-

Angiosperms usually produce bisexual flowers. In order to increase the genetic diversity of offspring, plants have evolved several systems to prevent self-fertilization, such as sexual differentiation[1]. The plants with sex differentiation can produce different types, such as monoecious, dioecy and so on. The evolution from hermaphrodite to unisexual flowers is controlled by sex-determining genes[2, 3]. Floral control is important for agricultural breeding and production, such as F1 hybrid seed production and fruit production of dioecious crops.

There are a large number of monoecious or dioecious species in cucurbitaceous, so it is a good plant model for studying sexual differentiation[1]. In melon, the flowers are bisexual during the early stages of development, and then the arrest of the stamen or carpel primordium leads to sex determination, resulting in unisexual flowers. In the process of sex determination, andromonoecious (M)[4], Andromonoecious (A)[5] and gynoecious (G)[6] encode CmACS-7, CmACS11 and CmWIP1. The interaction of M, A, and G genes has resulted in different sex types[6], but the relationship between sex-determining genes and sexual flower development remains a mystery.

On November 4th, 2022, Institute of Plant Sciences Paris-Saclay (IPS2), University of Paris-Saclay (Paris, France), Abdelhafid Benda mane's team published a research paper entitled 'The control of carpel determinacy pathway leads to sex determination in cucurbits' in the international authoritative academic journal Science (with Siqi Zhang and Fengquan Tan as co-first authors), shedding light on the mysteries of sex determination and the regulation of bisexual flower development[7].

