-

Anthocyanins are a subgroup of flavonoids with a distinctive C3-C6-C3 carbon structure found widely in plants[1,2]. Anthocyanins, as water-soluble natural pigments, confer red, blue, and purple hues found in fruits, flowers, and vegetables[3−5]. Anthocyanins exert multiple functions in plants. The vivid colors of anthocyanins attract animals for pollination and seed dispersal[6]. Anthocyanins protect plants from ultraviolet B damage and enhance the tolerance of plants under abiotic and biotic stress[7,8]. Furthermore, anthocyanin-rich foods are also beneficial for humans as antioxidants to reduce the onset of various chronic diseases, such as cancer, obesity, and cardiovascular disease[9,10]. Therefore, there is substantial interest in improving the contents of anthocyanins with enhanced color and visual appeal, a significant quality trait for horticultural crops[5].

Anthocyanins are produced through the phenylpropanoid pathway on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum and accumulate in cell vacuoles of fruits, flowers, and leaves[11−16]. Anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway is highly conserved and well-studied in plants[17,18]. A large number of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes from enormous horticultural crops have been identified[19,20]. The anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes (ABPs) include phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanin synthase (ANS), and flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT)[19−21]. The transcript abundances of these structural genes are modulated by numerous transcription factors (TFs). Many TFs that promote anthocyanin biosynthesis have been identified in horticulture crops[22−32]. Among these TFs, MYB proteins are the most studied TFs[19,22,26,28,32]. MYB interacts with bHLH and WD40 to form the well-known MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complexes that centrally regulate the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway[19,22,26,28,32]. Numerous MYBs and other TFs or regulatory factors activate the expression of ABPs via direct or indirect regulation of MBW complexes[19,22,26,28,32]. Besides the MBW complexes, other activation complexes including MBW-WRKY26[33], BBX18-HY5[34], and ERF3-MYB114-bHLH3[35] have also been documented to promote the expression of ABPs or MYBs. In contrast to these positive regulatory TFs on anthocyanin biosynthesis, an increasing number of TFs involved in repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis have recently been identified[16,36−38]. This review focuses on TFs repressing the function of the activation complexes, TFs regulating repressors, and the repression motifs, as well as posttranscriptional regulations, post-translation modifications, and methylation of TFs to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis in fruits, flowers, and vegetables.

-

Transcription factors play important roles in the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Among these TFs, R2R3-MYB, basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH), and WD40 form a critical transcriptional activation complex (MBW) that plays a central role in modulating the expression of anthocyanin structural genes[39]. A large number of studies have focused on the positive regulation of anthocyanin production by this highly conserved MBW complex[2−4,6,7]. Nevertheless, TFs that repress anthocyanin biosynthesis, or repressors of anthocyanin biosynthesis, have also been discovered[16,36−38], especially in recent years.

