-

Chili peppers (Capsicum spp.), belonging to the Solanaceae family, are among the most widely cultivated vegetable crops globally. The chili pepper species most extensively grown in subtropical and temperate regions worldwide include Capsicum (C.) annuum, C. frutescens, C. baccatum, C. pubescens, and C. chinense[1].

Valued for their pungent fruits, chili peppers are used as spices, vegetables, and condiments[2]. In addition to their culinary importance, chili peppers are rich in essential nutrients such as vitamins A and C, carotenoids, and capsaicinoids, which contribute to their potential health benefits[3,4]. These crops also hold significant cultural and economic value, being integral to many global cuisines and playing a key role in the agricultural economies of several countries[5,6].

Despite their importance, the genetic improvement of chili peppers has been hindered by the lack of efficient regeneration and transformation methods. Regeneration, which involves recovering whole plants from transformed cells or tissues, is a critical step in the development of transgenic plants[7]. However, peppers are recalcitrant in nature, and the exact mechanism behind this recalcitrance remains poorly understood. Therefore, exploring the impact of various plant growth regulators (PGRs) and the application of novel PGRs is critical for improving pepper regeneration, which is essential for developing efficient transformation protocols in Capsicum species[8]. The first study on regenerating pepper plants was published by Gunay & Rao[9]. Since then, numerous studies have demonstrated that regenerating pepper plants in laboratory cultures is challenging due to factors such as natural resistance to growth changes, rosette bud formation, sensitivity to ethylene, and different genotype variations[8−12].

Successful regeneration in Capsicum species is influenced by several critical factors, including the type of explant used, the age of the plant[12−14], plant growth regulator compositions[8,15], and the genotype specificity[16,17]. Despite extensive research, two major challenges persist in Capsicum regeneration systems: low shoot formation frequency and the frequent development of abnormal shoot structures. These morphological abnormalities, variously described as rosette shoots, leafy shoots, or blind leaves, typically fail to elongate properly due to the absence of a functional shoot apical meristem[11,18]. Such developmental defects significantly hinder the establishment of efficient regeneration protocols[19,20]. Although some success has been achieved in studies on regeneration from various explants, the efficiency remains insufficient for genetic engineering applications[21,22].

Numerous efforts have been made to achieve successful regeneration of Capsicum, primarily through the process of organogenesis[18,23]. Studies indicate that the selection of plant genotype, type of explant, and the concentration and combination of plant growth hormones are critical factors determining the regeneration of chili plants[22,24,25]. A notable study reported a high transformation efficiency of 40.8% in C. annuum using F1 hybrids of four cultivars (Xiangyan 10, Zhongjiao 2, Zhongjiao 5, and Zhongjiao 6)[26]. Despite this progress, inconsistencies in regeneration efficiency across different genotypes and explant sources highlight the need for further optimization in different recalcitrant crops. A recent study developed an engineered tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) system for efficient, non-transgenic delivery of CRISPR/Cas tools. By removing insect-transmission genes, the modified TSWV delivers Cas nucleases and base editors, enabling high-efficiency somatic editing across diverse species. Regenerated plants show heritable mutations without residual viral vectors, offering a promising solution for genome editing in transformation-resistant crops[27]. A highly efficient pepper genome-editing method achieved transgene-free, heritable mutations in 77.9% of regenerated plants by bypassing stable transformation, thereby avoiding bottlenecks in totipotent cell selection and in vitro regeneration[28]. Together, these approaches address critical barriers in pepper functional genomics and trait improvement while offering scalable solutions for other transformation-recalcitrant species.

Numerous efforts have been made to enhance the regeneration and transformation efficiency in chili peppers, including optimizing culture conditions, testing different explant sources, and exploring various plant growth regulators and other bioactive compounds[11,24,29,30]. However, the identification and characterization of novel regeneration factors with broad applicability across diverse Capsicum genotypes remain an ongoing and dynamic area of research[29]. Recent advances in plant biotechnology have demonstrated that manipulating key developmental regulators (DRs) can successfully induce the regeneration potential of different tissue cells, thereby enhancing both regeneration and transformation efficiencies. Several important DRs, such as WUSCHEL (WUS), BABY BOOM (BBM), ISOPENTENYL TRANSFERASE (IPT), PLETHORA 5 (PLT5), GENERAL REGULATORY FACTOR (GRF), and GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR (GIF), have been widely studied for their roles in promoting plant regeneration[31−34]. Additionally, recent research has identified REGENERATION FACTOR 1 (REF1) as a novel regeneration factor, offering new possibilities for improving regeneration protocols in recalcitrant species[35].

This study aimed to enhance chili pepper regeneration efficiency using REF1, a novel regeneration factor[35]. Specifically, the effects of REF1 on the regeneration of various C. annuum cultivars were investigated. The goal was to evaluate REF1's effect on regeneration efficiency in Capsicum and to develop an efficient and stable regeneration protocol.

The successful development of an efficient regeneration system for chili peppers using the REF1 regeneration factor would have significant implications for crop improvement and genetic engineering efforts. REF1 could potentially be extended to other Capsicum species and recalcitrant plant species, expanding its applications in plant biotechnology and accelerating the development of improved crop varieties with enhanced agronomic traits.

-

The recently discovered peptide, REF1, was used in this study to evaluate its effect on regeneration efficiency in chili pepper varieties[35]. Eight C. annuum cultivars (Zunla-1, CM334, ZJ6, ZSG, 0818, 146, 243, and 245), and one C. eximum cultivar (354) were used as the experimental materials for this study.

Seed sterilization

-

Seeds were surface sterilized following a stepwise procedure. First, they were rinsed three times with double-distilled water (ddH2O) to remove surface debris, followed by immersion in 70% ethanol for 1 min. The seeds were then washed three times with ddH2O to remove residual ethanol, treated with 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 25 min to penetrate and disinfect the seed coat, and finally rinsed at least five times with ddH2O inside a laminar flow hood to eliminate any chemical residues. The sterilized seeds were dried on sterile filter paper to prevent microbial growth during germination.

Growth conditions

-

Twenty seeds per accession were distributed in two to three sterile jars containing seed germination medium Table 1. The jars were placed in a growth chamber under a 16 h light photoperiod at 25 °C and 75% humidity to provide optimal conditions for germination. The seeds were cultivated under a photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h darkness at a controlled temperature of 25 °C for approximately two weeks, until cotyledons and hypocotyls reached the appropriate size for explant preparation.

Table 1. Seed germination medium.

Components Concentrations MS (g/L) 4.43 Sucrose (g/L) 30 Agar (g/L) 8 Explant preparation

-

Cotyledons were dissected into 1.5 cm fragments, while hypocotyls were sectioned into approximately 1 cm fragments. The excised explants were immediately placed in the soaking medium containing 0.2 mg/L 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) specified in Table 2 to prevent desiccation prior to transfer to the callus induction medium.

Table 2. Explants soaking medium.

Components Concentrations MS (g/L) 4.43 Sucrose (g/L) 30 Kinetin (g/L) 0.1 2,4-D (mg/L) 0.2 Callus induction

-

After soaking, the explants were dried on filter paper to remove excess moisture and then transferred to a callus induction medium containing 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), zeatin (ZT), and 2,4-D/CaREF1 under different treatments outlined in Table 3. The cultures were maintained in a growth chamber programmed with a 16 h light cycle, at 25 °C and 75% humidity. Callus formation typically occurred within two to three weeks. The callus induction rate was calculated using the following formula:

$ \mathrm{Callus\ induction\ rate\ ({\text{%}})=\ \frac{Number\ of\ callus}{Number\ of\ explants}\times100{\text{%}}} $ Table 3. Growth medium formulations with different cytokinins, along with, and without CaREF1 for callus formation.

Components Tc1 Tc2 Tc3 Tc4 Tc5 MS (g/L) 4.43 4.43 4.43 4.43 4.43 Sucrose (g/L) 30 30 30 30 30 Agar (g/L) 8 8 8 8 8 BAP (mg/L) 5 5 5 5 5 IAA (mg/L) 1 1 1 1 1 2,4-D (mg/L) − − − − 2 CaREF1 (nM) − 1 1.5 2 1 NAA (mg/L) 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 ZT (mg/L) 2 2 2 2 2 Shoot formation

-

Following callus formation, explants along with the developed callus were transferred to a shoot formation medium supplemented with varying concentrations of silver nitrate (AgNO3), with or without CaREF1, as specified in Table 4. The explants were sub-cultured at two-week intervals and monitored until shoot formation was observed. The shoot formation rate was calculated as:

$ \rm Shoot\; formation \;rate \;({\text{%}}) = \dfrac{No.\; of \;shoots}{No. \;of\; callus}\times 100{\text{%}}$ Table 4. Growth medium formulations with different treatments of AgNO3, along with, and without CaREF1 for shoot formation.

