-

Phytopathogenic fungi inflict significant losses on agronomic and horticultural crop production worldwide. This group damages a third of annual food crop production[1], jeopardizing food security, causing economic losses, and increasing global poverty. While most fungal phytopathogens (over 19,000) are known to plant pathologists[2], many are reported to infect a broad host range and manifest different emerging and re-emerging diseases[3,4] across geographic locations[5−8]. Because of these variations in symptomatology and etiology, designing and implementing sustainable disease control and management solutions becomes more complex and challenging, mainly because no specific strategies are available for emerging diseases[9]. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the pathogen’s biology, ecology, pathogenicity, and epidemiology to develop, select, and implement efficient management strategies and mitigate possible crop damage.

Neoscytalidium dimidiatum (Penz.) Crous & Slippers is a predominantly tropical and subtropical fungus belonging to the ascomycete family of Botryosphaeriaceae[10]. Aside from being pathogenic and directly penetrating the host's cuticle[11], it also acts as an opportunistic fungus, causing disease when the host is stressed or wounded. It is also considered one of the most virulent species among several other Botryosphaeriaceae species subjected to pathogenicity studies[12]. Like most members of its family, N. dimidiatum is commonly associated with plants in the tropics and subtropics and has been reported to cause canker, dieback, shoot blight, and fruit rot disease on various hosts. It is well established as an emerging threat to important horticultural crops such as dragon fruit[13], and some trees[14−17]. It has also been isolated from human tissues, causing superficial skin and nail infections, rhinosinusitis, and pulmonary infection, which have been reported in both healthy and immunocompromised individuals[18−20].

The taxonomy and description of Neoscytalidium species[10,21,22] and the fungus’ role as a human pathogen[18−20] have been presented. However, the biology and epidemiology of Neoscytalidium as a plant pathogen have not been reviewed. Hence, this review aims to present the current knowledge on Neoscytalidium as a plant pathogen. This review first provides a brief synopsis of the taxonomic revision of Neoscytalidium species and the synanomorphs of N. dimidiatum. Next, it discusses the biology, pathology, host range, diseases caused by N. dimidiatum, and the factors affecting disease development. Then, the underlying host-pathogen interaction between N. dimidiatum and its hosts is examined. Finally, the review discusses tools and techniques for pathogen detection and identification, as well as the current options for disease control.

-

Neoscytalidium dimidiatum is a taxonomically accepted species within the Botryosphaeriaceae family. Like most members of this taxon, N. dimidiatum is culturally and morphologically described based solely on its asexual morphs. Interestingly, it produces two characteristic anamorphic states called synanamorphs: (1) mycelial or conidial morph, and (2) pycnidial morph, which were described previously as different species by multiple authors prior to DNA and molecular validations[10,21−23].

The botryosphaericeous fungus N. dimidiatum was initially described by its olivaceous-black arthric conidial morph, which may have a central septum as Torula dimidiata Penz. by Penzig in 1882[24]. About 50 years later, Nattrass described its pycnidial morph isolated from plum, apricot, and apple trees, showing die-back symptoms[25]. Nattrass noted that under suitable conditions, the isolates produce single or aggregates of black carbonaceous fruitifications or conidiomata bearing uniseptate conidia with a pigmented central cell, in addition to their usual Torula-like cultural form[25]. Nattrass introduced it as Hendersonula toruloidea Nattrass[25], known by this name for over 50 years until a new revision was proposed.

The polymorphic state of the fungus and its cosmopolitan distribution have contributed to other existing names used to refer to the same species. Such was the case with the Dothiorella mangiferae (H. Sydow & Sydow), described from dead branches of mangoes (Mangifera indica L.)[21]. In 1989, Sutton and Dyko re-examined its stromatic multilocular conidiomata containing pigmented conidia[21]. They concluded that they represented the same mature conidia of H. toruloidea. They then synonymized the two into a newly redescribed Natrassia mangiferae (Syd. & P. Syd.) under the monotypic genus Natrassia B. Sutton and Dyko. This followed the suggestion that H. toruloidea should be put into a separate genus after consultation with the illustrated Hendersonula type species[26]. Sutton & Dyko also described an arthric synanomorph of N. mangiferae, which they referred to as Scytalidium dimidiatum (Penz.) Sutton and Dyko synonymous to T. dimidiata and Scytalidium lignicola Pesante, after noting its Scytalidium-like arthric chains of conidia[21].

