-

DNA methylation is the covalent addition of methyl groups to the fifth carbon position of cytosine residues, predominantly occurring at CpG dinucleotides in mammalian genomes. This epigenetic modification was first identified by Rollin Hotchkiss in 1948, who observed methylated cytosines in calf thymus DNA, inaugurating the study of DNA modifications[1]. Subsequent research has firmly established DNA methylation as a pivotal regulator of gene expression, chromatin structure, X chromosome inactivation, genomic imprinting, and transposon silencing[2−7]. The establishment of methylation patterns is primarily driven by the de novo methyltransferases 3A (DNMT3A) and 3B (DNMT3B)[8,9], while DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) maintains existing methylation patterns during DNA replication[10]. Active DNA demethylation, conversely, involves TET family dioxygenases, which progressively oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), with 5fC and 5caC subsequently removed via base excision repair pathways[11]. In livestock, DNA methylation has been extensively reported to be associated with semen quality[12], muscle development[13], fat metabolism[14], immune regulation[15], and disease susceptibility[16]. The elucidation of DNA methylation landscapes underlying key phenotypes drives a shift in livestock research from genomics to epigenomics.

Livestock and poultry species, such as pigs, cattle, and chickens, are crucial for global food consumption, economic sustainability, and fundamental biological insights[17,18]. DNA methylation in these species influences critical traits, including growth rate[19−21], meat quality[22−24], reproductive performance[25−27], and environmental adaptation[28−30]. With rapid advancements in genomic and epigenomic technologies, a comprehensive synthesis of current DNA methylation knowledge in livestock is necessary. Over the past few decades, methylation detection methods have evolved from early restriction enzyme-based assays and bisulfite conversion techniques to advanced third-generation sequencing platforms. These technological breakthroughs have expanded the scope of methylation research, influenced diverse fields, and highlighted DNA methylation's broad relevance and applicability.