Components Tsf0 Tsf1 Tsf2 Tsf3 MS (g/L) 4.43 4.43 4.43 4.43 Sucrose (g/L) 30 30 30 30 Agar (g/L) 8 8 8 8 BAP (mg/L) 5 5 5 5 IAA (mg/L) 1 1 1 1 CaREF1 (nM) − − 1 1 AgNO3 (mg/L) − 5 5 10 NAA (mg/L) 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 ZT (mg/L) 2 2 2 2 Shoot elongation

-

For shoot elongation, developed shoots were transferred to a medium containing varying concentrations of gibberellic acid (GA3) with or without CaREF1, as specified in Table 5, and incubated until shoot elongation was observed. The shoot elongation rate was calculated as:

$ \rm Shoot \;elongation \;rate \;({\text{%}}) =\dfrac{ No. \;of \;elongated \;shoots}{No.\; of \;formed \;shoots}\times 100{\text{%}}$ Table 5. Growth medium formulations with different treatments of GA3, along with, and without CaREF1 for shoot elongation.

Components Tse0 Tse1 Tse2 Tse3 MS (g/L) 4.43 4.43 4.43 4.43 Sucrose (g/L) 30 30 30 30 Agar (g/L) 8 8 8 8 BAP (mg/L) 5 5 5 5 IAA (mg/L) 1 1 1 1 CaREF1 (nM) − − 1 1 GA3 (mg/L) − 0.5 0.5 1 NAA (mg/L) 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 ZT (mg/L) 2 2 2 2 Root formation

-

Elongated shoots were transferred to a rooting medium containing indole-3-butyric acid (IBA)/IAA/CaREF1 (Table 6) to induce root formation. They were maintained in a growth chamber with a 16 h light photoperiod at 25 °C and 75% humidity. Root formation rate was calculated using the formula:

$ \rm Root \;formation \;rate\; ({\text{%}}) =\dfrac{ No. \;of \;plants \;with \;roots}{No. \;of \;elongated \;shoots }\times 100{\text{%}}$ Table 6. Growth medium formulations with different treatments of (IBA and IAA) along with, and without CaREF1 for root formation.

Components Tr0 Tr1 Tr2 Tr3 MS (g/L) 4.43 4.43 4.43 4.43 Sucrose (g/L) 30 30 30 30 Agar (g/L) 8 8 8 8 IBA (mg/L) − 1 1 − IAA (mg/L) − − − 1 CaREF1 (nM) − − 1 1 Regeneration efficiency and acclimatization

-

After rooting, plants were carefully removed from the rooting medium and washed with tap water to prepare them for the acclimatization process. During this phase, the plantlets were placed in a water-based environment under controlled conditions for 7 d to enable gradual adaptation. After the week-long water phase, the plantlets were transferred to small pots filled with a soil-compost mixture in a 2:1:1 ratio. This specially formulated blend provided an ideal growing medium to support root development and overall growth during acclimatization.

The ratio (%) of regenerated plants was determined using the formula:

${ \rm The \;ratio \;({\text{%}}) \;of\; regenerated \;plants = \dfrac{No.\; of\; the\; whole\; plants\; with\; roots}{Total\; number\; of\; explants\; used}\times 100{\text{%}}}$ Microscopic image analysis of callus and shoot formation with and without CaREF1

-

Microscopic image analysis was performed to evaluate the cellular organization and tissue morphology of callus and shoot formation in explants cultured with and without CaREF1. Samples were collected at the callus and shoot formation stages to ensure a comprehensive analysis of tissue differentiation and growth patterns. Thin sections of the explants were prepared using a microtome, ensuring precise and uniform thickness for optimal microscopic observation. These sections were then carefully mounted on slides for further examination. Observations were carried out using a Leica model BX51TRF microscope.

Statistical analysis and replicates

-

Each experimental treatment was repeated three times (biological replicates), with a sample size of 60 cotyledons, 48 hypocotyls, and ten root explants per replicate. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), employing one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Data were also visualized using GraphPad Prism. The original data for the bar charts in Figs 1–6 can be found in Supplementary Tables S1–S12.

-

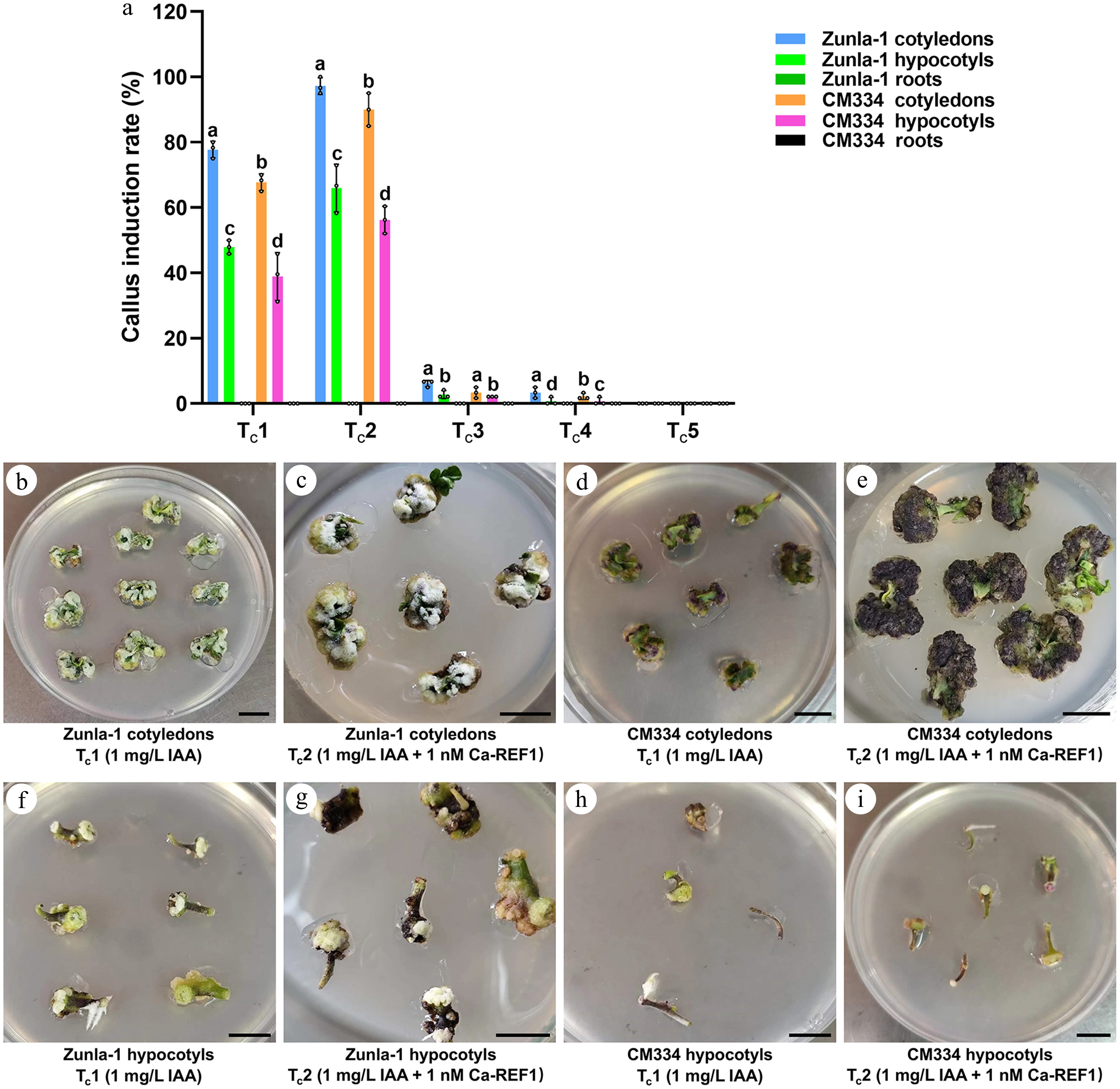

The callus induction experiment in pepper varieties demonstrated differential responses between two varieties, Zunla-1 and CM334, across five treatments: treatment 1 for callus induction (Tc1) (1 mg/L IAA), Tc2 (1 mg/L IAA + 1 nM CaREF1), Tc3 (1 mg/L IAA + 1.5 nM CaREF1), Tc4 (1 mg/L IAA + 2 nM CaREF1), and Tc5 (1 mg/L IAA + 2 mg/L 2,4-D + 1 nM CaREF1). In Zunla-1 cotyledons, treatment Tc2 resulted in the highest callus induction with a rate of 97.2% (175/180) (Fig. 1a, c), followed by Tc1 with a rate of 77.8% (140/180) (Fig. 1a, b), indicating a pronounced sensitivity to CaREF1 and auxin-based formulation. In contrast, Tc3 and Tc4 were the least effective with rates of 6.1% (11/180) and 3.7% (6/180) (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1a, b), respectively, while Tc5 exhibited no callus formation (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1c). For Zunla-1 hypocotyls, higher callus induction with a rate of 66.0% (95/144) (Fig. 1a, g) was achieved under Tc2, followed by Tc1 with a rate of 47.9% (69/144) (Fig. 1a, f), whereas the remaining treatments showed minimal effectiveness (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1d–f). Notably, Zunla-1 roots exhibited no callus formation across all treatments (Fig. 1a), highlighting their limited regenerative capacity.

