-

A diet rich in plant-derived antioxidants can enhance the body's ability to combat reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are linked to various diseases[1]. These antioxidants increase the body's antioxidant capacity and enhance the efficiency of its antioxidant defenses, detoxifying excess ROS, and supporting overall health[2]. A diet rich in natural antioxidants can stimulate the immune system, strengthen cellular defenses against oxidative damage, and reduce risks of disease associated with free radicals, which may contribute to anti-aging effects[3]. The primary antioxidants found in plant-based foods are vitamins, carotenoids, and phenolic compounds[4]. Phenols have a wide range of biological effects, including anti-inflammatory, anti-aging, anti-atherosclerotic, and anti-cancer properties[5]. The French paradox sparked a continuous interest in studying the biological effects of phytochemicals in wine and grape juice, among which syringic and ferulic acids are dominant[6].

Compared to the soluble phenolic acids found in fruits, the phenolic acids in cereal grains are mostly bound to the cell wall with a high antioxidant capacity[7]. While the antioxidant effect of soluble phenolic acids in mice are short-lived at only 2 h, wall-bound (WB) phenolic acids can withstand digestion in the stomach and intestines, reaching the colon where their effects persist for over 24 h[8,9]. Ferulic acid (FA), in particular, is more efficiently absorbed and has a longer circulation time in the bloodstream than other phenolic acids, surpassing that of vitamin C[10]. FA is among the top bioactive compounds taken in Latin American countries[11]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends 300 mg of FA daily for healthy individuals. However, the average daily FA intake often falls below the suggested level, particularly among females in some developed countries[12]. Cereal grains contain more than ten times the FA content of many fruits and vegetables[13], making them a promising target for increasing the phenolic content to benefit human health.

Wheat is one of the oldest and most important cereal crops, providing approximately 20% of the energy and protein that humans require[14]. Wheat grain is rich in protein, starch, fiber, and various bioactive compounds, including phenolics[15]. The phenolic acids in wheat seeds mainly include p-hydroxybenzoic acid, caffeic acid, vanillic acid, p-coumaric acid, and FA, with FA being the dominant[16]. Variations in the wheat kernel metabolome offer new insights and molecular resources for improving wheat's nutritional quality[17]. However, there is a lack of in-depth research on the trend and potential of FA in the context of modern breeding history.

This study analyzed the change and function of phenolic compounds in modern wheat accessions. From a collection of Pakistani and Chinese modern wheat accessions spanning the last century, those with higher (HFA) or lower (LFA) ferulic acid levels were identified. Transcriptome data from developing grains indicated an association between the increased expression of several HXXXD-type acyltransferase genes and FA contents. The correlation between ferulic acid (FA) and antioxidant potential in grains validated the health-promoting potential of FA. The FA advantages in the HFA cultivars remained stable during food processing and are related to a longer lifespan. This work provides in-depth information on candidate genes and germplasm to breed wheat cultivars with higher ferulic acid and antioxidant potential.

-

The chemicals ferulic acid (FA, 99%, CAS# 1135-24-6), ethanol (analytically pure, CAS: 64-17-5), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, analytical pure, CAS: 1310-73-2), methanol (CAS: 67-56-1, UPLC grade), acetic acid (CAS: 64-19-7, analytically pure), diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC, CAS: 1609-47-8, 99%), sodium chloride (NaCl, CAS: 7647-14-5, analytically pure), Triton X-100 (CAS: 9002-93-1, 99%), ethyl acetate (CAS: 141-78-6, analytically pure), disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4, CAS: 7758-79-4, analytical pure), and monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4, CAS: 7778-77-0, analytical pure) were ordered from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Methanol (analytically pure) and acetonitrile (CAN, CAS: 75-05-8) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS, CAS: 30931-67-0), 2,4,6-Tris (2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ, CAS: 6542-67-2), and 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH, CAS: 1898-66-4) are products of Ourchem (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai, China).

Wheat sample preparation and pasta-making

-

The wheat cultivars were grown on the university farms in Jize County, Hebei, China (32°32′22″ N, 118°82′14″ E) or in Bayannaoer City (40°44′35″ N, 107°23′13″ E), Inner Mongolia, following standard procedures. The candidate high FA cultivars were grown at the Liuhe Farm (32°32′22″ N, 118°82′14″ E) of Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, or the Taicang Farm (31°33′50″ N, 121°10′26″ E) of Fudan University, following standard procedures. The grains were collected and the metabolites analyzed using a previously published method[16]. The antioxidant potentials of the whole wheat flour, raw/cooked noodles, steamed buns, and bread were quantified using the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) detoxifying activity, 2,2′-casino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS)-removing activity, or ferric ion-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) methods, respectively, as described previously[18].

Extraction of soluble and wall-bound (WB) phenolic compounds

-

Methanol (80% in water) was added at a ratio of 10 μL/mg of dry powder, then sonicated the mixture in a water bath for 30 min. The samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and 20 μL were injected into an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system for analysis of soluble compounds[19].

The pellets were washed three times with methanol and acetone to remove soluble phenolics. The residue was resuspended in 4N NaOH solution (3 mL) containing p-toluic acid (10 μg, internal standard, IS) and agitated overnight at 37 °C. The samples were adjusted to pH 4.0 with hydrochloric acid (6N), extracted with ethyl acetate (water-saturated), and dried. The dried samples were reconstituted with HPLC-grade methanol at a ratio of 1 μL/mg of dry-weight grain powder and analyzed by UHPLC[20].

Phenolic acid analysis

-

The extracted phenolic compounds were analyzed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity system equipped with a diode array detector (DAD), a Q-TOF mass spectrometer, and an electrospray ionization (ESI) source (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The compounds were separated on a CNW Athena C18-WP HPLC Column (3 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) with HPLC-grade ddH2O and acetonitrile containing 0.1% acetic acid (v/v). Positive ion mode mass spectra were collected using the same parameters as previously reported[19]. FA contents were determined based on an authentic chemical standard and normalized with IS.

Transcriptome analysis

-

Total RNA was extracted from grains at the milky stage of development, directly collected from the field. Each sample type was divided into three groups for PE300 library construction. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 4000, yielding over 6 billion bases per group. These data were analyzed to identify differentially expressed genes, selecting those with a fold change of at least 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR)- adjusted q-value of < 0.05, using RSEM v1.3.1 for quantification[21].

