-

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) is an extremely important fruit crop worldwide, generating substantial financial value for growers across the globe. Because of its nutritional value, short life cycle, economic benefits, and other characteristics, it is cultivated on a large scale worldwide[1]. According to the report of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, globally, strawberry plants were cultivated on a total of 389,665 hectares in 2021, representing a total production of approximately 9,175,384.43 metric tons[2]. Among the countries producing strawberry, In the United States, California alone planted 16,303 ha of strawberries. This hectarage resulted in a total yield (fresh + processed) of 1,081,817,234 kg fruit and a yield of 66,355 kg fruit per hectare[3]. These delicious fruits are primarily grown in temperate regions such as China, Germany, Iran, Poland, Spain, Turkey, and the United States. However, other varieties, such as Sweet Charlie, Winter Dawn, Barak, Gili, Hadar, and Sabrina, can also thrive in mild tropical and subtropical regions[4]. In India, strawberry cultivation is traditionally associated with hilly areas. However, successful cultivation has also occurred in flat regions, including temperate regions in the north, subtropical plains, and high-altitude tropical areas. Uttarakhand, particularly Nainital, Dehradun, in Uttar Pradesh Jhansi; Maharashtra's Mahabaleshwar and the plains of Pune, Nashik, and Sangali; and the Kashmir Valley, Bangalore, and Kalimpong in West Bengal, are major strawberry cultivating states in India[5].

The most commonly grown commercial variety of strawberry originated approximately 300 years ago through the hybridization of four different global cultivars: Fragaria viridis, F. iinumae, F. nippiconica, and F. vesca. This domesticated crop is an allo-octoploid with genomic complexity that often necessitates studying diploid relatives to better understand its genetic makeup[6]. Commercial strawberry cultivars were established approximately three centuries ago as a result of accidental crossbreeding between F. chiloensis and F. virginiana cultivars. Early efforts in crossing and breeding these strawberry plants were made by Thomas Knight in his personal gardens in Britain in 1817[7]. Over the past two centuries, farmers in the North American region have also delineated the prominent tools and breeding techniques available for improving their crops. Strawberries are eminent for their high nutritional attributes and flavors, similar to those of other berry fruits (blackberries, blueberries, and raspberries), which have high antioxidant and anthocyanin contents. Strawberry fruits are often used by patients with cardiovascular diseases and diabetes due to their lower glycemic index than other fruits. These fruits fall under the category of superfruits because they boost metabolism and provide essential minerals and antioxidants to the body[8]. Strawberry crops are susceptible to infections caused by various pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and viruses. Among these, fungi are particularly destructive and cause significant losses of up to 20%−50% in developing countries due to inadequate storage and transportation facilities. These robust pathogens can affect whole plants, including fruits, leaves, roots, and stems, both in the field and during postharvest stages[9]. Several fungal pathogens, including Botrytis cinerea, Colletotrichum spp., Rhizopus spp., Fusarium spp., and Phytophthora spp., have been identified as the major disease-causing agents of strawberry fruit rot and causes 64.6%, 17.4%, 9.6%, 4.6%, and 3.6% loss of fruits respectively[10]. Studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Exhibited strawberry fruit rot diseases with causal agents reported in various countries.

Diseases Pathogens Symptoms Countries Ref. Anthracnose Colletotrichum acutatum Dark and sunken spots appeared on both green and ripe fruit, which can enlarge and become hard, dry, and shriveled, eventually forming mummified fruits. USA [11] Colletotrichum siamense China [12] Gray mold Botrytis cinerea Soft light brown lesions, often starting at the stem end or other diseased parts or where the fruit contacts with soil, eventually turning into a mummified, gray, powdery mass. China [12] Botrytis fabiopsis China [12] Botrytis fragariae USA [13] Leather rot Phytophthora cactorum Infected green fruit develop dark-brown, firm spots that can expand and cover the entire berry. The infected areas become tough and leathery. Florida [14] Phytophthora nicoteanae Phytophthora citricola Poland [15] Black rot/Leak rot/

Rhizopus rotRhizopus stolonifera Water-soaked, discolored spots that rapidly enlarge, causing the fruit to become limp, brown, and leak its contents, often covered with a white mycelium with black sporangia. Italy [16] Rhizopus nigricans China [17] Penicillium fruit rot Penicillium citrinum A soft, watery rot with a sharp boundary between healthy and disease tissue, sometimes showing blue-green spore masses and an earthy, musty odor. Egypt [18] Penicillium digitatum China [19] Aspergillus fruit rot Aspergillus flavus Fruits become discolored, water-soaked spots that become tan to dark brown and may eventually mummify and become black. Egypt [19] Aspergillus niger Strawberry fruit rot Calonectria fragariae Lesions may be surrounded by pale-orange colored spore masses. Brazil [20] Sour rot Geotrichum candidum Water-soaked, soft rot, a sour smell, and white mycelium on the fruit surface. China [21] Strawberry fruit rot Neopestalotiopsis iranensis sunken, tan lesions with abundant black spores appear on the fruit surface. Iran [22] Neopestalotiopsis mesopotamica Alternaria fruit rot Alternaria alternata Sunken, dark lesion appears near the calyx end of the fruit. These lesions are covered by a dark green velvety growth. Infected fruit becomes soft and

