-

High soil salinity and waterlogging are major obstacles in turfgrass management[1]. Excessive salt in water, deficit irrigation and precipitation, and the use of high salt fertilizers can cause salinity stress, resulting in osmotic stress (i.e., physiological drought) and ion toxicity and imbalance. Waterlogging often occurs due to over-irrigation, particularly during turf establishment when frequent irrigation is needed in summer, or intense rainfall in short time periods[2,3]. Under waterlogging conditions, air exchange between the soil and the atmosphere is reduced, causing O2 deficiency. Plants revert to fermentation under waterlogging, resulting in reduced energy production[4]. Waterlogging may also be seen in sodium-affected soils that are prone to swelling, dispersion, and crusting, resulting in a reduced water infiltration rate[5].

Kentucky bluegrass (KBG) is one of the most commonly used cool-season turfgrass species in the United States because of its dark green color, rhizomatous growth habit, and high freezing tolerance. Kentucky bluegrass is known to be salt-sensitive among common cool-season turfgrass species[6], but it is moderately tolerant to waterlogging[7]. Plants are generally more sensitive to environmental stresses at the seed germination and seedling stage compared to the mature stage[8]. Research found that seed priming is a promising technique to improve germination and later growth under both normal and stressful conditions[9].

Seed priming is the process of controlled seed hydration followed by a drying process inhibiting radical protrusion[10,11]. Seeds undergo partial imbibition and lag phase (controlled hydration), and experience low level heat stress (i.e., drying) and water stress (induced by priming agents other than water) through priming. In the course of priming, seeds exercise physiological and biochemical activities, such as synthesis of nucleic acids and proteins, ATP production, accumulation of sterols and phospholipids, and activation of DNA repair and antioxidant mechanisms that also take place in plants during germination and adverse conditions. Thus, primed seeds may advance in germination and stress tolerance. Kaya et al.[12] reported faster germination and better seedling growth in KNO3- and hydroprimed (i.e., primed with water) sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) seeds than unprimed ones under drought and saline conditions. Farooq et al.[13] found that seed priming with glycinebetaine (GB) increased the chilling tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.). Similarly, Zhang & Rue[8] reported enhanced osmotic and salinity tolerance in GB-primed turfgrass seeds. Compared to other environmental conditions, such as drought and salinity, the effects of seed priming on waterlogging tolerance are scarce. Furthermore, there is limited information on seed priming enhancing seed germination and early growth of seedlings under combined stresses. The objective of this research was to evaluate the effect of seed priming on tolerance enhancement of KBG to salinity, waterlogging, and the combined saline-waterlogging stresses.

-

Two KBG cultivars, Moonlight and Award, were included in this experiment. 'Award' was tolerant to salinity, waterlogging, and saline-waterlogging at the germination and seedling growth stage, while 'Moonlight' was sensitive to these stresses[1]. The seeds were either non-primed (NP) or primed with seven priming agents that had shown enhanced stress tolerance in various crops except the Na2SO4 + MgSO4 mixture (SS) (Table 1). Sargeant et al.[17] reported that NaCl priming improved the survival rate and growth of Distichlis spicata (L.) when exposed to NaCl-induced salinity at low to moderate conditions. As salinity and saline-waterlogging conditions were induced by a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 mixture in the present study, SS was included as a priming treatment. Briefly, the seeds were aerated in the priming solution for 24 h at room temperature. The ratio of seed weight to volume of the priming solution was 1:5 for maximum seed absorption. The seeds were rinsed three times with distilled and deionized water (DD) after priming and air-dried to the original weight in a laminar flow hood for approximately 12 h in the dark. The primed seeds were sown at 245 kg pure live seed (PLS) ha−1 in the 10 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm plastic pots filled with a mixture of topsoil (nonsterilized, clay loam, frigid Aeric Calciaquolls), (S & S Landscaping, Fargo, ND, USA), and sand (air-dried, < 2 mm washed mason sand), (Knife River, Fargo, ND, USA) at the ratio of 1:2 (v:v). The pH of the soil mixture was 7.1. It contained 7 mg·kg−1 P and 110 mg·kg−1 K. The seeding rate in this experiment was higher than the recommended seeding rate for regular field establishment (147 kg PLS ha−1) to ensure sufficient plant mass for sampling, especially under a stressful environment. The pots were wrapped with a plastic liner to avoid potential leaching when watering the plants. A fertilizer of 18N-24P2O5-5K2O (The Anderson Lawn Fertilizer Division, Inc., Maumee, OH, USA) was applied at 49 kg N·ha−1 at seeding time. Germinating seeds and seedlings were exposed to salinity (Expt 1), waterlogging (Expt 2), and combined saline-waterlogging conditions (Expt 3) for six weeks. A non-stressed control was included in each experiment.

Table 1. Priming solutions showed enhanced stress tolerance in previous research.

Priming solution Stress Ref, Deionized, distilled water (DD) Saline, drought, low temperature [12,14] KNO3 (500 ppm) Saline, drought [12] Polyethylene glycol-6000 (PEG, 20%) Drought [15] Glycinebetaine (GB, 100 mM) Saline, drought [8] Abscisic acid (ABA, 50 ppm) Drought [16] Gibberellic acid (GA, 100 ppm) Drought [16] Na2SO4 + MgSO4 (SS, 1:1, w:w,

3 dS·m−1)The soil-sand mixture in the experimental pots was irrigated with tap water (control and waterlogging) or a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 mixture (1:1, w:w, 6 dS·m–1) (saline and saline-waterlogging) at a field capacity volume (210 mL) before seeding. The field capacity volume was determined following the method of Yang & Zhang[18]. An additional 50 mL of tap water and salt solution was added to the waterlogged and saline-waterlogged pots, respectively, to stimulate waterlogged conditions (i.e., solution level was ~0.5 cm above the soil surface). The control (Expts 1–3) and salinity pots (Expt 1) were weighed three times per week (M., W., and F), and tap water or salt solution was added to the pots to maintain field capacity. Tap water or salt solution was added to the waterlogged (Expt 2) or saline-waterlogged pots (Expt 3) daily to maintain the same water level (~0.5 cm above the soil surface), for waterlogged conditions. The pots were kept in the greenhouse at 25/15 °C (day/night) with a 16 h photo-period for six weeks.

