-

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) is the most economically significant fiber crop in the United States, serving as a vital raw material for the textile industry, generating substantial export revenues, and supporting rural economies (USDA, 2023). Within the Mid-South region—which encompasses Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, and parts of Alabama and Missouri—Tennessee holds a particularly important position. Although the state is not the largest cotton producer by acreage, its production is critical because of its integration into regional supply chains, the diversity of its soils and climate conditions, and its long-standing research and extension infrastructure. These factors make Tennessee a representative case for studying cotton production systems in the Southeastern US. Despite this importance, cotton production in Tennessee faces significant challenges due to climate variability[1]. The region is subject to unpredictable rainfall patterns, temperature extremes, and weather anomalies such as prolonged droughts and intense heat waves[2]. Such stressors disrupt key physiological processes in cotton, especially during flowering and boll development, and contribute to yield instability[3]. With the pace of climate change accelerating, these risks are expected to intensify, highlighting the urgent need to better understand crop responses and to develop resilient management strategies[4].

In response, an increasing body of research has emphasized the role of conservation agriculture in adapting to climate stress[5,6]. Practices such as reduced or no-tillage and the integration of winter cover crops can improve soil structure, enhance organic matter, regulate moisture dynamics, and stabilize yields under variable climatic conditions[7,8]. Among these, leguminous cover crops like hairy vetch and crimson clover are particularly valued for their ability to biologically fix atmospheric nitrogen, thereby reducing dependence on synthetic fertilizers while enriching soil fertility and stimulating microbial activity[9]. These ecological benefits extend beyond nutrient cycling to include improvements in soil resilience and overall system sustainability. Nevertheless, most existing studies are relatively short-term, often focusing on isolated management factors (e.g., tillage or cover crops) rather than assessing their combined and interactive effects over longer timescales. This limitation leaves an important research gap in understanding how integrated systems will perform under projected climate scenarios.

To address such gaps, process-based crop simulation models have become essential tools for exploring long-term impacts of management and climate interactions. The Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer (DSSAT) has emerged as one of the most widely validated and flexible modeling platforms for this purpose[10,11]. By integrating dynamic weather data, soil processes, and genotype-specific crop growth parameters, DSSAT allows researchers to evaluate cotton responses under diverse climatic and management conditions across multiple decades. Previous DSSAT-based studies have examined the effects of climate change on cotton yield in several US regions[12,13]; however, few have comprehensively considered the interactive impacts of tillage practices and legume-based cover crops under future climate projections. This knowledge gap is particularly critical in the Southeastern United States, where cotton systems remain both economically vital and highly vulnerable to climate-related risks.

This study used 33 years of field data (1986–2018) and high spatial resolution weather projections generated by the WRF model to drive DSSAT simulations. The objectives were to: (1) quantify long-term trends in cotton lint yield under four cover crop species and two tillage systems; (2) assess yield stability and interannual variability using YSI, PSI, and YVI indices; and (3) project future yields under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios for the years 2030, 2040, and 2050. This research contributes to climate-smart agriculture planning for the Southeastern United States by identifying the most resilient management strategies.

-

The study was conducted at the University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture's West Tennessee Research and Education Center (WTREC) in Jackson, TN, USA (35°37' N, 88°51' W, altitude 113 m). The study site features flat to gently rolling topography with slopes less than 2%. The soil at the location is classified as Lexington silt loam (fine-silty, mixed, thermic Ultic Hapludalfs), and its physical and chemical properties are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Soil physical and chemical properties at 0–15 and 15–30 cm depths in Jackson, TN, USA.

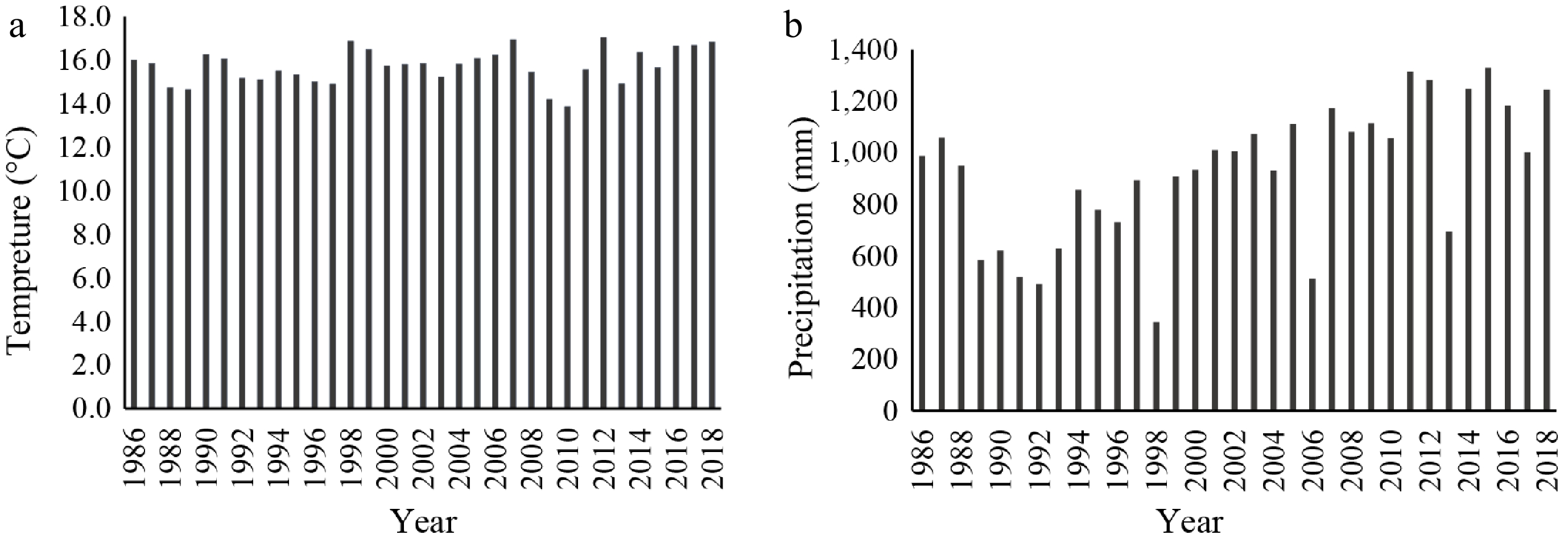

Depth (cm) Texture (g·kg−1) Organic C (mg·g−1) pH CEC (cmol·kg−1) Total N (mg·g−1) Bulk density (g·cm−3) 0−15 Silt: 660, clay: 165, sand: 175 6.1 6.4 20 1.01 1.51 15−30 Silt: 662, clay: 210, sand: 128 4.5 6.4 20 1.01 1.52 The climate of Jackson, TN, USA, is classified as humid subtropical (Köppen climate classification Cfa), with an average annual temperature of approximately 15.5 °C. The region receives an average annual precipitation of 1,375 mm. Weather data were collected using an automated weather station located at the WTREC. The station monitored daily and hourly weather variables, including temperature, precipitation, wind speed, relative humidity, and sunshine hours. Based on Fig. 1, it can be concluded that the years 1998, 2007, and 2012 were the hottest. The highest rainfall was observed in 2011 and 2015 (Fig. 1). According to future projections, the year 2050 will have the highest temperature and the lowest rainfall compared to the previous two decades. Over time, the summer months have shown the highest temperatures and the lowest rainfall across all three decades (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Monthly average temperature, and (b) precipitation during 2030, 2040, and 2050 in Jackson, TN, USA.