shriveled.Oman [23] India [24] China [12] Alternaria tenuissima China [12] Blossom blight Cladosporium cladosporioides Infections first appear as soft, sunken, water-soaked lesions on the fruit, later a grayish, fuzzy coating or web produced by the fungus; infected fruit can shrivel and become dry and mummified. Korea [25] Cladosporium tenuissimum Fusarium fruit rot Fusarium graminearum Fusarium wilt primarily affects the plant and not the fruit directly, but infected plants may have reduced fruit production. Infected berry eventually desiccate, turning hard and black. China [12] Fusarium incarnatum Fusarium ipomoeae Fusarium proliferatum Among them, the pathogen that poses the greatest threat is Botrytis cinerea, which causes gray mold disease, and Colletotrichum spp., which causes anthracnose[16]. Under favorable conditions, the economic implications for producers are severe, as the disease causes the decay of fruit and vegetative tissue, and contamination can reach as high as 80%, leading to substantial fruit losses[26]. To overcome these issues, it is necessary for farmers to implement influential disease management techniques to save their crops and minimize financial losses. To overcome fungal infections in strawberries, many management strategies have been used, and the most common of these are synthetic fungicides and physical methods[27]. However, the extensive application of chemicals may lead to several drawbacks, such as high costs, residual toxicity, environmental issues, difficulty handling, health issues for humans, and the emergence of fungicide-resistant fungal strains[16]. Consequently, it is necessary to investigate alternative plant-based preservatives that are safe, biodegradable, and environmentally friendly[14]. Previous reviews on strawberry fruit rot management have focused on conventional, physical, and biological approaches[26,28]. These reviews did not cover molecular techniques, novel management strategies to reduce fungal infection in strawberry fruits, or omics approaches applicable to a wide range of hosts. In this review, the current status of fungal infection in strawberry fruit rot is addressed, including associated yield losses, and an overview of various management approaches is provided, including chemical, physical, and biological methods, as well as their advantages and disadvantages. Additionally, molecular studies conducted on fruit rot-causing pathogens are discussed in order to identify knowledge gaps and highlight future research perspectives.

-

Strawberry fruit rot diseases are caused by several fungal pathogens (Table 1). These exterminatory fungal enemies lay in wait in the shadows and are ready to infect the strawberry crops. Notorious foes, such as Botrytis cinerea (gray mold), Colletotrichum spp. (anthracnose), Phytophthora spp. (leather rot), and Rhizopus spp. (black rot) wreak havoc on precious red jewels (strawberry fruits) and may lead to substantial economic losses in strawberry yield[29]. These terrible fungi thrive in warm and humid environments, and their insidious spores invade fresh fruits at different stages of growth, destroying them in their wake[30]. Growers and researchers must arm themselves with knowledge of these prevailing notorious villains to protect their crops from these malicious antagonists. The symptoms of fruit rot diseases vary depending on the specific pathogen involved. Infections by Botrytis cinerea occurr in gray mold, with the affected fruits exhibiting a fuzzy gray to brown decay. Yield losses of up to 80% of the total fruits produced due to gray mold disease occur because the pathogen is resistant to fungicides[31]. Colletotrichum spp. infections can lead to anthracnose symptoms, which are characterized by small, sunken, dark lesions on the fruit surface and 50% yield losses in the field[32]. Phytophthora cactorum causes rapid collapse of the fruit, creating soft, water-soaked patches known as leather rot, causing a yield loss of up to 40%[31]. Rhizopus spp. infections result in soft rot with white fluffy mycelia covering the fruit, causing the fungus to loosen its steadiness and become water-soaked and exudate juice, even at slight pressure. This results in white fluffy cotton, similar to mycelial growth, with black sporangia forming on severely infected fruit[33]. Fusarium oxysporum and F. graminearum, have been reported to cause fruit rot in strawberries. These pathogens primarily infect fruit through wounds, resulting in secondary infections and rotting[9]. Penicillium expansum is the main cause of blue mold disease, as is common in other species. However, this is a sporadic disease and is locally important. Several important deteriorating stored fungi, such as Alternaria spp., Aspergillus spp., and Cladosporium spp., are other causes of postharvest decay in strawberry fruits[16]. These strawberry fruit rot diseases pose a significant threat to crop yields and profitability worldwide. Infected fruits have low market value due to their appearance and altered taste. Furthermore, the presence of these fungi may lead to secondary infections, which can spread through neighboring healthy plants, resulting in intensive damage to strawberry fruits. On-time identification and effective management strategies are crucial for minimizing the impact of these diseases on strawberry yield. This manuscript aims to shed light on the disingenuous behavior of fruit rot diseases, empowering growers and researchers with essential information to combat this exterminatory hazard.

-

Ongoing research endeavors have evaluated and become aware of the problems associated with these ailments, as well as their eradication and management techniques. Several approaches and strategies have been used to overcome strawberry fruit rot diseases[34]. Conventional methods such as field surveys, data collection, isolation, microscopic examination, and identification of causal agents have been combined with advanced molecular techniques such as PCR-based assays, DNA sequencing, and next-generation sequencing. These tools provide quality insights into the diversity of pathogens, mode of action, and genetic variations associated with various strawberry fruit rot diseases[35]. The key finding of these significant studies is the identification and characterization of several pathogens responsible for diseases, including fungi (e.g., Botrytis cinerea, Colletotrichum spp., Phytophthora spp., Rhizopus spp., etc.), bacteria (e.g., Xanthomonas fragariae, Pseudomonas spp.), and other pathogenic agents[36]. Recent studies elucidated the etiology, epidemiology, and effect of environmental factors on disease development[16]. These investigations provide a comprehensive understanding of how to combat strawberry fruit rot diseases and develop sustainable disease management strategies for strawberry cultivation[34]. The study of epidemiology and risk evaluation has revealed the strength of agronomic practices, environmental impacts, and fruit maturity on disease incidence and disease severity[37]. Furthermore, current research has explored the potential of cultural practices, plant resistance genes, fungicidal treatments, and biocontrol agents for mitigating fruit rot diseases. These insights suggest the convenience of developing integrated disease management strategies that can strongly reduce the disease incidence and economic loss of strawberry fruits[29].

