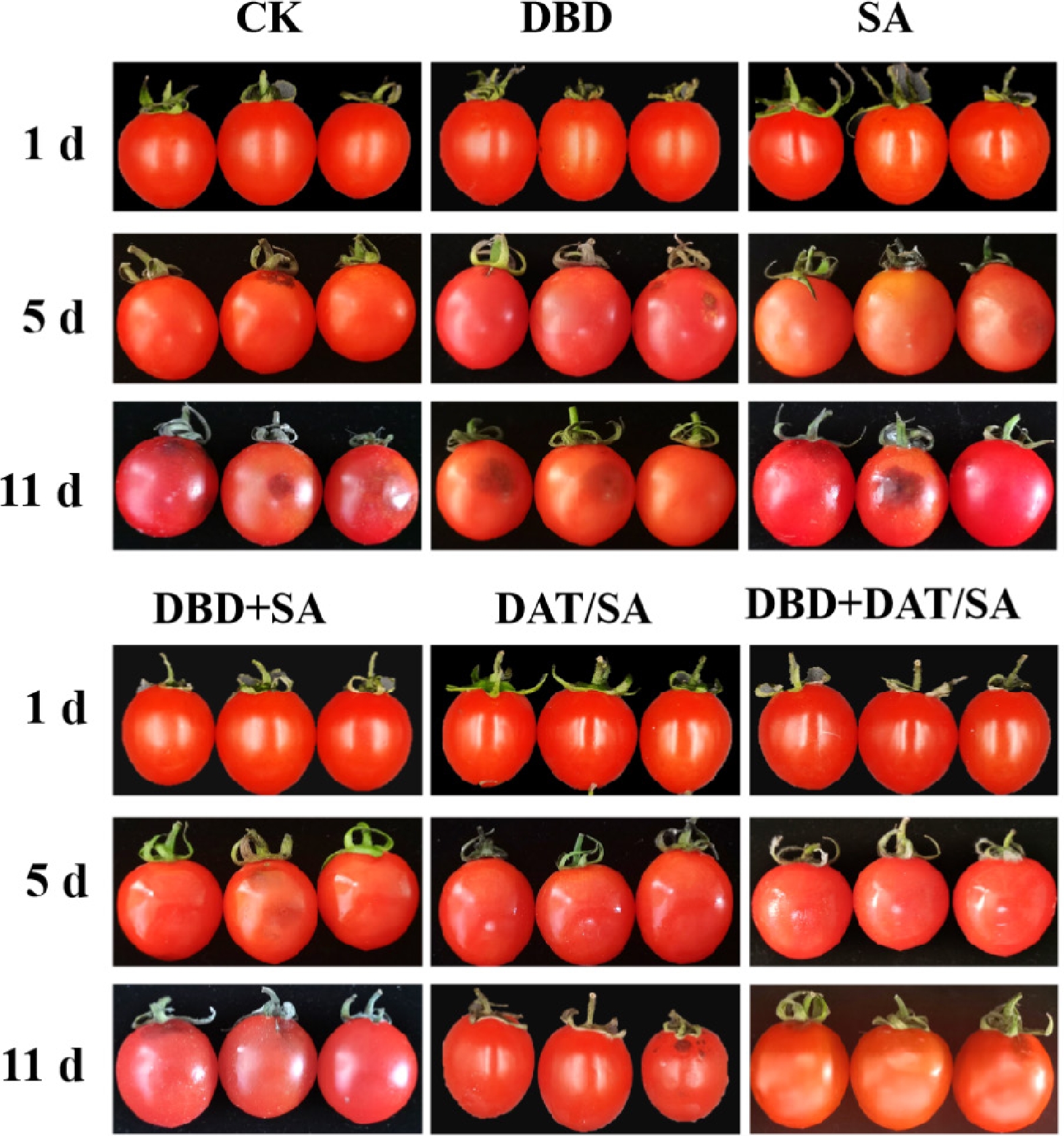

Sensory evaluation (Fig. 3) demonstrated that the combined DBD + DAT/SA treatment provided the most effective preservation. Control (CK), DBD-only, and SA-only samples developed visible moldy spots by day 5 and were completely soft and spoiled by day 11. Although the DBD + SA treatment delayed mold development, it failed to prevent final spoilage. In contrast, both DAT/SA and DBD + DAT/SA treatments significantly inhibited mold growth and decay, with visible spoilage only appearing on day 11, indicating a substantial extension of marketable life.

