HTML

-

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF, Glomeromycota) (Wijayawardene et al. 2020) are natural symbionts of a broad range of terrestrial plants (Smith & Read 2008). The origin of these fungi dates from the Early Devonian, 400 million years ago, when they likely played a fundamental role in colonization of the land by plants (Strullu-Derrien & Strullu 2007, Walker et al. 2021).

Plants in natural ecosystems depend mostly on mycorrhizae for the acquisition of nutrients in amounts adequate to sustain regular growth and reproduction (Khade & Rodrigues 2009). They also provide several ecosystem services, such improvement of soil structure (Caravaca et al. 2006, Rillig & Mummey 2006), suppression of weed populations (Rinaudo et al. 2010), and cycling of major elements such as carbon, phosphorus and nitrogen (Fitter et al. 2011).

Until the end of the 20th century, the taxonomy of AMF was based mainly on spore morphology, type of spore formation (acaulosporoid, entrophosporoid, gigasporoid, glomoid, and scutellosporoid) and wall structure (Gerdemann & Trappe 1974, Walker & Sanders 1986, Morton & Benny 1990, Schenck & Pérez 1990). However, many AMF species sporulate seasonally or not at all in the field (Gemma & Koske 1988, Gemma et al. 1989, Błaszkowski et al. 2021) and minimum levels of root colonization are required to induce sporulation, which is regulated by the fungal genotype alone or in combination with host factors (Franke & Morton 1994, Stutz & Morton 1996). These factors can underestimate AMF diversity and limit the understanding of the role of those fungi in ecosystems (Lee et al. 2013). In the last two decades molecular approaches used to identify AMF species from cultures and field samples have been deep progress (Morton & Redecker 2001, Kowalchuk et al. 2002, Rosendahl & Stukenbrock 2004, Mummey & Rillig 2007). Those techniques have been important in the description of new families, genera and species with improvement of phylogenetic relationships (Błaszkowski et al. 2017, 2021). They have also revolutionized ecology studies in AMF communities (Chagnon & Bainard 2015) using new sequencing techniques to identify OTU in different field conditions.

Cuba possesses the highest richness of plants of all the Caribbean islands (CITMA 2014), it is one of the four islands with the highest number of plant species worldwide and it also has the largest number of plant taxa per km2. In 2010, 5778 native taxa of higher plants were reported in Cuba, of which 51.4% were classified as endemics (Acevedo-Rodríguez & Strong 2010, González-Torres et al. 2016). The Cuban flora reaches 7500 taxa with Magnoliophyta, Pinophyta, Pteridophyta and Bryophyta included (González-Torres et al. 2013). This richness of ecosystems, plant diversity and the high number of new species described (Ferrer & Herrera 1980, Furrazola et al. 2011b, Torres-Arias et al. 2017b) and probable new species found (Furrazola et al. 2019, Torres-Arias et al. 2019, Furrazola et al. 2020b) suggests that Cuba is an under-explored AMF hotspot in Central America.

A simple method for the evaluation of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization (Herrera & Ferrer 1977) has been described by researchers at the Institute of Botany of the Cuban Academy of Sciences (now the Institute of Ecology and Systematics - IES). Cuban researchers also studied plant response to inoculation (Rivera et al. 2003, Calderón & González 2007, Mujica & Batlle 2013, Ojeda et al. 2014, 2015, Martin & Rivera 2015) and the function of mycorrhizal fungi in different ecosystems (Herrera et al. 1990, 1997, Herrera-Peraza & Furrazola 2002, Furrazola et al. 2015), developing methods, in particular for recovering AM spores, from soil samples and for estimating extraradical mycelium biomass in soil (Herrera et al. 1984a, b, Becerra et al. 2002, Herrera-Peraza et al. 2004).

The research development in tropical countries as such in central America is incipient with highlight a few research groups. Historical reviews can be responsible to rescue preeminent researchers and research neglected by geopolitical barriers that hinder the dissemination of qualified information produced in isolated countries as such Cuba. Historical barriers despite political advances resulting from changes in government (Torres 2016) still remain as impediments to the dissemination of quality information.

Thus, this article traces (ⅰ) the historical development of research on arbuscular mycorrhizae in Cuba, (ⅱ) identify the most important research areas developed and (ⅲ) suggest strengthen areas to the future. This work is the legacy of a small community of committed researchers who are highly motivated to untangle the intricate clumps formed by these special soil fungi.

-

Research on AMF in Cuba began at the end of the 1970's when Dr. Ricardo Herrera conducted preliminary studies of the Cuban savannas (Borhidi & Herrera 1977). He and Roberto L. Ferrer Sánchez also published a method for determining root colonization density by AMF (Herrera & Ferrer 1977), thereby launching an era of research in Cuba. Other pioneering researchers was Nilades Bouza who studied the use of AM in growth of citrus (Bouza et al. 1986) and Maria Ofelia Orozco-Manso who studied AM in decomposing tree trunks (Orozco et al. 1986).

Research on the topic increased markedly in the 1990s, with essential help from the International Foundation for Sciences (IFS; Stockholm, Sweden). A classic work by Ferrer & Herrera (1980) made an important contribution to the study of the genus Gigaspora in Cuba and began the extensive studies of AMF richness in evergreen forests at Sierra del Rosario, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (Ferrer & Herrera 1988, Herrera et al. 1988a, b, 1990).

In 1970 the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (INCA) of the Superior Education Ministry of Cuba was created. In the mid-1980s a Soil Microbiology group lead by Dr. Ana Velazco was formed in the Plant Nutrition Department (now known as the Plant Nutrition and Biofertilizers Department). Dr. Velazco participated in the Fifth International Course on Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation held in 1988 at INRA in Montpelier, France, with great success and, almost simultaneously with Dr. Johana Döbereiner, she was able to isolate the bacteria Gluconoacetobacter diazotrophicus from AMF spores (Velazco et al. 1993). In 1987 Dr. Félix Fernández Martin created another group devoted to arbuscular mycorrhizae research.