Figure 1.

Callus induction rate (%) in Zunla-1 and CM334 under different hormonal treatments. (a) Bar chart of callus induction rate (%) for two pepper varieties, Zunla-1 and CM334, and two explant types, cotyledons and hypocotyls, under five treatments. Treatments include Tc1 (1 mg/L IAA), Tc2 (1 mg/L IAA + 1 nM CaREF1), Tc3 (1 mg/L IAA + 1.5 nM CaREF1), Tc4 (1 mg/L IAA + 2 nM CaREF1), and Tc5 (1 mg/L IAA + 2 mg/L 2,4-D + 1 nM CaREF1). The annotations above the bars, marked as 'a', 'b', 'c', etc., signify statistical significance (p < 0.05), where bars sharing the same letter indicate no significant difference. (b)–(e) Show callus formation images for Zunla-1 and CM334 cotyledons under the respective treatments Tc1 and Tc2, respectively. (f)–(i) Show callus formation images for Zunla-1 and CM334 hypocotyls under the respective treatments Tc1 and Tc2, respectively. Scale bars indicate 1 cm.

In CM334 cotyledons, Tc2 exhibited the highest callus induction with a rate of 90.0% (162/180) (Fig. 1a, e), followed by Tc1 with a rate of 67.8% (122/180) (Fig. 1a, d), indicating a significant sensitivity to CaREF1 and auxin-based formulation. Conversely, Tc3 and Tc4 resulted in significantly reduced callus formation with rates of 3.3% (6/180) and 2.2% (4/180) (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1g–h), respectively, suggesting that elevated concentrations of CaREF1 could be inhibitory to regeneration in these varieties. Treatment Tc5 demonstrated limited efficacy with a rate of 0% (0/180) (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1i) regeneration, implying that 2,4-D alone is suboptimal for callus induction in these varieties. A comparable response pattern was observed in CM334 hypocotyls, with Tc2 yielding the most favorable outcome with a rate of 56.3% (81/144) callus induction (Fig. 1a, i), followed by Tc1 with a rate of 38.9% (56/144) (Fig. 1a, h), whereas the remaining treatments Tc3−Tc5 showed very low effectiveness (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1j–l). In contrast, CM334 roots, like those of Zunla-1, displayed no callus formation across all treatments (Fig. 1a), indicating a lack of regenerative capacity of root explants under the tested conditions. The consistent lack of responsiveness in the roots of both varieties suggests a tissue-specific recalcitrance to the applied hormonal treatments, further emphasizing the importance of explant selection in callus induction protocols.

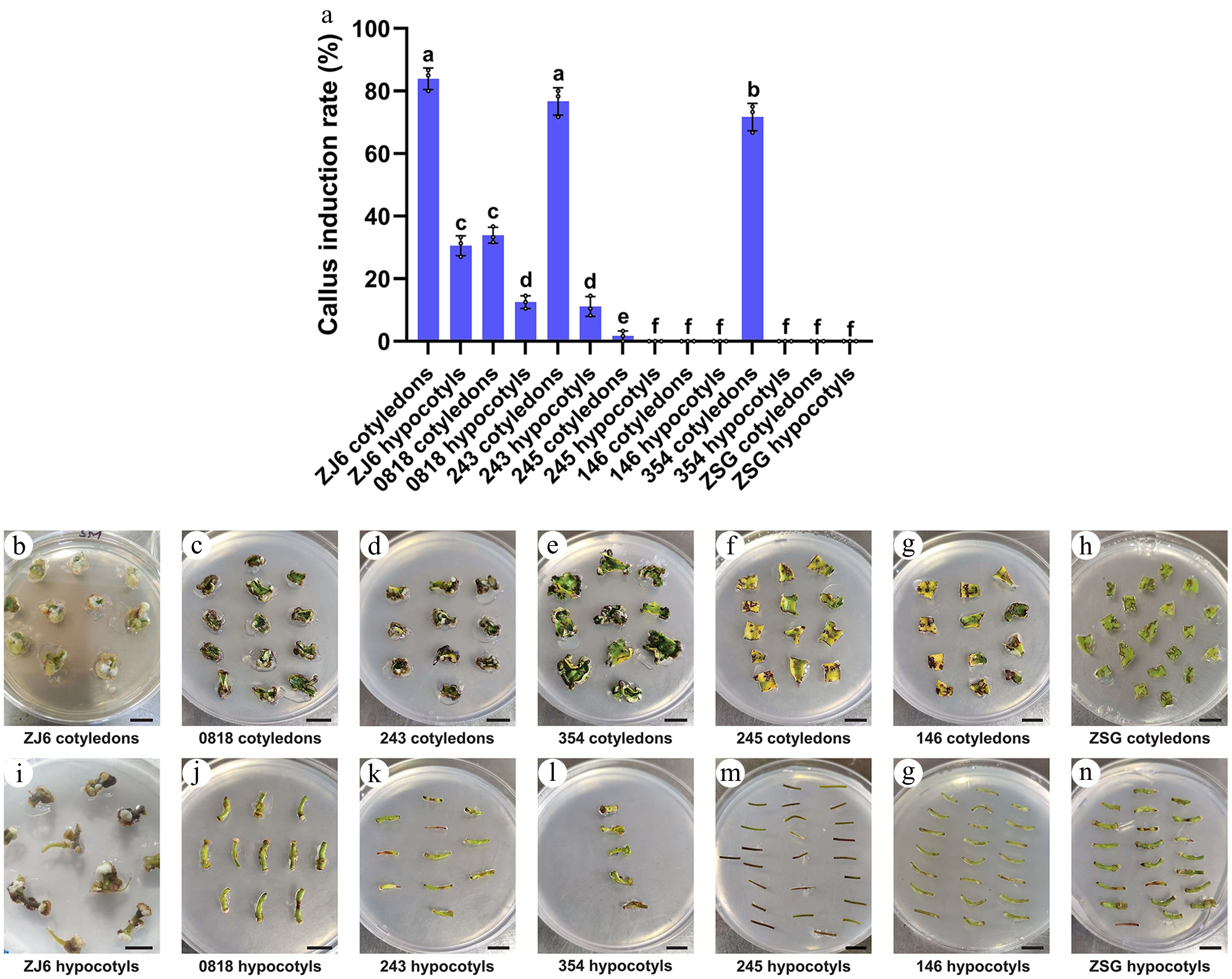

A separate analysis was conducted using the optimized treatment Tc2 identified for Zunla-1 and CM334 (1 mg/L IAA + 1 nM CaREF1) on seven additional varieties, including ZJ6, 0818, 243, 245, 146, 354, and ZSG. Significant differences in callus induction were observed among the explants of these varieties (Fig. 2a). Cotyledons from ZJ6, 243, and 354 exhibited the higher callus induction rates of 83.9% (151/180), 76.7% (138/180) and 71.7% (129/180) (Fig. 2a, b, d, e), significantly outperforming cotyledons from 0818, 245, 146, and ZSG (Fig. 2a, c, f–h). While hypocotyl explants of ZJ6, 0818, and 243 showed minimal callus induction rates of 30.6% (44/144), 12.5% (18/144) and 11.1% (16/144), respectively (Fig. 2a, i–k), hypocotyl explants of 354, 245, 146, and ZSG failed to form callus (Fig. 2a, i–o). Despite successful callus formation in several of these genotypes (ZJ6, 0818, 243, 245, 146, 354, and ZSG), none of the varieties progressed to shoot regeneration under the conditions tested. These results highlight the critical influence of both genetic variation and explant type on callus induction efficiency under specific treatment conditions.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of callus induction rate (%) of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants of different pepper varieties under Tc2. (a) Bar chart illustrating the callus induction rate of different varieties under Tc2 (1 mg/L IAA + 1 nM CaREF1). The annotations above the bars, marked as 'a', 'b', 'c', etc., signify statistical significance (p < 0.05), where bars sharing the same letter indicate no significant difference. (b)–(h) Show the callus formation of cotyledon explants of ZJ6, 0818, 243, 354, 245, 146, and ZSG, respectively. (i)–(o) Show the callus formation of respective varieties in hypocotyl explants. Scale bars indicate 1 cm.