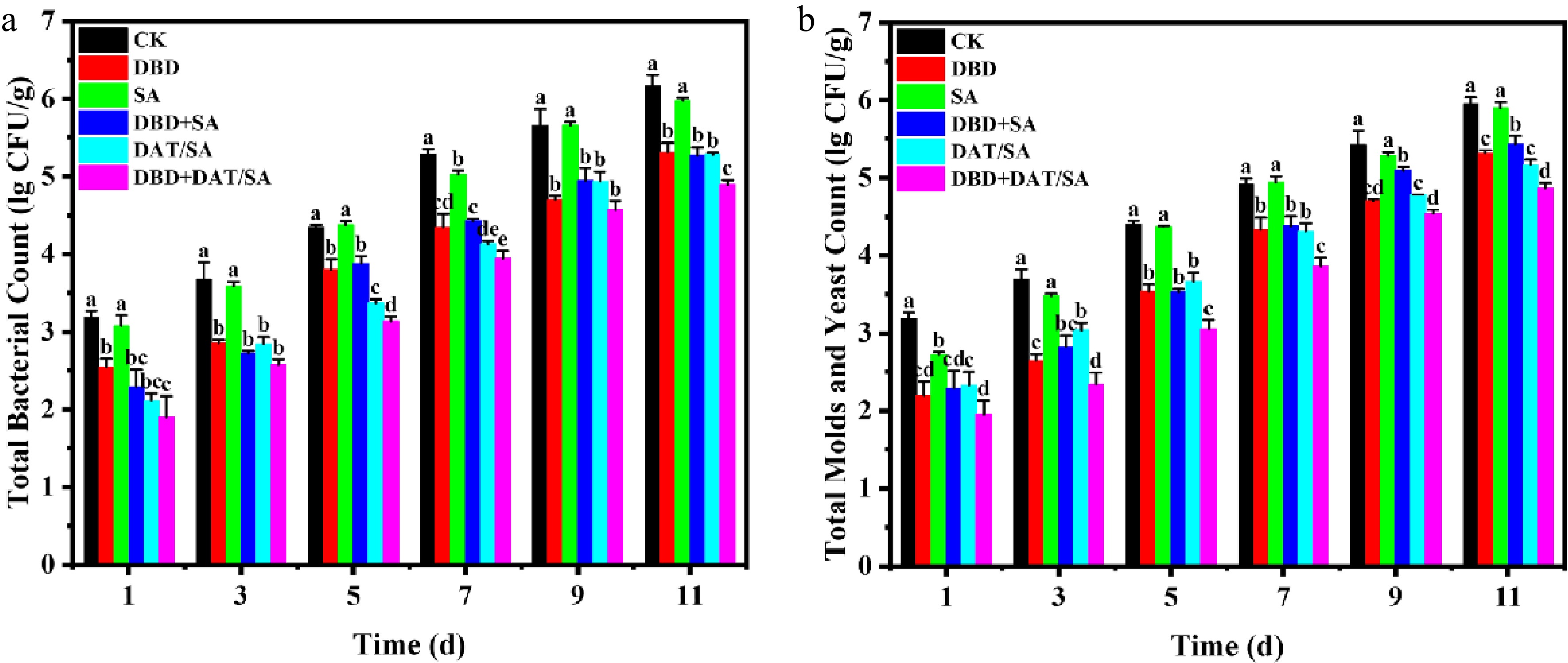

This preservation effect was strongly associated with microbial suppression (Fig. 4a, b). All active treatments except SA-alone reduced microbial counts relative to the CK group from day 1. The initial total aerobic bacterial count in the CK group was 3.18 log CFU/g, while the DBD, DAT/SA, and DBD + DAT/SA treatments showed reductions of 0.64, 1.02, and 1.28 log CFU/g, respectively. The DBD + DAT/SA group exhibited the strongest bacterial inhibition. A similar trend was observed for molds and yeasts. By day 11, the CK group (6.18 lg CFU/g) exceeded the microbial safety threshold of 6 log CFU/g, whereas the DBD + DAT/SA group remained 1.28 and 0.98 log CFU/g below CK for bacteria and fungi, confirming a potent and sustained antimicrobial synergy.

