-

Modernization has led us to extreme dependency on artificial sources for our daily requirements including food, medicine, clothing, and many more, but we are forgetting about nature itself, which is a great source of all the necessary components for life. Nature is filled with numerous species of mushrooms, which are recognized by their unique body structures. Some of these mushrooms are edible, some are not, some are wild, and some can be cultivated; some are toxic; others contain pharmaceutically important bio-active components. Since the onset of civilization, humans have been searching for wild mushrooms and their cultivation procedure[1], and the inclusion of fruiting bodies in the regular diet has been evident since 3000 BC[2].

Over the last few decades, mushrooms have primarily been consumed for their unique flavours and tastes[3]. However, as time has progressed, scientific investigations have uncovered the remarkable medicinal properties of these macro-fungi. Thus, the reason behind the cultivation of mushrooms has also become vast, and many new research opportunities will come along with this. Since ancient times, studies have been conducted to understand their medicinal values, nutritional importance, immune-modulator components, and their chemistry. Mushrooms contain antioxidant properties[4], antineoplastic[5], anti-inflammatory activity[6], hepatoprotective activity[7], and cardioprotective properties[8]. This review will discuss one of the mushrooms, i.e., Schizophyllum commune Fr., its taxonomic details for identification, cultivation procedure, pharmacological effectiveness, and industrial usefulness.

Schizophyllum commune is an edible mushroom that belongs to the phylum Basidiomycota[9]. Swedish mycologist Elias Magnus Fries carried out nomenclature of split gill fungi in 1815. It is observed in all continents except Antarctica. Scientists have reported this from the deadwood of at least 150 different plant genera[10], usually as white rot. In Africa and Asia, it is produced approximately 2.5 million tons per year[11], and it is used as chewing gum by the people of the Dutch East Indies and Madagascar[12]. It has been consumed as a nutritional food in Southeast Asia[13]. In India, the people of Manipur consume split gill fungi with fish and pork. Schizophyllum commune, regionally called lengphong, is available in the local market of Manipur and its nearby areas[14].

Schizophyllum commune is considered a widely distributed medicinally essential mushroom, as it produces Schizophyllan and a polysaccharide, which shows considerable pharmaceutical properties[15,16]. A β-glucan extracted from S. commune demonstrated anti-cancerous effects when combined with other chemotherapeutic agents[17]. It also has other potential applications, such as a biological response modifier, an enhancer of vaccines, a non-specific immune system stimulator, a genotoxic and cytotoxic agent, an anti-cancer therapeutic, and an anti-tumour agent[18]. It also has antiviral, antifungal, hepatoprotective, and anti-diabetic effects. This article prioritizes justifying the commercial value of S. commune, uplifting its nutritional and pharmacological importance, and emphasizing the working principle of bioactive constituents obtained from it.

-

Classification: Fungi, Dikarya, Basidiomycota, Agaricomycotina, Agaricomycetes, Agaricomycetidae, Agaricales, Schizophyllaceae, Schizophyllum Fr. 1815 (Index Fungorum, accessed on 17 December, 2024).