Cuban researchers participated in the scientific meeting "Course on Research Techniques in Mycorrhizas" in 1985 supported by the IFS and CATIE (Centro Agrícola Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza) in Costa Rica (Bouza et al. 1986, Ferrer et al. 1986, Herrera et al. 1986a, b, Orozco et al. 1986). This meeting was fertile ground, spurring the creation of the Latin-American Society of Mycorrhizae (SOLAM). The founding President of the Society was Dr. Ricardo Herrera, who was initially elected for two years, then later re-elected in 1990 until the society disbanded in December 2003.

The results of AMF research in Cuba are essentially found in conference proceedings, book chapters, theses and dissertations. These scientific events were organized until 1998 by the IES, when logistic problems and other difficulties prevented to celebrate these meetings during the next years. However, other Cuban institutions organize its own events where some works related with the theme mycorrhiza were debated.

Since 1985, the IES has organized the Botany Symposium. In 1990, that event coincided with the 1st Latin-American Symposium on Mycorrhiza, which took place in Havana and attracted a record number of participants for a meeting in Cuba, with 63 participants from Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Mexico, Peru, Spain, United States, Venezuela and Cuba. That symposium was the start point for a series of meetings which have marked the initial phase of mycorrhizology in Cuba.

A major contribution of the IES mycorrhizologists appears in the book Fungi of the Caribbean (2001), published as part of the United Kingdom's Darwin Initiative. Inventories of different groups of fungi, including AMF, were conducted in three Cuban Biosphere Reserves: Sierra del Rosario, Ciénaga de Zapata and Cuchillas del Toa. That work led to the checklist of Caribbean fungi and a national strategy for fungi conservation in Cuba.

Studies on AMF carried out in Cuba or with the participation of Cuban researchers are increasingly being published in highly respected international scientific journals or books (Herrera-Peraza et al. 2001, 2011, Herrera-Peraza & Furrazola 2002, de la Providencia et al. 2004, 2007, Alonso et al. 2008, Cuenca & Herrera-Peraza 2008, Furrazola et al. 2010, 2011b, 2015, 2016a, Rodríguez et al. 2011, Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2013, Bainard et al. 2014, Błaszkowski et al. 2015a, de Andrade et al. 2017, Torres-Arias et al. 2017a, b). The practical experience with production, use of AMF inoculants in crop production, ecological and physiological studies Rivera et al. (2003) and Sánchez & Furrazola (2018) stablished AM symbiosis management in the Caribbean in addition ecotechnologies using mycorrhizas and seeds treatments, respectively.

Most of the research centres for which AMF is an objective of study are located within or near the city of Havana, political and economical city of the island. However, several research groups have appeared in other parts of the country (Table 1).

Table 1. Principal Cuban institutions that have conducted research on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

Institutions Province Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática (IES), Mycorrhizas Group Havana Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), Department of Mayabeque Biofertilizers and Plant Nutrition Universidad de La Habana (UH), Biology Faculty Havana Universidad Agraria de La Habana (UAH) Mayabeque Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones en Sanidad Vegetal (INISAV) Havana Centro Nacional de Sanidad Agropecuaria (CENSA) Mayabeque Instituto de Investigaciones Hortícolas Liliana Dimitrova (IIHLD) Havana Centro Universitario Municipal (CUM) Cumanayagua Cienfuegos Universidad de Cienfuegos Carlos R. Rodríguez Cienfuegos Estación Experimental de Suelos y Fertilizantes Escambray (Barajagua) Cienfuegos Instituto de Investigaciones de Viandas Tropicales (INIVIT) Villa Clara Estación Experimental de Café de Jibacoa Villa Clara Universidad de Ciego de Ávila (Facultad de Agronomía) Ciego de Avila Universidad de Granma Granma Universidad de Holguín Holguín Universidad de Las Tunas Las Tunas Centro Universitario de Guantánamo, Facultad Agroforestal Guantánamo

-

The principal research lines involving AMF in Cuba are inoculum production and biotechnological applications, taxonomy and diversity, functions of the symbiosis in natural and agricultural ecosystems and mycorrhizal status of plant species.

-

In the early 1990s, the purchase of chemical fertilizers declined drastically as a result of reduced collaboration between Cuba and the countries of Eastern Europe. To mitigate the impact of fertilizer shortage, Cuba created the Biological-Agricultural Front with a mandate of developing biotechnologies for crop production (Herrera-Peraza et al. 2011). The IES led that Front related with the application of AMF in the country, in which approximately 22 Cuban institutions and 90 scientists and technicians participated. An important research effort between 1990 and 1993 led to the development of inoculation technologies and commercial AMF inocula, MicoFert®, produced by the IES.

MicoFert® was tested on several soils and crops, generating two datasets from 130 different experiments assessing the outcome of 548 replicated single inoculation trials (Herrera-Peraza et al. 2011). The datasets were from (ⅰ) high input agriculture (HIA; 343 replicated trials) or (ⅱ) coffee plantations (CP; 205 replicated trials). Surprisingly, there was no significant relationship between plant response to AMF strains and soil test results in HIA systems. The researchers realized that soil fertility tests might not describe the soil conditions driving the distribution of AMF, and soil type might be a better indicator than soil test results. Selecting AMF strains according to soil properties is the key to effective use of AM inoculants in plant production. Several other experiments testing the influence of host plant, substrate, and additives have also advanced our understanding of the effect of AMF on plant growth (Ley-Rivas et al. 2009, 2015, 2017).

The INCA has developed the commercial biofertilizers EcoMic® (solid substrate) and LicoMic® (liquid substrate) to be used on agroecological ecosystems. Positive synergisms and antagonisms among the biological components of the products were used to promote soil fertility, productivity, crop protection, and social equity (Rivera et al. 2003). INCA developed AMF commercial inocula (in vitro) to mycorrhization (Fernández-Suárez et al. 2017), detection of endosporic microorganisms (Alonso et al. 2008), induction of defense response in plant-microorganism interactions (de la Noval & Pérez 2004), and mycorrhizal influence on green manure crops (Martin & Rivera 2015). Research on crop inoculation led to a reduction of inocula application dosages from 2-6 tha-1 to less than 1 tha-1. A formulation for seed coating was an important improvement facilitating use of the inoculant by farmers. The host plants Brachiaria decumbens Steud. and Sorghum vulgare (L.) Pers. also improved the efficiency of AMF propagule production (Ferrer et al. 2004).

