-

Woody ornamental plants, including landscape trees and shrubs, play a crucial role in enhancing the aesthetic value of residential, recreational, public, and commercial environments in both urban and suburban settings. Additionally, they provide key ecological and environmental benefits, such as improving air and water quality, sequestering carbon, offering habitats for wildlife, reducing runoff and erosion, and supporting stormwater management. Therefore, long-term breeding programs are essential for producing well-adapted woody ornamental plants that meet the needs of a livable environment. Traditional methods like hybridizing and selection, ploidy manipulation, and mutation breeding have been successfully used in woody ornamental plants. Recently, genetic modification techniques such as transgenic and gene editing approaches have shown tremendous potential for improving ornamental traits. These bioengineering technologies can introduce unique genetic variations - especially those not present in the current gene pools - more quickly.

However, the application of genetic engineering, especially gene editing in woody ornamentals, lags behind its use in major agricultural crops, mainly due to the difficulty of plant transformation via tissue culture-based regeneration. As in many other plant species, Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated genetic transformation has been the primary method of choice for producing transgenic and gene-edited woody ornamental plants[1]. However, many woody plants are recalcitrant to this transformation method even with extensive optimization efforts, which is a bottleneck for applying modern bioengineering technologies in these plant species. New studies using various developmental genes to overcome this difficulty are promising[2], but alternative strategies are still needed. Moreover, since many woody ornamental cultivars are clonally propagated heterozygous plants, eliminating transgenes through sexual segregation for gene editing components is not possible. To fully leverage the deregulation aspect of gene editing, producing transgene-free gene-edited plants is a top priority for applying new breeding technology in woody plants. Various methods have been employed to produce transgene-free gene-edited plants[3]. These methods include the delivery of RNP and mRNA into protoplast or via particle bombardment, transient expression of gene editing components without antibiotic selection or using a viral vector, and co-editing with counter-selection markers to eliminate transgene. Another approach is the Transgene Killer CRISP (TKC) technology, which uses suicide genes such as Cytoplasmic Male Sterility 2 (CMS2) and BARNASE to eliminate transgene-containing gametes. Additionally, Hi-Edit technology enables the production of transgene-free edited plants through haploid induction. However, these approaches are not easily applicable to woody plants due to the lack of robust plant regeneration capacity and rapid sexual repropagation, which are typically absent in most woody plants. Recently, Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation has demonstrated potential for woody plant bioengineering[4,5]. Building on recent developments in mobile gene editing elements[5], we discuss the potential of combining these developments to create an innovative tool for applying new breeding technologies in woody plants.

-

A. rhizogenes, also known as Rhizobium rhizogenes[6], is a Gram-negative bacterium. It is related to A. tumefaciens, which contains a tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid with a DNA segment known as T-DNA that can be transferred to the host plant genome, inducing a pathogenic response in natural infection and producing transgenic plants if oncogenes are replaced with genes of interest. A. rhizogenes contain a root-inducing (Ri) plasmid that facilitates the induction of hairy roots in infected plants. Manipulation of A. rhizogenes by disarming the Ri plasmid has been accomplished[7]; however, in most reports, wild-type strains were used with a regular binary vector[8]. The hairy root induction capacity of the bacterium leads to the generation of large numbers of roots, which can contain transgenes if the T-DNA from the engineered binary vector is integrated into the induced root tissue. This opens a variety of applications for A. rhizogenes-mediated transformation in plant research, particularly in areas such as secondary metabolites synthesis, metabolic engineering, gene functionality studies, root development, root and soil microbe interaction, and plant allelopathy[5].

Since shoot explants can be used for this root induction, A. rhizogenes enable the production of tissue culture-independent composite plants with transgenic roots. This is especially beneficial for woody plants, as recalcitrant tissue often hinders the use of traditional A. tumefaciens-mediated genetic transformation. It has long been recognized that new plants can be produced from transgenic roots through either tissue culture-dependent regeneration or by utilizing the plant's natural ability to produce new shoots via runners and suckers. Liu et al.[9] presented an excellent example for the first scenario by developing an efficient A. rhizogenes-mediated transformation system for fruit trees by converting transgenic hairy roots into shoots. Likewise, Cao et al.[10] developed a simple cut-dip-budding method to produce tissue culture-independent transgenic plants by inducing shoots from transformed hairy roots in multiple plant species including woody plants.

Despite the potential benefits, the technical challenges of genetic transformation in woody plants hinder the widespread application of these new breeding technologies. With the rapid development of genome editing technology, generating genetically modified plants using A. rhizogenes has garnered increased research attention. The use of A. rhizogenes in plants, including woody plants, for genetic transformation has been well-documented[5,6], as well as its use in plant genome editing (Table 1). However, in many cases, gene editing has been demonstrated in hairy root tissue only for functional studies. The generation of transgenic or gene-edited plants still relies on either tissue culture-mediated regeneration or plant species capable of producing suckers and runners.