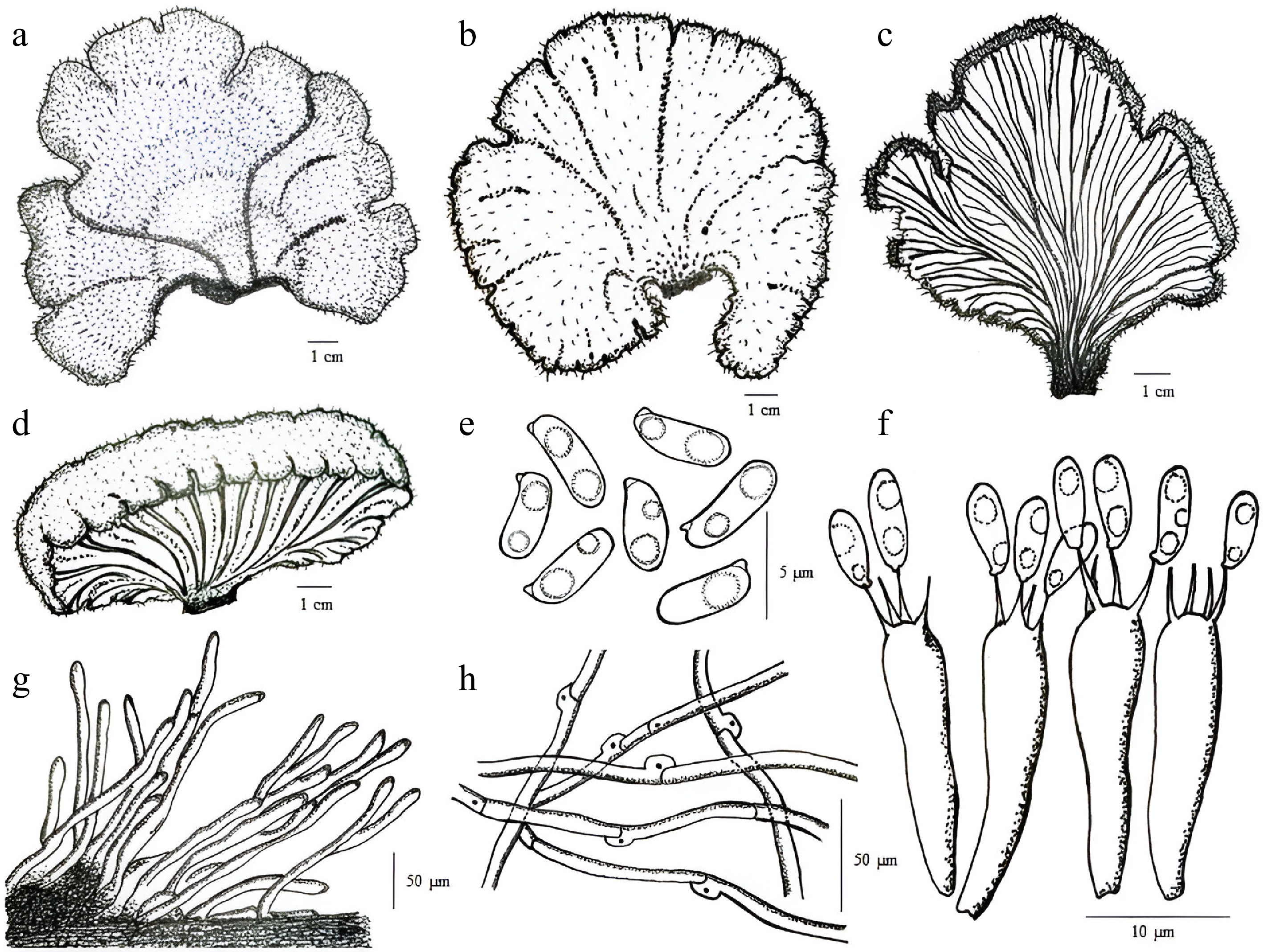

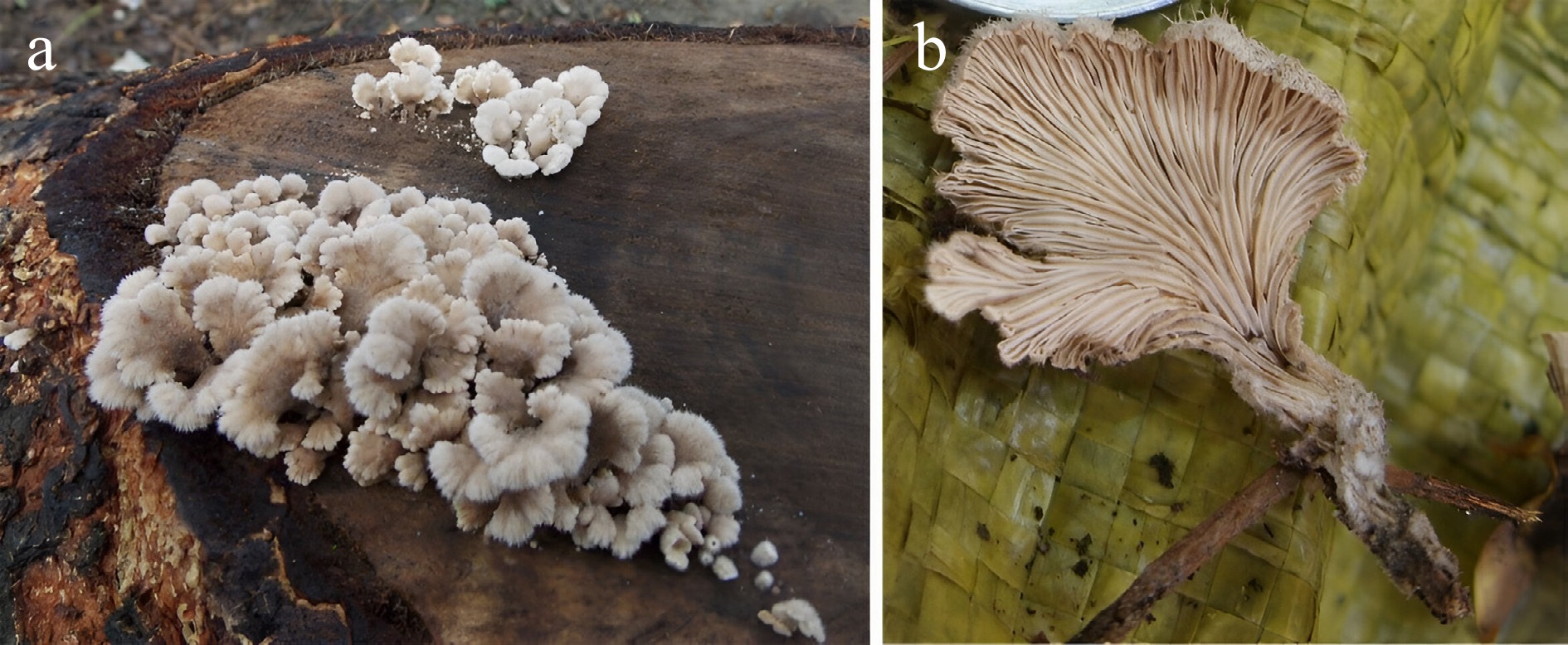

Fruiting bodies (Fig. 1) become shrivelled in dry weather and appear light grey to brown; the hymenophore is confined to the lower side. The marginal proliferation is distinctly visible. The fungus belongs to Basidiomycetes and is also known as 'split-gilled fungi' or 'split fungi' [19] as the gills function to produce basidiospores on their surface. During the dry season, the splits in the gill regions close the fertile zone as the fruit body shrivels and rehydrates when favourable environmental conditions return. Favourable conditions allow the reopening of these splits and expose the spore-producing structures to release the spores[20,21]. Figure 2 represents the basidiocarpic structure and microscopic characteristics of the split fungus.

Figure 1.

(a) Habitat photographs of S. commune (split gill fungus); (b) Ventral surface of the fruiting body. (Photographs captured by Chakraborty N, unpublished).

Special Notes: Solitary, sub gregarious to gregarious; on decaying hardwood sticks and logs and is extensively scattered in North America and worldwide. They are saprophytic on dead wood but can be parasitic on living wood. Fruiting body is 1–5 cm broad; fan-shaped when attached to the side of the log; irregular when attached above or below; small hairs are present covering the upper surface, dry, white to grayish or tan; under the surface composed of gill-like folds that are split down to the middle, whitish to grayish; without a stem; flesh tough, leathery, pale. Spore print white. Spores 3–4 × 1–1.5 μm; circular to elliptical; smooth. Cystidia is absent. Pileipellis is 3–6 μm wide. Clamp connections are present[20−22].

-

Several researchers[24−26], such as Debnath et al.[26], have characterized Schizophyllum molecularly. In most cases, ITS1 and ITS4 primers were used to conduct molecular studies on Schizophyllum. The PCR amplicon size ranges between 600 and 700 bp. Further, blast analysis can help with species-level identification.

-

Wild mushrooms are considered to be one of the most important components of the forest ecosystem, as they have a unique chemical composition, active pharmaceutical substances, and other biochemical constituents[27−29]. Out of multiple identified wild mushrooms, only a few are cultivated commercially on a very large scale throughout the world, and due to a lack of adequate information regarding the suitable substrate, the rest of them cannot be cultivated[30]. After multiple efforts on wild mushrooms, S. commune was also successfully cultivated.

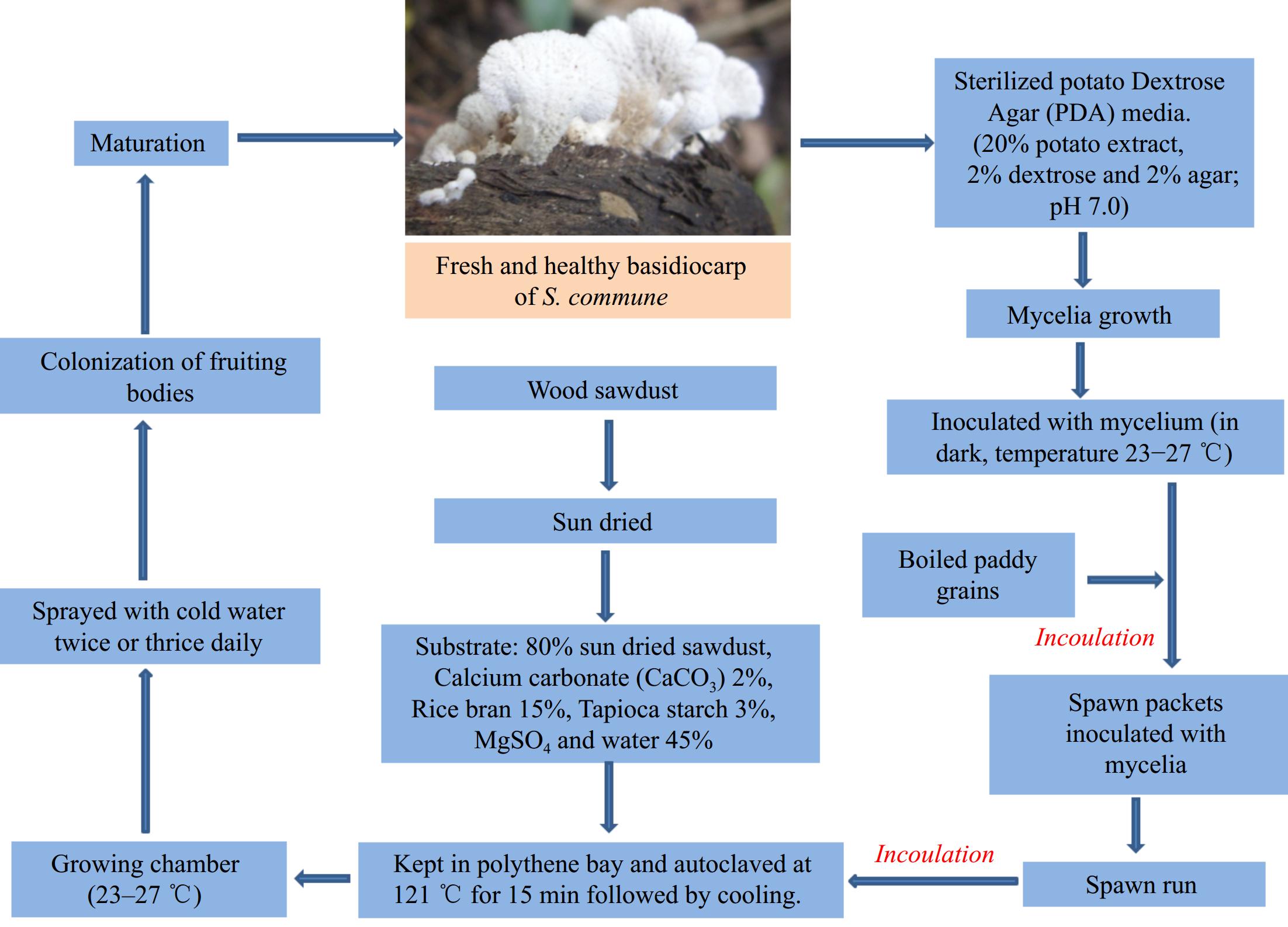

Considering split gill fungi, there are numerous classical techniques for producing fruiting bodies where wood chips or sawdust are used for substrate preparation. Being a wood rot fungus, S. commune shows a significant growth rate in a wide range of wood substrates. This article describes one successful cultivation technique proposed by Dasanayaka & Wijeyaratne[31].

Maintenance of pure culture

-

According to several researchers, the pure culture of Schizophyllum commune can be maintained in Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) media, which can be utilized for spawn production[32].

Spawn preparation

-

According to Dasanayaka & Wijeyaratne[31], paddy grains were selected and boiled for 30 min, followed by sterilizing them at 121 ºC and 15 lb/sq inch pressure. After sterilisation a standard inoculation process should be followed for each 200 g paddy grain packet under sterile conditions.