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

-

For gene expression analysis by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), total RNA was extracted from developing grains at the milky stage using TRIzol reagent. Reverse transcription was performed with 3 μg of RNA using a Hifair® ІІ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). qRT-PCR was conducted with 2xHieff® Robust PCR Master Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China), using the wheat actin gene as an endogenous reference. Gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) were used to amplify and quantify the expression levels of target genes, employing the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method for analysis. Each sample was analyzed in at least triplicate.

Growth of fruit flies

-

After the first generation of offspring develops to the adult stage, the fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster, W1118) were collected every 8 h and transferred to culture tubes for up to 3 d. Twenty female flies and five male flies were placed in each culture tube, and ten tubes were collected. The numbers and dates were recorded and placed in the incubator. It was cultivated at room temperature (25 °C or 29 °C), with a photoperiod of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness. The incubator was wiped and disinfected with 75% ethanol every 3 d, along with a change of the culture medium. Each time the food was changed, the number of dead female flies were counted and the number of male flies replenished to keep the number of male flies at five, until all female flies die.

For H2O2 treatment, the first-generation fruit flies were first cultured for 7 d. Under an optical microscope, the female flies were transferred to culture flasks containing 3 mL of 1% Agarose with brushes and incubated in starvation for 24 h. The starved fruit flies were transferred to fruit fly culture tubes containing 5% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for further culture. Ten female flies were placed in each culture tube, and a total of ten tubes were prepared. The number of fruit fly deaths was counted every 12 h until all the fruit flies died.

Statistical analysis

-

Data were analyzed using Student's t-tests in GraphPad Prism 9.5.0, and differences were considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

-

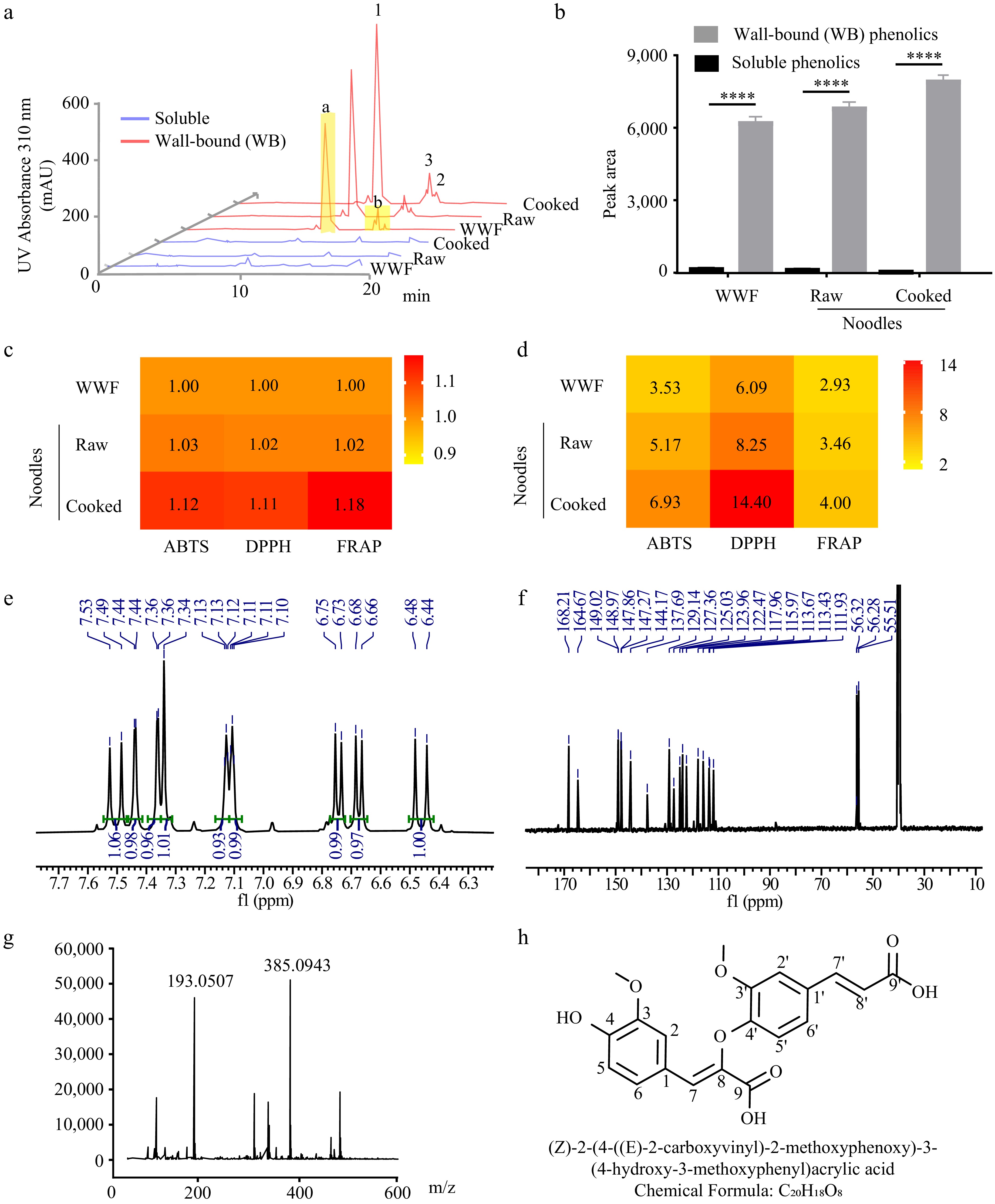

To examine the proportions of soluble and wall-bound phenolics in wheat grains, Jimai22 (JM22), the control in the national variety trials in China's Yellow and Huai River Valleys Facultative Wheat Zone was selected. In whole wheat flour, raw noodles, and cooked noodles of JM22, the amounts of wall-bound phenolic acids were 31, 43, and 81 times higher than those of soluble phenolic acids, accounting for 97%, 98%, and 99% of the total phenolic content, respectively (Fig. 1a). The predominant phenolic acid in the wall-bound phenolic compounds was FA, present in both monomer and dimer forms (Fig. 1b). It is noteworthy that the effective half-time for bound phenolic acids to exert antioxidant effects in mice (≥ 24 h) was significantly longer than that of free phenolic acids (2 h), according to previous studies[8]. Therefore, the wall-bound phenolic acids could substantially contribute to the antioxidant potential of wheat grains.

