-

Wheat, a staple global food crop, holds significant economic and nutritional importance, and plays a vital role in worldwide food production and supply[1,2]. The Huaibei Plain (HP), a primary wheat-growing region in China, lies at the southernmost part of the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain. With ample light and favorable temperature, the HP is suitable for wheat cultivation, and has an annual wheat-planting area of around 2.2 × 105 hectares. Securing high and stable wheat yields in this region is of great significance for ensuring national food security. However, the HP's dominant lime concretion black soil hardens and cracks under severe water deficiency, while excessive moisture from over-irrigation or heavy rainfall impairs its aeration. Regardless, this soil's inherent properties drive rapid soil moisture evaporation. These issues threaten high and stable wheat yields in the region[3]. Meanwhile, uneven precipitation in the growing season often leads to periodic droughts at wheat's critical growth stages, thereby limiting its yield potential[4]. Particularly during the jointing to booting stage, wheat frequently experiences insufficient soil moisture or even drought stress. In addition, nitrogen (N) is the most important nutrient element affecting wheat growth and yield formation[5]. Currently, in the HP, the prevalent practices in wheat production of farmers involves conventional flood irrigation and over-application of nitrogen, leading to wastage of both water and nitrogen resource, and even hindering high wheat yields[6]. Therefore, exploring appropriate water-nitrogen management techniques is essential for achieving synergistic improvement of water and nitrogen use efficiencies, and the coordinated enhancement of wheat yield in the HP.

As one of the crops with high water requirements, wheat needs over 400 mm of total water consumption for high yields[7]. Proper irrigation can promote wheat root growth, significantly enhance the uptake and utilization of soil water, increase dry matter accumulation in the population, and ultimately lead to higher grain yield[8,9]. Studies have shown a close relationship between wheat yield and post-anthesis dry matter accumulation from leaf assimilates. Maintaining optimal soil moisture during critical growth stages delays post-anthesis leaf senescence, significantly enhances photosynthetic capacity, promotes the accumulation and translocation of photosynthetic products to grains, and thereby improves wheat grain weight and yield[7]. However, soil water deficit can disrupt reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism in plants, leading to excessive malondialdehyde (MDA) accumulation, impaired cell structure and function, and rapid degradation of leaf chlorophyll content[10]. These changes reduce photosynthetic capacity and decrease dry matter accumulation[11]. To mitigate the adverse effects of external stress, plants rapidly synthesize antioxidant enzymes when stress occurs, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT), reducing MDA accumulation[12]. As the primary organs for water and nutrient acquisition, roots play a vital role in wheat productivity. A well-developed root system ensures a sustained supply of water and nutrients during the post-anthesis period, facilitating assimilate partitioning to grains—a pivotal mechanism underpinning high grain yield. Proper irrigation regimes can promote wheat root growth and deep penetration, thereby enhancing nutrient uptake and efficient utilization[13]. As a critical period for wheat root development, irrigation during the jointing and booting stages can significantly promote root growth, enhance SOD and POD activity in post-anthesis flag leaf, reduce MDA content, delay leaf senescence, and ultimately improve wheat yield[14]. Consequently, adopting an appropriate irrigation regime is crucial for promoting wheat root growth, enhancing leaf productivity, and increasing dry matter accumulation, thereby improving yield.

Nitrogen plays a vital role in crop growth and development. In the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain region, wheat is typically supplied with nitrogen application ranging from 180 to 240 kg·ha−1 under conventional flood irrigation, with split between pre-sowing basal fertilization and jointing-stage topdressing[15]. Research has confirmed that nitrogen application significantly affects wheat growth and development, and optimized nitrogen application can increase effective tillers, kernels per spike, and grain weight, thereby improving crop yield[16−18]. Excessive nitrogen application, however, may reduce crop yield; additionally, it increases residual nitrate nitrogen in the soil profile, leading to nitrogen leaching, groundwater pollution, and potential harm to the local ecological environment[19]. Proper nitrogen application primarily enhances crop photosynthetic capacity, delays plant senescence, and promotes the accumulation and translocation of assimilates, thus improving yields[20]. Conversely, either insufficient or excessive nitrogen application can inhibit root growth, increase lodging risk, delay maturity, reduce photosynthate accumulation, and lower yields[21]. Micro-sprinkler irrigation, a widely adopted technique in wheat production, enables frequent, low-volume water and fertilizer supply tailored to crop water and nutrient demands. Research has shown that, compared to conventional flood irrigation practices, the integration of water and N-fertilizer under micro-sprinkler irrigation, significantly increases wheat yields by increasing the leaf area index (LAI), maintaining high flag leaf chlorophyll content, and improving photosynthetic performance[22]. However, the effects of nitrogen application under micro-sprinkler irrigation on dry matter production and yield formation of winter wheat in the lime concretion black soil region of the HP region remain unreported.

Research indicates that the interaction between irrigation and nitrogen application, particularly the amount and timing of topdressing, significantly influences wheat yields[22,23]. An appropriate increase in topdressing nitrogen application can promote the ability of wheat roots to utilize deep soil water, which in turn effectively improves wheat drought resistance, promotes wheat growth and dry matter accumulation, and mitigates the adverse impacts of water deficit on wheat yields[24]. Micro-sprinkler irrigation technology ensures adequate soil moisture and nitrogen availability during critical growth stages, reduces nutrient leaching, promotes root development, and enhances wheat's absorption and utilization of soil water and nutrients[25]. Moreover, timely and adequate irrigation and topdressing nitrogen application can increase flag leaf chlorophyll content and LAI after anthesis, promoting dry matter accumulation, and significantly boosting wheat yields[7,22]. To summarize, the following research hypothesis is proposed: in the HP region, micro-sprinkler irrigation with optimized nitrogen application ensures a suitable water supply during key wheat growth stages, enhances the stress tolerance of post-anthesis leaf, delays the senescence both leaf and root, and thereby promotes dry matter accumulation of wheat, ultimately increasing grain yield. To verify this hypothesis, a field experiment was conducted during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 wheat growing seasons. The experimental design comprised two irrigation methods (conventional flood irrigation and micro-sprinkler irrigation) combined with three topdressing nitrogen levels (45, 90, and 135 kg·ha−1) under a basal nitrogen application of 112.5 kg·ha−1 for each irrigation method. This study examined the effects of different nitrogen application levels under the two irrigation methods on: (1) the spatiotemporal dynamics of soil moisture during the growing season; (2) the physiological traits associated with flag leaf senescence and root distribution; and (3) dry matter accumulation and grain yield of winter wheat. The findings of this study are expected to provide theoretical and technical support for achieving stress-resilient, high-yield wheat production in the HP region.

-

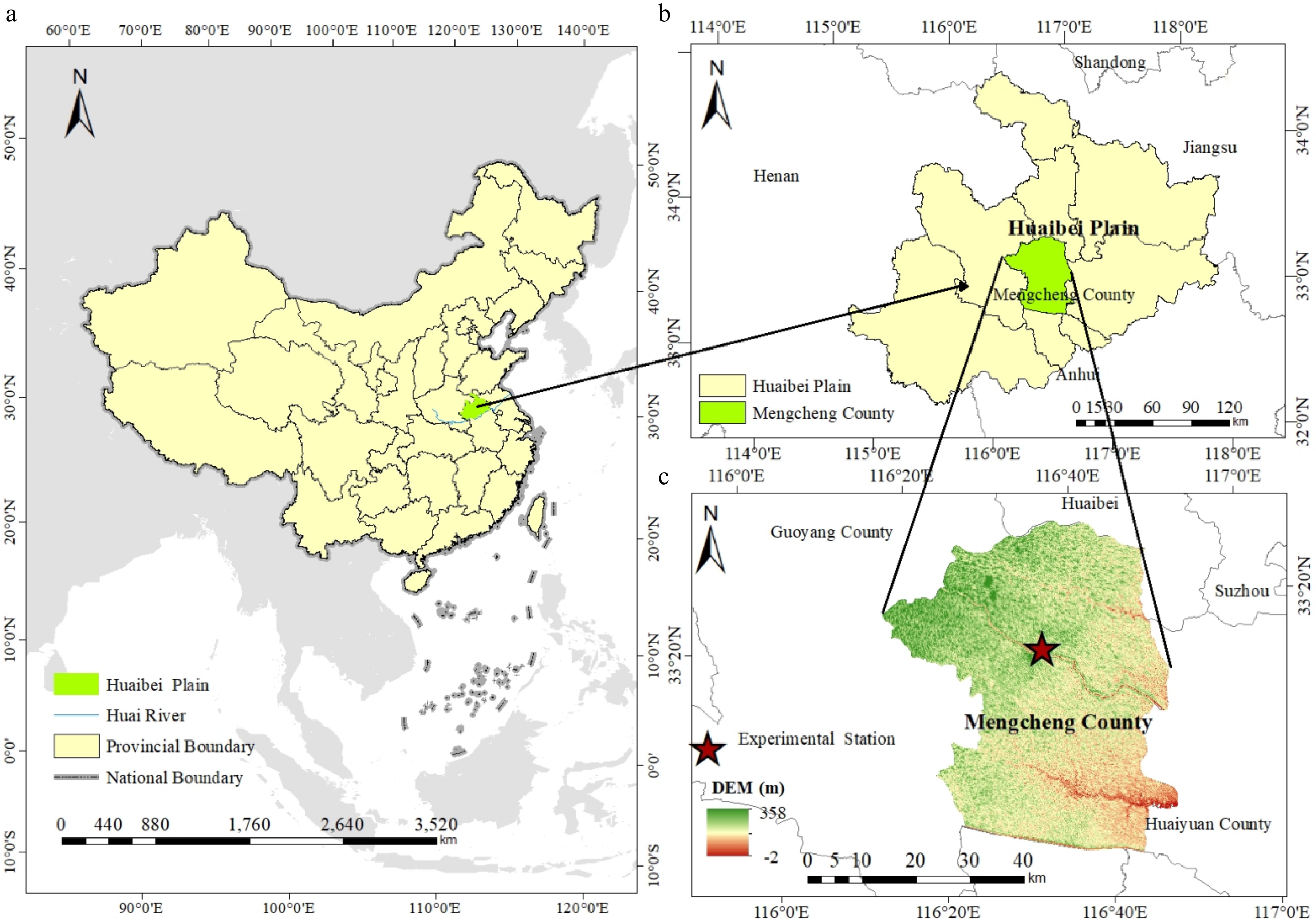

A two-year field experiment was conducted during the 2022–2023, and 2023–2024 winter wheat growing seasons at the Agricultural Science and Technology Demonstration Farm in Mengcheng County, Bozhou City, Anhui Province, China (33°9′44″ N, 116°32′56″ E). The experimental site is situated in the Huaibei Plain, a southern part of the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain (Fig. 1), and experiences a typical warm-temperate semi-humid monsoon climate. Precipitation and daily temperature patterns during the experimental period are presented in Fig. 2. The soil type of the experimental field is classified as lime concretion black soil, and before the experiment, some soil samples from the 0–20 cm depth of this field were tested forpH (7.53), organic matter content (11.51 g·kg−1), total nitrogen content (0.96 g·kg−1), total nitrogen (108.5 mg·kg−1), available phosphorus (61.9 mg·kg−1), and available potassium (189.7 mg·kg−1).