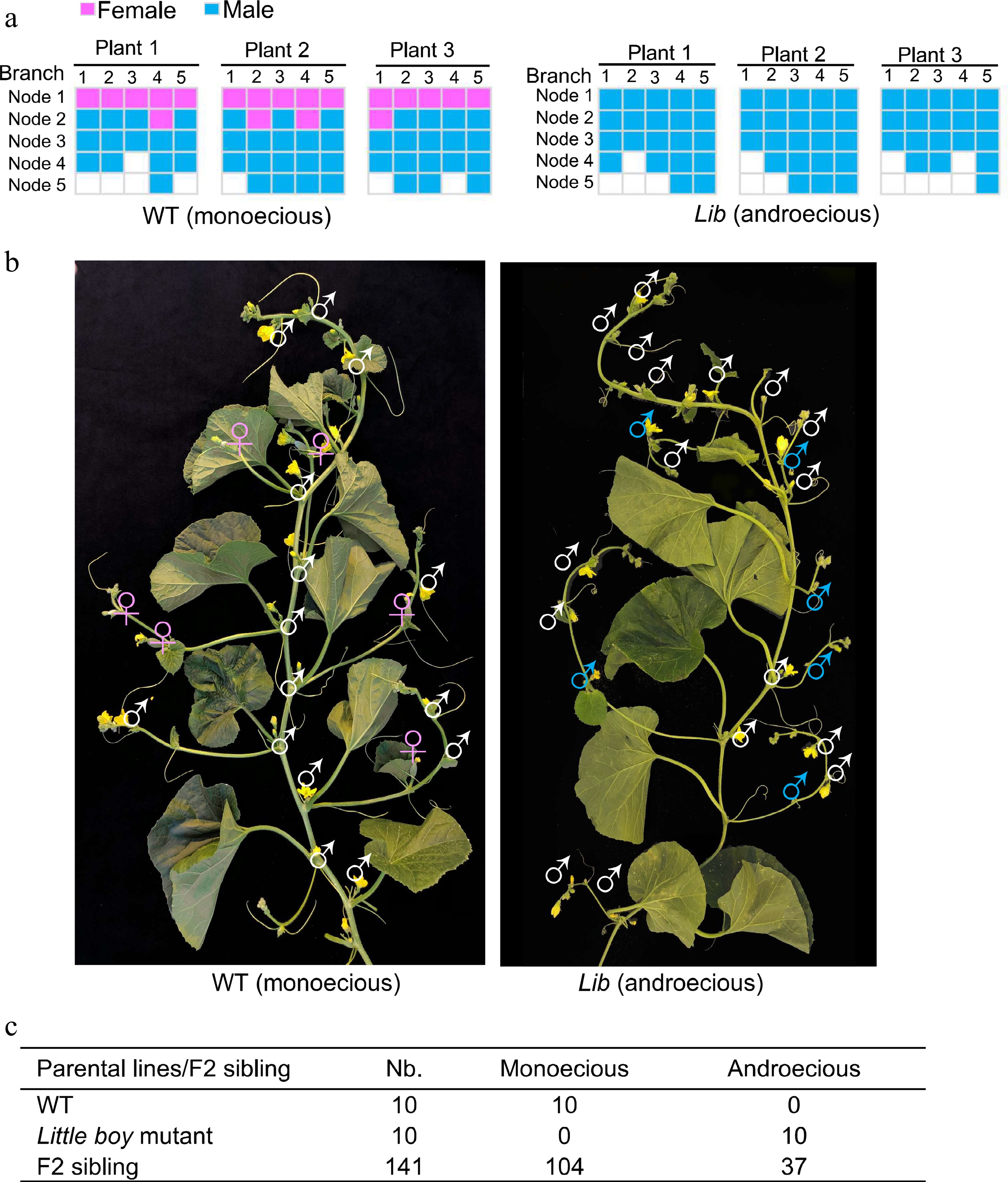

The researchers isolated a female-to-male sex transition mutant in melon and identified the mutation as the carpel development gene CRABS CLAW (CRC) through genetic mapping (Fig. 1). The CRC was validated by virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) and NGS-TILLING (targeted induced local genomic lesions based on second-generation sequencing) techniques. In situ hybridization and real-time quantitative PCR showed that the expression of CRC was inhibited by the sex-determined female flower gene WIP1, and genetic double mutant analysis showed that WIP1 acted upstream and is epistatic against CRC in the sex determination pathway[7].

Figure 1.

Sexual morphs observed in monoecious melon and androecious little boy mutant[7]. (a) Graphical presentation of flower sexual types observed in wild type monoecious melon (Cucumis melo) and Lib (Little boy) androecious mutant. (b) Phenotype of Lib mutant. Female flowers (in pink) were transformed into male flowers (in blue) in Lib mutant. The inflorescence structure in the Lib mutant is not affected. (c) Segregation analysis of androecious phenotype in F2 populations. Nb, total number of plants.