Shoot formation

-

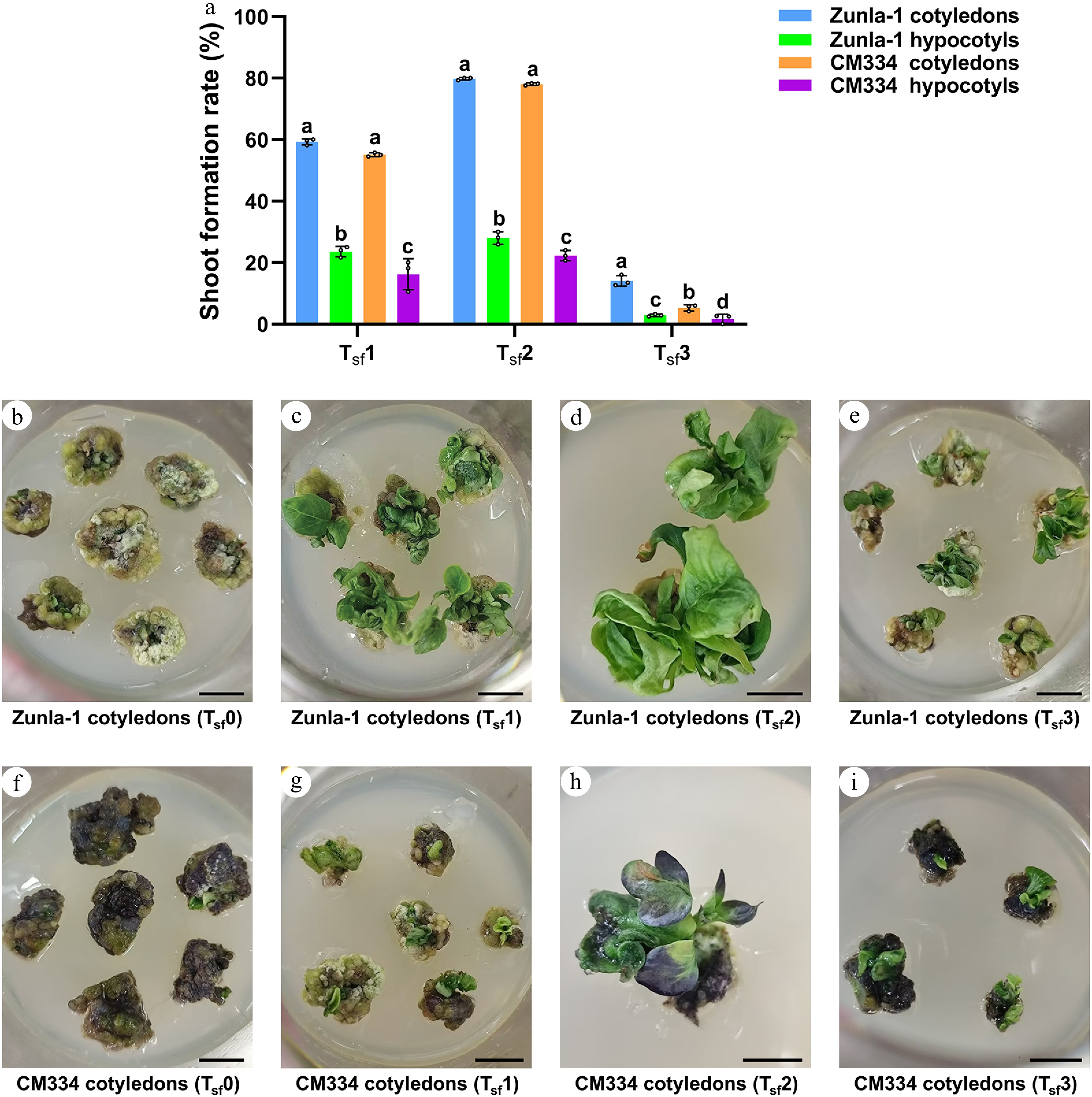

Following the callus induction phase, shoot formation experiments were conducted on both Zunla-1 and CM334. Three treatments were tested to assess their effectiveness: Treatment 1 for shoot formation (Tsf1), composed of 5 mg/L AgNO3, Tsf2 comprised 5 mg/L AgNO3 along with 1 nM CaREF1, Tsf3 contained 10 mg/L AgNO3 along with 1 nM CaREF1, and a control (Tsf0) without AgNO3 and CaREF1. The results indicated that Tsf2 was more effective in promoting shoot formation for both varieties compared to Tsf1 and Tsf3 (Fig. 3a). Notably, the cotyledons of Zunla-1 showed a shoot formation with a rate of 59.3% (99/167) for Tsf1, a rate of 79.8% (138/173) for Tsf2, and a rate of 14.0% (22/157) for Tsf3 (Fig. 3a, c–e), and the hypocotyls of Zunla-1 exhibited a lower shoot formation with a rate of 23.6% (17/72) for Tsf1, a rate of 28.1% (25/89) for Tsf2, and a rate of 2.9% (3/105) for Tsf3 (Fig. 3a). Moreover, cotyledons of CM334 exhibited a shoot formation with a rate of 55.1% (92/167) for Tsf1, a rate of 78.0% (135/173) for Tsf2, and a rate of 5.3% (8/150) for Tsf3 (Fig. 3a, g–i), while the hypocotyls of CM334 exhibited a lower shoot formation with a rate of 16.1% (9/56) for Tsf1, a rate of 22.2% (18/81) for Tsf2, and a rate of 1.9% (2/108) for Tsf3 (Fig. 3a). This indicates that the combination of 5 mg/L AgNO3 and 1 nM CaREF1 Tsf2 is particularly effective in stimulating shoot formation in cotyledons. Additionally, the control Tsf0 experiments without AgNO3 resulted in no shoot formation for both Zunla-1 (Fig. 3b) and CM334 (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of shoot formation rate (%) in Zunla-1 and CM334 under Tsf1, Tsf2, and Tsf3. (a) Bar plot shows shoot formation rate in Zunla-1 and CM334 under Tsf1, Tsf2, and Tsf3. The annotations above the bars, marked as 'a', 'b', 'c', etc., signify statistical significance (p < 0.05), where bars sharing the same letter indicate no significant difference. (b)–(e) Show shoot formation under the effect of different treatments in Zunla-1 under control Tsf0 (without AgNO3); Tsf1: 5 mg/L AgNO3; Tsf2: 5 mg/L AgNO3 + 1 nM CaREF1; Tsf3: 10 mg/L AgNO3 + 1 nM CaREF1 in Zunla-1 cotyledon explants, respectively. (f)–(i) Demonstrates shoot formation under the effect of different treatments in CM334, control Tsf0 (without AgNO3); Tsf1: 5 mg/L AgNO3; Tsf2: 5 mg/L AgNO3 + 1 nM CaREF1; Tsf3: 10 mg/L AgNO3 + 1 nM CaREF1 in CM334 cotyledon explants, respectively. Scale bars indicate 1 cm.

