-

In the realm of vegetable science, the varietal improvement of vegetables, along with the optimization of their agronomic traits and economic returns, is of paramount significance. Advanced genetic transformation technologies are pivotal in accomplishing these objectives.

After the application of transgenic technology in plant genetic improvement, people have tried to use different transformation methods to improve plants, such as particle-bombardment-mediated transformation, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, the pollen-tube pathway, and electroporation[1−4]. However, Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation occupies an important position in genetic transformation research in vegetables due to its many advantages, such as its high transformation efficiency, its relatively stable integration sites, and the ability to accurately introduce large-fragment DNA[5].

Agrobacterium includes Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Agrobacterium rhizogenes, which are two types of soil bacteria with a broad host range. They carry the Ti plasmid (tumor-inducing plasmid) and Ri plasmid (root-inducing plasmid) respectively, and both of these plasmids contain a segment of T-DNA[5]. Under natural conditions, Agrobacterium can infect the wounded parts of plants, then transfer and integrate a specific DNA segment (T-DNA) on its plasmid into the plant genome, thus causing the formation of crown gall tumors (caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens) or hairy roots (caused by Agrobacterium rhizogenes)[6]. The target gene carried by the T-DNA enters the plant cell, further enters the nucleus, and integrates into the chromosome of the receptor material, achieving the stable transfer and expression of genetic material and laying the foundation for genetic improvement of plants[7]. The Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation process is extremely complex and orderly, involving multiple steps and the participation of numerous genes[5]. First, Agrobacterium attaches to the surface of plant cells through some adhesion factors on its surface. This process involves some chromosomally encoded genes of bacteria (such as chvA, chvB, pscA, etc.) and some receptor proteins on the surface of plant cells[6]. Subsequently, a series of signal molecules secreted by the wounded parts of plants, such as phenolic compounds, sugars, plant hormones, etc., are sensed by Agrobacterium. Among them, acetosyringone (AS) in phenolic compounds is a key signal molecule that induces the expression of the virulence (Vir) genes of Agrobacterium[8]. The expression products of Vir genes are involved in processes such as the processing, transfer, and integration of T-DNA. After the T-DNA is transferred out of Agrobacterium, it enters plant cells through the bacterial Type IV secretion system (T4SS)[9]. Inside plant cells, T-DNA forms a complex with some virulence proteins (such as VirD2, VirE2, etc.), and through interactions with some transport proteins and the cytoskeleton in plant cells, the transport of T-DNA from the cytoplasm to the cell nucleus is achieved[10]. Finally, T-DNA integrates into the plant genome and is expressed in plant cells, thus achieving genetic transformation of the plant[10].

Traditional Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation mainly relies on tissue culture and co-culture techniques. All factors that affect the infectivity of Agrobacterium, the ability of plant cells to respond to Agrobacterium infection, and the regeneration ability of the transformants directly influence the transformation effect. Related auxiliary factors affecting Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, such as the use of antioxidants[11,12], desiccation treatment[13], microwounding treatment[14], nuclear matrix-attachment sequences[15,16], and the use of surfactants[17], play a crucial role in the success and efficiency of transformation. These auxiliary factors not only promote the infection of recipient cells by Agrobacterium but also reduce the browning and death of plant cells caused by Agrobacterium infection, and facilitate the transport of T-DNA and its integration with the recipient genome, thereby increasing the plant's regeneration rate and transformation efficiency[18].

Non-heading Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris (syn. Brassica rapa) ssp. chinensis), an annual or biennial herbaceous plant originating in China, is widely cultivated worldwide for its rich nutritional and economic value[18,19]. With the development of agricultural modernization, higher requirements have been put forward for the quality and yield of non-heading Chinese cabbage. Genetic transformation technology provides a powerful means for the improvement of non-heading Chinese cabbage varieties. Through genetic transformation, some excellent genes, such as disease-resistant genes, stress-resistant genes, and quality-improving genes, can be introduced into non-heading Chinese cabbage to cultivate new non-heading Chinese cabbage varieties with better traits[20−22].

At present, certain progress has been made in the genetic transformation research of non-heading Chinese cabbage, and the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method has been widely used in thisgenetic transformation. However, compared with model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana and tobacco, the genetic transformation efficiency of non-heading Chinese cabbage still needs to be improved, and there are problems such as unstable transformation efficiency and poor repeatability during the transformation process. These problems limit the further promotion and application of the genetic transformation technology of non-heading Chinese cabbage[23]. Therefore, in-depth exploration of the molecular mechanism of Agrobacterium infecting non-heading Chinese cabbage is of great significance for optimizing transformation techniques and improving the efficiency of transformation.

Defensin-like protein 2 (DEFL2), as a protein with a Scorpion toxin-like domain, is widely distributed in various biological species such as invertebrates, plants, and mammals[24]. Previous studies have shown that DEFL2 is involved in the non-specific innate immune response of organisms and exhibits antifungal activity in ancestors[24,25]. Given its important role in the biological immune process, studying the role of DEFL2 in the Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation process of non-heading Chinese cabbage is of great significance for understanding the interaction mechanism between plants and Agrobacterium.

This study focuses on the Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation process of non-heading Chinese cabbage, aiming to deeply analyze the gene expression changes of non-heading Chinese cabbage after Agrobacterium infection, and explore the key genes and biological pathways related to Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. At the same time, the role of DEFL2 in this process and the relationship between callus-specific genes and the efficiency of Agrobacterium infection are systematically studied. It is expected that through this study, a solid theoretical basis and effective technical support can be provided for improving the transgenic efficiency of non-heading Chinese cabbage, promoting the development of genetic engineering breeding technology for non-heading Chinese cabbage, helping to cultivate more excellent varieties that meet market demands, and enhancing the production efficiency and market competitiveness of non-heading Chinese cabbage.