Figure 4.

(a) Total number of colonies, and (b) total number of molds and yeasts in cherry tomatoes stored at 25 °C for 11 d.

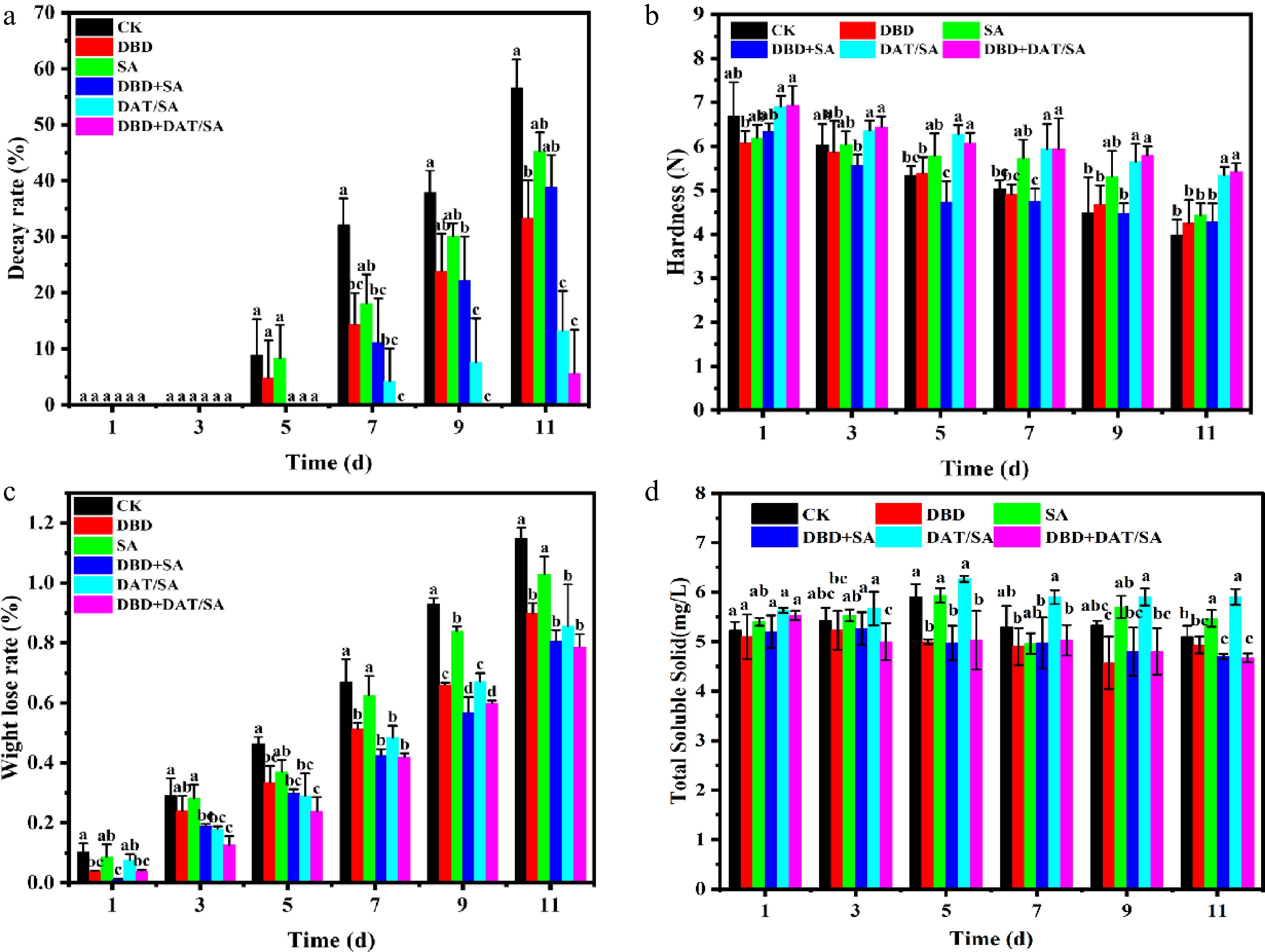

Decay rate (Fig. 5a), an important consumer-quality indicator, further highlighted the synergistic effect[26]. Decay began on day 3 (CK and SA), day 5 (DBD-alone), and day 7 (DAT/SA and DBD + SA). The DBD + DAT/SA treatment provided the strongest protection, delaying decay onset until day 9. By the end of the storage period (day 11), the decay rates of DAT/SA and DBD + DAT/SA groups were 44.82% and 50.99% lower than that of CK, respectively. Among them, the DBD + DAT/SA coating exhibits the best efficacy, extending the storage period by more than 4 d.

Figure 5.

(a) Decay rate, (b) firmness, (c) weight loss rate, and (d) soluble solids content of cherry tomatoes stored at 25 °C for 11 d.

Hardness, a critical indicator of freshness and ripening[27], was also better maintained in DAT-based treatments (Fig. 5b). Although DBD-alone showed no significant effect (p > 0.05), DAT/SA and DBD + DAT/SA treatments consistently resulted in higher hardness, measuring 1.34 and 1.36 times that of CK on day 11. This can be attributed to the DAT/SA coating retarding the enzymatic degradation of protopectin, thereby delaying tissue softening.

During storage, fresh vegetables exhibit strong respiration and transpiration, which leads to water loss, quality decline, shrinkage, and reduced freshness[28]. Weight loss analysis (Fig. 5c) indicated that the SA coating reduced respiration and transpiration, thereby slowing