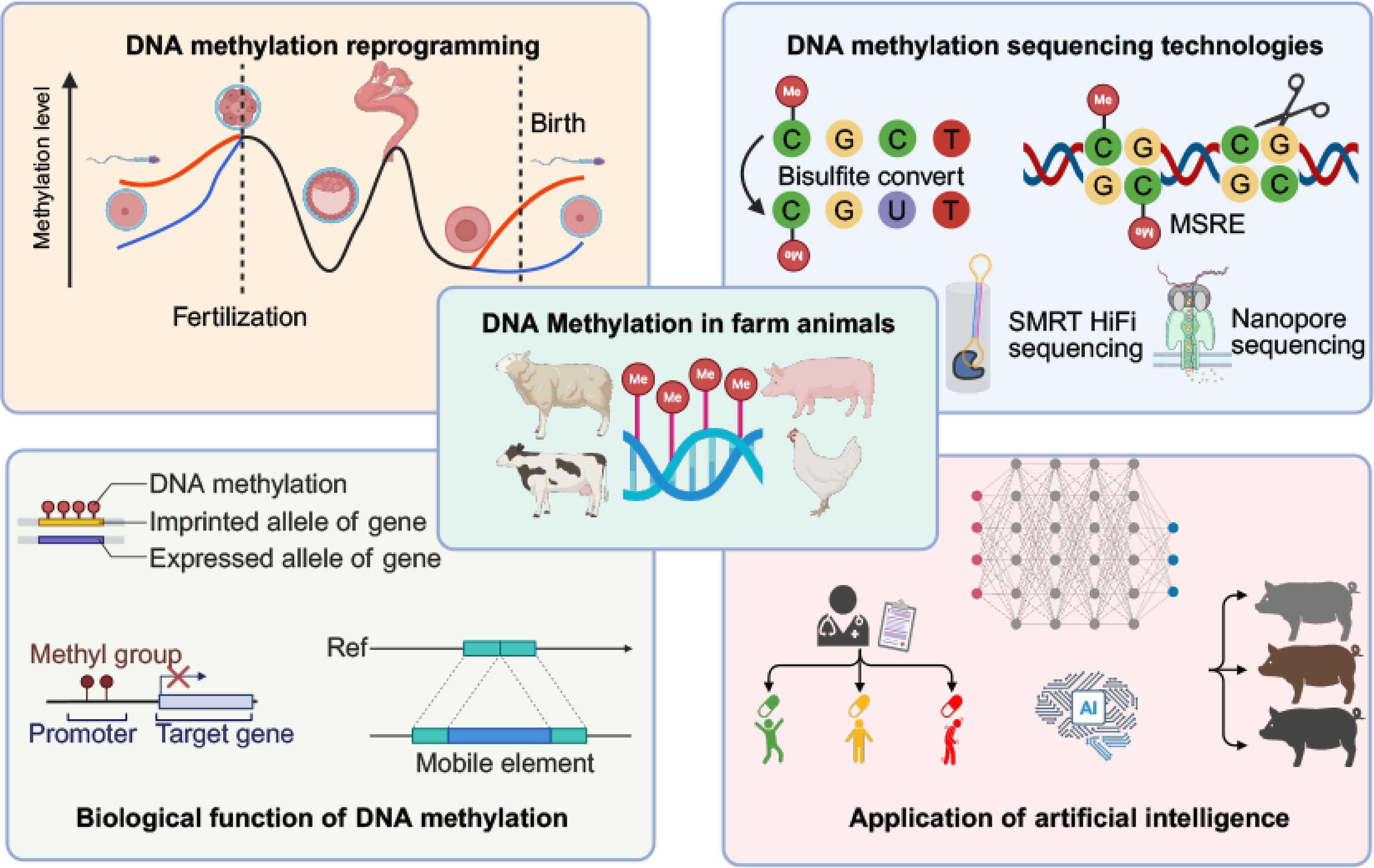

This review systematically summarizes recent advances in DNA methylation research in livestock, emphasizing how state-of-the-art technologies are shaping future research trajectories (Fig. 1). Furthermore, it offers an in-depth overview of the diverse biological functions governed by DNA methylation. The integration of emerging methodologies provides novel insights into epigenetic mechanisms, paving the way for transformative applications in biological models, optimized livestock breeding, and environmental adaptation.

-

Recent studies have provided valuable insights into DNA methylation reprogramming in livestock. DNA methylation reprogramming primarily involves two critical stages: erasure of methylation patterns during gametogenesis and extensive demethylation followed by de novo methylation during early embryonic development. In pig primordial germ cells, the major wave of DNA demethylation occurs before day 28, with males and females showing similar timing and reaching a comparable minimum of about 5% around day 36[31]. During remethylation from day 39 to day 42, sex-biased persistently methylated regions emerge, enriched for short interspersed nuclear element (SINE), long interspersed nuclear element (LINE), and Long Terminal Repeat (LTR) in males, whereas more often promoter-associated in females[31]. Re-established DNA methylation in mature gametes profoundly shapes gamete quality, fertilization potential, and offspring phenotypes[32,33]. Beyond its association with sperm quality and DNA integrity, DNA methylation can discriminate between high- and low-fertility boars and bulls[26,34,35]. This suggests the use of methylation markers to identify and select individuals with high reproductive performance in production. After fertilization, the paternal genome undergoes rapid ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 3 (TET3)-mediated active demethylation at the pronuclear stage, whereas the maternal genome is demethylated passively in a replication-dependent manner across the early cleavage divisions, culminating in a globally hypomethylated blastocyst[36,37]. Remethylation in pigs occurs peri-implantation: after the globally hypomethylated blastocyst, DNMT3A/3B rebuild CpG methylation, producing higher levels in the epiblast than extraembryonic lineages[36,38]. Despite these general patterns, significant species-specific variations in demethylation dynamics and underlying mechanisms have been observed, highlighting the need for detailed comparative studies[36]. This remethylating phase is crucial for normal embryonic development, lineage commitment, and cell differentiation, subsequently influencing important traits such as growth rate, meat quality, and production efficiency in livestock[39]. Although DNA methylation reprogramming is well characterized in model organisms, its causal links to livestock traits and sustainable development remain unclear. Resolving these links will require large-scale, rigorously designed, systematic studies.