Figure 1.

The contents and antioxidant potentials of soluble and wall-bound (WB) phenolics in wheat foods. The (a) chromatographs, and (b) contents (n = 4) of phenolic compounds in the soluble and wall-bound phenolics of noodles made from the whole wheat flour (WWF) of Jimai22 (JM22, JM). Fraction a represented a phenolic monomer, and fraction b represented phenolic dimers. Peaks 1, 2, and 3 underwent purification and characterization processes. Raw, raw noodles. Cooked, cooked noodles. The antioxidant potentials of (c) soluble, and (d) wall-bound phenolics in various food forms were assessed using the ABTS, DPPH, and FRAP methods, respectively. Data represent the mean ± standard error. Unpaired student's t-test determined the p-value, * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001. NMR spectroscopy analyses of (e) hydrogen and (f) carbon spectra of Peak 3. The (g) mass spectrum, and (h) predicted structure of Peak 3 as the 8-O-4'-diferulic acid.

The antioxidant activities of wall-bound phenolic acids were higher than those of soluble phenolic acids in the tested food forms. There were 2.53-, 4.17-, and 5.93-fold increases in the WB phenolic acids of whole wheat flour, raw, and cooked noodles, respectively, compared to corresponding soluble parts (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, the DPPH and FRAP antioxidant assays showed multiplicative increases in the antioxidant activity of WB phenolic acids compared to the corresponding soluble fractions of the samples (Fig. 1c). The above data suggest that WB phenolic acids contributed the greatest to the total antioxidant potential in the raw and cooked noodles of whole wheat flour products. As the wall-bound phenolic acids increased during the processing of the flour products, the in vitro antioxidant activities increased accordingly (Fig. 1d).

Next, the dominant peaks in the WB fraction were characterized. An NMR spectroscopy analysis revealed that Peak1 showed hydrogen and carbon spectra similar to those of ferulic acid (Supplementary Fig. S1). The UHPLC-MS data also supported Peak 1 as ferulic acid[22]. The above results agreed with early reports that ferulic acid accounts for more than 67% of wheat phenolic compounds[8].

Peak 3 in fraction b using NMR spectroscopy was then resolved (Supplementary Fig. S2). The hydrogen nucleation integral of the aromatic group of this compound was about two times higher than in ferulic acid (Fig. 1e). The chemical shifts in the carbon spectrum were essentially the same as in ferulic acid (Fig. 1f). The parention mass-to-charge ratio of this compound was 386.0943 (Fig. 1g), corresponding to a dehydrogenated dimer of ferulic acid. According to the number of hydrogen atoms in the aromatic region and the coupling constant between chemical shifts, it was predicted that one of the two ferulic acid monomers was in the cis form, while the other was in the trans form. The cis-ferulic acid monomer is linked to the trans-ferulic acid monomer at position 4' via position 8 (Fig. 1h). The NMR data of this compound are consistent with those of the 8-O-4' ferulic dimer identified in Miscanthus sinensis[23]. Therefore, Peak 3 was identified as 8-O-4'-diferulic acid.

