-

Agricultural crop wastes generated during the production and processing of food materials could act as a source of environmental pollution[1]. The quantity of these crop residues has increased over the years as a result of expansion of agricultural production and intensifying farming systems[2]. Proper waste management is being carried out to reduce the risks of pollution.

The Philippines is a tropical nation that produces a wide range of valuable agricultural products, including cacao and coffee. In 2020, cacao and coffee production in the country reached 9,341 MT[3], and 30,320.47 MT GCB[4], respectively. With this, a large quantity of waste is generated throughout the postharvest processes, creating difficulties with management and proper disposal. Cacao pod husk (CPH) makes up around 67%–76% weight of the fresh cacao fruit[5], whereas coffee husk (CH) makes up roughly 45% of fresh coffee cherry weight[6]. If left unattended, these agricultural wastes can attract pests and introduce diseases in the environment[7−9]. Thus, a sustainable approach to utilize these agricultural wastes is being sought, especially to explore their potential biocontrol activities.

Fungicides are agrochemicals used to inhibit or control phytopathogenic fungi in agricultural commodities, thereby preventing disease damage and improving product quality in climate changing scenarios[10]. Nowadays, the occurrence of virulent phytopathogenic fungi is becoming evident, causing a serious threat to many plants, and enormous losses in agricultural productivity. Fusarium oxysporum is the causative agent of a notorious Fusarium wilt disease, resulting in devastating yield reductions of essential cash crops, such as mungbean[11], banana[12], tomato[13], and cotton[14]. Meanwhile, Neopestalotiopsis hispanica has been reported to cause a disease in economically important plants, showing leaf necrosis and cutting dieback in eucalyptus[15], twig canker, dieback, and defoliation in bottlebrush and myrtle[16], and leaf and twig blight in blueberry[17]. Synthetic chemical fungicides are usually employed to suppress such harmful fungal phytopathogens and to mitigate crop diseases[18]. But the extensive and prolonged use of these synthetic fungicides has led to environmental issues like pollution, residual toxicity, and the emergence of fungicide-resistant phytopathogens[19,20]. Consequently, this plight needs to be addressed by the development of new, economical, and ecologically suitable fungicide substitutes[19−22], which include the use of crop wastes as potential fungicides. Some of the agricultural crop wastes that have potential fungicide properties include maize waste against Rhizoctonia solani[23], garlic peel waste against Colletotrichum acutatum[24], and tomato residues against Pleurotus ostreatus[25].

Few studies in the Philippines have documented the ability of Neopestalotiopsis and Fusarium species to infect the Philippine endemic Areca ipot[26], and Cavendish bananas[27], respectively. However, phytopathogenic fungi remain a persistent and growing threat to Philippine agriculture, which can reduce crop yield, reduce income of farmers, and endanger food security[28]. They can threaten global food security and destroy up to 30% of crop production through disease and spoilage processes[29]. Nevertheless, current management of practices for fungal phytopathogens can be ineffective, expensive, and sometimes environmentally harmful. In this work, the potential of CPH and CH extracts as botanical control agents against Neopestalotiopsis and Fusarium phytopathogenic species were examined. The goal is to contribute to the ongoing search for an environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic fungicides to possibly mitigate fungal infections in valuable crops.

-

A total of 2 kg each of fresh CPH, and CH were collected, thoroughly cleaned, and then subjected to crude extraction following the standard procedures[30−32], with minor modifications. The CPH and CH samples were washed with distilled water, drained, and air-dried at room temperature for 7 d. These were further dehydrated for 12 h at 65 °C in an oven. The plant materials were ground into a powder and put through the ethanolic extraction procedure. In an airtight container, each 400 g of powdered CPH and CH were macerated in 2 L of 80% ethanol, at room temperature for 72 h. The ethanolic solution was placed in the shaking incubator for 24 h to obtain a homogenized mixture. All mixtures were filtered using a cheesecloth before filtration with Whatman filter paper. The filtered extracts were submitted to the Institute of Chemistry - Analytical Services Laboratory, University of the Philippines in Los Baños (UPLB) (Laguna, Philippines) for the extraction procedure using a vacuum pump-equipped rotary evaporator and qualitative phytochemical screening of plant extracts. The thick and viscous extracts that were produced were kept at 4 °C until further testing.