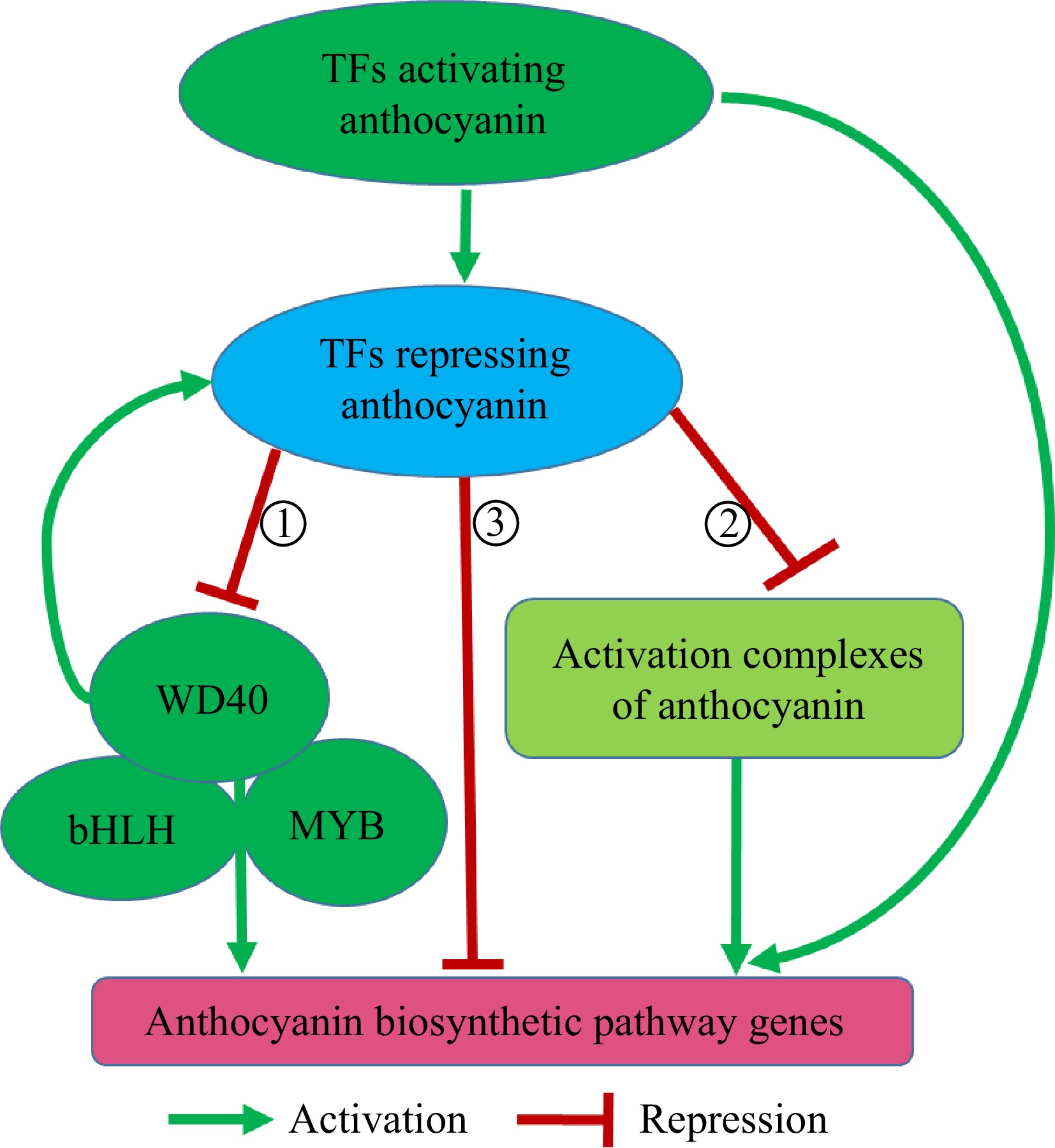

Numerous studies reveal that the main machinery for the TFs repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis is obstructing the formation of MBW activation complexes (Fig. 1). Peach PpMYB18 regulates the biosynthesis of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins by competing with MYB activators PpMYBPA1 and PpMYB10.1 to bind to PpbHLH3 or PpbHLH33[40]. Pear PyMYB140 competes with anthocyanin-activated MYB to bind to bHLH and hamper the formation of the MBW complex, repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis in red pear[41]. Strawberry FaMYB1 acts as a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis by competing with MYB activators for binding to bHLH[42]. Similar to PpMYB18, PyMYB140, and FaMYB1, many other MYB TFs inhibiting anthocyanin biosynthesis have also been identified, including R2R3-type PhMYB27 from Petunia (Petunia hybrida)[43], R2R3-type SlMYB7 from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)[44], R3-MYB SlMYBATV form tomato[45−47], R2R3-type MdMYB308 and MdMYB15L from apple (Malus domestica)[48,49], R2R3-type PpMYB17-20 from peach (Prunus persica)[50], R2R3-type MYBC2-L1 and MYBC2-L3 from grape (Vitis vinifera)[51], R2R3-type FhMYB27 and R3-type FhMYBx from Freesia hybrida[52], R3-type BrMYBL2.1 from Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L.)[53], R2R3-type TgMYB4 from tulips (Tulipa gesneriana L.)[54], and DcMYB2 from carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus L.)[55]. Most of them exert their function roles by interacting with the bHLH of the MBW complexes via the bHLH binding domain to compete binding to bHLH and interfere with the MBW complex formation to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Figure 1.

The regulatory network of transcription factors (TFs) repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops. The repressors affect the formation of MBW(①)/other activation complexes (②) to indirectly repress anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes (ABPs) or directly inhibit ABPs (③). TFs activating anthocyanin and MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex can also induce the expression of repressors to balance the biosynthesis of anthocyanin in horticulture crops. The activation complexes of anthocyanin mainly include MBW-WRKY26[33] in grape, BBX18-HY5[34] in pear, and ERF3-MYB114-bHLH3[55] in pear.

Besides obstructing the formation of functional MBW complexes, TFs are also identified by suppressing the assembly of other activation complexes to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis (Fig. 1)[34,35]. Pear PpBBX18 interacts with PpHY5 to form a PpBBX18-PpHY5 activation complex to activate the expression of PpMYB10 and promote anthocyanin biosynthesis. However, when PpBBX21 interacts with PpBBX18 and PpHY5, it destabilizes the PpBBX18-PpHY5 complex and represses anthocyanin biosynthesis[34]. Moreover, pear PyERF4.1/PyERF4.2 interact with PyERF3 to destabilize the PyERF3-PyMYB114-PybHLH3 activation complex, decreasing the expression of the anthocyanin biosynthetic gene PyANS and anthocyanin biosynthesis[35]. In addition, some repressors also directly inhibit ABPs (Fig. 1)[42−44]. Thus, TFs disrupting the formation of the other activation complexes and directly inhibiting ABPs also represent important mechanisms for negatively regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticulture crops (Fig. 1).

-

The recent advance in anthocyanin research also identifies TFs that activate the expression of repressors to interfere with the formation of MBW complexes or other activation complexes, thus fine-tuning anthocyanin biosynthesis (Fig. 1). For example, PyERF3 interacts with PyMYB114 and PybHLH3 to promote anthocyanin biosynthesis in red-skinned pears. Interestingly, PyMYB114 enhances the transcript levels of anthocyanin repressors PyERF4.1/PyERF4.2 to destabilize the PyERF3-PyMYB114-PybHLH3 complex, resulting in a reduction of anthocyanin biosynthesis[35]. In pears, a feedback regulation loop forms to balance the excessive biosynthesis of anthocyanin in red-skinned pears[35]. Activator-type R2R3-MYBs (PpMYB10.1 and PpMYBPA18) enhance the expression of a repressor-type R2R3-MYB gene PpMYB18, and then PpMYB18 competes with PpMYB10.1 and PpMYBPA1 for binding to PpbHLH3 and PpbHLH33 to fine-tune anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in peach[40]. Tomato R2R3-MYB TF (SlAN2-like) promotes the expression of anthocyanin suppressor SlMYBATV, and then SlMYBATV disturbs the formation of the MBW complex to affect the biosynthesis of anthocyanin[43]. Citrus CsRuby1 and CsMYB3 are activators and repressors of ABPs, respectively. CsRuby1 promotes the expression of CsMYB3 by promoter binding, while CsMYB3 inhibits the activity of the CsRuby1-CsbHLH1 complex. Therefore, CsRuby1 and CsMYB3 form an 'activator-and-repressor' loop to modulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in citrus[56]. Moreover, in Freesia flowers, the transcriptions of two types of suppressors, R2R3-type FhMYB27 and R3-type FhMYBx, are activated by the MBW complex to fine-tune anthocyanin biosynthesis[52].