Figure 2.

Monthly precipitation and daily mean air temperature during the two winter wheat growing seasons.

Experimental design

-

The experiment employed the semi-winter wheat cultivar Wofeng 168 as the test material, which is a widely cultivated cultivar in the HP. Two irrigation methods were implemented: conventional flood irrigation (CI), with 60 mm applied at the jointing stage; and micro-sprinkler irrigation (SI), with 30 mm applied at both jointing and booting stages. In the 2022–2023 growing season, the soil moisture content in the 0–20 cm layer at the jointing and booting stages of wheat reached approximately 68.0% and 70.1% of the field water capacity, respectively. In the 2023–2024 growing season, the soil moisture content in the 0–20 cm layer at the jointing and booting stages of wheat reached roughly 77.3% and 70.1% of the field water capacity, respectively. The wheat growth stages were defined according to Zadoks' scale[26]. For each irrigation method, three topdressing nitrogen (N) levels—45 kg·ha−1 (N1), 90 kg·ha−1 (N2), and 135 kg·ha−1 (N3)—were superimposed on a basal N application of 112.5 kg·ha−1. A split-plot design was adopted for the experiment, with the irrigation method as the main plot and nitrogen level as the subplot. Micro-sprinkler irrigation utilized wheat-specific micro-sprinkler tape operating at 0.02 MPa with a flow rate of 6.0 m3·h−1[7]. The experimental plots, which measured 4 m by 40 m (160 m2) each, had three repetitions for each treatment. The wheat seeds were sown manually, and the row spacing for sowing was 20 cm, with 20 rows per plot. The planting density after seedling emergence was approximately 225 plants·m−2. Groundwater served as the irrigation source, with application volumes precisely measured using calibrated water meters. For all treatments, a basal fertilizer application of 112.5 kg·ha−1 P2O5 and 112.5 kg·ha−1 K2O was applied pre-sowing. Under conventional flood irrigation, nitrogen fertilizer was applied as a single surface broadcast before irrigation at the jointing stage. For micro-sprinkler irrigation, nitrogen fertilizer was split equally and applied along with irrigation water during both jointing and booting stages. The irrigation and fertilization schedules for different treatments are presented in Table 1. Other field management practices adhered to local conventional cultivation methods. Wheat was sown on October 22, 2022, and October 20, 2023, and harvested on June 7, 2023, and May 30, 2024.

Table 1. Irrigation and fertilization schedules in this study.

Treatment Irrigation amount (mm) N application amount (kg·ha−1) Jointing stage Booting stage Total Base fertilizer Jointing stage Booting stage Total CIN1 60.0 / 60.0 112.5 45.0 / 157.5 CIN2 60.0 / 60.0 112.5 90.0 / 202.5 CIN3 60.0 / 60.0 112.5 135.0 / 247.5 SIN1 30.0 30.0 60.0 112.5 22.5 22.5 157.5 SIN2 30.0 30.0 60.0 112.5 45.0 45.0 202.5 SIN3 30.0 30.0 60.0 112.5 67.5 67.5 247.5 Sampling and measurement

Soil moisture content

-

Soil samples were collected at different growth stages in the wheat growing seasons during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024, including the day after seed sowing (SS), jointing stage (JS), booting stage (BS), anthesis stage (AS), and maturity stage (MS). Each treatment had three replicates. A soil auger with a diameter of 40 mm was used, with samples collected at a depth of 60 cm at 10 cm intervals. After collection, soil samples were placed in aluminum boxes, weighed to record fresh weight, and then oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant weight. Dry soil weight was subsequently determined to calculate soil water moisture[27].

Leaf area index

-

At the anthesis stage, a 0.2 m2 sampling area (consisting of two adjacent 50-cm row sections) was selected per plot, with three replicates per treatment. The calculation formula of leaf area index (LAI) was as described by Jha et al.[28].

Chlorophyll content

-

At the anthesis stage and grain filling stage (20 d after anthesis), ten representative flag leaves were selected from each plot, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis, with three replicates per treatment. For chlorophyll content determination, 0.10 g of cut and well-mixed leaf samples was weighed and extracted with 25 ml 95% ethanol in the dark for 48 h. Absorbance (OD value) of the supernatant was measured at 665 and 649 nm using a UV-1800 spectrophotometer. Chlorophyll content was quantified following the ethanol extraction method[29].

Antioxidant enzymes and malondialdehyde (MDA) content

-

Sampling time and method were consistent with those used for flag leaf chlorophyll determination. For the assays, 0.10 g of chopped and mixed leaf samples was weighed and ground using a frozen grinder. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured by the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) photoreduction method; catalase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD) activities were determined via the UV absorption method; MDA content was assayed by the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) colorimetric method[30].

Root length density

-

At the anthesis stage, root samples were collected from the 0–60 cm soil profile using a root auger (10 cm diameter) at 10 cm depth intervals per plot. Roots and soil from each layer were placed in a dense nylon mesh, and residual soil was rinsed off with tap water before carefully picking out individual roots. Root images were acquired using a dedicated scanner (Gt-F5201; Epson, Tokyo, Japan). According to Li et al.[10], root length density was determined by analyzing the images using WinRHIZA Pro Vision 2009c software (Regent Instruments Inc., Québec, QC, Canada).

Dry matter accumulation

-

At the anthesis and maturity stages, 0.2 m2 wheat plant samples were taken from each plot. All samples were deactivated at 105 °C for 30 min, then dried at 75 °C to constant weight to calculate biomass. Post-anthesis dry matter accumulation (DMPA) was determined by the difference between dry weight at maturity and dry weight at anthesis. The contribution rates of DMPA to grain yield (CR) were the ratio of post-anthesis dry matter accumulation to grain yield[31].

Grain yield and components

-

At the maturity stage, 2 m2 of spikes were randomly selected from each plot, threshed manually, and converted to grain yield. The number of spikes was calculated by investigating 1 m2 of spikes in each plot. Thirty spikes were randomly selected from each plot to determine grains per spike. A 1,000 grains were randomly selected from the yield samples of each plot, dried, and weighed to calculate the 1,000-grain weight. Each treatment had three replicates. Both grain yield and 1,000-grain weight in this study were converted to 13% moisture content.

Statistical analysis

-

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, New Mexico, USA) and SPSS software version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to evaluate the effects of different irrigation methods and topdressing nitrogen levels on various winter wheat parameters. The statistical differences of various treatment means were performed using Duncan's test at a 0.05 probability level. Figures and tables were generated using Origin 2024 software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA).