The EcoMic® was evaluated in several field trials. The value of the product was demonstrated for rice, cotton, corn, wheat, soybean, beans, and sunflower crops produced in high-and low-input agricultural systems (Rivera et al. 2003). Yield increases up to 43% were obtained with AMF inoculants. The numerous studies conducted by INCA confirmed that highly effective AMF strains are well adapted to a wide range of crops (Rivera et al. 2003, 2007), which enables successful inoculation of crops based simply on soil type.

-

An exhaustive recompilation, undertaken for this review, indicated that AMF richness in Cuba has been studied in ecosystems located in 10 of the 16 provinces. Sampled areas include forests, savannas, wetlands and sand dunes, as well as replacement ecosystems (forest plantations and grasslands) and agroecosystems, encompassing several soil and vegetation types.

In a recent review of the AMF in the Neotropics (Stürmer & Kemmelmeier 2021), Cuba was reported as a high species richness between Caribbean islands. However, only 39 AMF species in Cuba were recorded. In this review we record 79 AMF species (Appendix 1), representing around 25% of global AMF diversity. A chronology of the appearance of these species is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal species reported in Cuba in chronological order

Site/Province AMF species Habitat Reference Pinar del Río, Isla de la

Juventud, La Havana, Villa

ClaraCetraspora gilmorei,

Fuscutata heterogama,

F. savannicola, Gigaspora

margarita, Racocetra

alborosea, R. minuta,

Scutellospora calospora and

S. tricalyptaSavanna, pastureland,

savannas on cuarcitic

sands, tobacco fields,

serpentinitic soilsFerrer & Herrera (1980) Sierra del Rosario/Artemisa Acaulospora foveata,

A. laevis, A. scrobiculata,

A. spinosa, Funneliformis

monosporus, Glomus

clavisporum,

G. macrocarpum,

G. magnicaule,

G. microcarpum,

G. rubiforme, Rhizoglomus

fasciculatum, Sclerocystis

coremioidesEvergreen forests Ferrer & Herrera (1988) Sierra del Rosario/Artemisa Acaulospora longula,

A. myriocarpa, A.rhemii,

Ambispora appendicula,

Archaeospora trappei,

Claroideoglomus etunicatum,

Dentiscutata scutata,

Diversispora spurca,

Entrophospora

infrequens, Funneliformis

geosporum,

F. mosseae, Glomus

aggregatum,

G. microaggregatum,

G. mortonii, G. pachycaule,

Halonatospora pansihalos,

Intraspora schenckii,

Paraglomus occultum,

Sclerocystis sinuosa,

Septoglomus constrictumEvergreen forests,

deciduous forestHerrera-Figueroa et al. (2002) Sierra del Rosario/Artemisa Kuklospora kentinensis Evergreen forests,

deciduous forestOrozco et al.(2003) Sierra del Rosario/

Artemisa, Cuchillas del

Toa/HolguínGlomus brohultii Evergreen forest,

Cuchillas del Toa,

JaguaniHerrera et al. (2003) Las Caobas, Gibara/

HolguínAcaulospora koskei,

A. mellea, Claroideoglomus

claroideum, C. luteum,

Glomus albidum,

G. ambisporum, Rhizoglomus

clarum, Viscospora viscosaAgroecosystem Medina et al. (2010) Bainoa/Mayabeque Gigaspora albida, Glomus

glomerulatumAgroecosystem with

Glycime maxFurrazola et al. (2011a) Sierra del Rosario/Artemisa Glomus crenatum Primary evergreen forest Furrazola et al. (2011b) San Rafael pond, Las

Papas, San José de las

Lajas / MayabequeGlomus cubense Lagoon vegetation area

on a clay soil with

Cynodon nlemfuensis

and Mimosa pigraRodríguez et al. (2011) Bayamo/Granma Acaulospora herrerae Agroecosystems, with

Panicum maximum,

Sporobolus indicus,

Byrsonima crassifoliaFurrazola et al. (2013) Varadero, Hicacos

Peninsula/MatanzasClaroideoglomus hanlinii Maritime dunes with

Phoenix dactyliferaBłaszkowski et al. (2015a) Varadero, Hicacos

Peninsula/MatanzasDiversispora varaderana Maritime sand dune

with Phoenix

dactyliferaBłaszkowski et al. (2015b) Floristic Managed Reserve

San Ubaldo-

Sabanalamar/Pinar del RioAcaulospora morrowiae,

Gigaspora decipiens,

Cetraspora aurigloba,

Septoglomus deserticolaSemi-natural savannah,

recovering savannah

and an agroecosystemFurrazola et al. (2015) Pálpite, Ciénaga de

Zapata/MatanzasAcaulospora excavata,

A. tuberculata,

Claroideoglomus lamellosum,

Funneliformis halonatusSemideciduous forests

with Lysiloma

latisiliquum, Bucida

palustris, Bursera

simarubaTorres-Arias et al. (2015) Santa Maria beach/

La HavanaPacispora dominikii,

Rhizoglomus intraradicesMaritime sand dune González-González et al. (2016) San Andrés, Sierra de los

Órganos/Pinar del RioGlomus segmentatum Holm-oak wood forest

(Quercus cubana)

associated with Pinus

caribeaFurrazola et al. (2016a) Livestock basin

"El Tablón, "

Cumanayagua/CienfuegosCetraspora pellucida,

Dentiscutata heterogama,

Racocetra fulgidaPasturelands with

Megathyrsus maximus,

Pennisetum purpureum,

Brachiaria decumbens,

Cynodon nlemfuensisFurrazola et al. (2016b) Sierra de Moa/Holguín Sieverdingiatortuosa Pinewood (Pinus

cubensis Griseb.,

Cirilla sp., Jacaranda

sp., Guetarda sp.,

Metopium venosum

(Griseb.) Engler),

rehabilitated areas with

Casuarina equisetifolia

Fors and Anacardium

occidentale Lin.Torres-Arias et al. (2017a) Floristic Managed Reserve

San Ubaldo-

Sabanalamar/Pinar del RioGlomus herrerae Semi-natural savannah

(Scoparia dulcis L.,

Cynodon dactylon (L.)

Pers., Sida brittonii

León, Portulaca pilosa

L., Tephrosia cinerea

L. Pers. and

Stylosanthes spp.)Torres-Arias et al. (2017b) Pálpite, Ciénaga de

Zapata/MatanzasOehlia diaphana Agroecosystems with

Manihot

esculentaCrantz.

