-

Compared with traditional wired charging, WPT technology has the advantages of safety, aesthetics, and flexibility[1]. This promising technology has been applied in various industrial fields[2,3]. Li-ion batteries are extensively employed in the above fields due to their advantages of environmental friendliness, high power density and long lifespan. Lithium batteries are lightweight and environmentally friendly, they are often used by some electrical equipment to store electrical energy. The charging sequence of first constant current (CC) charging and then constant voltage (CV) charging is the charging method that best suits the charging characteristics of lithium batteries. The existing traditional methods that enable WPT systems to achieve stable CC and CV output and their related defects are as follows:

The three closed-loop control methods of phase shift control[4,5], frequency conversion control[6,7] and DC-DC converter control[8,9] are currently commonly used technologies to realize CC and CV outputs. However, all three methods have disadvantages. Phase shift control is difficult to achieve zero-voltage switching and approximate zero-phase-angle (ZPA) operation when the load changes greatly, resulting in increased inverter loss. Frequency conversion control technology has the possibility of frequency bifurcation, which will seriously affect the stability of the system. At the same time, this technology is also difficult to achieve ZPA operation, which will cause reactive power circulation in the system and increase losses. DC-DC converter control technology has a large number of components, high cost, and high system complexity.

The hybrid topology switching method realizes the conversion of the system's CC and CV outputs by controlling the on-off of the switches[10−13]. However, it introduces additional AC switches, corresponding drive circuits, and passive components in the system, which increases the complexity of the circuit structure.

The dual-frequency switching method is also a commonly used method to realize CC and CV outputs[14−18]. However, this method is not only difficult to design the parameters of the compensation components, but also difficult to limit the CC and CV frequencies within the frequency range specified by the standard.

To optimize the existing CC and CV WPT systems, this paper proposes an LCC-LCC compensated WPT system, which can not only realize CC and CV outputs but also automatically complete the transition from CC to CV mode. Compared with the previous closed-loop control, hybrid topology switching, and dual-frequency switching methods, the proposed method does not require communication links, state-of-charge detection circuits, and open-circuit protection circuits. Meanwhile, the system works at a fixed frequency throughout the entire working process to ensure system stability. In addition, the system can achieve ZPA operation in CC mode and CV mode, improving the efficiency of the system. Therefore, simple structure high reliability, and low cost can be ensured in the proposed system. It is worth noting that, similar to the above-mentioned hybrid topology switching method and dual-frequency switching method, the proposed method is suitable for scenarios with fixed mutual inductance, such as electric bicycle charging applications.