Substrate preparation

-

Different wood sawdusts (Dillenia indica, Terminalia catappa, Artocarpus heterophyllus, Mangifera indica, and Harpullia arborea) can be used for substrate preparation. All the substrates were sun-dried before use. Depending on the moisture content of substrates, the drying period varied from 4–5 d to 10–12 d[31]. Substrates were mixed with calcium carbonate (CaCO3) 2%, rice bran 15%, tapioca starch 3%, 0.1%–0.2% of MgSO4, and lastly water 45%[33].

Cultivation strategy

-

As per Dasanayaka & Wijeyaratne[31], the bag log technique is one of the successful techniques available for split gill mushrooms, where the mixture of the substrates are kept in 1 kg polythene bags. Finally, sterilisation was carried out by autoclaving at 121 °C and 15 lb/sq inch pressure for 15 min, then the entire setup cooled overnight. After cooling, a standard inoculation procedure was followed from 15-day-old solid or liquid cultures. All setups were kept in a dark inoculation room, and the temperature maintained at 23–27 °C.

Mycelium colonization

-

After the spawn run at 23–27 °C, a few holes were made at the top portions of the polythene bags. As per requirements, water was sprinckled two or three times daily[32].

Harvesting

-

As per Dasanayaka & Wijeyaratne[31], the first flush was expected after 30 d of inoculation. After completion of colonization of split gill fungi, mature fruit bodies were harvested, and young growing left undisturbed for further growth. Temperature and humidity of the growing chamber was maintained regularly for better yield. The schematic process of the traditional cultivation method is depicted in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Cultivation techniques of split gill fungus[31].

Singh et al.[29], recently suggested a similar cultivation technique as described by Dasanayaka & Wijeyaratne[31]. Commercialised cultivation of S. commune was standardised on paddy, wheat straw, and saw dust bag logs within a temperature range of 28 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity range of 80%–90%. According to the cultivation trial, the optimal substrate for the growth of S. commune is paddy straw supplemented with wheat bran, which achieved the highest fresh weight yield of 91.9 gm/bag, a biological efficiency of 18.33%, and a reduction in the number of spawn run days and time of harvesting[29].

Several organic substances are used in mushroom cultivation, such as crop residues, paper industry residues, and sawdust. Mushrooms cultivated on agricultural and industrial waste play a major role in recycling organic residues[34]. A unique strategy for bag cultivation using coconut meal as a substitute for rice bran was introduced by Preecha et al.[35]. Multiple other modern ideas are put forward from time to time, and a unique approach was described by Debnath et al.[26]. Where they not only considered the cultivation procedure of this wild mushroom but also, they had focused on an entirely eco-friendly cultivation technique. Using lignocellulosic biomasses as substrates instead of wood sawdust could be a great initiative.

The cultivation process is somewhat similar to Dasanayaka & Wijeyaratne's technique[31]. The main difference is the selection of a substrate for cultivation. In the eco-friendly approach, Debnath et al.[26] utilised agro-wastes like paddy straw, rice bran, and wheat straw, which gives potential to this cultivation technique.

-

Despite multiple contradictory views regarding split gill fungi, edibility is also considered one of the most important matters of interest. Nigeria and Malaysia initially considered split gill fungus edible[36]. After gaining popularity because of bio-modulators, it was consumed by the people of China, India, Mexico, and Asia. Traditionally, this mushroom is eaten by the people of tropical countries as food (fresh or dried). But Miller[37] considered this mushroom as inedible. He had put some justifications behind his postulation, i.e., S. commune is too small to be consumed and too leathery to be of good culinary impact, but later this theory was discarded. Some other findings by various authors supported him by saying that S. commune is known to be a potent pathogen for plants, animals, and even human beings; thus, high-risk factors may persist. Chandrawanshi et al.[38], have described this mushroom as non-consumable. Other researchers proposed a contrary view, as the mushroom contains vitamins, minerals, and macro- and micro-nutrients. It is one of the most well-known macrofungi in far Eastern countries due to the presence of bioactive components, and it is consumed mainly in Asian countries like Thailand, China, Vietnam, and Malaysia[39].

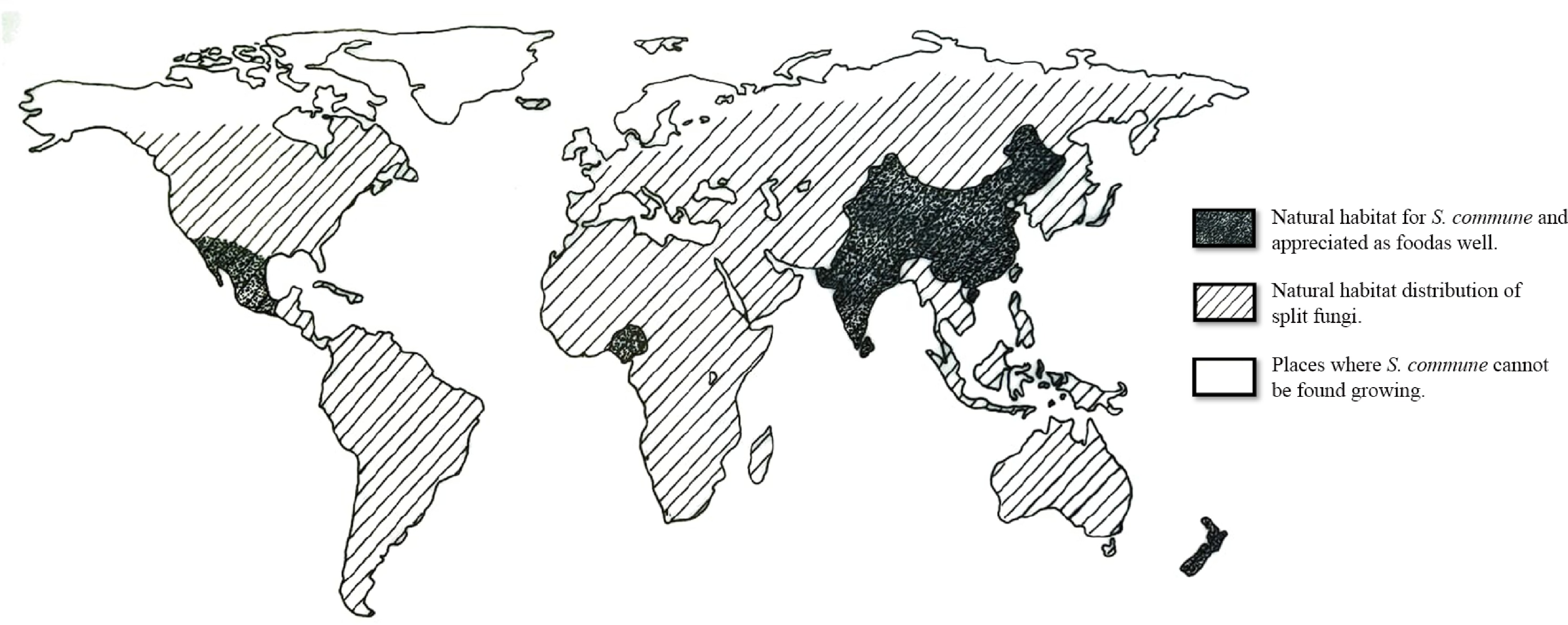

An experimental survey on the natural distribution and culinary engrossment of split fungi was conducted by Utrecht University in collaboration with NWO (Dutch Research Council—Earth and Life Science, Humanities, The Hague), ZonMW (Medical Research Council, The Hague), MU Artspace (Eindhoven), and Waag Society (Amsterdam). According to their report, a worldwide distributional map has been prepared (Fig. 4).

-

Multiple beneficial effects of macrofungi, apart from their novel dietary supplements, are gaining the interest of scientists. These interests are growing due to the implication of mushrooms to cure diseases[40], to strengthen the immune system to combat certain diseases, or may reduce their outcome[41], in bioremediation[40,42,43], and lastly as food[44,45]. Vigorous experimental outcomes indicated mushrooms as a rich source of nutrients, and multiple comparative studies showed that mushroom's nutritional value is comparable to meat, egg, and milk[46−48]. Various nutritional and therapeutic importance have increased the commercial value of mushrooms.