(cassava), Ipomoea

batatas (L.) Lam.

(sweetpotato) and Musa

paradisiaca L. (banana

plantain)Furrazola et al. (2018) Sierra del Rosario/

ArtemisaAcaulospora denticulata Semi-natural

ecosystemsFurrazola et al. (2019) Artemisa/La Havana/

Mayabeque/Pinar del RioAcaulospora elegans,

Diversispora eburnea,

D. trimurales, D. versiformisAgroecosystems with

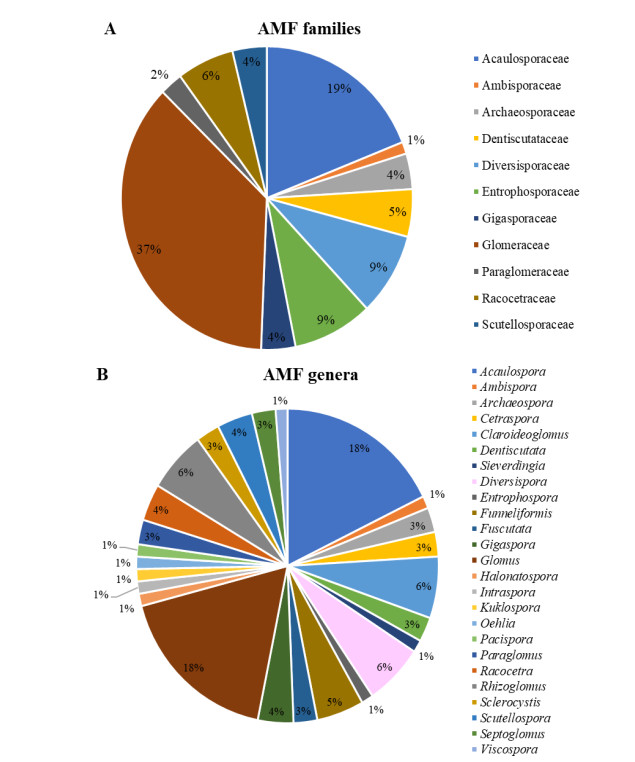

Musa spp.Furrazola et al. (2020a) The species reported in Cuba belong to 11 families and 25 genera (Fig. 1). Glomeraceae (37%) and Acaulosporaceae (19%) are the predominant families and the genera Glomus (18%) and Acaulospora (18%).

Figure 1. Percentage of arbuscular mycorrhizal species distributed in families (A) and genera (B) reported in Cuba.

These groups are well represented in other latitudes and ecosystems (Zhao et al. 2003, Peña-Venegas et al. 2007, Tchabi et al. 2009, Cuenca & Lovera 2010, Medina et al. 2010, Oehl et al. 2010, Stürmer & Siqueira 2010) and have a high number of species. In spite of Glomus was the dominant genus with large number of names associated, there is not phylogenetic evidences supporting that assumption (Glomus as a rich genus) since only five species are recognized as belongs to this clade (Sieverding et al. 2014, Błaszkowski et al. 2019a, b, 2021).

The two best-explored regions for AMF diversity in Cuba correspond to natural forests. These are the Biosphere Reserve of Sierra del Rosario, Pinar del Rio province, in western Cuba, and Moa, Holguin province, in eastern Cuba. The latter and other studied wetland areas were confirmed as zones with the highest AMF species richness in the country (Herrera-Peraza et al. 2016, Torres-Arias et al. 2017a). Other ecosystems, including extensive agricultural systems and coastal sand dunes, have been found to harbour less diverse AMF communities (Furrazola et al. 2011a, González-González et al. 2016).

The species most commonly reported in Cuba, independent of the ecosystem, are Acaulospora scrobiculata, Diversispora spurca, Funneliformis mosseae, Glomus pachycaule, Rhizoglomus intraradices and Sclerocystis sinuosa. These could be considered generalist species adapted to different environments. The species restricted to certain ecosystems or regions are Acaulospora excavata, Gigaspora albida, Glomus herrerae, Glomus segmentatum, Racocetra minuta and Scutellospora tricalypta.

The information on AMF taxonomy and diversity derived from Cuba is of special importance for three reasons. First, 11 of the approximately 330 species currently recognized in the Glomeromycota (Wijayawardene et al. 2020, Goto & Jobim 2021) were described for the first time from Cuban specimens (Fuscutata savannicola, Racocetra alborosea, Racocetra minuta, Scutellospora tricalypta (Ferrer & Herrera 1980), Glomus brohultii (Herrera et al. 2003), Glomus crenatum (Furrazola et al. 2011b), Glomus cubense (Rodríguez et al. 2011), Acaulospora herrerae (Furrazola et al. 2013), Claroideoglomus hanlinii (Błaszkowski et al. 2015a), Diversispora varaderana (Błaszkowski et al. 2015b), Glomus herrerae (Torres-Arias et al. 2017b)). Second, based on the results obtained to date, around 25% of the 55 species of Glomus (Wijayawardene et al. 2020) have been observed in Cuba. Third, an abundance of undescribed species have been found in Cuba. Between 30-40% of the species found in surveys such as those conducted in Moa and Sierra del Rosario were previously undescribed (Torres-Arias et al. 2017a).

Although first described from Cuban ecosystems, some of these species have already been observed in other regions of the world, showing a broad distribution. Glomus brohultii and Fuscutata savannicola have been observed in diverse areas including natural, replacement and agricultural ecosystems. Reports of G. brohultii have come from Africa (Benin and Congo) and several South and Central American countries including Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru and Venezuela (Herrera et al. 2003, Tchabi et al. 2009, Cuenca & Lovera 2010). On the other hand, F. savannicola has been reported in agroecosystems of Benin (Tchabi et al. 2009) and more recently also in Ecuador. Other studies have indicated that Acaulospora herrerae occurs not only in eastern Cuba (Bayamo, Granma and Holguín provinces) in natural areas and agroecosystems, but also in northeastern Brazil (Furrazola et al. 2013, Torres-Arias et al. 2017a).