-

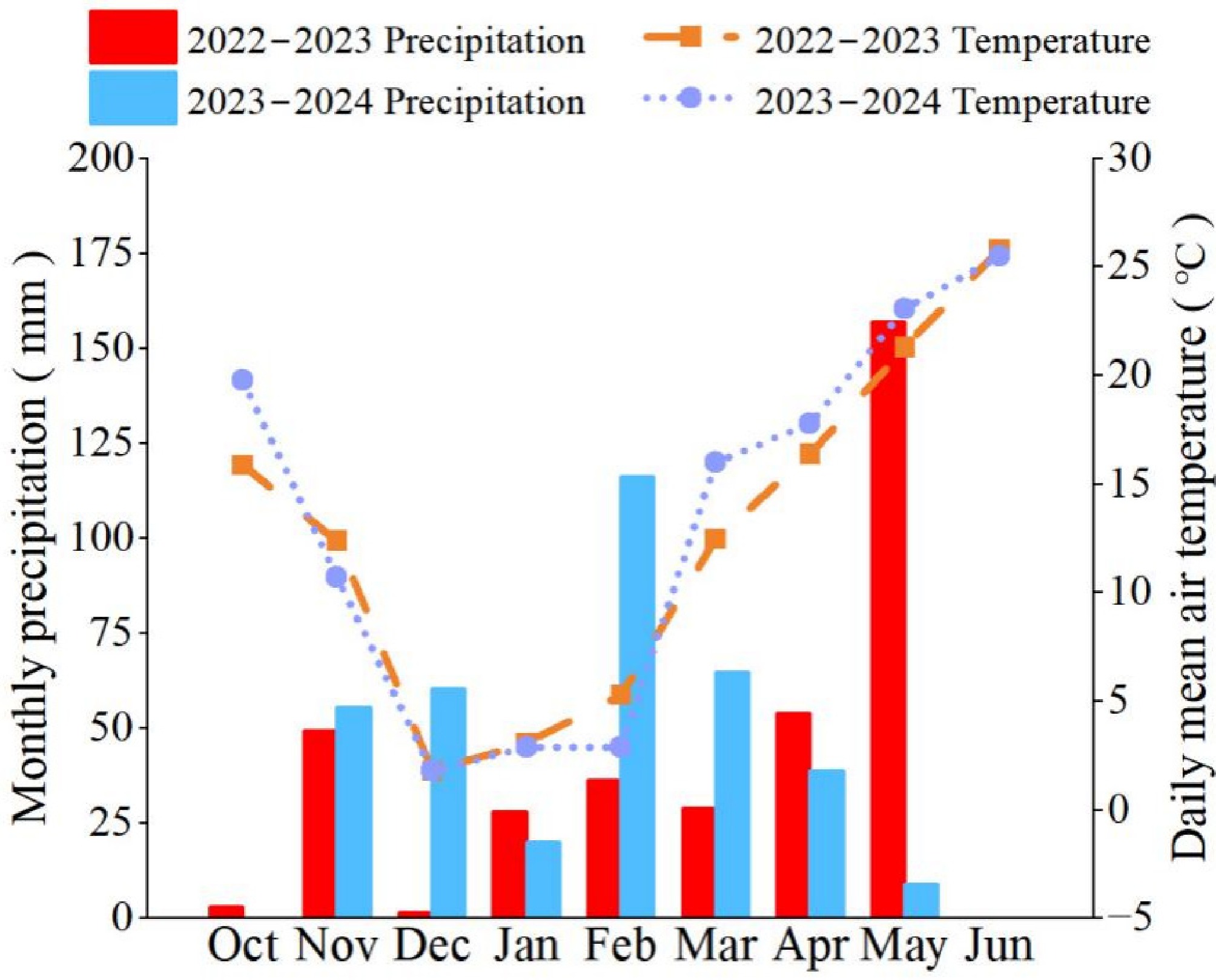

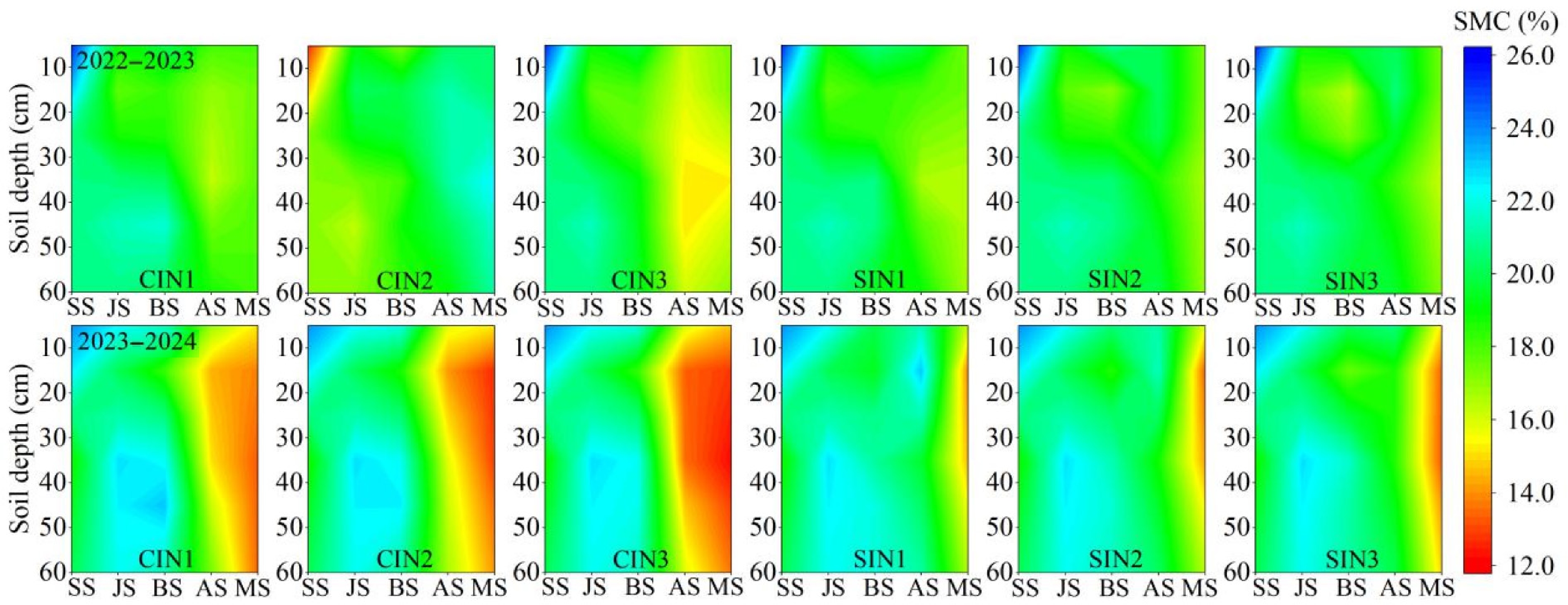

As shown in Fig. 3, at the booting stage, results from the two-year results showed that, under the same topdressing nitrogen level, the SMC in the 0–60 cm soil layer under micro-sprinkler irrigation (SI) was significantly lower than that under conventional flood irrigation (CI), except for the N2 treatment in 2022–2023, where the SMC under SI was significantly higher than that under CI. Under the same irrigation method, the SMC decreased progressively with increasing nitrogen application. Among all treatments, SIN3 exhibited significantly the lowest SMC, while CIN1 was the highest. At anthesis stage, under the same nitrogen level, the SMC in 0–60 cm soil layer under SI was significantly higher than that under CI; under CI, the SWC in the 0–20 cm soil layer under N1 was significantly higher than that under N2, and N2 was significantly higher than that under N3, while the SMC in the 20–60 cm soil layer under N2 was significantly higher than N1, and N3 was the lowest. Under SI, in 2022–2023, the SMC in 0–20 cm soil layer under N3 was significantly higher than that under N2 and N1, and N1 was significantly lower than N2, the SMC in the 20–60 cm soil layer under N2 was significantly higher than that under N1, and N1 was higher than N3, while in 2023–2024, the SMC in 0–60 cm soil layer under N1 was the highest. At the maturity stage, under the same nitrogen level, the SMC in the 0–60 cm soil layer under SI was significantly higher than that under CI, except for N1 in 2022–2023, where the SMC under CI was significantly higher than that under SI; under the same irrigation method, the SMC in the 0–60 cm soil layer under N1 was significantly higher than that under N2, and N2 was significantly higher than that under N3.

Figure 3.

Soil moisture content in different soil layers (0–60 cm profile) for different treatments during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 growing seasons. Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2, and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. SS, sowing stage; JS, jointing stage; BS, booting stage; AS, anthesis stage; MS, maturity stage.

Leaf area index (LAI)

-

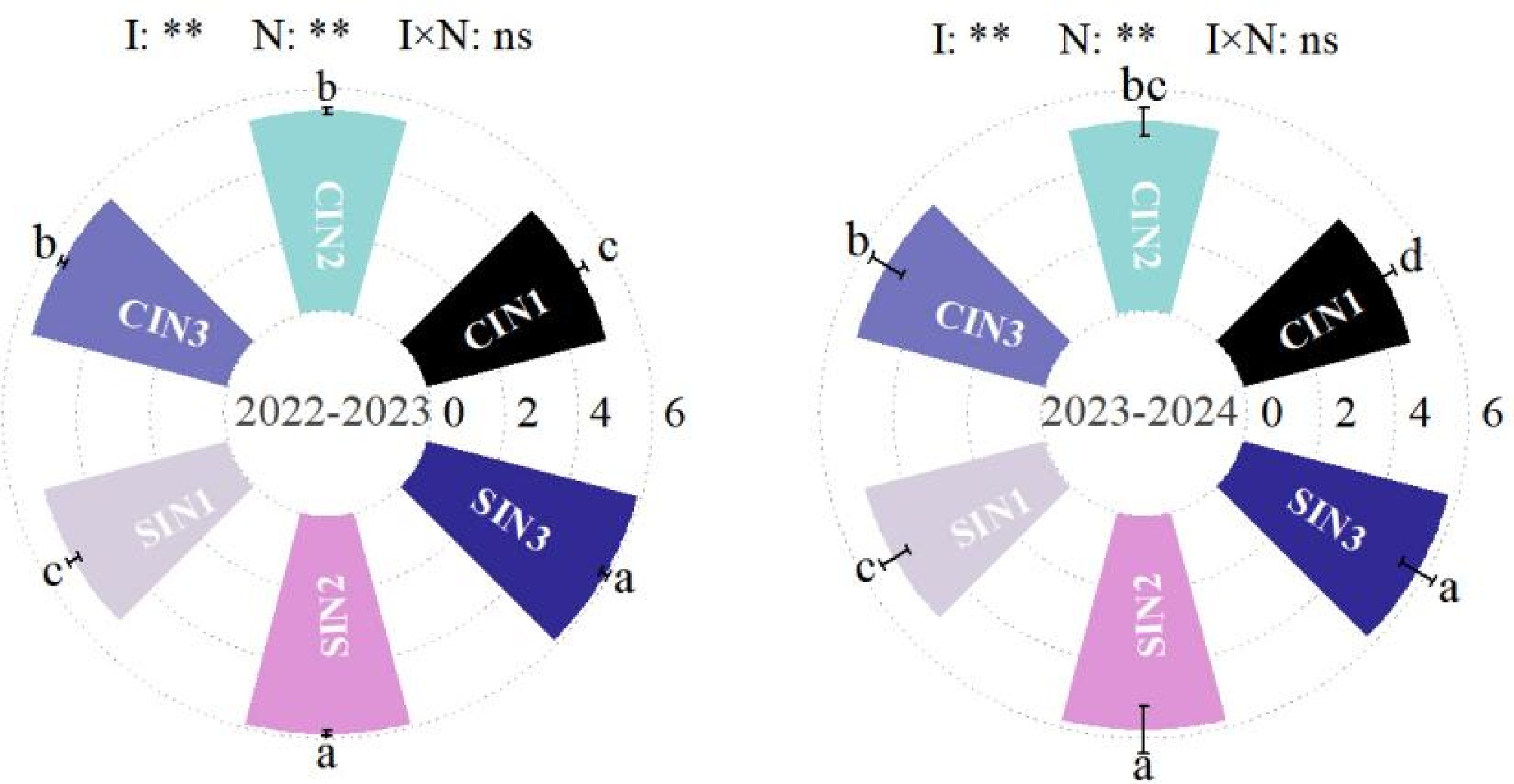

As shown in Fig. 4, both irrigation methods (I) and nitrogen application levels (N) significantly affected the LAI at anthesis, but the interaction between them was not significant. Under the same irrigation method, the LAI under N3 and N2 was significantly higher than that under N1, with no significant difference between the former two. At the same nitrogen level, the LAI under SI was significantly higher than that under CI, except for no significant difference between CIN1 and SIN1 in 2022–2023, and between CIN3 and SIN3 in 2023–2024. In conclusion, the results of this study indicated that micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer and N2 nitrogen level could maintain a higher LAI at anthesis of wheat, and further increasing nitrogen application did not lead to further improvement in LAI.