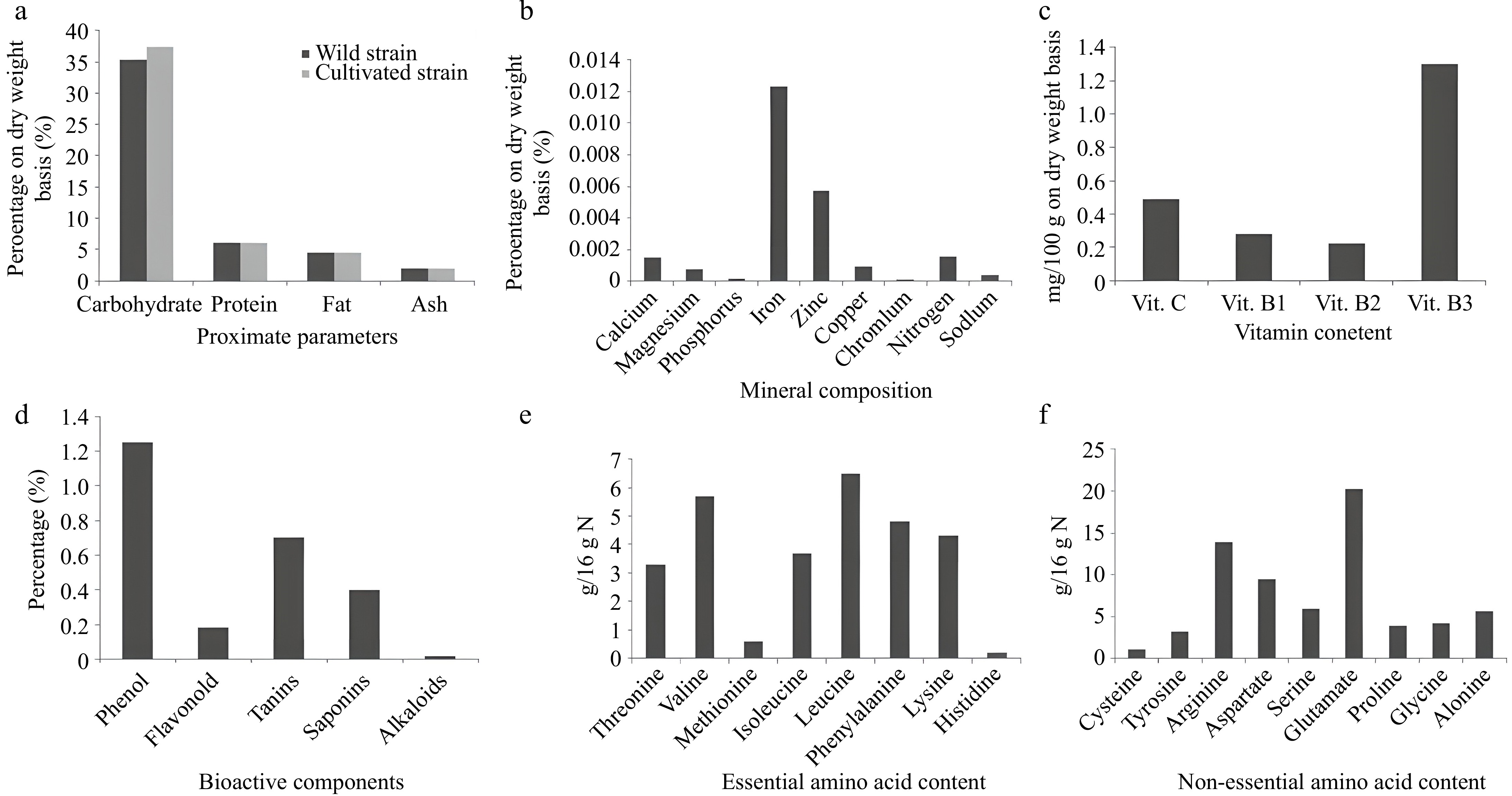

Almost all mushrooms have high dietary qualities and are abundant sources of amino acids[49,50]. Schizophyllum commune is a rich source of multiple macro- and micro-nutrients, minerals (Fig. 5b), vitamins (Fig. 5c), and multiple bioactive components (Fig. 5d), which make it a perfect dietary substance with a balanced quantity of protein, carbohydrates, and fat.

Figure 5.

(a) Comparative analysis of the proximate composition of wild vs cultivated strains of S. commune. (b) Mineral composition. (c) Vitamin concentration. (d) Bioactive component composition. (e) Essential amino acid composition. (f) Non-essential amino acid composition of S. commune[32,51−54].

Herawati et al.[32] reported the proximate composition of split gill fungi. According to their study, wild and cultivated strains of S. commune will have different proximal parameters. Though the results were almost similar, the minimum differences between these two strains were recorded (Fig. 5a). Nowadays, it's a natural practice to incorporate split gill fungi into daily diets.

Longvah & Deosthale[51] also illustrated the amino acid constitutions (Fig. 5e; f) of split gill fungi (amino acids are expressed as g/16 g nitrogen, which is equivalent to g/100 g protein). The following graphical representations show different parameters (Fig. 5).

Longvah & Deosthale[51] determined the fatty acid (both saturated and unsaturated) composition of S. commune from northeast Indian origin, and the outcomes are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Depiction of the fatty acid content of split fungus[51].

Fatty acids Structures Percentage (%)

based on

btotal fatPalmitic acid (16C) CH3-(CH2)14-COOH 20.8 Stearic acid (18C) CH3-(CH2)16-COOH 2.5 Arachidic acid (20C) CH3-(CH2)18-COOH 0.2 Oleic acid (18:1) CH3-(CH2)7-CH=CH-(CH2)7-COOH 10.4 Linoleic acid (18:2) CH3-(CH2)3-(CH2-CH=CH)2-( CH2)7-COOH 61.3 Linolenic acid (18:3) CH3-(CH2-CH=CH)3-(CH2)7-COOH 4.8 -

Traditional knowledge, rather than ethnological ideas of any wild fungus, gives a platform for better understanding and provides us with the basic idea of its edibility, toxicity, or medicinal value. Local markets of different countries are filled with a wide range of wild mushrooms, and one of the most popular ones is 'Kulat Kodop,' the common name of S. commune. The Dusun Tindal people of Malaysia and the people of Pakistan commonly call it 'Kulat Kodop', in West Bengal, India, S. commune is known as 'Pakha Chhatu'[55]; in Manipur, the same mushroom is known differently by their vernacular names like 'Kanglayen', 'Lengphong', 'Movupa', and 'Pashi'[56], on the other hand, people of Peninsular Malaysia call it 'Kulat Sisir'[57]. Natives of Sabah also had a huge knowledge regarding the culinary interests and medicinal values of the S. commune. Ethnic groups like the Ngelema people of Congo also consume Kulat Kodop daily[58].

Though the texture of S. commune is a bit chewy, it is still very common in the local markets of Mexico[59]. A few traditional dishes were eaten by Dusan people, like 'Seunding', which is prepared by mixing dry Kulat Kodop with tahua (endemic ginger in Malaysia); they also serve this wild mushroom in curry with ginger flower and potatoes. In a few regions, this fungus is eaten throughout the year due to its easy availability. Another popular dish in local Dusan is 'Tinamba Linopot', which is split gill mushrooms cooked with chicken or beef meat and covered with banana leaves. People of Indigenous communities prefer to fry S. commune and have it with sambal sauce. Kulat Kodop is also consumed by the Dusan communities of Kundasang with the meat of squirrel, chicken, and white chilies in porridge[57]. In India, some regional people consume it as pakora after deep-frying it with gram flour[55].

Several myths related to split gill mushrooms are also common among the people of Tshopo Province; for instance, a young mother, who is suffering from the side effects of Trichomonas vaginalis is forbidden to consume S. commune as it could lead to crib death[58]. Multiple surveys revealed the people of Dusan possessed a deep command of the medicinal importance of Kulat Kodop. They have used S. commune for years due to its antimicrobial properties[60]. Mexican people are treating illness and many disorders like weakness, wound treatment, obesity, cold and cough, indigestion, rheumatism, breast inflammation, intestinal pain, and headache using split fungus[58,61].

