-

Passiflora plants are lianas with axillar tendrils and nectaries; their sexual organs are merged into a structure named the androginophore[1]. Passiflora is a genus with nearly 600 species; 95% of them are American natives, mainly from South America and Mesoamerica (from Central Mexico to Panama)[2]. More than 60 species of Passiflora produce large edible fruits, and nearly 25 species are cultivated. The economically important edible juice producers are Passiflora edulis, P. edulis f. flavicarpa, P. ligularis, P. quadrangularis, and P. tripartita var. mollissima; moreover, the fruits of P. tripartita, P. tarminiana, P. maliformis, P. alata, P. hannii, P. laurifolia, P. popenovii, and P. setacea are consumed locally elsewhere[3]. Approximately 1.5 million tons of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) are produced worldwide, with Brazil being the main producer and consumer[4].

Although most Passiflora species are American native, research on those species involved worldwide scientific groups. For example, due to their, actual and potential ecological and economic roles, in several world regions, such as China, projects for cropping and breeding Passiflora are being developed[5]. Medical researchers are determining the potential of Passiflora plant organs to recover physical and psychiatric human health[6,7].

In Mexico, 91 Passiflora species, native and introduced, have been reported, indicating that, for this genus, this country is the fifth in worldwide diversity ranking[8]. Within Mexico, one of the areas with greater Passiflora diversity are the areas belonging to the southern states of Campeche, Chiapas, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo[9]. In Chiapas state there are, at least, two endemic species, P. pendens and P. tacanensis[8].

The land area of those southern states is 215,047 km2, representing approximately 10% of the total Mexican territory. Nowadays, its current inhabitants belong to different ethnic groups and mestizo people[10]. Nevertheless, before Spanish irruption in Mexico, this area was inhabited by several groups belonging to ancient Mayan culture, including yucatecos in the states of the Yucatan Peninsula (Campeche, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo), and choles, tsetales, tsotsiles, tojolabanes, and lacandones in Chiapas state[11,12].

As Mexico is one of the main land reserves for Passiflora plants, scientific efforts to claim further national studies on this plant genus must be performed. This review presents a list of the Passiflora species botanically recorded in four southern Mexican states. Then reports related to previous, actual, and potential uses for those species are briefly summarized. This review aims to point out the importance of the conservation of Passiflora genetic resources in southern Mexico.

-

According to the herbaria MEXU[13], HERBANMEX[14], CICY[15], and CHAPA[16], thereafter confirmed in the specialized platform 'Plants of the word on line'[8], in the states under study, there are 55 Passiflora species (Table 1). Chiapas state accounts for 90% of those species, followed by Quintana Roo, Campeche, and Yucatán states[9].

Table 1. Passiflora species botanically registered in the states of Chiapas, Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Yucatán, Mexico; and their names in Spanish (S), Yucatec Maya (Y), Lacandón Maya (L), Tseltal Maya (T), and English (E).

No. Species Location Name 1 P. adenopoda DC. Chiapas (L): k'um sek; ucumin sek 2 P. alata Curtis Chiapas (E): winged-stem passion flower 3 P. ambigua Hemsl. Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): granadilla de monte; ingo; jugito; jugo; (L): ch'um ak' 4 P. apetala Killip Chiapas No information 5 P. bicornis Mill. Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): ojo de luna; (Y): poch k' aak' ; kasu' uk; (E): wing-leaf passionfruit 6 P. biflora Lam. Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): calzón de niño; bejuco de guaco; hoja de murcielago; (Y): poch aak'; (L): k'um sek (ah); (T): mayil poch;