Field experiment

-

The field experiment was conducted under the complete combinations of two tillage systems: conventional tillage (CT, chisel plow) and no-tillage (NT), alongside four cover crop treatments: winter wheat (WW), hairy vetch (HV), crimson clover (CC), and a no-cover crop (NC). The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with a split-plot arrangement. Cover crop treatments were assigned to the main plots, while tillage systems were assigned to the subplots, with four replicates.

Each subplot had a size of 12 m by 8 m, with eight rows of cotton. The cotton crop was sown at a depth of 4 cm, targeting a plant density of approximately 86,500 plants per hectare. The tillage treatments were double-disked to a depth of 10 cm and harrowed to prepare the seedbed. Throughout the study period, different cotton cultivars were planted, including Stoneville 825, Deltapine 50, Stoneville 474, Deltapine 425, Deltapine 451, and Phytogen 375. Irrigation was applied based on soil water content in the effective root zone. Cotton was harvested mechanically and ginned annually, with lint yield recorded each October.

At key crop growth stages—initial, vegetative, maturing, and harvesting—various crop parameters were measured. Whole plant samples were separated into different parts for analysis, following the same sampling protocol used during the growing season (emergence, anthesis, and physiological maturity), and were then oven-dried to a constant weight at 70 °C.

This study focused on three indices to evaluate cotton performance: the Yield Stability Index (YSI), Production Stability Index (PSI), and Yield Variability Index (YVI). These indices were calculated based on the following equations:

$ \mathit{YSI=(Yt-Ymean)/Ymean} $ (1) $ \mathit{PSI=(Yt-Y0)/Ymean} $ (2) $ \mathit{YVI=(Yt-Y0)/(Ymean)} $ (3) where, Yt represents the total yield in the fertilized plot (with cover crop treatment), Ymean is the mean yield across all treatments, and Y0 is the total yield in the control (no-cover crop) plot.

Climate scenarios

-

The study used the inputs of climate data derived from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model to drive the DSSATv4.7 model. Climate data, including daily precipitation, maximum and minimum temperatures, and solar radiation, were generated with WRF for both the present climate (1986–2018) and the future climate (2030, 2040, and 2050) under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. The RCP4.5 scenario is considered a medium-impact scenario, assuming the implementation of mitigation policies and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, whereas the RCP8.5 scenario is considered the worst-case scenario, in which climate change mitigation efforts are very limited[14].

Crop modeling

Model calibration and validation

-

Twelve cultivar parameters and five ecotype parameters were adjusted until the simulated crop development stages and cotton yields matched reasonably well with measured data collected in 2009 (Table 2). The data on phenology, development, and growth for the year 2010 were used for validation of the CROPGRO Cotton model. The simulated dates of various cotton development stages were compared with generally observed dates in the study area (Table 3). The simulated dates of onset of various cotton development stages, such as emergence, anthesis, and physiological maturity during calibration and validation over cotton growing seasons at Jackson, TN, USA, are within the ranges suggested by Robertson et al.[15] (Table 3).

Table 2. Parameters adjusted during the CSM-CROPGRO-Cotton model calibration.

Parameters Description Testing range Calibrated value Cultivar parameters EM-FL Time between plant emergence and flower appearance (photothermal days) 34–44 39 FL-SH Time between first flower and first pod (photothermal days) 6–12 8 FL-SD Time between first flower and first seed (photothermal days) 12–18 15 SD-PM Time between first seed and physiological maturity (photothermal days) 42–50 40 FL-LF Time between first flower and end of leaf expansion (photothermal days) 55–75 57 LFMAX Maximum leaf photosynthesis rate at 30 °C, 350 ppm CO2, and high light (mg CO2 m−2·s−1) 0.7−1.4 1.05 SLAVR Specific leaf area of cultivar under standard growth conditions (cm2·g−1) 170−175 170 SIZLF Maximum size of full leaf (three leaflets) (cm2) 250−320 300 XFRT Maximum fraction of daily growth that is partitioned to seed + shell 0.7−0.9 0.7 SFDUR Seed filling duration for pod cohort at standard growth conditions (photothermal days) 22−35 34 PODUR Time required for cultivar to reach final pod load under optimal conditions (photothermal days) 8−14 14 THRSH Threshing percentage. The maximum ratio of (seed / [seed + shell]) at maturity. 68−72 70 Ecotype parameters PL-EM Time between planting and emergence (thermal days) 3−5 4 EM-V1 Time required from emergence to first true leaf (thermal days) 3−5 4 RWDTH Relative width of the ecotype in comparison to the standard width per node 0.8−1.0 1 RHGHT Relative height of the ecotype in comparison to the standard height per node 0.8−0.95 0.9 FL-VS Time from first flower to last leaf on main stem (photothermal days) 40−75 57 Table 3. Comparisons of simulated and generally observed dates of onset of cotton phenological stages.

Crop phenological stage Observed* (days

after planting)Simulated (days

after planting)Calibration Emergence 4−9 8 Anthesis 60−70 64 Physiological maturity 130−160 156 Validation Emergence 4−9 7 Anthesis 60−70 63 Physiological maturity 130−160 145 * Robertson et al.[15]. The crop model performance was examined by comparison of observed and simulated values for the crop parameters. Hence, three deviation statistics were employed, including the coefficient of determination (R2), index of agreement (d), and root mean square error (RMSE), to evaluate the CROPGRO-Cotton model, which was calculated using Eqs (4)–(6), respectively. The R2 values ranged between 0 and 1, with 0 indicating 'no fit' and 1 indicating 'perfect fit' between the simulated and observed values. The RMSE values closer to 0 indicate better agreement between the simulated and observed values. The model calibration effort was carried out until RMSE was low, and R2 was higher than 0.80. The parameters were adjusted until the simulated crop development stages and yields matched reasonably well with the measured data (Table 3).

