-

The different isomers of methyl-substituted phenols (ortho-, meta-, and para-cresol; see Fig. 1 for structures) were found to be significant products of toluene oxidation, e.g., studies[1−4]. Despite the fact that they are also formed as intermediates during the oxidation of other aromatic fuels[4−11], there has been no previous attempt at detailed kinetic modelling of the oxidation of cresol isomers in the literature. The three isomers appear as a single lumped species in models acting as intermediates in the decomposition process. With the exception of the CRECK model[12], which describes the kinetics of cresols in terms of lumped reactions, other models (e.g., studies[13,14]) rely on the cresol reaction set developed by Bounaceur et al. for the secondary mechanism in the toluene oxidation model[1]. Furthermore, there are no kinetic studies available on the gas-phase reactions of these reactants at combustion temperature. This is certainly due to the fact that, like phenol, cresol isomers have high melting and boiling points (Mp and Bp are 314–455, 304–464, 284–475, and 307–475 K for phenol, ortho-, meta-, and para-cresol, respectively), and several of them are solid at room temperature.

Together with phenol, anisole, benzaldehyde, benzyl alcohol, 2-phenylethanol, and guaiacol, cresol isomers represent the smallest oxygenated aromatic molecules present in biofuels synthesized catalytically from enzymatic hydrolysis of lignin, a by-product of second-generation bioethanol production[15,16]. One of the aims of the European EHLCATHOL project[17] was to investigate the combustion performance of oxygenated aromatic molecules, including laminar burning velocities (LBVs) and fuel consumption, and product formation in a Jet-Stirred Reactor (JSR), as well as to developing a detailed kinetic model. Three previous papers[18−20] focused on the study of phenol, benzaldehyde, benzyl alcohol, 2-phenylethanol, anisole, and guaiacol, respectively. In line with this previous work, the present paper focuses on the three cresol isomers and describes the first attempt at detailed kinetic modelling of their combustion, validated using new experimental results from a JSR and relating to LBVs.

-

As the methods used in the present study are largely the same as those described in our previous papers[18–20], this paragraph provides a brief overview of the theoretical and experimental methodologies employed, detailing only the aspects specific to cresol isomers.

Kinetic theoretical calculations

-

Ab initio quantum mechanical calculations are performed using the CBS-QB3 method[21] as implemented in Gaussian 16[22], and at the G4 level of theory[23] for which we used Gaussian 09 as our Gaussian 16 A version has a problem with G4. Briefly, the structures of reactants, products, and transition states are optimized at the B3LYP level as defined by the composite method. Hindrance potentials of internal rotations, calculated at the B3LYP/6-31+G(D) level of theory using rotation steps of 10 degrees are checked for the existence of lower energy conformers. The electronic energy of the lowest-energy structure of a species is converted to its enthalpy of formation using the atomization method. Thermal contributions to the enthalpy, entropy, and heat capacities are determined with methods form statistical mechanics with the Harmonic Oscillator Rigid Rotor (HORR) assumption. Those vibrations that resemble internal rotations are separately evaluated as 1-D hindered rotors[24] and their contributions are added separately. Corrections to the entropy for symmetry, electronic degeneracy and the existence of optical isomers are added before the thermodynamic data are converted to (and stored as) NASA polynomials. Rate expressions are calculated with transition state theory using these NASA polynomials as input, and quantum mechanical tunneling is accounted for using asymmetric Eckart potentials. All rate expressions reported in this study are given at their high-pressure limit.

The rationale for the choice of the calculation methods is that a large number of reactions needed to be calculated (see Supplementary File 1) to explore possible reactivity differences between the three cresol isomers. The available computational resources would not allow those to be done at higher calculation levels. The species involved in the cresyl oxidation contains 10 heavy atoms (C7H7O3), which should bring the rate expressions at 1 atm close to the high-pressure limit.

Experimental methods for JSR study and LBV measurements on a burner

-

In both setups, the flow rates of the oxygen and carrier gases (helium for JSR and nitrogen for LBV) were regulated by mass flow controllers. The liquid fuel flow rate was monitored using a Cori-Flow mass flow controller. This controller was fed by a pressurized stainless steel fuel tank and connected to an evaporation chamber that was also fed by the carrier gas. After mixing with oxygen, the gaseous mixture was transferred via a heated line (T = 398 K) to either the plenum chamber preceding the burner or the preheating zone of the JSR.

As in the case of phenol[18], special adaptations had to be made to handle these high-Mp fuels. The modifications mainly concerned the inlet of the gas-phase reactants. The cresol container was kept in a hot water bath until it was used to fill the stainless-steel tank that fed the liquid flow controller upstream of the evaporation chamber. To ensure a constant temperature of 353 K (i.e., above fuel Mp), the tank and all lines transferring liquid or gases toward the burner or the reactor were electrically heated and wrapped by insulation material.

Merk provided ortho-, meta-, and para-cresol with a purity of 99.0%. The mole fractions quantified from the JSR and the measured LBV, along with their uncertainties, are provided in an Excel spreadsheet Supplementary File 2.

Setup for species quantification during oxidation in a JSR

-

The oxidation of cresol isomers was investigated at a pressure slightly above 1 atm in a heated JSR consisting of a 92 cm3 fused silica sphere with four injection nozzles located at the center to provide turbulent jets and efficient mixing. The gases leaving the reactor were analyzed online by a gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a Q-Bond capillary column and a flame ionization detector (FID) preceded by a methanizer in order to quantify CO, CO2, and organic compounds containing two to six carbon atoms.

The heavy molecules (> C6) were cryogenically trapped after leaving the reactor. The trap's contents were then dissolved in acetone and analyzed in a third gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with an HP-5 capillary column, a mass spectrometer, and a flame ionization detector (FID). The chromatograms of the heavy molecules obtained during oxidation at 950 K are provided in Supplementary File 1 (Figs. SI-1, SI-2, and SI-3, respectively). Species identification was performed by comparing spectra with those in the NIST mass spectrometry database[25]. Uncertainties in these assignments are discussed further in study by Meziane[26].

Setup for LBV measurements on a burner using the heat flux method

-

The burner used to stabilize the laminar, premixed flames of reconstituted air and cresol is a perforated brass plate. The flame's adiabaticity is checked by measuring its temperature profile using eight K-type thermocouples soldered into the plate's surface. The thermocouples are arranged in a spiral from the center to the burner's periphery. If the temperature profile is flat, then it can be assumed that the heat from the flame to the burner is fully compensated by the heat flux from the burner to the fresh gases. The burner is heated to a temperature 50 K higher than the fresh gases, which are maintained at a constant temperature (Tinlet gases) of 398 K through a heated plenum chamber preceding the brass plate. Under those adiabatic conditions, the gas flow rate corresponds to the adiabatic flame burning velocity. The calculation of LBV uncertainties is detailed in the study by Delort et al.[20], and experimental details can be found in the experimental spreadsheet in Supplementary File 2.

-

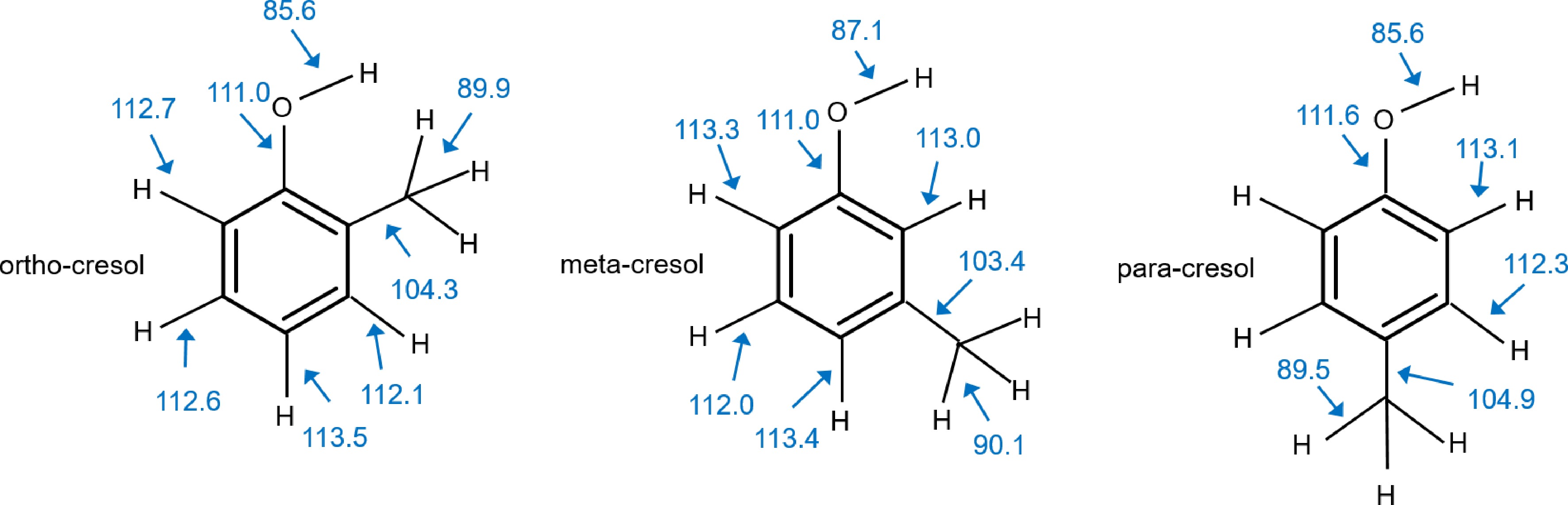

Enthalpies for bond fission at 298 K (bond dissociation energies BDE) calculated at the G4 level of theory for all three cresol isomers are shown in Fig. 1. The BDEs involving H atoms can be divided into three groups:

(1) the O-H bonds are with 85−87 kcal/mol, the lowest, and the one of the meta-isomer is somewhat stronger than those of ortho and para,

(2) the benzylic C-H bonds are around 90 kcal/mol and thus 3−5 kcal/mol stronger than the phenolic bond,

(3) the aryl-C-H bonds clearly separate from the others as they are with 112−113 kcal/mol significantly stronger and the position relative to the OH and CH3 substituents has little impact on this strength.