(E): twoflower passion-flower7 P. bryonioides Kunth Chiapas (S): granada cimarrona; (E): cupped passion flower 8 P. capsularis L. Quintana Roo No information 9 P. ciliata Aiton Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): maracuyá; sipolan; (Y): poch k' aak' ; poch kaki; xpoch aki; (E): fringed passion flower 10 P. clypeophylla Mast. ex Don.Sm. Chiapas No information 11 P. cobanensis Killip Campeche, Chiapas & Quintana Roo No information 12 P. conzattiana Killip Campeche, Chiapas & Quintana Roo (S): hoja de vampiro 13 P. dolichocarpa Killip Chiapas No information 14 P. edulis Sims Campeche, Chiapas & Yucatán (S): maracuyá; flor de pasión; maracuyá morado;

(Y): xton kee jil; (E): yellow passion fruit, purple passion fruit15 P. exsudans Zucc. Campeche (S): bolsa de gato; té de insomnio 16 P. filipes Benth Chiapas (S): frijolillo; granadilla

(E): slender passion flower

17 P. foetida L. Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): amapola; maracuyá silvestre; granadillo; cinco llagas

(Y): poch; túubok; poch' aak' ; poch' iil

(E): stinking passion fruit; fetid passion flower; rambusa

18 P. hahnii (E.Fourn.) Mast. Chiapas (S): granadilla chos 19 P. helleri Peyr. Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán No information 20 P. holosericea L. Chiapas No information 21 P. itzensis (J.M.MacDougal) Port.-Ult. Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (Y): maak xikin soots' 22 P. jorullensis Kunth Chiapas (S): golondrina; tijerilla 23 P. lancearia Mast. Chiapas No information 24 P. ligularis Juss. Chiapas (S): granadilla; granada de moco; (E): sweet granadilla 25 P. mayarum J.M.MacDougal Campeche, Chiapas & Quintana Roo (S): granadillo; (Y): toon ts' iimim; poch aak'; (E): wild passion flower 26 P. membranacea Benth. Chiapas (S): granadilla; granada; (T): karanotozak; karanato rak' 27 P. mexicana Juss. Chiapas No information 28 P. morifolia Mast. Chiapas (E): woodland passion flower 29 P. obovata Killip Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán No information 30 P. oerstedii Mast. Chiapas (S): granadilla chos 31 P. ornithoura Mast. Campeche, Chiapas & Quintana Roo No information 32 P. pallida L. Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (Y): sak aak' ; soots' aak' ; ts' unyajil 33 P. pavonis Mast. Chiapas No information 34 P. pedata L. Campeche, Quintana Roo & Yucatàn (Y): toom ts' iimin; tontotzimin 35 P. pendens J.M.MacDougal Chiapas No information 36 P. pilosa Ruiz & Pav. ex DC. Chiapas (S): granadilla; granada de zorro 37 P. platyloba Killip Chiapas & Quintana Roo (S): granadilla de monte 38 P. porphyretica Mast. Chiapas (T): schelchikin chinzak 39 P. prolata Mast. Campeche, Chiapas & Quintana Roo (S): granadilla de monte 40 P. quetzal J.M.MacDougal Chiapas No information 41 P. rovirosae Killip Campeche, Chiapas & Quintana Roo No information 42 P. sanctae-mariae J.M.MacDougal Chiapas No information 43 P. seemannii Griseb Chiapas No information 44 P. serratifolia L. Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): amapola; jujito amarillo; maracuyá de monte; pasionaria; granada de ratón; (Y): pooch aak' ; ya' ax pooch; (L): poochin; (E): broken ridge granadillo 45 P. sexflora Juss. Chiapas & Campeche (S): granadilla chos;

(T): schelchikinchinak; shel chikin chinzak; shel chikin46 P. sexocellata Schltdl. Campeche, Chiapas & Yucatàn (S) ala de murciélago; granada de ratón;

(Y): xikin sots' ; xiik' sots'47 P. sicyoides Schltdl. & Cham. Chiapas (S) granadilla 48 P. standleyi Killip Chiapas No information 49 P. suberosa L. Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): granadilla roja; granadita de ratón; pata de pollo;