$ {\mathrm{R}}^{2}=\dfrac{({\sum _{\mathit{i}=1}^{\mathit{N}}(\mathit{Y}\mathit{i}-\overline{\mathit{Y}})(\hat{Y}-\overline{\mathit{Y}}\mathit{i}))}^{2}}{\sum _{\mathit{i}=1}^{\mathit{N}}{(\mathit{Y}\mathit{i}-\overline{\mathit{Y}})}^{2}\sum _{\mathit{i}=1}^{\mathit{N}}{(\hat{Yi}-\overline{\mathit{Y}}\mathit{i})}^{2}} $ (4) $ \mathrm{R}\mathrm{M}\mathrm{S}\mathrm{E}=\sqrt{\dfrac{\sum _{\mathrm{i}=1}^{\mathrm{N}}{\left(\hat{\mathrm{Y}}-\mathrm{Y}\mathrm{i}\right)}^{2}}{\mathrm{N}}} $ (5) $ \mathrm{d}=1-\left[\dfrac{{\sum _{\mathrm{i}=1}^{\mathrm{N}}(\hat{\mathrm{Y}\mathrm{i}}-\overline{\mathrm{Y}}\mathrm{i})}^{2}}{{\sum _{\mathrm{i}=1}^{\mathrm{N}}(|\hat{\mathrm{Y}\mathrm{i}}-\overline{\mathrm{Y}}\mathrm{i}|+|\mathrm{Y}\mathrm{i}-\overline{\mathrm{Y}}\mathrm{i}|)}^{2}}\right] $ (6) where, Yi equals observed value,

$ \hat{Y} $ $ \overline{Y}i $ -

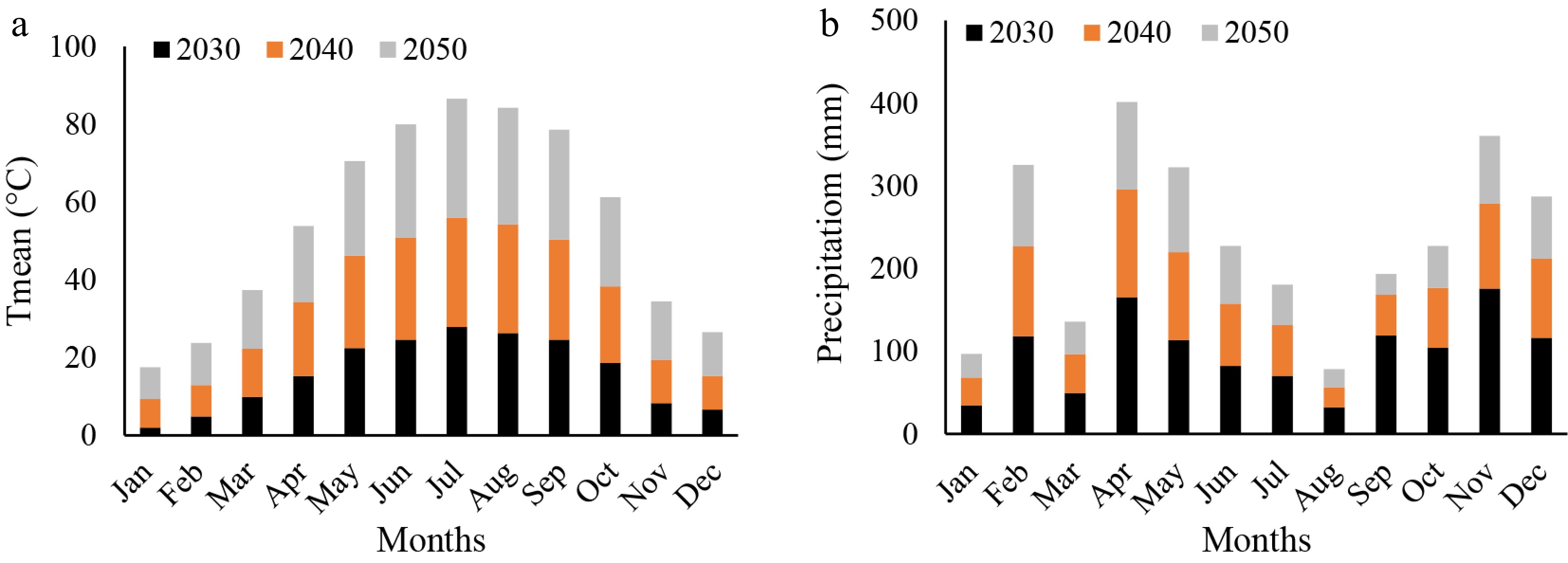

Long-term yield trends were analyzed to assess the effect of cover cropping and tillage practices on cotton productivity over 33 years (1986–2018). The data provide insight into the cumulative impact of soil management strategies under historical climate variability and evolving agronomic conditions (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Trends in cotton lint yield from 1986 to 2018 under four cover crop treatments and two tillage systems.

Overall yield trajectory and interannual variation

-

Across all treatments, cotton lint yield exhibited moderate interannual variability, with several climatic extremes (e.g., drought years) producing noticeable dips. However, treatments involving leguminous cover crops and conservation tillage consistently demonstrated greater yield stability and higher annual productivity.

Hairy vetch under no-tillage maintained the highest average yield over the study period, with annual values consistently peaking above 1,500 lb·acre−1 in favorable years (e.g., 2013, 2015, 2016). In contrast, NC under conventional tillage showed the lowest and most erratic yield pattern, with frequent dips below 500 lb·acre−1, particularly during dry years (e.g., 1991 and 1999), suggesting vulnerability to environmental stressors without protective ground cover.

Influence of cover crop type

-

The ranking of cover crop effectiveness remained consistent across the 33 years: HV consistently produced the highest yields. Crimson clover followed closely, particularly when paired with NT, achieving long-term averages near 1,300 lb·acre−1. Winter Wheat, while beneficial, produced slightly lower yields than legumes, likely due to limited nitrogen contribution. No cover was the poorest performer in both tillage systems, with average yields remaining under 1,000 lb·acre−1, and greater sensitivity to seasonal variability (Fig. 3).

Impact of tillage system

-

No-tillage systems were consistently superior in supporting higher and more stable yields compared to conventional tillage. Under NT, yield trends were more resilient during dry years and showed a gradual upward trend over time, likely due to improvements in soil structure, organic matter accumulation, and moisture conservation.

The CT systems, on the other hand, were more susceptible to yield dips during unfavorable weather years and showed greater year-to-year variability, particularly when combined with the NC treatment. The synergistic effect of legume cover crops and no-tillage was particularly evident in the late 2000s and 2010s, where yield divergence between HV–NT and NC–CT became most pronounced, highlighting the long-term benefits of conservation agriculture for cotton production in the Southeastern US.

Notably, these findings are consistent with observations reported by Raper et al.[16], who noted that continuous tillage plots experienced a decline in elevation relative to adjacent no-till treatments, suggesting potential soil degradation and loss of structure over time. This physical degradation likely contributed to the reduced yield resilience observed in CT systems, further emphasizing the value of long-term conservation practices.