-

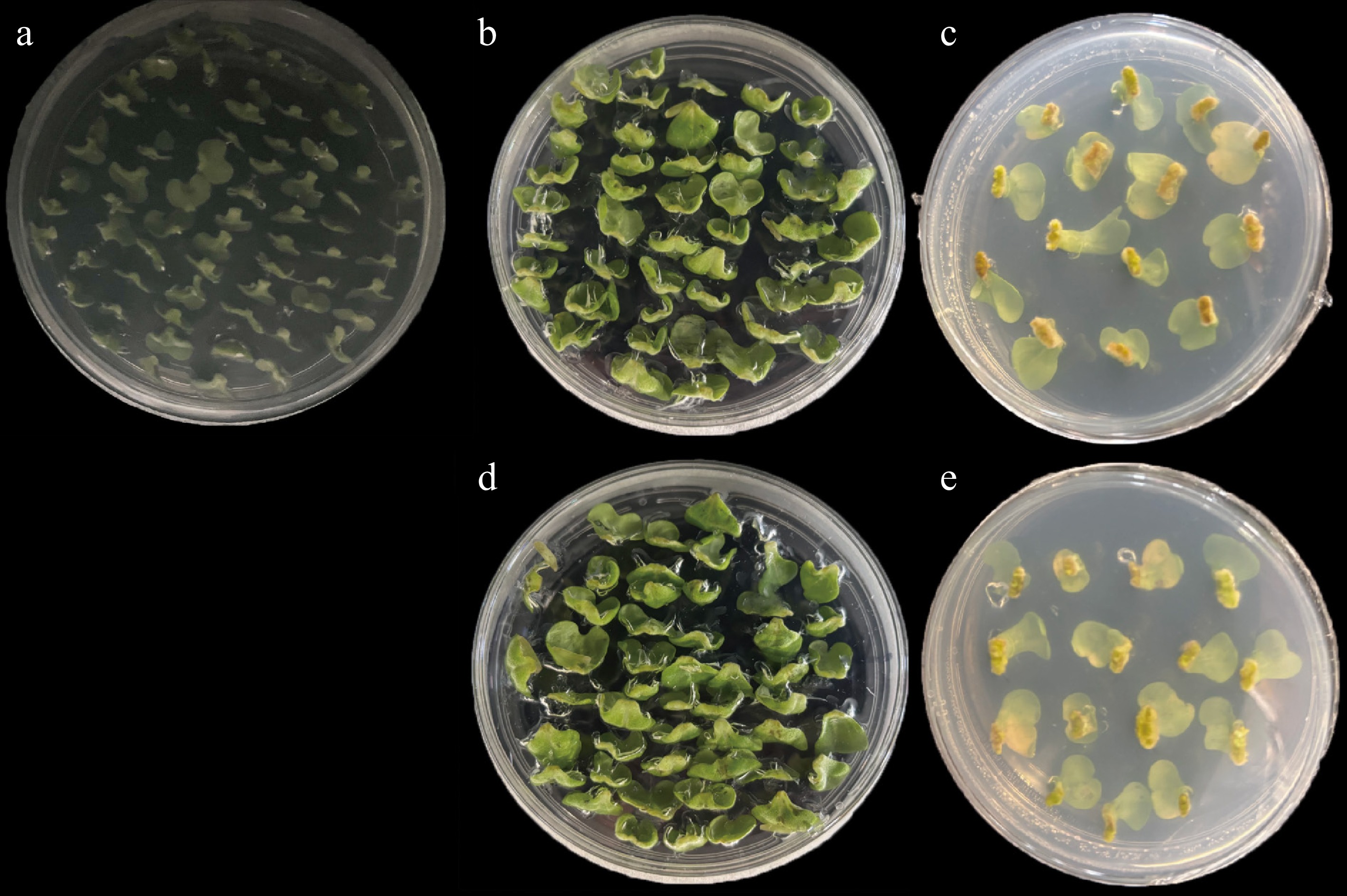

The experimental material was non-heading Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris (syn. Brassica rapa) ssp. chinensis) cultivar 'CX-49', supplied by the Brassica System Biology Laboratory, College of Horticulture, Nanjing Agricultural University. This cultivar has a growth cycle of approximately 20–25 d, allowing rapid acquisition of sterile explants[26]. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 (chromosome background C58; rifampicin-resistant) carrying the disarmed Ti plasmid pMP90 (pTiC58ΔT-DNA) was used in this study. We selected full seeds with the same color and size, added 75% ethanol and 10% sodium hypochlorite, and washed them with sterilized ultra-pure water. The seeds were evenly dispersed into a culture bottle with Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (temperature: 25 ± 2 °C; photoperiod: light/darkness = 16 h/8 h; all subsequent culture conditions are consistent with this unless specified otherwise). In the experiment, 4-day-old seedlings were carefully severed at the petiole between the leaf and the growth point, ensuring the excision of the growth point. The excised subpetioles were then inserted into the preculture medium, making certain that the wound area was in full contact with the medium for a preculture period of 2 days (designated as CK_S1, Fig. 1a). For the preparation of the Agrobacterium suspension, Agrobacterium strains carrying the plant expression vector were resuspended and diluted using MS0 liquid medium (pH 5.2). Acetosyringone (AS) was added to a final concentration of 100 μM. Subsequently, the suspension was allowed to stand at 25 °C for 4 h to prime it for the infection and transformation of explants. The explants were immersed in the infection solution and gently shaken for 8 minutes to ensure thorough exposure. Afterward, the surface-dried explants were transferred onto the co-culture medium, with the incised surface of the subpetioles in direct contact with the medium. The co-culture was carried out in the dark at approximately 25 °C for 3 d. The infected and uninfected explants were labeled as CDF1_S2 (Fig. 1c) and CK_S2 (Fig. 1b), respectively. Following co-culture, the explants were inoculated into the callus induction medium supplemented with 250 mg/L carbenicillin disodium (Carb) and 250 mg/L timentin (TMT). The incubation period in this medium was 10–14 d. The infected and uninfected explants that were cultured for 6 days on this medium were named CDF1_S3 (Fig. 1e) and CK_S3 (Fig. 1d), respectively. Additionally, to identify genes specifically expressed in callus tissue, we conducted transcriptomic analysis of non-heading Chinese cabbage leaves during the seedling stage. Immediately after the designated culture periods, the samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. These samples were reserved for subsequent physiological and biochemical analyses.

Figure 1.

Morphological changes of explants during Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation in non-heading Chinese cabbage. (a) CK_S1: Subpetioles of 4-day-old seedlings precultured on the preculture medium for 2 d. (b), (c) CK_S2 and CDF1_S2: Uninfected and infected subpetioles after co-culture on the co-culture medium for 3 d in the dark. (d), (e) CK_S3 and CDF1_S3: Uninfected and infected explants cultured on the callus induction medium supplemented with 250 mg/L carbenicillin disodium (Carb) and 250 mg/L timentin (TMT) for 6 d.