These studies show that the repressors of anthocyanin biosynthesis not only inhibit the activation complexes but are also activated by the other TFs to balance the anthocyanin biosynthesis (Fig. 1). This kind of regulatory loop has been identified in numerous horticultural crops[35,40,41,43,56]. Furthermore, the hierarchical and feedback regulatory loops also show sophisticated anthocyanin regulatory networks in horticultural crops.

-

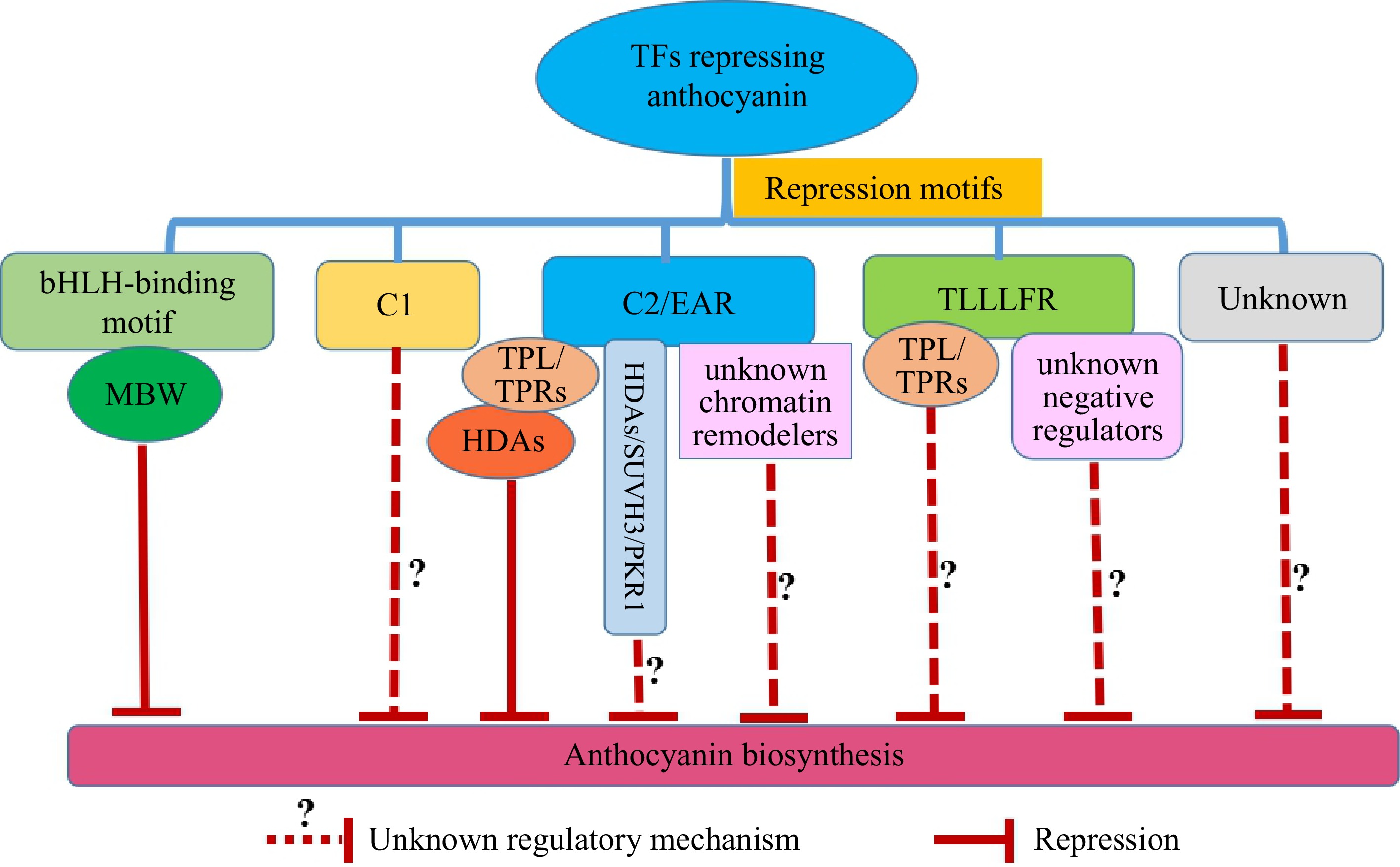

Repression motifs are important regulatory elements of TFs in inhibiting the synthesis of anthocyanins[16,36−38]. Several repression motifs in TFs that repress anthocyanin biosynthesis have been identified. They include the bHLH-binding motif ([D/E]Lx2[R/K]x3Lx6Lx3R), C1 motif (LIsrGIDPxT/SHRxI/L), the ERF-associated amphiphilic repression (EAR) motifs (LxLxL, DLNxP, and DLNxxP), and the TLLLFR motif (Fig. 2)[40,57−59].

Figure 2.

Repression motifs and the molecular mechanisms of TFs with repression motifs to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops. The TFs with bHLH-binding motifs repress anthocyanin biosynthesis by interfering with the formation of MBW complexes. The repression mechanism of the TFs with the C1 motif is unknown. The TFs with EAR motif forming TF-TPL/TPRs-HDAs complexes to inhibit anthocyanin biosynthesis have been identified[73,74]. In addition, TFs with EAR motif may recruit histone methylation-linked chromatin remodelers (SUVH3 and PKR1) or unknown chromatin remodelers[58,80] to inhibit anthocyanin biosynthesis. The TFs with TLLLFR motif may interact with TPL/TPRs[58] or unknown negative regulators to inhibit anthocyanin biosynthesis. The function of unknown repression motifs of TFs in horticultural crops awaits further investigation. MBW is the complex formed by R2R3-MYB, bHLH, and WD40; TPL/TPRs are transcriptional corepressor TOPLESS/TOPLESS-related proteins; HDAs are histone deacetylases.