Screening of wheat germplasm accumulating more ferulic acid

-

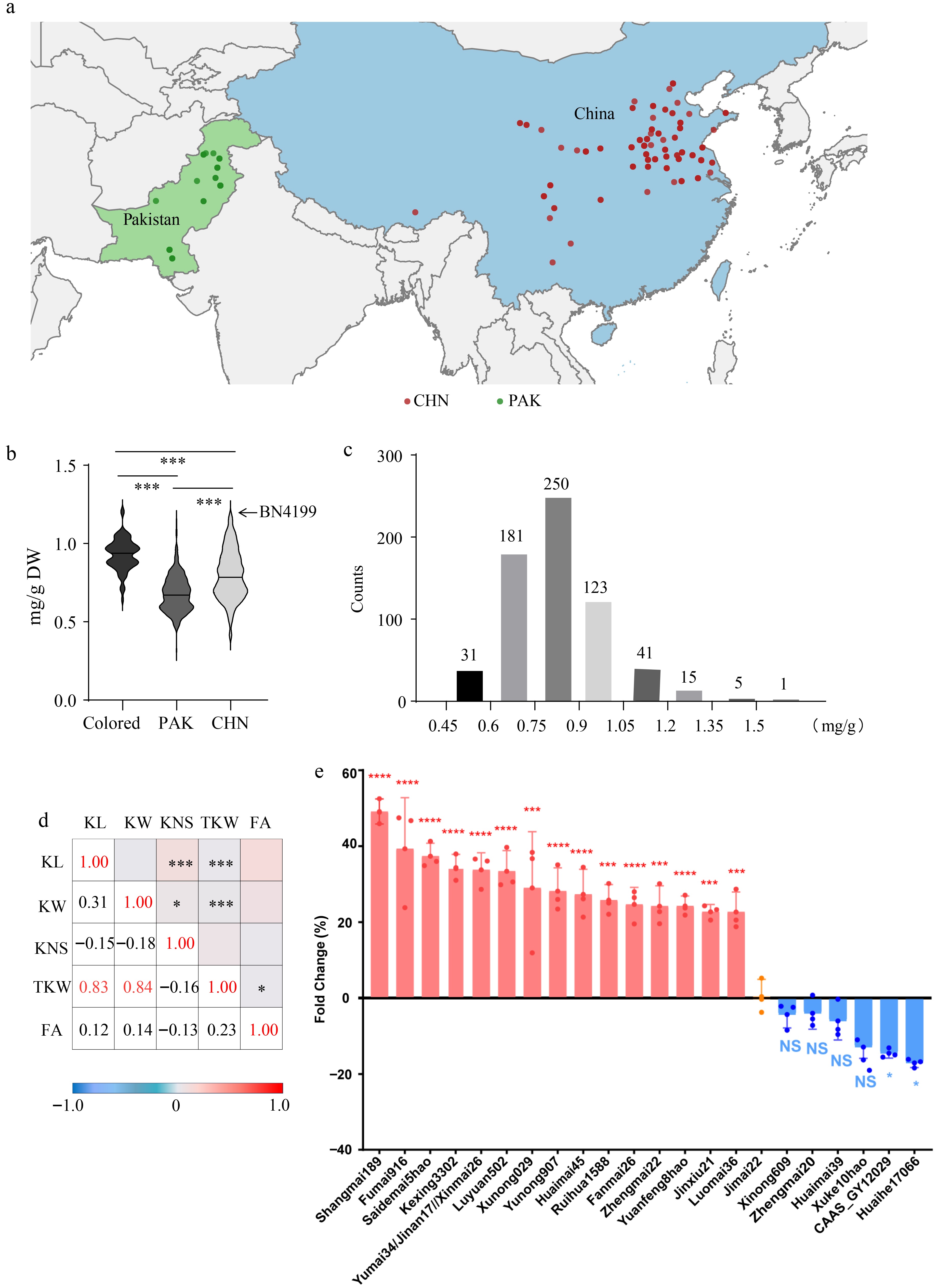

The phenolic profiling of 620 hexaploid wheat germplasms were analyzed, including 100 from Pakistan and 500 from China, as well as 20 colored wheat cultivars (Fig. 2a). Overall, the colored wheat cultivars contained more FA (0.93 mg/g dry weight) than the wheat cultivars from Pakistan (0.68 mg/g DW), or China (0.80 mg/g DW) (Fig. 2b). Moreover, Chinese cultivars contained higher FA than Pakistani ones (Fig. 2b). Several high-FA Chinese cultivars, such as Bainong4199, have a large planting area; therefore, Chinese commercial wheat is expected to contain more FA than Pakistani wheat. The FA contents ranged from 0.41 to 1.56 mg/g in the 620 germplasms, with 10% of them higher than 1 mg/g DW (Fig. 2c). Five out of the 20 (40%) colored wheat cultivars had FA over 1 mg/g, consistent with the fact that colored wheat is widely recognized as nutritious wheat. However, the FA content was higher than 1 mg/g only in one Pakistani wheat cultivar (PUNJAB-96), which is 1% of the total cultivars and was commercialized 30 years ago, suggesting the urgent need and significant potential for FA biofortification in Pakistani wheat cultivars (Fig. 2c). At the population level, the association between FA contents and grain agronomic traits was not significant (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Collection and screening of Pakistani and Chinese modern wheat germplasm with higher ferulic acid contents. (a) The distribution of breeding regions of the germplasms in the wheat population. PAK, Pakistani cultivars. CHN, Chinese cultivars. (b) The comparison of FA contents in wheat germplasms, including both colored and uncolored wheat cultivars from Pakistan and China. BN4199, Bainong4199. (c) The counts of germplasms with different FA contents in the wheat population. (d) The correlation of FA contents with agronomic traits in the wheat population. KL, kernel length. KW, kernel width. KNS, kernel number per spike. TKW, 1,000 kernel weight. FA, ferulic acid content. (e) The FA contents in some selected high-ferulic acid (HFA) or low-ferulic acid (LFA) cultivars. n = 3.

To verify the stability of the above screening, over 400 Chinese cultivars in South China were subsequently harvested. The mean FA content in the population is 0.79 mg/g, which is very close to the value obtained in a screening study in Northern China. The ferulic acid content of Jimai22 (JM22) was 0.821 mg/g, close to the average of the sample set. JM22 is the comparison control in China's Yellow and Huai River Valleys Facultative Wheat Zone wheat breeding tests. Therefore, JM22 could work as an ideal control for subsequent experiments. High-ferulic acid (HFA) material and low-ferulic acid (LFA) cultivars wre further planted for another year at the Fudan University farm in Taicang and the Liuhe Farm in Jiangsu Province, South China, and identified HFA or LFA cultivars with stable changes (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. S3).