Figure 4.

Population leaf area index at the anthesis stage for different treatments during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 growing seasons. Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2 and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05, and the vertical bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3). I indicates the irrigation methods, N indicates the nitrogen application levels, and I × N indicates the interaction. ** represents the significant difference at the 0.01 level; ns represents that the difference is not significant.

Chlorophyll content

-

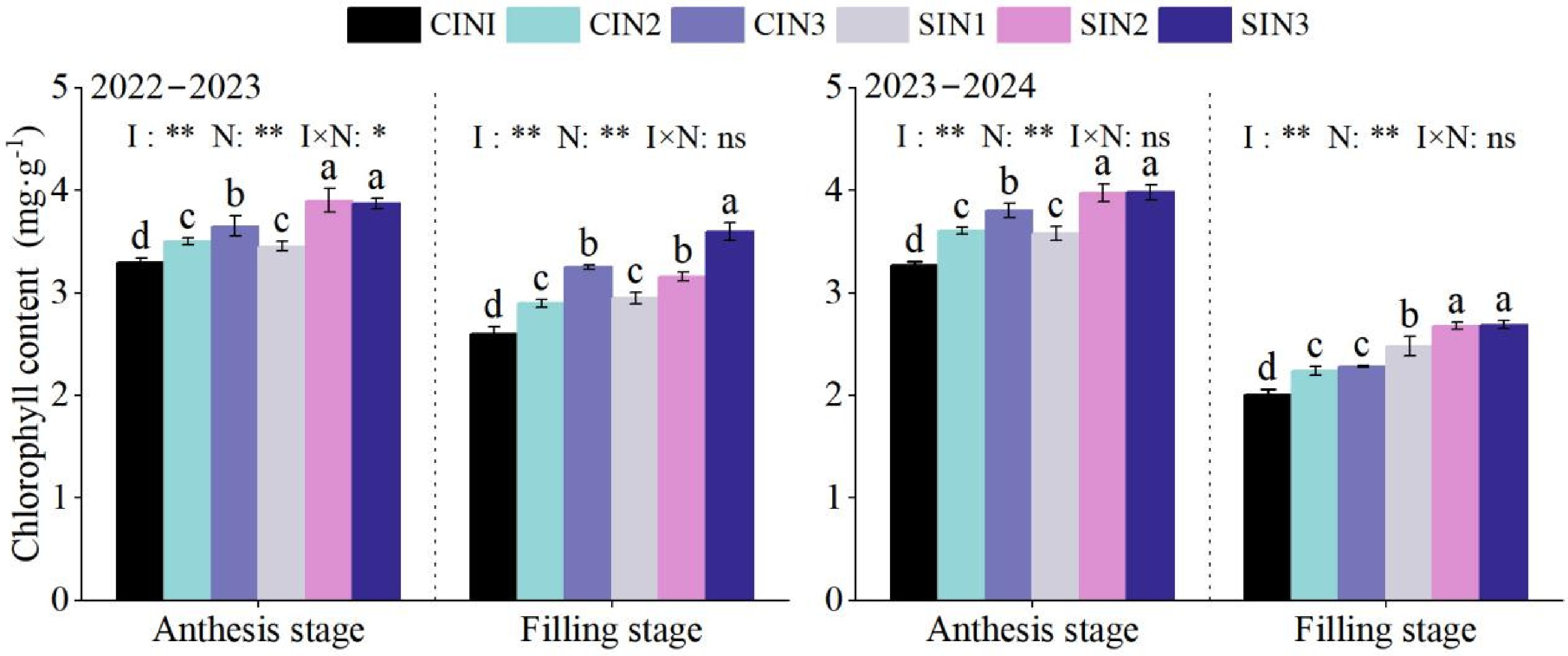

As shown in Fig. 5, both irrigation methods (I) and nitrogen application levels (N) significantly affected the flag leaf chlorophyll content at anthesis and grain filling stages, with no interaction effect except at anthesis in 2021–2022. Across the two growing seasons, the chlorophyll content at the anthesis stage was significantly higher than that at the grain filling stage. At the anthesis stage, the chlorophyll content in N1 was significantly lower than in N2 under CI, and N2 was significantly lower than in N3. While under SI, there was no significant difference between N2 and N3, both of them significantly higher than N1. At the grain filling stage, the chlorophyll content significantly increased with increasing nitrogen application rate in the first year, but in 2023–2024, the chlorophyll content under N2 and N3 was significantly higher than that under N1, with no significant difference between N2 and N3. At the same nitrogen level, except for N3, flag leaf chlorophyll content under SI was significantly higher than that under CI. In conclusion, compared with conventional flood irrigation and fertilization, micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer could significantly delay leaf senescence during the grain filling stage.

Figure 5.

Flag leaf chlorophyll content at the anthesis stage and filling stage (20 d after anthesis) for different treatments during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 growing seasons. Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2, and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05 (n = 3). Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05, and the vertical bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3). I indicates the irrigation methods, N indicates the nitrogen application levels, and I × N indicates the interaction. * and ** represent the significant difference at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively, ns represents that the difference is not significant.

Flag leaf antioxidant enzyme activity

-

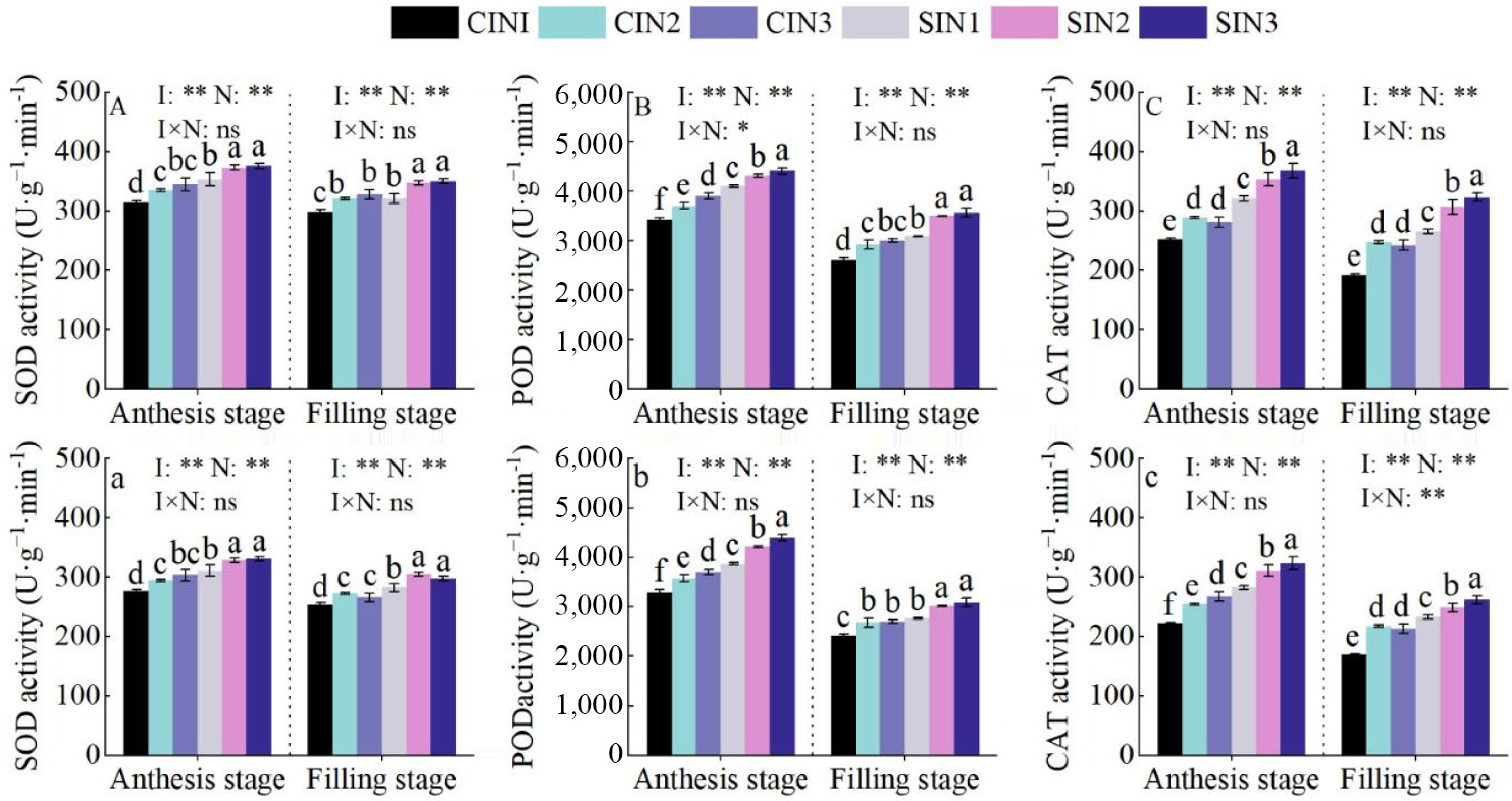

As shown in Fig. 6, both irrigation methods (I) and nitrogen application levels (N) significantly effected on the flag leaf SOD, POD, and CAT, with no interaction effect on these enzyme activities at the anthesis and grain filling stages except for POD activity at anthesis in 2022–2023 and CAT at grain filling stage in 2023–2024. Across the two growing seasons, SOD, POD, and CAT activities in the flag leaf decreased during the post-anthesis grain filling period. Under CI, at the anthesis stage, the activity of SOD and CAT in the first year showed no significant difference between N2 and N3, while the activities of POD and CAT in the second year significantly increased with increasing nitrogen application level. Under SI, the flag leaf SOD activity showed N1 significantly lower than N2 and N3, with no significant difference between the latter two, while the POD and CAT activities significantly increased with increasing nitrogen application levels. At the grain filling stage, except for the CAT activity under SI significantly increased with increasing nitrogen application level, the two-year results showed that under the same irrigation method, the SOD, POD, and CAT activities under N1 were significantly lower than those in N2 and N3, with no significant difference between the latter two. At the same nitrogen application level, the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT under SI were significantly higher than those in CI at the anthesis and grain filling stages. In conclusion, compared with the conventional flood irrigation and fertilization, micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer could significantly enhance antioxidant enzyme activity in flag leaf during the grain filling stage; however, excessive nitrogen application under micro-sprinkler irrigation did not further enhance leaf stress resistance.