Treatment preparation

-

The preparation of treatments was carried out based on the study of Durgeshlal et al.[21] with minor modification. The two plant extracts were tested on test organisms at three different concentrations (i.e., 100%, 50%, and 25%), with the concentrated extract acting as the highest concentration. The subsequent concentrations were achieved by serial dilution using sterile distilled water as a diluent. In addition, Fungufree Plus 50 WP was used as the positive control while the negative control was untreated.

Iodoform test

-

The Iodoform test was performed according to Durgeshlal et al.[21] to test the presence of ethanol in the extracts. A small amount of 0.5 M iodine solution (about 20 drops) was added to 10 drops of each of the CPH and CH extracts. About 10 drops of 1 M NaOH were then added to the mixture. Finally, to see if there was any reaction, the tubes containing the solution were allowed to sit for 5−10 min. A yellow precipitate in the extracts indicates the presence of ethanol.

Phytochemical screening

-

A portion of the ethanolic extracts from CPH and CH were sent to the Analytical Services Laboratory, Institute of Chemistry, UPLB for qualitative phytochemical screening of alkaloids, anthraquinones, coumarins, flavonoids, phenolics, tannins, saponins, and terpenoids.

Preparation of fungal isolates

-

The isolate Neopestaliotopsis hispanica CvSU strain was obtained from the Microbial Culture Collection Laboratory, CvSU-Interdisciplinary Research Building, whereas the Fusarium oxysporum ATCC 3429 was provided by CvSU-Department of Biological Sciences. Both isolates were cultured in potato dextrose agar (PDA) slants to ensure their viability.

Antifungal activity assay

-

The antifungal activity of plant extracts against fungal phytopathogens at varying doses was evaluated using the poisoned food technique assay, following the procedure of Abhishiktha et al.[33] and Durgeshlal et al.[21], with slight modifications.

One milliliter of each plant extract concentration was mixed in 20 mL of PDA plates. The agar plates were swirled in a circular motion to distribute the extract in the medium and allowed to solidify. The negative control (PDA only), and positive control (PDA with 1 mL Fungufree 50 WP Plus) were also prepared. A 7-day-old fungal culture was spot-inoculated onto poisoned and control plates. The mycelium of the test isolate was placed in the middle of the petri plate and incubated for 7 d at 27 °C. The setup was carried out in triplicate. The diameter of colonies was measured using a digital vernier caliper after incubation, and the percentage of mycelial growth inhibition was computed and recorded. The percent inhibition of the fungi in different treatments and concentrations was determined using the formula M = (DC-DT)/DC × 100, where M is the mycelial percent inhibition, DC is the diameter of colony growth in the control plate, and DT is the diameter of the colony growth in the treated plate[21]. The experiment was repeated three times to ensure the validity of the findings.

Statistical analysis

-

The results of the percentage of mycelial growth inhibition were analyzed using the SPSS software to determine if there are significant differences among the percentage mycelial inhibition of the plant extracts and controls. A non-parametric Friedman Test with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was utilized[34].

-

The CPH and CH extracts were shown to contain important bioactive components, such as anthraquinones, alkaloids, flavonoids, coumarins, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, according to phytochemical screening (Table 1). The study only determined the presence of phytochemicals but not their concentrations.

Table 1. Selected bioactive compounds present in cacao pod husk and coffee husk ethanolic extracts.