Also shown are the aryl-OH BDE, which are for all three isomers around 111−112 kcal/mol, and the aryl-CH3 BDE, which have values of around 103−105 kcal/mol. These bond strengths are relevant as they show that addition-elimination reactions replacing the CH3 group are more likely to occur than substitutions of the OH group. It also supports the observation stated in the introduction that cresols are produced in measurable amounts in toluene oxidation, since the similar aryl-OH and aryl-C-H bond strengths make the substitution of a hydrogen thermodynamically feasible.

The existence of weakly bound hydrogen atoms points to a prominent role of H abstraction reactions, while at the same time, unimolecular decompositions of cresol, analogous to phenol or toluene, should require high barriers and are unlikely to contribute. Therefore, we focused on the calculation of H abstraction reactions by six abstracting species: H, CH3, O, OH, O2, and HO2. Based on the values shown in Fig. 1, the enthalpies of reaction for H abstraction from the phenolic and benzylic groups are exothermic for H, CH3, O, and OH, approximately thermoneutral for HO2, and clearly endothermic for O2 (see Supplementary File 1: Table SII-1). Since this holds for all three isomers, no notable reactivity variations are expected. Also, important to notice is that H abstractions from the arylic C-H bonds by OH radicals are also exothermic. Since recent studies by Pratali Maffei et al.[12] and Wang et al.[27] on phenol pyrolysis reactions, come to the conclusion that H-abstractions from the stronger aryl-C-H bonds cannot be completely ruled out, the current study includes rate coefficient calculations for H abstraction reactions from aryl-C-H sites by OH radicals as well as H and O atoms. The results for all three cresol isomers are provided as parts of Supplementary File 1 (Table SII-3 to SII-5).

Most of the radicals formed in these H abstraction reactions are long-lived with respect to unimolecular reactions. For example, the well-known CO elimination pathway of phenoxy radicals has a barrier of about 54 kcal/mol[28], see Supplementary File 1 (Fig. SII-1). For the ortho-cresyl case, other relatively accessible pathways with barriers of around 65 kcal/mol involve the release of H atoms to form 6-methylidenecyclohexa-2,4-dien-1-one, a quinone methide. It can be formed either from the o-methylphenoxy radical or from the o-hydroxybenzyl radical. Both pathways are also shown in Supplementary File 1 (Fig. SII-1). Similar pathways are possible for the analogous para radicals, but not for the meta-cresyl radicals. The ortho-hydroxybenzyl radical presents a special case among all cresyl radicals because the proximity of the OH group allows for an easy H migration step from the hydroxyl group to the benzylic radical site, forming the about 5 kcal/mol more stable ortho-methyl phenoxy radical. The barrier for this isomerization is about 34.5 kcal/mol with excellent agreement between the CBS-QB3 and G4 methods. The rate expression for this reaction, calculated at the G4 level of theory, is included in Supplementary File 1 (Table SII-3). This reaction leads to an increased presence of ortho-methyl phenoxy radicals in ortho-cresol combustion compared to the meta and para cases, as it will be further seen in the flux analysis.

The main focus of the theoretical part of this study is on the reactions of the various isomer-specific cresyl radicals with molecular oxygen. For this purpose, the main features of possible radical − oxygen interactions have been calculated at the CBS-QB3 and G4 levels of theory. Based on the evaluation of 16 partial PES shown in Supplementary File 1 (Fig. SII-2), rate coefficients have been calculated for the most important pathways; related results are presented in Supplementary File 1 (Tables SII-3 to SII-5), and the structures of the species can be identified in Supplementary File 1 (Table SII-2). For oxygen molecule additions to radical sites, a rate constant of 2 × 1013 cm3mol−1s−1 is assumed.

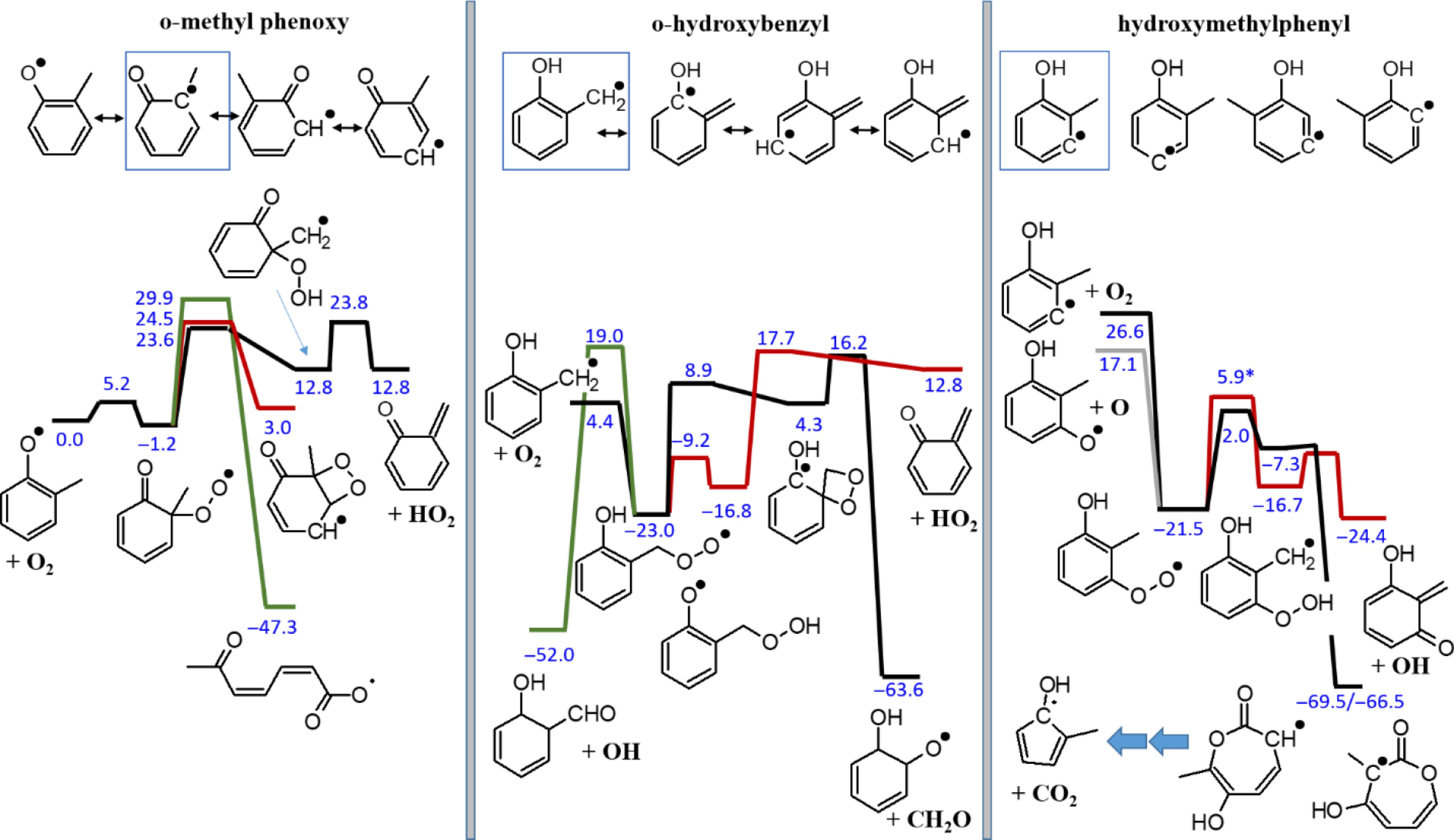

The complexity caused by the large variety of possible reaction pathways for the different types (methylphenoxy, hydroxybenzyl, or hydroxyl, methylphenyl) of cresyl radicals is illustrated in Fig. 2 for only three of the six possible selected ortho-cresyl radicals. Note that many more pathways exist even for this sub-set of radicals. The left-hand side shows an example for O2 addition to the o-methylphenoxy radical. It can be seen that the adduct is very unstable and re-dissociation dominates over product channels, which have barriers of 23.6 kcal/mol or more above the energy of the reactants. Regarding the o-hydroxybenzyl radical, the most promising addition channel produces the o-hydroxybenzyl peroxy radical. But even though its bond strength is around 27.4 kcal/mol and highly exothermic product channels exist, all the total barriers to these product channels are still clearly above the reactant energy of 4.4 kcal/mol.