In peach, PpMYB18 harbors a bHLH binding motif which makes PpMYB18 compete with PpMYB10.1 and PpMYBPA1 to bind to bHLH, thereby passively repressing the biosynthesis of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin[40]. The C1 motif was also identified in peach PpMYB18[40], although the repression mechanism of the C1 motif is unknown (Fig. 2). The C2 repression motif, also named the EAR motif, is present in a wide range of repressors from different TF families[60]. The ability of the EAR repression motif to change a transcriptional activator to a suppressor has been broadly investigated through chimeric protein fusion assays[61,62]. ERF4.1/4.2 containing an EAR repression motif inhibits anthocyanin biosynthesis in red-skinned pears[35]. Subgroup 4 R2R3-CstMYB16 with EAR repression motif interacts with CstPIF4 to negatively control anthocyanin biosynthesis in Crocus[63]. Mutations or deletions of EAR motif in peach PpMYB18[40], petunia PhMYB27[43], grape VvMYB114[64], and apple MdMYB16[65] all lead to the decrease or the loss of repressor activity, thereby resulting in the biosynthesis of anthocyanins. It appears that the C1 and EAR motifs, especially the EAR motif, are key motifs for the repressive activity of TFs.

In addition to the C1/EAR motifs, the TLLLFR motif is considered another key repression motif, although the studies on this repression motif are less than those of the EAR motif. The TLLLFR repression motif is often present at the very end of TFs[66]. TLLLFR motif is identified in VvMYBC2-L1 and VvMYBC2-L3 in grape[51], AtMYBL2 in Arabidopsis[66], MaMYB4 in banana[67], PtMYB182 in poplar[68]. Notably, the VvMYBC2-L1, VvMYBC2-L3, and MaMYB4 contain C1, EAR, and TLLLFR repression motifs and repress the biosynthesis of anthocyanin in grapes and bananas, respectively[51,67]. However, the key repression motifs of VvMYBC2-L1, VvMYBC2-L3, and MaMYB4 responsible for the repressor activity are unclear[51]. AtMYBL2 is a key inhibitor of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Deletion of the TLLLFR motif results in the loss of the repression function of AtMYBL2[66]. The poplar subgroup 4 R2R3-PtMYB182 contains the bHLH-binding motif, C1, EAR, and TLLLFR motif, but the bHLH-binding motif instead of C1, EAR, and TLLLFR motif is the key motif for negatively regulating the biosynthesis of anthocyanins and proanthocyanins[68]. These studies indicate varied ability of the TLLLFF repression motif in different plants and the role of the TLLLFR motif needs to be further analyzed in various plants.

The C1, EAR, and TLLLFR motifs are crucial for the repressive activities of TFs to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis[40,59,66−68]. However, the repression mechanisms of TFs differ greatly among different plant species and the molecular basis of C1 and TLLLFR-mediated suppression is largely unknown. To date, only the mechanism of the EAR repression motif has been revealed. Current evidence indicates that the TFs containing EAR repression motif recruit the transcriptional co-repressors TOPLESS/TOPLESS-related (TPL/TPRs), which interact with histone deacetylases (HDAs) to repress gene expression of target locus[58,69−72]. Pear PpERF9 interacts with PpTPL1 via the EAR motif. The PpERF9-PpTPL1 complex induces histone deacetylation of PpRAP2.4 and PpMYB114 to reduce the expression of PpRAP2.4 and PpMYB114, thus repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis[73]. Under low red-to-far-red light, chrysanthemum CmMYB4 interacts with CmTPL via the EAR motif, and the CmMYB4-CmTPL complex deacetylates histone H3 of the anthocyanin activator CmbHLH2, resulting in reduction of anthocyanin biosynthesis in the petals[74].

Notably, similar regulation (TFs with EAR motif forming TF-TPL/TPRs-HDAs complexes) has also been identified in horticulture crops to affect fruit ripening and petal size. SlERF.F12 and MdERF4 interact with SlTPL2 and MdTPL4 through the EAR motif to recruit SlHDA1/3 and MdHDA19 to inhibit transcription of ripening genes in tomato and apple, respectively[75,76]. RhMYB73 recruits RhTPL and RhHDA19 to form a repression complex to regulate cytokinin catabolism in rose, thus modulating petal size[77]. Interestingly, banana MaERF11 directly interacts with MaHDA1 to inhibit banana fruit ripening[78], and Arabidopsis MYB96 directly interacts with HDA15 to inhibit negative modulators of ABA signaling and this process does not need TPL/TPRs as mediators to form the TFs-TPL/TPRs-HDAs repression complex[79]. Whether TFs directly interact with HDAs to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis needs more investigation (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, these studies reveal that TFs harboring EAR motif modulate transcriptional repression through histone deacetylation. Interestingly, some studies show TPL/TPRs also interact with histone methylation-linked chromatin remodelers, containing SUV39H-like protein (SUVH3) and PICKLE (PKL) CHD3/Mi-2-like chromatin remodeler-related protein (PKR1)[58,80]. Thus, it will be interesting to investigate whether TFs with EAR motifs utilize various chromatin-remodeling mechanisms to inhibit the expression of anthocyanin-related genes (Fig. 2).

A previous study indicates that the TLLLFR motif, similar to the EAR motif, is the interactor of TPL/TPRs[58]. This leads us to speculate whether the TLLLFR motif also has the same inhibitory mechanism as the EAR motif, or whether the TLLLFR motif interacts with unknown negative regulators to induce repression of their target genes. Another question regarding the repression motifs is whether there are other unidentified repression motifs and what are the function of these unknown repression motifs in horticultural crops (Fig. 2). For example, subgroup1 R2R3-MdMYB306-like inhibits anthocyanin synthesis in apple but lacks the C1, EAR, and TLLLFR repression motifs and the motif that induces the repressive function is still unknown[59].