Transcriptome analysis and gene annotation

-

Total RNA was extracted from biological replicates CK_S1, CK_S2, CK_S3, CDF1_S2, and CDF1_S3 using a commercial total RNA isolation kit (Takara Biomedical Technology, Beijing, China). The quantity and purity of RNA were evaluated with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA), while their integrity was assessed via the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent, CA, USA). Polyadenylated mRNA was enriched using oligo(dT)-coated magnetic beads. First-strand cDNA synthesis utilized Invitrogen SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Cat. 1896649, CA, USA), followed by second-strand synthesis incorporating 2'-deoxyuridine 5'-triphosphate (dUTP) (Thermo Fisher, Cat. R0133, CA, USA) for strand discrimination. Uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) (NEB, Cat. m0280, MA, USA) digestion selectively degraded the second strand, enabling the construction of strand-specific libraries via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Libraries were size-selected for 300 ± 50 bp fragments and sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq™ 6000 platform (LC Bio Technology, Hangzhou, China) using paired-end 150-bp reads (PE150) according to the standard protocols.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using stringent statistical thresholds: an adjusted p-value of < 0.05 and an absolute log2FC (fold change) of ≥ 1. Functional annotation of DEGs involved Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses to characterize the biological processes and molecular pathways impacted. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was applied to the DEGs, with their expression profiles visualized across sample groups and presented as a heat map.

Validation of gene expression

-

To validate transcriptome-derived expression patterns in callus-specific genes, leaf transcriptome data were compared with pre- and post-callus growth transcriptomes. A subset of DEGs with the most significant upregulation was selected for real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis across three developmental stages of leaf and callus tissues. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer 3 software v6.0. Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR GREEN Master Mix (Vazyme Biotechnology, Nanjing, China), and relative expression levels were calculated via the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method[27].

Statistical analysis

-

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) using at least three biological replicates. SPSS v22.0 (SPSS Institute Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. GO and KEGG enrichment analysis were performed and the results visualized with the OmicShare tool, an online platform for data analysis[28].

-

In order to understand the molecular basis of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of non-heading Chinese cabbage, the DEGs between the stalk of the cotyledons of CK and Agrobacterium-infected petioles were analyzed using the stalk of the cotyledons of CK_S1, CK_S2, CDF1_S2, CK_S3, and CDF1_S3. An Illumina Seq platform was used to sequence the five samples, with three biological replicates each. Five libraries were constructed for high-throughput sequencing. To identify the DEGs, we obtained a total of 749.99 MB of raw reads and 112.52 GB of raw bases. After filtering 26.20 MB of clean reads and 108.93 GB of clean bases were obtained. The Illumina qphredQ30 of all samples was > 90% (Supplementary Table S1).

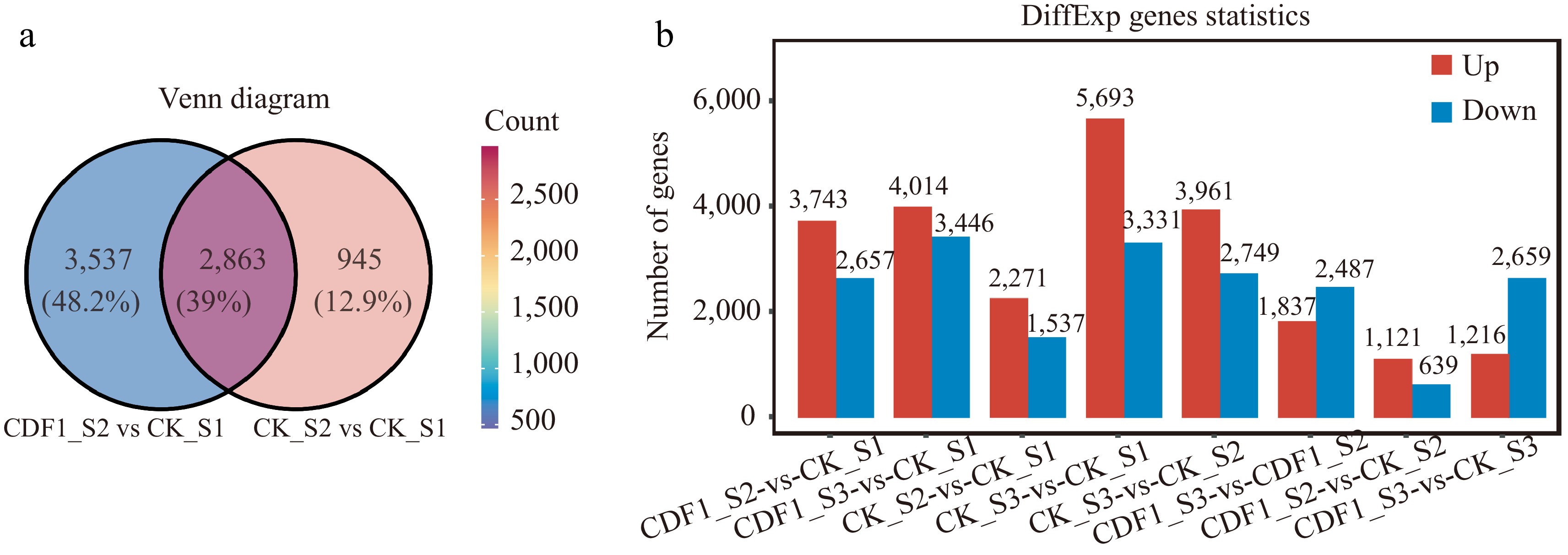

In total, 6,400 DEGs (3,743 upregulated and 2,657 downregulated) were identified in the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set (with CK_S1 as the control, DEGs were screened in CDF1_S2), and 3,808 DEGs (2,271 upregulated and 1,537 downregulated) were identified in the CK_S2/CK_S1 set (with CK_S1 as the control, DEGs were screened in CK_S2) (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Tables S2 & S3). In total, 1,121 upregulated and 639 downregulated genes were identified in the CDF1_S2/CK_S2 set (with CK_S2 as the control, DEGs were screened in CDF1_S2). In a comparison with the CK_S2/CK_S1 set, 3,537 unique and 2,863 sharef DEGs were found in the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set (Fig. 2b). These unique genes included those that show altered gene expression after the Agrobacterium infection treatment, which enables us to mine the genes responsible for Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation changes.

Figure 2.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across diverse samples in non-heading Chinese cabbage. (a) Venn diagram comparing CK_S2/CK_S1 and CDF1_S2/CK_S1. (b) Statistical data on the number of upregulated and downregulated genes in each comparison group. Red indicates upregulated DEGs, and blue indicates downregulated DEGs.