Although genome-wide erasure and rebuilding of CpG methylation occur during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis, growing evidence in livestock shows that some environment-induced marks in gametes can escape reprogramming or be reinstated after fertilization, and are linked to offspring phenotypes[40−42]. Nutritional interventions altering methyl-donor supply in sires remodel methylation at TBR1 and IYD promoters in muscle and liver, and are associated with shifts in offspring growth and adiposity[42]. Embryonic heat conditioning in chickens yields progeny with improved thermal tolerance and altered immune performance, with methylation changes enriched at enhancers and CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF)-anchored sites near heat-response regulators[43,44]. Sheep experiments indicate that prepubertal methionine supplementation in F0 rams, remodels the sperm methylome and yields growth and reproductive differences in unexposed offspring. Related methylation and phenotypic signals persisted to F3 and F4 in a paternal-lineage design, consistent with transgenerational inheritance of diet-induced gametic marks[45,46]. These observations open practical avenues but require caution. Reported effects are context dependent, and they remain intergenerational associations rather than definitive transgenerational inheritance in many cases. Moreover, maternal influences, genetic background, and management can mimic heritable signals. Technical and statistical limitations, including small sample sizes, batch and measurement effects in methylome profiling, and incomplete control of genetic confounding, further temper inference. Some studies also lack randomized, multigeneration, lineage restricted designs that can isolate gametic from postnatal and environmental pathways, such as embryo transfer, cross-fostering, and split ejaculate artificial insemination[47,48]. We therefore see value in pilot integration of native long read methylome profiling of sperm and oocytes within breeding pipelines, coupled to preregistered analyses that link candidate marks to gene expression and target traits, and tests of persistence beyond F2 under randomized and controlled designs. In this framework, environmentally responsive methylation is treated as a measured and evidence-based layer that complements and does not replace genomic selection. Therefore, current evidence supports a cautious view that environmentally responsive gametic methylation can contribute to between-generation phenotypic variation, while its truly transgenerational inheritance remains to be demonstrated rigorously.

-

DNA methylation critically influences gene expression by modulating genome accessibility to transcriptional machinery. In mammalian cells, methylation at promoter regions, particularly CpG islands, generally leads to transcriptional repression[49]. Methylated promoters inhibit transcription factor binding and recruit methyl-CpG-binding proteins that mediate chromatin condensation, thereby silencing gene expression[50]. In low-altitude Xizang pigs, SIN3A mRNA is increased in the longissimus dorsi muscle and its promoter is hypomethylated, suggesting that DNA methylation contributes to the transcriptional changes underlying low-altitude adaptation[28]. A study of piglet placental tissue identified 88 differentially methylated-differentially expressed genes (DM-DEGs) whose promoter hypermethylation was inversely correlated with transcript levels, highlighting DNA-methylation-regulated candidates that may support placental development[51]. Consistent with this pattern, heat-stress-related genes in chickens also show a negative association between promoter methylation and transcript levels[52]. However, the relationship between gene body DNA methylation and gene expression is highly complex. Gene body methylation suppresses spurious transcription initiation from cryptic internal promoters and facilitates transcriptional elongation[53]. Furthermore, gene body methylation influences alternative splicing by modulating RNA polymerase II kinetics and chromatin architecture[54]. Consistent with these observations, methylation within gene bodies was positively correlated with gene expression in studies of pregnant cattle and sheep[55]. Conversely, gene body methylation is negatively correlated with gene expression in the great tit[56,57]. At single-cell resolution, joint methylome and transcriptome sequencing in pigs showed an association between DNA methylation and gene expression during meiotic resumption and oocyte maturation[58]. In cattle, single-cell joint profiling that contrasted in vivo with in vitro maturation identified coordinated pairs of differentially methylated regions and differentially expressed genes[59]. These pairs showed promoter hypermethylation with downregulation, and state-dependent positive coupling at gene bodies and distal enhancers[58,59]. Beyond livestock, the same section spatial methylome and transcriptome maps in mouse confirm the canonical promoter methylation and expression anticorrelation, and reveal context-dependent gene body coupling that is often positive or nonlinear, informing future livestock studies[60]. Collectively, these findings underscore the versatile, context-specific roles of DNA methylation in modulating gene expression. Moreover, we propose mitigating single-cell tissue heterogeneity in livestock by first anchoring cell states with scRNA-seq and mapping them onto spatial atlases via spot deconvolution or cell-to-space alignment. Cell-type-specific differentially methylated region (DMR) methylation signatures are then projected onto tissue coordinates using promoter-, enhancer-, and gene body-aware models, and validate key loci in trait-relevant niches. Looking ahead, building a genome-wide, multi-tissue, multi-stage DNA methylation-transcriptome atlas for livestock will be essential for linking epigenetic regulation to health, welfare, and economically relevant traits.

