-

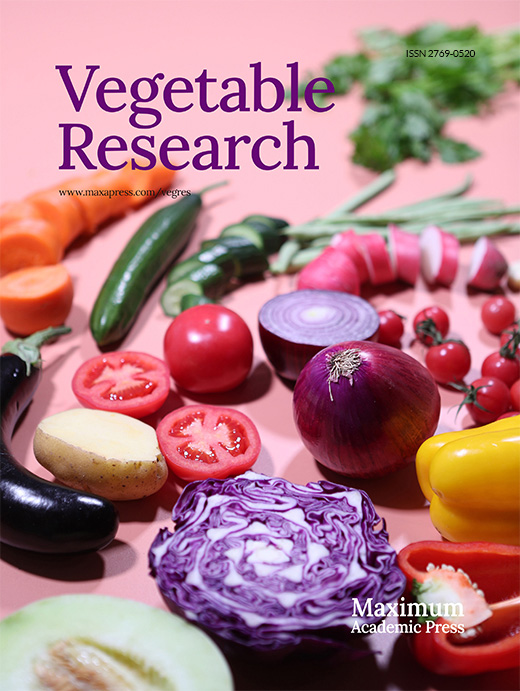

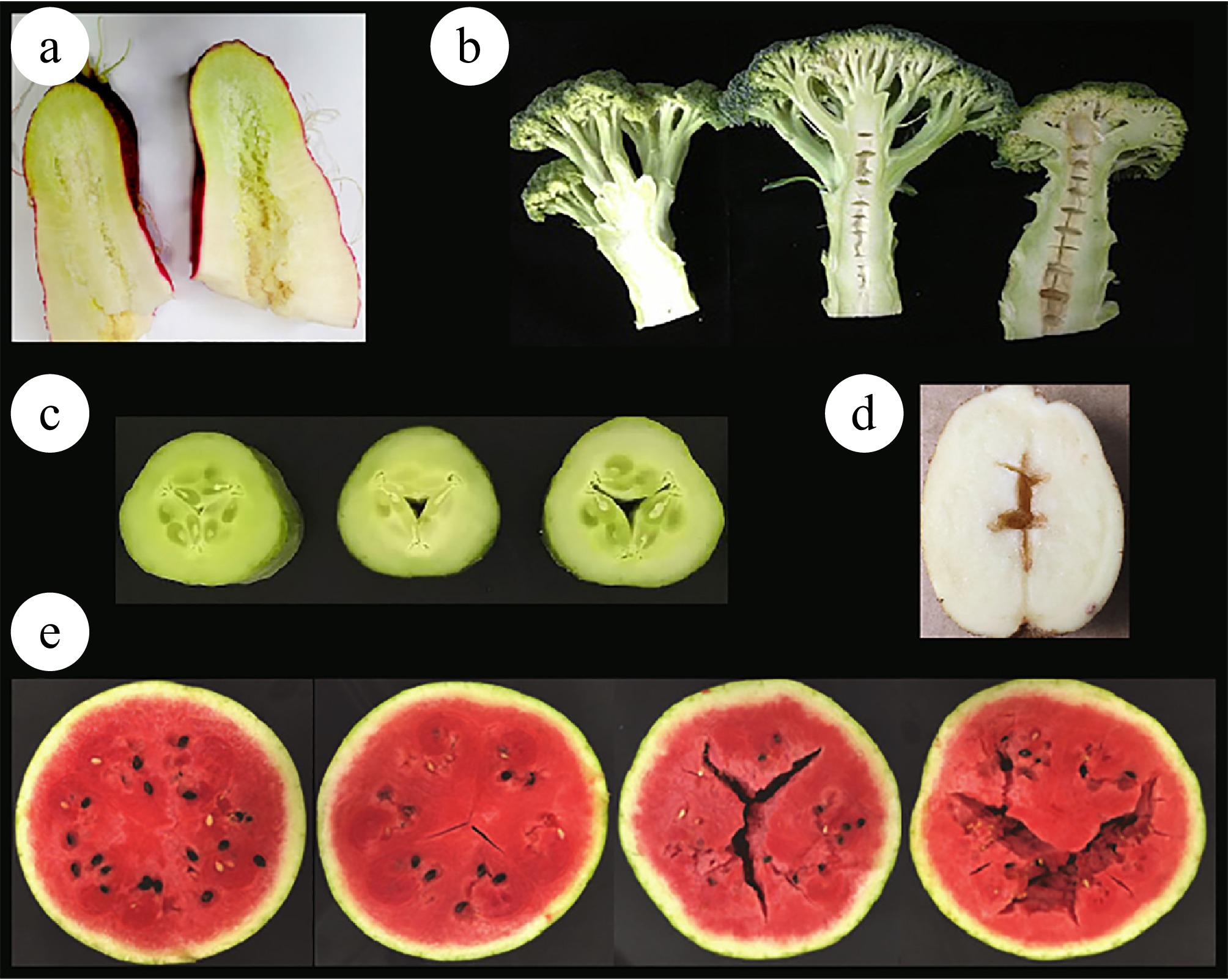

The role of vegetables in human life and economic development is becoming increasingly significant. The quality of vegetables have consistently been a considerable breeding objective, typically classified into three principal categories: commodity quality (referring to attributes such as shape and color), flavor, and nutritional quality (encompassing aspects like sugar-acid ratio and vitamin content) and safety quality (relating to pesticide residues, for instance). Hollow heart is a defect that manifests as a deficiency in commodity quality and is frequently observed in vegetable crop production. The phenomenon appears as a hole in the center of the fruit, stem, root, inflorescence, or seed, yet the appearance is normal (Fig. 1).