-

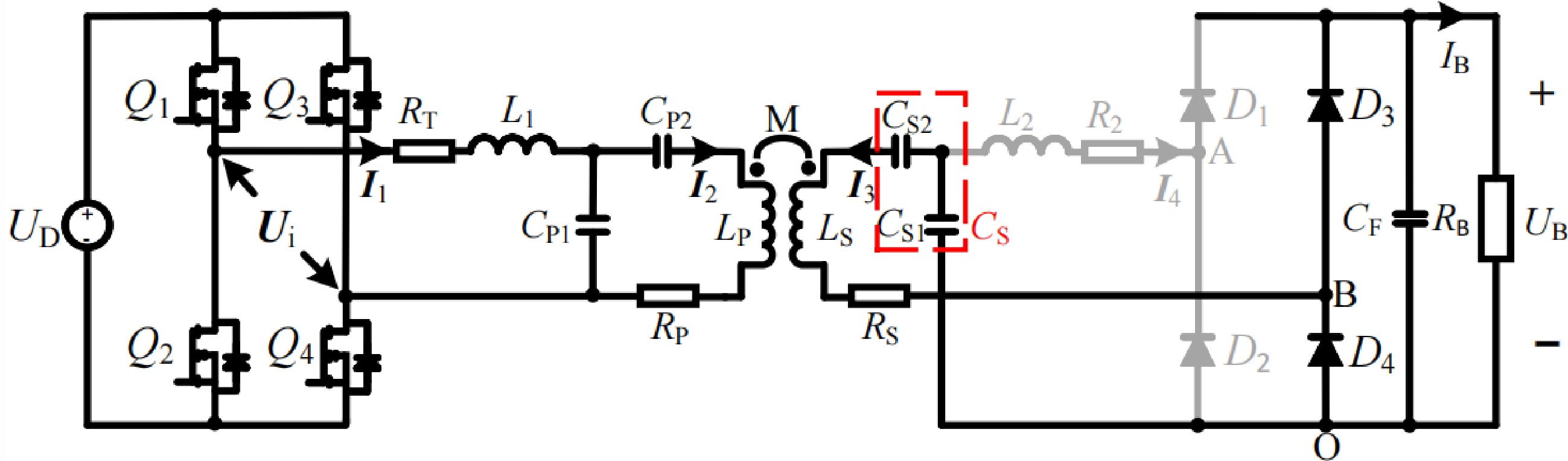

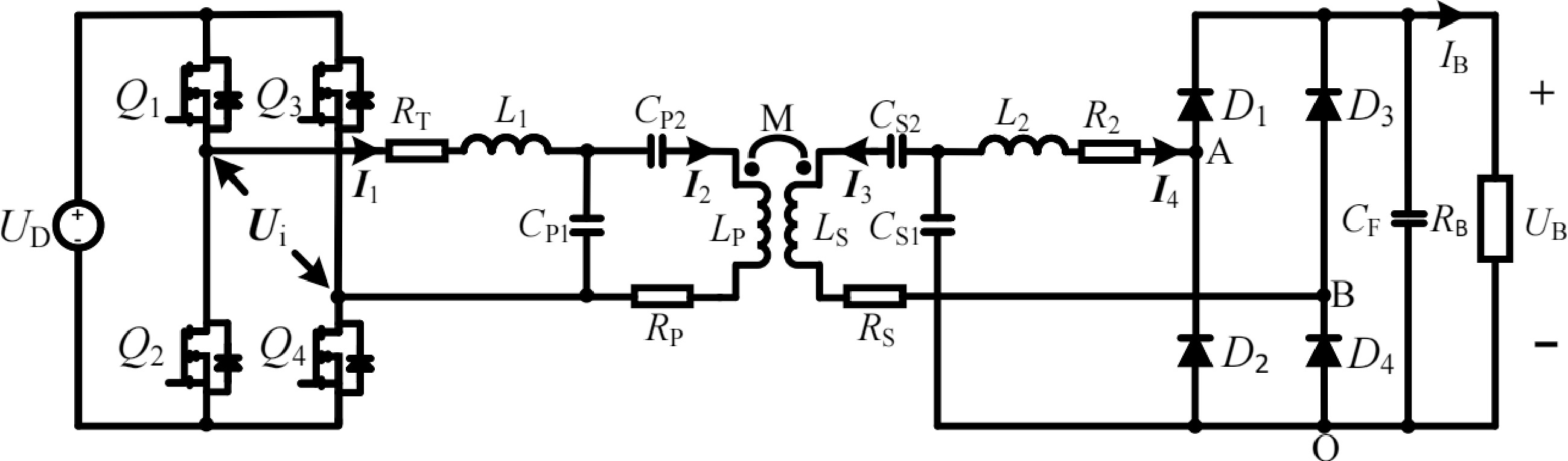

The overall circuit configuration of the proposed LCC-LCC compensated WPT system with inherent CC and CV characteristics and automatic CC-CV transition function is shown in Fig. 1, which is also the circuit configuration of CC charging. UD is the DC input voltage. The inverter comprised of four MOSFETs (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4) is applied to supply the LCC-LCC resonant tank. LP, LS, and M stand for the self-inductances of transceiver-side coils and the corresponding mutual inductance. L1, CP1, and CP2 are the compensation inductance and capacitances on the transmitter. The special receiver-side LCC resonant tank composed of the compensation inductance L2, compensation capacitances CS1 and CS2 are utilized to obtain the automatic CC-CV transition function. RT, RP, RS, and R2 stand for the corresponding parasitic resistances of L1, LP, LS, and L2, respectively. In the initial stage of charging, the CC mode is performed, the proposed system operates in the LCC-LCC resonant tank with inherent CC characteristics, as shown in Fig. 1. As charging progresses, the battery voltage continuously increases. At the CC-CV transition point, the battery voltage is just higher than the voltage across CS1, diodes D1 and D2 are forced to reverse bias. Then, the proposed system automatically converts to LCC-S resonant tank with inherent CV characteristics. The associated circuit configuration of the proposed system for CV charging is depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

Overall circuit configuration of proposed WPT system and circuit configuration of the LCC-LCC compensated WPT system for CC charging.

Analysis of CV mode

-

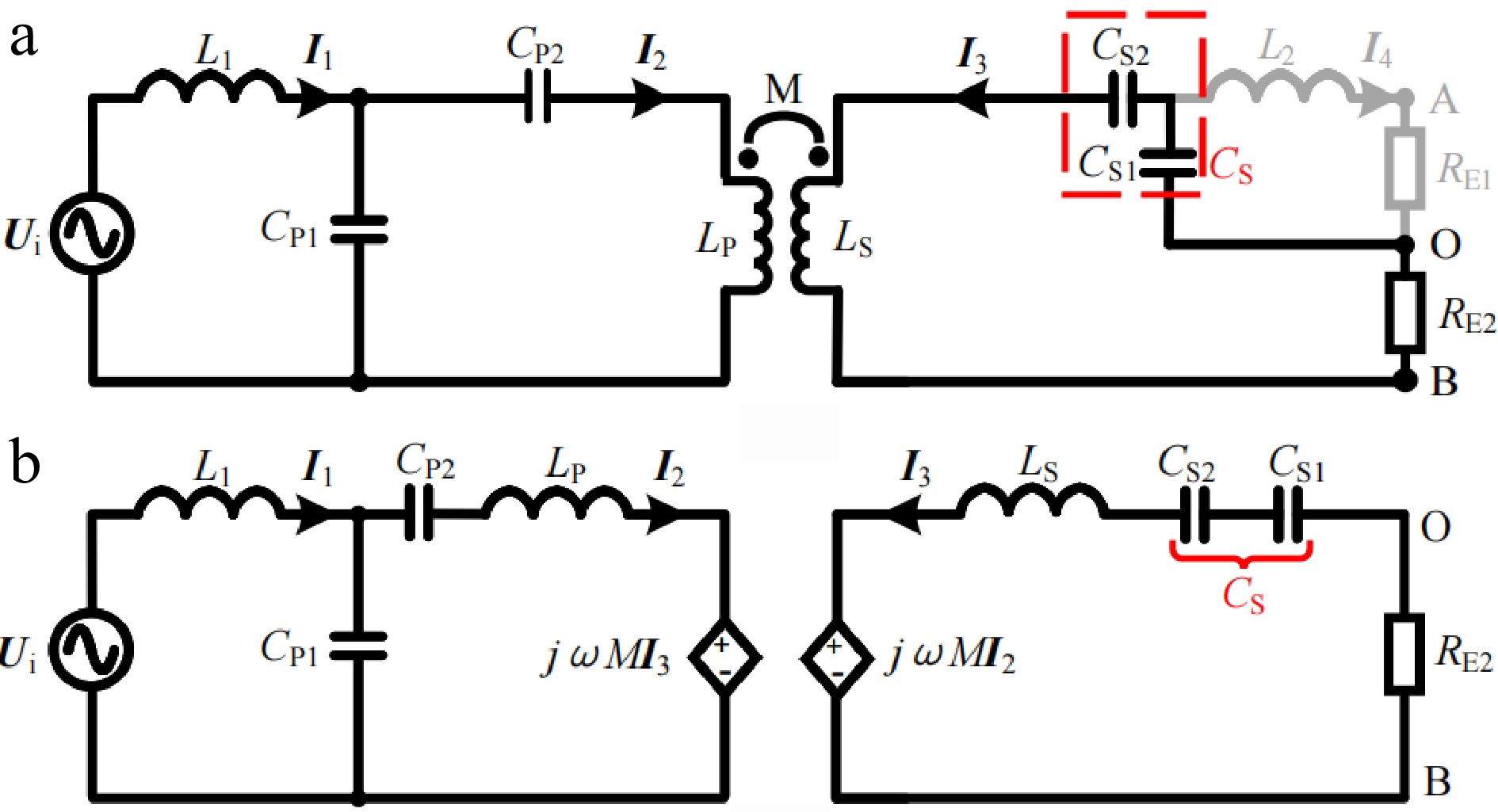

In CV mode, since the battery voltage is higher than the voltage across CS1, diodes D1 and D2 are forced to reverse bias, breaking the branch where L2 is located. The proposed system operates in LCC-S topology to perform CV charging, as shown in Fig. 2. The corresponding simplified circuit diagram and equivalent circuit diagram are shown in Fig. 3a & b, respectively. According to Kirchhoff’s voltage law (KVL), Eqn (1) can be obtained.

Figure 3.

Simplified circuit diagram and equivalent circuit diagram in CV mode. (a) Simplified circuit diagram. (b) Equivalent circuit diagram.

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{U_i} = \left(j\omega {L_1} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{P1}}}}\right){I_1} - \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{P1}}}}{I_2}} \\ {0 = \left(j\omega {L_P} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{P1}}}} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{P2}}}}\right){I_2} - \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{P1}}}}{I_1} + j\omega M{I_3}} \\ {0 = \left(j\omega {L_S} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_S}}} + {R_{E2}}\right){I_3} + j\omega M{I_2}} \end{array}} \right. $ (1) To simplify the analysis, the LCC-S topology should satisfy the following resonance conditions.