Shoot elongation

-

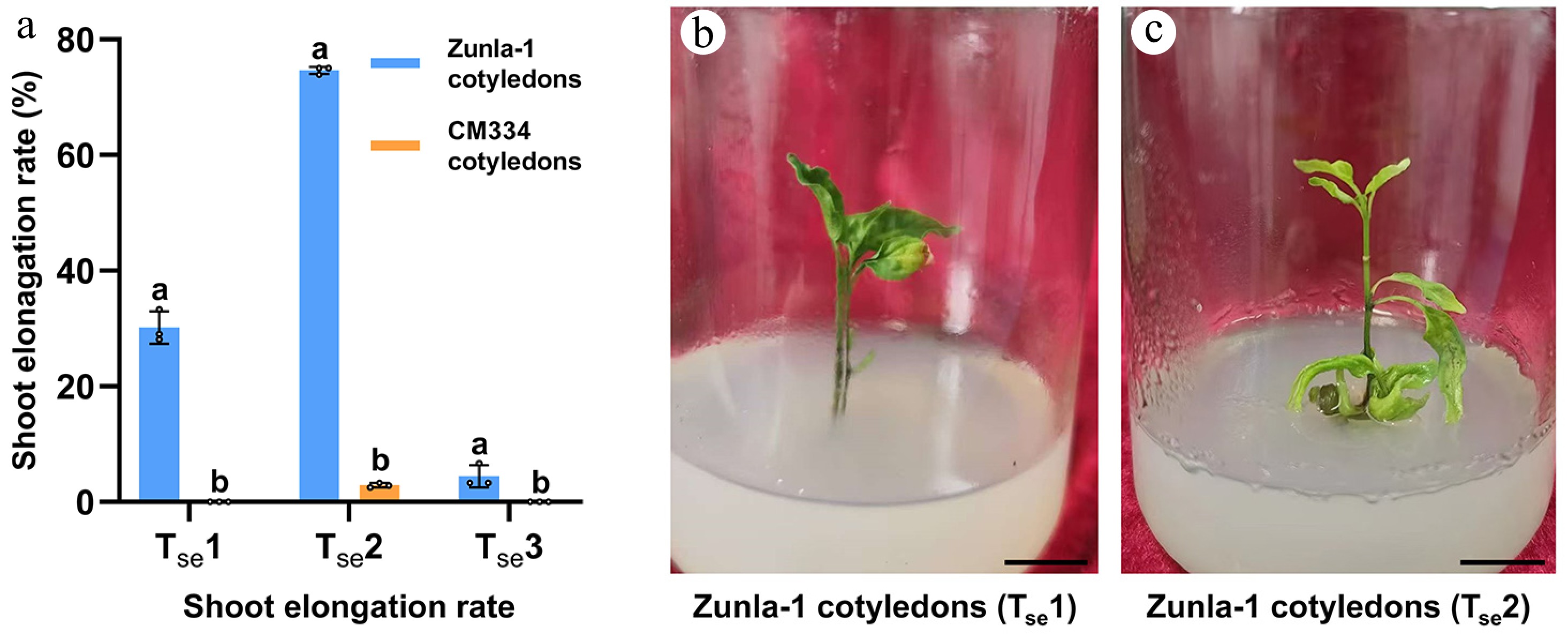

Shoot elongation rates were evaluated for Zunla-1 and CM334, following the initial shoot formation phase. Three distinct treatments were tested: treatment 1 (Tse1) composed of 0.5 mg/L GA3, Tse2 (0.5 mg/L GA3 + 1 nM CaREF1), Tse3 (1 mg/L GA3 + 1 nM CaREF1) and a control (Tse0) without GA3 and CaREF1. Significant variations in response were observed, both between varieties and among treatments. Zunla-1 exhibited the most pronounced shoot elongation under Tse2, with shoot elongation rate of 74.6% (103/138) (Fig. 4a, b) surpassing the effects of both Tse1 and Tse3, where shoot formation rates were 29.6% (24/81) and 4.4% (4/90), respectively (Fig. 4a, c). Notably, within the Zunla-1 variety, cotyledons exhibited a more significant response to Tse2 compared to Tse1 and Tse3 (Fig. 4a), indicating the particular efficacy of the 0.5 mg/L GA3 and 1 nM CaREF1 combination in promoting cotyledon explants for shoot elongation. In contrast, CM334 displayed minimal shoot elongation rates across Tse1 0.0% (0/90), Tse2 2.9% (3/105), and Tse3 0.0% (0/91) (Fig. 4a), suggesting a possible genotype-dependent response. Control treatment (Tse0) conducted without GA3 resulted in a complete lack of shoot elongation, confirming the critical role of GA3. These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing treatment compositions for specific pepper varieties to achieve desired shoot elongation outcomes. The observed disparity in responses between Zunla-1 and CM334 stresses the necessity for variety-specific approaches in pepper regeneration.

Figure 4.

Shoot elongation rates of Zunla-1 and CM334 under different treatments. (a) In the bar chart, the treatments are: Tse1: 0.5 mg/L GA3; Tse2: 0.5 mg/L GA3 + 1 nM CaREF1; Tse3: 1 mg/L GA3 + 1 nM CaREF1. Bars represent mean elongation rates (± SE) for cotyledons and hypocotyls of Zunla-1 and CM334. The annotations above the bars, marked as 'a', 'b', etc., signify statistical significance (p < 0.05). Bars sharing the same letter indicate no significant difference, while those with different letters denote significant differences in shoot elongation among the three treatments. (b)–(c) Images of shoot elongation in Zunla-1 cotyledon explants in Tse1 and Tse2, respectively. Scale bars indicate 1 cm.

Root formation in Zunla-1 pepper cultivar

-

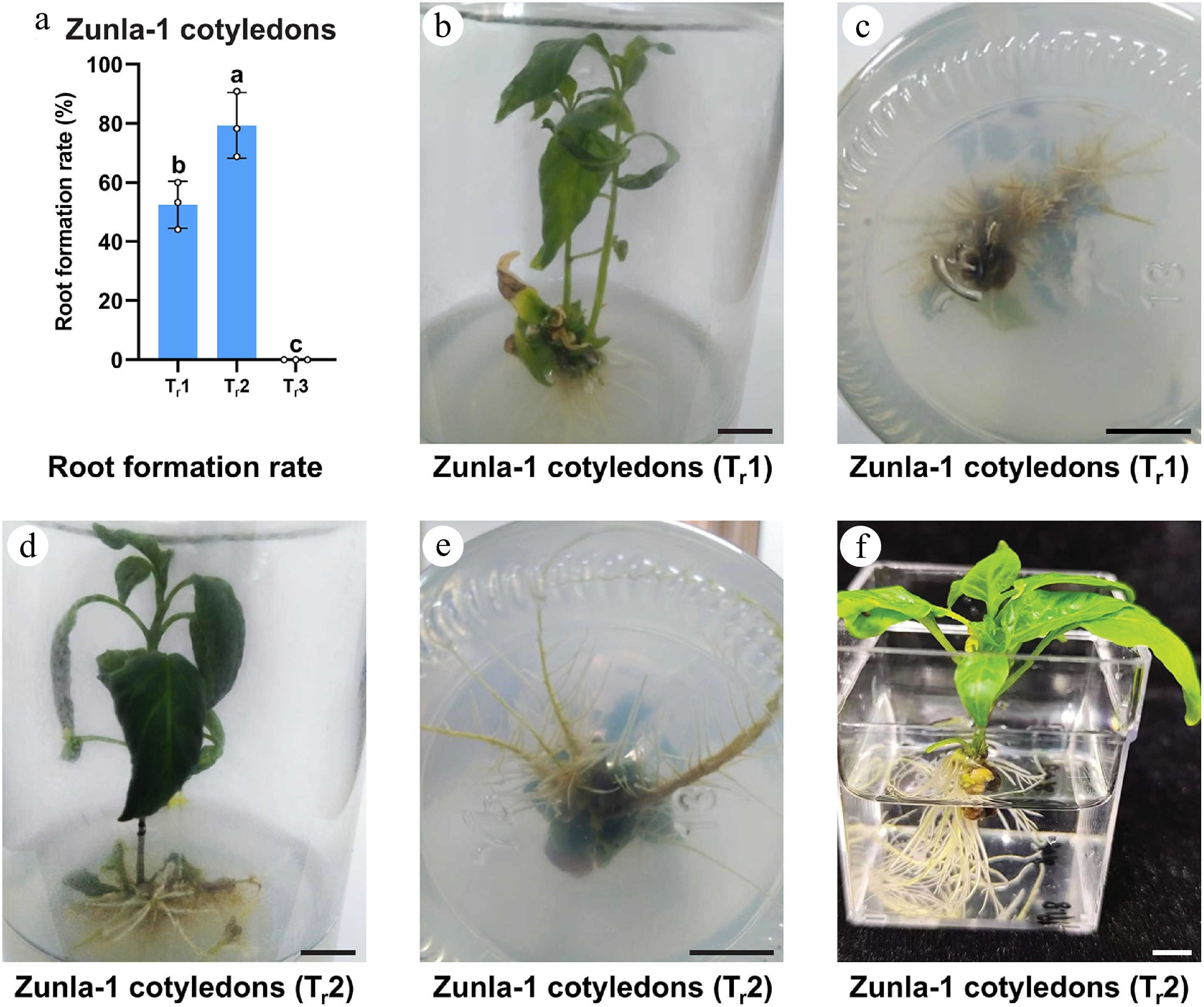

The root formation experiment focused on the Zunla-1 pepper cultivar, which was selected due to its superior shoot elongation performance compared to CM334. Three distinct treatments were evaluated for their effectiveness in promoting root development: treatment 1 (Tr1) consisting of 1 mg/L IBA, Tr2 comprising 1 mg/L IBA combined with 1 nM CaREF1, and Tr3 containing 1 mg/L IAA combined with 1 nM CaREF1 and a control (Tr0) was established to assess root formation without the addition of any hormones. The results revealed significant variations in root formation percentages among the treatments, with Tr2 exhibiting the highest root formation rate of 78.0% (99/127) (Fig. 5a, d–f), followed by Tr1 showing moderate root formation rate of 52.1% (49/94) (Fig. 5a–c), and Tr3 (0.0%, 0/66) failing to produce roots (Fig. 5a). Control group (Tr0) notably has no root formation. The better performance of Tr2 suggests that the effect of CaREF1 promotes root regeneration by enhancing auxin signaling pathways, likely through synergistic interaction with IBA.