water loss[29]. The DAT/SA film, with enhanced density and barrier properties due to the nano-TiO2 filler, more effectively reduced moisture transfer. DBD pretreatment likely improved coating adhesion, contributing to the significantly lower (p < 0.05) weight loss in combined treatment groups and helping maintain fruit turgor.

Soluble solid content, primarily composed of sugars used in respiration[30], varied among treatments (Fig. 5d). DBD-treated groups (DBD, DBD + SA, and DBD + DAT/SA) exhibited a pronounced TSS decrease, reaching the lowest values (4.67−4.93) by day 11, possibly due to plasma-induced oxidative stress accelerating carbohydrate breakdown[31]. In contrast, the DAT + SA group maintained the highest TSS levels on day 11, likely because the SA matrix created a modified atmosphere (low O2, high CO2) that suppressed respiration[32], while the incorporated DAT enhanced structural stability and gas barrier properties, collectively slowing sugar consumption—an effect consistent with reports on other coated fruits[33,34].

Synergistic degradation of chlorpyrifos by DAT/SA film and DBD plasma treatment

-

The recovery rates for chlorpyrifos spiked into the cherry tomato sample are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The method demonstrated satisfactory accuracy, with recoveries ranging from 90% to 110%, and good precision, as indicated by a relative standard deviation (RSD) of less than 4%. These results confirm that the extraction and analytical procedures are reliable and meet the requirements for quantitative analysis in this study.