(Y): kansel-ak; zal-kansel-ak; (I): cork-barked passion-flower, corky passion fruit50 P. sublanceolata (Killip) J.M.MacDougal Campeche, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S) jujo; (Y): pooch k' aak' 51 P. subpeltata Ortega Campeche & Chiapas (S) pasionaria, granadina, aretitos, granada de zorra, jujo 52 P. tacanensis Port.-Utl. Chiapas No information 53 P. tarminiana Coppens & V.E.Barney Chiapas No information 54 P. xiikzodz J.M.MacDougal Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (Y): maak xikin soots' 55 P. yucatanensis Killip ex Standl. Campeche, Quintana Roo & Yucatán (S): flor de la pasión de Yucatán; (E): Yucatan passion flower References[5,6,8,9,13−18]. Chiapas state presents five biogeographical provinces related to a specific natural area in relation to its endemic biota. Those five provinces are, the 'Gulf of Mexico lowland', 'Chiapas central plateau', 'Chiapas central depression', 'Madre mountain range', and 'coastal lowland'. In contrast, within the Campeche state area, there are two biographical provinces, the 'Gulf of Mexico lowland' and the 'Yucatán lowland'. Whereas Yucatán and Quintana Roo states belong only to the province named 'Yucatán lowland'[19]. Thus, the presence of different biogeographical provinces, implying different climates and ecological conditions, might influence Passiflora diversity. For example, in Mexico, Chiapas state is known to be the second state with a relatively high total plant diversity, with over 10,000 plant species[20].