Figure 5.

Root formation rate (%) of Zunla-1 cotyledons under different treatments. (a) In the bar chart of root formation rate, Tr1: 1 mg/L IBA; Tr2: 1 mg/L IBA + 1 nM CaREF1; Tr3: 1 mg/L IAA+ 1 nM CaREF1. Bars represent mean elongation rates (± SE) for cotyledon explants. The annotations above the bars, marked as 'a', 'b' signify statistical significance (p < 0.05). (b)–(f) Images of root formation in Zunla-1 in MS medium and water. Scale bars indicate 1 cm.

Regeneration efficiency in Zunla-1 pepper cultivar

-

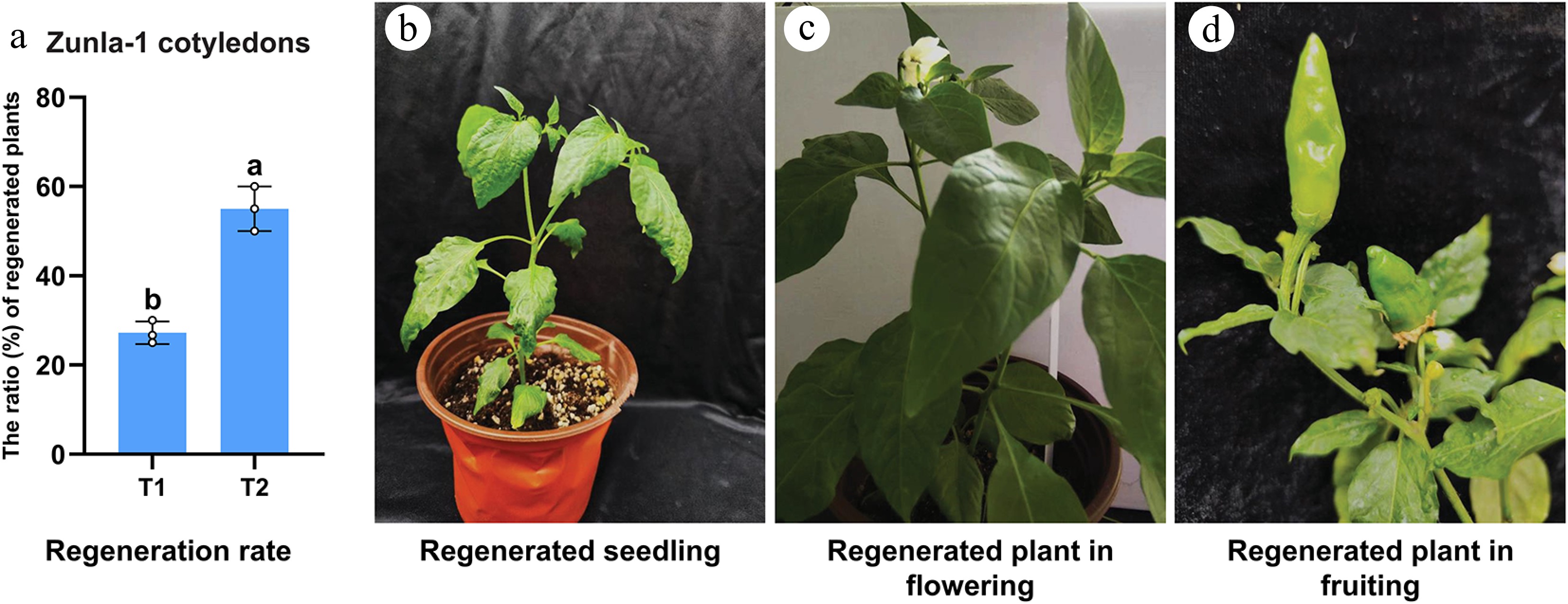

The regeneration efficiency was evaluated for the Zunla-1 pepper cultivar, which has shown promising results in callus formation, shoot formation, and shoot elongation. Two treatments were evaluated for their effectiveness in promoting plant regeneration: T1 (without CaREF1) and T2 (with 1 nM CaREF1). The results revealed a substantial difference in the ratio of regenerated plants between the two treatments. T1 demonstrated the ratio of regenerated plants of 27.2% (49/180) (Fig. 6a), indicating that just over a quarter of the explants successfully regenerated into whole plants. In contrast, T2, which included 1 nM CaREF1, exhibited a markedly higher ratio of regenerated plants of 55.0% (99/180) (Fig. 6a–d), representing more than half of the explants successfully regenerated. This significant improvement in the ratio of regenerated plants, with T2 showing a 28% increase over T1, suggests a synergistic effect between IAA and CaREF1 in promoting plant regeneration in Zunla-1. The enhanced performance of T2 implies that the addition of CaREF1 to the auxin-containing medium substantially augments the regeneration process. These findings have important implications for tissue culture and micropropagation of Zunla-1 pepper plants, as the use of CaREF1 could significantly improve the success rates of plant regeneration protocols.

Figure 6.

The ratio (%) of regenerated plants for Zunla-1 cotyledons. (a) In the bar chart, T1: without CaREF1, T2: T1 + 1 nM CaREF1. Bars represent mean elongation rates (± SE) for cotyledon explants. The annotations above the bars, marked as 'a', 'b' denote statistical significance (p < 0.05). (b)–(d) Images of mature plants of Zunla-1 in pots, as well as plants showing flowering and fruiting in greenhouse conditions.