Gene functional annotation and classifcation

-

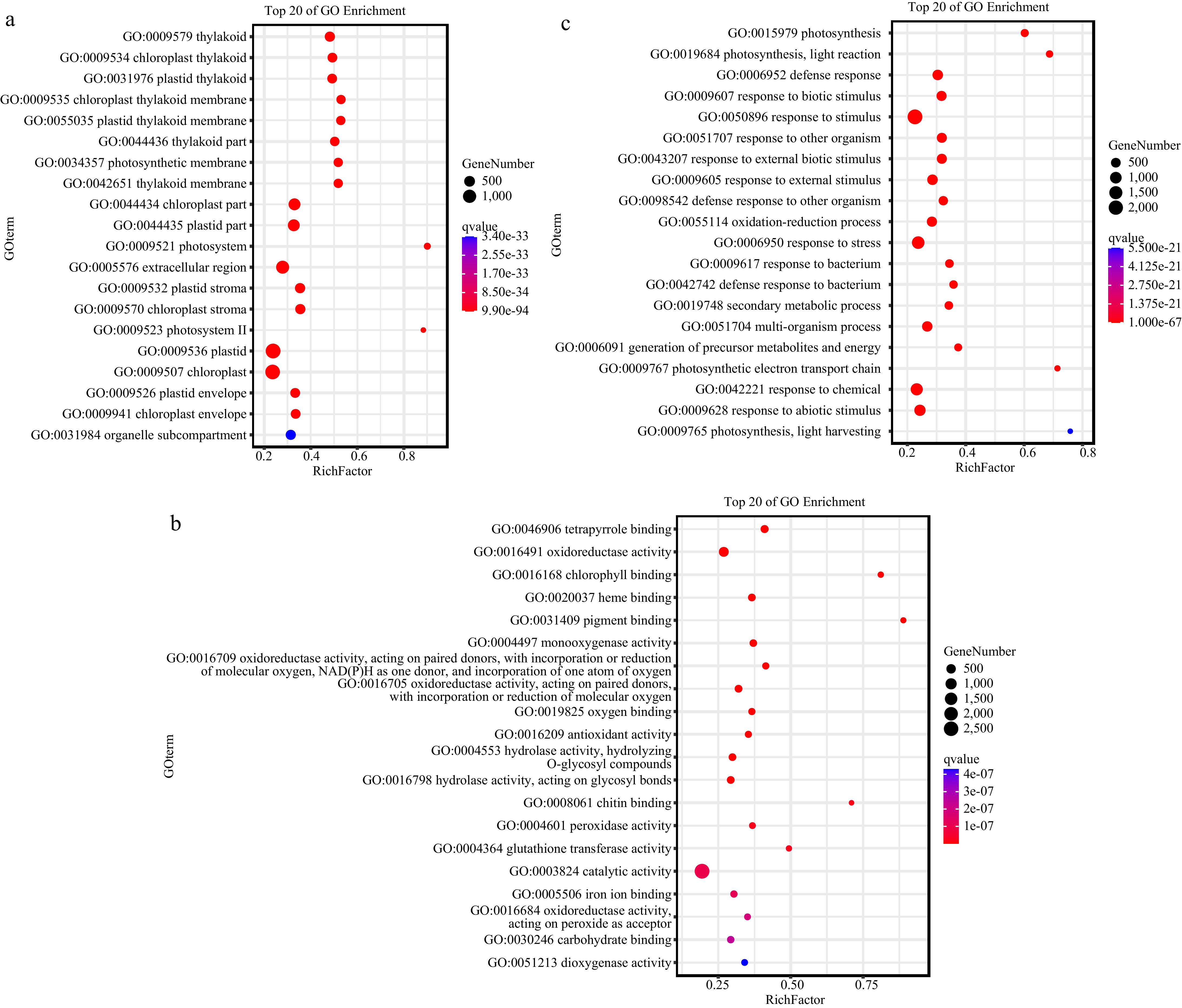

The GO functional enrichment analysis of the DEGs was performed in the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set (Fig. 3; Supplementary Figs S1−S3). In terms of cellular components, the DEGs were enriched in the thylakoid (GO:0009579), chloroplast thylakoid (GO:0009534), chloroplast (GO:0009507), and some photosystem-related pathways (GO:0009521, GO:0009523, and GO:0034357) (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. S1). After Agrobacterium infection, the gene expression related to these structures in the callus cells of non-heading Chinese cabbage underwent significant changes. It is possible that the infection triggered changes in the physiological processes related to thylakoids and chloroplasts in the cells, such as the remodeling of photosynthesis-related structures or the adjustment of functions. This may be a response of plants to Agrobacterium infection, or else Agrobacterium infection interfered with the normal development and function maintenance of these structures.

Figure 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) functional analysis of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the cotyledon stalk of the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set, which was performed using Omicshare online software.

In terms of molecular functions, the DEGs were enriched in tetrapyrrole binding (GO:0046906) and oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491, GO:0016709, and GO:0016705) (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. S2). The function of tetrapyrrole binding may be related to the synthesis or metabolism of pigments such as chlorophyll, and its changes may affect photosynthesis. Alterations in oxidoreductase activity may be involved in the plant's oxidative stress response. The infection of Agrobacterium may disrupt the redox balance within non-heading Chinese cabbage callus, and the plant responds to this stress by regulating the expression of relevant genes, reflecting the plant's response mechanism to Agrobacterium infection at the molecular function level.

Photosynthesis (GO:0015979), photosynthesis-light reaction (GO:0019684), and defense response (GO:0006952) were ranked the highest among all GO biological processes between the two sets (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. S3). The changes in photosynthesis-related processes further confirm the impact of the structural changes in thylakoids and chloroplasts at the cellular component level on physiological processes. It is likely that Agrobacterium infection affects the expression of photosynthesis-related genes, thus influencing photosynthetic efficiency. For the CDF1_S2VSCK_S2 set, the defense response remains a crucial GO biological process (Supplementary Figs S4 & S5). The enrichment of defense-response-related processes indicates that when the callus of non-heading Chinese cabbage is infected by Agrobacterium, it activates its own defense mechanism. It resists the invasion of Agrobacterium by upregulating the expression of defense-related genes, which is a typical response of plants to biological stress.