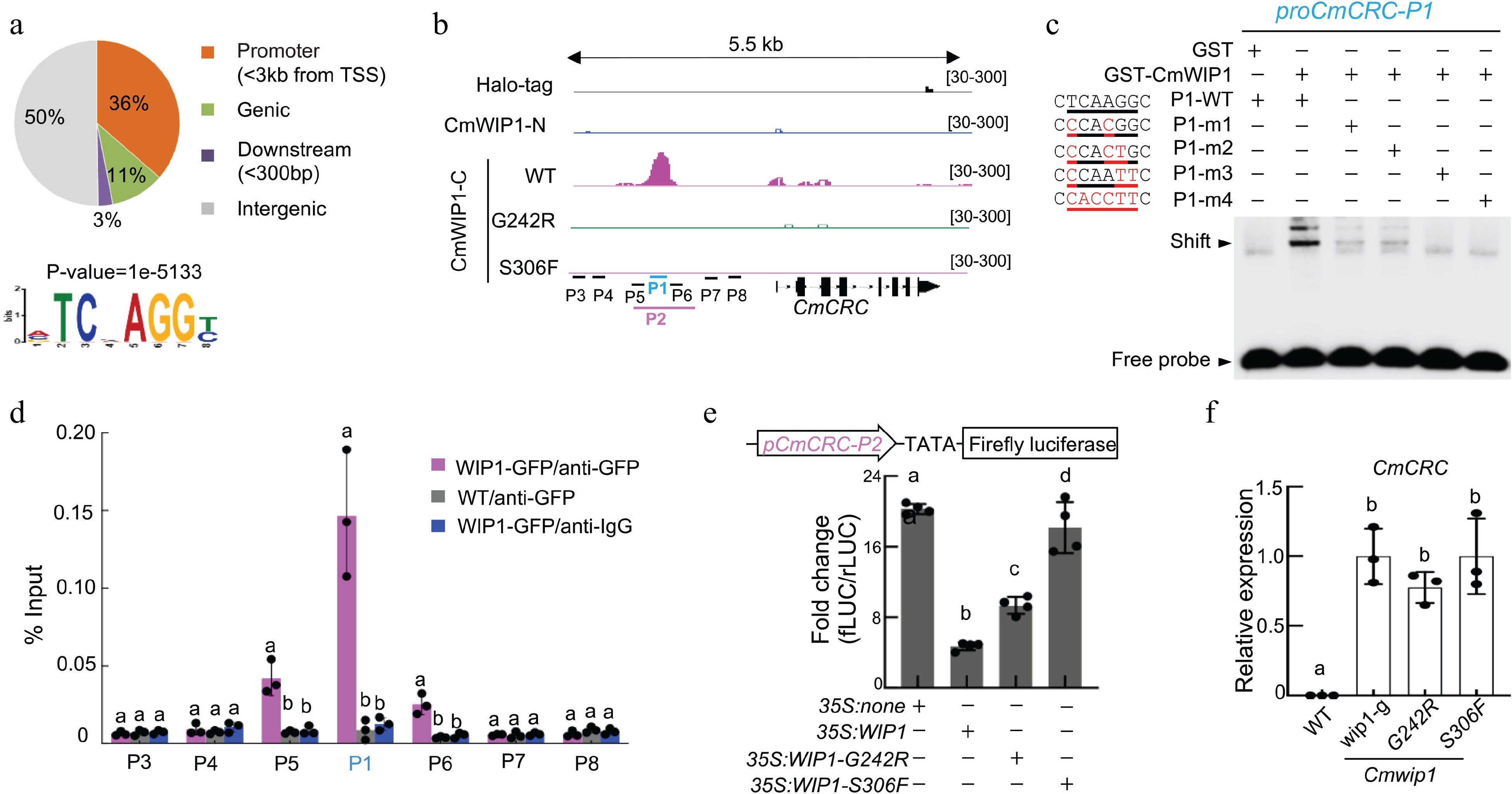

To investigate whether WIP1 is a direct suppressor of CRC expression, the authors used ampDAPseq to map genome-wide DNA binding of WIP1. The promoter of CmCRC was found to have a binding peak of CmWIP1 with a conserved WIP motif, but the CmCRC promoter could not be bound by WIP1 mutant proteins G242R and S306F (Fig. 2a). Electrophoretic mobility change analysis (EMSA), ChIP-qPCR, luciferase reporting system were also used to further verify that CmWIP1 binds to the promoter of CRC and its binding inhibits the expression of CRC (Fig. 2b & c).

Figure 2.

CmWIP1 binds to the CRC promoter[7]. (a) Distribution of CmWIP1 DAP-seq peaks and CmWIP1 binding motif. (b) CmWIP1 binding at the CmCRC locus. Halo-tag, negative control; -N, N terminus; -C, C terminus; P1 to P8, promoter sequences used in EMSA, ChIP, and promoter activity assays. G242R and S306F mutations in WIP1 DNA binding domain. (c) EMSA assay. A5-μM GST or WIP1-GST protein and a 10-nM DNA probe were used. P1-m1 to P1-m4, mutant probes. GST, Glutathione S-transferase. (d) ChIP-qPCR assay in melon protoplast transformed with 35S:WIP1-GFP. Results are expressed as a percentage of the INPUT fraction. Wild-type protoplasts and anti-IgG antibody were used as negative controls. (e) Promoter activity assays. Empty vector (35S: none), 35S:WIP1 or variants were co-transformed into melon protoplasts along with pCmCRC-P2: fLUC. Bars represent means ± SD (n = 4). (f) qRT-PCR analysis of CmCRC. Flower buds at stage 6 were used. wip1 (g), a natural epigenetic mutant; G242R and S306F, TILLING mutants (14). In (d)−(f), bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3) and different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test).