Plants were harvested when the experiment was terminated on Day 42. Soil mixtures were carefully hand-washed off the roots and the longest root length (RL) was measured. Shoots and roots were then separated and shoot and root dry weights (SDW and RDW) were recorded after being oven dried at 65 °C for 48 h. Specific root length (SRL), the ratio of RL to RDW, is positively correlated with stress severity[1]. The design of each experiment was a 2 (cultivar) × 8 (priming treatment) × 2 (growing condition) factorial combination, arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Data was subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the PROC MIXED procedure (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and means were separated with Fisher's protected least significant difference at p ≤ 0.05. Soil salinity (electrical conductivity from saturated soil paste, ECe), and pH analysis were analyzed from randomly selected pots from each experiment (Table 2).

Table 2. Soil salinity (electrical conductivity from saturated soil paste, ECe) and pH of each experiment.

Expt 1 – salinity Expt 2 – waterlogging Expt 3 – saline-waterlogging Control Salinityz Control Waterloggingz Control Saline-waterloggingz Soil ECe (dS·m−1) 1.38 2.31 1.34 1.27 1.35 2.47 Soil pH 8.02 8.13 8.20 8.04 8.13 8.05 zSalinity stress was induced by salt irritation (a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 mixture, 1:1, w:w) at 6 dS·m−1; waterlogging was induced by keeping excessive tap water (~0.5 cm above soil surface) in experimental pots; saline-waterlogging was induced by keeping excessive salt solution (a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 mixture, 1:1, w:w, 6 dS·m−1) (~0.5 cm above soil surface) in experimental pots. -

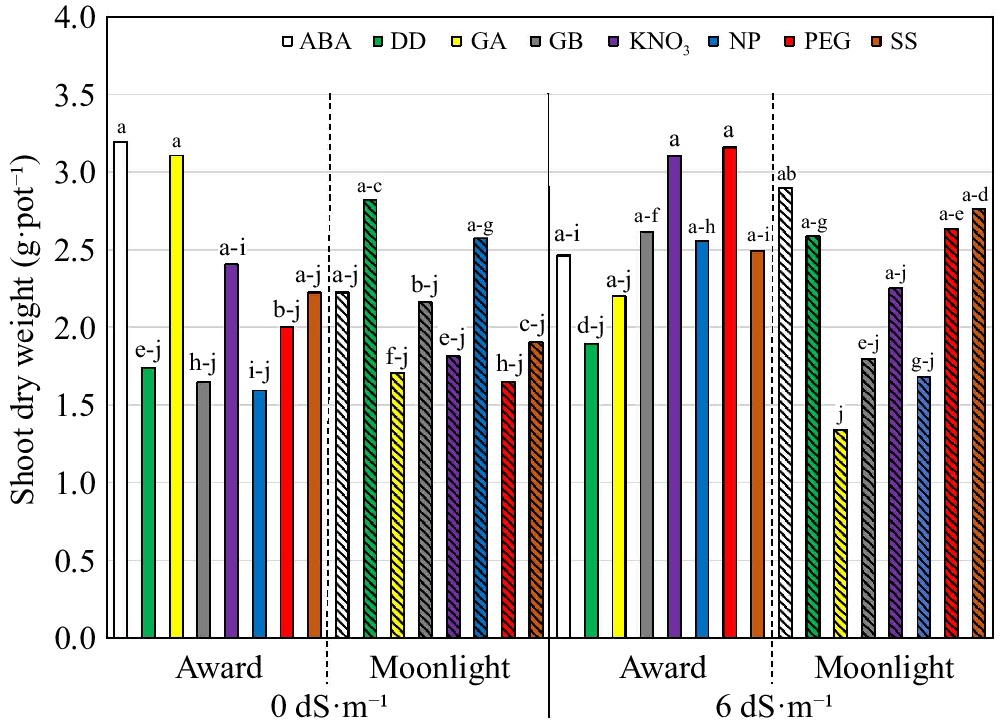

The SDW was influenced by the three-way interaction, salinity × cultivar × priming (Table 3). ABA- and GA-primed 'Award' outperformed the non-primed 'Award' at 0 dS·m−1, but no primers were better than the untreated 'Award' at 6 dS·m−1 (Fig. 1). A reversed trend was observed in 'Moonlight' that ABA-, PEG-, and SS-primed 'Moonlight' were better than the untreated 'Moonlight' at 6 dS·m−1, and no differences were detected among the priming treatments in 'Moonlight' under the non-saline conditions. Overall, ABA, KNO3, and SS treatments were among the top performers across cultivars and salinity (Fig. 1).

Table 3. Growth response of Kentucky bluegrass seedlings as affected by salinity [induced by a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 mixture (1:1, w:w)], cultivar, and priming solutions.