Transcriptome analysis of developing grains with different FA content

-

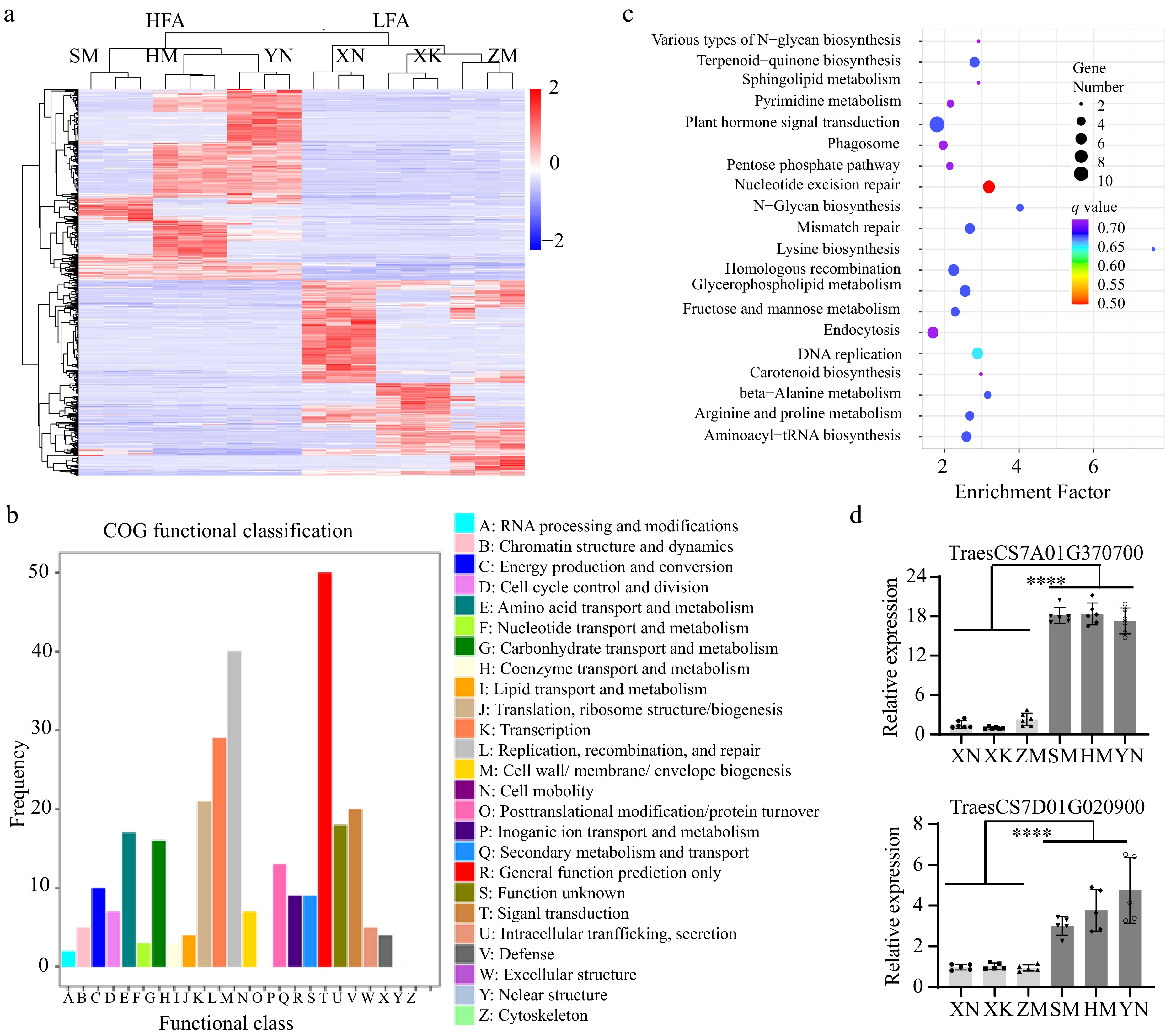

To ascertain the change of transcriptomic patterns beneath the variations in FA content, transcriptomes of three HFA and three LFA cultivars' grains at the grain-filling stage in the field of the Liuhe Farm in Jiangsu Province were compared. A comparison of the two groups revealed 583 higher-differentially expressed genes (DEGs), and 599 lower DEGs in the HFA samples, respectively (Fig. 3a). In the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) of proteins functional classification, replication, recombination, and repair (40 DEGs), transcription (29 DEGs), and translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (21 DEGs) were the top three categories (Fig. 3b). Among the metabolic pathways, amino acid transport and metabolism and carbohydrate transport and metabolism were the top two pathways (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. S4). Among the upregulated DEGs in HFA samples, there are several genes involved in FA biosynthesis, including three hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyl transferase (TraesCS6A01G375300, Log2 fold change = 2.18; TraesCS5A01G222900, 5.52; TraesCSU01G078700, 4.98), which catalyze the total metabolism flux toward the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway.

Figure 3.

The transcriptomes of developing grains in HFA and LFA. (a) The heat map shows differentially expressed genes (DEGs) during the grain-filling stage in HFA and LFA cultivars. (b) The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) of proteins encoded by the DEGs. (c) The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) metabolism pathway analysis of DEGs. (d) The RT-qPCR analyses of the annotated HXXXD-type acyltransferase genes in the grain-filling stage of HFA or LFA varieties. n = 6.

The esterification of polysaccharides by feruloyl-CoA was a combined result of the availability of substrates and the acyl transfer reaction[24]. To explore the potential mechanism underlying FA accumulation in HFA grains, we the DEGs were reannotated using the genome annotation of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Fortunately, two genes encoding HXXXD-type transferase were expressed significantly higher in the HFA samples than in the LFA ones. Their expression levels in the HFA grains were higher, as determined by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analyses (Fig. 3d). In early reports, HXXXD-type transferases were shown to catalyze the feruloyl group transfer reaction from feruloyl-CoA to the cell wall[20,25,26]. It was predicted that the high expression of HXXXD-type transferases above could be associated with the accumulation of FA in wheat grains.