Figure 2.

Simplified potential energy surfaces for O2 addition to o-cresyl radicals. Only reaction pathways for the boxed resonance structures of o-methylphenoxy (left) or o-hydroxybenzyl (center) are considered. On the right, only pathways for the first arylic o-cresyl isomer are shown. The lowest energy pathways are shown in black. The value marked (*) is calculated at the CBS-QB3 level of theory, all other values are G4 results. All 298 K enthalpies are relative to o-methylphenoxy+O2.

The right-hand side of Fig. 2 shows an example of O2 addition to an o-cresyl aryl radical. Caused by the high energy of the initial reactant, the total barriers for exothermic product channels are now clearly below the entrance energy. This makes these reactions feasible. All calculated PES are provided in Supplementary File 1 together with brief discussions about which of the shown channels are considered for the cresol isomer sub-mechanism development.

-

The detailed kinetic model (COLBRIv5), which is used in the present study, is provided in Supplementary Data 1–Data 3 under the CHEMKIN format, along with its thermochemical and transport data. This model is an update of the ones developed to simulate the combustion of toluene, styrene, the three xylene isomers, two of the trimethylbenzene isomers, phenol, anisole, benzaldehyde, benzylalcohol, 2-phenylethanol, and guaiacol (COLIBRIv1 to v4)[18–20]. As described in the respective papers, the COLIBRI model was primarily developed by merging the most accurate and detailed kinetic models of the species of interest found in the literature, e.g. studies[7,8,29,30]. This was supplemented by additional pathways and corrections. Overall, the accuracy of these models is preserved and sometimes improved in the developed model. Thanks to the use of the C0−C3 base model of Burke et al.[31], a good numerical convergence has been achieved for LBV simulations.

As in COLIBRIv1-v4, the toluene model was taken from Yuan et al.[14], who described the three isomers of cresol as a single lumped species, and their submechanism is based on that of Bounaceur et al.[1]. The latter submechanism includes the unimolecular decompositions yielding methylphenoxy and hydroxybenzyl radicals, the bimolecular H-abstractions by O2, ipso-additions on the ramifications, H-abstractions, and the decomposition of the formed radicals, notably through the pathways of hydroxybenzyl radical oxidation and of CO elimination from the methylphenoxy radical. Most of the rate constants are established by analogies with reactions of phenol and toluene. This submechanism does not include any reactions involving aryl H-atoms.

The purpose of this study was to replace the cresol submechanism in COLIBRI v4 with a more detailed model that considers the three isomers separately. Three new cresol submodels were developed (see Supplementary File 1: Tables SII-3 to SII-5).

To that end, the first step is to differentiate o-, m-, and p- geometries, as well as the isomers of hydroxybenzyl (HOA1CH2), methylphenoxy (OA1CH3), hydroxybenzylperoxy (HOA1CH2OO), hydroxybenzylhydroperoxy (HOA1CH2OOH), hydroxybenzyloxidanyl (HOA1CH2O), hydroxybenzaldehyde (HOA1CHO), hydroxybenzoyl (HOA1CO), and formylphenoxy (OA1CHO).

The pathways considered for these isomers include bimolecular reactions with O2 (reactions 1−2 in the list below), H-abstractions by OH, O, H, CH3, and HO2 radicals on the methyl and hydroxy groups (reactions 3−4), CO elimination from methylphenoxy isomers (reaction 5), O2 addition to hydroxybenzyl radicals, and decomposition of formed peroxy radicals (HOA1CH2OO) (reactions 5–9). Concerning the isomer-specific reactions, the isomerization between o-methylphenoxy and o-hydroxybenzyl radicals (reaction 10) and the formation of quinone methide from o- and p- hydroxybenzyl radicals (11) are also taken into account. Reaction (10) has a low barrier, which allows easy conversion of the reactant to the product, which is about 4 kcal/mol more stable than the BDEs shown in Fig. 1. This also explains why more phenoxy radicals are found in the flux analysis for the ortho case (see further in the text).