-

Strawberry fruit rot diseases predominantly affect the overall health and productivity of strawberry plants. Effective management of fruit rot diseases is needed to enhance the sustainability and productivity of strawberry cultivation[16]. Integrated approaches, including cultural, biological, and chemical control methods, may play vital roles in the successful mitigation of these diseases[38]. Cultural practices such as disease-free plants, crop rotation, mulching, good sanitation, and proper irrigation practices play a significant role in minimizing disease incidence and severity[39]. In addition, biological control agents such as antagonistic microorganisms and beneficial fungi can also be used to suppress disease-causing pathogens[40]. Furthermore, the judicious application of conventional fungicides, in combination with other management techniques, results in the effective management of fruit rot[11]. By integrating several approaches, growers can develop suitable disease management plans that are sustainable and effective for every measure, ultimately leading to enhanced quality and quantity of fruits. This approach is promising for overcoming the problems posed by fruit rot diseases in the strawberry industry.

Integrating conventional and chemical-based strategies: highlights and challenges

-

Conventional and chemical-based approaches for fruit rot management involve combining traditional and chemical methods to effectively control fruit rot diseases in strawberry production. This technique recognizes the limitations of solely relying on either conventional or chemical-based strategies and seeks to find a balanced and sustainable solution. By integrating these approaches, growers can optimize the yield and quality of fruits while reducing the negative impacts on the environment and human health.

Agronomic and horticultural practices

-

Throughout history, fungal contagion in strawberry cultivation has been managed through various agronomic and horticultural techniques. First and foremost, sanitation and hygiene techniques play pivotal roles in preventing the spread of these diseases[39]. Regular pruning and disinfection of tools, equipment, and containers used for harvesting are needed to further minimize the risk of disease spread. Growers can effectively prevent the spread of strawberry fruit rot pathogens by cleaning and sanitizing growing areas[39].

Choosing the proper irrigation system can also play a role in minimizing fungal infections, e.g., through drip irrigation and micro-sprinkling, preventing the transmission of pathogens and reducing water droplets on the fruit surface, which helps to limit fungal infections[41]. Furthermore, the characteristics of the canopy, such as its density and spacing, can also affect the presence of fungal pathogens. For example, dense canopies resulting from nitrogen fertilization can favor certain types of fungal infections, while shorter plant spacing can lead to a greater incidence of Botrytis cinerea[42]. Proper pruning and plant spacing also play vital roles in preventing these diseases. Crop rotation is another crucial technique that can effectively combat these diseases, helping to disrupt the disease cycle by decreasing the inoculums of pathogens in the soil. Farmers can significantly reduce the risk of disease and maintain the long-term health of strawberry plants through crop rotation with other non-host plants[38,39]. Plastic tunnels are also used to limit airborne fungal pathogens, and it has been reported that nonfungicide-treated tunnels can lower the incidence of fungal pathogens compared to fungicide-treated areas. However, these methods can lead to additional complications, such as promoting powdery mildew and resulting in a harsh harvesting process[43]. To perform this method, runner cuttings were taken from mother plants that had been deliberately contaminated with Colletotrichum acutatum. These cuttings were then immersed in hot water for 7 min at a temperature of 35 °C, followed by an additional 2 to 3 min at a higher temperature of 50 °C. The outcomes of these experiments were highly fruitful in lowering the infection rate of C. acutatum in the cuttings, resulting in a significant reduction in the C. acutatum pathogen, with incidence rates reducing from above 80% in untreated control samples to a range of only 6% to 17% in the treated samples[44]. In conclusion, cultural practices are crucial for controlling fungal infections in strawberries, particularly in organic agriculture.

Role of synthetic pesticides

-

Synthetic pesticides are commonly applied by farmers to control strawberry diseases, mainly anthracnose rot caused by Colletotrichum acutatum and grey mold rot caused by Botrytis cinerea[45]. Early in the season, beginning in November-December, the percentage of C. acutatum inoculum was generally low. Consequently, these conditions are unfavorable for the growth of this pathogen, which means that infected plants do not exhibit any symptoms. At this stage, the first step in controlling the disease involves utilizing low-label rates of broad-spectrum protectant fungicides such as Captan[45]. Historically, several synthetic fungicides, such as carbendazim, prochloraz, mancozeb, and Tecto 60, have been applied to manage Colletotrichum spp., the fungus that causes anthracnose rot in fruits such as strawberries[46,47]. In the recent edition of the 2023 Southeast Regional Strawberry Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Guide for Planting Production, various fungicides have been identified as 'Excellent' for effectively managing fruit rot in strawberry crops. These included the merivon (7 + 11), Luna sensation (7 + 11), pristine (7 + 11), Quadris top (3 + 11), quilt xcel (3 + 11), abound (11), cabrio (11), flint extra (11), and miravis prime (12 + 7). However, commonly used fungicides such as captan and thiram were rated good and fair, respectively[48]. However, it is crucial to use all these fungicides cautiously and in combination with different active chemical ingredients to prevent the development of resistant strains of C. acutatum. In the previous two decades, the main pesticides used in strawberry production against B. cinerea belonged to the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) Groups one and two, as well as the captan[11,48]. However, due to the increase in fungicide resistance and new legal restrictions, growers have been restricted from diversifying their fungicide regimens[48]. The frequency and duration of fungicide treatment are important for B. cinerea control. A single application of fenhexamid (FRAC 17) at anthesis can be as efficient as multiple weekly applications[49]. Additionally, alternating and combining various fungicides with different modes of action are recommended. Resistance of B. cinerea to fungicides is a real challenge in horticulture, and fungicide resistance profiles can shift considerably even within a single season[11,50]. There is a need for innovative management practices because a number of isolates resistant to the most common multi-action site fungicides are activated. In view of this, new generation RNA-based fungicides have evolved that depend on the application of sRNAs or dsRNAs targeting B. cinerea virulence genes to control fungal infections in strawberries[51]. However, these RNA-based fungicides are unavailable for commercial use, which is why fungicide resistance management—such as mixing and rotating different fungicides or testing local isolates for resistance—is necessary[52]. Multisite or protective fungicides, such as copper, sulphur, captan, dithianon, or tolylfluanid, work in a nonspecific manner by targeting fundamental processes of fungal metabolism, particularly those affecting cellular redox processes. These compounds infrequently encounter resistance, and even when resistance does occur, it results in only low levels of resistance[53,54]. Unfortunately, several countries are no longer ready to use these compounds for reducing Botrytis risk in strawberry plants due to their limited impact. Moreover, single-site-specific fungicides target certain molecular targets and are highly effective against B. cinerea. However, B. cinerea, the pathogen that causes gray mold rot, is known for its resistance to these specific fungicides. This resistance is caused mainly by mutations in the target sites[54]. Interestingly, both B. cinerea and B. fragariae have a 'multidrug resistance' mechanism in which they overexpress plasma membrane-bound efflux pumps; these pumps efficiently repel various chemically unrelated fungicide molecules, protecting against their effects[52−55]. First, innovative management approaches, such as the use of RNA-based fungicides, crop rotation, and mixtures of various fungicides, are necessary to effectively control strawberry diseases while preventing the development of resistance.