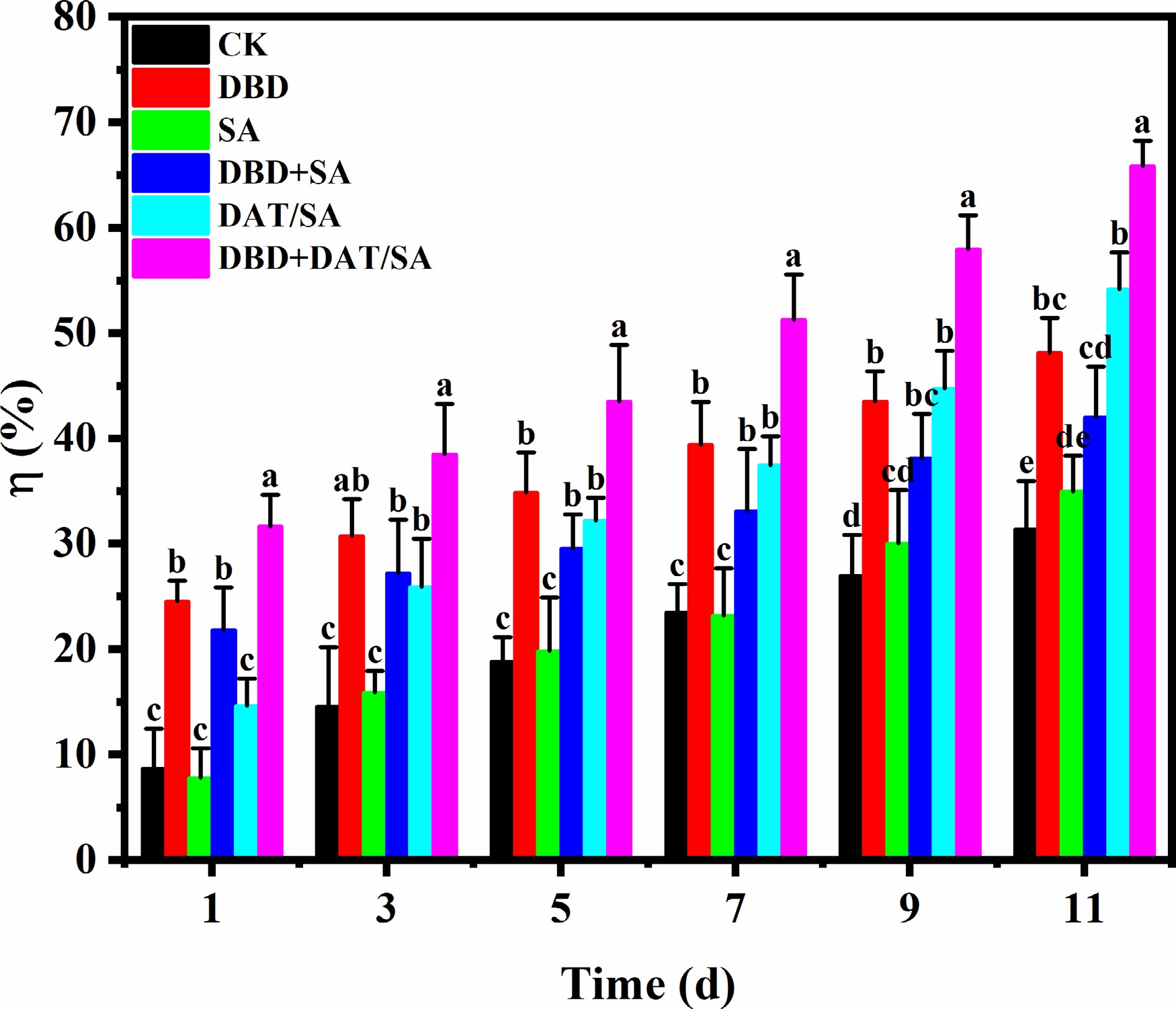

The degradation behavior of chlorpyrifos under different treatments during storage is presented in Fig. 6. Chlorpyrifos underwent natural degradation over time, with a degradation rate of 31.35% observed in the control (CK) group after 11 d of storage. The SA coating alone did not significantly enhance chlorpyrifos degradation compared to the CK group. Interestingly, the combination of SA coating with DBD plasma treatment (DBD + SA) resulted in a lower degradation efficiency than DBD treatment alone. This suggests that the SA film may partially impede the interaction between the reactive species generated by the DBD plasma and the pesticide residues. In contrast, significant enhancement in chlorpyrifos degradation was achieved in the DBD, DAT/SA, and DBD + DAT/SA treatment groups. After 11 d, the degradation rates reached 48.17%, 54.17%, and 65.86%, respectively. The corresponding residual concentrations of chlorpyrifos in cherry tomatoes were reduced to 0.36, 0.32, and 0.24 μg/mL. Notably, all these values are below the maximum residue limit (MRL) of 0.5 μg/mL for chlorpyrifos in cherry tomatoes as stipulated by the Chinese national standard GB 2763-2021.