-

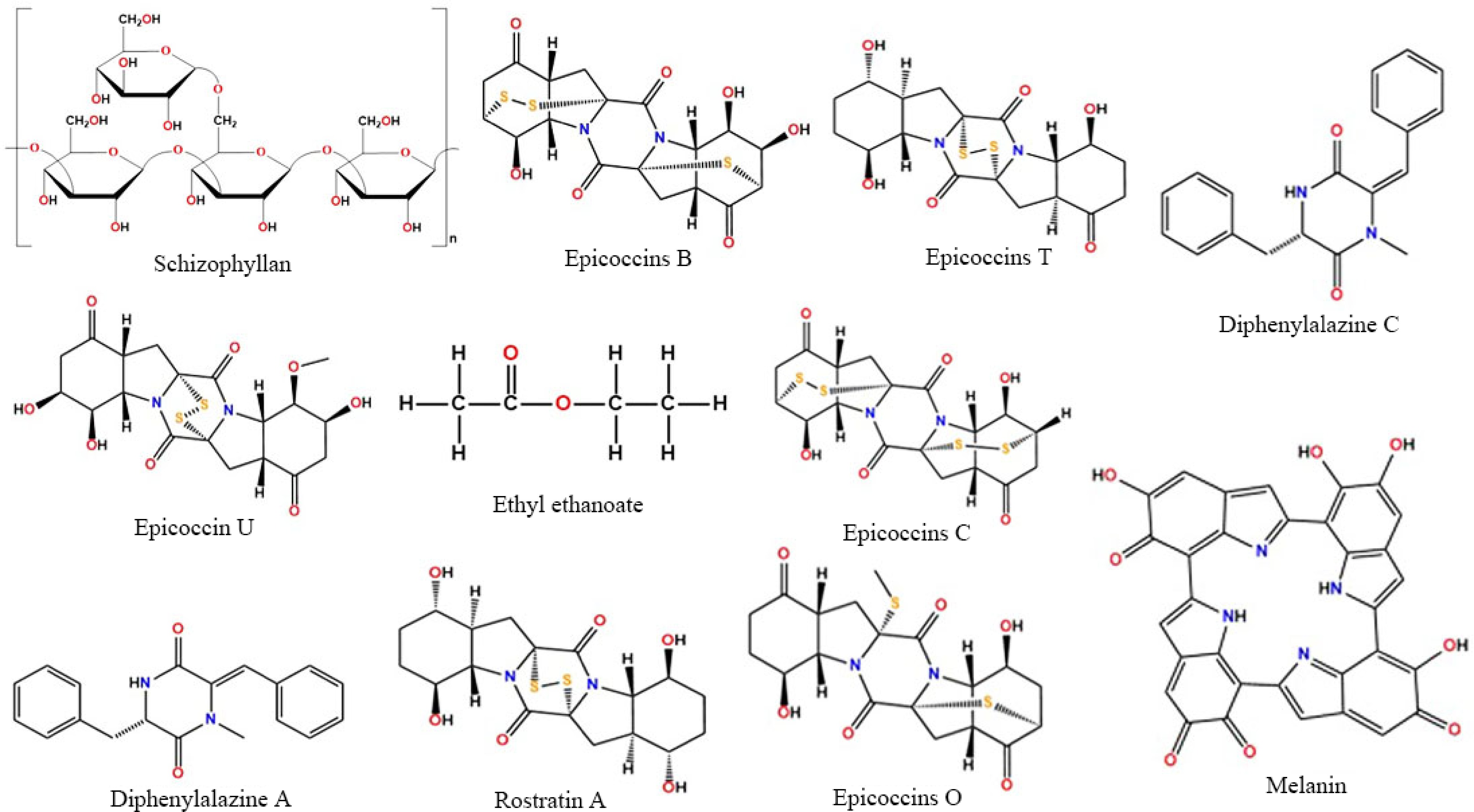

Besides having enormous nutritional value, split gill fungus is also acknowledged for its bioactive components and therapeutic effect. A few biopolymers obtained from the aqueous culture of S. commune, possess pharmaceutical impact. Schizophyllan, hydrophobin, schizocommunin, indirubin, isatin, N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc)-specific lectin, indigotin, and tryptanthrin are some of these bio-modifiers extracted from this fungus[52,62]. Each of these shows different chemical properties and proves the presence of a diverse group of biopolymers. Hydrophobins are minute protein molecules that contain eight conserved cysteine residues with a hydrophobic nature. The N-terminus of S. commune Lectin (SCL) is blocked, but sequence similarities could still be seen with plant lectin[62]. Schizocommunin is an indole derivative[52] whereas schizophyllan is a triple-stranded helix protein that dissolves in water. Schizophyllan is the most widely studied biopolymer (glucan) of S. commune and alternatively known as SPG, sizofilan, sizofiran, and sonifilan. The activity of schizophyllan depends on 1,3-β-D-Glucan[63]. Its molecular weight, structure, and branching pattern determine efficiency. It is now proven that branched glucans show higher biological response against certain forms of cancer[64]. Diketopiperazines are a group of biopolymers extracted from various mushrooms, including S. commune. Previously the presence of Epicoccin B, Epicoccin C, Epicoccin O, Epicoccin A, Diphenylalazine A, and Rostratin A in split gill fungus was confirmed by Guo et al.[65], and Wang et al.[66], but in recent days two more biopolymers from this group were found to be obtained from S. commune i.e., Diphenylalazine C and Epicoccin U[67]. A few bioactive components and their chemical structures are given in Fig. 6.

-

Evidence suggested the presence of multiple fractional compounds in the extract of S. commune. Initial efforts were made to understand the medicinal efficacy of split mushrooms, where different types of extraction procedures were utilized, and all the extracts showed different degrees of pharmaceutical properties. Studies showed the variable ability of methanol, ethanol, dichloromethane, and water extract against certain medical conditions. These crude extracts obtained from split gill fungus also have adequate pharmaceutical roles. Such manifestations are documented in Table 2.

Table 2. Representation of a few crude extracts obtained from split gill fungus along with their working mechanism.

Sl. No. Crude extracts Pharmaceutical properties Mechanism of action Ref. a) Ethanolic extract Antioxidant Largest exposed tissue system to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the skin which is very much susceptible to biological stress caused by ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species), and this will promote early aging and overproduction of melanin. Here comes the role of antioxidants. Ethanol extracted from S. commune exhibit antioxidant property which can delay senescence and inhibit excess melanin formation. [68] Anti-tyrosinase Phenol oxidase or Tyrosinase is the precursor for melanin production, and overproduction leads to hyperpigmentation. Kojic acid is known to be the most efficient tyrosinase inhibitor. Split gill fungi also possess a certain amount of ethanol, which is also effective against phenol oxidase to some extent. [68,69] Anti-acetylcholinesterase Acetylcholinesterase (AchE) is an Alzheimer's disease (AD) promoting agent. The ethanol (EtOH) and polysaccharide (PSH) extracted from S. commune can efficiently inhibit the formation of AchE and reduce the chance of developing Alzheimer's disease. [70] b) Methanolic extract Antidiabetic Patients with diabetes may suffer from an array of clinical disorders, such as coronary, renal, cardiovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases. In recent days, methanol extract from split fungi has been demonstrated to have anti-diabetic activity with phytochemical validation. Accordingly, it could be a great natural alternative to synthetic anti-diabetic drugs. [38] c) Methanol, Ethyl acetate and Dichloromethane Anti-microbial Extracts of split gill fungi, i.e., Methanol, Ethyl acetate, and Dichloromethene, showed impressive results against the growth of numerous common pathogenic bacteria (Escherichia coli, Shigella flexneri, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus subtilis) and fungi (Yeast, Candida parapsilosis). However, Dichloro-methane showed the best results against microbial growth, whereas the other showed moderate activity. [60] d) Exopolysaccharide Anti-inflammatory The anti-inflammatory effect of exopolysaccharide obtained from split gill fungus was determined by its helical structure and molecular weight. It was reported that high—and medium-molecular-weight exopolysaccharide is effective against intestinal inflammations. [71] e) Ethanol (EtOH) and Polysaccharide (PSH) Anti-Alzheimer Both EtOH and PSH extracted from S. commune showed preventive effect against Alzheimer's disease (AD) through the production of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors. However, the activity of PSH extraction showed comparatively greater efficiency. [70] f) Dichloromethane Anti-bacterial Crude extract of S. commune containing Dichloromethane showed excellent efficacy against certain gram (+) bacteria like Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus aureus. Thus, the mycelia of this mushroom have antibacterial drug-yielding potential. [72] g) Ethyl acetate or ethyl ethanoate(C4H8O2) Anti-diabetic Ethyl acetate extracted from S. commune has potential inhibitory activity against streptozotocin-induced diabetes in Wistar rats. Ethyl Ethanoate can cause a significant decrease in the blood sugar level and an increase in body weight in just 14 d after application. [73] Apart from its crude extracts, some purified components were introduced to medical science, which possess multidimensional medicinal prospects. Split gill fungus is an excellent biomodulator with ample immunogenic response. Some of its immune-modifying behaviours are explained in Table 3.

Table 3. Representation of some immuno-modulators along with their working principle.