The formation of hollow heart results from the interaction between genotype and environmental factors[6]. It primarily impacts the processes of cell division and differentiation, particularly the distinction between the peripheral and central regions[7]. Hollow heart can be regarded as an example of plant adaptation to the environment. One such adaptation is the hollow internodes of deepwater rice, which function as snorkels to facilitate gas exchange with the atmosphere[8]. Nevertheless, in the majority of instances, the presence of hollow heart will result in a reduction in both the yield and nutritional value of the vegetable crops[9]. If the hollow heart appears in the fruit or inflorescence, it will also reduce the seed yield. Thus, the hollow heart is an urgent and pressing issue that demands resolution.

In recent years, there has been a notable increase in the focus on the quality of vegetables. Nevertheless, a significant limitation of the current research is the paucity of studies on hollow heart in vegetable crops, and the absence of a comprehensive system to address this issue. In light of recent advances, this review presents a comprehensive account of the formation and detection of hollow heart in vegetable crops, while also delineating potential avenues for future research. This can provide valuable insight into the reduction of hollow heart formation, the establishment of a foundation for hollow heart resistance breeding.

-

In production, the hollow heart of a given variety under disparate environmental and cultivation conditions exhibits considerable instability. That is to say, the formation of hollow heart is susceptible to influence from external factors. Here, the impact of temperature, soil water content, fertilizer, and cultivation pattern on the formation of hollow heart in vegetable crops is discussed. Although each factor is discussed separately, it should be noted that there are interactions among these factors, which collectively influence the formation of hollow heart[6].

Temperature

-

The optimal temperature range for vegetable growth varies by species. Exceeding or falling below this range can negatively impact the crop, including the formation of hollow heart. In potato (Solanum tuberosum), the development of hollow heart and a brown center was induced by cool growing temperatures (10−18 °C) during and shortly after tuber formation[10]. Of course, if the temperature is increased after tuber germination, the incidence of the hollow heart is also reduced[11], but hot weather will also increase the hollowness and black heart of potatoes[12]. Similarly, a high soil temperature (approximately 30.7 °C) during the 16−30th d after sowing also leads to a hollow heart in radish (Raphanus sativus), which may be attributed to a reduction in cytokinin activity and a low proliferation of xylem parenchyma cells in the intercellular spaces in the center of the root[13]. In garden pea (Pisum sativum), Halligan found that when the seed moisture content was 70%–80% at harvest maturity, the average daily temperature of 25 °C for five days was sufficient to produce more than 20% hollow seeds, while 32−35 °C was sufficient to produce 80% hollow seeds[14]. However, Shinohara et al. demonstrated that when seed moisture content decreased to 15%−25%, increasing hourly thermal time did not increase the incidence of hollow heart in most varieties of garden pea. This may be related to the starch deficiency in the adaxial region of the cotyledons[15]. Further experiments are needed to prove this statement.

Soil water content

-

Drought can induce the formation of hollow heart in potato and is more serious with the duration of stress[16] or in high-temperature environments[2]. In this instance, the hydrolysis of starch into soluble sugars within the potato tuber results in a reduction in water potential. This is followed by the rapid reabsorption of water by the tuber, which causes the perimedullary zone to expand at a faster rate than the pith, leading to the formation of hollow heart[17]. In addition, flooding or rainfall can also result in internal disorders in potato, particularly during the harvesting and hauling periods[18]. Furthermore, frequent or abrupt alterations in soil moisture levels, such as droughts following heavy precipitation, also elevate the likelihood of hollow heart formation[19]. Besides, the irrigation method exerts a discernible impact on the formation of hollow heart. For example, Sanders & Nylund found that low-volume mist irrigation resulted in a higher incidence of hollow heart formation than furrow irrigation in potato crops[20]. It was speculated that mist irrigation was more conducive to reducing drought stress and maintained the soil and tuber in an active state.

Fertilizer

-

Nitrogen is the most essential element for the optimal growth of vegetable crops. A substantial increase in nitrogen application during potato tuber formation will lead to an increase in hollow rate, predominantly due to cell expansion and a disruption in the plant's nutrient balance[16]. Similarly, an increase in hollow heart was observed in the watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) variety 'Queen of Hearts' when the nitrogen pretransplant nutritional conditioning rate was tripled (from 75 to 225 mg·L–1)[21]. Similarly, Akoumianakis et al. observed that the highest hollow rate was in radish at a nitrogen application level of 450 mg·L–1[22]. Conversely, Kaymak et al. found that a lack of nitrogen in the soil would also result in hollow heart in radish[23].

Furthermore, the two essential elements, phosphorus and potassium, also influences the formation of hollow heart. For example, an 80 g∙m−2 humic acid treatment increased the phosphorus and potassium contents in both the soil and tubers of potatoes, and resulted in a substantial decrease in the incidence of hollow heart[24]. Besides, the incidence of hollow heart in watermelon was influenced by the pretransplant nutritional conditioning of phosphorus at concentrations of 5, 15, or 45 mg·L–1[21]. Similarly, the application of potassium resulted in a significant reduction in the incidence of hollow potatoes, from 45.9% to 5.2%. This effect may be exclusive to soils with elevated potassium levels, as evidenced by the observation that potassium supplementation in deficient soils resulted in an increased incidence of hollow heart[25], a phenomenon that merits further investigation.

The role of other micronutrients in the formation of hollow heart can not be ignored. Van der Zaag & Ffrench found that a reduction in soil calcium levels resulted in an increased incidence of hollow heart in potato[26], which they attributed to cell death and tissue necrosis[27]. The defect can be mitigated through soil fertilization[28], whereas foliar application of calcium had no effect[26]. Sulfur plays a direct role in amino acid synthesis and nitrogen assimilation. The potatoes treated with EPTOP (magnesium sulfate, S0 source), AS (ammonia, SO42− source), and gypsum (SO42− source) exhibited varying degrees of hollow heart, with notable differences in the hollow rate observed across different sites and varieties[18]. In the absence of boron, initial indications of the hollow stem were observed in prem-crop broccoli (Brassic oleracea var. italica) grown in a greenhouse[29]. Nevertheless, Boersma et al. did not identify a notable correlation between the incidence of hollow broccoli stems and boron concentration in the field[30]. The specific reasons require further study.