Other species described from Cuban keep endemic. Glomus cubense is present in natural and agricultural areas of western Cuba and has been used as part of AMF inoculants in various crops including tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.), pasture (Panicum maximum Jacq.), corn (Zea mays L.), durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) and coffee (Coffea arabica L.) (Sánchez et al. 2000, Calderón & González 2007, Terry & Ruiz 2008, Fundora et al. 2009, Rodríguez et al. 2011). Racocetra alborosea has been reported in environments including grasslands within the province of Havana and white sand ecosystems in Guane, Pinar del Rio, as well as the wetlands of Ciénaga de Zapata, Matanzas (Ferrer & Herrera 1980, Torres-Arias et al. 2017a, Furrazola et al. 2015).

Glomus crenatum has been reported in Sierra del Rosario, Moa and Ciénaga de Zapata (Furrazola et al. 2011b, Torres-Arias et al. 2015, 2017a). Meanwhile, Racocetra minuta and Scutellospora tricalypta have been reported exclusively in white sand ecosystems of Isla de la Juventud and grasslands of Macurije, Pinar del Rio (Ferrer & Herrera 1980) and G. herrerae was described from an also a very particular ecosystem like white sand savannas on Managed Floristic Reserve San Ubaldo-Sabanalamar at Pinar del Río, province in western Cuba. In this reserve, the semi-natural savannah on quartzite sand is predominant, white sands originated from Holocene sandy deposits with secondary vegetal formations (Ricardo et al. 2009).

-

Several studies on the functioning of AM symbiosis in Cuba have been developed in evergreen forests of Sierra del Rosario. They have concentrated on functional characterization of the mycorrhizal symbiosis with primary forest trees, evaluating the influence of different soils on the mycotrophy and mycorrhizal dependency of seedlings (Ferrer & Herrera 1988, Herrera et al. 1988a, b, 1990, 2004).

The results obtained indicated that mycorrhizal diversity and functioning follow two principal strategies. The first strategy, exuberant, occurs in ecosystems with high turnover and organic matter decomposition rates where available moisture is not a limiting factor (roadside slopes or forest gaps where heliophylous plants are prevalent). Exuberant AM associations promote plant growth and reproduction and therefore increase availability of photosynthetic carbon for the AMF. Consequently, low rootlets, external mycelia biomasses and high internal mycelium or endophyte density and biomasses are obtained. The result is a photosynthetically costly, but highly "aggressive" and efficient, mycorrhizal symbiosis. The second strategy, austerity, occurs in ecosystems with low turnover and decomposition rates (root mats are observed on the forest soil) and insufficient water availability. It is probably marked by lower photosynthetic rates (Herrera et al. 2004). These ecosystems are characterized by high rootlet and extraradical mycelial biomass and low internal mycelium density and biomass. The symbiosis is not photosynthetically costly and is typical of the final stage of tropical forests or climax stages.

The observations of Orozco et al. (2003) assessing the effect of natural sources of inocula from Sierra del Rosario support the assumption of exuberance and austerity as AMF lifestyles in different ecosystems. Growth stimulation was superior in plants inoculated with soil taken from a well-exposed roadside slope compared to primary forest soils. The effect obtained with the roadside slope AMF community would be equivalent to the effect of AMF communities originating from agricultural soils fully exposed to solar radiation, where avid photosynthate-consuming generalists predominate. A richer AMF community was found in the rooting soil of plants inoculated with the exuberant community of the well-exposed roadside slope than in plants inoculated with primary forest soil (36 vs 24 AMF morphospecies).

Low availability of moisture selects for austere AMF communities in Sierra del Rosario, as does reduced availability of photosynthates. Increases in water stress and the advancement of successional stages select for a biota able to survive in harsh conditions. The impact of low moisture availability on AMF diversity can be attributed to reduced turnover rates in dry forests (Herrera et al. 1997). According to these authors, moisture shortage leads to organic matter accumulation, which results in more niches that could be occupied by a higher number of subordinate AMF species.

In these evergreen forests, one of the two defined functional strategies is characterized by lower turnover rates (low organic matter decomposition), higher water stress related to more complicated nutrient conservation mechanisms (occurrence of root mats on), larger quantities of dead organic matter on soil and probably lower photosynthetic rates as consequence of lower leaf specific area (Herrera et al. 1997). This austerity condition (related with the K end along the universal r-K continuum) and predominant in primary forest of this Biosphere Reserve selects for richer AMF communities. The highest level of richness in Sierra del Rosario was found in a primary forest mainly composed of Pseudolmedia spuria Sw. Griseb., Oxandra lanceolata (Sw.) Baill., Trophis racemosa (L.) Urb., Matayba apetala (Macf.) RDLK., Dendropanax arboreus (L.) DEC. et Planch. and Calophyllum antillanum Britt. as woody species and 27 AMF species and/or morphospecies, followed by an old closed gap, with Zanthoxylum martinicense (Lam.) DC as principal plant species and 26 AMF species in a natural plot with predominance of Hibiscus elatus Sw. and 25 AMF species.

A study of Glomeromycotan communities associated with forest successional stages in Sierra del Rosario indicated a recurrent pattern in the species profile. There were one to three very dominant AMF morphospecies, about five dominant species, and several subordinate species (Halffter 1992).

Studies of the functioning of symbiosis and AMF communities have also been developed for eastern Cuba. The region of serpentine ultramafic rocks in the northeast of the eastern provinces has soils that support one of the highest floristic diversity and endemism levels on the island (Berazain 2003). Plant species in this region are adapted to oligotrophic conditions and toxicity from heavy metals, especially Ni, Cr and Co (Berazain 1981). Four groups of AMF species exist in these zones: (ⅰ) species adapted to natural pine groves ("pinares"); (ⅱ) species adapted to calcium and magnesium rich forest; (ⅲ) species striving in both environments, and (ⅳ) species exclusively in planted forests. The AMF species observed in those forests are characterized by small spores (47 μm and 100 μm) and negative binomial distributions, which suggest the presence of ancestral AMF communities that are rich in local endemism, as such the plant communities in that region of Cuba (Herrera-Peraza et al. 2016)

Eleven glomeromycotan species were classified as indicators of ultramafic calcareous soils, pristine, contaminated by mining and rich in aluminum, nickel, cobalt, or copper, and natural (Herrera-Peraza et al. 2016). Most of these indicator species belong to the genus Glomus, supporting the conclusion that species belonging to the order Glomerales are more stress-tolerant than the Diversisporales (de Souza et al. 2005). Those species produced typical dark-pigmented brown glomerospores.