Another fundamental function of DNA methylation is the regulation of parent-of-origin-specific gene expression through genomic imprinting, and the dosage compensation of sex chromosomes via X chromosome inactivation (XCI)[61]. Genomic imprinting results in the selective expression of either maternal or paternal alleles, controlled by differentially methylated regions established during gametogenesis, and maintained throughout embryonic development[62]. In a study of Duroc and Yunnan small-ear pigs, researchers identified 11 paternally expressed and five maternally expressed imprinted genes. Notably, the development-related genes KCNQ1 and IGF2R exhibit imprinting patterns in pigs that diverge from those observed in mice and humans[63]. The ZNF791 gene was reported to have lineage-specific imprinting, which was imprinted exclusively in domesticated species (cattle, sheep, goats, horses, and dogs), but not in humans or rodents[64]. Research on the IGF2 gene in chickens has yielded conflicting results[65−68]. While some studies suggest that the expressed allele can originate from either the paternal or maternal lineage[65], others report bi-allelic expression[66−68]. Furthermore, numerous studies have concluded that genomic imprinting is absent in chickens[69−71]. In livestock, XCI is initiated through multiple mechanisms. For example, the X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) DMR lacks pre-existing methylation in pigs, leading to a distinctive pattern of random XCI after XIST activation that contrasts with the mouse model[72,73]. Dysregulation of XCI driven or sustained by aberrant DNA methylation in livestock is commonly associated with reduced embryonic viability, placental dysfunction, and diminished somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) efficiency[74−76]. Among artiodactyls, cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs share a unique XCI escapee, the gene KDM5C, while compared with genes subject to inactivation, escape genes show stronger CTCF occupancy, higher Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) accessibility, and enrichment for LTR[77]. Altogether, these insights highlight imprinting and XCI as both a liability when misregulated and a lever when monitored, for improving embryonic viability and sex-specific performance in breeding programs.

Beyond gene regulation and imprinting, DNA methylation plays an essential role in maintaining genome integrity by silencing repetitive sequences and transposable elements (TEs). Mammalian genomes contain numerous TEs, which are heavily methylated to prevent their mobilization, thereby minimizing insertional mutagenesis and genomic instability[78]. On one hand, TE activity contributes significantly to genomic evolution and organismal diversity[78−81]. Four distinct pig-specific LINE-1 families have been identified, each reflecting a unique evolutionary trajectory, alongside three pig-specific SINE amplification waves represented by three separate SINE families. These TEs exert widespread effects on both lncRNAs and protein-coding genes at the genomic and transcriptomic levels[82]. On the other hand, maintaining epigenetic silencing is particularly vital during early embryogenesis and in germline cells, as loss of methylation can activate TEs, resulting in detrimental consequences[83]. In chickens and cattle, hypomethylation of endogenous transposable elements, avian leukosis virus endogenous (ALVE) in chickens, and placental endogenous retroviruses (ERV) in cattle, is associated with reduced egg production, abnormal placentation, and lower calf survival[84−86]. Together, livestock studies show that DNA-methylation-mediated TE repression is a core genome-defense layer, and when it relaxes globally or locally at particular ERVs, TE activity can compromise development and fitness. Lineage-specific TEs in livestock not only shape gene regulation but also have the potential to undermine genome stability. Integrating pangenome maps with methylome profiling and TE-informed expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) across tissues and stages will pinpoint functional insertions, link them to production and fertility traits, and provide support for breeding and biosecurity.

In summary, DNA methylation's diverse functions, from transcriptional regulation and genomic imprinting to the preservation of genome integrity, highlight its central importance in cellular function and organismal health. The precise establishment and dynamic remodeling of methylation patterns during development are thus critical, forming the foundation for tissue-specific epigenetic landscapes and developmental potential in livestock.