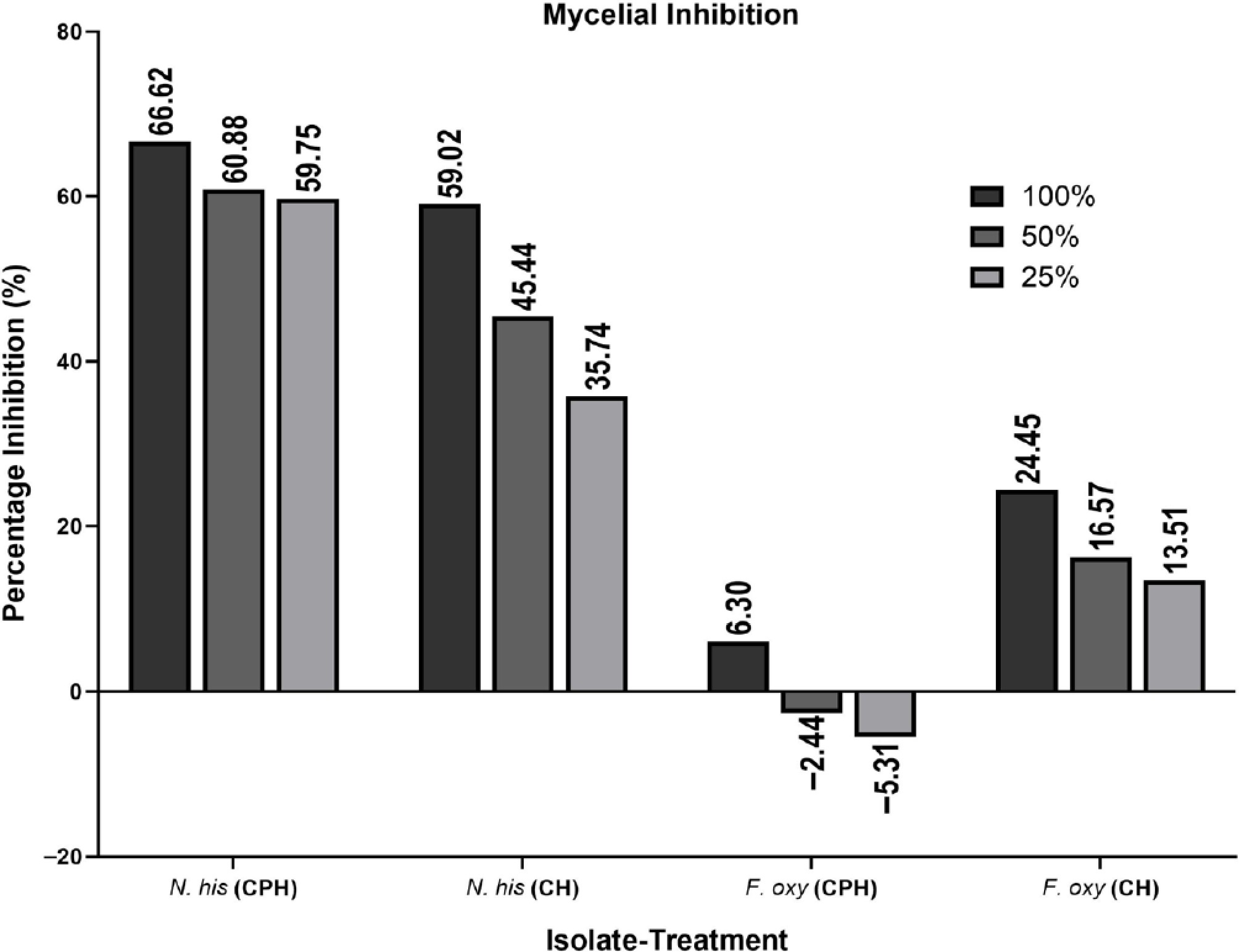

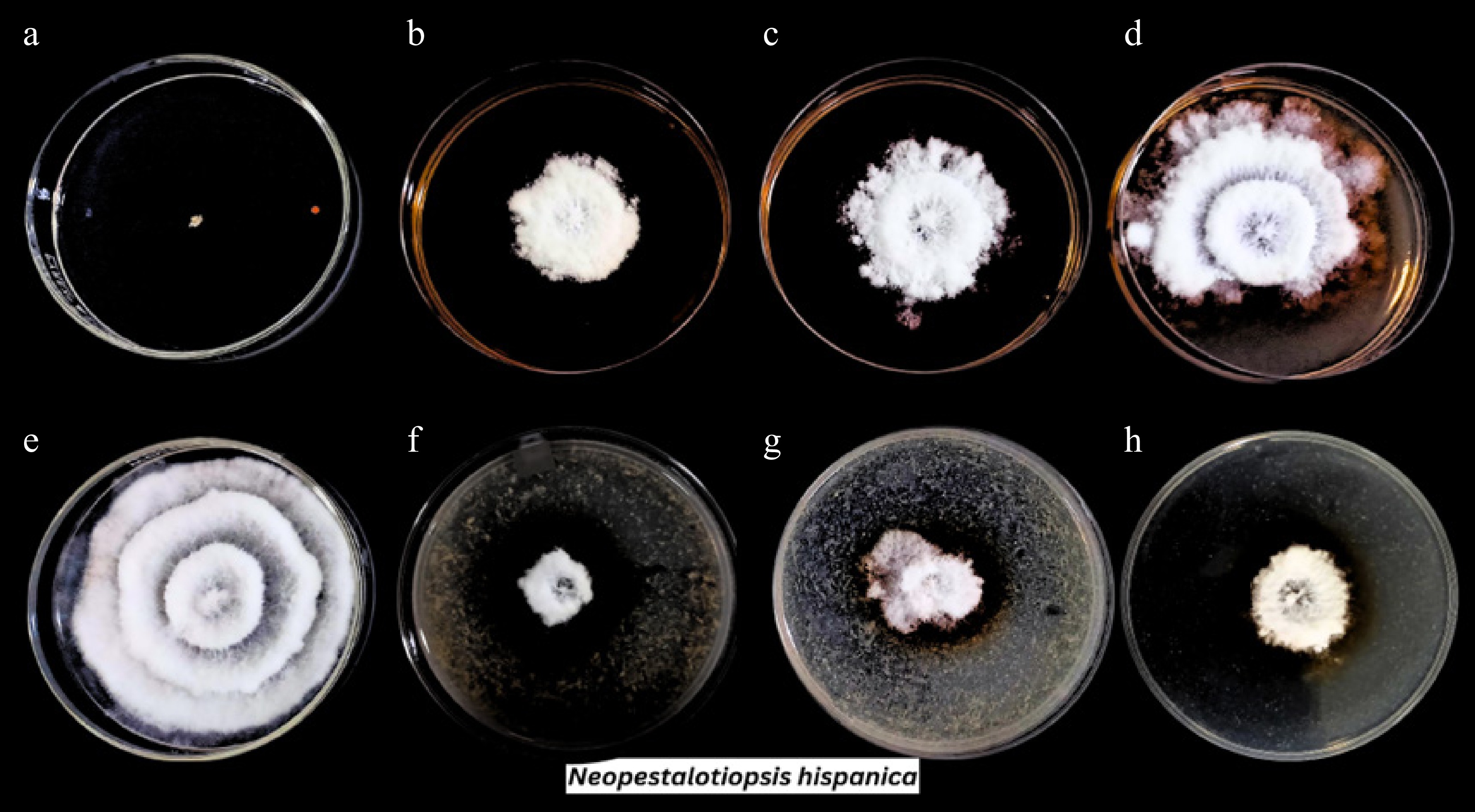

Bioactive compounds Cacao pod husk extract Coffee husk extract Anthraquinones + + Alkaloids − + Flavonoids + + Coumarins + − Tannins + + Saponins + + Terpenoids + + Legend: +, presence of the phytochemical compound; −, absence of the phytochemical compound. Among the two fungal isolates, Neopestaliotopsis hispanica had the greatest susceptibility rate to both plant extracts. Both extracts greatly affected the growth of this phytopathogenic fungus, with the 100% concentration being the most effective, followed by the 50% and 25% concentrations. When exposed to CPH extract, mycelial growth was drastically reduced, going from 82.90 to 27.67, 32.43, and 33.37 mm at 100%, 50%, and 25% concentrations, respectively. In addition, the growth of fungi was inhibited to 33.97, 45.23, and 53.27 mm at similar concentrations by the CH extract against N. hispanica (Table 2). Overall, its mycelial growth was decreased by a maximum of 66.62% in CPH-treated plates, whereas it was reduced