Cultivation pattern

-

Cultivation pattern refers to the management methods and techniques used in the process of crop planting. These patterns aim to improve the yield and quality of crops, taking into account the efficient use of resources and environmental sustainability. The selection of sowing and harvesting dates is primarily influenced by temperature. For example, radish seeds sown in July and exposed to a high temperature (37 °C) during the middle of the growing season formed hollow hearts, in which the xylem vessels diverged into two sectors and widened rapidly[31]. However, late planting of the watermelon cultivar 'Super Pollenizer 1' increased the incidence of hollow heart in the marketable fruit and decreased yield[32]. In tumorous stem mustard (Brassica juncea var. tumida), the highest percentages and indices of hollow heart was observed in plants that were sown in autumn and harvested in spring the following year, while the lowest percentages and indices was observed in plants that were sown late and harvested early[33]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop local sowing dates for different regions and different vegetable crops[22].

Different cultivation densities affect hollow heart formation. When the planting is too sparse, the radish absorbs an excess of nutrients, which are accumulated in the aboveground part and are unable to meet the growth of the underground part. This results in a lack of balance in the nutrition, which manifests as a hollow heart[34]. The appropriate close spacing of potato (12 inches of seed spacing)[25] and broccoli (5.56 plants·m−2)[35] has increased interplant competition for available nutrients, thereby limiting the excessive growth of product organs. This approach reduced the hollow rate and avoided any impact on yield and quality.

Grafting is an effective method for enhancing stress tolerance and yield of select vegetable crops. Interestingly, grafting influences the formation of hollow heart. The incidence of hollow heart was reduced by 25%–30% when triploid watermelon were grafted onto interspecific squash hybrid rootstock 'Carnivor' (interspecific hybrid rootstock, Cucurbita moschata × C. maxima). Additionally, the fruit tissue firmness increased, which may be related to alterations in the composition of cell wall polysaccharides[9]. Similarly, Devi et al. reported that hollow heart formation was high for the watermelon cultivar Secretariat nongrafted[36].

Factors that induce hollow heart include pollen viability and pollinator activity during pollination[37]. The former is affected by temperature and rainfall, while the latter is contingent upon pollinator diversity and activity. The production of viable pollen by triploid watermelon is insufficient, necessitating diploid pollen sources. As the distance between triploid and pollenizer plants increased, the incidence of hollow heart also increased[6]. Besides, hollow heart exhibited a quadratic response concerning pollinizer frequency, with the lowest amount observed at 33% pollinizer frequency and the highest at 11%[38].

-

As a regulator of plant growth and development, hormones are also involved in the formation of hollow heart. For example, the production of endogenous cytokinin in the hollow roots of Japanese radish was reduced at higher soil temperatures[13]. Similarly, Manzoor et al. found that the content of cytokinin was low during the early to mid-growth stage of hollow radish, which caused the breakdown of cells, the formation of lysigenous intercellular spaces in the root, and the accumulation of lignin[1]. In cucumber (Cucumis sativus), Qin et al. determined that the content of gibberellin (GA) and zeatin (ZT) was low in hollow fruits, while the content of abscisic acid (ABA) showed no regularity[39]. In contrast, Fan et al. observed that the content of GA, 3-indole butyric acid (IBA), and ZT was elevated in hollow fruits relative to non-hollow fruits, while the ABA content exhibited an inverse pattern[40]. For specific parts of cucumber fruit, the content of indole-3-acetic acid was lower in the carpel than in the flesh[3], and the content of IBA and GA was higher[40]. Fan et al. also discovered a significant positive correlation between hollow grade and the contents of GA and ZT. It was hypothesized that the hollow degree may be influenced by ZT, potentially due to its effect on the transverse diameter of the fruit[40]. The discrepancies in the findings are attributed to the variations in the studied varieties or the timeframes of measurement across the aforementioned studies. This highlights the intricate nature of hormonal regulation in the formation of hollow heart, yet there is a lack of comprehensive studies that elucidate this phenomenon in depth.

Moreover, evidence indicates that exogenous hormones influence the development of hollow heart, as detailed in Table 1. It can be seen from the table that current research focuses on cytokinin and auxin. Of these, 1-(2-chloro-4-pyridyl)-3-phenylurea (CPPU) has been reported to be the most prevalent. However, no reports were found regarding ABA, GA, and ZT. Please refer to Table 1 for further details and key findings.

Table 1. Role of exogenous hormone on the formation of hollow heart in vegetable crops.

Exogenous hormone Concentration Application method Plant species Key findings Ref. Ethephon (2-chloroethylphosphonic acid) 4 oz·acre−1 One foliar spray at the time of tuber initiation potato Hollow heart was significantly reduced when the largest tuber set was approximately 30 mm in diameter. [41] Na-salt of α-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) 50 mg·L−1 Foliar spray in every three days from 16 to 30 d after sowing Japanese radish The root thickening rate slowed and lignin formation actived, resulting in a higher density of vessels and hollow heart. [42] 1-(2-chloro-4-pyridyl)-3-phenylurea (CPPU) 5 mg·L−1 Spray on the leaves every