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {j\omega {L_{\text{1}}} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{{\text{P1}}}}}} = 0,j\omega {L_{\text{P}}} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{{\text{P1}}}}}} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{{\text{P2}}}}}} = 0} \\ {j\omega {L_{\text{S}}} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{\text{S}}}}} = 0,\dfrac{1}{{{C_{\text{S}}}}} = \dfrac{1}{{{C_{{\text{S1}}}}}} + \dfrac{1}{{{C_{{\text{S2}}}}}}} \end{array}} \right. $ (2) Substituting Eqn (2) into Eqn (1), Eqn (3) can be obtained.

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{I_1} = \dfrac{{{M^2}{U_i}}}{{L_1^2{R_{E2}}}}} \\ {{U_{BO}} = {I_3}{R_{E2}} = - \dfrac{{M{U_i}}}{{{L_1}}}} \\ {{Z_{in}} = \dfrac{{{U_i}}}{{{I_1}}} = \dfrac{{L_1^2{R_{E2}}}}{{{M^2}}}} \end{array}} \right. $ (3) Combining Eqn(3) and

$ {U_{BO}} = ({{\sqrt 2 }/\pi }){U_B} $ $ {U_{\text{B}}} = \dfrac{{\pi M{U_{\text{i}}}}}{{\sqrt 2 {L_1}}} $ (4) where, Ui is the root mean square (RMS) value of Ui. Combining Eqn (4) and

$ {U_{\text{i}}} = (2\sqrt 2 /\pi ){U_{\text{D}}} $ $ {U_{\text{B}}} = \dfrac{{2M{U_{\text{D}}}}}{{{L_1}}} $ (5) Observing Eqns (3) & (5), the input impedance Zin is purely resistive and the charging voltage UB is irrelevant to the load resistance. Therefore, the system can realize load-independent CV charging and ZPA operation. In addition, the voltage gain can be adjusted by changing the parameter of the compensation inductor L1 to match the actual application requirements.

Analysis of CC mode

-

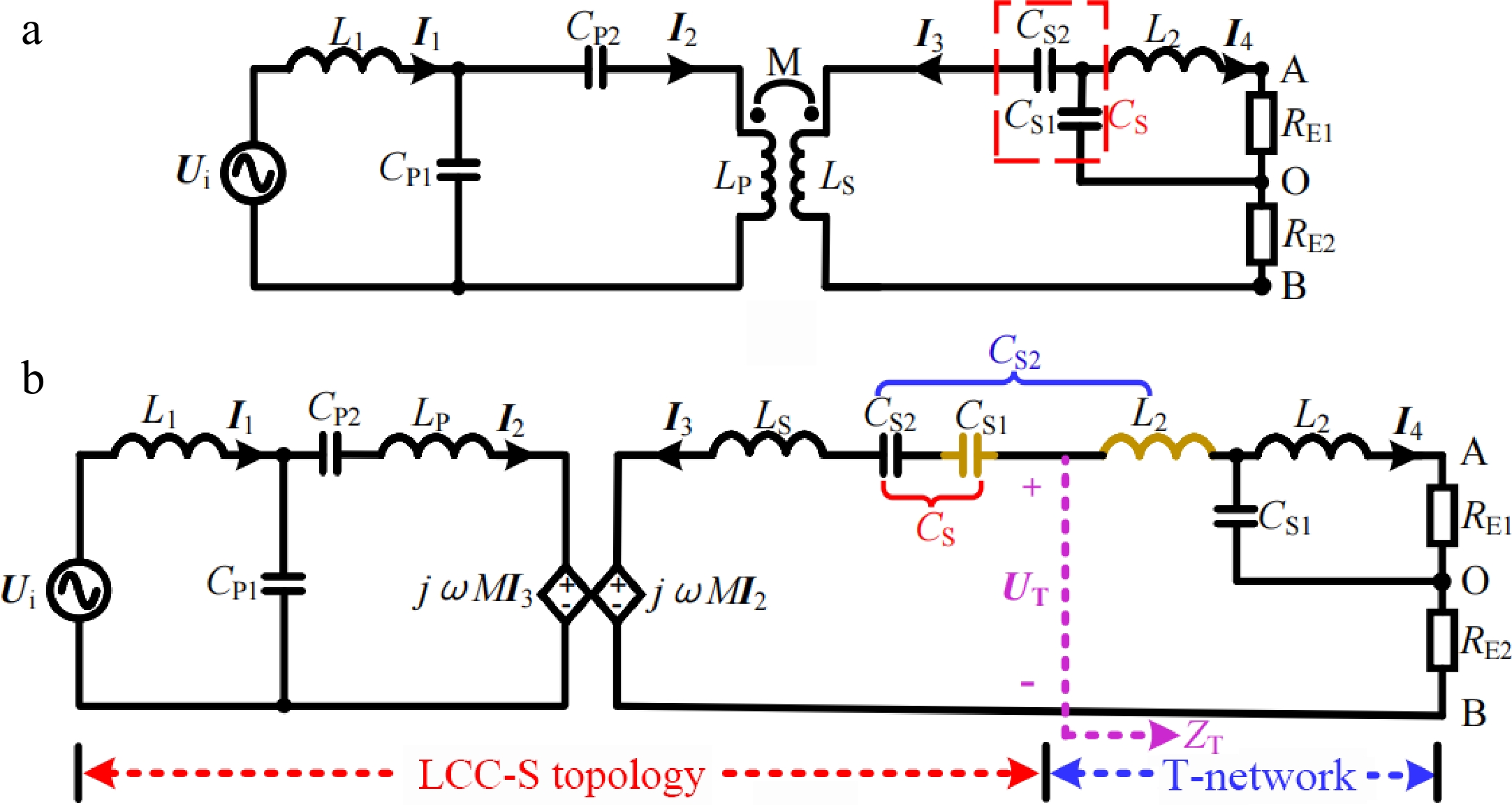

Due to the special circuit structure on the receiver, diodes D1 and D2 form one half-bridge rectifier, while diodes D3 and D4 form another half-bridge rectifier. Observing Fig. 1, the two half-bridge rectifiers have the same output terminals to power the load. Therefore, the two half-bridge rectifiers are connected in parallel. In CC mode, both the half-bridge rectifiers are activated. For the half-bridge rectifier composed of D1 and D2, the relationship between the RMS value of the input voltage

$ {U_{{\text{AO}}}} $ $ {U_{\text{B}}} $ $ {U_{{\text{AO}}}} = (\sqrt 2 /\pi ){U_{\text{B}}} $ $ {U_{{\text{BO}}}} $ $ {U_{\text{B}}} $ $ {U_{{\text{BO}}}} = (\sqrt 2 /\pi ){U_{\text{B}}} $ $ {U_{{\text{AO}}}} = {U_{{\text{BO}}}} $ $ \dfrac{1}{{{R_{{\text{E}}1}}}} + \dfrac{1}{{{R_{{\text{E2}}}}}} = \dfrac{{{\pi ^2}}}{{2{R_{\text{B}}}}} $ (6) To make the CC analysis process easier to understand, the corresponding equivalent circuit diagram is provided, as shown in Fig. 4b. Assuming that CS1 and L2 represented in gold satisfy the resonance condition

$ j\omega {L_{\text{2}}} + 1/j\omega {C_{{\text{S1}}}} = 0 $

Figure 4.