Emphasizing holistic and environmentally friendly approaches

-

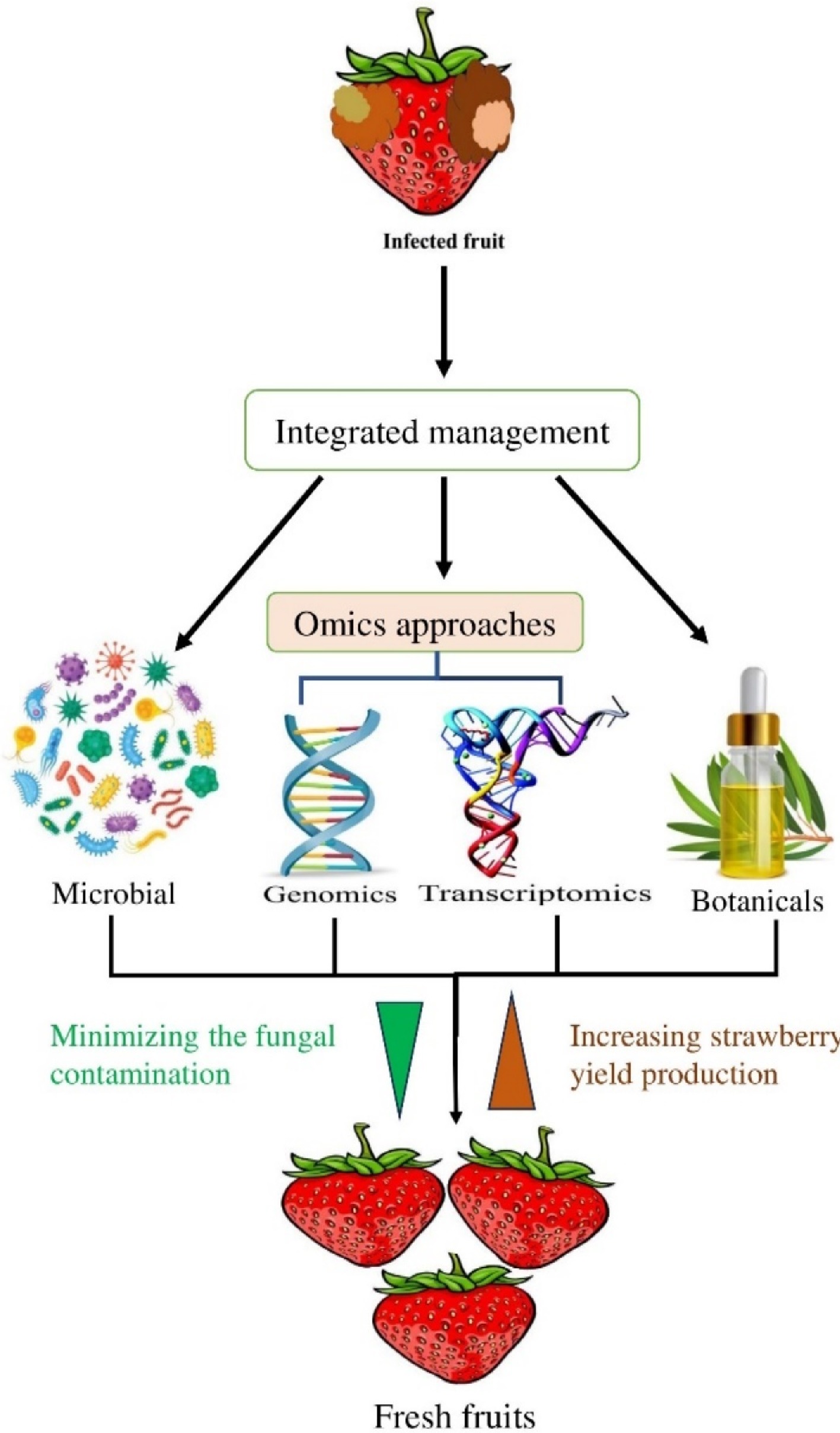

By adopting a holistic perspective, researchers can develop strategies that take into account the various ecological, social, and economic factors at play. This approach is supported by scientific evidence that highlights the importance of protecting and preserving ecosystems for long-term sustainability. This approach encourages the integration of environmental considerations into decision-making processes and promotes the use of environmentally friendly technologies and practices, as exhibited in Fig. 1.