The changes in FA content during the food cooking processes

-

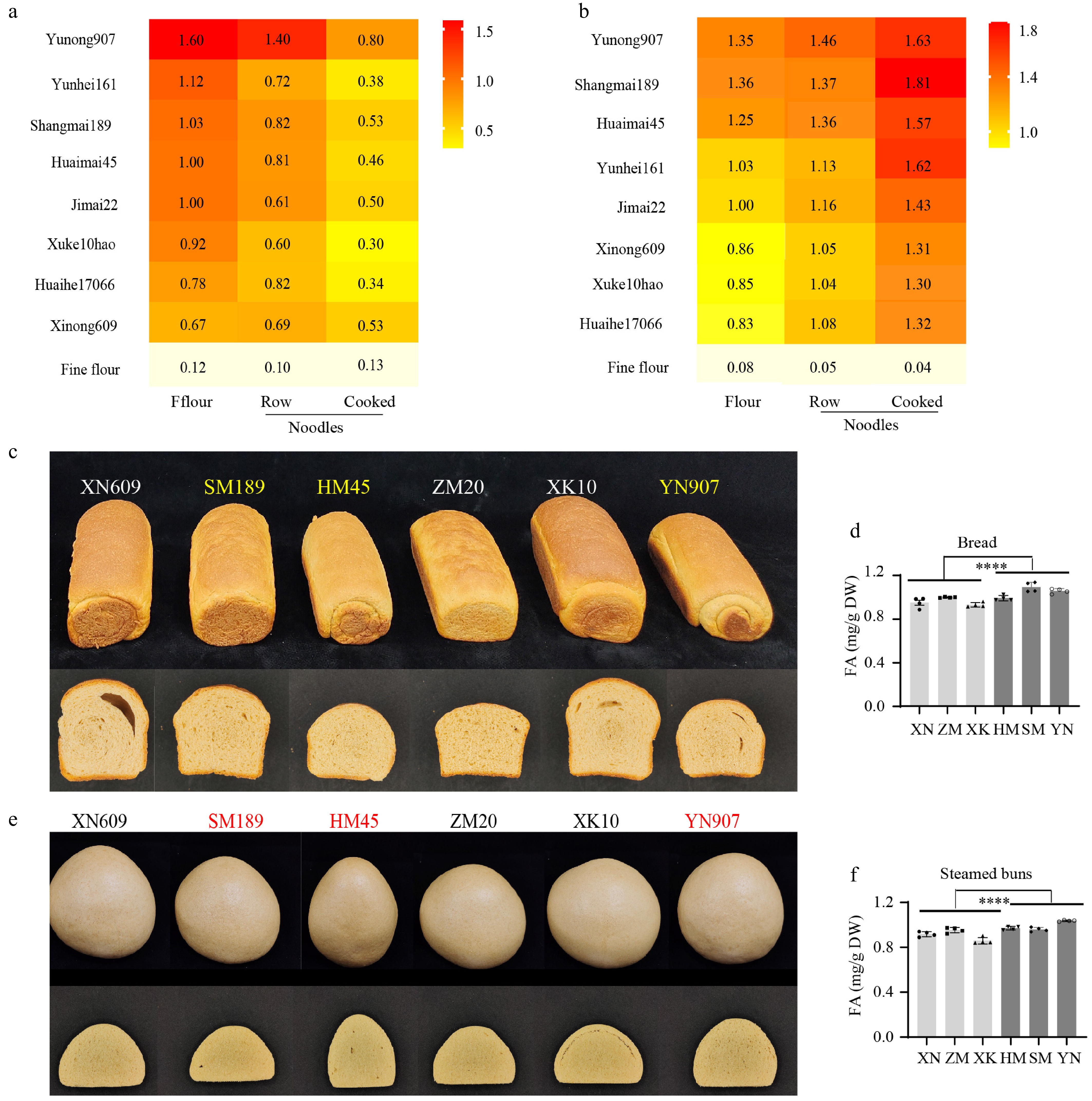

Different food processing procedures could affect the amount and stability of phenolic compounds. To explore the changes in phenolics during food processing, raw and cooked noodles were prepared using whole wheat flour from three HFA cultivars, three LFA cultivars, JM22, and a commercial black wheat variety (Yunhei 161). The whole wheat flour of Yunhei 161 contained 12% higher phenolic acids than that of the control in the soluble fraction (Fig. 4a), but not higher in the wall-bound fraction (Fig. 4b). In whole wheat flour, FA content in the HFA cultivars (Yunong907, Shangmai189, and Huaimai45) increased by 35%, 36%, and 25%, respectively, compared with JM22. In contrast, the LFA cultivars (Xinong609, Xuke10Hao, and Huaihe17066) showed decreases of 14%, 15%, and 17%, respectively (Fig. 4b). In raw noodles, FA content in HFA cultivars were 14% to 25% higher than JM22, and those in LFA samples were 7% to 11% lower than JM22 (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Changes in FA content during food processing. The (a) soluble, and (b) wall-bound (WB) phenolic compounds in different forms of foods made from HFA, LFA, black wheat (Yunhei161), JM22, and refined flour. Raw, raw noodles. Cooked, cooked noodles. (c) The exterior (up) and interior (bottom) views of bread made from HFA or LFA cultivars. (d) The change of FA contents during the bread baking of HFA or LFA varieties. (e) The exterior (up) and interior (bottom) views of steamed buns made from HFA or LFA varieties. (f) The change in FA contents during the processing of steamed buns made with whole wheat flours of HFA or LFA cultivars.

To investigate differences in FA content between foods during various food preparation processes, whole-wheat flour from HFA and LFA cultivars was used to bake bread. There was no clear trend in bread volume or crumb structure amongst HFA and LFA samples (Fig. 4c), suggesting no clear correlation between bread volumes and FA content. Interestingly, among the breads with high volumes, the top of the bread made with Shangmai189 (SM, HFA) was golden, while those with Xinong609 (XN, LFA) and Xuke10 (XK, LFA) were dark brown (Fig. 4c). Among the breads with lower volumes, the top of Huaimai45 (HM, HFA) and Yunong907 (YN, HFA) was golden and smooth, while that of Zhengmai20 (ZM, LFA) was uneven and darker (Fig. 4c). The FA was significantly higher in bread made with HFA flour (Fig. 4d). The steamed buns had no clear trend in appearance, volume, or crumb structure amongst HFA and LFA samples (Fig. 4e). The FA was primarily retained in both foods and was significantly higher in steamed buns made with HFA flour (Fig. 4f). Therefore, the FA content and antioxidant potential in whole flour could positively correlate with the ability of bread to prevent burning during baking.