Since then, the taxonomic classification of N. dimidiatum has been revised and further elucidated using molecular phylogenetic studies of the species and its close relatives. In 2005, Farr et al. researched the causative agent of cankers on Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii), hypothesizing that N. mangiferae causes it[27]. However, analysis of internal transcribed spacers (ITS-1 and ITS-2) sequences revealed that a new species caused it and that the authentic cultures of N. mangiferae as S. dimidiatum used in the molecular analysis belong to the genus Fusicoccum Corda (the asexual state of Botryphaeria Ces. & De Not. within the Botryosphaeriaceae family). They introduced the name F. dimidiatum (Penz.) D.F. Farr, combining its old name, T. dimidiata, to replace S. dimidiatum and create a polyphyly. When Crous et al. revised the taxonomic classification of Botrysphaeriaceae by examining conidial morphology supported by intergenic sequences (ITS) and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1ɑ) sequences, it was noted that Scytalidium was polyphyletic, since its ex-type strain (S. lignicola CBS 233.57) clustered distantly from the family Botrysphaeriaceae, suggesting its status as an already taxonomically occupied genus[10]. They proposed the Neoscytalidium Crous & Slippers to accommodate F. dimidiatum as Nd. Phillips et al. revisited this classification[22]. They pointed out that the S. hyalinum isolate used in the analysis performed by Crous et al. is linked to the S. hyalinum isotype, which is phylogenetically indistinguishable from N. dimidiatum. They concluded that the two occupy the same taxonomic group. Since S. hyalinum is the older epithet, it was transferred to N. hyalinum (C.K. Camp. & J.L. Mulder), while N. dimidiatum was reduced to synonymy. The conspecificity was also suggested in an earlier study of N. hyalinum, identified as N. dimidiatum isolates from humans and a mango tree[20]. In 2016, Huang et al. pointed out that the older epithet should be used[28]. Hence, dimidiatum (1882) takes priority over hyalinum (1977). Therefore, N. dimidiatum (synonyms: Fusicoccum dimidiatum, Torula dimidiata, Nattrasia mangiferae, Scytalidium dimidiatum, Scytalidium hyalinum, Hendersonula toruloidea) was finally accepted after many taxonomic revisions.