Figure 6.

Flag leaf antioxidase activity at the anthesis stage and filling stage (20 d after anthesis) for different treatments during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 growing seasons. Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2, and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05, and the vertical bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3). I indicates the irrigation methods, N indicates the nitrogen application levels, and I × N indicates the interaction. * and ** represent the significant difference at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively, ns represents that the difference is not significant.

Flag leaf malondialdehyde (MDA) content

-

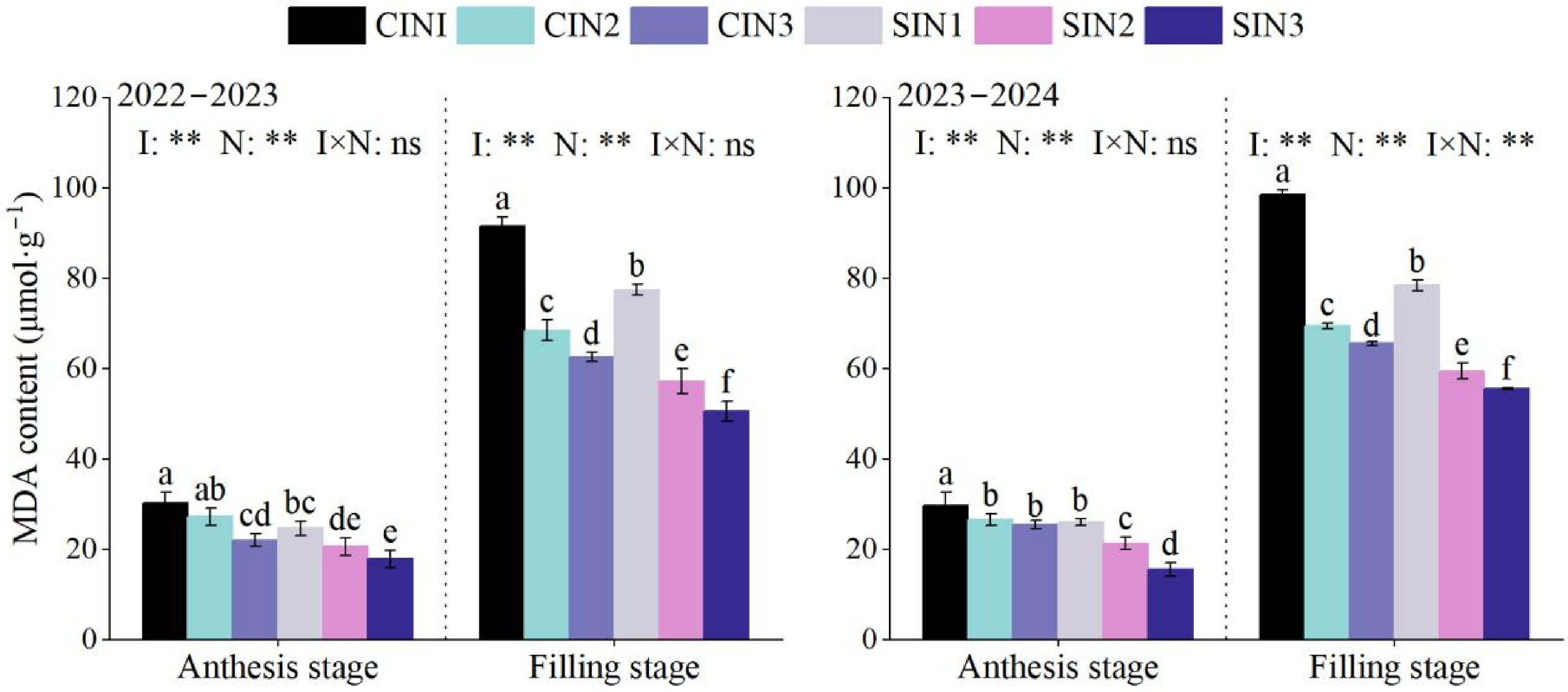

As shown in Fig. 7, both irrigation methods (I) and nitrogen application levels (N) significantly affected the flag leaf MDA content at the anthesis and grain filling stages, with no interaction effect except at the grain filling stage in 2023–2024. Across the two growing seasons, the MDA content increased continuously during post-anthesis grain filling. Under the same irrigation method, except for no significant difference between N2 and N3 at anthesis under SI in 2022–2023, and under CI in 2023–2024, the MDA content significantly decreased with increasing nitrogen application level at both stages. At the same nitrogen level, the MDA content under SI was significantly lower than that under CI. In conclusion, compared with the conventional flood irrigation and fertilization, micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer could significantly reduce MDA accumulation in leaves at grain filling stage, and MDA decreased with increasing nitrogen application levels.

Figure 7.

Flag leaf MDA content at the anthesis stage and filling stage (20 d after anthesis) for different treatments during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 growing seasons. Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2, and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05 (n = 3). Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05, and the vertical bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3). I indicates the irrigation methods, N indicates the nitrogen application levels, and I × N indicates the interaction. ** represents the significant difference at the 0.01 level, ns represents that the difference is not significant.