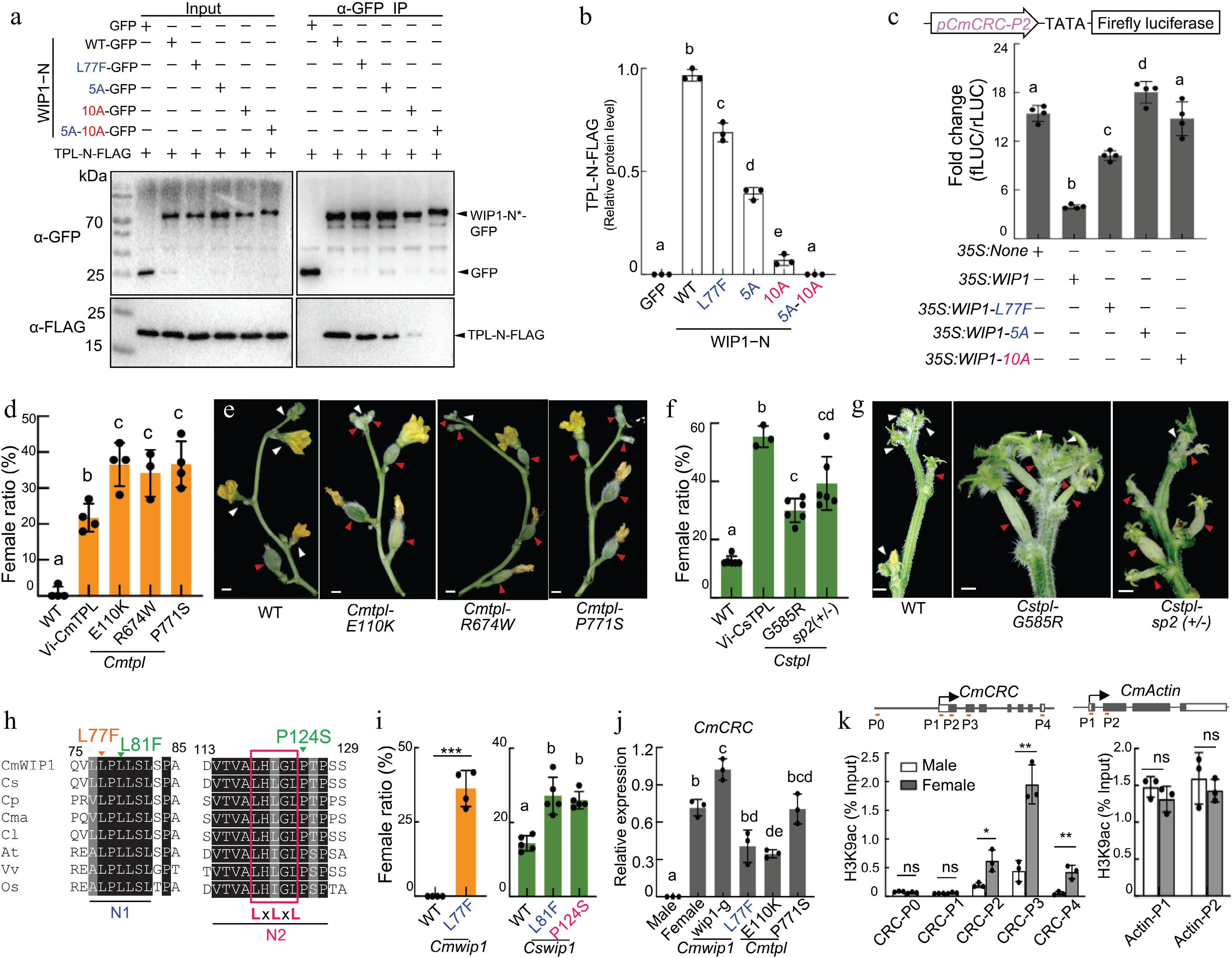

To uncover the molecular mechanism of WIP1-mediated CRC transcriptional suppression, IPS2 screened chaperone protein of WIP1 using a yeast two-hybrid system and found that WIP1 binds to the co-suppressor protein TPL. Further study showed that the physical interaction involves the N-terminal domain of CmWIP1 and the LisH, CTLH and CRA domains of TPL. The WIP1 N-terminal domain contains two conserved motifs N1 and N2. The three-dimensional structural model predicts that N1 and N2 may form a stem-ring structure, which is related to the interaction of TPL recruitment. The authors found that single N1 and N2 mutants partially affected the interaction, while N1-N2 double mutants completely lost the interaction. The interaction between WIP1 and TPL was further verified by transient expression and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) in melon protoplasts. At the same time, it was found that the activity of pCRC:LUC reporter gene was significantly recovered when the N1 or N2 mutant proteins of WIP1 were expressed, indicating that WIP1 inhibited CRC expression through the binding of N1 and N2 motifs with TPL (Fig. 2e).