Biological control

-

As a result, they produce antimicrobial compounds, strengthen cell walls, and express pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins. However, certain microbial agents can produce cell wall-degrading enzymes that are used against pathogenic fungi, reducing their infection process[40,56]. In view of the microbes used against strawberry fungal pathogens, some examples, such as Bacillus subtilis-based biocontrol products, have been limited in commercial strawberry production due to their decreased applicability in the field and supply chain[57]. However, there is emerging interest in using biocontrol methods as alternatives to synthetic pesticides for managing Botrytis cinerea, the most common strawberry fungal pathogen. Various microbial isolates, including Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Epicoccum purpurascens, Gliocladum roseum, Penicillium sp., and Trichoderma sp., have shown promising results in controlling B. cinerea. These microbial strains reportedly lower the incidence of gray mold on strawberry stamens by 79%–93% and on fruits by up to 48%–76%[58]. Surprisingly, several biocontrol agents were tested and found to be more effective than the fungicide captan. Other microbial isolates, such as the yeasts Aureobasidium pullulans and Candida intermedia, the filamentous ascomycete Ulocladium atrum, and the bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, have also shown efficacy against B. cinerea[59−61]. The most significant effects are observed when different organisms are applied in combination, as they utilize different mechanisms to control Botrytis cinerea[61]. Alternatively, extracts or volatiles derived from biocontrol microbes have been suggested as a means of control[60]. Nonsynthetic antifungal substances, such as phenol-rich olive oil mill wastewater, have also been reported to effectively control B. cinerea growth in vitro and on strawberries[62]. However, these approaches are not widely adopted on a commercial scale due to their higher costs than conventional B. cinerea control methods.

Botanical control: an alternative and sustainable solution

Essential oils

-

Botanical pesticides have become increasingly recognized as efficient and environmentally friendly solutions. One alternative soil fumigation method involves the use of glucosinolate-containing Brassica spp. plants, which release volatile isothiocyanates (ITCs) that are lethal to various soilborne plant pathogens[63]. However, this treatment works in a dose-dependent manner, as does the difference in ITC concentration among mustard varieties, resulting in incompatible fumigation outcomes. Growers have adopted this technique less often due to the low efficacy of this treatment[64]. In view of the potential use of bio fungicides in both field and storage conditions, the essential oils (EOs) of A. sativum and R. officinalis exhibited promising fungicidal activity against C. nymphaeae to protect strawberries with minimal negative impacts on the physicochemical, qualitative, and sensory attributes of fresh strawberry fruits[65]. To combat fungal rot in fruits, researchers have found that approximately 60% of plant essential oils and their constituents have high inhibitory effects on various pathogenic fungi, including Botrytis. Some of them are included in Table 2. Additionally, these essential oils have been shown to enhance the shelf life of fruits by minimizing fungal decay[66].

Table 2. Showing beneficial plant volatiles against fungal pathogens of strawberry fruit.