Projected changes in cotton lint yield across future time horizons (2030, 2040, 2050)

-

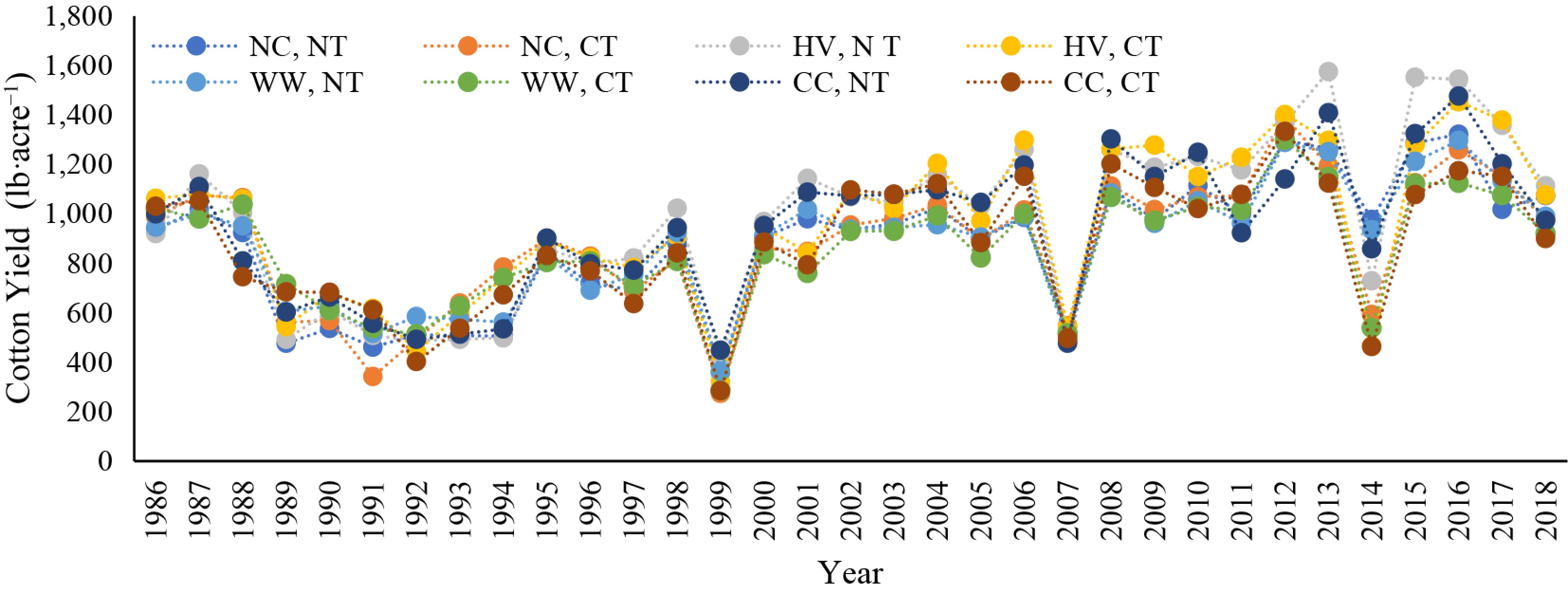

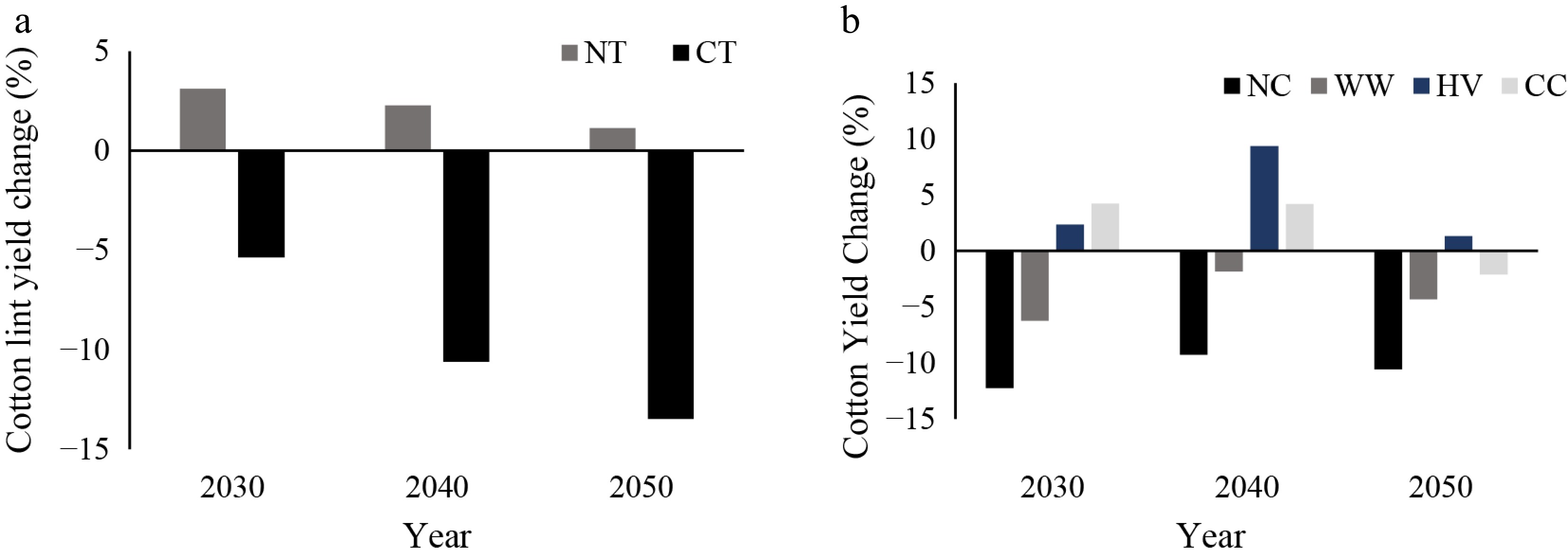

The results (Fig. 4) illustrate temporal shifts in yield dynamics and highlight the long-term effects of soil management practices on cotton productivity under climate change.

Figure 4.

(a) Simulated changes in cotton lint yield across tillage practices, and (b) cover crop treatments in 2030, 2040, and 2050 under projected climate conditions.

Tillage effects on projected yield

-

The comparison between tillage systems revealed a consistent yield advantage for NT over conventional tillage in all three future decades (Fig. 4a). In 2030, average lint yield under NT was 1,356 lb·acre−1, compared to 1,296 lb·acre−1 under CT, a yield benefit of approximately 60 lb·acre−1 (~10%). By 2040, this advantage increased, with NT maintaining 1,345 lb·acre−1, while CT declined to 1,214 lb·acre−1. The yield gap widened to over 131 lb·acre−1, suggesting increasing vulnerability of CT systems to climate stressors. Yield reductions under CT observed in this study may be partially attributed to water ponding in lower-elevation CT plots surrounded by higher NT plots. While this reflects real challenges in long-term experiments, such effects may not be as severe in commercial fields using CT.