In order to verify the biological relevance of WIP1-TPL interaction in CRC inhibition, the male flowers of plants subjected to VIGS of TPL were partially feminized and even completely changed from male to female. Mutants with complete loss of TPL function screened using NGS-TILLING were unable to flower. Therefore, the authors performed phenotypic analysis of the single amino acid missense mutants and found that four mutants resulted in 30 to 40 percent female flowers developing where male flowers should have been. The WIP1-TPL interaction involved the N1 and N2 motifs of WIP1, and the authors also screened TILLING mutants in these two motifs and observed that they exhibited feminized characteristics, such as stigmas and ovule-bearing ovaries in the flowers that were male. Moreover, inhibition of CRC expression was removed in WIP1 N1 and N2 mutants. Since it has been previously reported that TPL recruits histone deacetylases to inhibit the expression of target genes, the authors analyzed the histone acetylation levels of CRC in male and female flowers, and the CRC region H3K9ac was significantly reduced in male flowers compared with female flowers. Thus, the WIP1-TPL complex binds to the promoter of CRC and deacetylates its gene region histone to inhibit its gene expression, thereby promoting male flower development (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

WIP1 recruits Topless to repress CRC[7]. (a) Co-IP assays. GFP-tagged WIP1−N or variants (asterisk) were co-transformed into melon protoplasts along with FLAG-tagged TPL-N. (b) Quantification of FLAG-tagged TPL-N from Co-IP assays in (a). (c) Promoter activity assay. Empty vector (35S: none), 35S:WIP1 or variants were co-transformed into melon protoplasts along with pCmCRC-P2: fLUC. Statistical analysis of female flower ratio in monoecious (WT), VIGS-CmTPL (Vi-CmTPL) and tpl mutants in (d) melon and (f) cucumber. Flower phenotypes of tpl mutants in (e) melon and (g) cucumber; white and red triangles denote male and female flowers, respectively; scale bars, 5 mm. (h) Sequence alignment of WIP1 and homologous proteins showing N1 and N2 motifs. Initials of species are indicated. LxLxL, EAR motif. Induced mutations in melon (orange) and cucumber (green) are shown. (i) The female ratio [females/(females + males)], in percent, of nodes 2 to 10 of lateral branches (melon) and nodes 1 to 20 of main stem (cucumber). qRT-PCR analysis of (j) CmCRC and ChIP-qPCR analysis of (k) H3K9ac at stage 6 flower buds. CmACTIN1, control. Bars represent means ± SD (n = 3−5); different letters denote significant differences p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