Simplified circuit diagram and equivalent circuit diagram in CC mode. (a) Simplified circuit diagram. (b) Equivalent circuit diagram.

Based on the analysis of the LCC-S topology for CV charging in section Analysis of CV mode, the following Eqn (7) can be concluded:

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{U_T} = - {U_{ BO}} = \dfrac{{M{U_i}}}{{{L_1}}}{\text{ }}} \\ {{Z_{in}} = \dfrac{{L_1^2{Z_T}}}{{{M^2}}}{\text{ }}} \end{array}} \right. $ (7) Then, the special T-network in Fig. 4b is analyzed. According to KVL, Eqn (8) can be obtained:

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {0 = {U_{\text{T}}} + (j\omega {L_{\text{2}}} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{{\text{S1}}}}}} + {R_{{\text{E2}}}}){I_3} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{{\text{S1}}}}}}{I_{\text{4}}}{\text{ }}} \\ {0 = (j\omega {L_{\text{2}}} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{{\text{S1}}}}}} + {R_{\text{E}}}_{\text{1}}){I_4} + \dfrac{1}{{j\omega {C_{{\text{S1}}}}}}{I_3}{\text{ }}} \end{array}} \right. $ (8) Combining

$ {U_{ {\text{AO}}}} = {U_{{\text{BO}}}} $ $ j\omega {L_{\text{2}}} + 1/j\omega {C_{{\text{S1}}}} = 0 $ $ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{I_3} = - \dfrac{{2{R_{\text{B}}}{U_{\text{T}}}}}{{{\pi ^2}{\omega ^2}L_{\text{2}}^{\text{2}}}}{\text{ }}} \\ {{I_4} = - \dfrac{{j(\omega {L_{\text{2}}}{\pi ^2} - 2{R_{\text{B}}}){U_{\text{T}}}}}{{{\pi ^2}{\omega ^2}L_{\text{2}}^{\text{2}}}}{\text{ }}} \\ {{Z_{\text{T}}} = \dfrac{{{U_{\text{T}}}}}{{ - {I_3}}} = \dfrac{{{\pi ^2}{\omega ^2}L_{\text{2}}^{\text{2}}}}{{2{R_{\text{B}}}}}{\text{ }}} \end{array}} \right. $ (9) From Eqn (9), the equivalent output current IO of the special T-network, which is also the RMS value of the two half-bridge rectifiers’ equivalent input current, can be deduced as:

$ {I_{\text{O}}} = {I_{\text{4}}} + {I_3} = \dfrac{{{U_{\text{T}}}}}{{\omega {L_{\text{2}}}}} $ (10) According to Eqn (10), it can be concluded that a CV source can be transformed into a CC source through the special T-network shown in Fig. 4b. Further, combining Eqns (7), (9), (10) and

$ {U_{\text{i}}} = (2\sqrt 2 /\pi ){U_{\text{D}}} $ $ \left\{ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {I_B} = \dfrac{{\sqrt 2 }}{\pi }{I_O} = \dfrac{{4M{U_D}}}{{{\pi ^2}\omega {L_1}{L_2}}} \\ {Z_{in}}{\text{ }} = {\text{ }}\dfrac{{{\pi ^2}{\omega ^2}{L_1}^2{L_2}^2}}{{2{M^2}{R_B}}} \end{array} \right. $ (11) As evident from Eqn (11), the input impedance Zin is purely resistive and the charging current IB is irrelevant to the load resistance. Therefore, the system can achieve load-independent CC charging and ZPA operation. In addition, the transconductance gain can be adjusted by changing the parameters of compensation inductors L1 and L2 to match the actual application requirements.