Treatment Shoot dry weight

(g·pot−1)Root dry weight

(g·pot−1)Root to shoot ratio (%) Root length (cm) Specific root length

(cm·g−1)Salinity (S, dS·m−1) 0 2.20ay 0.86a 37.3a 20.6a 42.1a 6 2.40a 0.84a 33.6a 18.6b 39.6a p-value nsx ns ns * ns Cultivar (C) Award 2.43a 0.92a 36.4a 20.1a 40.5a Moonlight 2.18b 0.78a 34.5a 19.2a 41.1a p-value * ns ns ns ns Primingz (P) ABA 2.80a 1.00a 36.7a-c 19.2a 23.9a GB 2.05a 0.69bc 33.1bd 19.8a 37.0a NP 2.10a 0.97ab 43.0a 20.8a 30.4a DD 2.26a 0.90ab 37.4a-c 20.1a 40.4a GA 2.09a 0.59c 26.2d 17.6a 74.6a KNO3 2.39a 0.74a-c 28.6cd 19.9a 53.8a PEG 2.36a 0.91ab 37.9ab 21.0a 29.1a SS 2.35a 0.99a 40.6ab 18.6a 37.5a p-value ns * * ns ns C × P * * ns ns ns C × S ns ns ns ns ns P × S * ns ns ns ns C × P × S * ns ns ns ns zThe priming treatments are: abscisic acid at 50 ppm (ABA), glycinebetaine at 100 mM (GB), no priming (NP), deionized and distilled water (DD), gibberellic acid at 100 ppm (GA), KNO3 at 500 ppm (KNO3), polyethylene glycol-6,000 at 20% (PEG), and a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 (1:1, w:w) at 3 dS·m−1 (SS). yMeans in a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05). xns and * mean no significant differences and significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, respectively.

Figure 1.

Shoot dry weight (g·pot−1) of 'Award' and 'Moonlight' (hashed) Kentucky bluegrass seedlings as affected by the cultivar × growing condition × priming interaction. The priming treatments are: abscisic acid at 50 ppm (ABA), glycinebetaine at 100 mM (GB), no priming (NP), deionized and distilled water (DD), gibberellic acid at 100 ppm (GA), KNO3 at 500 ppm (KNO3), polyethylene glycol-6,000 at 20% (PEG), and a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 (1:1, w:w) at 3 dS·m−1 (SS). Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05).

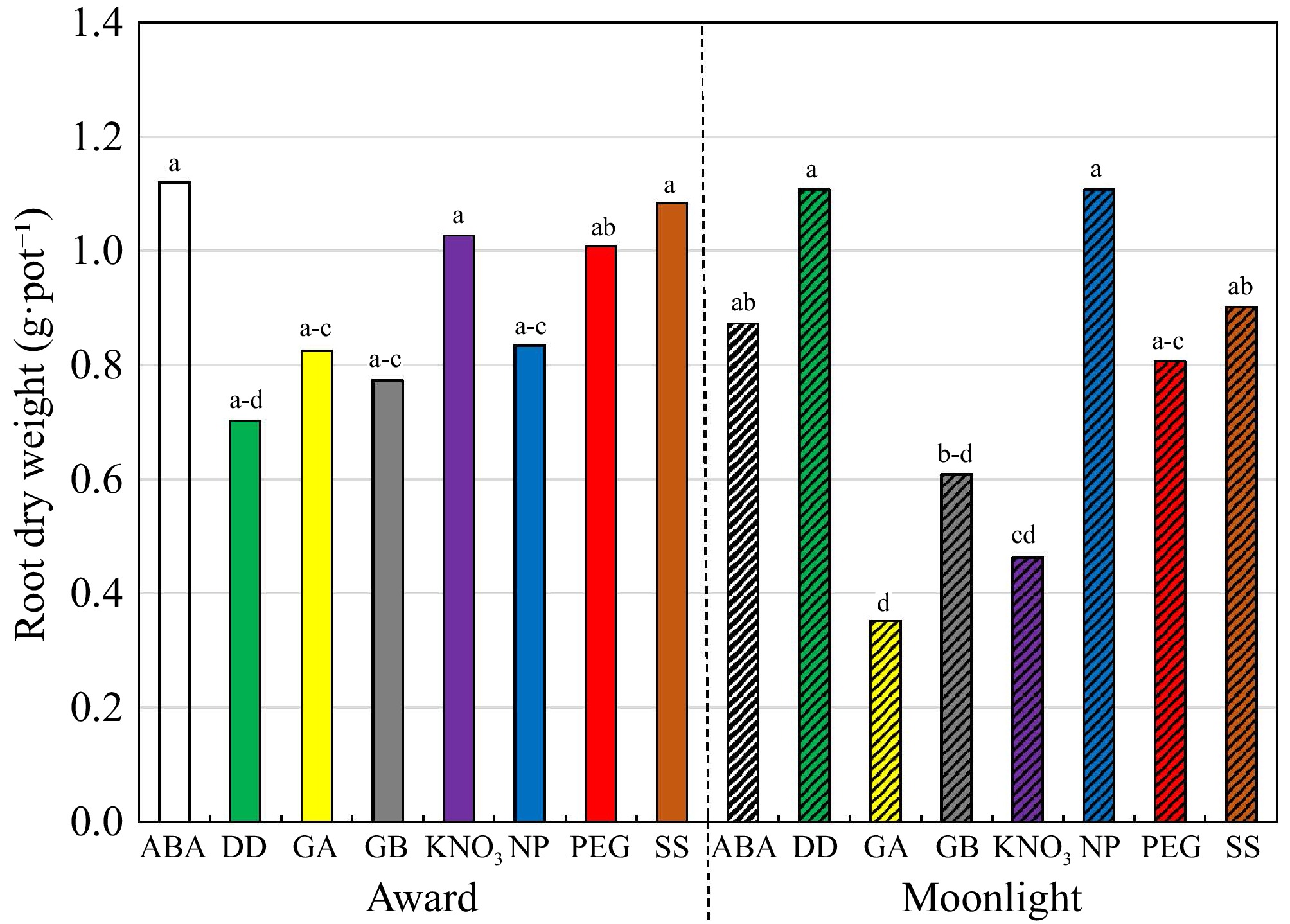

A two-way interaction, cultivar × priming, was observed in RDW (Table 3). No priming differences were observed in 'Award' (Fig. 2). In 'Moonlight', however, RDW of the NP and DD treatments were higher than those under the GA, GB, and KNO3 treatments. Cultivar differences were only observed in GA and KNO3 treatments in which 'Award' had a higher RDW than 'Moonlight'. Salinity did not affect RDW, averaging 0.85 g·pot−1.