-

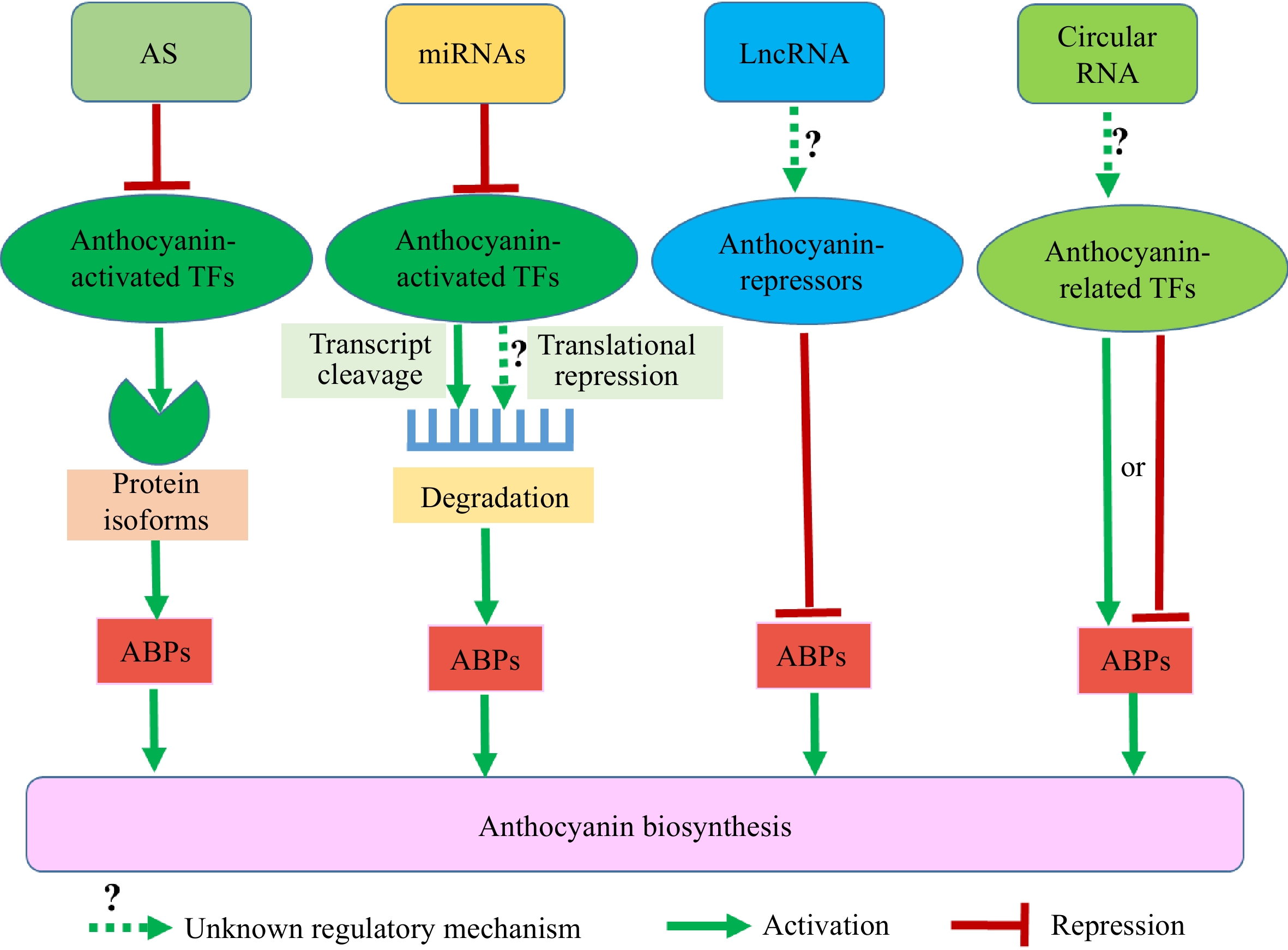

In addition to transcriptional regulation, many repressors are regulated at the posttranscriptional level to negatively regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis. Posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression includes alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) in plants. Alternative splicing regulates gene expression and produces greater transcriptome diversity, which plays crucial roles in plant development and responses to environmental cues[81−83]. Alternative splicing majorly includes exon skipping, intron retention, alternative 5' splicing, alternative 3' splicing, alternative 5' and 3' splicing, and mutually exclusive exon[83]. Among them, intron retention is the most common type of alternative splicing in plants[83]. With the advance of the high-throughput RNA sequencing technique, global changes in alternative splicing of diverse horticulture crops have been identified[84−90]. Compared with the Aft (Anthocyanin fruit) tomato, alternative splicing of an R2R3 MYB activator is responsible for the wild tomato species with low contents of anthocyanins[91]. In chrysanthemum, the cultivar 'OhBlang' generates different flower colors at different temperatures, which is related to the alternative splicing of CmbHLH2 to affect its interaction with CmMYB6 to reduce anthocyanin synthesis[92]. These studies document the role of alternative splicing in reducing the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in horticulture crops.