-

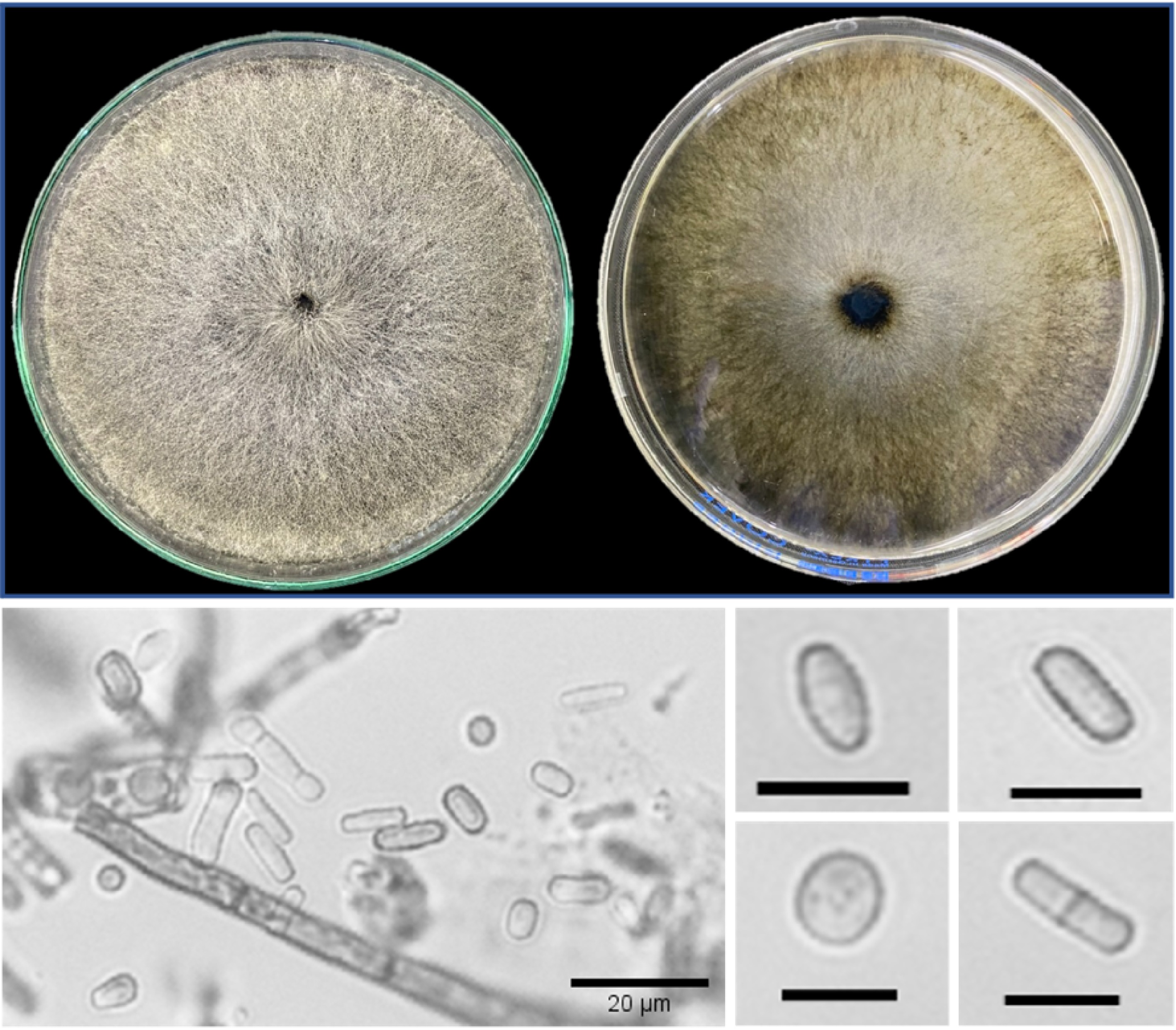

As an important pathogen, understanding the biology and pathogenicity of N. dimidiatum is required to design and implement effective control measures for the diseases it causes. This entails knowledge of its identification to decipher the most vulnerable stages in its life cycle. N. dimidiatum is primarily limited in its morphological characterization by two synanamorphic states, the mycelial morph and the pycnidial morph, due to the absence of a sexual stage. The fungus's characteristic mycelial or hyphomycetous state is the most observed in culture using potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium. Mycelial growth proceeds rapidly in the first three days post-inoculation and appears to be dense, aerial, powdery white to greyish-green that turns dark brown to black (Fig. 1) with age[16,29−33]. The aerial mycelia are branched and septate, constricting and disarticulating, appearing singly or in arthric chains of conidia (arthrospores or arthroconidia) (Fig. 1). The conidia are initially hyaline, then turn dark brown with age, usually ellipsoid to ovoid with cylindrical-truncated ends, thick-walled, and usually with 0 or 1 septum[10,17,23,30,31,34−38]. Moreover, studies have also reported biseptate (two septa) arthric conidia[10,39] and capsule-like, spherical, rectangular, and rod-shape[33,37,40]. On a similar note, N. dimidiatum inoculated on malt extract agar (MEA) also rapidly grows and appears with a white to olive-green color that turns ochraceous yellow with age[31].

Figure 1.

Cultural (left: front, and right: reverse side) characteristics (mycelia become darker after three days), and conidia morphology of 7-day-old Neoscytalidium dimidiatum. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Unlike its mycelial morph which commonly forms in culture, the pycnidial state of N. dimidiatum is only successfully observed in water agar supplemented with sporulation-promoting substrates (e.g. pine needles, carnation leaves, corn straws, and horsetail twigs) within 3 to 4 weeks post-inoculation[10,23,30,32,34,36,40,41]. The pycnidia are stromatic and immersed within the substrates, dark brown to black, irregularly shaped to ovoid, and with a globose base[30,41,42]. Furthermore, it bears hyaline conidiogenous cells and is intermingled with paraphyses[15,31,41]. The conidia produced from the conidiogenous cells are characteristically hyaline, rod-shaped or round-shaped with a rounded apex and truncated base, and become uni- or bi-septate with age, which may have a darker central cell than the end cells[15,23,30−32,34].