-

Several methodologies have been developed to study DNA methylation, predominantly utilizing short-read sequencing. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) has been the gold standard since 2009, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, read as thymine during sequencing, thereby enabling discrimination of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) from unmethylated cytosine.[87]. Despite its accuracy, WGBS requires over 1 µg of high-quality genomic DNA and often results in extensive DNA damage, incurring high sequencing costs and computational complexities[88]. A traditional pig population study applied this method to analyze the contribution of the DNA methylation atlas to complex traits, identify breed- and sex-associated differentially methylated regions, and lay a solid foundation for exploring the epigenetic mechanisms of fat deposition and muscle growth[89]. WGBS has laid the foundation for many livestock epigenomic studies, providing base-resolution methylome data for animals such as pigs, cattle, and chickens, enabling the construction of population-scale and multi-tissue maps (Table 1). Alternatively, reduced-representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) leverages enzymatic digestion with MspI to enrich CpG-rich genomic regions, sequencing approximately 5%–10% of the genome[90]. This approach has uncovered epigenetic mechanisms of adipogenesis and myogenesis in pigs, and established tissue differentiation as a principal driver of methylation variation[91,92]. Although this method has greatly reduced sequencing volume and cost, it cannot interrogate genomic regions lacking MspI sites, because those regions remain in fragments too large to pass the size-selection window and are thus excluded from sequencing[93]. Additionally, both WGBS and RRBS fail to differentiate between 5mC and 5hmC, which serves as an intermediate of active DNA demethylation and participates in regulating tissue-specific gene expression[94]. Oxidative bisulfite sequencing (oxBS-seq) overcomes this limitation by first oxidizing 5hmC to 5fC before bisulfite conversion, while Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing (TAB-seq) selectively protects 5hmC via β-glucosylation, allowing distinct detection of both modifications[95−98]. Despite their near-base-pair resolution, WGBS, RRBS, and other short-read assays suffer from mapping ambiguity and coverage bias in repetitive regions, cannot resolve long-range haplotype-specific methylation or TE insertions, and typically do not distinguish 5mC from 5hmC, yielding incomplete or biased methylomes.

Table 1. Application of high-throughput methylation detection technology in livestock.

Breeds Year Tissues Methods Findings Duroc[92] 2015 Fat, heart, kidney, liver, lung, lymph node, muscle, and spleen WGBS Adult pig methylomes closely resemble human, supporting biomedical relevance Landrace pigs[13] 2021 Longissimus dorsi WGBS Dynamic DNA methylation coordinates TF access and gene programs to drive porcine skeletal muscle development Ross308 chicken[99] 2021 Jejunum, ileum, breast muscle, spleen WGBS A multi-tissue WGBS-based methylation clock predicts broiler age and health Holstein cows[100] 2020 Mammary glands, whole blood cells, prefrontal cortex of the brain, and semen straws WGBS Multi-tissue methylation analyses show global and tissue-specific methylation patterns Meishan and Duroc[101] 2022 Testes MeDIP-seq LDHC promoter demethylation activates expression during porcine testis maturation F1 crossbreeds of Korean native and Yorkshire breeds[102] 2022 Abdominal fats MBD-seq Nanopore methylomes identify cattle age-related DMRs and pathways Holstein cows[103] 2023 Whole blood cells ONT Low-pass nanopore enables accurate genomic prediction plus simultaneous methylation profiling Huxu chicken[104] 2023 Muscle ONT Dot chromosomes and the W chromosome are hypermethylated, whereas centromere cores are relatively hypomethylated in Huxu chicken Göttingen minipigs[105] 2022 Whole blood cells ONT Nanopore cfDNA profiling in minipigs found 1,236 obesity DMRs, implicating PPARGC1B and metabolic pathways Brahman, Droughtmaster, and Tropical Composite[106] 2021 Tail hair ONT Portable ONT tail-hair CpG methylation profiles enabled a cattle epigenetic clock predicting age with ~0.71 correlation Note: Representative studies of different sequencing methods. Enzyme-based assays and affinity enrichment methods represent practical, cost-effective alternatives for DNA methylation profiling. Methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme (MSRE) methods such as MSRE-qPCR and MSRE-seq rapidly assess DNA methylation by enzymatic cleavage at specific sites, though their resolution is limited by uneven genomic distribution[107,108]. Affinity enrichment approaches, including methylated DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeDIP-seq) and methyl-CpG-binding domain sequencing (MBD-seq), capture methylated DNA fragments using anti-5mC antibodies or methyl-CpG-binding proteins. These methods efficiently handle low-input or fragmented DNA samples but provide only regional-level resolution and semi-quantitative measurements due to CpG-density biases[109,110]. Such techniques are well-suited for large-scale population screens and validation studies when high-depth bisulfite sequencing is impractical due to sample quality, quantity, or budget constraints.