The ncRNAs provide another major mechanism of posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression in plants. ncRNAs can be divided into small interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), phased siRNA (phasiRNA), long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), and circular RNA[93]. The siRNA is generated from double-stranded RNA and plays a significant role in RNA silencing[94]. The bicolor petunia petals result from the accumulation of siRNAs of CHS-A gene. siRNAs of CHS-A are highly accumulated in the white part of the petals of bicolor petunias and lead to undetectable expression of CHS-A[94]. RNAi-mediated silencing of strawberry FaMYB1, a repressor of anthocyanin biosynthesis, produces a notable increase in the contents of anthocyanin[95]. The miRNAs along with their targets play significant regulatory roles in various biological processes by affecting gene expression[93,96−98]. Pear PySPL interacts with the MBW complex to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis. Under bagged and debagged treatment, PymiR156a regulates the cleavage of PySPL9 and blocks the formation of MBW complex by titrating MYB10 and MYB114 proteins, leading to increased anthocyanin biosynthesis in the skin of pear[99]. miR858 in tomato negatively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by suppressing the transcripts level of anthocyanin activator SlMYB7-like[100] and miR858 in the skin of apple inhibits the biosynthesis of proanthocyanidin by repressing the expression of MdMYB9/11/12[101]. In kiwifruit, miR828 and its phased small RNA AcTAS4-D4(−) target and cleave MYB110 instead of MYB10 (two MYB activators on anthocyanin production) to decrease anthocyanin biosynthesis, while miR156b, miR160a, miR171d, and miR394a target the repressive regulators of MYB10 and indirectly modulate the activity of MYB10 to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis[102]. The above studies indicate that miRNAs usually negatively modulate the transcript abundances by transcript cleavage. However, translational repression by miRNA in anthocyanin biosynthesis remains largely unclear (Fig. 3)[93].

Figure 3.

The types and mechanisms of posttranscriptional regulation of transcription factors (TFs) to negatively regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops. Alternative splicing of anthocyanin-activated TFs and miRNAs-mediated the cleavage of anthocyanin-activated TFs reduce anthocyanin biosynthesis. The translational repression by miRNA in anthocyanin biosynthesis, lncRNAs repressing the biosynthesis of anthocyanins, and circular RNA-mediated regulation of TFs affecting the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in horticulture crops need to be investigated further. AS is alternative splicing; ABPs are anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes.

In contrast to miRNAs, lncRNAs have lower sequence conservation in different species[103]. lncRNAs interact with different molecules to regulate their target genes at transcriptional, translational, or epigenetic levels[93]. lncRNAs also play crucial roles in anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticulture crops. Strawberry lncRNA FRILAI acts as the target mimics of miR397, thus protecting AC11a encoding a putative laccase-11-like protein from cleavage by miR397 to induce anthocyanin biosynthesis[104]. Apple lncRNAs MdLNC499 and MdLNC610 regulate light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis by promoting the expression of MdERF109 and MdACO1, respectively[105,106]. The long noncoding RNA LINC15957 promotes the biosynthesis of anthocyanin in radish, while the regulatory mechanism of LINC15957 on anthocyanin biosynthesis is unknown[107]. The lncRNAs repressing the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in horticulture crops await further identification. Additionally, numerous circRNAs have been identified in horticulture crops[108−113]. However, it is not well known how circular RNA-mediated regulation of TFs affects the biosynthesis of anthocyanins (Fig. 3).