3 d from the 11th to the

40th d after sowingJapanese radish The central region of the root filled with parenchymatous cells, vessels were sparsely arranged, and the hollow heart decreased. [43] CPPU 0.1, 1, 10 mg·L−1 Foliar spray at different

growth stageJapanese radish CPPU or 6-BA resulted in sparsely arranged vessels and fewer hollow roots during the middle of the growth stage, while NAA caused a high density of vessels and more hollow roots during the first half of the growth stage. [44] 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) 1, 10, 100 mg·L−1 NAA 1, 5 mg·L−1 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid 50, 200 mg·L−1 Localized applications

to ovaryTriploid watermelon The treatment increased hollow fruit in a concentration-dependent way. [45] CPPU 50, 100, 200 mg·L−1 The treatment did not increase yield or fruit quality but reduced hollow fruit. CPPU 5 mg·L−1 Ovary spray on a day

before flowering, the

day of flowering, and

a day after floweringOriental melon (Cucumis melo L. var. makuwa Makino) Ovary spray on a day before flowering reduced the hollow ratio and substantially increased the proportion of unfertilized seeds. [46] -

As previously stated, the formation of hollow heart is influenced by environmental and cultivation conditions. However, in actual production, it has been observed that some varieties do not show hollow heart under any circumstances, while some varieties are susceptible to showing hollow heart, with the degree of occurrence varying in response to environmental conditions[2]. It indicated that the hollow heart was controlled by genes and meanwhile affected by the external environment[30]. Based on these characteristics, studies for gene mapping were carried out.

In broccoli, the genetic map constructed following specific locus amplified fragment sequencing in a double-haploid segregation population identified QHS.C09-2 as the major locus controlling the hollow stem trait, which could explain 14.1% of the phenotypic variation[2]. In tetraploid potato, Bradshaw et al. identified one quantitative trait locus (QTL) for internal condition (hollow heart) with a single copy of an allele for increased defects. Additionally, a molecular maker PACMGC_358.8S5 of amplified fragment length polymorphism was also identified[47]. Subsequently, based on a linkage map in a tetraploid population of potato derived from an Atlantic × Superior cross, Zorrilla et al. identified five QTLs for the incidence of hollow heart. Two QTLs were located on chromosomes 3 and 5 of Atlantic, while the remaining QTLs were located on chromosomes 3, 6, and 12 of Superior. Seven QTLs were also identified that explained pitted scab and six QTLs that explained tuber calcium, which were also related to the formation of hollow heart[4].

In cucumber, hollow size (carpel rupture) has been previously considered to be controlled by a single gene in immature fruit[48] and by two or three genes at the mature stage[49]. In a subsequent study of the Sikkim cucumber (Cucumis sativus var. Sikkimensis), Wang et al. collected the phenotypic data on mature and immature fruit hollow size (MFH and FH, respectively) in recombinant inbred lines, and MFH in the F2:3 population. Based on the linkage maps, they found that three QTLs were identical in both MFH and FH. The mfh3.1/fh3.1 appeared to reduce hollow size, while the mfh1.1/fh1.1, and mfh2.1/fh2.1 increased it. Therefore, it was demonstrated that there may be multiple locus controls in both the immature and mature stages. Besides, a significant positive correlation was identified between hollow size and fruit size. Subsequently, it was determined that mfh1.1/fh1.1, and mfh3.1/fh3.1 were in the same location as the fruit length and fruit diameter QTLs. However, no candidate gene associated with hollow size was identified[50]. Later, Zhou et al. conducted fine mapping for hollow heart using bulked segregant analysis and competitive allele-specific PCR in the F2 population of South China ecotype cucumber. A single candidate region was identified on chromosome 1, in which the aluminum-activated malate transporter 2 (CsALMT2) was predicted. A single-nucleotide polymorphism was identified to result in an amino acid substitution in the coding protein of CsALMT2. This substitution occurred in the first exon, with threonine present in the hollow variety and alanine present in the non-hollow variety[51].

In a recent study, Wei et al. investigated the hollow heart observed in the fleshy roots of red-skinned radishes. A genetic analysis showed that the trait may be controlled by two independent recessive genes, which were identified on chromosomes R04 and R05. A simultaneous transcriptome study revealed that the gene linked to the formation of hollow heart was significantly enriched in several biological processes, including cell death, cell wall macromolecule metabolic process, chitin catabolic process, and the response to water stress. However, based on the mapping and transcriptome results, only one gene Rsa10025320 was predicted, which encodes a protein of unknown function. Additionally, a derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence marker was developed, which may be used for marker-assisted selection in breeding[52]. Nevertheless, there have been only a limited number of studies on gene mapping in the context of the hollow heart. This may be attributed to the fact that the hollow heart is significantly influenced by environmental factors, and the inbreeding lines with stable traits are challenging to obtain. It is recommended that this avenue of research be pursued actively in the future.

-

The advancement of biotechnology has facilitated profound research into the growth and development of plants. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of research examining the associated molecular mechanisms. As mentioned earlier, fertilizers affect the formation of hollow heart in vegetable crops, in which calcium is associated with the stabilization of cell membranes and the disintegration of cell walls and tissue collapses. These processes occur if the plant is deficient in Ca2+[53]. H+/Ca2+ antiporter 1 (CAX1) is a pivotal antiporter of the tonoplast Ca2+ concentration in Arabidopsis thaliana. The sCAX1 variant was derived by removing the autoinhibitory domain from the N-terminal region of CAX1[54]. Zorrilla et al. found that potato plants overexpressing sCAX1 showed hollow heart, in addition to damage to shoot tips and leaf margin necrosis. The abundance of calcium oxalate was observed within the vacuoles of transgenic plants, which could potentially influence the Ca2+ concentration in other cellular compartments. Further, the biomass of the cell wall was diminished, thereby substantiating the assertion that Ca2+ exerts an influence on the cell membrane and is thus implicated in the formation of the hollow heart[55].