Microscopic analysis of callus and shoot formation with and without CaREF1

-

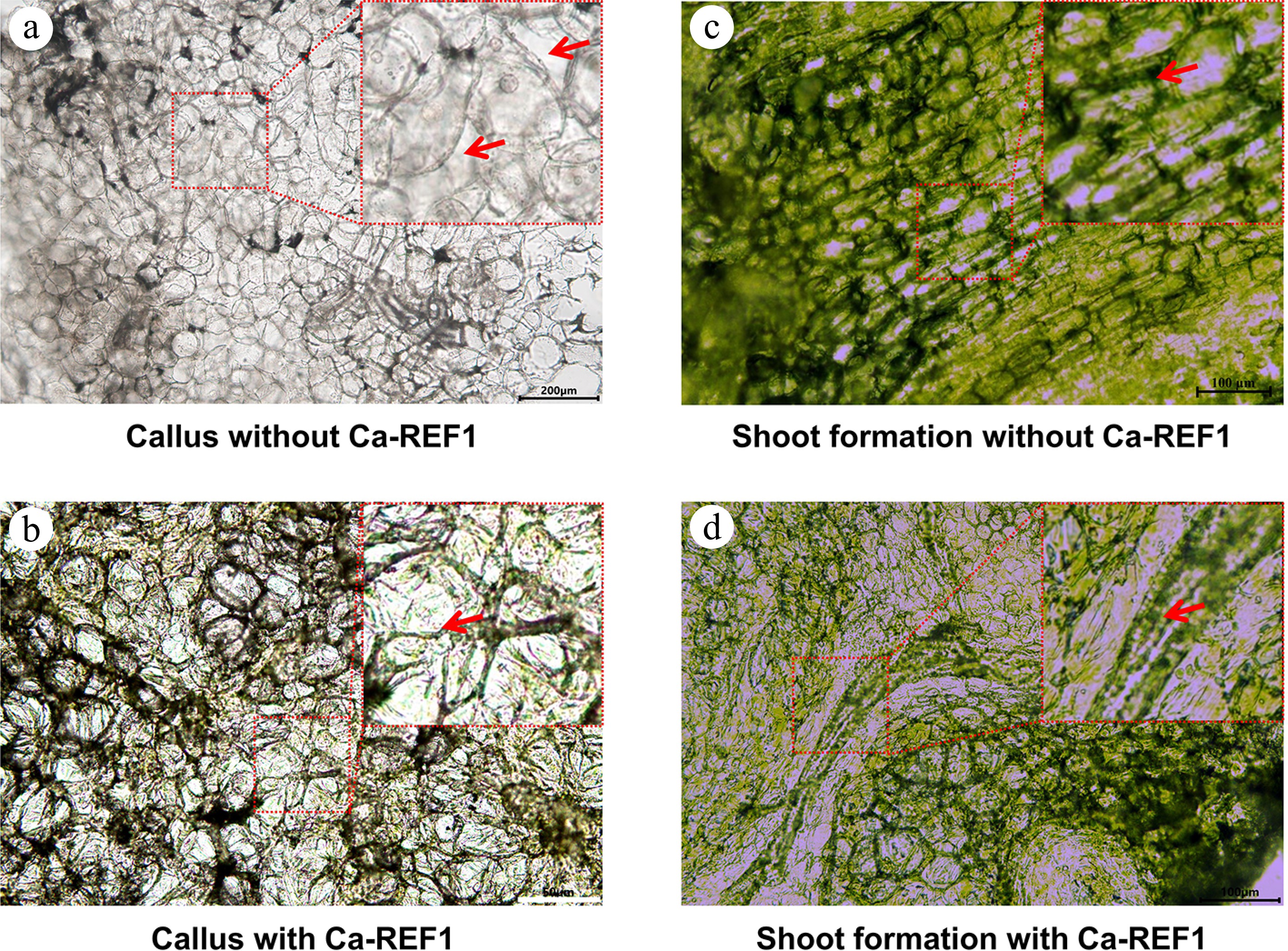

The microscopic analysis of callus and shoot formation revealed distinct differences between explants cultured with and without CaREF1. In the explants cultured without CaREF1, cells were loosely packed, with prominent intercellular spaces and a disorganized structure, indicating poor tissue cohesion (Fig. 7a). In contrast, the explants cultured with CaREF1 exhibited a denser and more compact cellular arrangement, characterized by reduced intercellular spaces and improved tissue organization (Fig. 7b). These observations suggest that the addition of CaREF1 enhances cell proliferation and promotes better tissue cohesion during callus formation, which may improve its regenerative potential.

Figure 7.

Microscopic analysis of callus induction and shoot regeneration in tissue culture media with, and without CaREF1. (a), (b) Microscopic images showing callus induction in tissue culture media without, and with CaREF1 treatment. The enlarged parts display loosely arranged and densely packed cells in callus formation without, and with CaREF1, respectively. The red arrows in (a) indicate the gaps between cells, while the red arrow in (b) indicates the closely connected cells. (c)–(d) Shoot formation in media without, and with CaREF1 treatment. The enlarged parts display fewer compact cells with slower meristematic activity and more compact cells with higher meristematic activity without, and with CaREF1, respectively. The red arrow in (c) indicates these cells are loosely arranged, and lack the necessary conditions for normal division, while the red arrow in (d) indicates dense, smaller, and actively dividing cells. Scale bars: (a) 200 μm; (b) 50 μm; (c), (d) 100 μm.

Similarly, for shoot formation, explants cultured without CaREF1 showed limited evidence of shoot primordia or meristematic regions. The cells remained loosely arranged and lacked the active division necessary for shoot initiation (Fig. 7c). In contrast, explants cultured with CaREF1 displayed distinct cellular differentiation and organization. Localized regions of dense, smaller, actively dividing cells were observed, indicative of meristematic activity and shoot primordia formation (Fig. 7d).

These findings collectively highlight the essential role of CaREF1 in enhancing tissue organization during callus formation and facilitating the transition from undifferentiated callus to organized shoot structures.

-

The present study demonstrates an optimized protocol for efficient regeneration of pepper (C. annuum L.) varieties Zunla-1 and CM334, highlighting the critical roles of genotype, explant specificity, and growth regulator combinations. In callus induction experiments, significant variation among explants and treatments was observed. Treatments containing 1 mg/L IAA alone (Tc1) or combined with 1 nM CaREF1 (Tc2) exhibited superior callus induction rates in cotyledons and hypocotyls compared to 2,4-D (Tc5). Similar genotype-dependent responses were reported previously in pepper species, where cotyledons and hypocotyls showed higher callus induction rates in media supplemented with auxins such as IAA compared to 2,4-D[8,16,36]. Previous studies also highlighted that IAA effectively induced callus formation by activating auxin-responsive gene expression pathways[37,38]. Moreover, observations that root explants exhibited negligible callus induction aligned with earlier findings indicating limited regenerative potential in pepper root explants due to inherent recalcitrance[39].

Notably, while the combination of 1 mg/L IAA and 1 nM CaREF1 (Tc2) also induced callus in certain other varieties (ZJ6, 243, 354), no subsequent shoot formation was observed, suggesting that CaREF1 alone is insufficient to drive complete regeneration in these genotypes (ZJ6, 0818, 243, 245, 146, 354, and ZSG). This further emphasises the genotype-specific hormonal requirements necessary for progression from callus to shoot and root formation.

Furthermore, the enhanced callus induction observed following exogenous application of CaREF1 peptide in this study aligns well with previous findings demonstrating the positive role of REF1 peptide in plant regeneration. REF1 was initially identified as a wound-induced regeneration factor in tomato, where its external application significantly improved regeneration efficiency by activating conserved regeneration signaling pathways[35]. Subsequent studies have confirmed REF1's conserved function across multiple plant species, highlighting its ability to stimulate regenerative responses through receptor-mediated activation of downstream transcriptional regulators such as WIND1 (Wound Induced Dedifferentiation 1)[35,40]. Consistent with these earlier reports, the results suggest that CaREF1 peptide effectively enhances callus induction in pepper explants, potentially by activating similar conserved signaling pathways. This finding provides promising insights into overcoming the inherent recalcitrance typically observed during pepper regeneration and underscores the potential utility of REF1 peptides as valuable tools for improving tissue culture and genetic transformation protocols in recalcitrant crop species.

In shoot formation experiments, the combination of 5 mg/L AgNO3 with CaREF1 (Tsf2) significantly improved shoot regeneration in Zunla-1 and CM334 cotyledons compared to treatments without CaREF1 or higher AgNO3 concentrations. These results corroborate previous studies showing that AgNO3 effectively promotes shoot regeneration frequency by inhibiting ethylene biosynthesis, thus enhancing organogenesis in pepper[41,42]. Likewise, improved shoot regeneration efficiency using AgNO3 has been documented in other recalcitrant species such as cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)[43,44].

Shoot elongation was most effective in Zunla-1 when treated with 0.5 mg/L GA3 combined with CaREF1 (Tse2), whereas CM334 exhibited minimal elongation across all tested treatments. This genotype-specific response is consistent with previous reports emphasizing the differential responsiveness of pepper genotypes to gibberellins during shoot elongation phases[39,45]. Additionally, previous studies on other plant species have shown GA3 as an essential hormone for shoot elongation, further supporting these observations[46,47].

Root formation experiments revealed that IBA combined with CaREF1 (Tr2) significantly enhanced rooting percentages compared to IBA alone or IAA treatments. These results align with earlier findings demonstrating the superior effectiveness of IBA over IAA in stimulating adventitious rooting processes across various plant species, including peppers[48−50]. For instance, exogenous application of IBA markedly improved adventitious root formation in Zanthoxylum beecheyanum stem cuttings through enhanced meristematic cell differentiation and increased soluble sugar accumulation during rooting initiation phases[49]. Similarly, IBA effectively promotes rooting in Magnolia biondii Pamp cuttings by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity, regulating endogenous hormone levels, and accelerating root formation[51]. These studies collectively underscore the importance of selecting appropriate auxins for achieving optimal rooting efficiency.