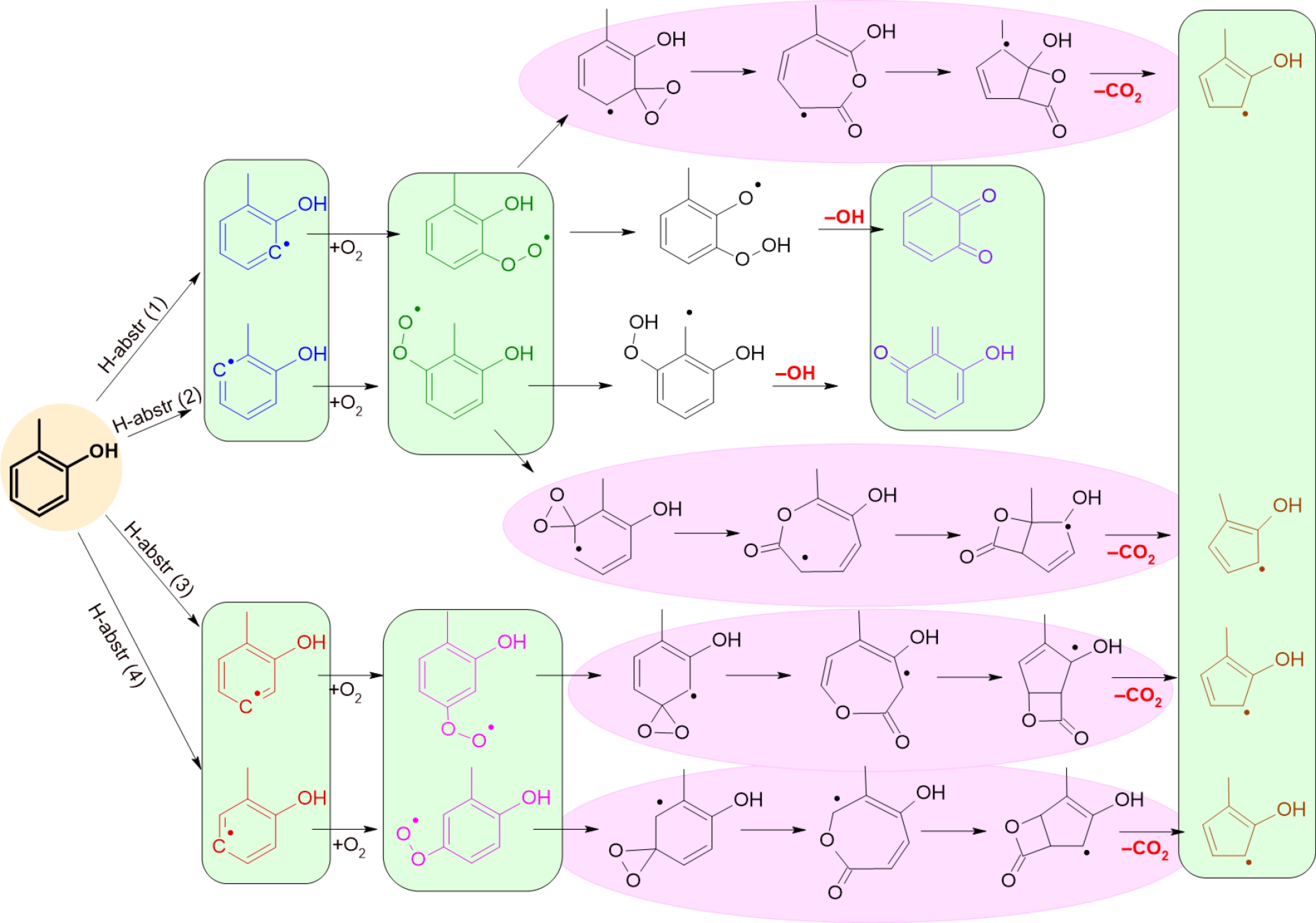

$ HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+{O}_{2}\leftrightarrow HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}+H{O}_{2} $ (1) $ HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+{O}_{2}\leftrightarrow O{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+H{O}_{2} $ (2) $ HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+R\leftrightarrow HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}+RH $ (3) $ HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+R\leftrightarrow O{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+RH $ (4) $ O{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}\leftrightarrow {C}_{5}{{H}_{4}CH}_{3}+CO $ (5) $ HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}+{O}_{2}\leftrightarrow HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}OO $ (6) $ HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}OO\leftrightarrow HO{A}_{1}CHO+OH $ (7) $ HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}OO\leftrightarrow O{A}_{1}OH+{CH}_{2}O $ (8) $ o{\text-},p{\text-}HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}OO\leftrightarrow o{\text-},p{\text-}O{C}_{6}{{H}_{4}CH}_{2}+{HO}_{2} $ (9) $ o{\text-}HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}\leftrightarrow o{\text-}O{A}_{1}{CH}_{3} $ (10) $ o{\text-},p{\text-}HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{2}\leftrightarrow o{\text-},p{\text-}O{C}_{6}{{H}_{4}CH}_{2}+H $ (11) While the first step of the cresol model development considered only reactions that start with the abstraction of the weakly bound phenolic or benzylic H atom, additional reactions starting from arylic radicals were added in a second step. These are illustrated for the case of o-cresol in Fig. 3. Although four different aryl radicals are formed, these can be grouped into two sets. The first set is formed through H-abstr (1), and H-abstr (2) and is characterized by the fact that the aryl radical site is in close proximity to a substituent group (OH or CH3). In contrast, the aryl radicals formed through H-abstr (3) and H-abstr (4) are isolated from the substituent groups. Because the peroxides formed from the first set can abstract an H atom from the neighboring group, they may readily form hydroperoxides, which, upon decomposition through β-scission, release OH radicals. This pathway is not available for the isolated aryl radicals, as shown in Fig. 3. Both sets are treated as single species to keep the size of the cresol sub-mechanism manageable. Furthermore, the first step of the CO2 formation channel is rate determining because the formation of the 7-membered lactone radicals is highly exothermic. This allows us to lump the entire sequence marked in pink into a single reaction. In these pathways, only the cresol isomer HOA1CH3 and the colored species in Fig. 3—the hydroxymethylphenyl radical isomers HOC6H3CH3-J and the hydroxymethylphenylperoxy radical isomers HOC6H3(CH3)OOJ—are considered. The intermediates in black are not included in the model.

Figure 3.

Detailed pathways, which can be envisaged as derived from the H-abstractions of aryl H-atoms from o-cresol. In COLIBRIv5, the species in the green boxes are lumped species (species of the same color are considered as a single one), black intermediates are not considered, line reactions in the pink ovals are not written in details, but only their initial reactant and products.

In pathways H-abstr (1), and H-abstr (2) in Fig. 3, which lead to OH- and CO2-release, hydroxymethylphenyl isomers and hydroxymethylphenylperoxy isomers are lumped. They are drawn in dark blue and green, respectively. The species involved in these pathways are written in the model as "Ja"; see reactions 12−15 in the list below. Following the same principle, in pathways H-abstr (3) and H-abstr (4), leading only to methylhydroxycyclopentadienyl isomers in the case of o-cresol, hydroxymethylphenyl isomers are lumped and drawn in red. Hydroxymethylphenylperoxy radical isomers are also lumped and drawn in pink. These species are named with the denomination "Jb"; see reactions 16−18. In our first attempt at a detailed model of cresol, the methylbenzoquinone and hydroxyquinone methide isomers are lumped together, regardless of the pathway or the initial cresol isomer. These isomers are named OC6H3(O)CH3, as seen in reaction 15. Similarly, methylhydroxycyclopentadienyl isomers are lumped together regardless of the cresol isomer from which they are derived, see the single compound drawn in brown. They are named HOC5H3CH3, as seen in reactions 14 and 18. Regardless of their impact on cresol consumption, reactions 12–18 are expected to affect cresol LBV because they release OH radicals, which are known to promote combustion intensity and lead to CO2 production, a highly exothermic process.

$ o{\text-}HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+R{}\leftrightarrow o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}CH}_{3}-Ja+R{}H $ (12) $ o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}CH}_{3}-Ja+{O}_{2}\leftrightarrow o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}(CH}_{3})OOJa $ (13) $ o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}(CH}_{3})OOJa\leftrightarrow HO{C}_{5}{{H}_{3}CH}_{3}+{CO}_{2} $ (14) $ o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}(CH}_{3})OOJa\leftrightarrow O{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}\left(O\right)CH}_{3}+OH $ (15) $ o{\text-}HO{A}_{1}{CH}_{3}+R\leftrightarrow o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}CH}_{3}-Jb+RH $ (16) $ o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}CH}_{3}-Jb+{O}_{2}\leftrightarrow o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}(CH}_{3})OOJb $ (17) $ o{\text-}HO{C}_{6}{{H}_{3}(CH}_{3})OOJb\leftrightarrow HO{C}_{5}{{H}_{3}CH}_{3}+{CO}_{2} $ (18) Finally, we added the reactions of hydroxybenzyl radical isomers with O-atoms, yielding hydroxybenzoxyl (reaction [19]), as analogies to the equivalent reaction of benzyl and O radicals. These reactions were lacking in the original submechanism. The terminations of the methylhydroxy isomers are updated using the equivalent reactions of the benzyl radicals described by Pratali Maffei et al.[12].

$ HO{A}_{1}C{H}_{2}+O\leftrightarrow HO{A}_{1}C{H}_{2}O $ (19) As detailed previously, the kinetic parameters of these newly considered pathways were obtained through theoretical calculations performed using the G4 method or the CBS-QB3 method (see Supplementary File 1: Tables SII-3 to SII-5).

The thermodynamic properties of all delumped and new species are calculated at the G4 level of theory and their transport data are calculated with an in-house code based on the work of Wang and Frenklach[32].

All the simulations that are described in more detail in this text, which were performed to test the previously described model, were carried out using the CHEMKIN software[33]. For the JSR data simulations, the transient solver in the PSR module was used over an integration time of 100 seconds to allow for the perfect establishment of the steady state.

-

The following part discusses the results obtained both in the JSR and in flames.

Experimental and modelling results on the JSR oxidation of cresol isomers

-

The following section describes the experimental measurements of the JSR oxidation of o-, m-, and p-cresols. These measurements were taken at temperatures between 600 and 1,100 K, with a residence time of 2 s, and with a fuel inlet mole fraction of 0.005. Three equivalence ratios were tested: 0.5, 1, and 2. First, it describes product identification and quantification. Then, it compares the experimental and simulated evolutions of the mole fractions of fuels and main products. Finally, it discusses flow rate analyses of the consumption of the three cresol isomers.

Product identification and quantification

-

Fuels and oxidation products were analyzed using the chromatographs discussed in the paragraph entitled "Setup for species quantification during oxidation in a JSR". Calibrations were performed by injecting standards, mainly of light products, when available, with a maximum relative error in mole fractions of around ± 5%. Otherwise, calibrations were performed using the ECN method, with maximum relative errors in mole fractions of approximately ± 10% for products and ± 20% for cresol isomers due to their low volatility.

The following products are detected in all three cresol isomers:

• C1−C4 oxygenated species: CO, CO2, acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), furan (C4H4O), acrolein (C2H3CHO), acetone (CH3COCH3), and methacrolein (C4H6O).

• C2−C5 hydrocarbons: Acetylene (C2H2), ethylene (C2H4), ethane (C2H6), propene (C3H6), allene (C3H4), propyne (C3H4), 1-butene (C4H8), 1,3-butadiene (C4H6), 2-butene (C4H8), 1,3-cyclopentadiene (C5H6), and 1,3-pentadiene (C5H8).

• Aromatic hydrocarbons: benzene (C6H6) and toluene (C7H8).

• Oxygenated aromatics: phenol (C6H6O), hydroxybenzaldehyde (C7H6O2), 9H-xanthene (C13H10O), and stilbenol (C14H12O).

More products were only observed specifically for one or two cresol isomers.