-

Several research programs on mycotrophy of plant species have been developed in Cuba. Herrera & Ferrer (1980) carried out the pioneering work reporting 17 plant species as mycotrophic. Then, Ferrer & Herrera (1985) analyzed 75 new plant species belonging to 37 families and showed only one (Polygonaceae) was not mycorrhizal. Amarantaceae, Annonaceae, Arecaceae, Asclepiadaceae, Bignoniaceae, Boraginaceae, Cactaceae, Caesalpinaceae, Clusiaceae, Commelinaceae, Compositae, Cyperaceae, Dilleniaceae, Eriocaulaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Hypericaceae, Malpighiaceae, Malvaceae, Meliaceae, Mimosaceae, Moraceae, Myrtaceae, Poaceae, Proteaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rosaceae, Rubiaceae, Rutaceae, Sapindaceae, Sapotaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Solanaceae, Sterculiaceae, Tiliaceae and Verbenaceae were classified as mycotrophic families.

These authors also studied 60 plant species in an evergreen forest at the Biosphere Reserve of Sierra del Rosario (Ferrer & Herrera 1988). This time, Araliaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Lauraceae, Melastomataceae, Menispermaceae, Myrsinaceae, Simarubaceae and Smilacaceae were added to the list of mycorrhizal plant families in Cuba. Other studies addressing the mycorrhizal status of plant species were performed by Cruz (1987) and Rodríguez-Rodríguez (2014). The latter evaluate 20 endemic plant species in white sand ecosystems within the Managed Floristic Reserve of San Ubaldo-Sabanalamar in the Pinar del Rio province. As a result, Asteraceae, Cistaceae, Ericaceae, Phyllanthaceae and Polygalaceae were added as mycotrophic plants (Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2014), totalizing 50 families. Recently, Furrazola et al. (2020b) defined the arbuscular mycorrhizal status of an endemic and critically endangered plant species Coccothrinax crinita Griseb. & H. Wendl. ex C. H. Wright, Becc., Arecaceae strictly to Bahía Honda municipality which is considered one of the most endangered palms in the insular territories of America (Jestrow et al. 2018).

-

Genetic research on AM has barely begun. Based on previous studies (Sanders et al. 1992, Perotto et al. 1994, Simon 1996), de la Providencia et al. (2002) developed a polyclonal antibody against Rhizoglomus clarum to enable its detection by indirect immunofluorescence (IF) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The antibody raised allows detection of R. clarum spores and extraradical mycelium without crossed reactions with other species of Glomerales (de la Providencia 2002).

Furrazola et al. (2010) used the LSU nrRNA gene sequence and phylogenetic tools to describing Glomus candidum (now as Claroideoglomus candidum). Rodríguez et al. (2011) also used molecular markers when performing a phylogenetic analysis of the rDNA ITS region and H+ATPase in their description of Glomus cubense. On the other hand, in the case of Acaulospora herrerae (Furrazola et al. 2013), partial sequences of the LSU rRNA gene confirm the new fungus whereas PCR reactions were performed according Goto et al. (2012) with some modifications.

Rodríguez et al. (2014) studied the spore morphologic characteristics and other molecular protocols like rDNA ITS region and V-H+-ATPasa, in spores of INCAM 2 strain, which was identified as Funneliformis mosseae.

Recently, Rodríguez-Yon et al. (2021) published a taxon-discriminating molecular marker with the purpose of trace and quantify the presence of a mycorrhizal inoculum in roots and soils of different agroecosystems. Normally is difficult to connect yield effects with any AMF strain abundance in roots due to the lack of an adequate methodology to trace this taxon in the field. In order to that, it is necessary to establish an accurate evaluation framework of its contribution to root colonization separated from native arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. A taxon-discriminating primer set was designed for Glomus cubense isolate (INCAM-4, DAOM-241198) based on the ITS nrDNA marker and two molecular approaches were optimized and validated (endpoint PCR and quantitative real-time PCR) to trace and quantify G. cubense isolate in root and soil samples under greenhouse and environmental conditions. Different AMF taxa were used for endpoint PCR specificity assay, showing that primers specifically amplified the INCAM-4 isolate yielding a 370 bp-PCR product. In the greenhouse an assay with Urochloa brizantha plants inoculated with three isolates (Rhizoglomus irregularis, R. clarum, and G. cubense) and environmental root and soil samples were successfully traced and quantified by qPCR. This study demonstrates for the first time the feasibility to trace and quantify the G. cubense isolate using a taxon-discriminating ITS marker in roots and soils. The validated approaches reveal their potential to be used for the quality control of other mycorrhizal inoculants and their relative quantification in agroecosystems.

-

In the future, taxonomic identification of AMF should be based on both morphological criteria and molecular analysis as suggested by Błaszkowski et al. (2021). The high number of glomeromycotan fungi recently described around the world show the necessity an improve those methods to distinguish fungi with very similar morphology and absence of synapomorphies in the Glomeraceae (Błaszkowski et al. 2018, 2021, Corazon-Guivin et al. 2019, Jobim et al. 2019).

Despite the importance of mycorrhizae for the maintenance of biodiversity and ecosystem functions, surprisingly little information exists about landscape-scale biogeographical patterns of AM fungal species and the environmental factors that influence species distributions (Chaudhary et al. 2018). However, landscape-scale studies linking the distributions of mycorrhizal fungal species to environmental factors are essential to a full understanding of the importance of their role in ecosystem functioning and services provided across landscapes. Fortunately, the ecosystem approach in mycorrhizal research is being implemented in Cuba. A project titled "A Landscape Approach to the Conservation of Threatened Mountain Ecosystems" was financed by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). The UNDP project "Reduction of vulnerability to coastal flooding through ecosystem-based adaptation in the south of Artemisa and Mayabeque provinces, " involving the application of mycorrhizal inocula in forest nurseries to increase survival of seedlings during transplant to the field, was also approved. Those project looks at ways to reduce the vulnerability of coastal communities under climate change conditions, including coastal erosion, flooding, and saline intrusions, through reforestation of degraded coastal zones of mangroves and wetlands.