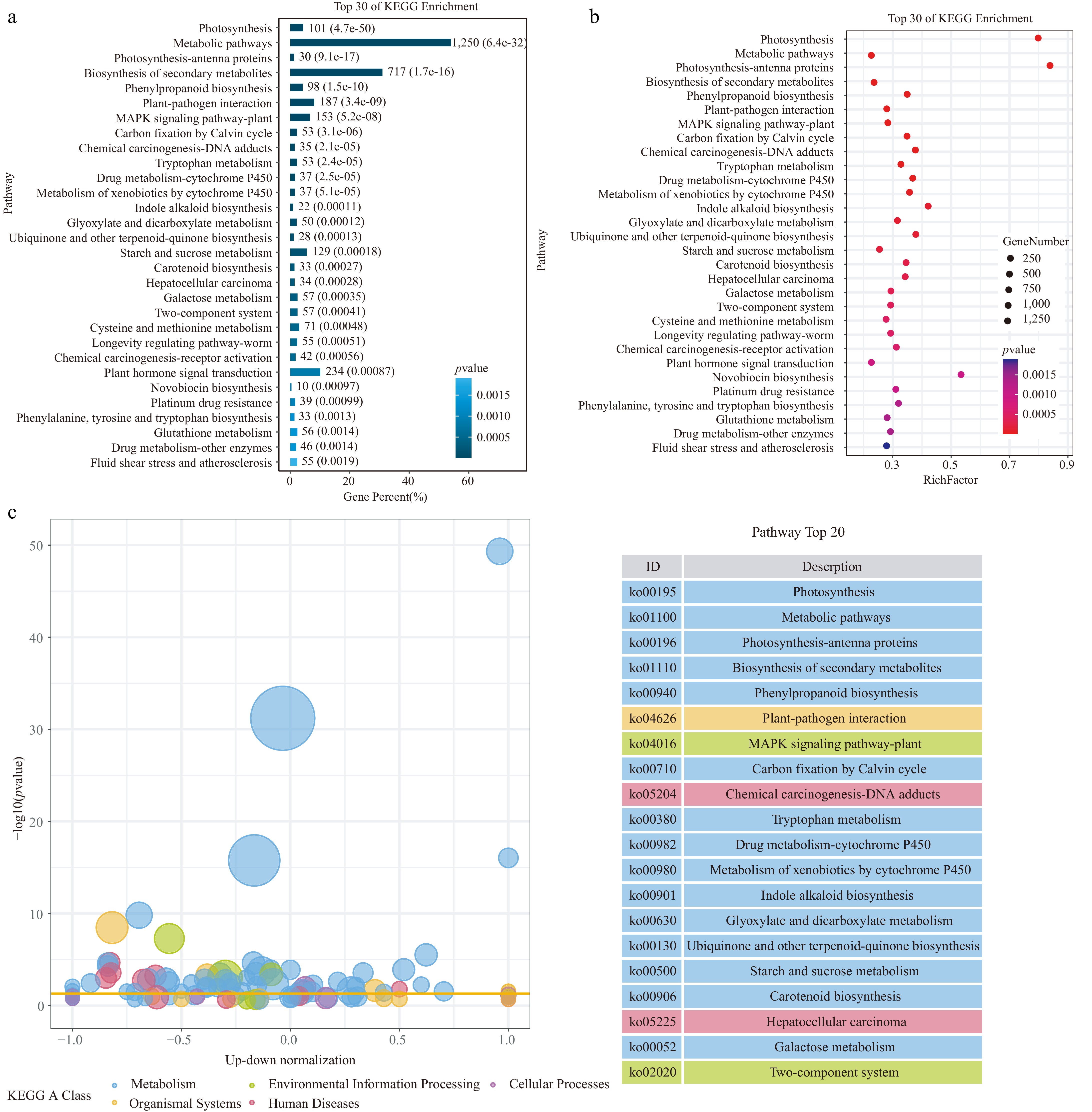

In addition, we also analyzed the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways enriched in the DEGs (Fig. 4). The main photosynthesis-related pathways, metabolic pathways, plant-pathogen interaction pathways, and signal transduction pathways were highly enriched. The photosynthesis-related pathways include photosynthesis (ko00195) and photosynthesis-antenna proteins (ko00196). Photosynthesis is a key process in plants that converts light energy into chemical energy. Antenna proteins are responsible for capturing light energy and transmitting it to the reaction center. After Agrobacterium infection, genes related to these pathways showed significant differential expression, which may affect the plant's light-energy capture and energy-conversion efficiency.

Figure 4.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of the DEGs in the cotyledon stalks of the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set. (a) Top 30 KEGG enrichment pathways. (b) Summary of the KEGG pathways. (c) Bubble plot of KEGG enrichment analysis. Different colors represent different KEGG A-class categories.

The metabolic pathways include primary metabolic pathways and secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways. Metabolic pathways (ko01100) were significantly enriched, including numerous basic metabolic processes such as carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism. Carbohydrate metabolism provides energy and carbon skeletons for cells, while amino acid metabolism is involved in important life activities such as protein synthesis. Changes in the genes of these pathways after Agrobacterium infection may alter the balance of intracellular energy supply and substance synthesis. Pathways such as the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (ko01110) and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940) were also prominent. Secondary metabolites such as flavonoids and terpenoids play important roles in plant defense responses, signal transduction, etc. Agrobacterium infection may induce plants to produce these secondary metabolites to cope with stress, and may also utilize the plant's metabolic system to meet its own survival and reproduction needs.

The plant-pathogen interaction (ko04626) pathway is crucial during the infection process. Plants recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns through pattern-recognition receptors and initiate an immune response. At the same time, pathogens secrete effector proteins to suppress the plant's immunity.

The MAPK signaling pathway of plants (ko04016) is involved in the plant's response to various biotic and abiotic stresses, transmitting signals through a cascade of phosphorylation. After Agrobacterium infection activates this pathway, it may further regulate the expression of downstream defense-related genes, affecting the plant's immune response and growth and development processes.

In the plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075) pathway, plant hormones such as auxin, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid play key regulatory roles in plant defense and growth and development. Agrobacterium infection may interfere with the signal transduction of plant hormones, change the hormone balance, and thus affect the plant's response to infection and its own growth state.

Carbon fixation by the Calvin cycle (ko00710) is an important pathway by which plants convert carbon dioxide into organic carbon. The impact of Agrobacterium infection on this pathway may change the plant's carbon metabolism, affecting the plant's growth and material accumulation. Pathways such as drug metabolism-cytochrome P450 (ko00982) and metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 (ko00980) are involved in the plant's metabolic detoxification of exogenous substances. Agrobacterium infection, as an exogenous stimulus, may induce changes in the expression of genes in these pathways to cope with Agrobacterium and the substances it brings.