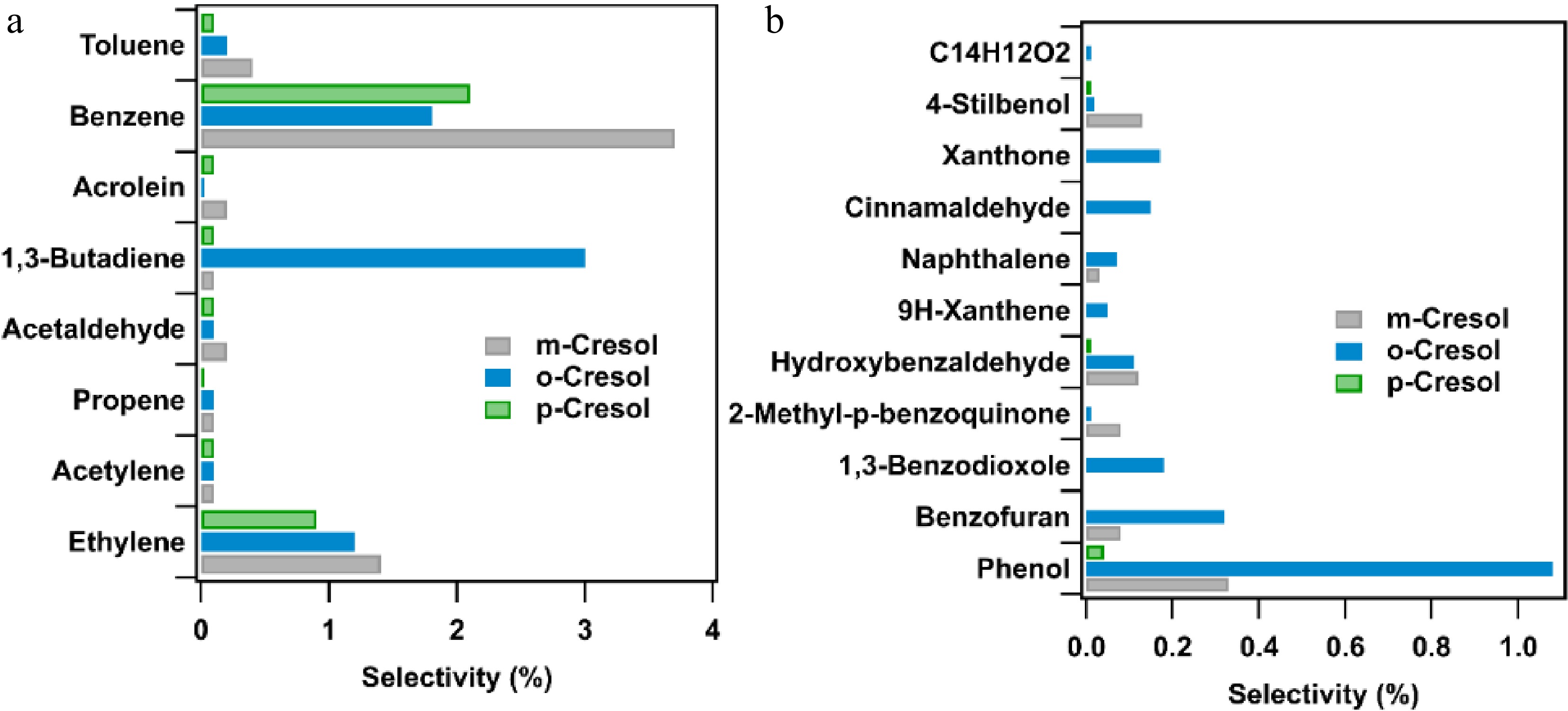

Figure 4 shows two selectivity diagrams for cresol isomer oxidation at 1,000 K with an equivalence ratio of 1. The two major products, CO and CO2, are not shown in Fig. 4 because their selectivities are 57%, 62%, and 64% for p-, m-, and o-cresol, respectively, and 30%, 33%, and 39% for m-, o-, and p-cresol, respectively. The products shown in Figs. 4a and 4b are quantified by online and offline analyses, respectively. Only the products with a selectivity above a given threshold are shown: 0.005 for Fig. 4a and 0.001 for Fig. 4b. The selectivities of the products shown in Fig. 4a are similar for all isomers, except for benzene, which is produced in large quantities from m-cresol. In contrast, there are significant differences among the species shown in Fig. 4b. Among the compounds displayed in Fig. 4b, phenol is common to the three isomers, and it has the highest selectivity regardless of the isomer, although the absolute yields differ by an order of magnitude, with most phenol produced by o-cresol and least for p-cresol. Hydroxybenzaldehyde, 9H-xanthene, and stilbenol are also present in all three reactants. 1,3-benzodioxole, xanthone, and an unidentified C14H12O2 compound are only formed with o-cresol. After comparing the mass spectrum of the C14H12O2 compound produced from o-cresol with possible molecules in the NIST database[25], no pertinent structure could be identified. Benzofuran, methyl-p-benzoquinone, and naphthalene are common to o- and m-cresol.

Figure 4.

Reaction product selectivity analyses for the oxidation of cresol isomers at φ = 1 and T = 1,000 K: (a) measured on-line (selectivity > 0.005), and (b) measured off-line (selectivity > 0.001, see structures in Table SI-1 in Supplementary File 1).

For p-cresol, notable production of unidentified compounds containing 14 carbon atoms is observed. Benzoquinone is also specific to p-cresol but forms with lower selectivity than those shown in Fig. 4.

Table SI-2 in Supplementary File 1 shows the carbon-atom balances for the oxidation of cresol isomers. For o-cresol, the carbon balance is approximately 100%, with deviations of up to 30% for φ = 0.5 and 1, and up to 50% for φ = 2. Higher deviations in the carbon balance are observed for m-cresol between 750 and 950 K and for p-cresol between 675 and 725 K, even below the onset of reactivity. This may be due to the significant uncertainties observed in the mole fraction of the fuels since these molecules are solids at room temperature with low melting points.

Experimental and simulated evolutions of species mole fraction with temperature

-

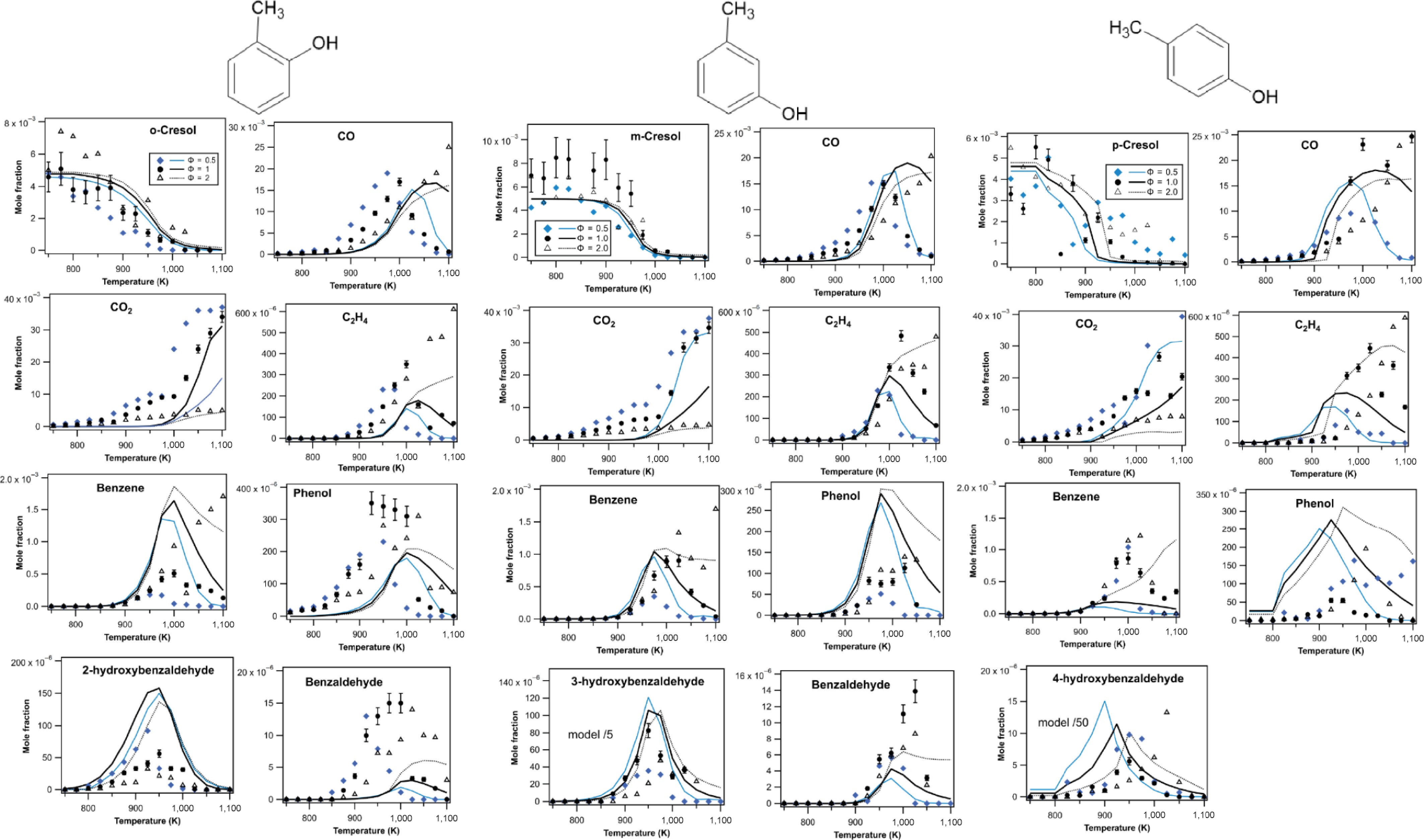

Figure 5 shows the comparison of the experimental and simulated variations of the mole fractions of fuel, the main common products (CO, CO2, ethylene, benzene, phenol, benzaldehyde) and 2-, 3-, and 4-hydroxybenzaldehydes) for each cresol isomer at three equivalence ratios: 0.5, 1, and 2. Figure SIII-1 in Supplementary File 1 presents the experimental mole fractions of all quantified light products common to the three isomers: CO, CO2, ethylene, ethane, propene, acetaldehyde, allene, propyne, acrolein, furan, and methacrolein. Figure SIII-2 in Supplementary File 1 presents the experimental mole fractions of all quantified heavy products common to the three isomers: cyclopentadiene, benzene, toluene, stilbenols, and hydroxybenzaldehydes. Figure SIII-3 in Supplementary File 1 plots a comparison of the experimental and simulated variations of the fuel mole fraction and the main products for the three cresol isomers at φ = 1, as well as simulations using the COLIBRI-V4 with reactions lumped for the three isomers.