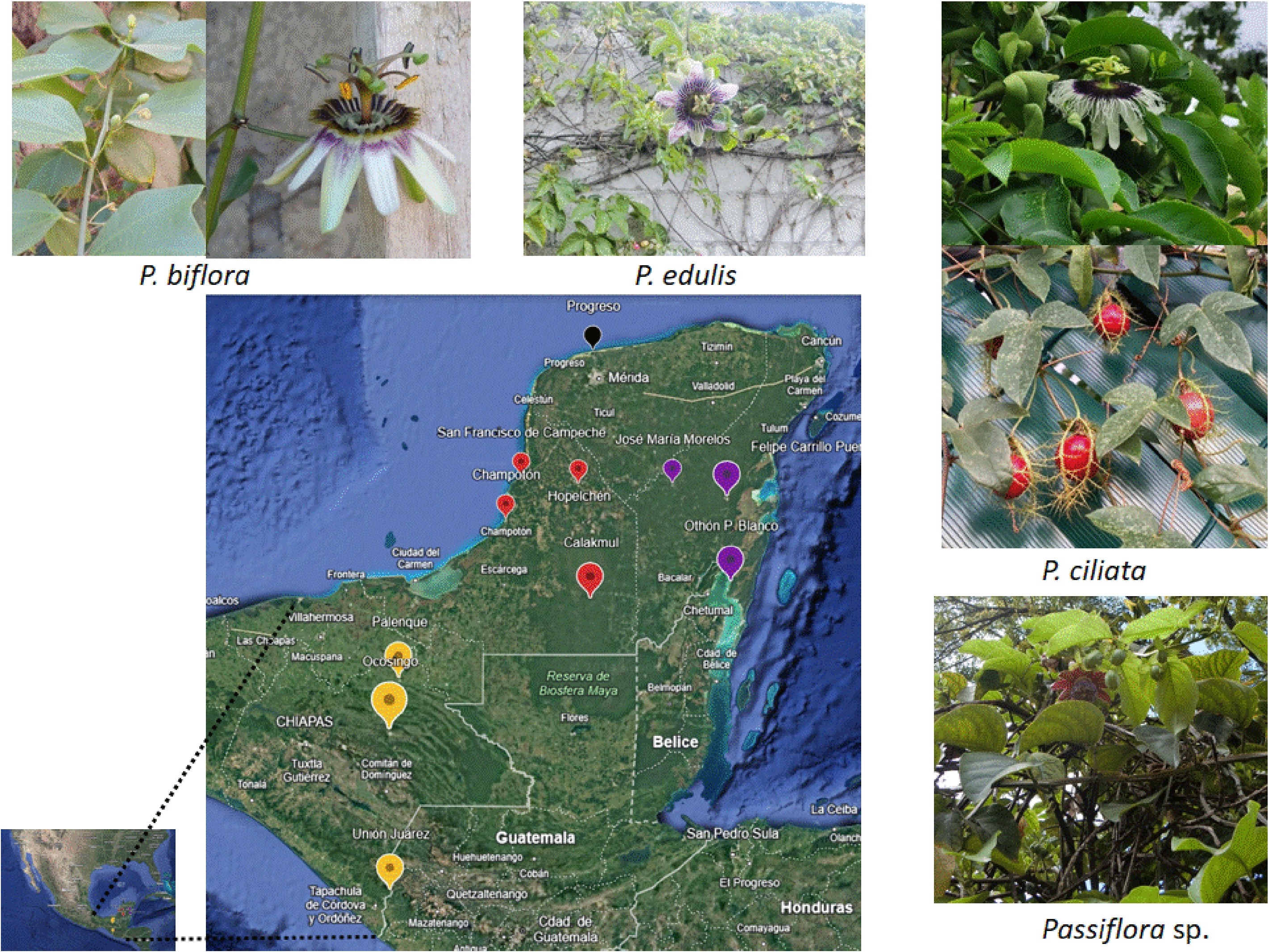

For Chiapas state, there are botanical reports of Passiflora in 65 of the 126 municipalities, with a greater presence in Ocosingo (19 species), Unión Juárez (nine species), and Palenque (eight species). Including the four states under study, the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, Quintana Roo state (11 species), follows Ococingo, and then, the list continues with Calakmul, Campeche State (11 species). For Yucatán state, a greater Passiflora presence has been reported in Progreso (five species) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Municipalities within Peninsula de Yucatán and Chiapas, Mexico, with greater botanical reports of Passiflora species. Chiapas (yellow) [Ococingo (19), Unión Juárez (9), and Palenque (8)], Campeche (red) [Calakmul (11), Holpechén (6), Campeche (5), and Champotón (5)], Yucatán (black) [Progreso (5)], and Quintana Roo (purple) [Othón P. Blanco (11), Felipe Carrillo Puerto (8), and José María Morelos (5)]. Four Passiflora species illustrate this genus diversity. Data of present work were marked on a map sourced from Google Earth.

The number of Passiflora species recorded in Ocosingo is greater than the number of Passiflora species reported in each of the other 18 states in Mexico[9]. Additionally, Unión Juárez must be valorized for its Passiflora richness, as the municipality area is only 62 km2[10].

Passiflora species grow mainly in family orchards and jungle systems[12,21]; the latter system is very sensitive to overexploitation of natural resources, pollution, and climatic change. Moreover, it is very responsive to demographic changes, public policies, and local technological projects[22].

-

To our knowledge, there are no reports of the use of Passiflora plants by ancient Mayan culture. However, ethnobotanical reports, written in the last three decades, indicate that in the Lacandón forest, native people eat the fruits of 'ch'um ak'' (P. ambigua), 'ch'ink ak'il' (Passiflora sp.) 'poochin' (P. serratifolia) and P. hahnii[12,13]. A recent review confirmed the consumption of P. ambigua, P. bicornis, P. ciliata, P. foetida, P. hahnii, P. ligularis, P. mayarum, P. serratifolia, and P. yucatensis fruits in communities of Chiapas and the Yucatan Peninsula[23].

In Yucatán state, the P. ciliata plant is used to treat hysteria, sleeplessness, and child convulsion; local people assign this species narcotic and sedative properties[24]. In the Chiapas High Valleys, P. membranacea liana is used as a rope to tie tools or help build rudimentary houses[21].