The role of AM symbiosis in ecosystem physiology is another subject that requires attention in different parts of the world. The study of AMF in protected areas or natural ecosystems should be a strong focus in Cuba. As noted by Turrini & Giovannetti (2012), studying the occurrence and distribution of potentially endemic AMF ecotypes in protected areas worldwide provides a strategic perspective from which to increase awareness of the importance of these beneficial symbionts.

The functional diversity of AMF needs to be incorporated into our research. Angelard et al. (2010), working with genetically different AMF isolates of Rhizhoglomus intraradices, found functional differences among them, producing different effects in host plants. Each fungal species or strain may play a different role in biogeochemical cycles or plant success (Montaño et al. 2012). The principal Cuban AMF inoculants are MicoFert® (composed of several AMF species) and EcoMic® (composed of a single AMF species).

The development of nickel mining in eastern Cuba makes it essential to carry out AMF inventories in undisturbed, transformed or endangered ecosystems, as well as to develop eco-technologies involving AMF to rehabilitate these ecosystems. The IES has an incipient AMF collection of native and introduced AMF in vivo cultures, (Colección Cubana de Hongos Micorrizógenos Arbusculares - CCHMA) which provides inocula or fungi for national researchers. Cuban scientists have traditionally collaborated very productively with different fungal collections at over the world. These collaborations needs to be relaunched.

There are barriers that, if not lifted, may hamper the effectiveness of priority research in Cuba. Mycorrhizologists are an aging workforce in this country. A new challenge is the recruitment of highly qualified young technicians and researchers who can conduct effective research in Cuba. Government regulations are also needed to allow the introduction of foreign inocula for long-term evaluation and comparison with our commercial inocula. Finally, stable isotopes, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and genetic techniques have become essential tools in AMF research, but accessing these tools still a very challenging for Cuban mycorrhizologists.

-

Since the first publication on mycorrhizae in Cuba in 1977 approximately four decades ago, Cuban research has been pursued intensely and successfully, making important advances in knowledge about AMF diversity and the functioning of ecosystems that are among the richest and most complex on earth, providing knowledge and effective biotechnologies to improve the efficiency and sustainability of agroecosystems. Given the broad diversity of vascular plants and ecosystems in Cuba, AMF diversity in the country could exceed the 79 species reported to date. Strains that are as yet unknown may be important in the future for greenhouse or field production, in landscape preservation combining economists and conservationists' perspectives, and in the production of commercial inocula.

The study of AMF species from natural and transformed ecosystems will provide a better way to employ the AM symbiosis under different edapho-climatic conditions. This will improve our understanding of what kind of AMF to apply in order to improve plant production under sustainable production systems. In addition, AMF might contribute to the rehabilitation of different ecosystems through their biofertilizer capacity. With a long way to go, new challenges will arise in the near future in those fields.

-

In memory to Eduardo Furrazola victim of COVID-19 during correction of this proof. He left leaving a broad legacy to mycorrhizology in Latin America. We sincerely thank Esther Collazo, Maritza Portier†, Osbel Gómez, Carlos Massia and Yosvany Gutiérrez for their technical assistance. They participated in various productions of MicoFert® over many years, as well as in field expeditions. Our work was supported by the following UNDP projects: "A Landscape Approach to the Conservation of Threatened Mountain Ecosystems" and "Reduction of Vulnerability to Coastal Flooding through Ecosystem-based Adaptation in the South of Artemisa and Mayabeque Provinces", as well as by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) that provided research grants to BT Goto (proc. 311945/2019-8) and MB Queiroz.