Effect of foods with different FA content on the life span of the fruit fly

-

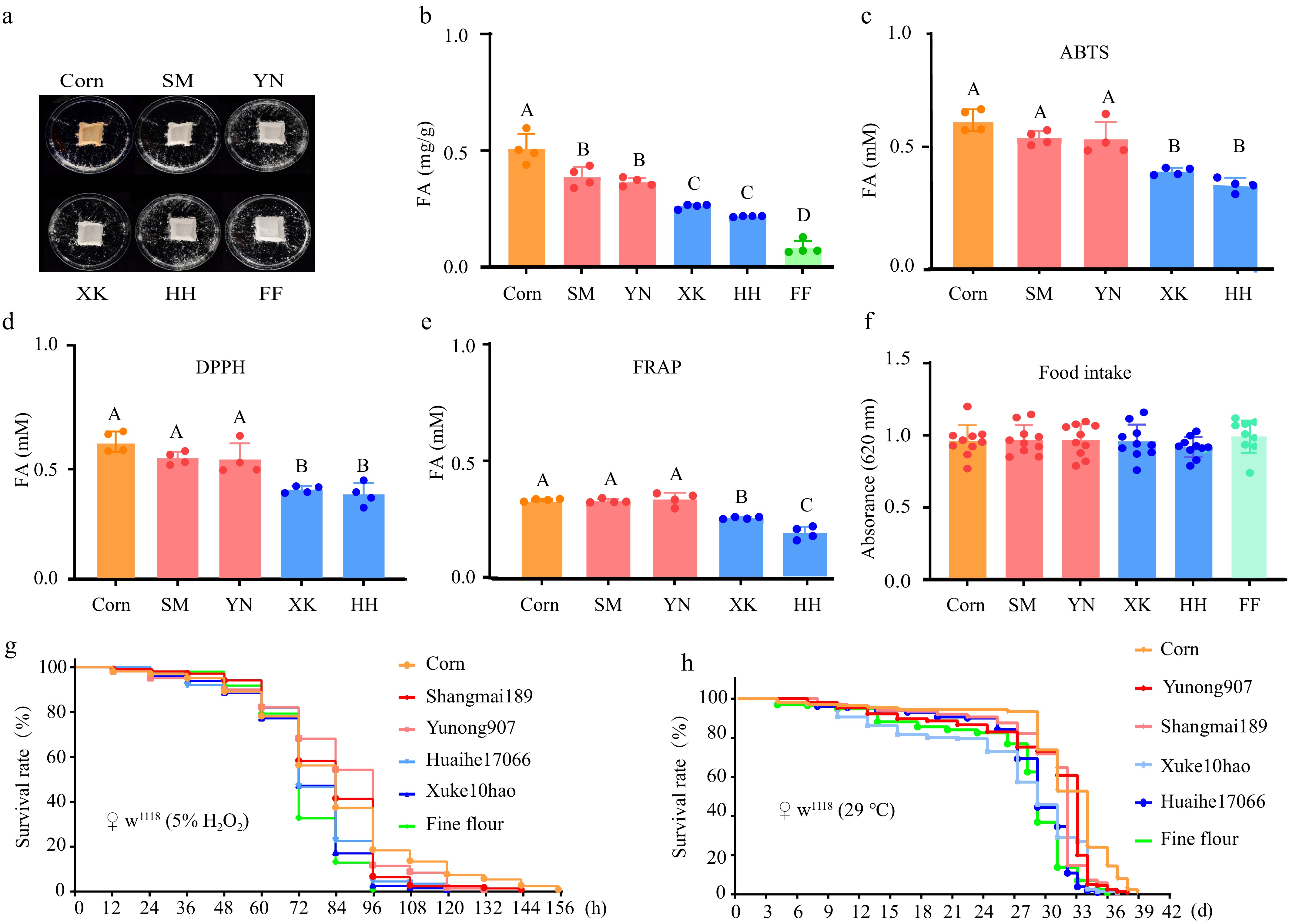

Oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions are fundamental biological processes and often lead to cellular and tissue damage[27]. Ferulic acid is widely recognized for its antioxidant properties, apoptosis-inhibiting activities, and health-promoting functions[28]. To investigate the antioxidant effects of the above foods on animals, the fruit fly food was prepared using the whole flours of Shangmai189 (SM, HFA), Yunong907 (YN, HFA), Xuke10 (XK, LFA), and Huaihe17066 (HH, LFA) (Fig. 5a). Corn flour contains a high amount of FA and works as the positive control with high antioxidant potential (Fig. 5b−e). Commercial fine flour of wheat, on the other hand, contains a low amount of FA and serves as the negative control with low antioxidant potential (Fig. 5b−e). There was no significant difference in the intake of foods fed the above foods with different FA contents compared to wild-type (w1118) female fruit flies (Fig. 5f).

Figure 5.

The lifespans of fruit flies on food made with HFA or LFA cultivars. (a) The appearance of foods made with whole-wheat flour from HFA (SM, YN) of LFA (XK, HH) cultivars. Corn is a food made with corn flour and contains the highest content of FA in tested samples, serving as an HFA control. FF is a fine flour from Jimai22 with a very low FA content, serving as an LFA control. The (b) FA contents and antioxidant potentials (c), ABTS; (d) DPPH; and (e) FRAP of the foods. n = 4. (f) The amount of food taken by fruit flies. Note that there is no significant difference between the foods. n = 10. (g) The lifespan of female fruit flies on different foods in acute stress induced by 5% H2O2, grown at RT. Note that the FF has low FA, and the corresponding group (green line) has the shortest lifespan. (h) The lifespan of female fruit flies on different foods in chronic stress caused by heat treatment (29 °C). Note that the corn flour with the highest FA content has the longest lifespan in its group (orange line).

To assess the protective effect of FA on animal health, 5% (v/v) H2O2 was first added to the above foods to simulate an acute oxidative stress. The protective effects associated with FA differences in food were monitored over the life spans of healthy fruit flies. The median survival times of flies on Yunong907 (YN, HFA) and Shangmai189 (SM, HFA) were 84 and 96 h, respectively. The above lifespans were 34% and 17% longer than those of 72 h on Xuke10 (XK, LFA), and Huaihe17066 (HH, LFA) (Fig. 5g). There was no statistical difference between Yunong907 (YN, HFA) and Shangmai189 (SM, HFA) from corn flour (84 h) (Fig. 5g). It is notable that the longest survival time (156 h) was observed in samples fed with corn flour (the orange line), which contains the highest FA content. On the contrary, the fine-flour-fed samples (the green line) showed the shortest average survival time, consistent with the trend in FA content among the samples.

In the context of global warming, temperature fluctuations are expected to be a threat to human health. High-temperature environments can induce ROS accumulation and cellular oxidation[29]. The lifespan of female fruit flies in a high-temperature environment (29 °C) were analyzed to simulate the chronic stress of prolonged duration. The maximum survival time of fruit flies was the longest in the cornmeal medium (40 d) and the shortest in the fine powder medium (36 d) (Fig. 5h). The median survival times of flies fed the Yunong 907 whole grain powder medium (34 d), and of the Shangmai 189 whole grain powder medium (33 d) were longer by 33% and 11%, respectively, compared with those fed with the LFA whole grain powder medium (30 d), or the fine powder medium (30 d, Fig. 5h). Therefore, the above data support a positive correlation between FA content and antioxidant potential, which is further associated with a longer lifespan in the model animal, the fruit fly.

-

In this study, the contents and trends of phenolic acids in wheat germplasm resources collected from Pakistan and China over the past century were investigated. The stability of ferulic acid during food processing suggests that it can retain its biological function after consumption. The association of HFA with a longer lifespan in model animals indicates the potential of ferulate-enriched wheat cultivars and the corresponding foods to promote consumer health.

The examination of wall-bound phenolic acids with soluble phenolics in wheat grains demonstrated that FA is the dominant phytochemical in wheat grains, consistent with previous reports[19]. The levels of free phenolic acids decreased significantly during cooking (Fig. 4), reflecting their unstable decomposition or oxidation at high temperatures. Conversely, in the WB phenolic acids analysis, FA content tended to increase during cooking (Figs. 1, 4). The increased FA content might result from the destruction of the cell wall by high-temperature steam, which could promote the release of FA and increase its bioavailability[23]. Another possible reason is that thermal degradation of polyphenols into simple phenolic acids occurs during the cooking of whole wheat flour, thereby producing by-products in the form of FA[30].

The investigation of FA content in wheat cultivars collected from Pakistan and China suggested that some model Chinese cultivars have higher FA levels. Nevertheless, the selection of HFA cultivars in Pakistan lags. There is a negative correlation between chickpeas seed weight and phenolic acid content[31]. However, the HFA cultivar Bainong4199 has a thousand-kernel weight of 44 g and belongs to the large-kernel category. The analysis of FA contents with TKW showed a correlation of 0.228, which is not significant. This data agrees with a recent publication that found no significant correlation between ferulic acid concentration and kernel weight in an analysis of 233 diverse maize inbred lines[32]. Therefore, biofortification of FA in future wheat breeding programs is achievable and promising.