-

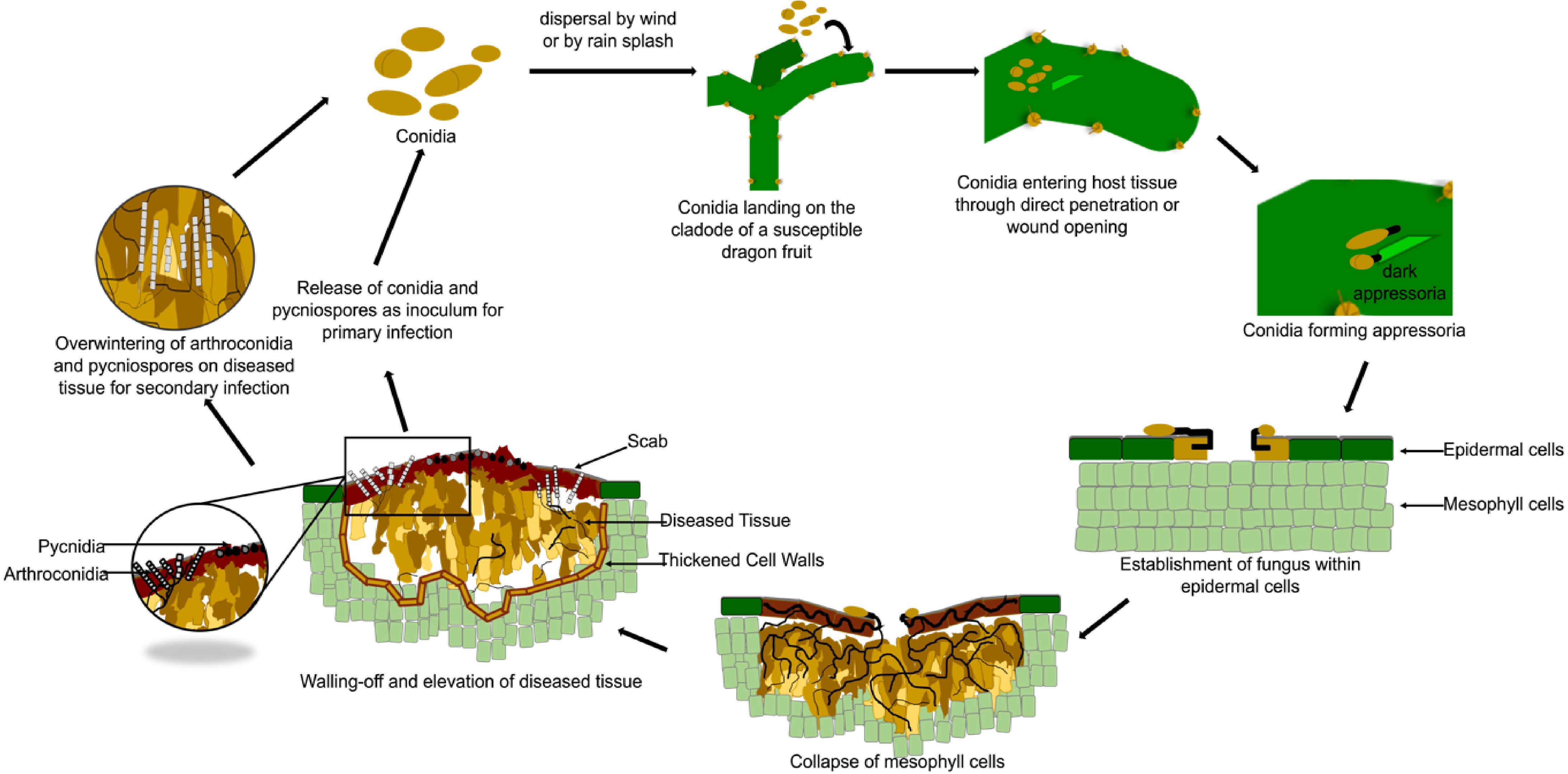

Infection by Neoscytalidium dimidiatum as an opportunistic pathogen occurs primarily through openings from freezing, heat stress, pruning wounds, mechanical injuries, or natural openings in the flowers, fruits, leaves, and shoots[15,29,43]. In dragon fruit canker disease, where the life cycle of N. dimidiatum has only been recently described (Fullerton et al.), it is initiated when dark appressoria form from surface hyphae growing from conidiospores[11]. When the fungus has successfully established itself within the epidermal cell, the host tissue manifests reddish-brown necrotic spots (Fig. 2). The collapse of infected cladode tissues follows this due to the clearing of mesophyll cells. As the lesion progresses, the cells adjacent to the collapsed tissue develop thickened walls, isolating the diseased area and forming elevated scabs. These scabs appear yellow, reddish, or gray, bearing dark pycnidia extruded with pycniospores available for dispersal by rain or wind[11]. Moreover, the arthroconidia and pycniospores on infected tissues may be overwintered and carried over for secondary infections[44].

Figure 2.

The disease cycle of the stem canker disease, caused by Neoscytalidium dimidiatum in dragon fruit.

N. dimidiatum can easily enter the host through natural openings or wound cuts. However, it can also enter the host tissue without these openings and wounds. For instance, mannanases, ɑ-glucosidase enzymes, and the PL3 family of pectate lyases are also well-developed for N. dimidiatum, which may aid in infecting its hosts' fruits and soft tissues[43]. In eucalyptus trees, the fungus is known for disrupting the vesicular tissue functions of the host[14,45]. The hyphae of N. dimidiatum can invade the bark cambium and wood, resulting in the necrosis and brown discoloration of the wood and vascular tissues. This hinders the plant's water and nutrient absorption capabilities and transport functions[46,47]. Sooty spores sometimes develop below or at the surface of the bark[15,16,29].

-

Since its first association with diebacks of plum, apricot, and apple trees as H. toruloidea in Egypt[25], N. dimidiatum has been detected and identified in a broad host range across many tropical and subtropical countries. It is an established causal agent of many woody tree diseases. However, it is also reported as an emerging threat to woody vines, shrubs, and herbaceous plants. It causes diseases such as cankers, diebacks, shoot blights, leaf blights, fruit rots, root rots, and gummosis. Notably, these symptomatology overlap with other biotic and abiotic stresses. For instance, yellowing and browning of foliage, associated with canker and abundant gumming, are also characteristic of boron toxicity[23]. This makes the diagnosis of N. dimidiatum infection through symptoms alone unreliable.

The most striking visual symptoms of N. dimidiatum infection of woody trees are brown to black cankers in the trunks and branches. These are often accompanied by yellowing, wilting, and browning of leaves and eventual tree decline. These were recorded in Eucalyptus camaldulensis in Iraq[14] and in North America[48], in mango in Australia[49], and in Populus nigra, P. sylvestris, and P. eldarica in Türkiye[36]. Additionally, black stromata bearing fungal spores are apparent beneath the bark of most infected trees. Such were noted in re-grafted Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck in Italy[15], in C. clementina, C. paradisi, and C. maxima in Jordan[29], and in Juglans regia L. (walnut) in Türkiye[16]. Aside from symptoms on their stems and foliage in some fruit-bearing trees, the cankers may extend to the fruits that further develop into fruit rots. Hull rots of almonds (Prunus dulcis) associated with shoot blight have been described from an orchard in California, USA[23]. In Malaysia, small cankers in Psidium guajava fruit coalesce and cover its entirety, making it soft and rotten[50].

The characteristic dieback and blight disease caused by N. dimidiatum infections are primarily due to its role in disrupting vesicular functions in the host, which advances to detrimental conditions of the plants[14,45]. Such were the cases of internal wood necroses that caused grapevine productivity declines in Egypt[51], California[52], and Türkiye[40]. Such was also the case of plums in Tunisia, which exhibited shoot blight with scorching leaves and wilt branches[53]. Leaf blights associated with N. dimidiatum have also been observed in shrubs and herbaceous plants. Kee et al. observed yellow to brown blights in Sansevieria trifasciata in Malaysia[34], and Chang et al. in Cattleya × hybrid in Taiwan, China[54]. Irregular reddish brown to black lesions with black pycnidia on the leaves were also reported in Malaysia's white spider lily (Hymenocallis littoralis)[32]. The fungus is also reported in Türkiye as the causal agent of a novel blight disease of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), manifesting its symptoms in all aerial parts of the plant and extending to the roots, causing rots, internal necrosis, and eventual death of the plant[55].