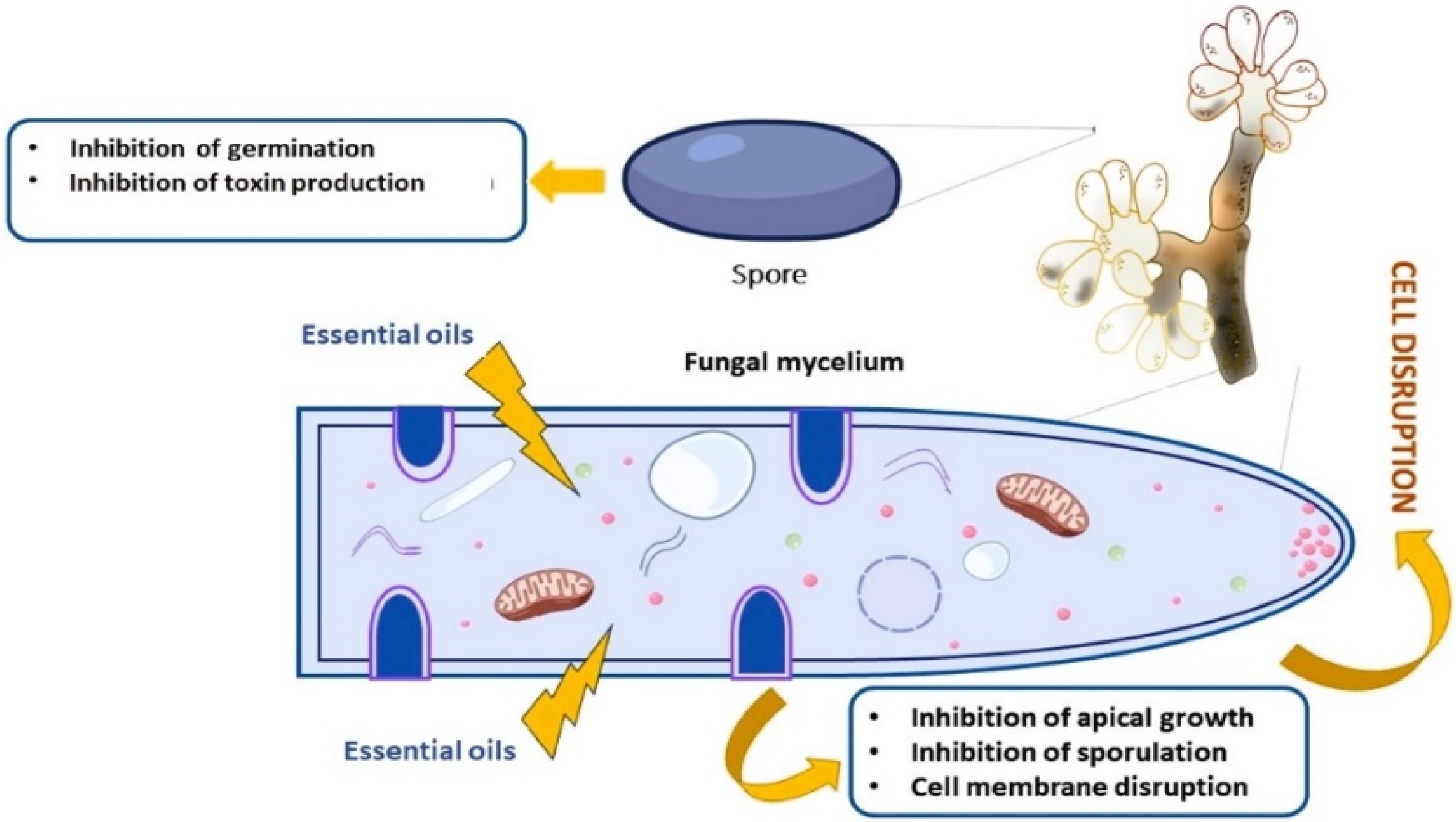

Disease Pathogens Essential oils Plant part use Effective dose Ref. Grey mold Botrytis cinerea Origanum onites L. Leaves 1.00 mL·L−1 [66] Ziziphora clinopodioides L. Leaves and flowers 2.00 mL·L−1 Thymus vulgaris Leaves and flowers 0.021% [67] Mentha longifolia Leaves 0.021% Mentha spicata Leaves 10% [68] Cymbopogon martini Leaves and flowers 10% Origanum heracleoticum Leaves and flowers 100 μL·L−1 [69] Thymus vulgraris Leaves and flowers 100 μL·L−1 Syzygium aromaticum Dried flower buds 92.56 μL·L−1 [70] Brassica nigra Seeds 15.42 μL·L−1 Solidago canadensis Inflorescence 0.1 mL·L−1 [71] Zataria multiflora Leaves 1,500 ppm [72] Leak mold Rhizopus stolonifera Mentha spicata Leaves 10% [68] Cymbopogon martini Leaves and flowers 10% Pelargonium graveolens Leaves 625 μL·L−1 [73] Cymbopogon citratus Leaves 500 μL·L−1 Foeniculum vulgare Seeds 800 μL·L−1 [74] Nigella sativa Seeds 800 μL·L−1 Pimpinella anisum Seeds 800 μL·L−1 Anthracnose Colletotrichum spp. Mentha longifolia Leaves and shoots − [75] Allium sativum Bulbs 1,700 μL·L−1 [65] Rosmarinus officinalis Leaves and flowers 700 μL·L−1 Cinnamon zeylanicum Inner bark 301.152 μL·L−1 [76] Satureja khuzestanica Leaves and flowers 550.803 μL·L−1 Aloysia citriodora Leaves − [77] Lippia alba Leaves − Ocimum americanum Leaves − According to laboratory tests, several essential oils exhibit potential efficacy against fungal pathogens and extend the shelf life of various fruits. Notably, essential oils from Origanum onites, Ziziphora clinopodioides, and Matricaria chamomilla were found to be effective against B. cinerea[66,67]. The mode of action of essential oils against pathogens can vary depending on the specific oil and chemical components, susceptibility of the pathogen, environmental conditions, and other factors. However, various effective mechanisms have been proposed, and several essential oils containing terpenoids and phenolics have antifungal properties and are able to disrupt fungal growth[67,68] including cell membrane integrity, respiration, and enzyme activity, ultimately leading to cell apoptosis or inhibition of spore germination (Fig. 2). Studies have reported that essential oils used as antifungal agents have detrimental impacts on cell morphology and ultrastructure (Fig. 2). EOs primarily target the cell membrane and its components; for instance, the EO of Solidago canadensis, applied at a concentration of 0.1 mL·L−1, alters the cellular structure and membrane permeability of B. cinerea[71]. EOs can enhance pathogen death under favorable conditions by altering the membrane potential, the transport of nutrients and ions, and the permeability of fungal cells. This result is supported by Ultee et al.[78] who explained that the lipophilic qualities of EOs support their ability to penetrate the plasma membrane, leading to the accumulation of polysaccharides under drought stress conditions and ultimately causing membrane disruption (Fig. 2).

Additionally, many EOs have been used to prolong the shelf life of fruits by controlling fungal decay. For example, Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Mentha piperita effectively increase the shelf life of strawberries for up to 18 d without affecting their sensory properties[79]. Origanum majorana, when employed at a concentration of 500 ppm, minimizes Botrytis decay up to 60% in strawberries after 8 d of storage. Moreover, the treated fruits possess their nutritional qualities, including high levels of vitamins, sugars, phenolics, and titrable acids[80].

Plant extracts

-

Numerous studies have been conducted worldwide to investigate the impact of plant crude extracts on the quality and shelf life of strawberry fruits, and the results are shown in Table 3. Several plant extracts are potential botanical alternatives to Botrytisides, with a focus on their fungicidal activity against B. cinerea, the causal agent of grey mold of strawberry[81]. This study revealed that the ethanolic extracts of Galenia africana and Elyptropappus rhinocerotis have high inhibitory potential against B. cinerea, particularly when combined with the fungicide kresoxim-methyl. Similarly, extracts of Stryphnodendron, Caesalpinia, Paullinia, and Erythroxylum also exhibited inhibitory effects on B. cinerea, while extracts of Erythroxylum and Caesalpinia had high soluble solid values in treated fruits[82]. Furthermore, a formulation of Pelargonium graveolens leaf extract with chitosan (at a conc. 25 mg of chitosan nanoparticles/ml) showed fungistatic effects on B. cinerea, extending the shelf life of strawberry fruits[83]. The combined treatment with turmeric and green tea extract (edible coating), along with chitosan, enhanced the shelf life of strawberry fruits and maintained their antioxidant properties[84].