The fruit fly is a model animal widely used to study the effect of food intake on lifespan[33]. The test of 12 Chinese herbal medicines, which contained strong antioxidant components, showed that two herbal medicines could extend lifespan, but only in females[34]. A wheat germ-rich diet increased the activities of antioxidant enzymes in Drosophila but did not significantly change the mtDNA damage or mtDNA copy number[35]. Wheat endosperm-derived semolina is a rich source of carbohydrates and protein, and the semolina-jaggery (SJ) diet significantly extended the lifespan of both male and female flies[36]. However, the phytochemicals responsible for the above benefit remain unknown. The anthocyanin-containing wheat bran extract (+AWBE) displayed higher radical scavenging and membrane protective activity (AAPH oxidative hemolysis model) than the -AWBE. Nevertheless, both wheat bran extracts showed a longer lifespan than the control food, indicating that phytochemicals other than anthocyanins in wheat bran contribute to prolonging lifespan[37]. The current study demonstrated that common HFA wheat foods significantly extended the lifespan of fruit flies. Therefore, FA has a high potential for promoting health. Hence, it is a promising biofortification target, alongside anthocyanins, for future wheat breeding programs.

Antioxidant activity is widely associated with pharmacological effects, including cellular protection and lifespan extension. Phenolic compounds, resveratrol and trans-2,3,5,4'-tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-glucoside (TSG), target voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) to regulate intracellular Ca2+ level, ROS homeostasis, and, therefore, cell apoptosis[38]. FA is among the natural phenolic compounds with the highest antioxidant activities[39]. FA application increases progesterone levels but decreases estradiol levels in pregnant mice[40]. The fact that HFA foods are related to longer lifespan in female fruit flies is consistent with the ROS scavenging activities of FA (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, the advantage of HFA food is consistent with the results of Chinese herbal extracts[34]. In an earlier report, the health-promoting benefits of wheat flavonoid extracts were detected in the female fruit flies[19]. It is hypothesized that hormone and other biological differences between the sexes may contribute to the above differences. An investigation of beverage intake discovered differential FA absorption efficiencies between males and females[41]. Therefore, further screening or breeding cultivars with higher FA content than the current tested cultivars is necessary to determine whether they offer benefits for males.

-

The isolation of HFA varieties from modern wheat accessions paved the way for a significant step to boost the antioxidant potential of wheat products. The preliminary analysis of the model animal feeding experiment revealed a positive relationship between grain FA contents and the lifespan of fruit flies in acute (5% H2O2) and chronic high-temperature (29 °C) stress conditions. This work provided information on the phenolic acid composition of raw and cooked foods, as well as promising germplasm resources and gene targets for future breeding programs aimed at developing functional wheat varieties that benefit human health.

This study was supported by the National Key Research Development Program of China (2023YFF1000600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32401841), the Pinduoduo-China Agricultural University Research Fund (PC2023B02013), by Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2025RC052), and the Crop Science First-class Subject Open Project Henan Institute of Science and Technology (2024XK008). We are grateful to Jiasheng Wang at Fudan University for his valuable assistance with compound purification and analysis.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Gou JY; data curation: Wang ML, Jazib J, Gong YL, Zhang CX, Ren RS, Yu JZ, Li QQ, Zhou SY, Hu DL, Liu GY, Liu QF, Zhang Z, Shi XT, Wei WX, Shi SS, Song GC; resources: Ren RS, Zhang PP, Ru Z, Chen X, Rehman SU, Qayyum H, Rasheed A; writing−original draft: Wang ML, Gou JY; writing−review and editing: Gou JY, Zhang PP, Rasheed A, Baloch FS; funding acquisition: Gou JY, Wang ML, Liu GY, Chen X, Ru Z, Zhang PP. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data are contained within this manuscript or are available from the authors.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Meng-Lu Wang, Jazib Javed, Yi-Lin Gong, Chen-Xi Zhang

- Supplementary Table S1 The primers used for PCR in this study.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The MR spectroscopy and structure of Peak 1 are consistent with ferulic acid.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The purification of the dominant WB phenolic component in wheat grains.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Comparison of ferulic acid contents in cultivars from farms in Taicang or Liuhe in 2022.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 The Gene Ontology (GO)analysis of enrichments of DEGs in biological (up) and cellular (down) processes.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang ML, Javed J, Gong YL, Zhang CX, Ren RS, et al. 2026. Increasing food antioxidant potential by screening ferulate-enriched wheat germplasm. Seed Biology 5: e003 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0027

Increasing food antioxidant potential by screening ferulate-enriched wheat germplasm

- Received: 19 August 2025

- Revised: 28 October 2025

- Accepted: 04 November 2025

- Published online: 28 January 2026

Abstract: Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grain is a treasure trove of bioactive phenolic compounds, including soluble and wall-bound (WB) phenolic compounds. Ferulic acid (FA) is dominant in WB phenolics and a standout due to its potent antioxidant capabilities. However, dietary FA often falls short of recommended intakes. This study investigated the content, trend, regulation, and potential of FA in a wheat germplasm collection. A large-scale screening of over 600 wheat germplasms from Pakistan and China revealed that some modern Chinese cultivars have high FA contents comparable to those of colored wheat. In contrast, Pakistani wheat cultivars have ample room for further increases in FA content. Transcriptome analyses pointed to a correlation between high expression levels of HXXXD-type acyl transferase genes and FA contents in developing grains. FA remained stable through various food processing methods, including the production of noodles, bread, and steamed buns. Moreover, fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) fed HFA foods had a longer lifespan than those fed LFA in both acute oxidative stress (5% H2O2) and chronic high-temperature (29 °C) stress. Therefore, biofortification of FA in wheat grains has a significant potential for health and can be achieved using the identified wheat germplasms. The above results provide candidate genes, promising parental lines, and a theoretical basis for future wheat breeding aimed at enhancing the antioxidant and health-promoting properties of wheat.

-

Key words:

- Wheat /

- Ferulic acid /

- Antioxidant potential