Table 1. Examples of A. rhizogenes-mediated gene editing in plants.

Plant A. rhizogenes strain Editing target Regeneration method Ref. Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa) K599 BrPDS Developmental gene/no hormone [18] Chicory (Cichorium intybus) 15834 CiPDS Spontaneously shoot from hairy root [19] Citrus (Citrus medica) K599 CmACD2 Transgenic hairy root [20] Citrus (Citrus sinensis) K599 CsPP2-1 Transgenic hairy root [21] Citrus spp. Not specified CsNPR3 Hormone induced (various

combinations of auxin and cytokinin)[22] Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) K599 GhPDS Transgenic hairy root [23] Kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis, Actinidia eriantha) K599 AcCEN4, AeCBL3 Hormone-induced (Zeatin and NAA) [24] Medicago truncatula ARqua1 NCR068 Hormone-induced (2,4-D and BAP) [25] Populus (Populus tremula × alba) ARqua1 PtaSHR, PtaYUC4/PtaPLT1, PtaLBD4/PtaLBD12 Transgenic hairy root [26] potato DMF1 (Solanum tuberosum × chacoense) MSU440 StPDS Hormone-induced

(Zeatin, IAA and GA3)[27] Pyrethrum MSU440 TcEbFS Transgenic hairy root [28] Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) MSU440 RsPDS Developmental gene/no hormone [29] Russian dandelion (Taraxacum kok-saghyz) K599 TKSPDS Budding from hairy root [10] Salvia miltiorrhiza ACCC10060 SmCPS1 Transgenic hairy root [30] Soybean (Glycine max) K599 GmNSP1a, GmNSP1b Transgenic hairy root [31] Soybean (Glycine max) K599 SACPD-C SMT Transgenic hairy root [32] Soybean (Glycine max) K599 GmUOX1 Transgenic hairy root [33] Soybean (Glycine max) k599 Glyma06g14180 Transgenic hairy root [34] Soybean (Glycine max) K599 GmLHY Transgenic hairy root [35] Soybean (Glycine max) K599 Glyma03g36470, Glyma14g04180, Glyma06g14180 Transgenic hairy root [36] Succulents (Kalanchoe blossfeldiana) K599 KbPDS Direct bud formation [37] Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) K599 IbPDS Budding from hairy root [10] Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) ACCC10060 FtMYB45 Transgenic hairy root [38] Tea (Camellia sinensis) K599, ATCC15834 MYB73 Hormone-induced (BAP and NAA) [39] Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) ATCC15834 SlSCRpro-mGFP5, SlSHR Transgenic hairy root [40] White lupin (Lupinus albus L.) K599 Lalb_Chr05g0223881 Transgenic hairy root [41] Transformation with A. rhizogenes can also cause phenotypic variation in the infected plants by expression of the Ri genes, rolA, rolB, and rolC[8]. This variation can be useful for introducing new variation, but it also alters the genetic and morphological background. In addition, while A. rhizogenes can successfully infect and produce hairy roots in many woody species, generating transgene-free gene-edited plants remains difficult, particularly for heterozygous, polyploid, vegetatively propagated woody species.

-

Endogenous long-distance mobile bioactive molecules have long been identified in plants. These include small molecules such as phytohormones (e.g., auxin, cytokinin, gibberellin, abscisic acid, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid), as well as large molecules such as proteins and RNAs. Examples of proteins include transcription factors that are essential for plant development, such as the well-studied flowering locus T (FT) family of proteins, which move long distances in the phloem[11]. Mobile molecules have been used to modify plants in various grafting-based technologies such as transgrafting. For example, transgene-derived small interfering RNAs (siRNA) can be transferred from rootstock to wild-type scion in sweet cherry (Prunus avium)[12]. In the context of gene editing, plant viruses have been used for delivering gene editing components, leveraging their ability to transport RNA and DNA genomes between cells over long distances. However, the cargo capacity of these viruses often limits their ability to deliver large mobile RNAs, such as those encoding nuclease, such as Cas9[13]. Moreover, gene editing induced by virus-based delivery is often not heritable in the next-generation, due to the exclusion of the virus from shoot apical meristem tissue, limiting its use[13]. These issues could be partially mitigated. For example, Zhang et al. expressed the core gene/genome editing components, Cas9 and small guide RNA (sgRNA), along with an RNAi suppressor in Foxtail mosaic virus, enabling transgene-free gene editing in Nicotiana benthamiana[14]. Yu et al. demonstrated that virus-based delivery of FTRNA fragment-tagged sgRNA could promote sgRNA entry into the meristem for heritable gene editing, although the role of the FTmRNA or FT protein as the mobile florigen remains debatable[13]. Overall, the limitations associated with virus delivery of gene editing components continue to pose a challenge.