Table 3. Effective plant extracts against fungal pathogens of strawberry fruit rot.

Disease Pathogens Plant extract Plant part use Effective dose Ref. Gray mold Botrytis cinerea Coriandrum sativum Seeds 0.0312 g·mL−1 [82] Cinnamon zeylanicum Inner bark 800 μL·L−1 [85] Azadirachta indica Leaves 15% w/v [86] Syzygium aromaticum Dried flower buds 600 μL·L−1 [87] Silene uniflora Leaves and flowers 1500 μg·mL−1 [88] Allium sativum Bulb 20% [89] Origanum majorana Leaves and flowers 20% Thymus vulgaris Leaves and flowers 20% Leak rot Rhizopus stolonifer Laminaria digitata Dry thallus 30 g·L−1 [90] Euphorbia tirucalli Latex and stem bark − [91] Citrus sinensis Peels − [92] Crocus sativum Petals 235.15 μL·L−1 [93] Eucalyptus Leaves 30% [67] Anthracnose Colletotrichum spp. Piper betle Leaves 100% [94] Azadirachta indica Leaves 10,000 μL·L−1 [95] Cinnamomun zeylanicum Inner bark − [96] Melissa officinalis Leaves 20% w/v [97] Origanum vulgare Leaves and flowers 20% w/v Datura stramonium Whole plant 25% w/v [98] Allium sativum Bulb 25% w/v Lawsonia inermis Leaves 25% w/v Despite their impacts, these compounds are limited by their low persistence in the environment and low bioavailability compared to chemical pesticides. Thus, there is a need for commercially viable formulations based on these compounds to enhance and sustain their efficacy.

-

Omics techniques, including transcriptomics, genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, have been used to investigate the efficacy of postharvest treatments on fruit quality and safety during storage[99]. Current progress in omics approaches, such as genomics and transcriptomics, provides new insights into molecular mechanisms and the identification of biomarkers for early disease detection in plant pathology[100]. By integrating multiple omics technologies, diseases can be effectively prevented and managed by deciphering the gene function, genome structure, and metabolic profiles of both the host plant and the pathogen during infection[101].

Genomic approaches

-

Since the groundbreaking sequencing of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome in 1996, the field of genomics has revolutionized DNA sequencing through methods, including Sanger dideoxy nucleotide sequencing and pyrosequencing, which have been successful in de novo and confirmatory sequencing of pathogens[102]. Pyrosequencing is commonly used for SNP analysis and sequencing short sections of DNA. Next-generation sequencing technologies, such as Illumina/Solexa, Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine, and Pacific Biosciences, have greatly advanced the genomic and genetic research methods currently used[103]. Botrytis cinerea is a notorious plant pathogen whose genetic diversity determines its phenotypic variation, including virulence, host range, and adaptation to various environmental conditions. Genomic studies offer a comprehensive exploration of the genomic architecture, enabling a robust analysis of evolutionary patterns and driving factors behind disease spread[104].

Recent genomic advancements in octoploid strawberry breeding have provided valuable insights into the genetic basis of resistance to Phytophthora crown rot, and genetic sources of resistance against this pathogen have been identified for enhancing strawberry varieties. Through the identification of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) associated with PhCR resistance, breeding efforts for PhCR-resistant octoploid strawberries have improved[105]. To gain detailed knowledge of B. cinerea-host interactions, Syngenta AG initiated a genome sequencing project for the B. cinerea T4 and B05.10 strains using Illumina HiSeq2000 technology. The resulting genome sizes were 37.9 Mbp (14,270 genes) and 38.8 Mbp (13,664 genes)[106]. The current report utilized a combination of Illumina and PacBio sequencing techniques to assemble the complete genome sequence of the B. cinerea B05.10 strain[107]. This assembly consists of 18 chromosomes, a genetic map of 4,153 cM, and approximately 75,000 single-nucleotide polymorphic markers. A draft genome of another isolate of Botrytis cinerea, whose genome size is approximately 42 Mbps and spread across 16 chromosomes, is also[108]. Genome sequencing has been useful for elucidating the genetic and environmental basis of Botrytis cinerea host specificity. Resequencing 13 different B. cinerea isolates revealed the species broad host range and potential to adapt to new hosts. In addition, whole-genome sequences of strawberry 240 Mbp, have also been studied[109]. With the availability of genome sequences, various studies, including comparative genomic analysis, which characterizes effector repertoires and likely plays a key role in host-pathogen interactions during postharvest and directly alters management strategies, have been performed.

Transcriptomic approaches

-

Transcriptomics and proteomics are important tools for understanding gene expression and protein interactions within organisms[99]. The RNA-Seq method has revolutionized transcriptome analysis by allowing researchers to study gene expression under various conditions and discover new genes and transcription patterns. This technique has proven to be indispensable in determining plant pathology, particularly in analyzing the transcriptomic profiles of plant pathogens during infection[110]. The dynamic interaction between hosts and pathogens necessitates a dual approach for studying these interactions, and dual RNA sequencing enables the simultaneous analysis of host and pathogen transcriptomes, providing valuable insights into pathogen-specific transcripts and host defense mechanisms[111]. This approach has been successfully used in understanding plant-pathogen interactions in numerous crops, medicinal plants, and forest trees, including grapevines, peaches, Eucalyptus sp., and Pinus sp.[111]. In addition, transcriptomic tools were used to evaluate the ability of several botanical formulations to prevent pathogen resistance. For example, the active components of tea-tree oil, terpinen-4-ol, and 1,8-cineole alone and in combination had inhibitory effects on B. cinerea. Transcriptional profiling of the pathogen revealed that terpinen-4-ol primarily affects DEGs[112]. In control vs tea tree oil comparison, 280 DEGs (105 upregulated and 175 downregulated) involved in the synthesis of secondary metabolites, amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipid metabolism, followed by defective mitochondria, oxidative stress, and reduced enzymatic effects were identified, while 1,8-cineole chiefly affected genes associated with genome, transcription, replication, and repair. Both treatments synergistically affect the cell wall, cell membrane, mitochondria, and genetic material of fungal pathogens, leading to cell death[112]. Furthermore, for the Melaleuca alternifolia and Botrytis cinerea interaction, transcriptomic analysis revealed that 17 DEGS were upregulated, while 701 DEGs were downregulated. Essential oils also inhibited glycolysis, degraded the TCA cycle, and enriched mitochondrial dysfunction by disrupting energy metabolism. This investigation provides a new understanding of the antifungal mechanism of EOs[113].