Utilizing a multigenerational genetic population, Kubicki & Korzeniewska discovered that the empty chamber (hollow heart) in cucumber was determined by a combination of partially dominant and partially summing up genes Es1 and Es2. This represents the inaugural report of a hollow heart-related gene in cucumber[56]. As mentioned above, Zhou et al. identified the CsALMT2 gene through gene mapping[51], which was subsequently found to be located on the cell membrane and plasma membrane (and potentially on the chloroplast). CsALMT2 demonstrated specific expression in the root and fruit of cucumber (particularly the ovule-developing area). In addition, the expression level of CsALMT2 in the hollow variety was consistently lower than that in the non-hollow variety at all stages of fruit development. Additionally, it was predicted that CsALMT2 may affect the hollow heart by regulating the distribution of malic acids[51]. Moreover, the previously mapped gene Rsa10025320 showed high expression levels in hollow radish[52]. Rsa10025320 was homologous to Arabidopsis thaliana gene AT4G16535, which has been reported as jasmonate hypersensitive 3 (AtJAH3). AtJAH3 negatively regulated jasmonate and ethylene signaling via coronatine insensitive 1 (COI1), and ethylene insensitive 3 (EIN3)[57]. The amino acid sequence of AtJAH3 has similarity to the leukocyte receptor cluster-like protein, indicating that this genes may be involved in the formation of hollow heart in radish through mRNA splicing[58]. From the perspective of comparative transcriptome sequencing and physiological analysis, Li et al. observed a reduction in the expression of genes in the IAA synthesis pathway in the carpel, which resulted in a decline in auxin content during the early stages of fruit development. Subsequently, the activity of enzymes involved in lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose biosynthesis was affected, leading to incomplete development of carpel cells and the formation of a hollow heart in cucumber[3]. The study also identified a substantial number of potential candidate genes, which will serve as a valuable foundation for subsequent research. However, the specific function and regulatory pathways of these genes remain unknown.

For specific gene function, gibberellin insensitive dwarf 1a (CsGID1a), a GA receptor gene exhibits specific spatial expression patterns in the pistil of female flowers and the septum of young fruit in cucumber. The silencing of CsGID1a resulted in the formation of hollow heart and abnormalities in seed development, which may be closely related to the expression and regulation at the locule boundaries. The expression levels of auxin synthesis and transport, as well as the cell cycle, were also affected by the GA signal pathway[59]. This study initially identified the involvement of the GA signaling pathway in hollow heart, yet the underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated. In a recent study, Cheng et al. identified SPATULA and ALCATRAZ (encoding two bHLH transcription factors) as regulators of the proliferation and differentiation of transmitting tract cells. They influence the degree of separation of the carpels, thereby regulating the formation of hollow hearts and female sterility in cucumber. SPATULA and ALCATRAZ can form protein dimers with themselves and with each other, and there is function redundancy. Besides, the protein partner WUSCHEL-related homeobox1 (CsWOX1) was found to interact with the dimers. In addition, genes involved in auxin-activated signaling pathways and cell wall organization were identified as potential targets[60]. It should be noted that SPATULA, ALCATRAZ, and CsGID1a not only influence the formation of hollow heart, but also affect fertility. Multiple cucumber germplasm resources with hollow heart are fertile, indicating the existence of additional genes and regulatory pathways. Moreover, from the above two studies, it can be seen that the hollow heart in fruit may be related to locule development. The development of the gynoecium and locule in Arabidopsis has been studied extensively, and some of these studies have provided ideas for the research of hollow heart in other vegetable crops[61,62]. However, as a model plant for vegetable research, no studies have directly investigated the hollow heart in tomato. Two phenotypes of hollow heart can be found in some studies. One was that seeds and locule gel did not fill the space between the mesocarp and placenta. For example, after knockout of AFF (All-flesh fruit, SlMBP3), the locule tissue was changed from a jelly-like substance to a solid state, then the hollowness was found, but the seed development was normal[63]. Another was the hollowness in the center of the placenta, such as the fruit of the 'MLK1' (multi-locule) line[64]. These studies on locule development may help to reveal the mechanism of hollow heart formation in the future.