The transport of other RNA molecules, such as tRNAs, siRNAs, and miRNAs, has also been extensively studied. These RNAs function as systemic signals and are involved in plant development and biotic and abiotic stress responses. In 2016, Zhang et al. identified tRNA-like structures (TLSs) that can trigger systemic mRNA transport in plants. They demonstrated that these sequences are sufficient to mediate mRNA transport and subsequent expression in distant plant tissues, such as from rootstocks to grafted scions[15]. The same group further demonstrated that these structures could be used to transport gene editing components, including nucleases like Cas9 and gRNA, from transgenic rootstocks to grafted, compatible wild-type plants, producing transgene-free gene-edited progeny without the need for tissue culture[16]. Since the method bypasses the tissue culture stage and avoids the crossing and selfing steps required to produce heritable transgene-free offspring, it is particularly appealing for woody plants with long juvenile periods. However, a significant challenge remains that prevents the widespread application of this technology in woody plants: the need to generate a separate transgenic stock line to produce mobile gene editing molecules.

-

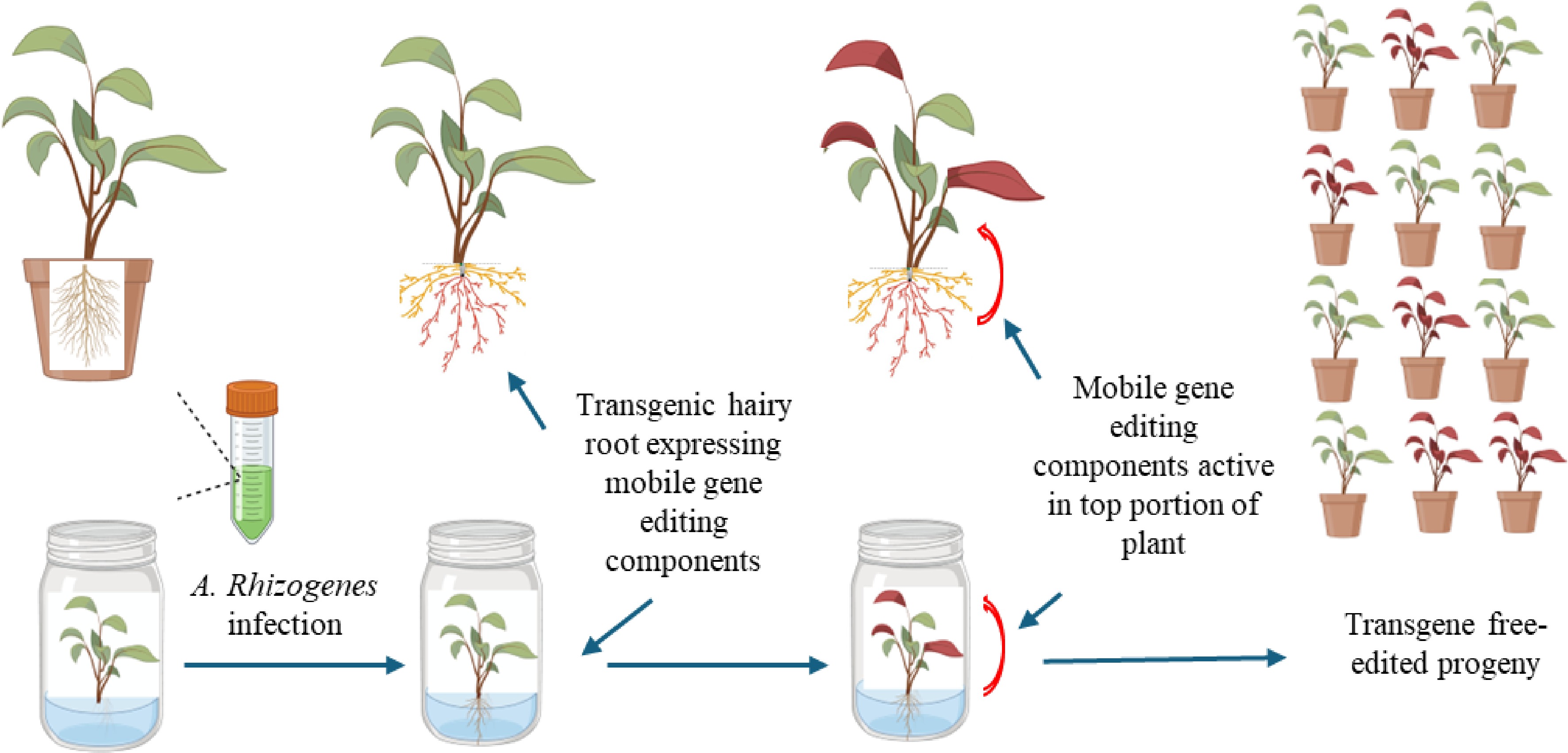

We propose combining the advantages of A. rhizogenes on plant transformation with TLS-mediated mobile molecules for gene editing in woody plants. Specifically, we suggest expressing mobile gene-editing components (such as gene-editing nuclease and guide sequence, e.g., Cas9 and gRNA) in A. rhizogenes-induced transgenic hairy roots. These components are expected to move to the upper portions of the experimental plants, enabling the desired gene editing without the need for grafting. Since no transgenic DNA will move to the upper portions of the plant, the resulting gene-edited shoot will be transgene-free and can be propagated through either sexual or asexual methods, without the need for plant regeneration (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Producing transgene-free gene edited plants by expressing mobile transcripts with A. rhizogenes. Soil-grown or in vitro shoots were infected by A. rhizogenes carrying cassettes to express mobile gene editing components. The expressed mobile components within induced transgenic hairy roots (red) move to the upper portion of the plant, resulting in the desired edits (red). The transgene-free edited plants (red) can be obtained through sexual or asexual methods.

The transgene-free gene-edited plants obtained through this method will retain their genotype, except for the targeted edit, and do not carry Ri effects associated with the transfer of DNA from A. rhizogenes, specifically the root locus genes rolA, rolB, and rolC. Many woody plant species have been shown to be susceptible to A. rhizogene infection and can produce transgenic hairy roots. TLS-tagged transcripts are capable of transporting large transcripts, such as Cas9 nucleases mRNA over long distances, and penetrating meristem and reproductive tissues. Therefore, the proposed method could be readily tested as a tool for the application of new breeding technologies in woody plant species. Some challenges remain for the method. The efficiency of A. rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation will vary among genotypes, and gene transfer may not be achieved in all root tissues. Exploring different A. rhizogenes strains for specific target plant species, as well as incorporating visual and/or selectable markers for transgenic