Figure 5.

Experimental and simulated mole fractions of fuels and main products during the JSR oxidation of the three isomers of cresol (symbols are experiments and lines modelling using COLIBRIv5, τ = 2 s, P = 1.07 atm).

Figure 5 reveals an especially significant experimental uncertainty in cresol measurements due to the high melting/boiling points of these molecules. Nevertheless, uncertainties in the measurements of other compounds are normal.

Despite the high uncertainty, the fuel measurements in Fig. 5 indicate a reactivity onset above 850 K for o-cresol at φ = 1 and 2, above 800 K for o-cresol at φ = 0.5, above 900 K for m-cresol for any φ, and above 800 K for p-cresol for any φ. The newly developed model accurately reproduces these temperatures of reactivity onset except for o-cresol at φ = 0.5. This indicates that the primary reactions considered for cresol consumption are adequate.

Fair predictions are also made for the formation of CO below 1,000 K, CO2 above 1,000 K, ethylene, and benzene. The large, unexpected formation of CO2 below 1,000 K was also observed in our previous studies on the oxidation of aromatic compounds in JSR[4,18], but it remains unexplained. The increase in mole fraction of ethylene and benzene above 1,000 K when φ is increased is well predicted. The model reasonably predicts the temperature-dependent evolution of the mole fractions of phenol and hydroxybenzaldehydes, but significant discrepancies are observed in the maximum values. The discrepancy is particularly large for 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde from p-cresol, certainly due to the lack of detailed secondary chemistry for this compound.

In addition, it is worth noting that the newly developed COLIBRI-V5 model leads to significantly improved predictions for m-cresol quantified during the previous oxidation study of m-xylene, where cresol mole fractions were overestimated by a factor of around 20 by the COLIBRI-V1 model[4]. As shown in Supplementary File 1 (Fig. SVI-1), mole fractions are now of the same magnitude order as experimental data. There is a shift of 25 K at equivalence ratios of 0.5 and 1, but an excellent agreement at an equivalence ratio of 2.

Flow rate analysis

-

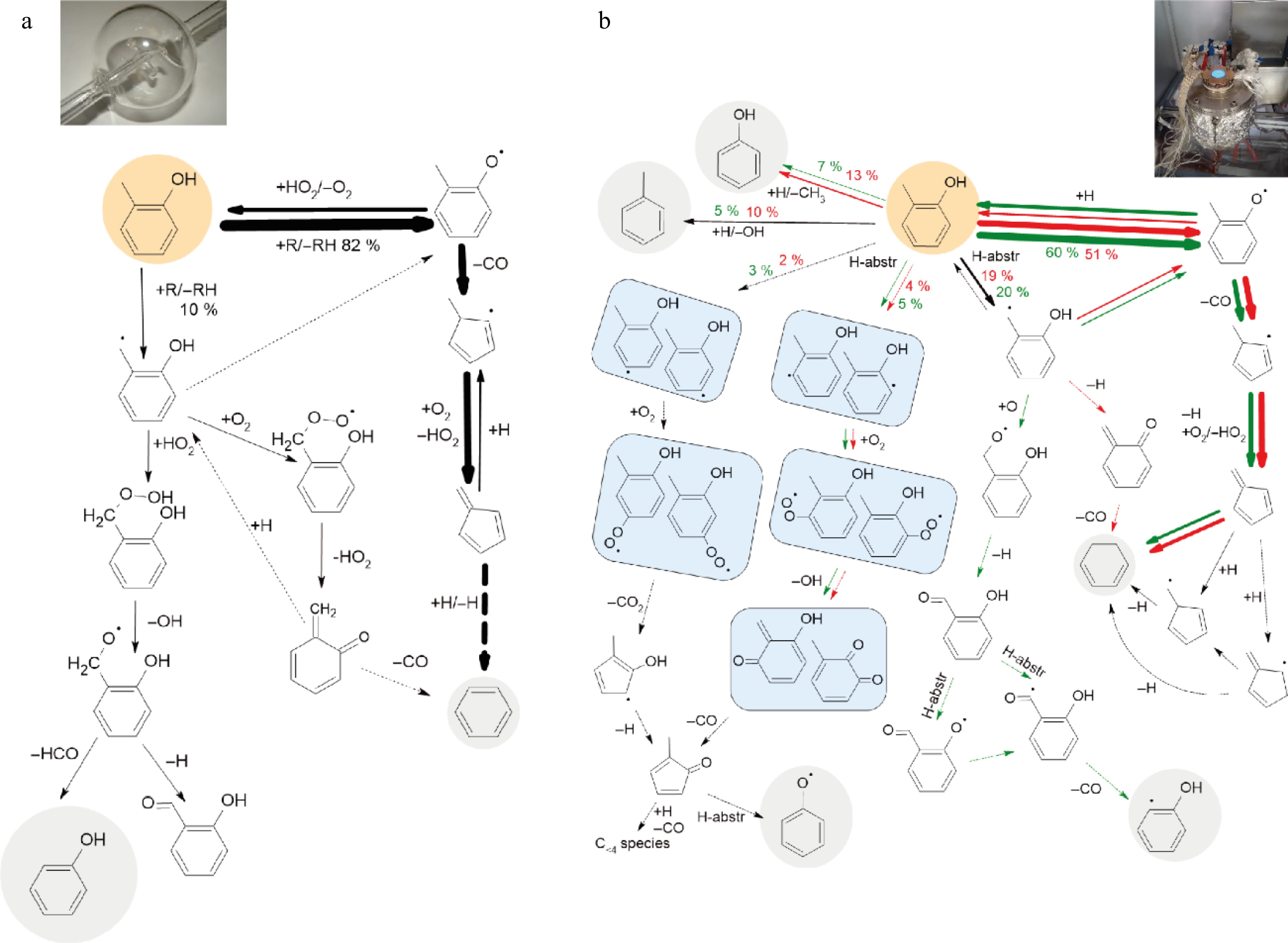

Figure 6a, Figs. SIV-1a and SIV-2a in Supplementary File 1 present the flow rate analyses using the COLIBRIv5 model for fuel consumption in JSR for φ = 1 at 1,000 K for o-, m-, and p-cresol, respectively. Under these conditions, the three cresol isomers are primarily consumed by hydrogen abstraction, primarily by hydroxyl (OH) radicals, yielding resonance-stabilized methyl phenoxy and hydroxybenzyl radicals.

Figure 6.

Flow rate analyses for o-cresol using COLIBRIv5: (a) in JSR at 1,000 K at φ = 1, (b) integrated analysis for fuel decomposition in o-cresol flames, green arrows are for φ = 0.8, and red ones for φ = 1.3 (only flow rates above 2% are shown, grey backgrounds show species, the mechanism of which is already presented in analyses for toluene[4,20], the thickness of the arrows is proportional to their relative flow rates).

However, using the newly calculated rate expressions, Figs. 6a, Figs. SIV-1a and SIV-2a in Supplementary File 1 reveal that the flow rates toward both radicals differ significantly depending on the cresol isomer. For o-cresol, 82% of the fuel is used to create methylphenoxy radicals and 10% to create hydroxybenzyl radicals. For o- and m-cresol, a significant amount of the methylphenoxy radicals react with HO2 radicals, reverting to the initial reactant. Nevertheless, methylphenoxy radicals are primarily consumed by losing CO and forming methyl cyclopentadienyl radicals. These latter radicals produce fulvene, which yields benzene, a major aromatic product observed in experiments. In the case of p-cresol, methylphenoxy radicals only decompose by losing a H-atom and produce p-quinone methide.

For the three isomers, the primary fate of the hydroxybenzyl radicals is to combine with HO2 radicals to produce a hydroperoxide. The hydroperoxide then decomposes to yield OH and benzoyl radicals. The decomposition of these radicals is the source of phenol and hydroxybenzaldehyde, which are also among the major aromatic products. In the case of o-cresol, the hydroxybenzyl radical can also add to O2 to form a peroxy radical, which decomposes to produce o-quinone methide.

The o- and p-isomers of quinone methide are unobserved products, for which COLIBRIv5 considers the addition of H-atoms to yield hydroxybenzyl radicals and their decomposition into CO and benzene. Further investigating the secondary reactions of these molecules would certainly improve the ability of the kinetic model to predict the oxidation of cresol isomers.

In the case of m-cresol and p-cresol, 3% and 2% of the fuel, respectively, is consumed by abstracting a phenyl H atom through the newly considered channels. The resulting radicals react with O2 to form peroxy radicals, which primarily undergo rearrangement and decomposition to produce CO2, H atoms, and methyl cyclopentadienone. The secondary reactions of the latter molecule produce CO, small hydrocarbons, and phenol.

These flow rate analyses lead us to think that the observed deviations between simulations and experiments are certainly due to the fact that the reactions of primary products, such as hydroxybenzaldehydes, quinone methides, and substituted cyclopentadienyl species, should also be considered in more details.