Figure 2.

Root dry weight (g·pot−1) of Kentucky bluegrass seedlings as affected by the cultivar × priming interaction when data were pooled across salinity. The priming treatments are: abscisic acid at 50 ppm (ABA), glycinebetaine at 100 mM (GB), no priming (NP), deionized and distilled water (DD), gibberellic acid at 100 ppm (GA), KNO3 at 500 ppm (KNO3), polyethylene glycol-6,000 at 20% (PEG), and a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 (1:1, w:w) at 3 dS·m−1 (SS). Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05).

The RDW/SDW ratio showed no differences between cultivars or saline conditions (Table 3). Non-primed plants had an RDW/SDW ratio of 43%, higher than those treated with GB, GA, and KNO3 (average = 29.3%). Salinity reduced RL from 20.6 cm to 18.6 cm (Table 3). Cultivar and priming did not show an influence on RL (Table 3). SRL was not affected by either of the three main factors or their interactions (Table 3).

Expt 2 – Effects of seed priming on the early growth of KBG under waterlogging

-

The RL and SRL were not affected by the main factors nor their interactions, except that waterlogging increased SRL (Table 4). The SDW was significantly affected by waterlogging and cultivar (Table 4). Under waterlogging, the SDW was decreased by 10.4% compared to non-waterlogging condition (Table 4). The cultivar 'Award' had a higher level of SDW than that of cultivar 'Moonlight' when data were pooled across waterlogging and all priming treatments.

Table 4. Growth response of Kentucky bluegrass seedlings as affected by waterlogging, cultivar, and priming solutions.