The advent of single-molecule long-read sequencing technologies has transformed DNA methylation analysis from destructive bisulfite-based chemistries to direct, native-signal detection. Third-generation platforms, primarily represented by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), eliminate PCR amplification and harsh chemical treatments, providing multi-kilobase reads combined with simultaneous detection of epigenetic modifications.

PacBio's single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, especially the high-fidelity (HiFi) mode, has become essential for native DNA methylation analysis in complex genomes. The SMRT sequencing monitors real-time polymerase kinetics (inter-pulse duration, IPD, and pulse width, PW) during replication of circularized DNA molecules, detecting methylation at single-base resolution[111]. Using the Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) algorithm, SMRT sequencing achieves exceptional accuracy (≥ 99.8%) for 15–25 kb reads[112]. Bayesian inference and deep-learning classifiers analyze IPD/PW deviations, reliably distinguishing methylation states such as 5mC and 5hmC[111,113]. Specialized tools developed for HiFi reads include AgIn, the holistic kinetic (HK) model, primrose, and ccsmeth. AgIn aggregates kinetic signals from neighboring CpG sites, enhancing calls in repetitive regions but without distinguishing modification types[114]. HK model, primrose, and ccsmeth apply deep learning to interpret complex kinetic and sequence context patterns, providing robust sensitivity across diverse genomic regions but necessitating extensive training data and computational resources[115−117]. At present, PacBio long-read sequencing provides the most effective strategy for achieving telomere-to-telomere (T2T) genome assemblies[118−120], with few studies on methylation analysis. In livestock, PacBio long-read sequencing has facilitated the generation of near-complete, chromosome-level genome assemblies, haplotype-resolved genomes, and comprehensive structural variant analyses, thereby advancing research on genetic architecture, trait-associated genes, and evolutionary adaptation[121−124]. So far, PacBio technology has not been found to be widely used in the mapping of DNA methylation maps of livestock, except for platform benchmarking on pigs and quail[125] and the T2T genome assembly research of sheep, which uses DNA methylation from HiFi reads to characterize the centromere region of chromosomes[126]. Nevertheless, PacBio's high accuracy (> 90%) positions it as a powerful method for future epigenetic studies[117,127].

ONT sequencing, another prominent long-read technology, identifies DNA methylation through real-time measurement of ionic-current fluctuations as DNA traverse protein nanopores. Current base-callers simultaneously decode nucleotide sequences and per-base methylation probabilities, enabling direct detection of 5mC, 5hmC, and 6-methyladenine (6mA) without additional chemical steps[128,129]. Accuracy assessments consistently demonstrate that ONT methylation detection surpasses 90% accuracy[130−134]. With the update of the chemical methods (R10.4) for ONT sequencing, the currently compatible callers include Guppy[135], Dorado[136], DeepMod2[133], f5c[137], and Rockfish[132]. Basecallers like Guppy and Dorado perform 'one-step' modified-base calling by directly embedding methylation tags into FASTQ outputs, offering high integration and official support but tightly coupling performance to model updates for new chemistries[135,136]. Signal-level callers such as f5c and Rockfish extract kinetic features from raw current traces post-alignment, yielding high precision but requiring extensive computational processing[132,137]. Deep-learning methods such as DeepMod2 offer end-to-end neural network solutions for high-precision methylation detection, particularly beneficial in complex and noisy datasets, albeit with substantial training and computational demands[133]. The long-read capabilities of ONT have enabled innovative applications, such as haplotype-resolved DNA methylation structural variation, and genomic variation drives the correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression[6]. Indeed, nanopore long-read sequencing has been widely applied in agricultural animals, ranging from constructing epigenetic clocks and identifying trait- or lineage-specific methylation and regulatory variants to uncovering epigenetic mechanisms underlying disease risk, hybrid regulatory architecture, and transgenerational effects (Table 1). Moreover, ONT sequencing has the ability to perform genome assembly, mitochondrial genome characterization, transcriptome profiling, alternative splicing detection, and epigenetic modification analysis, greatly advancing the understanding of genetic regulation, breed-specific traits, and production-relevant phenotypes[105,138−141]. These applications mean ONT sequencing has the potential to address epigenomics beyond genomics study.

Collectively, third-generation sequencing technologies like PacBio HiFi and ONT nanopore, capable of native methylation detection in long DNA reads, promise to revolutionize multiple scientific domains. Developmental biology studies may leverage phased methylomes to dissect epigenetic pattern establishment in early embryos and stem cells. In agricultural sciences, linking haplotype-resolved methylation patterns with structural variations may significantly advance selective breeding programs targeting traits such as tolerance, feed efficiency, and disease resistance.