-

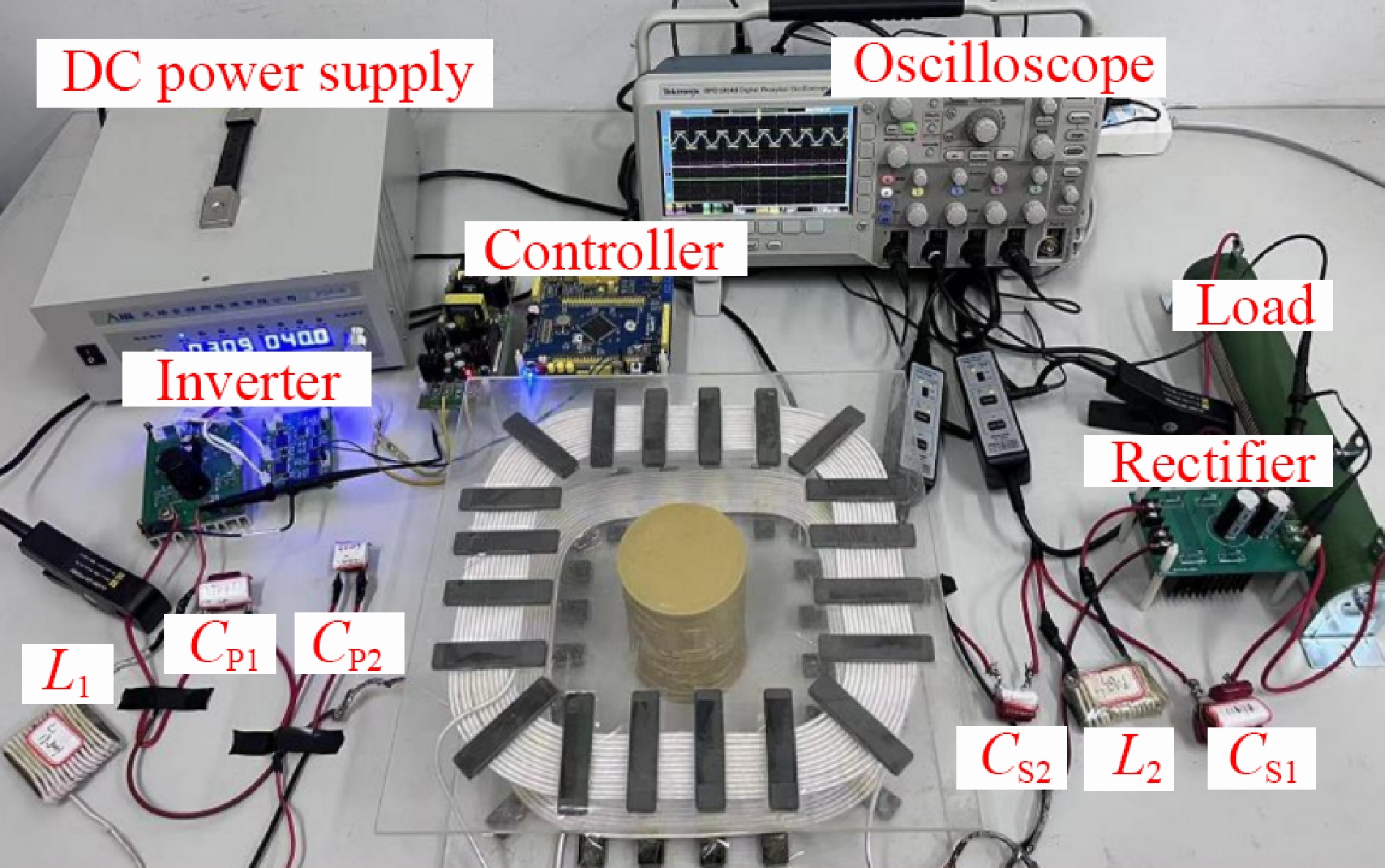

To verify the practicability of the proposed method, an experimental prototype is fabricated, as shown in Fig. 5. Given an electric bicycle on-board battery pack with nominal voltage of 72 V and capacity of 20 Ah, the required charging current IB in CC mode and charging voltage UB in CV mode can be set to 3.2 A and 80 V, respectively. Four MOSFET (IRF530) are selected to form the inverter, and four diodes (MBR16100CT) are chosen to construct the rectifier. The feasibility of adopting a resistive load to replace the battery has been experimentally demonstrated in detail in a study by Chen et al.[19]. Thus, this study utilizes the resistive load to conduct experimental testing. The operating frequency f is set to 85 kHz. A DC input voltage UD of 40 V is applied to supply the system. Subsequently, through the above theoretical analysis, the parameters of each compensation component can be set reasonably by Eqns (2), (5), (11) and

$ j\omega {L_{\text{2}}} + 1/j\omega {C_{{\text{S1}}}} = 0 $ Table 1. Specific circuit parameters of the proposed LCC-LCC compensated WPT system.

Parameters Value Parameters Value Parameters Value UD 40 V LP 100.3 uH CP1 175.4 nF UB 80 V LS 100.1 uH CP2 34.9 nF IB 3.2 A L1 19.8 uH CS1 365.2 nF f 85 kHz L2 9.6 uH CS2 38.8 nF M 20.4 uH RP 0.12 Ω RS 0.1 Ω Experimental results

-

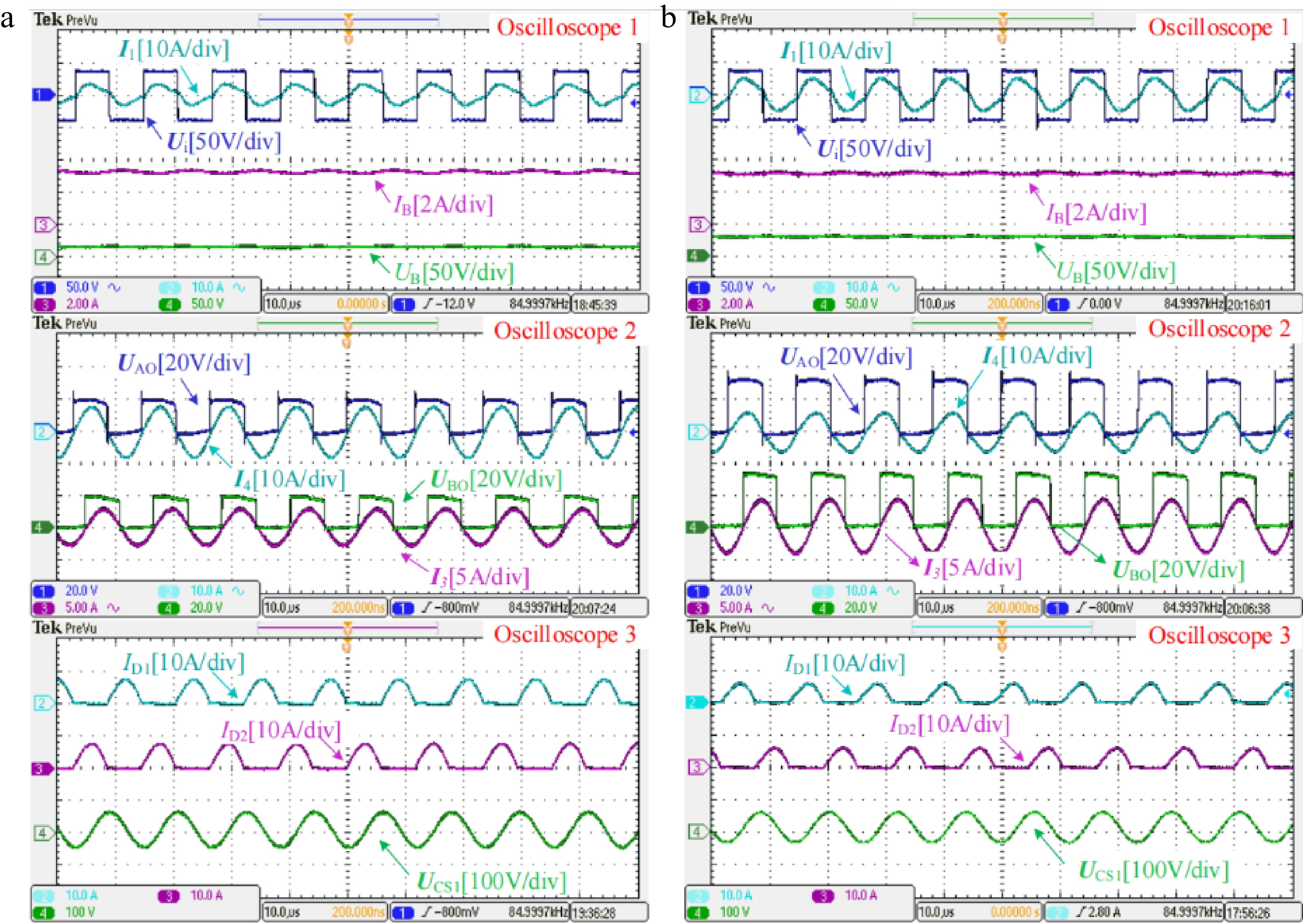

In the initial stage of charging, the proposed system performs the CC charging with an LCC-LCC resonant tank. The measured experimental waveforms in CC mode when the battery equivalent resistance RB is about 5 and 10 Ω are shown in Fig. 6a & b, respectively. Observing the two figures marked with Oscilloscope 1, the charging current IB roughly maintains a constant value of 3.2 A when RB varies, which demonstrates the load-independent CC output characteristic. In addition, Ui and I1 are basically in phase, indicating that the system can achieve ZPA operation in CC mode. Then, from the two figures marked with Oscilloscope 2, the RMS values of the two rectifiers’ input voltages UAO and UBO are equal, which verifies the correctness of the two rectifiers working in parallel in CC mode. In addition, as RB increases, I4 gradually decreases and I3 gradually increases. I3 and I4 are rectified and output in parallel to form a CC source. Furthermore, from the two figures marked with Oscilloscope 3, the battery voltage UB is lower than the peak value of UCS1 (the voltage across CS1) in CC mode. Diodes D1 and D2 are both in the conduction state, forming the current I4.