In 2050, the trend persisted. NT yielded approximately 1,330 lb·acre−1, whereas CT fell below 1,175 lb·acre−1, marking a total reduction of ~12% from the 2030 baseline under CT compared to a smaller decline under NT (Fig. 4a). These results underscore the role of no-tillage in mitigating yield losses over time, likely due to improved soil structure, moisture retention, and reduced erosion, factors increasingly important under intensifying climate conditions.

Cover crop effects on projected yield

-

Cover crops had a significant impact on future cotton yield outcomes. Among them, leguminous species such as crimson clover (CC) and hairy vetch (HV) consistently performed better than the no-cover treatment (NC). In 2030, the highest projected yield increase was observed with CC (+4.22%), followed by HV (+2.35%), while winter wheat (WW) showed a decline (−6.21%) and NC experienced the greatest reduction (−12.23%) (Fig. 4b).

By 2040, CC maintained a strong performance (+4.18%), and HV continued to improve (+9.37%), whereas WW showed a moderate decline (−1.85%) and NC still exhibited a notable reduction (−9.25%). In 2050, CC began to decrease (−4.33%), HV also declined (−1.32%), and WW showed its first drop (−2.12%). NC consistently remained the weakest treatment, with a −10.55% decrease from baseline, indicating high vulnerability under future climate stress.

Overall, leguminous cover crops, especially HV and CC, showed greater yield stability over time. Despite fluctuations, their declines were smaller compared to non-legume and bare-soil treatments. These findings emphasize the critical role of nitrogen fixation and higher biomass input from legumes in maintaining cotton productivity under climate pressure. In contrast, NC consistently produced the lowest yields across all decades, reinforcing the detrimental effects of leaving soil bare in an increasingly variable climate.

Cotton lint yield dynamics under climate change, tillage, and cover crop systems

-

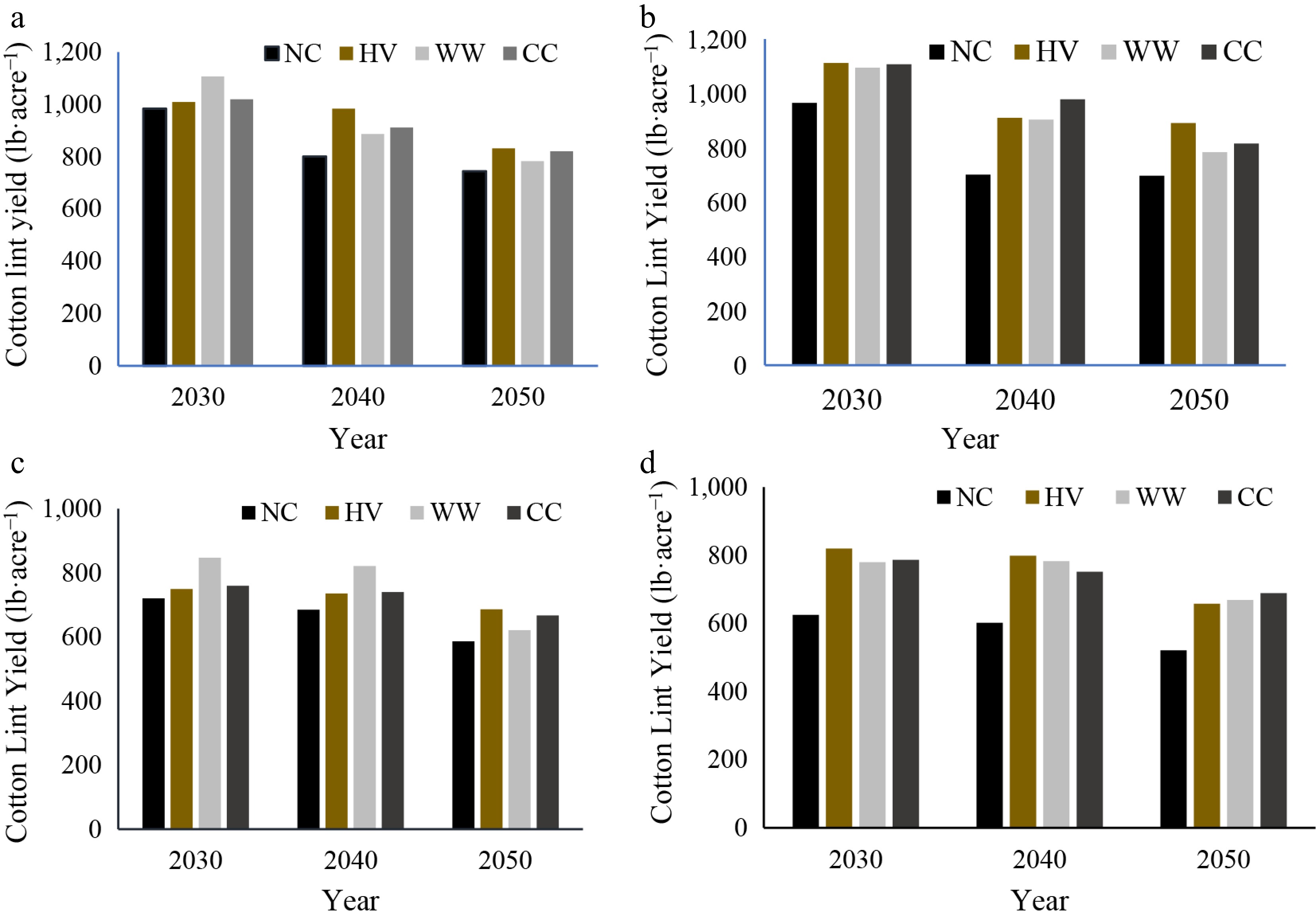

The projected changes in cotton lint yield under two RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 reveal distinct patterns driven by tillage practices and cover crop treatments. Results from the DSSAT simulations demonstrate that no-tillage systems consistently outperform conventional tillage in preserving cotton yield, particularly when integrated with leguminous cover crops. Yield responses are presented for each scenario and management combination in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Comparison of cotton lint yield under (b), (d) conventional, and (a), (c) no-tillage systems with different cover crops (CC, NC, WW, HV) under (a), (b) RCP 4.5, and (c), (d) RCP 8.5 climate scenarios.

Yield response under RCP 4.5 scenario

-

Under the RCP 4.5 pathway, yield trajectories exhibited a gradual downward trend relative to historical averages. However, the magnitude of decline was highly dependent on management practices. Across most of the cover crop treatments, NT consistently outperformed CT, suggesting that reduced soil disturbance enhances system resilience.