-

Recent progress in CRISPR-guided epigenome editing enables precise gain or loss of CpG methylation in livestock systems[142−144]. A nuclease-inactive Cas9 fused to DNMT3A or DNMT3L installs methylation at selected promoters and enhancers[143]. A fusion with the catalytic domain of TET1 erases methylation and reactivates transcription[145]. Proof of concept in porcine fetal fibroblasts shows that targeted demethylation near FBN1 restores expression and remains stable across passages[144]. Research in porcine oocyte editing shows that demethylation at MTNR1A during in vitro maturation improves cumulus expansion, maturation, cleavage, and blastocyst yield[146]. In chicken, cell platforms demonstrate efficient CRISPR-based transcriptional control and robust TET1 activity, which opens a path to methylation editing in avian embryos[147]. SunTag-based recruitment together with CRISPRoff or CRISPRon architectures increases on-target epigenetic editing efficiency and can yield durable silencing or activation, while generally causing fewer genome-wide off-target changes than untargeted epigenetic treatments[143,148]. These systems can be delivered through plasmid, mRNA electroporation, ribonucleoprotein formats, or zygote microinjection[149]. Readouts include targeted bisulfite amplicons, long read native methylation, matched RNA profiles, and persistence tests across passages or early embryonic stages[150]. Off-target auditing uses guide prediction, amplicon sequencing at candidate sites, and whole-genome methylome scans[151].

These molecular biology technologies can help to bridge the gap in how methylation regulation is linked to traits. They allow direct causal tests at candidate enhancers and promoters that map from eQTL and DMR screens[145]. They support prototypes for precision breeding that tune gene activity without altering DNA sequence[148]. Targets include fertility genes, heat response circuits, immune regulators, and imprinted domains. Editing can rescue suboptimal methylation in embryos and may improve cloning and embryo transfer outcomes[146]. Integration with long read sequencing gives haplotype-resolved methylation and structural context, and coupling with machine learning sharpens guide design, predicts off-target risk, and ranks the smallest edit set. Together, these advances position 'epigenetic engineering' as an interesting route to faster validation, safer intervention, and trait tuning that is reversible, stage-specific, and compatible with modern breeding pipelines.

-

Machine learning frameworks are increasingly integrating DNA methylation data with complementary omics layers, including transcriptomics, chromatin accessibility, proteomics, and 3D genome architecture, to uncover regulatory relationships that remain hidden within single-modality assays. Multi-Omics Factor Analysis v2 (MOFA+), for example, employs a variational autoencoder-based approach to jointly analyze bulk DNA methylation, RNA-seq, and ATAC-seq data, generating latent factors that correct batch effects and capture both shared and modality-specific signals[152]. This method has been used to stratify chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients into prognostic subgroups based on methylation-expression axes explaining over 60% of joint variance (p < 0.01)[152]. Another multimodal deep generative model, the single-cell Multi-View Profiler (scMVP), applies a self-supervised Transformer to embed scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data into a unified low-dimensional space for clustering and imputation, and it can be adapted to integrate other epigenomic modalities, including DNA methylation, transcription factor occupancy, and spatial chromatin interactions[153,154]. Similarly, the deep learning model INTERACT combines convolutional neural networks with transformer architectures to predict the effects of genetic variation on CpG methylation levels in the human brain[155]. Collectively, these approaches exemplify how artificial intelligence (AI)-driven multi-omics integration can elucidate the functional consequences of DNA methylation, and these frameworks hold considerable promise for livestock applications using omics and trait records with rich metadata.

AI has rapidly become a driving force in DNA methylation research, enabling both mechanistic insights and translational applications. Clinically, machine learning, particularly deep learning frameworks like MethylNet, has been applied to methylation data to classify cancer types, predict heart failure, deconvolute cell types, subtype tumors, estimate age, infer smoking status, investigate psychiatric epigenetics, and improve Alzheimer's risk prediction[155−160]. In agricultural epigenomics, AI is being applied to impute DNA methylation patterns and classify livestock breeds based on methylation fingerprints. For instance, CMImpute, a conditional variational autoencoder, learns species- and tissue-specific methylation patterns to enable accurate imputation in underrepresented mammalian species-tissue combinations[161]. Emerging workflows translating methylation-based breed classification into practical applications are paving the way for genetic resource conservation, precision breeding, and food safety traceability.