Figure 6.

Measured experimental waveforms in CC mode when the battery equivalent resistance RB is about (a) 5 Ω and (b) 10 Ω, respectively.

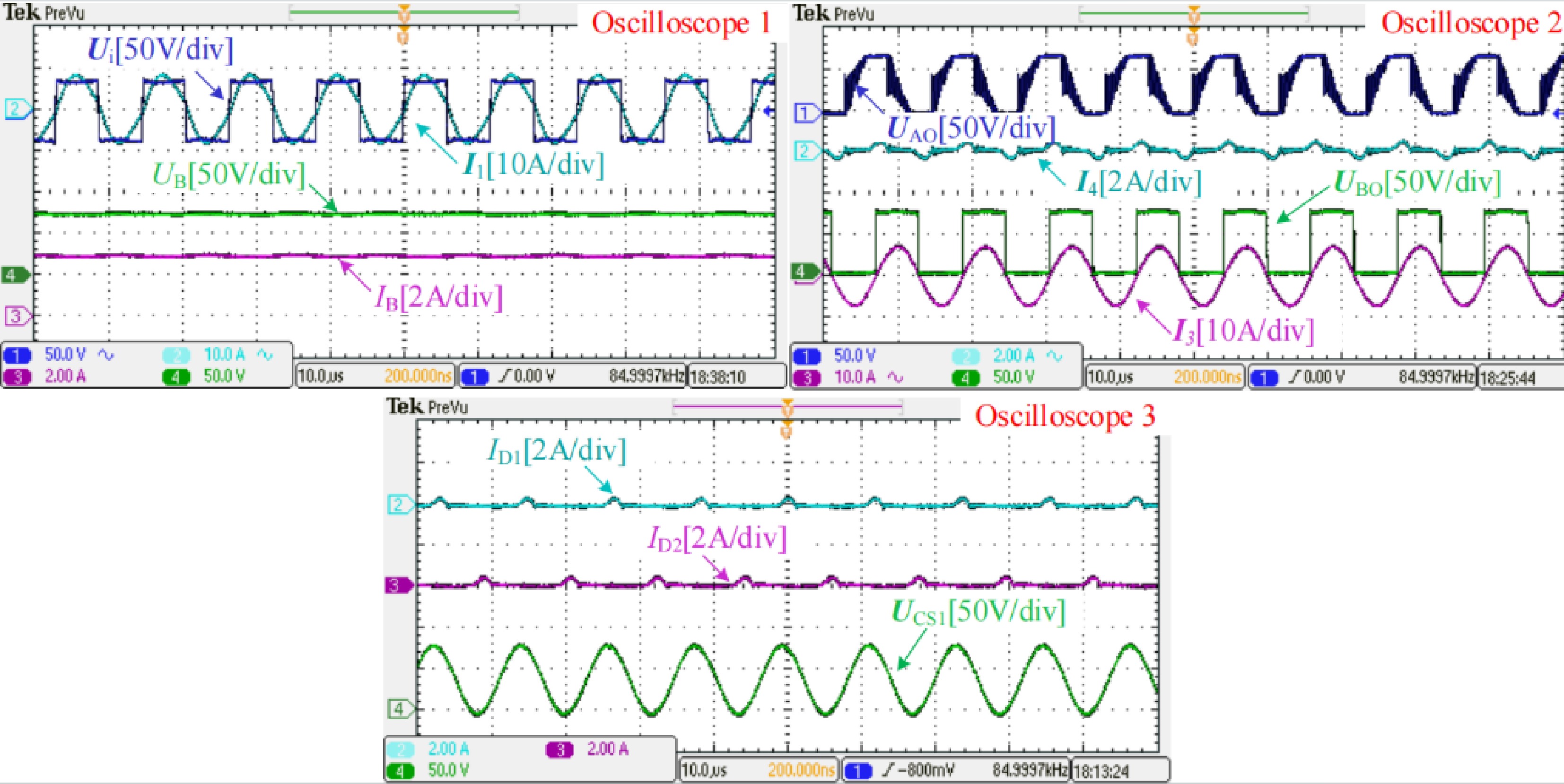

As charging progresses, when UB rises close to the peak value of UCS1, the CC-CV transition is automatically performed. The measured experimental waveforms at the CC-CV transition point when RB is about 25 Ω are shown in Fig. 7. Observing the figure marked with Oscilloscope 1, UB, and IB are slightly lower than preset values and the ZPA operation can be achieved. Then, from the figure marked with Oscilloscope 2, UAO and UBO are approximately equal. I4 is very small, which means the branch where L2 is located is about to be cut off. Furthermore, from the figure marked with Oscilloscope 3, UB is close to the peak value of UCS1, diodes D1, and D2 are both in an extremely weak conduction state, forming the weak current I4, and the system is about to transition from LCC-LCC topology for CC charging to LCC-S topology for CV charging.

Figure 7.

Measured experimental waveforms at the CC-CV transition point when the battery equivalent resistance RB is about 25 Ω.