Treatment Shoot dry weight

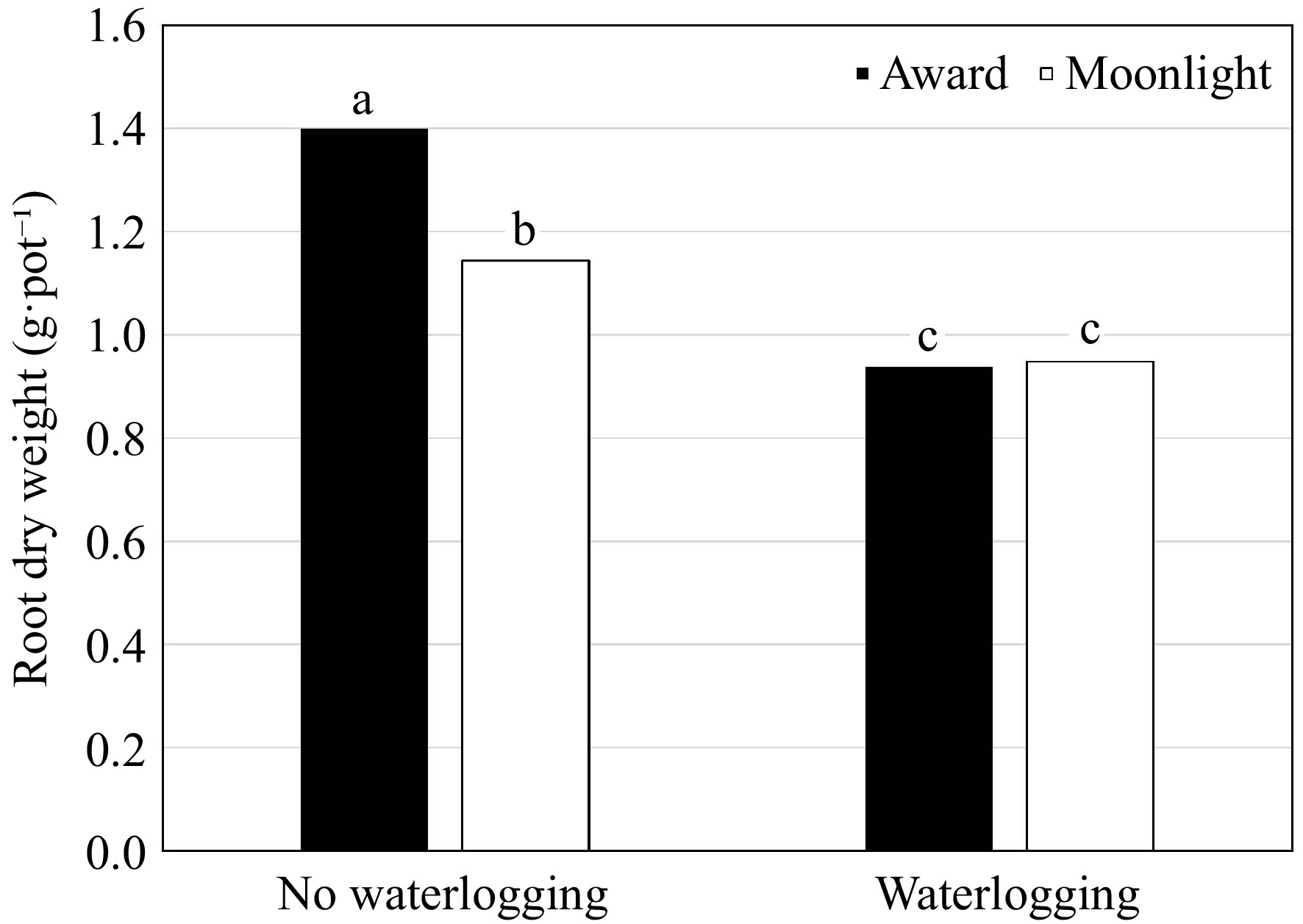

(g·pot−1)Root dry weight

(g·pot−1)Root to shoot ratio (%) Root length (cm) Specific root length (cm·g−1) Waterlogging (W) Non-waterlogged 2.41ay 1.28a 52.8a 22.0a 19.8b Waterlogged 2.16b 0.94b 46.2b 20.9a 26.2a p-value * * * nsx * Cultivar (C) Award 2.53a 1.17a 46.8b 21.4a 21.9a Moonlight 2.04b 1.05b 52.1a 21.5a 24.1a p-value * * * ns ns Primingz (P) ABA 2.33a 1.28a 54.8a 22.8a 22.4a GB 2.27a 1.12a 50.9a 22.3a 24.9a DD 2.57a 1.09a 44.6a 22.8a 24.3a GA 2.27a 1.08a 49.2a 21.6a 24.4a KNO3 2.46a 1.15a 49.0a 22.6a 20.9a NP 1.86a 0.90a 48.8a 19.8a 23.7a PEG 2.31a 1.15a 49.6a 20.5a 22.0a SS 2.21a 1.08a 49.0a 19.4a 21.5a p-value ns ns ns ns ns C × P ns ns ns ns ns C × W ns * * ns ns P × W ns ns ns ns ns C × P × W ns ns ns ns ns zThe priming treatments are: abscisic acid at 50 ppm (ABA), glycinebetaine at 100 mM (GB), no priming (NP), deionized and distilled water (DD), gibberellic acid at 100 ppm (GA), KNO3 at 500 ppm (KNO3), polyethylene glycol-6,000 at 20% (PEG), and a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 (1:1, w:w) at 3 dS·m−1 (SS). yMeans in a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05). xns and * mean no significant differences and significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, respectively. An interaction of waterlogging × cultivar was detected in RDW and RDW/SDW (Table 4). Waterlogging inhibited RDW in both cultivars with a reduction of 49.2% and 20.8% for 'Award' and 'Moonlight', respectively (Fig. 3). Although the RDW of 'Award' was higher than that of 'Moonlight' under non-waterlogging conditions, the differences in RDW between the two cultivars diminished under waterlogging stress. A reversed trend was observed in the RDW/SDW ratio (Fig. 4). No differences were observed in the priming treatments in RDW and RDW/SDW (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Root dry weight (g·pot−1) of Kentucky bluegrass seedlings as affected by the cultivar × waterlogging interaction when data were pooled across priming treatments. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05).