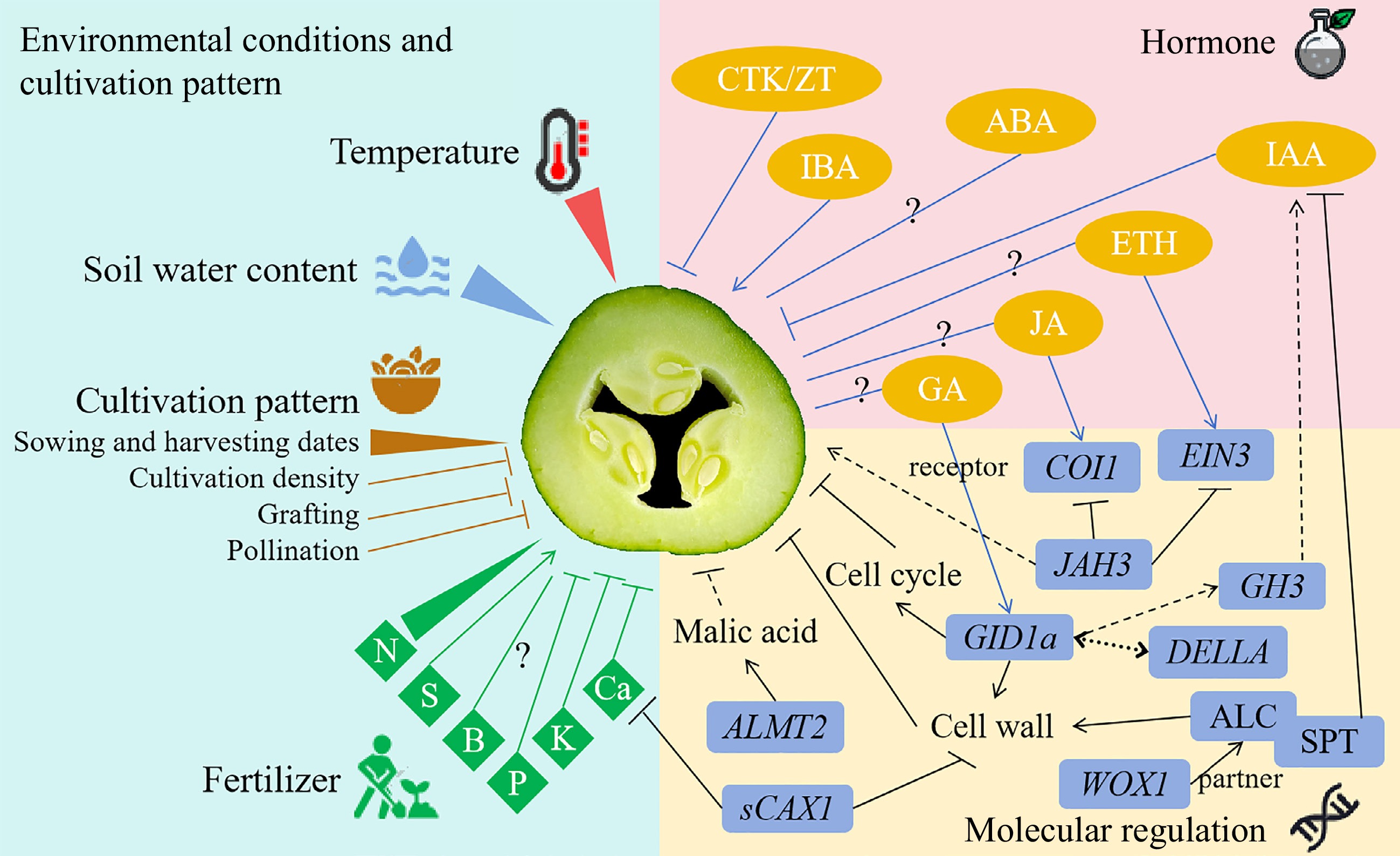

It is noteworthy that the majority of studies have indicated the potential involvement of auxin and cell wall processes in the formation of the hollow heart. These findings suggest the existence of an underlying mechanism that warrants further investigation. In light of the above studies and discussions, a hypothetical regulatory model of hollow heart formation in vegetable crops is proposed (Fig. 2). The model integrates the environment and cultivation patterns, hormones, and molecular mechanisms. It can be seen that the formation of hollow heart is a complex and diversified process, and further efforts are needed to reveal the mechanism.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical regulatory model of hollow heart formation in vegetable crops. The center picture (hollow heart in cucumber) is a depiction to show the hollow heart trait and does not represent a specific vegetable species. The solid lines indicate the proven regulation, while the dashed lines indicate the assumed regulation. Arrows indicate positive regulation or promotion, while short lines indicate negative regulation or inhibition. The double sided arrow indicates that there is a feedback regulation between the two genes. The sharp triangle represents that there are both positive and negative regulations. The question mark represents the regulation pattern should be further studied. N, nitrogen. S, sulfur. B, boron. P, phosphorus. K, potassium. Ca, calcium. CTK/ZT, cytokinin/zeatin. IBA, 3-indole butyric acid. ABA, abscisic acid. IAA, indole-3-acetic acid. GA, gibberellin. ETH, ethylene. JA, jasmonate. COI1, coronatine insensitive1. EIN3, ethylene insensitive 3. JAH3, jasmonate hypersensitive 3. GID1a, gibberellin insensitive dwarf 1a. GH3, Gretchen Hagen3. ALMT2, aluminum-activated malate transporter 2. sCAX1, H+/Ca2+ antiporter 1 without the autoinhibitory domain from the N-terminal region. WOX1, WUSCHEL-related homeobox1. ALC, ALCATRAZ. SPT, SPATULA.

-

Hollow heart is a serious internal defect that cannot be discerned visually unless the organ is cut. In the sale and processing of vegetables, such as potato slicing and pickled cucumber manufacture, the detection of hollow heart is of great importance. The most straightforward method for detection is random sampling and subsequent cutting for observation[39]. The characterization of hollow hearts in different product organs of different vegetable plants requires the use of diverse methodologies. For example, it can be further classified according to the ratio of the cross-sectional hollow area to the carpel area[39], or to the entire cross-sectional area in cucumber[51]. This standard is also applicable to the majority of product organs, while further investigation methods and standards must be developed for other irregular organs (such as the stem of broccoli). However, this method is only appropriate for small-scale investigation and evaluation, and for large-scale processing, non-destructive detection methods are required. The simplest non-destructive testing method is based on size assessment. For instance, measuring the diameter and weight can speculate whether there is a hollow heart in potato. It is hypothesized that the occurrence of a hollow heart is more prevalent in larger potatoes[65]. Nevertheless, this rudimentary assessment results in the majority of harvested tubers being discarded, with a concomitantly low degree of accuracy.