In the municipality of Solidaridad, Quintana Roo State, the staff of the butterfly pavilion of a theme park, crop at least two Passiflora species, one allegedly to be P. lobata ('pata de gallo' in Spanish), to raise butterfly larvae. The information within the park, mentions that they raise the butterflies Agraulis vanillae, Dryas iulias, Heliconius erato, and H. charithonia. Scientific literature supports the preference of butterfly larvae for P. lobata[25].

-

For centuries, some effects on the human body have been assigned to Passiflora plants. Moreover, in the Spanish language, the name of passion fruit was misunderstood, and many people have given aphrodisiac properties to Passiflora species, instead of relating its name to the passion of Christ[1]. Moreover, in plants of this genus, several molecules with spasmolytic, sedative, anxiolytic, and blood pressure modulation properties have been identified. One of those molecules is passicol, which has antibacterial properties. P. foetida leaf extracts reduce the growth of Pseudomonas putida, Vidrio cholerae, Shigella flexneri, and Streptococcus pyogenes, supporting the use of this plant in ethnopharmacology to treat fiber, diarrhea, stomach and throat pains, and ear and skin infections[26].

It has been suggested that the anthocyanin present in the peel of P. biflora might be used as an additive to increase color and antioxidant capacity in some human foods[27]. Additionally, pectin can be extracted from the Passiflora peel for human consumption[28], and it has been proposed to transform peel into biofuels[29]. As Brazil is a high yellow passion fruit producer, it has been proposed to produce passion fruit seed oil there. The oil might be used in human foods or transformed into creams, shampoos, and pharmacology products[30]. In addition, among the seed components, there are stilbenes, which are excellent antioxidants, enhance human skin conditions, and present hypoglycemic properties[31].

-

In the Yucatan Peninsula, Passiflora is among the top five plant genera with relatively high diversity[17]. This richness might be used to breed, aiming for genotypes producing high-quality fruits and suitable for cropping in new areas[5,32]. Nevertheless, land use change represents one of the greatest risks to conserving actual biodiversity; this factor also contributes to increasing the rate of climatic change and affects ecosystem sustainability[33].

Quintana Roo state is one of the main tourist region's in Mexico, Cancun resort area is located there, and further luxury resorts are still planned. Mexican environmental law protects approximately 30% of the land of the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, Quintana Roo state[34]; and this municipality started policy programs for sustainable bay management, keeping its vegetation, including several medicinal plants[35]. In this sense, recently, the Mexican government involved some institutes in flora conservation. In the municipality of Solidaridad, Quintana Roo state, the Botanical Garden 'Dr. Alfredo Barrera Marín' belonging to the 'Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo' is the repository of the flora native of the section North 5 of the project Maya Railway.

In general, in the four states under study herein, there are important archeological and touristic venues; thus, Passiflora conservation in southern Mexico might involve ethno-tourism, ecotourism, and other local developmental projects. Moreover, in the Yucatan Peninsula and Chiapas there are almost 17 areas named Nature Reserves. They are: 'Pantanos de Centla', 'Río Celestum', 'Río Lagartos', 'Sian Ka'an' 'Chinchorro', 'Caribe Mexicano', 'Tiburón ballena', 'El triunfo', 'La Encrucijada', 'La Sepultura', 'Lacan tún', 'Montes azules', 'Selva El Ocote', 'Volcán Tacaná', 'Calakmul', 'Balam ku', and 'Los Peténes'. Therefore, according to UNESCO, in nature reserves, effective fauna and flora protection policies might be observed[36].

The role of Passiflora plant species in conserving local fauna, and, by a consequence, help to keep the ecosystem balance, must be carefully understood. Several Passiflora species included in Table 1 have been reported to be good feed sources for animals. For example, P. biflora may play a role in conserving bats in the Lacandón forest[9]. For Passiflora species being bat-pollinated, it has been observed that their flowers are well adapted to bat behavior, as their flowers secrete nectar at night[37]. Moreover, it has been reported that some years after introducing Passiflora plants, the population of butterflies and bees was increased[9]. Some studies have revealed that P. suberosa is a good feed source for A. vanillae maculosa larvae, although less preferred by D. iulia caterpillar, who prefers leaves of P. misera[38,39].