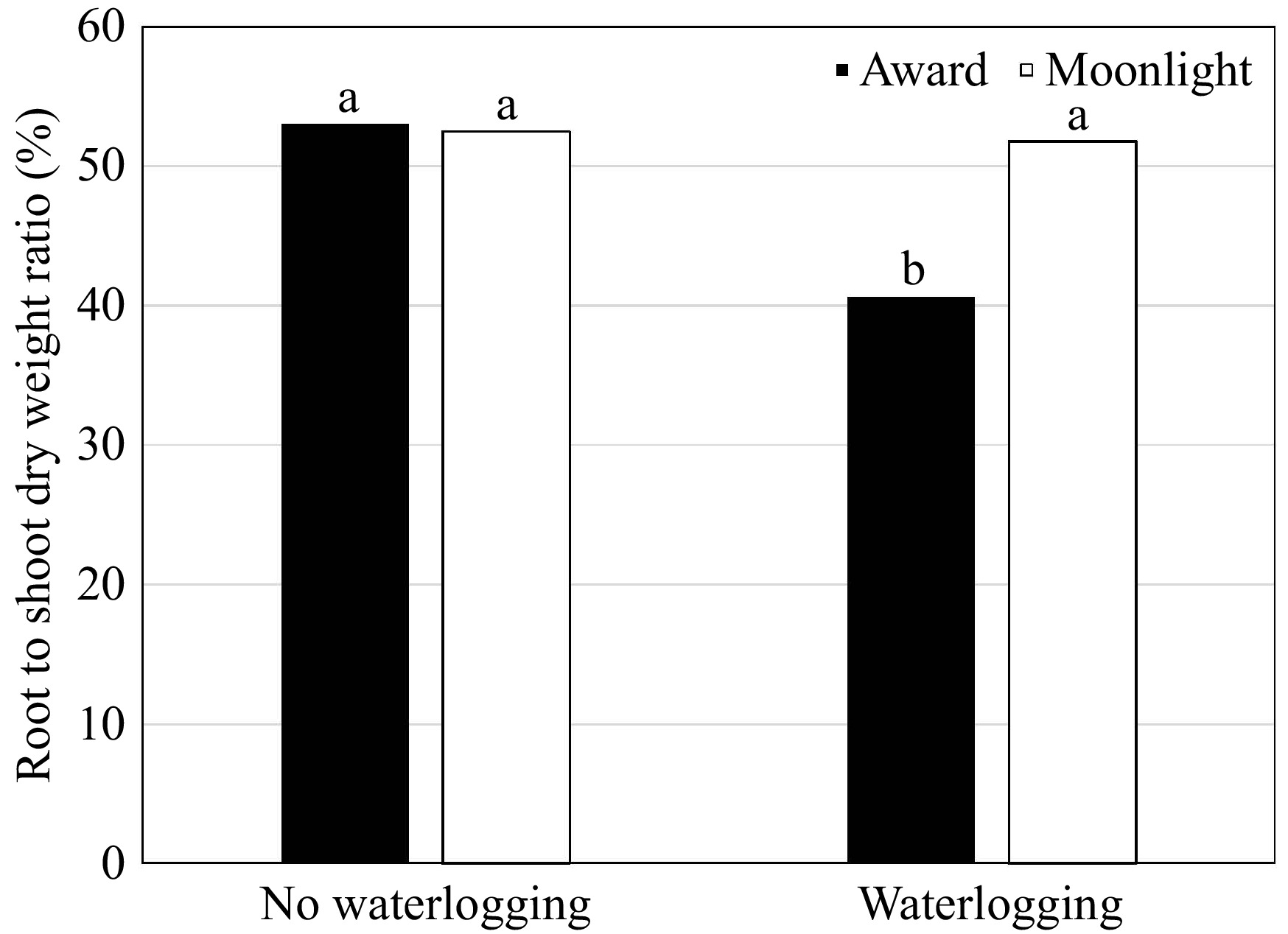

Figure 4.

Root to shoot dry weight ratio (%) of Kentucky bluegrass seedlings as affected by the cultivar × waterlogging interaction when data were pooled across priming treatments. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05).

Expt 3 – Effects of seed priming on the early growth of KBG under the combined saline-waterlogging stress

-

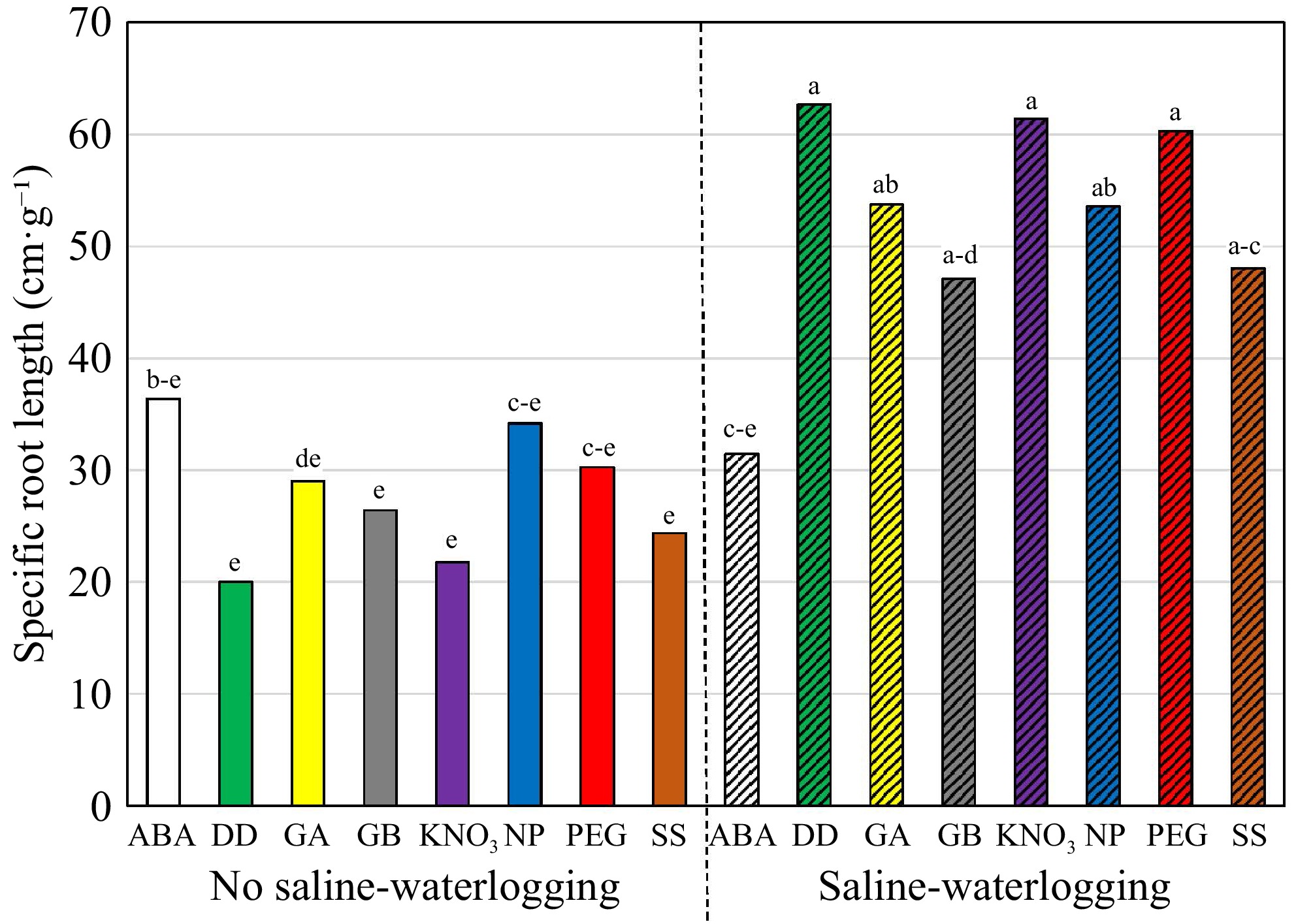

The combined stress conditions of saline-waterlogging reduced SDW, RDW, and RDW/SDW, and increased SRL; however, the combined stress had no significant impact on RL (Table 5). A comparison of the two cultivars showed that 'Award' outperformed 'Moonlight' in SDW and RDW, whereas 'Moonlight' had a higher RDW/SDW ratio. No differences in RL and SRL were observed between the two cultivars. The SDW of KNO3- or SS-primed plants was higher than those primed with DD, GA, and PEG. The RDW/SDW ratio was lower in non-primed or primed with ABA, KNO3, and SS treatments than in other priming treatments. An interaction of priming × saline-waterlogging was observed in SRL (Table 5). Plants exposed to the saline-waterlogging conditions showed a higher level of SRL than that of non-stressed plants except those primed with ABA (Fig. 5). No differences in priming treatments were seen under the non-stress conditions, however, seedlings of KBG from the seeds primed with ABA had a lower level of SRL than other priming treatments under the combined stresses of salinity and waterlogging.