Root rots have also been associated with N. dimidiatum infection, showing symptoms in several trees and non-tree hosts. The first worldwide report of Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) infected by the fungus in Türkiye exhibited canker, shoot blight, and root rot symptoms[17]. The same symptoms were reported in Australia's common fig (P. carica)[49]. In Brazil, root rots caused by the fungus have been reported in physic nut (Jatropha curcas), which also showed collar rot symptoms[41], in sweet potato (cultivar Canadense) as postharvest rot[39], and in cassava[56].

Excessive gumming is associated with infected plants with physical injuries from pruning wounds or natural causes. For instance, abundant gumming was observed in citrus orchards[15,29] and almond orchards[23] that are routinely pruned, and in mangrove trees (Avicennia marina and Rhizophora muronata) in Southern Iran, the first worldwide report of mangroves as host to the fungus[57]. These mangroves are occasionally subjected to cracks and breaks from strong winds. Variabilities in symptoms are also displayed among species of the same genus and even in the same species infected by N. dimidiatum. Dieback symptoms from S. scytalidium infection were only manifested in Ficus spp. (F. benghalensis, F. carica, and F. retusa), in Thespesia populnea, Delonix regia, and P. petrocarpum, in Oman[58]. This contrasts with the canker and dieback symptoms and the erumpent fungal growth beneath the periderm of F. nitida and F. benjamina trees in Egypt[18]. Moreover, root rots in P. carica in Australia[49] were not observed in infected Populus spp. from Türkiye[36].

The host range of N. dimidiatum has widened with new reports of this fungus associated with fig fruit rot[59], Disocatus ackermannii brown spot[60], Lelyand cypress dieback and canker[61], postharvest disease of pears[62], leaf zonate spot of aloe vera[63], root collar canker on Jacaranda mimosifolia[64], euphrates poplar stem canker[65], pineapple leaf spot[66], mango dieback[67], corn blight[68], leaf blight of Clivia miniate[69], olive canker and leaf scorch[70], and apple dieback and canker[71].