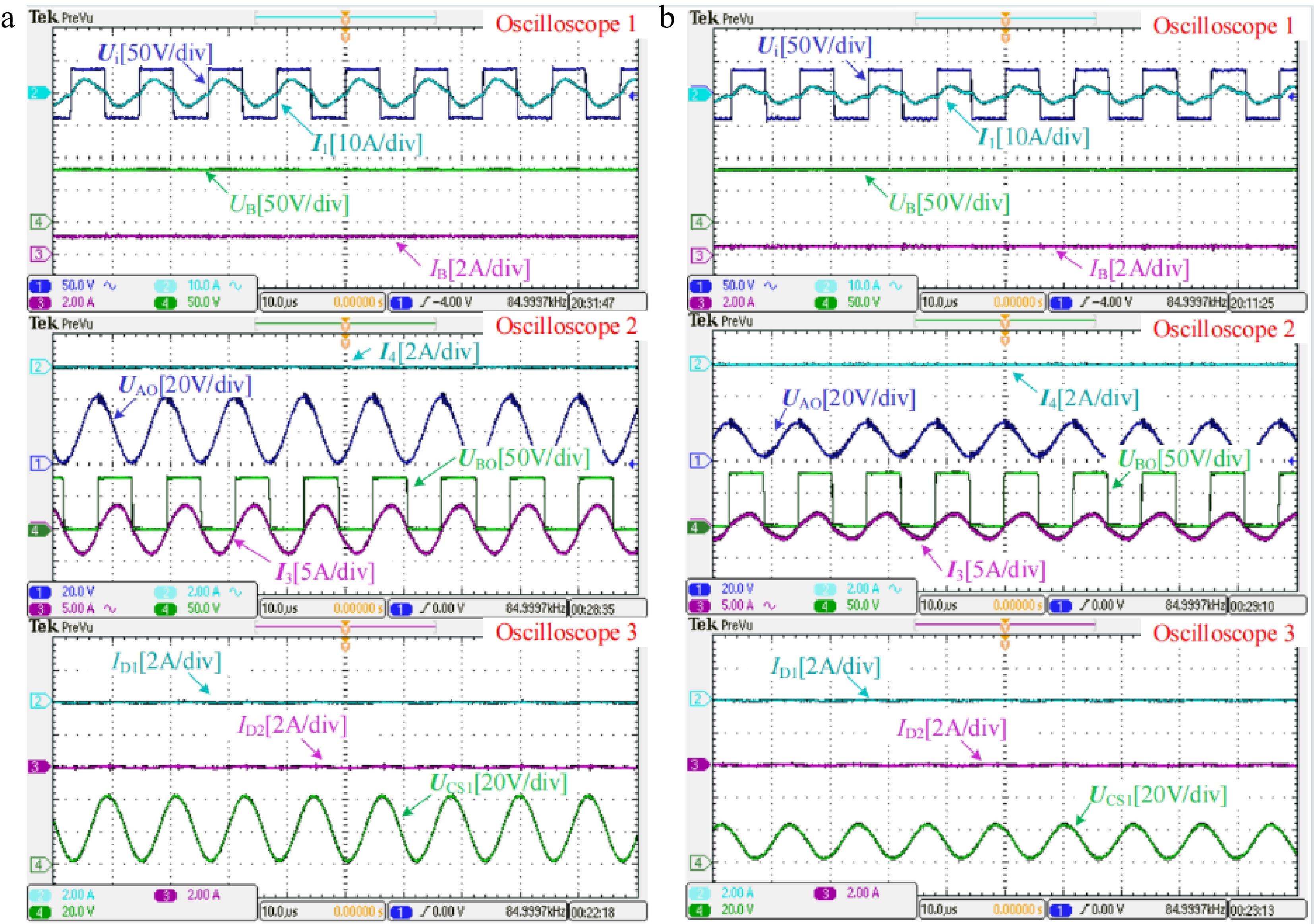

As the battery voltage continues to rise when UB is higher that the peak value of UCS1, diodes D1 and D2 are forced to reverse bias. The branch where L2 is located is completely cut off. Then, the proposed system performs the CV charging with LCC-S resonant tank. The measured experimental waveforms in CV mode when RB is about 70 and 140 Ω are shown in Fig. 8a & b, respectively. Observing the two figures marked with Oscilloscope 1, the charging voltage UB roughly maintains a constant value of 80 V when RB varies, which demonstrates the load-independent CV output characteristic. The phase of I1 is approximately consistent with that of Ui, which indicates that the system can achieve ZPA operation in CV mode. Then, from the two figures marked with Oscilloscope 2, as diodes D1 and D2 are reverse biased to break the branch where L2 is located, the current I4 drops to zero. Only the rectifier composed of D3 and D4 supplies power to the load. In addition, since the branch where L2 is located is cut off, UAO and UCS1 will remain the same, which can be found by comparing the figures marked with Oscilloscopes 2 and 3. Furthermore, from the two figures marked with Oscilloscope 3, the currents flowing through diodes D1 and D2 are both 0, which is consistent with the current I4, verifying that the branch where L2 is located is completely cut off. In addition, as RB increases, the peak value of UCS1 decreases gradually, and the system will operate normally with LCC-S topology for CV charging until the end of charging.

Figure 8.

Measured experimental waveforms in CV mode when the battery equivalent resistance RB is about (a) 70 Ω and (b) 140 Ω, respectively.

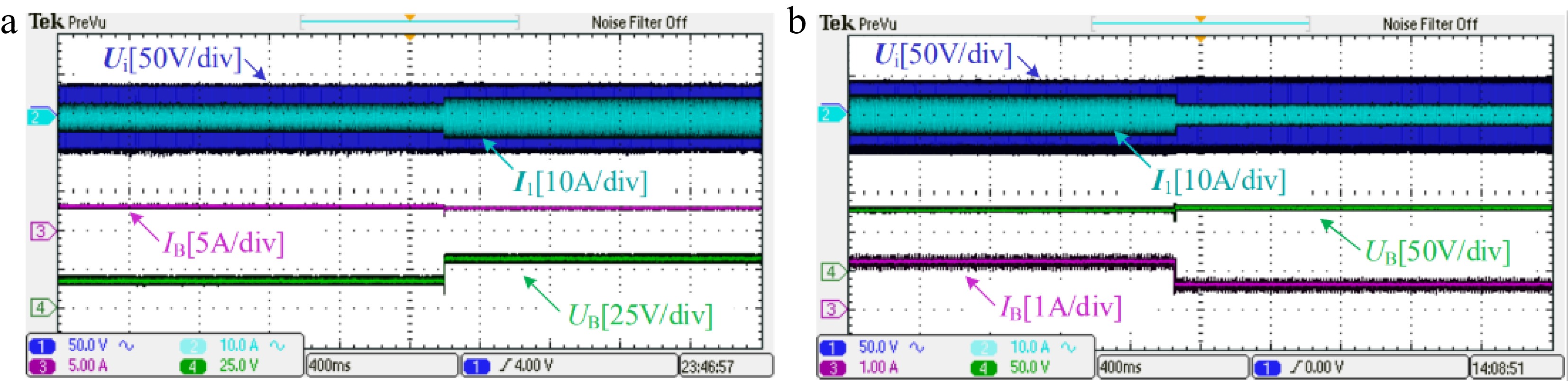

Transient results with RB step changes from 5 to 10 Ω in CC mode and from 70 to 140 Ω in CV mode are tested respectively, as shown in Fig. 9. From Fig. 9, when RB is suddenly increased by 100%, the resulting changes in both charging current IB in CC mode and the charging voltage UB in CV mode are very small. In addition, there is no significant overshoot when RB is changed suddenly in both CC and CV modes. This further validates that the proposed system can perform CC and CV charging stably.