by 59.02% in CH-treated plates (Fig. 1). The reduction of the mycelial growth of N. hispanica after being exposed to various plant extract doses is shown in Fig. 2. Although both extracts exhibited inhibitory effects against the specified fungus, the growth of the fungi was significantly inhibited by CPH (Fig. 2f–h) in comparison to the CH extract (Fig. 2b–d).

Table 2. Average mycelial growth of two fungal phytopathogens subjected to cacao pod husk and coffee husk extracts after 7 d incubation.

Treatment Conc. Diameter of mycelial growth (mm) Neopestalotiopsis hispanica Fusarium oxysporum *FF 1.6 g/L NG 38.6 ± 0.66 **NTA − 82.90 ± 0.80 54.57 ± 2.93 CPH extract 100% 27.67 ± 4.28 51.13 ± 0.80 50% 32.43 ± 1.10 55.90 ± 1.55 25% 33.37 ± 1.27 57.47 ± 0.45 CH extract 100% 33.97 ± 4.84 41.23 ± 1.36 50% 45.23 ± 4.13 45.53 ± 4.75 25% 53.27 ± 19.05 47.20 ± 0.85 Legend: *FF, Fungufree 50 WP Plus: positive control; **NTA, no treatment added: negative control; CH, coffee husk; CPH, cacao pod husk; NG, no growth. Values are expressed in means ± SD, in triplicate.