-

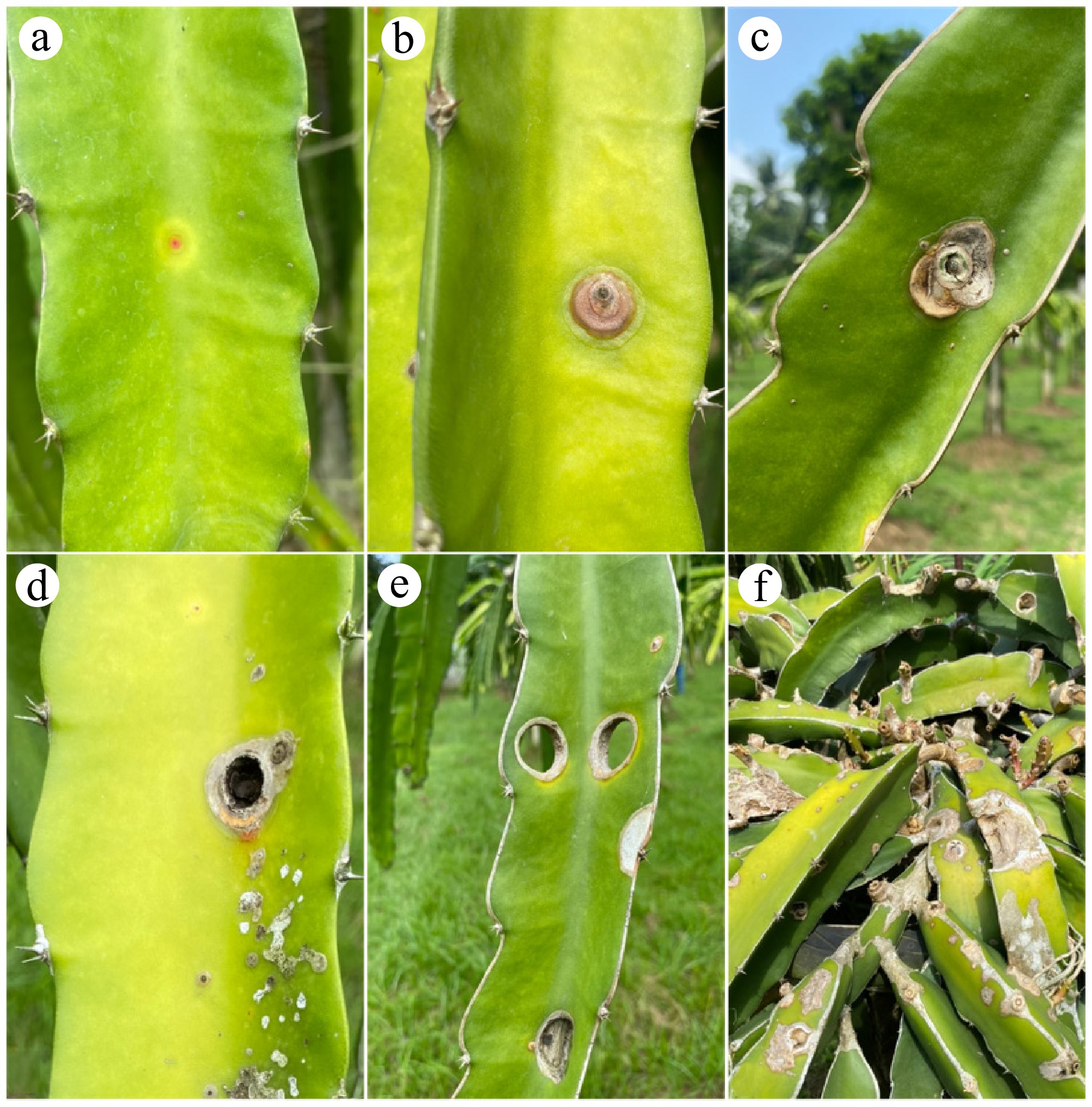

All commonly known Selenicerus species (syn. Hylocereus species) are susceptible to N. dimidiatum[72] (Table 1). In the three commonly cultivated dragon fruit species—S. undatus, S. monacanthus, and S. megalanthus—N. dimidiatum causes stem and fruit cankers (Fig. 2), posing a growing and significant threat to productivity and fruit quality[10,13]. Neoscytalidium dimidiatum has been recorded in China[37,38,73], Malaysia[31], the Philippines[33], Taiwan (China)[74], the United States of America[75], Israel[76], Thailand[77], Ecuador[78], India[79], and, most recently, Brazil[80]. A comparison of the dragon fruit species, plant part (organ), and disease symptoms by N. dimidiatum is presented in Table 1. All reports across these regions indicate that infection starts as minute chlorotic spots, coalescing to form round, orange to brown, or reddish, watery lesions occasionally bordered by an orangish to brownish halo (Fig. 3). Dry weather could lead to cladode-infected tissues falling off, resulting in 'shot-hole symptoms'. Infected S. undatus were also reported to exhibit brown spot disease[81], fruit internal brown rot[38] in China, and internal black rot in Israel[76]. However, it is difficult to compare the degree of susceptibility among Selenicerus species since all, except one assay done in the Philippines[33], did not compare severity across these Selenicerus species, and studies have different methods or inoculation procedures. These comparative assumptions, however, must be considered carefully due to the possible natural variability of the isolates and the phenology of the hosts. Nevertheless, these highlight the need for the comparative analysis of fungal isolates for differences in virulence and pathogenicity. It is also important to note that N. dimidiatum is often found to be hosted by various plants within the same geographic locations, which may suggest the local establishment of the fungus and the occurrence of cross-infection events.

Table 1. Comparison of Neoscytalidium dimidiatum species host species susceptibility, plant organ infected, and disease symptom.

Country Dragon fruit species Plant organ Disease/symptom Ref. Israel S. undatus Flower/fruit Internal black rot [76] Malaysia S. polyrhizus Stem Canker [31] USA (Florida) S. undatus Stem and fruit Canker [75] USA (South Florida) Selenicerus species Stem and fruit Canker [44] Thailand S. polyrhizus Stem Canker [77] Ecuador S. megalanthus Stem Canker [78] China S. megalanthus Stem Canker [73] Brazil S. costaricensis Stem Canker [80] Philippines S. monacanthus Stem Canker [33] Philippines S. undatus Stem Canker [33] Philippines S. megalanthus Stem Canker [33] Costa Rica S. costaricensis Stem Canker [82] India Selenicerus species Stem Canker [79]

Figure 3.

Development of stem canker disease caused by Neoscytalidium dimidiatum on Selenicereus spp. cladodes. Symptoms start as: (a) minute, reddish, chlorotic flecks, (b) that become raised, (c) and then collapse, forming the canker symptom of the disease, (d) black pycnidia may be produced, (e) the diseased tissue can fall off, forming the 'shot-hole symptom'. (f) Productivity is greatly affected in severely infected cladodes.

-

The growth of N. dimidiatum is primarily associated with environmental stresses that predispose plants to infection. Reportedly, N. dimidiatum infections are observed in susceptible plants predisposed to hot and dry weather conditions. For instance, the Scytalidium wilt of grapefruits (C. paradisi Macf.) is consistently observed after experiencing extreme temperatures above 45 °C in Israel[83]. The dieback of Albizia lebbeck and other trees in Oman was also manifested after a heat period (highest record of 45 °C) and water stress, which caused cracks and breaks on its thin bark[58]. Sooty cankers in eucalyptus, poplar, and various fruit and ornamental trees in Iraq developed after several months of high temperatures, reaching up to 42 °C. These observations are corroborated in in vitro studies on a related pathogen, Scytalidium lignicola. Sadowsky et al. inoculated grapefruit saplings with S. lignicola and showed that hot temperature (34 °C) is a prerequisite for successful infection of susceptible hosts[84]. Poplar and eucalyptus saplings exposed to 32 and 40 °C heat stress have sustained canker progress 5 d post-inoculation[47].

The preference of the fungus for higher temperatures is also evident in conidial and mycelial temperature growth assays. Germination of conidial N. dimidiatum isolates from dragon fruit in Florida, USA, is significantly reduced at constantly low temperatures (15 °C or lower) but enhanced when temperatures exceed 22 °C[44]. Moreover, mycelial growth rates were identified to be faster at an optimum temperature of 32 °C for these isolates. Similar findings were reported for the conidial isolates from dragon fruit in Taiwan, China, mango in Brazil, and almonds in California, which exhibited higher germination rates at 35 °C and had faster mycelial growth rates between 25 and 35 °C[12,23,85]. These results support the high incidence of infections in warm climates, where the persistence of inoculum, spore maturation, and host invasion are favored.