hairy production could mitigate these issues. Moreover, the gene-edited shoots produced through the proposed method may be chimeras rather than homozygotes. This is frequently observed when TLS-mediated mobile signal is used to generate transgene-free genome-edited plants[16], as well as when in planta transformation methods are used[4]. While chimeric plants can be beneficial for ornamental plant breeding, they pose a challenge to our proposed method. This is because obtaining homozygotes through sexual propagation is more difficult in woody plants than in species like Arabidopsis and Brassica rapa, which has been demonstrated previously[16]. To address this, other than increasing editing efficiency as discussed earlier, a subculture-based 'Additional regeneration' technique, which was used to release chimeras in apple plants, could also be applied and optimized to mitigate chimeric plant issues in our proposed method[17].

The work was financially supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) - Agriculture Research Service (ARS) Base funds to the Duan laboratory, and the USDA Non-Assistance Cooperative Agreement with Texas A&M, Research project 2023−2025. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions and Dr. Filiz Gurel for assistance with the figure.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conception and design: Duan H, Wu B, Qin H, Pooler MR; draft manuscript preparation: Duan H. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Duan H, Wu B, Qin H, Pooler MR. 2025. Harnessing Agrobacterium rhizogenes and mobile elements for innovative transgene-free gene editing in woody plants. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e027 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0023

Harnessing Agrobacterium rhizogenes and mobile elements for innovative transgene-free gene editing in woody plants

- Received: 12 March 2025

- Revised: 08 April 2025

- Accepted: 15 April 2025

- Published online: 02 July 2025

Abstract: Woody landscape plants are an important sector of US agriculture and play critical roles in the urban landscape by adding value to residential, public, and commercial properties. Genetic improvement of woody landscape plants is slower than that of most other crops because of long juvenility periods, heterozygosity, and resources required to grow out large populations. New breeding technologies, especially gene editing, hold great promise to complement and improve traditional breeding. This is particularly true in woody ornamental crops where the creation of transgene-free gene-edited plants would accelerate the breeding process and reduce the regulatory burden inherent with transgenic crops. In this prospective review, we propose a method to harness the power of two technologies to transform the process of woody plant gene editing. Agrobacterium rhizogenes can induce transgenic hairy roots in many plant species, while TLS (tRNA-like sequence) has been shown to facilitate the long-distance movement of transcripts from the root to the grafted scion and remain functional. We propose using A. rhizogenes to transform root tissue with mobile gene-editing components. These components would then migrate from the roots into the shoots and leaves of the plant, eliminating the need for grafting. Since only RNA, and not DNA, migrates into the upper portion of the plant, the resulting gene-edited shoot will stay transgene-free and can be propagated through either sexual or asexual methods.

-

Key words:

- Agrobacterium rhizogenes /

- Gene editing /

- Mobile signal