Figure 1.

Percentage of mycelial inhibition of the fungal phytopathogens upon exposure to cacao pod husk and coffee husk extracts (i.e., 100%, 50%, and 25%) for 7 d at 27 °C. N. his, Neopestalotiopsis hispanica; F. oxy, Fusarium oxysporum.

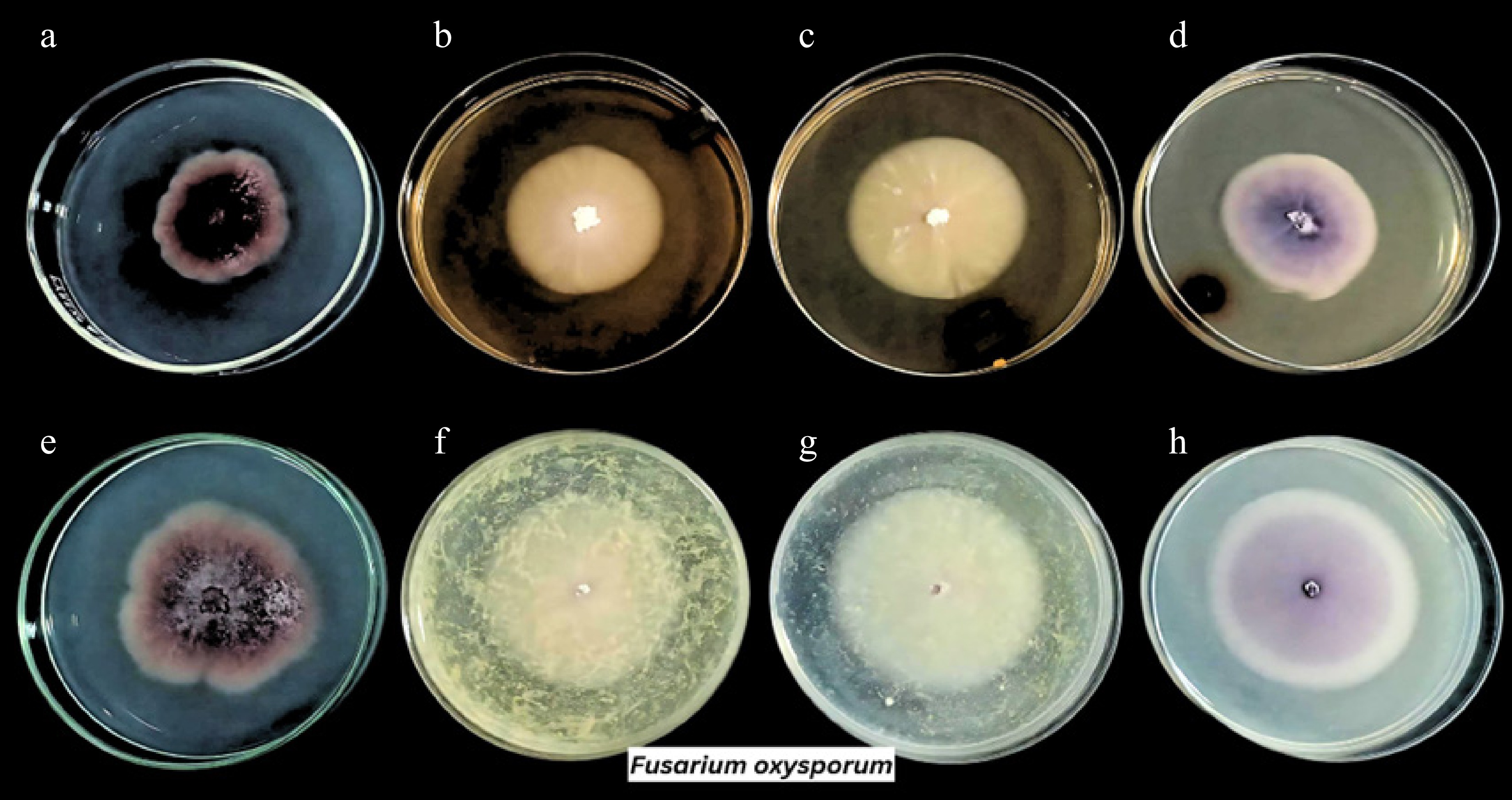

Figure 2.