Among NT treatments, HV maintained the highest yield across the projection horizon, declining from 1,009 lb·acre−1 in 2030 to 832 lb·acre−1 by 2050. Crimson Clover and WW also sustained relatively strong performance, although with slightly steeper reductions. In contrast, the NC–NT system experienced more than a 24% decrease over the same period, emphasizing the vulnerability of bare-soil approaches even under conservation tillage. In CT systems, yields were consistently lower than those of the NT tillage system and more volatile. Although HV–CT and CC–CT initially showed moderate performance, both exhibited substantial declines by 2050. The NC–CT treatment demonstrated the most severe reduction, falling from 965 to 698 lb·acre−1, a cumulative decline exceeding 27%.

Yield response under the RCP 8.5 scenario

-

The RCP 8.5 scenario imposed more intense climatic stress, resulting in accelerated yield reductions across all treatments. Nonetheless, conservation systems again mitigated the severity of these losses. HV–NT remained the most resilient treatment, producing 686 lb·acre−1 by 2050, a ~30% decline from its 2030 baseline, but still outperforming all CT counterparts.

CC–NT and WW–NT showed comparable stability, while NC–NT declined sharply to 586 lb·acre−1 by mid-century. The performance gap widened further under CT,

NC–CT exhibited relatively low yields by 2050; its decline from the 2030 baseline (> 16%) was less severe compared to NC–NT (> 18%), indicating that yield reductions under conventional tillage with no cover crop were somewhat mitigated. These results highlight the compounded impact of conventional tillage and lack of cover, which together exacerbate soil degradation and reduce climate resilience.

Comparative trends and agronomic implications

-

The results reveal three overarching trends with strong implications for climate-adaptive cotton management: (1) No-tillage systems confer a consistent yield advantage under both RCP scenarios, buffering climatic stress through improved soil structure and moisture retention. (2) Leguminous cover crops (HV and CC) outperform cereal-based and bare-soil treatments, due to their dual role in nitrogen fixation and organic matter contribution. (3) Yield resilience declines with increasing climate severity, but the rate of decline is significantly slower in systems that integrate both biological and mechanical conservation strategies.

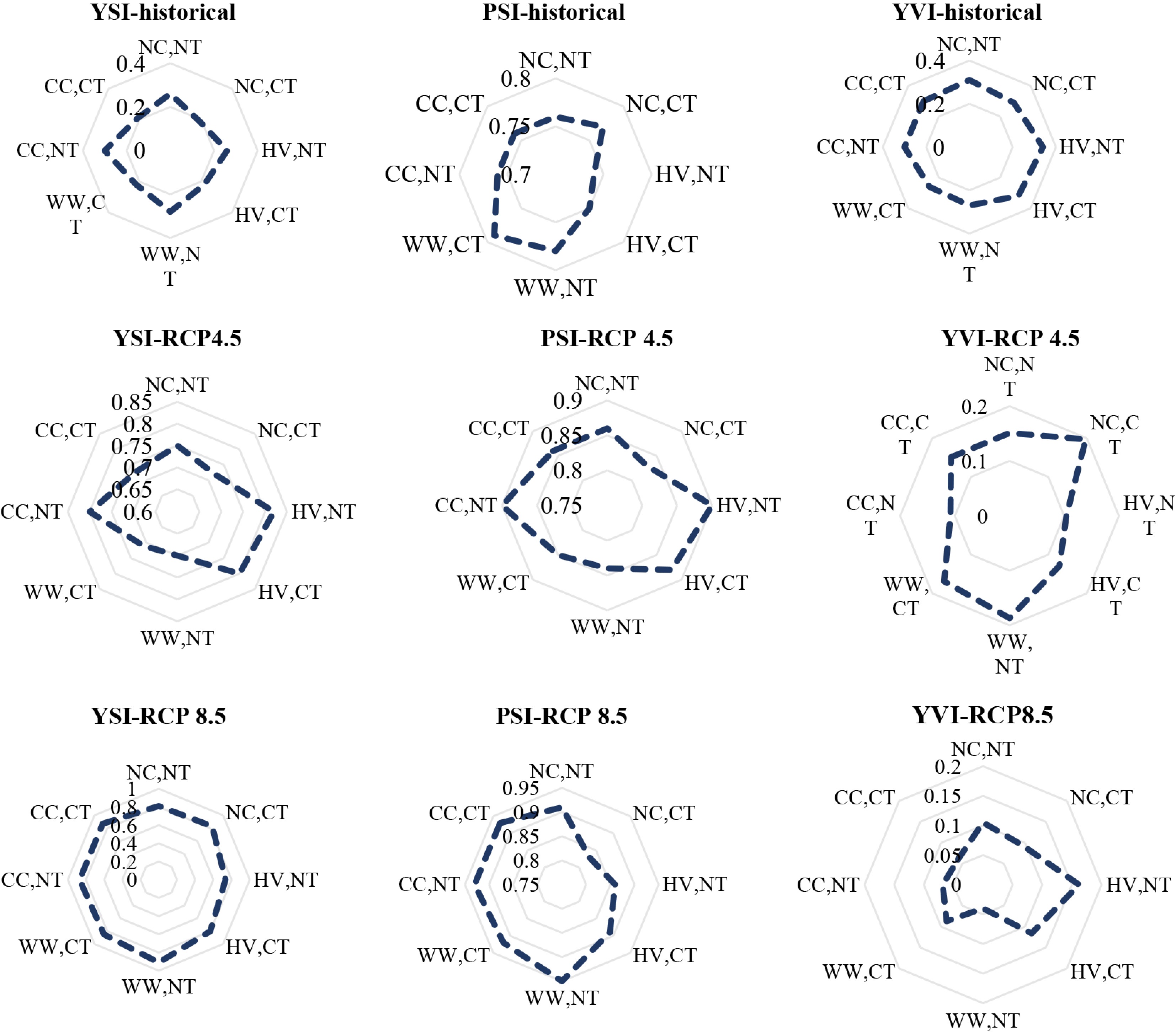

Yield stability, production stability, and variability analysis under historical and future climate scenarios

-

This presents the calculated YSI, PSI, and YVI derived from 33 years (1986–2018) of cotton yield data and projections for the years 2030, 2039, and 2050 under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5. These indices are used to assess the temporal performance and resilience of different tillage and cover crop combinations.

Historical climate (1986–2018)

-

Under historical climate conditions, all treatments exhibited low yield stability and high variability, highlighting the challenges posed by past climate fluctuations. YSI values were particularly low, ranging from 0.19 (NC–CT) to 0.30 (CC–NT), with a mean below 0.25. PSI values ranged between 0.74 (HV–NT) and 0.79 (WW–CT), indicating moderate production stability. In contrast, YVI values were consistently high across all treatments, reaching up to 0.34 (HV–NT) and remaining above 0.26, suggesting substantial year-to-year variability (Fig. 6a–c).