Root distribution

-

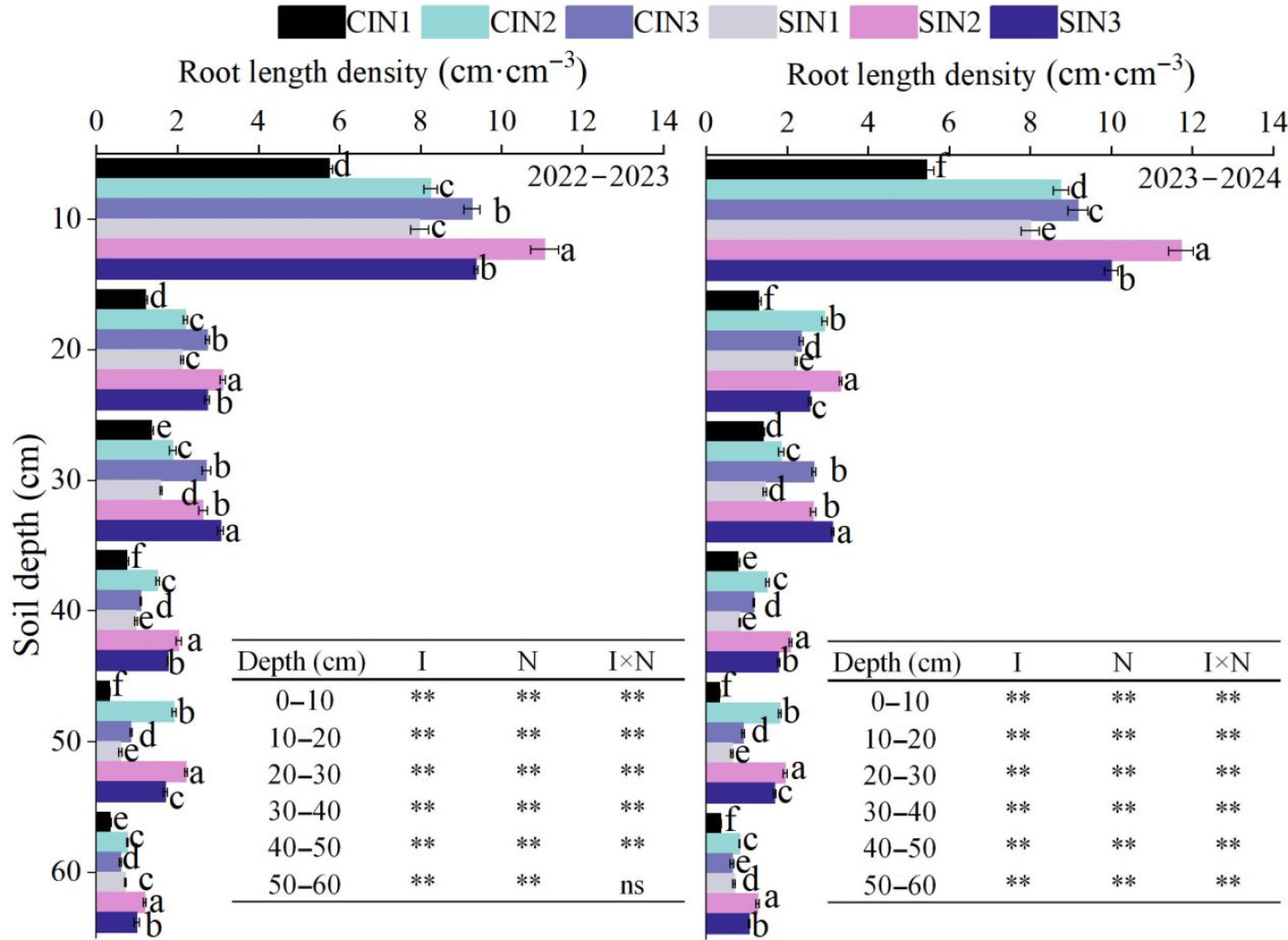

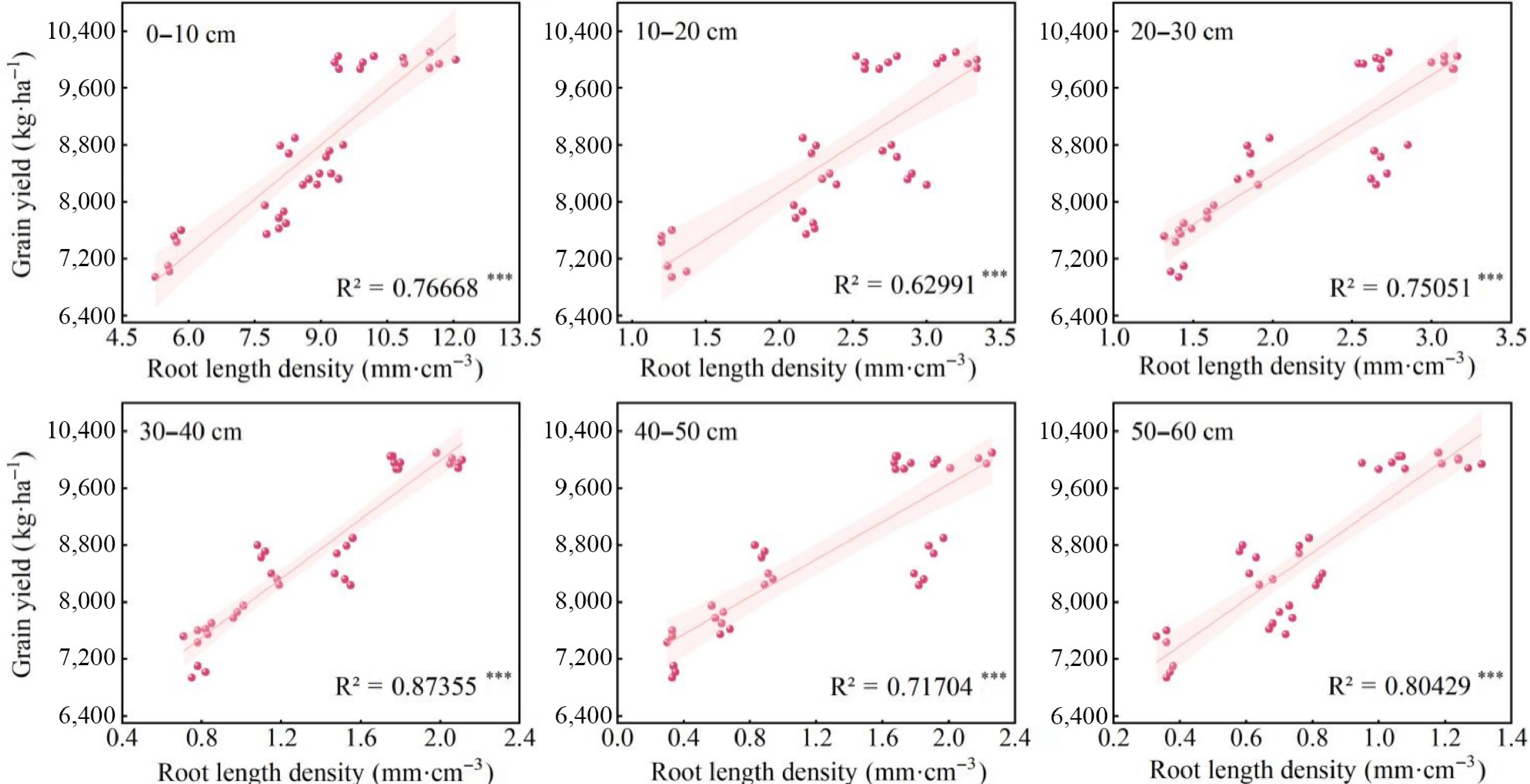

As shown in Fig. 8, the root length density (RLD) in different soil layers at wheat anthesis was significantly affected by both irrigation methods (I) and nitrogen application levels (N), with an interaction effect (I × N) observed except in the 50–60 cm soil layer in 2022–2023. Under CI, the proportions of root distribution in the 0–40 cm soil profile to total roots under N1, N2, and N3 were 93.45%, 86.69%, and 90.81%, respectively, while under SI, they were 90.21%, 85.32%, and 85.96%. In 2022–2023, under the same irrigation method, the RLD of the 0–30 cm soil layer significantly increased with the increase of topdressing nitrogen level in CI, and N1 was significantly lower than N2 and N3 in the 30–60 cm soil layer; N2 was the highest. For SI, except for N1 < N2 < N3 in 20–30 cm soil layer, the RLD of other soil layers showed that N1 < N3 < N2. In 2023–2024, the differences among different treatments at the anthesis stage were basically consistent with 2022–2023, except that the RLD under CI in the 10–20 cm soil layer showed that N1was significantly lower than N2 and N3, N2 was the highest. At the same nitrogen level, in 2022–2023, except for the 10–20 cm soil layer, the RLD under CI was lower than that in SI. In the 10–20 cm soil layer, the trend was consistent with other treatments under N1, and the RLD in CI was significantly lower than that of SI under N2, and no significant difference between the two under N3. In 2023–2024, except for the 20–40 cm soil layer, the RLD under CI was lower than that in SI. In 20–40 cm soil layer, the RLD in CI was significantly lower than that of SI under N2 and N3, and no significant difference between different irrigation methods under N1. Overall, these findings indicate that, compared with the conventional flood irrigation and fertilization, micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer and appropriate nitrogen application level is more conducive to promote root growth to deep soil layers. Correlation analysis revealed that there was an extremely significant (p < 0.001) positive correlation between RLD of each layer and grain yield (Fig. 9).

Figure 8.

Root length density in the 0-60 cm soil profile at the anthesis stage for different treatments during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 growing seasons. Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2, and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05 (n = 3). Various letters stand for significant differences at p < 0.05 and the horizontal bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3). I indicates the irrigation methods, N indicates the nitrogen application levels, and I × N indicates the interaction. ** represents the significance at the 0.01 level, ns represents that the difference is not significant.

Figure 9.

Correlation of root length density under different soil layer with grain yield of winter wheat in this study. *** represents the significance at 0.001 level.

Dry matter production

-

As shown in Table 2, the irrigation methods (I) significantly affected the total dry matter accumulation at maturity (DMM), post-anthesis dry matter accumulation (DMPA), and the contribution rate post-anthesis dry matter accumulation to grain (CR). During the 2022–2023 growing season, the nitrogen application levels (N) had an extremely significant effect on the dry matter accumulation at anthesis stage (DMA), DMM, and DMPA, and the DMPA was significantly affected by the interaction effect (I × N). Under the same irrigation method, compared with N1, N2, and N3 significantly increased the DMA and CR. In 2022–2023, under the same irrigation method, DMA in N1 was lower than that in N2, and N3, with no significant difference between N2 and N3; under the same nitrogen application rate, DMA in SI was higher than that in CI. The performance of DMM under the same irrigation method was consistent with that of DMA. Under the same nitrogen application level, there was no significant difference between the two irrigation methods at the N1 level; DMM in N1 was lower than that in N2 and N3, with no significant difference between N2 and N3. Under the same irrigation method, DMPA in N2 was higher than that in N3, and DMPA in N3 was higher than that in N1; compared with N1, DMPA in N2 and N3 increased by 24.6% and 13.6%, respectively. Under the same nitrogen application level, DMPA in CI was lower than that in SI at both N1 and N2 levels. Under the same irrigation method, CR in N2 was higher than that in N1 and N3. Under the same nitrogen application level, CR in CI was lower than that in SI. In 2023–2024, the performances of DMA and DMM among various treatments were consistent with those in 2022–2023. For DMPA, it was lower in CI than in SI under the N3 level. In conclusion, compared with the conventional flood irrigation and fertilization, the appropriate nitrogen application level under the integrated micro-sprinkler irrigation with water and N-fertilizer is beneficial to promoting the production of dry matter in wheat populations, and improving the post-anthesis dry matter accumulation and its contribution rate to grain yield.

Table 2. Effects of different treatments on the above-ground dry matter accumulation and the contribution ratio of dry matter accumulation post-anthesis to grain yield of winter wheat.

Treatment Dry matter accumulation in 2022–2023 Dry matter accumulation in 2023–2024 DMA (kg·ha−1) DMM (kg·ha−1) DMPA (kg·ha−1) CR (%) DMA (kg·ha−1) DMM (kg·ha−1) DMPA (kg·ha−1) CR (%) CIN1 11,646.52b 16,974.12d 5,327.60f 71.30c 11,533.30b 16,081.33c 4,548.03c 64.80c CIN2 11,944.90ab 18,582.00b 6,637.10c 75.51b 12,452.80a 18,503.30b 6,050.50b 67.69b CIN3 12,004.53ab 18,058.93bc 6,054.40d 72.60c 12,851.17a 18,384.93b 5,533.77b 66.38b SIN1 11,689.62b 17,475.42cd 5,785.80e 74.12bc 10,431.20c 16,404.80c 5,973.60c 68.11c SIN2 12,169.93a 20,067.83a 7,897.90a 78.83a 11,764.13b 19,185.27a 7,421.13a 74.54a SIN3 12,219.67a 19,513.67a 7,294.00b 75.82b 11,829.00b 18,971.77a 7,142.77a 76.67a ANOVA I ns ** ** ** ** ** ** ** N ** ** ** ** ** ** ** ** I×N ns ns ** ns ns ns ns * Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2, and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. DMA, dry matter accumulation at anthesis stage. DMM, dry matter accumulation at maturity stage; DMPA, post-anthesis dry matter accumulation; CR, the contribution rate of dry matter accumulation post-anthesis to grain yield. Different lowercase letters within a column indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05. I indicates the irrigation methods, N indicates the nitrogen application levels, and I × N indicates the interaction. * and ** represent the significant difference at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively, ns represents that the difference is not significant. Grain yield and its components

-

As shown in Table 3, except for no significant effect of irrigation methods (I) on spike number in 2023–2024, I and nitrogen application levels (N) significantly affected grain yield (GY) and yield components, with GY being affected by their interaction (I × N). Under the same irrigation method, there was no significant difference in GY between N2 and N3, and N1 was the lowest. Compared with N1, the GY increases under N2 and N3 were 16.93%–27.49% and 15.91%–26.67% in 2022–2023, and 18.52%–30.39% and 18.55%−30.65% in 2023–2024, respectively. In terms of yield components, except for thousand-grain weight (TGW) under CI in 2022–2023, which significantly increased with the increase of nitrogen application level, and the N2 and N3 significantly increased spike number (SN), kernel number per spike (KN), and TGW compared with N1 under the same irrigation method. At the same nitrogen application level, compared with CI, SI significantly increased the KN and TGW, thereby significantly increasing GY, with increases of 4.57%–14.28% in 2022–2023, and 7.63%–19.70% in 2023–2024, respectively. In conclusion, compared with the conventional flood irrigation and fertilization, micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer, and an appropriate nitrogen application level can significantly increase wheat yield, while excessive nitrogen application cannot further increase yield.