Growth of Neopestalotiopsis hispanica in various treatments: (a) positive control, (e) negative control, (b)−(d) coffee husk ethanolic extract concentrations at 100%, 50%, and 25%, and (f)−(h) cacao pod husk ethanolic extract concentrations at 100%, 50%, and 25%, respectively.

On the other hand, minimal to unnoticeable inhibitions were noted against Fusarium oxysporum. The growth rate decreased somewhat at the highest concentration of CPH extract, from 54.57 to 51.13 mm. However, the CH extract was able to decrease the growth from 54.57 to 41.23, 45.53, and 47.20 mm at 100%, 50%, and 25% concentrations, respectively (Table 2). It is interesting to note that the colony morphology was variedly influenced by both plant extracts. It typically exhibits a pinkish or magenta surface color with a floccose texture (Fig. 3e). But when exposed to plant extracts, it changed (Fig. 3b, c, f, g), showing that the pigment faded in poisoned plates (Fig. 3). As can be seen in Fig. 3a, the commercially available fungicide used in this study, Fungufree 50 WP Plus (positive control), was not able to completely inhibit F. oxysporum even though it was effective for N. hispanica. Only around 30% of its development was suppressed on the fungicide solution-treated plates. A higher dose of the solution and a combination of fungicide maybe required to completely inhibit this pathogen[35−38]. Overall, the data demonstrated that both extracts were most effective at their maximum concentration relative to the lower concentrations. The efficacy of the extract against fungal isolates is dose dependent. The fungal growth inhibition increased as the concentration increases.

-

Fungal diseases are prevalent worldwide and have become resistant to chemical fungicides over time. This presents a serious risk to crop productivity, human health, and the environment[21]. The majority of farmers have traditionally applied these fungicides to plant crops, but the misuse and overuse of these products have significantly accelerated the growth of fungal resistance[18,39]. Due to this concern, scientists are looking for a more beneficial, but less expensive substitute, that might lessen the harm that these fungicides produce.

Botanical fungicides—which are mainly derived from plant materials—are one of the valuable alternatives that can be used for long-term management in protecting plant crops against pathogenic fungi because they are non-toxic, inexpensive, environmentally friendly, and have potential antifungal qualities[20,40]. Plant extracts have been reported for their potential as a biocontrol agent against fungal phytopathogens[41]. Many plant extracts have been shown to contain various bioactive compounds that have inhibitory qualities, which could be used to reduce the likelihood that plant would become resistant to the synthetic fungicides[42]. The effectiveness of other plant parts, such as the roots, stems, leaves, and fruits, has also been investigated.

CPH and CH are the outer covering of the cacao and coffee fruit. After harvest, the husks became agricultural waste that are often underutilized and could be a major challenge in crop production and the environment if not managed properly. Although some studies suggest these wastes have great potential against medically important pathogens, there have been limited studies about their potential use in controlling the growth of plant pathogenic fungi particularly on Neopestalotiopsis hispanica and Fusarium oxysporum. The presence of bioactive compounds on both CPH and CH extracts suggests that these can be exploited for controlling plant fungal diseases. For instance, anthraquinones were found to be effective in inhibiting the growth of phytopathogens up to 44% while demonstrating potential against resistant phytopathogens[43]. Subsequently, alkaloids derived from plants have found to be effective in inhibiting spore germination in several species of fungi[44]. Flavonoids are proven to disrupt fungal mechanisms[45] and coumarin contributes to antifungal activity by inhibiting mycelial growth and conidia formation[46]. Tannins (phenolics) are also known to disrupt cellular processes, manifested in spore germination of phytopathogens[47]. Lastly, saponins and terpenoids inhibited numerous phytopathogens' conidial germination and mycelial growth[48,49]. Essentially, the presence of bioactive compounds on both CPHs and CHs extract signifies its potential usage and further development as a botanical control agent against phytopathogenic fungi.

Besides, CPH and CH extracts used in this study demonstrated a relatively high mycelial inhibition (up to 66.62%) on the growth of N. hispanica while minimal inhibition (up to 24.45%) and colony morphology alterations were observed in F. oxysporum. Meanwhile, the changes in fungal colony morphology indicate a possible disruption on the growth pattern due to the extracts. Despite the observable changes in the growth pattern of the fungus, other factors such as fungal stress response and host defenses must be considered to understand its pathogenicity[50]. Nonetheless, these suggest that both extracts have a potential role as botanical control agents as these were able to affect and reduce the growth of the phytopathogenic fungi.