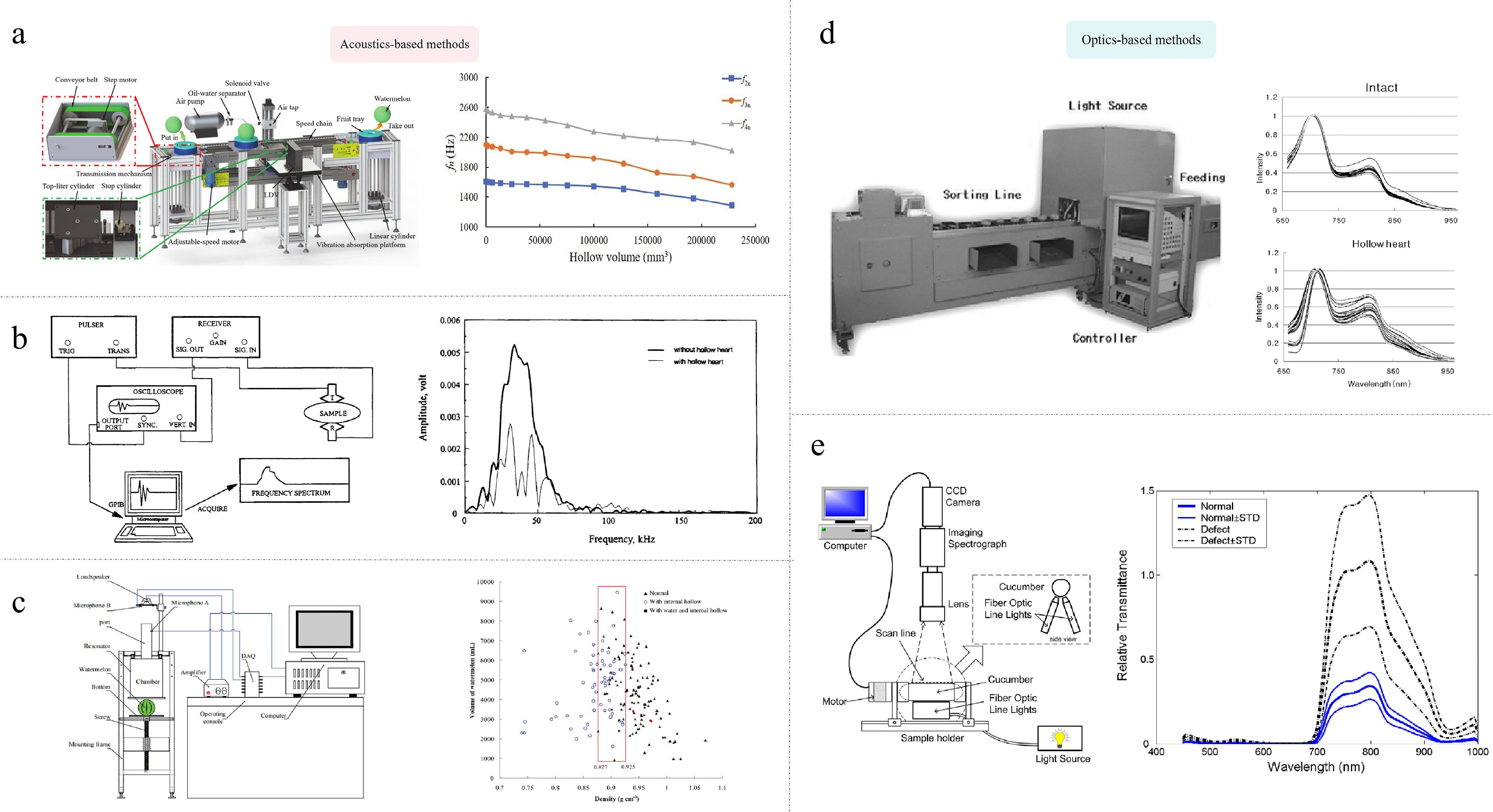

Acoustic-based methodologies were proposed by practical experience, for example, we often beat and listen to the sound to judge the quality when picking watermelons. This method employs the distinctive attributes of the resonance frequency and the energy distribution within the acoustic spectrum to identify hollow heart. For instance, the impact of a potato on a steel plate resulted in a higher sound magnitude from a solid tuber than from a hollow one. These characteristics can be extracted from the microphone signal and analyzed using linear discriminant analysis, with an approximate classification accuracy of 98%[66]. Similarly, an impulse vibration method based on three-dimensional scanning laser vibrometry and a wavelet transform method can predict hollow heart in watermelon (Fig. 3a)[67]. However, the method is unable to identify relatively small hollow hearts and the presence of noise interference hinders its efficacy. An alternative acoustic-based approach is ultrasonics. Cheng & Haugh observed that the ultrasonic signal transmitted by hollow potatoes exhibited reduced strength, prolonged duration, and a greater number of peaks and troughs compared to the signal transmitted by non-hollow potatoes (Fig. 3b). This phenomenon may be attributed to the reflection of the signal within the hollow region of the potato[68]. Similarly, Watts & Russell have successfully detected a hollow heart as small as 3 mm in diameter by ultrasonics in potato tubers[69]. The potential benefits of an ultrasonic detection system include reduced purchase and operating costs, as well as a reduced health risk. However, there were also significant challenges, primarily related to the coordination of frequency and resolution. Furthermore, Helmholtz resonance can also be applied for the detection of hollow heart. This method uses the principle that the resonant frequency is proportional to the effective volume of the resonator's chamber to quantify the volume, and incorporates a weight detection apparatus at the base to ascertain the density of the object. Xu et al. found a discrepancy in the density of normal and hollow watermelons using Helmholtz resonance. Watermelon with a density of less than 0.877 g·cm−3 had obvious hollow heart or porous tissues (Fig. 3c). An overall correct percentage reached 82.5% according to this standard[70].

Figure 3.

(a)−(c) Acoustic-based, and (d), (e) optics-based detection methods of hollow heart in vegetable crops. (a) Impulse vibration[67]. Left, pressurized-air excitation device system. Right, the effect of hollow volume on normalized second to fourth resonance frequencies. (b) Ultrasonic[68]. Left, the schematic diagram. Right, frequency amplitude spectra of the transmitted signals in hollow and non-hollow potatoes. (c) Helmholtz resonance[70]. Left, schematic diagram. Right, the density distribution of watermelons with internal hollow (with water) or normal. (d) Visible/near-infrared transmittance[73]. Left, measuring system. Right, The range-normalized transmittance spectrum of an intact potato or with hollow heart. (e) Hyperspectral imaging[75]. Left, schematic of transmittance measurement system. Right, mean relative transmittance spectra of normal and defective cucumbers and their standard deviation (STD) spectra after one day of bruising.