Among all treatments, the DBD + DAT/SA combination exhibited the highest degradation efficiency. This synergistic effect can likely be attributed to the enhanced photocatalytic activity of DAT induced by the UV emission generated during DBD plasma treatment. The plasma-produced UV light may activate the DAT material within the composite film, promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species or other active sites that facilitate the breakdown of chlorpyrifos molecules. Therefore, the integration of DBD plasma with the DAT/SA composite film presents a promising approach for effectively degrading pesticide residues on the surface of cherry tomatoes.

-

This study demonstrates the successful development of a synergistic decontamination and preservation strategy for cherry tomatoes by integrating a chiral TiO2/SA (DAT/SA) composite film with DBD plasma. The key innovation is the remarkable synergy between the two technologies: DBD plasma not only directly generates reactive species for pesticide degradation and inactivates surface microbes (bacteria and molds), but also activates the photocatalytic property of the DAT via its UV emission, supporting a more effective treatment process. The DAT/SA film concurrently acts as a protective barrier, reducing water loss and delaying the ripening process to maintain fruit quality. This protective function, combined with the synergistic degradation action, resulted in a shelf-life extension of over 4 d and a chlorpyrifos degradation rate exceeding 65%. This green, combined approach offers a promising alternative to conventional methods, with potential applications for other perishable horticultural products. Future work should focus on process optimization for scalable implementation.

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Administration for Market Regulation Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. KJ2024007).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: data curation and writing − original draft preparation: Zhang J, Cui M; formal analysis: Song J; investigation: Zhang J; writing − review and editing: Zou J, Yan W; supervision: Yan W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated or analyzed during the this study are included in the published article and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jinzhu Song, Jiajia Zhang

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Appearance of cherry tomatoes coated with DAT/SA composite films containing different DAT concentrations:(1) Control (untreated); (2) SA (Sodium Alginate only); (3) 0.1-DAT/SA; (4) 0.2-DAT/SA; (5) 0.3-DAT/SA; (6) 0.4-DAT/SA; (7) 0.5-DAT/SA.

- Supplementary Table S1 Recovery rates of chlorpyrifos in cherry tomatoes.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Song J, Zhang J, Cui M, Zhang J, Zou J, et al. 2026. Synergistic preservation and pesticide degradation of cherry tomatoes combined with DAT/SA composite film and DBD plasma. Food Materials Research 6: e001 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0026-0001

Synergistic preservation and pesticide degradation of cherry tomatoes combined with DAT/SA composite film and DBD plasma

- Received: 13 November 2025

- Revised: 18 December 2025

- Accepted: 27 December 2025

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: Ensuring the safety and extending the shelf-life of fresh produce are critical global concerns, necessitating effective technologies to mitigate microbial spoilage and pesticide contamination. This study proposes a synergistic approach combining a chiral TiO2/sodium alginate (DAT/SA) composite film with dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma for simultaneous preservation of cherry tomatoes and degradation of pesticide residues. The optimal 0.3% DAT/SA film was used in combination with DBD plasma (140 kV, 50 Hz, 3 min). This combined treatment significantly enhanced chlorpyrifos degradation to 65.86% after 11 d, markedly outperforming individual DBD (48.17%) or film (54.17%) treatments. It also effectively preserved quality: total bacterial count was reduced by 1.28 lgCFU/g, the decay rate was lowered by 50.99%, and fruit firmness and moisture were better maintained. This approach provides an efficient, eco-friendly method for simultaneous preservation and pesticide degradation in fresh produce.

-

Key words:

- Chiral TiO2 /

- Sodium alginate /

- DBD plasma /

- Preservation /

- Pesticide residues