Sl. No. Immuno-

modulatorvx dfsTreated for/ pharmaceutical properties Mechanism of action Ref. a) Sizofilan (SPG)/

Sizofiran/

SchizophyllanHead and neck cancer Therapeutic effect of Sziofilan (SPG) can increase the recovery rate of cellular immunity, hazarded by radiation, surgical methods and chemotherapy. Mainly effective against neck and head cancer. [74] Ovarian adenocarcinoma and carcinoma, SPG can decrease the growth rate of tumors in combination with cisplatin, when given prior to photodynamic therapy, in ovarian adenocarcinoma of rats and carcinoma in mice. [75,76] fibrosarcoma, and bladder cancer The reduction of growth rate and metastatic foci in squamous-cells and an increase in survival time could be observed by the activity of SPG against bladder cancer and fibrosarcoma in mice. [77,78] Anti-tumor Two cytokines i.e., Interferon- γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin 2 (IL 2) produced by Scizophyllan are found to be increased in the culture medium of phytohemagglutin (PHA)- or concanavalin A (Con A)- stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were measured by radioimmunoassay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This evidence suggests the anti-tumor activity of Schizophyllan. [79] Anti-hepatotoxicity The beneficial role of Schizophyllan against chronic Hepatites B could be observed due to its increased immunological responsiveness to the virus, specifically in IFN-γ production. [80] Cervical carcinoma Sizofiran activity can increase the survival rate of human cervical carcinoma when combined with 5-fluorouracin after radiotherapy. Sizofiran is an immunotherapeutic agent for cervical carcinoma because it stimulates a rapid recovery of the immunogenic parameters by radiotherapy. [81] Protective against chemotherapy and radiation After treating the bone marrow with chemotherapy or radiation, Sizofiran can reinstate cell mitosis and lower the sister chromatid exchange in mice. [82] Sizofiran can partially protect mice's bone marrow's Natural Killer (NK) activity after treatment with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). [83] b) Lectin Cytotoxic activity A glycoprotein, viz., lectin obtained from S. commune (SCL), showed high cytotoxic activity against epidermal carcinoma in humans. [62] Mitogenic activity Lectin also possesses mitogenic activity against mouse splenocytes, and its inhibition was maximum at a concentration of 4 μM. [13] c) Schizocommunin Anti-lymphoma Schizocommunin is an indole derivative extracted from a liquid culture of split gill fungi. It has established strong cytotoxic activity against murine lymphoma cells. [63] d) Diphenylalazine C

and Epicoccin UCytotoxic activity The cytotoxic activities of these two biopolymers were assayed by the MTT method against human gastric cancer, human leukaemia, and human myelogenous leukaemia. The results were positive, as they possess mild cytotoxicity against these cell lines. [67] d) β-D-Glucans Anti- cancerous β-D-Glucans extracted from split gill fungi are known to fight against cancers by modulating both innate (nonspecific) and adaptive (specific) immune systems. [84] e) Extracellular melanin Antioxidant Comparatively, a lower concentration of extracellular melanin shows a high free radical scavenging activity of DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl), which indicates the presence of antioxidant properties in S. commune. [85] Epidermoid larynx carcinoma Melanin also shows visible positive impact on inhibition of cellular proliferation of human epidermoid larynx carcinoma cell line (HEP-2). [85] Other than immune-modulating activities, S. commune has much more to serve in the pharmaceutical industry, from anti-microbial to anti-aging properties, from anti-hyperlipidemic to anti-tyrosinase activity, from anti-inflammatory to anti-diabetic effect and the list continues. Footprints of this mushroom in the medicinal world are compiled in Table 4.

Table 4. Overview of bioactive components obtained from S. commune and their medicinal properties and working mechanism.

Sl. No. Bio-active

compoundsPharmaceutical properties Mechanism of action Ref. a) Sizofilan (SPG)/

Sizofiran/

SchizophyllanAnti-viral Sendai virus infection and Kuruma shrimp with Penaeus japonicas virus infection in mice showed high survival rates and phagocytic activity when treated with SPG. It has visible positive effect against certain viral diseases. [86,87] Anti-inflammatory SPG shows a positive inhibitory effect against inflammation in murine macrophages. This property makes SPG useful for treating some periodontal issues. [88] Anti-fungal Schizophyllan can control the activity of Candida albicans (candida static activity), an allergic fungus, in mice. [89] UV photo-protectant and anti-aging Schizophyllan is well known for its protective activity against UV radiation, anti-inflammatory effect on the skin, and anti-aging properties. [90] prebiotic The growth and development of gut microbiota and its associated metabolic functions are influenced by the prebiotic activity of 1,3-β-D-Glucan. Dietary interference with prebiotic activity will also increase total bacterial abundance and metabolisms related to host immune strengthening. [91] b) Lectin Anti-viral Lectin can inhibit certain pathogenic viruses. It can target multiple stages of the viral life cycle, such as viral penetration, attachment to the host cell, and replication inside the host. [92] The inhibitory activity of lectin has already been proven. However, it also possesses inhibitory activity against HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. As a result, lectin can be used for the treatment of HIV in the future. [13] c) Flavonoid Anti-hyperlipidemic Flavonoid from S. commune has an inhibitory effect on hyperlipidemia. A significant change in lipid profile marker parameters (Total cholesterol, Triglycerides, LDL, HDL cholesterol) level was observed when hyperlipidemic rats with high-fat diet (HFD) were treated with flavonoid extract of split fungi. [93] Anti-hypothyroidism Induced hypothyroidism in rats by applying 0.1% Aminotriazole can be controlled by applying flavanoid extract of S. commune. Though there was no change in T3 level, a significant increase in T4 and TSH levels could be observed after treatment, which indicates a positive impact on hypothyroidism. d) Sesquiterpenes Anti-fungal and anti-bacterial Sesquiterpene, a volatile substance extracted from split gill fungi, can inhibit bacterial and fungal growth and is effective against wood-decaying fungi and bacteria. [94] e) Epicoccin U and Diphenylalazine C Antimicrobial Epicoccin U and Diphenylalazine C can significantly show their antifungal and antibacterial effects. Though it is considered to be a weak inhibitor, it is still effective against Candida albicans, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus. [67] f) β-D-Glucan Wound healing activity One of the main constituents of the cell walls of bacteria, fungi, and cereals is β-D-Glucan. As we already know, S. commune can produce β-D-Glucan, which has a significant role in wound healing through the migration of keratinocytes or fibroblasts. [95] g) Extracellular melanin Anti-microbial At a high concentration, melanin can act as an antimicrobial component. It showed a significant inhibitory effect against E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Psuedomonas flurescens. Melanin is also effective against pathogenic fungi, such as Trichophyton simiii and T. rubrum. [85] -