Although tropical forest regeneration is possible, the predicted growth of urban areas is a risk factor[33] in reducing Passiflora diversity. On the other hand, some researchers have suggested that rural families contribute strongly to maintaining plant species[40]. Thus, reducing the poverty factor might be included in national, state, and municipality politics to recognize the importance of native and original communities in conserving plant genetic resources. For example, within the three municipalities with the greatest presence of Passiflora species, only Othón P. Blanco has less than 45% of its population living in poverty, whereas over 80% of the populations of Ocosingo and Calakmul live in poverty. In five of the six municipalities with a greater presence of Passiflora, the human population living in poverty is greater than 70%[41].

Although some countries offer payments to conserve plant genetic resources, they are limited to plant species presenting economic importance[42]. Thus, to involve local people in plant genetic conservation, projects aimed at sustainability, environment conservation, prosperity, and human welfare must be offered. The municipality, state, and national governments must establish laws and regulations to save jungles and mangroves. Further efforts to keep flora and fauna, in this case Passiflora species, in the areas with a higher presence of this genus, are expected to keep its holistic value and diversity.

-

The high diversity of Passiflora plants in Chiapas state seems to be related to the presence of five biographical provinces: 'Gulf of Mexico lowland', 'Chiapas central plateau', 'Chiapas central depression', 'Madre mountain range', and 'coastal lowland'. Within Chiapas state, Ococingo is the municipality with the highest Passiflora diversity.

Although there are no reports of the use of Passiflora in ancient Maya culture living in Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatán, or Quintana Roo states, the actual use of Passiflora suggests inherited knowledge. On the other hand, the agro-industrial and pharmacological potential of this plant genus might help promote sustainable regional development. The rescue of traditional fruit species and their ancient knowledge might enhance the local economy and maintain ecological balance.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Franco-Mora O; data collection: Franco-Mora O, Moreno-Jiménez A; analysis and interpretation of results: Franco-Mora O, Sánchez-Pale JR; draft manuscript preparation: Franco-Mora O, Castañeda-Vildózola Á. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The herbaria exemplars, consulted herein, represent the work of several botanists. The picture of Passiflora ciliata was kindly donated by Prof. Elia Ballesteros-Rodríguez (CICY, Yucatán, Mexico).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Franco-Mora O, Sánchez-Pale JR, Castañeda-Vildózola Á, Moreno-Jiménez JA. 2025. Regional importance and potential of Passiflora: the case of the Yucatan Peninsula and Chiapas, Mexico. Technology in Horticulture 5: e008 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0004

Regional importance and potential of Passiflora: the case of the Yucatan Peninsula and Chiapas, Mexico

- Received: 25 October 2024

- Revised: 21 January 2025

- Accepted: 24 January 2025

- Published online: 04 March 2025

Abstract: According to Mexican herbaria, scientific databases, and literature, 91 Passiflora species are registered in Mexico; thus, worldwide, this country presents the fifth largest diversity for this genus. Among Passiflora species, the most important economic species include yellow and red passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). In southern Mexico, in Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, and Yucatán states, 50% of the countries Passiflora diversity are recorded. Fifty-five Passiflora species have been recorded, 50 in Chiapas, 23 in Quintana Roo, 22 in Campeche, and 17 in Yucatán. At the municipality level, Ocosingo, Chiapas, presented the highest number of Passiflora species of 21; followed by Othón P. Blanco, Quintana Roo, with 14; and Calakmul, Campeche, with 11. In its territory, Chiapas presents five biogeographical regions, explaining, at least in part, its richness in Passiflora species. The fruits of several species of this genus have been used in local communities as food, mainly beverages, and traditional medicine.

-

Key words:

- Biogeographical province /

- Liana /

- Juice /

- Mayan Passiflora names /

- Passion fruit