Table 3. Effects of different treatments on grain yield and yield components of winter wheat.

Treatment 2022–2023 2023–2024 GY (kg·ha−1) SN (× 104·ha−1) KN TGW (g) GY (kg·ha−1) SN (× 104·ha−1) KN TGW (g) CIN1 7,517.78 d 573.48 c 37.19 d 42.18 d 7,019.30 d 562.55 b 36.88 d 42.60 d CIN2 8,790.80 b 609.18 b 40.55 b 45.21 b 8,319.44 b 604.03 a 40.19 b 44.82 b CIN3 8,714.15 b 615.85 ab 40.43 b 45.17 b 8,321.11 b 602.70 a 40.15 b 44.31 b SIN1 7,861.71 c 579.68 c 39.19 c 43.58 c 7,623.81 c 564.22 b 38.51 c 43.48 c SIN2 10,022.73 a 625.88 a 43.48 a 47.72 a 9,940.51 a 607.11 a 41.34 a 47.49 a SIN3 9,958.53 a 627.19 a 42.91 a 47.19 a 9,960.48 a 605.22 a 41.16 a 47.20 a ANOVA I *** ** *** *** *** ns *** *** N *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** I × N * ns ns ns *** ns ns *** Note: CI, conventional flood irrigation; SI, micro-sprinkler irrigation; N1, N2 and N3 represent topdressing nitrogen with 45 kg·ha−1, 90 kg·ha−1, and 135 kg·ha−1 respectively. GY, grain yield; SN, spike number; KN, kernel number per spike; TGW, thousand-grain weight. I indicates the irrigation methods, N indicates the nitrogen application levels, and I × N indicates the interaction. Different lowercase letters within a column indicate significant differences p ≤ 0.05 *, **, and *** indicate significant difference at p ≤ 0.05, ≤ 0.01, and ≤ 0.001, respectively, ns represents that the difference is not significant. Correlation analysis among different traits

-

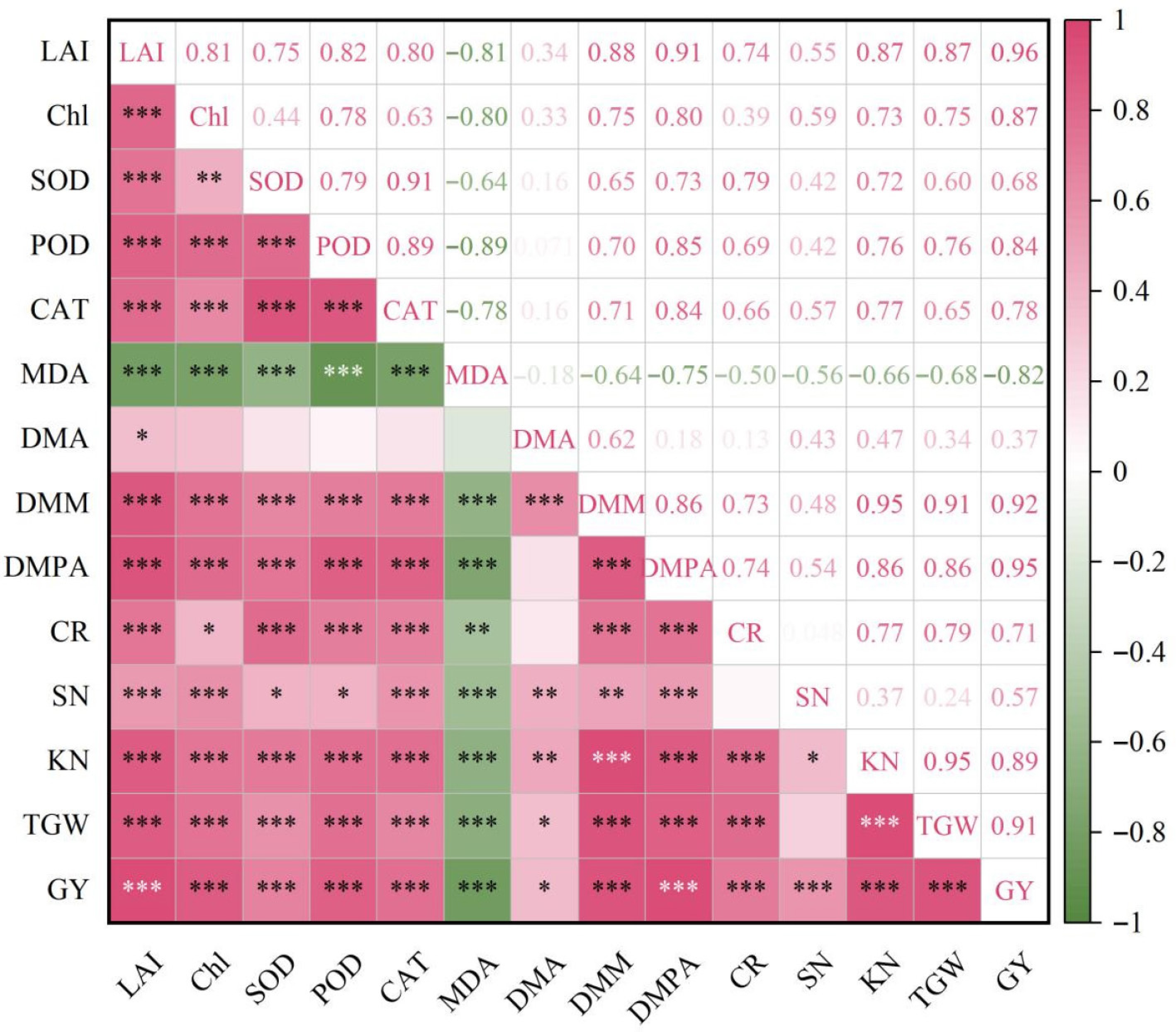

As shown in Fig. 10, in this study, by analyzing the correlation between indicators, it was found that there was no significant correlation between the DMA and flag leaf chlorophyll content (Chl), SOD, POD and CAT of grain filling stage, DMPA, and CR (p > 0.05), while there were significant (p < 0.05), or extremely significant (p < 0.01) correlations between other indicators. In terms of the correlation between different indicators and GY, except that there was an extremely significant negative correlation between GY and MDA of grain filling stage (p < 0.001) and a significant correlation between DMA and GY (p < 0.05), other indicators all had an extremely significant positive correlation with GY (p < 0.001).

Figure 10.

Relationships between different parameters and grain yield in this study. Different colors indicate the intensity of the significant, and the closer to red (positive) or green (negative), the higher for the significant. * Represents the significance at the 0.05 level, ** represents the significance at the 0.01 level, and *** represents the significance at the 0.001 level, respectively.

-

Leaves, as the primary photosynthetic organs in crops, exhibit a direct relationship between their photosynthetic capacity and key physiological parameters including leaf area index (LAI), chlorophyll content, and antioxidant capacity[32]. The present findings confirm this (Fig. 10). Research has shown that supplementary irrigation and topdressing nitrogen application during the key growth stages can significantly increase antioxidant enzyme activity in flag leaf, maintain high chlorophyll content after anthesis, delay leaf senescence, and promote dry matter accumulation of wheat[10]. In this study, micro-sprinkler irrigation, combined with optimal topdressing nitrogen application (SIN2) significantly increased LAI at anthesis (Fig. 4), enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity at the anthesis and grain filling stages (Fig. 6), reduced MDA content (Fig. 7), significantly increased flag leaf chlorophyll content (Fig. 5), and ultimately increased wheat post-anthesis dry matter accumulation (Table 2). This is consistent with a previous report that rational water and nitrogen management can extend the functional period of leaves, enhance crop photosynthetic capacity, and thus promote grain yield (GY)[33].

An optimal LAI serves as a critical regulator of crop source-sink relationships. Previous research has demonstrated that the elevated topdressing nitrogen rates promote vegetative organ development and leaf expansion, thereby enhancing LAI[34]. In this study, under the same irrigation method, the N2 significantly increased LAI of the anthesis stage compared with N1 (Fig. 4), but there was no significant difference between N2 and N3. Under the same topdressing nitrogen level, micro-sprinkler irrigation significantly increased the LAI compared with conventional flood irrigation (Fig. 4), which is consistent with previous findings[22,35]. However, the antioxidant enzymes activity under N1 were significantly lower than that under N2 and N3 under the same irrigation method, with no significant difference between N2 and N3 (Fig. 6). This may be because, when leaf nitrogen content is insufficient, chlorophyll degradation causes an imbalance in light energy capture and electron transport, preventing the reactive oxygen species (ROS) from synthesizing sufficient antioxidant enzymes. Conversely, when leaf nitrogen content is excessive, enzyme activity does not further increase due to nitrogen saturation in leaf[36]. Under identical topdressing nitrogen level, SI significantly enhanced the activities of POD, SOD, and CAT compared to CI (Fig. 6), while significantly reducing MDA content (Fig. 7), which aligns with previous studies[30]. According to the two-year chlorophyll content data (Fig. 5), at the grain filling stage, the flag leaf chlorophyll content in the 2022–2023 growing season increased significantly with higher nitrogen application levels, with N3 significantly higher than N2. In the 2023–2024 growing season, however, chlorophyll content under N2 and N3 was significantly higher than that under N1, with no significant difference between them. This discrepancy may be because post-anthesis precipitation in 2023–2024 was significantly lower than that in 2022–2023, and temperature was higher than that in 2022–2023 (Fig. 2), resulting in significantly lower soil water at the grain filling stage in the second year (Fig. 3). Under such water-limited conditions, elevated soil nitrogen supply may enhance leaf chlorophyll synthesis[37,38].