-

Class/Order/Family/Genus and Species Archaeosporomycetes Archaeosporales Archaeosporaceae J.B. Morton & D. Redecker Archaeospora Morton & D. Redecker Archaeospora myriocarpa (Spain, Sieverd. & N.C. Schenck) Oehl, G.A. Silva, B.T. Goto & Sieverd. Archaeospora trappei (R.N. Ames & Linderman) J.B. Morton & D. Redecker Intraspora Oehl & Sieverd. lntraspora schenckii (Sieverd. & S. Toro) Oehl & Sieverd. Ambisporaceae C. Walker, Vestberg & A. Schüssler Ambispora C. Walker, Vestberg & A. Schüssler Ambispora appendicula Spain, Sieverd. & Schenck Glomeromycetes Diversisporales Acaulosporaceae J. B. Morton & Benny Acaulospora Gerdemann & Trappe Acaulospora denticulata Sieverd. & Toro Acaulospora elegans Trappe & Gerd. Acaulospora excavata Ingleby & C. Walker Acaulospora foveata Trappe & Janos Acaulospora herreraeFurrazola, B.T. Goto, G.A. Silva, Sieverd. & Oehl Acaulospora koskei Błaszk. Acaulospora laevis Gerd. & Trappe Acaulospora longula Spain & N.C. Schenck Acaulospora mellea Spain & N.C. Schenck Acaulospora morrowiae Spain & N.C. Schenck Acaulospora rehmii Sieverd. & S. Toro Acaulospora scrobiculata Trappe Acaulospora spinosa C. Walker & Trappe Acaulospora tuberculata Janos & Trappe Kuklospora Oehl & Sieverd. Kuklosporakentinensis (Wu & Liu) Oehl & Sieverd. Diversisporaceae C. Walker & A. Schüssler. emend. Oehl, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Diversispora C. Walker & A. Schüssler. emend. G.A. Silva, Oehl & Sieverd. Diversispora eburnea (L.J. Kenn., J.C. Stutz & J.B. Morton) C. Walker & Schüssler Diversispora spurca (C.M. Pfeifer, C. Walker & Bloss) C. Walker & Schüssler Diversispora trimurales (Koske & Halvorson) C. Walker & A. Schüssler Diversispora varaderana Błaszk., Chwat, Kovács & Góralska Pacispora Sieverd. & Oehl Pacispora dominikii (Błasz.) Sieverd. & Oehl Sieverdingia Błaszk., Niezgoda & B.T. Goto Sieverdingia tortuosa (N.C. Schenck & G.S. Sm) Błaszk. Niezgoda & B.T. Goto Glomerales Entrophosporaceae Oehl & Sieverd. emend. Oehl, Sieverd., Palez. & G.A. Silva Claroideoglomus C. Walker & A. Schüssler. emend. Oehl, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Claroideoglomus claroideum (N.C. Schenck & G.S. Sm.) C. Walker & A. Schüssler Claroideoglomus etunicatum (W.N. Becker & Gerd.) C. Walker & A. Schüssler Claroideoglomus hanlinii Błaszk., Chwat & Góralska Claroideoglomus lamellosum (Dalpé, Koske & Tews) C. Walker & A. Schüssler Claroideoglomus luteum (L.J. Kenn., J.C. Stutz & J.B. Morton) C. Walker & A. Schüssler Entrophospora Ames & Schneid. emend. Oehl & Sieverd. Class/Order/Family/Genus and Species Entrophospora infrequens (I.R. Hall) R.N. Ames & R.W. Schneid. Viscospora Sieverd., Oehl & F.A. Souza Viscospora viscosa (T.H. Nicolson) Sieverd., Oehl & F.A. Souza Glomeraceae Piroz. & Dalpé. emend. Oehl, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Funneliformis C. Walker & A. Schüssler. emend. Oehl, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Funneliformis geosporum (T.H. Nicolson & Gerd.) C. Walker & A. Schüssler Funneliformis halonatum (S.L. Rose & Trappe) Oehl, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Funneliformis monosporus (Gerd. & Trappe) Oehl, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Funneliformis mosseae (T.H. Nicolson & Gerd.) C. Walker & A. Schüssler Glomus Tul. & Tul. emend. Oehl, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Glomus ambisporum G.S. Sm. & N.C. Schenck Glomus brohultii Sieverd. & Herrera Glomus clavisporum (Trappe) R.T. Almeida & N.C. Schenck Glomus crenatumFurrazola, R.L. Ferrer, Herrera & B.T. Goto Glomus cubense Y. Rodr. & Dalpé Glomus herrerae Torres-Arias, Furrazola & B.T. Goto Glomus glomerulatum Sieverd. Glomus macrocarpum Tul & C. Tul Glomus magnicaule I.R. Hall Glomus microcarpum Tul. & C. Tul. Glomus mortonii Bentiv. & Hetrick Glomus pachycaule (C.G. Wu & Z.C. Chen) Sieverd. & Oehl Glomus rubiforme (Gerd. & Trappe) R.T. Almeida & N.C. Schenck Glomus segmentatum Trappe, Spooner & Ivory Halonatospora Błaszk., Niezgoda, B.T. Goto & Kozłowska Halonatospora pansihalos S.M. Berch & Koske Oehlia Błaszk., Kozłowska, Niezgoda, B.T. Goto & Dalpé Oehlia diaphana (J.B. Morton & C. Walker) Błaszk., Kozłowska & Dalpé Septoglomus Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Septoglomus constrictum (Trappe) Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Septoglomus deserticola (Trappe, Bloss & J.A. Menge) G.A. Silva, Oehl & Sieverd. Rhizoglomus Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Rhizoglomus aggregatum (N.C. Schenck & G.S. Sm.) Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Rhizoglomus clarum (T.H. Nicolson & N.C. Schenck) Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Rhizoglomus fasciculatum (Thaxt.) Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Rhizoglomus intraradices (N.C. Schenck & G.S. Sm.) Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Rhizoglomus microaggregatum (Koske, Gemma & P.D. Olexia) Sieverd., G.A. Silva & Oehl Sclerocystis Berk. & Broomee Sclerocystis coremioides Berk. & Broome Sclerocystis sinuosa Gerd. & B.K. Bakshi Gigasporales Dentiscutataceae Sieverd., F.A. de Souza & Oehl Dentiscutata Sieverd., F.A. de Souza & Oehl Dentiscutata heterogama (T.H. Nicolson & Gerd.) Sieverd., F.A. Souza & Oehl Dentiscutata scutata (Walker & Dieder.) Sieverd., F.A. de Souza & Oehl Fuscutata Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Fuscutata heterogama Oehl, F.A. Souza, L.C. Maia & Sieverd. Fuscutata savannicola (R.A. Herrera & Ferrer) Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Gigasporaceae Morton & Benny. emend. Sieverd., F.A. de Souza & Oehl Gigaspora Gerdemann & Trappe. emend. Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Gigaspora albida N.C. Schenck & G.S. Sm. Gigaspora decipiens I.R. Hall & L.K. Abbott Gigaspora margarita W.N. Becker & I.R. Hall Class/Order/Family/Genus and Species Racocetraceae Oehl, Sieverd. & F.A. Souza Cetraspora Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Cetraspora gilmorei (Trappe & Gerd.) Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Cetraspora pellucida (T.H. Nicolson & N.C. Schenck) Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Racocetra Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Racocetra alborosea (Ferrer & R.A. Herrera) Oehl, F.A. Souza & Sieverd. Racocetra fulgida (Koske & C. Walker) Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Racocetra minuta (Ferrer & R.A. Herrera) Oehl, F.A. Souza & Sieverd. Scutellosporaceae Sieverd., F.A. Souza & Oehl Scutellospora (Walker & Sanders) emend. Oehl, F.A. de Souza & Sieverd. Scutellospora aurigloba (I.R. Hall) C. Walker & F.E. Sanders Scutellospora calospora (T.H. Nicolson & Gerd.) C. Walker & F.E. Sanders Scutellospora tricalypta (R.A. Herrera & Ferrer) C. Walker & F.E. Sanders Paraglomeromycetes Paraglomerales Paraglomeraceae J.B. Morton & Redecker Paraglomus J.B. Morton & Redecker Paraglomus albidum (C. Walker & L.H. Rhodes) Oehl, F.A. Souza, G.A. Silva & Sieverd. Paraglomus occultum (C. Walker) J.B. Morton & D. Redecker

- Copyright: © 2021 by the author(s). This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| E Furrazola, Y Torres-Arias, L Ojeda-Quintana, RO Fors, R Rodríguez-Rodríguez, JF Ley-Rivas, A Mena, S González-González, RLL Berbara, MB Queiroz, C Hamel, BT Goto. 2021. Research on arbuscular mycorrhizae in Cuba: a historical review and future perspectives. Studies in Fungi 6(1):240−262 doi: 10.5943/sif/6/1/16 |