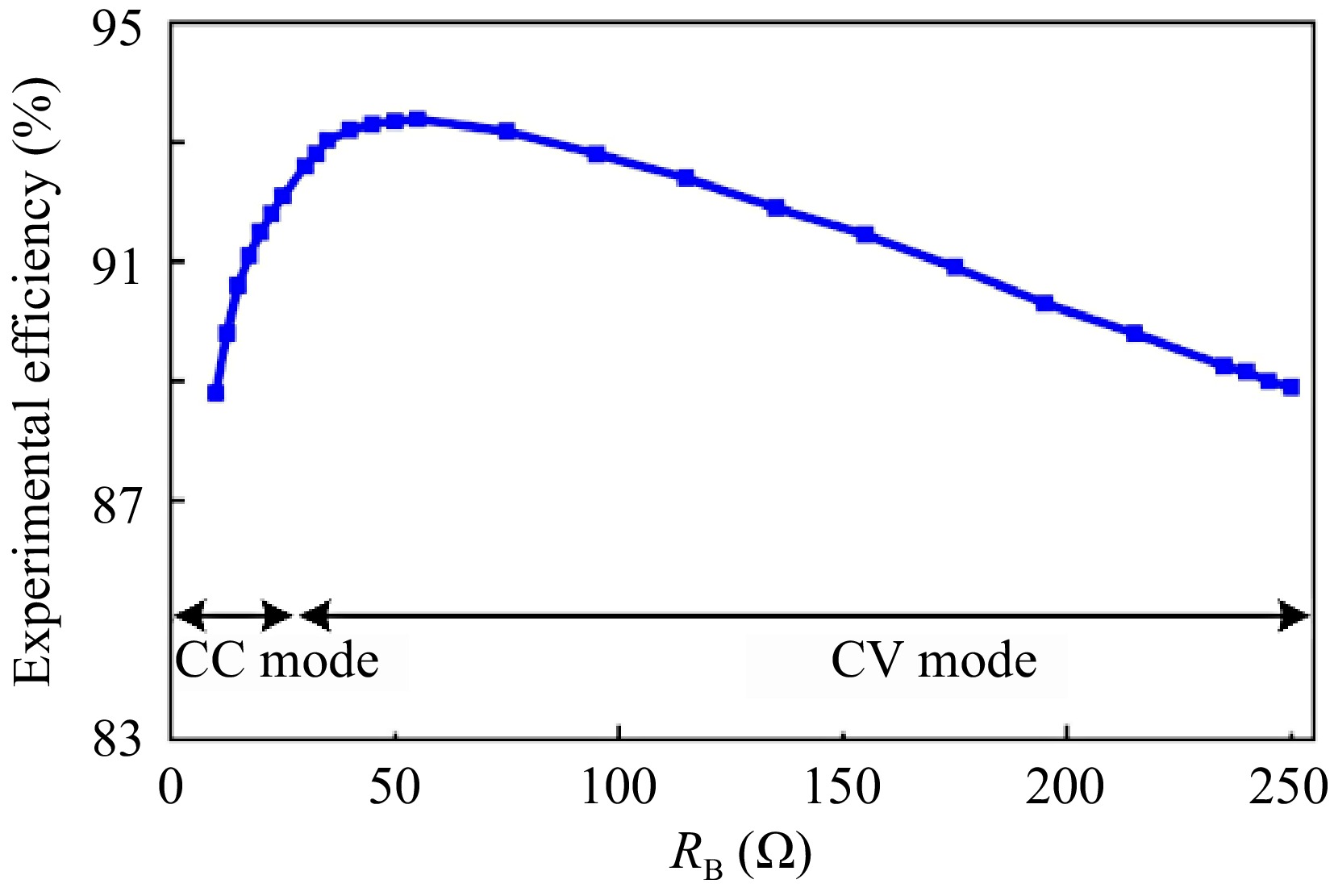

Figure 10 shows the DC-DC efficiency curve of the proposed system during the whole charging process. In CC mode, as RB varies from 10 to 25 Ω, the system efficiency climbs up from 88.8% to 92.1%. In CV mode, as RB varies from 25 to 250 Ω, the system efficiency slowly drops from the peak of 93.38% to 88.9%. The proposed system maintains high efficiency throughout the charging process.

Table 2. System configuration and cost comparison with existing popular methods

Proposed in Ref. [10−13] Ref. [14−18] This study Method Hybrid topology switching Dual-frequency switching Automatic CC-CV transition Without detection circuits No No Yes Without communication links No No Yes Without open-circuit protection circuits No No Yes Without excess components and switches No Yes Yes Cost High Medium Low To reflect the low cost of the proposed system more intuitively, the configuration and cost of the proposed system are compared with currently popular hybrid topology switching and dual-frequency switching methods, as shown in Table 2. Considering hardware requirements such as detection circuits for CC-CV transition, communication links, open-circuit protection circuits, and excess components and AC switches and the corresponding driving circuits, the proposed system performs best from the perspective of cost-effectiveness.

-

In this paper, an LCC-LCC compensated WPT system with inherent CC and CV characteristics and automatic CC-CV transition function are put forward for battery charging applications. CC and CV characteristics under the corresponding circuit configurations are analyzed in detail. The feasibility of the proposed system is proved by building a confirmatory prototype, and high efficiency is maintained throughout the charging process. The features of the proposal can be summarized as follows:

(1) Compared with the closed-loop control methods, the proposed system does not need to introduce complicated control algorithms, which reduces the difficulty of controller design and is easy to implement.

(2) Compared with the hybrid topology switching method, the proposed system does not require additional passive components, AC switches, and corresponding driving circuits, which simplifies the system structure.

(3) Compared with the dual-frequency switching method, the proposed system runs at a fixed frequency, which avoids the frequency bifurcation phenomenon and has high robustness.

(4) In addition, the proposed system can automatically realize the transition from CC to CV mode through its structural properties, without additional detection circuits, communication links, and open-circuit protection circuits, which makes the system simpler and less costly.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhou X; data collection: Wang Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhou X, Yang L; draft manuscript preparation: Zhou X, Wang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

This work was supported in part by the following: Scientific Research Youth Foundation of Hunan Province Education Department of China (22B0803), the Employment and Education Foundation of The Second Phase of The Department of College Students of The Ministry of Education of China (20230106677), the Guiding Science and Technology Programme Foundation of Yongzhou City of China (2022-YZKJZD-010), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2024JJ7186).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou X, Wang Y, Yang L. 2024. An LCC-LCC compensated WPT system with inherent CC-CV transition function for battery charging applications. Wireless Power Transfer 11: e002 doi: 10.48130/wpt-0024-0002

An LCC-LCC compensated WPT system with inherent CC-CV transition function for battery charging applications

- Received: 07 May 2024

- Revised: 11 June 2024

- Accepted: 03 July 2024

- Published online: 24 July 2024

Abstract: To prolong the service life of lithium batteries, the charging process is usually divided into two stages: constant current (CC) charging, and then constant voltage (CV) charging. This paper proposes an LCC-LCC compensated wireless power transfer (WPT) system, which not only has CC and CV charging characteristics but also can realize automatic CC-CV transition, omitting auxiliary circuits such as state-of-charge detection circuit and open circuit protection circuit. The proposed system initially adopts the LCC-LCC structure for CC charging and subsequently adopts the LCC-S structure for CV charging. It is simple in structure, easy to control, and overcomes the shortcomings of traditional methods. Finally, a verification experimental prototype with a rated power of 256 W is built to verify the feasibility of the proposed system.