However, high-temperature ranges must not always be translated as a good predictor for infection. Nouri et al. observed N. dimidiatum infections in almonds during winter seasons in California[23], which were otherwise reported to be exclusive only in the summer months[86]. They suggested that this shift may be partially attributed to climate change, highlighting that the region now experiences a warmer and drier climate, with an average temperature of 13.9 °C, compared to 40 years ago. Exacerbation of pathogen aggressiveness is also linked to water stress and physical injuries via extensive pruning or wounding, which has been demonstrated in other studies[15,29,57,58]. Nonetheless, these findings recognize the relevance of the effects of climate change, specifically global warming, in predisposing susceptible host plant infection and promoting the increase of growth and germination rates of N. dimidiatum inoculum.

As temperatures rise and humidity levels fluctuate, these changing conditions may create a favorable environment for developing N. dimidiatum, potentially leading to more widespread and severe levels of the disease. In a field in Pangandaran, West Java, Indonesia, stem canker was reported to affect 100% of plants, with severity reaching more than 50%[87]. Hence, climate change not only promotes the spread of the pathogen but can also exacerbate the incidence and severity of dragon fruit stem canker.

-

The molecular mechanisms of N. dimidiatum-host interactions are not widely reported across a broad host range and are still in their infancy. In an initial investigation conducted by Pan et al. on the immune responses of dragon fruit against N. dimidiatum infection, essential proteins have been identified to be involved in maintaining homeostasis and defense responses[88]. Upregulations of chloroplastic and mitochondrial proteins suggest the roles of these organelles during infection. Photosynthesis-related proteins had increased expression, such as chlorophyll a-b binding proteins and ribulose carboxylate-bisphosphate proteins, which are necessary as biological needs for photosynthesis. Auxin and abscisic acid were also elevated during the fungal invasion, which correlated to the putative post-transcriptional upregulation of proteins involved in their synthesis pathways (ABP, ARP4, and ASP2). This suggests their roles as stress signals during pathogen invasion, similar to ABA, which typically acts as a secondary messenger for stomatal closure[89]. Pan et al. also reported the increased expression of reactive oxygen species-related proteins, which implies the involvement of synthesis and degradation of reactive oxygen species in the defense against N. dimidiatum invasion[88].

In 2019, Xu et al. performed a transcriptome-wide high-throughput RNA sequencing to map the expression profile of resistance genes in N. dimidiatum-infected H. polyrhizus stem tissues[90]. They identified a unigene annotated to the respiratory burst oxidase homologs (Rboh) membrane-bound enzyme family, which may be critical in ROS production during infection response. In addition to this, they have also reported differential gene expression (DEGs) of 23 defense-related genes. These were ontologically annotated in the cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNGC) channel family, calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK) family, and calmodulin and calmodulin-like (CaM/CML) protein family, and leucine-rich repeats (LRR) family of plant disease resistance genes, which play important roles in hypersensitive response to biotic and abiotic stimuli like defense-related gene induction or programmed cell death[90]. A year later, the same researchers reported a comprehensive overview of the roles of LRR resistance genes at the transcriptional level[91]. The genes have been shown to follow different expression profiles under different infection stages and tissue-specific expression profiles to confer a response to the infection[91]. These molecular investigations of dragon fruit response to the infection also warrant elucidation in other N. dimidiatum pathosystems to further research on developing resistant lines.

-

Cultural and morphological characterizations may offer quick and inexpensive methods in N. dimidiatum identification. However, these have caused confusion regarding the taxonomic history of the fungus, as discussed above. Control of diseases may also be misappropriately applied if pathologists rely solely on symptomatology for diagnosis. For instance, N. dimidiatum hull rot of almonds in California may have been overlooked due to its resemblance to Rhizopus stolonifer and Monilinia fruticola hull rot[23,92]. A DNA-based approach, specifically PCR-based assays, for identifying N. dimidiatum remains the most leveraged method. Amplicons are amplified using primer pairs designed for ribosomal DNA (rDNA) internal transcribed spacer (ITS), β-tubulin (Bt2), and elongation factor-1α (EF1α) sequences. The ITS1/ITS4 and ITS4/ITS5 primer pairs designed by White et al.[93] are widely used for identifying and validating N. dimidiatum isolates from various hosts[15,33,34,37,38,41]. Similarly, the primer pairs Bt2a/Bt2b[94] and EF1–728 F/EF1-986R[95] are also used for identity confirmation of the fungus[10,23,40,44,96,97]. No other novel approaches for the identity confirmation of the fungus have been pursued so far.

-

High disease incidence and severity of N. dimidiatum infection have been associated with poor field sanitation. Hence, curative procedures such as pruning and destroying diseased plant parts must be accomplished to reduce the threshold or eliminate possible sources of inoculum that may infect healthy plants[11,31,37]. Preventive practices, such as proper nutrition, may also be implemented to increase plant vigor and reduce the risk of pathogen infection[98]. However, care must be considered with these practices since these may cause harm to the plant when improperly executed using unsterile tools or when N. dimidiatum is in its advanced life stages[96].