-

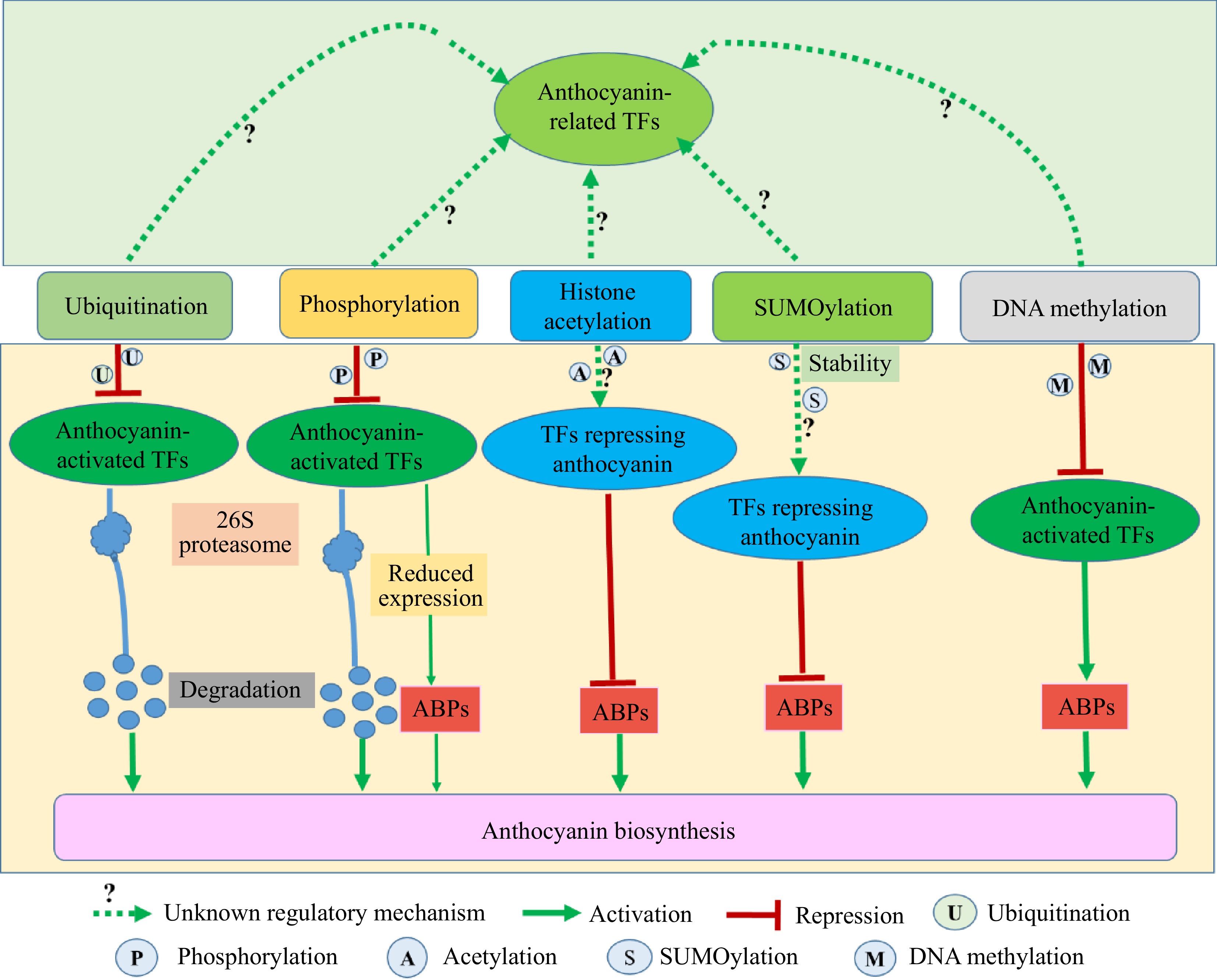

Post-translational modifications include ubiquitination, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and acetylation, which play crucial roles in various biological processes in plants[114]. Ubiquitination is a universal posttranslational modification in plants, which controls the degradation of target factors. Ubiquitination plays an essential role in plant biology[115]. Apple MdMYB1, a key factor promoting anthocyanin biosynthesis[116,117], interacts with the ubiquitin E3 ligase CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (MdCOP1) and RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase (MdMIEL1), respectively, and is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated degradation, thus resulting in inhibiting anthocyanin biosynthesis[116,117]. Similarly, apple MdMYB308L interacts with MdMIEL1 in the absence of cold stress[118], and pear PpbHLH64 and PpMYB10 interact with PpCOP1 under dark conditions[119], thereby repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis. In addition, apple MdSINA1(an E3 ubiquitin ligase) interacts with phosphate starvation response 1 (MdPHR1) mediating ubiquitination and degradation of MdPHR1 to inhibit anthocyanin biosynthesis under the inorganic phosphate sufficient condition[120]. Besides MdCOP1, MdMIEL1, and MdSINA1, apple bric-à-brac, tramtrack and broad complex 2 (MdBTB2) affects the stability of TFs (MdMYB9, MdBBX22, MdMYB1, MdTCP46, MdWRKY40, MdbZIP44, and MdERF38) to suppress anthocyanin biosynthesis[121−128]. BTB proteins are a link between substrate proteins and CUL3-RING E3 ligase, which is crucial for the ubiquitin process[121−123]. Tomato SlCSN5-2 interacts with SlBBX20 which is a transcript activator of anthocyanin biosynthesis to increase the ubiquitination of SlBBX20 and accelerate the degradation of SlBBX20, thereby reducing the biosynthesis of anthocyanins[129]. Thus, ubiquitination of the positive TFs in anthocyanin biosynthesis exerts a crucial role in negatively regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Protein phosphorylation is central to the regulation of protein stability, protein activity, protein-protein interactions, and subcellular localization[103,130]. Low temperature negatively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in strawberry fruit via activating FvMAPK3-mediated phosphorylation of FvMYB10 and FvCHS, resulting in a reduction in the expression of FvMYB10 and the degradation of FvCHS[131]. In Arabidopsis, AtSnRK1 inhibits the expression of MYB75 at the transcriptional level to suppress anthocyanin biosynthesis. AtSnRK1 also phosphorylates all the members of MBW complexes (MYB75, bHLH2, and TTG1) and results in dissociation of the complexes, MYB75 degradation, and TTG1 moving from nucleus to cytoplasm, thereby inhibiting anthocyanin biosynthesis[132]. In addition, many studies indicate phosphorylation of TFs positively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis via increasing TFs stability, thus promoting anthocyanin biosynthesis[130,133−136]. These studies suggest protein phosphorylation on protein function is complicated. Phosphorylation of TFs causes degradation of TFs, regulating the expression of TFs, dissociation of complexes, and translocation of TFs to regulate the function of TFs.

Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) widely exists in plants and SUMOylation influences various significant biological processes in plants, including abiotic and biotic stresses, plant development, plant nutrition, and secondary metabolism[137]. SUMOylation is a significant regulator in gene transcription via controlling the stability, activity, or subcellular localization of TFs in plants[22,136,138]. In apple, MdSIZ1, a small ubiquitin-like modifier E3 ligase, SUMOylates and stabilizes MdMYB1 to facilitate anthocyanin biosynthesis under low-temperature conditions[139]. MdMYB2 binds to the promoter of MdSIZ1 under low-temperature conditions, thus enhancing the anthocyanin biosynthesis via SUMOylation of MdMYB1 by interacting with MdSIZ[140]. In Arabidopsis, AtSIZ1 also SUMOylates AtMYB75 to improve its stability, resulting in increasing anthocyanin biosynthesis under high light conditions[141]. In addition, SUMOylation substrates contain activators and suppressors and SUMO conjugations are likely to promote or repress the activity of substrates[138]. The SUMOylation of TFs negatively modulating anthocyanin production needs to be explored further and the identification of other substrates SUMOylated by SIZ1 will enrich our understanding of SUMOylation on anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Histone acetylation also exerts important regulatory roles in anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticulture crops[73,74], although the regulation of histone acetylation directly on TFs repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis is still unclear (Fig. 4). Intriguingly, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) suppresses anthocyanin biosynthesis in red-skinned pears by persulfidation of MYB10 at Cys218 and Cys194[142], suggesting that additional novel modifications of TFs repressing anthocyanin production await identification in horticulture crops.

Figure 4.

The types and mechanisms of post-translation modifications of transcription factors (TFs) to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops. The top/light green background represents multiple post-translation modifications that may work cooperatively or competitively on the same TFs in horticultural crops. The bottom/light yellow background represents the mechanisms of post-translation modifications of TFs to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops. ABPs are anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes.