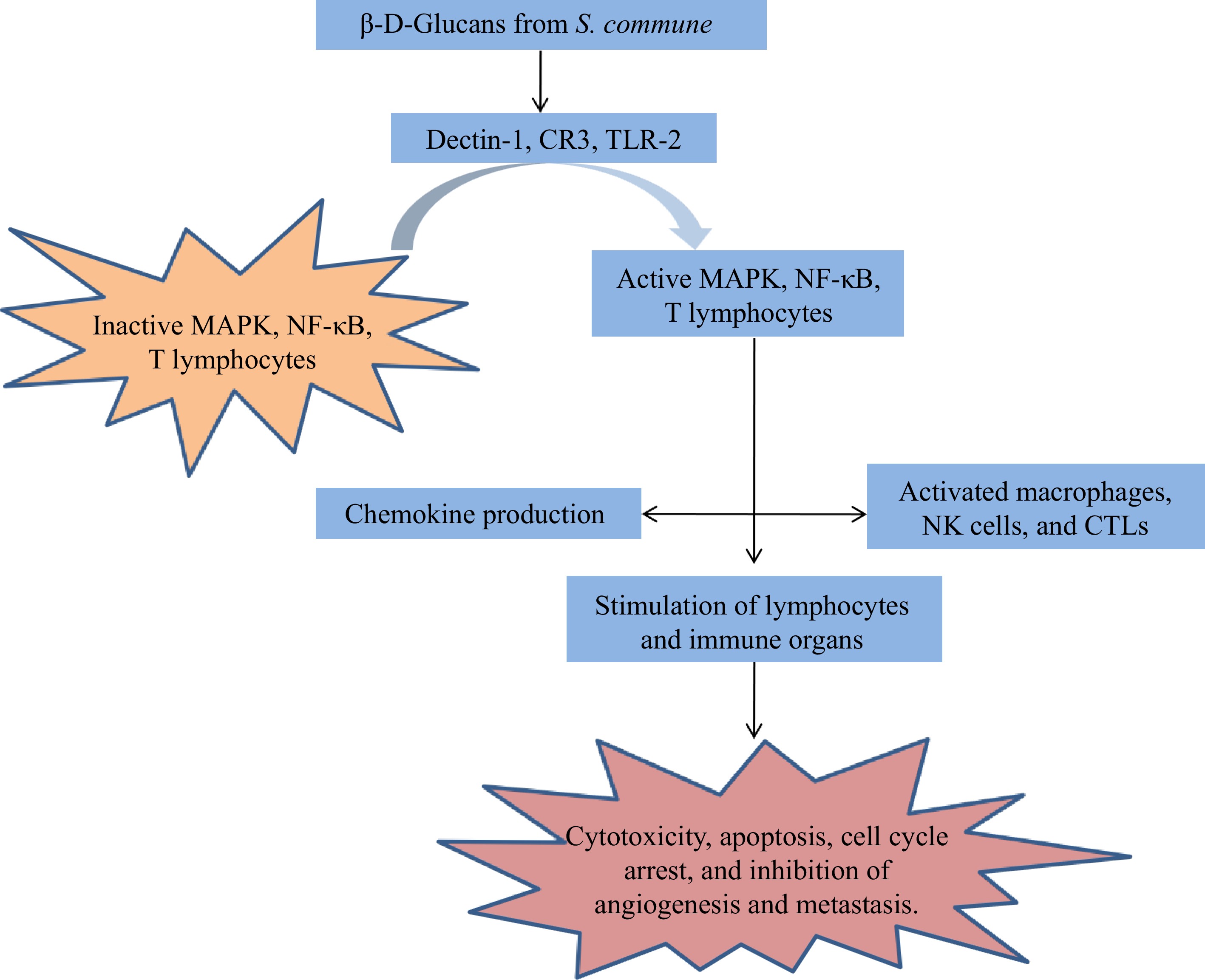

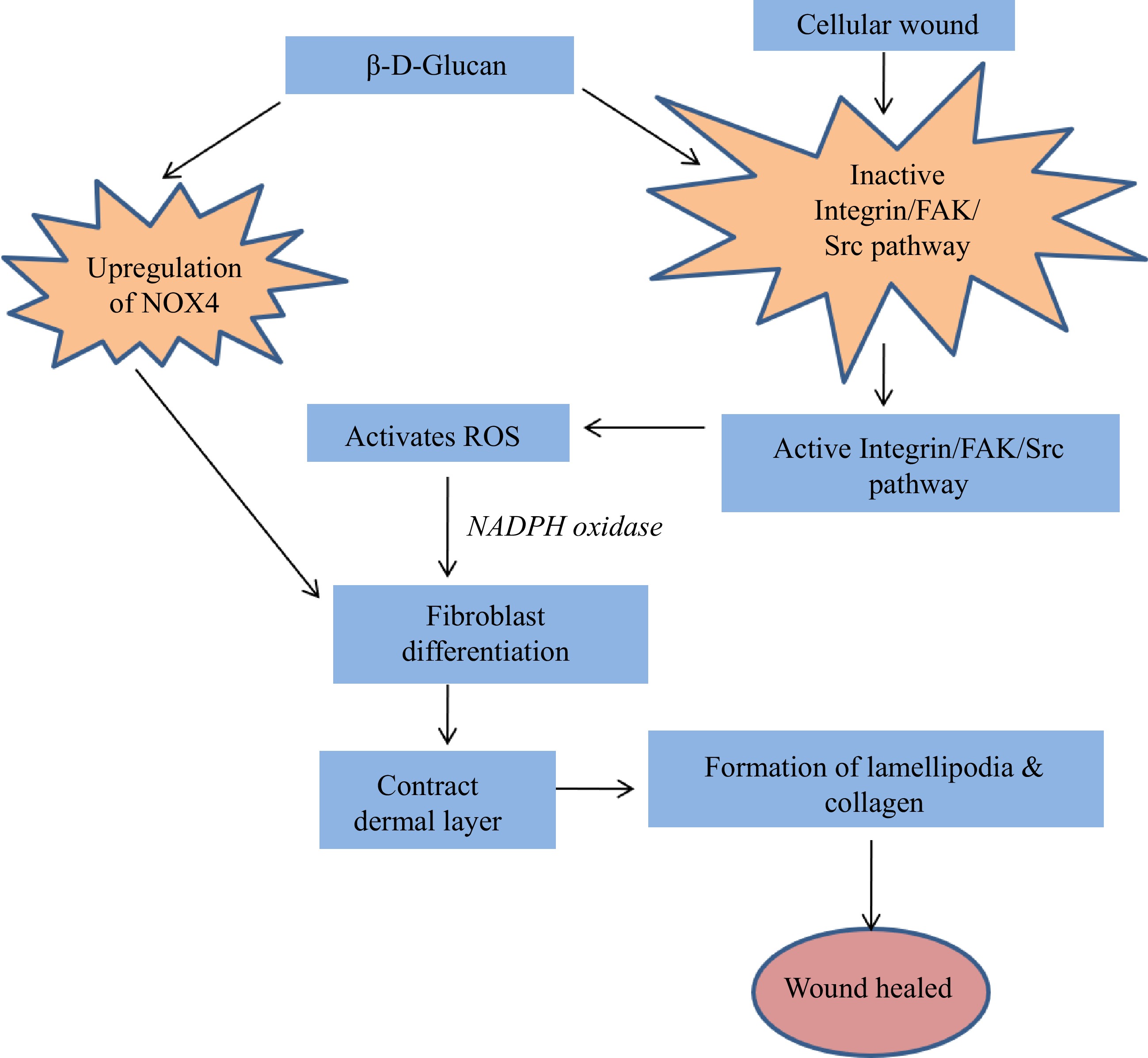

Though multiple immune-modulators and bioactive components are taken together, reports suggest that the mechanism of action of each one of these compounds is distinct from the other. Out of these, a few compounds and their working principles are well illustrated, whereas other mechanisms of action are still undiscovered. Here in this article, the mode of action of β-D-Glucan is described, and Figs 7 & 8 suggest the diversified working principle of this novel compound against different medical conditions. β-D-Glucan, while working against cancer[84] will activate MAPK, T lymphocytes, and NF-kB and, through activation of macrophages, can stimulate lymphocytes, which will lead to an apoptotic pathway or cell cycle arrest (Fig. 7). The same compound manifests some different pathways during wound healing activity[90], whereby activation of integrin, the FAK or the Src pathway, fibroblast differentiation is achieved, which, along with up-regulation of NOX4, can produce lamellipodia and collagen, and this eventually heals the wound (Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

Probable mode of action of β-D-Glucan against cancer[84].

Figure 8.

Wound healing efficacy of β-D-Glucan obtained from S. commune[95].

Interestingly, a ribonuclease (RNase) was obtained from the fruiting bodies of S. commune, with a molecular weight of 20 kDa. This RNase could inhibit HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and its activity is maximum at a temperature of 70 °C and 6.0 pH[96]. Even a few drugs are available in the market that can treat or reduce the effectiveness of HIV in general.

-

Alternative splicing agents are very common nowadays; using this, one can have multiple functional transcripts from a single unprocessed pre-mRNA in eukaryotes. Though the process is a bit complex, a number of fungi have been reported so far as having this property[97]. Bio-genomic studies exposed a similar mechanism in S. commune to splice pre-mRNA[98]. Moreover, it was also found that S. commune possesses much more splicing capacity than any other fungi[98]. Thus, it can be used further for molecular exploration and biotechnological studies.

Production of feruloyl esterase

-

Feruloyl esterase (FAEs) is an evolutionary component of the food industry as Ferulic acid is considered to be the precursor for some flavoring agents, like vanillin and 4-vinyl guaiacol[99]. Along with these, FAEs are also efficient for biomass degradation and valorization of food processing wastes[100]. Feruloyl esterase isolated from split gill fungi was expressed in Pichia pastoris. There are two functional pathways to extract ferulic acid from agricultural side products, i.e., (i) Chemical treatment, which involves alkaline hydrolysis and this process is time taking and also causes pollution[101]; (ii) Enzymatic hydrolysis, which is a rapid, eco-friendly technique[102,103]. The isolation of feruloyl esterase from S. commune showed an alternative source of FAEs, as an industrial dependency on feruloyl esterase synthesis had led to a huge production cost.

Ethanol fermentation by S. commune

-

The concept of biofuel is gaining interest. It is produced from lignocellulosic biomass and consists of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose residues, but the process is quite expensive[104]. Recent studies revealed the potential of S. commune to degrade lignin, cellulose, and hemicelluloses. S. commune also shows ethanol fermenting properties under semi-anaerobic conditions. The production rate gets significantly higher when split fungus is combined with cellulase[105].