Table 5. Growth response of Kentucky bluegrass seedlings as affected by saline-waterlogging [induced by waterlog plants using a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 mixture (1:1, w:w, 6 dS·m−1)], cultivar, and priming solutions.

Treatment Shoot dry weight

(g·pot−1)Root dry weight

(g·pot−1)Root to shoot ratio (%) Root length (cm) Specific root length (cm·g−1) Saline-waterlogging (SW) Non-saline-waterlogged 1.86ay 0.81a 47.0a 19.8a 27.8b Saline-waterlogged 1.32b 0.43b 36.5b 18.8a 52.3a p-value * * * nsx * Cultivar (C) Award 1.87a 0.66a 38.0b 19.6a 37.1a Moonlight 1.31b 0.58b 45.5a 19.0a 43.0a p-value * * * ns ns Primingz (P) ABA 1.64ab 0.58a 37.5b 18.0a 33.9a GB 1.61a−c 0.70a 44.8a 19.2a 36.8a NP 1.76ab 0.61a 37.2b 19.4a 43.9a DD 1.41bc 0.68a 49.6a 20.4a 41.3a GA 1.17c 0.56a 47.5a 17.9a 41.4a KNO3 1.88a 0.59a 34.6b 18.5a 41.6a PEG 1.31bc 0.60a 47.7a 22.1a 45.3a SS 1.94a 0.63a 35.1b 18.9a 36.2a p-value * ns * ns ns C × P ns ns ns ns ns C × SW ns ns ns ns ns P × SW ns ns ns ns * C × P × SW ns ns ns ns ns zThe priming treatments are: abscisic acid at 50 ppm (ABA), glycinebetaine at 100 mM (GB), no priming (NP), deionized and distilled water (DD), gibberellic acid at 100 ppm (GA), KNO3 at 500 ppm (KNO3), polyethylene glycol-6,000 at 20% (PEG), and a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 (1:1, w:w) at 3 dS·m−1 (SS). yMeans in a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05). xns and * mean no significant differences and significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, respectively.

Figure 5.

Specific root length (cm·g−1) of Kentucky bluegrass seedling as affected by the growing condition × priming interaction when data were pooled across cultivars. The priming treatments are: abscisic acid at 50 ppm (ABA), glycinebetaine at 100 mM (GB), no priming (NP), deionized and distilled water (DD), gibberellic acid at 100 ppm (GA), KNO3 at 500 ppm (KNO3), polyethylene glycol-6,000 at 20% (PEG), and a Na2SO4 + MgSO4 (1:1, w:w) at 3 dS·m−1 (SS). Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher's protected least significant difference test (p ≤ 0.05).

-

A ray of research showed improved plant growth and stress tolerance in turfgrass species through seed priming. Most of the research focused on identifying optimal concentration(s) for individual priming agents. Jia et al.[19] compared the efficacy of five priming agents [ABA, GA, GB, PEG, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)] in the enhancement of low-temperature tolerance of creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.). The results showed that GB and PEG (osmotic primers) were the most effective, followed by ABA and GA (hormone primers), while H2O2 (redox primer) was the least effective in improving cold tolerance, indicating that primers vary in their ability in stress enhancement. Among the seven primers evaluated in the current research, ABA was often one of the top performers and better than the NP control (Figs 1, 2 & 5; Tables 3 & 5). Abscisic acid, a so-called stress hormone, plays a special role in stress tolerance, especially water deficiency-related stresses like salinity, drought, and sub-optimal temperatures[20]. ABA-priming improves stress tolerance through ion regulation, enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities, activation of stress tolerance-related genes, interaction with other hormones, and osmolyte regulation. Seed priming can be separated into different categories depending on the techniques applied, such as hormonal priming (induced by plant hormones like ABA and GA), osmotic priming (osmotic solutions like GB and PEG), halo-priming (inorganic salts like KNO3 and SS), and hydro-priming (water), which often induce similar responses in plants. However, the spectrum and intensity of the responses are likely regulated by plant (species/cultivar), primer, stress (type, severity, and duration), and their interactions. For example, Wang & Shi[21] evaluated the effects of hormonal priming [melatonin (MT), ABA, and brassinosteroid (BR)], osmotic priming (CaCl2), and hydropriming on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) germination under saline-alkali stress. Seeds primed with ABA, MT, and BR showed higher germination, α- and β-amylase activity (regulating starch hydrolysis), and lower malondialdehyde (an indicator of membrane stability), than CaCl2 and hydropriming. Iqbal et al.[22] reported higher shoot and root biomass, higher free salicylic acid, and lower ABA in CaCl2 primed salt-sensitive wheat cultivar (MH-97) compared to KCl and NaCl priming. In the salt-tolerant variety (Inqlab91) though, no differences in growth and physiological responses were detected among the priming treatments.