Experimental and modelling results about LBVs of cresol isomers

-

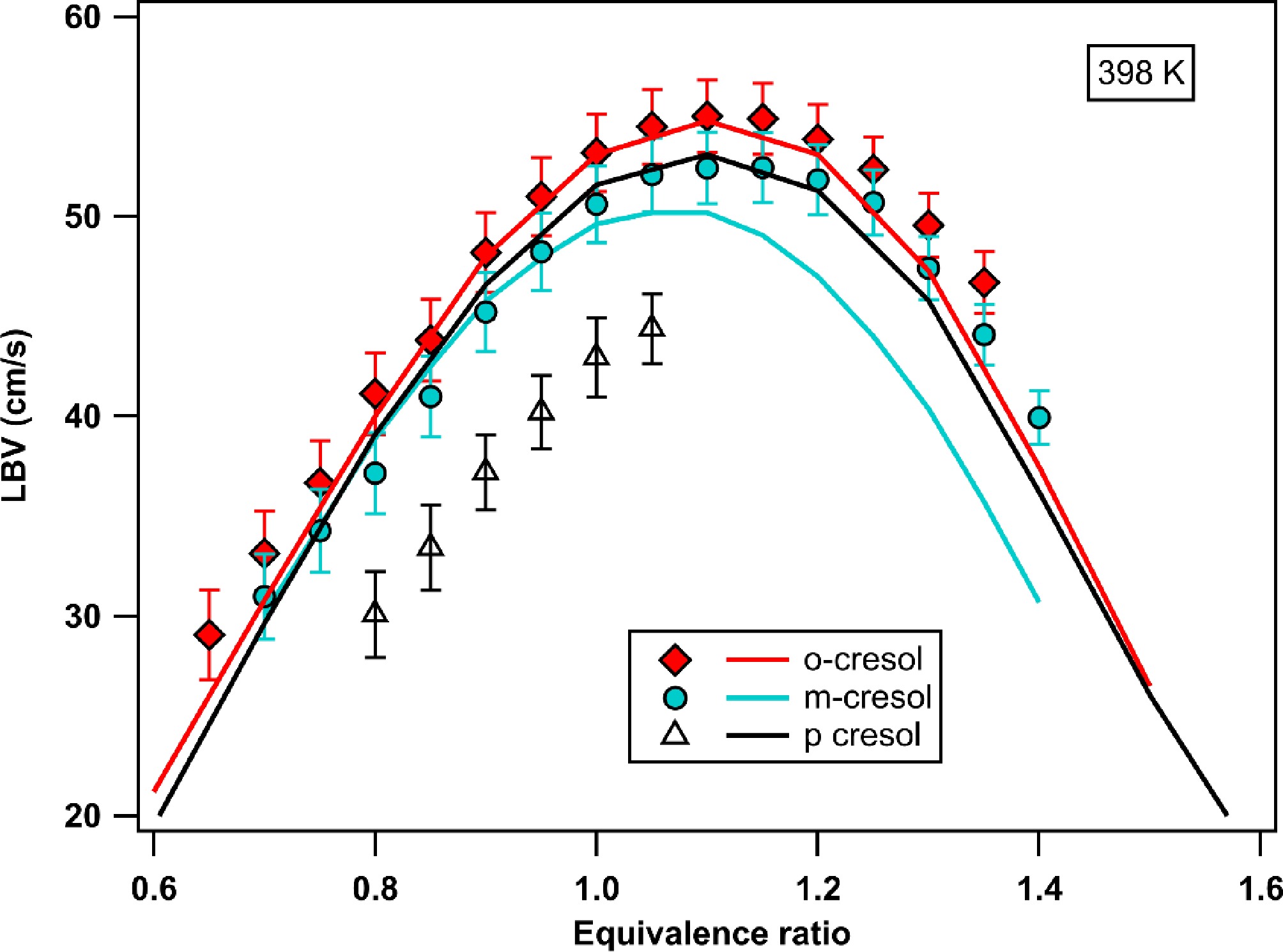

Fig. 7 shows the evolution of the measured and simulated LBV of the three cresol isomers as a function of equivalence ratio. LBV measurements were performed across the broadest range of equivalence ratios for which the flame remained stable, and the flame shape was flat in lean mixtures, and there was neither liquid condensation at the walls nor cellular instabilities occurring in rich mixtures[34]. Accordingly, a wide range of φ could be used for o- and m-cresol, whereas the range was more limited for p-cresol, for which the maximum LBV cannot be reached. The maximum LBV for o- and m-cresol is obtained at φ = 1, with o-cresol having a higher value (55.0 cm/s) than m-cresol (52.4 cm/s). The LBVs of p-cresol, for the φ at which they could be measured, are significantly lower than those of the other two isomers.

Figure 7.

Experimental (symbols with error bar) and simulated (using COLIBRIv5) LBV of cresols for a temperature of fresh gases of 398 K.

Figure 7 shows that the LBV simulations using COLIBRIv5 agree well with the o-cresol experimental measurements. The same is true for m-cresol up to φ = 0.95. However, for φ values greater than 0.95, the LBV values are underpredicted by approximately 2 cm/s at the LBV maximum. For p-cresol, the simulated values are significantly higher than the experimental values for all φ, by about 7 cm/s.

Figure 6b, Figs. SIV-1b and SIV-2b in Supplementary File 1 present the integrated flow rate analyses for φ = 0.8 and φ = 1.3, as calculated by the COLIBRIv5 model, for the LBV for o-cresol, m-cresol, and p-cresol, respectively.

Under flame conditions, H-abstractions leading to resonance-stabilized methyl phenoxy and hydroxybenzyl radicals remain the dominant processes. However, the three isomers exhibit increased contributions from ipso-additions of H-atoms (e.g., 23% of fuel consumption for o-cresol at φ = 1.3) and from the abstractions of phenylic H-atoms (e.g., 6% of fuel consumption for o-cresol at φ = 1.3), particularly under rich conditions.

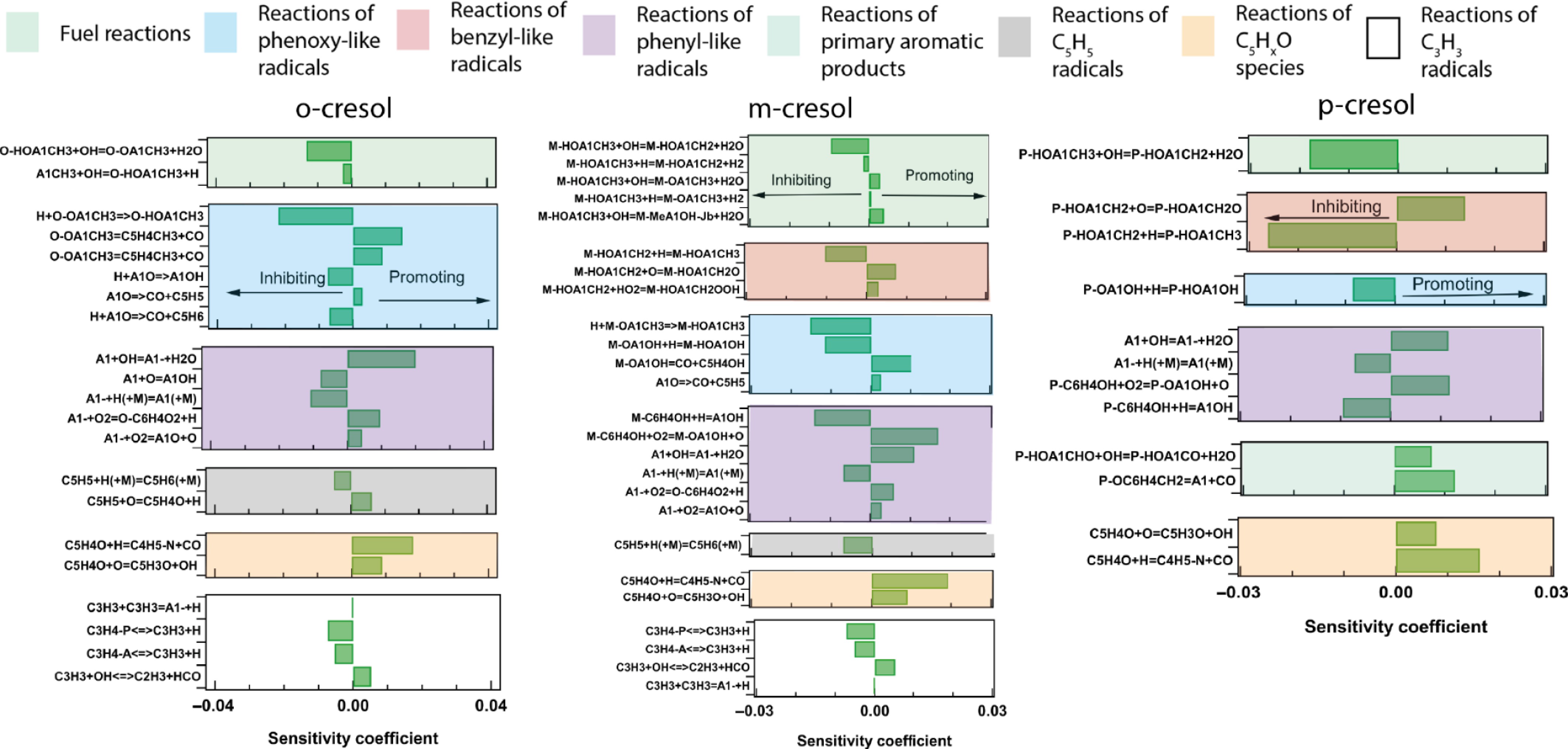

Figures SV-1 to SV-3 in Supplementary File 1 plot the most sensitive reactions on LBV for the three investigated reactants. As expected, the most sensitive reactions are H + O2 = H + O, CO + OH = CO2 + H, and several other C2− reactions. However, since only a few reactions are specific to cresol, Fig. 8 and Fig. SV-4 in Supplementary File 1 plot only the reactions of C3+ species among the 30 most sensitive reactions under lean conditions and rich conditions, respectively.