Callus-specific DEGs in non-heading Chinese cabbage

-

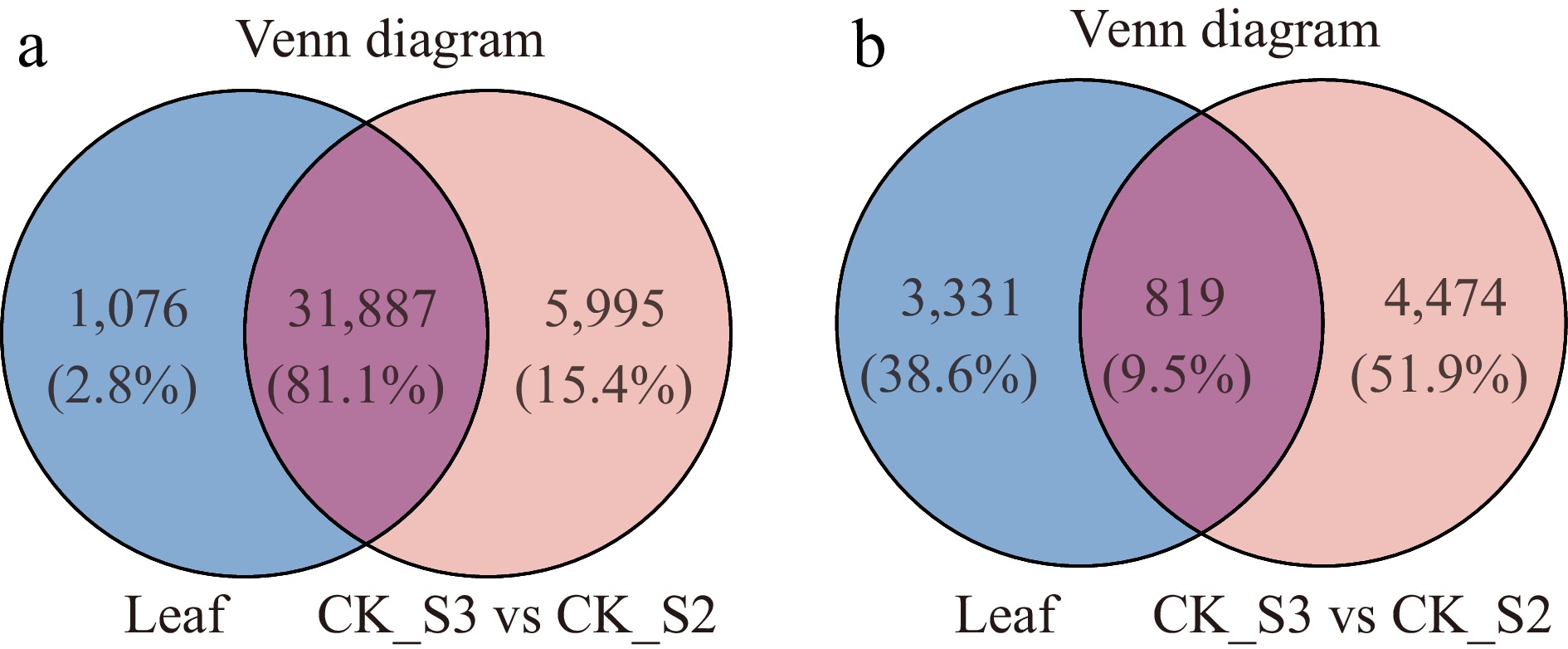

To pinpoint callus-specific DEGs, we compared the leaf transcriptome (Supplementary Table S4) with profiles collected before and after callus induction (Supplementary Table S5). This revealed 5,995 genes uniquely expressed in the callus, of which 4,474 were differentially expressed: 2,672 upregulated, 1,802 downregulated, and 970 unchanged (Fig. 5; Supplementary Tables S6 & S7). Among callus-specific genes absent from the leaves, DEFL2 (BraC05g004020) stood out. It displayed a 125-fold induction in the callus (CDF1_S2 vs CK_S1; log2FC = 6.97; false discovery rate [FDR] = 0.003) while remaining unchanged in the CK_S2 vs CK_S1 comparison (Supplementary Tables S2 & S3). This mirrors the findings of Wang et al., who showed that Brassica napus DEFL proteins confer disease resistance via jasmonic acid signalling[29]. Within GO:0006952 (defense response), DEFL2 represents the most markedly upregulated gene with a known function (Supplementary Table S8).

Figure 5.

Venn diagram analysis of (a) genes and (b) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the leaf transcriptome and the transcriptomes before and after callus growth (CDF1_S3/CK_S2).