It has been reported that GB improved turfgrass tolerance to salinity[8] and low temperature[19] through seed priming, indicating the possibility that one primer can improve plant tolerance to multiple stressors. Among the seven primers in the current research, ABA increased SDW in 'Moonlight' under salinity (Fig. 1), and lowered SRL under the combined saline-waterlogging stress (Fig. 5), which was similar to the results from other research related to water deficiency caused by drought and salinity[16,20,23]. In this study, ABA showed no positive results under waterlogging conditions (Table 4). It might be due to the differences in the nature of the stresses, physiological drought and ion toxicity, and imbalance under salinity and O2 deficiency under waterlogging. Salinity often leads to ABA accumulation in plants, while a significant reduction of ABA has been reported in various crops subjected to waterlogging[24]. Similar to our findings, El-Sanatawy et al.[25] reported that NaCl-priming (4,000 ppm) improved maize yield at 60% and 80% evapotranspiration rate (ET) (i.e. water deficiency), but not 120% ET (i.e. waterlogging). Watanabe et al.[26] reported improved rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedling growth when ethephon (an inducer of ethylene) and GA were applied to pre-soaked seeds (i.e., seeds soaked in water for 48 h before the ET and GA treatments). No waterlogging enhancement was observed in the GA-priming in the present study. The differences between the present study and Watanabe et al.[26] may be caused by the variations in plant materials used, timing/method of the hormone application (priming in the current study vs seed germination), and application rate. Further experiments are needed to evaluate the effects of identifying priming agents (including ethylene) and their optimal concentrations for waterlogging enhancement in turfgrass.

Zhang & Rue[8] reported a higher final germination rate and faster germination in GB-primed turfgrass than the non-primed ones under osmotic and salinity stress. However, this study indicated that GB-primed KBG performed similarly to the non-primed control under salinity and the combined saline-waterlogging stress (Tables 3 & 5). It may be related to the differences in the growing media between the two studies. For instance, seeds were germinated on germination paper in petri dishes in the study by Zhang & Rue[8], but in this study the seeds were sown in a soil and sand mixture. Khan et al.[27] and Hossain et al.[28] reported interactive effects of seed priming and growing media on the growth of papaya (Carica papaya L.). Similar results were also seen in bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.)[29]. This may partially explain why the positive result from seed priming under the laboratory setting vanished under field conditions. The different observations between Zhang & Rue[8] and the present study also suggest that the effects of seed treatments might be growth-stage-specific and organ-specific. Early/initial growth (i.e., germination and early seedling growth quantified 28 d after germination in Zhang & Rue[8]) showed higher responsiveness to seed priming than early vegetative growth (i.e., shoot and root tissue sampled 42 d after seeding). Similar to our findings, Watanabe et al.[26] reported that hormonal seed treatment promoted higher growth on the early developing organs (mesocotyle, coleoptile, and first leaf) than the later developing organs (second and third leaf). Brede[30] suggested that the effect of priming on turfgrass may diminish after 6 weeks of growth under optimal conditions. Despite that the positive influences of seed priming may be short-lived, fast and uniform germination and high-stress tolerance put primed seeds at an advantage during the germination and seedling growth stages when plants can be dramatically influenced by adverse conditions. It is especially important for turfgrass establishment due to their small seed size compared to other field crops.

Despite the complexity of seed priming, limited interactions among plants, growing conditions, and priming agents were observed in the current study (Tables 3–5). We hypothesize that the effects of growing conditions masked potential interactions, especially under the waterlogging (27% reduction in root growth) and saline-waterlogging conditions (47% reduction in root growth). Therefore, in addition to continuing the research on seed priming, it is important to persistently breed stress tolerant plants and using cultural practices minimizing stress severity to improve plant performance.

-

Plants from ABA-primed seeds performed better than that of the non-primed control under salinity and saline-waterlogging conditions, suggesting its potential to improve KBG growth and stress tolerance during the early growth period. The cultivar 'Award' outperformed 'Moonlight' under all three stress environments (salinity, waterlogging, and saline-waterlogging). This study indicates that seed priming is a good and applicable management practice when establishing a turfgrass stand, particularly in saline soil.

We thank the United States Golf Association and ND Hatch Project (ND01509) for funding this project.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the study paper as follows: study conception and experimental design: Rue K, Zhang Q; data collection, Rue K; statistical analysis, manuscript preparation: Rue K, Zhang Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Rue K, Zhang Q. 2025. Impact of seed priming on early growth of Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) under saline, waterlogging, and combined saline-waterlogging stresses. Grass Research 5: e018 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0015

Impact of seed priming on early growth of Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) under saline, waterlogging, and combined saline-waterlogging stresses

- Received: 10 January 2025

- Revised: 13 May 2025

- Accepted: 21 May 2025

- Published online: 02 July 2025

Abstract: Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) (KBG), a popular turfgrass species used in golf fairways, is known to be sensitive to salinity and waterlogging. This research was to determine if seed priming can enhance the stress tolerance of two KBG varieties 'Award' (stress tolerant) and 'Moonlight' (stress susceptible). The seeds were either non-primed (NP) or primed with water, 50 ppm abscisic acid (ABA), 100 mM glycinebetaine (GB), 100 ppm gibberellic acid (GA), 20% polyethylene glycol (PEG), 500 ppm KNO3, or a salt mixture of Na2SO4 and MgSO4 (1:1, w:w) at 3 dS·m−1 before being sown in a topsoil : sand mixture. The seedlings were grown under the stress of salinity, waterlogging, saline-waterlogging, or non-stressed control for six weeks in a greenhouse. Results showed that the growth of 'Award' was 10% to 30% higher than that of 'Moonlight' under all three stress conditions. ABA priming alleviated the stress caused by salinity and saline-waterlogging. However, seed priming showed no significant growth improvement under waterlogging. This study indicates that seed priming is a good and applicable management practice when establishing a turfgrass stand, particularly in saline soil.

-

Key words:

- Turfgrass /

- Abscisic acid /

- Glycinebetaine /

- Polyethylene glycol /

- KNO3