Figure 8.

Sensitivity analysis on the LBV of cresol isomers for a temperature of fresh gases of 398 K at φ = 0.8 using COLIBRIv5.

Figure 8 shows that the sensitive reactions fall into seven categories: fuel reactions, reactions of phenoxy-like, benzylic-like, phenylic-like, cyclopentadienyl and C5HXO species radicals, and reactions of propargyl radicals. This was also observed for the C7−C9 aromatic compounds studied by Delort et al.[20]. The same reaction categories are found in Supplementary File 1 (Fig. SV-4), except for the reactions of C5HXO species. In accordance with the channels of importance for fuel consumption, Fig. 8 shows a very different picture for the three isomers.

In the case of o-cresol, under lean conditions, the two fuel reactions with the highest sensitivity coefficients are the H-abstraction by OH, which yields methylphenoxy radicals and is the primary channel of fuel consumption, according to Fig. 6a, and the ipso-addition of H atoms, which yields toluene and OH. This last reaction is less sensitive under rich conditions. Both reactions have an inhibiting effect: the first one because it leads to radicals involved in the most inhibiting reaction among all the reactions of C3+ species displayed in Fig. 8, the combination of methylphenoxy radicals and H-atoms, the second because it consumes H-atoms. As it was also noted for other aromatic compounds, e.g., benzaldehyde or styrene[20], the reaction with the highest promoting effect among the reactions of C3+ species displayed in Fig. 8 is the formation of phenyl radicals by H-abstraction by OH from benzene. This compound is involved in channels that consume most of the o-cresol, as shown in Fig. 6b.

In the case of m-cresol, five H-abstractions from the fuel are among the C3+ species reactions displayed in Fig. 8 and Fig. SV-4 in Supplementary File 1. The two reactions leading to hydroxybenzyl radicals are the channels consuming the largest part of the fuel, and they have an inhibiting effect. On the contrary, the competing reactions that produce methylphenoxy and phenylic-like radicals have a promoting effect. The reaction with the largest inhibitory effect is the combination of hydroxybenzyl radicals with an H-atom. The reaction with the largest promoting effect is the branching reaction with O2 of hydroxyphenyl radicals. These compounds are involved in channels that consume a significant amount of m-cresol, as shown in Supplementary File 1 (Fig. SIV-1b).

In the case of p-cresol, only one reaction from the fuel is among the C3+ species reactions displayed in Fig. 8 and Fig. SV-4 in Supplementary File 1. It is the H-abstraction involving OH, which leads to the formation of the hydroxybenzyl radicals. Two reactions consuming these radicals have amongst the highest sensitivity coefficients: their combination with H-atoms giving back the reactant with an inhibiting effect, their reaction with O-atoms yielding the alkoxyradicals, which are the main source of p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, with a promoting effect.

Although the formation of p-quinone methide is not shown in Fig. 8, while it appears in Supplementary File 1 (Fig. SV-4) as the decomposition of hydroxybenzyl radical, an additional category of reactions has to be considered only for p-cresol: the reactions of primary aromatic products. This category includes the H-abstraction by OH radicals from p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, only under lean conditions, and the decomposition of p-quinone methide into benzene and CO for both equivalence ratios.

The high sensitivity coefficients observed for these two reactions, which have a significant promoting effect, suggest that the simulations of p-cresol LBV might be improved by considering in more detail the reactions of p-hydroxybenzaldehydes and p-quinone methide. This is particularly true for p-quinone methide, for which the current mechanism only contains the above mentioned decomposition reaction with an assumed rate expression based on that of o-quinone methide taken from the work of Dorrestijn et al.[35]. Alternative unimolecular consumption reactions for this species (i.e., the production of fulvene instead of benzene, the retro-Diels-Alder reaction forming acetylene and buta-1,3-diene-1,4-dione, or dimerization reactions leading to the observed C14 species), as well as radical addition reactions and their subsequent chemistry, might reduce the predicted LBV and should be considered in future model updates.

-

This paper is the first to investigate the oxidation and combustion of cresol, making a distinction between its three isomers. A new detailed kinetic model has been developed, building on the model that was recently developed for the oxidation and combustion of monoaromatic compounds by Delort et al.[20]. This study indicates that cresols have a rich chemistry with a high number of reaction pathways to be considered, as demonstrated by the many PES provided in Supplementary File 1. Due to this complexity, the theoretical work focuses solely on primary cresol reactions and barely touches on secondary chemistry. In the provided PES, in some cases, rather large deviations between G4 and CBS-QB3 results suggest that higher levels of theory should be applied in the future. Theoretical calculations at the G4 level indicate that there are significant differences in the rate constants for hydrogen abstractions from the fuel, which leads to the formation of either methylphenoxy or hydroxybenzyl radicals. The formation of the methylphenoxy radical is significantly favored for o-cresol.

New experimental data have been presented and will be very valuable targets for further development steps. These results demonstrate that, although the three isomers exhibit similar reactivity during JSR oxidation, significant differences in the nature and quantity of the products are evident. Significant differences between isomers have also been reported in LBV, but are not yet fully explained by the model. The discrepancies between the experimental data and the simulation results obtained using the newly developed model suggest that the secondary chemistry also needs to be considered in more detail, particularly for quinone methides.

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, (BUILDING A LOWCARBON, CLIMATE RESILIENT FUTURE: SECURE, CLEAN AND EFFICIENT ENERGY) under Grant Agreement No 101006744 and of COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) Action CYPHER CA22151. The content presented in this document represents the views of the authors, and the European Commission has no liability in respect of the content. HHC acknowledges funding by the Aragón Government (ref. T22_23R), cofounded by EFRD 2014-2020 "Construyendo Europa desde Aragón".

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Herbinet O, Battin-Leclerc F; data collection: Meziane I, Delort N, Carstensen HH, Bounaceur R; analysis and interpretation of results: Meziane I, Delort N, Carstensen HH, Herbinet O, Battin-Leclerc F; draft manuscript preparation: Battin-Leclerc F, Carstensen HH. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All the data (experimental data and models) that support the findings of this study are available as the electronic supplementary information related to this paper.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The aim of ARAID is to generally strengthen basic research in Aragón, Spain, by supporting researchers such as HHC. The current study was done solely with the intention to improve our knowledge of cresol oxidation chemistry; hence, no conflict of interest exists.

- Supplementary File 1 Supplementary description, figures and tables to this study.

- Supplementary File 2 Experimental data.

- Supplementary Data 1 COLIBRIv5_mechanism.

- Supplementary Data 2 COLIVRIv5_thermodynamic data.

- Supplementary Data 3 COLIVRIv5_transport data.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Herbinet O, Meziane I, Delort N, Bounaceur R, Carstensen HH, et al. 2026. Gas-phase oxidation chemistry of the three cresol isomers. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 51: e003 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0027

Gas-phase oxidation chemistry of the three cresol isomers

- Received: 30 June 2025

- Revised: 22 September 2025

- Accepted: 07 November 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: Despite their importance in the chemistry of aromatic compounds and as platform molecules from lignin decomposition, cresol isomers (ortho, meta, and para) are currently only considered as a single lumped species in detailed kinetic models. Furthermore, there are no experimental results available on the combustion of cresol isomers due to their extremely low volatility. This paper presents a recently developed detailed kinetic mechanism for the combustion of cresol isomers, driven by theoretically calculated rate constants for H-abstractions from the three isomers and for the decomposition of the addition products of the resulting radicals with O2. It also presents the first-ever quantification of species during the oxidation of the cresol isomers in a jet-stirred reactor, as well as the first measurements of the laminar burning velocity of cresol isomers using a flat flame burner, with a different behavior for p-cresol compared to the other two. The new detailed kinetic model produces accurate predictions of mole fractions of fuel, CO, CO2, ethylene, and more deviations for heavier products. Experimental data showed similar reactivity but significant differences in the nature and distribution of products depending on the position of hydroxy and methyl groups. Satisfactory burning velocity predictions were obtained for o-cresol and fair ones for m-cresol in lean mixtures. However, the large deviations observed for p-cresol suggest the need for further model improvement. Flow rate analyses revealed significant differences in the primary fuel consumption steps between the three isomers, explaining the observed differences in the products.