Dry matter accumulation of wheat serves as the foundation for grain yield and is closely linked to crop yield[39,40]. It is generally acknowledged that approximately 70% of grain yield originates from post-anthesis dry matter accumulation, and increasing the accumulation amount can significantly boost wheat yield[41]. Rational water and nitrogen management can enhance post-anthesis dry matter accumulation and its contribution to grain yield[9,22]. In this study, under the same irrigation method, both the DMA and DMM, along with CR, were significantly lower under N1 than under N2 and N3. This phenomenon may be related to lower LAI and decreased leaf stress resistance under low nitrogen conditions, which lead to premature senescence (Figs 4−6). The little difference between N2 and N3 might be attributed to the fact that topdressing nitrogen beyond N2 did not significantly improve leaf material production capacity. However, under the same topdressing nitrogen level, SI significantly increased DMPA and CR compared to CI. This could be related to the significant increase in post-anthesis SWC (Fig. 3), flag leaf chlorophyll content (Fig. 5), and antioxidase enzyme activities under SI (Fig. 6).

Effects of micro-sprinkler irrigation combined with an appropriate nitrogen application level on wheat root distribution

-

Roots are the main organs for crops to absorb water and nutrients from soil, and their growth and development directly influence above-ground plant growth. In this study, it was also found that the root growth is closely related to wheat yield (Fig. 9). Current research indicates that the rational irrigation regimes and N-fertilizer application can regulate root growth, facilitating a reasonable distribution of roots in the soil profile[42−44]. Concurrently, an optimal topdressing nitrogen level can significantly activate nitrogen signaling pathways, and induce roots to penetrate into the deep soil layer[45]. In this study, compared with CI, SI significantly promoted the root growth and deep penetration under the same nitrogen level, with significantly higher root length density (RLD) in surface and deep layers at the anthesis stage (Fig. 8). This finding differs from previous studies, potentially due to soil type effects[29]. In the HP region, the soil is mainly lime concretion black soil with clayey characteristics. The conventional flood irrigation at the jointing stage may reduce soil permeability, thus affecting root growth, while micro-sprinkler irrigation with split and small irrigation volumes enables uniform water infiltration, maintains soil permeability, and creates a more favorable environment for root development. Deep roots can not only enhance water absorption capacity in the later period but also delay leaf senescence by transporting cytokinins upward[46]. In this study, under the same irrigation method, N2 treatment had the most surface roots and promoted deep root distribution, which is consistent with previous studies[29,47]. In addition, some studies have shown that root growth is influenced not only by soil water but also by nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) concentration. A low NO3−-N concentration can significantly increase auxin content in roots and enhance root elongation[48]. However, an excessively low nitrogen application level may restrict root growth and development, inhibit root penetration into deep layers, and reduce the ability of the crop to obtain water and nutrients from the soil. In summary, micro-sprinkler irrigation combined with an appropriate nitrogen application (SN2) may optimize root architecture by improving the root zone environment. Simultaneously, the coordinated development of roots and above-ground parts promote dry matter accumulation; root penetration to deep layers enhances the absorption capacity of plants for water and nutrients, thereby supporting continuous photosynthesis of post-anthesis flag leaf, facilitating the translocation of assimilates to grains, and ultimately increasing the CR (Table 2). Furthermore, micro-sprinkler irrigation combined with optimal nitrogen application may regulate root growth by changing soil NO3−-N concentration during the key period of root growth (from jointing to anthesis). However, future studies need to further investigate whether NO3−-N concentration plays an important role in promoting root growth and development under optimal nitrogen application level for micro-sprinkler irrigation, thereby contributing to yield improvement.

Effects of micro-sprinkler irrigation combined with appropriate nitrogen application level on wheat grain yield (GY) and its components

-

GY of wheat is determined by three components: spike number (SN), kernels per spike (KN), and thousand-grain weight (TGW), all closely associated with water and nitrogen supply[49]. Achieving high GY typically requires increasing KN and TGW while maintaining adequate SN[25]. The jointing and booting stages are key periods for wheat KN formation, and represent sensitive periods for water and nutrient availability. Rational water and N-fertilizer application during this period can promote root penetration, thereby enhancing the material production capacity of wheat, which positively influences increases in KN and GY[10]. Research has shown that SI can effectively extend the post-anthesis leaf photosynthetic duration through multiple small-volume water applications, improve the post-anthesis dry matter accumulation and CR, and ultimately increase TGW and GY[21]. In this study, under the same irrigation method, the GY in N1 was significantly lower than that in N2 and N3, with no significant difference between N2 and N3 (Table 3). This is because insufficient nitrogen application may reduce wheat spike differentiation and pollen fertility, thereby affecting SN and KN[50]. The present study indicated that the SN in SI was significantly higher than CI under N2 during the 2022–2023 growing season of winter wheat, this may be due to the lower rainfall from the jointing to booting period in this year (Fig. 2). However, previous research result indicated that beyond a certain nitrogen application level, further increasing nitrogen application does not necessarily enhance yield[51]. This experiment proved that micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer combined with an appropriate nitrogen application level, extends the grain formation period through water and nitrogen synergy, ensures water supply during post-anthesis grain filling via split irrigation, increases the TGW, and ultimately promotes GY. Additionally, the lime concretion black soil area in the HP has the characteristics of heavy soil texture in rainy seasons and easy hardening in dry seasons. Under the micro-sprinkler irrigation with integrated water and N-fertilizer combined with an appropriate nitrogen application level (SIN2) provides sufficient nutrients at the key stages for wheat, maintains high soil water content (Fig. 3), promotes root growth into deep layers (Fig. 8), and achieves root-shoot coordination. This not only improves pre-anthesis photosynthetic production capacity and increases the LAI at anthesis (Fig. 4) but also delays post-anthesis leaf senescence (Figs 5−7) and promotes dry matter accumulation and translocation (Tables 2, 3), thereby significantly increasing wheat KN and TGW, and ultimately boosting GY (Table 3).

-

The results of this study demonstrated that in the HP region, micro-sprinkler irrigation with 30 mm at jointing and booting stages, combined with basal nitrogen application of 112.5 kg·ha−1, and topdressing nitrogen of 45 kg·ha−1 at each stage, can effectively maintain an appropriate soil moisture content during the critical growth periods of wheat, increase the LAI at anthesis, enhance post-anthesis flag leaf antioxidant enzymes activity and delay flag leaf senescence, promote root penetration into deep soil profile. These effects collectively increase in post-anthesis dry matter accumulation (DMPA) and CR, and ultimately boost GY by increasing KN and TGW. These findings indicate that micro-sprinkler irrigation, combined with an appropriate nitrogen application has significantly potential to ensure high wheat yields in the HP region. However, its economic and environmental benefits still require further exploration. Therefore, future research should focus on developing more refined water and nitrogen management in the future to better achieve synergistic improvement in both economic and environmental performance.

We sincerely appreciate the funding from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD2301505), an Anhui Agricultural University fund (yj2019-01), and the Planting Project of Modern Industrial Technology System of the '14th Five-year Plan' of Anhui Province (340000222426000100009).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, manuscript revision: Li J, Song H; material preparation, data collection, and analysis: Zhang L, Li H, Li B, Li Z, Hu Z, Wang S; manuscript draft writing: Zhang L; provided some very valuable suggestions: Yao C, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Li J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang L, Li H, Li B, Li Z, Hu Z, et al. 2026. Micro-sprinkler irrigation with optimal nitrogen application enhances winter wheat yield by regulating flag leaf physiology and root growth in the Huaibei Plain. Technology in Agronomy 6: e001 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0014

Micro-sprinkler irrigation with optimal nitrogen application enhances winter wheat yield by regulating flag leaf physiology and root growth in the Huaibei Plain

- Received: 13 September 2025

- Revised: 15 October 2025

- Accepted: 04 November 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: A two-year field experiment was conducted to explore the effects of conventional flood irrigation (CI), and micro-sprinkler irrigation (SI) under three topdressing nitrogen levels (N1, 45 kg·ha−1; N2, 90 kg·ha−1; N3, 135 kg·ha−1) on flag leaf physiology, root growth, and grain yield (GY) of winter wheat in the Huaibei Plain (HP). Results showed that higher N significantly decreased the soil moisture content, but SI had higher moisture than CI at the same N level. N2 and N3 significantly increased leaf area index (LAI) compared with N1, and the LAI in SI was higher than in CI. Chlorophyll content in N2 and N3 was significantly higher than in N1 during the grain filling stage, and SI further enhanced the content under the same N level—likely because higher N increased flag leaf antioxidant enzyme activity, while SI outperformed CI. At the anthesis stage, N2 had the highest root length density below 30 cm soil depth, with SI exceeding CI at the same N level. Therefore, N2 and N3 significantly increased dry matter accumulation at maturity (DMM), and the contribution rate of post-anthesis dry matter accumulation to GY (CR). SI further enhanced DMM and CR vs CI at the same N level. Compared to N1, N2 and N3 increased GY by 23.52% and 23.13%, respectively. SI significantly enhanced GY, ranging from 6.10% to 16.99% than CI. Overall, micro-sprinkler irrigation with optimal nitrogen application at jointing and booting stages effectively promoted root growth, enhanced leaf stress resistance, and delayed leaf senescence during grain filling, resulting in improved wheat yield in the HP.

-

Key words:

- Irrigation regimes /

- Nitrogen application /

- Root growth /

- Flag leaf physiology /

- Wheat yield