Moreover, previous studies supported that CPH and CH extracts possess high amounts of bioactive compounds that account for their antimicrobial properties[8,30,51−56] through various mechanisms including but not limited to inhibition of hyphae and biofilm formation, toxicity, cell apoptosis induction, and cell membrane integrity disruption[53,55]. In addition, CPH was reported to have an antimicrobial activity against F. oxysporum[30], Botrytis cinerea, Rhizopus stolonifer[52], Candida albicans[7], Aspergillus niger[57], Salmonella choleraesuis, and Staphylococcus epidermidis[51]. Meanwhile, CH extract was reported to have antimicrobial effects against Bacillus spp., Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas fluorescens[58], Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacillus acidophilus[55], Penicillium, A. niger, and A. flavus[59]. These extracts have been tested on various microbial pathogens but, to the best of the researchers' knowledge, no reports have been documented yet on the antifungal effects against N. hispanica.

-

This study demonstrates the potential biocontrol activity of the extracts derived from agricultural wastes, particularly the CPH and CH, against Neopestalotiopsis hispanica and Fusarium oxysporum. Some bioactive compounds were detected in both extracts, including anthraquinones, alkaloids, flavonoids, coumarins, tannins, saponins, and terpenoids. There was a noticeable increase in the inhibition rate on N. hispanica and a minimal inhibition on F. oxysporum along with changes on its colony morphology after being exposed to the treatments. Therefore, these agricultural wastes may be further explored for their potential use as biocontrol agents against fungal phytopathogens.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception, design, and manuscript preparation: Oliva EL, Embestro ARB, Anquilan FIZ, Cortes AD; material preparation, data collection, and analysis: Oliva EL, Embestro ARB, Anquilan FIZ; manuscript reviewing and editing: Cortes AD. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

We are grateful to the Department of Science and Technology, Science Education Institute (DOST-SEI) for providing Ms. Ernestine Oliva with financial support through the Junior Level Science Scholarship Program, and to the CvSU-Research Center for allowing us to perform the experiments at the Bacteriology Laboratory. We also extend our gratitude to the small-scale farmers in General Emilio Aguinaldo and Alfonso, Cavite, as well as the Café Amadeo Development Cooperative, for their assistance during the collection of crop wastes.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Oliva EL, Embestro ARB, Anquilan FIZ, Cortes AD. 2025. In vitro antifungal screening of cacao pod husk and coffee husk extracts against phytopathogenic Neopestalotiopsis hispanica and Fusarium oxysporum. Studies in Fungi 10: e024 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0025

In vitro antifungal screening of cacao pod husk and coffee husk extracts against phytopathogenic Neopestalotiopsis hispanica and Fusarium oxysporum

- Received: 03 July 2025

- Revised: 25 August 2025

- Accepted: 09 September 2025

- Published online: 05 November 2025

Abstract: Agricultural wastes raise concerns about their harmful environmental impacts, particularly when they accumulate and are not effectively managed. In this study, the potential of using coffee husk (CH), and cacao pod husk (CPH), two typical agricultural waste products were investigated, as safe alternatives to conventional fungicides against Neopestalotiopsis hispanica and Fusarium oxysporum. The effectiveness of these agricultural wastes' ethanolic extracts in inhibiting fungal growth was examined in vitro. Phytochemical compound screening revealed the presence of anthraquinones, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, and terpenoids in both extracts. The CPH and CH extracts showed a high rate of fungal growth inhibition against N. hispanica, which reduced mycelial growth by up to 66.62% and 59.02%, respectively. However, F. oxysporum only showed a reduction in mycelial growth up to 24.45% when exposed to CH extract, whereas CPH only caused a reduction of 6.30%. Despite the low inhibition rate, the colony morphology of F. oxysporum changed noticeably, especially as extract concentrations increased. These findings contribute to our knowledge of the potential antifungal properties of agricultural waste extracts, which may be used to control fungal diseases in a variety of crops.

-

Key words:

- Agricultural wastes /

- Antifungal activity /

- Fusarium /

- Neopestalotiopsis /

- Phytopathogenic fungi