AI is no longer a peripheral tool but a core enabler of modern DNA methylation research, facilitating everything from single-base modification detection to integrative multi-omics interpretation. Deep learning frameworks replace traditional statistical models, enabling high-resolution methylome mapping, regulatory network inference, and predictive modeling. AI-assisted epigenomics is accelerating the fusion of DNA methylation with transcriptomics, chromatin accessibility, proteomics, and 3D genome structure. Foundation models trained on large-scale multi-omics data, real-time methylation calling within sequencing platforms, and interpretable AI for epigenome editing will deepen the integration of AI and epigenetics. These advances will move the field toward actionable, mechanistically grounded insights for biology and agriculture.

-

Over the past two decades, DNA-methylation research has moved from locus-specific PCR assays to base-resolved, genome-wide maps illuminating development, disease, and adaptation. The advent of third-generation sequencing platforms, particularly PacBio HiFi and ONT, has further advanced the field by enabling direct, single-molecule detection of native methylation states, haplotype phasing, and structural variants, capabilities beyond the reach of traditional bisulfite-based methods. At the same time, the rapid evolution of AI has transformed how methylation data are decoded, interpreted, and integrated with other omics layers. Deep learning models, such as DeepMod2, now underly most base-level methylation callers, significantly improving both accuracy and throughput. Moreover, AI frameworks have begun to unify methylation with transcriptomics, chromatin accessibility, proteomics, and 3D genome architecture, revealing multi-layered regulatory axes that were previously invisible. These advances are accelerating applications in diverse fields, from early cancer detection and neurological disease research, to animal breeding and environmental adaptation. Looking forward, five key directions are anticipated to shape the future of DNA methylation research: (1) standardized benchmarking frameworks across species, tissues, sequencing chemistries, and computational tools to ensure reproducibility and comparability; (2) scalable, integrative multi-omics pipelines that jointly model genome sequence, chromatin state, transcriptome, and methylation profiles; (3) single-cell and spatially resolved methylation profiling using barcoded long-read strategies to resolve cell-type-specific and regional epigenetic heterogeneity; (4) distinguish 5mC from 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC, and deeply understand the role of specific methylation in the cell, (5) application of epigenetic engineering in animal breeding, and (6) interpretable and causally-informative AI models, moving beyond classification toward regulatory inference and clinical decision support. By combining long-read sequencing and intelligent computation, the next generation of epigenomic research will offer more precise insights into how methylation shapes phenotype, advancing both basic biology and practical outcomes in developmental biology and agricultural genomics.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFF1000600), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KCXFZ20230731094302006), the Terminal Sire Breeding Project (SJ202206), and the Key Research and Development project in Hechi City (Heke-AB240709). The author, Lingsen Zeng, is grateful for the financial support provided by the Program of China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 202403250098).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yi G; draft manuscript preparation: Zeng L, Li X, Groenen MAM, Gòdia M, Derks FLM, Yi G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng L, Li X, Groenen MAM, Gòdia M, Derks MFL, et al. 2025. Beyond genomics to epigenomics: emerging frontiers of DNA methylation in livestock. Genomics Communications 2: e024 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0024

Beyond genomics to epigenomics: emerging frontiers of DNA methylation in livestock

- Received: 18 August 2025

- Revised: 10 October 2025

- Accepted: 06 November 2025

- Published online: 12 December 2025

Abstract: DNA methylation influences gene regulation and economically important traits in livestock, yet many reviews remain descriptive and biased toward short-read analyses. This review characterized various biological functions of DNA methylation in cellular development, reprogramming, transgenerational inheritance, and economic traits by reshaping gene and chromatin patterns and genomic imprinting in livestock. DNA methylation detection technologies are further appraised, and the advantages of native long-read sequencing with PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore highlighted. Meanwhile, the fact that epigenome editing showed significant potential in precision breeding without changing genomic sequences is presented. Finally, artificial intelligence is described as an enabler of modified base calling, multi-omics integration, and interpretable decision support for livestock research. This review summarizes advances in DNA methylation in livestock and discusses future directions.

-

Key words:

- 5mC /

- DNA methylation /

- Long-read sequencing /

- Epigenomics /

- Livestock