Production of lipase

-

The utility of lipase for various industrial purposes is notable, from food to bio-fuel, detergent to leather, textiles to the paper industry, and many more. Its use in the dairy, baking, fruit juice, beer, and wine industries is remarkable[106]. On the other hand, this enzyme is also useful in improving the flavour and texture of cheese[107]. Lipase can also be produced from S. commune on sugarcane bagasse supplemented with used cooking oil via SSF (solid state fermentation), leading to the formation of two types of lipase i.e., S. commune Lipase A (ScLipA, 30%) and S. commune Lipase B (ScLipB, 70%). To understand the hydrolysis capacity of lipase isolated from S. commune, coconut oil, fish oil, and butter were used in the process of free glycerol assay. According to Kam et al.[108], lipases have unique properties useful in industrial applications, especially those targeting cost-effectiveness and low downstream processes. Apart from this, Negi[109] reported using lipase in processing eggs, vegetable oil, bakery industry, meat, and the fish industry.

Insecticidal potential of S. commune

-

Insecticides are used in farming (both in the agricultural and horticultural fields) to control insect populations, which results in high productivity. Furthermore, most insecticides are inorganic in origin; they can cause multiple harmful effects on nature as well as on the living world, including humans[110]. So, some eco-friendly approaches should be made for the good of human health and the environment. After conducting multiple experiments, it has been observed that the insecticidal capacity of certain fungi can be advantageous as they are low in cost and, moreover, safe for the environment[111]. Studies have revealed the genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of S. commune, which can be used against certain insects. Split gill fungi obtained from Aloe vera show an inhibitory effect against Spodoptera litura. Apoptosis and necrosis could be seen in the larval stage if treated with fungal extract; they can also cause huge oxidative stress to S. litura, which leads to DNA damage[112]. This could be a possible environmentally-friendly and safe substitute for inorganic insecticides.

Decolourization of synthetic dyes

-

Artificial dyes are one of the major environmental pollutants that can cause harm to living beings and are mainly extracted from paper or textile industries. Decolorising these synthetic dyes is not easy, and the physio-chemical processes available to degrade these dyes are costly and non-eco-friendly[113,114]. Multiple reports are put forward from time to time regarding the dye-degrading ability of some microorganisms[115−117]. In recent studies, the ability of S. commune to decolourise solar brilliant red 80 direct dyes was put forward. Its efficiency was at its highest level when pH was 4.5, and the temperature was maintained at 30 °C. The main mechanism of dye degradation lies in a few enzymes like laccase (Lac), lignin peroxidase (LiP), and manganese peroxidase (MnP) isolated from split gill fungi[118]. The ligninolytic activity of S. commune could be an excellent alternative to the decolourisation of artificial dyes and can be used for bioremediation.

Production of bio-preservative

-

Schizophyllum commune can efficiently produce a biopolymer viz, schizophyllan, which was explored for several medicinal properties. However, recent studies have revealed acetaldehyde production from schizophyllan, which has strong anti-microbial activity[119]. Oxidised form of Schizophyllan is applicable against a broad range of bacteria (both gram-positive and gram-negative). Using the different concentrations of acetaldehyde, raw goat skins can be preserved at an ambient temperature. The preservation technique by scleraldehyde is an environment-friendly process and can bring an evolution in the Tanning industry. This bio-preservative can be a good alternative to NaCl, which can eventually reduce the pollution made by tanning industries.

Immobilization of lignin peroxidase and pectinase produced by S. commune for industrial exploration

-

Immobilization of an enzyme makes them available economical biocatalysts that are reusable and relevant for industrial purposes. Both pectin lyase and lignin peroxidase are industrially useful enzymes and were reported to be extracted from S. commune. After isolation, enzymes were purified, followed by immobilization on chitosan beads. Immobilized lignin peroxidase is excellent in removing dyes, even better than free lignin peroxidase[120]. Its high thermal stability property makes it appropriate for bio-technical uses. On the other hand, an immobilised form of pectinase is suitable for the fruit juice and detergent industry[121].

Mycoremediation potential

-

A wood-rotting fungus's biomass was utilized to treat electroplating wastewater containing these heavy metal ions[122]. Recently mycoremediation activity of S. commune has been reported to be against malachite green (MG) dye. Excessive use of malachite green can be seen in the textile, leather, and paper industries as an antimicrobial in aquaculture. Still, this dye is toxic to our respiratory system, liver, gill, kidney, intestine, gonads, and pituitary gonadotropic cells[123]. A screening test shows efficacy of 97.5% when cultured on PDA media in combination with MG dye[124]; the mycelia growth can degrade MG dye within 10 d[125]. Thus, it can be used as a potent mycoremediator in the near future.

Utility in the cosmetic industry

-

The cosmetic industry is one of the most developing and promising industries today. Rather than using harmful chemicals, the use of organic or natural products is acceptable anytime. The usage of S. commune in the cosmetic industry was first revealed in Thailand, where they use a polysaccharide viz. schizophyllan for healing wounds. Later, its anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and depigmentation properties were reported[126]. Multiple commercial creams are available in the market in Thailand by the name of 'Krang cream', which are obtained from split gill fungi with anti-aging and anti-microbial properties against Aspergillus niger, and Candida albicans[127].

-

Wild mushrooms may contain high nutritional parameters and pharmacologically efficient biomolecules, which can cause huge requirements for these mushrooms in the commercial field. The total productivity of these mushrooms in their natural habitat is not as much as the commercial need, and S. commune is one of them. This fungus grows abundantly in the rainy season and frequently appears on dead wood. Still, its commercial demand is too high to be fulfilled due to the presence of immune-modulator compounds and nutritive values. Even comparative studies between wild and cultivated varieties of this mushroom showed that only a few nutritional parameters may differ slightly. Still, other than that, vitamins, mineral composition, and bio-active components are similar in both strains. Therefore, it is evident that strain differentiation doesn't interact with mineral composition. Multiple industries, like lather, dairy, detergent, cosmetics, textiles, and bio-fuel industries, also rely on S. commune for its unique biochemical composition. Nowadays, it is used to produce eco-friendly insecticides, flavoring agents, and bio-preservatives, which can reduce the use of life-threatening chemicals regularly. Thus, it is evident that natural dependency is not enough to meet the requirement, and as an alternative process, no other options are left except the mass cultivation of S. commune. Moreover, artificial cultivation has advantages over natural production as we can get a huge flush of fruiting bodies in comparatively less time, and seasonal dependency can also be avoided.

Cultivating this mushroom not only helps to meet the needs of the commercial market and reduce the overexploitation of S. commune from the field but also can provide a great source of income for many. As various strains of S. commune are available, some of which have evolved and some carry the wild characteristics of the old world, it could be a great research field to find out whether the presence of bioactive constituents is related to its wildness. Other than this, taxonomic exploration can be done to understand its nature. Moreover, developing an easy cultivation process, proper detection of strains by modern molecular biology techniques, and understanding the pathways through which obtained compounds act on diseases could give us a gift for solving various problems of mankind.

-

Not applicable.

Nilanjan Chakraborty sincerely acknowledges the financial support from the DST-FIST Programme-2023 (TPN-89897) under the Ministry of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Acharya K, Chakraborty N; data collection, data extraction, data interpretation, and preparation of word diagrams and figures: Dasgupta D; writing - draft manuscript preparation: Basu P, Dasgupta D; writing - manuscript editing: Paul A. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Dasgupta D, Basu P, Paul A, Acharya K, Chakraborty N. 2025. Schizophyllum commune, an underrated edible and medicinal mushroom: farm to industry. Studies in Fungi 10: e004 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0003

Schizophyllum commune, an underrated edible and medicinal mushroom: farm to industry

- Received: 30 August 2024

- Revised: 13 January 2025

- Accepted: 14 January 2025

- Published online: 25 April 2025

Abstract: Schizophyllum commune is an edible mushroom in tropical and subtropical regions. This fungus has gained attention due to the presence of enormous bio-modulators that could bring evolutionary changes to the medical world, from anti-cancerous to anti-hepatotoxic, anti-tyrosinase to anti-microbial, anti-tumour to antioxidant, and many more. Despite its vast distribution, high nutritional value, and pharmaceutically important components, S. commune is still considered a wild mushroom in many regions. This article focuses not only on the immune modulators present in it and their mechanism of action but also discusses the alternative cultivation procedure. The primary goal of this study is to increase the acceptability of this fungus in society, thereby eliminating the necessity to rely solely on naturally occurring fruiting bodies to obtain all of the nutritional and pharmacological benefits or for detailed research purposes.

-

Key words:

- Bioactive constituents /

- Cytotoxic activity /

- Immune-modulator /

- Pharmacodynamic profile /

- Schizophyllan