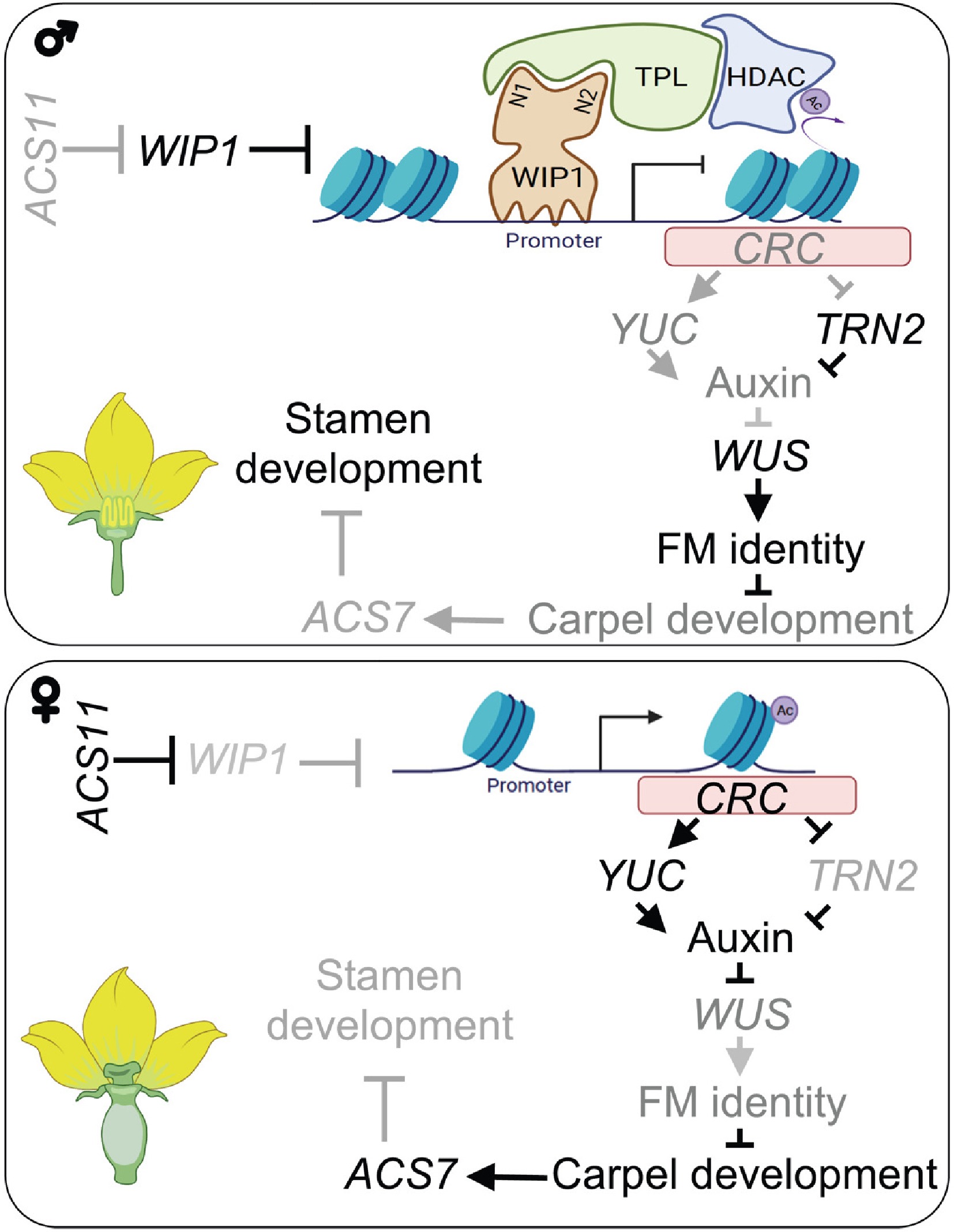

Stem cell termination in flower organs is a prerequisite for carpel development. Expression of WUS in male and female flowers during sex transition was detected by in situ hybridization. No WUS mRNA was detected in female flowers at stage 6, but the level of WUS mRNA in the carpel primordium of male flowers at the same stage was very high. It was found that the expression of WUS in the carpel primordium of male and female flowers increased by 3 times. In Arabidopsis, CRC inhibits WUS expression by up-regulating YUC4 and down-regulating TRN2. Similarly, three YUC genes were up-regulated and TRN2 was down-regulated in the micro dissected carpels of female flowers compared with those of male flowers. Together, these results suggest that CmWIP1 promotes male flower development by inhibiting CRC expression, thereby interfering with floral meristem determination in the carpel primordium (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Model explaining how WIP1-TPL controls the expression of CRC to lead to male flower development[7].

Following the 2009 discovery[5] that CmWIP1 is a female determining gene, this study reveals for the first time the transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of CmWIP1, and answers the outstanding questions about the relationship between sex determination and classical bisexual flower development. Together with the ACS ethylene synthesis gene pathway to regulate stamen development, the gene regulatory network for sex determination in Cucurbitaceae crops was improved.

Dr. Abdel Bendahmane, senior researcher at the French National Institute for Agri-Food and Environment (INRAE), the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), and the Paris-Sacre Botanical Institute of the University of Paris Sacre, is the corresponding author of the paper, and postdoctoral fellows Zhang Siqi and Tan Fengquan are co-first authors of the paper. Professor Moussa BENHAMED of the University of Paris Sacre also took part in the study. The research was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) and the French National Research Agency (ANR).

It is worth mentioning that Abdel Bendahmane's team have been engaged in related research on plant sex determination for a long time, and have identified and solved the key genes of cucurbit crop sex determination CmACS-7, CmWIP1 and CmACS11, etc., and have achieved a series of important research results, and are experts in the field of plant development[4−7].

HTML

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: performed experiments, and finished the writing of the manuscript: Zhang K; study conception and design: Ma G; data collection: Lin T; draft manuscript preparation: Li J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Received 12 July 2023; Accepted 20 September 2023; Published online 7 October 2023

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Zhang K, Li J, Lin T, Ma G. 2023. A new regulation mechanism of bisexual flower development in cucurbitaceous sex determination. Tropical Plants 2:17 doi: 10.48130/TP-2023-0017 |