Regeneration efficiency analysis revealed a substantial improvement from 27.2% without CaREF1 to 55.0% upon supplementation with CaREF1 peptide (Fig. 6a). This significant enhancement highlights a clear synergistic effect between auxin treatment and exogenously applied CaREF1 peptide. Similar improvements in regeneration efficiency have been previously reported with REF1 peptide application in tomato, where REF1 acts as a wound-induced signaling peptide to enhance regeneration responses. While the precise molecular mechanism of CaREF1 in pepper remains undefined, histological observations suggest that CaREF1 enhances cellular reprogramming and tissue organization, which are critical for regeneration. This likely involves modulation of endogenous hormone signalling and stress response pathways that support dedifferentiation and meristem formation during early stages of regeneration. Although characterized REF1 signalling components in tomato provide a useful framework, the specific factors mediating CaREF1 activity in pepper have yet to be identified[35]. Findings confirm that the beneficial role of REF1 peptide, originally identified in tomato, is conserved and effective in pepper (Capsicum spp.) regeneration protocols. The observed enhancement further supports the potential utility of REF1 peptides as valuable tools for overcoming recalcitrance and improving regeneration efficiency in tissue culture systems. A recent study used the RUBY visualization system to screen three efficient gene delivery materials for pepper and combined them with the regeneration-promoting peptide CaREF1 to develop an efficient genetic transformation system. Their experiments showed an average regeneration efficiency (The number of explants producing regenerated shoots/Total number of infected explants × 100%) of 84% ± 7%, with about 5.52 regenerated shoots per explant and a positive transformation rate of 5%[52]. In this study, the regeneration rate was calculated by dividing the number of completely regenerated plants by the total number of explants, reaching a maximum of 55.0% (Fig. 6a). An optimal concentration of REF1 at 1 nM was used, differing from the 10 nM CaREF1 used in the previous study[52]. This may be due to differences in the composition of other compounds in the medium, requiring further studies to clarify.

Microscopic analyses further supported these findings by demonstrating improved cellular organization and differentiation upon addition of CaREF1. Explants cultured with CaREF1 displayed denser cellular arrangements and distinct meristematic regions indicative of active cell division and differentiation into shoot primordia structures (Fig. 7b, d). Such histological improvements are crucial for successful transition from callus to organized shoots and have been similarly documented in previous histological studies on Capsicum regeneration systems[8]. Comparable observations have been reported in studies where exogenous application of cytokinin significantly enhanced tissue cohesion and meristematic activity during shoot organogenesis. For example, cytokinin supplementation has been shown to reorganize the microtubule cytoskeleton, facilitating cell differentiation and the formation of organized shoot primordia structures[53]. Additionally, gibberellins have been shown to stimulate tissue differentiation in callus cultures by promoting vascular development and organized cellular arrangements[54]. These findings highlight the critical role of exogenous hormones in improving cellular organization and differentiation, supporting their use in optimizing tissue culture protocols.

Collectively, the results support previous findings highlighting genotype-specific responses to hormonal treatments during pepper tissue culture and regeneration processes. The optimized protocols presented here provide valuable insights into effective combinations of growth regulators tailored specifically for Zunla-1 and CM334 varieties. These protocols can significantly enhance the efficiency of genetic transformation programs aimed at improving agronomically important traits in peppers. Future research should further explore underlying molecular mechanisms governing genotype-specific responses to growth regulators during regeneration processes to facilitate broader application across diverse pepper genotypes.

-

This study presents an optimized protocol for the efficient regeneration of pepper varieties Zunla-1 and CM334, emphasizing the importance of genotype, explant type, and growth regulator combinations. The use of CaREF1 peptide significantly improved callus induction, shoot formation, and root regeneration, demonstrating its potential to overcome the recalcitrance of pepper in tissue culture. Treatments combining CaREF1 with auxins, cytokinins, and gibberellins showed an enhanced ratio of regenerated plants, increasing from 27.2% to 55.0%. Genotype-specific responses were observed, highlighting the need for tailored protocols. Microscopic analysis confirmed better cellular organization and differentiation with CaREF1, supporting its role in improving regeneration. Although the optimized regeneration protocol significantly improves regeneration efficiency in Zunla-1 and CM334, considerable variation was observed among different pepper varieties. Therefore, the protocol is currently most effective for genotypes with regenerative responsiveness similar to these varieties. Applying it to other pepper genotypes with lower or differing regeneration potential may require further optimization or adjustment to culture conditions. Future work should focus on expanding and optimizing the protocol for a broader range of pepper genotypes, investigating the underlying molecular mechanisms and exploring the broader potential of REF1 peptides in other crop species.

The authors thank Professor Chuanyou Li from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for providing CaREF1, and also thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. This work was funded by the Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. GSCAAS), the Nanfan Special Project, CAAS (Grant Nos. YBXM2522, YBXM2418); the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP) (Grant No. Y2024QC06); the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Youth Scholar (Grant No. 32302557); Basic Research Center, Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. CAAS-BRC-HS-2025-01); the National Key Research and Development program of China (Grant No. 2023YFD1200101); Hainan Seed Industry Laboratory and China National Seed Group (Grant No. B23CQ15KP); the Major Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32494780); China Agriculture Research System (Grant No. CARS-23-A15); the Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. CAAS-ASTIP-IVFCAAS); the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32372712); and Key Laboratory of Biology and Genetic Improvement of Horticultural Crops (Vegetables), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: experiments, writing original draft: Naeem B; partial experiment, writing and reviewing the manuscript: Shams S, Ma L, Zhang Z, Cao Y, Yu H, Su Q; advising the experiment, reviewing and editing the manuscript: Wu H, Wang L; project administration, supervision, and resources: Wu H, Wang L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, further inquiries are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Tables S1 The original data of "Fig. 1a Callus induction rate (%) in Zunla-1 and CM334 under different hormonal treatments".

- Supplementary Tables S2 The original data of "Fig. 2a Comparative analysis of callus induction rate (%) of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants of different pepper varieties under Tc2".

- Supplementary Tables S3 The used data of "Fig. 1a Callus induction rate (%) in Zunla-1 and CM334 under different hormonal treatments".

- Supplementary Tables S4 The used data of "Fig. 2a Comparative analysis of callus induction rate (%) of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants of different pepper varieties under Tc2".

- Supplementary Tables S5 The original data of "Fig. 3a Comparative analysis of shoot formation rate (%) in pepper varieties, Zunla-1 and CM334 under Tsf1, Tsf2 and Tsf3".

- Supplementary Tables S6 The used data of "Fig. 3a Comparative analysis of shoot formation rate (%) in pepper varieties, Zunla-1 and CM334 under Tsf1, Tsf2 and Tsf3".

- Supplementary Tables S7 The original data of "Fig. 4a Shoot elongation rates (%) of Zunla-1 and CM334 under different treatments".

- Supplementary Tables S8 The used data of "Fig. 4a Shoot elongation rates (%) of Zunla-1 and CM334 under different treatments".

- Supplementary Tables S9 The original data of "Fig. 5a Root formation rate (%) of Zunla-1 cotyledon under different treatments".

- Supplementary Tables S10 The used data of "Fig. 5a Root formation rate (%) of Zunla-1 cotyledon under different treatments".

- Supplementary Tables S11 The original data of "Fig. 6a The ratio (%) of regenerated plants for Zunla-1 cotyledons".

- Supplementary Tables S12 The used data of "Fig. 6a The ratio (%) of regenerated plants for Zunla-1 cotyledons".

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Callus induction images of Zunla-1 and CM334 under treatments: Tc3, Tc4, and Tc5.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Naeem B, Shams S, Ma L, Zhang Z, Cao Y, et al. 2025. An optimized regeneration protocol for chili peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) through genotype-specific explant and growth regulator combinations. Seed Biology 4: e012 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0012

An optimized regeneration protocol for chili peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) through genotype-specific explant and growth regulator combinations

- Received: 14 May 2025

- Revised: 26 June 2025

- Accepted: 18 July 2025

- Published online: 11 August 2025

Abstract: Efficient regeneration of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) is essential for genetic transformation and improving agronomic traits. However, the recalcitrant nature of pepper to in vitro manipulation has led to relatively low regeneration efficiencies. This study presents an optimized regeneration protocol for the Zunla-1 variety, focusing on genotype, explant type, and growth regulator combinations. Cotyledon and hypocotyl explants showed superior callus induction with 1 mg/L IAA or 1 nM CaREF1 peptide compared to 2,4-D treatments, while root explants exhibited limited callus formation. Shoot regeneration was most effective with 5 mg/L AgNO3 and 1 nM CaREF1 for cotyledon explants, and shoot elongation was enhanced with GA3 (0.5 mg/L) and CaREF1 (1 nM) in Zunla-1. Rooting efficiency was improved with IBA combined with CaREF1, yielding higher rooting percentages than IBA or IAA alone. Supplementation with CaREF1 peptide increased the overall ratio of regenerated plants from 27.2% to 55.0%. Histological analysis showed improved cellular organization in explants treated with CaREF1, indicating active cell division and differentiation. This study provides an optimized protocol for efficient regeneration of Zunla-1, highlighting the role of CaREF1 in overcoming regeneration recalcitrance.

-

Key words:

- Capsicum annuum /

- Regeneration /

- Explants /

- CaREF1 /

- Zunla-1