Quantitative fluorescence PCR analysis

-

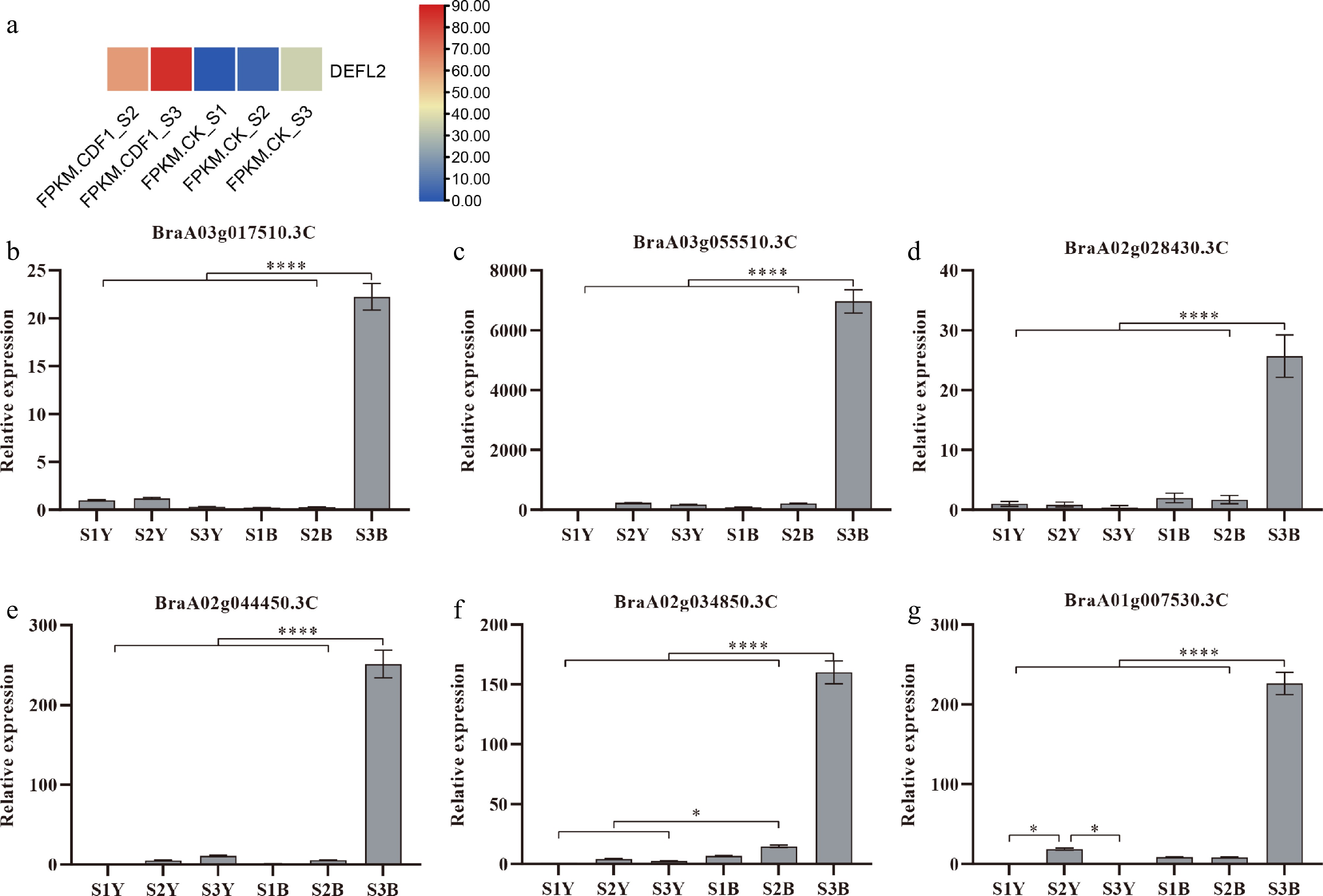

Several DEGs were randomly selected for quantitative fluorescence PCR analysis at three growth stages of the leaves and callus (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S9). It was found that the expression levels of these genes in the petioles were significantly higher than those in leaves, and the expression levels increased as the callus expanded. Since the method of obtaining transgenic non-heading Chinese cabbage through Agrobacterium tumefaciens infection is based on callus induction, these genes may play a role in improving the efficiency of Agrobacterium infection.

Figure 6.

(a) Heatmap showing the fragments per kilobase per million mapped fragments (FPKM) values of DEFL in the cotyledon petiole samples across the following stages: CK_S1 (preculture), CK_S2 (mock co-culture), CDF1_S2 (co-culture after 3 d), CK_S3 (mock callus induction), and CDF1_S3 (callus induction after 6 d). Color intensity (blue to red) represents the FPKM level. (b)–(g) The relative expression levels of six randomly selected genes from the transcriptome. * represents p < 0.05, indicating a significant difference; ** represents p < 0.01, suggesting a highly significant difference; *** represents p < 0.001, demonstrating a very highly significant difference; and **** represents p < 0.0001, showing an extremely significant difference. Data represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates (n = 3).

-

This study focused on the Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of non-heading Chinese cabbage. Through an in-depth analysis of the transcriptomes of different samples, we revealed the functions of DEGs and changes in related metabolic pathways. These findings provide important insights for the genetic improvement of non-heading Chinese cabbage. Additionally, by integrating the research progress of defensin-like proteins (DEFL), we further deepened our understanding of the interaction mechanism between plants and Agrobacterium.

Impact of Agrobacterium infection on photosynthesis and related metabolism

-

In this study, both GO functional enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway analysis indicated that Agrobacterium infection significantly altered the gene expression related to photosynthesis in non-heading Chinese cabbage[27,30]. At the cellular component level, changes in the expression of genes related to thylakoids and chloroplasts affected the normal functions and development of photosynthetic organelles[27,30]. The KEGG pathway analysis showed that changes in the expression of genes in photosynthesis-related pathways directly affected the efficiency of light-energy capture and conversion, thereby influencing the growth and development of plants[21]. These results are consistent with previous studies on tobacco, potato, and wheat embryos[21,27,30,31]. Agrobacterium infection may disrupt the structure and function of chloroplasts, affecting the activity of photosynthesis-related enzymes or the electron transport process, leading to a decrease in the efficiency of light energy capture and conversion[27,30]. Plants may regulate the expression of photosynthesis-related genes to cope with stress, but this has a cascading effect on their growth and development.

Activation of plant defense responses and immune mechanisms

-

The GO biological process analysis and KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated that when non-heading Chinese cabbage was infected by Agrobacterium, defense-related genes were significantly enriched, and genes in the plant-pathogen interaction pathway were differentially expressed[32]. Plants resist the invasion of Agrobacterium by upregulating the expression of defense-related genes, which is a typical strategy for plants to cope with biotic stress[32]. Meanwhile, the plant MAPK signaling pathway and the plant hormone signal transduction pathway were also significantly affected, and they synergistically regulate the plant's immune response and growth and development processes[33]. Previous studies have shown that the MAPK signaling pathway can activate transcription factors, regulate the expression of downstream defense genes, and enhance the plant's immune ability; the plant hormone signal transduction pathway affects the balance of plants' growth and development and immune responses by regulating hormone levels and signal transduction[33]. In addition, effector proteins secreted by Agrobacterium may inhibit plants' immunity, similar to the mechanism by which the Cytospora chrysosperma effector CcCAP1 inhibits plant immunity[34].

Alterations in metabolic pathways and plant stress adaptation

-

The KEGG pathway analysis revealed that Agrobacterium infection led to significant changes in the primary and secondary metabolic pathways of non-heading Chinese cabbage[35]. Changes in primary metabolic pathways such as carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism affected the balance of cellular energy supply and material synthesis. The activation of secondary metabolic pathways such as secondary metabolite biosynthesis and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathways enabled plants to produce more secondary metabolites to cope with stress. At the same time, Agrobacterium may also utilize the plant's metabolic system to meet its own survival and reproduction needs[35]. Plants adjust their metabolic processes to adapt to the stress imposed by Agrobacterium infection and maintain growth and survival. For example, increasing the synthesis of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids and terpenoids helps plants resist the invasion of Agrobacterium. Adjusting the metabolic pathways of carbohydrates and amino acids provides energy and materials for defense responses and growth and development[35]. This is consistent with the view in previous studies that plants adjust their metabolic pathways to adapt to stress when infected by pathogens[35].

Potential roles of callus-specific genes

-

By comparing the transcriptomes of leaves and callus, callus-specific DEGs were identified. The expression levels of these genes in the petioles were significantly higher than those in leaves, and they increased as the callus expanded, suggesting that they may be crucial for improving the infection efficiency of Agrobacterium[36]. This provides potential targets for optimizing the genetic transformation system of non-heading Chinese cabbage. These genes may be involved in the formation and development of the callus and the response to Agrobacterium infection. For example, they may regulate cell division and differentiation to promote callus formation, or enhance the sensitivity or tolerance of plants to Agrobacterium, thereby improving the infection efficiency[36]. Similar findings of the important impact of tissue-specific genes on the infection process have also been reported in other plant studies. Callus-specific genes in non-heading Chinese cabbage may similarly participate in the key steps of Agrobacterium infection and transformation[37,38].