Figure 6.

Effect of cover crop and tillage combinations on yield stability (YSI), production stability (PSI), and yield variability (YVI) of cotton across (a)–(c) historical, and (d)–(f) future climate scenarios RCP 4.5, and (g)–(i) RCP 8.5.

These results underscore the limitations of traditional management systems under historical climate stress. Even conservation strategies such as HV–NT and CC–NT, which later performed well under future scenarios, did not significantly enhance stability under the observed climate period.

Climate scenario RCP 4.5

-

Under the moderate emission scenario (RCP 4.5), overall performance improved relative to historical conditions. YSI values increased significantly, with HV–NT and CC–NT both reaching 0.82 and 0.80, respectively, compared to only 0.26 and 0.30 historically. The highest PSI values (0.90) were observed in HV–NT and CC–NT, reinforcing their enhanced stability under moderate warming. These treatments also showed relatively low YVI values (0.104 and 0.108, respectively), indicating reduced interannual variability (Fig. 6d–f).

By contrast, treatments under conventional tillage remained less stable. For instance, NC–CT and WW–CT had YSI values of 0.72 and 0.71, and YVI values of 0.197 and 0.169, respectively, substantially higher than their no-tillage counterparts. These patterns emphasize the continuing disadvantage of conventional tillage under a changing climate, especially in the absence of vegetative cover.

Climate scenario RCP 8.5

-

Interestingly, under the high-emission scenario (RCP 8.5), overall yield stability metrics improved even further. The highest YSI and PSI were observed for WW–NT (0.91 and 0.95), CC–NT (0.87 and 0.93), and CC–CT (0.87 and 0.93). Notably, WW–NT exhibited the lowest YVI (0.04) among all treatments and scenarios, suggesting exceptional resilience in highly variable future conditions. Surprisingly, NC–CT, which historically showed poor stability, improved under RCP 8.5 (YSI = 0.83, YVI = 0.094), though it still underperformed compared to cover crop-based treatments. HV–NT, despite earlier strong performance, showed slightly lower YSI (0.733) and higher YVI (0.162) under RCP 8.5, indicating some vulnerability under more extreme climatic stress (Fig. 6g–i).

These findings suggest that while all treatments benefit from climatic conditions under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 compared to historical data, the combination of cover crops, especially winter wheat and crimson clover, with no-tillage consistently yields the most stable and resilient performance. Yield variability is significantly reduced in these systems, and stability indices are enhanced, supporting their adoption as climate-smart strategies for cotton production in the Southeastern US.

-

The analysis of long-term cotton lint yield trends under historical conditions underscores the pivotal role of soil management practices, particularly the integration of cover crops and conservation tillage, in promoting yield stability and system resilience. The superior performance of hairy vetch and no-tillage combinations across multiple decades demonstrates that conservation agriculture is a viable response to future climate risks and an effective strategy that has historically enhanced productivity.

The above findings are consistent with prior research showing that cover crops, especially legumes, contribute to improved soil quality through enhanced organic matter, nutrient cycling, and microbial activity[17]. Hairy vetch has been shown to boost soil nitrogen availability while improving soil aggregation and water retention[18], which may explain its strong yield performance across dry and favorable years. The sustained performance of these systems even during drought-prone years supports their role as buffers against climatic stress, as previously reported by Yuvaraj et al.[19], who found that cover crops increased resilience to extreme weather by improving soil structure and infiltration capacity.

On the other hand, the underperformance of no-cover treatments, particularly under conventional tillage, reflects both biological and structural limitations of such systems. With conventional tillage and a lack of vegetative cover, increased soil disturbance leads to greater erosion, compaction, and moisture loss, resulting in unstable crop performance[20,21]. The observed yield volatility under NC–CT is a manifestation of these cumulative degradative processes.

Moreover, the widening performance gap observed in later decades between HV–NT and NC–CT treatments suggests that the benefits of conservation practices accumulate over time, a phenomenon supported by long-term studies in temperate and subtropical systems[22,23]. As soil organic carbon accumulates and microbial communities stabilize, the conservation systems develop an improved buffering capacity against both biotic and abiotic stressors[24].

Ultimately, these historical patterns reinforce the idea that conservation agriculture should not be viewed solely as a climate adaptation strategy for the future but rather as a scientifically validated pathway that has already proven effective under decades of variable weather conditions. By recognizing the value of long-term soil health, producers and policymakers can make more informed decisions that align immediate productivity goals with long-term sustainability.

Yield projections by decade (2030, 2040, 2050)

-

No-tillage systems, compared to CT, consistently provide a sustainable yield advantage across all future decades, which aligns with previous research on soil structure preservation and increased moisture retention capacity[25]. It is important to acknowledge that the historically lower performance of CT treatments may have been partially exacerbated by unintended trial design artifacts. Specifically, the repeated soil disturbance under CT led to the gradual subsidence of these plots over time, creating lower elevation zones prone to water pooling. This resulted in excess moisture stress in wet years, often requiring replanting and potentially reducing yields beyond what would be expected from tillage effects alone. Importantly, producers practicing CT in real-world settings typically implement drainage or field leveling strategies that mitigate such issues. As such, while the trends observed in this study are scientifically robust, some of the yield reductions under CT may not fully represent typical field conditions, and caution should be exercised in generalizing these specific results to all conventional systems under increasing climatic stress. Reducing soil disturbance and preserving organic matter through no-tillage can enhance soil resilience against drought and erosion[26].

Moreover, cover crops—especially leguminous species such as Hairy Vetch and Crimson Clover—were identified as effective biological strategies for improving the stability of cotton yield. These cover crops increase soil fertility and improve soil moisture conditions by fixing atmospheric nitrogen and adding organic matter[27]. Similar studies have shown that the use of leguminous cover crops reduces evaporation and improves soil water storage, thereby sustaining crop performance in dry and warm climates[28].

The relative decline in cover crop performance observed in the 2050s likely reflects the cumulative impacts of more severe climate change and the limitations of these systems for long-term adaptation. These findings suggest that sustainable agricultural management should be based on integrating multiple strategies and dynamically adapting to local climatic conditions[29].

Climate scenario-based yield projections (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5)

-

The projected changes in cotton lint yield under future climate scenarios highlight the critical role of soil management practices, particularly tillage systems and cover crop integration, in mitigating yield losses and sustaining productivity. These findings, derived from DSSAT model simulations, demonstrate that NT systems consistently outperform CT across both moderate (RCP 4.5) and severe (RCP 8.5) climate pathways. This yield advantage aligns with extensive literature recognizing the benefits of reduced soil disturbance in preserving soil structure, enhancing moisture retention, and maintaining organic matter content, which are pivotal for crop resilience under climatic stress[30].