Transcriptomic studies can be used in several ways to mitigate SFR; for example, they can identify specific genes and metabolic pathways that are involved in the development and progression of SFR. This knowledge is useful for developing targeted strategies to interrupt these processes by suppressing key genes or manipulating specific metabolic pathways[114]. This knowledge provides insights into the genes that play crucial roles in plant defense responses against Botrytis infection. These studies were useful for identifying specific gene expression patterns or biomarkers that are associated with fruit susceptibility or resistance to Botrytis infection[113]. These biomarkers are used to develop rapid and reliable diagnostic tools for predicting fruit susceptibility or monitoring disease progression, enabling the timely application of control measures and providing valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction between pathogens and fruit commodities. This understanding can aid in the development of novel strategies to disrupt this interaction, such as through the manipulation of host response genes or through the design of targeted antifungal agents.

-

Ongoing research should focus on further integrating integrated approaches to explore SFR, which can cause tremendous economic losses. To overcome commercial, public, and environmental issues, this review provides insight into conventional, chemical, microbial, botanical, and omics-based strategies for enhancing the management of strawberry fruit rot diseases, with the aim of developing targeted and sustainable disease prevention approaches. It is important to study, research, and implement these innovative disease management techniques to reduce dependency on harmful chemicals and save the environment. By emphasizing holistic approaches and working on sustainable solutions, more resilient and compatible agroecosystems can be developed for forthcoming generations. Many botanicals have been found to potently combat fungal pathogens in strawberry plants, and further exploration of how to improve the shelf life of strawberry fruits has been performed. However, these botanicals were not tested for toxicity, and other regulatory measures require further investigation. Finally, omics studies such as genomics and transcriptomics have been conducted on strawberry fruit rot pathogens, but these studies have provided insight into only fundamental aspects and have been confined to only the laboratory level. In future research based on laboratory data, resistant fruit cultivars should be developed and evaluated for their resistance to pathogens in warehouse, storage, and field conditions so that they can be easily delivered to consumers. Such a strategy will be cost-effective and enhance fruit quality, thereby increasing acceptance among consumers.

In conclusion, this review describes the progress of SFR management over the past decade. With the implementation of novel approaches, including biological and botanical management, it is possible to contribute to the advancement of sustainable agriculture and mitigate the negative impacts of disease management strategies. This approach will not only improve the environment but also ensure the long-term viability of agricultural systems. Additionally, the integration of omics approaches in the study of fungal pathogens in strawberry holds significant promise for improving disease control strategies and reducing economic losses for growers and producers. Additionally, the modes of action of botanicals against pathogens are discussed. Several antagonistic bacteria, e.g., Bacillus sp., have been registered for commercial application in the management of fruit rot pathogens. The synergistic use of biological and botanical methods for the management of infection in fruits and related products can be a sustainable strategy. Moreover, the cost-benefit ratio, low-cost formulation, and large-scale trials of efficient microbial antagonists and botanicals reported against B. cinerea need to be further explored and optimized.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: writing – original draft, Conceptualization: Dwivedi M; writing – review & editing: Dwivedi M, Rai RK, Singh P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data generated and analyzed during this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Dwivedi M, Rai RK, Singh P. 2025. Evaluating innovative strategies for managing strawberry fruit rot diseases: insight from current research. Studies in Fungi 10: e012 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0012

Evaluating innovative strategies for managing strawberry fruit rot diseases: insight from current research

- Received: 19 January 2025

- Revised: 12 April 2025

- Accepted: 27 May 2025

- Published online: 02 July 2025

Abstract: Strawberry plants are important horticultural fruit crops cultivated worldwide. This crop forms the foundation of a multi-billion dollar food industry and serves as a major employer of the global population. Fruit rot disease, caused by fungal pathogens, results in significant pre and postharvest losses in strawberries, presenting a considerable challenge to the industry's overall health. Moreover, infected fruits are unappealing to both commercial buyers and domestic consumers, leading to substantial losses for growers. In view of the effective management of these pathogens, extensive research has been conducted due to their wide host range and the enormous economic losses they cause. Exploring the biology of pathogens is advantageous for obtaining a better understanding of the fundamental basis for mitigation strategies. Pathogens are managed in fruit commodities by using physical, chemical, and biological approaches. To minimize the harmful effects of chemical pesticides on the environment, ongoing efforts are underway to explore alternative methods for controlling plant diseases using eco-friendly biocontrol agents or natural products with pathogen-controlling properties. In recent years, tremendous progress has been made in understanding the role of omics approaches, including genomics and transcriptomics, in controlling strawberry fruit rot. This study delves into the fundamentals of this problem, the basic biology of the pathogen, traditional and contemporary approaches to disease control, and potential future perspectives.

-

Key words:

- Strawberry fruit rot /

- Integrated management /

- Biological control /

- Botanical control /

- Omics approaches