Potential roles of DEFL in the interaction between non-heading Chinese cabbage and Agrobacterium

-

Owing to the evolutionary conservation of the DEFL family in plant-microbe interactions, and given that DEFL2 exhibits the greatest fold change among the functionally characterized genes within the GO:0006952 (defense response) ontology, it constitutes a tractable molecular entry point for mechanistic dissection. According to current research on DEFL, it plays important roles in plants' defense and growth and development[39−41]. During the Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of non-heading Chinese cabbage, DEFL may be involved in the plant's defense response against Agrobacterium. When infected by Agrobacterium, the expression of DEFL genes may be upregulated. DEFL proteins can inhibit the growth of Agrobacterium by disrupting its cell membrane structure or interfering with its metabolic processes[40]. Meanwhile, DEFL may be involved in the plant's immune signaling pathway, interacting with hormone signaling pathways, such as the jasmonic acid and salicylic acid signaling pathways, to synergistically regulate the plant's immune response to Agrobacterium[42]. PbrDEFL38 is specifically expressed during the pollen tube elongation phase and is secreted into the apoplast, where it contributes to immune defense and cell-wall remodeling. We therefore hypothesise that this non-heading Chinese cabbage ortholog promotes callus formation after Agrobacterium infection through a similar molecular mechanism[43]. In addition, DEFL may also be involved in the regulation of the growth and development of non-heading Chinese cabbage, affecting the formation and development of the callus, and thus influencing the infection efficiency of Agrobacterium[39]. However, the specific mechanism of the role of DEFL in the interaction between non-heading Chinese cabbage and Agrobacterium still needs further study.

Comprehensive impacts of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and future perspectives

-

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation has great potential in the genetic improvement of non-heading Chinese cabbage, but there are also some issues[44]. The integration of exogenous DNA may cause genomic disruption, affecting transformation efficiency, plants' growth and development, trait performance, and stability[44]. Therefore, when optimizing the genetic transformation system, it is necessary to fully consider the impact on the genome, and use appropriate techniques to monitor and evaluate these changes to ensure the quality and stability of transformed plants. In the future, further research can delve deeper into the complex relationships among Agrobacterium infection, plant photosynthesis, metabolic pathways, and immune responses; clarify the functions and mechanisms of key factors such as callus-specific genes and DEFL; and provide a more solid theoretical basis and technical support for improving the genetic transformation efficiency of non-heading Chinese cabbage and breeding excellent varieties.

-

This study revealed the impacts of Agrobacterium infection on plant photosynthesis, metabolic pathways, and defense responses in the Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of non-heading Chinese cabbage, identified callus-specific genes, and explored the potential roles of DEFL in this process. These findings provide an important basis for understanding the interaction mechanism between non-heading Chinese cabbage and Agrobacterium, and lay the foundation for optimizing the genetic transformation system of non-heading Chinese cabbage and breeding excellent varieties. However, many issues remain to be further investigated, such as verifying the gene functions, the regulatory mechanisms of signaling pathways, and the impacts of genomic changes. Future research should focus on these aspects to further promote the development of research into the genetic improvement of non-heading Chinese cabbage.

This research was funded by the Sanya City Science and Technology Innovation Special Project (2022KJCX80), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372698, 32072575), the Jiangsu Province Agricultural Science and Technology Self-innovation Fund [CX(23)3023], and the Jiangsu Province Graduate Research Innovation Program (KYCX22_0752), supported by the Bioinformatics Center of Nanjing Agricultural University.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhang L, Liu T; data collection: Zhang L; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhang L, Tang M, Zheng Y, Xu X, Qu T; draft manuscript preparation: Zhang L, Liu T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Brassica campestris (syn. Brassica rapa) ssp. chinensis genome: http://tbir.njau.edu.cn/NhCCDbHubs/downloadFile_fileShow.action?download_speciesName=Brassica%20campestris%20(syn.%20Brassica%20rapa)%20ssp.%20chinensis%20(Cultivar%20NHCC001)%20v1.0%20Genome&download_fileType=Genome. Data from two NCBI projects, PRJNA1264010 and PRJNA1264463, were analyzed in this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Statistical data of sequencing for different samples.

- Supplementary Table S2 DEGs of CK_S2 vs CK_S1.

- Supplementary Table S3 DEGs of CDF1_S2 vs CK_S1.

- Supplementary Table S4 Genes of leaf transcriptome.

- Supplementary Table S5 The transcriptome before and after callus growth.

- Supplementary Table S6 Unique genes of CK_S3 vs CK_S2.

- Supplementary Table S7 DEGs of CK_S3 vs CK_S2.

- Supplementary Table S8 Primers used in this article.

- Supplementary Table S9 FPKM of genes of GO:0006952(defense response) in CDF1_S2/CK_S2 set.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Cellular component (CC) category of GO functional enrichment analysis for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Molecular function (MF) category of GO functional enrichment analysis for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Biological process (BP) category of GO functional enrichment analysis for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the CDF1_S2/CK_S1 set.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 GO enrichment bar plot for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the CDF1_S2/CK_S2 set.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 GO enrichment pie chart for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the CDF1_S2/CK_S2 set.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang L, Tang M, Zheng Y, Xu X, Qu T, et al. 2025. Analysis of gene expression changes and key factor functions in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation in Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis. Vegetable Research 5: e039 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0031

Analysis of gene expression changes and key factor functions in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation in Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis

- Received: 20 March 2025

- Revised: 25 July 2025

- Accepted: 07 August 2025

- Published online: 30 October 2025

Abstract: This study focused on the Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of non-heading Chinese cabbage. Through transcriptome analysis, the functions of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) after Agrobacterium infection, changes in related metabolic pathways, and the potential roles of defensin-like protein 2 (DEFL2) and callus-specific genes were revealed. Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses showed that Agrobacterium infection affected the expression of genes related to photosynthesis, metabolic pathways, plant-pathogen interactions, and signal transduction in non-heading Chinese cabbage. Alterations in photosynthesis-related gene expression influenced the efficiency of light energy capture and conversion. Changes in metabolic pathways were involved in energy supply, material synthesis, and secondary metabolite production. The plant activated defense responses to resist Agrobacterium invasion. Callus-specific genes might improve the infection efficiency of Agrobacterium, and DEFL2 might play important roles in plant defense and growth and development, although the specific mechanisms remain to be further investigated. This study provides a theoretical basis for the genetic improvement of non-heading Chinese cabbage and contributes to optimizing its genetic transformation system. However, in-depth research is still needed in aspects such as gene function verification, the regulatory mechanisms of signaling pathways, and the impacts of genomic changes.