Collectively, post-translation modifications of TFs have crucial roles in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis and the mechanisms share a certain degree of similarity across different horticulture crops. Diverse post-translation modifications including ubiquitination, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and acetylation may work cooperatively or competitively on the same TFs, thus regulating the activity or stability of the target proteins (Fig. 4). Most studies focused on single TF mediated by post-translation modifications in horticulture crops and the genome-wide post-translation modifications remain to be investigated in further studies.

-

DNA methylation is a crucial epigenetic modification required for the silencing of transposable elements, gene regulation, genomic imprinting, and genome stability. DNA methylation occurs in cytosine residues of gene sequences and transposable elements: CG, CHG, and CHH (H = A, T, or C). Increased DNA methylation of the genes and transposable elements generally down-regulates gene expression[143−145]. DNA methylation of TFs controlling anthocyanin biosynthesis is intensely associated with color changes in some horticulture crops[103,136,144,146].

The differences in anthocyanin biosynthesis between red-fleshed and white-fleshed radish result from the altered methylation levels of transposon in the promoter of RsMYB1. The hypermethylation of transposon in the promoter of RsMYB1 of white-fleshed radish leads to a significant reduction in the expression of RsMYB1, thus inhibiting the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in white-fleshed radish[147]. The yellow-skin apple from somatic mutation of its red-skin parent is related to a highly methylated level of the promoter of MdMYB10[148]. Similarly, the methylation patterns of the promoter of MdMYB10 between red and green stripes apple[144], apple MdMYB1 under bagging and bag removal treatment[149,150], crabapple McMYB10 under phosphorus deficiency conditions[151], and PcMYB10 of green-skinned sports pear[152] are highly related to the biosynthesis of anthocyanin. The fruit skin color of the 'Zaosu' pear and its bud sport having red or red-striped skin color is related to the methylation of the PyMYB10 promoter[153]. However, another study shows the methylation levels of pear PyMYB10 have no significant difference between bagging and bag removal treatment[154]. These studies suggest the methylation levels of PyMYB10 induced by light and bud sport in pear are different and the reason for the difference awaits further investigation. The methylation of the promoter of grape VvMYBA1 is connected with the anthocyanin content of grape skin and high methylation level confers reduced anthocyanin biosynthesis[155]. Under cold stress, the same sweet orange fruits have high-pigmented and low-pigmented segments, which is associated with methylation levels of the promoter of DFR and Ruby (an R2R3 MYB transcriptional activator of anthocyanin biosynthesis)[156]. Lower methylation levels in the promoter of PpbHLH3 and some ABPs are associated with increased anthocyanin biosynthesis in the fruit of peach stored at 16 °C[157]. In strawberry, DNA methylation inhibitor treatment makes turning red earlier compared with the control. Further analysis indicates genes related to RNA-directed DNA methylation are decreased during strawberry fruit maturation[158]. In chrysanthemums, CmMYB6 is a positive regulator of anthocyanin[159], and the formation of yellow flowers is closely related to higher methylation levels of the CmMYB6 promoter compared with the pink flowers[160]. Most DNA methylation studies have focused on fruit crops and how DNA methylation controls anthocyanin production in vegetable crops is largely unknown[143].

-

Anthocyanins offer an attractive coloration to horticultural crops and play crucial roles in plants responding to different environments. Although tremendous advances have recently been achieved in identifying new TFs repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis and uncovering their molecular basis, many studies utilize heterologous plant systems and transient expression systems. Therefore, it is critical to investigate and verify the function and molecular mechanisms using more direct homologous systems in the future. In addition, anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops is under sophisticated regulatory control in response to environmental changes. How to utilize gene editing and other technologies to improve the anthocyanin content of horticultural crops by modifying the activities of repressors remains challenging. Many unresolved questions on TFs repressing anthocyanin production need to be further investigated. The conservation of TFs repressing anthocyanin production among different plant species needs to be analyzed. Furthermore, the mechanism of circular RNA-mediated regulation, the repressing mechanism of the EAR and TLLLFR motifs, and the identification of unknown repression motifs are awaiting further exploration. Novel regulatory controls of TFs repressing anthocyanin production need to be investigated. The interaction between TFs repressing anthocyanin production and environmental signals and the sophisticated regulations in horticultural crops (when to start it and when to remove it) is still not well-known. Answers to these questions will enrich the understanding of the regulatory controls of anthocyanin biosynthesis and lay a solid foundation for the designed quality improvement of horticultural crops.

This project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32272681, 32130092), sub-project of Liaoning Province Germplasm Innovation Grain Storage and Technology Special Program (2023JH1/10200003), and Shenyang Young and Middle-aged Science and Technology Innovation Talents Support Plan (RC220306).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: draft manuscript writing and figures preparation: Wu Z, Zhang J; literature search and manuscript proofreading: Bian R; manuscript revision: Zhang Z, Li L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wu Z, Bian R, Zhang Z, Li L, Zhang J. 2025. Transcription factors repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops. Fruit Research 5: e007 doi: 10.48130/frures-0024-0042

Transcription factors repressing anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops

- Received: 05 November 2024

- Revised: 20 December 2024

- Accepted: 23 December 2024

- Published online: 20 February 2025

Abstract: Anthocyanins are an important quality trait in horticultural crops. Transcription factors (TFs) play critical regulatory roles in the biosynthesis of anthocyanins. Many TFs are well-known as transcriptional activators of anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops, whereas TFs suppressing anthocyanin synthesis have recently been acknowledged. Here we focus on recent advances on the roles and mechanisms of TFs that negatively regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural crops. We discuss the TFs repressing the function of the activation complexes, the TFs regulating repressors, and the repression motifs, as well as posttranscriptional regulations, post-translation modifications, and methylation of TFs to repress anthocyanin biosynthesis. This information will provide insights into the future utilization of these TFs to improve the quality of horticultural crops.

-

Key words:

- Horticultural crops /

- Repression /

- Transcription factor /

- Anthocyanin biosynthesis