Chemical fungicides are also known to control plant diseases caused by N. dimidiatum infection. These are currently considered the best practices for mitigating dragon fruit canker diseases. Azoxystrobin (200 g/L, FRAC code 11) + difenoconazole (124 g/L, FRAC code 3) have proven effective against stem canker[99]. Pyraclostrobin (effective concentration or EC at 250 g/L, FRAC code 11) reduced stem canker incidence to 85% in field trials[100]. Fluazinam (FRAC code 29) provided 93% control in field conditions, while tebuconazole (FRAC code 3) showed high efficacy only in detached fruits[101]. The few available formulations may cause alarm since they promote the reuse of fungicides with similar modes of action, consequently increasing the risk of developing fungicide resistance among the pathogen population[44]. Aside from this, alternative formulations[102], e.g., botanicals and biological control agents, are also encouraged since conventional/synthetic fungicides contribute to environmental pollution that most likely translates to harmful human effects.

Although still requiring application and testing on field scales, in vitro treatments with alternative chemical formulations have shown promising antifungal efficiency in inhibiting N. dimidiatum growth. Chitosan-silver nanoparticles inhibited N. dimidiatum growth, although better antifungal activity was recorded in synergy with the fungicide zineb[103]. High efficiency of control of dragon fruit brown spot disease was also exhibited by nanosilica-oligochitosan particles[104] and alginate-stabilized Cu2Co-Cu nanoparticles[105]in in vitro assays. Citronella oil (1.25 μL/mL) also inhibited fungal growth by ~85%[33]. Moreover, biological control agents have also been shown to exhibit control of N. dimidiatum growth. A biopesticide with Bacillus subtilis QST strain (2 mL/400 mL) has a 100% growth inhibition efficiency against N. dimidiatum[33]. In addition to the fungal growth inhibition effect, a 2-fold cell-free supernatant of B. subtilis supplied with sodium bicarbonate (1% weight/volume) also induces defense response mechanisms in dragon fruit against stem brown spot disease[106]. Several fungal strains have also been used as biological control agents of N. dimidiatum. The study by Intana et al. showed that Trichoderma asperellum K1-02 effectively inhibited the mycelial growth of N. dimidiatum by parasitizing the pathogenic fungus through the production of cell wall-degrading enzymes[107]. A laboratory-scale assessment was further made, and results indicate that the biological control agent reduced disease development in dragon fruit cladodes[107]. Trichoderma asperelloides PSU-P1 was also found effective against N. dimidiatum in both the in vitro and stem canker assay[107]. Nguyen et al. observed similar results in in vitro and pre-treatment potted experiments when using 15 isolates of Trichoderma species against brown spot caused by N. dimidiatum on dragon fruit[108]. These studies showed the potential of Trichoderma species to be a biological control agent for N. dimidiatum, and further research would be needed to underpin its efficacy under field trials.

The use of resistant varieties remains the most durable approach in the management of diseases caused by Neoscytalidium dimidiatum. However, there is a lack of information on resistant Selenicereus species and genotypes. Nonetheless, there are currently reports on the ongoing development of plant lines resistant to N. dimidiatum infection. Initial studies on the expression of resistance genes of N. dimidiatum-infected dragon fruit have recently been described[88,90,91]. Additionally, systemic acquired resistance (SAR) from pre-treatment with salicylic acid has been shown to reduce sooty canker disease in E. camaldulensis trees[14]. Understanding the genetic and molecular biology of the N. dimidiatum pathosystem needs to be further addressed and established to aid in designing disease-resistant lines of its plant hosts.

-

This research did not require ethical clearance.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Peja R Jr., Duka IM, Balendres MA; drafting of the manuscript: Peja R Jr.; review, and editing of the manuscript: Duka IM, Balendres MA. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

We thank the Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Research (BAR) for the support provided for the dragon fruit pathology research at the University of the Philippines Los Baños between 2019−2022.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Peja R Jr., Duka IM, Balendres MA. 2025. Neoscytalidium dimidiatum, a plant killer: a review. Studies in Fungi 10: e011 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0011

Neoscytalidium dimidiatum, a plant killer: a review

- Received: 06 January 2025

- Revised: 11 April 2025

- Accepted: 10 May 2025

- Published online: 24 June 2025

Abstract: Phytopathogenic fungi infections can harm plant hosts' physiology, phenotype, and productibility. An emerging threat to agricultural productivity is Neoscytalidium dimidiatum, an opportunistic yet destructive fungus belonging to the family Botryosphaeriaceae. This fungus infects woody trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants, mainly in the tropics and subtropics. It causes diseases, including cankers, diebacks, shoot blights, leaf blights, fruit rots, root rots, and gummosis. Nevertheless, the name N. dimidiatum is perhaps more globally associated with 'stem canker' in dragon fruit (Selenicereus spp.). Pathogen detection is initially done with symptom recognition in the field and confirmed through laboratory morphological and molecular (DNA-based assay) analysis. Because the pathogen thrives well in hot and humid conditions, climate change is an important factor in the rapid spread of the pathogen and severe symptom development in different crops. Effective disease management strategies at the field or commercial farm level have yet to be implemented, but recent studies have yielded promising results. Sanitation of infected debris, increasing the vigor of plants, and fungicide application remain the best available management and control of stem canker caused by N. dimidiatum. Nevertheless, identifying and developing sustainable disease control measures remains important. This review paper focuses on the current knowledge of the taxonomy, biology, pathogenicity, host range (with emphasis on dragon fruits), detection, and identification of N. dimidiatum and its current disease control measures.

-

Key words:

- Botryosphaeriaceae /

- Dragon fruit /

- Selenicereus /

- Stem canker