The superiority of NT systems in buffering yield declines is particularly evident when combined with leguminous cover crops, such as HV and CC. These legumes enhance soil nitrogen availability through biological fixation, which not only supports crop nutrition but also improves soil microbial activity and organic matter inputs[31]. These results corroborate findings by Dabney et al.[32] who reported that legume-based cover crops contribute to improved soil water conservation and reduce evapotranspiration, thereby supporting yield stability in water-limited environments.

In contrast, bare soil management, especially under CT, exhibited the most pronounced yield reductions, emphasizing the vulnerability of systems lacking biological cover and subjected to intensive tillage[33,34]. The stark difference in yield trajectories between NT-legume systems and CT-bare soil treatments underscores the importance of integrated soil health strategies to counteract the adverse effects of climate change.

The sharper yield declines under the RCP 8.5 scenario reflect the projected intensification of climatic stressors, including increased temperatures, variable precipitation, and extreme weather events[32]. However, the relative resilience of conservation practices suggests these strategies can significantly mitigate climate risks. This aligns with Shamshiri et al.[35], who emphasize adaptive management frameworks incorporating both mechanical and biological practices to sustain agricultural productivity under climate variability.

Furthermore, the gradual yield decreases observed even in NT-legume systems by mid-century may indicate the limits of current conservation strategies under escalating climate pressures, suggesting a need for continued innovation and adaptation. Integrating precision agriculture technologies, drought-tolerant cultivars, and diversified cropping systems could enhance the long-term sustainability and climate resilience of cotton production[36].

Yield stability and variability indices (YSI, PSI, YVI)

-

These findings underscore the pronounced challenges posed by climate variability in the historical period (1986–2018), where all treatments exhibited low YSI and relatively high YVI, reflecting the vulnerability of conventional management practices to climatic fluctuations. These results align with earlier studies, which indicate that traditional tillage and bare soil systems are often insufficient to buffer yield variability in the face of climate stress[37,38].

Under moderate future warming scenarios (RCP 4.5), significant improvements in yield stability were observed, particularly in no-tillage systems combined with leguminous cover crops such as Hairy Vetch (HV) and Crimson Clover (CC). The increase in YSI and PSI, alongside reduced YVI, illustrates the capacity of these integrated conservation practices to enhance system resilience by stabilizing yields and reducing interannual fluctuations. This outcome corroborates findings from Chen et al.[33], who documented that conservation tillage coupled with cover cropping improves soil physical properties and moisture retention, thereby mitigating the negative impacts of climate variability on crop performance.

Interestingly, under the more extreme RCP 8.5 scenario, further gains in yield stability were detected, especially in systems involving WW and crimson clover in no-tillage contexts. The exceptionally low YVI values observed for WW–NT indicated superior resilience to increased climatic variability anticipated under high-emission futures. This suggests that diversified cover crop mixtures may provide functional redundancy and buffering capacity against abiotic stressors, a notion supported by Dardonville et al.[39] and Moore et al. (2020), who emphasized biodiversity and system complexity as key factors in agroecosystem stability. The relative improvement in stability metrics for traditionally less stable treatments such as NC–CT under RCP 8.5 might reflect nonlinear responses of crop systems to climatic stressors or model simulation artifacts; however, these treatments still lag behind cover crop-based systems, underscoring the crucial role of vegetative cover in soil and yield stabilization[40].

The somewhat diminished performance of HV–NT under the RCP 8.5 scenario highlights the potential limits of single-species cover crop strategies in adapting to intensifying climate extremes, advocating for diversified crop rotations and integrated soil health management[39,40].

-

This study highlights the significant role of conservation agricultural practices, particularly no-tillage combined with leguminous cover crops, in enhancing cotton yield stability, reducing interannual variability, and mitigating the adverse effects of climate change. Long-term field data (1986–2018) and future yield projections under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios consistently demonstrate that no-tillage incorporating hairy vetch and crimson clover outperforms conventional tillage with no cover in both yield performance and resilience. As climate pressures intensify, the integration of biological (cover crops) and mechanical (reduced tillage) soil conservation strategies will be essential for sustaining cotton production in the Southeastern US. These findings support the broader adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices to ensure long-term productivity and system stability.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: data analysis and draft manuscript preparation: Foumani MP; study supervision, manuscript guidance and revision: Yin X; manuscript review and improvement: Fu JS, Yang CE, Adotey R, Raper T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The University of Tennessee One Health Initiative funded this study. We thank Dr. Donald D. Tyler and the others who established and managed the long-term field experiment.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Mohil PF, Yin X, Fu JS, Yang CE, Adotey R, et al. 2026. Integrating crop modeling and climate projections to evaluate cotton yield response to tillage and cover crops in the Southeastern US. Technology in Agronomy 6: e003 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0016

Integrating crop modeling and climate projections to evaluate cotton yield response to tillage and cover crops in the Southeastern US

- Received: 30 June 2025

- Revised: 27 September 2025

- Accepted: 30 September 2025

- Published online: 02 February 2026

Abstract: Climate change poses a significant threat to cotton production in the Southeastern United States, necessitating adaptive management strategies that enhance yield stability and system resilience. This study integrates 33 years of field data (1986–2018) with simulations from the DSSAT v4.7 model, driven by downscaled climate data from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model under Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5) scenarios, to assess the effects of two tillage systems (conventional and no-tillage) and four cover crop treatments (hairy vetch (HV), crimson clover (CC), winter wheat (WW), and no cover (NC)) on cotton lint yield. Yield stability was evaluated using three metrics: Yield Stability Index (YSI), Production Stability Index (PSI), and Yield Variability Index (YVI). The combination of HV and no-tillage resulted in the highest performance, with historical average lint yields exceeding 1,460 lb·acre−1, a YSI of 0.97, and the lowest yield variability (YVI = 0.11). In contrast, the NC under conventional tillage treatment showed the lowest yield (~900 lb·acre−1), lowest YSI (0.68), and highest variability (YVI = 0.32). Under future projections, lint yields declined across all treatments but at different rates. By 2050, under RCP 8.5, HV–NT maintained relatively stable yields (~1,350 lb·acre−1), whereas NC–CT dropped below 1,000 lb·acre−1, reflecting a decline of over 30% from baseline. Notably, conservation systems such as HV–NT and CC–NT showed up to 200–250 lb·acre−1 higher yields than conventional treatments under the same climate conditions. These findings underscore the importance of conservation agriculture as a viable climate adaptation strategy. Integrating biological (cover crops) and mechanical (reduced tillage) soil management practices can sustain cotton productivity while improving system resilience in the face of increasing climate uncertainty.

-

Key words:

- Climate change /

- Cotton /

- Cover crops /

- Conservation agriculture /

- DSSAT /

- No-tillage /

- RCP scenarios /

- Yield stability