Optics-based methods have also been used for hollow heart detection. For example, an X-ray can effectively identify hollow heart. The efficacy of this detection mode is contingent upon the efficiency of transmission and recognition. In potato, the presence of water during the detection process can result in the masking of external tuber indentations, thereby facilitating a more accurate delineation[71]. Nevertheless, this approach is only applicable to the detection of large-area hollows, and the identification of smaller hollows remains elusive. Furthermore, the deployment of such equipment necessitates a cost-benefit analysis and an assessment of the requisite protection measures. Besides, by using a spectrophotometer, the spectral absorption curve of potato tubers was measured at a wavelength of 710 nm. Tubers exhibiting hollow heart demonstrated selective absorption, with a lower absorption rate than that observed in unaffected tubers. That measurement error may arise due to factors such as tuber skin thickness, the presence of scarred tissue, and the accumulation of soil on the tubers. However, the proportion of cases in which this occurs is very small[72]. Kang et al. detected hollow heart in potato by using visible spectroscopy/near-infrared transmittance (530−1,100 nm), achieving a classification rate of 83% (Fig. 3d)[73].

Hyperspectral imaging technology is a method of obtaining optical images and spectral information of different wavelengths by integrating optical imaging, spectral analysis, and computational techniques. Meanwhile, it is a means of extracting feature information of objects through the use of computer technology and pattern recognition analysis. Cen et al. found that the two-band ratio of 887/837 nm in transmittance mode could be applied for the rapid and real-time detection of internal defects in pickling cucumbers[74]. Similarly, a hyperspectral transmittance imaging technique in conjunction with partial least squares discriminant analysis was employed for the detection of hollow hearts in pickled cucumber. The average classification accuracy exceeded 90% (Fig. 3e)[75]. Liu et al. devised a classification method that employed deep feature representation with a stacked sparse auto-encoder in conjunction with convolutional neural network learning for hyper-spectral imaging-based defect detection of pickling cucumbers. The overall accuracy reached 91.1% and 88.3% when conveyor speeds were 85 and 165 mm·s−1, respectively. Additionally, the average running time for each sample was less than 14 ms, indicating significant potential for further application[76]. In potato, Dacal-Nieto et al. applied the hyperspectral imaging technique (1,000−1,700 nm) to detect the presence of the hollow heart in potato tubers. The correct recognition rate of 89.10% was achieved by support vector machines and different image processing techniques[77]. Lately, Huang et al. determined that the semi-transmission hyperspectral imaging technology combined with an artificial fish swarm algorithm-support vector machine model was the optimal recognition pattern, with an overall recognition rate of 100%[78]. In summary, as technology advances, faster, more accurate, and less expensive detection methods are expected to be developed and implemented. However, specific case studies of practical applications, especially in large-scale food sorting and processing, are lacking. Further research is expected to fill this gap.

-

Hollow heart has been observed in vegetable crops early, yet comprehensive and systematic research on this quality defect has yet to be conducted. This may be attributed to the fact that the trait is significantly influenced by environmental factors. In this review, the effects of temperature, soil water content, fertilizer, cultivation pattern, and hormones on the formation of hollow heart were analyzed. Then, the research on hollowness-related gene mapping and molecular mechanisms in recent years was discussed. In addition, the non-destructive detection of the hollow heart is also an important part of the processing of vegetable products. Accordingly, this paper presents a summary of the detection methods based on acoustics and optics.

In light of the above studies and discussions, a multitude of potential avenues for future research are proposed. (i) Although the hollow heart is not generally thought to be caused by disease, there have been reports that the potato mop top virus caused internal hollow necrotic spots or concentric rings in potato[79]. Therefore, the relationship between disease and hollow heart is also worth exploring. (ii) It would be beneficial to elucidate the role of hormones in the formation of hollow heart, as this could provide support for endogenous modification or exogenous application to reduce hollow heart. (iii) The cellular and molecular mechanisms by which vegetable plants integrate environmental signals during the formation of hollow heart warrant further investigation. (iv) Further verification is required for other regulatory pathways that are worthy of gene mapping and mining. The application of multi-omics techniques and modern biological technology can facilitate the discovery of novel regulatory mechanisms, such as epigenetics. Meanwhile, deeper research of functions for reported genes and the construction of a genetic regulatory network are also required. (v) A model and detection method suitable for complex-shaped vegetable crops (such as broccoli) should be established. Furthermore, the correction and adaptation of developed models should be improved and re-optimized to guarantee their effectiveness. Concurrently, enhancements to the precision of the hardware platform for detecting smaller hollow hearts are required, as are further improvements to the accuracy of the detection process.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32272724).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xin M; literature collection: Li J, Jia J; draft manuscript preparation: Li J, Jia J; tables and figures design: Li J, Xin M; manuscript modification and review: Xin M, Liu X, Qin Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li J, Jia J, Qin Z, Liu X, Xin M. 2025. Advances on the formation and detection of hollow heart in vegetable crops. Vegetable Research 5: e005 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0024-0041

Advances on the formation and detection of hollow heart in vegetable crops

- Received: 12 October 2024

- Revised: 22 November 2024

- Accepted: 03 December 2024

- Published online: 11 February 2025

Abstract: Hollow heart is a commodity quality defect that manifests as a lack of substance in the heart region of some organs, and it is a common occurrence in vegetable crop production. This phenomenon has attracted the attention of researchers from an early stage. However, no complete system for the occurrance has been formed. In this review, the influence of environmental conditions, cultivation patterns, and hormones on the formation of hollow hearts were first analyzed. Then the recent findings of gene mapping and molecular mechanisms were discussed. Additionally, the detection of hollow heart in vegetable crops was summarized from two aspects: acoustics and optics. Finally, perspectives and suggestions were put forward for further research and interest. This review may provides a basis for further research and valuable insight for hollow heart resistance breeding.

-

Key words:

- Formation /

- Detection /

- Hollow heart /

- Vegetable crops